The impetus for proposing the theme of the Brazilian backlands for a special issue of Review came from my total immersion in the world of the sertão, its myths and realities, when I had the privilege of doing the re-translation of Euclides da Cunha's momentous book Os sertões for Penguin in 2010. This humbling task forged its own travessia, a word used in books about the backlands and its literature to refer to a crossing having spiritual as well as physical dimensions. The journey challenged me to revisit the region, where I had lived as a child, and its complex history, geography, and language; translating the book was a forceful reminder of how foundational it was in giving new life to an imagined world that has inspired generations of Brazilian and international writers and artists.

Da Cunha's epic produced a firestorm immediately upon its publication in 1903, inciting public debate and a crisis of conscience regarding the “two Brazils” and the neglect of Brazil’s remote regions and its impoverished populations by the coastal elites—a discussion that continues dominant to this day about the economic and social divides in South America's largest nation. This book also raised awareness of the culture of the backlands and the northeastern region, the diversity of its people, music, art, and language—a rich blend derived from sixteenth-century Portuguese, indigenous, and African languages. First translated into English by Samuel Putnam in 1943, and subsequently into many different languages, Os sertões has been influential in introducing not only the backlands, but also Brazil, to audiences around the world. The direct literary descendant of da Cunha is the famed João Guimarães Rosa, whose Joycean epic set in Minas Gerais, Grande sertão: Veredas (1956; The Devil to Pay in the Backlands, 1963), is long overdue for re-translation. To this day, Brazil and its five distinct regions (North, Northeast, Center-West, Southeast and South) remain an enigma to most people. The opening ceremony of the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro made a point of celebrating Brazil's regional cultures, and the diversity so artistically displayed came as a surprise to many. Thus it seems to us appropriate to focus on Brazil's northeastern backlands from an interdisciplinary perspective and to offer insights through scholarly essays and creative pieces into the region's abundant literary and artistic heritage.

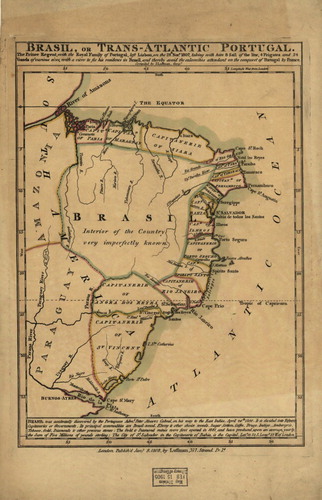

The sertão covers a vast landmass that spans the Northeastern states of Bahia, Minas Gerais, Sergipe, Alagoas, Pernambuco, Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte, and Ceará. The word sertão was originally a sixteenth-century Lusitanian term for any unknown land, and in time it came to refer to any part of the interior west of the coast. Scholars who have written extensively about the forbidding interior of the region have noted how it has inspired an “imagined geography” not only in Brazil but in Europe as well.Footnote1 In part, the stimulus to imaginary versions of the backlands was due to the fact that the region was unexplored, a process that took several centuries. The early Portuguese explorers reported “marvelous things,” spinning fantastic tales about the land and its indigenous population and promising great riches for the sponsors of their expeditions. The maps themselves used “a barbaric vocabulary to represent the inhabitants and wonders of those backlands,” and the land itself was often more terrifying than even the most imaginative chroniclers could describe.Footnote2 André Heráclio do Rêgo, in “O sertão e a geografia,” quotes the historian Teodoro Sampaio:

. . . the great riches of the backlands were guarded by very high mountains, by immense, impenetrable rivers, by fierce tribes and monsters of terrifying aspect. Never in man's imaginings had treasures been found that weren't defended by horrific monstrosities.Footnote3 (my translation)

