ABSTRACT

This paper presents findings from a qualitative case study of staff participating in the reflective practices and processes available at an English children’s home and specialist school. Researchers conducted a thematic analysis of 18 semi-structured interviews, 2 focus groups and 16 journal-based training assignments. Key themes identified in the data are outlined and a composite vignette conveys the lived experience of participating in the organization’s reflective practice provision. Staff highlight the personal intensity of their ongoing reflective work, which is “like therapy but not therapy,” and the challenges and benefits of learning to use and contribute to a reflective milieu. The concluding discussion widens findings by Heine Steinkopf and colleagues concerning the need for a regulating working environment and trustworthy theoretical model and suggests that “epistemic trust” in an organizational culture is key to effective teamwork and personal growth in role.

Practice implications

Qualitative research in the children’s residential care and education sector is important in reporting on the lived experience of staff and the ongoing reflective support they find most useful

Experiential reflective spaces can support children’s residential care and education staff to understand and learn from the emotional dynamics of trauma and its personal and bidirectional effects

As well as providing a trusted theoretical model for reflection and a regulating work environment, organisations need to support individual staff to build ‘epistemic trust’ in the provision offered

At its best a reflective organisational culture is an organic resource that staff take collective responsibility for maintaining and improving

A ‘critical mass’ of staff may be needed to sustain an organisational culture of reflection

Introduction

This article reports on a qualitative study at an English children’s home and specialist school, the Mulberry Bush, researching the training experiences of care and education practitioners working in teams with children who are placed out-of-home.Footnote1 The residential care and education workforce is on the front line of providing for some of the UK’s most disadvantaged children, who have experienced psychosocial adversity, maltreatment and ensuing mental health difficulties (Bywaters et. al., 2018; Keyes et al., Citation2012). At the Mulberry Bush, most of the children are vulnerable to some, or all, of the effects of multiple adverse childhood experiences and complex trauma, affecting their emotion regulation, self-identity and relational capacities (Cloitre, Citation2020). A recent longitudinal study of children who had experienced complex trauma and who were placed in out-of-home care in England found that struggles with these areas of functioning were hard to change. The children habitually made negative self-appraisals (“I’m a failure;” I can’t trust anyone’), suppressed difficult thoughts as an adaptive coping mechanism and experienced disturbances in memory, creating a feeling of continuously being under threat (Hiller et al., Citation2021, p. 49). In residential settings, developing the children’s relational capacities is crucial because relationships are a key means through which emotion regulation and self-identity can themselves be developed and changed, but the work of making and sustaining the relationships needed to effect these changes can be very challenging for both children and staff (Jenney, Citation2020). Whilst out-of-home and care experienced children and young people value trusting, supportive relationships very highly (Briheim-Crookall et al., Citation2020), burnout, compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma can be very real risks when supporting them (Seti, Citation2008).

At the Mulberry Bush, in common with other UK residential settings taking a milieu-based approach to therapeutic care, staff are asked to build relationships with the children through the medium of group and individual play and recreational activities, and by providing stable day to day routines. In the on-site specialist educational provision, therapeutic relationship-building occurs through individual or group support for engaging in classroom and outdoor learning activities. There is also substantial responsibility for care and education planning and review.

An independent review of children’s residential care in England called for “resilience and moral strength” in the workforce (Narey, Citation2016, p. 60), but stopped short of recommending degree-level professional training for these arguably under-valued and under-trained workers. Despite the demanding nature of the work, English children’s residential care workers and assistant teaching staff working in specialist educational provision continue to only need minimum passes in General Certificate of Secondary Education examinations.Footnote2 In this context, some English residential care and educational providers have developed their own individual additional trainings and reflective practice requirements for staff. The Mulberry Bush is one such organization.

In what follows, we briefly review the background to the study, addressing the policy context in which residential children’s care is provided in England, and noting the importance accorded more widely to reflective practice provision for professional staff supporting vulnerable populations. We also describe the training and support for reflective practice offered by the Mulberry Bush. We then explain the methodology employed in our study and present our findings. A concluding discussion comments further on the nature of the organizational provision needed to sustain the therapeutic dimension of the work.

Background to the Study

Residential Care in England: The Policy Context

A recent review of the children’s social care policy context in England called for a revitalization of family-based care for children moved from their immediate birth families, emphasizing the rich, organic, loving relationships potentially available in such settings (MacAlister, Citation2022, p. 8). The English Secretary of State for Education’s (Citation2023) “Stable Homes Built on Love” consultation on out-of-home care also emphasizes the need to create a culture of “family first,” whilst proposing an overhaul of the quality of leadership and management in children’s homes, with the possibility of professional registration for the workforce (pp. 18–19).Footnote3 Criticisms of “institutional” care in the UK are longstanding and can be fed by the normative power of discourses of “the family” in this context (Blakemoore et al., Citation2022), and as Holmes and colleagues note, by the historical and ongoing positioning of residential care as a “placement of last resort” (2018). A clear justification of the purpose of such a placement is therefore required and primary consideration should be given to how staff will provide the trusting, committed, supportive relationships the child will need.

