Barely a day or two after the passing of Rosario Ferré, two other, older colleagues in the fellowship of writers also passed away: Harper Lee and Umberto Eco. Although the timing of their deaths was coincidental, there was something else Rosario Ferré shared with Lee and Eco besides the fact of being a celebrated writer: a contrarian, independent streak. Harper Lee published To Kill a Mockingbird and soon retreated from public view, uncomfortable in the role of literary celebrity; Umberto Eco, a professor at the University of Bologna, scholar, literary critic, and theorist of semiotics, wrote The Name of the Rose as something of a lark, having fun with Medieval semiotics and detective novels, and making fun of Jorge Luis Borges.

Rosario Ferré spent much of her adult life as a rebel of sorts: first rebelling from her family and her upbringing, and later from the expectations of her Puerto Rican compatriots of all political stripes, whom she confounded by often doing (or writing) the opposite of what they expected of her. Born into one of Puerto Rico’s wealthiest and most prominent families (her father, industrialist Luis A. Ferré, was the island’s third elected governor), during her youth and early adulthood she followed a predictable path for a daughter of the island’s upper class: high school studies at a prep school in Massachusetts, a BA in English and French from a liberal arts college in New York, and marriage soon after, which produced three children (Rosario Lorenza, Benigno Luis, and Luis Alfredo). When her mother, Lorenza Ramírez de Arellano, died a year into Governor Ferré’s term in 1970, Rosario fulfilled the duties of First Lady until her father’s term ended. By then, however, she had begun to change.

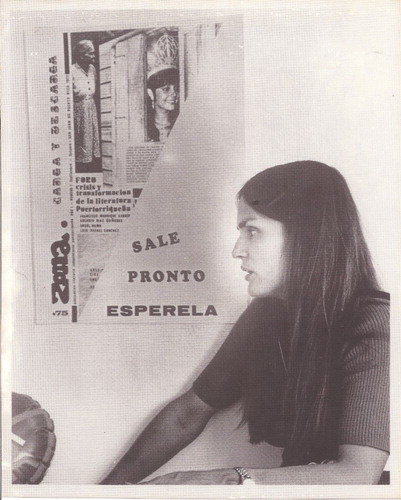

In her recent book, Memoir (2016), she links her growing rebelliousness to the rise of her literary vocation. Recalling how in 1969 she wrote her first short story, “The Glass Box,” on a portable typewriter while in bed with an illness, she adds that this eventually led, on the advice of Uruguayan critic Angel Rama, to founding the avant-garde literary journal Zona de Carga y Descarga (“Loading and Unloading Zone”) in 1970 with her cousin, poet and novelist Olga Nolla. Photos in Memoir show Rosario and Olga in jeans, seated on the floor of a bohemian apartment and smoking while working on the mock-ups of the journal, which was sold on the streets and in bookstores near the University of Puerto Rico for seventy-five cents. Zona’s success (and the scandal raised by its publication of groundbreaking gay fiction by Manuel Ramos Otero) gave Rosario entry into the Puerto Rican intelligentsia, which, for understandable historical reasons, has been and still is politically radical and favors Puerto Rican independence from the US. And so it happened that the daughter and First Lady of a pro-statehood Puerto Rican governor became, at least for a time, a vocal supporter of independence.

Rosario’s first published book, Papeles de Pandora (1976; partially translated as The Youngest Doll, 1991), appeared the same year as Luis Rafael Sánchez’s masterpiece La guaracha del Macho Camacho (1976; Macho Camacho’s Beat, 1989), and many of its stories shared the same populist style and sensibility of Sánchez’s novel, to which Rosario had arrived independently: “When Women Love Men,” “Amalia,” “Mercedes Benz 220 SL,” “The Seed Necklace,” and “Maquinolandera.” The latter, “Maquinolandera,” was not included in the book’s English translation, probably due to its daunting, slang-filled, hallucinatory narrative, as well as to its many references to salsa music lyrics. Another story, “Captain Candelario’s Heroic Last Stand,” collected in Rosario’s second narrative work, Maldito amor (1986; Sweet Diamond Dust and Other Stories, 1989), was a satiric portrayal of the “music wars” between cocolos (salsa music fans) and Americanized rockeros. In these stories one sees Rosario’s break with the pretentiously Europeanized, hyperrefined tastes of the island’s elite through the exaltation of Puerto Rican street slang, popular music, and mass media culture. Moreover, Rosario’s option in favor of blackness and racial mixing as key elements of Puerto Rican identity, which harked back to the poetry of Luis Palés Matos in the 1930s, also went against the traditional view by the island’s cultural elite of the jíbaro, the Puerto Rican peasant—generally (and inaccurately) rendered as being mostly of white, Hispanic ancestry—as an emblem of Puerto Rican identity. Issues of race, class, and gender are raised in Rosario’s short stories to a degree that was rare in earlier Puerto Rican narrative. Through Ferré and Sánchez, these issues would become predominant themes of younger Puerto Rican narrators of the 1970s and ’80s, such as Magali García Ramis, Carmen Lugo Filippi, Manuel Ramos Otero, Edgardo Rodríguez Juliá, and Ana Lydia Vega.

