Abstract

Background: The relationship between personality and health is frequently studied in scientific research. This study investigated the clinical/biochemical course of kidney transplant patients based on personality traits.

Methods: A longitudinal study assessed 114 kidney transplant patients (men = 68 and women = 46) with an average age of 47.72 years (SD = 11.4). Personality was evaluated using the Brazilian Factorial Personality Inventory (BFP/Big Five Model). Clinical variables were analyzed based on patient charts (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hypertension, acute rejection, infection, graft loss, and death). Personality types were assessed by hierarchical cluster analysis.

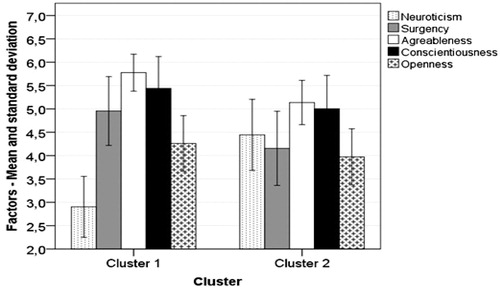

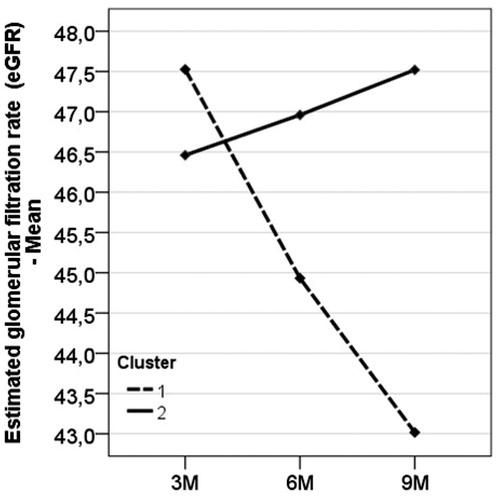

Results: Two groups with personality types were differentiated by psychological characteristics: Cluster 1 - average neuroticism, high surgency, agreeableness and conscientiousness, and low openness; Cluster 2 - high neuroticism, average surgency and agreeableness, average conscientiousness, and low openness. There was no statistically significant difference between the clusters in terms of hypertension, acute infection, graft loss, death, and Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) I and II panel reactive antibodies. eGFR was associated with the personality types. Cluster 2 was associated with a better renal function in the 9-month follow-up period after kidney transplantation.

Conclusion: In this study, patients from Cluster 2 exhibited higher eGFR 9 months after the transplant procedure compared to those from Cluster 1. Monitoring these patients over a longer period may provide a better understanding of the relationship between personality traits and clinical course during the post-transplant period.

Introduction

Personality traits have been linked to health, including when assessing kidney transplant patients. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients with high levels of neuroticism exhibited a 37.5% higher mortality rate than those with average scores in this trait.Citation1 Similarly, neuroticism can be a significant predictor of depression in CKD patients on the transplant list.Citation2

Surgency reflects the area of relationships and has proved to be related to self-care in CKD patients on the transplant list.Citation3 Agreeableness, in turn, is associated with the quality of interpersonal relationships. Research indicates that agreeableness is related to health promotion behavior and adaptation to dialysis.Citation4,Citation5

Patients on the transplant list with low conscientiousness scores exhibited non-adherence to immunosuppressive therapy less than a year after transplantation.Citation6 In addition, CKD patients with low conscientiousness score showed a 36.4% increase in mortality in relation to the average obtained from the population.Citation7,Citation1 Kidney transplant patients with low openness scores were 91% more likely not to adhere to treatment.Citation8

A number of studies have focused on the influence of personality traits on health behaviors,Citation9,Citation10,Citation4 while others have assessed the relationship between personality and biological health indicators.Citation11,Citation12 Personality traits are typically analyzed using the Big Five Model, associating levels of these traits with the development or maintenance of different pathologies,Citation5,Citation12–14 but researchers are seeking to understand how combinations of personality traits are related to individual health. Most studies evaluate the big five personality traits individuallyCitation3–5,Citation9; however, the current research proposes assessing the big five traits based on the idea of personality types. In adults, the proposed model used cluster analysis.Citation15 Studies investigating personality types applied the statistical cluster analysis method.Citation15,Citation16

