Abstract

Background: The opioid epidemic continues to erode communities across Pennsylvania (PA). Federal and PA state programs developed grants to establish Hub and Spoke programs for the expansion of medications for opioid use disorders (MOUD). Employing the telementoring platform Project ECHO (Extension for Community Health Outcomes), Penn State Health engaged the other seven grant awardees in a Collaborative Health Systems (CHS) ECHO. We conducted key informant interviews to better understand impact of the CHS ECHO on health systems collaboration and opioid crisis efforts. Methods: For eight one-hour sessions, each awardee presented their unique strategies, challenges, and opportunities. Using REDCap, program characteristics, such as number of waivered prescribers and number of patients served were collected at baseline. After completion of the sessions, key informant interviews were conducted to assess the impact of CHS ECHO on awardee’s programs. Results: Analysis of key informant interviews revealed important themes to address opioid crisis efforts, including the need for strategic and proactive program reevaluation and the convenience of collaborative peer learning networks. Participants expressed benefits of the CHS ECHO including allowing space for discussion of challenges and best practices and facilitating conversation on collaborative targeted advocacy and systems-level improvements. Participants further reported bolstered motivation and confidence. Conclusions: Utilizing Project ECHO provided a bidirectional platform of learning and support that created important connections between institutions working to combat the opioid epidemic. CHS ECHO was a unique opportunity for productive and convenient peer learning across external partners. Open dialogue developed during CHS ECHO can continue to direct systems-levels improvements that benefit individual and population outcomes.

Introduction

Opioids are involved in the majority of drug overdose deaths in the United States. Over 70,000 people died from a drug overdose in 2019, with 70.6% of these deaths attributed to an opioid. Citation1 These deaths, along with other opioid-related consequences such as non-fatal overdoses, infectious diseases, and crime have cost the nation $560 billion over the past ten years.Citation2 In the last decade, Pennsylvania (PA) has experienced increased drug overdose deaths, many of which were due to opioids.Citation3

In July 2017, PA received $26 million in federal funding through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to combat the opioid crisis in state-targeted response funds. Under the leadership of PA Department of Health (DOH) Secretary, Rachel Levine, PA DOH created Pennsylvania Coordinated Medication Assisted Treatment (PACMAT) grants, using part of those funds. The PACMAT grants financed development of Hub and Spoke systems to expand access to Medications for Opioid Use Disorders (MOUD). Despite its effectiveness, MOUD remains underutilized due to stigma surrounding patients and the medications themselves, disparate treatment access, and lack of provider education on best practices. Less than half of private treatment programs have adopted MOUD.Citation4–8 Within programs offering MOUD, only an estimated one-third of eligible patients receive MOUD.Citation4,Citation9 Additionally, treatment providers lack financial resources needed to support long-term patient engagement.Citation10,Citation11 Continuity is challenging when individuals are often treated at safety-net community-health clinics, which frequently lack electronic health record (EHR) functionality for data communication or aggregation ability.Citation12

A Hub and Spoke model of care represents a continuum of care ranging from primary medical services to specialty care, with systems in place to ensure that individuals with a specific health condition continue to receive life-saving medical services. The PACMAT Hub and Spoke systems were modeled on the success of the Vermont (VT) and Rhode Island (RI) programs,Citation13,Citation14 but operationalized differently. VT’s Hub and Spoke systems were entirely state funded and provided uniform services including standardized intake and transfer procedures; use of methadone, buprenorphine-naloxone, and vivitrol; and VT government employed supportive nursing and therapy staff per 100 Medicaid patients. RI created centers of excellence, which integrated peer recovery, counseling, and vocational support with all forms of MOUD. By contrast, PA hubs were heterogenous beyond a few guiding principles. All PACMAT recipients focused on access expansion, patient enrollment, sustained recovery, and reduction of overdose deaths. All hubs recruited spoke clinic sites, from within or outside the hub’s health system, with the ability to initiate and continue treatment with buprenorphine and extended-release naltrexone. To obtain funds, grantees were required to develop payment and sustainability plans through individual arrangements or collective advocacy. Beyond these guidelines, each PA Hub and Spoke system employed very different strategies, scales, and scopes of practice. Unlike VT and RI, PA hubs were not required to have all forms of MOUD or to provide treatment in a central location. Some hubs served as linkage to community-based care centers, while others were active opioid treatment programs and previously designated PA Opiate Centers of Excellence. As a result, the PACMAT grants formed a heterogeneous network of Hubs and Spokes across multiple health care delivery systems.

