ABSTRACT

The study of pet cemeteries has recently intensified in multiple disciplines. However, the focus of this research has been more on the interpretation of information available on grave markers, while only touching on the geographical context, the land use zone of these sites. The advantages of focusing on the broader context are shown here through a case study focusing on the Hiironen pet cemetery in the city of Oulu in northern Finland. First, by combining a variety of sources – archival documents, photographs, maps, and news reports – with field documentation, a contextual site history extending both before and after the official period of use of the pet cemetery (1971–1993) is established. This history mirrors temporal changes in societal values regarding human-companion animal relations. By defining and examining these changes, the current notion of the increasing status of present-day companion animals as dear family members is confirmed.

Introduction

Modern human-companion animal relations are increasingly attracting scholarship, as pets are today considered (liminal) family members in modern Western cultures (e.g. Ambros Citation2010, 310; Auster, Auster-Gussman, and Carlson Citation2020, 263–264). As part of this trend, the death of a companion animal has been studied from various perspectives. In urban westernized societies, this final stage of human-companion animal relationships is displayed in pet cemeteries, which have also attracted a fair amount of scholarship in recent decades.

However, pet cemetery studies have from the outset tended to focus on grave markers, and tended to employ qualitative methods (e.g. Brandes Citation2009; Kean Citation2013; Schuurman and Redmalm Citation2019). In some studies, attention is paid to specific features associated with grave markers, such as snapshots put on display in Japanese pet burials (Chalfen Citation2003). Others have focused on the remembrance of a single animal species like cats (Gustavsson Citation2011, 106–122), donkeys (Williams Citation2011), or horses (Äikäs, Ikäheimo, and Leinonen Citation2021). Yet only recently have the first quantitative analyses, based on systematic documentation of grave markers in a given pet cemetery or pet cemeteries, appeared (e.g. Bardina Citation2017; Auster, Auster-Gussman, and Carlson Citation2020; Tourigny Citation2020). Less attention has been paid to the broader context of grave markers, which may equally represent a source of rich spatio-temporal data.

This argument applies both to the immediate contiguous zone around the grave markers and the surrounding land use zone (for zoning, see Zeigler Citation2015, 649–650). To underline this point, the present paper will focus on “the acreage set aside for the burial or entombment of the dead” (Zeigler Citation2015, 650) known as the land use zone. We propose that when understood as an entity, a pet cemetery can be examined as a geographical element that is part of a broader pattern of land use and, urban growth, similar to the way that human cemeteries have been analyzed (e.g. Harvey Citation2006). From this perspective, the place allocated for a pet cemetery, as well as its ever-changing relation to other human-induced elements in the urban environment like suburbs, roads, industrial zones, and recreational areas, can reveal societal attitudes concerning the burial of companion animals, whereas individual pet burials with their grave markers can be seen as expressing emotions at a personal or family level.

However, exactly like human cemeteries (Pattison Citation1955, 245), many pet cemeteries were established before site location became the subject of national legislation or municipal control. Spiegelman and Kastenbaum (Citation1990) have discussed the relationship of a pet cemetery to urban development. But later research has focused on the motives behind the establishment of pet cemeteries (Pregowski Citation2016; Bardina Citation2017), and the geographical context in which the site was established is usually only touched on (see, however, Brandes Citation2009 for an exception), Yet the topic is frequently raised in papers discussing three historic and archetypal pet cemeteries (e.g. Gaillemin Citation2009; Kean Citation2013, 22–25; Mangum Citation2007): The London Hyde Park Dog Cemetery (1880); the Hartsdale Pet Cemetery (1896) in Westchester County, New York; and the Cimetière des Chiens in Asnières-sur-Seine (1899) in Paris.

In addition, Ambros (Citation2010) has mapped and studied the exclusion and inclusion of pet burial spaces in the human necral landscapes of Japan (see also Kenney Citation2004), although the principal focus of the article was on the internal division of space in mortuary spaces containing both human and animal burials. Although state and municipal legislation regarding pet cemeteries in the US has recently been reviewed by Gross and Salkin (Citation2020), their paper does not contain much case-based information about the actual location of pet cemeteries in relation to other elements in an urban or rural environment. This comment also holds true with the newest archaeological take on the subject by Tourigny (Citation2020), who used gravestone data gathered from four different British pet cemeteries in an exemplary manner to establish long-term developments in their textual and visual information content.

To strengthen the argument that the importance of pet cemeteries extends well beyond epitaphs carved on grave markers and the artifacts that adorn them, this paper presents a case study with several aims. First, it illustrates the reciprocal societal impact – the effect of urban development on pet cemeteries and vice versa – these places have during different stages of their use-life, extending from the planning of the site to the cessation of new burials and beyond. This implies that even if the official maintenance of a pet cemetery ceases and it falls into neglect, these seemingly abandoned places may still be the focus of various human activities and emotions.

Second, it contextualizes and analyzes the locations allocated for pet cemeteries in order to extend the “pets are increasingly seen as humans” argument from the individual to societal level. The article therefore belongs to the field of “necrogeography” first defined by Kniffen (Citation1967) in his short but seminal take on the topic of the geographical study of burial practices. Recently, necrogeography has been revisited and redefined by Nash (Citation2018), who advocates for the study of changes in the physical location of cemeteries with a combination of human and physical geography (Nash Citation2018, 557–560). From this standpoint, the scope of animal necrogeography is to study the values and appreciation given to human-companion animal relations and to the places of burial as markers of these relations. These relations are naturally subjected to considerable spatio-temporal variation depending on the culture and the point in time. In modern western societies, for instance, human cemeteries are traditionally comprehended as sacred resting places for the deceased, while the idea about the sacredness of pet cemeteries has really gained ground only in this millennium.

