ABSTRACT

In 2015, Hungary commenced the building of a fence at its border with Serbia. The current article investigates the Hungarian-Serbian border fence in terms of its meaning in the two countries. Building on recent re-bordering research, it analyzes the context within which the fencing took place, stressing both the domestic and the international dimension. Based on qualitative interviews and a document analysis for Hungary and Serbia, it argues that the fence did not create a conflict between the two neighbors – instead, the international entanglement of the border led to a complex bordering process that extended bilateral relations. In Hungary, the border fortification was used for internal political motives and at the same time aimed to exclude non-European migrants. Due to political circumstances and the filter function of the fence, the Serbian government likewise managed to exploit the border fortification to its advantage. The article introduces the concept of “fencing in and fencing out” in order to analyze the control function that the fence performs on both sides of the border.

1. Introduction

In 2015, migration became an omnipresent topic of public debate in Europe. The arrival of large numbers of Syrian refugees led to the formalization of the so-called Balkan route, which allowed refugees to transit through several European countries legally (for a more detailed description of these events, see Sicurella Citation2018, 58–60). As some countries ceased to control their borders, migration movements across Europe continued to increase and at the same time became much more visible (Speer Citation2017, 2).

These events caused growing tensions between EU member states and attracted enormous media attention. Images of large groups of people marching on railway tracks and highways were central to the framing of this period as “the refugee crisis” (for a critical discussion of this term, see Rajaram Citation2015a; Cantat Citation2016, Citation2017). While the debate on the EU's borders had previously focused on the Mediterranean area, the Balkan states now became – at least for a while – the new “hotspot” and the center of public attention.

In this context, the Hungarian government started to construct a fence at its border with Serbia. The 164 km long border, which traverses mainly flat and partly marshy terrain, was entirely sealed by a double fence. Until then, the EU's southern border had been barely visible and was manifest only through images of overcrowded refugee boats. Now, the Hungarian border fence created very concrete images of physical border reinforcement, illustrating “fortress Europe” more clearly than ever. Hence, this relatively small and quite recent part of the EU's external borders – Hungary only joined the EU in 2004 – became a new symbol of the conflict over migration to Europe.

While attracting a great deal of attention in Europe and beyond, the fence is just one of a series of newly fortified borders worldwide. Indeed, it is not only the total number of border fences and walls that is increasing, but also the rate of barrier construction, with the barriers also becoming increasingly longer (Hassner and Wittenberg Citation2015). In 2017, Carter and Poast found that “out of the sixty-two total man-made border walls constructed since 1800, twenty-eight have been constructed since 2000” (Carter and Poast Citation2017, 240). Taking this phenomenon into account, research on national borders has shifted from the idea of a “borderless world” (Ohmae Citation1990), which was predominant in the 1990s, to a debate on the process of re-bordering (Rosière and Jones Citation2012; Vallet and David Citation2012; Hassner and Wittenberg Citation2015; Brown Citation2017; Carter and Poast Citation2017; Dzihic and Günay Citation2018).

This article analyzes the Hungarian border fence as a case study that exemplifies the broader trend of re-bordering. The relatively recent fortification of this border makes it possible to investigate the motives expressed by the actors involved, the functions that the fence fulfills for them, and the context of the border closure. The research is based on interviews with governmental and nongovernmental actors in Hungary and Serbia. Thus, by comparing perspectives from both sides of the border, the case study contributes to a better understanding of what takes place on each side of a newly fortified border.

The article is structured as follows. After a brief overview of ongoing debates in border research (Section 2) the data and methods are explained (Section 3). Section 4 then describes the context of the border fortification. The empirical results are presented and discussed in the subsequent parts (Sections 5 and 6), before concluding in the last section (Section 7).

2. Rethinking the Line: Research on Borders and Re-bordering

Although the sphere of border studies has a strong tradition in geography, the current research on borders is diverse and can be found in very different fields (Johnson et al. Citation2011). The disciplines of geo-politics, political science, economics, sociology, security studies, history, and social and cultural anthropology have all contributed to the current research on borders. Case studies, often focusing on regions such as the southern and northern United States borders (Rodriguez Citation2006) or the Finnish border regions (Paasi and Prokkola Citation2008), are very common and typically address questions concerning borderlands, cross-border relations, or the link between physical and symbolic boundaries (for an overview, see Newman Citation2012).

In the 1990s, along with a wave of literature on globalization, the perspective on borders and territoriality changed, raising the question of whether border research was still necessary in a world where borders were seemingly becoming insignificant (Newman Citation2006a, 172). Yet after a period of debate on the effects of globalization, when many assumed that national borders would become permeable or would even disappear, research on borders has experienced a renaissance. It is now obvious that borders still play a role as “the lines that continue to separate us” (Newman Citation2006b). The “reclosing of borders” (Newman Citation2006a, 171) has been strongly linked to security and securitization and – especially in the USA – to the events of 9/11 and the global “war on terror” (Newman Citation2006a; Ackleson Citation2012; Jones Citation2012).

Recent literature dealing with borders includes debates on not only the phenomenon of these new border fortifications, but also the process of simultaneous de-bordering and re-bordering: while the number of border fences and walls is increasing worldwide, some people are nevertheless experiencing borders as more and more permeable. This has led to a situation where parts of the world's population can move quite freely across borders whereas others experience borders as barriers that block their movement (Mau et al. Citation2015). Borders work as “semi-permeable filters” (Mau et al. Citation2006, 18) that allow some movements while blocking others.

Starting from these observations, recent literature has consequently sought to answer the question of “why do states build walls?” (Carter and Poast Citation2017). Different authors have sought to understand what types of states construct walls and what the driving factors for constructing them are. Hassner and Wittenberg define the new border fortifications as follows:

Fortified boundaries share three qualities that distinguish them from other types of borders or fortifications. First, their primary function is border control, not military or territorial demarcation. Second, they are physical barriers opposed to virtual, symbolic, or declaratory boundaries. Third, they are asymmetrical in origin and intent. (Hassner and Wittenberg Citation2015, 160)

Wall construction is explained by cross-border economic disparities. […] We find that economic disparities have a substantial and significant effect on the presence of a physical wall that is independent of formal border disputes and concerns over instability from civil wars in neighbors. (Carter and Poast Citation2017, 240. With regard to economic disparity and fortified borders, see also Moré Citation2011)

While these analyses make a very important contribution to understanding the current trends of re-bordering, they mostly focus on external effects, such as economic disparities, the (perceived) threat of terrorism, or the prevention of migration as reasons for border fencing. Domestic motives for fortifying borders have been neglected. One exception is Wendy Brown, who has identified the desperate search for sovereignty as the main reason for building walls. She regards contemporary wall building as “theater pieces for national populations specifically unsettled by global forces threatening sovereignty and identity at both the state and individual level” (Brown Citation2017, 9).

