ABSTRACT

During 2020, sales of books increased as readers found more time to engage with fiction and return to books that provided comfort and a sense of escapism. The Covid-19 pandemic also provided the space for a new genre, “covid fiction”, to emerge. This article examines the sub-genre of “covid poetry” by integrating text and reader response data analysis to examine the representation of the pandemic experience in Michele Witthaus’ poem “The new shape of fear”. Analysis of the data reveals that participants interpret and discuss the poem by drawing on foregrounded language features in the text, reflecting on their own pandemic experiences and demonstrating empathy with the experiences of others. These findings demonstrate that covid poetry may have particular interpretative effects that are geared towards self- and other-understanding. Overall, the article sets out some first steps towards examining the stylistic characteristics and interpretative effects of this emerging and important genre.

1. Introduction

In 2020, many countries across the world saw periods of lockdown or stay at home quarantines come into effect as the result of the Covid-19 pandemic. The enforced changes to personal and professional circumstances affected reading habits through new demands on time, the closure of libraries, and social reading environments such as face to face readings groups moving online. In the early stages of the pandemic, 31% of people in the UK reported reading more (The Reading Agency, Citation2020) with many stating that reading acted as a form of escapism from the anxieties brought on by covid and lockdowns (Boucher et al., Citation2020). More generally, the use of literature as a coping strategy and the therapeutic benefits of reading are well-documented. Reading may promote personal wellbeing (Bate & Schuman, Citation2016; Brewster, Citation2016) and function as a way of coping with life stresses (Gellatly et al., Citation2007; Gray et al., Citation2015). Reading for pleasure is an immersive experience (Nell, Citation1988), a kind of simulation (Oatley, Citation1994) in which difficult scenarios are played out in the safety of imaginative spaces. It may also help us to understand the mental functioning of others (Kidd & Castano, Citation2017; Oatley, Citation2016) bringing tangible pro-social and empathy-inducing effects (Johnson, Citation2012; Vezzali et al., Citation2015). Shaw (Citation2021, p. 179) makes the explicit connection between the trauma of lockdown experience and the therapeutic nature of reading poetry when she argues that.

Since March 2020, we have all survived trauma on a universal scale: the sudden shattering of our shared realities and sense of safety […] we discovered we needed poetry more than ever before – its ability to console and connect, to express sorrow, to find beauty, to create meaning.

Since the advent of covid, there has been an emergence of writing directly influenced by and/or representing the experience of living through the pandemic, what I term, for the purposes of this article, covid fiction. Early covid fiction initially appeared as short stories and poetry, forms that could be written quickly and shared easily by writers, although, at the time of writing, a growing body of longer literary fiction has equally emerged. The growth of this genre may well align with literary responses that arose from other major historical catastrophes, for example, the First World War (Trott, Citation2017), the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918 (Outka, Citation2019), and the 9/11 attacks (Keniston & Follansbee Quinn, Citation2010). The fact that since 2020 writers have already begun to represent the lockdown and post-lockdown phases of the pandemic means that we are very likely to witness the growth of a new genre that will be of interest to literary scholars. Of equal interest, and the focus of this article, is how readers use covid fiction as way of making sense of pandemic experiences, particularly given what we know about how reading may promote understanding of the self and of others.

This article contributes to our understanding of the stylistic and interpretative effects of this new genre through a case study approach which analyses the poem “The new shape of fear” by Michele Witthaus. Using a literary linguistic methodology that combines textual analysis with reader response data drawn from a questionnaire and reading group discussion, the article provides, to my knowledge, the first empirical study of the ways in which readers respond to and discuss their reading of covid fiction, offering an invaluable insight into the particular interpretative effects of the genre. Specifically, then, this article addresses the following research questions:

What are the stylistic characteristics of the poem “The new shape of fear” and how might these be indicative of the wider genre of covid fiction (here specifically poetry)?

How do readers interpret “The new shape of fear” in light of their own experiences of the pandemic? And how do they make sense of the pandemic through their reading the poem?

To what extent do readers report that “The new shape of fear” helps them to understand the pandemic experiences of others?

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In section 2, I discuss the sub-gene of “covid poetry” in more detail before providing an overview of “The new shape of fear” and the collection within which it was published. Section 4 outlines my research design and methodology, and section 5 reports on my analysis of the text and reader response data. Finally, in section 6, I discuss the implications of my findings and offer some additional thoughts on future directions for the study of this new genre.

2. Covid poetry

Poetry is an interesting sub-genre of covid fiction because, unlike the novel, it is a form that is relatively easy to share, and offers an immediate outlet for personal response, particularly through the affordances of social media. In the UK, the first months of lockdown saw a range of poetic output, from single poems that went “viral” to anthologies produced by local communities or in support of charities or bodies such as the National Health Service. King’s College, London ran a #poemsfromlockdown initiative that saw contributors read a favourite poem and then share via Twitter, and the Poetry Generation website posted videos of poetry being read by an elderly person isolated due to the lockdown. As Bravo (Citation2020) outlines.