Bearing what has been stated above in mind, the remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First, a concise literature review outlining the multifaceted significance of cemeteries in westernized societies will be presented in the light of recent cultural geography research. Here, the arguments have been derived mainly from the research concerning human cemeteries, but since pets are increasingly treated as surrogate humans, most often as small children (e.g. Ambros Citation2010, 306), the ideas and emotions felt toward “conventional” cemeteries are inevitably projected onto them as well. This argument is further strengthened by the reciprocity of influences, as cherub statuettes and other trinkets formerly seen only in pet cemeteries have recently found their way into human memorials, especially those for children, in ordinary cemeteries.

After the literature review, the case selected for this study – the Hiironen pet cemetery in Oulu, northern Finland – is introduced, with arguments supporting its selection. A description of the various sources of information used in the reconstruction of the site’s history follows. Next, the site’s history is laid out in three sub-chapters from the necrogeographic perspective, outlining the areal development before, during, and after the active use of the Hiironen pet cemetery. This is followed by a discussion containing case-specific interpretations, as well as the wider implications of the observations. Finally, the main findings of the research are reviewed in the conclusions.

Literature review

Cemeteries represent ambivalent spaces in the postmodern world, because as places they are understood by urbanized western societies as both sacred and secular, as well as public and private. Yet in the traditional view, they are more than anything else places reserved for individuals and groups to mourn their loved ones – both humans and animals – besides also being important places of contemplation and commemoration (Swensen, Nordh, and Brendalsmo Citation2016, 47). For any society, a cemetery represents continuity and a sense of belonging to a place (Swensen, Nordh, and Brendalsmo Citation2016, 42). The notions of life and death evoked by graves and grave monuments can also strengthen the idea of the sacredness of place that is not necessarily related to religious views. This is also evident in ideas concerning appropriate behavior in cemeteries (Swensen, Nordh, and Brendalsmo Citation2016, 43; Skår, Nordh, and Swensen Citation2018). As some people see cemeteries solely as places of internment, mourning, and memorialization, they consider other kinds of use, especially recreational activities, inappropriate (Evensen, Nordh, and Skaar Citation2017, 77, 83; Quinton and Duinker Citation2019, 255). These attitudes have thus far been studied in human cemeteries, but they may be reflected in pet cemeteries, which are used in a similar fashion (Äikäs, Ikäheimo, and Leinonen Citation2021).

For other people in urbanized western societies, religious aspects of cemeteries are clearly of secondary importance to recreational activities associated with a pleasant green area (Swensen, Nordh, and Brendalsmo Citation2016). Cemeteries are valued today both as urban wildlife habitats and as areas for individual and social recreation (Harvey Citation2006, 298) – they represent a retreat for both humans and animals, and create a dynamic ecological context by creating habitats for life among death, for example, for flies inhabiting rotten wood (Gandy Citation2019). Not only have modern urbanites found cemeteries suitable for exercise, photography, the enjoyment of nature, education and history, relaxation and restoration, dog walking, and the exploration of cultural heritage, but also for somewhat more objectionable purposes like drinking, drug use, and romantic pursuits (Swensen, Nordh, and Brendalsmo Citation2016, 45; Evensen, Nordh, and Skaar Citation2017; Quinton and Duinker Citation2019, 256; Quinton et al. Citation2020). In all, cemeteries can be described as multidimensional landscapes that are loaded with the potential for conflict stemming from the different needs of their users (Woodthorpe Citation2011; Evensen, Nordh, and Skaar Citation2017, 82).

However, while cemeteries are primarily created as final resting places for the deceased, their meaning does not remain static over the years (Rugg Citation2000; Quinton et al. Citation2020). Both human and pet cemeteries can also have values related to history, scenery, and ecology, for example. Cemeteries can gain historical and cultural value with time. Older cemeteries in particular are primarily seen as heritage sites replete with history (Swensen, Nordh, and Brendalsmo Citation2016), and they may be understood as relics in their own right (Lowenthal Citation1979, 123). As sacred places, cemeteries are unlikely to be targeted for redevelopment, but in some cases, the needs of the living and urban development override respect for the dead (e.g. Basmajian and Coutts Citation2010; Chung Ho Citation2018; Puzdrakiewicz Citation2020).

Davies and Bennett (Citation2016) have observed that neglected cemeteries may adhere to minimal maintenance, declining community visitation and value, and heritage value maintained by committed community groups, and their management may fall to public officials. They suggest that cemetery reuse, particularly for sites at capacity and in their neglected phase, could provide an option for land-use planners, providing there is public support and a provision for the exhumation and relocation of graves and memorials. Unfortunately, such activity has been quite common around the Western world in towns and cities, where developers have “forgotten” the existence of a cemetery, especially those used for the burial of ethnic and other disadvantaged groups such as mental asylum patients.

Puzdrakiewicz (Citation2020) has studied the reuse of abandoned cemeteries in Gdańsk, Poland, where he noted that they were usually converted into parks or areas with multiple functions, including housing as well as service and production facilities. Some changes could be quite radical – the conversion of the site of a former cemetery into a bus station or a storage area for industrial materials, for example. Some of these areas still included burial-related structures or monuments commemorating the former cemetery, whereas in others, the old cemetery had disappeared without a trace. Cemeteries also provide open spaces as a respite from the urban monotony of the built environment (Harvey Citation2006, 295‒296). In a poll conducted as a part of Puzdrakiewicz’s (Citation2020) study, an afterlife as a green area was seen by many as the most acceptable use for an old cemetery.