In May 2019, the Penn State Health PACMAT utilized supplementary funds to leverage a collective virtual partnership among the eight PACMAT grantees using Project ECHO (Extension for Community Health Outcomes). Penn State had previously utilized Project ECHO to connect primary care providers with a goal to increase access to MOUD; this model has been shown to achieve this goal by increasing the number of primary care providers waivered to prescribe and improving healthcare provider preparedness to treat OUD, specifically through advances in provider knowledge and self-efficacy.Citation15–18 Project ECHO provided a platform for PACMAT leadership to share their unique Hub and Spokes operations and practices. Because each PACMAT operates in a different geographic area of PA and uses diverse strategies personnel and electronic health records, Project ECHO fostered a collaborative learning environment to share best practices, discuss unique challenges, and brainstorm collective solutions. The purpose of this paper is to describe the use of Project ECHO to integrate and coordinate opioid crisis efforts across PA. Collectively, this series aimed to augment our collective influence with the PA DOH and other regulatory and financing stakeholders; to contextualize and strengthen individual and collective health systems efforts; and to design collective and empowering strategies to overcome obstacles to care, data collection, and financial sustainability.

Material and methods

Pennsylvania PACMAT

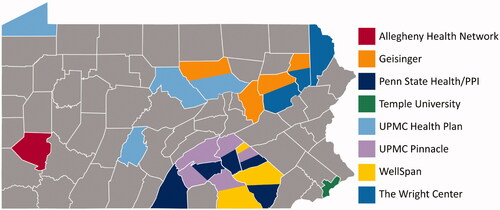

The PACMAT grants directly funded seven Hub and Spoke systems and partnered with the UPMC Health Plan who were awarded a separate but similar SAMHSA grant to its own Hub and Spoke system.Citation19 Therefore, eight programs were funded in 2017 and 2018 (). Leadership for each system met monthly with state personnel via telephone conference and quarterly at in-person meetings in Harrisburg, PA to share updates on their programs. Although these meetings were largely interactive, these networking meetings focused primarily on updating the state agency, rather than on collective, cross-organizational problem solving.

Table 1. PACMAT demographics.

Project ECHO

Project ECHO is a telementoring model that uses videoconferencing technology (Zoom) to create a real time “all teach, all learn” knowledge exchange that bolsters provider capacity to deliver best-practice care to underserved populations with increased self-efficacy, skills, and confidence.Citation16,Citation20 The ECHO model has four core principles, (1) use technology to leverage scarce resources, (2) share best practices to reduce disparities, (3) employ case-based learning to master complexity, and (4) monitor outcomes to ensure benefit. This model was chosen because unlike traditional learning, Project ECHO facilitates rapid dissemination of medical knowledge and increased capacity to deliver best-practice care by utilizing case-based, collaborative learning to support discussion of learners’ challenges and barriers to guideline implementation.

After launching our PACMAT program in November 2017, Penn State College of Medicine launched a separate SAMHSA funded Project ECHO initiative on MOUD in 2018 (grant TI081432) to build self-efficacy of providers to diagnose and treat OUD across PA.Citation21 Leveraging our existing ECHO infrastructure, we created a new learning platform with participation from PACMAT hub leadership, called the Collaborative Health System (CHS) ECHO. Given our existing connection to the PACMAT program, we were able to recruit CHS ECHO participants for this series by emailing the lead contact for each PACMAT program. The PACMAT lead was responsible for providing oversight of physical, mental, and social health services to expand and improve MOUD access within their network, but may or may not have been involved in direct patient care. In all cases, they participated and invited relevant staff to join as well on occasion. These included Addiction Medicine specialists, psychiatrists, project managers, physicians, and senior level executives.

