ABSTRACT

This article investigates the reintroduction of temporary border controls in the Schengen Area. The Schengen Borders Code (SBC, Article 25 et seq.) allows signatory states to reinstate temporary border controls in specific circumstances that constitute a serious threat to public policy or internal security either due to foreseeable events (Art. 27), situations that require immediate action (Art. 28) or exceptional circumstances caused by deficiencies at the external border (Art. 29). In response to successive “polycrises”, signatory states have made ample use of this previously rarely-used policy instrument. This article explores the reasons for temporary border controls, their extent and duration, in order to address when, where and why member states reintroduce them. The novel data is based on notifications that Schengen members use to inform the EU Commission about their intent to reintroduce temporary controls at their land borders (1999–2020). The analysis finds that member states expanded the use of temporary border controls in terms of number and duration, as the intended purpose of temporary border controls shifted from the protection of specific events to immigration control.

Introduction

The Schengen Area is a significant cornerstone of European integration. It not only creates economic benefits (Felbermayr, Gröschl, and Steinwachs Citation2018), but is also one of the most celebrated and visible achievements of the EU; one that is valued by the majority of citizens (European Union Citation2018, 39; Karstens Citation2020). With a population of nearly 426 million, it also constitutes the largest “borderless area” in the world. In short, the Schengen Area has considerable economic, social and symbolic significance (Böhmer et al. Citation2016).

The Schengen Borders Code (SBC) regulates the functioning of the “borderless area”. Member states have abolished internal border controls and relocated border enforcement to the external border and other ports of entry (e.g. airports). The debordering process is one of the main achievements of EU regional integration, although it has also stirred up anxieties among the population which revolve around transnational crime and irregular migration, but also loss of identity (Anderson Citation2000, 19–20). Today, the allure of tight borders is not only exploited in populist rhetoric, but also reflected in “Europe’s recent and continuing flurry of wall building” (Brown Citation2017, 16). Furthermore, even EU institutions — which have traditionally been seen as defenders of free movement — have expressed more criticism regarding open borders (Roos and Westerveen Citation2020).

Security measures at external borders have long been a highly contested issue. On the one hand, EU agencies such as Frontex portray irregular migrants as victims of criminal smuggling networks and advocate interdictions at sea. On the other hand, humanitarian organizations maintain that rising border deaths are a direct result of “Fortress Europe’s” deterrence strategies (Steinhilper and Gruijters Citation2018). The reinforcements at the external border are meant to protect the internal freedom of movement. However, in light of recurrent crises, several member states have reinstated internal border controls to compensate for perceived risks evoked by unwanted immigration, terrorism and the spread of the coronavirus (Karamanidou and Kasparek Citation2020; Wolff, Servant, and Piquet Citation2020). The current article investigates how member states use temporary controls at intra-Schengen borders by mapping their geographical and temporal application.

Internal border controls have been abolished within the Schengen Area, but states have retained the right to reinstate temporary border controls in case of serious threats to public policy or internal security.Footnote1 For a long time, such internal border controls were only reintroduced for specific events such as political meetings or sports events, and only for a few days (Groenendijk Citation2004; van der Woude and van Berlo Citation2015). Consultation and reporting requirements were largely alleviated, which meant that Schengen members gave each other considerable leeway in introducing temporary border controls (Groenendijk Citation2004, 169). In other words, temporary border controls were seen as a flexible short-term solution to fairly circumscribed issues.

It was only during the migration and asylum crisis of 2015–16 that Schengen members began to expand their use of temporary border controls (Karamanidou and Kasparek Citation2020). At the height of the crisis, reports of humiliating reception conditions in Hungary drove the German government to suspend the Dublin regulations, by accepting Syrian refugees irrespective of the “first-country-of-entry” principle (Dublin Regulation) (Niemann and Zaun Citation2018, 4). However, the growing number of arrivals in Bavaria led Germany to reinstate border controls at its land border with Austria after this short-lived “open-door” policy. Other Schengen members such as Slovenia, Hungary and Sweden kept pace and also introduced internal border controls (Menéndez Citation2016, 400). By the end of 2015, seven Schengen members had reintroduced border checks as a response to the influx of refugees., Footnote2 Subsequent attempts to “bring Schengen […] back to normality” (European Commission Citation2016, 2) have remained unsuccessful, as the measures were prolonged beyond their maximum duration “by shifting from one legal basis to another” (De Somer Citation2020, 180).

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a global increase in travel bans (Piccoli, Perret, and Dzankic Citation2020). Schengen member states have followed suit by introducing travel restrictions and temporary border controls (Montaldo Citation2020, 526). The dynamics of the pandemic have made it difficult to predict a return to “normality” and observers have warned that the “coronavirus nightmare could be the end for Europe’s borderless dream” (Stevis-Gridneff Citation2020). In fact, the sheer number of mobility restrictions that have been implemented during the pandemic is unprecedented (Carrera and Luk Citation2020; Wolff, Servant, and Piquet Citation2020). Furthermore, the tentative efforts to lift the temporary border controls have been characterized as “highly uncoordinated” (De Somer, Tekin, and Meissner Citation2020, 12).

In general, the reintroduction of temporary border controls can be viewed as a pressure release valve that signals a malfunction of the Schengen Area. The idea is that states can use “instant bordering” to transform their boundaries in case of emergencies. Recently, scholars have warned that the continuing and growing use of this “hot fix” has transformed temporary border controls into “an ordinary mechanism de facto re-shaping the Schengen system” (Montaldo Citation2020, 528). Instead of a “return to normality”, continued “temporary” border controls might turn into a “new normal” (De Somer Citation2020, 181) for the Schengen Area. Other scholars, however, have underlined that reinstated controls are an appropriate crisis response backed by the Schengen regulations (Votoupalová Citation2019). From the perspective of these scholars, the pessimistic voices are exaggerated, as “open borders are here to stay” (Guild et al. Citation2015, 1). Given such vastly differing evaluations, it is surprising that only a handful of studies have used longitudinal data to analyse when, where and why member states have reinstated border controls (for exceptions, see Groenendijk Citation2004; van der Woude and van Berlo Citation2015; Carrera and Luk Citation2020; Heinikoski Citation2020).

