ABSTRACT

What instruments of migration control is the current Mexican administration employing? Do these differ from those of past administrations? Past administrations have applied policies to stem the entrance and stay of irregularized migrants; however, president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (2018-2024) stated that his administration would provide jobs to migrants and respect their human rights. For that, his government designed a New Migration Policy. Drawing on secondary qualitative data, policy analysis, reports, and statistical data, this paper examines five actions the ongoing Mexican administration has performed to manage irregularized migration, and evaluates if the strategies correspond with the principles of the New Migration Policy. Findings show that the Mexican government has used new and long-standing bordering practices to contain irregularized migration, contrasting with the discourse of respect to migrants’ human rights. The actions performed have gone from “permissive” to repressive as the pressure from the US and the influx of migrants increased.

Introduction

On December 1, 2018, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) took on the presidency of Mexico amid migration turmoil. The administration designed a New Migration Policy (NMP) to address relevant gaps in migration policy as it strived to transform migration management. The NMP would respect migrants’ human rights, be inclusive, and have a gender perspective. The administration stated that (irregularized) migrants had rights and would not be stigmatized, criminalized, or persecuted (Redacción Ejecentral Citation2018, para. 3).

The arrival of Central American migrants in the spring of 2019 tested the NMP. The Mexican government responded to the arrival of the first migrant caravan of the administration by granting temporary humanitarian permits, Tarjeta de Visitante por Razones HumanitariasFootnote1 (TVRH). In the following months, migrants continued to arrive in Mexico and the US, leading to increased detentions at the US- Mexico border. President Trump first responded by implementing the Migrant Protection Protocols and later threatened Mexico with import tariff increases prompting the negotiation of a deal between the governments. In June 2019, AMLO’s administration deployed more than 25,000 officers to the Southern border to contain undocumented migration (Hernández López Citation2020). Since then, a series of actions have been carried out to deter the entrance of, primarily, Central American migrants.

This paper deals with the practical implementation of migration control in Mexico’. What instruments of border control is Mexico employing? How does the Mexican state implement its New Migration Policy (NMP)? Do state actions correspond with the guidelines of the NMP? To that end, I analyze migration policies in Mexico from 1994 to 2021, along with the instruments and bordering techniques that Mexico has applied. In doing so, I explore the different “collaboration” programs between the US and Mexico to show the instrumentalization of migration management. I argue that the current administration has employed new and long-standing control and containment strategies following the pattern of governance by containment of past administrations. While granting temporary protective mechanisms offer a type of regular status in Mexico, it has proved to be a bordering practice that has increased the vulnerability of migrants. Other measures, such as the return of asylum seekers to Mexico, deployment of the national guard, and the military's involvement in migration matters, have resulted in further criminalization, persecution, and vulnerability of migrants. The government's strategies have gone from permissive to repressive. At first, it bore the entrance and stay of undocumented migrants through temporary protective mechanisms, later shifting to a more repressive approach as pressure from the US and arrivals increased. The paper contributes to the growing literature on migration management and externalization of borders by showing Mexico’s current migration control practices.

This paper is based on secondary data. I examine the narratives of the Mexican and US presidents, government officials, press releases, policies, and legislation. Along with a literature review, I analyze statistical data from the Migration Policy Unit, Registry and Identification of People (UPMRIP), the National Migration Institute (INM), the Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid (COMAR), the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS), newspaper articles, and NGOs reports.

The paper is divided into four sections. The first deals with the analytical framework: policies for migration management. The second is a background on migration policy in Mexico over the last three decades. The third explains the components of the NMP and lays out the actions that the Mexican and US governments have carried out under AMLO's administration. The fourth is a discussion of the policies implemented. The article concludes with an assessment of the performance of the Mexican state.

Analytical Framework. Policies for Migration Management

In this highly globalized era, developed nations have created the conditions to produce a population surplus through the disruption of societies, resulting in the displacement of people from usual livelihoods and creating a mobile population in search of new sources of income and employment (Massey Citation2002; Massey, Durand, and Malone Citation2002). At the same time, these countries demand low-skilled, cheap labor to take on unwanted, often, low paid jobs from low-wage countries while enacting selective policies that regulate the entrance of migrants, creating what James Hollifield called the “liberal paradox” that is, “open” markets and “closed” political societies (Álvarez Velasco Citation2016; De Genova Citation2002; Hollifield Citation2006). Developed nations promote the liberalization of the economies, commercial exchange, and the flexibilization of trade regulations, reflected in the signing of free trade agreements, but create migration policies that restrict the entrance of specific populations.

Entry restrictions are enforced on migrants from developing countries and refugees but lifted to other categories of migrants — students, investors, high-skilled workers, and tourists— creating a classification of “desired” and “undesired” migrants (Álvarez Velasco Citation2016) and new hierarchies of people (Hess Citation2017). For instance, in the 1980s, the US developed a “selectivity principle” whereby the US Congress decided who “deserved asylum and assistance” instead of applying the refugee definition based on the UN principles. Thus, the US selected the country of origin of refugees and the number of people that were to receive asylum based on the “nationality groups that served a political purpose” (Menjívar Citation2000, 79). Given the direct intervention of the US in the Salvadoran and Guatemalan Civil Wars, the US denied asylum claims to Guatemalans and Salvadorans, as providing them protection would contradict its own foreign policyFootnote2 (Menjívar and Gómez Cervantes Citation2018). They were not recognized as refugees as, in the words of US officials, “they did not fit into the program” (Frelick Citation1991, 214). Instead, representatives of the Reagan administration stated that Central Americans were economic migrants seeking a better living standard (Nepstad and Smith Citation2001; Stanley Citation1987).

Policy restrictions lead migrants to enter the countries irregularly. Elaborating on De Genova (Citation2002), Soledad Álvarez Velasco (Citation2016, 159) argues that migrant populations are irregularized, insomuch that irregularity is produced and reinforced continuously through norms, laws, policies, and practices that produce classified, racialized, and criminalized subjects. The immigration policies decrease the opportunities for the authorized entrance of “unwanted populations” into the countries, forcing people into irregularity.

The “undesired” migrants are subject to racialization, policing, and the target of draconian immigration policies that criminalize them. That is, irregularized migrants have been depicted as dangerous and “dirty” others —illegal, rapists, criminals, smugglers, poor, killers, drug dealers—subjected to racialization and policing. They are the target of ferocious policies of deterrence and enforcement and are often seen as a threat to national security (Álvarez Velasco Citation2016; De Genova Citation2002; Núñez Citation2020; Torres Citation2018; Vogt Citation2020). Consequently, states have created and enacted policies and strategies for identification, dissuasion, detention, and deportation (Faret, Anguiano Téllez, and Rodríguez-Tapia Citation2021). These policies can be observed in the increased and continuous use of technology devices, such as infrared cameras and drones at the borders; the implementation of surveillance mechanisms whereby the state deploys law and immigration enforcement agencies, particularly immigration officers, police and military personnel, and officers of the national guard to the borders; and the construction of mobile checkpoints and fences to control and limit the movement of people (Anguiano Téllez and Trejo Peña Citation2007; Torre Cantalapiedra and Yee Quintero Citation2018; Torres Citation2018; Varela Huerta Citation2015). Remarkably, after the events of 09/11 in the US, the notion of security became an essential element of migration governance, and the “perceived need for security against ‘dangerous’ populations […] enabled the proliferation of surveillance” (Núñez Citation2020, 550).

Destination, transit, and origin countries implement containment policies differently, often following a regional approach to migration. The destination countries tend to have a dissuasive policy “towards the exterior” (Faret, Anguiano Téllez, and Rodríguez-Tapia Citation2021, 65) that affects the origin and transit countries. That is, they follow a process of externalization of borders. Externalization refers to the “policies that shift the place where the control of travelers takes place from the state's border into which the individual is seeking to enter” to the transit or country of origin (Paoletti Citation2011, 273). Regularly, the externalization of borders results from power relations and asymmetries between countries. The destination country, often developed, has “more power” over the transit and origin countries, resulting in an immersion in the political agenda of such countries (Faret, Anguiano Téllez, and Rodríguez-Tapia Citation2021).

The externalization of migration can take different forms: “joint programs” or alliances to control mobile populations; the transfer of responsibility of migration control from receiving to sending countries; and control practices that may not comply with international standards (Paoletti Citation2011, 274). Regardless of the form, these measures have one goal “to stop ‘undesirable’ migration prior to a migrant’s entry onto the national territory” (Faret, Anguiano Téllez, and Rodríguez-Tapia Citation2021, 65).