In this issue of Review we have sought to provide a historical as well as a multidisciplinary view of the backlands, featuring scholarship and creative work that reflect both the myths and the realities of northeastern Brazil. The essays cover a wide range of topics in the areas of history, literature, film, music, and art, and collectively they reflect recurring themes and preoccupations that are common to the region and, by extension, to the nation: the northeast cycles of endemic drought and economic crisis, agrarian reform, poverty, migration, race and gender relations, and power struggles between rich and poor and the challenge of social inclusion. The figure of the jagunço (backlands bandit) is explained and celebrated in both the essays and the creative pieces. We learn of the legend of the famous outlaw Lampião and his beautiful partner, Maria Bonita, through song, poetry, and narrative. Luiz Fernando Valente offers an in-depth analysis of the importance of Euclides da Cunha’s Os sertões, arguing that its power comes from the hybrid nature of the prose: a mix of literary, scientific, and historical writing. This study goes on to examine the dialogue of da Cunha’s work with José de Alencar's O sertanejo (1875; The Backlander), closely comparing the two books and also showing how they fit into the context of Brazilian letters, historical tradition and cultural environment. Valente also shows how da Cunha's legacy is that of transcending stereotypes when analyzing a national identity. Glen S. Goodman’s article, “A Stone in Brazil’s Shoe: The Dystopian Northeast in the Brazilian National Imaginary,” traces the history of national perceptions of the Northeast from Euclides da Cunha to the present day, concluding that the pendulum swings between idealization and vilification of the region and its people of mixed ethnicities persist and have even impacted the attitudes towards the current beleaguered president of the country. Renata Wasserman writes about “Women, Bandits and Power in the Brazilian Northeast” in the work of Rachel de Queiroz (1910–2003). Queiroz is one of the group of northeastern writers, along with José Lins do Rego, Graciliano Ramos, and Jorge Amado, whose subject was the sertão and who came to dominate the national literary scene in the first half of the twentieth century. Wasserman focuses on the themes of gender and power in Queiroz’s work and her reception by male peers, eventually becoming the first woman to join the Brazilian Academy of Letters. Charles Perrone's article, “Backlands Bards: From Fine Folk Verse to Lofty Lapidary Lyric,” provides a fresh view of Northeastern lyric and song through the work of iconic Brazilian poets and popular songwriters from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, focusing on the work of the major poet João Cabral de Melo Neto (1920–1999) and tracing the links between “backland bards” and the regional revival in urban popular music in the 1970s. His article illustrates how the “abundant art of the people of the backlands” has fertilized canonical verse.

Earl Fitz's essay “Clarice Lispector as a Northeastern Writer” makes an important new contribution to the study of this celebrated writer, providing evidence of the importance of the Brazilian Northeast in her life and texts. Though she is not normally associated with this region of Brazil and commonly characterized as an urban writer concerned with the inner landscape of her characters, Fitz provides convincing evidence of Lispector's preoccupation with the people and themes of the Northeast by discussing relevant passages from a number of her works, in particular her last novel, A hora da estrela (1977; The Hour of the Star, 2011). Larry Crook’s essay, “Echoes of the Northeast: Luiz Gonzaga and the Soundscape of Música Nordestina,” analyzes Pernambucan Luiz Gonzaga's (1912–1989) role in the creation and rise of Northeastern music and his signature genre, the baião, as a “visceral way for audiences and musicians throughout Brazil to experience ideas about Brazil as a modern nation linked to a traditional past rooted firmly in the sertão.” He illustrates how Gonzaga incorporated the rich folk traditions of the interior, where he grew up, into his work, thus creating a new “soundscape” for the sertão. Darlene J. Sadlier's article “The Sertão on Screen: From the Silent Era to the Pernambuco Revival” provides a historiography of representations of the backlands in Brazilian cinema, showing how the region has played a large role in the evolution of the genre from the early twentieth century before the cinema novo period to 2015. Here we are introduced both to classical films as well as lesser-known works. Sadlier concludes with a commentary on Walter Salles's Central do Brasil (1998; Central Station) that presents an uncommon vision of a colorful sertão that “has certain redemptive powers.” Kimberly Cleveland's essay “Coming and Going: Movement of Folk Art from Brazil’s Backlands” offers a rare view that is mostly ignored by scholars due to the provincial nature of the work that is closely associated with local communities. She points out the interesting fact that while local in its inception, its circulation has been increasingly broader, from regional markets to national and international private and institutional collections. Focusing on the work of José Celestino da Silva (1955–2015), Vitalino Pereira dos Santos (1909–1963), and Manuel Eudócio Rodrigues (1931–2016), Cleveland discusses in detail their individual and common characteristics, showing how the artists use locally available materials to depict the scenes of regional life. Her description of Vitalino's clay Lampião figures offers fascinating insights into the aesthetics of the cangaço.

Victoria Shorr's travel essay, “On the Road to Maria Bonita,” depicts her impressions of the sertão upon her first visit to the region to do research for her novel The Backlands (2015) with the Brazilian photographer Anna Mariani, whose work she admired at an art exhibit in São Paulo. A portion of a longer travel narrative, “On the Road to Maria Bonita” describes her conversations with villagers in the region where Maria Bonita was born and grew up, and where she lived with her shoemaker husband until she met and ran away with Lampião. Her descriptions of the drought-ridden landscape, the physical features of the sertanejo, the unique architecture of the small villages and occasional ghost towns that dot the landscape, and the characteristic speech of the inhabitants of the remote area, allow those unfamiliar with the region to grasp something of the identity of the sertão. Also included in the academic section are images of works referenced in the essays on folk art and film.

The creative selections tie to the essays and constitute a broad representation of literary period, genre, gender, and ethnicity. We have included iconic and new literary voices, expressed in poetry, song, cordel folk poetry, the novel, the short story, the crónica (chronicle), drama, and the travel essay. The translators of the creative pieces are both established as well as rising translators. Some obvious figures could not be included due to limitations of time and space, however we trust that the selection offered will give readers a coherent literary and cultural perspective on the backlands.