According to the SBC, member states have to notify the European Commission (EC) when they plan to conduct border checks at an internal border. The SBC also requires member states to report the duration, scope and reason for the reintroduction of temporary border controls. These notifications have been publicly available since 2006. Using the notifications, together with additional documents provided by the Transparency Service of the General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union, the article examines the entire history of temporary border controls at internal land borders since the inclusion of the Schengen regulations into EU community law (May 1999 to December 2020). In sum, the scope of the article covers a twenty-year period, in which the Schengen Area grew from a club of nine to twenty-six member states. The following paragraphs provide an overview of the SBC, with a particular emphasis on temporary border controls. Studies that investigate the use of border controls at the intra-Schengen borders are also reviewed. Subsequently, the novel dyadic dataset on temporary land border controls is introduced, followed by an analysis of the use of temporary border controls by member states. The article concludes with remarks on the shifting use of a formerly neglected policy instrument. In addition, future paths for research as well as limitations of the study at hand are discussed.

Internal Border Controls in the Schengen Area

The Schengen Area evolved from a “coordinated solo effort” (Gehring Citation1998, translated) by France and Germany. In the Saarbrücken accord of 1984, the two countries experimented with the abolishment of border controls outside of the institutional framework of the European Community in order to avoid powerful veto players (i.e. Denmark, the United Kingdom, Greece and Ireland). In the subsequent year, the bilateral initiative grew into the multilateral Schengen Agreement when it was joined by the Benelux states. With the further joining of Portugal and Spain, the Convention Implementing the Schengen Agreement (CISA) was concluded on 19 June 1990. Accordingly, the Schengen Area developed “as a kind of laboratory of the European integration process” (De Bruycker Citation2017, 300).

In the CISA, the contracting parties set out to “to abolish checks at their common borders on the movement of persons” (European Communities Citation2000, 19). The agreement already entailed several flanking measures, such as a harmonized visa policy, common asylum procedures, police cooperation and regulations concerning the external borders that were deemed necessary for the abolishment of internal border controls (Cornelisse Citation2014, 746). The regulations on asylum procedures were replaced by the Dublin Convention, which was also concluded in 1990.Footnote3 Since the Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997, the Schengen acquisFootnote4 has been part of EU community law and new member states are obligated to adopt the regulations.Footnote5

The Schengen member states, however, kept a firm grip on issues of border controls and national security, which touch upon the very core of national sovereignty (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs Citation2018). The hesitancy to share sovereignty rights explains the fact that the shared external borders are national ones once it comes to the exercise of control (Pascouau Citation2016). Although agencies such as Frontex and the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) were established to coordinate and support Schengen members, border controls stayed with national governments.Footnote6

The option to reinstate temporary border controls in case of threats to public policy or national security had already been provided in the original Schengen Agreement. However, the regulations concerning the duration and additional notification requirements were subsequently amended. For instance, temporary border controls in the case of “exceptional circumstances” due to deficiencies at the external border were only included in 2013 (Cornelisse Citation2014, 758–760). Based on a proposal by the EC, the council can now recommend that member states reintroduce temporary border controls.

The current regulations on the reintroduction of temporary border controls are codified in the SBC of 2006. It adapted the Schengen acquis to the legal landscape after its “communitarization” into EU law. Since then, the SBC has been revised several times (Moreno-Lax Citation2017). summarizes the rules on the reintroduction of temporary border controls in the current version, introduced in 2016.

Table 1. SBC rules on the reintroduction of temporary border controls.

From its beginning, the Schengen Area has had an economic disposition, and flanking measures were seen as a necessary evil needed to safeguard the functioning of the internal market (Cornelisse Citation2014, 745–748; The Economist Citation2018, 48).Footnote7 The compensating measures were meant to offset potential security deficits created by the abolition of internal border controls (Anderson Citation2000, 21). Accordingly, temporary border controls were mainly used on a short-term basis and in fairly circumscribed situations (e.g. political meetings) (Groenendijk Citation2004).

With rising immigration, however, these measures developed an “independent raison d’etre” (Cornelisse Citation2014, 748), as they became increasingly applied to restrict unwanted immigration. A case in point are the controls that France reinstated at its land border with Italy in 2011 (Zaiotti Citation2013; Paoletti Citation2014). In the wake of the “Arab Spring”, the number of refugees arriving into Italy by sea increased considerably (Paoletti Citation2014, 133–134). Among several measures, Italy also issued temporary residence permits for Tunisian refugees, making them eligible for free movement within the Schengen Area (Paoletti Citation2014, 139). In response, France strengthened its border controls, although without complying with the consultation and reporting requirements specified in the SBC (Carrera et al. Citation2011). The dispute was not confined to Italy and France, as additional states including Austria, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium also questioned the Italian response and threatened to reintroduce border controls (van der Woude and van Berlo Citation2015, 66).

The Franco-Italian dispute highlights three important issues within the Schengen Area. First, the SBC creates structural inequalities. While all the member states benefit from the creation of a “borderless zone”, states with an external border have to act as gatekeepers for the entire area. Second, the gatekeepers are also more susceptible to exogenous shocks, such as a refugee crisis (Cornelisse Citation2014, 757–758). These imbalances can provoke conflictual situations where “frontline states” with an external border call for solidarity and threaten to ignore the Schengen rules, whereas destination countries try to convince the others to comply with the common rules, or ultimately reinstate temporary border checks (Biermann et al. Citation2019, 254). Third, issues that involve cross-border movements such as migration have the tendency to spread throughout the entire community, thus creating “chain reactions”.Footnote8 As expected, the migration and asylum crisis of 2015–16 triggered similar dynamics between frontline and destination countries (Biermann et al. Citation2019).

