ABSTRACT

Drawing on recent research on the Anglo-Scottish border, this article examines the social and economic impact of a more powerful Scotland on its “nearest neighbors” in the North East of England. In examining a series of competing narratives that shape how the significance of the Anglo-Scottish border and borderlands have been understood, the discussion begins by highlighting the longevity of a traditional conflictual narrative that a more powerful Scotland will undermine the North East’s economic fortunes. The article will further consider the strength of a competitive narrative by capturing how North East reactions to the independence referendum north of the border have been used as a springboard to argue for greater powers to be devolved to the North East itself— and has led directly to a new generation of “Devolution Deals” being offered by the UK Government to the English regions. Thirdly, the article will examine how the discursive space created by the referendum campaign (and outcome) has created the conditions within which a collaborative narrative—highlighting how Scotland and the North East of England have a shared history and common social and economic challenges—has emerged. The article will conclude by considering whether the emergence of a new cross-border relationship between the “Northern Lights” allows the Anglo-Scottish border to be conceptualized more as a “bridge” than a “barrier,” particularly given the UK’s recent decision to leave the EU.

Scottish independence represents a real threat to the region. If Scotland gets tax powers and offers lower corporation tax it could mean that firms leave the region and move north of the border. (John Shipley, former Leader of Newcastle Council, quoted in Schmuecker, Lodge, and Goodall Citation2012, 4)

The growth of a strong economic power in the north of these islands would benefit everyone – our closest neighbours in the north of England more than anyone. There would be a “northern light” to redress the influence of the “dark star” (London) in rebalancing the economic centre of gravity of these islands. (Alex Salmond MSP, quoted in The New Statesman March 5, Citation2014)

Introduction

Almost overnight, the whole dynamic of the relationship between Scotland and the rest of the UK has fundamentally changed. Despite the triumph of the “No” vote in the September 2014 referendum, and the subsequent offer of more economic and fiscal powers to Scotland by the UK Government, it is hard not to view—as somewhat complacent—the Westminster Government’s immediate-post referendum assumption that Scottish independence has now “been removed from the political agenda for a generation” (The Guardian September Citation19, Citation2014). Indeed, the size of the “Yes” vote in the referendum (45% of voters—1.5 m Scots—wanted to leave the UK), the Scottish National Party’s (SNP) stunning electoral performance in the UK General Election in May 2015 (House of Commons Library Citation2015) and their continued criticism of the UK Government’s “limited” devolution offer (as defined the 2016 Scotland Act) have all ensured that the issue of, even greater, devolution to Scotland remains firmly on the political agenda. In addition, the momentous decision by the UK (as a whole) to leave the EU following a referendum in June 2016, was not shared by the people of Scotland who voted strongly to remain in the EU. For the Scottish First Minister and her government, this clearly constitutes the “significant and material change of circumstance”—that they argued after the 2014 referendum—would justify calling a second referendum on independence. In October 2016, First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon MSP, duly announced plans for a second referendum on an independent Scotland (BBC Citation2016).

Inevitably, the developing momentum of Scotland’s case for devolution/independence has served to reopen debates about the growing divergence between the wide range of powers likely to be available to the Scottish Government in Edinburgh and the more limited powers initially allocated for the devolved administrations in Wales and Northern Ireland and, in particular, the very limited powers available for sub-national interventions within the localities and regions of England itself (Cabinet Office Citation2014). One such area of England—where the likelihood of greater Scottish autonomy has become a major political issue—is just across the border, in the North East of England, Scotland’s nearest neighbor or “cousin” (Fraser Citation2012).

Such close “cousins” have much in common, including a shared history, daily cross-border flows of people, for work, shopping or family visits, and common experiences of economic and social change.

Indeed, the North East has also taken heart from Scottish experiences of devolution in the past. In the 1980s and 1990s, the campaign for a Scottish assembly positively influenced the development of the campaign to set up a directly-elected assembly for the North East. Even though the proposal to create a regional “Parliament” was eventually rejected by North Easterners in a referendum held in 2004, the Scots views on the need for greater devolution, democracy and civic engagement left their mark on subsequent political debates in the region (Tomaney Citation2005).

As noted in the Introduction to this special edition, despite geographical proximity and a number of shared features, the past relationship between Scotland and the North East has also been characterized by conflict and contestation. Any quick historical glance at cross-border relations for most of the early modern period (between the 11th and 16th centuries) would capture the many conflicts and battles between the rival kingdoms of Scotland and England to settle territorial disputes. The “bloody” borders were also the site of cross-border raids and skirmishes between powerful families—the Border Reivers (Crofton Citation2015).

Despite over 300 years of peace following the Treaty of Union in 1707, it is noticeable that these historical themes of conflict and collaboration still operate as an influential narrative within which the North East has understood—and interpreted—the contemporary rise of a much more powerful Scotland. Albeit one that in the modern era sees the agenda being more about economic competition than military conquest.

Thus, in the run-up to the 2014 referendum, both political and business leaders in the North East of England became increasingly concerned that if Scotland gained greater control over the levers of economic development, and for example, become significantly more attractive as a location for inward investment, this would be to the detriment of the North East who would lose out in the battle for foreign direct investment. There is also a distinct lack of trust between politicians on both sides of the border. As Iain McLean argues elsewhere in this journal, North East Labour MPs in particular, have been long opposed to a more powerful Scotland, to Scottish nationalism more generally and to the SNP in particular. This animosity was well developed even before the wipe-out of the party’s electoral base in Scotland in the 2015 General Election when the SNP won 56 out of 59 seats in Scotland, including 40 of Labour’s 41 seats.