What Brown has addressed in her work is the importance of identity for border fencing. The link between borders and identity has been discussed extensively in research. As identity is not possible without creating boundaries (Barth Citation1996), humans need to use categories to differentiate one group from another (Jenkins Citation2004) and “the Other” thereby serves as the antithesis of their own community (Said Citation1979). Othering is both a condition for and a result of bordering. State boundaries, which are both material and symbolic, can be used to create the us and the Other (Newman and Paasi Citation1998). More recently, in the framework of the “global war on terror,” the image of the enemy other has been used to legitimize tougher security and border policies: the framing of terrorism as a global problem linked to allegedly threatening groups such as Muslims has allowed states to militarize and close their borders (Jones Citation2009).

Drawing on this overview on border literature, one could argue that the Hungarian-Serbian border is in some respects a typical example of the newly fortified borders. It fits the definition provided by Hassner and Wittenberg, being a physical barrier that was unilaterally erected by Hungary for the purposes of border control. It is likewise linked to migration control and is being used to create a negative image of the Other, as discussed in greater detail in the following sections. Lastly, it is consistent with the concept of teichopolitics, being an unequal border: the gap in GDP between Serbia and Hungary is significant (Rosière and Jones Citation2012; The World Bank Citation2019), their border marks the end of the European Union, and the fence is connected with immigration control.

On the other hand, this literature review shows that comparative quantitative studies on re-bordering often focus on the relationship between two neighboring states, and assume that fortified borders necessarily indicate conflict between neighbors. The analysis of economic disparities suggests a precise divide between the poor and the rich that manifests itself at “economic or social discontinuity lines” (Rosière and Jones Citation2012, 217). These divide clearly distinguishable spaces: the wealthy and the poor, the “barrier builder” and the “barrier target” (Hassner and Wittenberg Citation2015, 158). In this regard, the Hungarian-Serbian case is much more complex, as this article will show. This case study aims to shed light on one of the “discontinuity lines” and to better understand the relation between “barrier builder” and “barrier target.” If we assume that “the new nation-state walls […] divide richer from poorer parts of the globe” (Brown Citation2017, 36), how is this division managed and negotiated on both sides of the line? More precisely, this article aims to contribute to the re-bordering debate by showing the complexity of a bordering process, therefore adding domestic factors and international linkages to the often-stressed economic and security dimensions.

Research on border regimes, especially in the European context, emphasizes the complexity of border and migration control as well as the international context and the cooperation with neighboring states (Heimeshoff et al. Citation2014; Hess and Kasparek Citation2019). Moreover, the agency and the strategies of migrants are highlighted: state border and migration policy always needs to be understood as a reaction to migratory movements (Hess Citation2016, Citation2017; De Genova Citation2017). In this context, the European border and migration regime is described as “an unstable ensemble, characterized by the heterogeneity of its actors, institutions and discourses, its shifting alliances and allegiances” (Hess and Kasparek Citation2019, 2). The present analysis aims to contribute to this debate by describing the complex process of bordering, and by examining the strategies of the participating states. While the cooperation and third-country policy of the EU has already been analyzed thoroughly (Janicki and Böwing Citation2010; Hess et al. Citation2014; Dünnwald Citation2015; Mrozek Citation2017; Schwarz Citation2017; Soykan Citation2017), the reactions and the positioning of a country behind the border fortification merit more research. Therefore, the following analysis of state policies and strategies on both sides of a recently fortified border can help us to better understand border regimes as a whole. Overall, border literature discusses various aspects of bordering, economic disparities, migration, populism, and so on, but often focuses on only one of these aspects. It may therefore enrich the debate to discuss internal and external factors, international entanglement, and state practices on both sides of a border fence as being part of the same bordering process.

3. Data and Methods

This case study is based on field research in Hungary (Budapest and the border town of Szeged) and in Serbia (Belgrade). The data include 13 problem-centered interviews, which are complemented by several informal conversations and a document analysis of policy papers and press articles. The interview topics included the reasons for building the fence, the effects of the border fortification on migration, the Hungarian and Serbian migration and border policies, the relationship and cooperation between the two countries, and the situation of migrantsFootnote1 in both countries before and after building the fence. Some additional topics came up during the interviews and were included in the analysis, for example the importance of legal changes for the effectiveness of border control or the impact of the border closure and the accompanying policies on Hungarian (civil) society.

The qualitative semi-structured interviews were fully transcribed and then coded in MAXQDA. The coding method was mostly deductive, but was completed with inductive codes during the process. The interpretation followed the qualitative content analysis method (Mayring Citation2002; Gläser and Laudel Citation2010). The codes were used to structure the data and their creation was based on the research questions and the interview topics. The analysis was developed by comparing the coding of the different interviews. In addition, field notes and theoretical memos were used to develop the essential points of the analysis.

The focus of the interviews was on the actions and strategies of both governments regarding the border fence. However, in Hungary, it proved very difficult to reach and interview state actors. Staff from The Ministry of Interior, the Border Police, and the Immigration and Asylum Office were not available for interviews, and we were referred to the University of Public Service – which trains the border police – as well as to the Migration Research Institute, which is close to the governing Fidesz party. Moreover, some of the interviewees in Hungary were very reluctant to be quoted using the name of their organization; one stated off the record that he/she did not want to risk damaging their relationship with the Hungarian government. By contrast, in Serbia, the Ministry of Interior and the Commissariat for Refugees agreed for interviews to take place and none of the interviewees considered it a problem if the organization's name was published. Understanding the difficulties in field access as a part of the research provides an insight into the social and political climate in Hungary. Altogether, the broad spectrum of interview partners, including state actors, civil society organizations, and international institutions, allowed an in-depth, multi-perspective analysis in both countries (see ). By asking both governmental and non-governmental actors about the governments’ actions and strategies, we were able to collect very different perspectives on these aspects.

Table 1. Actors Interviewed in Hungary and Serbia.