The selection of creative works begins with a chapter from José de Alencar's still untranslated novel O sertanejo (1875; The Backwoodsman). Alencar (1829–1877) was the leader of Brazil's Romantic movement that later inspired Euclides da Cunha with his vision of a national literature that would synthesize indigenous, African, and European influences into a new cultural product. He was one of the first to explore the linguistic wealth and diversity that was Brazilian Portuguese, and da Cunha and then João Guimarães Rosa would push this vision forward to create dazzling narratives spun with innovative language that tests readers and translators alike.

We included an excerpt from Part I of Euclides da Cunha's Os sertões, which, like the Alencar selection, focuses on the figure of the backlander and his relationship to nature. Continuing with the novel, we chose the famous chapter from Graciliano Ramos's Vidas secas (1938; Barren Lives, 1968) about the dog Baleia (Whale), one of the most memorable characters in Brazilian literature. Here again, we see a depiction of the relationship of man, beast, and nature in the inhospitable sertão. Marcelino Freire's short story, “Ricas Secas” (2015; “Barren Rich”), translated by Johnny Lorenz, is a contemporary inversion of the Ramos tale, in which he imagines a wealthy family fleeing water shortages in São Paulo in a reverse migration to the sertão. A selection from Victoria Shorr's novel, The Backlands (2015), gives an interpretation of the love story of Lampião and Maria Bonita in the political and geographical context of the territory that Lampião and his men ruled, a swath of sertão as large as the country of France. As a complement to Earl Fitz's essay on Clarice Lispector's Northeast, we include an excerpt of Ben Moser's translation for New Directions of her last novel, A hora da estrela (1977; The Hour of the Star, 2011).

The poetry selections range from Romantic poet Castro Alves's verses dedicated to the backlands pilgrims, to signature works by João Cabral de Melo Neto (translations by Richard Zenith and W.S. Merwin) and Charles Perrone's translations of verse by Marcus Morais Accioly, a leading poet from Pernambuco, and Patativa do Assaré, a poet and songwriter from the interior of Ceará. Also featured in the poetry section are Alexis Levitin's translations of Salgado Maranhão, the self-taught poet and songwriter whose production is influenced by the chants of pilgrims walking through his home state of Maranhão. Two popular songs derived from the cangaço tradition, “Mulher Rendeira” (“Lace-Making Woman”) and “Acorda Maria Bonita” (“Wake Up, Maria Bonita”; part of Luiz Gonzaga's repertoire), are translated by Eliot Sharpe Valadares. No selection of creative writers of the backlands would be complete without Ariano Suassuna, one of Brazil's leading dramatists, whose comic play Auto da Compadecida (The Act of Our Lady of Mercy) is a witty satire of backlands society and politics in the guise of the misadventures of backlands rogues. Luzilá Gonçalves, a novelist and social historian, contributed two chronicles from her weekly column for the Diário de Pernambuco on the subject of the drought. Two short stories are about gender relations in the remote Northeast: Rachel de Queiroz's “Isabel,” translated by Renata Wasserman, is a chilling tale of an abused spouse, and Nélida Piñon's “Harvest” is a powerful narrative about a man who leaves his wife to satisfy his wanderlust. Two excerpts of cordel poetry feature a fictional meeting of two famous outlaws in Antonio Teodoro dos Santos's “O Encontro de Lampião com Dioguinho” (“The Meeting of Lampião and Dioguinho”), translated by Ezra Fitz, and Mark J. Curran's translation of Rodolfo C. Cavalcante's morality tale, “A moça que bateu na mãe e virou cachorra” (“The Girl Who Beat up her Mother and Was Turned into a Dog”).

I would like to thank all the scholars, writers, translators, and artists who contributed to this issue and whose work helps to convey the imagined geography and the stark truths of the Brazilian backlands. Special recognition is due to Daniel Shapiro, whose steady editorial hand has guided and facilitated all the efforts that went into the making of Review 92/93.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elizabeth Lowe

Elizabeth Lowe, founding Director of the Center for Translation Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, is translator of both classical and contemporary Brazilian literature. Her re-translation of the iconic novel by Euclides da Cunha, Os sertões (1902; Backlands: The Canudos Campaign, 2010), earned her recognition by the Brazilian Academy of Letters. She is the author of The City in Brazilian Literature (1982) and co-author with Earl E. Fitz of Translation and the Rise of Inter-American Literature (2007). She is currently Adjunct Professor in the New York University M.S. in Translation program.

Notes

1 André Heráclio do Rêgo, “O sertão e a geografia,” Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros 63 (April 2016): 42-66. <http://www.revistas.usp.br/rieb/article/view/114856>

2 Ibid, 43.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid, 44. Darlene J. Sadlier writes about Brazil as an imagined island in her book Brazil Imagined:1500 to the Present (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008).