Abstract

Given the difficulties that newly trained teachers currently encounter in entering the profession, it has become increasingly necessary to reexamine the nature of pre-service clinically-based teacher preparation. This paper focuses on the role of clinical supervisors in the context of the College–Field Partnership (CFP), an innovative program that reframes clinical preparation as going beyond a focus on classroom teaching to experiencing the school as a whole. The paper is based on “Self-in-Field” action research (SiFAR) involving eight experienced clinical supervisors who were leaders of teams of clinical supervisors in the CFP program. Through joint reflection on their professional practice, they came to see the clinical supervisor’s role as constructing a “clinical preparation field” that extends beyond the traditional “triad” of pre-service teacher, mentor teacher, and clinical supervisor. Constructing an expanded clinical preparation field involves building relationships among a wide variety of actors within the school and the academic preparation program as well as fostering learning and development for students and school staff alike. Two important implications of this new role for clinical supervisors were the need to become more skilled at (1) dealing with the emotional elements of school practice and (2) facilitating organizational learning processes in the school.

Introduction

The last decade has seen a change, reflected in the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs; Ki-Moon, 2013), in the overarching goals of education. Emerging environments characterized by ambiguity, complexity, uncertainty, and volatility have shifted prevalent images of the ideal graduate and of what it takes to prepare graduates for a changing world (Bennett & Lemoine, Citation2014). As the goals of education and the role of teachers change, educational approaches and practices in the teacher education field must also change (Burns et al., Citation2020; Israeli Ministry of Education, Citation2021; Niklasson, Citation2015; O'Brien & Furlong, Citation2015). In teacher preparation, greater emphasis has been placed on Social-Emotional Learning (SEL; Jones & Bouffard, Citation2012; Schonert-Reichl et al., Citation2017; Lapidot-Lefler, Citation2022), supplementing the more traditional content-based teaching. In this context, clinically-based teacher preparation is seen as increasingly important for the preparation of teachers (Smith & Ingersoll, Citation2004). Despite changes and challenges in the field of teacher education, clinically-based teacher preparation, at least as it appears in the literature, still focuses almost exclusively on the teaching act itself and what goes on in the classroom (Burns et al., Citation2020; Niklasson, Citation2015; O'Brien & Furlong, Citation2015). Although the school context is occasionally mentioned, little attention is paid to the larger organizational contexts in which teaching takes place. Given the changes and challenges in education, there is increasing recognition that clinically-based teacher preparation must move beyond the classroom toward providing “a complete map of the roles of the future teacher” (Fuentes-Abeledo et al., Citation2020; Razer et al., Citation2019).

University-based clinical supervisors of pre-service teachers play a vital role in providing them with guidance, feedback, and support as they gain hands-on experience in the classroom (Burns et al., Citation2020). Widening the frame of clinically-based teacher preparation means reframing the role of the clinical supervisor as well. This paper argues that the role of the clinical supervisor needs to change from managing the pre-service teacher–mentor teacher–clinical supervisor relationship to constructing and maintaining a “clinical preparation field” that contains elements of the classroom, the wider school context, and the academic teacher-preparation program. The paper is based on action research in which a group of clinical supervisors systematically reflected on their practice in the context of an innovative clinically-based teacher preparation program in a college of teacher education where the study took place.

The paper begins with a review of the literature on the changing nature of clinical supervision and the role of the clinical supervisor. It then describes the setting for this study, an innovative clinical supervision program implemented by an Israeli college of education and the theoretical framework that guided it. It then describes the participatory “Self-in-Field Action Research” method used to study the changing role of clinical supervisors. The findings section presents two case studies from this action research process, focusing on the key differences between the traditional role of clinical supervisors and their role in the expanded clinical preparation field. The discussion section looks at the implications of this new role both for teacher preparation and for the knowledge and skills that clinical supervisors need to carry out that role effectively.

Literature review

The changing nature of clinical supervision

Clinically-based teacher preparation usually involves a “triad:” “pre-service teachers” studying in institutions of higher education, “mentor teachers” who open their classrooms as a place for pre-service teachers to gain hands-on experience, and “clinical supervisors” from the institution of higher education who oversee the clinical preparation process and guide the pre-service teacher (Bullough & Draper, Citation2004). There are many names for these three roles in the field of clinically-based teacher preparation. In this paper, we will use the terms “clinical supervisor,” “pre-service teacher,” and “mentor teacher.” However, to avoid confusion, we present to clarify exactly what we mean by these terms and other terms with the same meaning.

Table 1. Clarifying terminology and definitions.

Recent years have seen an increasing emphasis on clinical teacher preparation, not only on teaching techniques but also on reflective practice and dialogue involving all three parts of the triad (Burns et al., Citation2020; Min et al., Citation2017). Kolman (Citation2018) found that university-affiliated clinical supervisors play a crucial role in providing pre-service teachers with guidance, feedback, and support as they gain practical experience in the classroom setting. Furthermore, teacher preparation programs have been focusing more on the emotional aspects of teaching, including building interpersonal teacher–student relationships, rather than emphasizing only content delivery and classroom management skills (Burns et al., Citation2020). Stark and Cummings (Citation2023) emphasize the importance of providing pre-service teachers with the necessary skills to manage the emotional challenges inherent to the profession and the need for teacher education programs to prioritize the development of emotional competencies. Despite the recognition of the emotional and relational dimensions of teaching, some researchers have noted that these aspects are still overlooked in teacher preparation programs, which primarily focus on classroom performance and management skills rather than on emotional competencies. This gap in addressing the emotional side of teaching is evident both for practicing teachers as well as in pre-service preparation programs (Alvarez et al., Citation2022; Razer & Friedman, Citation2017; Razer et al., Citation2019; Woolfolk Hoy, Citation2013; Wright, Citation2009).

Studies of clinically-based teacher preparation (Acheson & Gall, Citation1980; Burns et al., Citation2020.; Smith & Ingersoll, Citation2004) have consistently pointed to the quality of clinical supervision as a key factor in the development of effective teachers. The authors found that pre-service teachers who received high-quality clinical supervision were more likely to be rated as effective by their mentor teachers and to be hired for teaching positions after graduation. Darling-Hammond and Bransford (Citation2005) found that clinical supervision is essential for helping pre-service teachers develop the knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed to be effective educators. The authors suggest that clinical supervisors should provide a balance of support and challenge to help pre-service teachers grow as professionals.

The college–field partnership (CFP) and pre-service teacher preparation

This study is based on an innovative program for pre-service teacher preparation at the secondary level developed by the Oranim College of Education in Israel. An examination of research on teacher dropout in Israel found that teacher education programs tended to be disconnected from school realities (Arviv-Elyashiv & Zimmerman, Citation2012; Shperling, Citation2015). This program, called the College–Field Partnership (CFP), was initiated in 2016 in response to this gap between traditional teacher-education programs and the authentic needs of graduates and Israeli schools. Thus, the program involves processes that better prepare pre-service teachers for their work, not just in the classroom, but in school as well and better ensure their integration in school life. Furthermore, it took into account the expectation that teaching would change significantly in the coming years and that it made little sense to train new teachers only in methods that could become, or already were, outdated. Thus, the idea was that the College–Field Partnership (CFP) would function not only as pre-service preparation, but also as a kind of mechanism for rethinking teaching and stimulating school change (Israeli Ministry of Education, Citation2021).