From daily readings on the Today programme to minimalist lines on Instagram, poetry has become one of the emerging cultural trends of the pandemic. It’s being retweeted at pace, shared by distant friends on Facebook and slipped into our pockets via WhatsApp groups […] Where before we might have been squeamish, seeing poetry as the preserve of the pretentious or sentimental, a little of that cynicism seems to have been put on hold.

For established writers, the pandemic provided an opportunity for involvement in large-scale projects. For example, the WRITE where we are now project hosted at Manchester Metropolitan University, UK created an archive of poems that was made available to the general public, and Poetry and Covid-19 (Caleshu & Waterman, Citation2021) brought together UK and international poets’ responses to the pandemic in a unique collaborative and dialogic format. Beyond single poems, many poets began to publish whole collections influenced by their pandemic experience. In some cases, writing was viewed as an inevitable fulfilling of poetic duty. For example, the Irish poet William Wall provided the following rationale for his pandemic collection Smugglers in the Underground Hug Trade: A Journal of the Plague Year (Wall, Citation2021):

I began this book in February 2020 at the urging of my wife, Liz. She argued that I should somehow attempt to chronicle the experience of living through a pandemic and that such a chronicle might be of interest to future generations. No doubt, many other writers are doing the same. My hope is that this ‘journal’ in the form of poetry will add to what must surely become a mass of observations, notes, diaries, fictions and other literary and artistic representations of this terrible time. (Wall, Citation2021, p. 153)

Wall’s collection is an example of what I am terming covid poetry, defined as a sub-genre of covid fiction and specifically poetry that is directly influenced by and/or represents the experience of living through the pandemic. My own definition then excludes pre-covid poems that may have been read during the pandemic but did not arise as a result of it and differs from, for example, Acim’s broader notion of “lockdown poetry” which he defines as “poetry that was read or written during self-isolation and quarantine” (Citation2021, p. 68) and Sharma’s poetry read “in the context of COVID-19” (Citation2021, p. 105). My definition is closer to Dera’s whose “corona poetry” is that “written within the framework of the pandemic” (Citation2021, p. 79) and “poetry that has been written specifically in reaction to the corona crisis” (p. 90).

Generally, the advent of the pandemic saw the increased purchasing of poetry collections and a renewed sense of readers’ perception of poetry as a type of “comfort” reading (Wood, Citation2020). Patniak, drawing on Erikson’s (Citation1995) notion of the “social dimension” of collective trauma (a shared sense of loss that is formed by but distinctive from idiosyncratic trauma) argues that pandemic poetry reading generated other-oriented empathy; for Patniak, reading poetry “[…] harness[es] the potential to experience the self in the Other through collective testimony” (Patnaik, Citation2022, p. 80). In a study of readers in the Netherlands and Belgium, Dera (Citation2021) found that those who enjoyed covid poetry did so because they recognised the events portrayed in them as familiar to their own and were able to align their experiences to them in a way that had therapeutic value.

The data analysed in this article form part of a larger project building and analysing a corpus of covid poetry collections that have been published by UK and Irish poets following the first lockdown months. In a similar manner to Wall’s collection which explicitly mentions the “plague year”, other collections also directly signpost the pandemic either through their titles or front covers. For example, Empty Trains (Sandifer-Smith, Citation2022) highlights the reduced use of public transport due to home-working, while The Oscillations (Fox, Citation2021) consists of post and pre-covid halves to represent the changes brought about by the pandemic, and Shield (Hale, Citation2021) is a series of sonnets exploring the pandemic from the perspective of those with comprised health conditions. Other collections signpost the pandemic even more explicitly: both One Hundred Lockdown Sonnets (Saphra, Citation2021) and 111 Haiku for Lockdown (Jones, Citation2020) focus on a range of different experiences using one particular poetic form. Some collections, however, draw attention to the pandemic visually: the front cover of Do You Know How Kind I Am? (Bell, Citation2021) has the words “Keep 2 m apart”, a reminder of the ubiquitous practice of pandemic social distancing, in large white lettering against a grey pavement background.

3. From a sheltered place

From A Sheltered Place (Witthaus, Citation2020) is a collection of poems whose paratextual elements also index the pandemic and lockdown periods, both in the title and accompanying front image (see ), which depict a perspective looking out of a window from an enclosed space (which I infer to be a house or other residential dwelling), and the biographical note and synopsis that appear on the inside and back cover:

Michele Witthaus is based in the United Kingdom and her writing has appeared in a variety of anthologies and publications. Between March and June 2020, she wrote almost 100 poems in response to her experience of lockdown and the changes wrought by the global Covid-19 pandemic. This series of poems is part of that journey (from ‘About the Author’)

In these poems, Michele Witthaus explores how our natural concerns and suspicions are magnified by the intensity of lockdown (from the back cover)

Figure 1. Front cover of From A Sheltered Place. (I am grateful to Michele Witthaus for allowing me to reprint both the cover of her collection and the poem “The new shape of fear” in this article.)