However, while there is a strong sense in the region that a resurgent Scotland poses a considerable threat to economic development south of the border, there are others in the North East (including politicians and business leaders) who are genuinely interested in using the opportunities afforded by the radically altered circumstances north of the border, to examine areas where greater cross-border collaboration would be of mutual benefit. Following the September 2014 referendum, the businessman chairing the North East Local Enterprise Partnership—set up in 2011 to promote private sector-led economic growth in the region—highlighted how his meeting with the Scottish Government’s Minister for Energy, Enterprise and Tourism, Fergus Ewing MSP, saw them identifying a number of key areas where they both have a common interest. In short, “this is about two key economic regions working together to improve the economic growth prospects for its people” (Paul Woolston, quoted in North East Local Economic Partnership Review Citation2014).

The Scottish Government has also been keen to emphasize that a more powerful Scotland would not only maintain close ties with the North of England, but that this would lead to new opportunities for collaboration and joint-working. During the referendum campaign the, then, Deputy-First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon looked forward to:

An independent Scotland having a relationship of friendship and co-operation with all our neighbours in these islands, including our next-door neighbours in the North of England. (quoted in, The Journal January 8, Citation2014)

This article reflects the approach to the study of borders initially discussed in the introduction to this special edition that recognizes, inter alia, the material and symbolic importance of borders, their capacity to both divide and connect and the need for their meaning to be constantly redefined and reconstructed in contemporary time and place. In doing so, the article locates recent policy debates on Anglo-Scottish cross-border relationships within the context of—often deeply-rooted—border “narratives” which serve to shape and influence how the contemporary border is interpreted and understood. Such border narratives are best viewed as an amalgam of “personal and collective ideas” and are also “representations of places” (Lauren Citation2012, 42). As Holt argues in her contribution to this volume, such narratives are also an important component in the forming of identity—particularly in the borderland communities of Scotland and northern England where the contemporary “memorialising of historic, regional events and customs continually rehearse a borderland identity which acquires particular meanings at different times and for different groups and individuals” (Holt, Citationforthcoming). This echoes Berger’s view that, “within national histories, borderlands play an important role’ as it is at the border that the national defines itself most rigorously” (Berger Citation2009, 497).

Three particular narratives are identified in this article, each firmly rooted in history, capturing both a sense of place and people and offering often competing contemporary visions of the nature of the Anglo-Scottish border, cross-border relationships and the significance of the borderland communities. These narratives—of the Conflictual, Competitive and Collaborative border—can also be located within O’Dowd’s seminal discussion of appropriate border metaphors which capture the “enduring importance of borders as well as their complex, ambiguous and often contradictory, nature” (O’Dowd Citation2001, 6). Particularly relevant to this discussion is the contrast between borders as “bridges” or “barriers:” the former capturing notions of collaboration, co-operation and co-existence, the latter, reflecting division, conflict, and difference.

In examining these narratives, the discussion will, firstly, examine the contemporary strength of the traditional conflictual narrative that a more powerful Scotland will undermine the North East, particularly in relation to the economic fortunes of an English region that still faces major challenges in promoting economic growth. The article will then consider the competitive border and chart how the independence referendum north of the border has been used as a springboard to argue for greater powers to be devolved to the North East. In the next section, the article will examine how the discursive space created by the referendum campaign (and outcome) has created the conditions within which a collaborative narrative—highlighting how Scotland and the North East of England have a shared history and common social and economic challenges—has emerged. The article will conclude by considering whether the emergence of a new cross-border relationship between the “Northern Lights” allows the border to be conceptualized more as a bridge than a barrier, particularly given the UK’s recent decision to leave the EU.

The Conflictual Border

If a new settlement gives powers to Scotland which are seen as contributing to the long-term prosperity of Scotland, parts of the UK (for example the North-East) are likely to become very ill at ease with this settlement. (Royal Society of Edinburgh & British Academy Citation2015, 53)

The animosity is both economic and political. Thirty-seven years before the 2014 Referendum, North East Labour MPs helped undermine the then Labour Government’s unsuccessful attempt to set up a separate Scottish Assembly. In helping to vote down the 1977 Parliamentary bill on devolution, they then voted to introduce a very challenging (and ultimately unachievable) requirement in the new bill that a minimum of 40% of the electorate had to vote “Yes” in the referendum. At the time, North East politicians were furious that despite the region being poorer than Scotland, “ … public spending in the region was lower, not higher, than in Scotland”, and that giving the Scots their own devolved assembly “would add insult to injury” and would merely serve to “entrench Scotland’s advantage” (McLean, Gallagher, and Lodge Citation2013, 186).

The 1970s also saw the creation of the Barnett Formula, a fiscal mechanism which had the effect of awarding greater levels of public expenditure per capita to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland than to England (see the discussion on the Formula in Mclean’s article in this volume). The operation of the funding formula has been the cause of a long-standing grievance in northern England due to the consequent advantages that Scotland enjoyed in relation to public expenditure allocations. Figures suggest that through this calculation, Scots enjoy a £733 per capita advantage over North Easterners (BBC September 24, Citation2014b). For North East businesses, “The Barnett Formula is an anachronism that leads to an entirely un-strategic distribution of resources and investment between different parts of the UK” (North East Chamber of Commerce [NECC] Citation2014, 2).

