ABSTRACT

Held every two years and alternating venues between Yagoua (Cameroon) and Bongor (Chad), the Tokna Massana border festival celebrates the identity and culture of the partitioned Masa peoples. This article explores how border festivals like Tokna Massana can complement and innovate the study of borders and borderlands. Building on participant observation, semi-structured interviews and archival research, we analyze how exacting cross-border festival planning and preparation in the Masa homeland and the diaspora make each new edition possible. We argue that border festivals are worth our attention because their repertoires illuminate underrepresented knowledge production and transmission choices. Moreover, the expectation of festive commemorations underlines processual and performative modes of engagement and management of identity and historical memory. They draw our attention to unexpected use, counter use, and repurposing of border spaces and infrastructures. Finally, the study of border festivals can reveal unacknowledged histories of practical governance.

Introduction

A sizeable crowd of festival goers ambled around the vast, sun-drenched grounds of a bus station in Bongor, Chad in early April 2022. Chadian festival organizers had designated and repurposed that bus station as the main stage of the eighth annual Tokna Massana international celebration —an observance of arts and culture that has brought ethnic Masa peoples partitioned by the Cameroon/Chad border together bi-annually since 2003. The bus station’s largest shaded area doubled as a VIP section while smaller covered areas on the periphery served as culture and history learning spaces. There, Masa elders narrated the significance of artifacts such as tightly woven shields and armor, gourds, and spears. Large color posters featuring photos of everyday life interspersed with images of past festival gatherings (e.g. bustling market spaces, dancers in procession, wrestling matches) addressed a question to younger generations of Masa: “Jeunes dans la ville. Aujourd’hui et demain?” (Young people in the city. Today and tomorrow?).

Those cooler spaces drew festival goers in, but many spectators had arrived early on the first day of programming to witness one of the cross-border celebration’s most popular events—the traditional Masa wrestling matches pitting Chadian wrestlers against Cameroonian wrestlers []. Wrestling has long been an integral part of the Masa cultural repertoire (Dumas-Champion Citation1983, 134–44; Garine Citation1964, 200) and the prestige associated with it continues to enjoy wide currency. Tracing its protagonism across years of festival archives, witnessing matches during the celebration, and interviewing lutte coaches and wrestlers as well as government officials who could speak to the broader cultural impact of the sport, it soon became apparent that wrestling is a collective practice of remembering and refining Masa identity. One interlocutor put it plainly: “Le premier [point] d’organisation de Tokna Massana, c’est la lutte. C’est le sport que les Masa pratiquent […] Pour tout homme masa, quand il y a regroupement, il y a lutte” (Wrestling has always had a place of choice in Tokna Massana. It is the Masa sport par excellence. Any meeting of Masa men is always accompanied by wrestling) (Interview, former wrestler and coach, 29 April 2023). Indeed, etymological studies of the word massana have identified it as a call to practice—to embody one’s role as a true male is to embody Masa identity (Haman Citation1996, 25). And while so-called “traditional Masa wrestling” is still very much understood as a quintessentially male practice within and beyond the confines of the border celebration, wrestling has gained popularity among Masa girls and women in recent years and the Bongor edition of 2017 included a female wrestling competition.

When staged as part of the Tokna Massana festival, the symmetry of two wrestlers standing face-to-face and competing on behalf of their respective countries for an international public, becomes performative. We may understand it as a “border enactment,” the tactile interface of two national representatives, which may combine human and/or non-human forces, staged at or in critical spatial dialogue with an international boundary line. A border enactment makes visible ordinary citizens’, and in this case, partitioned peoples’ agency and prerogative to practice the border on their own terms (Peña Citation2020, 6–7). The Tokna Massana celebration generates numerous border enactments, including a meticulously staged meet and greet between state authorities and celebration elites at the Logone River (the international boundary line “proper”). But that formality is not the focal point of this cross-border tradition. The festival mainstage in either Bongor or Yagoua animated by Masa peoples in communion (sharing space), in competition (wrestling), in procession (dancing), and in study (show and tell) “[re]constitutes territory”—mends land that is still theirs (Smith, Swanson, and Gökariksel Citation2016, 258). These corporeal practices performatively supersede colonial and postcolonial divide and conquer cartographic legacies, but the Masa do not use the Tokna Massana festival to deny the existence of an international boundary line. They purposefully invoke it to celebrate the resiliency of their identity and to maintain open lines of communication across Masa populations in their homeland and in the diaspora. With all of their expressive richness and logistical hiccups, these border enactments can be seen as a trope for the larger festival of which they are part.

Like border populations elsewhere, the Masa practice a “trans-border territoriality” (Brambilla Citation2007, 32; Flynn Citation1997; Nugent Citation2002). The study of border festivals, which calls for rigorous attention to embodiment, performativity, and the production of space, to the strategic and tactical repurposing of borderlands areas and infrastructures, and to the political economy of cross-border cooperation, reveals aspects of trans-border territoriality as well as underappreciated nuances of trans-border practice. One of those nuances is practical governance, which may be understood as forms of everyday governance that emerge out of the dynamic interplay between local borderlands populations and officials in a manner that is not reflected in manuals of border management. Indeed, as Paul Nugent reminds us, attending to these vital elements of border festival planning and execution can shed light on “the ways in which border populations have cut their own deals and established their own mechanisms for managing resources arising from the existence of the border (e.g. dealing with cross-border criminal acts such as cattle rustling and taxing trade)” (Nugent Citation2019a, 182–183).

Still, it may be easy to write this moment off, and border festival traditions in general, as too playful or too subjective to be consequential. But that would underestimate the meaning-making power of embodied practice and its capacity to not only produce and transmit knowledge but also generate dialogue around historical memory and practical governance. Like other partitioned peoples in Africa (Asiwaju Citation1984) and beyond (Miles Citation2014), the Masa often perceive the border with ambivalence. For many, it is yet another deplorable legacy of the colonial era that they see at the heart of historical traumas such as the erosion of their religious beliefs, the loss of their cultural heritage, and their split into Chadians and Cameroonians. As one of the key figures behind the creation of the festival explained to us,

“We had to think about how to modernize our initiation, while preserving the heritage that underlies the originality and pride of our people. Today, we live in two republics, each with its own rules. Of course, back then, there was no Chad and Cameroon. Inevitably, while forging ahead with our project, we need to take all these parameters into account” (Interview, Mounouna Foutsou, 4 May 2023).

The aim of this article is to demonstrate how the study of border festivals can complement and innovate the study of borders and borderlands. Building on participant observation, interviews, archival research, and comparative analyses, it argues that border festivals, commemorations, and enactments are worth our attention because their repertoires illuminate underrepresented knowledge production and transmission choices.Footnote1 Border festivals are not state-centric affairs; more often than not, they necessitate ground up cross-border negotiation among civil society groups with state actors. They underline processual and performative modes of engagement and management of identity and historical memory. They draw our attention to unexpected use, counter use, and repurposing of border spaces and infrastructures. Finally, the study of border festivals can reveal hidden or suppressed histories of practical governance.