The externalization of migration control in the North American region started in the late 1980s after designing a cooperation program between the US and Mexico, Operation Hold the line, targeting Central American migration (Frelick Citation1991). The program boosted the presence of the US Border Patrol along the border, expedited asylum claims, established checkpoints in transit corridors, and included the training of Mexican officials in detecting fraudulent documents. Six months after the implementation, in June 1989, an internal memorandum to the then US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) Central Office contained detailed information about the level of involvement of the INS in Mexico and the “high-level cooperation” with Mexican Immigration Services (Frelick Citation1991, 212). Since then, diverse programs have been signed between the countries, externalizing the US border.

Migration management in Mexico: three decades of migration control, 1994–2018

The administrations of Carlos Salinas (1988-1994), Ernesto Zedillo (1994-200), Vicente Fox (2000-2006), Felipe Calderon (2006-2012), and Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018) followed a pattern of “governance by containment” (Calva Sánchez and Torre Cantalapiedra Citation2020; Faret, Anguiano Téllez, and Rodríguez-Tapia Citation2021; Villafuerte Solís and García Aguilar Citation2014). They instrumentalized diverse policies of containment since the 1990s. That is, policies towards the identification, apprehension, and deportation of irregularized migrants (Anguiano Téllez and Trejo Peña Citation2007; París Pombo Citation2017; Torre Cantalapiedra and Yee Quintero Citation2018; Varela Huerta Citation2015).

Following the process of externalization of migration control, Mexico and the US have collaborated on a series of programsFootnote3 that aimed to stem the arrivals of migrants into the US. The cooperation has included the hiring and training of Mexican officers, information exchange, transfer of financial resources to acquire security equipment, such as infrared camaras, drones, and camaras with night vision, and the construction of detention facilities (Anguiano Téllez and Trejo Peña Citation2007; Calva Sánchez and Torre Cantalapiedra Citation2020; Faret, Anguiano Téllez, and Rodríguez-Tapia Citation2021; Frelick Citation1991; París Pombo Citation2017). As a result of the collaboration, Mexico increased the number of checkpoints and revisions along the transit corridors. For instance, in 2001, with Southern Border Plan (Plan Frontera Sur), migration inspection and control activities extended from the Southern border to Veracruz, Tabasco, Chiapas, and Oaxaca, Campeche, Yucatán y Quintana Roo (Torre Cantalapiedra and Yee Quintero Citation2018; Anguiano Téllez and Trejo Peña Citation2007). In 2008, presidents Felipe Calderon and George Bush signed a security partnership called “Iniciativa Mérida,” under which US$ 2.8 billion were used to counter drug trafficking and organized crime (Vogt Citation2020). In practice, the money was directed toward immigration enforcement. Hence, Mexico continued the militarization of borders and routes, highways, and railways, air, and marine controls through the use of technology, the construction of detention facilities, and the training of officials in the name of national security (París Pombo Citation2017; Vogt Citation2020; Anguiano Téllez and Lucero Vargas Citation2020).

In 2014, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto officially launched the Southern Border Program (SBP), part of the National Security Plan to manage the so-called “humanitarian crisis” (Animal Político Citation2014; París Pombo Citation2017; Swanson et al. Citation2015; Torre Cantalapiedra and Yee Quintero Citation2018). The program targeted narcotrafficking, but in practice, the SBP aimed to prevent arrivals and increase the detection, detention, and deportation of undocumented migrants (Swanson et al. Citation2015). Particular emphasis was placed on apprehending and deporting unaccompanied minors, given that more than 67,000 minors were detained in the US in 2014 (DHS Citation2015).

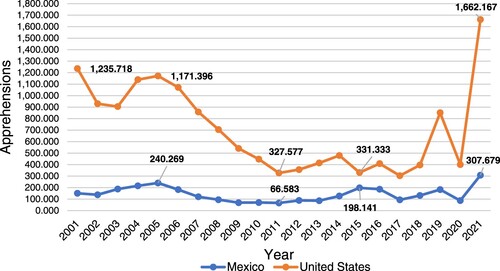

These actions have resulted in high rates of identification, detentions, and deportations of undocumented migrants in both countries (see ). The volume of apprehensions and deportations signals the harmful deterrence-based policy that governments have continued to apply and the limited screening, assessment of the needs, and inadequate due-process protections that migrants and asylum seekers have experienced (Dominguez-Villegas and Rietig Citation2015). For instance, from 2013 to 2019, more than 80 percent of those apprehended were deported from Mexico.

Figure 1. Annual Immigrant Apprehensions in Mexico and the US, FY2001-FY2021. Source: by the author with information from (UPMRIP Citation2021; Citation2018; Citation2015; Citation2022; Department of Homeland Security Citation2019; US Customs and Border Protection Citation2022).

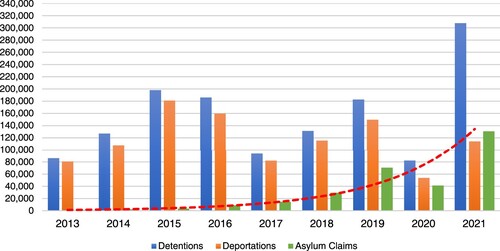

Moreover, in the last five years, the number of asylum claims has skyrocketed (see ), signaling the effect of the tightening of immigration control in Mexico and the US. In 2019, 70,709 people sought asylum in Mexico, and in 2021, more than 130,744 asylum claims were filed (COMAR Citation2020; Citation2022), almost doubling the number of 2019. Many applicants seek to settle in Mexico because the routes have become extremely dangerous, and the costs of border crossing have vastly increased (Castillo Citation2019; Faret, Anguiano Téllez, and Rodríguez-Tapia Citation2021; Torre Cantalapiedra Citation2020; Varela Huerta and McLean Citation2019).

Figure 2. Detentions, Deportations, and Asylum claims in Mexico, 2013-2021. Source: elaborated by the author with information from (UPMRIP Citation2022; COMAR Citation2022; UPMRIP Citation2021; Citation2015; Citation2018).

Finally, Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration saw the arrival of the so-called “Caravans of migrantsFootnote4” from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador in 2018 (Rizzo Lara Citation2021). The government first welcomed migrants with tear gas at the Mexico-Guatemala border (Arroyo et al. Citation2018; Calva Sánchez and Torre Cantalapiedra Citation2020; Pradilla Citation2019; Ramos Citation2018). After a series of clashes between caravan members and the police, the government let them cross the country. Days later, as part of the strategies to contain the influx of the caravans, the federal government launched a regularization program called “Estás en Tu Casa” (You are at home). The program would provide medical assistance, education, access to a temporary job, and a provisional identification. Migrants needed to meet three requirements: remain in Oaxaca and/ or Chiapas; register before the INM; and seek asylum (Anguiano Téllez and Lucero Vargas Citation2020; Secretaría de Gobernación Citation2018). Members of the caravan refused the offer because they did not want to be confined to the south of Mexico but wanted to continue their journey to El Norte (Martín Pérez Citation2018; Redacción AN Citation2018). The Plan was, in fact, a containment policy that aimed to keep migrants in the South of Mexico and prevent their arrival into the US.

In summary, past administrations have been using different strategies to deter and control the arrival and stay of irregularized migrants in the country. Although the various collaboration programs between the US and Mexico have been implemented to counter drug trafficking, human trafficking, and violence, the reality is that much of the resources have been used to keep migrants out of the US. The effects of these policies, including massive detentions, deportations, and asylum claims, have generated violence and police brutality against migrants. Before taking office, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) promised a change in migration policy. He had largely criticized Peña Nieto's approach to immigration. He stated his administration would create jobs, grant visas, and work with the region's governments to create development programs to disincentivize migration (Arroyo et al. Citation2018). AMLO emphasized that there were alternatives to deal with (irregularized) migration other than using armed forces and the police, and stated that his administration would respect migrant human rights. Finally, he claimed Central Americans would not be mistreated (MORENA Citation2018, paras. 6–8).

Migration policy under AMLO’s administration, 2018–2024

López Obrador took office on December 1, 2018, in the middle of the mediatic turmoil, given the arrival of the migrant caravans and the pressure from the US. On December 18, the incumbent administration outlined the New Migration Policy (NMP) components. The NMP was embedded in a more extensive transformation process (and discourse) that the administration aimed to implement. The NMP was built upon two axes: the defense and respect of migrants’ human rights and the promotion of economic development in sending communities to address the structural causes of the migration (UPMRIP Citation2019). The NMP has seven components: shared responsibility; regular, safe, and orderly mobility and migration; attention to irregular migration; strengthening of institutional capacity; protection of Mexicans overseas; integration and reintegration of migrants; and sustainable development in migrant communities (UPMRIP Citation2019).