In evidence to the 2009 Calman Commission (on Scottish Devolution), the business organization, the NECC, expressed their concern over any further devolution of fiscal responsibilities to the Scots that would allow them to gain advantage over the North East through lowering taxation rates north of the Border (NECC Citation2009). Indeed, prior to the announcement of the 2014 referendum, many political and business leaders in the region were already very concerned about the existing advantages enjoyed by the administration in Edinburgh. For example, it was strongly felt in the region that Amazon’s decision to invest in Scotland—rather than in North Tyneside—was heavily influenced by the £1.8m subsidy provided to the company by Scottish Enterprise (Schmuecker, Lodge, and Goodall Citation2012).

However, it was the UK Government’s decision in 2012 to allow the Scots to vote on full independence that really stoked-up feelings in the North East and saw niggling concerns become full-blown anxieties.

While not all were taken-in by scare stories that independence would lead to border guards and passport controls (Daily Telegraph October 31, Citation2013), three particular worries were widely held. Firstly, that an independent Scotland would reduce the rate of Corporation Tax—by up to three percentage points—which would reinforce their competitive advantage with regard to inward investment. Secondly, that an independent Scottish Government would reduce or abolish Air Passenger Duty (APD) and that this would have implications for the North East’s main airport in Newcastle. Thirdly, if an independent Scotland was not permitted to join a currency union with the rest of the UK, would North East businesses trading with Scotland suffer from any variation in exchange rates and from the potential administrative costs of dealing with two different currencies?

Some of these concerns were certainly overplayed. In practice, the room for manoeuver for an independent Scotland to cut taxes would be limited by the scale of the recession, EU regulations on state spending, and the level of spending required to support the extensive welfare state in Scotland (McLean, Gallagher, and Lodge Citation2013). However, for a range of stakeholders in Northern England, such attitudes are rooted in genuine anxieties and as such, are hard to dismiss. They are also reinforced by the feeling that the North is in an uncomfortable position, caught between an increasingly confident neighbor north of the border—poised to secure greater power and influence—and a prosperous and powerful London, led by its own directly elected mayor.

It is not surprising therefore, that on the morning of September 19, 2014, many political and business leaders in the North East breathed a collective sigh of relief when voters in Scotland rejected independence. However, this feeling didn’t last for long, as the recommendations of the Smith Commission, and subsequently, the UK Government, confirmed greater fiscal devolution on the rates and bands of income tax, Air Passenger Duty, the Aggregates Levy, and assignment of VAT revenues (HM Government Citation2015).

For the North East Chamber of Commerce, there was a general concern over the lack of any post-referendum consultation with North East—the region most likely to be affected by a more powerful Scotland. More specifically, there was hostility over the continuation of any form of the Barnett Formula (in a context where the Scots would be given greater powers to run their own affairs) and a rejection of “devolving duties which could impact upon consumer behaviour such as air passenger duty” (NECC Citation2014). Granting the Scottish Parliament powers to abolish APD at Edinburgh airport remains a particular concern: The Chief Executive of Newcastle Airport has estimated that 1,000 jobs could be at risk in the region and £400 million drained from the region’s economic output in the next 10 years (The Northern Echo February Citation25, Citation2015a).

The momentous events of 2014–2015 have also sharpened cross-border political hostilities. Even before the SNP effectively wiped-out the Labour Party in Scotland in the May 2015 General Election, there was no love lost between the Nationalists and Labour MPs in the region. Given that one leading North East MP (and former Labour Government minister for the North East), Nick Brown, had expressed his “hatred of both nationalists and nationalism” before the General Election result, it is perhaps not surprising that Nicola Sturgeon’s post-election rallying call, that a more powerful SNP group at Westminster would back North East plans for greater investment in road and rail infrastructure, was treated with a large measure of contempt by North East Labour politicians in particular (The Chronicle April Citation26, Citation2015). During the 2015 General Election campaign, there was also anger from North East Labour politicians that the Conservative Party had been able to use such overtures to raise the specter of the SNP propping-up an Ed Miliband-led Labour Government as leading, amongst other things, to the decommissioning of Britain’s nuclear deterrent and the granting of another independence referendum in the near future (The Guardian April 9, Citation2015).

Above all, there has been a genuine fear that the “wipe-out” of Labour north of the border will mean an erosion of traditional allegiances to Labour in its one remaining heartland, the North East of England. A major concern is that the move away from Labour (particularly in the older industrial areas of the West of Scotland) is less about pro-independence sentiments and more a rejection of the “austerity” agenda and an acceptance that the Labour Party no longer provides a clear vision of the more equal society that Scots wish to live in (Shaw Citation2015). While the May 2016 elections to the Scottish Parliament saw the SNP remain the governing party—albeit without an overall majority and reliant on support from The Green Party—the Labour Party’s decline continued, with the party losing 13 MSPs and being pushed into third place by a resurgent Conservative Party who more than doubled their number of MSPs (The Independent Citation2016). For the North East of England, the considerable unease that the question of full independence had not been settled “once and for all” has been borne out by the First Minster’s determination that:

Scotland will have the ability to reconsider the question of independence and to do so before the UK leaves the EU – if that is necessary to protect our country’s interests. So, I can confirm today that the Independence Referendum Bill will be published for consultation next week. (Nicola Sturgeon, MSP, quoted in BBC October 13, Citation2016)

The Competitive Border

Scotland’s capacity for policy flexibility is in marked contrast to those of English regions, for which devolution is extremely limited and tightly controlled by Whitehall … . Further extending this without ensuring English policy much more effectively considers the conditions of all regions would be damaging to the North East. (North East Chamber of Commerce Citation2014, 2)

The threat of invasion from the North and distance from the South, conditioned the socio-economic development of the region and its political identity. Frequently, the threat of invasion was more theoretical than real – but the region’s political class became adept at painting a picture of Scottish threats as a means of guaranteeing political autonomy and fiscal privilege. (Tomaney Citation1999, 78)

In considering such asymmetry between powers and resources available on the different sides of the border, it is also important to note that the likelihood of an even greater imbalance in the powers and resources available on either side of the border has come at a time when the English regions no longer have their Regional Development Agencies. These powerful quangos possessed considerable resources and institutional capacity, were abolished by the Coalition Government in 2011 and only partially replaced by the much more geographically and financially circumscribed Local Enterprise Partnerships (Pugalis and Bentley Citation2013).