The following sections will offer insight into Masa history and identity formation. In the spirit of generating conversation around how the study of border festivals can address global challenges (e.g. climate change), we will emphasize the Masa’s historical ties to the Logone River, which doubles as their most important shared resource and the increasingly vulnerable site of the “natural” border that defines Chad and Cameroon. We will then dig into the content and execution of festival iterations to analyze how invoking national identity and instrumentalizing the idea of an international border does not necessarily reify state sovereignty but does generate opportunities to engage in practical governance. On the contrary, playing Chadian or Cameroonian, in this specific case, can create margins of maneuver for a broad spectrum of border actors. Concluding remarks will clarify the cross-cultural and comparative analytic purchase of the study of border festivals. Before reviewing the historical and site-specific details of the Tokna Massana festival, we will pinpoint how border festivals theoretically complement and advance borderlands studies.

Border Festivals

Situated at the crossroads of de-centering the state and embracing the everyday-ness of borders, Chris Rumford’s appeal to “vernacularize” border studies using concepts such as “borderwork” and “seeing like a border” provides an excellent starting point for this invitation to take the study of border festivals seriously. His concept of “borderwork” emphasizes “bottom-up” activity and specifically the everyday meaning-making labor, the bordering practices, of citizens and non-citizens (Rumford Citation2006; Rumford Citation2008; Rumford Citation2013). “Seeing like a border” is premised on the idea that borders should be understood as the business of everyone, not just the business of the state. In a field where “turns,” “models,” and “directions” (Ackelson Citation2003; Brunet-Jailly Citation2004; Kolossov Citation2005; Johnson et al. Citation2011; Alvarez Citation2012; Parker and Vaughan-Williams Citation2012; Konrad Citation2015; Peña Citation2021; Heyman Citation2022; Mogiani Citation2023; Walther Citation2023) frequently churn, the vernacularization of borders has staying power because it explicitly troubles the expectation to make “the state” the protagonist—the start point and the end point—of our scholarship (Rumford Citation2013, 170).

To be sure, Rumford’s ideas have many precursors. “Borderless world” debates productively questioned the primacy of the nation-state (Yeung Citation1998; Newman Citation2006a; Diener and Hagen Citation2009; Paasi Citation2009) while scholarship underlining the processual and dynamic nature of borders argued compellingly for the need to move away from state-centric analytic models (Paasi Citation1998; Newman and Paasi Citation1998). The terms “bordering” and “bordering practices,” ushered scholarly attention toward the interactive, behind-the-scenes work that goes into border construction, maintenance, and justification (Vaughan-Williams Citation2009; Parker and Adler-Nissen Citation2012). While considerations of state practices are still (and should remain) vital to the study of borders, it is safe to say that dominant, static, top-down approaches are antiquated.

What stands out across these theorizations (and what makes them key to study of border festivals) is their inbuilt alignment with performance theory. Performance theory, most notably concepts such as “performativity” (Butler Citation1988), invites precise attention to the ways in which power is continually instantiated across various modes of knowledge production and transmission—from the written word, to embodied practice, to the built environment, to digital arenas. We can understand “performativity” as the “spatial as well as social set of repetitive practices through which socio-spatial categories or signifiers (e.g. identity, place, scale) materialize as things in the world […]” (Kaiser Citation2012, 523; see also Kaiser and Nikiforova Citation2008). Riffing on Erving Goffman’s foundational thinking about the study of culture and performance via “frame analysis” (Goffman Citation1974), Mark Salter identifies “three registers of border performativity” (e.g. formal, practical, and popular) to argue that the state has to work for its authority. It must articulate (and rearticulate) its claim to sovereignty. Most crucially, he illuminates how performance theory can be applied to the study of gender identity, borders, and sovereignty. They have one thing in common; they have no essence (Salter Citation2011, 66). Their meaning is always in the making, and it is actualized through stylized repetition. The state must continually enact its sovereignty by claiming and concentrating its resources at specific territorial coordinates, managing spectacular as well as quotidian enforcement practices, and curating public-facing narratives about their obligation to control border spaces. Reflecting on the concept of “borderwork,” Salter rightly notes that these examples of border performativity can and must be enriched with attention to the enactments staged by ordinary citizens. Indeed, paying attention to overlapping registers of performativity is the one of the hallmarks of border festival studies.

Traced to the pioneering work of performance artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña (Dell’Agmese and Amilhat Szary Citation2015, 4–5; see also Gómez-Peña Citation1999; Gómez-Peña Citation1996), the theory of “borderscapes” can help us envision how to take up that charge. The concept prioritizes attention to identifying multiple modes of knowledge production and to grappling with the “where” of the border (Brambilla, Laine, and Bocchi Citation2015). As Chiara Brambilla astutely notes, “questioning the ‘where’ of the border also involves a focus on the way in which the very location of borders is constantly dis-placed, negotiated and represented as well as the plurality of processes that cause its multiplication at different points within a society, making it visible or invisible depending on the case” (Brambilla Citation2015, 19). In other words, it is necessary but no longer sufficient to acknowledge a border’s processual qualities and to dutifully account for the work of the state and ordinary residents. We must be ready to identify and account for how bordering practices can be multi-sited and entrenched in the politics, histories, and semiotics of place.

From vitalizing how we think about governance to nuancing the way we talk about belonging, the return on investment of this “ontological reflection on borders” is significant, and particularly so in the study of border festivals. Sensitive to the temporality and eventfulness of bordering, de-bordering, and re-bordering, a borderscapes approach can reveal “the hidden and silenced borders that are made invisible by the ‘big stories’ of nation-states” (Brambilla Citation2015, 26; see also Green Citation2012, 585–587). The “big stories” of nation-states are often, and not surprisingly, state-centric in their creation and telling. The point here, however, is not to attempt to mute the state but to diversify where it is that we listen. Again, performance theory, specifically Diana Taylor’s conceptualization of the archive and the repertoire resonates here. Taylor argues that knowledge production and transmission transpires across “milieux and corporeal behaviors such as gestures, attitudes, and tones [that are] not reducible to language [and which may not always leave a physical trace]” as much as within the privileged and protected world of texts and artifacts housed in archives (Taylor Citation2003, 28). There is a parallel sensibility at work in the notion of borderscapes, which invites us to look and listen for borders in the archive, which may be populated with “big stories,” and across repertories, where meaning and claims-making transpire in equally powerful ways.