As Gibbons (Citation2011, p. 19) notes, paratextual features play an important role in positioning readers to interpret a text in a particular as they explicitly trigger knowledge frames and “aid in setting expectations as to the genre of a book”. The paratext of From A Sheltered Place thus triggers a covid schema, “a cognitive structure which provides information about our understanding of generic entities, events and situations, and in so doing helps to scaffold our mental understanding of the world” (Emmott et al., Citation2017, p. 268). Generally, then, a reader comes to this collection knowing it is about the pandemic and this frames their reading.

“The new shape of fear” is the third poem in the collection. It was chosen for this study due to its accessible length and due to the fact that it was thought to address aspects of the pandemic which might have been experienced by most people. The poem is reprinted below; an analysis of its language appears in section 5.

4. Methodology and methods

My approach in this article follows that of scholarship in modern stylistics by integrating text analysis with reader response data so as to develop an understanding both of the text itself and of the ways in which the text is interpreted by readers (see Bell et al., Citation2019; Whiteley & Canning, Citation2017 for discussion). The text analysis of “The new shape of fear” draws on foregrounding theory (Mukařovský, Citation1964; Short, Citation1996) which asserts that certain textual features will be more prominent and therefore will potentially be viewed as salient by readers. Foregrounding may arise at one or more levels of analysis through parallelism (repeated patterns within a single text) and/or deviation (a break from an existing pattern) which may be internal (measured against patterns in the text) or external (measured against external norms of use). Practically, foregrounding provides an overarching methodological framework for the analyst who “must select some features and ignore others” (Leech & Short, Citation2007, p. 55) when analysing a text. The theory also provides a model for hypothesising that foregrounded features align to position a reader to interpret a text in some way, what Leech (Citation1970) refers to as the “cohesion of foregrounding”.

The reader response data were generated using several methods. A reading group format was chosen as it typically mimics a more natural reading context and reflects the kinds of social spaces in which people discuss books. It is also similar to a focus group, a method for generating data that facilitates extended discussion, and is used in stylistic research where the aim is to replicate the act of reading. The participants recruited were schoolteachers or librarians working in UK schools and were made aware that they would be participating on a study of covid poetry; recruitment thus ensured participant similarity (Denscombe, Citation2021), and the fact that they were considered expert readers avoided the issue that they might merely paraphrase some of the texts and maximised the possibility of engagement (Hanauer, Citation2001).Footnote1 Overall, six participants took part in the study, within the optimal range for focus group research (Fowler, Citation2009). The reading group was run online using the Zoom platform and utilised a “Virtual Procedure Document” (based on Roberts et al., Citation2021) to ensure that there were no technical issues and that participants were able to speak to a researcher should the need arise. Participants were given the following instructions with 30 min of group discussion taking place between questions 2 and 3.Footnote2

This poem is from a collection of poetry about the pandemic. We would like you to read, think about and discuss the poem in the light of your own experience of the pandemic as well as how the poem makes you think about the experiences of others depicted in the text. Following the group discussion, we will then ask you to complete the final task on page 3.

Underline any words and/or phrases that you feel are important and add any comments about your initial thoughts on the poem.

Answer the following two further questions by highlighting a point on each scale.

I can relate the events and experiences in the poem to my own experiences during the pandemic

| b) | Reading this poem helps me to understand how someone else experienced the pandemic | ||||

| 3. | Following the group discussion, please add any final thoughts on the poem. If annotating the poem, please use a different colour to your response to task 1. | ||||

The study thus combined both naturalistic and experimental elements (Swann & Allington, Citation2009) in that the poem was presented unaltered, and participants discussed it with minimal researcher control and interference (Steen, Citation1992). The use, however, of pre- and post-reading questions generated data that could be quantitatively analysed.

The Zoom session was recorded and transcribed by a research assistant with the resulting transcript double-checked for accuracy. Responses to questions 1 and 3 as well as reading group data were then coded using NVivo. A hybrid process of coding that made use of a priori codes aligning with the research questions (language features, self and other orientation) was initially adopted; the data were then inductively coded which revealed further specific themes (Questions 1 and 3) and different sub-categories of self and other-oriented talk (Question 3). In the following section, I first provide a short stylistic analysis of “The new shape of fear” before examining data generated from Question 1 and the reading group discussion. Due to space constraints, it is not possible to examine other parts of the data in this article.

5. Results and analysis

5.1. Stylistic analysis of “the new shape of fear”

The poem’s title consists of a single noun phrase, foregrounding several aspects of the pandemic. The use of the article “the” draws attention to its definiteness and the adjectival modification of “new” highlights both a temporal (i.e. of this time) dimension and the expectation of some kind of change. The phrase’s head noun “shape” is construed in a schematic (Langacker, Citation2008) fashion, which conceals any descriptive quality, and for me implies a sense of uncertainty and mystery; an interpretation also supported by the post-qualifying prepositional phrase “of fear”.

