ABSTRACT

In this paper, I analyze the use of architecture and affect as means for ensuring a prepared and resilient population. I do this by exploring an empirical case of public simulation centers, which are an emerging type of educational facility with the purpose of training the public for future emergencies using advanced simulations. Accordingly, existing anticipatory techniques are being redeployed and applied to a new target group, the public, which calls for renewed engagement with the use of space, physical design, and affect as means for involving and fostering the public in societal preparedness. Drawing on literature on anticipatory governance, I focus on two questions, elaborating first how public simulation centers produce and enable security affects and, second, exploring the means, material and immaterial, by which these centers attract and involve citizens in security practices.

Introduction

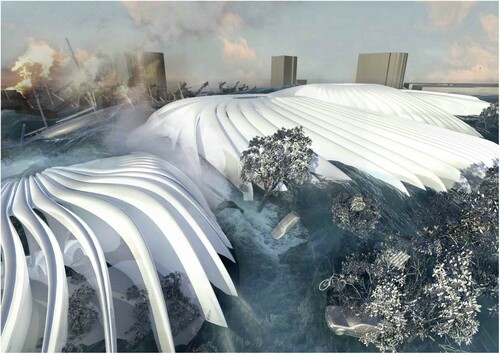

Imagine yourself on a street in a downtown area just moments after a major earthquake has hit the city. A peculiar blend of post-disaster stillness and sounding alarms and sirens characterize the atmosphere around you. From your vantage point, you see cracked buildings, curved lampposts, and piles of concrete rubble. A few steps away you see flames and smoke coming out of a broken window. Down the street, a man is lying on his back on the pavement. The lower part of his body seems to be stuck under a car, as if he was busy repairing it when the quake started. At the farther end of the street, a desperate cry for help sounds from somewhere underneath a huge pile of rubble. You look around for people who might assist you in saving the injured. Now, imagine that the scene just described is not for real but an artificial environment, created and designed to convey the feeling of being there when the Big One has just struck your city. Thus, a realistic full-scale simulation of a downtown street as it may appear a few minutes after a major earthquake has taken place. Imagine, further, that this artificial full-scale representation of a disaster-struck neighborhood is contained within a spectacular building, an extreme architectural construction comparable to existing futuristic landmarks, such as Zaha Hadid’s Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku, Azerbaijan, or Paul Andreu’s National Grand Theater in Beijing.

What we are being introduced to here, and what will be further explored in this paper, is a specific configuration of material and immaterial elements, practices, and techniques that serve to evoke particular affects assumed to enhance individual preparedness in the event of future disasters. Concretely, the paper presents an analysis of a unique empirical phenomenon labeled here as “public simulation centers”. Accordingly, through the case of public simulation centers I explore, alluding to Kraftl and Adey (Citation2008, 226), how affect is design(at)ed to operate in many ways, and how architectural design operates via discourse and practice, materiality, and immateriality, to evoke particular affects.

Public simulation centers are publicly operated facilities, free of charge and open to everyone, with the aim of providing disaster education and training to specific target groups (e.g. schoolchildren) as well as the public at large. Training is provided through full-scale simulations of a disaster-struck urban area, in which participants may practice appropriate response behavior. The main purpose of the simulation, however, is to enact or “play” potential emergency futures so that participants may get a feel, in advance, of what these futures might be like (Adey and Anderson Citation2012; Anderson Citation2010; Anderson and Adey Citation2011; Aradau Citation2010; Collier Citation2008; Lakoff Citation2007). In this sense, public simulation centers can be understood as a novel form of physical location or space, created in response to the problem of governing present action in relation to future emergencies.

Of course, scholarly interest in how possible future emergencies are governed and intervened on in the present is not new. In particular, during the past decade, we have seen a vast number of detailed explorations into the anticipatory logics, practices, and techniques for making futures affectively and materially present in organizational and professional contexts. For example, the emergence of the “uncertainty-based” logic of preparedness, as supplementing the “risk-based” logic of calculation, has been thoroughly described by Collier (Citation2008) and Lakoff (Citation2007, Citation2017), and later summarized by Aradau and van Munster (Citation2013), O’Malley (Citation2013), Samimian-Darash and Rabinow (Citation2015), and Samimian-Darash (Citation2016), to name but a few. Common to this body of literature is that it takes its principal starting point in Michel Foucault’s lectures and writings on biopolitics as a form of governance. As noted by Samimian-Darash (Citation2016), sovereignty, discipline, and biopolitics all developed in response to specific governmental problems, and was enacted to achieve certain aims through determinate practices. Biopolitical security, then, emerged in response to the problem of circulation and freedom, that is, to the need of securing the unhindered movement of people, goods, money, ideas, etc. and thereby to foster and secure the welfare of populations (Samimian-Darash Citation2016, 361). Mirroring the (intentionally crude) risk/calculation–uncertainty/preparedness distinction above, Collier and Lakoff (Citation2015) distinguish between two principal forms of biopolitical security, namely population security (which addresses regularly occurring events that are distributed over the population in predictable ways) and vital systems security (which deals with events whose probability cannot be precisely calculated but whose consequences are potentially catastrophic). In vital systems security, anticipatory knowledge of potential future emergencies is thus generated primarily through practices and techniques of imaginative enactment and simulations (Collier and Lakoff Citation2015, 22).