Reflecting on anthropological theories that link festive practices to “expected” moments of life transitions (Van Gennep Citation1960; Turner Citation1987), David Picard draws attention to the ways in which festivals can also play a role in mediating unanticipated crises such as “the shock of migration” and “environmental disaster”—two global challenges that shape the contemporary study of borders. He notes, “festively mediated narratives [can] suggest an overarching metaphorical framework for social life, entailing simultaneously a myth of origin, a value guide to exemplary behavior, and a story explaining the separations within the social world” (Picard Citation2016, 601 and 603). Indeed, existing studies of border festivals, traditions, commemorations, and enactments elaborate that point on a much larger scale. Methodologically diverse and ranging from festival traditions in the Senegambia and the trans-Volta (Ghana/Togo) that emphasize the “centrality of the margins” (Nugent Citation2019b), to the meticulously choreographed Wagah ceremony that transpires at the India/Pakistan border (Menon Citation2013), to cultural performances that delineate the Kashmir conflict (Aggarwal Citation2004), to the long-standing celebration of George Washington’s Birthday on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border (Peña Citation2020), to the religiously-inflected and festive revival of historical social groupings between China, Mongolia, and Russia (Billé and Humphrey Citation2021)—they have underlined how a range of actors make national and ethnic affiliation identity claims public, stage historical memory, recover from natural disasters, and even shape practical governance through stylized acts of crossing and gathering.

The “where” of the border, in these texts, often corresponds to established and/or contested boundary lines; they stay close to the “physical and highly visible lines of separation between political, social and economic spaces” (Newman Citation2006b, 144). In doing so, they evince how “space still matters” (Peña Citation2021, 768). It literally grounds cross-border festival planning but it also reveals how non-state actors can subvert dominant border narratives with their repurposing of natural and built environments (Peña Citation2017). At the same time, decisions to perform across or near physically or naturally marked borders shines light on state authority, especially as it relates to jurisdiction over and management of meeting points like an international bridge or a port of entry. But the role of the state cannot be overestimated because civil society organizations and ordinary residents often supply the year-round, cross-border coordination labor that sustains festive traditions. And while it is often the case that state actors are invited to take part in festive acts, their presence is not always solicited to reify the state but to advance ground up agendas. Official festival planning makes the coordinates of border enactments known, but it cannot circumscribe how, why, and where borderlanders may use the occasion to actualize their own socio-spatial narratives and/or advance their own political economic plans. As Paul Nugent reminds us, “festivals are of particular interest because they involve behaviour that is very conscious—even to the point of being contrived—but they also have a habit of throwing up the unexpected. Because they are an exercise in codifying collective memories, festivals can trigger a plethora of alternative constructions of reality” (Nugent Citation2019b, 485).

Origins of the Masa Festival

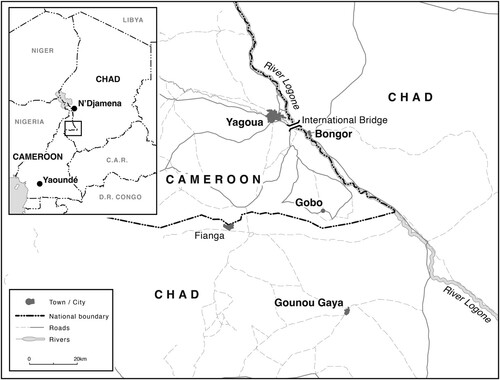

The border between Chad and Cameroon cuts through the vast lands that Masa today regard as their homeland, an ethnically diverse territory they share with various other groups []. A long section of that border is in fact a river border. The Logone River separates the two countries from Chad’s capital N’Djamena to the small village of Ham, in what is known as Cameroon’s duck’s beak, the point at which the border turns sharply westwards while southwards the river remains in Chadian territory.

Despite the paucity of the archaeological and historical record, studies have linked Masa origins to the encounter between groups migrating from the north-east to the Chari River and then to the Logone dating as far back as the sixteenth century and more recent arrivals from the south in the early eighteenth century (Seignobos Citation2005, 38). The result of these migrations and emplacements was a new pattern of settlement and livelihood that led to considerable population density. Strength in numbers meant the groups we call today Masa were better equipped to resist attacks from neighboring Muslim polities (Seignobos Citation2013). The short period of colonial domination (1904-1960) was one of pragmatic but patchy territorial control. The current host sites of the Tokna Massana festival were in fact newly created as colonial administrative posts, Bongor in 1904 and Yagoua in 1924. Colonial dynamics also increased cross-border movement in response to differing administrative, tax, and agricultural policies on either side of the newly established border (Pahimi Citation2012). Masa only came to be a widespread term to designate a distinctive ethnic group through its usage by the French colonial administration after World War One (Melis Citation2019, 52–76). The colonial legacy also proved enduring in the creation of cantons (administrative units) conceived to reflect the majority ethnic makeup of each territory. Newly designated chiefs were placed at the head of each canton and remain significant actors in Masa society across the Logone River as well as festival organization.

The middle course of the Logone has remained a consistent reference point for people who identify as Masa. It serves as an international boundary line and yet it is anything but fixed. In fact, old timers like to point out that the riverbanks south of today’s Yagoua-Bongor border posts have gradually moved well inside what used to be Chadian territory in the last century, as shown by the colonial-era beacons. Noting the position of border markers past and present animates historical reflexivity. While quotidian conversations invoke the Logone as an agential border actor, marked occasions like the Tokna Massana festival use the river as a stage to remember and celebrate Masa history. As scholars have noted elsewhere, these quotidian and spectacular exercises can also lead to a wider recognition and affirmation of Masa epistemologies that “contradict” the histories and legacies of colonial domination (García Peña Citation2016).

Masa collective memory remains deeply linked to the Logone even as cyclical changes in the natural and built environment significantly alter its contours and characteristics. In the Logone Valley, the rainy season causes a significant rise in the river’s water levels, flooding vast expanses of adjacent fields from July to October. Ethnographic studies have highlighted how these flooding patterns made singularly diverse livelihoods that combined fishing, cultivation, and livestock herding possible (Garine Citation1964; Dumas-Champion Citation1983, 115). Seasonal dynamics, which are becoming more erratic with climate change, dictate border crossing patterns—determining the duration of crossing activities and modes of transportation. When the rainy season subsides and the river is at its narrowest (December to May), the 600 m separating the two official border posts can be swiftly traversed either by pirogue (canoe) or the ferry, which has the advantage of allowing for the crossing of vehicles. Chadian authorities brought the ferry to Bongor from N’Djamena (Chad’s capital) in the mid-1980s, once the construction of a new international bridge linking N’Djamena to its “twin town”—Kousseri, Cameroon—was completed (Soi and Nugent Citation2017). Operated by a private contractor from Bongor, the ferry is only in service during the dry season. Moreover, it has suffered from long spells of inactivity over the years due to mechanical breakdowns, which makes pirogues the only viable border crossing option for much of the year. For the partitioned communities in the Yagoua-Bongor area, frequently crossing the river with locally owned pirogues and small boats outside of official crossing points (e.g. state authorized) is still a daily reclamation of their distinct collective rights (Marco Bertone, personal communication).