Although personality traits are often studied separately, they are interconnected in individuals and form different types of combinations.Citation17 Certain combinations of traits are likely more associated with health than individual traits.Citation17 Thus, it is possible for personality traits to be interpreted as a whole, producing personality types.Citation18

Materials and methods

Studio design

A longitudinal design with clinical/biochemical assessments of kidney transplant patients 3, 6, and 9 months after surgery. Personality and socio-demographic data were collected on a single occasion following transplantation.

Setting and participants

Participants were 114 adult patients (68 women; 59.6% of the sample) aged between 20 and 64 years (average = 47.7 years; SD = 11.4), who had undergone their first kidney transplant at a transplant center (Brazil) between January 2012 and December 2013. Inclusion criteria were kidney transplant patients (cadaveric or living donor) aged between 18 and 65 years; first kidney transplant without the need for dialysis in the third month of follow-up. Replacement therapy of renal function used prior to transplantation was hemodialysis. Not included in the study were patients with transplanted kidney who died before the interview; who died before the third month after transplantation; whose renal graft failed and who returned to dialysis before the third postoperative month; or when it was perceived there was difficulty in comprehension in answering the questionnaire.

The first stage of data collection involved gathering socio-demographic and clinical information and applying the post-transplant personality assessment. Clinical/biochemical data on the patients were taken from their charts 3, 6, and 9 months after the transplant. The socio-demographic data and personality data were collected by previously trained psychology students. Biochemical/clinical data were collected by medical students, who were also previously trained for the activity. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee and all participants gave their written consent.

Measurements

Questionnaire on socio-demographic and clinical data

The socio-demographic data collected were the name, sex, age, race, marital status, occupation, and whether the subject had children. Also investigated were the type of donor (cadaveric or living donor), previous or current psychological/psychiatric treatment, use of medication for depression, and time on the waiting list.

Biochemical and clinical chart

Data assessed were the presence of hypertension, infection, acute rejection episodes, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR/calculated using the CKD-EPI), graft loss, and death.

Factorial Personality Inventory (BFP)Citation19

Personality traits were evaluated by Factorial Personality Inventory (BFP). The BFP is based on the Big Five Personality Trait Model (Big Five). It consists of 126 items on a Likert scale scored from 1 to 7. The more accurately the relevant phrase describes the person the higher the score marked on the scale. (1) Surgency, (2) agreeableness, (3) neuroticism, (4) Conscientiousness, and (5) openness. In order to facilitate data interpretation, scores were converted into percentiles and classified into ranges. Low: up to 29; Average: between 30 and 70; high: over 71. Reliability was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha. Neuroticism: 0.832, surgency: 0.801, agreeableness: 0.698, conscientiousness: 0.752, and openness: 0.719. Thus, given the satisfactory results obtained for the instrument’s internal consistency, there is evidence that the validity of the BFP’s internal structure remains intact.

Statistical analysis

Hierarchical cluster analysis followed by the k-means method was used to assess personality types. Cluster analysis involves grouping data elements based on their similarity. Groups are established in such a way that elements in the same group are more similar to each other than to those in other groups. Furthermore, the structure of the five personality factors, analysis of cluster used the raw scores of each of the factors to form groups. Among the groups the average scores for each factor are statistically different, implying groups represent different personality profiles.

Data distribution was analyzed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and results were presented using descriptive statistics in the form of absolute (n) and relative distributions (%), as well as central tendency and variability measures.

Pearson’s chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were applied to analyze categorical variables in relation to the clusters. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Student’s t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test.

Possible differences between the clusters in the three assessment periods were investigated by repeated measures analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) and sphericity was evaluated using Mauchly’s sphericity test (sphericity determines whether the technique is suitable for data assessment and whether or not the data provide reliable results in the sample). The Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied to those data sets in which sphericity was not assumed. In the event of differences established via ANOVA, a multiple comparison tests (post hoc) was conducted with a Bonferroni correction.