Together, the components offered a comprehensive approach to migration as they sought to address the structural causes of migration; provide physical and psychological protection measures to irregular migrants, and a path for their regularization in the country; strengthen the capacities of institutions that offer services to migrants, especially the INM, COMAR, and the Migration Policy Unit; and foster the integration and inclusion of migrants into the Mexican society, as they have active participation in the definition, execution, and accountability of policies (UPMRIP Citation2019). According to Hernández López (Citation2020), the administration's challenge was to create strategies and concrete initiatives to address the above aims. Hernández stressed that the biggest challenge was to create a dialogue with the US, as any decision made in migration will be conditioned by the inevitable proximity of Mexico to the US (Hernández López Citation2020, 170).

The application of the NMP included, first, the signing of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration (GCM) in December 2018. Party countries are committed to creating and, more importantly, implementing mechanisms against human trafficking, family separation, criminalization of migration, and arbitrary detention (Noticias ONU Citation2018). In March 2019, in a press release, the Mexican Secretary of Foreign Affairs stated that Mexico was the first to put into practice the principles of the GCM (as the government granted about 13,000 temporary humanitarian visas to caravan members in January 2019). In doing so, he stressed, “Mexico has stopped deporting hundreds of thousands of Central American migrants in contrast with the migration paradigm of past administrations […] Thanks to this New Migration Policy, we have corrected the fundamental error, that of illegality, that condemns migrants to marginalization and precarityFootnote5” (SRE Citation2019a, paras. 1–3).

Second, the administration sought to strengthen institutional capacity. A critical action in this rubric was a restructuring at the directive and operative level of the INM. The administration appointed Tonatiuh Guillén López as INM Commissioner and Andrés Alfonso Ramírez Silva as General Coordinator of COMAR (Redacción Ejecentral Citation2018). In a press conference, where both commissioners were introduced, the former Minister of Interior emphasized: “migrants have rights, they were not going to be stigmatized, criminalized, or persecuted” and that the appointed directors would honor that (Redacción Ejecentral Citation2018, para. 3). The restructure at the operative level aimed to cease officials who had been involved in criminal activities, such as corruption and human trafficking, and had violated migrant human rights. According to AMLO, in June 2019, more than 500 officers were fired as part of a “clean-up operation” (AFP Citation2019), on top of the 30 that were removed in Tamaulipas after the disappearance (kidnapping) of 22 Central American migrants (SinEmbargo Citation2019). Moreover, the INM was to train officers on human rights principles and human trafficking; build new detention centers, and acquire technology that could facilitate the admission and identification of migrants.

Instruments of migration control

In the remaining section, I review five initiatives that the current administration has employed to manage irregularized migration; then, I analyze these strategies to assess if they are aligned with the components and goals of the NMP. I selected these initiatives based on their importance. Other scholars have also highlighted their relevance (Anguiano Téllez and Lucero Vargas Citation2020; Calva Sánchez and Torre Cantalapiedra Citation2020; Hernández López Citation2020).

1. Temporary protection mechanisms. In January 2019, new groups of migrants arrived at the Mexico-Guatemala Border.Footnote6 On January 18, 2019, the federal government fashioned the Plan de Atención a Caravana Migrante (Attention Plan to the Migrant Caravan) to manage the situation. The Plan aimed to provide medical assistance, shelter, and legal orientation (Secretaría de Seguridad y Protección Ciudadana Citation2019). The government created an emergent program to register migrants in Tapachula, Chiapas, and regularize their stay, issuing temporary protection permits on humanitarian grounds, TVRH. On January 28, 2019, the end date of the programFootnote7, migrants had requested 12,574 visas (Observatorio de Legislación Migratoria Citation2019). AMLO declared that the permit was a mechanism to encourage migrants fleeing violence and insecurity to stay in Mexico and avoid going to the US. With the measure, he was trying to prevent a possible source of disagreement between the two countries (Ernst and Semple Citation2019).

In a conference presentation in February 2019, Olga Sanchez Cordero, Minister of the Interior, underscored that the Plan had been successful as only 10 percent of those who crossed into Mexico with the caravan continued their journey up northFootnote8 while the rest of the migrants (90 percent of 13,500) received humanitarian permits. Moreover, Cordero stressed that different job agencies were actively recruiting migrants for various positions to prevent further movement from Central America (to Mexico) and the South–North movement within Mexico (MPI Citation2019).

2. Migrant Protection Protocols. The first group of people that left San Pedro Sula, Honduras, in October 2018 arrived in Mexico weeks before the intermediate elections for Congress and the Senate in the US. Amid the significant media coverage, Trump used the caravans to reinforce a xenophobic, racist, anti-immigrant discourse, favoring the channeling of resources to fortify the US Southern Border (Fernández Casanueva, Carte, and Rosas Citation2018). The immediate response was to deploy more than 5,000 immigration officers down the border (BBC News Citation2018). Trump framed the caravan as an invasion; thus, border protection was a matter of national security. As migrants continued to arrive, in December 2018, the US government launched the “Migrant Protection Protocols” (MPP), an initiative whereby undocumented foreigners entering or seeking admission to the US were returned to Mexico for the duration of their immigration proceedings (Calva Sánchez and Torre Cantalapiedra Citation2020; DHS Citation2019). The MPP was implemented on January 24, 2019, after Mexico granted the humanitarian permits (Calva Sánchez and Torre Cantalapiedra Citation2020).

The MPP -also known as Quédate en Mexico- [Remain in Mexico], meant that thousands of Central Americans that arrived in the US to seek asylum were sent back to Mexican border towns, Ciudad Juarez, Matamoros, Nuevo Laredo, Tijuana, Mexicali, to wait for admission, court hearings, and adjudication. The initiative shuddered migrants who traveled more than 3,000 km to arrive in the US. Mexico agreed to providing migrants with humanitarian protections, including immigration documentation and access to education, healthcare, and employment (DHS Citation2019). According to official documents, by December 31, 2020, 68,039 people were enrolled in the MPP, and only 531 had received “relief,” that is, only 0.7 percent of the applicants received asylum, statutory withholding of removal, and withholding of removal under the Convention Against Torture (DHS Citation2021a).

In February 2021, the DHS started to process into the US specific individuals that were enrolled in the MPP and had pending cases before the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) (DHS Citation2021b). After a detailed examination, in June 2021, president Joe Biden signed an Executive order to terminate the MPP program, and the Secretary of Homeland Security terminated it while the processing of individuals continued. However, on August 15, as part of a lawsuit brought by the states of Texas and Missouri, a federal judge ordered the Biden administration to “enforce and implement MPP in good faith” (American Immigration Council Citation2021). On August 25, the processing of individuals enrolled in MPP was suspended (DHS Citation2021c). Finally, the Biden administration announced the termination of the MPP on October 29, which could only be effective until the ruling by which the MPP is required to be reinstated was overturned (DHS Citation2021d, para. 5). After negotiations with the Mexican government, the MPP was reinstated on December 06. The ruling confirmed the instauration of the MPP (Center for Migration Studies Citation2021).

3. Acquiescence: The “deal” between Mexico and the US. Throughout the first six months of 2019, migrants continued to arrive in Mexico and the US. As a result, in May, President Trump announced an increase in import tariffs on Mexican products, progressively from 5-to 25 percent, because “Mexico was not doing enough to control migration” (BBC, 2019). In a tweet, he expressed:

On June 10, the United States will impose a 5% tariff on all goods coming into our country from Mexico until such time as illegal migrants coming through Mexico and into our Country, STOP. The Tariff will gradually increase until the Illegal Immigration problem is remedied (Twitter, Trump, May 31, 2019)

Following a series of talks, in a joint declaration, the governments recognized “the vital importance of rapidly resolving the humanitarian emergency and security situation [for which they] will work together to immediately implement a durable solution” (Department of State Citation2019). They agreed on (a) Mexico would deploy its National Guard to curb irregular migration, firstly, to the southern border; (b) the US would expand the MPP across the Southern border; (c) in the event of not having the expected results, both governments would take action, and additional terms would be discussed and announced within 90 days; (d) the US and Mexico welcomed the adoption of the Comprehensive Development Plan to promote prosperity, good governance and security in Central America (Department of State Citation2019).