Most of the high schools in which Oranim students were placed served student populations that experience various forms of social exclusion (poverty, ethnic discrimination; Razer et al., Citation2019). Therefore, the CFP program placed emphasis on preparing students to be teachers who, as described by Razer et al. (Citation2019), build a facilitating environment that promotes cognitive, emotional, and social development that advances students’ integration, belonging, interest, and competence. Courses offered at the college were now more experiential and the entire framework of the program became “field oriented,” which meant an ongoing conscious effort to create a better fit between the two. Teachers were expected not only to teach the curriculum, but also to facilitate the social and emotional development of all their students and of themselves as people who must fill such a powerful role (Razer et al., Citation2019).

To address the gap between teacher education and practical experience, the CFP program focused on both the academic and practical aspects of teacher education. It provided an in-depth look at social stratification and at the relationship between pedagogy and issues of belonging, exclusion, and social inclusion. Pre-service teachers in the CFP program experience all aspects of the teacher’s role. The program increased the number of hours pre-service teachers spend at the school and extended the scope of their experiential and practical learning to encompass all aspects of the teacher’s role as well educational life inside and outside the classroom.

The clinical supervisor in the CFP carried out four major tasks: (1) worked with pre-service teachers to assist their professional growth, both individually and as a group; (2) provided ongoing support and promoted the professional development of mentor teachers, individually and as a group, (3) assisted the principal in preparing the school to function as an inclusive school and as a teacher-preparation school, and (4) strengthened the school’s ties with the college and coordinated the interface between the content taught in academic courses and the content taught at the school.

Field theory and the “clinical preparation field”

In this paper, we introduce the concept of the “clinical preparation field” as a way of understanding how the CFP changed clinically-based teacher preparation and, particularly, the role of the clinical supervisor. The clinical preparation field concept is based on “field theory” (Friedman, Citation2011; Bourdieu, Citation1985, Citation1998; Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2012; Lewin, Citation1951), which conceives of social realities as spaces constructed by people through sustained interactions. Social spaces constitute the “in-between” (Buber, Citation1965) and the “pattern that connects” (Bateson, Citation1979) that hold people together. Lewin (Citation1951) and Bourdieu (Citation1998) borrowed the concept of field from physics as a way of accounting for causality in a social space. Once formed, social fields tend to take on a life of their own and shape the thinking, feeling, and behavior of their constituents.

According to field theory, all social relationships—friendships, families, groups, organizations, societies, cultures, etc.—are social fields (Friedman et al., Citation2016). Lewin’s concept of group dynamics was based on the then-revolutionary idea that social fields, like gravitational or electromagnetic fields in the physical world, influence people without any observable, direct contact. Each field is characterized by a unique configuration of dimensions: (a) individual and institutional actors; (b) the nature of relationships; (c) the “rules of the game” that guide action, and (d) a set of shared meanings or cognitive frames which acts as a kind of “glue” that holds the field together and makes it coherent to its constituents (Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2012; Friedman et al., Citation2018).

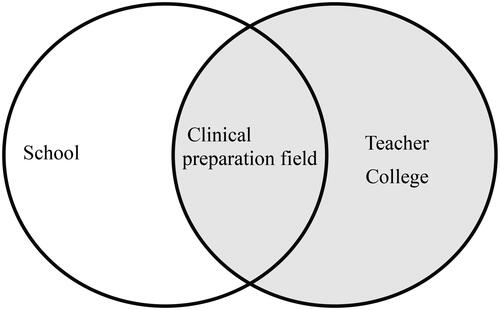

From the field theory perspective, the “clinical preparation field” is a distinct social space at the intersection of the pre-service students’ higher education institution and the school where the preparation takes place (see ). In most traditional clinically-based teacher preparation programs, the clinical preparation field is framed as a space in which the pre-service teacher learns from an experienced teacher how to teach and manage a class. The main actors are the triad: the pre-service teacher, the mentor teacher, and the clinical supervisor. The role of the mentor teacher is to mentor the pre-service teacher, and their relationship is strictly hierarchical. The role of the clinical supervisor is to set up the relationship (construct the field), periodically check in with the pre-service teacher, and solve problems that arise. In addition, the clinical supervisors mentor pre-service teachers, closely following their development and giving advice. The rules of the game are modeling by the mentor teacher, observation by the pre-service teacher, and opportunities for the pre-service teacher to teach classes, followed by feedback from the mentor teacher and the clinical supervisor.

The CFP created an expanded clinical preparation field that was much more complex and dynamic than the traditional clinical preparation field in most teacher preparation programs. Each pre-service teacher is mentored by an experienced mentor teacher, but there is an emphasis on providing the pre-service teacher with experiences and practice that go well beyond classroom teaching to include all of the teachers’ functions and tasks.

For clinical supervisors experienced in the traditional clinical preparation field, the transition to an expanded clinical preparation field was a major challenge. It required a continuous learning process involving a complete reinvention of their role through processes as they went along. Not all clinical supervisors were able to make the transformation successfully, but those who did felt that they had developed an entirely new form of practice. Four years after the CFP began, there were about 250 students and 24 clinical supervisors in the program, Nevertheless, it was very difficult to explain the new practice to clinical supervisors who joined the program. Therefore, the two first authors, who were leading clinical supervisors, initiated a process of action research for the purpose of reflecting on their practice knowledge so as to make it explicit, improve it and more easily communicable. They invited the third author to facilitate this reflection process using a Self-in-Field Action Research method.

Method

Self-in-field action research (SiFAR)

Field theory focuses neither on the individual nor on the collective as the unit of analysis but rather on the circular, reflexive processes through which individuals, in interaction with others, continually construct and reconstruct both their internal and external worlds (Friedman, Citation2011). People’s subjective (inner) realities and their objective (outer) realities shape each other, but most people are unaware of their own partial agency in shaping social reality (Friedman et al., Citation2014). Self-in-Field Action Research (Kurland et al., Citation2021) is a method for reflecting on this mutual shaping process so that it can be observed and changed, if necessary. In doing so, they asked themselves: How does the field shape my thinking, feeling, and behavior? Is that how I want to think, feel, and behave? How are my thinking, feeling, and behavior shaping the field? Is that the way I would like the field to be? SiFAR enables participants to make their practice explicit and improve it. It draws heavily on methods and tools from action science (Argyris et al., Citation1985), frame reflection (Schön & Rein, Citation1994), dialogue (Isaacs, Citation1999), and psychodynamic approaches to organizational change (Hirschhorn, Citation1990).