The demand for greater devolution of powers within England generally, and specifically to the North East, formed a key component in the region’s responses to both the Referendum and to the recommendations of Smith Commission—set up by the UK Government after the referendum result to bring forward proposals for greater devolution to Scotland (The Smith Commission Citation2014). One leader of a major North East Local Authority felt that:

It is now time to have a full debate about the devolution of power throughout the UK. If additional funding is guaranteed to meet the needs of Scotland it is reasonable to ask that funding is also guaranteed to meet the needs of northern England in areas such as transport and the economy. (Councillor Simon Henig, Leader of Durham Council quoted in The Northern Echo September Citation20, Citation2014)

The widespread support for more powers to be devolved to the North East in the light of further Scottish devolution has also chimed with the UK Government’s “Devolution Deal” approach—within England—through which new Combined Authorities are to be created. This approach to devolution sees several adjoining local authorities coming together in a larger grouping, led by a newly-created office of a directly-elected mayor, and requesting greater devolution from central government. The areas to be devolved include economic development, regeneration, housing, transport, skills, the integration of health and social care, aspects of children’s services, land development and planning, policing, control over the fire and rescue services, and retaining locally the surplus generated by business rate growth (National Audit Office Citation2016).

Through this deal-making process, the seven individual councils in the North East area are planning to join together—as the North East Combined Authority (NECA)—in order to have such a devolution bid agreed by the UK Government. The new body was to cover the local council areas (both urban and rural) of Northumberland, Durham, Newcastle, Sunderland, Gateshead, North Tyneside and South Tyneside and requested greater powers and resources in a number of areas ().

Figure 1. A More Powerful North East: The Devolution Deal for the North East Combined Authority. Source: HMT & NECA (Citation2015).

The proposed creation of a new combined authority partly reflects the outcome of pressures on the UK Government to provide a devolution “dividend” to the regions and sub-regions of England in the light of greater powers to Scotland. In addition, however, it represents a response to more long-term concerns about a political system in the UK that has traditionally been viewed as excessively centralized compared to similar European nations. Hence, in the UK, the proportion of tax set at local level is equivalent to only 1.7% of GDP, compared to nearly 16% in Sweden, 15% in Canada, nearly 11% in Germany and 6% in France (Martin et al. Citation2016).

This strengthening of the powers available to the North East of England—and the creation of larger political bodies—are likely to be important contributors to a more balanced relationship with Scotland, a “stateless nation” (Law and Mooney Citation2012) that has its own parliament, political executive, First Minister, legal, educational and religious systems. Particularly important to challenging existing cross-border asymmetries in powers is the potential creation of a single mayoral executive who will be directly elected to speak for the NECA. The creation of such a political role offers the possibility that whoever speaks for the North East region in any negotiations with the Scots has a suitably broad mandate, a greater range of powers and is thus able to enjoy at least a measure of parity with Scottish politicians (Fenwick and Elcock Citation2014).

The devolution of greater powers has been viewed as a necessity by some political and business leaders if the North East is to be able to compete on a “level playing field” with Scotland for resources, jobs and inward investment. According to the Chair of the Federation of Small Businesses in the North East, speaking just after the SNP’s triumph in the May 2015 General Election “There is a real danger for this region in the concessions the Scots are now going to get … we need to shout loudly to ensure the Government consider what the implications are south of the border” (Ted Salmon quoted in The Northern Echo May 9, Citation2015b). However, it is also noticeable (See ) that one of NECA’s devolution requests is that the new body is able to have the flexibility, in a number of areas, in order to facilitate a more collaborative approach with Scotland. It is to this issue that we now turn.

The Collaborative Border

We are so used to being governed by the South East that we have tended to forget just how much we have in common with the Scots in terms of our social and economic challenges. If we could forget that imaginary line on the map, we would see benefits from cross-border co-operation. (North East Local Government Officer, quoted in Shaw et al. Citation2013, 20)

In this sense, the Anglo-Scottish border (although an “internal” border within the UK) has served more as a barrier than a bridge (McCall Citation2011). Partly, this can be explained by the level of policy asymmetry caused by the previous devolutionary initiatives in Scotland, partly by the lack of political interest shown on both sides of the border, and also by the North East’s traditional antipathy towards Scottish nationalism and the SNP.