Indeed, those small scale, quotidian exercises sustained links among Masa during periods when convening en masse and publicly celebrating ethnic identity were vehemently discouraged by government authorities. Mounouna Foutsou, the first president of Tokna’s organizing committee, and later a long-serving minister in the Cameroon government, recalled how it was “the winds of freedom [blowing] during the democratization of the 1990s” that created the conditions for the celebration of a large festival of Masa arts and culture (Interview, 4 May 2023). At the outset of that decade, an increasingly troubled political and economic environment pushed Cameroon’s ruling party to pass laws on the freedom of the press and the media and on the freedom of association. It marked a break with the restrictive 1967 Freedom of Association Act., which was a cornerstone of the one-party system that had taken hold soon after Cameroon’s independence. Whereas in the past government-appointed préfets (district officers) had to authorize new associations, now an association could acquire legal existence by simply depositing its by-laws with the district authorities. This new dispensation resulted in a proliferation of associations, many of which were based on ethnic identity. Such kind of groupings were unthinkable in previous decades under a regime for which national unity was paramount and “tribalism” was anathema. In Chad, the advent of multi-party politics also took place in those same years and, as in Cameroon, the importance of local constituency building was facilitated by the new-found legitimacy accorded to ethnically based associations. In this new political scenario, the idea of a great festival open to all Masa on both sides of the border thus began to take shape.

Mounouna Foutsou was one of several Masa youngsters whose university studies had taken them abroad and were back in Cameroon starting their professional lives in the country’s main cities around that period. In the capital Yaoundé, a critical mass of civil servants, professionals, and students, some of them Chadian, coalesced around a new Masa Cultural Group that held weekly soirées but also organized larger events such as the Journées Culturelles Masa, which regularly attracted participants from other centers of Masa migration in southern Cameroon. By the late 1990s, there was a growing sense of urgency among these Masa urbanites about the need to reconnect with their homeland, where they saw key social institutions for cultural reproduction on the verge of disappearing. Christian Seignobos’s analysis of this period pinpoints how dynamics at the border could reverberate well within the boundaries of Cameroon and Chad. He notes, “On the road to progress, these groups want to ‘learn from themselves,’ in other words, to know their history and have it recognized. Asserting themselves through the past is the obvious meaning of the flourishing of clan associations and ethnic cultural festivals that began on the banks of the Logone in the mid-1990s” (Seignobos Citation2013, 99). The opening paragraph of the first festival’s newsletter pithily conveyed the stakes of publicly associating and organizing around ethnic identity: “We received our culture from our parents so that we could pass it on to our children. It's a duty we cannot shirk, or else we will end up in the dustbin of history” (Tokna Citation2003a, 3). The underlying goal of festival organization was to institutionalize communication between the homeland (on both sides of the Logone River) and the diaspora (that is, those living in Yaoundé, in N’Djamena, or in other centers of Masa migration).

It is important to note that Tokna Massana was not an isolated phenomenon. Other ethnic groups living along the Chad-Cameroon border also responded in similar fashion to the advent of multi-party politics. Anthropologist Clare Ignatowski conducted fieldwork among the Tupuri—a neighboring ethnic group with close historical ties to the Masa—during this transition period in which ethnic constituencies had become prized electoral targets. She noted how in a context “where parochialism has become a political strategy, local cultural-political configurations continue to be prisms through which people consider large-scale challenges such as democratization” (Ignatowski Citation2004, 280, Citation2006). Seizing the moment, the Musgum, the Kotoko, the Musey, the Mundang, and the Tupuri launched their own festivals at around the same time with varying degrees of success (Abba Ousman Citation2019; Kalbé Yamo Citation2019). In several cases, persistent inter-ethnic tensions and longer histories of violence were at the root of those efforts. Such was the case of the first Sao-Kotoko festival, which was held in Kousseri in 2003 and came to fruition because an earlier event organized by Arab Choa political leaders was perceived to belittle the significance of Kotoko culture and history (Barka and Barka Citation2013). Yet, inter-ethnic group relations and festival organization are not necessarily wed to conflict. Prominent Musey figures, for example, launched their own festival Kodomma while sustaining a parallel involvement in Tokna Massana. Through these collaborations, the Masa festival has distinguished itself from other festivals by its regularity, by the alternation of its two locations across the border, and by the size of participating crowds.

The Tokna Massana project only gained cross-border traction with labor-intensive, multi-sited preparation. In 2002, a series of meetings were held in Ngaoundéré (Cameroon) in October—where delegations from Yaounde and Yagoua found a common ground and agreed to go ahead with the festival, in Kousseri (Cameroon) in November—where a broader circle of Masa from N’Djamena (Chad) bought into the project, and in Bongor (Chad) in December—where the strength of popular support for the festival first became apparent and financial support began to materialize (Tokna Citation2003d, 19). Significant opposition to the initiative put additional pressure on those proceedings (Tokna Citation2003e, 20) An old guard of prominent Masa men led by the then Littoral province’s governor had tried to block the organization of the event and even Yagoua’s laamido (customary chief) had been unsupportive (Interview, Tokna’s former vice-president, 5 May 2023). As the dates approached, some non-Masa leaders in the Yagoua district lobbied against the festival and the préfet only gave the green light to proceed at the last minute—the festival association’s bylaws were only submitted three days before the event (Interview, Tokna’s former secretary general, 25 April 2023). In the end, Yagoua could host the first edition of the festival from 19 to 22 March 2003. On the last day, a general assembly formally approved the name of the festival and the principle of alternation between Yagoua and Bongor as host towns (Association Tokna Massana. Citation2003, 49). It was also decided to make the festival a biannual event, a pattern that has been disrupted on a few occasions and most significantly after the fifth edition in 2013 when deterioration of the security situation caused by the Boko Haram insurgency led to a four-year hiatus. The Corona-19 (Covid-19) epidemic and subsequent border closures also interrupted the proceedings. Bongor, for example, was scheduled to host the celebration in 2021 but their duties got pushed to 2022. Those suspensions notwithstanding, Tokna has typically taken place during the dry season, when crossing the border is logistically easier, and around the Easter holiday, which facilitates the participation of salaried workers and school children as well as Masa living in the diaspora (Tokna Citation2003b, 4).

Tokna Massana’s Repertoire, Coordination, and Practical Governance

While festival organization is primarily non-governmental in its origins, year-to-year planning necessarily involves conferring with state authorities. The study of border festivals, thus, provides a unique perspective on how state and society are inextricably linked, which makes the choice of “seeing like a state” or “seeing like a border” a moot point. Instead, border festival organizational dynamics, structural particularities, and cultural imperatives keep those two ways of seeing in productive tension.