A striking example of foregrounding in the form of parallelism occurs in the poem’s use of the pronoun system and the binary pair I/me and you. The poem is spoken in the first person and thus draws attention to a specific speaking consciousness, which is objectified (Langacker, Citation2008) in that it forms an integral part of the scene being described. The “you” of the poem, however, appears to be a specific yet unknown entity yet could have a more general referent as the poem progresses. Indeed, I read “you” as having strong potential to function in a doubly-deictic manner (Herman Citation1994) with its referent both an addressee within the world of the text and the reader themselves being spoken to at a different ontological level. As the poem progresses, the subjectivity of the first line is replaced, however, by more conventional scene development as the reader builds up specific mental representations derived from both the language of the text and schematic knowledge. The poem has a strong emphasis on the physical through the parallel possessive determiner + noun structures in lines 2 and 3, “your breath, your sweat, your dander;/your scent in the air”, where the head nouns all relate to some kind of bodily attribute, and in the verb choices “brush”, “catching”, “lurch”, “looming”. Equally, the internal deviation in “white-hot hoarding frenzy” acts, I think, as a preface to the more granular description that occurs towards and up to the end of the poem, “face unguarded”, “your eyes”, “fever or fear”.

The poem also uses orientational language as the speaking voice is positioned spatially in relation to the moving “you”. This is realised linguistically in the form of the prepositional phrases “past me”, “ahead of me” and “through the supermarket door” by which the “you” moves away from the speaker, and then a reverse orientation in the final three lines of the poem where “you” moves back along a path in the direction of the speaker, “towards me”. There may also be a reversal in perspective at the end of the poem, another example of internal deviation, as the consciousness and emotions of “you” are presented. Given that the ending of a poem has attentional prominence, and therefore salience, the shift away from speaker to the other “you” positions the reader to adopt this latter viewpoint. Finally, the poem’s language invites readers to draw on several schemas related to the pandemic. The most obvious one, delayed in terms of being explicitly mentioned in the text, is of a supermarket, which in the UK became one of the very few spaces where people were allowed to visit and integrate, albeit with social distancing. This delayed mention results in a readerly adjustment of an earlier mental representation of the scene to now include a more specific sense of place, and is also graphologically and phonologically marked for salience through the repeated /s/ sound in “supermarket’s sliding”.

Overall, there are several foregrounded features and connections to pandemic experience in the poem: the attention to the self and other through the use of first and second person pronouns; the emphasis on the embodied experience of the pandemic through physical vocabulary choices; the orientational language and repositioning of viewpoint towards the end of the poem; and the use of the supermarket as a delayed spatial anchor, which would in theory trigger a specific supermarket schema. The interpretative significance of these language features can be further examined by analysing the reader response data; this is the focus of sections 5.2 and 5.3.

5.2. Initial responses to “the new shape of fear”

Question 1 consisted of two parts. First, participants were asked to underline any words and/or phrases that they felt were important.

1 = “looming” (6 mentions)

1 = “too close” (6)

3 = “dander” (5)

3 = “irrational” (5)

5 = “brush” (4)

5 = “ablaze” (4).

These results align in an interesting way with my stylistic analysis of the poem that highlighted certain foregrounded language features. For example, the poem’s foregrounding of proximity through orientational language was recognised by the readers in their highlighting of “looming” (a form which unlike some of the other verbs captures both the sense of movement towards the speaker and the sense of proximity) and the more summative phrase “too close”. The poem’s use of “dander” is a striking use of both internal and external deviation; a search of the British National CorpusFootnote3 reveals it to be rarely used and not appearing at all in its sense of “flaking human skin”; it is therefore unsurprising that this was highlighted by participants. Equally, the adjectives “irrational” and “ablaze” are foregrounded through their positions at the beginning and end of the poem respectively, which may account for their inclusion.

The second part of Question 1 generated more qualitative data. In the initial a priori coding, those instances where participants had made a reference to some aspect of language and/or commented on the interpretative effects of the feature (e.g. use of a narrative or poetic technique or a particular word) were coded as language features. A second level of inductive coding further differentiated instances where comments offered broader interpretations in more general terms; these were coded using one of the emerging theme codes: fear; illness; space; animalistic; and physical.

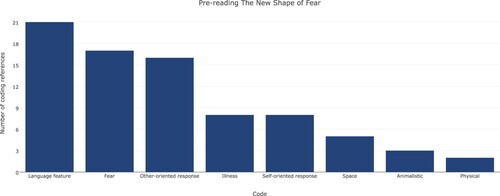

illustrates the number of coding references applied to the pre-reading comments on the poem. The results show that participants tended to concentrate their comments on specific language features or on other-oriented responses, or else made references to the theme of fear.

