ABSTRACT

Supposed dinosaur remains were collected between 1859 and 1906 in the Lower Cretaceous Recôncavo Basin (Northeast Brazil). Since these materials remained undescribed, and most were considered lost. Recently, some of these historical specimens were rediscovered in the Natural History Museum of London, providing an opportunity to revisit them after 160 years. The specimens come from five different sites, corresponding to the Massacará (Berriasian-Barremian) and Ilhas (Valanginian-Barremian) groups. Identified bones comprise mainly isolated vertebral centra from ornithopods, sauropods, and theropods. Appendicular remains include a theropod pedal phalanx, humerus, and distal half of a left femur with elasmarian affinities. Despite their fragmentary nature, these specimens represent the earliest dinosaur bones discovered in South America, enhancing our understanding of the Cretaceous dinosaur faunas in Northeast Brazil. The dinosaur assemblage in the Recôncavo Basin resembles coeval units in Northeast Brazil, such as the Rio do Peixe Basin, where ornithopods coexist with sauropods and theropods. This study confirms the presence of ornithischian dinosaurs in Brazil based on osteological evidence, expanding their biogeographic and temporal range before the continental rifting between South America and Africa. Additionally, these findings reinforce the fossiliferous potential of Cretaceous deposits in Bahia State, which have been underexplored since their initial discoveries.

Introduction

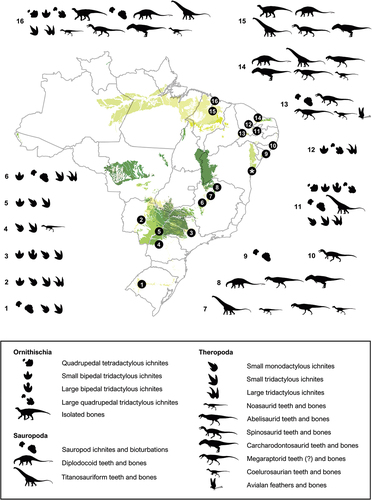

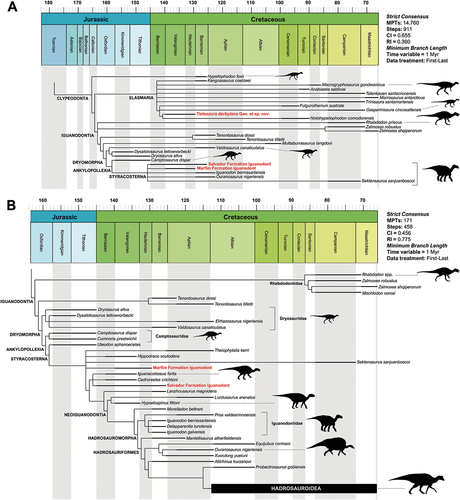

The Cretaceous strata in Brazil cover approximately 19% of its territory (Schobbenhaus and Neves Citation2003; Da Silva et al. Citation2003) and have yielded a noteworthy ichnological and osteological dinosaur fossil record (Campos and Kellner Citation1991; Kellner and Campos Citation1999, Citation2000; Bittencourt and Langer Citation2011). The main dinosaur-bearing localities come from Lower Cretaceous deposits, especially in the Northeast region of the country (; see also Supplementary Data). The dinosaur components are mainly represented by rebbachisaurids (Lindoso et al. Citation2019) and titanosaurian sauropods (Zaher et al. Citation2011; Ghilardi et al. Citation2016; Carvalho et al. Citation2017), associated with abelisauroid (Zaher et al. Citation2020; De Souza et al. Citation2021), spinosaurid (Kellner and Campos Citation1996; Sues et al. Citation2002, França et al. Citation2022; Lacerda et al. Citation2023), carcharodontosaurid (Medeiros et al. Citation2014, Citation2019; Pereira et al. Citation2020), megaraptoran (Aranciaga-Rolando et al. Citation2018), and coelurosaurian theropods (Kellner Citation1999; Naish et al. Citation2004; Sayão et al. Citation2020), including avialans (Carvalho et al. Citation2015, Citation2021).

Figure 1. Cretaceous deposits from Brazil and their dinosaur assemblages, emphasising occurrences from the Lower Cretaceous units. 1–3, Botucatu Formation (Paraná Basin); 4–5, Goio Erê and Rio Paraná formations (Caiuá Group); 6–8, Abaeté, Quiricó, and Três Barras formations (Sanfranciscana Basin); 9–10, Maceió and Feliz Deserto formations (Sergipe-Alagoas Basin); 11, Antenor Navarro, Sousa, and Rio Piranhas formations (Rio do Peixe basins); 12, Quixoá (Icó) and Malhada Vermelha formations (Iguatu basins); 13, Rio da Batateira, Crato, and Romualdo formations (Araripe Basin); 14, Açu Formation (Potiguar Basin); 15, Itapecuru Formation (Parnaíba Basin); 16, Alcântara Formation (São Luís-Grajaú Basin). The asterisk exhibits the occurrences from the Recôncavo Basin presented by this work. Detailed information on each occurrence is provided in the Supporting Information (File S1). Modified from ‘Carta Geológica do Brasil ao Milionésimo’ (Souza et al. Citation2004).

Regarding the ornithischian record, the occurrences are scarce and most of them doubtful. They include putative iguanodontian centra coming from the Recôncavo Basin (Mawson and Woodward Citation1907), an ornithischian ischium (MN 7021-V) – later reinterpreted as a spinosaurid rib (Leonardi and Borgomanero Citation1981; Machado and Kellner Citation2007)—, and a partial preserved caudal vertebra (UFMA 1.10.240) from the Alcântara Formation (Medeiros and Schultz Citation2002; Medeiros et al. Citation2007), which was briefly described and assigned to cf. Ouranosaurus by Novas (Citation2009). In contrast, the ichnological record concerning this group is abundant and widespread amongst the Brazilian Lower Cretaceous deposits, mainly in the small half-grabens of the Rio do Peixe and Iguatu basins. This record includes ichnites of putative thyreophorans, small-to-medium-sized bipedal and graviportal ornithopod trackmakers (Leonardi Citation1994; Leonardi and Carvalho Citation2002, 2021).

Although most of these dinosaur-bearing units have been extensively explored over the last decades, the dinosaur components of the Recôncavo Basin units remain poorly understood. Most of the data regarding the Recôncavo Basin dinosaurs come from historical publications older than a century ago (e.g. Allport Citation1860; Marsh Citation1869; Woodward Citation1888; Mawson and Woodward Citation1907). In addition, most of these materials are considered lost by subsequent works (e.g. Kellner and Campos Citation2000). Although some re-evaluations of other archosaurs from the Recôncavo Basin have been performed in recent years (e.g. Rodrigues and Kellner Citation2010; Souza et al. Citation2015, Citation2019), the putative dinosaur material remained undescribed in detail, with few mentions of these specimens in the literature (e.g. Bittencourt and Langer Citation2011).

Notwithstanding, some of these historical materials were recently located in the palaeontological collection of the Natural History Museum of London (NHM) and are presented herein. The specimens described below represent the first dinosaur bones collected in South America (e.g. Allport Citation1860) and revealed a diversified dinosaur fauna in the Recôncavo Basin. This historical dinosaur bones enhance our understanding about the faunal succession in Gondwana during the earliest Cretaceous. Furthermore, this work aims to encourage Brazilian palaeontologists to conduct further fieldwork in the basins of Bahia State, as they represent one of the earliest Cretaceous faunas in South America and indicates potential new important discoveries (e.g. Souza and Campos Citation2018).

Historical background and geological settings

The Recôncavo Basin is a NW – SE-oriented half-graben located in Bahia State, covering approximately 12.000 km2 and reaching about 10 km of maximum thickness (Prates and Fernandez Citation2015). The basement of this basin is composed of Neoproterozoic rocks from the São Francisco Craton, characterised by a network of high-dip synthetic normal faults divided into three structural blocks: Low, High, and Platform (Destro et al. Citation2003). The depositional history of the Recôncavo Basin can be separated into five phases: a syneclysis stage in the Permian, a pre-rift stage during the Tithonian to Early Berriasian (Dom João Local Age), a syn-rift stage starting in the Early Berriasian and extending to the Early Aptian (Rio da Serra, Aratu, Buracica, and Jiquiá local ages), and a post-rift stage ranging from the Late Aptian to Early Albian (Alagoas Local Age), later covered by Neogene (Miocene and Pliocene) and Quaternary deposits (Viana et al. Citation1971). The syn-rift sequence of the Recôncavo Basin is commonly referred in the literature as the ‘Bahia Supergroup’, which comprises the Santo Amaro Group (Itaparica, Água Grande, Candeias and Maracangalha formations), the Ilhas Group (Marfim, Pojuca and Taquipe formations), the Massacará Group (Salvador and São Sebastião formations), and the Marizal Formation (Caixeta et al. Citation1994).

According to Da Silva et al. (Citation2007), the beginning of the syn-rift phase resulted in the formation of several tectonic lakes with differential subsidence, represented by the Candeias and Maracangalha formations. The Tauá and Gomo members (Candeias Formation) are deposited under lacustrine conditions, characterised by clays rich in organic matter. They are associated with gravitational flows and fluvial system tracts of the Pitanga and Caruaçu members (Maracangalha Formation), which are related to the reactivation of transcurrent faults. By contrast, the Ilhas Group encompasses a prograding deltaic paleoenvironment, based on the succession of sandstones and shales (e.g. Marfim Formation), as well as mudstones and limestones (e.g. Pojuca Formation). The Catu Member (Marfim Formation) indicates several changes in the development of lacustrine systems. The high relief formed by the Salvador Fault on the eastern margin gradually intruded flagstones and conglomeratic sandstone facies of the Sesmaria Member (Salvador Formation) into these tectonic lakes. The establishment of the prograding deltaic system of the Pojuca Formation indicates episodic marine incursions (Santiago Member) that supplied these tectonic lakes. A subsidence decrease, which probably occurred during the Early Aptian (Arai Citation2014; but see also Assine et al. Citation2016; Parméra et al. Citation2019), progressively silted up these lacustrine systems with fluvial sediments from the São Sebastião Formation. In the western part of the basin, erosive processes on the Ilhas Group developed a canyon system that is filled by the alluvial fans deposits of the Taquipe Formation. The post-rift phase, represented by the Marizal Formation, was deposited through the formation of alluvial and delta fans.