Participants and engagement procedures

The participants in this research included eight academic staff members who led the CFP program at the school of education in the college. Six of the participants were clinical supervisors at the time of the study, and two others had been clinical supervisors in the past. All were currently supervising other clinical supervisors in the context of their work in CFP. They all voluntarily chose to engage in Self-in-Field Action Research, after serious consideration of ethical issues and potential biases and after obtaining approval from the college ethics review board. The participants defined their action research questions as follows: (a) How do we, clinical supervisors, perceive our role in the CFP program? (b) What action strategies do we use to fulfill this perceived role? (c) What challenges and dilemmas do we face? What action strategies do we use to address them? How can these strategies be improved?

Data collection and analysis stage 1: Methods and procedure

Self-in-Field action research, like many dialogic forms of action research (Friedman et al., Citation2016), carries out data collection and analysis at the same time through a process in which participants reflect on their experience, inquire into it, and make sense of it. In this research, the group described above held 18 bi-weekly 90-minute action research sessions from October 2020 to June 2021 in order to inquire reflectively and collaboratively into their professional work. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, all meetings took place on Zoom. All group sessions and most individual meetings were recorded and transcribed. During the first three sessions, the participants inquired into and described their own work processes as clinical supervisors and identified core issues. In the fourth meeting, participants wrote personal cases, including reflective components, based on their work, to provide data illustrating the issues identified in the first stage. (The guidelines they received for writing cases can be found in Appendix). The group chose the five most representative studies to analyze in depth. The cases were presented by the case writer, one at a time, in the group. Each case analysis took about two sessions. During the first one, the facilitator and other participants helped the case writer inquire into the cases jointly in light of the research questions. The inquiry focused on exploring the clinical supervisors’ external and internal fields, identifying the clinical supervisor’s implicit “theory of action” (Argyris et al., Citation1985). When the clinical supervisors felt stuck, their internal and external fields were examined to understand the source of the difficulty and to suggest possible alternative actions. Because of the limited time available for group meetings, the facilitator often met with individual participants for the purpose of delving more deeply into their case studies.

During the sessions, all the participants conducted a joint inquiry, interpreted the data, and offered advice. These interpretations and suggestions often differed, and the group rarely reached a consensus in one session. Between sessions, however, the facilitator analyzed the transcript of the previous meeting in an attempt to integrate interpretations, insights, conceptualizations, and advice into a coherent analysis. At the next meeting, the facilitator presented his analysis to the group, enabling participants to validate or disconfirm it and offer corrections, revisions, additions, and alternative interpretations. The group then continued to discuss the case, focusing on how to improve practice as well as the conceptual discoveries. Thus, from session to session, the clinical supervisors generated an increasingly clear picture of the expanded clinical preparation field and their role in shaping it.

Research questions

The goal of this paper is to investigate changes in the role of clinical supervisors in the CFP and to consider its implications for re-envisioning clinical supervision in general. To achieve this goal, the paper addresses the following research questions:

How did clinical supervisors in the CFP program reframe their practice? How does this reframing differ from the conventional practice as exemplified in the preparation triad?

What are the key challenges faced by clinical supervisors fulfilling this reframed practice?

What action strategies and skills need to be developed to address these challenges effectively?

Data analysis stage 2: Methods and process

The expanded clinical preparation field concept emerged in the action research itself. The clinical supervisors felt that this concept enabled them to intuitively make much better sense of the key differences between the traditional clinical supervisor roles and practices and those that developed through the CFP program. In order to make these differences explicit, the authors, who had also been participants, retrospectively analyzed the transcripts and conceptualizations from the Self-in-Field action research process. They employed the four components of a field - actors, nature of relationships, rules of the game, and frames of meaning - as the categories through which to analyze the data (see ), constituting a form of deductive qualitative that uses existing theory to examine meanings, processes, and narratives of interpersonal and intrapersonal phenomena (Fife & Gossner, Citation2024).

Table 2. Analytic categories and their connection to field theory constructs (Friedman et al., Citation2018).

The data analysis using these four theory-based categories utilized a form of “thick description” defined by Ponterotto (Citation2015) as “interpreting observed social action (or behavior) within its particular context” (p. 543). The underlying assumption of this method is that the data contain specific incidents that can be seen as exemplars of the phenomenon being studied and contain most of the relevant meanings to understand the phenomenon. The analytical method is to present this incident, unpack it, and connect it to other data points so as to fully explicate the phenomenon. Ponterotto points to five characteristics of thick description: (a) interpretation in context, (b) capturing thoughts and emotions, (c) assigning motivations and intentions, (d) rich accounts of details, and (e) detailing the meaningfulness of situations. Therefore, after analyzing all five cases that were analyzed in the SiFAR process, we chose two cases as exemplars illustrating the key, distinguishing characteristics of the expanded preparation field.

Findings

Noga’s case

The first case was presented by Noga (all names are pseudonyms), who pointed to a specific situation that she was currently experiencing in her work as a clinical supervisor:

The incident I chose to present contains, in my opinion, a lot of the complexities and challenges that are typical of the clinical supervisor experience. The incident took place at the end of a routine history lesson in the eleventh grade, which was being taught by one of the mentor teachers and observed by the pre-service teacher. One of the students in the classroom followed the pre-service teacher as she exited the classroom and said: “It’s a lot more fun when pre-service teachers teach the class. When you taught, as well as the other pre-service teachers, things are a lot more interesting…” The pre-service teacher shared this experience with me saying that this feedback of course pleased her, but saddened her as well. I could sense her enormous frustration. As a first step after she brought this incident to my attention, I decided to extend our conversation to gain a better grasp of the complexities of the situation… It was important to me that the pre-service teacher express her feelings… without feeling guilty or as if she were siding with the students.

My next step will be to have a meeting with the mentor teacher and the pre-service teacher together to discuss this incident and to try to understand what could be learned from it and taken back positively to the classroom… After that, I will also have a meeting with the school principal and the team of mentor teachers, in which I hope to better define what can be gained from bringing the pre-service teachers into our classrooms.

Actors

Although this case focuses on classroom teaching and the traditional “triad” in which the actors are the pre-service teacher, mentor teacher, and the clinical supervisor, it illustrates fundamental differences in the expanded clinical preparation field. In Noga’s perception of the situation, the triad was only part of a larger group of actors who should be involved in the preparation process. The above quote shows that Noga was planning to follow up on the event by “meeting with the principal and the team of mentor teachers.”

In the expanded clinical preparation field, the principal plays a much more central and active role in the expanded clinical preparation field than in the traditional triad. Furthermore, the clinical supervisor does not relate to the mentor teachers individually, in separate triads, but builds a school-wide team from all of the teachers who have pre-service teachers in their classrooms. This team represents a kind of institutional actor that is comprised of, but also distinct from, the individual teachers. The clinical supervisor builds this team by facilitating a workshop at the very beginning of the school year and meets with the mentor teachers, as a group, periodically throughout the school. By the same token, the clinical supervisor builds a group from the different students doing their student teaching in the school so that they can learn from each other’s experience. Another key institutional actor is the “teacher liaison,” who is the clinical supervisor’s main contact person in the school.