Indeed, in recent years, several researchers have studied cemeteries as green urban spaces that enable various recreational activities (Harvey Citation2006; Swensen, Nordh, and Brendalsmo Citation2016; Evensen, Nordh, and Skaar Citation2017; Skår, Nordh, and Swensen Citation2018; Lai et al. Citation2020; Quinton and Duinker Citation2019; Quinton et al. Citation2020; Quinton, Östberg, and Duinker Citation2020a). These green spaces, as defined by Taylor and Hochuli (Citation2017), constitute either water bodies and vegetated areas in a landscape, or open spaces with urban vegetation. Because cemeteries are inherently such spaces, it is not difficult to understand why scholars like Lai et al. (Citation2020) have recently called for the optimization of their use as passive green areas, in which cultural and spiritual values are intertwined with environmental values (Quinton, Östberg, and Duinker Citation2020b).

In extreme cases, the need for green spaces has led to the creation of cemetery forests. They are special places that are neither subjected urban planning nor are they typically managed as part of the urban forest. Research from Scotland, Sweden, and Finland has highlighted the value of urban forests in relation to stress-release, perceived restorativeness, improved health and wellbeing, beauty, recreation opportunities, and biodiversity support (e.g. Hauru et al. Citation2012; Lai et al. Citation2020; Quinton et al. Citation2020; Quinton, Östberg, and Duinker Citation2020b). While the plenitude of trees certainly contributes to a peaceful and restorative atmosphere, cemeteries as multipurpose green areas and the reuse of existing burial sites can resolve the potential problems stemming from the reservation of urban land for the deceased (Basmajian and Coutts Citation2010). It is therefore hardly surprising that the idea of urban green cemeteries as a public green space for town dwellers (Skår, Nordh, and Swensen Citation2018) is currently gaining popularity.

As the main body of the literature discussed above has been written from the point of human cemeteries, the question whether or to what extent these issues are relevant with pet cemeteries, particularly neglected ones, is well worth examining. Not only does such study bring additional value to the scholarship on cemeteries and burial grounds, but also suggests a fruitful way to approach pet cemeteries from societal perspective. The following case from northern Finland does this by showing that when properly interpreted in geographic context, the different stages constituting the site biography of a pet cemetery – establishment, maintenance and neglect – offer a viable way to document and examine temporal changes in human-companion animal relations.

Materials and methods

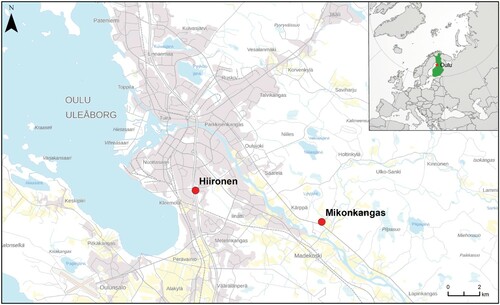

Since no centralized registry is kept on pet cemeteries in Finland, a Nordic country with approximately 5.5 million inhabitants, their number must be approximated. The Health Protection Act (1994/763) states that, in theory, each of Finland’s 310 municipalities must assign a place or means for the disposal of dead animals. Yet in real life, many pet cemeteries serve several municipalities and towns, and many are maintained by animal protection societies or pet cremation and burial services instead of a municipality. An extensive and systematic online search performed on the websites of these entities found information on 105 pet cemeteries, the majority of which were still in active use. Only about ten had been destroyed or had fallen into neglect for various reasons. One such neglected pet cemetery stands out regarding the scope of this paper. The Hiironen pet cemetery () is the older of the two pet cemeteries in the city of Oulu. This relatively small coastal town of approximately 200,000 inhabitants, boasting an economy based on business, versatile industries, and services, is by the Bothnian Bay in northern Finland.

Figure 1. The location of Finland, the city of Oulu and the sites mentioned in the text. Map sources: primary – National Land Survey of Finland. License: CC BY 4.0; inset – Wikipedia, Finland (orthographic projection). License: CC 1.0 Universal.

Figure 2. A view of the Hiironen pet cemetery taken from its southeastern corner. Photo: Janne Ikäheimo.

Figure 3. A panoramic aerial view towards the north shows the relation of the site to the downtown Oulu and suburban development. Photo: Janne Ikäheimo.

The Hiironen pet cemetery officially operated between 1971 and 1993, but companion animals were informally buried at the site both before its inauguration and following its official closure for nearly three decades. Over the past 50 years, both the pet cemetery and its surroundings have been transformed through various human activities. These changes can be traced by combining the information provided by various types of documents with features still visible at the site, as well as in the surrounding landscape. The variety and richness of the sources available enable the examination of the theme of this paper in a way that is not necessarily possible with every pet cemetery.

The following discussion is based primarily on archival material, including both official documents stored in the city of Oulu central archives and the rather unorganized collection comprising the archive of OSEY – Oulun Seudun Eläinsuojeluyhdistys ry (Society for the Protection of Animals of the Oulu District) – the authority once responsible for the maintenance of the Hiironen pet cemetery. The latter archive includes a scrapbook of newspaper clippings, for most of which neither the source nor the date of publication has been recorded. They will therefore be discussed in this article without citing appropriate reference data. In particular, the rare newspaper articles written about the Hiironen pet cemetery are of the utmost importance as source material for the actions that once took place at the site, as they offer snapshots of its intended and unintended use. On such occasions, the media frequently interviewed various city functionaries, whose views represented the official take on the pet cemetery.