The deposits of Recôncavo Basin hold a relatively diversified fossil record, including microfossils (e.g. foraminifera, ostracods, and ‘conchostraceans’), molluscs (e.g. bivalves and gastropods), and plant remains, such as palynomorphs, amber, and silicified conifer logs (Milhomem et al. Citation2003). Vertebrate remains are represented by cephalic fins of hybodontiform sharks (Acrodus nitidus Woodward Citation1888), several occurrences of actinopterygians (e.g. Ellimmichthys longicostatus (Cope Citation1886); ‘Lepidotes’ mawsoni Woodward Citation1888) and sarcopterygians (e.g. Mawsonia gigas Mawson and Woodward Citation1907), remains of chelonians and putative plesiosaurians (Marsh Citation1869; Woodward Citation1891), some crocodilian teeth and bones (e.g. ‘Thoracosaurus bahiaensis’, Sarcosuchus hartti; Souza et al. Citation2015; Souza Citation2019), pterosaurian teeth (Woodward Citation1891; Rodrigues and Kellner Citation2010), and supposed dinosaur specimens (Allport Citation1860; Hartt Citation1870; Mawson and Woodward Citation1907; Figueiredo and Gallo Citation2021).

The outcrops from which the historical material was collected are recognised by some studies as belonging to the ‘Bahia Supergroup’, but without an assignment to a specific horizon (e.g. Rodrigues and Kellner Citation2010; Bittencourt and Langer Citation2011). Hartt (Citation1870) and Hartt and Agassiz (Citation1875) regarded these deposits as potentially equivalent to the ‘Neocomian’ strata of Europe. Later, Derby (Citation1878) assigned the entire coastal basin from Bahia into the Lower Cretaceous. More recently, Souza et al. (Citation2015) suggested that these historical localities probably belong to the Late Valanginian to Early Barremian Ilhas Group (Caixeta et al. Citation1994). However, given the high urbanisation of the Salvador area and the absence of a refined stratigraphic control during the collection of these materials, Souza et al. (Citation2019) suggested some cautiousness to assign such rocks to any more specific unit and age.

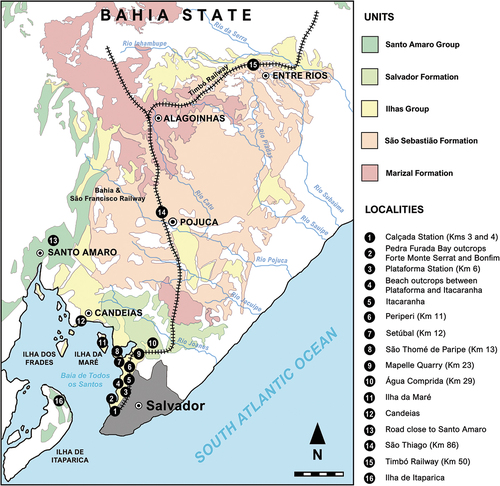

Nevertheless, we bring here some novelties based on the descriptions of NHM collection labels, in which explain the specific lithofacies that each specimen recovered and allowing a more refined horizon assignment. According to the collection labels, the specimens reviewed here were recovered from five different localities through field seasons from 1859 to 1906 (). The outcrops were first described by Allport (Citation1860) and later explored by Mawson, in which compiled them into a detailed map in Mawson and Woodward (Citation1907). We evaluated these sites and compared the data of collection labels within stratigraphic studies of the Recôncavo Basin (e.g. Da Silva et al. Citation2007), plotting them at the ‘Carta Geológica do Brasil ao Milionésimo’ (Souza et al. Citation2004). The revised map () shows that the prospected localities match with the outcrops of the Ilhas Group and the Salvador Formation, correlating with the specific lithofacies in which the specimens were found ().

Figure 2. Historical fossil-bearing localities of the Lower Cretaceous Recôncavo Basin in Northeast Brazil, modified from Allport (Citation1860) and Mawson and Woodward (Citation1907). Localities which have yielded dinosaur remains are described in Table 1. Geographic range of the geological units was taken from ‘Carta Geológica do Brasil ao Milionésimo’ (Souza et al. Citation2004). Scale bar = 25 km.

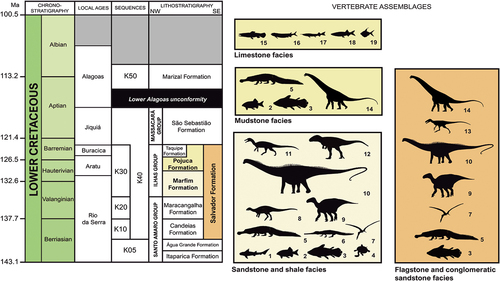

Figure 3. Stratigraphic chart of the Lower Cretaceous Massacará and Ilhas groups (Recôncavo Basin), highlighting their vertebrate assemblages (coloured boxes). 1, hybodontiforms (Acrodus nitidus); 2, semionotids (‘Lepidotes’ spp.); 3, mawsoniids (Mawsonia gigas); 4, undetermined testudines; 5, pholidosaurids (Sarcosuchus hartti); 6, putative gavialoids (‘Thoracosaurus bahiaensis’); 7, pterosaurs (anhanguerids); 8, elasmarians (Tietasaura derbyiana gen. et sp. nov.); 9, iguanodontians; 10, diplodocoids; 11, spinosaurids; 12, carcharodontosaurians; 13, undetermined small theropods (tyrannosauroids?); 14, titanosaurs (lithostrotians); 15, amiids (Calamopleurus mawsoni); 16, cladocyclids (Cladocyclus mawsoni); 17, aspidorhynchids (‘Belonostomus’ carinatus); 18, undetermined clupeomorphs (Scrombroclupeoides scutata); 19, ellimmichthyiforms (Ellimmichthys longicostatum, Ellimmichthys spinosus, Scutatuspinosus itapagipensis). References regarding the vertebrate occurrences were taken through bibliographic survey (see text). Geological chart modified from Da Silva et al. (Citation2007). Silhouettes from several sources.

Table 1. Collection details of the specimens described in this work.

Institutional abbreviations

CPPLIP, Centro de Pesquisas Paleontológicas Llewellyn Ivor Price, Peirópolis, Brazil; GSI, Geological Survey of India, Kolkata, India; IRSNB, MACN, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘Bernadino Rivadavia’, Buenos Aires, Argentina; MCF-PVPH, Museo ‘Carmen Funes’ - Paleontología de Vertebrados Plaza Huincul, Plaza Huincul, Argentina; Museo de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina; MN, Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; MPM, Museo Regional Provincial ‘Padre Jesús Molina’, Río Gallegos, Argentina; MUCPv, Museo de la Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Neuquén, Argentina; NHM, Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom; SGB, Serviço Geológico Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; SHN, Sociedade de História Natural, Torres Vedras, Portugal; UFMA, Universidade Federal do Maranhão, São Luís, Brazil; UFRJ, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; UNPSJB, Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco, Comodoro Rivadavia, Argentina. CPPLIP, Centro de Pesquisas Paleontológicas Llewellyn Ivor Price, Peirópolis, Brazil; GSI, Geological Survey of India, Kolkata, India; IRSNB, MACN, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘Bernadino Rivadavia’, Buenos Aires, Argentina; MCF-PVPH, Museo ‘Carmen Funes’ - Paleontología de Vertebrados Plaza Huincul, Plaza Huincul, Argentina; MLP, Museo de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina; MN, Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; MPM, Museo Regional Provincial ‘Padre Jesús Molina’, Río Gallegos, Argentina; MUCPv, Museo de la Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Neuquén, Argentina; NHM, Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom; SGB, Serviço Geológico Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; SHN, Sociedade de História Natural, Torres Vedras, Portugal; UFMA, Universidade Federal do Maranhão, São Luís, Brazil; UFRJ, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; UNPSJB, Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco, Comodoro Rivadavia, Argentina.

Systematic Palaeontology

Dinosauria Owen Citation1842

Ornithischia Seeley Citation1888

Genasauria Sereno Citation1986

Neornithischia Cooper Citation1985

Cerapoda Sereno Citation1986

Ornithopoda Marsh Citation1881

Elasmaria Calvo et al. Citation2007

Tietasaura gen. nov.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:814725BB-A522-465F-975D-1755A11C3956

Etymology

The generic epithet is a combination of Tieta (nickname for Antonieta in Portuguese) and -saura (σαύρα), the genitive form of -saurus and meaning lizard in ancient Greek. The name Tieta honours the main character from the homonymous novel ‘Tieta do Agreste’ by the famous author Jorge Amado, who was born in Bahia and lived in Salvador City. The name Antonieta further means ‘priceless’, alluding to the value of Tietasaura derbyiana sp. nov. as the first nominal ornithischian species from Brazil.

Type species

Tietasaura derbyiana sp. nov.

Diagnosis

As for type and only known species, by monotypy.

Tietasaura derbyiana sp. nov.

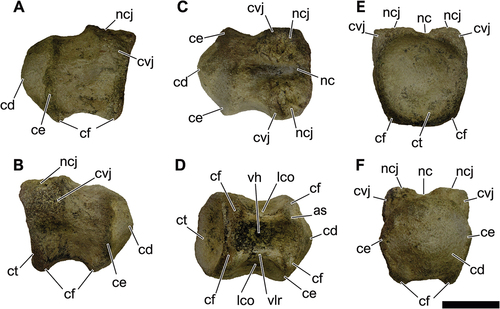

(; Table S3)

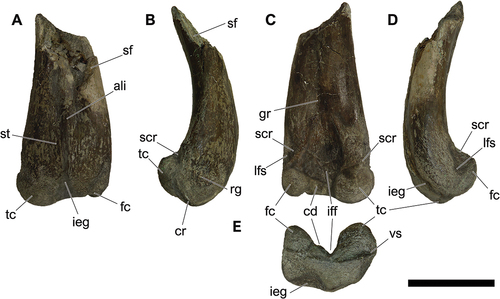

Figure 4. Holotypic distal half of the left femur of Tietasaura derbyiana gen. et. sp. nov. (NHM-PV R.3424) from the Valanginian–Hauterivian Marfim Formation (Ilhas Group) at Plataforma Station (Locality 3). A, anterior; B, medial; C, posterior; D, lateral; E, distal views. Anatomical abbreviations: ali, anterior linea muscularis; cd, condylid process; cr, crest; fc, fibular condyle; gr, groove; ieg, intracondylar extensor groove; iff, intracondylar flexor fossa; lfs, lateral fossa; rg, rugosity; sc, sulcus; sf, spiral fracture; scr, supracondylar ridge; st, striae; tc, tibial condyle. Scale bar = 100 mm.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:52683BA8-C4C5-4A81-90 DB-3BC6431946D2

Etymology

The specific epithet is an eponym honouring Orville A. Derby (1851–1915), founder and the first director from Brazilian Mineralogical and Geological Commission (Serviço Geológico e Mineralógico do Brasil, nowadays SGB), being also the former director of the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro (MN) and one of the pioneers of palaeontology in the Recôncavo Basin. Despite all tragedies in his life and the blatant lack of governmental support, Derby valiantly fought for the scientific progress of the Brazilian geosciences.

Holotype

NHM-PV R.3424, represented by a distal half of a small left femur.