A typical ECHO session targeting clinical providers features a patient case presentation followed by a 10–15 minute brief lecture. In contrast, CHS ECHO sessions featured a health system-based case rather than a patient case. At each session, a different PACMAT awardee was encouraged to present their system, covering hub and spoke characteristics and services, collection and management of provider and patient-level outcomes data, unique strengths, current challenges, and future goals. This allowed for all participants to gain a baseline understanding of the PACMAT, participate in discussion, find common ground, celebrate successes, and respond to challenges presented. Recommendations shared during CHS ECHO sessions were documented and provided to the presenting hub. The CHS ECHO met every other week for eight one-hour sessions.

Quantitative data collection

Using REDCap, a secure web application for survey data collection, parameters at baseline were collected in May 2019 to characterize the scope of the PACMAT network operations including academic affiliation and unified EHR for data extraction, as well as the total number of hub and spoke sites, MOUD waivered providers and number of patients served. At the conclusion of the series in September 2019, a post series survey was shared with all participants.

Key informant interviews

Due to low completion rates of the post series survey, seven months after CHS ECHO sessions concluded between the months of December 2019 and February 2020, a masters trained Project ECHO project manager (PM) reached out to CHS ECHO participants via email (n = 7) and conducted 30 minute telephone interviews with each participant. All seven CHS ECHO participants completed an interview. This PM did not have relationships with the participants/interviewees but provided technical assistance throughout CHS ECHO sessions. A semi-structured guide was written a priori by Project ECHO staff based on their collective decades long experience with ECHO programs and provider training. Two separate staff members authored the first drafts, and a board-certified Addiction Medicine physician revised them (see Supplement 1). The semi-structured guide was adapted from questions included in the post series survey to further explore the impact of CHS ECHO on their PACMAT efforts, share changes they implemented because of participating in CHS ECHO, describe challenges and barriers they faced, and comment on the sustainability of the CHS ECHO format.

Qualitative analysis

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by the PM using a naturalized approach by the PM. Three masters trained research support staff members used general inductive and descriptive content analysis to coalesce the data into themes. Interview transcripts were read repeatedly as a whole and then word by word, allowing categories to flow from the data.Citation22 This analysis resulted in a codebook and summary of the discussed themes.

Results

Across the state, 19 of the 67 counties were included in the PACMAT catchment area; each of these 19 counties include at least one PACMAT spoke site () where a total of 9,918 patients were treated with MOUD at 112 clinical treatment spokes. This total number of patients treated was not a current snapshot of active patients, but the cumulative patients treated since inception of the PACMAT grant in 2017. The range of the average number of patients treated per provider within PACMAT spanned 9–99. Half of all PACMAT program recipients were affiliated with a medical school and teaching hospital. Twenty-five percent had multiple hubs in their networks that served over 2000 unique patients in their respective catchment areas. Only one program employed methadone maintenance as part of an opioid treatment program as its hub. Most programs (7 of 8) did not have uniform EHRs for reporting data from community health center spokes (). All 8 PACMATS were represented during CHS ECHO sessions. To keep discussion on track and engaging, we asked that 1 program administrator or lead physician with an understanding of how their PACMAT operates to participate in ECHO sessions.

Chs ECHO impact

During key informant interviews, PACMAT leads were asked about the impact of the CHS ECHO in five areas: (1) confidence with initiating changes to their PACMATs, (2) addressing challenges, (3) knowledge of best practices, new strategies, or resources, (4) motivation to address the opioid crisis through PACMAT work, (5) collaboration with a variety of stakeholders, and (6) ability to contact other PACMAT colleagues outside of regular meetings.