Indeed, local figures like mayors, district officers and governors, alongside national figures like ministers or other senior central government officials have always been well represented because they are uniquely positioned to provide necessary resources and facilitate mobility and access to public spaces. Security forces provided by the host country, for example, are instrumental in ensuring public order during the event. They are also tasked with protecting the guest country’s official delegation throughout the entirety of their participation—from the official welcome enactment/reception at the border post, to various festival locations, to the return trip. Providing a security detail at the border reminds us how, in addition to lending an extra layer of formality and “spectacle” to the proceedings, that bordering practice reaffirms the nation-state's sovereign right to determine who is allowed in and the ease with which they do so (De Genova Citation2013). Host and visiting government authorities have occupied a place of choice in what can be protocol-heavy proceedings, particularly during the festival’s opening and closing ceremonies. The two countries’ border posts become the stage where the country hosting the festival officially welcomes their ethnic siblings on the other side. This moment, which has been marked by organizers with varying intensity, is one of many ways in which the festival thematizes the river and its border infrastructure.

Private commercial sponsors (i.e. breweries, telecom and sports betting companies) and to a lesser extent the sale of official pagnes (cloths specially printed for the occasion) are key elements in the festival’s budget. In addition to this, the bread and butter of each edition’s financial resources are the contributions from members of the festival associations on each side of the border, including those of prominent Masa figures who are thus invited to show their generosity through more robust cash gifts framed as gestes (literally gestures). Yet, state authorities and institutions have also supported the celebration financially. The first edition, for example, received financial support from Cameroon’s President Paul Biya and national parastatal companies (Association Tokna Massana Citation2003, 3–5). In the last edition to date, President Biya once more pledged to cover a third of the festival’s budget, but the actual disbursement of those funds had yet to transpire six months after the event. National public television is also a key factor in the festival's success, as both CRTV and Tele-Tchad have provided ample coverage and funds. However, state authorities can also be a drain on festival resources, and this is not only because of the expenses involved in hosting them. Indeed, in a practice particularly prevalent in Cameroon (Ahamat Citation2021), district officers and governors condition their presence in public events to the payment of substantial fees euphemistically referred to as le prix du carburant (money for gas).

For politicians wanting to raise their profile or embarking into electoral contests, the festival can offer an appealing platform but the political instrumentalization of these festivals cuts both ways, as the festival can easily become open season for constituents’ grievances and demands. The fifth edition of Tokna Massana was devoted to the theme “Water management for sustainable development in the Logone Valley” after catastrophic flooding in August and September 2012 led to the forced displacement of thousands of people on both sides of the border. Focusing on water management during the festival led to resolutions on the promotion of improved hydraulique villagoise (water systems at the village level) and provided a public platform to expose the lack of transboundary coordination and local input into the two states’ new engineering projects for flood prevention (Labara Tokna Citation2013, 12; Laborde, Mahamat, and Moritz Citation2018; Sambo Citation2016).

State-society dynamics are also central to the process of identity formation and consolidation that Tokna has advanced. Two social institutions deserve a special mention in this regard, as they have cast a long shadow on the festival repertoire. They are the guruna, which refers to both the institution and the participants in male fattening periods, and the labana, which is the male initiation shared by Masa and other neighboring groups. Even though there is no longer a place for the sociality around cattle camps on which guruna was premised and decades had gone by without new initiations, both guruna and labana have made themselves present in Tokna through the distinctive outfits, props, dances, and songs of the various groups of guruna and initiates taking part. These public-facing traces of traditional initiation rites are reoccurring and performative—they assert the autonomy of Masa society and culture. Indeed, guruna and labana provided two platforms for cultural transmission that were not dependent on modern education as conceived by colonial and postcolonial political and religious authorities.

Guruna involved seasonal collective herding of cattle in bush camps. These camps were privileged places for the articulation of the masculine ideal in Masa society through a diet rich in milk and millet, the learning of dances and songs, and the practice of wrestling. Guruna guaranteed both the physical conditioning in preparation for marriage and the abundance of livestock on which the marriage dowry is based (Dumas-Champion Citation1983, 115–60). From the start, Tokna identified guruna as “a school for the learning of Masa culture and life” and lamented its gradual disappearance because of the spread of urban lifestyles and modern schooling (Association Tokna Massana Citation2003, 22). The outlook, however, was optimistic, as the guruna songs and dances had shown a remarkable “plasticity” throughout the 1990s when “transported to modern institutions and urban settings” (Ignatowski Citation2006, 21). Tokna’s first edition proposed strategies to consolidate the revival of guruna performances (Association Tokna Massana Citation2003, 22) that have proved with time effective.

The labana had become a contested custom already in the colonial era under the influence of Christian missionaries but it was after independence when its practice ended. In Cameroon, it had been repressed and formally banned in 1968 by a district officer’s ordinance in the aftermath of initiations held against the opposition of government authorities and certain Muslim and Christian leaders. In Chad, the last initiations had taken place in 1975, enabled by the brief period during which President Tombalbaye’s authenticity policies were in place. Tokna’s first newsletter singled labana out as “the most important … of all the rites that our ancestors have bequeathed to us” and defended its enduring bien-fondé (validity) in the face of all the questioning it had been subject to (Tokna Citation2003c, 14). In subsequent editions, Tokna served as a platform to advocate for the resumption of labana, which finally took place before the festival’s 2009 edition and again in 2010. Although these initiations were shorter and featured other adaptations to make them compatible with the demands of schooling and professional life, they were nonetheless marked by controversy, disappearances, and outbursts from the new initiates as they reintegrated into society (Dumas-Champion Citation2015). This led Tokna organizers to accept the suspension of the labana. In the run-up to the 2023 edition of the festival, however, a new cycle of short initiations on the Cameroonian side of the border preceded the festival once more.

Planning and exhibiting a coherent festival repertoire, consistently promoting cultural value, continuity, resilience, and unity across staging locations in Yagoua or in Bongor, has provided the basis for a newly confident Masa identity. The assertion of the unity of all Masa, despite their separation into two nationalities, has indeed been a foundational mantra. Unity is also a frequent emphasis in a whole series of songs composed specifically for the festival, including the festival anthem.Footnote2 The anthem was commissioned in the run-up to Tokna’s first edition, and it is performed at every festival. It was composed by Uni Madura, a lycée teacher who has had a successful parallel career as singer and musician. While anxieties about disunity pervade the festival, conflict and factionalism often surface in festival events, whether it is around the organization of the dance performances, or in the public debates during the Etats Généraux de la Culture Massa (Forum for the Masa Culture), or during the two festival associations’ assemblies. Stakeholders ask: How do we manage conflict? How can we showcase unity in service of tangible achievements? These vital questions constantly haunt festival promoters, as was put most compellingly by Jean-Pierre Ningaïna, a Catholic priest and intellectual of national stature in Chad. In a keynote speech he was invited to give for the 2017 edition in Bongor, which soon became a social media sensation, he wondered: “All of us gathered here give the impression of eagerly calling for this unity [among Masa], and the idea of the Tokna is a sign of this, but is the effectiveness of this project visible in the social and political field?” He then went on to urge participants to work towards the creation of “a kind of festival of the political arts” (Ningaïna Citation2017).

