Abstract

Background: Smartphone-based interventions are increasingly being used to facilitate positive behavior change, including reducing alcohol consumption. However, less is known about the effects of notifications to support this change, including intervention engagement and adherence. The aim of this review was to assess the role of notifications in smartphone-based interventions designed to support, manage, or reduce alcohol consumption. Methods: Five electronic databases were searched to identify studies meeting inclusion criteria: (1) studies using a smartphone-based alcohol intervention, (2) the intervention used notifications, and (3) published between 1st January 2007 and 30th April 2021 in English. PROSPERO was searched to identify any completed, ongoing, or planned systematic reviews and meta-analyses of relevance. The reference lists of all included studies were searched. Results: Overall, 14 papers were identified, reporting on 10 different interventions. The strength of the evidence regarding the role and utility of notifications in changing behavior toward alcohol of the reviewed interventions was inconclusive. Only one study drew distinct conclusions about the relationships between notifications and app engagement, and notifications and behavior change. Conclusions: Although there are many smartphone-based interventions to support alcohol reduction, this review highlights a lack of evidence to support the use of notifications (such as push notifications, alerts, prompts, and nudges) used within smartphone interventions for alcohol management aiming to promote positive behavior change. Included studies were limited due to small sample sizes and insufficient follow-up. Evidence for the benefits of smartphone-based alcohol interventions remains promising, but the efficacy of using notifications, especially personalized notifications, within these interventions remain unproven.

Introduction

Alcohol misuse contributes to approximately three million deaths worldwide each year and is one of the leading causes of preventable mortality worldwide.Citation1 Alcohol misuse is defined as drinking in a way which is harmful, hazardous, or being dependent on alcohol.Citation2 In the UK, recommended drinking guidelines are to consume no more than 14 UK units (10 ml or 8 g of pure alcohol per unit) of alcohol per week.Citation2,Citation3 The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey in England 2014 reported around 1 in 5 (19.7%) adults drinking at hazardous, harmful or dependent levels, as defined by the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT-10).Citation4,Citation5 Most of these were hazardous drinkers (16.6%), as indicated by a score of 8–15 on the AUDIT-10.Citation5

Regularly consuming high levels of alcohol has a significant effect on psychological and physical health. Several effective intervention techniques are available to support, manage or reduce alcohol consumption, including brief interventions, specialist treatments, and less intensive treatments that combine the two.Citation6 For the UK general population, brief interventions are the most commonly used intervention technique,Citation7 often provided to individuals scoring 8–15 on the AUDIT-10. Brief alcohol interventions (BAIs) involve an assessment of risk, and provide feedback, advice, and support on reducing alcohol consumption. BAIs can be delivered face-to-face in primary care settings but can also be delivered digitally. They aim to help recognize risky drinking and to promote positive changes in behavior. For example, by reducing alcohol consumption to recommended low-risk levels, reducing harmful actions like binge drinking, and developing coping strategies to control and reduce drinking.Citation6–8

Although there are effective alcohol interventions available, there are several barriers which impact on treatment delivery, including a perceived stigma around seeking support, and problems relating to the accessibility and availability of treatment services.Citation9,Citation10 Over the last two decades digital technologies, including smartphone-based interventions, have been developed to target mental health more generally.Citation11–13

There has also been a strong growth in the number of digital interventions available to support, manage or reduce alcohol consumption in the general population.Citation14–16 The mode of delivery for digital alcohol interventions has, in the last five years, shifted to smartphone-based interventions, including Drink LessCitation15 and DrinkawareCitation17 which aim to reduce alcohol consumption and are recommended for use by the UK National Health Service (NHS). For the purposes of this review, a smartphone-based alcohol intervention was an intervention delivered via a smartphone which aimed to support the management or reduction of alcohol consumption. These have several potential advantages over face-to-face methods as they help overcome some of the barriers for treatment delivery, including being more cost-effective and accessible. Increasing the sense of anonymity might reduce the perceived stigma associated with face-to-face help for problematic alcohol use.Citation18 Smartphone-based interventions allow for the more rapid advancement and development of alcohol treatment options, at a speed which cannot be matched by traditional methods. Some evidence suggests that digital interventions may reduce alcohol consumption, with an average reduction of up to three UK standard drink units (approximately 23 g of pure alcohol) per week compared to a control group.Citation16,Citation19

Smartphone-based interventions often utilize notifications to help increase user engagement. There is growing evidence that short message service (SMS) text message based interventions can help individuals modify health behaviors.Citation20,Citation21 However, other notification types are becoming increasingly popular, potentially because users may be more accepting of notifications as they can better control notification settings. Notifications (e.g., push notifications, alerts, nudges or prompts) have displayed effectiveness at maintaining app engagement.Citation22 A push notification is an automated message sent by an application which pops up on the user’s phone to gain their attention.