The individual students, the individual teachers, the principal, the teacher liaison, the mentor teacher team, the student group, and the principal are all key individual and institutional actors in the expanded clinical preparation field that becomes a distinct entity within the school. The clinical supervisor constructs a complex clinical preparation field by bringing these actors together and generating interaction among them. The active involvement of the principal and the two teams provide frameworks for seeing the preparation process from the perspective of the school as a whole rather than from the narrow perspective of the individual classrooms. At the same time, these frameworks offer the school opportunities to use the experiences of the pre-service teachers and other actors in the preparation process as opportunities for reflection, inquiry, and learning at the organizational level. What goes on in the classroom no longer stays only in the classroom, providing important information.

Another set of actors not directly mentioned in this case are faculty members who teach formal courses at the academic institution where the students are studying. While they may not be physically present in the schools, they too are part of the clinical preparation field, meeting regularly with the clinical supervisor and the student teams. Thus, important information about the students’ experience as well as what is happening in the schools, in general, is fed back into the formal educational process. This feedback process provides the academic faculty with valuable information for continually adjusting curricula and teaching to the actual needs of the pre-service teachers.

Nature of relationships

As seen above, clinical supervisors in the expanded clinical preparation field create a much more complex and active network of relationships than exists in the traditional triad. However, it also points to the nature of relationships within the field. As in the traditional triad, it is critically important to create an open, trusting relationship between the pre-service teacher and the clinical supervisor. As Noga wrote, “it was important to me that the pre-service teacher express her feelings… without feeling guilty or as if she were siding with the students.” Noga wanted the student to feel free to reflect openly, not for the purpose of judging the teacher, but to understand what it might mean for the pre-service teacher as both a student and a future professional.

Noga, however, “decided to extend our conversation to gain a better grasp of the complexities of the situation.” In other words, she was not going to leave it just between her and the pre-service teacher. Rather, Noga planned to meet with the mentor teacher and the pre-service teacher together “to see what could be learned from and taken positively back to the classroom.” Noga’s willingness to talk with the mentor teacher about this issue points to a fundamental difference in the relationship between the clinical supervisor and the mentor teacher that characterizes the traditional triad. Clearly, she was dealing with a sensitive situation that could be extremely threatening to the mentor teacher. The clinical supervisor could hardly consider discussing this situation with the teacher unless they had already developed an open and trusting relationship. The following excerpt from the group discussion about Noga’s case illustrates the intimacy of this relationship:

Participant: Tell me, can you have a deep discussion with her about what really happened?

Noga: You don’t understand. I have intimate discussions with her at 9:00 PM… I talk with her completely openly, I tell her that it can’t be that way. That’s not what she wants to teach the student-teacher…

(and later in the inquiry process)

Noga: This connects me to the beautiful and constructive conversations and process I am doing with another teacher there who also started from a very, very unsatisfying place for me. He is also a new teacher… He is in a different place… For example, with him I also have difficult things statements…

Noga also wrote that, after meeting with the teacher, she would “have a meeting with the school principal and the team of mentor teachers, in which I hope to better define what can be gained from bringing the pre-service teachers into our classrooms.” Such a meeting would be feasible only if Noga had fostered relationships of mutual respect, trust, and openness to learning not just between herself and the mentor teacher, but with all the actors in the clinical preparation field. In summing up the process of analyzing her case, Noga stated the following:

I feel this conversation really helped me, it’s good, and it very was important for me. It helped me refine the conversation I'm planning with my principal, which I was planning for him anyway. I think that towards next year, it’s a great trigger to send him a few messages. A few work condition requirements are now much clearer to me. When I started the school year, I wanted to understand what was going on there, and today I know what to say. This conversation helped me go straight to the principal and set up an upcoming conversation, and from there to set out on a journey…

“Rules of the game” (normative action strategies)

The clinical supervisor sensed that the issue here was not simply a classroom student’s complaint that the pre-service teacher was more interesting than the mentor teacher. According to the pre-service teacher’s account, the student had said that lessons with all of the pre-service teachers were more interesting. Noga sensed something deeper here that went beyond the particular mentor teacher and pre-service teacher, although it was not quite clear to her what this incident meant. For her, in the expanded clinical preparation field, the appropriate action was to inquire among all of the actors and bring them together to see what they could learn from this incident. Thus, she intended to take the additional steps of (a) providing feedback to the teacher based on what she heard from the pre-service teacher and (b) initiating a discussion with the principal and the mentor teacher team.

Using issues that arise within the traditional triad as opportunities for learning for the mentor teacher and at the school level represents significant changes in the rules of the game. Another clinical supervisor illustrated this difference as follows:

When you identify (an issue), I think it’s important, at least at that point in time, to work on it – to mobilize the principal and the teachers and all of that with, or without, the students. That’s what we spoke about before on the parallel lines and the different arenas in which the clinical supervisor works. Sometimes the arenas connect, and that’s great, and sometimes they don’t.

Frames of meaning

The relationships between the actors and the rules of the game are all embedded within a reframing of what the pre-service clinical preparation field is meant to do. In the triadic clinical preparation field, the task is framed mostly one way—helping the student learn to be a teacher. The roles of both the clinical supervisor and the mentor teacher are focused on achieving this goal. In the expanded clinical preparation field, helping the student learn to be a teacher is still the central task, but it is also a springboard to a much larger framing, which is to help the school as a whole to become a preparation institution. This framing is reflected in the following quote from another clinical supervisor:

I imagine a courtyard in…the school, a real physical courtyard, between the teachers’ room, the principal’s office, the classrooms, and the dormitories, to place a boundary around it, a new field, and, as I see, it gives a lot of strength to the students, to the clinical supervisor, to the principal, and to the teacher mentors. We invite you to this new field. Come and see what’s here, what we can do here. That’s an amazing new partnership.

Alona’s case

The second case was presented by Alona, who had worked as a clinical supervisor in one school for three years and had been very successful. Her case takes place during her first year as a clinical supervisor in a new school and describes a key part of constructing the expanded clinical preparation field:

My case deals with one of the core tasks of our job as clinical supervisors: developing a relationship with the school principal… I succeeded in forming the group of students, establishing initial relations with the teacher educators, and by now I have a positive, meaningful, and efficient relationship with the teacher liaison…Unfortunately, the relationship with the school principal did not go well. We met for the first time at the end of the summer and then we had short exchanges about how things were going. I occasionally dropped by her office informally. After several weeks, I noticed that I had begun to avoid her. It became clear to me that I was not developing the relationship in the way I am used to and that I needed to find a different way to connect.

At that point, I took a break and began consulting with colleagues. One of them shared with me her experiences with that same principal: “The principal likes having people listen to her… It took me a while to get close and make the connection… Right now, let go of your own plans and agenda, and just focus on forging the relationship.”

When I think of a positive relationship, I think about connection. I want to be happy to run into her and to know that the feeling is mutual… to have a feeling of mutual trust. In my previous school, I managed to quickly forge a positive working relationship with the school principal and we shared a sense of mutual appreciation. We could talk about many things, big and small. I could discuss anything with her… Even negative things that were happening at the school. I have no doubt that this positive relationship contributed to the advancement of the school and promoted our goals for the preparation program.

