Gregory Rabassa was a master. Endowed with erudition and a refined sense of the art of translation, he earned from the critics the designation of divine translator. He was someone who enhanced the greatness of the text he worked with while respecting its inner truth and its secret poetic material. In fact, it is worth noting the enthusiasm of García Márquez for Rabassa's translation of Cien años de soledad (1967; One Hundred Years of Solitude, 1970), who, in a gallant and high-minded gesture, confessed that the translation was better than the original.

As early as the decade of the 1960s, the Master fell in love with Brazil. Compelled by this love, he disseminated the country's literature from his post at Columbia University and Queens College in New York until he became the most celebrated translator of the Portuguese and Spanish languages in the United States. From his efforts came translations of Machado de Assis, Jorge Amado, Clarice Lispector, Dalton Trevisan, Osman Lins, and many others. He insisted on promoting the innovative merits of Brazilian literature in the context of a difficult American market. His convictions earned him the status of being an authority on this matter, and led to many invitations to participate in literary and academic events.

I met Gregory Rabassa in Recife, Pernambuco, in 1963. When we were introduced, he showed me my first novel, Guia-mapa de Gabriel Arcanjo (1961; The Guidebook of Archangel Gabriel), all underlined. As the young writer I was then, the fact that an American intellectual demonstrated such enthusiasm, which he maintained until the end, moved me deeply and became a permanent impetus to my work.

During those Recife days, as we got to know each other better, his constant generosity offered me the opportunity to accompany him on a visit to Solar de Apipucos, the mythical residence of the internationally known figure Gilberto Freyre, with the intention of meeting the great discoverer of Brazil's roots.

I recall this encounter in great detail along with the emotions it stirred in me. In the salon decorated with colonial furniture and Northeastern art, the three of us met in comfortable harmony. The two masters, the master of Apipucos and Greg, were accompanied by the young Brazilian disciple who was passionately pursuing the trajectory of Brazil and witnessing at that very moment history being made in her presence, while savoring the famous pitanga liqueur that Gilberto Freyre himself prepared. It was obligatory to try the famous liqueur that he offered to friends and scholars who appeared at his home from different regions of the world.

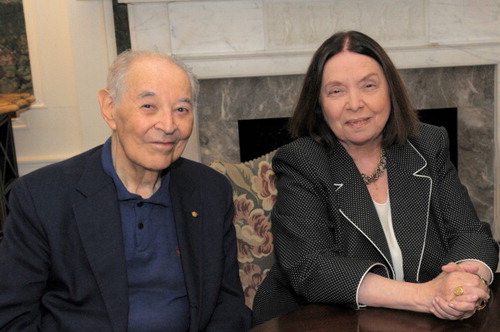

From the time of that luminous meeting in Recife, I diligently continued my connection with my friend and master, whether during my visits to New York, or when he came to visit Brazil. Each meeting, however, reinforced the pillars of a friendship that felt like family and that became even stronger through the years when they involved his wife Clementine. Known by friends as Clem, a respected Camões specialist, she received visitors with the delights of Greek cuisine that demanded hours of preparation until achieving its point of excellence. I had the good fortune to stay with them a few times in New York and in the Hamptons; they, in turn, were guests in my studio in Rio de Janeiro.

I remember with rare delight the days that Julio Cortázar and I spent at their country home, whose simplicity and sparseness made me think of Thoreau's Walden. That week, every evening after each one of us had spent the day working and reading, we gathered in the living room in anticipation of the dinner that Clem prided herself on preparing with devoted care. The four of us, enjoying aperitifs, shared stories of the world with laughter and enthusiastic gestures. Some stories were from academic sources and included the secret and canonical lives of writers, and others were of doubtful origin, circulated by intrigues that sustain the human imagination.

Those evenings, we also found ourselves performing impromptu imitations of the beloved Charlie Chaplin, as if the congenial English artist were there and egging us on to pay him homage. It was as if we were the Four Musketeers, each one of us testing, in the measure of human limits, our dose of happiness in skits that made unforgettable memories on those Hampton nights.

It was a privilege to enjoy the affective and cultural intimacy of the Rabassas. After all, it's rare to find intellectuals like Greg, who accumulate with simple modesty so much knowledge in different areas without falling into the attractive trap of arrogance. This was due, perhaps, to his Catalan and Cuban ancestry and his solid Anglo-Saxon education, which was consolidated with his passage through Dartmouth University. Such ethnic and linguistic ties guaranteed him the gift of overlaying human material with a patina of humor, subtle irony, and genuine compassion.

I highlight the times that Greg, always magnanimous, in introducing me for a talk at his university, attributed to me virtues that I strived to meet so as not to disappoint him and to not compromise his honor as a master. Recently in New York, at the Americas Society, he was invited to introduce the American edition of my novel Voices of the Desert, published by Knopf (Vozes do Deserto, 2005; translated by Clifford E. Landers, 2009), at a meeting organized by our friend Daniel Shapiro. Rabassa used language that, although discreet, revealed his humanistic erudition, before an audience of friends and admirers of Brazilian literature. After his introduction, we entered into a dialogue in which both of us gave proof of our love for the literature that bound us. And from the friendship that time strengthened, I was able to discern how his mind worked, his mental processes, his ability to insert humorous observations into aesthetic judgments, fed with examples that, even though historical, he made seem like daily occurrences. Each detail he offered invited us to enjoy his lucidity and his solid cultural knowledge.

Wherever he was, whether in the classroom, translating, or writing criticism, as well as in his role as intellectual, Greg presented himself coherently, never separating his daily life from his cultural work, his literary endeavors, and the admiration he held for writers.

Throughout our friendship I admired his goodness. This little appreciated virtue has been cast aside by modern society in the name of false sophistication; such attitudes do away with human compassion and propagate cynicism as a manifestation of intellectual power. Rabassa, however, did not hide acts, gestures, or words that nurtured the moving language of his heart.

Every time I was face to face with Greg's talent, which pulsed fully, without vacillation, it moved me and made me smile. I could, after all, say so much about his spirit, his impeccable intellectual and moral integrity, about the man whose memory is associated today with the Brazilian Academy of Letters, the largest Brazilian cultural institution for which I served as President in the year of its centennial, and where he was elected, unanimously, as a corresponding member. This is a category reserved for those who have done so much for Brazilian culture, as was the case of our illustrious and admirable Gregory Rabassa.

Now that he is gone forever, he leaves us a precious legacy. I admit I am fearful of returning to New York and not being able to visit him and Clem in their apartment on East 72nd Street, where they lived for so many years. A home in which I felt happy, immersed in affection and love, and where in their company we created memories I hold dear.

Rest in peace, friend Greg.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nélida Piñon

Nelida Piñon (Rio de Janeiro, 1937) is one of Brazil's leading women writers of fiction. She is a member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters and has been translated into many languages. Her dense prose is deeply nuanced with a rich lexicography and shifts of narrative perspective and register. She writes of her Spanish heritage and first-generation immigrant status in her epic novels Fundador (1969) and A república dos sonhos (1984; Republic of Dreams, 1989). A bold critic of the military dictatorship in the 1980s, her collection O calor das coisas (1980) addresses the repercussions of repression on Brazilian society.