Various authors have suggested that future mobile health apps should implement regular push notifications to encourage active engagement by users.Citation23,Citation24 Personalized notifications are another form of notification being implemented in smartphone-based alcohol interventions. For the purposes of this review, personalized notifications were considered to be any form of notification (i.e., push notification, alert, prompt or nudge) tailored specifically to that user. For instance, personalized notifications to use the drinks diary, to suggest alternative behaviors, and to provide feedback on goal progress.

Although it has been suggested that notifications help to improve engagement, literature on the use of notifications in smartphone-based interventions aiming to reduce alcohol consumption remains very limited. There is some literature exploring the effectiveness of using text messages in healthcare apps more generally,Citation25,Citation26 however, there is a lack of research in relation to the role of notifications within smartphone-based alcohol interventions.

In this review, we advanced on previous literature by focusing on the role of notifications (excluding SMS text messaging) on changing behaviors toward alcohol. The primary aim of this review was to explore the use of notifications in smartphone-based interventions designed to support, manage, or reduce alcohol consumption, and to describe development approaches used to inform future intervention development. The secondary aims were to explore the protocols in which notifications are used, including time and frequency, and to consider how personalized notifications impact on alcohol reduction.

Method

Design

This systematic review was conducted following Cochrane methodology and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.Citation27 The review was registered with PROSPERO in August 2020 (CRD42020190425).

Search strategy

Literature was found by searching five electronic databases: PubMed (including MEDLINE and PubMed Central), Web of Science, Embase, Global Health and PsychINFO. The databases were searched in April 2021 using a combination of pre-defined terms which related to alcohol (i.e., alcoh*), mobile applications (i.e., mobile, mHealth, m-health, electronic health, ehealth, app*, smartphone, android, iOS, Apple, iPhone) and notifications (i.e., push* notifi*, messag*) using the Boolean operator “AND”. The asterisk denotes truncation. Restrictions were placed on publication dates from January 2007 to April 2021 to allow for coverage of the advent of the first modern day smartphone. Searches were restricted to English language. Reference lists from all included studies were scanned for additional literature and PROSPERO was searched to identify completed, ongoing or planned systematic reviews and meta-analyses of relevance.

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility was determined using additional inclusion criteria:

The paper included a smartphone-based alcohol intervention.

The intervention used notifications.

Searches were not restricted by age group, population, or occupation. As smartphone interventions are delivered through mobile devices, there was no restriction as to the location where the participant could interact with the intervention. Systematic reviews, gray literature and conference abstracts were excluded from the search. As this review sought to systematically evaluate a range of study designs, any comparators or controls were reported.

Study selection and data extraction

After the initial search, all identified studies were screened for duplicates which were removed, using Endnote X9. Two members of the review team (CW and KW) independently reviewed the remaining titles, followed by abstracts. The full research papers for studies identified as potentially relevant were reviewed. The reviewers (CW and KW) independently decided which studies met the eligibility criteria to be included in the review. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (DL).

Data were extracted independently by CW on study characteristics (country, aim, design, methods, measures used), participant characteristics (sample size, response rates, age range, sex, population/occupation), details of intervention (description, mode of delivery, duration, comparators/controls), notifications (frequency, personalization, mode of delivery, content) and study findings (outcomes, conclusions, limitations). KW independently performed second reviewer data extraction on a sample of studies. Due to the small number of included studies, findings were summarized in a narrative synthesis.