After consulting additional colleagues and thinking some more, I decided it was time to restart my efforts to connect with the current school principal. But this time I consciously chose and implemented other types of tools for planning and forging the connection. I arranged prescheduled meetings with the principal and the liaison teacher and at these meetings, I focused more on listening than on talking and sharing. At the same time, I looked for other strengths I could utilize to enhance the relationship. I made sure not to allow the principal to hurry me, as she did at the beginning of the school year. Slowly, I began voicing my thoughts and conveying the voices of the pre-service teachers. Sure enough, the relationship began to take form. We maintain ongoing contact and also have positive informal meetings.

Actors

Alona, as clinical supervisor, worked at creating relationships with many different actors from the beginning of the year. This network of connections serves not only the clinical supervisor but the mentor teachers and pre-service teachers as well. It provides the pre-service teachers with a much larger circle of actors, including their peers, with whom they can consult and from whom they can learn. For the mentor teachers it also expands this circle, but in a much more profound way. Teaching tends to be one of the most autonomous, if not lonely, professions in the world (Westheimer, Citation1998). The fact that teachers in the school are more closely connected to each other through the clinical supervisor in the expanded clinical preparation field provides them with a professional and emotional support network rarely available to teachers in most schools (Razer & Friedman, Citation2017). Although this support involves being exposed to greater scrutiny by other actors, it enables mentor teachers to learn more not only about the preparation role, but also about themselves as mentor teachers.

Although Alona’s case mentions almost the entire array of actors in the expanded clinical preparation field—clinical supervisor, the school principal, group of students, teacher educators, and teacher liaison—it clearly emphasizes the key role of the principal as a critical actor in the field. As this case illustrates, it was not enough for the principal to give her blessing to the program and allow the clinical supervisor freedom to work with a wide variety of school personnel. The clinical supervisor required much more. The relationship with the principals is critical in the expanded clinical preparation field as it serves as a kind of model, setting the tone for the entire school. Furthermore, it is essential in using pre-service teacher preparation as a springboard for learning at the school level.

Nature of relationships

Alona’s case clearly illustrates the kind of relationship that a clinical supervisor seeks to form with the principal in constructing the expanded clinical preparation field. The word Alona used to describe the desired relationship was “connection,” indicating a strong, personal bond based on “mutual trust” and “mutual appreciation.” Connection is important for enabling clinical supervisors to convey “the voices of the pre-service teachers” to the principal and to allow them the freedom to “discuss anything…even negative things that were happening in the school.” It allows for both professional discourse as well as an empathic, emotional relationship that serves as a kind of modeling for relationships between other actors in the field (Razer et al., Citation2019).

Alona’s case illustrates the emotional work involved in building relationships with key actors in the expanded clinical preparation field. She was facing a situation in which the school principal, a key actor in the expanded preparation field, was not showing commitment to the program. The group inquired into the clinical supervisor’s external field, exploring the principal’s behavior toward her and the program, which she described as “not taking an interest” and “brushing her off.” The group then inquired into how this situation influenced the clinical supervisor’s internal field, which she described as feelings of rejection and disappointment. On deeper inquiry, it became clear that these feelings stemmed mainly from the contrast between the clinical supervisor’s relationship with this principal and her close relationship with the principal in her previous school. As the inquiry progressed, the clinical supervisor realized that her feelings were influenced by this comparison. This led her to take the principal’s behavior personally and interpret it negatively, causing her to distance herself and refrain from pushing certain parts of the CFP. As she became more aware of her internal field, the clinical supervisor reinterpreted the situation, acknowledging that this principal had a different personality and that she might have misinterpreted the principal’s behavior. In other words, the clinical supervisor’s internal field had prevented her from seeing this difference and realizing that she had to approach the principal in a way that was more appropriate to her management style.

“Rules of the game” (normative action strategies)

Alona had a fairly clear “agenda,” or set of action strategies, for developing the extended clinical preparation field in her new school. Connecting with the school principal was one of these strategies, but, based on previous experience, she expected this relationship to form naturally, mostly through informal interactions. However, as Alona’s case indicates, the exact “rules of the game” for building relationships may vary from school to school, depending on the personalities of the principal and the clinical supervisor. When she found herself avoiding the principal in this school, it became clear to Alona that the informal approach was not working. She then stopped and reflected with the help of colleagues. The combination of critical self-awareness and dialogue with colleagues enabled her to identify the rules of the game governing relations with the principal, to overcome what had become an obstacle, and to connect with the principal in a way that opened the door to a positive collaboration.

This case attests to the importance of identifying the rules of the game with this specific principal in this specific school. Alona realized that she had to give up familiar “tools” for a while in favor of others that came less naturally to her. As a result, she realized that she had to (1) schedule formal meetings and (2) listen more to the principal and connect up to what interested her rather than push her own agenda. At the same time, she set certain boundaries. At the beginning of the year, she had interpreted the principal’s tendency to encourage her to move ahead quickly as a sign of understanding and commitment. Now she realized that she had misread these signals, which actually indicated a lack of involvement, and that she should not be misled or pushed by the principal’s sense of urgency.

Frames of meaning

The concept of “connection” is central to Alona’s case and reflects a fundamental frame that characterizes the expanded clinical preparation field. As pointed out above, connection refers to a particular kind of relationship that clinical supervisors attempt to foster in the clinical preparation field. Another clinical supervisor used the metaphor of dancing the “tango” in describing her work with the school:

I feel that it takes two to tango. A good clinical supervisor can say what she thinks, but she needs to be sure that the teacher meets up with what she says. But I say this with reservations, maybe there is still something I don’t see there…

Within the expanded clinical preparation field, the meaning of teaching is reframed to include connection, which means also becoming competent in dealing with the emotional aspects of the work. Teachers who work in difficult emotional climates are generally not equipped to deal effectively with emotional outbursts, whether expressed through speech or disruptive behavior. As a result, they often respond in inappropriate ways that can make things worse for both the child and themselves. Therefore, spaces need to be created in schools for dealing with the emotional side of educational practice (Razer et al., Citation2019), allowing for the expression and legitimization of emotion so that teachers can step back and reflect. Safe spaces for reflection can enable teachers to develop more effective responses to difficult situations rather than responding out of emotional distress (Razer & Friedman, Citation2017). The same is true in pre-service teacher preparation, which focuses mainly on classroom performance and management, leaving the emotional side of teaching relatively undiscussed (Alvarez et al., Citation2022; Woolfolk Hoy, Citation2013).

The extended clinical preparation field is meant to be a field in which the emotional element, as symbolized by connection, can be engaged as a central part of teaching practice. However, as the first case (Noga’s) illustrates, engaging this emotional element may be as important for veteran teachers as it is for pre-service teachers. In any case, connection means that constructing the clinical preparation field is not simply a set of formal or bureaucratic relationships for carrying out the task of pre-service teacher preparation. Rather, it means creating a certain quality of interpersonal relations that is rare in most schools. These relations allow for the surfacing and acknowledgment of important issues, sometimes very difficult and threatening ones that may have been undiscussable in the past. Connection is important for the development of both classroom students and school staff.