The celebration has engendered noteworthy social and political advances, some examples of which involve calling out state authorities, as noted above during the fifth edition of the festival. Other examples, however, involve working around those authorities. A recent, major infrastructural development is the construction of a new international bridge over the Logone between Yagoua and Bongor, which began in 2020 and is scheduled to be commissioned in July 2024. The bridge is expected to change cross-border transport in the area drastically, but its transformation of the space around the border posts has already begun. In the months preceding Tokna 2022, for example, bridge works slowed down by yet another breakdown of the ferry and, while it was being repaired, the contractor decided to build a temporary dike with empty containers reinforced with sandbags. Although the mini-pont (mini-bridge), as the dike was nicknamed by Yagoua and Bongor residents alike, was meant to allow the passage of project vehicles only, the festival organizers were quick to seize the possibilities this new means of passage afforded.

An official request was addressed to Razel Fayat, the French construction multinational building the bridge, to open the dike for public passage during the festival []. The laamido (customary chief) of Yagoua, an authority whose legitimacy had been acknowledged by the company since the start of construction works, was the chosen channel to make the request. As the Razel manager explained to participants in a project worksite meeting we attended just after the festival, “I let the festivalgoers cross the day before yesterday. It was a large convoy, the minister [Mounouna Foutsou] included. I've made a commitment with the laamido that I'll let people pass through for twenty-five days but the risk is that people get used to it. This cannot become a public passageway. Otherwise, we will have problems, even with the piroguiers (boatsmen)”. In the end, once the agreed period had elapsed, the company managed to restrict usage of the dike, which was washed away three months later when the river waters rose. This example is one of many that evidences how the festival serves as a platform for the attainment of compelling local demands.

Border Festivals: Comparative and Cross-Cultural Potential

This essay has demonstrated that there are epistemological gains to be made from the study of border festivals. Border festivals generate multi-sited and multivalent listening opportunities, which makes their omission within contemporary conversations in our field more puzzling. In dialogue with recent calls to “address processes of mutual recognition that occur at borders,” (Heyman Citation2022, 3), we have highlighted how cross-border festival planning and implementation facilitates embodied communication—eye-to-eye, hand-to-hand, and shoulder-to-shoulder acts of knowledge production and transmission that cut across what the map cuts up (Certeau Citation1984, 129). Performance theorist Dwight Conquergood’s reading of de Certeau’s aphorism clarifies the stakes of evaluating multiple modes of knowledge production. Conquergood writes, “[de Certeau] points to transgressive travel between two different domains of knowledge: one official, objective, and abstract—‘the map’; the other one practical, embodied, and popular—‘the story.’” (Conquergood Citation2002, 145–146). Border festivals do not oscillate cleanly between the “official” and the “popular.” Neither are they seamless performances. Attending to those tensions can present our biggest learning challenges and opportunities.

Indeed, the first day of festival programming and the highly anticipated Chad v. Cameroon wrestling match mentioned at the outset of this discussion did not unfold without a hitch. The problem was that the Cameroonian delegation of male wrestlers had not yet crossed the border and their arrival time was still to be determined. Observers that day, including a significant media presence, were treated instead to Chadian wrestlers sparring against each other. This schedule modification did not go unnoticed, and many festivalgoers began to speculate about the reasons for the Cameroonians’ failure to show up.

Cameroonian and Chadian male wrestlers did manage to face off against each other in the main festival grounds during the final day of programming. This meant that they enjoyed a much larger audience, which also included high-profile personalities and elite Masa living in the diaspora who had only then made it to the festival. As one of the local radio staff covering the event explained to us, “the wrestlers have imposed their own program.” The festivities may have gotten off to a less than ideal start that year and Chadian wrestlers may have crushed their Cameroonian brethren-athletes making for an anti-climactic competition finale, but all was well. The “expectation of ritual” (Peña Citation2020, 8–9) would ensure that both teams would showcase their skills once more at the next Tokna Massana festival scheduled to take place in Yagoua. Indeed, managing to meet and commune despite logistical difficulties and protocol missteps alerts us to the exacting planning and preparation that goes into realizing these cross-border endeavors. Taking the labor that brings border festivals to fruition seriously as an object of study opens dynamic pathways for research that illuminate multi-sited and sensorial modes of knowledge transmission as well as the inconspicuous ways in which festive coordination can occasion practical governance.

The study of border festivals draws critical attention to the work of ordinary citizens to reconfigure asymmetrical relations and long-instilled hierarchies generated by political boundary lines. To be clear, border festivals are designed to convey symmetry but do not promise harmony; they do not confer long-lasting equilibrium, they rehearse the prospect of it. And it is that very characteristic that makes their cross-cultural and comparative study not only viable but also generative. Around the globe, borderlanders strive to find ways to stay in contact, to remember together, and to solve shared problems. Studying border festivals, locating potential cross-border cooperation strategies and tactics along a wider spectrum of social actors and spaces, is both timely and necessary considering climate change, the mass displacement of vulnerable populations, and many other pressing global challenges.

Acknowledgements

The British Academy generously extended our project until the end of 2023 to offset the challenges brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic. We would like to thank our border festivals' project colleagues Prof. Paul Nugent, Dr. Isabella Soi, Prof. Samuel Ntewusu, Dr. Edem Adotey, and, most especially, Dr. Antonino Melis. The Logone Valley's Cultural Center and Museum in Yagoua made available to us their unique collection of archival materials, books and audiovisual media. We are also grateful for the intellectual encouragement and practical support we received from Dr. Ousmanou Virina, Marco Bertoni, Daniel Koukna and Dieudonné Bakonou.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Research involved trips to Chad and Cameroon in April 2022, April-May 2023, and October-November 2023. We took part in festival events on both sides of the border, conducted more than thirty semi-structured interviews and benefited from numerous informal conversations with festival organizers and participants in Bongor, Yagoua, Maroua, N’Djamena, and Yaoundé. We also draw on the archives of the Logone Valley’s Cultural Center and Museum (https://www.valleedulogone.com).