Quality assessment of included studies

The quality of each included study was assessed independently by two reviewers (CW and DL) using an adapted version of the Newcastle-Ottowa Scale (NOS).Citation28 The assessment judged each study on three broad perspectives; (1) the selection of study groups, (2) the reporting on the use of notifications, app engagement or usage, and (3) the appropriateness of the follow-up period. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Results

Overview of search results

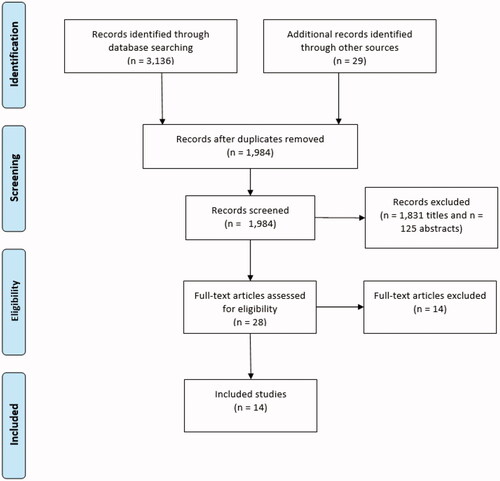

The database search identified 3,165 articles, of which 1,181 were duplicates which were removed. In total, 1,984 titles and 153 abstracts were screened, identifying 28 for full text screening. Of these, 14 were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria. PRISMA flow diagram can be found in . Interrater reliability was calculated at each screening stage. At the title screening stage, interrater reliability was strong at Cohen’s kappa (κ) 0.88 (94.47% agreement).

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 14 publications, describing 10 interventions, were identified as eligible for inclusion in the review. The earliest study was published in 2012, with most studies published between 2017 and 2021. Six papers (43%) were based on US data,Citation29–34 five (36%) on UK dataCitation17,Citation35–38 and three (21%) on Australian data.Citation39–41 Gustafson and colleagues,Citation30 and McTavish and colleaguesCitation31 reported on the same dataset, as did both papers by Poulton and colleagues,Citation39,Citation40 but each were included as they reported different outcome measures of interest to the review.

In accordance with the inclusion criteria, all interventions were delivered via smartphone. The interventions used were Drinkaware,Citation17 LBMI-A,Citation29,Citation33 Drink Less,Citation37,Citation38 A-CHESS,Citation30,Citation31 BRANCH,Citation35 CASA-CHESS,Citation32 CNLab-A,Citation39,Citation40 AlcoRisk,Citation41 Step Away,Citation34 and one un-named app developed for research.Citation36

Of the 14 included papers, twoCitation30,Citation31 (reporting on one intervention, A-CHESS) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and the remainder were non-randomized studies, where available comparator/control groups were reported. Of the non-randomized studies, four involved qualitative interviewing to collect at least some of the data.Citation17,Citation35,Citation37,Citation41 Measures of alcohol consumption varied across studies, including AUDIT-C,Citation34 AUDIT-10Citation36–40 and clinician applied Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria.Citation30,Citation31 Not all studies reported on the duration of the study and, or, intervention.Citation36,Citation37 Across those that did, the majority measured short-term outcomes (less than three months), one measured medium-term outcomes (three to six months) and five measured long-term outcomes (six months or longer). The shortest was a two-week feasibility trialCitation41 and the longest length of follow-up was 12 months.Citation30,Citation31

A variety of different outcome measures were used to assess changes in alcohol consumption. Two studies reported their main outcome measures related to a reduction in alcohol consumption as measured by number of units or drinks.Citation17,Citation33 Two studies monitored drinking behaviors post-discharge from residential treatment for alcohol use disorder.Citation30,Citation31 Three studies explored prospective vs retrospective reporting of alcohol behaviors.Citation29,Citation36,Citation39 Three reported on app development.Citation37,Citation40,Citation41 Three reported on app usage and engagementCitation32,Citation35,Citation38 and how it related to changes in alcohol consumption. The final study’s main outcome related to the usability of the app, however, they also reported on change in alcohol consumption.Citation34 In accordance with the inclusion criteria, all interventions used notifications to some degree. Full details are listed in and Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

Notifications

Populations studied

Approximately half of the studies reported a sample size of fewer than 100 participants. The smallest sample size was 19 participants.Citation41 The largest sample, reported by Attwood and colleagues in the quantitative part of their study, was over 100,000 participants.Citation17 All studies used mixed-gender samples, however, these were not always evenly distributed. In total, six of included studies were conducted using samples from the general population,Citation17,Citation36–41 seven used clinical populationsCitation29–34 for example participants that met DSM-5 criteria for alcohol use disorder, and one study did not report on the population type.Citation35