Discussion

Pedagogical instruction has traditionally been regarded as the core component of clinically-based pre-service teacher preparation and the triad involving pre-service teacher, mentor teacher, and clinical supervisor and has been seen as the arena in which most of this learning process takes place (Bullough & Draper, Citation2004; Chaliès et al., Citation2012). However, given the difficulties that teachers currently encounter as they enter the education system, it has become increasingly necessary to reexamine this process, including the clinical supervisor’s role and the tasks this role entails (Arviv-Elyashiv & Zimmerman, Citation2012; Shperling, Citation2015).

The goal of this paper has been to present a reframing of clinical supervision practice for pre-service teachers based on action research carried out with clinical supervisors in the College–Field Partnership (CFP), an innovative pre-service teacher preparation program. This research was guided by the following research questions: (a) How did clinical supervisors in the CFP program reframe their practice and how did their new practice differ from conventional practice as exemplified in the preparation triad? (b) What are the key challenges faced by clinical supervisors in their reframed practice? (c) What action strategies and skills need to be developed to address these challenges effectively?

Field theory and self-in-field action research (SiFAR) have been applied in numerous settings (e.g., the author references), but to the best of our knowledge, it has not been carried out specifically in the realm of teacher education, and more precisely, in the context of clinical supervisors. Our study aims to bridge this gap by applying the principles of field theory to the unique challenges and opportunities presented in the teachers’ education and the development of educators. This perspective can yield valuable insights and contribute meaningfully to the existing body of knowledge in both field theory and teacher education.

The findings of the research, as summarized in , illustrate the extensive differences between the practice of the clinical supervisor in the traditional clinical preparation field and the practice in the expanded clinical preparation field. This expanded role reflects a shift in the field of education from a focus on teacher performance and its effect on individual student outcomes to a focus on the “learning environment” that focuses on how “educators can proactively change schools and educational practices to better support students in their social, emotional, and academic development” (Paunesku & Farrington, Citation2020, p. 122).

Table 3. The clinical preparation field and the role of clinical supervisor.

In the discussion, we will look at two key challenges presented by this changed role to clinical supervisors and some of the additional knowledge and skills they need to fill this role. The first challenge is the extensive emotional work involved in constructing and maintaining a clinical preparation field with the school. The second challenge is acting as an agent of organizational learning that involves not only pre-service teachers but mentor teachers and the school as a whole.

Emotional work

Expanding the clinical preparation field makes it possible to deepen the preparation process and significantly support the students’ learning experience and the development of the school staff. However, it requires considerable emotional work on the part of the clinical supervisor. This emotional work builds directly on the skills of reflective practice, which today are widely accepted as an important component of the competence of clinical supervisors (Burns et al., Citation2020). Self-in-Field Action Research (Friedman et al., Citation2020; Kurland et al., Citation2021) sees emotional work in terms of the mutual shaping between what can be called “the internal field” and the “external field.”

In Alona’s case, for example, the clinical supervisor encountered her own emotional discomfort during her attempts to connect with the principal even though she was aware that her relationship with the principal was a critical component of the clinical preparation field she was trying to develop. Through reflection, she became aware not only of her avoidance, but also how this avoidance was fostered by an implicit set of ideas about how the relationship should be based on her previous experience. Through inquiry with colleagues, she recognized that, to connect with the principal, she needed to make changes in her internal field—feelings, expectations, and assumptions about the principal—that would enable her to adopt new action strategies for connecting with the principal. Eventually she succeeded in building this relationship. It took Alona more time and it led her to shape a clinical preparation field that was different, though no less supportive of learning, than in her previous school. In the same process, she changed herself.

The creation and maintenance of the clinical preparation field requires developing customized relationships with each of the actors and then balancing them all together. As can be seen from the analysis of Noga’s case, one seemingly small incident can produce a multitude of tasks and the need to work on relationships with many actors. With each of these actors, she had to act a little differently. With the pre-service teacher, she needed to cultivate the ability to be both empathic and assertive toward the mentor teacher. With the mentor teacher, she might have developed a discourse around letting go of control and diversifying the teaching methods discussion. With the rest of the mentor teachers, she needed to raise a question demanding a high degree of sensitivity and skill. The preparation program is thus grounded in the understanding that educators’ familiarity with their own inner fields and their ongoing interaction with external fields is the key to professional practice of the clinical supervisor. Making the internal field discussable is a meaning frame that shapes the entire preparation program, and the clinical supervisor as part of the program’s staff operates accordingly with whom he or she must establish and maintain positive and meaningful relationships over time. Of course, the frequency of the clinical supervisor’s meetings with the different actors and the intensity of the connection between them may differ by school.

Clinical supervisors never shape the clinical preparation field alone. By definition, fields emerge through interaction among people, all of whom have an important influence on the nature of the field (Friedman et al., Citation2016). From a Self-in-Field Action Research perspective, the construction and maintenance of the clinical preparation field is an ongoing experimental process of reflection-in-action (Schön, Citation1983), carried out together with, and shaped by, other actors in the field. However, it is mainly the clinical supervisor’s role to facilitate the process of constructing the expanded clinical preparation field by linking together diverse actors into a pattern of relationships, rules of the game, and frames that are distinct from those that characterize the school or the academic setting. This role involves a continuous cyclical process and the ability of clinical supervisors to gain insight into their inner and outer fields and, at the same time, strengthening and improving interactions and relationships with the various partners.

Agents of organizational learning and change

The idea that the role of clinical supervisor should change is based on the assumption that, given the rapid changes faced by schools and the increasing complexity of student populations, the traditional model or conception of teacher clinically-based teacher preparation must change (Razer et al., Citation2019). It can no longer focus mainly on the classroom but must engage the school and educational processes in general. This expanded clinical preparation field means not only that the role of clinical supervisors must change, but that clinical supervisors themselves can, or perhaps must, be agents of organizational learning and change within schools.

Once an expanded clinical preparation field takes shape and stabilizes, it may become a kind of “enclave” (Friedman et al., Citation2014) within the school characterized by actors, relationships, norms, and frames that may differ significantly from those characteristics of the dominant school culture. dominant school culture. The expanded clinical preparation field is expanded over time as well as space. While students may rotate every few years, the clinical supervisor, principal, and mentor teachers provide continuity. Despite occasional turnover of key actors, necessitating ongoing reconstruction, the expanded clinical preparation field can become an integral part of the school. It enriches the student experience and serves as a vehicle for organizational learning (Lipshitz et al., Citation2006). By convening various actors to explore school practices, the clinical supervisor facilitates individual and organizational learning, potentially catalyzing change and uncovering new strategies.