In addition to issues that are associated with migration, scholars have studied whether security concerns in the light of global terrorism have motivated member states to re-impose temporary border controls. Relevant cases include the border checks that France introduced after the terror attacks in Paris (November 2015) and Nice (July 2016). Since 2015, France has prolonged the measures each consecutive year by referring to continuing terrorist threats. In addition, “crimmigration” — the fusion of criminal and immigration law — has been studied in relation to temporary border controls (van der Woude and van Berlo Citation2015). However, studies indicate that terrorism motivated only 10 per cent of the reintroduced border checks between 2000 and 2014 (van der Woude and van Berlo Citation2015, 72–74). Relatedly, scholars find that temporary border controls are an expensive and inefficient tool to combat terrorism and transnational crime (Guild et al. Citation2016).

Lastly, researchers assume that the use of temporary border controls sheds light on different “political and policing styles” (Groenendijk Citation2004, 169). For example, studies have repeatedly shown that France and Spain are more likely to reintroduce temporary border controls than other member states (Groenendijk Citation2004; van der Woude and van Berlo Citation2015). Nevertheless, it is unclear whether differences in the application of temporary border checks are due to varying security environments or different approaches to policing (Groenendijk Citation2004, 169).

In sum, temporary border controls have been introduced as temporary “makeshift solution” that provide states with the option to use “instant bordering” in case of serious deficiencies in the Schengen Area. The existing body of literature assumes that security concerns in the light of global terrorism and unwanted migration — as well as a combination of the two, termed “crimmigration”— could drive states to re-impose temporary border controls. Yet empirical studies indicate that political meetings and similar events have been the main reason for temporary border controls (Apap and Carrera Citation2004; Groenendijk Citation2004; van der Woude and van Berlo Citation2015).

Recently, studies have highlighted that member states expanded their use of temporary border controls during the migration and refugee crisis of 2015–16 and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic (Karamanidou and Kasparek Citation2020; Wolff, Servant, and Piquet Citation2020). However, these studies focus on a particular point in time. Accordingly, the following section introduces a novel dataset on temporary border controls that spans the period from May 1999 to December 2020. This dataset enables the reevaluation of the aforementioned claims, by examining when, where and why member states use temporary border controls.

Data and Methods

As already noted, member states are required to notify the EC before introducing temporary border controls. The EC provides a continuously updated list of notifications, which is publicly available (European Commission Citation2020).Footnote9 The document contains four columns, providing information about the number of reinstated controls, the name of the notifying member state, the period of reinstated controls, and the reason behind and scope of the border checks. Unfortunately, the public records only date back to October 2006. Data for the additional period from May 1999–2006 was provided by the Transparency Service of the General Council of the European Union. This dataset allows a detailed analysis of the use of temporary border controls over time, which enables scrutiny of the dynamics of internal border controls in the Schengen Area.

Each set of data had specific issues that needed to be dealt with before deriving a final dataset (e.g. inconsistent and erroneous data entries). In short, the goal was to create a dyadic dataset that contains one row for each instance of a reintroduced border control per country pair. Such dyadic designs are dominant in international relations and have been extensively used to study “actor-to-actor interaction” (Poast Citation2016, 369). A dyadic approach also has several advantages. First, it takes into account that states do not necessarily reinstate controls at all land borders simultaneously. Second, it enables the assessment of whether temporary border controls are more likely to be implemented as unilateral or bilateral measures. Both issues are connected to the notion of directionality, which has not been sufficiently considered in the study of temporary border controls.

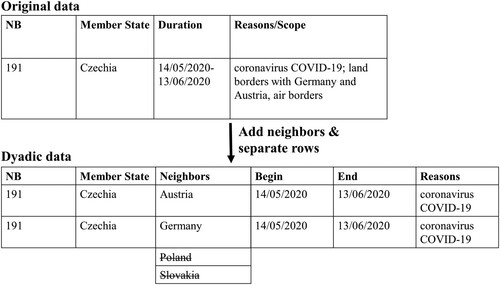

To derive such a directed dyadic dataset, the “Correlates of War” project’s Direct Contiguity Data (Stinnett et al. Citation2002) was used to create a complete dataset of contiguous (internal) land borders within the Schengen Area. This dataset was subsequently reduced to those cases where controls at a land border were reinstated. below illustrates this approach.

The analysis is restricted to land borders, because the directionality of temporary border controls at air and sea borders is difficult to assess.Footnote10 Furthermore, spot checks at land borders are arguably the most visible and controversial form of temporary controls affecting cross-border commuting and trade.

The figure shows that Czechia reintroduced temporary controls from 14 May 2020–13 June 2020 at its land borders with Germany and Austria and all air borders. In a subsequent step, the data entry is reshaped by joining all Schengen member states that share a land border with Czechia. Finally, neighboring states that are unaffected by the temporary border controls are removed again (i.e. Poland and Slovakia). The result is a directed dyadic dataset of all temporary land border controls in the Schengen Area.

The original table reports 266 cases of reintroduced temporary controls at land borders from May 1999 to December 2020. Moving from a case-wise to a dyadic data format, the datasets contain 831 instances of temporary controls at specific land borders. Even though a simple visual inspection of the table already reveals that many instances of reinstated border controls are associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and immigration (so-called “secondary movements”), their duration and scope differ considerably. In some cases, member states reintroduced border controls for only a few hours at specific border crossing points, while other member states reinstated controls at all land borders for the maximum duration permitted in the SBC.Footnote11

The reasons that member states gave to justify the reintroduction of internal border controls in the Schengen Area were classified using a dictionary approach (Grimmer and Stewart Citation2013, 274–275).Footnote12 provides information about the respective categories, which were chosen based on domain knowledge and existing research (Groenendijk Citation2004; van der Woude and van Berlo Citation2015). Both the dyadic dataset and the categories derived from the dictionary approach are available online.Footnote13

Table 2. Dictionary approach.