Development

None of the included studies specifically reported on how the notifications used in the interventions were developed. Only three studies focused on app development.Citation37,Citation40,Citation41 Poulton and colleagues concluded that the development of CNLab-A followed an appropriate methodology for measuring alcohol consumption over time.Citation40 Smith and colleagues feasibility trial supported the efficacy of the AlcoRisk app’s software development process and offered an evidence-based approach to integrating relevant behavioral and technical areas.Citation41 Both studies used an iterative development process with three stages: (1) requirements analysis, (2) feature and interface design, and (3) app implementation. Garnett and colleagues systematically developed the Drink Less app based on scientific literature and theory.Citation37 Their approach involved two phases: (1) selection of intervention components, and (2) design and translation into app. Given the small number of included studies that report on the development process, it is difficult to draw conclusions that may help to inform future development of smartphone-based alcohol interventions.

Of the studies that reported on intervention development, none explicitly reported using co-production. Co-production involves the active participation of relevant stakeholders during pre-development and development. It is important that end-users are involved in the development process to get a representation of how the app may be used in practice, and the relevance and importance of particular outcomes for service users.Citation42,Citation43 The three studies that reported on development did use a small group for usability testing.Citation37,Citation40,Citation41 It remains unclear whether these testing groups led to improvements in engagement. Drinkaware,Citation17 CNLab-ACitation39,Citation40 and AlcoRiskCitation41 were developed for use on both iOS and Android systems, including. Others were available on only Android devices including CASA-CHESS,Citation32 or only iOS devices including Step AwayCitation34 and Drink Less.Citation37,Citation38

Implementation

The most common mode of delivery of notifications reported in the included studies were reminders, prompts or alerts to log drinking behaviors.Citation29,Citation34–41 For instance, as set by the app developers, Drink Less users were sent daily push notifications at 11am asking to, “Please complete your drink diaries”, to encourage self-monitoring of drinking behavior.Citation38 Another common notification type was GPS initiated-alerts which were activated when in a “high-risk” drinking location as specified by the user.Citation17,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33 For example, the Drinkaware app sent alerts to users stating, “You are near one of your designated weak spots. Remember, drinking less has many feel-good benefits”.Citation17

Notification frequency varied, some studies limited the number that could be sent, for example, the CNLab-A app sent a maximum of 42 notifications across the 21-day intervention, asking users to record drinking information.Citation39,Citation40 However, not all interventions worked this way. Some interventions sent notifications any time GPS located the user in a “weak spot” or “high-risk” location (e.g., A-CHESSCitation30,Citation31) Only one study, reporting on the Drink Less app, discussed participant engagement with notifications by reporting on log-in sessions and frequency of log-in session, drinking diary entry, and disengagement rates.Citation38

Only two of the included studies reported on the use of personalization. BRANCH app users received tailored notifications, personalized feedback, and tailored information.Citation35 This included in-app reminders based on goals, motivational messaging (including positive reinforcement and praise), and tailored feedback and information based on their motivations to reduce drinking. Additionally, users of Step Away, could personalize the app through reminders including high-risk times as specified by the user, reasons for change and scheduled activities.Citation34 However, it is unclear if this included personalized notifications. All other included studies either did not useCitation41 or did not report onCitation17,Citation29–33,Citation36–40 the use of personalized notifications. The AlcoRisk app was reported as having low utility because it did not include personalized feedback relating to alcohol consumption.Citation41

User response and engagement

Some studies drew conclusions regarding notification impact. Drinkaware users highlighted in interviews a need for personalization and tailoring of content to promote long-term app engagement.Citation17 LMBI-A users reported that receiving notifications in a high-risk location was a potentially useful feature of the app, however, it was not considered to be useful in the study because location accuracy was unreliable.Citation33

Only one study reported on the relationship between notifications and engagement. Bell and colleagues reported a strong association between the delivery of a notification and the user opening the Drink Less app within the following hour.Citation38 During the first month following download, the likelihood of using the app within an hour of receiving a notification was around four times higher than the probability of using the app the hour before the notification was sent.Citation38 Bell and colleagues do not report the number of users who cleared the notification without using the app, only that this action was not recorded as use. Therefore, the proportion of users who did not want to engage with notifications remains unknown.

