ABSTRACT

Background

The paper explores an online poetry and mental health project titled “Surviving by Storytelling”. The paper reflects on the knowledge which has been iteratively generated during the project and considers the unique challenges to delivering these workshops online.

Methods

Research through design (RtD) methodology was used to evaluate the project, which involved reflective discussions between workshop facilitators and a review of the artefacts generated throughout the project.

Results

The results revealed five themes: poetry workshops should be therapeutic, but not psychotherapy; creating a safe space for stories to breathe; facilitators should consider their positioning as writers or experts in relation to attendees; managing the potential harms of poetic exploration; and managing the loss of interpersonal symbols and spaces.

Conclusion

The provision of online poetry workshops on the topic of mental health can present unique complexities and the results from this paper can help to inform future practice.

Background

The Surviving by Storytelling project was created with the focus of designing and delivering a series of poetry and creative writing workshops exploring topics related to mental health. Read (Citation2019) argues that what links the most effective approaches to working with people who experience mental health problems, is a humane understanding that validates the person’s responses as meaningful and inextricably linked to their experiences. This ethos underpinned Surviving by Storytelling since its inception. The project aimed to utilise elements of creative writing, poetry therapy (Mazza, Citation2017) and narrative therapy (White & Epston, Citation1990) to support people to explore and narrate the stories within their lives. All workshops were delivered by two facilitators bringing together expertise in creative writing and mental health.

The project sought to specifically offer participation in creative writing and poetic practice to communities who might ordinarily feel excluded from accessing creative opportunities, particularly people with mental health problems or learning disabilities who may experience stigma or a sense of disconnection from their social network or local community (Lawson et al., Citation2014; Parr, Citation2006).

The first of a new series of workshops were due to be delivered in spring 2020 but were adapted for online delivery due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the substantial impact the pandemic had on people’s lives. Online engagement was utilised by many arts and health practitioners during the early months of the pandemic. Examples of digital strategies include the use of apps to support mental well-being during the pandemic (Alexopoulos et al., Citation2020; Reyes, Citation2020), the digitalisation of cultural resources such as museums (Noehrer et al., Citation2021), the presentation of virtual theatre productions and the transition to online spaces for psychotherapy (Weinberg, Citation2020). Surviving by Storytelling was very much in its infancy at the outbreak of the pandemic. Therefore, this paper utilises the principles of research through design to reflect upon the process of designing and implementing these workshops in order to generate new knowledge. This new knowledge will contribute to the development of future workshops and explore some of the unique challenges encountered when delivering poetry workshops online.

Research approach: research through design (RtD)

RtD is characterised by considering research as an iterative process, valuing the knowledge gained as a product of people working together to design and create new things. The creative process and its outputs are both conceptualised as sources of knowledge (Zimmerman et al., Citation2007). The stages of RtD can be considered as analogous to that of action research, comprised of four distinct iterative stages of a learning cycle: planning, acting, observing and reflecting (Lewin, Citation1951). The planning and acting phases of Surviving by Storytelling have been ongoing since the inception of the project in 2018 and since that time the project has delivered approximately 30 different workshops, the vast majority of which have been online. Each workshop has provided new learning opportunities, which have influenced the design of successive workshops in line with the RtD approach (Kleinsmann et al., Citation2013). Following each workshop the facilitators have sought informal evaluations from participants and engaged in reflexive discussions to fully evaluate the workshops.