Feminism was another angle of attack in Rosario Ferré’s rebellion. Puerto Rican women’s struggles for suffrage and collective rights were known and documented through the first half of the twentieth century in figures as varied as Ana Roqué de Duprey and Luisa Capetillo. The works of one of Puerto Rico’s greatest lyric poets, Julia de Burgos (who was a woman of color), had already broken some social and literary barriers. In 1980, while living in Mexico with her second husband, Mexican writer Jorge Aguilar Mora, Rosario published Sitio a Eros (Siege of Eros), a groundbreaking collection of critical essays on major women authors from Europe and the Americas of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (ranging from Flora Tristán and George Sand to Sylvia Plath, Virginia Woolf, and Alexandra Kollontai), studying the relation between sexuality and writing in their works. Although the essays were thoughtful and serious, in her fiction Rosario’s feminism, with its eroticism and sarcastic sense of humor, had a peculiarly irreverent cast: witness her story “When Women Love Men,” which features as one of its main characters “Isabel la Negra,” a black woman who ran the most notorious brothel in Ponce, Ferré’s hometown, where politicians and magnates rubbed shoulders with bootleggers and other unsavory characters (narcos had not yet entered the picture). Humor also enlivens Rosario’s second foray into feminist literary criticism, El coloquio de las perras (1991; “The Bitches’ Colloquy”), inspired by Cervantes’s short story “El coloquio de los perros” (“The Dogs’ Colloquy,” 1590). In this book two female dogs discuss and denounce the mysogyny present in the novels of the Latin American Boom writers while taking a stroll on the grounds of the El Morro fortress in Old San Juan. Another expression of Rosario’s feminist satirical penchant is the book of Neo-Baroque poems Fábulas de la garza desangrada (Fables of the Bleeding Heron, 1982), in which she rewrites the stories of famous literary and mythical women victimized by men, turning the women (Daphne, Antigone, Ariadne, and others) into the aggressors.

Rosario Ferré, at home with Nilita Vientós Gastón, a Puerto Rican femme de lettres and specialist on Henry James, circa early 1980s. Courtesy of Benigno Trigo.

But perhaps Rosario Ferré’s most unexpected rebellion occurred in the late 1990s, when she published in 1995 her English-language novel The House on the Lagoon, and in 1997 an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times, “Puerto Rico, USA,” in favor of Puerto Rico’s annexation as the fifty-first state of the Union. This time the expressions of shock and dismay came from Puerto Rican progressives and pro-independence supporters, who even accused her of being “a fraud,” as Beatriz Ramírez Betances has remembered in her recent article “Rosario Rebelde” in the Puerto Rican online journal 80grados. Twenty years later, Ramírez Betances observes, Ferré’s constant questioning of received ideas can be more clearly understood: “Although it [Ferré’s New York Times article] is still infamous, and although many of its exclamations, generalizations, and hyperboles can make the hairs stand on end on even the least nationalist among us, it nevertheless truly underscored the fact that a great many Puerto Ricans do use two languages in the Boricua archipelago, and that we’re not so homogenous after all.” Ferré’s decision to use English in the first editions of some of her late works was also, it should be pointed out, in harmony with the comments of the Marxist and pro-independence Puerto Rican author of an earlier generation, José Luis González, who in his book El país de cuatro pisos (1980; The Four-Storeyed Country, 1993) proposed that increased knowledge of English (as well as French) could further Puerto Rico’s decolonization by allowing the island to interact more closely with its non Spanish-speaking neighbors in the Caribbean.

I wish to close with a personal remembrance: in February 1995, I was presenting an afternoon lecture in the Seminario de Estudios Hispánicos Federico de Onís at the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras. As I glanced across the room at my audience of faculty and students, I saw sitting in the back a person I immediately recognized as Rosario Ferré. My talk was on Julio Cortázar, one of her favorite authors, about whom she had written a perceptive book on his affinity with Romantic authors; afterwards, we chatted briefly about Cortázar and about the years of Zona de Carga y Descarga. I was struck then by her kindly, soft-spoken, almost shy demeanor. Truly the brave and determined Rosario Ferré, who was deprived of speech by illness in the last years of her life, had already found in writing her strongest and most lasting voice, as well as a permanent place of honor in the canon of Puerto Rican letters.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Aníbal González

Aníbal González is Professor of Modern Latin American Literature at Yale University and the author of six books of criticism. He has recently finished a new book on the role of religion in the contemporary Latin American novel.

Works Cited

- Ferré, Rosario. Memoir. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2015.

- González, José Luis. Puerto Rico: The Four-Storeyed Country and Other Essays. Trans. by Gerald Guinness. Princeton: Markus Wiener, 1993.

- Ramírez Betances, Beatriz. “Rosario Rebelde.” 80grados: Prensa sin Prisa. February 26, 2016. Web. Accessed March 4, 2016. http://www.80grados.net/rosario-rebelde/