2 Consider the following anthem’s excerpts “Masa people, black people, brave men / Strong men, let's love each other / Unite our thoughts, Masa people / Rise up, the rallying song has begun (…) We are the children of one man and the family of one man / Let us be united by the same love and the same thought / Let us have the same dream and the same strength / Rise up, it's time (…) Neither discord nor the Church will separate us / Neither Islam nor politics will separate us / We have already known that we are a great people / Rise up, it's day … ” (translation from Masa courtesy of Dr. Ousmanou Virina).

References

- Abba Ousman, Mahamat. 2019. Cultures, échanges transfrontaliers et nouvelle perception de la fronitière dans la vallée du Logone [Cultures, cross-border exchanges and new perceptions of the border in the Logone valley]. Rhumsiki 14: 143–61.

- Ackelson, J. 2003. Directions in Border Security Research. The Social Science Journal 40: 573–81.

- Aggarwal, R. 2004. Beyond Lines of Control: Performance and Politics on the Disputed Borders of Ladakh, India. Durham: Duke UP.

- Ahamat, Abakar. 2021. Le Fameux “Article 2" [The Famous "Article 2"]. Yaoundé: Editions de Midi.

- Alvarez, R. 2012. Borders and Bridges: Exploring a New Conceptual Architecture for (U.S.-Mexico) Border Studies. The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 17, no. 1: 24–40.

- Asiwaju, Anthony. 1984. Partitioned Africans: Ethnic Relations Across Africa’s International Boundaries 1884–1984. Lagos: University of Lagos Press.

- Association Tokna Massana. 2003. Festival Massa des Arts et de la Culture 2003: Rapport Général [Masa Festival of Arts and Culture 2003: General Report]. Yagoua: Association Tokna Massana.

- Barka, Bana, and Harouna Barka. 2013. Festivals au Cameroun: Enjeux identitaires et politiques de Festik (2000) and Festat (2000) [Festivals in Cameroon: Identity and Political Stakes of Festik (2000) and Festat (2000)]. In Une histoire des festivals: XXe-XXIe siècle [A History of Festivals: Twentieth and Twenty-first Centuries], ed. A. Fléchet, 185–99. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne.

- Billé, F., and C. Humphrey. 2021. On the Edge: Life Along the Russia-China Border. Cambridge: Harvard UP.

- Brambilla, C. 2007. Borders and Identities/Border Identities: The Angola-Namibia Border and the Plurivocality of the Kwanyama Identity. Journal of Borderlands Studies 22, no. 2: 21–38.

- Brambilla, C. 2015. Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscapes Concept. Geopolitics 20, no. 1: 14–34.

- Brambilla, C., J. Laine, and G. Bocchi. 2015. Borderscaping: Imaginations and Practices of Border Making. New York: Routledge.

- Brunet-Jailly, E. 2004. Toward a Model of Border Studies: What Do We Learn from the Study of the Canadian-American Border? Journal of Borderlands Studies 19, no. 1: 1–12.

- Butler, J. 1988. Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory. Theatre Journal 40, no. 4: 519–31.

- Certeau, de. M. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. by S. Rendall. Berkeley: U California P.

- Conquergood, D. 2002. Performance Studies: Interventions and Radical Research. The Drama Review 46, no. 2: 145–56.

- De Genova, N. 2013. Spectacles of Migrant ‘Illegality’: the Scene of Exclusion, the Obscene of Inclusion. Ethnic and Racial Studies 36, no. 7: 1180–98.

- Dell’Agmese, E., and A. Amilhat Szary. 2015. Borderscapes: From Border Landscapes to Border Aesthetics. Geopolitics 20, no. 1: 4–13.

- Diener, A.C., and J. Hagen. 2009. Theorizing Borders in a “Borderless World”: Globalization, Territory and Identity. Geography Compass 3: 1196–216.

- Dumas-Champion, F. 1983. Les Masa du Tchad: bétail et société [The Masa of Chad: Livestock and Society]. Paris: Maison des Sciences de l’Homme.

- Dumas-Champion, F. 2015. À propos de l’initiation Masa [About Masa Initiation]. Journal des Africanistes 85, no. 1–2: 258–80.

- Flynn, Donna. 1997. We are the Border: Identity, Exchange, and the State along the Benin-Nigeria Border. American Ethnologist 24, no. 2: 311–30.

- García Peña, L. 2016. The borders of dominicanidad: Race, nation, and archives of contradiction. Durham: Duke UP.

- Garine, I. de. 1964. Les Massa du Cameroun [The Masa of Cameroon]. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Goffman, E. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge: Harvard UP.

- Gómez-Peña, G. 1996. The New World Border: Prophecies, Poems, and Loqueras for the End of the Century. San Francisco: City Lights.

- Gómez-Peña, G. dir., 1999. Borderscape 2000: Kitsch, Violence, and Shamanism at the End of the Century. San Francisco: Magic Theater. Video.

- Green, S. 2012. A sense of Border. In A Companion to Border Studies, eds. T.M. Wilson, and H. Donnan, 573–92. London: Blackwell.

- Haman, A. 1996. Les Massa de la rive gauche du Logone (Nord-Cameroun). Masters thesis in History, University of Yaounde I.

- Heyman, J. 2022. Rethinking Borders. Journal of Borderland Studies, doi:10.1080/08865655.2022.2151034.

- Ignatowski, C. 2004. Multipartyism and Nostalgia for the Unified Past: Discourses of Democracy in a Dance Association in Cameroon. Cultural Anthropology 19, no. 2: 276–98.

- Ignatowski, C. 2006. Journey of Song: Public Life and Morality in Cameroon. Bloomington: Indiana UP.

- Johnson, C., R. Jones, A. Paasi, L. Amoore, A. Mountz, M. Salter, and C. Rumford. 2011. Interventions on Rethinking “The Border” in Border Studies. Political Geography 30: 61–9.

- Kaiser, R. 2012. Performativity and the Eventfulness of Bordering Practices. In A Companion to Border Studies, eds. T.M. Wilson, and H. Donnan, 522–37. London: Blackwell.

- Kaiser, R., and E. Nikiforova. 2008. The Performativity of Scale: The Social Construction of Scale Effects in Narva, Estonia. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26: 527–62.

- Kalbé Yamo, Théophile. 2019. Festivals culturels et survie de la littérature orale dans le bassin du lac Tchad [Cultural Festivals and the Survival of Oral Literature in the Lake Chad Basin]. Rhumsiki 7: 47–65.

- Kolossov, V. 2005. Border Studies: Changing Perspectives and Theoretical Approaches. Geopolitics 10, no. 4: 606–32.

- Konrad, V. 2015. Toward a Theory of Borders in Motion. Journal of Borderlands Studies 30, no. 1: 1–18.

- Labara Tokna. 2013. “Inondations: Comment profiter au mieux du trop plein d’eau?” [Flooding: How to make the most of the excess water?].