Diagnosis

Small sized elasmarian ornithopod exhibiting an unique combination of character states on the femur (putative autapomorphies marked with an asterisk): presence of a marked anterior linea muscularis followed by several longitudinal striae converging distally towards the intercondylar extensor groove; broad but shallow intercondylar extensor groove; stout supracondylar ridges that extends medially; fibular supracondylar ridge sinuous and bearing a lateral fossa*; hemispherical distal femoral condyles in the posterior view, being the tibial condyle twice as large as fibular condyle; distinct prominent crest in the median margin of the tibial condyle*; fibular condyle with straight lateral margin and continuous in the distal view, lacking an indentation formed by a condyloid (rectangular) process; presence of an offset condylid, medial to the fibular condyle; broad and deep intercondylar flexor fossa, subtriangular in shape and much extending into the diaphysis.

Type locality and horizon

The holotype of Tietasaura derbyiana was recovered at a beach near the Plataforma Station (Locality 3), Salvador City, Bahia State. The shale facies outcropping in this locality are associated with the Valanginian – Hauterivian Marfim Formation (Ilhas Group, Recôncavo Basin).

Description and comparisons

Tietasaura derbyiana comprise a moderately preserved distal end of a small left femur (231.09 mm in preserved length; see Table S3), with less than a half of its total proximodistal length. This specimen was designated as a Hyposaurus sp. in the collection labels of the NHM, a dyrosaurid crocodyliform genus present in the Upper Cretaceous to Early Paleocene strata of North America, North Africa, and Brazil (e.g. Veloso et al. Citation2023). Here, however, we reinterpret it as belonging to an elasmarian ornithopod based on several characteristics (see below). When compared with crocodyliform femora, remarkable anatomical distinctions are observable in Tietasaura derbyiana. In the anterior view, for example, the femur NHM-PV R.3424 exhibits a slightly convex surface towards the distal portion, with the extensor groove more developed on the distal surface than the anterior one. By contrast, in Coelognathosuchia taxa (Goniopholidae+Tethysuchia sensu Martin et al. Citation2014), such as Burkesuchus mallingrandensis (see Novas et al. Citation2021, fig. 5) and Anteophthalmosuchus hooleyi (Martin et al. Citation2016, fig. 16), Hyposaurus rogersii (Pellegrini et al. Citation2021, fig. 1), and an unnamed dyrosaurid from Senegal (Martin et al. Citation2019, fig. 6), the extensor groove is broad and extends proximally in the diaphysis. In the posterior view, Tietasaura derbyiana has a remarkably deep and broad flexor fossa, whereas in coelognathosuchians this region is more restricted, developing as a vertical groove. Additionally, the fibular condyle in coelognathosuchians is much more developed distally than the tibial one, contrasting with the inverse pattern observed in Tietasaura derbyiana. Finally, in the distal view, the femoral epiphysis of Tietasaura derbyiana is wider mediolaterally, while in crocodyliform femora it develops anteroposteriorly.

Although the bone exhibits signs of pre-burial transportation, its surface is well preserved, and the periosteum preserves several muscular striae and rugosities. Moreover, the diaphysis in Tietasaura derbyiana shows a spiral fracture () typical of fresh bone breakage (e.g. Galloway Citation1999). In the median portion of the diaphyseal surface, the periosteum is well-preserved and particularly smooth. This feature could be interpreted as an indicator of osteological maturity, contrasting with the long-grained or dimpled patterns seen in immature specimens of pterosaurs (Bennett Citation1993), ceratopsians (Tumarkin‐Deratzian Citation2009), and birds (Tumarkin-Deratzian et al. Citation2006). Comparing with other dinosauromorphs, the bone cortex thickness in NHM-PV R.3424 further indicates that the individual reached its asymptotic mass (Sander and Tückmantel Citation2003; Griffin et al. Citation2019). However, due to the unavailability of paleohistological or CT-scan data for this individual, a precise ontogenetic assessment for Tietasaura derbyiana cannot be assumed. Therefore, such inferences are considered tentative and should be approached with caution (see Griffin et al. Citation2021 for an overview).

The diaphysis, as preserved, is swelled towards the distal end surface in anterior and posterior views (). In the lateral and medial views, the preserved shaft exhibits an accentuated posterior curvature, indicating a sigmoid profile for the femur (). This feature is widely distributed, being present in some early-diverging ornithischians, such as Eocursor parvus Butler et al. Citation2007 and Pisanosaurus mertii Casamiquela Citation1967 (see Butler Citation2010; Agnolín and Rozadilla Citation2018), thescelosaurids (Gilmore Citation1915; Scheetz Citation1999; Boyd et al. Citation2009; Brown et al. Citation2011, Citation2013), and some elasmarians, such as Anabisetia saldiviai Coria and Calvo Citation2002.

The anterior surface in Tietasaura derbyiana is almost planar, except for a shallow ‘V-shaped’ intercondylar extensor groove that does not reach the fibular and tibial condyles in the distal view (). This condition differs from the condition observed in most theropods, in which this region presents a deep and elongated groove (Carrano et al. Citation2012). This condition resembles the morphology found in thescelosaurids and ornithopods (e.g. Krumenacker Citation2017; Madzia et al. Citation2018). In addition, the anterior surface exhibits remarkable anterior linea intermuscularis and several striae, which could be associated with M. femorotibialis. Both condyles are visible in the anterior view, being the tibial more bevelled and extending further distally than the fibular one, but not reaching the diaphyseal portion of the distal end ().

In the posterior view (), the tibial condyle is much larger than the fibular one, but both are broad and hemispherical in shape. In lateral and medial views (), a pair of prominent supracondylar ridges are present, enclosing a fully opened, deep posterior intercondylar flexor fossa. This fossa is vertically developed and tapers towards the diaphysis acquiring a ‘V-shaped’ aspect. In the fibular condyle, the supracondylar ridge acquires a sinuous profile in the posterior view (). In contrast, the supracondylar ridge is confluent and merges with the condyle in the lateral view (). The tibial condyle is slightly oblique, posteromedially inclined, with a round lateral aspect. In distal view (), the fibular condyle has a straight and continuous lateral margin, lacking an indentation that detaches a condyloid process parasagittal to the femoral shaft (–G). In contrast, medially to the fibular condyle, a small accessory condylid is present, as in Notohypsilophodon comodorensis Martínez Citation1998 ().

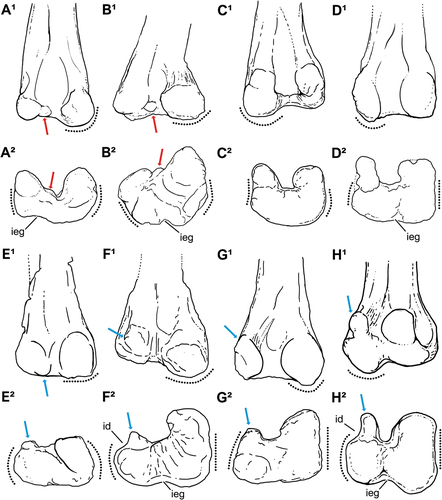

Figure 5. Schematic draw comparing selected elasmarian femora in (1) posterior and (2) distal views. A, Tietasaura derbyiana gen. et. sp. nov. (NHM-PV R.3424); B, Notohypsilophodon comodorensis (UNPSJB-Pv 942); C, Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis (MUCPv-208); D, Fulgurotherium australe (NHM-PV R.3719); E, Trinisaura santamartensis (MLP 08-III-1-1); F, Morrosaurus antarcticus (MACN-Pv 197); G, Isasicursor santacrucensis (MPM 21,533); H, Anabisetia saldiviai (MCF-PVPH 74). Red arrows exhibit the taxa that exhibits a distinct condylid processes between the condyles, while the blue arrows indicate the development and shifting of the condyloid (‘rectangular’) processes. Dotted lines highlight different patterns on general shape (convex or almost rectilinear) and condyle development of femoral surfaces in the posterior (1) and distal (2) views. Anatomical abbreviations: id, indentation; ieg, intracondylar extensor groove. Without scale for comparative purposes.

In lateral view, the strongly sigmoidal shaft of Tietasaura derbyiana differs from the condition seen in Hypsilophodon foxii Huxley Citation1870, some elasmarians (e.g. Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis Coria and Salgado Citation1996a, Talenkauen santacrucensis Novas et al. Citation2004, iguanodontians, and theropods, such as noasaurids and maniraptorans, in which the femora display relatively straighter profiles (e.g. Hulke Citation1882; Madzia et al. Citation2018; Rozadilla et al. Citation2019). However, it is remarkable that the femur shaft is slightly sigmoid in perinate specimens of Iguanodon galvensis Verdú et al. Citation2015 but acquires a fully straight profile through its ontogenetic development.

Compared with theropods, the new species lacks any sign of an anteromedial crest (Carrano and Sampson Citation2008). The fibular supracondylar crest confluent with the condyle also contrasts with what is observed in theropods, in which this crest is posteriorly projected and detached from this condyle (e.g. Carrano Citation2007; Gianechini and Apesteguia Citation2011; Egli et al. Citation2016; Rauhut and Carrano Citation2016; Novas et al. Citation2018). In paravians, excepting dromaeosaurids, the articular regions are separated by a deep groove, forming a trochlea-like articular surface in distal view (Baumel and Witmer Citation1993; Chiappe Citation1996; Norell and Makovicky Citation1997; Forster et al. Citation1998).

The mostly planar anterior surface of Tietasaura derbyiana further differs from the condition observed in most theropods, in which this region presents a deep and elongated anterior intercondylar groove (Carrano et al. Citation2012). In this respect, Tietasaura derbyiana is similar to the morphology found in thescelosaurids and ornithopods (e.g. Krumenacker Citation2017).

Tietasaura derbyiana differs from iguanodontians in lacking a medially inflated medial condyle that partially covers the posterior intercondylar groove (e.g. Madzia et al. Citation2018). It also differs from most ornithopods in lack of mediolaterally compressed distal condyles in the posterior view. As in elasmarians, the condyles in Tietasaura derbyiana are often subcircular, as seen in Kangnasaurus coetzeei Haughton Citation1915 (Cooper Citation1985), Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis, Anabisetia saldiviai, Trinisaura santamartaensis Coria et al. Citation2013, Notophysilophodon comodoriensis, and Morrosaurus antarcticus Rozadilla et al. Citation2016.

Tietasaura derbyiana is further distinguished from most neornithischians by the absence of an indentation on the posterolateral edge of the femur in distal view, between the main corpus of the fibular condyle and the condyloid (or rectangular) process, as seen in iguanodontians (e.g. Galton Citation1977; Forster Citation1990; Bertozzo et al. Citation2017; Maidment et al. Citation2022), Burianosaurus augustai Madzia et al. Citation2018, some elasmarians such as Kangnasaurus coetzeei, Anabisetia saldiviai, Trinisaura santamartaensis, and Morrosaurus antarcticus, thescelosaurids (e.g. Barta and Norell Citation2021; Sues et al. Citation2023), and, although quite gentle, basal marginocephalians (e.g. Butler and Zhao Citation2009; Han et al. Citation2018). Tietasaura derbyiana lacks this indentation (thus lacking a distinct rectangular/condyloid process) and thus exhibits a straight medial edge of the fibular condyle in distal view. In this respect, Tietasaura derbyiana is like some elasmarians, such as Fulgurotherium australe Huene von Citation1932 (e.g. Molnar and Galton Citation1986), Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis, Notohypsilophodon comodoriensis, Isasicursor santacrucensis Novas et al. Citation2019, and the Victorian femur type I (Rich and Rich Citation1989). Within elasmarians, Tietasaura derbyiana resembles Notohypsilophodon comodorensis in the conspicuously sharp posterior supracondylar ridges (Ibiricu et al. Citation2010), as well as the presence of a condylid between both condyles. The fibular condyle of Tietasaura derbyiana is also strikingly like that of Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis, roughly in the shape of a rectangular triangle with a slightly rounded medial edge in the distal view.