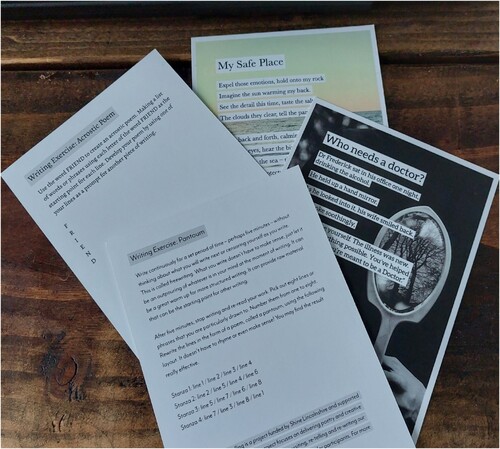

The outputs of the RtD process are artefacts, systems or conceptual frameworks (Gaver, Citation2012). Examples of the outputs from Surviving by Storytelling (see Appendixes A and B) include an example of workshop notes and postcards that were produced following the first series of workshops. The concept of the annotated portfolio, proposed by Bowers (Citation2012), was utilised to bring together the various artefacts from the project into a more systematic body of work. This involved reviewing artefacts generated from the project and identifying connections between them, considering them all as mutually informing. This process generated written notes which were then developed through reflective dialogues with supervisors and others working within the fields of poetry and creative writing. An example of such dialogue took place at the Nottingham poetry festival in 2022, where two of the workshop facilitators took part in a panel discussion exploring “The Power of Poetry” (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = y4G6uwdizfw).

In developing these reflections into concepts, the author was influenced by the idea of “strong concepts” proposed by Höök and Lowgren (Citation2012). This term describes “design elements abstracted beyond particular instances which have the potential to be appropriated by designers and researchers to extend their repertoires and enable new particular instances” (Höök & Lowgren, Citation2012, p. 23:25). The criteria for achieving a strong concept include consideration of whether the concept is novel and defensible, the emerging concept is able to contribute something original to the existing fields of knowledge, and the concept is grounded both empirically and theoretically.

Results

The RtD process generated five conceptual domains which appear highly salient in relation to these workshops. These are: poetry workshops should be therapeutic, but not psychotherapy; creating a safe online space for stories to breathe; facilitators should consider their positioning as writers or experts in relation to attendees; managing the potential harms of poetic exploration; and managing the loss of interpersonal symbols and spaces.

Poetry workshops should be therapeutic, but not psychotherapy

Throughout the design process, the tension of the workshops being therapeutic without necessarily being a distinct form of psychotherapy was often discussed. For the co-facilitators, this was a particular concern; whilst they had significant experience of facilitating groups, they did not hold any formal mental health training. It was also felt to be essential to manage the expectations of participants, many of whom may have been receiving mental health services or be on waiting lists for psychological therapies, which was unfortunately very common in England at the time the workshops were delivered (Limb, Citation2021; Punton et al., Citation2022). Conversely, the workshops were considered by facilitators to be uniquely therapeutic, with feedback from the early stages confirming that many participants experienced significant psychological benefits from taking part.

The activities and techniques used within the Surviving by Storytelling workshops were heavily influenced by the principles of poetry therapy (Mazza, Citation2017) and narrative therapy (White, Citation2007). However, the crucial issue is whether the workshops could be considered a form of psychotherapy. The fundamental assumption within any “talking cure” (Vehviläinen, Citation2019) is that people need to be provided with the space and opportunity to explore their subjective experiences, and these workshops offered this. However, the workshops did not follow a specific psychotherapeutic structure and even well-established evidence based psychotherapies can carry risks for those who attend (Paveltchuk et al., Citation2022), risks which may be more challenging to manage within a digital or online space (Hall et al., Citation2023).

Following these considerations, the decision was made to clearly state the position that these workshops were not being delivered as a form of psychotherapy. This is not to say that the workshops were not considered to be therapeutic; feedback from participants suggested that they were found to have many therapeutic benefits. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that the creative process itself, in the absence of any formal psychotherapeutic techniques can have a significant and sustained impact on mental well-being (Argyle, Citation2020).

Creating a safe online space for stories to breathe

The project was named Surviving by Storytelling to reflect the fundamental purpose of the workshops in supporting people to survive various traumas in their lives by providing a space for them to narrate and share their stories. Frank (Citation2010, p. 3) describes the importance of letting stories breathe, asserting that:

Stories work with people, for people and stories always work on people … stories breathe life not only into individuals but also into groups that assemble around the telling and believing of certain stories.