Outcome

Some studies reported on behavior change outcomes. For instance, Gustafson and colleagues concluded that the intervention group who received treatment as usual (TAU) plus A-CHESS reported a lower number of drinking days and a higher likelihood of continued abstinence, when compared to the control group who received TAU only.Citation30 Additionally, Dulin and colleagues pilot study reported significant reductions in the number of days of hazardous alcohol use while using LBMI-A; 56% of days at baseline vs 25% of days while using the app.Citation33 However, only one study reported on the use of notifications and how they influenced behavior change. Bell and colleagues reported that notifications encouraged users to record drink-free days more than drinks consumed, and that the median time per session reduced for the rest of the day following a notification.Citation38 None of the other included studies reported on the role of notifications in changing behavior toward alcohol.

Quality assessment

The overall mean NOS score was 5/8, and only two studies met less than half of the assessed quality criteria. Due to study design, some of the quality assessment measures were not applicable to all studies and therefore led to an unclear assessment of quality. The quality assessment for each study is summarized in .

Table 2. Quality assessment scores.

Discussion

The role of notifications in changing behavior toward alcohol of the reviewed interventions was inconclusive. Many of the included studies did not report on the specifics of notifications, such as content, development, triggers, and personalization. Overall, there is a lack of literature exploring the role of notifications used in smartphone-based interventions which aim to change behaviors toward alcohol. This review found tentative evidence regarding the benefits of using notifications in smartphone-based interventions for alcohol misuse.

The most common mode of delivery of notifications reported in the included studies were reminders, prompts or alerts to log drinking behaviors.Citation29,Citation34–41 Previous literature highlights the promotion of self-monitoring of behavior in brief interventions, within smartphone-based alcohol interventions for example, is associated with improved outcomes.Citation44 Self-monitoring allows the user to monitor and record their behavior. In an alcohol intervention, this includes recording consumption in a drink’s diary. However, smartphone-based alcohol interventions often have a high rate of attrition and struggle to maintain engagement.Citation45 For example, on up to 95% of apps, the majority of users disengage after one month.Citation46

In this review, only one study drew distinct conclusions about the use of notifications and engagement, and the relationship between notifications and behavior change.Citation38 Previous literature highlights that notifications are one of the most useful features of smartphone-based alcohol interventions.Citation47,Citation48 For example, one qualitative analysis revealed that participants ranked personalized features, including notifications, the most highly for promoting app engagement.Citation49

The other 13 (of 14) studies did not draw distinct conclusions regarding notifications, with authors failing to report why they did not assess the impact of notifications on the outcome. One possible explanation is that permission is required to send notifications to users. This is a potential barrier as none of the studies reported on how many users gave permission for notifications. Further, the primary aims of many studies focused on the impacts of the app as a whole and not specifically on the additional impact of notifications, particularly because this is a relatively novel field of research. Future research should take the above into account and consider reporting on different elements of smartphone-based interventions that may be used to promote engagement, including personalized notifications. Future research should seek to isolate each intervention component to determine which features bring about behavior change.

In this review, several studies used a GPS location tool to notify the user when in a high-risk drinking location, but this was not reported as useful by participants.Citation17,Citation33 In some instances participants recognized the potential usefulness of receiving alerts but felt that the GPS system was unreliable due to poor location accuracy.Citation33 In another study, the concept of notifying an individual of a physical environment trigger was also not viewed as useful and was poorly understood by participants.Citation17 This aligns with previous literature including one study that found lower user ratings for smartphone-based alcohol reduction apps using these types of features.Citation50

It is important to consider that although smartphone-based interventions are a useful way to deliver interventions, there can be potential negative consequences, including stress associated with technical difficulties. Although, as none of the included studies reported any negative consequences, it is not clear whether they were not present or just not reported. Additionally, digital technology is advancing at a faster pace than interventions are typically developed.Citation51 Therefore, some interventions risk becoming obsolete before the end of the development process.