In their comments, participants reported that they were drawn to the poem’s use of the first-person, a prominent stylistic feature of the poem, equating this technique with a specific interpretative/framing effect; participant 3, for example, stated that the “First person perspective captures the individualistic/ survival of the fittest nature of the pandemic – everyone against everyone else”, while participant 1 commented that “I like the use of first person, the sense of this being a lived experience”. Equally prominent and interesting were the comments on “dander”. Participant 3, made the following comment which highlighted an interesting tension between the poetic use of the term and its appropriateness:

I loved the use of ‘dander’ for its playfulness but then immediately worried if this was too flippant an interpretation and if, in fact, it was an appropriate word to use in the poem at all.

Speaker is terrified but unable to acknowledge (until the end) terror on the part of others, only recognises the frenzy of the desire to stockpile while speakers’ own feelings are attributed to mere irrationality. (participant 1)

Does this imply that the other person is also having the same feelings of fear about the narrator? (participant 2)

Perhaps the speaker was generally more prone to this kind of extreme behaviour? Or was perhaps immuno-compromised or elderly (or lived with someone who did). (participant 4)

I think the poem reflect the more extreme responses to covid, which was to become extremely afraid of the outside, introverted and reclusive (participant 4)

[/ …] speaker trying to reassure themselves but also acknowledge alternative viewpoints, that others do not believe COVID poses a real threat (participant 6)

5.3. Group discussion

My analyses in the following sub-sections focus on responses generated during the reading group discussion. Here, I focus on three themes that emerged from coding: fear and proximity, and different types of self and other-orientation.

5.3.1. Fear and proximity

In their responses and discussion, several participants drew attention to how the language of the poem brought together the physical and the proximal in an unexpected way. Participant 2 commented on the “language of feverishness and heat”, while participant 1 commented on how they felt that there was a tension between how words associated with proximity such as “breath”, “sweat”, “scent” and “clothes” might be generally used, and how they were specifically used in a covid poem:

but then it’s [the use of these words] very contrasted with actually being about fear and stuff so I thought that it was an interesting contrast cos (sic) if those words were by themselves I wouldn’t have necessarily think about them in a negative way but then obviously in the way it is.

The effect of this kind of foregrounding (here a type of external deviation) appears particularly strong. Participant 1 suggested that these words, which would normally be used to describe “someone you know”, seemed disconnected and sinister when used in this context. Equally, participant 2 drew on the metaphor of a hunt to describe her response to “dander” and “scent”:

I guess for me that dander and scent are kind of are things you talk about an animal scenting another animal kind of thing but then fairly soon after that the kind of like the idea of catching and the word tail connotes proximity kind of put me in that like predator-prey mindset.

Participant 2 here extends her use of the hunt metaphor, finding a cohesive connection to the poem’s use of “tail”. For participant 2, the I-you binary becomes framed within the metaphor and its associated entity roles of predator and prey that drive the events described to the end of the poem along its various orientational paths: “it’s not just another person being near you […] but again they are quite predatory”.

Connections were also made between the verb choices with their emphasis on the physical and proximal and the embodied experience of reading the poem. Participant 3 described the poem as “accelerating in terms of um (sic) increasing amount of fear and paranoia”, while participant 1 spoke of imagining a “zombie apocalypse” triggered by words such as “lurched”. Participant 4 explicitly drew together the impact of the language choices within the frame of an intertextual connection with “night of the living dead that old zombie you know they’re all outside the supermarket trying to get in I think that was what it reminded me of”. This latter comment provides a neat example of the interpretative effect arising from the triggering of a supermarket schema in the poem.Footnote4

5.3.2. Self-orientation

The second research question aimed to examine how readers connected the reading of the poem to their own pandemic experiences. Inductive coding of the reading group data revealed that participants’ self-oriented talk was either internal (focusing on a personal response to the poem) or external (relating to a pandemic experience – either past or current). This sub-section analyses some patterns that emerged in data coded as external self-oriented talk.

Several participants made use of the supermarket reference to refer back to and reflect on their own experience of visiting and shopping in supermarkets during the pandemic. Participant 4 spoke of the.

fear and just the sense of the unknown around um those really early days of the pandemic June I don’t know if you remember like the first your first trip to the supermarket when it had all kicked off it was just it was terrifying um coz (sic) it felt like other people were such a huge and unknown threat.

Equally, participant 2 outlined how the poem reminded her of the ways that she had automatically felt suspicious of others, particularly those who were not being “as cautious [as] you’d like them to be and maybe you’d see them three times over the course of your shop”. Other participants felt that the poem also gave them a space to reflect on how the pandemic had affected their behaviour at the time. Participant 5 commented that reading the poem had brought back memories of a pandemic-induced anxiety around others: “[I] reflected on my first trip to the supermarket um (sic) and my behaviour and how paranoid I was in that queue”. The evaluative language of the poem also made participants aware of their own behaviour towards others, as rational as it may have seemed at the time. Participant 5 commented on their treatment towards “that person that was going the wrong way down the aisle and […] the judgment that I made upon them”, and participant 1 outlined how for them, the pandemic “pitted everybody against each other and everybody else becomes a threat and you have to protect yourself”.