However, the referendum campaign—and its outcome—marked a step change in the relationship between Scotland and North East England. The renewed focus on the nature of the Anglo-Scottish Border during—and after—the referendum campaign has served to strengthen a narrative that highlights the many common social, economic and political bonds between North East England and Scotland. Looking back on the last decades of the 20th century, one former Labour MP for a Scottish constituency looked back on an era when:

Scotland and the north-east stood together against the poll tax and pit closures. People recognised then, as we do now, that any political change that we hope for can be reached only through the unity of shared identity and interests. (Gordon Banks, MP, quoted in Hansard March 4, Citation2014: Column 213 WH)

This collaborative narrative has allowed political and business leaders (on both sides of the border) to consider how joint working could be of mutual benefit within a centralized polity and unbalanced economy dominated by London and the wider South East. A key part of this shift is the emergence of an approach, that accepts the inevitability of economic competition, but which also highlights how the changed circumstances can lead to new forms of cross-border working. As one business representative has argued:

There are concerns over the way Scotland might use greater powers. Lower corporation tax is one possibility, while reduced air passenger duty could have an impact on our international flights. But … there are at least as many opportunities as threats that come from being on Scotland’s doorstep. We are each other’s nearest market and have much more to gain from improving trade across the border than from a scramble for marginal competitive advantage. (Ross Smith, Policy Officer, North East Chamber of Commerce, quoted in The Northern Echo August Citation29, Citation2013)

The politicians running local councils on either side of border are also increasingly seeing the benefits of cross-border working. The difference in approach can be characterized in terms of a distinction between what Peck (in this volume) has referred to as a “far border” area (comprising the wider north east and north west of England) and a “near border” area defined in terms of the travel to work, shop and study area immediately adjacent to the border.

In terms of the former area, one issue under discussion is the opportunities for introducing high speed rail between Edinburgh and Newcastle. This is particularly important, as many in the region are concerned that the North East is unlikely to directly benefit from the UK Government’s existing high speed rail proposals within England. As Newcastle’s council leader acknowledged in the context of talks with Edinburgh city council leaders, “It is as important for us to be connected to Scotland as it is for us to be part of the route to London, and we need to bear that in mind” (Councillor Nick Forbes, quoted in The Journal January 25, Citation2013). Opportunities for dialogue between the North East and Scotland have also been strengthened by Glasgow joining the UK Core Cities Group, which now comprises England’s eight largest urban economies outside London—Newcastle, Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Nottingham and Sheffield—along with Glasgow and Cardiff (Core Cities Citation2014).

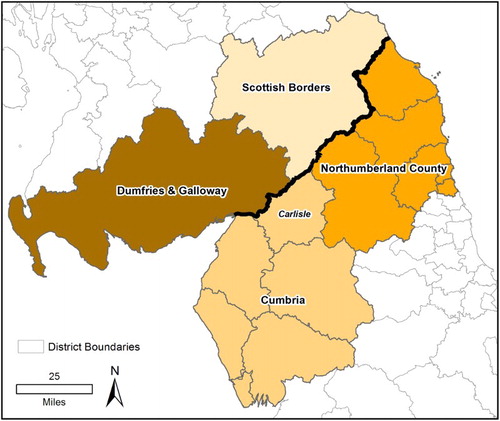

In terms of the latter, one other example of this new cross-border approach is the Borderlands Initiative which brings together the five local councils nearest the border, Northumberland, Cumbria, Carlisle, Dumfries and Galloway and Scottish Borders (). While partly influenced by the earlier Border Visions network that met for a short period in the early 2000s (see the article by Peck in this volume), the more recent Borderlands Initiative is a product of the contemporary debates on Scottish independence and has its genesis in the 2013 report, Borderlands: Can the North East and Cumbria benefit from greater Scottish Autonomy, which was commissioned by the Association of North East Councils (Shaw et al. Citation2013). This report captured how the combination of the debate on Scottish independence, and the continuing search for a post-regional future for sub-national governance in the North East, provided opportunities to consider new, creative, cross-border approaches to boosting economic development across the Borderlands—both on the east and west sides of the borderline.

The Scottish Government was quick to respond to the positive nature of the report, and particularly highlighted their support for the recommendation:

The practical co-operation which we’re starting to see under Borderlands is – rightly – being taken forward primarily by local authorities. But any independent Scottish Government would support it wholeheartedly. This Government, if elected as the government of an independent Scotland, will work with local authorities to establish a borderlands economic forum. And we will nominate a lead minister to work with such a body. (Alex Salmond MSP, quoted in New Statesman March 5, Citation2014)

Crucially, the recommendations of the 2013 Borderlands report were positively received by the five councils on both sides of the Border. This resulted in: three meetings of council leaders being held in 2014–2015; the creation of a Borderlands Steering Group to develop the approach further; and the commissioning of additional research to establish an evidence-base upon which to identify the sectors and projects that would benefit from a Borderlands approach.

For the councils concerned, there is a clear case for collaboration on the basis of a refashioned Borderlands economic area:

The council areas are similar on many economic and demographic indicators and, by extension, experience similar economic problems.

They all have a large proportion of their populations living in rural areas, which provide challenges in relation to accessibility, connectivity with regards broadband and mobile infrastructure, transport infrastructure, and the economic future of market towns.

There are particular problems with low level of wealth creation, low pay, a lack of representation of high growth economic sectors, the outmigration of young people, and an ageing population.

However, collaboration is not just about tackling problems but also about making the most of the Borderland’s considerable assets:

The area has a population of over one million people and incorporates almost 10% of land area of Great Britain.

There are high levels of self-employment in the area and the growth in micro and small businesses are opportunities which could be exploited.

There are also opportunities to develop energy production, both on and off shore, and adding value to the tourism product.

Just under 25% of the workforce work in agricultural, forestry and fishing businesses: a sector that provides a potential opportunity given the change in consumer demands for higher quality, locally-sourced, produce over mass production.