The process of being part of the group can allow stories to breathe and promote the associated therapeutic benefits (Argyle & Winship, Citation2015; Fuchs, Citation2006). A key function of poetry groups is often the opportunity to discuss and share emotions within a safe and supportive environment (Chamberlain, Citation2019). This resonates with the description by Many et al. (Citation2016, p. 717) of the creation of a “nest of emotional safety” within psychotherapy, referring to the way in which people craft a place of perceived safety in relationships with others around them. A sense of safety is a universal need and one which is essential to the success of any intervention or process that is considered to have therapeutic potential (Mair, Citation2021). Whilst there is evidence to suggest that creative practice programmes can be successfully adapted to online delivery (Levy et al., Citation2018), the creation of a space online is potentially complex, especially as online communication can lead to a decreased sense of empathy (Konrath et al., Citation2011) and for some people increased feelings of loneliness and isolation (Pinker, Citation2014).

Poems provide an insight into the internal worlds of others (Jones & Betts, Citation2016) and when shared within a group, poems can evoke a range of responses, reflections, projections and feelings from those listening (Fuchs, Citation2006). This process may also mean that group members are confronted with difficult and potentially highly distressing topics (McGarry & Bowden, Citation2017). In order for the Surviving by Storytelling workshops to function optimally, these narratives needed to be met with compassion and without judgement (McKim, Citation2006). Compassion, however, as well as being something which is individually expressed, is also nurtured within a space, amongst people through their shared relationships (Spandler & Stickley, Citation2011). In online spaces this process of nurturing may be inhibited if people find it difficult to assert themselves or feel excluded from the conversation (Gordon et al., Citation2020).

Facilitators should consider their positioning as writers or experts in relation to attendees

During the Surviving by Storytelling project, the facilitators were mindful of not positioning themselves as experts, as this may have created a false separation between facilitators and workshop participants. The facilitators were keen to emphasise that they considered themselves primarily as fellow writers who were also influenced and shaped by the group, rather than as experts. This ethos resonates with the concept of creative practice as mutual recovery (Crawford et al., Citation2013), which informed the development of the workshops, and which proposes that all those involved in a project grow as a result of being alongside each other through the creative process.

The concept of creative practice as mutual recovery is built on the understanding that creative processes are based on reciprocal interactions and that positive impacts on well-being are, in part, due to the process of sharing an experience with others (Argyle, Citation2020). Therefore, all participants present within the group are considered to have benefitted from the process, including those in leading or facilitating roles (Jensen & Lo, Citation2018). In this context the facilitator is recognised as a complex being, who brings their own history, trauma and struggles into this relationship (Engel et al., Citation2008).

The response of facilitators throughout the workshops was also carefully considered. Participants frequently produced work which held significant emotional resonance, compelling the facilitator to make further enquiries or share their own reflections with the aim of deepening the dialogue. However, at times this was felt to be inappropriate as any potential emotional outpourings triggered for the participant by this deeper exploration could be challenging for the facilitator to manage or contain within the online space.

Managing the potential harms of poetic exploration

Exploring difficult personal experiences or existential crises are fundamental components of both psychotherapy and poetry (Wilkinson, Citation2009). In relation to poetry, Bolton and Latham (Citation2004, p. 106) suggest that all poems serve to break a silence which had previously never been overcome; arguing that “poetry can only be written from the otherwise most difficult to reach parts of oneself and one’s world.” This process of introspection, whilst potentially highly therapeutic, is also associated with significant risks for those undertaking this exploration, particularly if individuals begin to feel overwhelmed and unable to contain heightened levels of distress which have been evoked (Nutt & Sharpe, Citation2008). McKim (Citation2006) suggests that poems bring us closer to our imaginations and memories, and whilst this can be pleasurable it also has the potential to be distressing and overwhelming. Therefore, a significant amount of consideration was given to how the activities utilised in the workshops could be presented and undertaken safely by participants but still prove powerful and foster a creative and introspective milieu.