Ornithopoda Marsh Citation1881

Iguanodontia Baur Citation1891

Ankylopollexia Sereno Citation1986

Styracosterna Sereno Citation1986

Gen. et sp. indet.

Specimen A

Referred material

NHM-PV R.3425, represented by an isolated middle dorsal centrum (; Table S2).

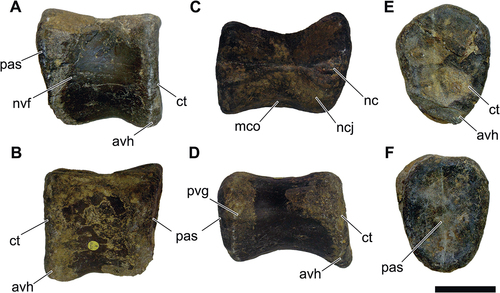

Figure 6. NHM-PV R.3425, isolated middle dorsal centrum with iguanodontian affinities (Specimen A) from the Valanginian–Hauterivian Marfim Formation (Ilhas Group) at Plataforma Station (Locality 3). A, right lateral; B, left lateral; C, dorsal; D, ventral; E, anterior; F, posterior views. Anatomical abbreviations: avh, anteroventral heel; ct, cotyle; nvf, neurovascular foramina; mco, median concavity; ncj, neurocentral joint; pas, posterior articulation surface; pvg, posteroventral groove. Scale bar = 100 mm.

Locality and horizon

In contrast to the other materials studied here, the collection label of NHM-PV R.3425 only contains the description ‘Cretaceous. Bahia, Brazil’. in the provenance data, hindering major details about the exact locality that the specimen came. Nonetheless, according to the site descriptions provided by Mawson and Woodward (Citation1907), we can safely ascribe this specimen to the Ilhas Group (Valanginian – Barremian). The specimen NHM-PV R.3425 might have been recovered from some outcrop at the beach near the Plataforma Station (Locality 3; see ), based on taphonomical features of the specimen, such as the colour and the abrasion degree. The year in which this specimen was collected (1906) also supports this assumption, wherein only three other similar materials were reported from this locality.

Description and comparisons

NHM-PV R.3425 is referred to a middle dorsal centrum given the absence of articular facets of chevrons. The centrum is dorsoventrally taller than anteroposteriorly long, as in some middle dorsal centra of Iguanodon bernissartensis Boulenger Citation1881, Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis (Hooley Citation1925), Hippodraco scutodens, Iguanacolossus fortis McDonald et al. Citation2010, and Morelladon beltrani Gasulla et al. Citation2015 (see Norman Citation1980, Citation1986; McDonald et al. Citation2012). Both anterodorsal and anteroventral corners of the anterior articular surface surpass the posteroventral one (). In addition, the anteroventral expansion creates a rounded anteroventral heel that is slightly deflected anteriorly. The centrum exhibits an opisthoplatyan intercentral articulation, bearing a gently concave anterior surface and an almost flat posterior surface that exhibits ellipsoid outlines (). Signals of lateral striations circumscribing the articular surfaces are absent but could correspond to a taphonomic artefact since this facet is well abraded. In the lateral view, the posterior articular surface displays subparallel margins, which slightly diverges dorsally. The lateral surfaces of NHM-PV R.3425 exhibit a series of small neurovascular foramina, mainly on the right surface. A marked neurocentral joint is observable on the dorsal surface, indicating that NHM-PV R.3425 could correspond to an immature individual (). The ventral margin is gently concave in lateral view (). A marked posteroventral groove is present ventrally, lacking crests or ridges ().

The centrum is slightly constricted medially and has an ‘hourglass shape’ in both dorsal and ventral views (), which is the typical morphology observed in ornithischian dorsal centra (e.g. Norman et al. Citation2004a). NHM-PV R.3425 differs from thyreophorans (e.g. Raven et al. Citation2020; Breeden et al. Citation2021) and marginocephalians (e.g. Butler and Zhao Citation2009) in exhibiting taller than wide articular centra, with a posteroventral margin deeper than the anteroventral one in lateral view. These features ally NHM-PV R.3425 to some iguanodontian ornithopods, such as Iguanodon bernissartensis Boulenger Citation1881, Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis (Hooley Citation1925), Hippodraco scutodens McDonald et al. Citation2010, and Iguanacolossus fortis McDonald et al. Citation2010. Another typical ornithopod feature that can be seen in NHM-PV R.3425 corresponds to a series of small neurovascular foramina on the lateral surface of the centra, like what is seen in elasmarians (e.g. Calvo et al. Citation2007; Rozadilla et al. Citation2019), Sektensaurus sanjuanboscoi Ibiricu et al. Citation2019, and iguanodontians (e.g. Wang et al. Citation2010), including hadrosaurids (e.g. Cruzado-Caballero Citation2017).

The lack of the median ventral keel in NHM-PV R.3425 differ it from the middle dorsal centra of several ornithischians such as Hypsilophodon foxii (see Hulke Citation1882), Psittacosaurus mongoliensis (Osborn Citation1923) (see Sereno and Chao Citation1988; Averianov et al. Citation2006), thescelosaurids (including ‘jeholosaurids’, with exception of Orodromeus), such as Changchunsaurus parvus Zan et al. Citation2005, Jeholosaurus shangyuanensis Xu et al. Citation2000, Yueosaurus tiantaiensis Zheng et al. Citation2012 (Scheetz Citation1999; Butler et al. Citation2011; Han et al. Citation2012). This further differs from some elasmarians, such as Mahuidacursor lipanglef Cruzado-Caballero et al. Citation2019 and Macrogryphosaurus gondwanicus (see Rozadilla et al. Citation2019), even though this feature is also absent in other elasmarians, such as Trinisaura santamartaensis and Notohypsilophodon comodoriensis (Coria et al. Citation2013; Ibiricu et al. Citation2014).

The absence of a median ventral keel is also observed in the unnamed ornithopod from the Bajo de la Carpa Formation (MAU-Pv-LE-617; Jiménez Gomis et al. Citation2018), non-hadrosauriform dryomorphans (e.g. Tenontosaurus tilletti Ostrom Citation1970), dryosaurids, and ankylopollexians, such as Camptosaurus dispar (Marsh Citation1879), Cumnoria prestwichii (Hulke Citation1880), Hippodraco scutodens, Iguanacolossus fortis, and Dakotadon lakotaensis Weishampel and Björk Citation1989 (e.g. Gilmore Citation1909; Galton Citation1981; Forster Citation1990; McDonald et al. Citation2010). Rhabdodontomorphs, such as Zalmoxes robustus (Nopcsa Citation1900) and Mochlodon suessi (Bunzel Citation1871) (see Godefroit et al. Citation2009; Ősi et al. Citation2012), exhibit a reduction of the ventral keel, showcasing an evolutionary tendency to diminish in non-hadrosauriform iguanodontians. Hadrosauriformes demonstrate, conversely, a secondary development of a ventral keel, as evidenced in Iguanodon bernissartensis, Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis, Morelladon beltrani Gasulla et al. Citation2015, Ouranosaurus nigeriensis Taquet Citation1972, and various hadrosaurids (e.g. Hooley Citation1925; Gasca et al. Citation2015; Verdú et al. Citation2015). In this regard, NHM-PV R.3425 shares more similarities with non-hadrosauriform dryomorphans.

Notably, NHM-PV R.3425 shares with the middle dorsal centra of some basal ankylopollexians asymmetrical ventral margins in the lateral view, with a shallower anteroventral heel compared to the deeper posteroventral one. This configuration is observed in the middle dorsal centra of the non-hadrosauriform ankylopollexians Cumnoria prestwichii (Maidment et al. Citation2022), Camptosaurus dispar (Gilmore Citation1909), Uteodon aphanoecetes (Carpenter and Wilson Citation2008), and Hippodraco scutodens (McDonald et al. Citation2010). This trait is also present in Sektensaurus sanjuanboscoi, initially interpreted as an indeterminate ornithopod (either elasmarian or iguanodontian; see Ibiricu et al. Citation2019) and recognised here as a non-hadrosauriform styracosternan (see further below).

Additionally, this feature is absent in thyreophorans (e.g. Norman et al. Citation2004b; Raven et al. Citation2020; Breeden et al. Citation2021), elasmarians (e.g. Novas et al. Citation2019; Cruzado-Caballero et al. Citation2019; Rozadilla et al. Citation2019, 2020), the indeterminate ornithopod MAU-Pv-LE-617 (Jiménez Gomis et al. Citation2018), dryosaurids (Galton Citation1981; Barrett Citation2016), Tenontosaurus tilleti Ostrom Citation1970, rhabdodontids (Godefroit et al. Citation2009; Ősi et al. Citation2012), Hypsilophodon foxii (Hulke Citation1882), and more advanced styracosternans, such as Iguanacolossus fortis, Lanzhousaurus magnidens You et al. Citation2005, Barilium dawsoni (Lydekker Citation1888; Norman Citation2011), Hypselospinus fittoni (Lydekker Citation1889; Norman Citation2010), Morelladon beltrani, Iguanodon bernissartenis (Norman Citation1980), Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis Hooley Citation1925 (Norman Citation1986), Ouranosaurus nigeriensis (Bertozzo et al. Citation2017), Equijubus normani You et al. Citation2003, and Probactrosaurus gobiensis (Rozhdestvensky Citation1966). Hence, NHM-PV R.3425 exhibits similarities with some basal ankylopollexians like Camptosaurus dispar, Cumnoria prestwichii, Uteodon aphanoecetes, Hippodraco scutodens, and Sektensaurus sanjuanboscoi (Gilmore Citation1909; Carpenter and Wilson Citation2008; McDonald et al. Citation2010; Ibiricu et al. Citation2019; Maidment et al. Citation2022).