The issue of “voice” is also important. The Borderland authorities working together could add substantial strength to a “northern voice” that embraces Scotland and northern England, in the face of the continuing dominance of London and the South East. (Source: Shaw et al. Citation2015)

The Borderlands report also emphasized how the five councils could seek to agree sector-based collaboration in areas of mutual benefit. In subsequent discussions, the councils have identified three sectors of strategic importance with growth potential and in which collaboration could add value.

Tourism is a significant sector for all of the economies and communities in the Borderlands. It builds on the region’s key natural assets, is a major employer, and offers linkages with other areas of the local economy. It is also recognized that the sector is currently limited by fragmented tourism operations and administration and that there is considerable scope to develop common marketing themes and opportunities across the Borders.

Another key sector is Forestry—the Borderlands contain the largest most productive and fastest growing forests and woodlands in the UK. Collaboration in this sector could also include forging relationships between companies including supply chain logistics and timber transport investment. The sector also provides significant tourism opportunities such as “Dark Skies” projects in two of the areas main forests

The third sector, Energy, offers the potential of building on the areas extensive renewables expertise in onshore and offshore wind energy production, in tidal hydro-electric and biomass opportunities. This is in addition to the large nuclear power sector based in the west of the Borderlands and the potential for energy capture and storage.

In early 2016, the local councils and national government bodies involved in the development of the Borderlands Initiative began to examine the different strategic and governance options. Following the recommendations of a second commissioned research report (Shaw et al. Citation2015), it is acknowledged that given the already “cluttered” governance arena, with a myriad of organizations, a plethora of strategies, and a number of cross-border asymmetries, it would be more appropriate to view the “Borderlands” collaboration as a “light-touch” flexible network (rather than a “formal” legal partnership). The network would serve to: improve cross-border communication; share intelligence; strengthen co-ordination; bring the right people together to collaborate on specific projects; share good practice; and, provide for a common voice on issues on mutual concern. To illustrate this, the report identified 10 potential areas in which the pursuit of a cross-border would add value or “make sense” ().

Figure 3. Ten Collaborative Opportunities in the Anglo-Scottish Borderlands. Source: Shaw et al. (Citation2015, 5).

Such a realistic, common sense, approach also recognizes the undoubted challenges facing the Borderlands Initiative. As both Peck and Columb argue elsewhere in this special edition, joint-working across the border will be challenging in areas (such as planning) where there are major cross-border differences in terms of regulatory systems, legal frameworks, or variations in funding regimes. Where programs are already up and running, it is important that any separate Borderlands approach does not lead to overlap or have a “displacement” effect. The Borderland authorities are—necessarily—leading on their own, council-specific, developments and other collaborative initiatives which would clearly impact upon their use of the vehicle of Borderlands. For example, a number of economic development objectives may be more fruitfully pursued through other mechanisms such as Combined Authorities, “City Deals” (O’Brien and Pike Citation2015), or via direct relationships with national government departments on both sides of the border.

For the North East of England, the political “space” created by the clearing away of the English regional institutions after 2010 has encouraged consideration of new and flexible place-based approaches to economic development that may not have been possible under the old geography and structures. It also reinforces the importance of the political dimension in creating and reshaping economic boundaries and can provide a response to a situation where functional economic geographies fail to map on to the institutional structures that policymakers propose and form (Pugalis and Bentley Citation2013, 8).

Conclusion: The Anglo-Scottish Border—Bridge or Barrier?

This article captures a border undergoing a process of “rebordering” which will radically alter the nature of the Union between the two countries set up in 1707. Gone are the days when the Anglo-Scottish border was regarded as a relatively unimportant “internal” boundary within the United Kingdom. In the next few years, additional devolution and the impact of UK exit from the EU will further re-enforce the divergence between the two, and potentially push the UK further down the road towards a more federal political system in which the English regions, Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland become much more autonomous. Indeed, the momentous events of the last two years may even prefigure the eventual break-up of the United Kingdom into separate states with different relationships with the rest of Europe.

Such changes have profound implications for Scotland’s relationship with its “close cousins” across the border in the North East of England. In analyzing the changing nature of cross-border relations the article has focused on three border narratives based on “conflict,” “competition” and “collaboration” which both capture different contemporary perspectives on the nature of border change and draw upon customs, traditions, and representations of place that are deeply rooted in border history.

Such narratives clearly offer different interpretations of the implications of border change. The conflict narrative captures a clear sense of “difference” and embodies a zero-sum view—from many in the North East—that their region’s economic fortunes would suffer if Scotland had even greater fiscal and economic powers. The competition narrative is less hostile and more pragmatic—using the granting of more powers to Scotland to highlight the urgency of devolving real powers to the constituent parts of England. A more positive narrative, stressing the common bonds and shared traditions between Scotland and the North East, highlights how a region that has traditionally spent its time looking “south” for support and encouragement, should now look “north.” Finding common causes and collaborative opportunities has been the impetus behind the Borderlands Initiative, where council leaders in the five local authorities adjacent to the Border, an area of 10% of the UK and more than one million people, are working to create a partnership to ensure greater cross-border economic collaboration and to make a more effective case for “Devo Borders.” The desire to work with the Scots—and see the Anglo-Scottish border more as a “bridge” than a “barrier”—is in keeping with the spirit of the times. Crucially, this route also offers real opportunities for the North East to redefine itself, to rediscover its identity and, crucially, to find its collective voice.