The aftermath of the “agreement” was the deployment of more than 25,000 Mexican officers of the National Guard to surveil the US-Mexico and Mexico-Guatemala borders (Calva Sánchez and Torre Cantalapiedra Citation2020; Hernández López Citation2020). The actions resulted in the detention of 30,971 migrants in June 2019, which reported the highest record of detentions in 2019 (UPMRIP Citation2020a). The INM released figures that showed a decrease in arrivals in the months that followed the implementation of such a strategy. For instance, there were 12,773 and 11,814 detentions in September and October, respectively; in contrast with 21,745 and 22,949 detentions in April and May before the measures were enacted (Ibid). In the weeks that followed the deal, the US saw a 28 percent drop in apprehensions, the first decrease in a year (Fredrick Citation2019).

As part of the agreement, the Mexican government implemented a Comprehensive Development Plan (PDI) in collaboration with the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The PDI is “a practical and effective answer to the idea that no one should be forced to migrate due to poverty or insecurity” (SRE Citation2019b, para. 2). At the same time, AMLO stated that this Plan was an effective way to promote development in home countries and decrease incoming flows. Under the PDI, the governments of El Salvador and Mexico signed a cooperation agreement to encourage regional development. Mexico had allocated a budget of 30 million dollars to be spent on sowing 50,000 hectares and creating 20,000 jobs in El Salvador. More agreements were signed with Guatemala and Honduras, aiming to plant 200,000 hectares by the three countries (Zavala Citation2019).

4. Legal and physical violence. In January 2020, Central Americans formed new caravans to arrive in Mexico and the US. This time, the current administration's response was different from that of 2019. Instead of granting temporary humanitarian permits, the Mexican government deployed even more national guard officials and immigration officers to the Mexico-Guatemala border to prevent migrants from entering the country, both to Ciudad Hidalgo, Chiapas, and El Ceibo, Tabasco.

Between 17 and 23 January 2020, different groups of migrants tried to enter the country using two routes, Chiapas and Tabasco. The first group of about 2,000 people decided to cross Mexico via Chiapas, but they were not allowed to enter together; instead, the federal government asked them to enter in small groups of 20 people. After that, some migrants crossed Tapachula, Chiapas, but were detained and taken to the detention center “La Mosca” in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas, in what used to be a warehouse. The second group crossed via El Ceibo, Tabasco. Many of them were also detained and taken to the detention center in Villahermosa, Tabasco (Pradilla Citation2020).

On Monday, January 20, 2020 the caravan tried to enter again, but hundreds of national guard and border patrol officers were guarding the gate, at the border. Many migrants then crossed into Mexico through the Suchiate River in Ciudad Hidalgo, Chiapas. Meanwhile, migrants at the international bridge were repelled with tear gas. Migrants who entered Mexican territory were chased by border patrol and police officers. The government used special equipment, such as cameras with night vision, to identify and capture those who had made their way into the country (INM Citation2020b). Once they were caught, they were placed in detention centers. After the events, many migrants decided to return to Guatemala (Astles Citation2020; OIM Citation2020).

5. Expansion of immigration enforcement. To carry out actions of containment, in 2019, the Mexican government granted the National Guard faculties to carry out migratory inspections at the borders and acrross the country, and detentions of migrants. Since then, the National Guard has carried out actions of immigration enforcement. In August 2021, migrants and asylum seekers formed a new caravan in Mexico. This caravan differed from others because it was created in Mexico, not Central America. On August 28, 2021, about 600 Haitians, Venezuelan, and Central American migrants and asylum seekers formed a new caravan to cross Mexico (Forbes Citation2021). They had been stuck in Tapachula for months waiting for a resolution of their cases. Days before the caravan departed, migrants and asylum seekers protested, marched, and claimed in front of the offices of the INM in Tapachula, seeking a response from the authorities. Without clear answers, the caravan moved forward. Soon after, migrants encountered the national guard, military, and immigration officers who blocked their way and violently disarticulated the caravan. AMLO stated that his government would continue containing migration and stressed the need for more significant involvement of the US in the matter (Redacción Animal Político Citation2021). Tapachula is “home” to 125,000 undocumented migrants and asylum seekers who had been stuck there waiting for resolutions of their cases (Forbes Citation2021). The city is overflooded, and migrants are unemployed, sleeping in tents in the parks, and living in very precarious situations.

After the national guard and immigration officers disarticulated the first caravan (that of August 2021), migrants formed two more caravans in Tapachula. Both were also blocked and disarticulated by members of the national guard, the marine, and the INM. However, migrants kept resisting the containment and control practices of the government and created a new caravan. The march with the slogan “Por la libertad, la dignidad, y la paz” [For freedom, dignity, and peace] left Tapachula on October 23, 2021. It grew in size and demographic composition as more than 6,000 migrants, and asylum seekers from different nationalities became part of it. One caravan member expressed, “we are going to ask to be set free in this country (…) we have been forced to stay here for six months, we cannot wait any longer, we do not have jobs” (DW Citation2021, para. 5). Like in the past, migration officers tried to stop the caravan on multiple occasions, but migrants resisted. Many migrants were detained, and others were injured due to the clashes (Lucumí Citation2021). In November 2021, the caravan leader rejected offers the Mexican government made of granting TVRH to vulnerable people that are part of the caravan and expressed their intention to go to Mexico City (Telesur Citation2021). The caravan arrived in Mexico City in December 2021(EFE Citation2021b).

Discussion

After reviewing the different strategies the current administration uses, I assess how and if they comply with the components of the NMP. First, I argue that granting temporary humanitarian permits, TVRH, was a containment strategy as it was used to keep migrants in the South of Mexico. The strategy was an ad-hoc measure employed amid the arrivals rather than a long-term strategy to alleviate (irregularized) migration; neither was it a formalized path to the regularization and inclusion of undocumented migrants, as envisioned in the NMP.

TVRH are temporary permits given on “humanitarian grounds” and are only valid for one year. Even with those, migrants are unable to work and live in precarious situations during their regularization process. Migrants with TVRH are in a liminal space (Menjívar Citation2006) whereby they can legally stay in the country, but they are “illegal,” as they cannot work, and their “legal” status is only temporal. Migrants’ inability to work forces them into the informal labor market, further increasing their economic insecurity, marginalization, exclusion, and exploitation as employers pay lower wages; migrants work longer hours and do not have access to social security (Angulo-Pasel Citation2022). As stated by Menjívar (Citation2006, 1003), “The multiple legal categories in immigration law, including in-between statuses, thus shape long-term immigrant incorporation, and thus, broader forms of citizenship and community belonging (and exclusion).” This liminal status and temporality then limit migrants’ inclusion and integration in Mexico. At the same time, migrants live in a constant state of “deportability” (De Genova Citation2002) whereby there is a constant possibility (and fear) of removal of the nation-state. Finally, with the granting of TVRH, migrants registered before the INM and were placed in short-term shelters, thus becoming subject to the state's discretion, surveillance, and control.

Second, Mexico’s acquiescence with the US concerning the MPP resulted in non-compliance with its migration policy. The NMP emphasized the respect and protection of migrants’ human rights. However, by allowing the implementation of the MPP, Mexico failed to respect migrants’ human rights as migrants enrolled in the MPPs were placed in camps in border towns, which are particularly dangerous given the presence of organized crime, further increasing their marginalization and vulnerability. Also, Mexico did not abide by its commitment to providing education, healthcare, and employment. In fact, the MPP has exposed migrants to kidnappings, extortion, and several forms of violence, including sexual abuse (HRW Citation2019; Mukpo Citation2020). In the two years of the initiative, more than 1,300 crimes have been committed against migrant populations, being organized crime and Mexican officers the primary offender (IMUMI Citation2021). The MPP also violates the right to asylum, due process, and the principle of non-refoulment (IMUMI Citation2021). Finally, the MPP is also a way to externalize US borders.