The Importance of Reflective Practice When Working with Trauma

In professions working with vulnerable populations, particularly where there is relationship-building purporting to be therapeutic in some capacity, ongoing reflective practice and supervision is a requirement for the role. Reflective practice is defined by one such professional body as:

“ … the thought process where individuals consider their experiences to gain insights about their whole practice. Reflection supports individuals to continually improve the way they work or the quality of care they give to people … reflecting in groups, teams and multi-professional settings is an excellent way to help develop ideas or actions that can improve practice.” (UK Health and Care Professions Council, 2019)

Practitioners working directly with traumatized children need reflective practice that supports the development of emotional resilience, both for their own wellbeing, and because emotionally resilient staff are more able to remain empathic and thoughtful in challenging situations. However, as commentators have noted, this is often not foregrounded in residential care and educational staff training (Barnett et al., Citation2018; Jenney, Citation2020; Steinkopf et al., Citation2021). In England, whilst the relevant governmental guidance for children’s homesFootnote4 has a requirement for supervision that supports reflection on practice, the form this should take, and the amount to be provided, is not specified. The relevant pre-degree level diplomas that may be provided for staff in these settings have minimal reflective practice requirements (as little as ten hours of individual study time for observational or journal-based work).

Steinkopf’s et al. (Citation2021) study of experienced Norwegian residential childcare social workers captured workers’ own opinions regarding what practitioners need in role. Respondents’ answers pointed to the need for “ … almost radical self-scrutiny and self-disclosure” (p. 355) and the central importance of an open, organized, shared reflective culture to facilitate this personal exploration alongside a working environment that supported them in regulating their emotions and provided them with a trustworthy theoretical model guiding practice. Steinkopf et. al. also noted the tendency of service providers to focus on evidence-based training at the expense of organizational and structural factors, a point reiterated by Russ et. al., who drew attention to the focus on “frontline” practitioner capacities at the expense of systemic factors and “workplace social capital” (Russ et al., Citation2019, p. 4) in their Queensland-based study of child protection social workers identifying as resilient. Similarly, in a pivotal collection on sustaining trauma-responsive services in child welfare, Strand and Sprang (Citation2018) unpack the potential of trauma to “thwart” and “disrupt” wider organizational and social systems (p. v), arguing for a move beyond “training for individual coping” (p. 24) to focus on how organizations can sustain resilience throughout their systems.

Reflective Practice at the Mulberry Bush

The Mulberry Bush is a charity founded in 1948 offering a mix of 38- or 52-week 3-year residential and educational placements for approximately 30 children aged between 5 and 13 years, in partnership with each child’s (foster, adoptive or occasionally, birth) family and referring authority. Its statement of purpose is “to provide specialist therapeutic services to meet the social, emotional and educational needs of emotionally troubled and traumatized children, their families and wider communities” (2022). It is accredited by the UK’s Royal College of Psychiatrists as a therapeutic community and has core principles of psychodynamic thinking and collaborative working supporting its reflective practice provision.

New Mulberry Bush practitioners complete a compulsory part-time in-house foundation degree award (FdA) in Therapeutic Work with Children and Young People incorporating reflective practice modules and an ongoing student experiential reflective group. Attendance at regular experiential reflective practice meetings is mandatory for all staff, including those not working directly with children and families. These encompass individual supervision with one’s line manager, house, class and family workers’ team group supervision, and “reflective space” in groups composed of members from across the organization. The senior leadership team has externally facilitated “reflective space” groups and facilitators of reflective spaces have half termly group supervision. Reflective practice also occurs informally, at transition and hand-over points, and in social spaces within and outside the organization.

In participating in the reflective experiential milieu, staff are asked to undertake the task they are also supporting the children with – bringing feelings into awareness for reflection in an appropriately paced and non-intrusive, safe way. The aim of the reflective practice provision is to provide staff with a safe space in which to understand more about emotional dynamics and feelings they are experiencing with the children or in their teams, to inform a range of practice decisions and protect against malpractice.

Our study was commissioned by the Mulberry Bush to research staff experience of the reflective practice provision, including which aspects were working well, and which, less well. The sections that follow review the methodology and present our findings. A discussion of the findings follows.

Methodology

Sample

The research project obtained ethical approval from the University of East London’s Research Ethics CommitteeFootnote5 and all 120 staff at the Mulberry Bush were invited to participate. 16 first year FdA students agreed to their reflective essays (based on a private practice journal) being analyzed for the project, and the essays, in two parts (completed at the start and end of the academic year) were anonymized before being given to the research team. 18 staff members took part in semi-structured interviews and 14 took part in a focus group, with an overlap of 6 people participating in both ().

Table 1. Dataset.

The majority of the 16 first year FdA students were new therapeutic care practitioners (TCPs, or residential childcare workers) and teaching assistants (TAs). Of the 18 interviewees, 6 were TCPs or TAs, 3 were from specialist services such as family support, 5 were administrative or ancillary staff such as housekeepers and 4 were from the senior leadership team. In the focus groups, one contained managers and senior leaders (FG2), and one did not (FG1), to ensure more junior staff were not inhibited in expressing their views by the presence of line managers or supervisors. This latter group was evenly split between TCPs and TAs, and other staff members.