Drawing on this broad stream of literature, this paper suggests that public simulation centers can be understood as an emerging technologyFootnote1 of security which articulate specific relations between governments and populations (Deville, Guggenheim, and Hrdličková Citation2014), and in which futures are made present through affects (Anderson Citation2014, Citation2015; Anderson and Adey Citation2011), sensory experience and atmosphere (Adey Citation2014), and material design (Kraftl and Adey Citation2008). Acknowledging that the field (of anticipatory techniques for governing uncertain futures) has reached a certain maturity, I nevertheless maintain that there are important additional contributions still to be made. This paper advances the existing literature in three distinct ways.

First, it fills a gap by focusing explicitly on the public. Concretely, the paper provides an empirical example of how the public gain access to advanced forms of simulation-based preparedness exercises – an area that has typically been reserved for experts, leaders, officials, and other types of emergency “professionals” (Lakoff Citation2007, 265). Previous research in the field has for the most part drawn on empirical studies of simulation-based exercises and similar anticipatory techniques in various organizational settings. Well known examples include Anderson and Adey (Citation2011, Citation2012) and Adey and Anderson (Citation2012) on anticipating and governing emergencies, and security affects, in the context of U.K. Civil Contingencies; O’Grady (Citation2016, Citation2018) on anticipatory governance through digital representations of potential emergency futures, and their role in the design and performance of exercises, in the context of U.K. Fire and Rescue Services; Samimian-Darash (Citation2016) on exercises in the context of Israel’s National Emergency Management Authority; Aradau (Citation2010) on exercises in the context of the U.K. National Counter-Terrorism Security Office; and Kaufmann (Citation2016) on the interplay of affect and action in the context of a cyber-security exercise conducted by the German Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance. Indeed, Kaufmann (Citation2016) explores the exercise as a route to foster resilient subjects; however, the exercise itself is still conditioned by and performed within an organizational setting, implying that it is not intended to involve the “non-professional” public (which is precisely the stated purpose of public simulation centers).

Second, by affirming this novel way of involving the public in security practices independent of its prevalent organizational and professional contexts, the paper highlights the specific techniques employed for making futures present in these centers, namely imaginative enactment and simulation (Anderson Citation2010; Collier Citation2008; Lakoff Citation2007). Now, as Kaufmann (Citation2016, 100) rightly suggests, the involvement of citizens into security practices is nothing new. What is new in connection to the emergence of public simulation centers is the accessibility for all citizens to advanced simulations for the specific purpose of training emergency preparedness. Traditionally, the involvement of citizens into security practices has been limited to educational campaigns and school programs (Collier and Lakoff Citation2008; Davis Citation2007), including drills and movies (like the famous Duck and Cover cartoon in the 1950s, which taught American children what to do when they saw the flash of an atomic bomb) (DHS Citation2006), or the exhortation to report suspicious behavior (Kaufmann Citation2016, 100; Aradau and van Munster Citation2013, 100), hence without access to advanced simulation exercises. Simulation-based exercises, as noted, has been mostly reserved for “professionals” in various organizational settings, like the military and civil defense, rescue services, and civil contingencies (Lakoff Citation2007). Accordingly, the case of public simulation centers becomes a current example of how existing techniques for governing future emergencies migrate between sectors, and are being redeployed and applied to new target groups (Adey, Anderson, and Graham Citation2015).

Third, public simulation centers constitute physical locations, and spaces, for making futures affectively and materially present. That is, they are buildings, in terms of architectural design, as well as producers or enablers of security affects. In this sense, the present paper aims to answer the call to “attend to the ways in which those affective potentialities are negotiated in and through practices of inhabiting buildings” (Kraftl and Adey Citation2008, 228), and to contribute to discussions on the spatialization and aestheticization of uncertain and potentially threatening futures (Aradau and van Munster Citation2012, Citation2013; O’Grady Citation2018).

Hence, in this paper, my aim is to explore architectural design and affect as elements of a novel security technology intended as a response to the governmental problem of securing the welfare, freedom, and circulation of citizens by fostering a prepared and vigilant public. Thereby I do not consider it within the scope of the paper to investigate or determine the possible advantage of public simulation centers over traditional “cognitivist” preparedness campaigns intended for the public. Rather, the two interrelated issues I analyze and account for boil down to the following questions: first, how do public simulation centers produce and enable security affects and, second, with what (material and immaterial) means do these centers attract and involve citizens in security practices? The paper is structured as follows: After this introductory section, I provide the paper’s empirical and methodological background, and then I present its theoretical orientation. In the main section, I analyze and discuss the elements of affect and architecture in the context of public simulation centers. In the concluding section, I reflect on the outcome of the analysis and discuss some implications of the paper’s theoretical approach.

The emergence of public simulation centers

This paper builds on an empirical case consisting of three public simulation centers, of which two exist as physical buildings and one exists in multiple versions as an architectural imagination.Footnote2 Of the three, the first actual operative center, inaugurated in 2010, is the Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park (Citation2021a) (hereafter the Tokyo Center). This facility is located on the artificial island of Odaiba in Tokyo Bay. The second actual operative center, inaugurated in 2013, is the Bursa Disaster Education and Training Center (Citation2021) (hereafter the Bursa Center), which is located in Bursa City, the fourth largest urban center in Turkey. The Tokyo and Bursa Centers contain – in addition to the full-scale simulation mentioned in this paper’s vignette – a number of exhibition spaces, lecture halls, 3D-cinemas, libraries, and cafés.

The third center, the Istanbul Disaster Prevention and Education Centre (hereafter the Istanbul Center) is an, as yet, unbuilt facility with a planned location next to the former Istanbul Atatürk International Airport. The Istanbul Center exists in the form of digitally rendered images and sketches, which served as project proposals in an architectural competition announced and decided in 2011. At present, there is no indication that the facility in Istanbul will ever be built.