Narrative-based practices have been described as “conversations inviting change” (Launer, Citation2018). In this sense, narrative conversations or approaches are not considered primarily as interventions or problem-solving mechanisms, but rather as a way of creating spaces and opportunities within which participants can consider their problems or experiences from different perspectives. In designing the workshop activities, the decision was made to position these in a similar way, as invitations to write and explore. This notion of the invitation was considered important as the workshops were designed to offer opportunities to explore lived experiences and narratives, rather than focusing on generating written content.

The facilitators tried to ensure that the workshops focused on exploring positive aspects of people’s lives and experiences, rather than anything explicitly distressing. For example, a poetry prompt which asked participants to “Imagine the concept of a mirror, reflecting images and aspects of ourselves. Pick an object within your house which is not a mirror, but which reflects a part of your sense of who you are”, could be adapted to “Imagine the concept of a literal mirror, reflecting images and aspects of ourselves. Pick an object within your house which is not a literal mirror, but which reflects a positive aspect of your life”.

However, this approach proved difficult to enact and rather counterintuitive to the ethos of the project. The most benign-sounding topic to the facilitator may hold significant power for a participant and have the potential to trigger distress. Steinberg (Citation2004) captures this issue in reiterating that words do not always function as universal signifiers and often carry more than their immediate meanings, suggesting that words and phrases can be archetypes, loaded with multiple meanings, implications, and ambiguities.

In order for the project to be effective, workshop activities needed to provoke reflections from the participants and it could be argued that some level of discomfort is required in order to achieve this. Fuchs (Citation2006, p. 207) proposes that the process of writing poetically “destructs the certainties of everyday life and puts us into an imaginal in between space in which there is no guarantee, only the hope to find a shelter”. Therefore, to maintain safety, the workshops focused on the quality of the shelter which the group environment could provide. Opportunities to “opt out” of exercises were built-in, as was the option to explore any topic as deeply or as superficially as each participant felt was safe for them.

Managing the loss of interpersonal symbols and spaces

Social interaction exists on a foundation of agreed symbols which help to orientate the context of that interaction (Blumer, Citation1986). For example, shaking hands can symbolise mutual respect and trust; this is a gesture built upon shared values and understanding of this symbol (Long et al., Citation2022). However, within the online space there is an absence of, or a more limited range of, such agreed symbols. This is especially true when people are communicating solely using an online platform’s “chat” function and verbal and visual cues, such as accent, tone of voice and appearance, are removed (Tagg, Citation2015). Thus the communication skills required in online workshops can be quite distinct from those required when engaging with someone face-to-face (Statton et al., Citation2016).

Some participants might experience the increased sense of anonymity afforded by online communication as liberating or easier to manage than face-to-face communication. Others might miss opportunities to engage in natural verbal communication which can be offered in a face-to-face workshop environment (Jensen, Citation2016). This tension in relation to anonymity permeated through other aspects of the project, particularly the issue of whether participants kept their cameras on during the workshops. Some chose to keep their cameras off throughout and only sporadically engaged verbally with the group. However, these camera-shy participants were also some of the most effusive in their evaluations of the workshops, finding them helpful and beneficial for their mental health. This raises some questions in regard to the impact of “being on camera” for some people and how this may impact the authenticity or openness of their engagement. Goffman (Citation1978) proposed that people “perform” to present the image of themselves felt to be most desirable within a social context. This metaphor of performance includes the notion of front stage and backstage; front stage being that which is presented to an audience and backstage where no performance is necessary (Goffman, Citation1978). In the context of online workshops, the online space within the workshop becomes the front stage. Each participant is a performer and an audience member. The physical distance between the audience and the performer may mean that people are more able to conceal, embellish or hide elements of their personality (Bullingham & Vasconcelos, Citation2013). Moreover, in some cases the transition to performing in an online space may increase the level of scrutiny upon one’s own performance; Miller and Sinanan (Citation2014) describe how people using a webcam often spend more time looking at their own image than that of their interlocutors.