To preserve anonymity we have not recorded the demographics of our sample. Our dataset reflected the demographics of the organisation, sited in a rural area of southern England – ethnically, most staff are white, with 66% identifying as female and 34% male. 63% of the senior leadership team are male and 38% female. New recruits at TA level are fairly evenly distributed according to age although slightly more than half are under 35 years; at TCP level, though, the pattern is reversed with slightly more staff older than 34 years6” Footnote 6 on this page should read, ”6 TAs: 18-24 years old 28%; 25-34 years old 25%; 35-44 years old 17%; 45-54 years old 25%; 55-64 years old 6%. TCPs: 18-24 years old 25%, 25-34 years old 17%, 35-44 years old 42%, 45-54 years old 17%.” . TAs make up 16% of the Page 3 of 3 staff group, and TCPs, 51%.

Data Collection and Thematic Analysis

In the FdA reflective essays based on students’ private practice journals, staff are asked to demonstrate an ability to reflect on and develop their own practice in the work setting, showing an awareness of the impact of the work personally and on interactions with others. In the research context, our focus was on what students reported of their experience of their practice, of the support provided for them, and of learning to use the reflective provision. In our semi-structured research interviews, staff were asked about their experience of formal and informal aspects of the reflective provision, their understanding of the reflective practice “model” and participation in it, and their management of dilemmas, struggles and challenges within the reflective process, as well as their opinion about what could be done differently. The focus groups were structured around themes emerging from the interviews.

The dataset was analyzed using thematic analysis, a flexible analytic tool easily explicable to informed wider audiences, an advantage in applied research (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013, p. 180). Initially, two researchers separately completed line-by-line coding of a third of the reflective essays, generating 57 codes. A “consensus” meeting including a third team member generated a preliminary thematic map with several emergent main themes, each of which contained 5–6 sub-themes based on joint decisions revising the initial coding. Possible over-arching themes were identified, relating to “the practitioner journey.” The remainder of the essays were then analyzed by the original two researchers using this map, with adjustments for some new codes. The process was repeated with the interview data by the second and third members of the team, and after discussion of separate analyses of the focus group data, a day-long meeting arrived at consensus between the four researchers in relation to the final thematic map.

We also conducted a simple numerical calculation of the frequency of sub-themes occurring, with “very frequent” describing sub-themes referred to 6 or more times on average within each essay, interview or focus group, “frequent” describing those referred to on average 3 or more times, “regularly” describing those referred to on average more than once and “sometimes” referring to sub-themes occurring at least once across more than half of the dataset.

Whilst it is important to address the key themes that can inform staff experience of the reflective practice provision, including which aspects were working well, and which less well, breaking up respondents’ material into separate themes does not capture the narratives presented by participants of their practice learning journeys within their individual essays and interviews. A composite vignette was therefore created to capture the unfolding and contextualized nature of their experiences (Willis, Citation2019), representing the most common practice examples offered by participants, and illustrating the complex, situated and interconnected nature of people’s lived experience in the organization

Findings

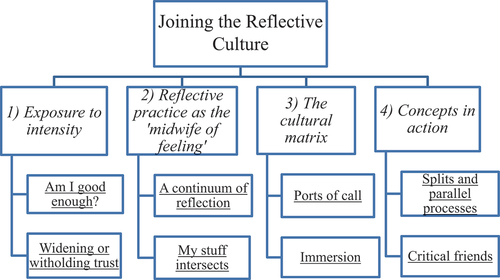

Joining the Reflective Culture

Findings were grouped under 2 over-arching themes, and only analysis from the first of these, “Joining the reflective culture: a developmental arc,” is presented in this article in depth. This theme directly addresses individual staff experience of participating in the reflective provision. A second overarching theme, “Maintaining the reflective culture: constancy and change,” is briefly reviewed, to address staff opinions on what was working well, and for whom; and what needed to change.

Exposure to Intensity

The first of the four central themes, “Exposure to intensity”, described how, in working therapeutically with trauma, staff felt exposed to the children’s very high levels of shame, fear, anger, alienation and confusion, with this essay extract being a typical example:

The level of angriness towards me that I was getting from the children was so high that it really got into me! As soon I stepped out of class I just burst into tears! Just crazy! And I couldn’t stop crying … Just couldn’t … I heard other people say that there was no reason to feel embarrassed because everybody had been in my position before and it is totally normal, but my mind was exploding with thoughts. Will I ever be good enough? (Essay 13)

Our analysis recorded staff struggling to withstand not just the “adverse experiences” visited upon them by the children, as the children sought to communicate and understand their own traumatic histories, but the sense of adversity and attack inside – Maybe I’m just not good enough for this job and the children need someone better? (Essay 12); How long until they realize I am a fraud? (Essay 9). “Am I good enough?” was the first of the two sub-themes grouped here, occurring very frequently in the FdA assignment dataset (in all but one of the 16 essays) and in all but two interviews.

The experiential reflective culture also asked staff to bring their own difficult emotions “on stage” for reflective consideration with supervisors, in group supervision, and within reflective spaces. Staff therefore had a dilemma about disclosure – how much to “open up” or to conceal. The level of disclosure of feeling came as a surprise, even a shock to new staff, and the requirement to scrutinize yourself could feel quite intimidating:

For me, fear of being judged is very real and it takes a lot for me to ask for help and show people my own insecurities as well as acknowledging them myself. My supervisor helps me to share my experiences and feelings with the team. I am learning that I can’t fix things on my own, and no one expects me to. (Essay 11)

The second sub-theme under “Exposure to intensity” was therefore, “widening or withholding trust” in colleagues, either willingly or unwittingly, and it was identified very frequently across all three datasets with no exceptions.