In addition to the interviews, we used press releases, official statements, and other documents concerning migration and the border fence in order to analyze the governments’ official positions.

4. The “Summer of Migration”: Migratory Movements to Europe and the Reactions of Hungary and Serbia

Immigration is not a new phenomenon in Europe, but the events of 2015 were remarkable, as indicated by the labeling of that year's summer as “the summer of migration.” The number of migrants increased significantly, first of all because of the migratory movements from war-torn Syria, but also due to high numbers of people from Afghanistan and Iraq claiming refugee status in Europe. Out of one million registered arrivals in Europe in 2015, some 50 percent were Syrian citizens, 20 percent Afghans, and 7 percent Iraqis (IOM Citation2015, 3). The most substantial movement towards Europe started in Syria; the migrants then crossed Turkey and the Balkans in order to reach the EU. Hungary occupied a strategic position on the Balkan route, being geographically positioned at the heart of the migration route and being embedded in the European Union as well as in the Schengen space (Kallius Citation2016).

The summer of migration naturally affected Hungary, as hundreds of thousands of people crossed the country. During the course of 2015, some 411,515 migrants and asylum seekers were registered in Hungary (IOM Citation2015, 14). The number of asylum applications submitted in Hungary increased to almost 180,000, but the majority of asylum seekers did not stay there: at the end of 2015, only 900–1000 of them were still in the country (Juhász, Hunyadi, and Zgut Citation2015, 10; Eurostat Citation2019). This was the context in which Hungary started constructing a fence at its border with Serbia in 2015.

While the fence was the most visible action taken by the Hungarian authorities, it was certainly not the only one. When starting to fortify its border with Serbia, the Hungarian government made sure to provide information about whom the fence was intended to keep out. Using different media and information channels, it cited mass migration as the reason for building the fence and depicted the migrants themselves as dangerous, criminal, culturally different, and threatening (Kallius Citation2017a, 141). Prime Minister Victor Orbán clearly distinguished between on the one hand, the positive image of Hungarian emigrants living in other European countries and Hungarian minorities in the neighboring countries, and on the other hand, the negative image of the Other: that is, non-European migrants (Lamour and Varga Citation2017). Starting in 2015, a massive so-called “information campaign” spread the message that Hungary was under threat from immigrants and needed the fence in order to defend itself. Government-financed billboards disseminated anti-immigration slogans all over the country. They accompanied a so-called “national consultation on immigration and terrorism” that consisted of sending a questionnaire to every adult citizen in Hungary. The questionnaire itself asked mostly biased questions, such as “Did you know that economic migrants cross the Hungarian border illegally, and that recently the number of immigrants in Hungary has increased twentyfold?” (The complete questionnaire is available online at: http://www.kormany.hu/en/prime-minister-s-office/news/national-consultation-on-immigration-to-begin). After the fence had been completed, Victor Orbán once again used harsh words to evoke a threat that necessitated maintaining it:

Hungary is encircled, and if things continue like this, we will be scalped by tens of thousands […] who want to make off with Hungarians’ money. (Hungarian Government Citation2017)

Table 2. Overview of Some of the Changes in Hungarian Immigration Law 2015–2018.

While Hungary is already a member of the EU and shapes its migration policy against this background, Serbia is an EU candidate country, currently undergoing the process of EU accession. Serbian migration and border policy thus has to be analyzed in this context. Serbia implemented an independent asylum system and asylum law relatively recently, in 2008. This took place simultaneously with the liberalization of visas for Serbian citizens, who from that point on had easier access to EU countries. Both processes are linked, as Serbia had to adopt a specific border and migration policy as a prerequisite with regard to visa liberalization for its citizens (Stojic-Mitrovic Citation2014). Under the 2008 Asylum Law, any person that arrived in Serbia and stated the intention to ask for asylum had to be provided with a so-called “72-hours paper.” This permitted a legal stay in Serbia for 72 hours; within this timeframe, the person had to register in one of the asylum centers, otherwise his/her stay became illegal (Beznec, Speer, and Stojić Mitrović Citation2016, 36). The number of people indicating the intention to ask for asylum augmented steadily and rapidly from 77 in 2008 to 16,490 in 2016; the number of people actually transiting Serbia was probably much higher (ibid., 36–37). Many of those who stated the intention to seek asylum did so in order to legalize their stay and to have access to accommodation and other services, but not necessarily with the intention to stay for long. Yet even those who intended to seek protection by requesting asylum in Serbia were unable to obtain it, as a result of the “highly dysfunctional system” (ibid., 37).

In contrast to the harsh Hungarian rhetoric, Serbia underlined the humanitarian approach of its migration policy. The Serbian president, Aleksandar Vučić, explicitly welcomed migrants in 2015 and the Serbian government provided the infrastructure to facilitate migrants’ transit through the country. In 2015, many migrants who were transiting Serbia considered the country as a better place compared with other countries such as Bulgaria (Beznec, Speer, and Stojić Mitrović Citation2016, 49). The Serbian government stated in November 2015: “Government solves problem of large waves of migrants humanely” (minrzs.gov.rs. Citation2015). When Hungary started building the fence, Vučić reacted “surprised and shocked,” stating that “Building walls is not the solution. […] Serbia will not build walls. It will not isolate itself” (Aljazeera Citation2015). However, even though Serbia criticized the Hungarian fence in order to underline its own different approach, both governments also emphasized their strong cooperation. They underlined their common role as “transit countries” and the importance of good bilateral relations, while at the same time stressing that Hungary actively supported Serbia's European integration (Government of Serbia Citation2015a, Citation2015b). Starting from 2016, the Serbian rhetoric became more securitarian. The official discourse shifted from protecting human rights to protecting borders. This took place as a reaction to the Hungarian border closure, and particularly the legal changes in Hungary, but it can also be understood in the frame of the Serbian negotiations with the EU (Beznec, Speer, and Stojić Mitrović Citation2016). At the same time, Serbia modified its asylum law, which entered into force in 2018. These changes, along with other more restrictive practices, made it even more difficult for asylum seekers to stay in Serbia, as is discussed in more detail below.

The following paragraphs present and discuss the empirical results. Section 5 shows the exploitation of the border fence by the Hungarian government. Section 6 then analyses the reaction to the fence by the Serbian government. While the usefulness of the border fence for the Hungarian government seems quite evident, its usefulness for the Serbian government is only possible due to the international entanglement of the border, which is also analyzed throughout Section 6.