Confidence

PACMAT leads described many benefits to CHS ECHO participation. While each PACMAT had different organizational approaches and faced unique challenges, discussions during CHS ECHO sessions provided an unparalleled opportunity for reflective learning, new idea generation, and resource sharing. In contrast to other meetings that focus on reporting progress, CHS ECHO sessions created an equal environment for fellow grant recipients to engage in constructive and vulnerable dialogue. Reassurance and empowerment from colleagues with diverse roles facing similar challenges across the state helped address professional isolation, while generating increased motivation and confidence ().

Table 2. CHS ECHO impact on motivation, knowledge, and confidence.

Addressing challenges

The three most common challenges identified by key informants included: (1) recruitment of and support for MOUD waivered providers, (2) billing and sustainability plans for the post-grant period, and (3) data management. Overall, PACMAT leads confirmed continued difficulty addressing provider recruitment and stigmatization of MOUD. PACMATs shared updates on their continuous efforts to address provider related challenges including hiring additional social workers, case managers, and peer recovery specialists. They also reported use of supplemental telemedicine behavioral support to encourage continued patient engagement with recovery services and to deliver additional referral support to spoke providers facing professional isolation.

While many different strategies for billing and sustainability plans were shared, all PACMATs described ongoing challenges with organizing billable medical and behavioral services for PA Medicaid patients. Additionally, PACMAT leads anticipated challenges with developing financially sustainable business models, funding expansions of their addiction medicine service lines, and coping with the accelerating speed of addiction medicine service line developments. During CHS ECHO sessions, PACMAT leads shared strategies for developing value-based payment model updates and implementing Medicaid billable services.

Finally, each PACMAT lead also described their data collection, reporting, and management practices. One common challenge was the need for immediate development of quality data-metric collection and reporting logistics, as addiction medicine service lines expanded quickly among hubs and spokes that employed nonuniform EHRs. Since PACMAT leads represented different points of care (e.g., linkage versus direct care), some also mentioned the difficulty of maintaining patient contact for the completion of reassessment data if their organization was not the frontline patient contact. All PACMAT leads identified a need for additional support at spokes for streamlined data collection and reporting. In addition to facing many structural and systems-level challenges as described above, PACMAT leads negotiated professional challenges with confidence, knowledge, motivation, and professional isolation.

Best practices and increasing knowledge

PACMAT leads had diverse experiences and credentials as health administrators and clinicians. Through these regular constructive and open discussions with a variety of professionals, PACMAT leads developed a greater ability to articulate their local needs, identify what others have been doing, and envision collaborative efforts to address the opioid crisis. During ECHO sessions, each PACMAT presented their unique strengths. These included access to care management services, proximity to the resources of academic medical centers, and access to teams of multidisciplinary professionals across the spectrum of care. Several PACMAT leads stated that their teams were motivated to implement changes and were highly knowledgeable about MAT best practices. One health system that utilized a uniform EHR across its spokes was able to leverage their funding to develop streamlined data collection methods for MAT quality and outcomes reporting. Additionally, many PACMATs had efficient coordination with spokes that represent a range of services, such as primary care, pregnancy-related care, community recovery centers, criminal justice systems, and EDs. Several PACMATs successfully increased access to harm reduction-based options at their spokes and alleviated patient burden through the development of direct contracts with area payers to secure patient housing, transportation, and food.

Addressing the opioid crisis

CHS ECHO discussions highlighted two important themes for future opioid crisis efforts: (1) the need for strategic and proactive program reevaluation as addiction medicine services lines quickly expand and (2) the sustainability of collaborative peer learning networks as grant funding changes (). All PACMAT leads shared collective challenges with maintaining an overall design strategy as opioid crisis efforts need to be rolled out rapidly. The speed of program development and expansion often required incremental system fixes, during which new challenges arose. Major topics of collaboration in this area included the need for adequate provision of provider support, system capacity building of expanding MOUD programs, incorporation of MOUD data within EHR systems, and payment models that provided more complete reimbursement of billings and claims for MOUD and behavioral health related services.

Table 3. CHS ECHO themes for future collaborative opioid crisis efforts.