Reflective Practice as ‘The Midwife of Feeling’

The second of the four central themes, ‘Reflective Practice as “the midwife of feeling”, included a sub-theme describing a “continuum of reflection”. This named the way the staff reflective milieu mirrored that provided for the children. It was the most frequently occurring theme, mentioned by everyone:

It’s a bit hypocritical if we don’t, when every single day we’re asking the children to be a group, share how they’re feeling, what’s going on for them, talking about things in front of others, and it’s something that is naturally hard for us to do. (FG1, Ppt. 1)

Senior staff were at pains to point out that just as practitioners did not “interpret” therapeutically to the children, the reflective milieu did not make “therapy” interpretations about staff feelings or behavior:

If you’ve not been in therapy or not done a therapy training, that is a really new thing for people. I do feel strongly, we have to be gentle and empathetic, we can’t – a bit like with the children, you don’t want to be bashing down their defences, they need to understand what it’s about before they can really bring themselves to it and feel safe enough in their teams. (Int. 4)

Several of the research participants were open with the research team about their own past traumatic experiences and indeed, these were part of their motivation for doing the work. Nearly all staff were explicit about how working with children who have experienced trauma could generally bring a range of past experiences to mind. This was captured in the second sub-theme, “my stuff intersects,” which occurred frequently in the FdA assignments (in all but one of the essays) and very frequently in all the interviews and focus groups:

I could quite easily sit with some of the children and say yeah, I know. I know what that feels like. But actually that’s not okay, because it’s not about me, it’s about them. But you can frame the way that you work with that child based on the feelings that you’re experiencing and understanding and managing them. I think we have a responsibility for ourselves to say that’s too much and I’m too close to this child now because of this reason and that’s why. (FG1, Ppt. 2)

We noted how new practitioners could be exposed to a triple dose of difficult feelings – from the children, who naturally trust them less, in relation to their own real deficiencies in role because they are just starting, and from colleagues who inevitably need to “carry” them initially. Whilst we conclude in the discussion section below that the Mulberry Bush reflective culture ultimately protects against secondary trauma through its networks of formal and informal reflective support, the research project recommended the introduction of an employee mental health assistance programme and suggested formalizing the informal counseling referral link.

The Cultural Matrix

The third central theme, “the cultural matrix”, captured the web of formal and informal support within the organization. Participants regularly described informal team “debriefs” at points in the working day, informal opportunity-led support from seniors or colleagues or “critical friends,” and personally supportive, self-chosen relationships. The first sub-theme within that of “the cultural matrix” was therefore, “ports of call.” The aim of providing an immersive network of support via a range of “ports of call” was to provide for an exploratory, “holding” response in the reflective milieu that was quickly within reach. The reflective milieu could also be experienced as all-encompassing, with one person describing it as Everywhere literally. I used to say that nothing here stays in a box … everything we say goes somewhere (Int. 1). The second sub-theme under “the cultural matrix” was therefore, “immersion,” occurring frequently (in all essays, the focus groups and all but two interviews). The effect of the culture over time was described as like water on stone and something that changed one as a person. Some staff noted their tendency to take a reflective approach in their relationships outside of work: There’d be things that go on at home, and I’d just say, well, let’s think about that then. How is that making you feel when they’re saying that to you? (Int. 5).

Concepts in Action

As well as a physical structure and network for reflective practice, participants across all three datasets very frequently referred to a range of mainly psychodynamic concepts that structured their understanding of the work, and this was captured in the final central theme of “Concepts in action”. Concepts were used to make sense of the experiences of both children and staff, and to think about “splits” between individuals, groups and teams where there was a danger of “othering” a different individual or group. Staff gave examples of “wondering” about dynamics, without using psychodynamic language:

You have a feeling which you absolutely own, you go into your reflective space and you are a crap practitioner because you got it wrong with that child. The team support you to think about, let’s have a think about what was going on for the child. Those feelings about feeling crap, yes, they’re absolutely real for you, but what does that tell you about what was going on for – oh, okay so the child was feeling really crap. (Int. 8)

This first sub-theme, of “splits and parallel processes,” was the second most frequently occurring across the dataset (after “a continuum of reflection”).

Finally, in addition to formal, theoretical concepts, there were a range of informal precepts or “rules of thumb” regularly mentioned, such as, “there are no right or wrong answers,” “remember what is being put into you here,” “remember to ask for help, we will support you,” “just surviving and turning up to work every day is an achievement and containing for the children,” “don’t just take it personally, we’ve all been there.” Alongside these informal precepts in currency in the organization, there was an expectation one would be open to being challenged about one’s practice, and would offer challenges, in the spirit of being a critical friend. “Critical friends” was therefore the second sub-theme occurring under “concepts in action.” Participants noted that it mattered whether these challenges (from teams or individuals) were felt to come from a supportive place, or to be punitive.

Maintaining the Reflective Culture

This second over-arching theme, touched on briefly here, encompassed lower-order themes that reviewed the ongoing work of maintaining and “tweaking” the reflective milieu. It also included staff responses when asked what was working well, and for whom; and what needed to change.