NHM-PV R.3425 further differs from the dorsal centra of most ornithischians given that it bears taller than wide, ellipsoid articular outlines. In this respect, it differs from the wider than taller, or as wide as high, articular surfaces found in the dorsal centra of thyreophorans (e.g. Norman et al. Citation2004b; Raven et al. Citation2020; Breeden et al. Citation2021), marginocephalians (e.g. Butler and Zhao Citation2009), rhabdodontomorphs (Godefroit et al. Citation2009; Ősi et al. Citation2012), Tenontosaurus tilleti (Forster Citation1990), and dryosaurids (Galton Citation1981; Barrett Citation2016). The same is true for some elasmarians, such as Talenkauen santacrucensis (see Rozadilla et al. Citation2019), Mahuidacursor lipanglef (see Cruzado-Caballero et al. Citation2019), and Macrogryphosaurus gondwanicus (see Rozadilla et al. Citation2020), even though other elasmarians show similarly higher than wide dorsal centra, such as Isasicursor santacrucensis (which still differs from NHM-PV R.3425 in exhibiting a ventral groove; see Novas et al. Citation2019). Like Isasicursor santacrucensis, the dorsal centrum of the indeterminate ornithopod MAU-Pv-LE-617 also resembles NHM-PV R.3425 in being higher than wide, and distinct in bearing a ventral groove (Jiménez Gomis et al. Citation2018). This morphology also differs from what is seen in the basal ankylopollexians Camptosaurus dispar Marsh Citation1879 and Uteodon aphanoecetes (Carpenter and Wilson Citation2008) but matches with an array of some non-hadrosauroid ankylopollexians middle dorsal centra. This feature is absent in hadrosauriforms, such as Ouranosaurus nigeriensis (see Bertozzo et al. Citation2017) and Eolambia caroljonesa Kirkland Citation1998 (McDonald et al. Citation2012). NHM-PV R.3425 further resembles Hippodraco scutodens in the flushed dorsal edge of the posterior articular surface relative to the anterior articular surface.

In summary, NHM-PV R.3425 resembles the middle dorsal vertebrae of non-hadrosauriform ankylopollexians due to the following combination of characters: centrum being subequal in length and height; higher than wide, ellipsoid articular outlines; concave ventral margin in lateral view, with the posterior ventral projection deeper than the posterior one; and ventral surface lacking a pronounced keel or ridge. Based on this combination of features, we regard that NHM-PV R.3425 most closely resembles Cumnoria prestwichii, Hippodraco scutodens, and Sektensaurus sanjuanboscoi. In particular, NHM-PV R.3425 is most similar to the styracosternan Hippodraco scutodens due to the articular surfaces not being parallel in lateral view.

Specimen B

Referred material

NHM-PV R.2459, a nearly preserved middle to posterior dorsal centrum (; Table S2).

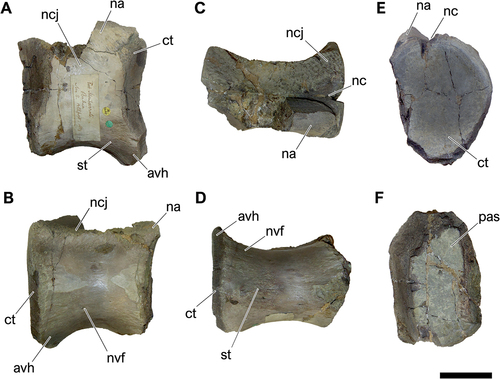

Figure 7. NHM-PV R.2459, isolated middle to posterior dorsal centrum with iguanodontian affinities (Specimen B) from the Valanginian–Hauterivian Marfim Formation (Ilhas Group) at Forte Monte Serrat (Locality 2). A, right lateral; B, left lateral; C, dorsal; D, ventral; E, anterior; F, posterior views. Anatomical abbreviations: avh, anteroventral heel; ct, cotyle; nvf, neurovascular foramina; na, neural arch; nc, neural canal; ncj, neurocentral joint; pas, posterior articulation surface; st, striae. Scale bar = 100 mm.

Locality and horizon

The specimen NHM-PV R.2459 was recovered from sandy shale facies at the Forte Montserrat (Locality 2), which is located close to the beaches of Pedra Furada Bay, Salvador City, Bahia State. The rock layers in this locality are associated with the Ilhas Group, based on the faciological characterisation provided by Allport (Citation1860), and correspond to the level of the Valanginian – Hauterivian Marfim Formation.

Description and comparisons

NHM-PV R.2459 is an isolated dorsal centrum and, as in several bones studied here, presents a certain degree of weathering. The centrum is taller than wider, being taller than NHM-PV R.3425, and has an opisthoplatyan intercentral articulation. The centrum exhibits well-defined longitudinal striations circumscribing the articular surfaces (), as well as presents numerous lateral neurovascular foramina as in NHM-PV R.3425. The anterior articular surface has a subcircular to oval outline (). In addition, the anterior articular face, as preserved, is slightly transversely wider than the posterior one (), defining a wedge-shape in lateral and ventral views () – a common feature among ornithopods (e.g. Norman et al. Citation2004a). The ventral margin is strongly concave in lateral view, showing an offset between the anterior and posterior faces, with the anteroventral heel projecting further ventrally than the posteroventral one, as in NHM-PV R.3425. The lateral and ventral surfaces of the centrum bear several small neurovascular foramina. The absence of a neural arch hinders refined comparisons regarding the position of this element along the dorsal series.

The specimen NHM-PV R.2459 has already been referred as a dorsal centrum of the tetanuran Megalosaurus by Owen (in Allport Citation1860) and after attributed as a probable material of the pholidosaurid Sarcosuchus hartti by Buffetaut and Taquet (Citation1977). However, NHM-PV R.2459 differs substantially from theropods due to the lack of external and internal pneumatic traits, such as pneumatopores, as usual in presacral elements for Theropoda (e.g. Benson et al. Citation2012). This specimen also differs from pholidosaurids, as well as several other crocodyliforms, given their taller centra, opisthoplatyan intercentral articulations, and the lack of hypapophysis (Souza Citation2019).

As with NHM-PV R.3425 (see above), this specimen notably resembles the morphology of non-hadrosauriform ankylopollexians, such as Cumnoria prestwichii, Hippodraco scutodens, and Sektensaurus sanjuanboscoi, due to the lack of either a ventral keel or groove, strong concave ventral margin in lateral view (with the anterior ventral projection deeper than the anterior one; ellipsoid to suboval articular surfaces, and the centrum being subequal in length and height. Like NHM-PV R.3425 and Hippodraco scutodens, NHM-PV R.2459 also exhibits articular surfaces that are not parallel in lateral view.

Specimen C

Referred material

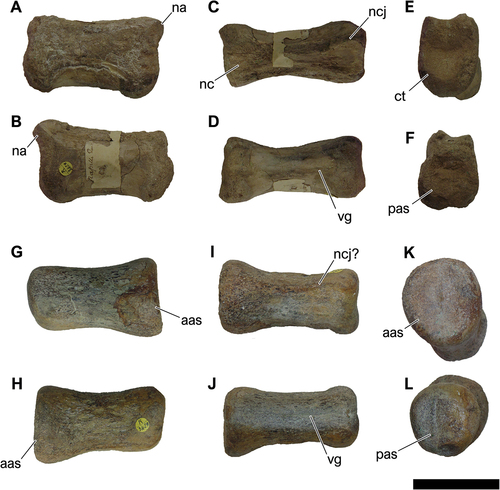

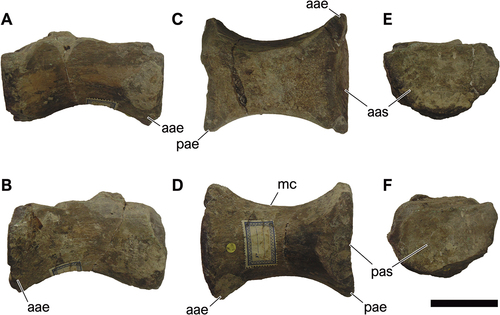

NHM-PV R.3426, represented by a fragmentary middle caudal centrum; NHM-PV R.3428(a) and NHM-PV R.3428(b), composed of two posterior caudal centra, which might belong to the same individual. (; Table S2).

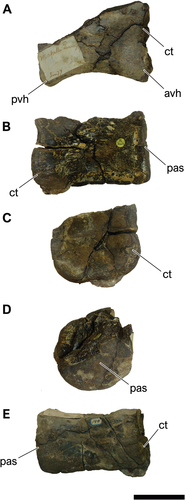

Figure 8. NHM-PV R.3426, middle caudal centrum with iguanodontian affinities (Specimen C) from the Berriasian–Barremian Salvador Formation (Massacará Group) at Mapelle Quarry (Locality 9). A, right lateral; B, left lateral; C, anterior; D, posterior; E, ventral views. Anatomical abbreviations: avh, anteroventral heel; ct, cotyle; pas, posterior articulation surface; pvh, posteroventral heel. Scale bar = 100 mm.

Figure 9. NHM-PV R.3428(a) and NHM-PV R.3428(b), associated middle to posterior caudal centra with iguanodontian affinities (specimen C) from the Berriasian–Barremian Salvador Formation (Massacará Group) at Mapelle Quarry (Locality 9). A-G, right lateral; B-H, left lateral; C-I, dorsal; D-J, ventral; E-K, anterior; F-L, posterior views. Anatomical abbreviations: aas, anterior articulation surface; ct, cotyle; na, neural arch; nc, neural canal; ncj, neurocentral joint; pas, posterior articulation surface; vg, ventral groove. Scale bar = 100 mm.

Locality and horizon

The three elements were recovered at the Mapelle Quarry (Locality 8). In this locality outcrops flagstones and conglomeratic sandstones of the Salvador Formation (Massacará Group), which is partially synchronous with the Ilhas Group, ranging from the Berriasian to Barremian time-interval.

Description and comparisons

NHM-PV R.3426 is an isolated partial opisthoplatyan centrum with unpreserved neural arch (). The centrum is approximately rectangular, with only a faint middle constriction, but does not produce an accentuated wedge shape (). The ventral margin, although damaged, seems almost flat (). It is identified here as a middle caudal centrum due to its moderate elongation, only slightly longer than tall, as seen in non-hadrosauriform styracosternan middle-to-posterior caudal centra (e.g. Norman Citation1980; McDonald et al. Citation2012). It is interesting to note that the anterior articular surface is quadrangular, like the single known anterior caudal centrum of the holotype of Iguanacolossus fortis (see McDonald et al. Citation2010). Such configuration cannot be found in the other well-known iguanodontian caudal elements, such as those of Valdosaurus canaliculatus Galton Citation1975 (Barrett Citation2016), Tenontosaurus tilletti (Forster Citation1990), Cumnoria prestwichii (Maidment et al. Citation2022), Hypselospinus fittoni (Norman Citation2011), and Ouranosaurus nigeriensis (Bertozzo et al. Citation2017). This can also not be found in other known elasmarian caudal centra (Novas et al. Citation2019; Rozadilla et al. Citation2020), nor in other indeterminate South American ornithopods (Rubilar-Rogers et al. Citation2013; Cruzado-Caballero Citation2017).

The elements NHM-PV R.3428(a) and R.3428(b) are anteroposteriorly elongated and slightly dorsoventrally taller than transversally wide. The element ‘a’ () is better preserved than the element ‘b’ (), which is very abraded, and both are apneumatic. In lateral view, the ventral margins of the centra are slightly concave (). Ventrally, the element ‘a’ also present a shallow longitudinal groove (). The intercentral articulation varies from a slightly platycoelous () to amphyplatyan ().