Sustaining peer learning networks

Key informant interviews included important conversations about sustainable collaborative peer learning networks. While every systems-based presentation described each PACMAT’s sustainability plan for their MOUD services, the format of CHS ECHO also provided a platform for continued peer reflective learning that is sustainable beyond the duration of PACMAT funding. Although most PACMAT leads expressed that CHS ECHO should not be a total replacement for all in-person interactions, they noted that the ECHO format cut down on hours of driving time and allowed more staff at their organizations to attend calls. Additionally, the open information sharing during CHS ECHO generated collaborative connections and opportunities with external partners outside of in-person quarterly meetings with the state or CHS ECHO sessions. With this more convenient and sustainable format, PACMAT leads indicated the valuable utility of CHS ECHO as a structured opportunity for continued constructive dialogue about challenges, which generates new ideas and solutions ().

Table 4. CHS ECHO impact on collaboration.

Discussion

CHS ECHO created a collaborative peer learning network among PACMAT leads with productive bidirectional learning and support. Using Project ECHO principles and technology, PACMAT leads were able to meet every other week to network, discuss respective programs, share strategies, validate common challenges and foster collaborative brainstorming on a more frequent, convenient, and less costly basis. Through systems-level case presentations and open virtual discussions, we were able to identify common opportunities for collaborative opioid crisis response efforts. Prior to the CHS ECHO, PACMAT leads communicated through monthly phone calls and in-person quarterly meetings with state personnel primarily to share updates. Although not a replacement for in-person meetings, CHS ECHO provided an opportunity for more candid dialogues compared to in-person quarterly meetings with the state.

A key pillar of Project ECHO is a level playing field. This environment and regular communication jumpstarted collaborations between external partners, who would otherwise see each other as competing health systems. PACMAT leads also represented different perspectives in health care, which helped PACMAT leads better understand and anticipate diverse challenges in addiction medicine service line expansion. As all PACMATs managed the quick development and expansion of their programs, this proactive health systems evaluation and improvement was especially important. The close-knit and collaborative network that emerged from CHS ECHO participation highlighted the need for democratized knowledge platforms where those involved in opioid crisis efforts could learn from and support each other’s work for a greater collective impact. As demonstrated by the interview data, PACMAT leads reported an increased sense of professional support and motivation, not unlike the improvements in provider sense of isolation seen in individual focused ECHO programs.Citation23–26

PACMAT leads shared common challenges experienced by addiction medicine service lines nationwide.Citation27–29 In particular, recruitment and support of MOUD waivered providers remained difficult due to stigmatization of OUD and its pharmacologic treatments; provider burden and burnout; and logistical challenges with medical and behavioral health reimbursements.Citation11,Citation12,Citation30–32 Furthermore, most PACMAT hub and spokes did not use uniform EHRs which prevented expedient data sharing, collection, and reporting. Many spokes were community health centers that provided critical safety net treatment in underserved areas, but they had limited ability to report quality and outcomes metrics. However, streamlined MAT data collection was achieved by one health system with a uniform EHR through intensive software development. Robust data collection is crucial for assessing access and quality of patient services, but innovative software development to patch the lack of existing data in EHRs and to develop data sharing capabilities is expensive. Many health systems instead prioritized increasing access to care, community partnership development, or other areas of need. Although each PACMAT has implemented successful strategies the study findings reinforce the message that systems and providers may benefit from additional funding, policy, and logistical support to overcome these barriers.

As indicated above, PACMAT systems were based on VT and RI’s Hub-and-Spoke model of care for addiction. However, several differences between these states presented unique challenges for PA. PA is geographically larger and demographically diverse, leading to variety in program structure and implementation strategy. Requests for new government-positions, like VT’s support staff, may have required inexpedient legislative input during a crisis. Needing urgent opioid crisis strategies with a lower barrier of entry, PA mandated a sustainability provision, requiring that programs coordinate with managed care organizations, PA Medicaid or outside donors to continue services after the grant period ended. Additionally, only one program offered methadone treatment at its hub. Given the extensive requirements for licensure, requiring methadone for hub and spoke networks would likely delay urgently needed patient care. The geographic, funding, and policy considerations of PA are likely to be reflected in other states who create similar statewide hub and spoke systems to address the opioid crisis. Given the urgency of opioid crisis efforts, future hub and spokes will likely continue to be highly heterogeneous as health systems work to cover treatment gaps in diverse areas.

