Abstract

Background: Analgesic nephropathy (AN) is chronic renal impairment as a direct consequence of chronic heavy analgesia ingestion. An association between non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents and chronic kidney disease (CKD) has long been suspected. Despite ample observational data obtained in recent decades the relationship remains uncertain. This systematic review intends to summarize the available literature and to define the role of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories in the natural history of AN.

Methods: We conducted a systematic literature search for articles describing the association between non-steroidal anti-inflammatory abuse and renal insufficiency. No restriction was placed on publication date, but papers were limited to English language, observational design, and human studies.

Results: Nine articles met our inclusion criteria and were discussed in this review. This includes 5 cohort studies and 4 case–control trials, with a combined population of 12,418 study subjects and 23,877 controls. Eight of the nine reports failed to identify any increased risk of chronic renal impairment with heavy non-steroidal anti-inflammatory consumption. Study methods were heterogeneous and the overall quality of data was relatively poor.

Conclusion: A relationship between non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines and the development of CKD has never been proven. Based on the available scientific evidence non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents do not appear to be implicated in the pathogenesis of AN.

Introduction

Analgesic nephropathy (AN) is a form of chronic renal insufficiency caused by long-term regular ingestion of one or more analgesic medications. Its etiopathogenesis remains controversial and the particular agents known to induce AN and the cumulative doses required have not been established with certainty. Formerly one of the commoner causes of end-stage renal failure (ESRF), there has been a marked decline in the prevalence and incidence of AN over recent decades.Citation1,Citation2 At its peak in the 1980s AN accounted for 15–20% of cases of ESRF, which has fallen to approximately 1% in western countries today.Citation3–7

The true prevalence of AN is difficult to estimate because definitive diagnoses are rarely made. There are no validated objective diagnostic criteria. It is often a diagnosis of exclusion in patients with renal impairment who communicate a history of analgesic abuse in an absence of other causes. Most patients are asymptomatic and at least in middle age. They frequently describe a history of chronic pain, typically headaches or low back pain.Citation8 Patients usually admit to having taken regular analgesic medicines for many months or years, although they may deny or underreport their usage. Abnormal renal function is usually a serendipitous finding. Radiologic signs described in AN include atrophic kidneys, renal papillary calcification, and irregular renal contours. This combination of features is seldom seen in other diseases. No histologic changes are diagnostic of AN, but papillary necrosis and chronic interstitial nephritis are characteristic.Citation4,Citation5,Citation9

An association between non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) has long been suspected. Despite a relatively large quantity of observational evidence, their specific contribution to the development of AN is undetermined. Randomized controlled trials are absent and research so far has relied upon experimental animal models or epidemiological human studies with conflicting outcomes. This systematic review intends to summarize the available literature and to define the role of NSAIDs in the pathogenesis of AN.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search of the PubMed and Griffith University Library electronic databases, up to and including 23 March 2016. The following two entries were entered as the search strategy: ((Abstract:(non-steroidal)) OR (Abstract:(NSAID))) AND ((Abstract:(analgesic nephropathy)) OR (Abstract:(renal impairment)) OR (Abstract:(nephrotoxicity))), and ((Abstract:(non-steroidal)) OR (Abstract:(NSAID))) AND ((Abstract:(analgesic nephropathy)) OR (Abstract:(renal impairment)) OR (Abstract:(nephrotoxicity))) AND (Abstract:(chronic)). With this search, we intended to obtain relevant observational literature relating to AN and its interaction with NSAIDs.

Study selection and data extraction

The titles and abstracts of the search hits were screened independently by two reviewers. Studies were considered eligible for inclusion only if they satisfied the following criteria: written in English, of case–control or cohort or randomized study design, conducted on humans, provides data sufficient to allow calculation of statistical significance, and with appropriate control and intervention populations. No restriction was placed on publication date. A third reviewer was to be consulted in the event of disagreement about study inclusion.