Analysis

In the following analysis, when, where and why member states introduce temporary border controls is examined. First, I turn to the overall use of temporary border controls by member states throughout the observation period from May 1999 to December 2020. Second, I investigate the geographic distribution of temporary border controls within the Schengen Area. Lastly, the stated reasons are scrutinized in order to shed light on the circumstances that drive states to reintroduce border controls.

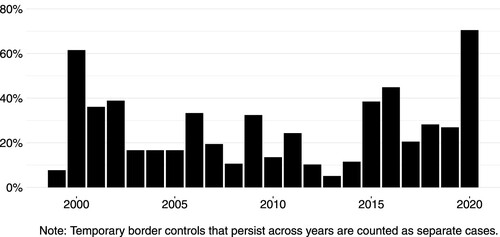

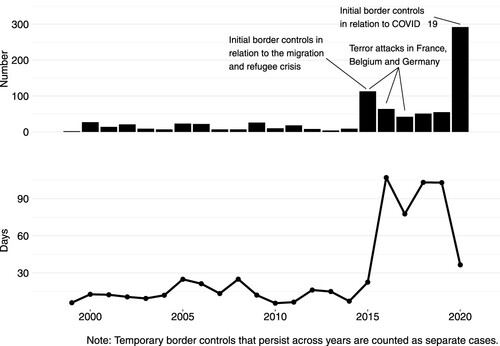

displays the number of land borders that were affected by temporary controls from May 1999 to December 2020. The lower panel also shows the mean length of these temporary border controls (in days). Lastly, major events such as the migration and refugee crisis of 2015/16, terror attacks and the COVID-19 pandemic are highlighted. It should be noted that temporary checks in place across the turn of a year are counted as separate cases.

Figure 2. Number and mean length (in days) of temporary border controls by year (in upper/lower panel).

The bar graph shows that the use of temporary border controls has increased since 2015, with a remarkable rise in 2020. Accordingly, it is apparent that the use of temporary border controls is more widespread at the beginning of crisis events affecting multiple member states, such as the migration crisis of 2015–16 and the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. However, also indicates that there has not been a single year without temporary border controls since the Treaty of Amsterdam took effect in 1999.

In the lower panel, a line graph provides information about the average length of reintroduced border controls in days. The graph shows that temporary border controls in the Schengen Area have not only been introduced more often, but that their average duration has also increased. For instance, temporary border controls between 2006 and 2010 lasted on average for 15 days. The equivalent was 19 days between 2011 and 2015, before the average length soared to 63 days — roughly two months — between 2016 and 2020. Recently, the average duration of temporary border controls decreased, but member states just used the policy instrument more often for shorter durations.

, however, does not account for the fact that a member state can re-impose controls repeatedly at the same border. Accordingly, the trend towards a greater number of temporary border controls could also be an artifact created by ongoing border disputes leading to the repeated re-introduction of temporary controls. In addition, the total number of land borders in the Schengen Area grew from 26 in 1999 to 78 in 2020 through the accession of new member states into the EU.Footnote14 Both issues are investigated in , which shows the proportion of temporary border controls out of the total number of land borders in the Schengen Area.Footnote15

indicates that temporary border controls are a widespread issue that has significance beyond specific borders. Since 2015, there has not been a single year where fewer than 20 per cent of all the Schengen land borders have been subject to temporary controls. The figure highlights that 2006, 2009 and 2011 were also years during which the use of temporary border controls was prevalent. Lastly, shows that temporary border controls affected a large number of borders at the beginning of the observation period; that is, between 2000 and 2003.

In sum, the analysis confirms that member states increasingly rely on temporary border controls to erect “instant borders”. The average duration of temporary border controls also increased, thus casting doubt on the temporary nature of these controls. Furthermore, temporary border controls are not limited to specific borders or ongoing border disputes. The measure regularly affects more than a fifth of all land borders in the Schengen Area. Finally, the figures confirm that temporary border controls are particularly used as a crisis response. Member states responded to the migration and refugee crisis of 2015/16 and the COVID-19 pandemic by reintroducing temporary border controls.

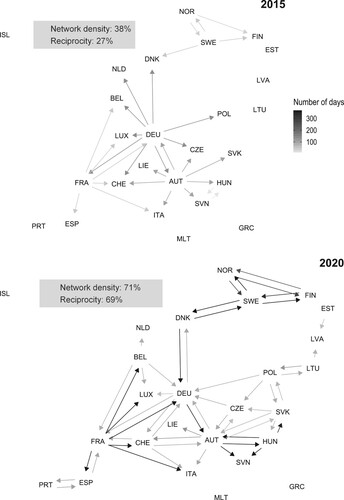

Next, I created network graphs to study the geographic distribution of temporary border controls in the Schengen Area. Even though has already shown that these controls affect multiple borders in the Schengen Area, network graphs give a more precise overview of the actual geographic distribution of temporary border checks. In this way, I intend to identify whether temporary border controls create specific fault lines in the Schengen zone.

In , member states are the nodes of the network graph that are placed according to their geographic location in Europe.Footnote16 The nodes are connected by arrows once a country re-imposes temporary controls at a border with a neighboring state. In addition, the respective arrows are shaded according to the duration of reintroduced border controls (in total days per year).Footnote17 Lastly, the density of the network and the proportion of reciprocated ties are displayed in a gray box alongside the graphs.

The graphical display is restricted to years where the network density was particularly high. Accordingly, depicts the network of temporary border controls in the crisis-ridden years of 2015 and 2020.