Measurements were compared over time and between groups using repeated measures analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) in order to test the effects of time, clustering, and time × cluster interaction. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL 2010) version 20.0 for Windows, adopting a significance level of 5% for statistical decision criteria.

Results

Two clusters were compiled (Clusters 1 and 2). With respect to characterizing the personality types for each cluster based on average personality scores (), it was found that patients in Cluster 1 (n = 61) exhibited average levels of neuroticism; high surgency, agreeableness and conscientiousness scores, and low openness. Cluster 2 (n = 53) showed high neuroticism scores, average surgency, agreeableness and conscientiousness, and low openness levels ().

Table 1. Mean, standard deviation, percentage classification of each personality trait in Clusters 1 and 2.

No significant differences were identified between the two groups in terms of socio-demographic characterization of the sample for the two types ().

Table 2. Socio-demographic data—total for the sample and by cluster.

The remaining clinical variables and variations observed between the two clusters were also not representative in this sample ().

Table 3. Absolute and relative distribution for type of donor, psychological/psychiatric treatment, use of medication and central tendency, and variability measures for time on the waiting list. Total for the sample and by cluster.

In regard to the clinical/biochemical variables monitored at 3, 6, and 9 months, the two clusters exhibited similar behavior in terms of hypertension, infection, acute rejection, graft loss, and death ().

Table 4. Absolute and relative distribution for the presence of hypertension, infection, acute rejection, graft loss, and death in assessments at 3, 6, and 9 months—total for the sample and by cluster.

Table 5. Mean, SD, and median for estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in the assessments/total for the sample and by the cluster.

Analysis of eGFR data (/) identified a significant result for interaction effect (F(2, 214) = 3.059; p = 0.049; power = 0.587), indicating that both clusters exhibited average eGFR levels with different variations over time, as well as different means at each assessment occasion. The interaction effect observed demonstrated that the relationship between average eGFR levels and time in Cluster 1 differs from that of Cluster 2. In this respect, Cluster 1 exhibited a slight decline in the mean over time (3M: 46.5 ± 21.2; 6M: 44.4 ± 18.5; 9M: 43.0 ± 17.9), whereas an increase was recorded in Cluster 2 (3M: 45.7 ± 13.6; 6M: 46.2 ± 15.0; 9M: 47.5 ± 15.1). In relation to average eGFR levels, no significant effects were detected for time (or assessment) (F(2, 214) = 1.186; p = 0.307; power = 0.258), or Cluster (F(1, 214) = 0.371; p = 0.544; power = 0.0936). In other words, the results indicate that average levels in both clusters varied equally over time, though in different directions.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the association between personality traits, clinical/biochemical changes over a 9-month period following kidney transplantation. The two clusters identified by statistical analysis exhibited intergroup differences. Low levels of openness were observed in both groups. There was no difference in demographic data and clinical/biochemical variables (hypertension, infection, acute rejection, graft loss, and death) in the two clusters.

In Cluster 2, scores for surgency, agreeableness and conscientiousness were within the average range, whereas high levels of neuroticism were observed. High neuroticism is related to emotional distress, emotional dependency, insecurity in different situations, and psychological instability. This result demonstrates that characteristics of emotional instability, depression, and psychological distress may be prevalent in this group of patients. However, Cluster 2 showed better eGFR levels when compared to patients from Cluster 1.

This result differs from other studies, since research investigating health patterns and personality in healthy people found that high neuroticism levels were harmful to health.Citation20–22 By contrast, in a study of healthy women, all-cause mortality was lower, with greater neuroticism associated with longer life expectancy.Citation23 In addition, in elderly patients neuroticism was also identified as a protective factor.Citation24 Increased psychological distresses in kidney transplant patients may prompt greater protection and care from health care staff in the initial post-transplant months.