The very first center of this particular kind was the Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution (DRI Citation2021) in Kobe, Japan (hereafter the Kobe Center). Although not part of the empirical material for this paper, I wish to mention the Kobe Center briefly as part of the historical context. This center was established in 2002 in commemoration of the 1995 Great Hanshin Awaji Earthquake, with the aim to educate citizens in disaster preparedness, based on experience of the 1995 earthquake (Cabinet Office, Japan Citation2015, 56; Murata Citation2005, 106; Nishikawa and Yukinari Citation2015, 21). The Kobe Center’s goals are presented on its official webpage:

Our goals are to ensure that the lessons of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake are never forgotten. Big-screen footage and soundscapes are used along with recreations of the earthquake using special effects and computer graphics to let visitors experience the terrifying power. Moreover, we offer games and experiments so that visitors can learn about natural disasters and how to minimize risk and damage in [the] future. (DRI Citation2021)

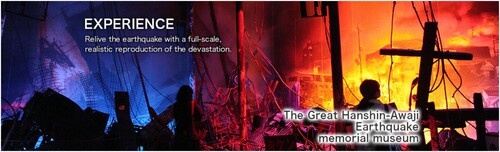

Streets after the quake

One of the more innovative features of the Kobe Center is the creation of a particular section called “Streets after the quake”. This section consists of a full-scale, three-dimensional, realistic reproduction of a typical downtown neighborhood as it may look after being struck by a major earthquake. The purpose of this section is to let visitors experience the feeling of being in the midst of an urban space moments after a quake and to practice appropriate post-disaster behavior. On the center’s official webpage, this particular section is introduced with the statement: “Relive the earthquake with a full-scale, realistic reproduction of the devastation” ( below).

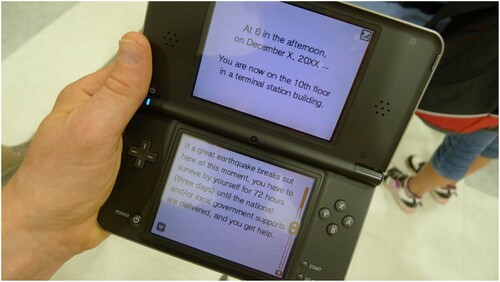

In this paper, I explore the “Streets after the quake” section of the Tokyo and Bursa Centers. At the Tokyo Center, this particular section is called “the 72-hour tour” (Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park Citation2021b) and at the Bursa Center, it is called “the earthquake debris corridor” (in Turkish: deprem enkaz koridoru) (Güvencem Citation2021a). On the Tokyo Center’s official website, the 72-hour tour is introduced as follows:

It is said that organized rescue efforts are usually performed seventy-two hours after an earthquake occurs. So, how would you survive during those seventy-two hours when rescue is difficult? This tour allows you to experience the flow of events starting with the [outbreak of the disaster]. In a diorama where you experience repeated aftershocks through sound, lightning, and imagery, you will make your way to an evacuation area while asking a quiz with a portable game machine. (Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park Citation2021b)

[It is] a corridor where damaged buildings with various ruins can be seen after an earthquake, an observation corridor prepared with light, sound and different building materials is established and aims to provide the visitors with the post-earthquake situation. Realistic images are obtained using various wood, plastic and construction materials. The debris corridor is constructed by benefiting from the images of the earthquakes that have taken place before. In the earthquake, the people who are under the debris are trained in how to rescue and how to help. (Güvencem Citation2021b)

Assembling the case of public simulation centers

The research on public simulation centers carried out in preparation for this paper involved two rounds of fieldwork and an extensive document study. Fieldwork, with a particular focus on the 72-hour experience and the debris corridor, was carried out at the Tokyo Center in July 2014 and the Bursa Center in November 2015. This work was largely informed by the methodological ideas of sensory ethnography, as developed by Leder Mackley and Pink (Citation2013) and Pink (Citation2015).Footnote3 The empirical material assembled during this phase consists of field notes, informal interviews, photographs, and video clips from approximately 30 hours of participant observation. In addition, I have collected and systematized a considerable amount of internet-based material, such as news articles, blog posts, video clips, and websites associated with the Tokyo and Bursa Centers. On site, I participated in pre-booked training sessions along with various groups (such as primary school pupils, people with functional diversities, and office employees), along with informal drop-in sessions intended for the public at large. In a subsequent phase, during 2017 and 2018, I supplemented the exploration of the Tokyo and Bursa Centers with an internet-based document study of the unrealized Istanbul Center. The remainder of the present section provides an account of the Istanbul sub-case.

In February 2011, an international architectural competition was announced for a design idea regarding a disaster prevention and education center in Bakırköy, Istanbul. Conditions for the competition were developed jointly by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality and the promoters of the award, ThyssenKrupp Elevator. The objective of the project was, as stated in the Competition Brief and Conditions:

… to establish a technology centre, which shall be an example of the “Edutainment” approach and equipped with adequate infrastructure to conduct educational activities towards preparing the visitors against disasters [and] to create a state of the art design which aims to contribute to Istanbul’s urban context. (ThyssenKrupp Citation2011, 3)

Once a planned architectural project has been realized, the epistemological focus shifts (Grosz Citation2001, 129), which allows for investigating the frictions between visualizations and material outcomes of architectural plans (Balke, Reuber, and Wood Citation2018; Michalowska Citation2015). This aspect is not considered in the present paper since, at the time of writing, the centers analyzed were either still at the planning stage (the Istanbul Center) or fully established as physical buildings (the Tokyo and Bursa Centers).