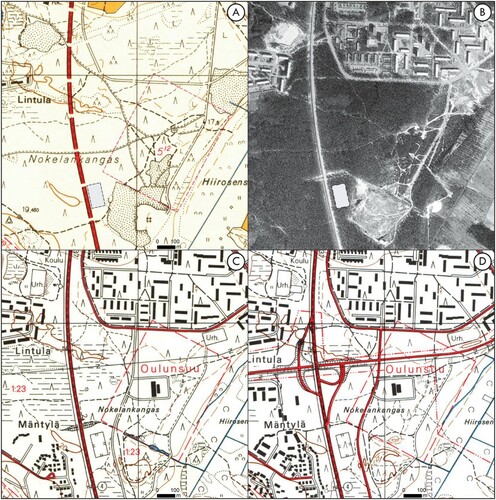

To fully grasp the location and the setting of a cemetery, it is also essential to understand the area’s history before the site itself was established. Fortunately, the area of the Hiironen pet cemetery appears in several aerial photographs, starting in the early 1930s ( and b). The first 1:20,000 scale basic map compiled by the National Land Survey in 1953 with its four updates () is also crucial for the inquiry. Map resources of minor relevance include various soil and bedrock maps released by the Geological Survey of Finland. Airborne laser-scanning data distributed by the National Land Survey (tile R4414A1) with 0.5/m2 point density has also been consulted for a better understanding of the local topography.

Figure 4. An aerial photograph taken in 1939, with the future location of the Hiironen pet cemetery. Map source: City of Oulu. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5. The location of the Hiironen pet cemetery on basic maps and aerial photograph of (a) 1965, (b) 1971, (c) 1981 and (d) 1989. Map and photo source: National Land Survey of Finland. License: CC BY 4.0.

Finally, these documentary sources are complemented by direct field observations, consisting mainly of notes, photographs, and positioning data, gathered during dozens of visits to the Hiironen pet cemetery between 2016 and 2021. While the primary purpose of these visits has been data collection about the layout of the pet cemetery, the evolving relationship of the site to other forms of urban land use in the area has also been monitored and documented using the methods described above.

The Hiironen pet cemetery – a concise history

From a vast forest into a wasteland

To fully grasp the environment in which the Hiironen pet cemetery was established, it is essential to examine first the aerial photograph taken in 1939 (). It shows the future site in the middle of a vast forest area, with a wide belt of cultivated fields in the north delimiting it from the town area. The most visible sign of human intervention in the immediate vicinity is a sand extraction pit some 400 m northeast of the site of the future pet cemetery.

This sand extraction pit proved highly significant regarding the general development of the area after it had been connected with the southern fringes of the habitation by a proper road (a,b). Sand could now be extracted with machinery, and when the pit was exhausted, it served as a municipal dump between 1954 and 1964. By the time the dump fell into disuse, the construction work for a 15-km stretch of a highway known as Pohjantie passing through the city of Oulu had begun. The highway, which officially opened for traffic in October 1967, flanks the pet cemetery to the west. Moreover, the area immediately southeast of the future pet cemetery site had been reserved for the construction of provincial central treatment facility of intellectually disabled persons since 1965.

The decision to accommodate OSEY’s initiative for the establishment of a pet cemetery during the late 1960s reflects broader societal developments. After WWII, a considerable proportion of the Finnish population had moved from the countryside to rapidly growing urban centers in search of a better life. As new suburbs were built to accommodate the masses, the keeping of pets was one way to overcome alienation and rootlessness in this new environment. Around the same time, industrial pollution, poor wastewater management, and the careless use of various toxic chemicals started to cause severe environmental issues. This increased general awareness of the fragility of nature and its occupants – humans and other mammals in particular – and the evident increase in the number of pet cemeteries established in Finland during the late 1960s and early 1970s mirrors this change.

Watered-down plans

While the cemetery was officially inaugurated in 1971, the first burials had already occurred at the site in 1969. OSEY estimated that new burials would accumulate at a pace of 100–150 interments per year. Two anecdotes best demonstrate the fact that pet cemeteries were then uncommon in Finland. Among the first animals to be buried to Hiironen was a pet cat from the town of Tampere, some 400 km south of Oulu. There, the local pet cemetery did not accept animals other than dogs, but at Hiironen even turtles – the most exotic pet of the time – were welcomed. The people running the pet cemetery also had quite optimistic ideas about turning the site into a tourist attraction. To enhance its appeal, the city of Oulu was successfully approached with a request to set up a signpost by the local road to guide potential visitors to the site.

However, the site had proven impractical for a pet cemetery by the 1980s due to its lack of good drainage (see also Pattison Citation1955, 253–254). The rule set by the town’s sanitary department, derived from the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Finland’s decree on the disposal of by-products from production animals, stated that dead animals should be buried to a depth of at least a meter. This would keep scavengers like foxes and rats away from the site. As the water table was encountered only 0.4 m beneath the ground surface in places, this would have required the burial of a dead pet in a watery pit in many plots, causing significant discontent among pet owners.

The extent to which the construction of the Pohjantie highway had contributed to these miserable conditions by barring the natural drainage is unclear. A report filed by the town engineering department in November 1986 proposed a circumvention to the depth requirement, with a grave pit dug just above the water table and a sufficiently high mound of soil topping it to cover the burial – the installation of underground drainage was deemed both too expensive and unsuitable for a cemetery context. However, as the pet cemetery was also running out of space, OSEY filed a request for a new cemetery space in a more suitable location in 1988.