However, more recently, the UK’s decision to leave the EU has further compounded the contestability of border narratives by potentially leading to an outcome which leads to a “Yes” vote in a second referendum on an independent Scotland. In turn, the desire—North of the border—to remain in the EU, offers the possibility for a new international border between two separate countries (one in the EU and one outside). Such an outcome creates considerable uncertainties for any attempt to develop a new relationship between Scotland and the North East of England. One particular concern is that a number of the collaborative opportunities across the “borderlands” are in areas such as rural development, farming, tourism and renewable energies, in which continuing EU investment and support are vital. Nor is the prospect of a “hard” Anglo-Scottish border with passport checks and currency converters likely to appeal to those crossing the border on a daily basis for work, shopping or family visits; while the likelihood of different tax or even currency regimes will make it much harder for cross-border economic business linkages and activities. The prospect of an emboldened and empowered North East—ready to talk to Scotland on a more equal basis—may also has also receded after the referendum result, as North East council leaders concerned that without EU funding several of the key features of the devolution deals would be hard to implement are beginning to question the merits of a combined authority model more generally (The Chronicle Citation2016).

A timely reminder perhaps, that “dominant” border narratives are not fixed, but subject to constant reinterpretation and reshaping in the context of profound political social and economic change. In such a context, the appropriateness of the “bridge” or “barrier” metaphors to illustrate the changing nature of the Anglo-Scottish border is likely to remain highly contested and contingent—a symbol of the growing importance of examining the boundaries between “stateless nations” in border studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Methodological Note: This article draws upon a variety of sources. These include original research commissioned by the Association of North East Councils and Cumbria County Council. The two reports, Shaw et al. (Citation2013) and Shaw et al. (Citation2015), include both quantitative and qualitative data and a series of policy recommendations. The author also had access to internal policy documentation from the relevant organizations. The theoretical and conceptual insights in the article draw upon presentations and discussions within the ESRC-funded Seminar Series, Close Friends? Assessing the Impact of Greater Scottish Autonomy on the North of England. Given the contemporary—and rapidly evolving—nature of the issues under examination, the article draws upon largely factual information located within a number of websites, including specialist news organizations (such as the BBC), the UK Parliament and UK Government departments. The views contained in the article are those of the author and not of any of the commissioning organizations.

References

- BBC. 2012. Fears North-east England is ‘Losing Jobs’ to Scotland. October 9. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-19873780.

- BBC. 2014a. North East Poll Backs Move of Powers to Local Areas. November 5. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-29900474.

- BBC. 2014b. Why does Government do Less for the North East than Scotland? September 24. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-29343927.

- BBC. 2016. SNP’s Nicola Sturgeon Announces New Independence Referendum Bill. October 13. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-37634338.

- Berger, S. 2009. On the Role of Myths and History in the Construction of National Identity in Modern Europe. European History Quarterly 39: 490–502. doi: 10.1177/0265691409105063

- Cabinet Office. 2014. The Implications of Devolution for England. House of Commons: Cmd 8969. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/387598/implications_of_devolution_for_england_accessible.pdf.

- Core Cities Group. 2014. Historic Moment as Core Cities Welcome Glasgow to their Group. http://www.corecities.com/news-events/historic-moment-core-cities-welcomes-glasgow-their-group.

- Crofton, I. 2015. Walking the Border: A Journey between England and Scotland. Edinburgh: Birlinn Press.

- Daily Telegraph. 2013. Scottish Independence: Passport May be Required to Enter Scotland. October 31. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/scotland/10416786/Scottish-independence-passport-may-be-required-to-enter-Scotland.html.

- Fenwick, J., and H. Elcock. 2014. Elected Mayors: Leading Locally? Local Government Studies 40, no. 4: 581–99. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2013.836492

- Fraser, D. 2012. Mind the Gap on the Northern Line. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-20316256.

- Hansard. 2014. Westminster Hall debate on Scotland and North-east England Post-2014. Column 213WH. Tuesday. March 4. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmhansrd/cm140304/halltext/140304h0001.htm.

- HM Government. 2015. Scotland in the UK: An Enduring Settlement. Cm 8990. London: HMSO.

- HM Treasury and the North East Combined Authority. 2015. The North East Devolution Agreement. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/472187/102915_DEVOLUTION_TO_THE_NORTH_EAST_signed_pdf.pdf.

- Holt, Y. Forthcoming. Performing the Anglo-Scottish Border: Cultural Landscapes, Heritage and Borderland Identities. Journal of Borderlands Studies.

- House of Commons. 2015. Our Borderlands – Our Future. Sixth Report of the Scottish Affairs Committee.

- House of Commons Library. 2015. The General Election 2015. Briefing Paper No. CBP7186. July 28. file:///C:/Users/egks1/Downloads/CBP-7186%20(1).pdf.

- Lauren, K. 2012. Fear in Border Narratives: Perspectives of the Finnish-Russian Border. Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore 52: 39–62. https://www.folklore.ee/folklore/vol52/lauren.pdf.

- Law, A., and G. Mooney. 2012. Devolution in a ‘Stateless Nation’: Nation-building and Social Policy in Scotland. Social Policy & Administration 46, no. 2: 161–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2011.00829.x

- Martin, R., A. Pike, P. Tyler, and B. Gardiner. 2016. Spatially Rebalancing the UK Economy: Towards a New Policy Model? Regional Studies 50, no. 2: 342–57. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1118450

- McCall, C. 2011. Culture and the Irish Border: Spaces for Conflict Transformation. Cooperation and Conflict 46: 201–21. doi: 10.1177/0010836711406406

- McLean, I., J. Gallagher, and G. Lodge. 2013. Scotland’s Choices: The Referendum and What Happens Afterwards. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- National Audit Office. 2016. English Devolution Deals. London: Department for Communities and Local Government and HM Treasury. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/English-devolution-deals.pdf.