There is no question that the expanded clinical preparation field demands much more from clinical supervisors than their traditional roles. From the perspective of the clinical supervisor, carrying this expanded role can sometimes seem like finding one’s way in a labyrinth. In the first years of the CFP program, many clinical supervisors found this complexity overwhelming. Part of the problem was that the thinking, feeling, and acting of the clinical supervisors were shaped by the traditional, narrow definition of the pre-service teacher–mentor teacher–clinical supervisor triad. The clinical supervisors experienced an enormous expansion of their role in the CFP, but did not know how to make sense of it. Reframing their role as constructing a clinical preparation field helped them make sense of the new role and see more clearly what they needed to do to successfully fulfill it.

Given the complexity and uncertainty involved, the role of clinical supervisor in the expanded clinical preparation field almost inevitably involves some “getting lost” (Brydon-Miller et al., Citation2021). However, getting lost may sometimes be a necessary step when entering new and uncharted territory. Self-in-Field Action Research itself provides clinical supervisors with tools to deal with this challenge. Stopping to explore where they find themselves, reorienting themselves, and discovering and/or creating previously unknown routes, are essential parts of clinical supervisors’ work process in the expanded preparation field. Furthermore, a positive outlook on the future and the ability to engage uncertainly are essential for exploring and uncovering complexities in inner and outer fields (Lindstrom-Johnson et al., Citation2016; Wong et al., Citation2019).

The current study has several limitations. It does not claim to show that the CFP program or the reframed clinical supervisor’s role led to, or failed to lead to, better adjustment of pre-service teachers in their transition from teacher preparation programs to the role as full-time teachers in schools. Nor does it illustrate change or improvement in the pre-service teacher experience. Such claims require a more systematic, in-depth evaluation of the CFP program itself. Furthermore, this research represents a specific group of clinical supervisors from a specific, innovative program with a focus on schools working with children at risk and/or experiencing exclusion. Care must be taken when generalizing the findings to other groups, and follow-up studies should examine the idea of expanding the role of clinical supervisors in a variety of cultural or social contexts. Additional research is necessary also on how to expand the clinical preparation field in different contexts and on measuring the effect of expanded clinical preparation fields on a wide variety of outcome measures. Another limitation relates to the fact that participants’ perceptions and coping strategies were examined during the COVID-19 crisis. It can be assumed that if the study had been conducted at a different point in time, or over a longer period, different experiences might have emerged.

Despite these limitations, this study might provide inspiration for both designers of in-service programs and clinical supervisors who wish to expand their role and to experiment with preparation spaces they construct. Thinking of the clinical supervisor’s role as constructing and maintaining a clinical preparation field yields opportunities for learning and development among actors in both the school and academic institutions who were traditionally outside of the preservice teacher–mentor teacher–clinical supervisor triad. Furthermore, the idea of clinical supervisor as agent of organizational learning in schools provides a potential strategy for dealing with the uncertain future of education. It is widely accepted that schools need to change to meet the changing needs of young people along with the challenges presented by the rapid changes in almost every parameter of life (Hoşgörür, Citation2016; Stark & Cummings, Citation2023; Thomson et al., Citation2011; Wrigley et al., Citation2011). At the same time, no one really knows what these changes will look like (Hargreaves & Goodson, Citation2006; Thomson et al., Citation2011). This reality presents a perplexing problem of how to train new teachers for a profession that is likely to be transformed during their own careers. To the extent that the role of clinical supervisors includes constructing and maintaining an expanded clinical preparation field, in-service preparation might provide a mechanism not only to prepare new teachers to meet these challenges but to help schools to meet them as well.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Acheson, K. A., & Gall, M. D. (1980). Techniques in the clinical supervision of teachers. In Preservice and inservice Applications. Longman.

- Argyris, C., Putnam, R., & McLain Smith, D. (1985). Action science: Concepts, methods, and skills for research and intervention. Jossey-Bass.

- Alvarez, I. M., González-Parera, M., & Manero, B. (2022). The role of emotions in classroom conflict management. Case studies geared towards improving teacher training. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 818431. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.818431

- Arviv-Elyashiv, R., & Zimmerman, V. (2012). Dropping out of the teaching profession in Israel: Motives, risk factors, and coping, from the teachers’ and the school system’s perspective. Shvilei Mechkar (Research Paths), 18, 52–62. Hebrew).

- Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and nature: A necessary unity. Dutton.

- Bennett, N., & Lemoine, J. (2014). What VUCA really means for you. Harvard Business Review, 92(1/2), 27. https://hbr.org/2014/01/what-vuca-really-means-for-you

- Bourdieu, P. (1985). The social space and the genesis of groups. Theory and Society, 14(6), 723–744. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00174048

- Bourdieu, P. (1998). Practical reason: On the theory of action. Stanford University Press.

- Brydon-Miller, M., Aragon, A. O., & Friedman, V. J. (2021). The fine art of getting lost: Ethics as a guide to transformative learning in action research. In D. Burns, J. Howard, & S. M. Ospina (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of participatory research and inquiry. SAGE.

- Buber, M. (1965). The knowledge of man: Selected essays. Humanity Books.

- Bullough, R. V., Jr,., & Draper, R. J. (2004). Making sense of a failed triad: Mentors, university supervisors, and positioning theory. Journal of Teacher Education, 55(5), 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487104269804

- Burns, R. W., Jacobs, J., & Yendol-Hoppey, D. (2020). A framework for naming the scope and nature of teacher candidate supervision in clinically-based teacher preparation: Tasks, high-leverage practices, and pedagogical routines of practice. The Teacher Educator, 55(2), 214–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2019.1682091

- Chaliès, S., Escalié, G., Stefano, B., & Clarke, A. (2012). Learning “rules” of practice within the context of the practicum triad: A case study of learning to teach. Canadian Journal of Education, 35(2), 3–23. https://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/855

- Chew, S. L., & Cerbin, W. J. (2021). The cognitive challenges of effective teaching. The Journal of Economic Education, 52(1), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2020.1845266

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (2005). Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do. Jossey-Bass.

- Fife, S. T., & Gossner, J. D. (2024). Deductive Qualitative Analysis: Evaluating, Expanding, and Refining Theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069241244856

- Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2012). A theory of fields. Oxford University Press.

- Friedman, V. J. (2011). Revisiting social space: Relational thinking about organizational change. In Research in organizational change and development. Emerald Group Publishing.

- Friedman, V. J., Simonovich, J., Bitar, N., Sykes, I., Abboud-Armali, O., Arieli, D., Tannous-Haddad, L., Rothman, J., Shdema, I., Dar, M., & Desivilya Syna, H. (2020). Self-in-field action research in natural spaces of encounter: Inclusion, learning, and organizational change. International Review of Qualitative Research, 13(2), 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940844720934369

- Friedman, V. J., Sykes, I., Lapidot-Lefler, N., & Haj, N. (2016). Social space as a generative image for dialogic organization development. In Research in organizational change and development (Vol. 24, pp. 113–144). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Friedman, V. J., Sykes, I., & Strauch, M. (2014). Expanding the realm of the possible: Enclaves and the transformation of fields. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2014(1), 11989. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2014.11989abstract

- Friedman, V. J., Sykes, I., & Strauch, M. (2018). Expanding the realm of the possible: Field theory and a relational framing of social entrepreneurship. In Social entrepreneurship (pp. 239–263). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Fuentes-Abeledo, E. J., González-Sanmamed, M., Muñoz-Carril, P. C., & Veiga-Rio, E. J. (2020). Teacher training and learning to teach: An analysis of tasks in the practicum. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(3), 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1748595

- Hargreaves, A., & Goodson, I. (2006). Educational change over time? The sustainability and nonsustainability of three decades of secondary school change and continuity. Educational Administration Quarterly, 42(1), 3–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X05277975

- Hirschhorn, L. (1990). The workplace within: Psychodynamics of organizational life. MIT Press.