Third, with the bilateral “agreement” of June 2019, Mexico returned to the long-standing containment strategies of past administrations. As part of the agreement, Mexico committed to increasing migration control, resulting in historical detentions and deportations. In 2021, the INM detained 307,679 migrants (UPMRIP Citation2022), almost tripling the number of detentions in 2020, 82, 379 (UPMRIP Citation2021) (see ). As for deportations, in 2021, the government deported 114,366 people (UPMRIP Citation2022), and more than 1307,44 people filed for asylum (COMAR Citation2022), the highest number of applications since the creation of COMAR. In 2014, the year of the so-called “humanitarian crisis,” there were 127,149 and 107,814 detentions and deportations, respectively (UPMRIP Citation2015). Both indicators increased in 2015 when detentions skyrocketed to 198,141 and 181,163 deportations (UPMRIP Citation2018) after the implementation of the Southern Border Program. In other words, apprehensions in 2021 were higher than in 2015, signaling that the current administration is applying the same and even stricter containment policies than past administrations. The government's strategies to detain and deport migrants contrasted with the Global Compact on Migration principles, whereby detention would be used as an exceptional resource to manage undocumented migration.

Further, in 2019, the Mexican government set up 67 checkpoints in addition to the 194 official points of entry (95 air, 67 seas, and 62 lands) that are surveilled by immigration officers (INM Citation2020a). The army, the marine, and the national guard carried out vigilance activities. The INM stated that such activities had “optimal results” as the joint forces detained almost 180,000 undocumented migrants. Moreover, 15 detention centers and nine more facilities were renovated. The surveillance activities also resulted in the detention of allegedly 227 human traffickers along with 288 vehicles used for transporting irregular migrants.

Similarly, the INM stated that 97 percent of the population that entered Mexico in 2019 were regular migrants (around 37 million); however, a considerable budget was channeled towards the surveillance of the Mexican border to contain and stem undocumented migration, which barely accounted for three percent of the foreign population. Moreover, in 2021, revisions along highways in Mexico have resulted in the detention of 89,653 people compared to 1,165 detentions in 2018 (IMUMI Citation2021), showing the increased surveillance and migration control exercised across the country.

The actions proved how the “control and containment” perspective underlies the New Migration Policy. Rather than focusing on protecting, promoting, and guaranteeing human rights, the policy is oriented towards the identification, apprehension, and deportation of migrants. Thus, the government should increase the budget of the INM not to build new detention centers but open-door, long-term shelters where migrants can stay during their regularization procedures.

Fourth, the Mexican government responded aggressively to the arrival of new caravans in January 2020. The deployment of thousands of officers from different federal enforcement agencies to Tapachula and El Ceibo to block the entrance of irregularized migrants showed that the government would not tolerate the entry and stay of undocumented migrants. This is consistent with the declarations of the now INM Commissioner, Francisco Garduño Yáñez, who, in October 2019, stated that INM would send back migrants regardless of their country of origin. He said: “even if you are from Mars, we are going to send you back, even to India, even to Cameroon, or even to Africa […] It is impossible to have you here” (Redacción Animal Político Citation2019). His statements expressed xenophobic and racist sentiments that underlie the vision of the Migration Institute in Mexico.

Additionally, the government’s response to the arrivals with tear gas and violence evidenced the lack of respect for migrants’ human rights and understanding of the population's needs. Such responses contrasted with two components of the NMP, one that aimed to provide ways for migrants to move to and from Mexico safely, orderly, and regularly. The other sought to provide physical and psychological protection to migrant populations. Additionally, the actions contrasted with AMLOs statements at the beginning of his administration.

Fifth, Mexico continues to criminalize migration and has expanded immigration enforcement activities and agencies. It has used security forces to disarticulate the caravans that migrants have formed in Mexico. Even the president stated that Mexico would continue to detain irregularized migrants; likewise, the Secretary of Defence maintained that the army's main goal was to stop migration (EFE Citation2021a). The deployment of the national guard, the marine, the military, and the use of technology to identify migrants further criminalize irregularized migration. Hence, migrants are treated as criminals and a threat to national security rather than as people with rights and in need of protection. Additionally, migrants experience legal violence when applying for permits or asylum. They have to wait months before getting a resolution and need to comply with requirements that put them in a very precarious situation. Lastly, the physical violence exercised to block the caravans is inhumane, disproportional, and violates migrants’ human rights. Those actions contrast with the NMP principles and the statements of the former Secretary of Interior, as migrants continue to be persecuted, violented, marginalized, and stigmatized.

Conclusions

This paper has contributed to the literature on migration management by reviewing five bordering practices and instruments of migration control that the government of Mexico is employing to deter irregularized migrants from entering and staying in Mexico. It has shown how the tools used have gone from permissive to repressive. At the beginning of the administration, Mexico granted temporary humanitarian permits to control the movement and stay of migrants. However, as pressure from the US grew and migrants kept attempting to cross into Mexico, the government stopped granting such permits and turned to the long-standing measures to keep migrants from entering. Likewise, the paper highlighted the mismatch between the rhetoric of a human rights-based approach and the violent migration control practices exercised across the country.

Further, the data demonstrated the expansion of immigration enforcement activities and agencies. Currently, more state agencies are now assigned tasks of migration control. The marine, police, the army, and especially the national guard have been deployed to contain irregularized migrants, which contrasts with the principles of the Migration Law, whereby only the INM was authorized to carry out migration control activities.

The “deal” between the countries reflects power asymmetries between the US and Mexico and the influence of the US on Mexican foreign policy. With the collaboration programs between them and, more recently, with the MPPs, the US has continued to externalize its borders. The implementation and reinstalment of the MPP reflected the US policy of mass expulsion of asylum seekers and the continued criminalization and persecution of undocumented migrants and refugees. Mexico continues to consent to a policy that has torn apart families and has put migrants and asylum seekers in a desperate situation experiencing physical, economic, legal, and emotional violence and even death (National Immigrant Justice Center Citation2021). Amid the reinstalment of the MPP, Mexico should have refused the measure to avoid further human rights violations and deaths. Being acquiescent of the US policies perpetuates the systemic violation of migrants’ and asylum seekers’ human rights. Other agreements between the US, Guatemala, and El Salvador, such as that of safe third countries, are deemed containment strategies that further externalize the US border to Central America. These later agreements were preceded by threats and punitive measures that the Trump administration used to force their signing.

Moreover, the PDI is far from being the answer to migration. The idea that PDI could be a resource to disincentivize migration only shows the lack of understanding of the migration phenomenon. The history of poverty, violence, insecurity, and corruption in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador cannot be reduced to a cropping program or a cash-based intervention scheme. Sending and receiving countries must acknowledge the structural causes of migration to create and enact adequate mechanisms to address them.

Finally, the Mexican government has failed in different ways to meet the standards set by its Migration Law to promote, respect, protect and guarantee migrant human rights. The creation and reforms to the Migration Law have not been enough. The Mexican government has violated migrants’ rights with its actions, omissions, and acquiescence to US policies. The Mexican state has a historical debt to migrants and asylum seekers. For decades, the Mexican government has not provided protective measures to many of those fleeing violence, insecurity, poverty, and political repression; instead, it has punished and criminalized many of those who crossed the border irregularly. The new administration said to strive for a transformation where migrants were at the core of the NMP, and their rights and dignity were a priority. Nonetheless, the NMP has yet to show its ability to achieve such a change. Mexico can decide to change its strategies to finally ensure the protection and security of migrants while transforming its overall approach to migration management.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Tarjeta de Visitante por Razones Humanitarias is regulated by the Migration Law, Article 52, Frac.V. Migrants, unaccompanied minors, or asylum seekers can apply for this type of visa if they are victims of crime in Mexico. It is valid for one year (Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión Citation2011)

2 The US provided financial and military support to regimes in Central America, who, in turn, caused atrocities on civilians (Nepstad and Smith Citation2001; París Pombo Citation2017; Stanley Citation1987).

3 See the Operation Hold the Line (Frelick Citation1991); Southern Plan (Anguiano Téllez and Trejo Peña Citation2007; Torre Cantalapiedra and Yee Quintero Citation2018); Southern Border Program (Animal Político Citation2014; Swanson et al. Citation2015); Iniciativa Merida (Vogt Citation2020)

4 There is no consensus about the number of people that arrived at the border; sources estimated 7,000, while others 4,000 (Ahmed Citation2019; Arroyo et al. Citation2018).

5 All the quotes, except for Meníivar’s and Nuñez’s, were translated by the author.

6 The Minister of the Interior estimated that about 13,500 people entered the county with the caravan of January 2019 (MPI Citation2019).

7 The fast-track program ended, but the government continued to grant visas based on the provisions of the law. According to the INM, 40,966 visas were granted in 2019 (UPMRIP Citation2020b).