Theoretical orientation

From the existing literature on anticipatory governance and preparedness techniques, we have acquired detailed insights into the ways in which futures are made present through affects and materialities, as well as how affects are produced and mediated through sensory experience and atmosphere. In this paper, I wish to contribute to and advance these insights by shifting the empirical focus from typical organizational and professional settings, to a setting whose main purpose is to involve the public in security practices. Thinking of public simulation centers as a form of biopolitical technology – one that redeploys existing anticipatory techniques and put them to work in the field of public preparedness – it appears an important task to articulate the subtle shifts in relations between governments and populations that may (be assumed to) occur as a result of this process. The limited space allows for nothing more than a small attempt; however, drawing on the previous literature I will say a few words on this aspect in relation to this paper’s empirical basis. Furthermore, without making myself guilty of too much repetition, I will discuss briefly how architectural design and affect can function as elements constituting a technology for managing the governmental problem of creating a prepared and resilient public. Accordingly, in the present section I turn first to the shifting relations between governments and populations, and second, to the elements of architecture and affect.

Foucault (Citation2007) elucidated important aspects concerning the governmental use of technologies within the framework of biopolitical security. As a contemporary liberal response to societal problems, security is a positive or productive form of governing. Security does not aim to restrict the freedom of individuals. On the contrary, the unhindered circulation of people and things and the entrepreneurial self-sufficiency of individuals is the very foundation of security power. At the same time, governments need to avert or neutralize threats to the free circulation of individuals and things. Hence, citizens become involved in this effort as active co-producers of security. However, when thinking of public simulation centers, and their self-presentation on websites and in leaflets, their target audience (e.g. the public, visitors, participants, citizens) seems to consist of a merging of two entities: the individual and the population. Concretely, these centers are established to reach the population as a whole but are, reasonably, visited by specific groups (such as schoolchildren) and individuals. As noted by O’Grady (Citation2018, 89), there is a dynamic at play here between subject (the individual citizen) and object (the aggregation of individuals, the population, the public) since “it appears as if the pursuit of the object of governance is enacted through attempts to know the subject itself” (89). Foucault discusses this merging of the subject-object of governance in relation to sexuality (Citation2003) and societal unrest (Citation2007). In analogy with his discussion on sexuality, we may say that preparedness “exists at the point where body and population meet” (Foucault Citation2003, 251–252). Accordingly, when analyzing public preparedness, one have to take into account the dual perspective of individual and population.

Deville, Guggenheim, and Hrdličková (Citation2014) provide an example thereof in their study of concrete shelters. More precisely, they show how relations between governments and populations shift with the introduction of new shelter-building programs. In some countries, the state extends its reach by claiming responsibility for its citizens in relation to specific disasters (187), while in other countries, the state makes no such efforts, leaving the responsibility of shelters to the individual (190). Insisting that buildings can have a mediating effect on the relation between a state and its population, one may ask what kind of subjects are constituted simply by residing in different types of buildings. A shelter typically constitutes the target subject-object as vulnerable and in need of protection (Deville, Guggenheim, and Hrdličková Citation2014), while public simulation centers, by contrast, constitute the target subject-object as resilient and capable of protecting others aside from oneself. Much of what has been written on architecture, space, and spatial design from a Foucauldian perspective has centered on questions of symbolism, power, state control, and surveillance (Abramson et al. Citation2012; Huxley Citation2008; Piro Citation2008). However, from his Collège de France lectures and onwards, Foucault pursues a more complex discourse on these matters, which does not replace but supplements earlier discussions (Fontana-Giusti Citation2013). As noted by Schuilenburg and Peeters (Citation2018) there is a material-spatial aspect inherent in biopolitical security that can be articulated in terms of inclusion and exclusion. Strategies of exclusion involve measures for inhibiting circulation of people and things like, for example, guarded gateways, roadblocks, fences, and walls; that is, physical design intended to reduce people’s access to public and urban space (Schuilenburg and Peeters Citation2018, 2). In contrast, inclusive security enhances urban safety without reducing accessibility. To a lesser extent, strategies of inclusive security focus on measures such as defense and surveillance, and instead operates by “scripting the use of public space by designing in new defaults for behavior” (Schuilenburg and Peeters Citation2018, 2). Public simulation centers, accordingly, can be thought of as architectural renderings of inclusive security. In order to make sense of and articulate how affects emerge and mediate “preparedness” in the context of public simulation centers, I will now draw on existing literature to highlight a few important aspects, which may help us to formulate more precisely what is going on in the 72-hour experience and the debris corridor. The three aspects briefly considered below are: relations between affect and action; relations between affect and (im)materialities; and, the multitude of possible affects.

To paraphrase Kaufmann (Citation2016), public simulation centers can be studied as a governmental program that “affectively modulates a population’s relationship to emergencies” (103) and, thereby, opens up citizens to act in the face of unexpected events. In this Spinozian-Deleuzian-Massumian-influenced line of reasoning, affect is to be understood broadly as “the capacity of the body to effectuate change” (103) and as “the property of the active outcome of an encounter [that] takes the form of an increase or decrease in the ability of the body and mind alike to act” (Thrift Citation2004, 62). This potentiality of the body to act arises in the precise moment between an encounter (that is, some form of contact between individuals or between individuals and their immediate environment) and the reaction to that encounter. Affect, thereby, emerges as relational and inter-personal in the sense that our own affects depend on the nature of the external object or body that affected us, just as external bodies may be affected by us as well (Kraftl and Adey Citation2008, 215).