The specimen NHM-PV R.3426 exhibit a general quadrangular centrum shape, differing from the middle to posterior caudal centra of most ornithopods which, although the high of varying shapes, usually exhibit articular surfaces approximately subequal in width and height, as seen in elasmarians (e.g. Coria and Salgado Citation1996a; Novas et al. Citation2019; Rozadilla et al. Citation2019), rhabdodontomorphs (e.g. Weishampel et al. Citation2003; Ősi et al. Citation2012), Tenontosaurus (e.g. Forster Citation1990), dryosaurids (e.g. Barrett Citation2016), and iguanodontians such as Cumnoria prestwichii (Maidment et al. Citation2022), Camptosaurus dispar, Uteodon aphanoecetes (Carpenter and Wilson Citation2008), and Sektensaurus sanjuanboscoi (Ibiricu et al. Citation2014). By exhibiting taller than wide and quadrangular to subcircular articular surfaces, the Salvador Formation caudal centra are similar to some styracosternans such as Iguanacolossus fortis (McDonald et al. Citation2010), Iguanodon bernissartensis (Norman Citation1980), Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis (Norman Citation1986), Ouranosaurus nigeriensis (at least the middle elements; Bertozzo et al. Citation2017), and the El Castellar iguanodont (García-Cobeña et al. Citation2023). In this respect, it also resembles the indeterminate ornithopod from Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Cruzado-Caballero Citation2017).

However, the Salvador Formation distal caudal centra lack the hexagonal shape seen in the articular surfaces found in many ankylopollexians, such as Cumnoria prestwichii, Hypselospinus fittoni, Iguanodon bernissartensis, Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis, and Ouranosaurus nigeriensis. It also differs from the middle and distal caudal centra of elasmarians, such as Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis, Talenkauen santacrucensis, and Isasicursor santacrucensis, in which the articular surfaces are circular and wider than higher (Coria and Salgado, Citation1996a; Rozadilla et al. Citation2019; Novas et al. Citation2019). Instead, the articular surfaces of the distal caudal centra of the Salvador Formation form are closer to the higher than wide centra with subcircular shape seen in the basal styracosternan Iguanacolossus fortis, the El Castellar iguanodontian (García-Cobeña et al. Citation2023), and the Bajo de la Carpa Formation ornithopod (Cruzado-Caballero Citation2017).

Summarising, the middle caudal NHM-PV R.3426 differs from most ornithopods, except for Iguanacolossus fortis, in exhibiting a quadrangular articular surface (McDonald et al. Citation2010). The distal centra in NHM-PV R.3428 exhibits a combination of higher than wide articular surfaces, an opisthoplatyan condition, mild concave ventral margin in lateral view, presence of a lateral horizontal ridge, and presence of a slightly ventral groove. This synapomorphic combination of characters matches with the morphology seen in the posterior caudal centra of other styracosternans, such as Iguanacolossus fortis and the El Castellar iguanodontian, and resembles the Bajo de la Carpa Formation ornithopod as well (Cruzado-Caballero and Powell Citation2017). This is consistent with the presence of non-hadrosauriform styracosternans in the Recôncavo Basin assemblage as already indicated by the dorsal centra NHM-PV R.3425 and NHM-PV R.2459.

Specimen D

Referred material

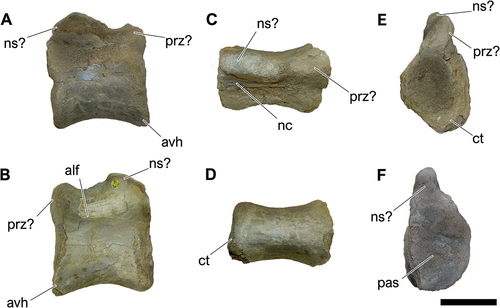

NHM-PV R.3429, a middle caudal vertebra (; Table S2).

Figure 10. NHM-PV R.3429, isolated middle caudal vertebra with iguanodontian affinities (Specimen D) from the Valanginian–Hauterivian Marfim Formation (Ilhas Group) at Plataforma Station (Locality 3). A, right lateral; B, left lateral; C, dorsal; D, ventral; E, anterior; F, posterior views. Anatomical abbreviations: alf, anterolateral fossa; avh, anteroventral heel; ct, cotyle; ns, neural spine; pas, posterior articulation surface; prz, prezygapophysis. Scale bar = 100 mm.

Locality and horizons

The NHM-PV R.3429 specimen was found at the beach near Plataforma Station (Locality 3). The shale facies outcropping in this locality are associated with the Valanginian – Hauterivian Marfim Formation (Ilhas Group, Recôncavo Basin).

Description and comparisons

NHM-PV R.3429 is an incomplete vertebra, comprised by most of the centrum and part of the pedicel of the neural arch (). It is interpreted as a caudal due to the lack of a transverse process, and as a middle caudal due to its moderate elongation (about as wide as tall) and the lack of articular facets for chevrons. The intercentral articulation is platycoelous with subcircular, higher than wide articular surfaces (). The vertebra is apneumatic, and the neural arch covers entire the dorsal extension of the centrum (). The ventral surface is smooth, lacking keels or grooves (). In these respects, this element closely resembles for the middle caudal vertebrae of several ankylopollexians, such as Cumnoria prestwichii, Hypselospinus fittoni, Iguanodon bernissartensis, and Ouranosaurus nigeriensis. It differs from early-diverging iguanodontians, such as rhabdodontomorphs (Ősi et al. Citation2012) and dryosaurids (e.g. Galton Citation1981), which tend to exhibit mid caudal articular surfaces about as wide as high. It also differs from theropods and sauropods for being taller than wide, while in those saurischians the reverse is more common (Weishampel et al. Citation2003).

NHM-PV R.3429 differs from crocodylomorphs, such as notosuchians and other mesoeucrocodylians, due to the ventral offset presented and the absence of hypapophyses (e.g. Leardi et al. Citation2015). It is notorious that, in general pattern, this specimen closely matches with the other Marfim Formation iguanodontian material (NHM-PV R.2459 and R.3425), except for the lack of an asymmetrical ventral margin of the centrum in lateral view (). Given the morphology of this specimen is consistent with ankylopollexians and closely matches the general morphology, we regard that these specimens possibly represent the same taxon.

Saurischia Seeley Citation1888

Sauropoda Marsh Citation1878

Neosauropoda Bonaparte Citation1986

Diplodocoidea Marsh Citation1884

Diplodocidae Marsh Citation1884

Gen. et sp. indet.

Specimen A

Referred material

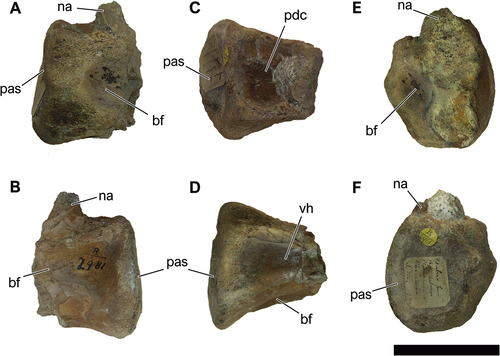

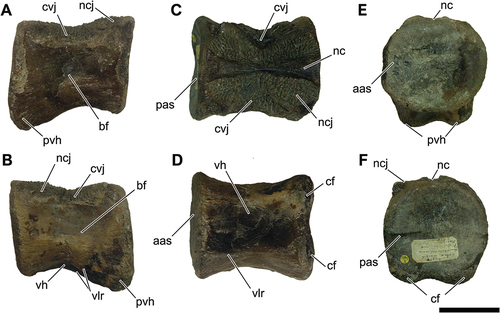

NHM-PV R.2981(b), a posterior end of a distal middle or proximal posterior caudal centrum, with a minor portion of the neural arch (; Table S2).

Figure 11. NHM-PV R.2981(b), fragment of a distal middle or proximal posterior caudal centrum with diplodocid affinities (Specimen A) from the Valanginian–Hauterivian Marfim Formation (Ilhas Group) at beach between Plataforma and Itacaranha (Locality 4). A, right lateral; B, left lateral; C, dorsal; D, ventral; E, anterior; F, posterior views. Anatomical abbreviations: bf, blind fossa; na, neural arch; pdc, posterodorsal concavity; pas, posterior articulation surface; pdc, posterodorsal concavity; vh, ventral hollow. Scale bar = 100 mm.

Locality and horizon

NHM-PV R.2981(b) comes from beach outcrops between Plataforma Station and Itacaranha (Locality 4), Pedra Furada Bay, and was recovered in the fossiliferous shale intercalated with sandstone lenses associated, here associated with the Valanginian – Hauterivian Marfim Formation.

Description and comparisons

NHM-PV R.2981(b) is represented by an incomplete centrum lacking most of its anterior portion. However, based on the posterior surface suggests that it might be platycoelous (). Part of the periosteum suffered some abrasion produced by sedimentary particles against the bone and possibly due to some degree of reworking of the carcass before the final burial (e.g. Shipman Citation1981). The specimen NHM-PV R.2981(b) exhibits strongly concave lateral surfaces (), as in the rebbachisaurids Amanzosaurus maranhensis Carvalho et al. Citation2003, Limaysaurus tessonei Calvo and Salgado Citation1995, and Itapeuasaurus cajapioensis Lindoso et al. Citation2019. In the anterior view, the centrum is strongly compressed medially and forms an 8-shaped outline, most by the development of deep blind fossae (). Nonetheless, any sign of internal pneumaticity on bone tissue is observable. In addition, there is no signal of an anteroposteriorly oriented ridge in NHM-PV R.2981(b), differing from the observed in UNPSJB-PV 1004/3, Dicraeosaurus hansemanni Janensch Citation1914 and Suuwassea emiliae Harris and Dodson Citation2004 (Harris Citation2006; Ibiricu et al. Citation2012). In the dorsal view (), a shallow but relatively broad posterodorsal concavity is present, which is not seen in other diplodocoids (e.g. Tschopp et al. Citation2015). Ventrally, NHM-PV R.2981(b) bears a markedly well-developed hollow that extends longitudinally (), as in NHM-PV R.3427 (see below), UNPSJB-PV 1004/3, and Tornieria africana Fraas 1908 (Remes Citation2006).