In 2015, nearly 40 percent of land borders in the Schengen Area were affected by temporary border controls. The majority of these controls were reinstated after the “formalized corridor” that enabled Syrian refugees to move along the Balkan route to western Europe was closed (Beznec, Speer, and Stojić Mitrović Citation2016). Accordingly, the figure captures the “domino effect” (Biermann et al. Citation2019, 254) that followed the German decision to reintroduce controls at its border with Austria. Other member states also introduced border checks in order to mitigate the risk of becoming a “dead end” for refugees (Pastore and Henry Citation2016, 54). Furthermore, the controls imposed by Austria and Germany were prolonged multiple times, ending up as three to nearly five months of border checks. Other countries that relied heavily on temporary border controls were France, Norway and Sweden. The mean total length of temporary border controls reached 85 days in 2015. Notably, the Benelux states as well as southern and eastern European countries — with the exception of Hungary and Slovenia — were predominantly the target of temporary border controls.

Turning to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis of 2020, it becomes clear that the use and duration of temporary border controls has increased considerably. Network density and reciprocity hover at around 70 per cent, indicating that a majority of intra-Schengen borders were subject to border controls. Accordingly, it is not possible to identify any clear fault lines in the Schengen Area. In fact, fifteen member states had already reinstituted temporary border controls by the end of March 2020. While these controls were, on average, introduced for a limited number of 36 days, member states continuously prolonged these measures (see ). As a result, the mean total length of temporary border controls adds up to a staggering number of 194 days per affected border dyad. Given that temporary border controls associated with “secondary movements” were still in place at the beginning of 2020, scholars underline that the COVID-19 pandemic is a continuing “stress test” (Montaldo Citation2020, 523) for the Schengen regime.

In sum, the network graphs show that the use of temporary border controls expanded during the period from 2015 to 2020. Even more striking than the expansion of temporary border checks in the Schengen Area is the fact that the total duration of controls also increased considerably. Thus, it is indeed questionable whether temporary border controls can still be described as a temporary pressure release valve, or are instead the “new normal” (De Somer Citation2020, 181).

With regard to the geographic location of internal border controls, I identify a fault line that runs between northern and western Europe, on the one side, and eastern and southern European states including Benelux, on the other. In 2015, northern and western European countries have been particularly active in implementing border checks, while eastern and southern European states have been less likely to reintroduce temporary border controls. Such a fault line disappeared in 2020 when temporary border controls affected more than two thirds of all land borders in the Schengen Area.

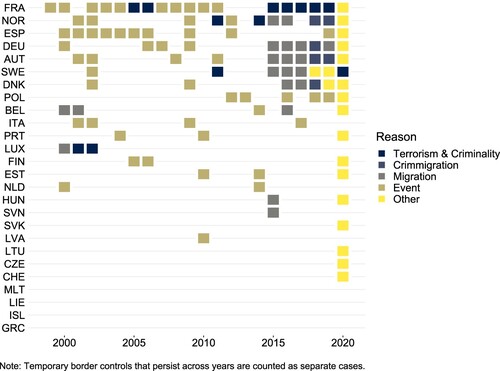

These findings are confirmed in , which provides information about the use of temporary border controls by member states over time.Footnote18 In addition, the rectangles are colored according to the main reason given for the reintroduction of border checks by the respective member state. The y-axis is ordered by the number of years a member state reintroduced temporary controls at one of its land borders.

France had been reluctant to abolish border controls from the start of the Schengen Agreement (Groenendijk Citation2004, 156–157) and still leads the list of heavy users of temporary controls (van der Woude and van Berlo Citation2015, 71). Over a period of 21 years, there were only four during which France did not impose temporary controls. Other countries that have regularly reinstated temporary border controls are Spain and Norway (11 years), Austria and Germany (10), Sweden (8), Denmark (7) and Poland (6). As already mentioned, temporary border controls have rarely been introduced by the Benelux, southern and eastern Schengen members.

Examining the reasons that states have given for the reintroduction of temporary border controls, it is clear that has been a shift in recent years. Between 1999 and 2014, member states introduced temporary border controls predominantly in order to protect specific events such as political meetings. With the onset of the migration and refugee crisis, migration — sometimes coupled with security concerns — became the primary reason for the reintroduction of temporary border controls. Lately, the COVID-19 pandemic and overlapping motives have been given as reasons.

Conclusion

The freedom to cross national borders without interference by border controls within the Schengen Area is cherished as one of the major achievements of the EU. However, successive “polycrises” have strained the common integration project, and in particular the Schengen regime. Schengen member states have repeatedly demonstrated their sovereignty by reintroducing border controls (Pascouau Citation2016). As a result, scholars have warned that the continuous reliance on temporary border controls as a pressure release valve puts the Schengen Area at risk (De Somer Citation2020; Montaldo Citation2020). Nevertheless, research has rarely traced the actual use of temporary border controls over time. The current article addresses this gap by examining when, where and why member states reintroduce temporary border controls within the “borderless” Schengen zone.

The analysis shows that the migration and refugee crisis of 2015–16 was a crucial event that led several northern and western European countries to reinstate temporary border controls in order to stem unwanted secondary movements from south-eastern Europe. Since 2015, border checks at intra-Schengen borders have continued unabated and have been stretched far beyond their initial function as temporary pressure release valves. Not only have states made ample use of temporary border controls, but the average duration has also increased considerably. From 2015 to 2020, no less than a fifth and as many as two thirds of all Schengen borders have been subject to border controls. As a result, the EU is still far from “a return to a normally functioning Schengen Area” (European Commission Citation2016, 3), let alone “future proof” migration governance (Geddes Citation2018, 124–125).

The shifting function of temporary border controls is also apparent in the notifications that member states send to inform the EC about their plans to reintroduce border checks. Between 2000 and 2014, border controls were used to safeguard circumscribed events such as political meetings, sports events, demonstrations or celebrations. In the more-recent period, however, unwanted immigration, terrorism and a mixture of these factors have become pivotal reasons for the reintroduction of temporary border controls. Lately, a combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and preexisting concerns has dominated the agenda.