- Laborde, Sarah, Aboubakar Mahamat, and Mark Moritz. 2018. The Interplay of Top-Down Planning and Adaptive Self-Organization in an African floodplain. Human Ecology 46, no. 2: 171–82.

- Melis, A. 2019. Storia e identità linguistica [History and Linguistic Identity]. In Tessiture dell‘Identità: lingua, cultura et territorio dei Gizey tra Camerun e Ciad [Weaving Identify: Gizey Language, Culture and Territory between Cameroon and Chad], ed. L. Gaffuri, A. Melis and V. Petrarca, 43–104. Napoli: Liguori.

- Menon, J. 2013. Performance of nationalism: India, Pakistan, and the memory of partition. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Miles, W. 2014. Scars of partition: Postcolonial legacies in French and British borderlands. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Mogiani, M. 2023. Studying Borders from the Border: Reflections on the Concept of Borders as Meeting Points. Geopolitics 28, no. 3: 1323–41.

- Newman, D. 2006a. Borders and Bordering: Towards and Interdisciplinary Dialogue. European Journal of Social Theory 9, no. 2: 171–86.

- Newman, D. 2006b. The Lines that Continue to Separate Us: Borders in a “Borderless” World. Progress in Human Geography 30, no. 2: 143–61.

- Newman, D., and A. Paasi. 1998. Fences and Neighbours in the Postmodern World: Boundary Narratives in Political Geography. Progress in Human Geography 22, no. 2: 186–207.

- Ningaïna, J.-P. 2017. Leçon inaugurale du Tokna Massana 2017, Bongor, 8 April 2017 (courtesy of Marco Bertoni, personal copy).

- Nugent, Paul. 2002. Smugglers, Secessionists and Loyal Citizens on the Ghana-Togo Frontier: The life of the borderlands since 1994. Oxford: James Currey.

- Nugent, Paul. 2019a. Border Studies Temporality, Space, and Scale. In The Routledge Handbook of Transregional Studies, ed. Matthias Middell, 179–87. New York: Routledge.

- Nugent, P. 2019b. Boundaries, Communities, and State-Making in West Africa: The Centrality of the Margins. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Paasi, A. 1998. Boundaries as Social Processes: Territoriality in the World of Flows. Geopolitics 3, no. 1: 69–88.

- Paasi, A. 2009. Bounded Spaces in a “Borderless World”: Border Studies, Power and the Anatomy of Territory. Journal of Power 2, no. 2: 213–34.

- Pahimi, Patrice. 2012. Taxation and the Dynamics of Cross-Border Migration between Cameroon, Chad and Nigeria in the Colonial and Postcolonial Period. In Crossing African Border: Migration and Mobility, eds. C. Udelsman Rodrigues, and J. Tomas, 83–97. Lisbon: Centro de Estudos Internacionais.

- Parker, N., and R. Adler-Nissen. 2012. Picking and Choosing the “Soveriegn” Border: A Theory of Changing State Bordering Practices. Geopolitics 17, no. 4: 773–96.

- Parker, N., and N. Vaughan-Williams. 2012. Introduction, Critical Border Studies: Broadening and Deepening the “Lines in the Sand” Agenda. Geopolitics 17, no. 4: 727–33.

- Peña, E.A. 2017. Paso Libre: Border Enactment, Infrastructure, and Crisis Resolution at the Port of Laredo 1954-1957. The Drama Review 61, no. 2: 11–13.

- Peña, E.A. 2020. ¡Viva George! Celebrating Washington’s birthday at the U.S.-Mexico border. Austin: U Texas P.

- Peña, S. 2021. From Territoriality to Borderscapes: The Conceptualisation of Space in Border Studies. Geopolitics 28, no. 2: 766–94.

- Picard, D. 2016. The festive frame: Festivals as mediators for social change. Ethnos 81, no. 4: 600–16.

- Rumford, C. 2006. Theorizing Borders. European Journal of Social Theory 9, no. 2: 155–69.

- Rumford, C. 2008. Introduction: Citizens and Borderwork in Europe. Space and Polity 12, no. 1: 1–12.

- Rumford, C. 2013. Towards a Vernacularized Border Studies: The Case of Citizen Borderwork. Journal of Borderlands Studies 28, no. 2: 169–80.

- Salter, M.B. 2011. Places Everyone: Performativity and Border Studies. Political Geography 30, no. 2: 66–7.

- Sambo, A. 2020. Aménagements hydrauliques sur le Fleuve Logone : le Tchad et le Cameroun entre coopération et confrontation (1970- 2012) [Water Works Planning on the Logone River: Chad and Cameroon between Cooperation and Confrontation (1970- 2012)]. Annales de la FALSH de l’Université de Ngaoundéré 15, no. special issue: 247–265.

- Seignobos, C. 2005. Mise en place du peuplement et répartition ethnique [Settlement and Ethnic Distribution]. In Atlas de la Province Extrême-Nord Cameroun [Atlas of Cameroon Far North Province], eds. C. Seignobos, and O. Iyebi-Mandjek, 44–51. Marseille: IRD.

- Seignobos, C. 2013. La difficile écriture de l’histoire: l’exemple des Muzuk et des Masa du Cameroun. In Les ruses de l'historien, ed. F.-X. Fauvelle-Aymar, 97–117. Paris: Karthala.

- Smith, S., N.W. Swanson, and B. Gökariksel. 2016. Territory, Bodies and Borders. Area 48, no. 3: 258–61.

- Soi, I., and P. Nugent. 2017. Peripheral Urbanism in Africa: Border Towns and Twin Towns in Africa. Journal of Borderlands Studies 32, no. 4: 535–56.

- Taylor, D. 2003. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham: Duke UP.

- Tokna. 2003a. “Avant Propos” [Foreword].

- Tokna. 2003b. “Editorial”.

- Tokna. 2003c. “Labana ou l’initiation” [Labana or Initiation].

- Tokna. 2003d. “La marche vers le Festival des Arts et de la Culture Massa” [The Road towards the Masa Festival of Arts and Culture].

- Tokna. 2003e. “Qui a peur du festival?” [Who is Afraid of the Festival?].

- Turner, V. 1987. Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage. In Betwixt and Between: Patterns of Masculine and Feminine Initiation, eds. Louise Carus Mahdi, Steven Foster, and Meredith Little, 5–22. Chicago, IL: Open Court.

- Van Gennep, A. 1960. The Rites of Passage. Chicago, IL: U Chicago P.

- Vaughan-Williams, N. 2009. Border Politics: The Limits of Sovereign Power. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP.

- Walther, O., et al. 2023. Border Studies at 45. Political Geography 104, no. June: 102909.

- Yeung, H.W. 1998. Capital, State and Space: Contesting the Borderless World. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 23, no. 3: 291–309.