5. The Two-Sided Fence: Deterring Migration, Preserving Power

This section focusses on how the Hungarian government used the fence for its own purposes. It therefore discusses the perspectives of our interview partners on why the fence was built and how the effects of the fence served the government's interests.

One major finding from our interviews is the importance of the domestic dimension in Hungary. The fence came in a period of internal political tensions and power struggles, and is clearly linked to this situation. Several interviewees mentioned the government's campaign and rhetoric that claimed to protect (white) Christianity and European culture and values, and warned against migrants as culturally different and dangerous. Interestingly, almost all the Hungarian interviewees talked about domestic motives first as the reason for building the fence, before – or instead of – speaking about migration and border control. They mentioned the need of the governing Fidesz party to win the next parliamentary elections (which took place in 2018), the pressure from the right-wing party, Jobbik, and the fact that the single-issue campaign on migration had supplanted other pressing topics such as social problems and healthcare in Hungary. Indeed, the election campaign for the parliamentary elections in 2018 was very much focused on the topic of migration. With regard to the election, Victor Orbán warned that “if we end up with an internationalist government instead of a nationalistic one, they will dismantle the fence protecting Hungary, approve Brussels’ dictate with which they want to settle migrants in Hungary and Hungary's transformation will be under way” (Béni Citation2018). Consistent with this, the interview partners considered the fence a political success for the Fidesz party, which was re-elected in 2018.

Politically, it was very useful for them. I mean, if you look at the election results since 2015, the Hungarian government has been using this campaign very successfully to gain votes in parliament. Just recently in 2018 in the latest election, they’ve secured a two-thirds majority for the third time. And they themselves will admit that the issue of migration and stopping migration played a huge part in that. (Interview 7, International Organization for Migration, Budapest)

The fence, the accompanying “information campaign,” and the legal changes influenced the social climate in Hungary. One result was that experiences of everyday racism increased, as one interviewee observed:

All of this has obviously also translated into more and more everyday practices of racism against people identified as nonbelonging or identified as others. This, I think, is something many of the migrants and refugees in the country, including some who’ve been here for ten years, have really been noticing. I’ve had some friends telling me that after living in the same building for ten, fifteen years, for the first time they go home and there's a message on their door like “go back to your country” or whatever. It's really pervasive and sort of impacting on sociality. (Interview 8, researcher in migration studies, Budapest)

And so initially Vučić criticized, he said something funny about the fence, like, it's not quite apparent who is the animal in the zoo, so from which side you see the fence, it's like Serbia that's fenced out by Hungary, but it's Hungary that's actually, you know, closing itself into a cage. (Interview 6, Migszol, Szeged)

The above presented motives for building the fence as well as the changes in Hungary that accompanied it show that the bordering process transformed the Hungarian society, which is “fenced in” by the border fortification. This aspect of fencing in has not yet been paid much attention in border research. This analysis shows, however, that the domestic dimension needs to be taken into account as part of the complex process of bordering.

The preceding paragraphs discuss the domestic motives for building a fence, as well as its effects on the Hungarian society. However, these findings do not imply that the fence has no external motives and no effect on the outside. Apart from the symbolic function of the fence, there is a very real, physical border fortification and a real conflict between those who try to control the border and those who try to cross it. At the level of communications, the government invested a substantial amount of money and effort into pointing out those who are unwanted. On the ground, a complex system is maintained in order to exclude these unwanted people. The border fortification is the most visible part of it: It consists of two fences that are about four meters high and are fitted with barbed wire. Parts of it are electrified and reinforced with welded wire mesh and a concrete foundation, and it is also equipped with heat sensors and cameras. The border is controlled by the police, the army, and the newly created “Border Hunters.” There have been numerous reports of extreme police violence against migrants at the border (Dearden Citation2017). Yet the fence itself is not enough to stop migration:

So, I mean the fence in itself is not stopping people. The legislation that is also coming along with it, that's what's stopping people. And the push-backs and all the other measures. (Interview 3, Hungarian Helsinki Committee, Budapest)

6. Alliances across the Fence: Ensuring Good Neighborly Relations Despite a Fortified Border

While, as discussed above, the Hungarian government managed to use the building of the fence to its advantage, the Serbian authorities did not opt for fencing the border but just reacted to it. The current section therefore focuses on the meaning of the border fence for Serbia and the reactions of the Serbian government to the Hungarian fence. However, the Hungarian-Serbian relationship and Serbia's reactions and policies cannot be understood without considering the broader context of the bordering. Therefore, this section also analyses the international entanglement of the border and the effects of this embeddedness.

With respect to the question of against whom the fence was built, it is remarkable that the fence did not provoke a conflict between the governments on either side of the border. After a temporary protest against the fence by the Serbian government, both sides reverted to good relations. Victor Orbán, following a meeting with the Serbian prime minister, stated with regard to the fence: “I attempted to reassure the Honourable Prime Minister that this measure is in no way directed against Serbia, or the Serbian people” (Hungarian Government Citation2015). The Serbian minister in charge of European integration also stated in November 2015 that

good and open bilateral relations can overcome some outstanding issues and occasional problems. […] This can be best seen on the example of the migrant crisis, when the representatives of the two countries sat down and talked as good neighbors and partners. (Government of Serbia Citation2015a)

Serbia is still a transit country so they pass through here onto their final destinations, wherever they may be in Western/Northern Europe, but while they’re here, we take very good care of them and the international community praised us for our good treatment of families, especially children go to school. We, as a country, with the tremendous help of the European Union, we do everything to make their accommodation and their prolonged stay as bearable as possible. (Interview 9, Commissariat for Refugees, Belgrade)

There are 3500 people now in the centers in Serbia. […] It is a big task, but we deal with it very successfully and we get very good grades from our European partners. (Interview 12, Ministry of Interior, Belgrade)

Moreover, while Serbia is underlining its humane way of dealing with immigrants, this does not mean that they are welcome to stay. State actors emphasized that Serbia is just a transit country:

Ninety-nine percent of them do not want to stay in Serbia; we are just a transit country. They just want to go to Germany, Sweden, France, Belgium, Denmark. […] Ninety-nine percent don't want to stay in Serbia; that is the main fact. (Interview 12, Ministry of Interior, Belgrade)