Moreover, affects emerge in relation to materialities and non-material sensory impressions. This is particularly clear in the simulated post-earthquake environment of the 72-hour experience and the debris corridor. In the simulation, the affectual experience of being there, in the midst of emergency, is produced through an assemblage of construction materials, objects and props, moving images on television screens, and other audiovisual effects. As noted by Anderson and Adey (Citation2011, 1102–1103), visual and audio materials are part of staging the site of the simulation, by expressing specific affective qualities normally connected to urgency and peril. O’Grady (Citation2016) talks of these materials and techniques in terms of esthetics, referring to both “the set of techniques through which different events can be rendered, imagined and experienced” and “how such events are produced through and beheld upon sensual registers” (O’Grady Citation2016, 496).

From previous studies, we know that the affectual reactions produced in emergency simulations can be completely different from those intended. Preparedness exercises may produce stress, fear, and anxiety, as well as boredom, fascination, or joy (Anderson and Adey Citation2011; Anderson Citation2015). According to Kaufmann (Citation2016), affect is a pre-conscious incitement, which may lead to different kinds of actions and emotional responses in different individuals (103). In line with this, Anderson (Citation2015) has observed that “affective effects can never be guaranteed in advance” (273). Accordingly, public simulation centers may strive to reach “the whole population” as a homogeneous unit, assumed to experience more or less identical affects in the simulation, when, in fact, it is individuals who participate, with their individual affective experiences, and their individual responses.

Governing through architecture and affect

Now, let us return to the empirical material to look in more detail into some of the ways in which security affects emerge in public simulation centers, and with what material and immaterial means these centers attract and involve citizens in security practices. Following this introductory note, the remaining section will be structured into two subsections, each elaborating on a salient aspect of this paper’s theme. In the first subsection, I describe a set of affectual experiences that, together, are assumed to bring into the present a sense of future emergency. This part of the analysis builds on fieldwork and participant observation in the Tokyo and Bursa Centers. Accordingly, descriptions of situations, including examples of how affects emerge in this setting, are taken from my fieldnotes. The affects encountered in the simulation turned out to be “typical” security affects in the sense that they are supposed to operate on a negative register to make people act in the face of unexpected events (Kaufmann Citation2016, 103). In the second subsection, I describe how we, through affectual experiences emerging in encounters with architectural design, are assumed to feel incited and invited to visit public simulation centers. This part of the analysis builds on a selection of architectural sketches and descriptions regarding the planned Istanbul Center. The analysis, thus, moves from the inner workings of the center itself and outwards, to involve the exterior environment. Implicitly throughout both subsections, I reflect on how visitors may perceive the emergency futures presented to them, and how these particular futures are (assumed to be) acted on in the present.

The will to affect

Analysis of the empirical material uncovered three principal affects that are produced and mediated within the context of the 72-hour experience and the debris corridor, namely: stress, surprise, and vigilance. As noted previously, these are typical (negative) security affects in the sense that they have been described in previous studies as exerting a negative incitement or pressure to act. Hence, future studies may perhaps be able to demonstrate other, positively charged, affects in similar settings. Stress is the first affective condition you encounter at the Tokyo Center. Upon entering, you are placed by personnel in a mock elevator, descending from the tenth floor of a terminal station building. Suddenly, the elevator starts to twitch and the lights go out. The long-feared earthquake, the Big One, has suddenly hit Tokyo. Accompanying children, even though they understand that this is fake, seem to be genuinely scared by the simulation. Stress, accordingly, emerge in this situation as a an affectual experience originating, in part, from the inter-personal relations among participants (Kraftl and Adey Citation2008, 215), and, in part, from relations between individuals and their material surrounding (for example, a non-functioning elevator). Finally, down on the ground floor, we evacuate at a slow pace, crouching our way out of the building with the help of emergency exit signs and fluorescent stripes on the floor. Outside, we find ourselves on a devastated downtown street. Personnel acting as emergency workers (see above) gather the group and, using a megaphone, tell us about the disaster. Behind the emergency worker, a brick wall gradually cracks. The whole building seems to be about to collapse on top of a car unfortunately parked in front of the house. The second affective condition encountered in the simulation is that of surprise. We, a random mix of participants, are scattered along the street, each of us immersed in the havoc induced by the earthquake. On its official website, the Tokyo Center presents the 72-hour experience as a “diorama”, and I have therefore expected the scene to be static. However, as I raise my eyes towards a facade, I realize that this is more than the frozen time–space of a diorama. Things actually happen here: an air-conditioner suddenly comes off its attachment, in another building, the interior seems to have caught fire. Red flames and smoke can be glimpsed behind the curtains of display windows. Surprises such as these are staged to open up my awareness to the risks caused by the disaster. The affectual experience of surprise thus emerge from relations between myself and the material and immaterial elements, or esthetics, that are part of staging the site of the simulation (Anderson and Adey Citation2011; O’Grady Citation2016). The third affective condition is that of attentiveness or vigilance. Again, this affectual condition emerges in relations among people, and between people and things. This is illustrated by the following two examples from the debris corridor in the Bursa Center: (First) suddenly, the instructor makes a halt in front of the car sales (referred to in the paper’s opening vignette), quietly turning my attention to the diversity of impending dangers: the car, the advertising sign about to slide down, the crumbling building, the torn electric wire … The man stuck under the car is in immediate danger of being hit by the falling objects and must be brought to safety. I tell the instructor that the best thing to do here is calling for help so that several people can join forces and get the car out of the way. “Quite right” he says with a serious face, “but first … ”: He points at the electric wire cutting through the scene. Without words, he shows me how to remove the wire using some non-conductive material, like a piece of wood or a rubber tire, before helping the injured person. (Second) at the farther end of the alley, a desperate cry for help sounds from somewhere underneath a huge pile of concrete and steel. The scene invites us to imagine a woman trapped in the rubble. In the present situation, attention is focused on the audible rather than the visual. The immediate threat (of being crushed or suffocated) is out of frame, and the imaginative action goes on in a negative space, inaccessible from my current position. Accordingly, the scene aims to enhance my vigilance and, thus, to make me observant and ready for things that cannot be perceived directly by sight.