The European Union is only one — albeit the most advanced — among several bodies of regional integration that have taken steps towards freedom of movement for their citizens (Gülzau et al., Citation2016). Such bodies adjust their methods of border control by shifting the locus of control from their internal to their external borders. In addition, states use procedures such as visa policies and legal constructs to detach the borders’ “migration-control function from a fixed territorial marker” (Shachar Citation2020, 4). Despite such shifts, which have blurred the territorial fixity of border control practices, the actual border line remains a pivotal vantage point for states. My analysis shows that Schengen states increasingly rely on temporary border controls to erect “instant borders” as a measure of last resort. Accordingly, scholars should continue to trace how border control practices have become “less territorial, less physical, more complex and less visible” (Hassner Citation2002, 41). However, at the same time, we should continue to monitor control practices at the territorial border line.

The article contributes to this ongoing debate by studying how states use temporary border controls in the Schengen Area. However, the study has several limitations that should be addressed in prospective research. First, temporary border controls are just one measure that member states have adopted to safeguard the “borderless” Schengen Area. The dynamics at the intra-Schengen borders also involve deeper police cooperation and police checks in border areas. Second, the analysis at hand applies a dyadic design that makes it possible to study the directionality of internal border control practices, but neglects temporary border controls that states have reintroduced at sea and air ports. Third, publicly available notifications might not disclose latent reasons behind the reintroduction of temporary border controls (e.g. domestic politics). Lastly, the empirical study of internal border controls is in need of additional research to move further beyond descriptive accounts of border control practices. For instance, researchers could move forward by conducting case studies on governments’ decision-making behind the reintroduction of temporary border controls. In light of dismantled border control infrastructure, scholars should also investigate how police forces implement border controls on the ground.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 However, article 23 of the SBC allows for police checks in border areas when they do not amount to regular border checks. Scholars have emphasized “that much of the actual implementation of these police checks has been left to the discretion of member states” (van der Woude Citation2020, 118).

2 Germany, Austria and Slovenia introduced temporary border controls in September 2015. Subsequently, Hungary (October 2015), Malta, Sweden and Norway (November 2015) also reinstated temporary border controls.

3 The Dublin Convention was meant to prevent “asylum shopping” whereby asylum-seekers would “choose the most generous system (in terms of accessibility or benefits) to submit their asylum claim” (Zaun Citation2017, 62). Policymakers assumed that an area without border controls would be particularly prone to this issue.

4 The Schengen acquis is understood as the Schengen Agreement, the Convention Implementing the Schengen Agreement, the Accession Protocols and Agreements, and the Decisions and Declarations adopted by the Executive Committee and the Central Group (Cornelisse Citation2014, 747; European Communities, Citation2000).

5 The Schengen Area, however, is characterized by previous “differentiation” (De Bruycker Citation2017, 302). In particular, the United Kingdom (even before Brexit) and Ireland did not abolish internal border controls. In addition, the non-EU states of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland are included in the Schengen Area. Lastly, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus and Romania are prospective member states. Today, the Schengen Area comprises 26 member states.

6 In response to the migration and refugee crisis of 2015-16, Frontex has been reformed and expanded to play a more active role in managing the external borders. Among others things, the reform will create a force of 10,000 EU border guards and strengthen Frontex’s role as a coordinating body (through EUROSUR). It remains to be seen, however, whether the reform will help to resolve the divergent perceptions of migration policy that exist among Schengen member states (Bossong Citation2019).

7 As a case in point, the bilateral initiative between France and Germany was preceded by protests involving commercial lorry drivers who blocked roads to the border posts to demonstrate against long delays (Groenendijk Citation2004, 153).

8 These issues also characterize the closely related Dublin regulations, which according to the first-country-of-entry principle delegate the responsibility to register asylum seekers to “frontline states” such as Italy, Greece and Malta (Trauner Citation2016).

9 It cannot be fully ruled out that further instances of temporary border controls exist (van der Woude and van Berlo Citation2015, 69–70). However, since the notifications are now centrally gathered by the EC and public interest has increased, it can be assumed that reporting discipline has grown over time.

10 Only in rare cases, member states introduce temporary border controls at air or sea borders against specific countries, although practices of local border police might target specific (third-country) nationals (Carassava Citation2017; Colombeau Citation2020).

11 In the final dataset, the duration of reintroduced border controls is counted in days, thus the smallest unit is a single day. Further, the smallest unit of observation is single land borders. Accordingly, a single spot check at a specific border crossing point is coded as affecting a contiguous border line.

12 The data provided by the Transparency Service of the General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union does not include information about the reasons given by member states for the reintroduction of temporary border controls. However, the original notifications could be retrieved from the public record of council documents.

13 The dataset is available in a GitHub repository: https://github.com/FabianFox/Schengen/blob/master/data/TemporaryBorderControls_1999-2020.csv.

14 See Appendix I for changes in the composition of the Schengen Area since 1999.

15 In network research, this measurement is also known as the density of a directed network (Wasserman and Faust Citation1994, 129).

16 The nodes are placed according to the centroids of the country polygons, which were adjusted to achieve a clearer visual representation. The figure shows all Schengen member states, although Ireland and Malta are not considered in the analysis as they do not have any land borders. The country names are abbreviated using the ISO 3166–1 alpha-3 standard.

17 In a few cases, the duration of temporary border controls at a specific border may exceed 365 days per year, as states informed the EC about overlapping controls. However, this only affected four dyads (2016: DEU-AUT; 2019: DNK-DEU; 2020: DEU-AUT, DNK-DEU and DNK-SWE).

18 Three cases, all concerning the Franco-Spanish border, had to be excluded because the original documents could not be retrieved.

References

- Anderson, Malcom. 2000. The Transformation of Border Controls: A European Precedent? In The Wall Around the West. State Borders and Immigration Controls in North America and Europe, eds. Andreas Peter, and Timothy Snyder, 15–29. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Apap, Joanna, and Sergio Carrera. 2004. Maintaining Security Within Borders: Toward a Permanent State of Emergency in the EU? Alternatives 29, no. 4: 399–416. doi:10.1177/030437540402900402.