In relation to what was working well, staff expressed appreciation for high levels of reflective practice resourcing and regularity of provision, the protection of reflective “space” that was not governed by an agenda, the depth and strength of professional relationships made over time, and in-depth, ongoing support for working in teams with the children. In relation to the latter, staff described i) acceptance, support and gentle curiosity when being around a particular child was feeling too difficult; ii) support in exploring a feeling or “intuition” about a child, to work through to its source; iii) review and discussion after a demanding event or critical incident; iv) encouragement to step back from a relationship that was potentially straying away from therapeutic working; v) validation and support for a plan for changing the way of working with a child.

Staff had many suggestions for change, including being clearer about the psychodynamic reflective experiential model for new people and those who were not directly child-facing, preparing such staff better for participation, with practical suggestions about how to do this; adding in other ways of doing reflection; improving timetabling, duration and spacing of reflective practice sessions; clarifying facilitators’ roles and taking more account of the complications when these intersected with line management functions; considering external facilitation and considering who was in which group more carefully. Some of these points were already being addressed but we suggested the organization might usefully further clarify the different functions of 1–1 supervision, line management, group supervision and reflective space respectively, and produce a written, accessible reflective practice policy.

Composite Vignette: Working with ‘Ellie’Footnote6

The composite vignette included below represents the most common practice examples offered by participants, and illustrates the complex, situated and interconnected nature of people’s lived experience in the organization.

“James” came straight from the business sector to become a Teaching Assistant at the Mulberry Bush, observing in his first assignment, I am a male of an age where men were brought up not to acknowledge their emotions and the impact of work upon them.Footnote7 He found the new role and requirement to reflect very demanding:

I was actually terrified of being out of my depth educationally and then sat around in a group of people talking and crying about all these feelings … I was thinking, … what are you doing? You don’t do that here.

“Lara,” a new Therapeutic Care Practitioner, reported in interview that initially she found the reflective milieu a load of mumbo jumbo crap but gradually came to value it, describing previous work in another children’s home without it:

It was like firefighting all the time. You didn’t have any support from anywhere else. For inexperienced staff that was really dangerous because they didn’t understand the process of the work. Lots of people ended up leaving because they couldn’t cope. I think it definitely affected other people’s mental health because they didn’t feel able to speak up about it, they were worried they’d lose their jobs.

James stressed to his interviewer the importance of informal classroom opportunities to observe more experienced colleagues, and time to reflect on their practice, coming to realize, it’s the way you talk to a child, body language, just lots of different things that impact an interaction. He saw other staff using their observations to reflect out loud “over the children’s heads,” modeling a process of wondering about feelings:

Ellie’s eyebrows would almost cartoon-like be inverted and she would look visibly angry, but she wouldn’t present as being angry as such. ‘Mandy’ [teacher] would speak over the class to the other adults – oh I’m wondering why Ellie’s looking a little bit angry at the moment? I wonder if we can help her with how she’s feeling?

This was a practice with all the children and James was impressed with the effect – when we started to notice her eyebrows more, it’s such a little thing and it sounds really silly, but it really did work … we’re now finishing her topic work and then going for a nice playtime in the hall.

Lara was Ellie’s key worker and this involved liaising with her foster family. She described in interview how the first time she met them she felt uneasy. It was just something in the room – I felt really, really, uncomfortable within seconds. She shared this with her house manager, “Eileen,” who didn’t dismiss her feelings but advised a “watch and wait” approach. When Lara reported more elements in the interactions that continued to make her feel uncomfortable, Eileen continued to support her, sharing with Lara that whilst there might be cause for concern, some of the experiences her first key child had had were similar to her own, and it might also be possible that something was being triggered from Lara’s past. Lara noted, this was nowhere on my radar but said she realized a few days later,

I was, oh my god, you said this, I was sure, but actually, yes. It was quite upsetting actually, really, really, confusing, because it made me think about lots of things, how was I feeling these feelings off of the child, whether it was the same thing that I …

Lara reported that the support from Eileen as she worked alongside Ellie helped her not to act prematurely on her impulse not to let her go home; in fact, the foster placement broke down, not for any child protection reasons – Lara reported in interview, it just didn’t work out.

In his journal, James had documented the experience of learning to restrain children and how difficult this could be for him. In his essay he described one particular occasion with Ellie after the class had watched a video about bodies changing, where Ellie had begun “snogging” my arm and another member of staff, then simultaneously kicking them and turning to do the same to an adjacent child. During the restraint James noted, I felt very uncomfortable. I felt like I was abusing her and she was abusing me. I soon began to feel very sick and icky. He noted, I asked another member of staff to swap with me (having learnt this was common practice) but later spoke about this “abuser-abused” dynamic he’d felt in a team meeting. Mandy thought Ellie might be communicating these feelings to him unconsciously, and suggested he reflect more about it.