It was a prerequisite that cohort studies include a reference group of NSAID non-users, while case–control studies must have enrolled a reference group representing patients with normal renal function. Intervention groups in cohort studies must have been chronic users of NSAIDs while case–control studies were expected to have compared controls with subjects demonstrating some form of chronic renal impairment.

Our search was supplemented by manual screening of the reference lists within the identified relevant articles. Any listed references deemed appropriate for our systematic review were also included. Duplicated studies retrieved by our systematic literature search were removed.

Data from each study were extracted and entered into a standardized pre-prepared table. This was completed by both authors concordantly. Where necessary, the available study data were extrapolated to provide odds ratios or relative risk with a 95% confidence interval.

Quality assessment

Study quality was evaluated using the approach outlined by the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) Working Group.Citation10,Citation11 To assess the quality of evidence, both authors cooperated in appraising each paper using the GRADE assessment tool (Appendix 1). High-quality evidence was considered data in which further evidence would be unlikely to change our confidence in the effect. Moderate-quality data were defined as evidence for which our confidence in its effects may be modified by further research. Finally, low-quality investigations were considered those for which our confidence in their outcomes is likely to be modified by future research and very low quality implies that our confidence in the result is negligible. This method of literature assessment allowed an objective tool to be applied to a subjective interpretation, and was designed to improve appreciation of the strength of evidence.

Results

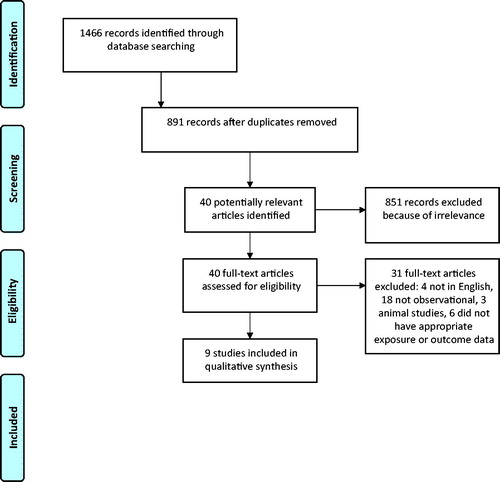

Our literature search identified a total of 1466 records. Following duplicate removal, the titles and abstracts of 891 papers were screened by both authors separately. Based on perusal of titles and abstracts, 40 potentially relevant articles were identified for further review (). Full texts were retrieved and were cross-checked for satisfaction of inclusion criteria, and following detailed review 9 titles were ultimately considered for discussion in this report.Citation12–20 Both authors were in full agreement about the final 9 articles. We excluded 31 of the 40 reviewed full texts: 4 papers were not written in English, 8 were cross-sectional in design, 1 case–control study did not specifically differentiate NSAIDs as a group from general analgesia use, 3 were animal experimental studies, there were 5 cohort papers which did not include an appropriate endpoint of renal impairment, and 10 records were narrative articles of varying relevance.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of included studies are summarized in . Nine articles have been incorporated, including 5 cohort studies and 4 case–control studies. No randomized controlled trials were discovered in this arena. The articles were published between the years of 1991 and 2015: only two of these were released prior to 2001. All populations originated from industrialized nations: 5 articles from USA, and 1 each from Australia, Spain, Italy, and Switzerland.

Table 1. Characteristics of observational studies included in this review.

The combined studies report on findings of 12,418 individuals from intervention groups and 23,877 control subjects. Each of the cohort studies tested a group of NSAID consumers against a control group with absent or trivial NSAID consumption, and compared the relative chance of developing kidney impairment as an outcome. All cohort papers compared GFR between groups, while 1 also compared the prevalence of albuminuria,Citation12 and 1 also compared serum creatinine.Citation19 To qualify for inclusion all case–control studies must have involved case patients with some form of renal impairment and a reference group with normal renal function. Two case–control groups gathered patients enlisted on dialysis while 2 studies recruited participants with a health-care registry coded diagnosis of CKD.