And the authorities also like to see that as a transit country. You will hear that narrative over and over again, which gives them also this attitude of not really being responsible for applying the procedure properly because the people don't want to stay, so they also put themselves in a situation where they say: Well, um, if they wanted to stay we would, of course, provide all services and all the other procedures – but they don't want to. (Interview 10, International Organization for Migration, Belgrade)

Still, even if the borders are closed as I already mentioned, people managed to move. It didn't affect Serbia that much in a way that a lot of people got stuck here, no. Some of them got stuck, the people who lacked money and who didn't have enough money to pay a good smuggler, yes, they were stuck but it didn't change much and, in my opinion, it didn't affect Serbia. (Interview 13, Belgrade Center for Human Rights, Belgrade)

In addition to the above-mentioned factors, other international linkages were highlighted in our interviews. Several interview partners on the two sides of the border regarded the deal between the EU and Turkey on immigration control as a crucial factor that changed the situation at the Serbian-Hungarian border. Following the agreement coming into force, migratory movements decreased: “It's clear that it's not the Hungarian fence that has stopped the Balkan route, but more the EU-Turkey agreement” (Interview 6, Migszol, Szeged). The inadmissibility rule and the laws on safe third countries also linked the situation at the border to other places, some of them as far away as Turkey: as migrants have to prove that they could not claim asylum in any country they transited through, their chances of being granted asylum in Hungary are connected with migration policies and the general situation in other countries. At the EU level, the Dublin regulation created links between EU member states by giving them the option to send migrants back to the EU state where they were first registered. The border police department of the University of Public Service in Budapest (Interview 1) explicitly named the Dublin regulation as a justification for building the fence, saying that, on the one hand, Greece was not respecting its obligations by not registering migrants and, on the other hand, other European countries were using the Dublin regulation to send people back to Hungary. The role of the EU with regard to border control was described as very ambiguous: some EU representatives and member states criticized Hungary for building a fence, but at the same time, successful border control was expected from EU member states (for a detailed analysis of this contradictory relationship, see also Kallius Citation2016, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Closely linked to the debate on the EU external borders, the Schengen Agreement also played an important role in the discussions on border control. The Hungarian authorities referred to the agreement as a reason for closing the border:

The other thing is that the EU could not do anything with the Hungarian argument that claimed that: We are a Schengen country and we are reinforcing border control. For that, we need fences. This was a strong argument by the government because, indeed, it's a Schengen border, it's an external border, and for the Hungarian authorities and government, it was very easy to point at the Greek/Italian governments not fulfilling their obligations. And they said: if this is the price, we have to do this, and we are more European than you who criticized our government. (Interview 4, Migration Research Institute, Budapest)

Hungary claims that what we do is not more and not less than doing our duties as members of the Schengen zone, protect the external borders, which is true but if that's only doing your duty then you don't build a three and a half years long multi-billion funded campaign in doing this. (Interview 6, Migszol, Szeged)

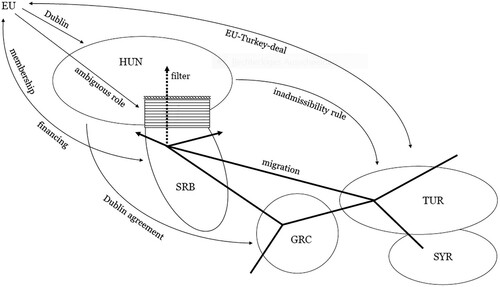

The closing of the Hungarian border was also related to other countries’ border policies: Several countries closed their borders in response to other countries closing theirs, leading to chain reactions. For example, Germany and Austria introduced border controls at their southern borders in 2015, and Hungary and Slovenia referred to these when tightening the controls at their own southern borders. Further, when Hungary closed its border with Serbia, other countries such as Macedonia also reinforced their border controls. At the same time, there was international cooperation on border control. While the Hungarian-Serbian border was controlled with the support of Frontex, Hungary sent police to Serbia and Macedonia to control their southern borders. With regard to migrants, the closure of the Hungarian-Serbian border forced them to take other routes and to cross other countries – most of our interviewees agreed that the fence did not stop migratory movements but instead diverted them. The majority of the migrants moved on to Bosnia and Herzegovina, where many of them became stuck under very difficult conditions. As a final point, the migratory movements involved crossing long distances and numerous countries before reaching Serbia or Hungary. All these factors meant that the Hungarian-Serbian border was internationally entangled in a way that went far beyond an exclusively bi-national relationship (see ).

The international entanglement of the border illustrated here has contributed to a situation where the border fence does not create a conflict between neighbors. Yet while the analysis above may show how both governments managed to exploit the border fortification to their advantage, their disparities in wealth and power should not be neglected. Although the two governments have praised each other, it is an unequal relationship: Hungary has the power to support Serbian EU accession and to propose help for controlling Serbia's southern borders (Béni Citation2018). The economic disparity between the countries and the fact that Hungary is an EU member state while Serbia is not qualifies the border as a typical “discontinuity line” (Rosière and Jones Citation2012, 217) and as one of the walls that “divide richer from poorer parts of the globe” (Brown Citation2017, 36). However, even if the fence marks a border of prosperity, the economic disparity between Hungary and Serbia is not the driving factor for the border fortification. The differences in wealth, power, and political privilege certainly made it easier to build the fence without much protest from Serbia, but it was not built against the poorer neighboring country. Serbia is not “fenced out,” but tries to use the fence to move closer to the EU. This observation ties in with the existing literature on externalization and EU migration policy, for example Stojić-Mitrović has underlined the influence of the EU integration process on migration policy in Serbia (Stojic-Mitrovic Citation2012). Serbia's reaction to Hungary's fence, as analyzed in this paper, confirms the importance of external factors for Serbia's policy and shows that even a border closure can be used to advance the process of EU accession. At the same time, Hungary's relations with some EU institutions and EU member states degenerated due to the fence building and Hungary in some ways “fenced itself out.” The situations of both Serbia and Hungary are linked to the context and the international entanglement of the fence. This case study thus illustrates that comparing neighboring countries certainly provides valuable explications for border fortification, but looking more closely at a specific case and the context of the bordering process may reveal a different picture and is thus essential to understand current trends of re-bordering.