Over the years when OSEY maintained the Hiironen pet cemetery, its surroundings were also subject to significant development. The building of the Kaukovainio suburb north of the site in the early 1970s brought everyday human activity close to it (c), while the Hiironen suburb, housing approximately two thousand inhabitants, was constructed just north of the former municipal dump three decades later. The two suburbs were then separated by the first stretch of Poikkimaantie – the Oulu ring road – and when a ramp was constructed to connect it to the Pohjantie highway (d), the earthworks disturbed the pet cemetery’s northwestern corner. External pressure resulting from the expansion of the urban area therefore also favored the operation’s relocation.

Neglected but not abandoned

When the new pet cemetery of Oulu was finally opened in a much better location at Mikonkangas in 1993, and OSEY ceased the active maintenance of the Hiironen site, people continued to visit the site, either to pay their respects to their late loved ones or just for the sake of curiosity. Our observations at the site on major public holidays related to commemoration, on All Saints’ Day and Christmas in particular, have revealed that a handful of pet owners continues to visit the graves (see also Jennbert Citation2003, 146 fig. 4; Pregowski Citation2016, 49; Citation2018, 116; Schuurman and Redmalm Citation2019, 36), even if the companion animal in question died in the 1980s.

Less than two dozen clandestine burials have been made at the site since its closure, but they were already a problem when the cemetery was in active use. A ten-year lease for a small pet burial plot at the Mikonkangas pet cemetery costs 70 euros today. The lack of money is therefore the most likely reason for such endeavors, but other explanations like people’s awareness of Hiironen as Oulu’s original pet cemetery should also be considered. In general, old pet cemeteries appear to be rather active stages for clandestine burials (see also Davenport and Harrison Citation2011, 182–183), and not always for monetary reasons. The need to bury a companion animal in a pet cemetery, albeit clandestinely, can also be about showing dignity to the late animal, while even more abstract interpretations, such as renegotiating and challenging the conception of the human as a superior being (Lyons Citation2013, 625; Ikäheimo Citation2020), have also been proposed.

City officials and OSEY had agreed to a relatively short 10-year status quo period (cf. Jennbert Citation2003, 146; Gross and Salkin Citation2020, 9), during which the site was exempt from urban development for a quarter-century. It was only in 2017, when the Pohjantie highway underwent a major overhaul, that a broad foundation ditch was dug through the cemetery’s western flank () for a sound barrier wall. As the public was informed about the expected disturbances in advance, nearly a dozen pet owners were motivated by this potential externalized threat (cf. Lorimer Citation2019, 332, 340) and showed up at the site to dig up their loved ones: One couple reportedly unearthed four cats and a dog. Soon thereafter a forest machine cleared a strip of land on the site’s western flank, smashing many grave markers in pieces as it went. This was reported by the local press and national tabloids as evidence of the gruesome destruction that had taken place at the site.

Figure 6. The earthworks related to the installation of a sound barrier wall by the Pohjantie highway damaged the western flank of the Hiironen pet cemetery in 2017. Photo: Janne Ikäheimo.

Today, nature continues to slowly but steadily take over the site by concealing grave markers made of stone and decaying those made of perishable materials. While the number of burials can be estimated to have been around 2500 in 1993, only 670 grave markers were observed in a survey conducted at the site in October 2020. Similarly, the sturdy log fence that once demarcated the pet cemetery’s perimeter is in a sorry state. However, in the effective town plan of Oulu, the parcel of land on which the pet cemetery is located enjoys the status of a green space, which should shield it from further urban development, at least for the time being.

Discussion

When the development of the Hiironen pet cemetery is reviewed as a mirror of societal values towards companion animals, both case-specific and general observations emerge. First, the parcel of land assigned by the city of Oulu in the late 1960s for the establishment of a communal pet cemetery at Hiironen was de facto nothing but a strip of wasteland. Due to its proximity to the then-new Pohjantie highway with its elevated traffic noise levels, the city would have hardly found any other use for it. The site was easily accessible yet sufficiently far away from the grid-plan area to cause any potential health hazard or land value-related economic loss. As a result, the city of Oulu leased the plot to OSEY without asking for any monetary compensation.

Yet the overall picture regarding societal values and attitudes towards companion animals in the 1960s is not particularly elevating. Dead pets, intellectually disabled people from all corners of the Northern Ostrobothnian province, and municipal waste were grouped – hardly by accident – in a remote and spatially concealed area that had long coincided with the southernmost fringe of the city’s administrative area. The Hiironen pet cemetery is therefore a typical example of the fringe-belt land use previously observed in the US with human cemeteries that were with time incorporated into the urban fabric, having been originally located on the outskirts of cities (Capels and Senville Citation2006, 2; Harvey Citation2006, 295; Chung Ho Citation2018). Such a location also seems typical of pet cemeteries in general (see also Pregowski Citation2016; Bardina Citation2017).

These context-related observations strengthen the idea of the status of pets as liminal beings residing between humans and wild animals; they are prominent actors in family life, but only marginal members of society (Ambros Citation2010, 332). Pet cemeteries are therefore of secondary if not tertiary importance in urban development and plot allocation. Yet by allocating a parcel of land for a pet cemetery, the significance of a pet’s death is acknowledged and made visible by society, and following this reasoning, it is quite difficult to grasp the act of burial as a meditated or subconscious act of animal marginalization (see also Howell Citation2015; cf. Mangum Citation2007). Allocating deceased companion animals to the same space as intellectually disabled people or municipal waste may at first sound outrageous, but parallels from other western societies can be observed. The most well-known example of the former is the association of a pet cemetery with Bohnice psychiatric hospital and its cemetery near Prague, Czech Republic, while in Britain, pet cemeteries are even today licensed as landfill sites (Mangum Citation2007, 24).