Due to the aims of the review, our search criteria were narrow leading to a small number of relevant papers being included in the review. A broader review with wider search criteria may have included a larger number of relevant papers, such as that by Blonigen and colleagues,Citation52 and Giroux and colleagues.Citation53

Limitations

This review provides a systematic, up-to-date overview of the current evidence around smartphone-based alcohol interventions which use notifications. We summarize the available evidence by focusing on interventions described in published, peer-reviewed papers. However, as outlined, the included studies had some limitations which impacted on the quality of the review. There were concerns about the duration of interventions, inadequate follow-up periods and the use of self-report measures. This review identified 14 published, peer-reviewed studies, reporting on 10 interventions which used notifications, therefore when interpreting the results, it is important to take this low number into consideration. Further, the literature lacks RCTs assessing the role of notifications in managing alcohol misuse. Potentially this could be explained by the novelty of this research field. Additionally, to gather as much available evidence as possible, the included studies vary as to whether the study was carried out in a general population or clinical sample, and what sort of comparator/control groups were used, if any. These variations limit the ability to make comparisons between studies.

Implications

We would recommend that future research should seek to more thoroughly explore the role of notifications in smartphone-based interventions aiming to support, manage or reduce alcohol consumption. This should include exploring whether notifications can be used to improve engagement and adherence to digital interventions and remote measurement technology. New research should seek to report on the relationship between the use of notifications in smartphone-based alcohol interventions and behavior change related to alcohol consumption. Using notifications in smartphone-based alcohol interventions should report the protocols used for implementing notifications, the engagement rates with notifications, and the acceptability of using notifications (for instance how many users provided permission for notifications and how many notifications failed to send). Research should highlight whether notifications are generic or personalized, if they were clinician activated or automated, and should report on notification development.

Due to the narrow aims of the review, we focused on notifications as an isolated component of smartphone-based alcohol interventions. Future research should consider assessing whether notifications are an integral part of the intervention that influence the reported outcomes of the app as a whole. It is important to identify the effective components of smartphone-based alcohol interventions and which combination of components is optimal. This will help inform the future development of smartphone-based alcohol interventions. New research should consider using a factorial design to explicitly evaluate the role of notifications. The development of an effective alcohol intervention would have important implications for public health.

Additionally, this review finds some evidence regarding the benefits of using smartphone-based interventions for alcohol misuse. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recognize that the evidence base is growing but currently remains limited. The NICE guidelines recommend mobile health interventions for alcohol misuse as an adjunct to existing services. Alongside existing literature,Citation16,Citation18,Citation19,Citation54 this review supports the idea that smartphone-based alcohol interventions may become a feasible, acceptable and useable treatment option. Future research should seek to compare the efficacy of stand-alone smartphone-based alcohol interventions vs using smartphone-based interventions alongside treatment as usual. New studies should use adequately statistically powered samples and an adequate length of follow-up to ensure that results of behavior change are meaningful.

Conclusions

Overall, evidence for the role of notifications in changing behavior toward alcohol of the reviewed interventions was disappointingly inconclusive. While several studies highlighted that smartphone-based alcohol interventions are an important tool for monitoring alcohol consumption and that many incorporate notifications, future research should focus on providing stronger evaluations relating to the role of notifications within smartphone-based interventions for alcohol reduction.

Author contributions

CW and DL proposed and designed the review. CW and KW completed all stages of screening and data extraction. CW and DL completed quality assessments. CW wrote the first draft, and all other authors contributed to each version and approved the final manuscript.

PRISMA_Checklist.docx

Download MS Word (31.7 KB)Disclosure statement

NTF is partly funded by the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defence and a trustee of a charity supporting the wellbeing of the UK Armed Forces community. DL is partly funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Center. DM is a trustee for the Forces in Mind Trust (FIMT: the project funder). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the FiMT or the UK Ministry of Defence.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organisation. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018; 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274603/9789241565639-eng.pdf?ua=1

- NHS. Alcohol Misuse. NHS Online. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alcohol-misuse/. Published 2018. Accessed April 19, 2021.

- UK Government. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Low Risk Drinking Guidelines 2016.; 2016. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545937/UK_CMOs__report.pdf

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):1231–804.