A week later, Ellie trashed a section of the classroom and James recalled how he had made the decision to try to keep her safe without restraining her or asking for reparation, and how he’d explained this to the “house” team in the handover between school and home. In the next morning “hand over” meeting, Lara had been angry, telling him that she had taken the decision to restrain Ellie from trashing her bedroom that morning, and accusing James of undermining her key work by taking a different approach in class. James was upset because he and Lara had started at the Mulberry Bush together and he thought of her as a good friend and colleague. He discussed the disagreement with his team who encouraged him to take it to a reflective space. Having done this, he was able to find words to talk it through with Lara who eventually accepted it was possible to have two different points of view about practice. The reflective space convenor noted in interview:

Quite often bickering can sit between two people around a particular child. But taking that into the group reflective space will often then result in somebody else going, oh do you know, that reminds me about the other day when so and so did such and such. You said that they could do that thing, and actually I was feeling a bit like, no! Then hopefully all of a sudden you have a team of people who are able to openly talk about differences in practice, how that feels, whether that’s okay, can that be tolerated?

The convenor felt that the shift away from personal blame and disagreement to thinking about and hopefully respecting difference was an important dimension of work in reflective spaces and was ultimately empowering – having a sense of agency in our work is really, really, important.

Lara’s journal recorded her struggles in the key-working relationship. She’d challenged Ellie on several occasions about her behavior and Ellie began targeting her with verbal abuse:

It was raining … so the rain diluted with my tears and nobody noticed anything when I got to the pub. I am at this job for 8 months and it’s the first time I´m feeling devastated. Why? Because a child is calling me ‘whore’ and ‘slut’ and the C word every day, refusing to sit next to me, declining any help from me, avoiding my presence.

Lara recorded feeling increasingly useless and isolated, but eventually spoke to Eileen, who suggested taking her feelings to group supervision, which was both terrifying and a relief. The team thought about what Ellie could be replaying from her past and agreed that Lara should temporarily step back from work with Ellie and focus on practising “in the round” with a range of children.

Discussion

Whilst approximately 40Footnote8 staff are represented in the data, the majority employed by the organization are TCPs and TAs and only approximately 20% of these are represented. Volunteers for the project are more likely to be committed to the reflective milieu and more confident in articulating their views. Therefore, the analysis presented can’t be considered as fully representative of staff experience, and whilst those participating in interviews and focus groups said most practitioner staff “bought in” to the reflective culture, this has not been verified.

What emerges most immediately from consideration of the data from those who volunteered is the arduousness of the work of building trusting relationships with traumatized children. In the extracts included in the thematic analysis above, and in the composite vignette, one can identify the points at which staff are at risk of secondary trauma, carrying “absolutely real” feelings of devastation, sickness, confusion, disappointment and inadequacy. It is possible to see echoes with the children’s experiences and parallels with complex trauma regarding the potential difficulty of emotion regulation, the negative impact on self-identity and the struggle to trust other people. Without the right support staff could easily begin to employ some of the same coping strategies – self-blame and “suppression of thought as an adaptive coping mechanism” (Hiller et. al. op. cit). This can present an obvious threat to staff well-being but there is also the risk of retraumatising children, and as Barnett et al. (Citation2018, p. 95) note, staff do not need to fall into active malpractice to subtly withdraw their therapeutic care.

One does not have to have a traumatic past to feel “triggered” by the working environment. Bateman and Fonagy describe some ordinary defensive ways of coping in situations when feelings are running high, and in response to a sense of “threat” from another:

“ … to i) be excessively assertive; ii) blinding ourselves to the ‘confusing’ perspective of the other; iii) creating a self-serving image of the other that confirms our own ‘beyond reproach’ position; iv) forcing a reaction from the other to reaffirm ‘me.’” (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016, p. 20)

These unthinking ways of reacting characterize the breakdown of “mentalization,” or “reflective functioning,” terms which refer to the capacity to simultaneously hold in mind and understand the thoughts, feelings, wishes and desires of both oneself and the other in an interpersonal interaction. But in the sub-theme of “my stuff intersects,” as described by participants, we can see ways in which the respondents were actively “mentalizing” about themselves in interaction with others, crucially, with the support of the organization (as described by “Lara” in the vignette). The puzzle of whose feelings am I feeling? (Essay 7) linked to the idea that part of the therapeutic work involved tolerating difficult states of mind that might have originated with, or be particularly magnified in, the children. In the words of another member of staff in interview, because we work therapeutically with traumatized children, we have a lot of emotions and feelings that we keep with us that aren’t necessarily ours (Int. 2).

Some useful ways of conceptualizing the important, “therapeutic” element to the ordinary, trusting relationships that residential care practitioners and educational support staff build with the children whilst carrying out day-to-day living and learning tasks are as “other-regulation” (Steinkopf et. al), or support for mentalization and reflective functioning (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016), or attunement (Hazen et al., Citation2020), or resilience and the provision of mindful empathy (Milicevic et al., Citation2016). These capture dimensions of the work.

From our findings, however, we want to emphasize the element of necessarily being in touch with, tolerating and thinking about extremely disturbed states of mind. This element is described psychoanalytically as “containment,” often mis-translated in therapeutic literature as a kind of emotional “holding” or “calming.” In fact, it emerged from Wilfred Bion’s (Citation1962) work with patients in extreme psychotic states who were very frightened and despairing, and who needed their therapist not to be too afraid to approach their experiences, and to be able to offer some sort of understanding that alleviated the acuteness of their states of mental distress and helped with the process of making sense of them.