The will to attract

Moving from the interior environment of public simulation centers to their exterior, I would now like to shift focus from the production and mediation of affect within these facilities to the affective experiences emerging in relation to the facilities as buildings, or articulations of architectural design. Public simulation centers make use of their material appearances, including their exterior environments, to attract visitors. This is particularly obvious at the Tokyo Center. Adjacent to the Tokyo Center is a large public park that, according to two leaflets about the center, serves a dual purpose:

When a major earthquake or other disasters occur in the Tokyo metropolitan area […] the entire park will function as the command headquarters. During normal times, the park offers a large space perfect for various usages from resting and relaxing to doing light exercises and picnics. (Tokyo Rinkai leaflet Citation2021a)

These “disaster prevention parks” are important open spaces to save our lives in the event of an earthquake disaster. But most of the time they show their other face as Metropolitan parks that make our cities pleasant and stately and give us the places for relaxation and recreation. (Tokyo Rinkai leaflet Citation2021b)

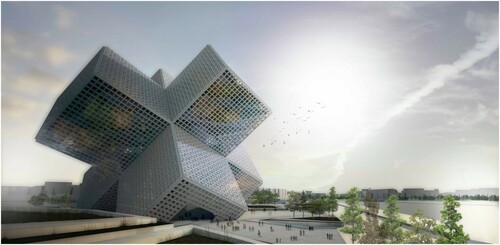

Among the design proposals, the will to attract visitors is articulated in various ways. A recurring theme linked to the above discussion is that of the prospective facility’s geographic placement and social function within the wider context of Istanbul’s urban space. Apparently, to attract visitors to the facility, the Portugal-based architectural firm OODA aims to satisfy not only the formal criteria stated in the Competition Brief and Conditions (ThyssenKrupp Citation2011, 4) but also a number of informal ones. As stated in their proposal:

Conceptually, the building ( below) assumes its own identity on the city and stands as a new-age landmark that captivates tourists to its content and also attracts all the local people in case of real natural disaster in Istanbul having the new landscape the ability to become a major emergency shelter – earthquake or flood – and the building to work as a guiding focal reference. (Furuto Citation2011a)

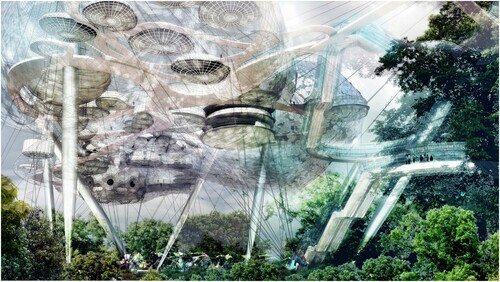

“Inhabiting the sky” ( below) introduces a new concept to understand the “welcome” area of a public space, creating not a park, nor a public square, but a new kind of space where nature−human and technology works together to build up an atmosphere really authentic and related to the subject that is presented in the center. (Furuto Citation2011b)

Conclusion: governing anticipation

In this paper, I explored how public simulation centers work to enhance preparedness in citizens through affectual experiences and architectural design. These centers present themselves as a physical environment, a “place to visit”, intended to stimulate security practices in a positive way. Simultaneously, they do not merely target specific groups “in need” but reach out to whole populations as a biosocial entity. Hence, these centers constitute positive spaces of security that operate through strategies of inclusion. Nevertheless, due to the contemporary tendencies of neoliberal city branding and the commercialization of public space, the possibility remains that some groups in society will experience themselves as more or less excluded from these centers. The analysis highlighted these centers’ use of their material appearance, including their exterior environments, and their use of affective experiences, as technologies for governing citizens’ improvement of their own skills and knowledge in terms of disaster preparedness and response. From the perspective of the exterior, these centers strive to attract visitors through affective experiences typically valued positively. The material appearance of the buildings contributes to feelings of curiosity and fascination, and the exterior environment presents itself as a public space intended for recreation, relaxation, and socializing. From the perspective of the interior, these centers aim to produce a dynamic set of affective states in visitors in order to facilitate action, readiness, and capacity to respond in an emergency. The centers are marketed as spaces of edutainment and pleasure; however, for the 72-hour experience and the debris corridor, the most significant affects were those of stress, surprise and vigilance. Together, the elements of architecture and affect constitute a biopolitical technology for enhancing the resilience of populations.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Ridvan Bilgin and the staff at Bursa Valiliği Afet Eğitim Merkezi, and to Mikiko Kashiwagi at the Japan International Cooperation Agency, for their generous assistance during my stay in Bursa. I am also grateful to architectural firms OODA, Leon11, and CRAB studio for letting me reproduce their images. I thank Anna Olofsson for her comments on an early draft. Finally, I thank the reviewers for their insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mikael Linnell

Mikael Linnell is a lecturer in sociology at Mid Sweden University and an associate of the Risk and Crisis Research Centre based in Östersund, Sweden. His current research focuses on the production of anticipatory knowledge for disaster preparedness.