When it became necessary to relocate the pet cemetery from Hiironen, the new location assigned by the city at Mikonkangas represented an overall improvement to burial conditions. The new pet cemetery, which has accumulated approximately 10,000 pet burials in nearly three decades, occupies the southern section of a well-drained sandy plain. The area is used by Oulu urbanites for berrypicking and mushroom hunting, and the pet cemetery is surrounded by a network of paths used for hiking, jogging, and cross-country skiing. As the fringe of urban habitation is currently located several kilometers from the site, the tranquil atmosphere is bound to be preserved for a while. The contrast between the landscapes of these two sites mirrors the change in societal values towards companion animals by showing what kind of area was once deemed suitable for deceased pets.

How the pet cemetery was discussed in newspapers and other media also gives important hints about the change in societal values. When the Hiironen pet cemetery was founded, it was treated as a huge curiosity. One undated and unsourced newspaper clipping in the OSEY scrapbook states rather bluntly (our translation):

We are accustomed to bagging a cat with rocks, and in this way, decay at the bottom of a suitable pond is guaranteed. The forest surrounding the city also offers plenty of places for small pits to bury one’s departed discretely. However, the owner can’t know when the day will come when the place will be overturned to make space for a building, and the mortal remains of the pet are spirited away.

When that day came for the western part of the Hiironen pet cemetery in 2017, a public outcry both in ordinary and social media ensued. The opinions expressed ranged from conservative views underlining the fundamental difference between human and animal life and death, to more progressive ones asserting pets’ status as family members, requiring the sanctity of their graves to be equally respected. From the latter point of view, the situation is somewhat comparable to the case of Abney Park cemetery in London, which as the habitat of a rare saproxylic invertebrate species has influenced local land-use patterns and protected the site from further development (Gandy Citation2019). At Hiironen, similar “aesthetics of decay” result from the slow decomposition of vertebrate animals that were once considered dear and important.

Yet the Hiironen pet cemetery now seems shielded from further disturbances caused by the forces of urban renewal and expansion, thanks to the current town plan. It might even be suggested that the preceding and successive urban development created favorable conditions for its preservation. The location, an approximately 100–meter-wide strip of land between a former communal dump and the heavily trafficked highway, is not and will not be a developer’s dream in a city that doubled its land area in 2013 to more than 3000 km2 by merging with several adjacent municipalities. At the same time, the evident overall change in human-animal relations has transformed this reused parcel of wasteland into a place where only a few people continue actively to mourn and remember today, but whose existence and preservation enjoys the sympathy of many.

The place itself, which in this case has been largely taken over by nature, may also possess values related to its conception both as a physical and mental environment. Although not necessarily a space suitable for recreation, a seemingly neglected pet cemetery may attract visitors interested in pondering existential questions regarding mortality, the afterlife, and interspecies differences, for example. The short lifespan of many companion animals compared with humans may evoke thoughts on life and death at a general level. Schuurman and Redmalm (Citation2019, 32) note pointedly: “Living with companion animals brings a heightened sense of the fragility of life”. Thus, while pet cemeteries are above all places for grieving for late animal family members, mourning across species boundaries may allow us to see humanity in a different light and challenge how it is understood (Schuurman and Redmalm Citation2019, 32‒33). Old and overgrown pet cemeteries may evoke further thoughts about decay and nature taking over, offering people an opportunity to ruminate on the passing of time, mortality, and the shortness of human life (Burström Citation2009; Gaillemin Citation2009, 504).

Based on these observations, we advocate for more pet cemetery studies with increased awareness of their internal and external dynamics. At present, data on them seems seldom to be based on long-term observations, because sites are usually documented with visits spanning a relatively short period (but see Gustavsson Citation2011). We acknowledge that the long-term monitoring of a pet cemetery may present a challenge, but a sufficient baseline can be established with relatively modest input. In our case, this has been accomplished with annual visits to both Hiironen and Mikonkangas on two important holidays – All Saints’ Day and Christmas Eve – related to the remembrance of the deceased in Finland (see also Gaillemin Citation2009, 500). A rough index for the level of activity taking place at the site on such days can quickly be established by mapping the graves with lit candles. The insertion of new clandestine burials at Hiironen is another feature that bears witness to the continued use of this pet cemetery.

The previous observations and suggestions do not mean at all that the study of pet grave markers and their associated material culture would not continue to yield significant results – the reality is exactly the opposite. However, the present case study has hopefully succeeded in showing that other sources of information should also be exploited when studying and interpreting pet cemeteries. The increased awareness of the ever-changing temporal context in which the expressions of personal grief and longing for deceased companion animals are publicly displayed at these sites can lead to a fuller understanding of the expressions themselves.

Conclusion

In this article, the changing human-companion animal relations have been examined by focusing on public reactions and necrogeography of a pet cemetery located in Oulu, northern Finland from its foundation in 1971 to the present day. While the foundation of the site was tied to the arising environmental awareness, back then a wasteland at the outskirts of the town was seen as a suitable place for the cemetery. But as the site turned out to be unsuitable for burials in the early 1980s and the operations were relocated elsewhere, it continued to be important for the pet owners. The counterreaction to the partial destruction of the cemetery in 2017 highlighted the change in attitudes both on individual and societal level, signifying that the site is more than a neglected pet cemetery – a green area, an urban forest and a place of remembrance.