Participants and facilitators were both aware that online workshops did not provide spaces or opportunities for what might be considered the “small talk” or phatic conversation which can surround group events. Anthropologically, phatic conversation has a rich history as a ritual within many cultures. It describes conversation which is free and aimless. Although what is being said is not particularly important, the act of engaging in phatic conversation is important for enhancing relationships (Burnard, Citation2003). Long et al. (Citation2022) discuss the way in which the pandemic disrupted and restricted this potential for spontaneous interactions. These interactions proved difficult to accommodate during the Surviving by Storytelling workshops. For example, if a participant resonated with a poem or piece of writing read aloud by another participant, they might wish to explore this further, but might not wish to have this discussion in front of the rest of the group. It would be possible to organise smaller “break out rooms” for attendees to talk freely, but this runs the risk of becoming a choreographed element of the workshops, potentially limiting creative and reflective discussions in these spaces (North, Citation2007).

Implications for future research and practice

The Surviving by Storytelling project, alongside a variety of other creative therapeutic online initiatives, began out of necessity during the COVID-19 pandemic (Riches et al., Citation2024). However, the knowledge which emerged from these workshops is relevant beyond pandemic epoch and can provide a valuable orientation for future online creative practice and research. Online workshops have the potential to increase accessibility and provide an experience of social connectedness (Wiederhold, Citation2020), with increasing numbers of facilitators and organisations utilising online groups to engage individuals who may not be able to attend face to face events (Harrison et al., Citation2023; Wilson et al., Citation2022).

However, online spaces also present unique and complex issues in relation to aspects such as safety, inclusion, and communication (Kelly-Hedrick et al., Citation2020; Trupp et al., Citation2022). Cummings (Citation2022) introduces the concept of “Zoom Doom” to describe the discomfort and fatigue individuals can experience when communicating over video calls, which are often resulting from the lack of shared connection with others. Online creative workshops are complex interpersonal processes (Acai et al., Citation2016) and there remains limited evidence to guide creative practitioners. The findings of this research provide some insights into how facilitators might consider some of the complexities of facilitating workshops online but also highlight the need for further research to understand how online groups can be most effectively and therapeutically designed and delivered.

Conclusion

Arts and creative practice can hold significant therapeutic potential for people (Stickley, Citation2010), however, understanding how to facilitate workshops, such as those described in this paper, can be complex. This is especially true for workshops delivered online which may be an unusual experience for both facilitators and attendees (Geréb Valachiné et al., Citation2023). Utilising the RtD methodology has enabled an evaluation of the Surviving by Storytelling project and generated new knowledge which can inform not only future creative writing workshops, but also inform other online creative practices. The findings are grouped into five themes: poetry workshops should be therapeutic, but not psychotherapy; creating a safe online space for stories to breathe; facilitators should consider their positioning as writers or experts in relation to attendees; managing the potential harms of poetic exploration; and managing the loss of interpersonal symbols and spaces. These findings provide valuable insights into the dynamics of facilitating creative workshops online and highlight the need for further research to better understand how facilitators can manage the complexities of online spaces.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acai, A., McQueen, S. A., Fahim, C., Wagner, N., McKinnon, V., Boston, J., Maxwell, C., & Sonnadara, R. R. (2016). ‘It's not the form; it's the process’: A phenomenological study on the use of creative professional development workshops to improve teamwork and communication skills. Medical Humanities, 42(3), 173. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2015-010862

- Alexopoulos, A. R., Hudson, J. G., & Oluwatomisin, O. (2020). The use of digital applications and COVID-19. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(7), 1202–1203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00689-2

- Argyle, E. (2020). Creative practice as a mutual route to well-being. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 24(4), 235–239. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-05-2020-0035

- Argyle, E., & Winship, G. (2015). Creative practice in a group setting. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 19(3), 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-04-2015-0014

- Blumer, H. (1986). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Univ of California Press.

- Bolton, G., & Latham, J. (2004). Every poem breaks a silence that had to be overcome': The therapeutic role of poetry writing. In G. Bolton, S. Howlett, C. Lago, & J. K. Wright (Eds.), Writing cures (pp. 106–123). Brunner-Routledge.