7. Conclusion

Existing literature on re-bordering points out that most of the new border walls are not built because of territorial conflicts between nation states, as was the case in earlier times, but because of other factors, such as economic disparities, (fear of) terrorism, or securitization. The Hungarian-Serbian case shows that although these factors definitely play a role, an analysis of fortified borders should encompass more dimensions. A fortified border does not have to result from, or create, a conflict between neighboring countries. The relationship between the states on each side of a border wall can be more complex than them merely being “barrier builders” and “barrier targets,” and the real targets of the barrier may be somewhere other than just behind the fence. In the Hungarian case, the fence targets Hungarian society on the one hand, and on the other, the “global poor” (Jones Citation2016). The former has been affected by a massive government campaign on migration, the re-election of the Fidesz party, difficult relations with EU institutions, and numerous legal changes. The latter have been blocked by the physical barrier and the legislation that comes along with it, but also by its symbolic effect as a “symbol of deterrence” (Interview 12, Ministry of Interior, Belgrade), which is intended to have an impact far beyond Serbia.

The Hungarian example shows that a border fence is not always something that exists just between two nation states. It is linked to other places and other borders, such as migrants’ countries of origin, the EU, and transit countries including Turkey and Greece, and it is oriented as much towards the interior as the exterior. Research on re-bordering shows that predictions of a borderless, globalized world have not come true. Instead, the Hungarian-Serbian border can be seen as an example of a “globalized border.” Whereas the message of the fence is a nationalist one in terms of fencing the Other out and fencing the Hungarians in as a homogenous group protected by the government and the fence, the fence in itself is international: it is connected to other parts of the world and to other borders, as well as to the EU's political system. A great deal of the literature on re-bordering is still very much focused on a simple comparison between the wall builder and the neighboring state; it thus tends to neglect the relevance of domestic aspects as well as of international linkages. The current article moreover emphasizes the importance of understanding not only the intentions of the wall builder, but also of analyzing the neighbor, which is not just passive but may influence the situation with its practices and strategies.

The Hungarian-Serbian case is an example of a newly fortified border. It confirms the concept of “teichopolitics,” being a barrier constructed on a “border that is meant to differentiate between two different spaces of economic, cultural, or political privilege” (Rosière and Jones Citation2012, 220). What we can learn from this case study is that these different spaces are not always clearly separated by one line. Due to the filter function of the Hungarian-Serbian border, the fence does not penalize the neighboring country, but instead differentiates between a privileged space on one side, a less privileged space on the other side, and a non-privileged space far away. This finding may contribute to understanding how a fence can operate where the spaces of privilege are not easy to separate and where there are degrees of wealth, power, and privilege. The concept of “fencing in and fencing out” presented here furthermore helps us to understand the meaning of a border fence for the different actors on each side of the fence. Using these terms may help to sharpen the perspective on the functions of exclusion, inclusion, and control that a fortified border can perform. Moreover, it may show who can profit from a border fortification and under which circumstances. To ask who is fenced in and who is fenced out by a border fence can help to challenge the simple dichotomy between “fence builder” and “fence target.”

While the functions of borders and border fences may differ, a very common definition of a border stresses its capacity to mark a difference:

All borders either create or reflect difference, be they spatial categories or cultural affiliations and identities. All borders are initially constructed as a means through which groups – be they states, religions or social classes – can be ordered, hierarchized, managed and controlled by power elites. […] This ties in with the fact that most borders, by their very definition, create binary distinctions between the here and there, the us and them, the included and the excluded. (Newman Citation2012, 44)

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Steffen Mau and Fabian Gülzau, and two anonymous reviewers for their precious feedback on the previous drafts of this manuscript. I would also like to thank all my interviewees who took the time to respond to my questions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The word “migrant” is used here as a generic term for all people who migrate or flee from one place to another. I do not distinguish between “migrant” and “refugee.” These terms are often used to distinguish legitimate from illegitimate movements and they are, moreover, not very precise as it is difficult to tell if a person “flees” or “migrates.”

2 For an up-to-date overview of the legal changes, see the Hungarian Helsinki Committee: https://www.helsinki.hu/en/refugees_and_migrants/news/

References

- Ackleson, Jason. 2012. The Emerging Politics of Border Management: Policy and Research Considerations. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Border Studies, ed. D. Wastl-Walter, 245–61. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

- Aljazeera. 2015. Serbia Angered by Hungary’s Proposed Anti-Migrant Wall. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/06/serbia-angered-hungary-proposed-anti-migrant-wall-150618035111047.html (accessed March 25, 2020).

- Andreas, Peter. 2003. Redrawing the Line: Borders and Security in the Twenty-First Century. International Security 28, no. 2: 78–111. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/016228803322761973

- Avdan, Nazli. 2019. Visas and Walls. Border Security in the Age of Terrorism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Barth, Frederik. 1996. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries. In Ethnicity, eds. John Hutchinson, and Anthony D. Smith, 75–83. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Béni, Alexandra. 2018. Viktor Orbán: Hungary, Serbia Need to Protect Border Together. Daily News Hungary. February 9. https://dailynewshungary.com/viktor-orban-hungary-serbia-need-protect-border-together/ (accessed October 22, 2019).

- Beznec, Barbara, Marc Speer, and Marta Stojić Mitrović. 2016. Governing the Balkan Route: Maceonia, Serbia and the European Border Regime. In Research Paper Series. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Southeast Europe.

- Brown, Wendy. 2017. Walled States, Waning Sovereignty. New York: Zone Books.

- Cantat, Céline. 2016. Rethinking Mobilities: Solidarity and Migrant Struggles Beyond Narratives of Crisis. Intersections. East European Journal of Society and Politics 2, no. 4: 11–32.

- Cantat, Céline. 2017. The Hungarian Border Spectacle: Migration, Repression and Solidarity in Two Hungarian Border Cities. CPS Working Paper Series 03/2017.

- Carter, David B., and Paul Poast. 2017. Why Do States Build Walls? Political Economy, Security, and Border Stability. Journal of Conflict Resolution 61, no. 2: 239–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715596776

- Dearden, Lizzie. 2017. Hungarian Border Guards ‘Taking Selfies with Beaten Migrants’ as Crackdown Against Refugees Intensifies. In The IndependentLondon: Independent News & Media.

- De Genova, Nicholas. 2017. The Borders of “Europe”: Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Dünnwald, Stephan. 2015. Remote Control? Europäisches Migrationsmanagement in Mauretanien und Mali [European Migration Management in Mauritania and Mali], Movements. Journal für kritische Migrations- und Grenzregimeforschung 1, no. 1: 1–32.