Thus, the article has underlined the importance of geographical context in the study of pet cemeteries. Rather than being static and haphazard collections of grave markers, these sites are characterized by internal and external dynamics that mirror both individual and societal human-animal relations. While grave markers with their contiguous zones are the primary evidence for the former, the pet cemetery as a land-use zone and its relationship with other elements in the urban landscape bear witness to the latter. Only when studied in tandem and complemented by sufficient data on possible temporal changes, can a full understanding of a given pet cemetery, or of an ordinary human cemetery, in its geographical context be achieved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Janne Ikäheimo

Janne Ikäheimo works as a lecturer in archaeology at the University of Oulu. While his dissertation focused on ceramic cooking pots produced in Roman Africa, his current research interests include pet burial customs in contemporary society, the Bronze Age in Northern Finland, and the introduction of metallurgy to eastern Fennoscandia and Northwest Russia. As a self-taught beer aficionado, he is also interested in the material culture, marketing, and sociology of craft beer.

Sara Jasmin Puska

Sara Jasmin Puska is studying archaeology at the University of Oulu and is currently preparing her MA thesis on the Hiironen pet cemetery.

Tiina Äikäs

Tiina Äikäs is a senior researcher in archaeology at the University of Oulu, Finland and holds a title of Docent in Archaeology at the University of Helsinki. She has also graduated on master’s level in Geography. Her doctoral thesis (2011) dealt with the ritual landscapes of Saami sacred places but in addition to the archaeology of religion, her research interests include place-bound memories, heritage studies, and industrial heritage.

References

- Äikäs, T., J. Ikäheimo, and R.-M. Leinonen. 2021. “How to Mound a Horse? Remembrance and Thoughts of Afterlife at Finnish Companion Animal Cemetery.” Society & Animals (Advance Article). doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-bja10044.

- Ambros, B. 2010. “The Necrogeography of Pet Memorial Spaces: Pets as Liminal Family Members in Contemporary Japan.” Material Religion 6 (3): 304–335.

- Auster, C. J., L. J. Auster-Gussman, and E. C. Carlson. 2020. “Lancaster Pet Cemetery Memorial Plaques 1951–2018: An Analysis of Inscriptions.” Anthrozoös 33 (2): 261–283.

- Bardina, S. 2017. “Social Functions of a Pet Graveyard: Analysis of Gravestone Records at the Metropolitan Pet Cemetery in Moscow.” Anthrozoös 30 (3): 415–427.

- Basmajian, C., and C. Coutts. 2010. “Planning for the Disposal of the Dead.” Journal of the American Planning Association 76 (3): 305–317.

- Brandes, S. 2009. “The Meaning of American Pet Cemetery Gravestones.” Ethnology 48: 99–118.

- Burström, M. 2009. “Garbage or Heritage: The Existential Dimension of a Car Cemetery.” In Contemporary Archaeologies: Excavating Now, edited by C. Holtorf, and A. Piccini, 131–143. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Capels, V., and W. Senville. 2006. “Planning for Cemeteries.” Planning Commissioners Journal 64: 1–8.

- Chalfen, R. 2003. “Celebrating Life after Death: The Appearance of Snapshots in Japanese Pet Gravesites.” Visual Studies 18: 144–156.

- Chung Ho, K. 2018. “Spatial Structure and Historical Change of Cemeteries in Seattle, USA.” Journal of the Korean Institute of Landscape Architecture 187: 36–45.

- Davenport, A., and K. Harrison. 2011. “Swinging the Blue Lamp: The Forensic Archaeology of Contemporary Child and Animal Burial in the UK.” Mortality 16 (2): 176–190.

- Davies, P. J., and G. Bennett. 2016. “Planning, Provision and Perpetuity of Deathscapes—Past and Future Trends and the Impact for City Planners.” Land Use Policy 55: 98–107.

- Evensen, K. H., H. Nordh, and M. Skaar. 2017. “Everyday Use of Urban Cemeteries: A Norwegian Case Study.” Landscape and Urban Planning 159: 76–84.

- Gaillemin, B. 2009. “Vivre et construire la mort des animaux.” Ethnologie Française 39: 495–507.

- Gandy, M. 2019. “The Fly that Tried to Save the World: Saproxylic Geographies and Other-Than-Human Ecologies.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 44 (2): 392–406.

- Gross, S., and P. Salkin. 2020. “Death Need Not Part Owners and their Pets: Regulating Pet Cemeteries through Zoning Regulation.” Zoning and Planning Law Report 43 (6): 1–15.

- Gustavsson, A. 2011. Cultural Studies on Death and Dying. Oslo: Novus Press.

- Harvey, T. 2006. “Sacred Spaces, Common Places: The Cemetery in the Contemporary American City.” Geographical Review 96 (2): 295–312.

- Hauru, K., S. Lehvävirta, K. Korpela, and D. J. Kotze. 2012. “Closure of View to the Urban Matrix has Positive Effects on Perceived Restorativeness in Urban Forests in Helsinki, Finland.” Landscape and Urban Planning 107: 361–369.

- Howell, P. 2015. At Home and Astray: The Domestic Dog in Victorian Britain. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Ikäheimo, J. 2020. “The Rescue Excavation and Reburial of Late Pet Animals as Explorative Archaeological Autoethnography.” In Entangled Beliefs and Rituals: Religion in Finland and Sápmi from Stone Age to Contemporary Times, edited by T. Äikäs, and S. Lipkin, 236–252. Monographs of the Archaeological Society of Finland 8. Helsinki: The Archaeological Society of Finland.