Study strengths and limitations

The PACMAT collaboration to address the opioid crisis is unique. Previously, health systems would infrequently collaborate and largely viewed each other as business rivals, instead of as health care collaborators. With the creation of PACMAT, and the addition of a Project ECHO format, CHS ECHO provided valuable quantitative data on the treatment capacity and number of patients treated, and qualitative feedback regarding how different hospital systems could work together. This work has the potential to enhance reduction of overdose deaths throughout the state by improving access to MOUD. However, due to proprietary data within different health care systems, all data presented was by report and could not be independently verified. In addition, interviews could not be conducted anonymously, and social desirability bias may have impacted feedback on the CHS ECHO sessions. Further studies with independent data verification and anonymous feedback reporting will be needed.

Conclusion

The heterogeneity of the PA Hub and Spoke systems will likely be reflected in other states and future hub and spoke models. As these systems are created, the challenges shared by PACMAT leads demonstrate qualitative evidence that additional and proactive supports may be needed to address waivered provider recruitment and support, outcomes data collection and reporting infrastructure, and financial sustainability. As collaborative opioid crisis efforts develop, a platform for open conversations such as Project ECHO can expedite creative solutions and provide professional support. Project ECHO provided a platform for the continued health systems’ collaboration when funding sources shift.

The relationships between health systems fostered through PACMAT funding and CHS ECHO will facilitate effective coordination for common challenges, such as payment sustainability and data reporting that may require coordinated advocacy at the state level. The work of the PACMAT awardees have revealed several next steps. Specifically, qualitative evidence suggests a need for more uniform data reporting, fewer regulatory and policy restrictions to deliver all forms of MOUD in high-need areas, and training and support for the next generation of MOUD opioid prescribers integrated within diverse treatment settings. The insights that emerged from PACMAT collaboration and CHS ECHO participation have highlighted opportunities in our health system that will lead to better patient care and reduction of overdose mortality in PA.

Author contributions

JK, EF, and SK conceived of the Collaborative Health Systems (CHS) ECHO program. EF, GH, KB, and JK contributed to the operation of the CHS ECHO program. GH, EF, and SK took the lead in writing this manuscript. All authors, KB, SH, JK, PV, AL, JB, MC, LT, MF, JM, GS, and RL, provided critical feedback and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Kawasaki_et_al_CHS_Supplement_08.10.21.docx

Download MS Word (13.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug Overdose Deaths – 2019. [Webpage]. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html/. Accessed August 8, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug Overdose Death Data – 2016 [Webpage]. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html/. Accessed February 16, 2017.

- Pennsylvania Department of Health. Results from the Fatal and Non-Fatal Drug Overdoses in Pennyslvania – 2019. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Department of Health; 2019.

- Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies-tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063–2066.

- Lee JD, Friedmann PD, Kinlock TW, et al. Extended-release naltrexone to prevent opioid relapse in criminal justice offenders. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1232–1242.

- Schwartz RP, Gryczynski J, O’Grady KE, et al. Opioid agonist treatments and heroin overdose deaths in Baltimore, Maryland, 1995–2009. Am J Public Health. 2013; 103(5):917–922.

- Grönbladh L, Öhlund LS, Gunne LM. Mortality in heroin addiction: impact of methadone treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;82(3):223–227.

- Newman R, Whitehill W. Double-blind comparison of methadone and placebo maintenace treatments of narcotic addicts in Hong Kong. The Lancet. 1979;314(8141):485–488.

- Rieckmann T, Muench J, McBurnie MA, et al. Medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders within a national community health center research network. Subst Abus. 2016;37(4):625–634.