8 Here, Sanchez Cordero explicitly refers to the large groups of people that arrived in January 2019.

Bibliography

- AFP. 2019. “Despiden a 500 agentes migratorios por corrupción; es una ‘limpia’ al INM, dice AMLO.” Animal Político, June 27, 2019. https://www.animalpolitico.com/2019/06/despiden-agentes-migratorios-corrupcion-amlo-limpia/.

- Ahmed, Azan. 2019. “El territorio de las pandillas en Honduras: ‘O nos matan o los matamos.’” The New York Times, May 4, 2019, sec. en Español. https://www.nytimes.com/es/2019/05/04/espanol/america-latina/honduras-mara-salvatrucha-violencia.html.

- Álvarez Velasco, Soledad. 2016. “Crisis migratoria contemporánea? Complejizando dos corredores migratorios globales.” Debate 97, Migraciones y Violencia, April, 55–171.

- American Immigration Council. 2021. “The ‘Migrant Protection Protocols.’” American Immigration Council. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/migrant-protection-protocols.

- Anguiano Téllez, María Eugenia, and Alma Trejo Peña. 2007. Políticas de Seguridad Fronteriza y Nuevas Rutas de Movilidad de Migrantes Mexicanos y Guatemaltecos. LiminaR Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos 5, no. 2: 47–65. doi:10.29043/liminar.v5i2.250.

- Anguiano Téllez, María Eugenia, and Chantal Lucero Vargas. 2020. La Construcción Gradual de la Política de Contención Migratoria en México. In Movilidad Humana en Tránsito: Retos de la Cuarta Transformación en Política Migratoria, eds. Daniel Villafuerte Solís, and María Eugenia Anguiano Téllez, 123–58. Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina: CLACSO.

- Angulo-Pasel, Carla. 2022. The Politics of Temporary Protection Schemes: The Role of Mexico’s TVRH in Reproducing Precarity among Central American Migrants. Journal of Politics in Latin America 14 (1): 84–102. doi:10.1177/1866802X211027886.

- Animal Político. 2014. “Peña Nieto pone en marcha el Programa Frontera Sur.” Animal Político (blog). July 8, 2014. https://www.animalpolitico.com/2014/07/en-esto-consiste-el-programa-que-protegera-a-migrantes-que-ingresan-a-mexico/.

- Arroyo, Emely, Brenda Cano, María Dolores París Pombo, Rubén Ruíz, Alejandro Palacios, and Jocelin Mariscal. 2018. “Cronología de La Caravana Centroamericana 2018.” Observatorio de Legislación Migratoria. November 19, 2018. https://observatoriocolef.org/infograficos/cronologia-de-la-caravana-centroamericana/.

- Astles, Jacinta. 2020. “‘We Were Afraid’: Testimonies from the First Migrant Caravan of 2020.” Text. On the Move (blog). January 2020. https://rosanjose.iom.int/site/en/blog/we-were-afraid-testimonies-first-migrant-caravan-2020.

- BBC News. 2018. “US Sending 5,200 Troops to Border with Mexico.” BBC News, October 30, 2018, sec. US & Canada. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-46026050.

- Calva Sánchez, Luis Enrique, and Eduardo Torre Cantalapiedra. 2020. Cambios y Continuidades en la Política Migratoria Durante el Primer año del Gobierno de López Obrador. Norteamérica 15, no. 2, doi:10.22201/cisan.24487228e.2020.2.415.

- Castillo, Guillermo. 2019. Migración Forzada y Procesos de Violencia: Los Migrantes Centroamericanos en su Paso por México. Revista Española de Educación Comparada 35, no. December: 14. doi:10.5944/reec.35.2020.25163.

- Center for Migration Studies. 2021. “The Migrant Protection Protocols: Policy History and Latest Updates.” The Center for Migration Studies of New York (CMS) (blog). 2021. https://cmsny.org/mpp-briefing-graphic/.

- Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión. 2011. Ley de Migración. http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LMigra_200521.pdf.

- COMAR. 2020. “Estadísticas de solicitantes de la condición de refugiado en México.” Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados. April 1, 2020. http://www.gob.mx/comar/articulos/estadisticas-de-solicitantes-de-la-condicion-de-refugiado-en-mexico.

- COMAR. 2022. “La COMAR en números.” La COMAR en números (blog). April 1, 2022. http://www.gob.mx/comar/articulos/la-comar-en-numeros-298468?idiom=es.

- De Genova, Nicholas. 2002. “Migrant “Illegality” and Deportability in Everyday Life Annual Review of Anthropology 31: 419–47. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.040402.085432.

- Department of Homeland Security. 2019. “U.S. Border Patrol Total Apprehensions (FY 1925 - FY 2019).” US Customs and Border Protection. 2019. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/media-resources/stats.

- Department of State. 2019. “Joint Declaration and Supplementary Agreement.” Department of State. June 7, 2019. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/19-607-Mexico-Migration-and-Refugees.pdf.

- DHS. 2015. “Southwest Border Unaccompanied Alien Children FY 2014.” US Customs and Border Protection. November 24, 2015. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-border-unaccompanied-children/fy-2014.

- DHS. 2019. “Migrant Protection Protocols.” Department of Homeland Security. January 24, 2019. https://www.dhs.gov/news/2019/01/24/migrant-protection-protocols.

- DHS. 2021a. “Migrant Protection Protocols Metrics and Measures.” Department of Homeland Security. January 21, 2021. https://www.dhs.gov/publication/metrics-and-measures.

- DHS. 2021b. “Migrant Protection Protocols (Biden Administration Archive).” Department of Homeland Security. February 17, 2021. https://www.dhs.gov/archive/migrant-protection-protocols-biden-administration.

- DHS. 2021c. “Migrant Protection Protocols.” Department of Homeland Security. October 15, 2021. https://www.dhs.gov/migrant-protection-protocols.

- DHS. 2021d. “DHS Issues A New Memo to Terminate MPP.” Department of Homeland Security. October 29, 2021. https://www.dhs.gov/news/2021/10/29/dhs-issues-new-memo-terminate-mpp.

- Dominguez-Villegas, Rodrigo, and Victoria Rietig. 2015. “Migrants Deported from the United States and Mexico to the Northern Triangle: A Statistical and Socioeconomic Profile.” Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/migrants-deported-united-states-and-mexico-northern-triangle-statistical-and-socioeconomic.

- DW. 2021. “Miles de migrantes inician caravana desde frontera sur de México a la capital | DW | 23.10.2021.” DW.COM. October 23, 2021. https://www.dw.com/es/miles-de-migrantes-inician-caravana-desde-frontera-sur-de-m%C3%A9xico-a-la-capital/a-59606639.

- EFE. 2021a. “El Ejército mexicano tiene como objetivo ‘detener toda la migración.’” Los Angeles Times en Español, August 27, 2021, sec. EEUU. https://www.latimes.com/espanol/eeuu/articulo/2021-08-27/el-ejercito-mexicano-tiene-como-objetivo-detener-toda-la-migracion.

- EFE. 2021b. “Caravana migrante llegará a Ciudad de México tras última parada en Puebla.” Los Angeles Times en Español, December 10, 2021, sec. México. https://www.latimes.com/espanol/mexico/articulo/2021-12-10/caravana-migrante-llegara-a-ciudad-de-mexico-tras-ultima-parada-en-puebla.

- Ernst, Jeff, and Kirk Semple. 2019. “Las visas humanitarias en México: un imán para la nueva caravana migrante.” The New York Times, January 25, 2019, sec. en Español. https://www.nytimes.com/es/2019/01/25/espanol/america-latina/mexico-migrantes-plan-atencion.html.

- Faret, Laurent, María Eugenia Anguiano Téllez, and Luz Helena Rodríguez-Tapia. 2021. Migration Management and Changes in Mobility Patterns in the North and Central American Region. Journal on Migration and Human Security 9, no. 2: 63–79. doi:10.1177/23315024211008096.

- Fernández Casanueva, Carmen, Lindsey Carte, and Lourdes Rosas. 2018. “Honduras: relato de un éxodo anunciado.” Animal Político (blog). October 29, 2018. https://www.animalpolitico.com/blog-invitado/honduras-relato-de-un-exodo-anunciado/.

- Forbes. 2021. “Fotogalería| López Obrador afirma que seguirá ‘conteniendo’ la migración.” Forbes México, August 29, 2021. https://www.forbes.com.mx/fotogaleria-lopez-obrador-afirma-que-seguira-conteniendo-la-migracion/.