- Bowers, J. (2012). The logic of annotated portfolios: communicating the value of' research through design. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference.

- Bullingham, L., & Vasconcelos, A. C. (2013). ‘The presentation of self in the online world’: Goffman and the study of online identities. Journal of Information Science, 39(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551512470051

- Burnard, P. (2003). Ordinary chat and therapeutic conversation: Phatic communication and mental health nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10(6), 678–682. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00639.x

- Chamberlain, D. (2019). The experience of older adults who participate in a bibliotherapy/poetry group in an older adult inpatient mental health assessment and treatment ward. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 32(4), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2019.1639879

- Crawford, P., Lewis, L., Brown, B., & Manning, N. (2013). Creative practice as mutual recovery in mental health.

- Cummings, L. (2022). Avoiding Zoom Doom: Crating online workshops with design thinking. In S. R. Laura Gray-Rosendale (Ed.), Go online!: Reconfiguring writing courses for the new, virtual world (pp. 97–113). Peter Lang International Academic Publishers.

- Engel, J. D., Zarconi, J., Pethtel, L., Missimi, S., & Charon, R. (2008). Narrative in health care: Healing patients, practitioners, profession, and community. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Frank, A. W. (2010). Letting stories breathe: A socio-narratology. University of Chicago Press.

- Fuchs, M. (2006). Between imagination and belief: Poetry as therapeutic intervention. In S. Levine & E. Levine (Eds.), Foundations of expressive arts therapy: Theoretical and clinical perspectives (pp. 195–211). J. Kingsley Publisher.

- Gaver, W. (2012). What should we expect from research through design? In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, Texas, USA. https://doi.org/10.1145/2207676.2208538

- Geréb Valachiné, Z., Dancsik, A., Fitos, M. M., & Cserjési, R. (2023). Online art therapy–based self-help intervention serving emotional betterment during COVID-19. Art Therapy, 40(3), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2022.2140566

- Goffman, E. (1978). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday Publishers.

- Gordon, H. S., Solanki, P., Bokhour, B. G., & Gopal, R. K. (2020). “I’m not feeling like I’m part of the conversation” Patients’ perspectives on communicating in clinical video telehealth visits. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(6), 1751–1758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05673-w

- Hall, S. B., Bartley, A. G., Wenk, J., Connor, A., Dugger, S. M., & Casazza, K. 2023 Rapid transition from in-person to videoconferencing psychotherapy in a counselor training clinic: A safety and feasibility study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Counseling & Development, 101, 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12439

- Harrison, S. L., Lawrence, J., Suri, S., Rapley, T., Loughran, K., Edwards, J., Roberts, L., Martin, D., & Lally, J. E. (2023). Online comic-based art workshops as an innovative patient and public involvement and engagement approach for people with chronic breathlessness. Research Involvement and Engagement, 9(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-023-00423-8

- Höök, K., & Lowgren, J. (2012). Strong concepts. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 19(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1145/2362364.2362371

- Jensen, E. B. (2016). Peer-review writing workshops in college courses: Students’ perspectives about online and classroom based workshops. Social Sciences, 5(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5040072

- Jensen, A., & Lo, B. (2018). The use of arts interventions for mental health and wellbeing in health settings. Perspectives in Public Health, 138(4), 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913918772602

- Jones, E., & Betts, T. (2016). Poetry, philosophy and dementia. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 11(2), 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-10-2015-0050

- Kelly-Hedrick, M., Stouffer, K., Kagan, H. J., Yenawine, P., Benskin, E., Wolffe, S., & Chisolm, M. (2020). The online art museum [Version 2]. MedEdPublish, 9(1), 179. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000179.2

- Kleinsmann, M., Maier, A., van Dijk, J., & van der Lugt, R. (2013). Scaffolds for design communication: Research through design of shared understanding in design meetings. Artificial Intelligence for Engineering Design, Analysis and Manufacturing, 27(2), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0890060413000024