Notes

1 Lakoff and Collier (Citation2010, 244) define the term political technology as “a systematic relation of knowledge and intervention applied to a problem of collective life. In this case, the political technology of preparedness responds to the governmental problem of planning for unpredictable but potentially catastrophic events”.

2 Similar existing centers not included in the research are the Boramae Safety Experience Center, the Daegu Safety Theme Park, and the Gwangnaru Safety Experience Center in South Korea, and the Chengdu Disaster Preparedness Learning Center in China.

3 The basic idea of sensory ethnography is to “rethink ethnography through the senses” (Pink Citation2015, 6), to “self-consciously and reflexively attend to the senses throughout the research process” (Pink Citation2015, 7). This means that, when engaging in participant observation, I was at the same time engaged in self-observation, carefully noting my own experiences, actions and reactions for further grounding the interpretation of the observed (Flick Citation2006, 216).

References

- Abramson, D., A. Dutta, T. Hyde, and J. Massey for Aggregate. 2012. Governing by Design: Architecture, Economy, and Politics in the Twentieth Century. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Adey, P. 2014. “Security Atmospheres or the Crystallization of Worlds.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32: 834–851.

- Adey, P., and B. Anderson. 2012. “Anticipating Emergencies: Technologies of Preparedness and the Matter of Security.” Security Dialogue 43: 99–117.

- Adey, P., B. Anderson, and S. Graham. 2015. “Introduction: Governing Emergencies: Beyond Exceptionality.” Theory, Culture & Society 32: 3–17.

- Anderson, B. 2010. “Preemption, Precaution, Preparedness: Anticipatory Action and Future Geographies.” Progress in Human Geography 34: 777–798.

- Anderson, B. 2014. Encountering Affect: Capacities, Apparatuses, Conditions. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

- Anderson, B. 2015. “Boredom, Excitement and Other Security Affects.” Dialogues in Human Geography 5: 271–274.

- Anderson, B., and P. Adey. 2011. “Affect and Security: Exercising Emergency in ‘UK Civil Contingencies’.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29: 1092–1109.

- Anderson, B., and P. Adey. 2012. “Governing Events and Life: ‘Emergency’ in UK Civil Contingencies.” Political Geography 31: 24–33.

- Aradau, C. 2010. “The Myth of Preparedness.” Radical Philosophy 161: 1–6.

- Aradau, C., and R. van Munster. 2012. “The Time/Space of Preparedness: Anticipating the ‘Next Terrorist Attack’.” Space and Culture 15: 98–109.

- Aradau, C., and R. van Munster. 2013. Politics of Catastrophe: Genealogies of the Unknown. London: Routledge.

- Archiscene. 2012. “Disaster Prevention and Education Center by Group8”. Archiscene, January 17, 2011. Accessed 8 April 2021. https://www.archdaily.com/189937/disaster-prevention-and-education-center-leon11.

- Balke, J., P. Reuber, and G. Wood. 2018. “Iconic Architecture and Place-Specific Neoliberal Governmentality: Insights from Hamburg’s Elbe Philharmonic Hall.” Urban Studies 55: 997–1012.

- Bruno, G. 2002. Atlas of Emotion. Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film. New York: Verso.

- Bursa Disaster Training Center. 2021. “Bursa Afet Eğitim Merkezi”. Accessed 8 April 2021. https://baem.business.site/.

- Cabinet Office, Japan. 2015. “White Paper on Disaster Management in Japan.” Government of Japan.

- Collier, S. 2008. “Enacting Catastrophe: Preparedness, Insurance, Budgetary Rationalization.” Economy and Society 37: 224–250.

- Collier, S., and A. Lakoff. 2008. “Distributed Preparedness: The Spatial Logic of Domestic Security in the United States.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26: 7–28.

- Collier, S., and A. Lakoff. 2015. “Vital Systems Security: Reflexive Biopolitics and the Government of Emergency.” Theory, Culture & Society 32: 19–51.

- Davis, T. C. 2007. Stages of Emergency. Cold War Nuclear Civil Defence. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Deville, J., M. Guggenheim, and Z. Hrdličková. 2014. “Concrete Governmentality: Shelters and the Transformation of Preparedness.” The Sociological Review 62 (S1): 183–210.

- DHS. 2006. Civil Defence and Homeland Security: A Short History of National Preparedness Efforts. Dep. of Homeland Security, National Preparedness Task Force. Washington: DHS.

- DRI. 2021. “Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution” (DRI). Accessed 8 April 2021. https://www.dri.ne.jp/en.

- Flick, U. 2006. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Fontana-Giusti, G. 2013. Foucault for Architects. London: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. 2003. “Society Must Be Defended”. Lectures at the Collège de France 1975–1976, edited by M. Bertani and A. Fontana. New York: Picador.

- Foucault, M. 2007. Security, Territory, Population. Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978, edited by M. Senellart. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Furuto, A. 2011a. “Disaster Prevention and Education Center / OODA”. ArchDaily, December 4. Accessed 8 April 2021. https://www.archdaily.com/189063/disaster-prevention-and-education-center-ooda.

- Furuto, A. 2011b. “Disaster Prevention and Education Center / Leon11”. ArchDaily, December 7. Accessed 8 April 2021. https://www.archdaily.com/189937/disaster-prevention-and-education-center-leon11.

- Grosz, E. 2001. Architecture from the Outside: Essays on Virtual and Real Space. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Grozdanic, L. 2012. “Earthquake Disaster Prevention Center in Istanbul / CRAB Studio”. eVolo, September 13. Accessed 8 April 2021. http://www.evolo.us/earthquake-disaster-prevention-center-in-istanbul-crab-studio/.