- Fredrick, James. 2019. “How Mexico Beefs Up Immigration Enforcement To Meet Trump’s Terms.” NPR, July 13, 2019, sec. World. https://www.npr.org/2019/07/13/740009105/how-mexico-beefs-up-immigration-enforcement-to-meet-trumps-terms.

- Frelick, Bill. 1991. Running the Gauntlet: The Central American Journey in Mexico. International Journal of Refugee Law 3, no. 2: 208–42. doi:10.1093/ijrl/3.2.208.

- Gambino, Lauren, and David Agren. 2019. “Trump Announces Tariffs on Mexico until ‘Immigration Remedied.’” The Guardian, May 31, 2019, sec. US news. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/30/trump-mexico-tariffs-migration.

- Hernández López, Rafael Alonso. 2020. “Entre el Cambio y la Continuidad. La Encrucijada de la Política Migratoria Mexicana.” In Movilidad Humana en Tránsito: Retos de la Cuarta Transformación en Política Migratoria, edited by Daniel Villafuerte Solís and María Eugenia Anguiano Téllez, 235. Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina: CLACSO.

- Hess, Sabine. 2017. Border Crossing as Act of Resistance: The Autonomy of Migration as Theoretical Intervention into Border Studies. In Resistance: Subjects, Representations, Contexts, eds. Martin Butler, Paul Mecheril, and Lea Brenningmeyer, 87–100. Transcript Verlag. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1xxrtf.8.

- Hollifield, James F. 2006. El emergente Estado migratorio.” In Miguel Ángel Porrúa, by Alejandro Portes and Josh DeWind, Repensando las migraciones. Nuevas perspectivas teóricas y empíricas.:30. México: Editorial Miguel Ángel Porrúa, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, Instituto Nacional de Migración.

- HRW. 2019. “US Move Puts More Asylum Seekers at Risk.” Human Rights Watch (blog). September 25, 2019. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/09/25/us-move-puts-more-asylum-seekers-risk.

- IMUMI. 2021. “Estamos Frente a Una Emergencia Humanitaria, Concluyen Comisionadas de La CIDH.” October 27, 2021. https://imumi.org/2021/10/27/estamos-frente-a-una-emergencia-humanitaria-concluyen-comisionadas-de-la-cidh/.

- INM. 2020a. “INM informa sobre acciones en 2019 para mantener una migración segura, ordenada y regular. Boletín No. 004/2020.” gob.mx (blog). January 3, 2020. http://www.gob.mx/inm/prensa/inm-informa-sobre-acciones-en-2019-para-mantener-una-migracion-segura-ordenada-y-regular-231026?idiom=es.

- INM. 2020b. “Más de 2 mil personas migrantes centroamericanas rescatadas en Chiapas y Tabasco. Comunicado No. 014/2020.” gob.mx. January 22, 2020. http://www.gob.mx/inm/prensa/mas-de-2-mil-personas-migrantes-centroamericanas-rescatadas-en-chiapas-y-tabasco-232693?idiom=es.

- Karni, Annie, Ana Swanson, and Michael D. Shear. 2019. “Trump Says U.S. Will Hit Mexico With 5% Tariffs on All Goods.” The New York Times, May 30, 2019, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/30/us/politics/trump-mexico-tariffs.html.

- Lucumí, Juan Pablo. 2021. “Caravana de migrantes cambió su ruta y continúa su camino hacia el sur de México.” France 24, November 7, 2021, sec. América Latina. https://www.france24.com/es/am%C3%A9rica-latina/20211107-caravana-de-migrantes-cambi%C3%B3-su-ruta-y-contin%C3%BAa-su-camino-hacia-el-sur-de-m%C3%A9xico.

- Martín Pérez, Fredy. 2018. “Migrantes en asamblea rechazan plan de Peña Nieto.” El Universal, October 26, 2018. https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/politica/migrantes-en-asamblea-rechazan-plan-de-pena-nieto.

- Massey, Douglas S. 2002. A Synthetic Theory of International Migration.” In World in the Mirror of International Migration, edited by Vladimir A. Iontsev. Scientific Series: International Migration of Population: Russia and the Contemporary World 10. Moscow: MAX Press.

- Massey, Douglas S., Jorge Durand, and Nolan J. Malone. 2002. Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Immigration in an Era of Economic Integration. Russell Sage Foundation. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.77589781610443821.

- Menjívar, Cecilia. 2000. Fragmented Ties: Salvadoran Immigrant Networks in America. First. University of California Press.

- Menjívar, Cecilia. 2006. Liminal Legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan Immigrants’ Lives in the United States. American Journal of Sociology 111, no. 4: 999–1037. doi:10.1086/499509.

- Menjívar, Cecilia, and Andrea Gómez Cervantes. 2018. “El Salvador: Civil War, Natural Disasters, and Gang Violence Drive Migration.” Migration Policy Institute. August 29, 2018. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/el-salvador-civil-war-natural-disasters-and-gang-violence-drive-migration.

- MORENA. 2018. “En México habrá trabajo para mexicanos y centroamericanos; hermanos migrantes cuentan con nosotros, afirma AMLO – Morena – La esperanza de México.” Noticias (blog). October 21, 2018. https://morena.si/en-mexico-habra-trabajo-para-mexicanos-y-centroamericanos-hermanos-migrantes-cuentan-con-nosotros-afirma-amlo/.

- MPI. 2019. “Una nueva política migratoria para una nueva era: Una conversación con la Secretaria de Gobernación Olga Sánchez Cordero.” February 28, 2019. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/multimedia/una-nueva-politica-migratoria-para-una-nueva-era-una-conversacion-con-segob?qt-multimedia_tabs=0.

- Mukpo, Ashoka. 2020. “Asylum-Seekers Stranded in Mexico Face Homelessness, Kidnapping, and Sexual Violence.” American Civil Liberties Union. March 2020. https://www.aclu.org/issues/immigrants-rights/immigrants-rights-and-detention/asylum-seekers-stranded-mexico-face.

- National Immigrant Justice Center. 2021. “NIJC Condemns Decisions Calling for the Resumption of the Deadly ‘Remain in Mexico’ Policy and the Expanded Use of ICE Detention.” National Immigrant Justice Center. August 20, 2021. https://immigrantjustice.org/press-releases/nijc-condemns-decisions-calling-resumption-deadly-remain-mexico-policy-and-expanded.

- Nepstad, Sharon Erickson, and Christian Smith. 2001. The Social Structure of Moral Outrage in Recruitment to the U.S. Central America Peace Movement. In Passionate Politics: Emotions and Social Movements, eds. Jeff Goodwin, James M. Jasper, and Francesca Polletta, 158–74. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Noticias ONU. 2018. “Pacto Mundial sobre Migración: ¿a qué obliga y qué beneficios tiene?” Noticias ONU. December 5, 2018. https://news.un.org/es/story/2018/12/1447231.

- Núñez, Adriana C. 2020. Collateral Subjects: The Normalization of Surveillance for Mexican Americans on the Border. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 6, no. 4: 548–61. doi:10.1177/2332649219884085.

- Observatorio de Legislación Migratoria. 2019. “INM: Solicitudes Tarjetas de Visitante Por Razones Humanitarias 17-29 Enero 2019.” Observatorio de Legislación Migratoria. March 2, 2019. https://observatoriocolef.org/infograficos/inm-solicitudes-tarjetas-de-visitante-por-razones-humanitarias-17-29-enero-2019/.

- OIM. 2020. “Informe de Situación: Caravana de Migrantes Frontera Sur, Mexico 17-27 de Enero, 2020.” OIM. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/informe_de_situacion_frontera_sur-mexico-sitrep-20200127-v1.pdf.

- Paoletti, Emanuela. 2011. Power Relations and International Migration: The Case of Italy and Libya. Political Studies 59, no. 2: 269–89. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00849.x.

- París Pombo, María Dolores. 2017. Violencias y Migraciones Centroamericanas en México. Primera Edición. Tijuana, Baja California, México: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.

- Pradilla, Alberto. 2019. Caravana: Cómo el éxodo centroamericano salió de la clandestinidad. First Edition. Debate. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/634273/caravana-como-el-exodo-centroamericano-salio-de-la-clandestinidad–caravan-the-exodus-by-alberto-pradilla/.

- Pradilla, Alberto. 2020. “Un año de caravanas con AMLO: de las visas en libertad al encierro en una bodega.” Animal Político, January 19, 2020, sec. Animal Politico. https://www.animalpolitico.com/2020/01/caravanas-migrantes-visas-bodega/.