Both groups in this study obtained low openness scores, revealing similar results to other samples of heart and lung transplant recipients.Citation25 It is important to underscore the significance of this factor in the population under study since it may indicate the relevance of this trait. This is because low openness scores may reflect a reluctance to change lifestyle habits and little interest in new activities, as well as difficulties in situations that differ from the norm.Citation19 An adjustment period of up to 1 year is expected for transplant patients following the procedure. During this time, patients are learning and adapting to their new health situation, which involves adhering to a routine of tests and medication. The openness trait seems to reduce the chances of diagnosis for several diseases, suggesting a greater impact on health than previously thought.Citation26 Additionally, openness was identified as a protective factor in health processes and is a good indicator in predicting effects on social adjustment levels.Citation27,Citation28 In kidney transplant patients, a low openness score was associated with poor adherence to treatment.Citation8 On the other hand, the mechanisms of association between the openness trait and different diseases has yet to be fully elucidated, since high or low scores may stimulate behaviors that influence health, such as physical exercise, diet and smoking, among others.

Transplant procedures tend to promote anxiety and emotional distress since issues involving the possibility of death and transplant success can result in insecurities that are partly related to the transplant process itself. Thus, personality traits are one of the variables that may determine the choice of coping strategies, whether adequate or not, as well as an emotional pattern that enables people to deal with stressors.

Regarding the quality of life of transplant patients, it is understood that the suffering is caused not only by the disease but also the treatment and waiting for the transplant, which decreases patients’ quality of life. However, personality dynamics may contribute an important mechanism in adaption to the situation experienced, allowing, according to the characteristics of each person, greater or lesser capacity for autonomy and wellbeing. Therefore, although transplantation has a positive impact on the physical quality of life of people, the assimilation time of the emotional aspects involved almost always differs to the clinical process, making the process of transplant adaptation complex.

The first year of monitoring for transplant patients involves increased assistance from their caregivers. This may explain the results found since during this time patients are being cared for and are less autonomous. It is possible that chronic renal disease and/or transplantation enhance the openness trait precisely because of the limitations that dialysis or even transplantation causes in patients. In addition, the distress caused by treatment prior to transplantation can affect levels of the trait in CRF patients. In a recent study, openness was associated with longevity and the emergence of diseases.Citation29 The stability of personality traits throughout life and during life events is controversial.Citation30 According to some researchers, although personality traits may change throughout life, individuals exhibit specific behavioral or relationship tendencies.Citation31 Others report that the impact of stressful events on the personality may be temporary.Citation32 As such, despite the numerous studies evaluating the relationship between personality traits or types and health, little is known about the impact of personality types on the biological behavior of kidney transplant patients.Citation22,Citation25,Citation33–35

The different methodologies applied in the investigations mentioned here and the present study may have contributed to the differences in the results obtained. In addition, the follow-up time in longitudinal studies seems to be a predictor of different results. Studies that correlated personality traits with different diseases used longer assessment periods, which enabled associations to be made between personality types and the development or maintenance of different pathologies.Citation17,Citation26 On the other hand, in chronic renal failure and kidney transplant patients associations with personality traits, were made using a cross-sectional study design.Citation8,Citation36,Citation37 The analysis method applied in the present study sought to monitor patients over a 9-month period after transplant surgery, evaluating clinical data with a 3-month interval between assessments. It is possible that the 9-month post-transplant period is somewhat short to assess the evolution of clinical parameters and association with personality types since it is during this period that patients receive the most medical care and support.

Even when the transplant demonstrates good results, patients are still suffering from a chronic disease that requires lifelong medical supervision. Important questions emerge regarding the post-transplant period. Do transplant recipients maintain the same biological patterns 1 year after the procedure? Will patients who are more prone to emotional instability maintain good clinical results 1 year after transplantation? One hypothesis is that behavior patterns that affect clinical variables, such as adherence to treatment, smoking and diet, are being monitored and influenced by the clinical care team, particularly in the early months. Transplant patients have a strong bond with care staff, particularly in the first year after surgery, during which time they are systematically evaluated and the fear of organ rejection is most present. As such, poor treatment adherence in the patients who exhibit the personality type in Cluster 1 may be minimized due to the influence of caregivers. Patients who are potentially vulnerable to emotional instability will likely express the concerns caused by the post-transplant period more intensely and may, therefore, be more easily identifiable by caregivers and family members. Once identified, care staff and family members may intensify post-transplant care. It is possible that patients who receive social and family support and medical care present good results in the first year, while indications of restored health may lead some patients to neglect treatment after transplant.Citation38 In liver, heart, and lung transplant patient’s insufficient social support was associated with poor adherence to immunosuppressant medication in the first year after transplantation.Citation6