- New Statesman. 2014. New Statesman Annual Lecture. March 5. http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2014/03/alex-salmonds-new-statesman-lecture-full-text.

- North East Chamber of Commerce. 2009. Evidence to the Commission on Scottish Devolution. Durham City: Calman Commission. http://www.commissiononscottishdevolution.org.uk/uploads/2009-03-02-north-eastchamber-of-commerce.pdf.

- North East Chamber of Commerce. 2014. Evidence to the Smith Commission on Scottish Devolution. https://www.necc.co.uk/policy/policy-library.

- North East Local Enterprise Partnership. 2014. North East LEP to work with Scotland to Boost Economy. http://nelep.co.uk/north-east-lep-work-scotland-boost-economy.

- O’Brien, P., and A. Pike. 2015. City Deals, Decentralisation and the Governance of Local Infrastructure Funding and Financing in the UK. National Institute Economic Review 233: 14–26. doi: 10.1177/002795011523300103

- O’Dowd, L. 2001. Analysing Europe’s Borders. IBRU Boundary and Security Bulletin, Summer. file:///C:/Users/egks1/Downloads/bsb9-2_odowd.pdf.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2013. Regions and Innovation: Collaborating Across Border. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Pike, A. 2002. Post-devolution Blues? Economic Development in the Anglo-Scottish Borders. Regional Studies 36, no. 9: 1067–82. doi: 10.1080/0034340022000022189

- Pugalis, L., and G. Bentley. 2013. Economic Development Under the Coalition Government. Local Economy 28: 665–78. doi: 10.1177/0269094213506800

- Royal Society of Edinburgh & British Academy. 2015. Enlightening the Constitutional Debate. Edinburgh: RSE.

- Schmuecker, K., G. Lodge, and L. Goodall. 2012. Borderland: Assessing the Implications of a More Autonomous Scotland. Newcastle: IPPR North.

- Shaw, K. 2015. ‘Take us with you Scotland’? Post-Referendum and Post-Election Reflections from the North East of England. Scottish Affairs 24, no. 4: 452–62. doi: 10.3366/scot.2015.0096

- Shaw, K., J. Blackie, F. Robinson, and G. Henderson. 2013. Borderlands: Can the North East and Cumbria Benefit from Greater Scottish Autonomy. Report commissioned by the Association of North East Councils: Newcastle. http://www.northeastcouncils.gov.uk/curo/downloaddoc.asp?id=589.

- Shaw, K., F. Peck, K. Jackson, G. Mulvey, et al. 2015. Developing the Framework for a Borderlands Strategy. A Report for the Borderlands Stakeholder Group. Universities of Northumbria and Cumbria.

- The Chronicle. 2015. Sturgeon Factor should not Fool North East Voters into Supporting the SNP. April 26. http://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/sturgeon-factor-should-not-fool-9116741.

- The Chronicle. 2016. Is NECA now on the Verge of Collapse Over Devolution? September 28. http://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/north-east-combined-authority-now-11947826.

- The Guardian. 2014. Scottish Referendum: Cameron Pledges Devolution Revolution after No Vote. September 19. http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/sep/19/scottish-referendum-david-cameron-devolution-revolution.

- The Guardian. 2015. Ed Miliband would ‘Barter Away’ Trident to Win Election, Say Tories. April 9. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/apr/09/ed-miliband-trident-election-labour-snp-nuclear.

- The Independent. 2016. SNP Loses Overall Majority in Scottish Parliament. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/snp-loses-overall-majority-in-scottish-parliament-a7016131.html.

- The Journal. 2013. North East Misses out on High Speed Rail. January 25. http://www.thejournal.co.uk/news/north-east-news/north-east-misses-out-high-4398759.

- The Journal. 2014. Scotland Aims to Encourage North East to Follow Devolution Lead. January 8. http://www.thejournal.co.uk/news/north-east-news/scotland-aims-encourage-north-east-6478300.

- The Northern Echo. 2013. Our Friends in the North. August 29. http://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/business/news/10631705.NECC_Column___Our_friends_in_the_North/.

- The Northern Echo. 2014. The Region’s Business and Political Leaders Consider where Scottish Referendum Decision Leaves the North East? September 20. http://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/NEWS/11485922.print/.

- The Northern Echo. 2015a. Newcastle Airport Future under Threat if Scottish Taxes are Slashed, Transport Minister Admits. February 25. http://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/news/11815610.Newcastle_Airport_future_under_threat_if_Scottish_taxes_are_slashed__transport_minister_admits/.

- The Northern Echo. 2015b. SNP Success Prompts Fears in the North-East of the Scottish Lion’s ‘Roar.’ May 9. http://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/news/12940868.SNP_success_prompts_fears_in_the_North_East_of_the_Scottish_lion_s_roar/.

- The Smith Commission. 2014. Report of the Smith Commission for Further Devolution of Powers to the Scottish Parliament. https://www.smith-commission.scot/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/The_Smith_Commission_Report-1.pdf.

- Tickell, A., P. John, and S. Musson. 2005. The North East Region Referendum Campaign of 2004: Issues and Turning Points. The Political Quarterly 76, no. 4: 488–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-923X.2005.00711.x

- Tomaney, J. 1999. In Search of English Regionalism: The Case of the North East. Scottish. Affairs 8, no. Summer: 62–82.

- Tomaney, J. 2005. Anglo-Scottish Relations: A Borderland Perspective. Proceedings of the British Academy 128: 231–48.