- Konrath, S. H., O'Brien, E. H., & Hsing, C. (2011). Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(2), 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377395

- Launer, J. (2018). Narrative-based practice in health and social care: Conversations inviting change (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Lawson, J., Reynolds, F., Bryant, W., & Wilson, L. (2014). ‘It’s like having a day of freedom, a day off from being ill’: Exploring the experiences of people living with mental health problems who attend a community-based arts project, using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(6), 765–777. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313479627

- Levy, C. E., Spooner, H., Lee, J. B., Sonke, J., Myers, K., & Snow, E. (2018). Telehealth-based creative arts therapy: Transforming mental health and rehabilitation care for rural veterans. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 57, 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.08.010

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers. Harpers.

- Limb, M. (2021). Waiting list for hospital treatment tops “grim milestone” of five million. BMJ, 373, n1497–n1497. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1497

- Long, E., Patterson, S., Maxwell, K., Blake, C., Bosó Pérez, R., Lewis, R., McCann, M., Riddell, J., Skivington, K., Wilson-Lowe, R., & Mitchell, K. R. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social relationships and health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 76(2), 128–132. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2021-216690

- Mair, H. (2021). Attachment safety in psychotherapy. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(3), 710–718. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12370

- Many, M. M., Kronenberg, M. E., & Dickson, A. B. (2016). Creating a “nest” of emotional safety: Reflective supervision in a child-parent psychotherapy case. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(6), 717–727. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21603

- Mazza, N. (2017). Poetry therapy: Theory and practice. Routledge.

- McGarry, J., & Bowden, D. (2017). Unlocking stories: Older women’s experiences of intimate partner violence told through creative expression. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24(8), 629–637. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12411

- McKim, E. G. (2006). Poetry in the oral tradition. In S. K. L. a. E. G. Levine (Ed.), Foundations of expressive arts therapy: Theoretical and clinical perspectives (pp. 211–223). J. Kingsley Publishers.

- Miller, D., & Sinanan, J. (2014). Webcam. John Wiley & Sons.

- Noehrer, L., Gilmore, A., Jay, C., & Yehudi, Y. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on digital data practices in museums and art galleries in the UK and the US. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 236. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00921-8

- North, S. (2007). 'The Voices, the Voices': Creativity in Online Conversation. Applied Linguistics, 28(4), 538–555. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm042

- Nutt, D. J., & Sharpe, M. (2008). Uncritical positive regard? Issues in the efficacy and safety of psychotherapy. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 22(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881107086283

- Parr, H. (2006). Mental health, the arts and belongings. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 31(2), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2006.00207.x

- Paveltchuk, F., Mourão, S. E. d. Q., Keffer, S., da Costa, R. T., Nardi, A. E., & de Carvalho, M. R. (2022). Negative effects of psychotherapies: A systematic review. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(2), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12423

- Pinker, S. (2014). The village effect: Why face-to-face contact matters. Atlantic Books Ltd.

- Punton, G., Dodd, A. L., & McNeill, A. (2022). ‘You're on the waiting list’: An interpretive phenomenological analysis of young adults’ experiences of waiting lists within mental health services in the UK. PLoS One, 17(3), e0265542–e0265542. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265542

- Read, J. (2019). Making sense of, and responding sensibly to, psychosis. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 59(5), 672–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167818761918

- Reyes, A. T. (2020). A mindfulness mobile app for traumatized COVID-19 healthcare workers and recovered patients: A response to “the use of digital applications and COVID-19”. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(7), 1204–1205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00690-9

- Riches, S., Yusuf-George, M., Steer, N., Fialho, C., Vasile, R., Nicholson, S. L., Waheed, S., Fisher, H. L., & Zhang, S. (2024). Videoconference-based Creativity Workshops for mental health staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arts & Health, 16(2), 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2023.2184402

- Spandler, H., & Stickley, T. (2011). No hope without compassion: The importance of compassion in recovery-focused mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 20(6), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2011.583949

- Statton, S., Jones, R., Thomas, M., North, T., Endacott, R., Frost, A., Tighe, D., & Wilson, G. (2016). Professional learning needs in using video calls identified through workshops. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0657-6

- Steinberg, D. (2004). From archetypes to impressions: the magic of words. In H. G. Bolton, S. Howlett, C. Lago, & J. K. Wright (Eds.), Writing cures (pp. 44–57). Brunner-Routledge.