The findings of this study contrast those of several other investigations that evaluated personality and health behaviors; however, other studies also observed a positive association between low neuroticism, mortality, and morbidity based on biological parameters.Citation11 Although a number of studies have associated personality traits with the disease, it is not entirely clear whether these same traits are predictors of the clinical course of certain pathologies. One possibility is that personality traits are connected differently in different diseases.

In this study, patients with high levels of neuroticism showed better results in terms of renal function. In light of this finding, it is possible that neuroticism is an important factor in health care and protection in the first year after transplant; however, it is not yet known whether this pattern of better clinical conditions continues in the long-term. The renal function levels observed in this study may not be directly related to personality types. Nevertheless, indirect behavioral relationships may mediate good or poor clinical results.

These results should be interpreted with caution since the possible mediating effect of behavioral variables on the clinical results obtained was not assessed. This is because people with different personality types also behave differently in different situations. The results demonstrate that the renal function variable is associated with personality traits. One of the findings of this study corroborates the personality types described in this sample.

After analyses, the resulting two personality types differed significantly for all traits except openness, which is interesting because patients could have been highly heterogeneous in terms of personality traits. This finding raises questions regarding the extent to which personality traits can lead to the development or perpetuation of disease. In light of the results, future studies should include other variables that significantly influence health, since health behaviors are regulated by multifactorial aspects. The personality type that points to high neuroticism and average surgency, agreeableness and conscientiousness scores was associated with higher eGFR. The relationship and quality of the bond with multidisciplinary teams in the first year after transplant may be a major differential to be considered in future research and at different transplant centers.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the patients who agreed to participate and to the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for supporting this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Christensen AJ, Ehlers SL, Wiebe JS, et al. Patient personality and mortality: A 4-year prospective examination of chronic renal insufficiency. Health Psychol. 2002;21:315–320.

- Thomas CV, Castro EK. Personality factors, self-efficacy and depression in chronic renal patients awaiting kidney transplant in Brazil. Interam J Psychol. 2014;48:119–128.

- Horsburgh ME, Beanlands H, Locking-Cusolito H, Howe A, Watson D. Personality traits and self-care in adults awaiting renal transplant. West J Nurs Res. 2000;22:407–437. PubMed

- Bogg T, Roberts BW. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:887–919. PubMed

- Kidachi R, Kikuchi A, Nishizawa Y, Hiruma T, Kaneko S. Personality types and coping style in hemodialysis patients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61:339–347.

- Dobbels F, Vanhaecke J, Dupont L, et al. Pretransplant predictors of posttransplant adherence and clinical outcome: An evidence base for pretransplant psychosocial screening. Transplantation 2009;87:1497–1504. PubMed

- Jokela M, Batty GD, Nyberg ST, et al. Personality and all-cause mortality: Individual-participant meta-analysis of 3,947 deaths in 76,150 adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:667–675. PubMed

- Gorevski E, Succop P, Sachdeva J, et al. Is there an association between immunosuppressant therapy medication adherence and depression, quality of life, and personality traits in the kidney and liver transplant population? Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:301–307.

- Cheung MM, LeMay K, Saini B, Smith L. Does personality influence how people with asthma manage their condition? J Asthma. 2014;51:729–736.

- Eggert J, Levendosky A, Klump K. Relationships among attachment styles, personality characteristics, and disordered eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:149–155.

- Sadahiro R, Suzuki A, Enokido M, et al. Relationship between leukocyte telomere length and personality traits in healthy subjects. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30:291–295.

- Shim U, Oh JY, Lee H, Sung YA, Kim HN, Kim HL. Association between extraversion personality and abnormal glucose regulation in young Korean women. Acta Diabetol. 2014;51:421–427. PubMed

- Korotkov D. Does personality moderate the relationship between stress and health behavior? Expanding the nomological network of the five-factor model. J Res Pers. 2008;42:1418–1426.