In the posterior view (), the centrum is dorsoventrally elongated like other diplodocids (see ), such as Apatosaurus ajax Marsh Citation1877, Brontosaurus parvus Peterson and Gilmore Citation1902, and Galeamopus hayi (Holland Citation1924), but less than middle to posterior caudal vertebrae of the rebbachisaurid Demandasaurus darwini Fernández-Baldor et al. Citation2011. This condition contrasts with the dorsoventrally compressed caudal centra of Amazonsaurus maranhensis and other rebbachisaurids, which are more similar to those observed in flagellicaudatans. The posterior articular face in NHM-PV R.2981(b) exhibits a roughly circular outline with flat ventral margin (), like Barosaurus lentus Marsh Citation1890 and Suuwassea emiliae, differing from the trapezoidal outlines seen in Amazonsaurus maranhensis, the unnamed rebbachisaurids from Cajual island (UFMA 1.10.015, UFMA 1.10.168, UFMA 1.10.188, and UFMA 1.10.806; see Medeiros and Schultz Citation2004), and Limaysaurus tessonei Calvo and Salgado Citation1995 (Salgado et al. Citation2004). In addition, NHM-PV R.2981(b) displays prominent dorsolateral expansions, but less developed than in the titanosaurian Mnyamawamtuka moyowamkia Gorscak et al. Citation2019.

Table 2. Caudal centrum ratios (width-to-height, length-to-height) for selected sauropod taxa (Modified from Tschopp et al. Citation2015: table S39).

Specimen B

Referred material

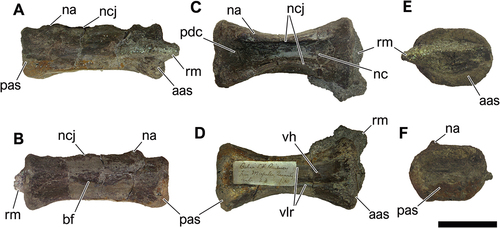

NHM-PV R.3427, represented by a posterior caudal centrum (; Table S2).

Figure 12. NHM-PV R.3427, isolated posterior caudal centrum with diplodocid affinities (Specimen B) from the Berriasian–Barremian Salvador Formation (Massacará Group) at Mapelle Quarry (Locality 9). A, right lateral; B, left lateral; C, dorsal; D, ventral; E, anterior; F, posterior views. Anatomical abbreviations: aas, anterior articular surface; bf, blind fossa; na, neural arch; ncj, neurocentral joint; pdc, posterodorsal concavity; pas, posterior articulation surface; pdc, posterodorsal concavity; rm, rock matrix; vlr, ventrolateral ridge; vh, ventral hollow. Scale bar = 50 mm.

Locality and horizon

NHM-PV R.3427 was found at the Mapelle Quarry (Locality 9). In this locality outcrops flagstones and conglomerate sandstones of the Salvador Formation (Massacará Group), that ranges from the Berriasian to Barremian time-interval.

Description and comparisons

NHM-PV R.3427 is a moderately preserved posterior caudal centrum, showing a platycoelous type intercentral articulation and strongly dorsoventral compression and elongation (), such as the posterior caudal vertebra of Diplodocus carnegii Hatcher Citation1901 and Barosaurus lentus (). A minor part of an anteriorly displaced neural arch is also observable (), and both anterior and posterior articulations have an ellipsoid outline (), like Barosaurus lentus and Tornieria africana.

The lateral surfaces of the centrum are flat. In addition, restricted blind fossae are present, which are asymmetrically developed (). Dorsally, the neural canal appears wide, occupying almost entirely the dorsal surface of the centrum (). As in NHM-PV R.2981(b), the dorsal surface also exhibits a broad posterodorsal concavity. However, the concavity in NHM-PV R.3427 is relatively shallower than in the NHM-PV R.2981(b), due to its more posterior position in the caudal series than in the latter specimen. In the ventral view (), two well-marked ventrolateral ridges are present and extend until the distal end of the centrum. The ventrolateral ridges in NHM-PV R.3427 are sharper than the present in NHM-PV R.2981(b) () and increase in width towards the lateral edges of the centrum, being more pronounced anteriorly. The development of these ridges delimits a deep and elongated longitudinal ventral hollow, as in Tornieria africana (Remes Citation2006), being straight in shape through most of its extension. Lastly, NHM-PV R.3427 differs from NHM-PV R.2981(b) due to the absence of prominent dorsolateral expansions in the posterior portion of the centrum. This absence of dorsolateral expansions is also observed in Barosaurus lentus, especially in the middle to posterior caudal vertebrae (e.g. Lull Citation1919). However, this corresponds to another feature that could represent a change along the individual caudal series.

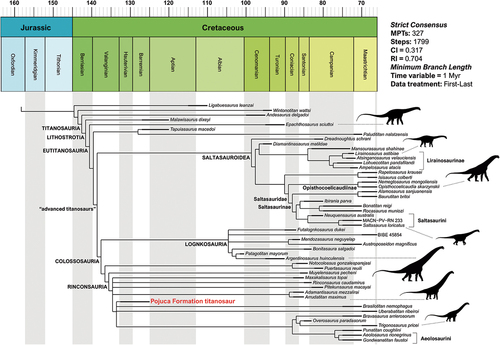

Neosauropoda Bonaparte Citation1986

Macronaria Wilson and Sereno Citation1998

Titanosauriformes Salgado et al. Citation1997

Somphospondyli Wilson and Sereno Citation1998

Titanosauria Bonaparte and Coria Citation1993

Lithostrotia Upchurch et al. Citation2004

Gen. et sp. indet.

Referred material

NHM-PV R.2129(a), represented by a complete anterior to mid-caudal centrum (; Table S2).

Figure 13. NHM-PV R.2129(a), isolated middle caudal centrum with lithostrotian affinities from the Hauterivian–Barremian Pojuca Formation at Itacaranha (Locality 5). A, right lateral; B, left lateral; C, dorsal; D, ventral; E, anterior; F, posterior views. Anatomical abbreviations: cd, condyle; ce, condylar edge; cf, chevron facet; ct, cotyle; cvj, costovertebral joint; lco, lateral concavity; nc, neural canal; ncj, neurocentral joint; vh, ventral hollow; vlr, ventrolateral ridge. Scale bar = 100 mm.

Locality and horizon

The specimen NHM-PV R.2129(a) was found at the beach outcrops near Itacaranha (Locality 5), associated with other vertebrate elements. These specimens come from the gravelly shale facies on yellowish mudstones that could pertain to the Hauterivian – Barremian Pojuca Formation.

Description and comparisons

NHM-PV R.2129(a) is a well-preserved and relatively small vertebral centrum, entirely lacking the neural arch. Based on NHM collection labels, NHM-PV R.2129(a) has been referred to the dyrosaurid Hyposaurus, given the procoelous nature of neosuchian vertebrae (e.g. Romer Citation1956). However, most Hyposaurinae taxa display platycoelous to amphyplatyan centra (e.g. Schwarz-Wings et al. Citation2009), contrasting with strong procoelous morphology seen in NHM-PV R.2129(a). The neural arch restricted on the anterior portion of the centrum () denotes an unambiguous titanosauriform synapomorphy (e.g. Salgado et al. Citation1997; Wilson Citation2002; D’Emic Citation2012; Mannion et al. Citation2013). In contrast, the neural arch in neosuchians occupies entirely the dorsal surface of the centrum (e.g. Salisbury and Frey Citation2001).

The presence of a well-marked serrated neurocentral and costovertebral joints (), and the diminutive size of the material as well (ca. 10 cm in length), leads us to believe that the specimen represents an immature individual (Griffin et al. Citation2021). The presence of marked scars of the M. caudofemoralis or M. ischiocaudalis on both dorsolateral edges of the centrum () suggest that NHM-PV R.2129(a) might be a distal anterior or a proximal middle caudal element (C10?), especially when compare with more complete caudal series known (e.g. Kellner et al. Citation2005; Lacovara et al. Citation2014). Additionally, the anterior margin of the neurocentral suture is undifferentiated from the dorsal edge of the cotyle, strongly linked to the advanced titanosaur clade Aeolosaurini (Franco-Rosas et al. Citation2004; Santucci and Arruda-Campos Citation2011; Bandeira et al. Citation2019).

The centrum has a developed procoelous type of intercentral articulation, in which the condyle apex is flushed above the longitudinal axis of the centrum, as in advanced titanosaurians (Powell Citation2003; Poropat et al. Citation2021). This condition differs from that observed in mamenchisaurids, turiasaurians, dicraeosaurids, and diplodocids, in which the procoely is limited to the anteriormost elements and its convexity apex is there below the longitudinal axis of the centrum (Mannion et al. Citation2019). The presence of procoelous middle caudal vertebrae is observed on several Upper Cretaceous titanosaur taxa, such as Baurutitan britoi and Dreadnoughtus schrani. In contrast, titanosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous exhibit a wide array of intercentral articulation types, varying from platycoelous, amphyplatyan, and mildly procoelous middle caudal vertebrae, as in Malawisaurus dixeyi Haughton Citation1928 (Gomani Citation2005) and Mnyamawamtuka moyowamkia (Gorscak et al. Citation2019). NHM-PV R.2129(a) exhibits strongly procoelous middle caudal centra as in the contemporaneous (Valanginian – Hauterivian) taxa Tengrisaurus starkovi Averianov and Skutschas Citation2017 (see also Averianov et al. Citation2021, Citation2023), Volgatitan simbirskiensis Averianov and Efimov Citation2018, as well as ‘Iuticosaurus valdensis’ (NHM-PV R. 146 and R.151) and the unnamed titanosaur NHM-PV R.5333 from Wessex Formation (Le Loeuff Citation1993; Upchurch et al. Citation2011).

In the anterior view (), the cotyle has a subcircular outline that slightly tapers ventrally. The ventral margin in this region is almost straight, a common feature of anterior to middle caudal vertebrae due to the attachment area decreasing for the M. caudofemoralis longus along the tail (Salgado and García, Citation2002). Laterally, the centrum of NHM-PV R.2129(a) is markedly concave, as in Maxakalisaurus topai Kellner et al. Citation2006 and aeolosaurines. The cotyle margin is slightly inclined anteriorly, but not as strongly as in Aeolosaurus rionegrinus Powell Citation1987, Gondwanatitan faustoi Kellner and Azevedo Citation1999, and Uberabatitan ribeiroi Salgado and Carvalho Citation2008 (Bandeira et al. Citation2019; Silva et al. Citation2019). The ventral face of the centrum bears prominent ventrolateral ridges (), likewise many titanosaurian taxa, such as Andesaurus delgadoi Calvo and Bonaparte Citation1991, Hamititan xinjiangensis Wang et al. Citation2021, and Saltasaurus loricatus Bonaparte and Powell Citation1980 (Powell Citation1992). These ridges border a shallow longitudinal hollow, as in the holotypic caudal vertebra of ‘Titanosaurus indicus’ (GSI-2191.2194; Mohabey et al. Citation2013), Isisaurus colberti Jain and Bandyopadhyay Citation1997 (Wilson and Upchurch Citation2003) and saltasaurines. However, NHM-PV R.2129(a) differs from the latter due this fossa is not well excavated, as in Saltasaurus loricatus and Rocasaurus muniozi Salgado and Azpilicueta Citation2000 (Sanz et al. Citation1999; Powell Citation2003; Zurriaguz and Cerda Citation2017). Similarly, to GSI-2191.2194, the NHM-PV R.2129(a) specimen has two chevron facets, present on both anterior and posterior portions of the centrum, but less developed than in the Indian taxon (see Wilson and Upchurch Citation2003: ). In addition, NHM-PV R.2129(a) lacks a marked mediolaterally compression, which gives a houglass-like shape to the centrum, as present in GSI-2191.2194. The articular surfaces for chevrons in the anterior face of NHM-PV R.2129(a) are oriented anteroventrally, while on the posterior one, the facets are ventrally oriented. Although not preserved in this specimen, this pattern indicates that chevrons of the NHM-PV R.2129(a) specimen had double articular facets, as in aeolosaurines (Santucci and Arruda-Campos Citation2011). Posteriorly, the developed condyle is featureless, lacking characteristic notches or sulcus ().