On occasion, participants used the setting of the poem as a springboard for exploring other locations and situations that featured prominently in the pandemic for them. Participant 5 spoke of how the poem had brought about “flashbacks of going into school and them taking my temperature at the door” along with the ensuing panic of the implications of self-isolation. Participant 2, like many people with vulnerable and/or shielding family and friends, spoke of how the experience depicted in the poem had triggered the situation her grandmother, “as a severe risk”. For both of these participants, reading the poem helped them to understand and make sense of the heightened emotions that they had felt during the pandemic.

5.3.3. Other-orientation

The final research question aimed to examine the extent to which reading the poem helped readers to understand the experiences of others. In the data, comments that aligned with this research question were coded depending on whether participants positioned themselves explicitly with the poem’s speaker or an inferred participant in the world of the poem, or with some extra-textual (and often generic) entity. For the former, participant 6 felt that the poem helped them to understand “the self-reflective” nature of the speaker, while participant 1 accepted that the speaker’s behaviour, read now at somewhat of a distance from the pandemic, made the reader reflect on the fact that “everybody else was just buying their toilet rolls and stockpiling”, or as participant 5 reflected, “the other person was also in a panic and was rushing you know to almost get that shop over and done with”.

Participants who focused on an extra-textual entity often discussed situations by adopting an empathetic stance. Participant 6 argued that reading the poem made them reflect on the different kinds of what seemed “irrational” behaviours displayed by others during the various stages of the pandemic, but which nonetheless now appeared justified, while participant 3 outlined how the poem helped them to understand how “people certainly by me who are [still] wearing mask[s in ]the supermarket” might be feeling and how for some, the panic of the initial lockdown period still remained. Observing the potentially sensitive nature of covid fiction, the same participant discussed how reading the poem had itself made them consider the effect that covid poetry might have on a reader who knew someone “who had died as a result of covid”.

6. Discussion and conclusion

My analysis in this article highlights several findings. First, drawing on foregrounding theory reveals that there are several distinctive and textually salient features of “The new shape of fear”. Specifically, these are particular groups of words related to themes such as fear, proximity, the patterning of the pronouns “I” and “you”, and stance of the speaker whose consciousness experiences the pandemic and others who form the world of the poem. These are foregrounded here but we might also hypothesise that they – or very similar ones – would be present in other covid poems and collections. In addition to the various paratextual features that frame the poem, analysis of data generated through questions and reading group discussion demonstrates that foregrounded language features were viewed as attentionally salient and were commented on by participants. Although participants did respond to the poem in idiosyncratic as well as more consensual ways, they largely did so with reference to the same set of language features.

My analysis also demonstrates that both equivalent and non-equivalent responses may be understood through the same conceptual framework. The notion of a schema seems particularly useful in examining the kinds of knowledge frames that appear to be triggered through participants’ engagement with the poem. In the case of “The new shape of fear”, comments and discussion highlighted the reference to the supermarket, which appeared to trigger a supermarket schema and led participants to reflect both on their own experiences and on those of others. In such cases, the discussion seemed to either confirm an existing schema held by participants as they remembered (schema preservation or reinforcement), enlarge the schema through the addition of new facts and opportunities to reflect (schema accretion), or alter the schema, sometimes radically, so as to make a participant re-evaluate an existing knowledge frame (schema disruption or refreshment).Footnote5 Although the poem clearly positioned readers to draw on schemas that were pandemic specific, participants’ responses highlighted that the poem also triggered associated schemas related to other broader areas such as family.

The ways in which the poem was interpreted by the participants also relied, to an extent, on the co-negotiation and construction of meaning as participants built on the responses of each other, using their own personal understanding of the poem and the pandemic experiences it triggered, and aligned their feelings to those others may have experienced. This process meant that the mental representations of the poem as they were discussed by participants became reified and drawn on as contextual knowledge that was used for further reflection. This phenomenon could be seen in in participant 2’s telling remark that reading and discussing the poem “made me reflect on how not only how I treated other people but how other people might have seen me”. Participants thus aligned themselves within the world of the poem but used their responses to reflect on broader issues related to the effect of the pandemic. This bidirectionality, what Lahey (Citation2019, p. 54) terms a “cognitive feedback loop”, has been demonstrated to be a feature of reading group discourse particularly related to texts that focus on traumatic topics (see for example Canning, 2017) and it would appear from the data that this could well be a defining feature of covid fiction/covid poetry. Both the data discussed in this article and from the other questions (2 and 3) that were answered demonstrate that the poem helped participants to reflect on and make sense of how others may have experienced the pandemic. It is therefore possible that covid poetry may have a broader role to play in helping readers to view the pandemic from a less subjective vantage point and to promote empathy.