- Drummond C, McBride O, Fear NT, Fuller E. Alcohol dependence – adult psychiatric morbidity survey: Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, England, 2014. NHS Digital. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey-survey-of-mental-health-and-wellbeing-england-2014. Published 2016. Accessed April 20, 2021.

- Heather N, Raistrick D, Godfrey C. A Summary of the Review of the Effectiveness of Treatment for Alcohol Problems; 2006. www.nta.nhs.uk.

- Burton R, Henn C, Lavoie D. The Public Health Burden of Alcohol and the Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Alcohol Control Policies An Evidence Review The Public Health Burden of Alcohol and the Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Alcohol Control Policies: An Evidence Review 2 About Public Health England; 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-public-health-burden-of-alcohol-evidence-review. Accessed October 2, 2020.

- Moyer A, Finney JW. Brief interventions for alcohol misuse. Cmaj. 2015;187(7):502–506.

- Grant BF. Barriers to alcoholism treatment: reasons for not seeking treatment in a general population sample. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58(4):365–371.

- Probst C, Manthey J, Martinez A, Rehm J. Alcohol use disorder severity and reported reasons not to seek treatment: a cross-sectional study in European primary care practices. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2015;10(1):32.

- Wickersham A, Petrides PM, Williamson V, Leightley D. Efficacy of mobile application interventions for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Digit Heal. 2019;5:205520761984298.

- Weisel KK, Fuhrmann LM, Berking M, Baumeister H, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD. Standalone smartphone apps for mental health-a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit Med. 2019;2(1):118.

- Miralles I, Granell C, Díaz-Sanahuja L, et al. Smartphone apps for the treatment of mental disorders: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(4):e14897.

- Donoghue K, Patton R, Phillips T, Deluca P, Drummond C. The effectiveness of electronic screening and brief intervention for reducing levels of alcohol consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(6):e142.

- Garnett C, Crane D, Michie S, West R, Brown J. Evaluating the effectiveness of a smartphone app to reduce excessive alcohol consumption: protocol for a factorial randomised control trial. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):536.

- Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Garnett C, et al. Personalised digital interventions for reducing hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in community-dwelling populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;9(9):CD011479.

- Attwood S, Parke H, Larsen J, Morton KL. Using a mobile health application to reduce alcohol consumption: a mixed-methods evaluation of the drinkaware track & calculate units application. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):394.

- Boumparis N, Schulte MHJ, Riper H. Digital mental health for alcohol and substance use disorders. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2019;6(4):352–366.

- Beyer F, Lynch E, Kaner E. Brief interventions in primary care: an evidence overview of practitioner and digital intervention programmes. Curr Addict Rep. 2018;5(2):265–273.

- Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, Grant Harrington N. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:41–48.

- Bendtsen M, McCambridge J, Åsberg K, Bendtsen P. Text messaging interventions for reducing alcohol consumption among risky drinkers: systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2021;116(5):1021–1033.

- Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

- Meredith S, Alessi S, Petry N. Smartphone applications to reduce alcohol consumption and help patients with alcohol use disorder: a state-of-the-art review. Adv Health Care Technol.Technol 2015;1:47–54.

- Song T, Qian S, Yu P. Mobile health interventions for self-control of unhealthy alcohol use: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(1):e10899.

- Prestwich A, Perugini M, Hurling R. Can the effects of implementation intentions on exercise be enhanced using text messages? Psychol Health. 2009;24(6):677–687.

- Redfern J, Thiagalingam A, Jan S, et al. Development of a set of mobile phone text messages designed for prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(4):492–499.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- Dulin PL, Alvarado CE, Fitterling JM, Gonzalez VM. Comparisons of alcohol consumption by time-line follow back vs. smartphone-based daily interviews. Addict Res Theory. 2017;25(3):195–200.

- Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih M-Y, et al. A Smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):566–572.

- McTavish FM, Chih M-Y, Shah D, Gustafson DH. How patients recovering from alcoholism use a smartphone intervention. J Dual Diagn. 2012;8(4):294–304.

- Muroff J, Robinson W, Chassler D, et al. Use of a Smartphone recovery tool for latinos with co-occurring alcohol and other drug disorders and mental disorders. J Dual Diagn. 2017;13(4):280–290.