- Dzihic, Cedran, and Cengiz Günay. 2018. Die Rückkehr der Grenzen: Globale Trends, regionale Spiegelungen [The Return of Borders: Global Trends, Regional Reflections]. In Migration und Globalisierung in Zeiten des Umbruchs, ed. F. Altenburg, 209–15. Krems: Edition Donau Universität Krems.

- Eurostat. 2019. Asylum and first time asylum applicants-annual aggregated dataEuropean Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tps00191&plugin=1 (accessed June 30, 2020).

- Gläser, Jochen, and Grit Laudel. 2010. Experteninterviews und qualitative Inhaltsanalyse [Expert Interviews and Qualitative Content Analysis]. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Government of Serbia. 2015a. Hungary Actively Supports European Integration of Serbia. https://www.srbija.gov.rs/vest/en/112751/hungary-actively-supports-european-integration-of-serbia.php (accessed March 25, 2020).

- Government of Serbia. 2015b. Police Cooperation Between Serbia, Hungary in Addressing Migrant Crisis. https://www.srbija.gov.rs/vest/en/111286/police-cooperation-between-serbia-hungary-in-addressing-migrant-crisis.php (accessed March 25, 2020).

- Hassner, Ron E., and Jason Wittenberg. 2015. Barriers to Entry. Who Builds Fortified Boundaries and Why? International Security 40, no. 1: 157–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00206.

- Heimeshoff, Lisa-Marie, Sabine Hess, Stefanie Kron, Helen Schwenken, and Miriam Trzeciak. 2014. Grenzregime II: Migration-Kontrolle-Wissen. Transnationale Perspektiven [Border Regimes II: Migration-Control-Knowledge. Transnational Perspectives.]. Berlin; Hamburg: Assoziation A.

- Hess, Sabine. 2016. Citizens on the Road: Migration, Grenze und Rekonstruktion von Citizenship in Europa [Migration, Border and Reconstruction of Citizenship in Europe.]. Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 112, no. 1: 3–18.

- Hess, Sabine. 2017. Border Crossing as Act of Resistance. The Autonomy of Migration as Theoretical Intervention into Border Studies. In Resistance. Subjects, Representations, Contexts, eds. Martin Butler, Paul Mecheril, and Lea Bernningmeyer, 87–100. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Hess, Sabine, Lisa-Marie Heimeshoff, Stefanie Kron, Helen Schwenken, and Miriam Trzeciak. 2014. Einleitung [Introduction]. In Grenzregime II: Migration-Kontrolle-Wissen. Transnationale Perspektiven, eds. Lisa-Marie Heimeshoff, Sabine Hess, Stefanie Kron, Helen Schwenken, Miriam Trzeciak, 9–40. Berlin, Hamburg: Assoziation A.

- Hess, Sabine, and Bernd Kasparek. 2019. The Post-2015 European Border Regime. New Approaches in a Shifting Field. Archivio antropologico mediterraneo 21, no. 2: 1–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.4000/aam.1812.

- Hungarian Government. 2015. Prime Minister Victor Orbán’s Press Conference after His Talks with Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic. https://www.kormany.hu/en/the-prime-minister/the-prime-minister-s-speeches/prime-minister-viktor-orban-s-press-conference-after-his-talks-with-serbian-prime-minister-aleksandar-vucic (accessed March 25, 2020).

- Hungarian Government. 2017. Hungarians’ Long-Term Safety Assured. http://www.kormany.hu/en/the-prime-minister/news/hungarians-long-term-safety-assured (accessed October 22, 2019).

- IOM. 2015. Mixed Migration Flows in the Mediterranean and Beyond, Compilation of Available Data and Information, Reporting Period 2015. https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/situation_reports/file/Mixed-Flows-Mediterranean-and-Beyond-Compilation-Overview-2015.pdf (accessed October 22, 2019).

- Janicki, Jill Jana, and Thomas Böwing. 2010. Europäische Migrationskontrolle im Sahel [European Migration Control in the Sahel Region]. In Grenzregime. Diskurse, Praktiken, Insitutionen in Europa, eds. Bernd Kasparek, Sabine Hess, 127–143. Berlin: Assoziation A.

- Jellissen, Susan M., and Fred M. Gottheil. 2013. On the Utility of Security Fences along International Borders. Defense & Security Analysis 29, no. 4: 266–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14751798.2013.842707.

- Jenkins, Richard. 2004. Social Identity. London: Routledge.

- Johnson, Corey, Reece Jones, Anssi Paasi, Louise Amoore, Alison Mountz, Mark Salter, and Chris Rumford. 2011. Interventions on Rethinking ‘the Border’ in Border Studies. Political Geography 30: 61–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.01.002

- Jones, Reece. 2009. Geopolitical Boundary Narratives, the Global War on Terror and Border Fencing in India. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 34: 290–304. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00350.x

- Jones, Reece. 2012. Why Build a Border Wall? Nacla Report on the Americas 45, no. 3: 70–2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2012.11722072

- Jones, Reece. 2016. Violent Borders. Refugees and the Right to Move. London: Verso.

- Juhász, Attila, Bulcsú Hunyadi, and Edit Zgut. 2015. Focus on Hungary. Refugees, Asylum, Migration. Prague: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, Political capital Kft.

- Kallius, Annastiina. 2016. Rupture and Continuity: Positioning Hungarian Border Policy in the European Union. Intersections 2, no. 4: 134–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.17356/ieejsp.v2i4.282.

- Kallius, Annastiina. 2017a. The East-South Axis: Legitimizing the “Hungarian Solution to Migration”. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 33, no. 2&3: 133–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.4000/remi.8761

- Kallius, Annastiina. 2017b. The Speaking Fence. Anthropology Now 9, no. 3: 16–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19428200.2017.1390909.

- Kallius, Annastiina, Daniel Monterescu, and Prem Kumar Rajaram. 2016. Immobilizing Mobility: Border Ethnography, Illiberal Democracy, and the Politics of the “Refugee Crisis” in Hungary. American Ethnologist 43, no. 1: 25–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12260.

- Lamour, Christian, and Renáta Varga. 2017. The Border as a Resource in Right-Wing Populist Discourse: Viktor Orbán and the Diasporas in a Multi-Scalar Europe. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2017.1402200.

- Mau, Steffen, Fabian Gülzau, Lena Laube, and Natascha Zaun. 2015. The Global Mobility Divide: How Visa Policies Have Evolved over Time. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41, no. 8: 1192–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2015.1005007.