- Ramos, Fred. 2018. “Centroamericanos, ‘Bienvenidos a México.’” El Faro, October 18, 2018, sec. Migración. https://elfaro.net/es/201810/ef_foto/22596/Centroamericanos-“bienvenidos-a-México”.htm.

- Redacción AN. 2018. “Rechaza caravana migrante plan ‘Estas en Tu Casa’, de EPN.” Aristegui Noticias, October 27, 2018. https://aristeguinoticias.com/2610/mexico/rechaza-caravana-migrante-plan-estas-en-tu-casa-de-epn/.

- Redacción Animal Político. 2019. “Migrantes serán deportados así sean de Marte: titular de INM; acusa a africanos de agredir a la Guardia.” Animal Político, October 21, 2019. https://www.animalpolitico.com/2019/10/migrantes-deportados-inm-marte-guardia/.

- Redacción Animal Político. 2021. “México seguirá ‘conteniendo’ migrantes, dice AMLO; pide a EU un plan de desarrollo para Centroamérica.” Animal Político (blog). August 29, 2021. https://www.animalpolitico.com/2021/08/mexico-conteniendo-migrantes-amlo-eu-visas/.

- Redacción Ejecentral. 2018. “Van Tonatiuh Guillén al INM y Andrés Ramírez a Comar.” Eje Central, October 29, 2018. https://www.ejecentral.com.mx/van-tonatiuh-miguel-lopez-al-inm-y-andres-ramirez-comar/.

- Rizzo Lara, Rosario de la Luz. 2021. La Caminata Del Migrante: A Social Movement. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47, no. 17: 3891–3910. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2021.1940111.

- Secretaría de Gobernación. 2018. “El Presidente Enrique Peña Nieto anuncia el Plan ‘Estás en tu casa’ en apoyo a los migrantes centroamericanos que se encuentran en México.” Prensa. October 26, 2018. http://www.gob.mx/segob/prensa/el-presidente-enrique-pena-nieto-anuncia-el-plan-estas-en-tu-casa-en-apoyo-a-los-migrantes-centroamericanos-que-se-encuentran-en-mexico-180268?hootPostID=97986b618b4d2d255e90b9dd87766f5f.

- Secretaría de Seguridad y Protección Ciudadana. 2019. “México activa Plan de Atención a Caravana Migrante con visión humanitaria.” Prensa. January 18, 2019. http://www.gob.mx/sspc/prensa/mexico-activa-plan-de-atencion-a-caravana-migrante-con-vision-humanitaria.

- SinEmbargo. 2019. “Autoridades cesan a 30 funcionarios del INM; aún buscan a 22 migrantes desaparecidos.” SinEmbargo MX, March 15, 2019, sec. FOTO DEL DÍA. https://www.sinembargo.mx/15-03-2019/3550943.

- SRE. 2019a. “La política migratoria de México es soberana y busca preservar los derechos de los migrantes.” Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. March 3, 2019. http://www.gob.mx/sre/prensa/la-politica-migratoria-de-mexico-es-soberana-y-busca-preservar-los-derechos-de-los-migrantes.

- SRE. 2019b. “The Foreign Secretary Announces Launch of the Comprehensive Development Plan with Central America at United Nations.” June 19, 2019. http://www.gob.mx/sre/articulos/the-foreign-secretary-announces-the-launch-of-the-comprehensive-development-plan-with-central-america-at-united-nations-205538.

- Stanley, William Deane. 1987. Economic Migrants or Refugees from Violence?: A Time-Series Analysis of Salvadoran Migration. Latin American Research Review 22, no. 1: 24.

- Swanson, Kate, Rebecca Torres, Amy Thompson, Sarah Blue, and Óscar Misael Hernández Hernández. 2015. “A Year After Obama Declared a ‘Humanitarian Situation’ at the Border, Child Migration Continues.” NACLA, August 27, 2015. https://nacla.org/news/2015/08/27/year-after-obama-declared-%E2%80%9Chumanitarian-situation%E2%80%9D-border-child-migration-continues.

- Telesur. 2021. “Caravana de migrantes llega a Oaxaca en México.” tele SUR, August 11, 2021, sec. Latinoamérica y el Caribe. https://www.telesurtv.net/news/caravana-migrantes-llega-oaxaca-mexico-20211108-0008.html.

- Torre Cantalapiedra, Eduardo. 2020. Destino y Asentamiento en México de los Migrantes y Refugiados Centroamericanos. Revista Trace 77, no. January: 122. doi:10.22134/trace.77.2020.726.

- Torre Cantalapiedra, Eduardo, and José Carlos Yee Quintero. 2018. “México ¿una Frontera Vertical? Políticas de Control del Tránsito Migratorio Irregular y sus Resultados, 2007-2016.” LiminaR Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos 16(2): 87–104. doi:10.29043/liminar.v16i2.599.

- Torres, Rebecca Maria. 2018. A Crisis of Rights and Responsibility: Feminist Geopolitical Perspectives on Latin American Refugees and Migrants. Gender, Place & Culture 25, no. 1: 13–36. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2017.1414036.

- UPMRIP. 2015. “Extranjeros Presentados y Devueltos, 2014.” Boletines Estadísticos. October 19, 2015. http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es//PoliticaMigratoria/CuadrosBOLETIN?Anual=2014&Secc=3.

- UPMRIP. 2018. “Extranjeros Presentados y Devueltos, 2015.” Boletines Estadísticos. September 13, 2018. http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es//PoliticaMigratoria/CuadrosBOLETIN?Anual=2015&Secc=3.

- UPMRIP. 2019. “Nueva Política Migratoria del Gobierno de México 2018-2024.” Secretaría de Gobernación. http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es/PoliticaMigratoria/Nueva_Politica_Migratoria.

- UPMRIP. 2020a. “Eventos de extranjeros presentados ante la autoridad migratoria, según entidad federativa y municipio, 2019.” Unidad de Política Migratoria. July 6, 2020. http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es/PoliticaMigratoria/CuadrosBOLETIN?Anual=2019&Secc=3.

- UPMRIP. 2020b. “Tarjetas de Visitantes Por Razones Humanitarias (TVRH) Emitidas, Según Continente, País de Nacionalidad y Entidad Federativa, Enero-Diciembre de 2019.” Boletines Estadísticos. July 6, 2020. http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es/PoliticaMigratoria/CuadrosBOLETIN?Anual=2019&Secc=2.

- UPMRIP. 2021. “Extranjeros Presentados y Devueltos, 2020.” Unidad de Política Migratoria. June 15, 2021. http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es/PoliticaMigratoria/CuadrosBOLETIN?Anual=2020&Secc=3.

- UPMRIP. 2022. “Extranjeros Presentados y Devueltos, 2021.” Boletines Estadísticos. 2022. http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es/PoliticaMigratoria/CuadrosBOLETIN?Anual=2021&Secc=3.

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection. 2022. “Total CBP Enforcement Actions.” U.S. Customs and Border Protection. 2022. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics.

- Varela Huerta, Amarela. 2015. “La ‘Securitización’ de la Gubernamentalidad Migratoria Mediante la ‘Externalización’ de las Fronteras Estadounidenses a Mesoamérica.” Con-temporánea 2 (4). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286938159_La_securitizacion_de_la_gubernamentalidad_migratoria_mediante_la_externalizacion_de_las_fronteras_estadounidenses_a_Mesoamerica.

- Varela Huerta, Amarela, and Lisa McLean. 2019. Caravana de Migrantes en México: Nueva Forma de Autodefensa y Transmigración. Revista CIDOB D'Afers Internacionals 122, no. September: 163–86. doi:10.24241/rcai.2019.122.2.163.

- Villafuerte Solís, Daniel, and María del Carmen García Aguilar. 2014. Migración, Derechos Humanos y Desarrollo. Aproximaciones Desde el sur de México y Centroamérica. Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. https://repositorio.unicach.mx/handle/20.500.12753/1285.

- Vogt, Wendy. 2020. Dirty Work, Dangerous Others: The Politics of Outsourced Immigration Enforcement in Mexico. Migration and Society 3: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3167/arms.2020.111404.

- Zavala, Misael. 2019. “México y El Salvador firman acuerdo del plan de desarrollo integral para Centroamérica.” El Universal, June 20, 2019. https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/politica/mexico-y-el-salvador-firman-acuerdo-de-desarrollo-integral-para-centroamerica.