Overall, then, this article marks an important first step in the study of an emerging and likely to be significant literary genre. The integrated analysis of text and reader response data highlights several key areas that could be developed in future work by examining a larger corpus of covid poetry and covid fiction and by investigating other ways in which responses to literary representations of covid are reported and discussed by readers. Of course, there are some wider issues and questions that are beyond the scope of this article: for example, it remains unclear at this stage how homogenous covid fiction will be as it develops as a genre; and despite the fact that lockdown circumstances and general anxiety over the pandemic were near universal (Crawford & Crawford, Citation2021), it should be remembered that there is no such thing as a single covid experience (see Clayton et al., Citation2020; Dickerson et al., Citation2021) and so individuals are likely to read covid texts in different as well as similar ways. This study also took place relatively close to the pandemicFootnote6 and it remains uncertain as to how time and distance might impact on the development of the genre, on how the pandemic is commemorated, and on the demand and appetite for reading covid fiction; as participant 1 noted “I was just wondering if we would be responding to it [the poem] differently this time last year when we were like just out of lockdown”.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Of course the choice of participants also meant that they might respond to the poem in ways atypical of more general readers. For the purpose of this study, however, a readiness to respond to the poem was more important than generalisability. Approval for the study was granted by the ethics committee of the College of Business and Social Sciences at Aston University (approval number: SSH-21/22-018). All participants provided informed consent before the research began.

2 These questions were repeated for another poem in the collection that the participants also read. This article, however, only reports on reading and discussion related to “The new shape of fear”.

3 The British National Corpus (BNC) contains over 96,000,000 words of spoken and written English from a range of text types. The corpus was accessed using Sketch Engine (http://www.sketchengine.eu).

4 The reference to Night of the Living Dead was, however, erroneous as it was a later zombie film Dawn of the Dead that was set in a shopping mall.

5 See Stockwell (Citation2020, p. 107) for further discussion of these terms.

6 At the time of writing (October 2022), we are still arguably in the pandemic, although at a distance from the intensity of those first lockdown days.

References

- Acim, R. (2021). Lockdown poetry, healing and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 34(2), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2021.1899629

- Bate, J., & Schuman, A. (2016). Books do furnish a mind: The art and science of bibliotherapy. The Lancet, 387(10020), 742–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00337-8

- Bell, A., Ensslin, A., van der Bom, I., & Smith, J. (2019). A reader response method not just for ‘you’. Language and Literature: International Journal of Stylistics, 28(3), 241–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947019859954

- Bell, K. (2021). Do you know how kind I Am? Leafe Press.

- Boucher, A., Giovanelli, M., & Harrison, C. (2020, October 5). How reading habits have changed during the Covid-19 lockdown. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/how-reading-habits-have-changed-during-the-Covid-19-lockdown-146894

- Bravo, L. (2020, May 19). How poetry came to save us in lockdown. Penguin. https://www.penguin.co.uk/articles/2020/may/lockdown-poetry-phenomenon-pharmacy.html

- Brewster, L. (2016). More benefit from a well-stocked library than a well-stocked pharmacy: How do readers use books as therapy? In P. Rothbauer, K. Skjerdingstad, & E. F. McKechnie (Eds.), Plotting the Reading experience: Theory/practice/politics (pp. 167–182). Wilfred Laurier University Press.

- Caleshu, A., & Waterman, R.2021). Poetry & Covid-19: An anthology of contemporary international and collaborative poetry. Shearsman Books.

- Clayton, C., Clayton, R., & Potter, M. (2020). British families in lockdown: Initial findings. Leeds Trinity University/UKRI.

- Crawford, P., & Crawford, J. O. (2021). Cabin fever: Surviving lockdown in the coronavirus pandemic. Emerald Publishing.

- Denscombe, M. (2021). The good research guide: Research methods for small scale social sciences projects, 7th ed. Open University Press.

- Dera, J. (2021). Evaluating poetry on COVID-19: Attitudes of poetry readers toward corona poems. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 34(2), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2021.1899630

- Dickerson, J., Kelly, B., Lockyer, B., Bridges, S., Cartwright, C., Willan, K., Shire, K., Crossley, K., Bryant, M., Sheldon, T. A., Lawlor, D. A., Wright, J., McEachan, R. R. C., & Pickett, K. E. (2021). Experiences of lockdown during the Covid-19 pandemic: Descriptive findings from a survey of families in the Born in Bradford study’, [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Research, 5, 228. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16317.2

- Emmott, C., Alexander, M., & Marszalek, A. (2017). Schema theory in stylistics. In M. Burke (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of stylistics (pp. 268–283). Routledge.

- Erikson, K. (1995). Notes on trauma and community. In C. Caruth (Ed.), Trauma: Explorations in memory (pp. 183–199). Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Fowler, F. J. (2009). Survey research methods, 4th ed. Sage.

- Fox, K. (2021). The oscillations. Nine Arches Press.