- Mau, Steffen, Sonja Wrobel, Jan Hendrik Kamlage, and Till Kathmann. 2006. Territoriality, Border Controls and the Mobility of Persons in a Globalised World. Comparativ. Zeitschrift für Globalgeschichte und vergleichende Gesellschaftsforschung 17, no. 4: 16–36.

- Mayring, Philipp. 2002. Einführung in die qualitative Sozialforschung [Introduction to Qualitative Social Research]. Weinheim und Basel: Beltz Verlag.

- minrzs.gov.rs. 2015. Government Solves Problem of Large Waves of Migrants Humanely. Belgrade: The Government of the Republic of Serbia. https://www.srbija.gov.rs/vest/en/112746/government-solves-problem-of-large-waves-of-migrants-humanely.php.

- Moré, Iñigo. 2011. The Borders of Inequality. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

- Mrozek, Anna. 2017. Joint Border Surveillance at the External Borders of ‘Fortress Europe’ – Taking a Step ‘Further’ with the European Border and Coastal Guard. In Der lange Sommer der Migration. Grenzregime III, eds. Sabine Hess, Bernd Kasparek, Stefanie Kron, Mathias Rodatz, Maria Schwertl, Simon Sontowski, 84–96. Berlin: Assoziation A.

- Newman, David. 2006a. Borders and Bordering. Toward an Interdisciplinary Dialogue. European Journal of Social Theory 9, no. 2: 171–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431006063331

- Newman, David. 2006b. The Lines that Continue to Separate Us: Borders in Our ‘Borderless’ World. Progress in Human Geography 30, no. 2: 143–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132506ph599xx

- Newman, David. 2012. Contemporary Research Agendas in Border Studies: An Overview. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Border Studies, ed. D. Wastl-Walter, 33–47. Routledge: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

- Newman, David, and Anssi Paasi. 1998. Fences and Neighbours in the Postmodern World: Boundary Narratives in Political Geography. Progress in Human Geography 22, no. 2: 186–2007. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/030913298666039113

- Ohmae, Kenichi. 1990. The Borderless World. New York: Harper Collins.

- Paasi, Anssi, and Eeva-Kaisa Prokkola. 2008. Territorial Dynamics, Cross-Border Work and Everyday Life in the Finnish-Swedish Border Area. Space and Polity 12, no. 8: 13–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562570801969366.

- Pallister-Wilkins, Polly. 2015. Bridging the Divide: Middle Eastern Walls and Fences and the Spatial Governance of Problem Populations. Geopolitics 20, no. 2: 438–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2015.1005287.

- Pap, Norbert, and Péter Reményi. 2017. Re-bordering of the Hungarian South: Geopolitics of the Hungarian Border Fence. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 66, no. 3: 235–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.15201/hungeobull.66.3.4

- Rajaram, Prem Kumar. 2015a. Beyond Crisis: Rethinking the Population Movements at Europe’s Border. In FocaalBlog.

- Rajaram, Prem Kumar. 2015b. Common Marginalizations: Neoliberalism, Undocumented Migrants and Other Surplus Populations. Migration, Mobility, & Displacement 1, no. 1: 67–80. doi: https://doi.org/10.18357/mmd11201513288

- Rodriguez, Nestor. 2006. Die Soziale Konstruktion Der US-mexikanischen Grenze [The Social Construction of the US-Mexican Border]. In Grenzsoziologie, eds. Georg Vobruba, Monika Eigmüller, 89–111. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Rosière, Stéphane, and Reece Jones. 2012. Teichopolitics: Re-considering Globalisation Through the Role of Walls and Fences. Geopolitics 17, no. 1: 217–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2011.574653

- Said, Edward. 1979. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

- Schwarz, Nina Violetta. 2017. Kämpfe um Bewegung in Marokko: Grenzmanagement und Widerstand [Fights for Movement in Morocco: Border Management and Resistance]. In Der lange Sommer der Migration. Grenzregime III, eds. Sabine Hess, Bernd Kasparek, Stefanie Kron, Mathias Rodatz, Maria Schwertl, Simon Sontowski, 61–71. Berlin: Assoziation A.

- Sicurella, Federico Giulio. 2018. The Language of Walls Along the Balkan Route. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16, no. 1-2: 57–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1309088

- Soykan, Cavidan. 2017. Turkey as Europe’s Gatekeeper – Recent Developements in the Field of Migration and Asylumand the EU-Turkey Deal of 2016. In Der lange Sommer der Migration. Grenzregime III, eds. Sabine Hess, Bernd Kasparek, Stefanie Kron, Mathias Rodatz, Maria Schwertl, Simon Sontowski, 52–60. Berlin: Assoziation A.

- Speer, Marc. 2017. Die Geschichte des formalisierten Korridors. Erosion und Restrukturierung des europäischen Grenzregimes auf dem Balkan. [The History of the Formalized Corridor. Erosion and Restructuring of the European Border Regime in the Balkans.] München: bordermonitoring.eu. e.V.

- Stojic-Mitrovic, Marta. 2012. Externalization of European Borders and the Emergence of Improvized Migrants’ Settlements in Serbia. Zbornik Matice srpske za drustvene nauke 139: 237–48. doi: https://doi.org/10.2298/ZMSDN1239237S

- Stojic-Mitrovic, Marta. 2014. Serbian Migration Policy Concerning Irregular Migration and Asylum in the Context of the EU Integration Process. Issues in Ethnology and Anthropology 9, no. 4: 1105–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.21301/eap.v9i4.15.

- tagesschau.de. 2015. Tränengas, Minengefahr, neue Zäune. Flüchtlinge auf der Balkanroute. [Tear Gas, Danger of Mines, New Fences. Refugees on the Balkan Route.] https://www.tagesschau.de/newsticker/ungarn-fluechtlinge-163.html (accessed August 7, 2018).

- Vallet, Élisabeth, and Charles-Philippe David. 2012. Introduction: The (Re)building of the Wall in International Relations. Journal of Borderland Studies 27, no. 2: 111–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2012.687211

- Vallet, Élisabeth, and Charles-Philippe David. 2014. Walls of Money: Securitization of Border Discourse and Militarization of Markets. In Borders, Fences and Walls: State of Insecurity?, ed. Élisabeth Vallet, 155–168. London: Routledge.

- The World Bank. 2019. GDP (current US$). The World Bank Group. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD (accessed August 14, 2019).