- Jennbert, K. 2003. “Animal Graves: Dog, Horse and Bear.” Current Swedish Archaeology 11: 139–152.

- Kean, H. 2013. “Human and Animal Space in Historic ‘Pet’ Cemeteries in London, New York and Paris.” In Animal Death, edited by J. Johnston, and F. Probyn-Rapsey, 21–42. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

- Kenney, E. 2004. “Pet Funerals and Animal Graves in Japan.” Mortality 9 (1): 42–60.

- Kniffen, F. 1967. “Necrogeography in the United States.” Geographical Review 57 (3): 426–427.

- Lai, K. Y., C. Sarkar, Z. Sun, and I. Scott. 2020. “Are Greenspace Attributes Associated with Perceived Restorativeness? A Comparative Study of Urban Cemeteries and Parks in Edinburgh, Scotland.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 53: 126720.

- Lorimer, H. 2019. “Dear Departed: Writing the Lifeworlds of Place.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 44 (2): 331–345.

- Lowenthal, D. 1979. “Age and Artifact: Dilemmas of Appreciation.” In The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays, edited by D. W. Meinig, 103–128. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lyons, K. J. 2013. “Cycles, Ceremonies, and Creeping Phlox.” Journal of Leisure Research 45 (5): 624–643.

- Mangum, T. 2007. “Animal Angst. Victorians Memorialize their Pets.” In Victorian Animal Dreams: Representations of Animals in Victorian Literature and Culture, edited by D. Denenholz Morse, and M. A. Danahay, 15–34. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Nash, A. 2018. “‘That This Too, Too Solid Flesh Would Melt … ’: Necrogeography, Gravestones, Cemeteries, and Deathscapes.” Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 42 (5): 548–565.

- Pattison, W. D. 1955. “The Cemeteries of Chicago: A Phase of Land Utilization.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 45 (3): 245–253.

- Pregowski, M. P. 2016. “All the World and a Little Bit More. Pet Cemetery Practices and Contemporary Relations between Humans and their Companion Animals.” In Mourning Animals: Rituals and Practices Surrounding Animal Death, edited by M. de Mello, 47–54. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- Pregowski, M. P. 2018. “Companion Animals in Japan, Poland and the United States of America.” Analecta Nipponica: Journal of Polish Association for Japanese Studies 8: 109–122.

- Puzdrakiewicz, K. 2020. “Cemeteries as (Un)wanted Heritage of Previous Communities. An Example of Changes in the Management of Cemeteries and their Social Perception in Gdańsk, Poland.” Landscape Online 86: 1–26.

- Quinton, J. M., and P. N. Duinker. 2019. “Beyond Burial: Researching and Managing Cemeteries as Urban Green Spaces, with Examples from Canada.” Environmental Reviews 27: 252–262.

- Quinton, J. M., P. N. Duinker, J. W. N. Steenberga, and J. D. Charles. 2020. “The Living among the Dead: Cemeteries as Urban Forests, Now and in the Future.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 48: 126564.

- Quinton, J. M., J. Östberg, and P. N. Duinker. 2020a. “The Importance of Multi-Scale Temporal and Spatial Management for Cemetery Trees in Malmö, Sweden.” Forests 11 (1): 78.

- Quinton, J. M., J. Östberg, and P. N. Duinker. 2020b. “The Influence of Cemetery Governance on Tree Management in Urban Cemeteries: A Case Study of Halifax, Canada and Malmö, Sweden.” Landscape and Urban Planning 194: 103699.

- Rugg, J. 2000. “Defining the Place of Burial: What Makes a Cemetery a Cemetery?” Mortality 5 (3): 259–275.

- Schuurman, N., and D. Redmalm. 2019. “Transgressing Boundaries of Grievability: Ambiguous Emotions at Pet Cemeteries.” Emotion, Space and Society 31: 32–40.

- Skår, M., H. Nordh, and G. Swensen. 2018. “Green Urban Cemeteries: More than Just Parks.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 11 (3): 362–382.

- Spiegelman, V., and R. Kastenbaum. 1990. “Pet Rest Memorial: Is Eternity Running Out of Time?” OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying 21 (1): 1–13.

- Swensen, G., H. Nordh, and J. Brendalsmo. 2016. “A Green Space Between Life and Death – A Case Study of Activities in Gamlebyen Cemetery in Oslo, Norway.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography 70 (1): 41–53.

- Taylor, L., and D. F. Hochuli. 2017. “Defining Greenspace: Multiple Uses across Multiple Disciplines.” Landscape and Urban Planning 158: 25–38.

- Tourigny, E. 2020. “Do All Dogs Go to Heaven? Tracking Human-Animal Relationships through the Archaeological Survey of Pet Cemeteries.” Antiquity 94 (378): 1614–1629.

- Williams, H. 2011. “Ashes to Asses: An Archaeological Perspective on Death and Donkeys.” Journal of Material Culture 16 (3): 219–239.

- Woodthorpe, K. 2011. “Sustaining the Contemporary Cemetery: Implementing Policy alongside Conflicting Perspectives and Purpose.” Mortality 16 (3): 259–276.

- Zeigler, D. J. 2015. “Visualizing the Dead: Contemporary Cemetery Landscapes.” In The Changing World Religion Map, edited by S. Brunn, 649–667. Dordrecht: Springer.