- Aghaei S, Saki N, Daneshmand E, Kardeh B. Prevalence of psychological disorders in patients with Alopecia areata in comparison with normal subjects. ISRN Dermatology. 2014;1–4.

- Asendorpf JB, Borkenau P, Ostendorf F, Van Aken MAG. Carving personality description at its joints: Confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. Eur J Pers. 2011;15:169–198.

- Chapman BP, Goldberg LR. Replicability and 40-year predictive power of childhood ARC types. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101:593–606.

- Kinnunen ML, Metsäpelto RL, Feldt T, et al. Personality profiles and health: Longitudinal evidence among Finnish adults. Scand J Psychol. 2012;53:512–522.

- Donnellan MB, Robins RW. Resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled personality types: Issues and controversies. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2010;4:1070–1083.

- Nunes CHSS, Hutz CS, Nunes MFO, eds. Bateria Fatorial de Personalidade (BFP): Manual Técnico. São Paulo, SP: Casa Do Psicólogo 2010;1–238.

- Neeleman J, Sytema S, Wadsworth M. Propensity to psychiatric and somatic ill-health: Evidence from a birth cohort. Psychol Med. 2002;32:793–803.

- Goodwin RD, Cox BJ, Clara I. Neuroticism and physical disorders among adults in the community: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. J Behav Med. 2006;29:229–238.

- Charles ST, Gatz M, Kato K, Pedersen NL. Physical health 25 years later: The predictive ability of neuroticism. Health Psychol. 2008;27:369–378.

- Ploubidis GB, Grundy E. Personality and all cause mortality: Evidence for indirect links. Pers Individ Dif. 2009;47:203–208.

- Weiss A, Costa PT, Jr. Domain and facet personality predictors of all-cause mortality among Medicare patients aged 65 to 100. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:724–733.

- Stilley CS, Dew MA, Pilkonis P, et al. Personality characteristics among cardiothoracic transplant recipients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:113–118.

- Weston S, Hill PL, Jackson JJ. Personality traits predict the onset of disease. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2015;6:309–317.

- Ferguson E, Bibby PA. Openness to experience and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis and r(equivalent) from risk ratios and odds ratios. Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17:85–102.

- Pistorio ML, Veroux M, Corona D, et al. The study of personality in renal transplant patients: Possible predictor of an adequate social adaptation? Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2657–2659.

- Turiano NA, Spiro A, Mroczek DK. Openness to experience and mortality in men: Analysis of trait and facets. J Aging Health. 2012;24:654–672.

- Pervin LA, John OP. Handbook of Personality Research: Theory and Research. 8th ed. New York: Guilford; 2001.

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. From catalog to classification: Murray’s needs and the five-factor model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55:255–265.

- Mroczek DK, Spiro A, 3rd. Modeling intraindividual change in personality traits: Findings from the normative aging study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58:153–165.

- Denollet J, Vaes J, Brutssaert D. Inadequate response to treatment in coronary heart disease: Adverse effects of type D personality and younger age on 5-year prognosis and quality of life. Circulation 2000;102:630–635.

- Duggan KA, Friedman HS, McDevitt EA, Mednick SC. Personality and healthy sleep: The importance of conscientiousness and neuroticism exploratory study. PLoS One 2014;9:e90628.

- Sáez-Francàs N, Valero S, Calvo N, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome and personality: A case-control study using the alternative five factor model. Psychiatry Res. 2014;216:373–378.

- Poppe C, Crombez G, Hanoulle I, Vogelaers D, Petrovic M. Improving quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease: Influence of acceptance and personality. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:116–121.

- Prihodova L, Nagyova I, Rosenberger J, Roland R, van Dijk JP, Groothoff JW. Impact of personality and psychological distress on health-related quality of life in kidney transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 2010;23:484–492.

- Slobodan I, Avramović M. Psychological aspects of living donor kidney transplantation. Med Biol. 2002;9:195–200.