Saurischia Seeley Citation1888

Theropoda Marsh Citation1881

Averostra Paul Citation2002

Gen. et sp. indet.

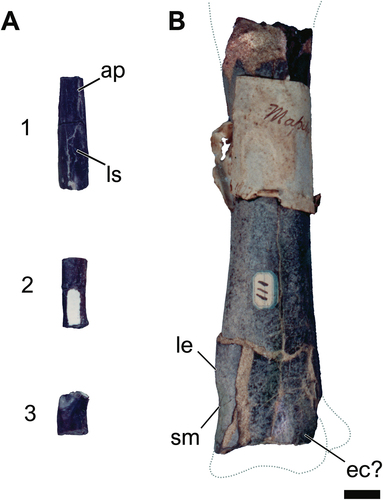

Referred material

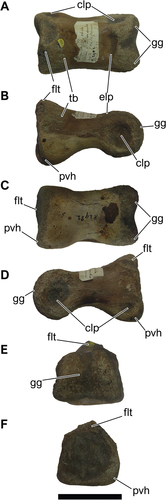

NHM-PV R.2982, a right pedal phalanx IV-1 (; Table S3).

Figure 14. NHM-PV R.2982, right pedal phalanx IV-1 of an indeterminate averostran from the Valanginian–Hauterivian Marfim Formation (Ilhas Group) at beach between Plataforma and Itacaranha (Locality 4). A, dorsal; B, right lateral; C, ventral; D, left lateral; E, anterior; F, posterior views. Anatomical abbreviations: clp, colateral pits; elp, extensor ligament pit; flt, flexor ligament tubercle; gg, ginglymus; pvh, posteroventral heel; tb, tubercle. Scale bar = 50 mm.

Locality and horizon

The specimen have been found in the beach outcrops between Plataforma Station and Itacaranha (Locality 4), Pedra Furada Bay, and recovered from fossiliferous shale intercalated with sandstone lenses. These facies are associated with the Valanginian – Hauterivian Marfim Formation.

Description and comparisons

The pedal phalanx NHM-PV R.2982 is relatively well preserved and presents some erosion on its surface, along the articular face of the proximal region. The specimen is dorsoventrally compressed in its midpoint (), acquiring a subtriangular shape on the distal portion (). It is elongated, robust, and rectangular in both dorsal and ventral views (). The phalanx is asymmetrical, maintaining a misalignment of its margins (). The distal articulation is ginglymoid (), while the proximal one is rounded and has a deep and wide collateral ligament pit. Robust and dorsoventrally compressed pedal phalanx are remarkable among abelisauroids and basal tetanurans (Coria et al. Citation2002; Novas et al. Citation2004; Carrano Citation2007; Brusatte et al. Citation2009; White et al. Citation2013). It contrasts with the slender, dorsoventrally taller, and elongated phalanx of noasaurids, some basal coelurosaurians, ornithomimosaurians, and maniraptorans (Novas Citation1997; Choiniere et al. Citation2010, Citation2012, Citation2014; Egli et al. Citation2016; Langer et al. Citation2019). Laterally, NHM-PV R.2982 has two heels proximally: a proximomedial (), which is more expanded and rounded distally; and a proximolateral () that is slightly taller and triangular. In lateral view, the specimen has a rectangular outline rather than a sharp triangular one (), as observed in Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Depéret Citation1896), Sinraptor dongi Currie and Zhao Citation1994, Allosaurus fragilis (Marsh Citation1877), and the carcharodontosaurid SHN.039 (Malafaia et al. Citation2019).

The flexor tubercle, in the lateral view, is aligned with the bottom of the proximal articulation. The dorsal surface of the distal articulation is marked by a shallow extensor groove, as in most theropods (). On the medial surface, an ellipsoid collateral pit marks the proximal portion, close to the articulation and above the posteroventral heel. The lateral collateral pit is slightly wider than the medial one. The ventral surface is almost flat and has a rectangular aspect with a small concavity in the proximal direction. Medially, the wider collateral pit and tall and laterally inclined ginglymus indicate that the NHM-PV R.2982 is a right pedal phalanx. The concave proximal articulation lacking a medial keel, the deepness of the extensor groove and the presence of a posteroventral heel indicates that the specimen is a phalanx IV-1 (e.g. Currie and Zhao Citation1993; Carrano Citation2007; Malafaia et al. Citation2019). The lack of comparative specimens with completely preserved pedes, as well as diagnostic features among postcranial skeleton of several theropod lineages, only allows an assignment to a large-bodied averostran theropod. NHM-PV R.2982 was recovered with other theropod remains (see below), suggesting that the specimen may belong to the same individual of NHM-PV R. 2980 or NHM-PV R.2981(a).

Averostra Paul Citation2002

Tetanurae Gauthier Citation1986

Orionides Carrano et al. Citation2012

Megalosauroidea Fitzinger Citation1843

aff. Spinosauridae Stromer Citation1915

Gen. et sp. indet.

Referred material

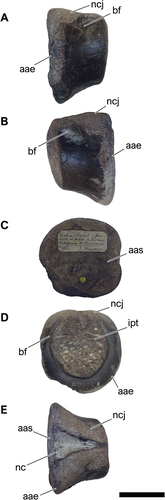

NHM-PV R.2980, one complete and well-preserved anterior caudal centrum (; Table S2). The theropod phalanx NHM-PV R.2982 was recovered from the same locality. However, the lack of additional data regarding the collection of the specimens hampers a secure association between both specimens as pertaining to the same individual.

Figure 15. NHM-PV R.2980, anterior caudal centrum with putative spinosaurid affinities from the Valanginian–Hauterivian Marfim Formation (Ilhas Group) at beach between Plataforma and Itacaranha (Locality 4). A, right lateral; B, left lateral; C, dorsal; D, ventral; E, anterior; F, posterior views. Anatomical abbreviations: as, anterior articular surface; bf, blind fossa; cvj, costovertebral joint; nc, neural canal; ncj, neurocentral joint; pas, posterior articulation surface; pvh, posteroventral heel; vh, ventral hollow; vlr, ventrolateral ridge. Scale bar = 100 mm.

Locality and horizon

The specimen was found in Locality 4, the beach outcrops between Plataforma Station and Itacaranha, Pedra Furada Bay, recovered from fossiliferous shale intercalated with sandstone lenses. These facies are associated with the Valanginian – Hauterivian Marfim Formation.

Description and comparisons

The vertebral centrum NHM-PV R.2980 is rectangular in both lateral, dorsal, and ventral views (), being subequal in elongation and height. The intercentral articulation is amphicoelous (), as in megalosauroids and abelisaurids, such as Pycnonemosaurus nevesi Kellner and Campos Citation2002 (Benson Citation2010; Mateus et al. Citation2011; Delcourt Citation2017; Malafaia et al. Citation2017, 2020). This feature contrasts with other ceratosaurians and avetheropods, in which the caudal centrum is constricted towards the midline, conferring a spool-like shape (e.g. Bonaparte Citation1991; Brochu Citation2003; Benson Citation2008; Persons and Currie Citation2011). NHM-PV R.2980 presents the posterior articulation dorsoventrally taller than the anterior articulation area (). NHM-PV R.2980 has a greater ventral extension in the lateral view (), presenting a lateral offset. It also differs from the unnamed spinosaurid from the Araripe Basin (MN 4743-V; Bittencourt and Kellner Citation2004) and Ichthyovenator laosensis Allain et al. Citation2012, which presents a parallel dorsoventral extension of articular areas. The dorsal region bears a well-marked neurocentral and costovertebral joints, with several crenulations, suggesting that the centrum and neural arch were unfused at the time of death as in other archosaurians (Brochu Citation1996) and other specimens described here.

In dorsal view (), the midpoint of the centrum is constricted, forming an ‘X’ aspect due to the unfused region of the neural arch pedicel and transverse processes. The lateral surfaces have broad and shallow pleurocentral depressions (), which is common among theropods. A small blind fossa is present on the anteroventral portion on the left surface but absent on the right one. The ventral surface of the centrum has a longitudinal hollow, bounded by slightly sharp ventrolateral ridges (). Close to the posterior articulation, the ventral surface bears a pair of chevron facets, which characterises this vertebra as a caudal element.

The shallow and wide ventral hollow bounded by ridges is a remarkable feature among Megalosauroidea, in particular spinosaurids (Benson Citation2010; Mateus et al. Citation2011; Rauhut et al. Citation2016; Malafaia et al. Citation2019). Among Abelisauroidea, some taxa present the ventral surface with a deep but narrow groove running along the midline, such as Masiakasaurus knopfleri Sampson et al. Citation2001 (Carrano et al. Citation2002), Eoabelisaurus mefi Pol and Rauhut Citation2012, Aucasaurus garridoi Coria et al. Citation2002, Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte Citation1985, Ilokelesia aguadagrandensis Coria and Salgado Citation2000 (sensu Delcourt Citation2017), and Viavenator exxoni Filippi et al. Citation2016. Compared to MN 4743-V, the specimen NHM-PV R.2980 differs in the presence of a shallower hollow and fainter paired keels more restricted to the posterior portion of the centrum. In ceratosaurians and tetanurans, the ventral surface bears no structure such as narrow grooves nor a deep ventral hollow (Méndez Citation2014). The shape of the centrum resembles the Barremian species from Europe than to the Aptian – Albian specimen from Brazil MN 4743-V, such as Vallibonavenatrix cani from Spain (Malafaia et al. Citation2019), Baryonyx walkeri Charig and Milner Citation1986, and Iberospinus natarioi Mateus and Estraviz-López Citation2022, recovered, respectively, in England and Portugal (Mateus et al. Citation2011). However, given the absence of a preserved neural arch, we cannot assign it to Baryonychinae or Spinosaurinae.

Orionides Carrano et al. Citation2012

Avetheropoda Paul Citation1988

Allosauroidea Marsh Citation1878

aff. Carcharodontosauria Benson, Carrano and Brusatte, Citation2010

Gen. et sp. Indet.

Specimen A

Referred material

NHM-PV R.2981(a), posterior half of the dorsal centrum (; Table S2). The theropod phalanx NHM-PV R.2982 was recovered from the same locality. However, the lack of additional data regarding the collection of the specimens hampers a secure association between both specimens as pertaining to the same individual.