- Stoller KB, Stephens MAC, Schorr A. Integrated service delivery models for opioid treatment programs in an era of increasing opioid addiction, Health Reform, and Parity. 2016. http://www.aatod.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/2nd-Whitepaper-.pdf/.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services, Office of the Surgeon G. Reports of the surgeon general. In: Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016.

- Shields AE, Shin P, Leu MG, et al. Adoption of health information technology in community health centers: results of a national survey. Health Aff. 2007;26(5):1373–1383.

- Brooklyn JR, Sigmon SC. Vermont hub-and-spoke model of care for opioid use disorder: development, implementation, and impact. J Addict Med. 2017;11(4):286–292.

- Casper KL, Folland A. Models of Integrated Patient Care Through OTPs and DATA 2000; Practices. American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence, 2016. http://www.njamha.org/links/publicpolicy/AATOD_whitepaper1.pdf.

- Anderson JB, Martin SA, Gadomski A, et al. Project ECHO and primary care buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder: implementation and clinical outcomes. Subst Abus. 2021;2021:1–9.

- Komaromy M, Duhigg D, Metcalf A, et al. Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes): a new model for educating primary care providers about treatment of substance use disorders. Subst Abus. 2016;37(1):20–24.

- Puckett HM, Bossaller JS, Sheets LR. The impact of Project ECHO on physician preparedness to treat opioid use disorder: a systematic review. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2021;16(1):6.

- Holmes CM, Keyser-Marcus L, Dave B, Mishra V. Project ECHO and opiod education: a systematic review. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2020;7(1):9–22.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. T1-170-017 Individual Grant Awards, 2017. https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/awards/2017/TI-17-017.

- Arora S, Thornton K, Komaromy M, Kalishman S, Katzman J, Duhigg D. Demonopolizing medical knowledge. Acad Med. 2014;89(1):30–32.

- Kawasaki S, Francis E, Mills S, Buchberger G, Hogentogler R, Kraschnewski J. Multi-model implementation of evidence-based care in the treatment of opioid use disorder in Pennsylvania. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;106:58–64.

- Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405.

- Agley J, Delong J, Janota A, Carson A, Roberts J, Maupome G. Reflections on Project ECHO: qualitative findings from five different ECHO programs. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1936435.

- Carlin L, Zhao J, Dubin R, Taenzer P, Sidrak H, Furlan A. Project ECHO telementoring intervention for managing chronic pain in Primary Care: insights from a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2018;19(6):1140–1146.

- Ball S, Stryczek K, Stevenson L. A qualitative evaluation of the pain management VA-ECHO program using the RE-AIM framework: the participant’s perspective. Front Public Health. 2020;15(8):169.

- Shea CM, Gertner AK, Green SL. Barriers and perceived usefulness of an ECHO intervention for office-based buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder in North Carolina: a qualitative study . Subst Abus. 2021;42(1):54–56.

- Jacobson N, Horst J, Wilcox-Warren L, et al. Organizational facilitators and barriers to medication for opioid use disorder capacity expansion and use. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2020;47(4):439–448.

- Cernasev A, Hohmeier KC, Frederick K, Jasmini H, Gatwood J. A systematic literature review of patient perspectives of barriers and facilitators to access, adherence, stigma, and persistance to treatment for substance use disorder. Exploratory Research in Clinical and Social Pharmacy. 2021;2:100029.

- Williams AR, Nunes EV, Bisaga A, Levin FR, Olfson M. Development of a cascade of care for responding to the opioid epidemic. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45(1):1–10.

- Jones CW, Christman Z, Smith CM, et al. Comparison between buprenorphine proivder availability and opioid deaths among US counties. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;93:1–25.

- Jones EB, Staab EM, Wan W, et al. Addiction treatment capacity in health centers: the role of Medicaid Reimbursement and Targeted Grant Funding. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(7):684–690.

- Huhn AS, Dunn KE. Why aren’t physicians prescribing more buprenorphine? J Sust Abuse Treat. 2017;78:1–7.