If a part of the work involves this difficult capacity to be in touch with, and to some degree, “detoxify” the children’s trauma,Footnote9 and the work is not about providing “professional” therapy sessions, but building “ordinary” trusting relationships, the question of the kind of training and support needed comes sharply into focus. As Strand and Sprang note, there is a need to move beyond models of trauma work that rely solely on the individual capacities of the practitioner and to think about the kind of organizational environment needed to house the work.

Our findings concerning the centrality of a thoughtful, non-judgmental theoretically informed reflective milieu in supporting staff echo those of Steinkopf et. al – the need for a trustworthy theoretical model to guide the work and a regulating work environment to support management of feelings. We found participants in our research could clearly articulate the psychodynamic model used by the Mulberry Bush and confidently illustrated their reliance upon it with practice examples. They further described learning to use a “matrix” or “web” of reflective support containing many ports of call, formal and informal, running through the organization at different levels and across different functions and teams, arguably, to “saturation” point.

Additionally, we suggest that Steinkopf’s et al. (Citation2021) findings can be usefully widened to include “epistemic trust” (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016, p. 23) in an organizational culture as key to effective teamwork and personal growth in role. Across the dataset, “widening and withholding trust” was the third most frequent sub-theme. Bateman and Fonagy (Citation2016) define “epistemic trust” as: “ … trust we place in the information about the social world that we receive from another person […] the extent and ways in which we are able to consider [that] social knowledge as genuine and personally relevant to us. (p. 24). These authors note that effective “culture carriers” are adept at offering salient information in a way that is contingent upon, or tailored by, the responses of the other. The informal precepts described as “rules of thumb” in the section on “concepts in action” above, and the work of “Eileen,” “Lara’s” supervisor, are good examples of sensitive transfer of relevant cultural information for new staff in the Mulberry Bush setting in a way that will enhance their trust in the reflective provision.

Individuals open to social and emotional knowledge offered in a sensitive and tailored way have access to an informational resource that empowers and strengthens their sense of agency and decision-making, and it is also this “openness” and trust that work with the children in the therapeutic milieu seeks to unlock. Epistemic trust in an organizational culture is key to effective teamwork and personal growth in role. If staff trust in the organization’s support, they can carry out the work of building trusting relationships within the milieu and use these as the vehicle for promoting children’s own trust, recovery and post-traumatic growth.

Conclusion

This article has reviewed the findings from a case study of the lived experience of a sub-set of staff (approximately 40 of 120 employees) at the Mulberry Bush, England, a residential children’s home and specialist school for 5–13-year-olds who have experienced complex trauma. It has drawn upon a thematic analysis of 16 training assignments, 18 semi-structured interviews and contributions from 14 members of two focus groups to argue for the need for sustained and systematically planned reflective practice provision at an individual, group and organizational level in residential care and education for this child population. This is a small-scale study with a limited sample and further research into the benefits of reflective practice in residential care organizations is needed, possibly including quantitative measures such as reflective practice questionnaires (see Priddis & Rogers, Citation2018).

We have suggested that Steinkopf’s et al. (Citation2021) findings concerning the need for a regulating working environment and trustworthy theoretical model should be supplemented by a consideration of the role played by factors that build individual staff members’ epistemic trust in the working environment. Our findings show that at the Mulberry Bush, the process of learning to use the resource of the community requires incremental trust and commitment over time, supported by personal testing to see if it is reliable and helpful, as well as organizational commitment to the individual learner.

Implementing and sustaining a reflective culture that permeates the whole organization and its systems may depend on local factors, but our findings would suggest key transferrable elements are: i) senior management commitment to and visible participation in regular reflective practice; ii) regular reflective supervision for in-house or external reflective practice and group supervision facilitators; iii) a clear, trauma-informed theoretical underpinning for the reflective practice model chosen; iv) mandatory reflective practice attendance across the organization; v) free, mandatory in-depth qualifying training for new employees with a strong, assessed reflective practice component and vi) a commitment to a reflective practice policy that is a “living” document open to change and adaptation following regular consultation with staff.

Building a culture of “epistemic trust” in care and educational settings, involving the pooling and sharing of a range of reflective resources, may require a critical mass of people. MacAlister’s (Citation2022) report on children’s social care in England prioritizes support for family-based placements and the communities around them, but emphasizes the importance of building supportive, trusting, stable relationships with children above all else. As the research findings in this article show, sometimes, the work needing to be done by the metaphorical “village” (p. 18) that MacAlister seeks to mobilize around children in out-of-home care is exceptionally demanding. It can require specific training and support, and whilst increased provision of specialist therapeutic foster care is to be welcomed, children’s homes and specialist residential schools may make a vital contribution to the range of care provision available, particularly for children for whom the intimacy and small size of family life can feel threatening. Slightly larger institutions do not automatically create professional distance; on the contrary, the group resource available can support staff to take the risk of being in touch with the children’s lived experience and their feelings, whilst sustaining a capacity to think and offer a therapeutic response.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Caryn Onions for acting as our point of contact with the organisation throughout the research period and are also grateful to the staff of the Mulberry Bush and the wider organisation who gave their time to take part in the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. “It’s kind of like this particular job is a bit like you’re going to therapy yourself in a way. I find it, for me it pushes you to be in touch with things that have happened in your life that you can’t face away from. Some events with children will bring back things or force you to sort of look at parts of you.” (Int. 2).

2. Whilst many settings ask for pre-degree level (post-16) diplomas in residential childcare or in supporting teaching and learning in schools, these are not requirements for employment.