- Gellatly, J., Bower, P., Hennessy, S., Richards, D., Gilbody, S., & Lovell, K. (2007). What makes self-help interventions effective in the management of depressive symptoms? Meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychological Medicine, 37(9), 1217–1228. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707000062

- Gibbons, A. (2011). This is not for you. In J. Bray, & A. Gibbons (Eds.), Mark Z. Danielewski (pp. 17–32). Manchester University Press.

- Gray, E., Kiemle, G., & Davis, P. (2015). Making sense of mental health difficulties through live Reading: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experience of being in a reader group. Arts & Health, 3015, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2015.1121883.

- Hale, J. (2021). Shield. Verve Poetry Press.

- Hanauer, D. I. (2001). What we know about Reading poetry: Theoretical positions and empirical research. In D. Schram, & G. Steen (Eds.), Psychology and sociology of literature: In honor of Elrud Ibsch (pp. 107–128). John Benjamins.

- Herman, D. (1994). Textual ‘you’ and double deixis in Edna O’Brien’s A Pagan Place. Style, 28(3), 378–410.

- Johnson, D. (2012). Transportation into a story increases empathy, prosocial behavior, and perceptual bias toward fearful expressions. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 150–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.005

- Jones, M. (2020). 111 haiku for lockdown. Infinity Books.

- Keniston, A., & Follansbee Quinn, J. (Eds.). (2010). Literature after 9/11. Routledge.

- Kidd, D. C., & Castano, E. (2017). Different stories: How levels of familiarity with literary and genre fiction relate to mentalizing. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 11(4), 474–486. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000069

- Lahey, E. (2019). World-building as cognitive feedback loop. In B. Neurohr, & L. Stewart-Shaw (Eds.), Experiencing fictional worlds (pp. 53–72). John Benjamins.

- Langacker, R. (2008). Cognitive grammar: A basic introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Leech, G. (1970). ‘This bread I break’: Language and interpretation. In D. C. Freeman (Ed.), Linguistics and literary style (pp. 119–128). Rinehart and Winston.

- Leech, G., & Short, M. (2007). Style in fiction: A linguistic introduction to English fictional prose, 2nd ed. Longman.

- Mukařovský, J. (1964). Standard language and poetic language. In P. L. Garvin (Ed.), A Prague school reader on esthetics, literary structure, and style (pp. 17–30). Georgetown University Press.

- Nell, V. (1988). Lost in a book: The psychology of reading for pleasure. Yale University Press.

- Oatley, K. (1994). A taxonomy of the emotions of literary response and a theory of identification in fictional narrative. Poetics, 23(1-2), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-422X(94)P4296-S

- Oatley, K. (2016). Fiction: Simulation of social worlds. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(8), 618–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.06.002

- Outka, E. (2019). Viral modernism: The influenza pandemic and interwar literature. Columbia University Press.

- Patnaik, A. (2022). The world poetics of lockdown in pandemic poetry. Journal of World Literature, 7(1), 70–86. https://doi.org/10.1163/24056480-00701008

- Roberts, J. K., Pavlakis, A. E., & Richards, M. P. (2021). It’s more complicated than it seems: Virtual qualitative research in the COVID-19 era. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 160940692110029 https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211002959

- Sandifer-Smith, G. (2022). Empty trains. Broken Sleep Books.

- Saphra, J. (2021). One hundred lockdown sonnets. Nine Arches Press.

- Sharma, D. (2021). Reading and rewriting poetry on life to survive the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 34(2), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2021.1899631

- Shaw, C. (2021). Poetry saved my life: On writing about trauma. In I. Humphreys (Ed.), Why I write poetry (pp. 172–179). Nine Arches Press.

- Short, M. (1996). Exploring the language of poems, plays and prose. Longman.

- Steen, G. (1992). The empirical study of literary reading: Methods of data collection. Poetics, 20(5-6), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-422X(91)90025-K

- Stockwell, P. (2020). Cognitive poetics: An introduction, 2nd ed. Routledge.

- Swann, J., & Allington, D. (2009). Researching literary reading as social practice. Language and Literature, 18(3), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947009105852

- The Reading Agency. (2020). New survey says reading connects a nation in lockdown. https://readingagency.org.uk/news/media/new-survey-says-reading-connects-a-nation-in-lockdown.html

- Trott, V. (2017). Publishers, readers and the great War. Bloomsbury.

- Vezzali, L., Stathi, S., Giovannini, D., Capozza, D., & Trifiletti, E. (2015). The greatest magic of harry potter: Reducing prejudice’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 45(2), 105–121.

- Wall, W. (2021). Smugglers in the underground trade: A journal of the plague year. Doire Press.

- Whiteley, S., & Canning, P. (2017). Reader response research in stylistics. Language and Literature: International Journal of Stylistics, 20(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947010377950

- Witthaus, M. (2020). From a sheltered place. Wild Pressed Books.

- Wood, H. (2020, May 7). The books that could flourish in this pandemic era. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200506-the-books-that-might-flourish-in-this-time-of-crisis