Study quality

Papers discussed in this review are of variable quality. Using the GRADE approach, 3 studies were considered moderate level evidence.Citation13,Citation18,Citation19 The moderate-quality papers are observational studies upgraded due to their examination of dose-dependence. Five studies are low quality,Citation12,Citation14–17 and 1 is very low.Citation20 Consensus was reached by both authors in establishing this level of evidence. A meta-analysis was not attempted due to study heterogeneity and methodological flaws.

Study results

The method of publishing outcomes and statistical significance varied between studies. Most reported the odds ratio for development of renal impairment in the setting of NSAID abuse compared with minimal NSAID ingestion. One used relative risk,Citation19 1 reported the difference in mean GFR,Citation17 and 1 reported prevalence without calculation of an odds ratio.Citation16 In the latter case, we converted the provided data into an odds ratio using logistic regression based on Fisher’s exact test. The study by Kohlhagen et al. found 19% of NSAID consumers to have reduced GFR compared with 17% of non-consumers, which is statistically insignificant (p = 0.67). Using the data provided we calculated an equivalent OR of 1.24 (95% CI: 0.49–3.10).Citation16

Of the 9 papers explored in this systematic review, only 1 reported a statistically significant relationship between NSAID use and the development of CKD.Citation20 The remaining papers failed to establish any link between protracted excessive NSAID consumption and chronic nephrotoxicity.Citation12–19 In contradistinction to the other studies, the 1991 case–control study by Sandler and colleagues found appreciably more patients with CKD to have consumed regular NSAIDs than patients without CKD (OR 2.1, 95% CI: 1.1–4.1).Citation20 Following subgroup analysis however, the effect was limited to men greater than 65 years of age with no statistical significance observed in any other subgroup. Women and younger men were not more likely to suffer from CKD with heavy NSAID use. These results can be viewed in .

Discussion

Our systematic review summarizes observational studies that have examined the relationship between long-term heavy NSAID use and the development of chronic renal impairment. The available data do not appear to support the hypothesis that chronic NSAID ingestion is implicated in the pathogenesis of AN. No statistically significant association between heavy NSAID use and CKD was demonstrated in 8 of the 9 observational studies included in this systematic review. Cohort studies compared NSAID users with non-users and did not detect any difference in the incidence of kidney disease.Citation12,Citation13,Citation16,Citation17,Citation19 Most case–control studies compared CKD or ESRF patients with control groups and failed to identify any pattern in NSAID use between groups.Citation14,Citation15,Citation18

Only the case–control paper by Sandler and colleagues reached a discordant outcome.Citation20 Investigators found a statistically significantly increased likelihood of past protracted NSAID consumption in dialysis patients compared with community residents (OR 2.1, 95% CI: 1.2–82.7). However, this is the only very low-quality article included in our review and it features several peculiarities. After subgroup analysis this effect held true only in elderly men, the response was not dose-dependent, and the confidence interval of this result is unacceptably wide. Additionally, 53% of the dialysis arm had known renal diagnoses and any argument for causation by NSAID consumption in that group is therefore untenable.

We believe that the balance of these findings is sufficient to exclude a role for chronic NSAID ingestion in the development of AN. This is a weak recommendation based on the minimum requirements for strengths of evidence as outlined by the GRADE Working Group.Citation11 Our conclusion is not entirely consistent with expert consensus. Several authorities have previously published guidelines outlining best practice in the absence of randomized trial data.Citation21,Citation22 Statements by the International Study Group on Analgesics and Nephropathy in 1999 and the National Kidney Foundation in 1996 concluded that current evidence is lacking and cannot be used to support or refute the importance of NSAIDs in the pathobiology of AN. It should be noted that 7 of the 9 studies in our paper have been published since 2001 and therefore these positions may be outdated. We have been unable to locate any contemporary clinical guidelines on the subject of AN.