- Hoşgörür, V. (2016). Views of primary school administrators on change in schools and change management practices. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16(6), 2029–2055. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2016.6.0099

- Isaacs, W. (1999). Dialogue: The art of thinking together. Currency.

- Israeli Ministry of Education (2021). Academy – classroom”: A strategic document. Challenges, goals, and objectives. The Unit for Research and Development in Practice Teaching, The Israeli Ministry of Education and MOFET Institute (Hebrew).

- Jones, S. M., & Bouffard, S. M. (2012). Social and emotional learning in schools: From programs to strategies. Social Policy Report, 26(4), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2379-3988.2012.tb00073.x

- Kolman, J. S. (2018). Clinical supervision in teacher preparation: Exploring the practices of university-affiliated supervisors. Action in Teacher Education, 40(3), 272–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2018.1486748

- Ki-Moon, B. (2013). The millennium development goals report 2013. United Nations.

- Kurland, H., Friedman, V., Sykes, I., Lichtenstein, R. D., & Melamed, T. (2021). A self-in-field action research inquiry process. In D. Burns, J. Howard, & S. M. Ospina (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of participatory research and inquiry (pp. 596–610). SAGE.

- Lapidot-Lefler, N. (2022). Promoting the use of social-emotional learning in online teacher education. International Journal of Emotional Education, 14(2), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.56300/HSZP5315

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers. Harper & Row. (Republished 1997, American Psychological Association).

- Lipshitz, R., Friedman, V. J., & Popper, M. (2006). Demystifying organizational learning. Sage Publications.

- Lindstrom-Johnson, S. R., Pas, E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2016). Understanding the association between school climate and future orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(8), 1575–1586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0321-1

- Niklasson, L. (2015). Reorganizing of practicum in initial teacher education: A search for challenges in implementation by ex-ante evaluation. Journal of Arts & Humanities, 4(9), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.18533/journal.v4i9.806

- Min, W. Y., Mansor, R., & Samsudin, S. (2017). Facilitating reflective practice in teacher education: An analysis of student teachers’ level of reflection during teacher clinical experience. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7(3), 599–612. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i3/2762

- O'Brien, M., & Furlong, C. (2015). Continuities and discontinuities in the life histories of teacher educators in changing times. Irish Educational Studies, 34(4), 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2015.1128349

- Paunesku, D., & Farrington, C. A. (2020). Measure learning environments, not just students, to support learning and development. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 122(14), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146812012201404

- Ponterotto, J. G. (2015). Brief note on the origins, evolution, and meaning of the qualitative research concept thick description. The Qualitative Report, 11(3), 538–549. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2006.1666

- Razer, M., & Friedman, V. (2017). From exclusion to excellence: Building restorative relationships to create inclusive schools. UNESCO–International Bureau of Education and Sense Publishers.

- Razer, M., Israeli, E., Zorda, A., & Hefetz, G. (2019). CFP the College-Field Partnership: Preparing teachers to educate. The MOFET Institute Newsletter: Discussion Platform, 63(Hebrew).

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. Basic Books.

- Schön, D. A., & Rein, M. (1994). Frame reflection: Toward the resolution of intractable policy controversies. Basic Books.

- Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Kitil, M. J., & Hanson-Peterson, J. (2017). To reach the students, teach the teachers: A national scan of teacher preparation and social & emotional learning. A Report Prepared for CASEL. Collaborative for academic, social, and emotional learning.

- Shperling, D. (2015). Teacher dropout around the world: Information survey. MOFET Institute (Hebrew).

- Smith, T., & Ingersoll, R. (2004). What are the effects of induction and mentoring on beginning teacher turnover? American Educational Research Journal, 41(3), 681–714. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312041003681

- Stark, K., & Cummings, C. (2023). Emotions as Both a Tool and a Liability: A Phenomenology of Urban Charter School Teachers’ Emotions. The Urban Review, 55(3), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-022-00649-y

- Thomson, P., Lingard, B., & Wrigley, T. (2011). Reimagining school change: The necessity and reasons for hope. In T. Wrigley, P. Thomson, & B. Lingard (Eds.), Changing schools: Alternative ways to make a world of difference (pp. 1–14). Routledge.

- Westheimer, J. (1998). Among school teachers: Community, autonomy and ideology in teachers’ work. Teachers College Press.

- Wrigley, T., Thomson, P., & Lingard, R. (Eds.). (2011). Changing schools: Alternative ways to make a world of difference. Routledge.

- Wong, T. K., Parent, A. M., & Konishi, C. (2019). Feeling connected: The roles of student-teacher relationships and sense of school belonging on future orientation. International Journal of Educational Research, 94, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.01.008

- Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2013). A reflection on the place of emotion in teaching and teacher education. In M. Newberry, A. Gallant, & P. Riley (Eds.), Emotion and school: Understanding how the hidden curriculum influences relationships, leadership, teaching, and learning (pp. 255–270). Emerald Publishing.

- Wright, A. (2009). Every child matters: Discourses of challenging behavior. Pastoral Care in Education, 27(4), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643940903349344

Appendix

Instructions for reporting a personal incident

These are the instructions that the study participants were given on how to report a personal incident.

Reporting a personal incident

What is “personal incident reporting?”

Personal incident reporting is a tool for reflecting and learning from experience. It serves as the basis for learning and gaining knowledge in action research. Using this tool, participants can present the way they cope with issues, with reciprocal relationships, in collaborative tasks involving problem-solving or conflict resolution. The personal incident is considered a “sample” of the participant’s behavior. The event or incident can be related to the workplace or one’s personal life; it can be an actual and current incident, a past incident, or even an imagined situation that the participant uses to describe future coping methods. Furthermore, the incident described can relate to either a case of effective or ineffective coping. The most important aspect is to select a challenging, unresolved, and significant incident so that the observation exercise will be beneficial to your learning process.

Steps in reporting the incident

Describe the background to the incident: What was the situation or problem? How did it develop? Who were the people involved? What was your role? Add any information that is important to understanding the event. (Approximately 1–2 pages.)

Describe what you meant to do to cope with the situation or to solve the problem. What were your goals? How did you intend to obtain them? Why did you select these goals? (Approximately 1 page.)

Next, recall what she said and did as well as what you thought and felt while you were acting. Report this scenario or dialogue to the best of your ability. (Approximately 2 pages.) Use the following format:

Describe the outcomes of the incident and your assessment of your performance and its effectiveness.