- Beznec, Barbara, Marc Speer, and Marta Stojić Mitrović. 2016. Governing the Balkan Route: Macedonia, Serbia and the European Border Regime. Research Paper Series of Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung: Southeast Europe 5: 1–116.

- Biermann, Felix, Nina Guérin, Stefan Jagdhuber, Berthold Rittberger, and Moritz Weiss. 2019. Political (Non-)Reform in the Euro Crisis and the Refugee Crisis: A Liberal Intergovernmentalist Explanation. Journal of European Public Policy 26, no. 2: 246–266. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1408670.

- Böhmer, Michael, Jan Limbers, Ante Pivac, and Heidrun Weinelt. 2016. Departure from the Schengen Agreement. Macroeconomic Impacts on Germany and the Countries of the European Union. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Bossong, Raphael. 2019. The Expansion of Frontex. Symbolic Measures and Long-Term Changes in EU Border Management. SWP Comment 47: 1–8. doi:10.18449/2019C47.

- Brown, Wendy. 2017. Walled States, Waning Sovereignty,2nd ed). New York: Zone Books.

- Carassava, Anthee. 2017. “Greeks condemn controversial German airport checks.” Deutsche Welle, November 28. https://p.dw.com/p/2oKOU.

- Carrera, Sergio, Elspeth Guild, Massimo Merlino, and Joanna Parkin. 2011. A Race Agains Solidarity: The Schengen Regime and the Franco-Italian Affair. Brussels: CEPS Centre for European Policy Studies.

- Carrera, Sergio, and Ngo Chun Luk. 2020. In the Name of COVID-19: Schengen Internal Border Controls and Travel Restrictions in the EU Brussels: European Union.

- Colombeau, Sara Casella. 2020. Crisis of Schengen? The Effect of Two ‘Migrant Crises’ (2011 and 2015) on the Free Movement of People at an Internal Schengen Border. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46, no. 11: 2258–2274. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1596787.

- Cornelisse, Galina. 2014. What's Wrong with Schengen? Border Disputes and the Nature of Integration in the Area Without Internal Borders. Common Market Law Review 46, no. 11: 741–770. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1596787.

- De Bruycker, Philippe. 2017. The European Union: From Freedom of Movement in the Internal Market to the Abolition of Internal Borders in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice. In Migration, Free Movement and Regional Integration, eds. Sonja Nita, Antoine Pécoud, Philippe de Lombaerde, Paul de Guchteneire, Kate Neyts, and Joshua Gartland, 287–311. Paris: UNESCO.

- De Somer, Marie. 2020. Schengen: Quo Vadis? European Journal of Migration and Law 22, no. 2: 178–197. doi:10.1163/15718166-12340073.

- De Somer, Marie, Funda Tekin, and Vittoria Meissner. 2020. Schengen Under Pressure: Differentiation or Disintegration? EU IDEA Policy Paper 7: 1–22.

- The Economist. 2018. Charlemagne: Save our Schengen: Europe’s Passport-Free Zone Faces Grim Future. The Economist, June 23 427: 48. (US).

- European Commission. 2016. Back to Schengen - A Roadmap. (COM 120). Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2020. Member States’ Notifications of the Temporary Reintroduction of Border Control at Internal Borders Pursuant to Article 25 and 28 et seq. of the Schengen Borders Code. Brussels: European Commission. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/borders-and-visas/schengen/reintroduction-border-control/docs/ms_notifications_-_reintroduction_of_border_control_en.pdf.

- European Communities. 2000. The Schengen Acquis as Referred to in Article 1(2) of Council Decision 1999/435/EC of 20 May 1999. Official Journal of the European Communities 43: 1–473.

- European Union. 2018. Special Eurobarometer 474 – June-July 2018: Europeans’ Perceptions of the Schengen Area. Brussels: European Union.

- European Union. 2016. Regulation (EU) 2016/399 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2016 on a Union Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code). Official Journal of the European Union 59, no. L77: 1-52

- Felbermayr, Gabriel, Jasmin Katrin Gröschl, and Thomas Steinwachs. 2018. The Trade Effects of Border Controls: Evidence from the European Schengen Agreement. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56, no. 2: 335–351. doi:10.1111/jcms.12603.

- Geddes, Andrew. 2018. The Politics of European Union Migration Governance. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56, no. S1: 120–130. doi:10.1111/jcms.12763.

- Gehring, Thomas. 1998. Die Politik des koordinierten Alleingangs. Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen 5, no. 1: 43–78.

- Genschel, Philipp, and Markus Jachtenfuchs. 2018. From Market Integration to Core State Powers: The Eurozone Crisis, the Refugee Crisis and Integration Theory. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56, no. 1: 178–196.

- Grimmer, Justin, and Brandon M. Stewart. 2013. Text as Data: The Promise and Pitfalls of Automatic Content Analysis Methods for Political Texts. Political Analysis 21, no. 3: 267–297. doi:10.1093/pan/mps028.

- Groenendijk, Kees. 2004. Reinstatement of Controls at the Internal Borders of Europe: Why and Against Whom? European Law Journal 10, no. 2: 150–170. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0386.2004.00209.x.

- Guild, Elspeth, Evelien Brouwer, Kees Groenendijk, and Sergio Carrera. 2015. What is Happening to the Schengen Borders? CEPS Paper in Liberty and Security in Europe 86: 1–24.

- Guild, Elspeth, Sergio Carrera, Lina Vosyliūtė, Kees Groenendijk, Evelien Brouwer, Didier Bigo, Julien Jeandesboz, and Médéric Martin-Mazé. 2016. Internal Border Controls in the Schengen Area: Is Schengen Crisis-Proof? Luxembourg: Publications Office.

- Gülzau, Fabian, Steffen Mau, and Natascha Zaun. 2016. “Regional Mobility Spaces? Visa Waiver Policies and Regional Integration.” International Migration 54 (6): 164–180. doi:10.1111/imig.12286.