- Grubbauer, M. 2014. “Architecture, Economic Imaginaries and Urban Politics: The Office Tower as Socially Classifying Device.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38: 336–359.

- Güvencem. 2021a. “Deprem enkaz koridoru”. Accessed 8 April 2021. https://www.afetegitimmerkezi.com/deprem-enkaz-koridoru.html.

- Güvencem. 2021b. “Natural Disaster Simulation”. Accessed 8 April 2021. https://www.afetegitimmerkezi.com/natural-disaster-simulation.html.

- Huxley, M. 2008. “Space and Government: Governmentality and Geography.” Geography Compass 2: 1635–1658.

- Kaufmann, M. 2016. “Exercising Emergencies: Resilience, Affect and Acting Out Security.” Security Dialogue 47: 99–116.

- Kraftl, P., and P. Adey. 2008. “Architecture/Affect/Inhabitation: Geographies of Being-in Buildings.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98: 213–231.

- Lakoff, A. 2007. “Preparing for the Next Emergency.” Public Culture 19: 247–271.

- Lakoff, A. 2017. Unprepared. Global Health in a Time of Emergency. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Lakoff, A., and S. Collier. 2010. “Infrastructure and Event: The Political Technology of Preparedness.” In Political Matter, Democracy Technoscience, and Public Life, edited by B. Braun and S. Whatmore, 243–266. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press.

- Leder Mackley, K., and S. Pink. 2013. “From Emplaced Knowing to Interdisciplinary Knowledge: Sensory Ethnography in Energy Research.” The Senses and Society 8: 335–353.

- Meta, A. 2011. “Istanbul Disaster Prevention and Education Centre: Winner of the 12th ThyssenKrupp Elevator Architecture Award”. Blogpost on Design4Disaster, April 6. Accessed 8 April 2021. https://www.design4disaster.org/2011/04/06/xii-thyssenkrupp-elevator-architecture-award/.

- Michalowska, M. 2015. “Digital Utopias and Real Cities – Computer-Generated Images in Re-design of Public Space.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 7: 1–11.

- Milne, D. 1981. “Architecture, Politics and the Public Realm.” Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory 5: 131–146.

- Murata, M. 2005. “Establishment of the Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution.” In Disaster Reduction and Human security, edited by R. Shaw and B. Rouhban, 106–107. UNESCO and Kyoto University.

- Nishikawa, S., and H. Yukinari. 2015. “Institutionalizing and Sharing the Culture of Prevention. The Japanese Experience.” In Disaster Risk Reduction for Economic Growth and Livelihood. Investing in Resilience and Development, edited by I. Davis, K. Yanagisawa, and K. Georgieva, 111–138. Oxon: Routledge.

- O’Grady, N. 2016. “Protocol and the Post-human Performativity of Security Techniques.” Cultural Geographies 23: 495–510.

- O’Grady, N. 2018. Governing Future Emergencies. Lived Relations to Risk in the UK Fire and Rescue Service. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- O’Malley, P. 2013. “Uncertain Governance and Resilient Subjects in the Risk Society.” Oñati Socio-Legal Series 3: 180–195.

- Pink, S. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Piro, J. 2008. “Foucault and the Architecture of Surveillance: creating Regimes of Power in Schools, Shrines, and Society.” Educational Studies 44: 30–46.

- Samimian-Darash, L. 2016. “Practicing Uncertainty: Scenario-based Preparedness Exercises in Israel.” Cultural Anthropology 31: 359–386.

- Samimian-Darash, L., and P. Rabinow. 2015. Modes of Uncertainty. Anthropological Cases. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Schuilenburg, M., and R. Peeters. 2018. “Smart Cities and the Architecture of Security: Pastoral Power and the Scripted Design of Public Space.” City, Territory and Architecture 5: 1–9.

- Shiner, L. 2011. “On Aesthetics and Function in Architecture: The Case of the ‘Spectacle’ Art Museum.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 69: 31–41.

- Tamari, T. 2019. “Star Architects, Urban Spectacles, and Global Brands: Exploring The Case of the Tokyo Olympics 2020.” International Journal of Japanese Sociology 28: 45–63.

- Thrift, N. 2004. “Intensities of Feeling: Towards a Spatial Politics of Affect.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 86: 57–78.

- Thrift, N. 2008. Non-representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect. London: Routledge.

- ThyssenKrupp. 2011. XII ThyssenKrupp Elevator Architecture Award. Istanbul Disaster Prevention and Education Centre, Istanbul. Competition Brief and Conditions. ThyssenKrupp and the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Department of Projects.

- Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park. 2021a. “General Introduction”. Accessed 8 April 2021. http://www.tokyorinkai-koen.jp/en/.

- Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park. 2021b. “1F Experience Center”. Accessed 8 April 2021. http://www.tokyorinkai-koen.jp/en/1f/.

- Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park. 2021c. “About the Park”. Accessed 8 April 2021. http://www.tokyorinkai-koen.jp/en/about/.

- Tokyo Rinkai leaflet. 2021a. Accessed 8 April 2021. http://www.tokyorinkai-koen.jp/pdf/pamphlet_en_2.pdf.

- Tokyo Rinkai leaflet. 2021b. Accessed 8 April 2021. http://www.kensetsu.metro.tokyo.jp/content/000007607.pdf.

- Webber, P. 2001. “The Public Space and the Monuments of the City.” Architectural Theory Review 6: 95–106.