There are multiple deficiencies in observational evidence and no studies included in our systematic review are high quality. Causality cannot be proven because of inherent limitations in study design. Selection bias is a fundamental weakness which produces retro-causation. In the current context, the possibility remains that patients with CKD or those predisposed to developing CKD have a greater requirement for analgesia than controls, with the effect of analgesia itself bearing no influence on kidney health. Further, because renal insufficiency is typically insidious and analgesic use is widespread, any link based on epidemiologic data is likely to be coincidental rather than causal. Indeed, no studies in this review have been able to authenticate that NSAID exposure antedated the onset of kidney disease, an absolute requirement for establishing causation. Finally, the endpoint in many papers is ESRF rather than AN or some lesser degree of renal impairment. Any relationship based on such data would remain questionable since AN progresses to ESRF relatively infrequently.

Conclusion

This systematic review of literature has failed to identify any relationship between heavy protracted NSAID use and the incidence of chronic renal impairment. The hypothesis that AN can be induced by NSAIDs was not validated in 8 of the 9 observational studies included in our review. Although it can be concluded on the balance of evidence currently available that NSAIDs do not produce AN, without randomized controlled trial data such a relationship cannot be totally excluded.

Disclosure statement

With respect to the article “Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and the development of analgesic nephropathy: a systematic review”, there are no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence our work. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- De Broe M, Elseviers M. Analgesic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:446–452.

- Chang S, Mathew T, McDonald S. Analgesic nephropathy and renal replacement therapy in Australia: Trends, comorbidities and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:768–776.

- Buckalew V, Schey M. Renal disease from habitual antipyretic analgesic consumption: An assessment of the epidemiologic evidence. Medicine. 1986;11:291–303.

- De Broe M, Elseviers M. Over the counter analgesic use. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2098–2103.

- Pinter I, Matyus J, Czegany Z, et al. Analgesic nephropathy in Hungary: The HANS study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:840–843.

- Bennett W, De Broe M. Analgesic nephropathy – A preventable renal disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1269–1271.

- Delzell E, Shapiro S. A review of epidemiologic studies of non-narcotic analgesics and chronic renal disease. Medicine. 1998;77:102–121.

- Gault M, Wilson D. Analgesic nephropathy in Canada: Clinical syndrome, management and outcome. Kidney Int. 1978;13:58–63.

- Noels L, Elseviers M, De Broe M. Impact of legislative measures on the sales of analgesics and the subsequent prevalence of analgesic nephropathy: A comparative study in France, Sweden and Belgium. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:167–174.

- Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. London, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available at: www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- Atkins D, Best D, Briss P, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1–8.

- Agodoa L, Francis M, Eggers P. Association of analgesic use with prevalence of albuminuria and reduced GFR in US adults. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:573–583.

- Curhan G, Knight E, Rosner B, Hankinson S, Stampfer M. Lifetime non-narcotic analgesic use and decline in renal function in women. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1519–1524.

- Ibanez L, Morlans M, Vidal X, Martinez M, Laporte JR. Case-control study of regular analgesic and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use and end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2393–2398.

- Ingrasciotta Y, Sultana J, Giorgianni F, et al. Association of individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and chronic kidney disease: A population-based case control study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122899.

- Kohlhagen J, Katrib A, Stafford L, Brown M, Edmonds J. Does regular use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of renal disease? Nephrology. 2002;7:5–11.

- Moller B, Pruijm M, Adler S, et al. Chronic NSAID use and long-term decline of renal function in a prospective rheumatoid arthritis cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:718–723.

- Perneger T, Whelton P, Klag M. Risk of kidney failure associated with the use of acetaminophen, aspirin, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1675–1679.

- Rexrode K, Buring J, Glynn R, Stampfer M, Youngman L, Gaziano M. Analgesic use and renal function in men. JAMA. 2001;286:315–321.

- Sandler D, Burr R, Weinberg C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk for chronic renal disease. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:165–172.

- Henrich W, Agoda L, Barrett B, et al. Analgesics and the kidney: Summary and recommendations to the Scientific Advisory Board of the National Kidney Foundation from an ad hoc committee of the National Kidney Foundation. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;27:162–165.

- Feinstein A, Heinemann L, Curhan G, et al. Relationship between nonphenacetin combined analgesics and nephropathy: A review. Kidney Int. 2000;58:2259–2264.