- Hassner, Pierre. 2002. Fixed Borders or Moving Borderlands? A New Type of Border for a New Type of Entity. Chap. 3. In Europe Unbound. Enlarging and Reshaping the Boundaries of the European Union, ed. Jan Zielonka, 38–50. London: Routledge.

- Heinikoski, Saila. 2020. COVID-19 Bends the Rules on Border Controls. FIIA Briefing Paper 281: 1–8.

- Karamanidou, Lena, and Bernd Kasparek. 2020. From Exceptional Threats to Normalized Risks: Border Controls in the Schengen Area and the Governance of Secondary Movements of Migration. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 1–21. doi:10.1080/08865655.2020.1824680.

- Karstens, Felix. 2020. Let Us Europeans Move: How Collective Identities Drive Public Support for Border Regimes Inside the EU. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 58, no. 1: 116–137. doi:10.1111/jcms.12983.

- Menéndez, Agustín José. 2016. The Refugee Crisis. Between Human Tragedy and Symptom of the Structural Crisis of European Integration. European Law Journal 22, no. 4: 388–416. doi:10.1111/eulj.12192.

- Montaldo, Stefano. 2020. The COVID-19 Emergency and the Reintroduction of Internal Border Controls in the Schengen Area: Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste. European Papers 5, no. 1: 523–531. doi:10.15166/2499-8249/353.

- Moreno-Lax, Violeta. 2017. The Schengen Borders Code: Securitized Admission Criteria as the Centrepiece of Integrated Border Management—Instilling Ambiguity. Chap. 3 In Accessing Asylum in Europe: Extraterritorial Border Controls and Refugee Rights Under EU Law, 47–80. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Niemann, Arne, and Natascha Zaun. 2018. EU Refugee Policies and Politics in Times of Crisis: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56, no. 1: 3–22. doi:10.1111/jcms.12650.

- Paoletti, Emanuela. 2014. The Arab Spring and the Italian Response to Migration in 2011. Comparative Migration Studies 2, no. 2: 127–150. doi:10.5117/CMS2014.2.PAOL.

- Pascouau, Yves. 2016. The Schengen Area in Crisis – the Temptation of Reinstalling Borders. In Schuman Report on Europe – State of the Union 2016, eds. Thierry Chopin, and Michel Foucher, 47–54. Paris: Lignes de repères.

- Pastore, Ferruccio, and Giulia Henry. 2016. Explaining the Crisis of the European Migration and Asylum Regime. The International Spectator 51, no. 1: 44–57. doi:10.1080/03932729.2016.1118609.

- Piccoli, Lorenzo, Andreas Perret, and Jelena Dzankic. 2020. “International travel restrictions in response to the coronavirus outbreak” Globalcit, Infographics. Available at The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies http://hdl.handle.net/1814/66677.

- Poast, Paul. 2016. Dyads Are Dead, Long Live Dyads! The Limits of Dyadic Designs in International Relations Research. International Studies Quarterly 60, no. 2: 369–374. doi:10.1093/isq/sqw004.

- Roos, Christof, and Laura Westerveen. 2020. The Conditionality of EU Freedom of Movement: Normative Change in the Discourse of EU Institutions. Journal of European Social Policy 30, no. 1: 63–78. doi:10.1177/0958928719855299.

- Shachar, Ayelet. 2020. The Shifting Border: Legal Cartographies of Migration and Mobility. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Steinhilper, Elias, and Rob J. Gruijters. 2018. A Contested Crisis: Policy Narratives and Empirical Evidence on Border Deaths in the Mediterranean. Sociology 52, no. 3: 515–533. doi:10.1177/0038038518759248.

- Stevis-Gridneff, Matina. 2020. “Coronavirus Nightmare Could Be the End for Europe’s Borderless Dream”. The New York Times, February 26. https://advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:5Y98-J4S1-DXY4-X2PN-00000-00&context=1516831.

- Stinnett, Douglas M., Jaroslav Tir, Paul F. Diehl, Philip Schafer, and Charles Gochman. 2002. The Correlates of War (Cow) Project Direct Contiguity Data, Version 3.0. Conflict Management and Peace Science 19, no. 2: 59–67. doi:10.1177/073889420201900203.

- Trauner, Florian. 2016. Asylum Policy: the EU’s ‘Crises’ and the Looming Policy Regime Failure. Journal of European Integration 38, no. 3: 311–325. doi:10.1080/07036337.2016.1140756.

- van der Woude, Maartje. 2020. A Patchwork of Intra-Schengen Policing: Border Games Over National Identity and National Sovereignty. Theoretical Criminology 24, no. 1: 110–131. doi:10.1177/1362480619871615.

- van der Woude, Maartje, and Patrick van Berlo. 2015. Crimmigration at the Internal Borders of Europe? Examining the Schengen Governance Package. Utrecht Law Review 11, no. 1: 61–79. doi:10.18352/ulr.312.

- Votoupalová, Markéta. 2019. The Wrong Critiques: Why Internal Border Controls Don't Mean the End of Schengen. New Perspectives 27, no. 1: 73–99. doi:10.1177/2336825X1902700104.

- Wasserman, Stanley, and Katherine Faust. 1994. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications,16th ed). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wolff, Sarah, Ariadna Ripoll Servant, and Agathe Piquet. 2020. Framing Immobility: Schengen Governance in Times of Pandemics. Journal of European Integration 42, no. 8: 1127–1144. doi:10.1080/07036337.2020.1853119.

- Zaiotti, Ruben. 2013. The Italo-French Row Over Schengen, Critical Junctures, and the Future of Europe’s Border Regime. Journal of Borderlands Studies 28, no. 3: 337–354. doi:10.1080/08865655.2013.862912.

- Zaun, Natascha. 2017. EU Asylum Policies: The Power of Strong Regulating States. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Appendix

Table A1. Changes in the composition of the Schengen Area, 1999–2020.

Table A2. Percentage of intra-Schengen land borders affected by the reintroduction of temporary border controls.