3. The consultation document notes, “Over the next two years we will gather data and qualitative information to enhance our understanding of the children’s homes workforce. We will undertake a workforce census in 2023 and 2024 and carry out in-depth cases studies, which will focus on recruitment, retention, qualifications and training” (p.100).

4. The Department for Education’s (2015) Guide to the Children’s Homes regulations states, “ … all staff, including the manager, [must] receive supervision of their practice from an appropriately qualified and experienced professional, which allows them to reflect on their practice” (2015: 61).

5. The informed consent obtained included an explanation of the limitations on anonymity afforded in a study where the organization would be formally identified.

6. Individuals are fictionalized composites and aspects of the data have been altered to preserve confidentiality.

7. The data extracts in italics incorporated into the composite vignette are taken from a range of participants’ essays and interview and focus group responses.

8. An exact figure is not possible because the overlap between interviewees/focus group members, and FdA students is not known, as the latter’s assignments were already anonymized.

9. And not necessarily “interpreting” this, but just being able to stay alongside the child with their experiences in mind.

References

- Barnett, E. R., Yackley, C. R., & Licht, E. S. (2018). Developing, implementing, and evaluating a trauma-informed care program within a youth residential treatment center and special needs school. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 35(2), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2018.1455559

- Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2016). Mentalization-based treatment for personality disorders: A practical guide. Oxford University Press.

- Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from experience. Heinemann.

- Blakemoore, E., Narey, M., Tomlinson, P., & Whitwell, J. (2022). What is institutionalising for ‘looked after’ children and young people? Journal of Social Work Practice, 37(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2022.2034766

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. Sage.

- Briheim-Crookall, L., Michelmore, O., Baker, C., Oni, O., Taylor, S., & Selwyn, J. (2020) What makes life good, care leavers’ views on their well-being. Coram voice/The Rees centre. Retrieved from: https://coramvoice.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/1883-CV-What-Makes-Life-Good-Report-final.pdf

- Cloitre, M. (2020). Editorial: ICD-11 complex post-traumatic stress disorder: Simplifying diagnosis in trauma populations. British Journal of Psychiatry, 216(3), 129–131. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.43

- Department for Education. (2015) Guide to the children’s homes regulations including the quality standards, Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/childrens-homes-regulations-including-quality-standards-guide

- Department for Education. (2023, February). Stable homes, built on love: Implementation strategy and consultation, children’s social care reform 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/childrens-social-care-stable-homes-built-on-love

- Hazen, K. P., Carlson, M. W., Hatton-Bowers, H., Fessinger, M. B., Cole-Mossman, J., Bahma, J., Hauptman, K., Branka, E. M., & Gilkerson, L. (2020). Evaluating the Facilitating Attuned Interactions (FAN) approach: Vicarious trauma, professional burnout, and reflective practice. Children and Youth Services Review, 112, 104925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104925

- Hiller, R. M., Meiser-Stedman, R., Elliott, E., Banting, R. H., & L, S. (2021). A longitudinal study of cognitive predictors of (complex) post-traumatic stress in young people in out-of-home care. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(1), 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13232

- Holmes, L., Connolly, C., Mortimer, E., & Hevesi, R. (2018). Residential group care as a last resort: Challenging the Rhetoric. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 35(3), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2018.1455562

- Jenney, A. (2020). When relationships are the trigger: The paradox of safety and connection in child and youth care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 37(2), 94–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2019.1704671

- Keyes, K. M., Eaton, N. R., Krueger, R. F., McLaughlin, K. A., Wall, M. M., Grant, B. F., & Hasin, D. S. (2012). Childhood maltreatment and the structure of common psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(2), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093062

- MacAlister, J. (2022). The independent review of children’s social care final report. https://childrenssocialcare.independent-review.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/The-independent-review-of-childrens-social-care-Final-report.pdf

- Milicevic, A., Milton, I., & O’Loughlin, C. (2016). Experiential reflective learning as a foundation for emotional resilience: An evaluation of contemplative emotional training in mental health workers. International Journal of Educational Research, 80, 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2016.08.001

- Narey, M. (2016) Residential Care in England: Report of Sir Martin Narey’s independent review of children’s residential care. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/534560/Residential-Care-in-England-Sir-Martin-Narey-July-2016.pdf

- Priddis, L., & Rogers, S. L. (2018). Development of the reflective practice questionnaire: Preliminary findings. Reflective Practice, 19(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2017.1379384

- Russ, E., Lonne, B., & Lynch, D. (2019). Increasing workforce retention through promoting a relational-reflective framework for resilience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110, 104245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104245

- Seti, C. L. (2008). Causes and treatment of burnout in residential childcare workers: A review of the research. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 24(3), 197–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865710802111972

- Steinkopf, H., Nordanger, D., Halvorsen, A., Stige, B., & Milde, A. M. (2021). Prerequisites for maintaining emotion self-regulation in social work with traumatized adolescents: A qualitative study among social workers in a Norwegian residential care unit. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 38(4), 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2020.1814937

- Strand, V. C., & Sprang, G. Eds. (2018). Trauma responsive child welfare systems, Springer International.

- Willis, R. (2019). The use of composite narratives to present interview findings. Qualitative Research, 19(4), 471–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794118787711