- Dulin PL, Gonzalez VM, Campbell K. Results of a pilot test of a self-administered smartphone-based treatment system for alcohol use disorders: usability and early outcomes. Subst Abus. 2014;35(2):168–175.

- Malte CA, Dulin PL, Baer JS, et al. Usability and acceptability of a mobile app for the self-management of alcohol misuse among veterans (Step Away): pilot cohort study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9(4):e25927.

- Milward J, Deluca P, Drummond C, Kimergård A. Developing typologies of user engagement with the BRANCH alcohol-harm reduction Smartphone App: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(12):e11692.

- Monk RL, Heim D, Qureshi A, Price A. I have no clue what I drunk last night using Smartphone technology to compare in-vivo and retrospective self-reports of alcohol consumption. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126209.

- Garnett C, Crane D, West R, Brown J, Michie S. The development of Drink Less: an alcohol reduction smartphone app for excessive drinkers. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(2):296–307.

- Bell L, Garnett C, Qian T, Perski O, Williamson E, Potts HW. Engagement with a behavior change app for alcohol reduction: data visualization for longitudinal observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e23369.

- Poulton A, Pan J, Bruns LR, Sinnott RO, Hester R. Assessment of alcohol intake: retrospective measures versus a smartphone application. Addict Behav. 2018;83:35–41.

- Poulton A, Pan J, Bruns LR, Jr, Sinnott RO, Hester R. A Smartphone app to assess alcohol consumption behavior: development, compliance, and reactivity. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(3):e11157.

- Smith A, de Salas K, Lewis I, Schüz B. Developing smartphone apps for behavioural studies: the AlcoRisk app case study. J Biomed Inform. 2017;72:108–119.

- Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):86–89.

- McConnell T, Best P, Davidson G, Mceneaney T, Cantrell C, Tully M. Coproduction for feasibility and pilot randomised controlled trials: learning outcomes for community partners, service users and the research team. Res Involv Engag 2018;4:Article number: 32

- Michie S, Whittington C, Hamoudi Z, Zarnani F, Tober G, West R. Identification of behaviour change techniques to reduce excessive alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2012;107(8):1431–1440.

- Garnett C, Crane D, West R, Brown J, Michie S. Identification of behavior change techniques and engagement strategies to design a Smartphone app to reduce alcohol consumption using a formal consensus method. JMIR mHealth Uhealth. 2015;3(2):e73.

- Milward J, Khadjesari Z, Fincham-Campbell S, Deluca P, Watson R, Drummond C. User preferences for content, features, and style for an app to reduce harmful drinking in young adults: analysis of user feedback in app stores and focus group interviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(2):e47.

- Zhang MWB, Ward J, Ying JJB, Pan F, Ho RCM. The alcohol tracker application: an initial evaluation of user preferences. BMJ Innov. 2016;2(1):8–13.

- Williamson C, Dryden D, Palmer L, et al. An expert and veteran user assessment of the usability of the alcohol reduction App, drinks: ration: a mixed-methods pilot study. Under Rev. 9(10):e19720.

- Perski O, Baretta D, Blandford A, West R, Michie S. Engagement features judged by excessive drinkers as most important to include in smartphone applications for alcohol reduction: a mixed-methods study. Digit Heal. 2018;4:205520761878584.

- Crane D, Garnett C, Brown J, West R, Michie S. Factors influencing usability of a smartphone app to reduce excessive alcohol consumption: think aloud and interview studies. Front Public Heal 2017;5:e00039.

- Schueller SM, Muñoz RF, Mohr DC. Realizing the potential of behavioral intervention technologies. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22(6):478–483.

- Blonigen DM, Harris-Olenak B, Kuhn E, et al. Using peers to increase veterans’ engagement in a smartphone application for unhealthy alcohol use: a pilot study of acceptability and utility. Psychol Addict Behav 2020;35(7):829–839.

- Giroux D, Bacon S, King D, Dulin P, Gonzalez V. Examining perceptions of a smartphone-based intervention system for alcohol use disorders. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(10):923–929.

- Marcolino MS, Oliveira JAQ, D’Agostino M, Ribeiro AL, Alkmim MBM, Novillo-Ortiz D. The Impact of mHealth interventions: systematic review of systematic reviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(1):e23.