- Stickley, T. (2010). The arts, identity and belonging: A longitudinal study. Arts & Health, 2(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533010903031614

- Tagg, C. (2015). Exploring digital communication: Language in action. Routledge.

- Trupp, M. D., Bignardi, G., Chana, K., Specker, E., & Pelowski, M. (2022). Can a brief interaction with online, digital art improve wellbeing? A comparative study of the impact of online art and culture presentations on mood, state-anxiety, subjective wellbeing, and loneliness. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 782033–782033. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.782033

- Vehviläinen, S. (2020). Psychotherapy. Communication and Medicine, 16(2), 191–195. https://doi.org/10.1558/cam.41911

- Weinberg, H. (2020). Online group psychotherapy: Challenges and possibilities during COVID-19—A practice review. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 24(3), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1037/gdn0000140

- White, M. (2007). Maps of narrative practice. Norton.

- White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. Norton & Company.

- Wiederhold, B. K. (2020). Connecting through technology during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Avoiding “Zoom Fatigue”. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 23(7), 437–438. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.29188.bkw

- Wilkinson, H. (2009). The muse as therapist. Karnac Books.

- Wilson, A., Carswell, C., Burton, S., Johnston, W., Jennifer Baxley, L., MacKenzie, A., Matthews, M., Murphy, P., Reid, J., Walsh, I., Wurm, F., & Noble, H. (2022). Evaluation of a programme of online arts activities for patients with kidney disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare, 10(2), 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020260

- Zimmerman, J., Forlizzi, J., & Evenson, S. (2007). Research through design as a method for interaction design research. In HCI Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, California, USA. https://doi.org/10.1145/1240624.1240704

Appendices

Appendix B: Online poetry workshop plan

Workshop 1: Who am I?

Introduction

Ground rules:

No need to share

Camera on/off

Express not impress

Respect each other

Mention the need to complete the funder’s evaluation email

Setting the scene:

Overview of the workshops

Workshop 6 currently free (let us know how you want to fill this time)

Pop up events in the future

Warm-up

Explain the idea of free writing.

The idea is simply to write … Don’t stop for anything. Go quickly without rushing. Never stop to look back, to cross something out, to wonder how to spell something, to wonder what word or thought to use, or to think about what you are doing. If you can’t think of a word or a spelling, just use a squiggle or else write, “I can’t think of it.” Just put down something. The easiest thing is just to put down whatever is in your mind. If you get stuck it’s fine to write “I can’t think what to say, I can’t think what to say” as many times as you want; or repeat the last word you wrote over and over again; or anything else. The only requirement is that you never stop.

Peter Elbow, Writing Without Teachers, 1973

Ultimately, there are no rules to free writing – just make it your own and do what works for you.

Writing prompt:

If you were a place, what sort of place would you be?

Modern or traditional?

Busy or quiet?

Rural or urban?

Weather?

History?

If someone was to visit, what would they notice?

…

Sharing

Drawing your map

Group sharing on the opening stanza of “Song of the Open Road” by Walt Whitman.

Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road,

Healthy, free, the world before me,

The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.

Discussion prompts:

What tone does the poem set? How do you respond to this?

How do you feel about having a path ahead that could take you wherever you want to go?

Writing prompt:

Where does your “long brown path” lead? Remember, it can lead wherever you choose. Draw a map of where your long brown path leads to or the journey you might make along it. Respond in writing if you prefer.

Break

Sharing

Go round the group a seek feedback from participants and develop dialogue

Final thoughts, feedback and reflections