Abstract

Members of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) exhibit strong economic, social and cultural connection with and dependence on the marine and coastal environment. Efforts to encourage the sustainable use and protection of the ocean and its resources should therefore be an area of interest and competence for the regional group which seeks to engender cooperation in matters of economic and social development. This paper examines the regionally relevant institutional arrangements that frame and execute ocean development and governance within CARICOM. It finds that while some important sectors, such as fisheries and tourism, have specific organizations established geared toward regional coordination in management of those activities, others, including offshore oil and gas, marine scientific research, and port and shipping development, lack similar arrangements. Additionally, the CARICOM group lags in adopting a holistic, ecosystem approach to ocean management with siloed approaches dominating and few formal mechanisms for intersectoral coordination existing. This paper advocates for and proposes means toward increased integration at a regional level for the management and continued governance of the marine space, its associated resources and activities. It also seeks to encourage the participatory development of a regional blue economy policy framework and strategy which would outline, among other things, CARICOM’s ocean vision and development priorities.

Introduction

Sustainable management of the ocean and its resources are integral to small-island developing States (SIDS) and the sustainable livelihoods of their inhabitants (Bennett et al. Citation2019; Connell Citation2013). This fact is underscored in a number of United Nations soft law documents such as Agenda 21, the Barbados Programme of Action, the Mauritius Strategy, the SIDS Accelerated Modalities of Action (Samoa) Pathway, several successive General Assembly resolutions on oceans and the law of the sea, and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The ocean now holds prominent standing within the sustainable development framework with SDG 14 being dedicated to conservation and sustainable use of the ocean, seas and marine resources for sustainable development. Additionally, since the 2012 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio + 20), SIDS, with their small land masses but large ocean spaces, have advocated for and adopted the blue economy paradigm (Silver et al. Citation2015). SIDS see the blue economy concept as adequately reflecting the ocean’s importance to them and consequently it now largely frames their developmental discourse (Vierros and De Fontaubert Citation2017).

There is no single agreed upon definition of the blue economy (Smith-Godfrey Citation2016) which has been partly responsible for its numerous interpretations (Voyer et al. Citation2018). Notwithstanding, blue economy is supposed to encompass marine-based economic activity that emphasizes improved human well-being, social justice and equity, ensuring conservation of natural resources and ecological sustainability. Naturally, Caribbean nations have been engaging in pursuits geared toward blue economy development (Patil et al. Citation2016). However, in light of the close proximity of the islands, dynamic and ever-changing environmental conditions and a high dependency on shared resources and space, it is increasingly recognized that a cooperative approach among the countries of the region is needed (Hassanali Citation2020). That being said, a comprehensive regional ocean governance model, which would support collaborative blue economy development, has long been elusive (Blake Citation1998).

This paper explores integrated regional ocean governance. A well-integrated regional ocean governance approach is seen as a pre-requisite to achieving effective blue economy development, particularly in SIDS regions (Fanning and Mahon Citation2020; Keen et al. Citation2018; Roy Citation2019). The next section will scope this study geographically and Section 3 provides insight into its analytical framework. In light of the analytical framework detailed, Sections 4 and 5 examine the relevant existing ocean governance institutions in the region while Section 6 considers where gaps exist. Section 7 presents a concluding discussion. The intention is to detail measures to better deliver coordinated and collaborative blue economy development in the Caribbean.

Defining the region

The 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) Agenda 21 established an internationally agreed action plan for sustainable development into the 21st century (Kimbal Citation1993). The plan called for an “integrated and multisectoral approach to marine issues” at the regional level. Examples of efforts can now be found worldwide, with diverse approaches that cater to specific regional priorities, actors, geographical scales, environmental conditions and other peculiarities (Cicin-Sain et al. Citation2015; Mahon and Fanning Citation2019a). Wright et al. (Citation2017) have identified five core types of regional ocean governance initiatives which are popular globally:

Regional Seas Conventions and Action Plans

Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs)

Regional Fisheries Bodies (RFBs)

Leader-driven initiatives

Political and economic communities that engage in regional ocean governance

In the Caribbean region all these typologies can be found co-existing in a polycentric governance system (Mahon and Fanning Citation2019b). For instance, the Cartagena Convention is the regional legal agreement for protecting the Caribbean Sea under UN Environment’s (UNEP) Regional Seas ProgrammeFootnote1. The CLME + InitiativeFootnote2, which encompasses the Caribbean LME (CLME) and the North Brazil Shelf LME (NBLME), is a suite of projects that is implementing a 10-year Strategic Action Programme (SAP) for sustainable management of shared living marine resources in the CLME + region. It notably adopts a Regional Ocean Governance Framework and a regional coordination mechanism. The Western Central Atlantic Fishery Commission (WECAFC), the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism (CRFM), the Central American Fisheries and Aquaculture Organization (OSPECA) and the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas are fisheries management bodies whose geographical area of operation and material scope include part or all of the Caribbean Sea. With regard to leader-driven initiatives, the Caribbean Challenge InitiativeFootnote3 is one such example. Lastly, political and economic communities that have interest, influence and which undertake ocean governance in the region include the Association of Caribbean States (ACS), the Central American Integration System (SICA), the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States Economic Union (OECS) and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM).

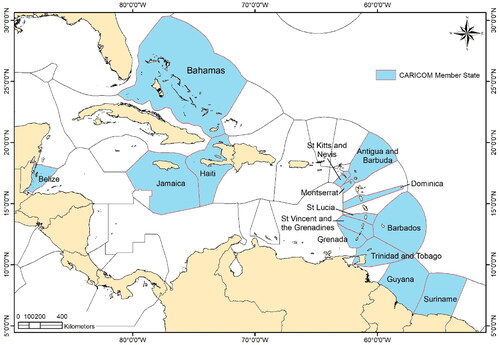

This paper focuses almost exclusively on CARICOM’s regional ocean governance and blue economy approach. CARICOM is the longest standing integration movement in the Latin American and Caribbean region comprising twenty countries – fifteen Member States and five associate members (O’Brien Citation2011). The Member States of CARICOM are Antigua & Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Montserrat, St Lucia, St Kitts & Nevis, St Vincent & the Grenadines, Suriname and Trinidad & Tobago ().

All are low-lying coastal or small-island developing countries (designated SIDS by the UN). Although its members make up less than a third of the countries and territories bordering or located in the Caribbean Sea, the group’s long history and commitment to cooperating and coordinating on a range of issues makes CARICOM a significant bloc in the region. CARICOM rests on four main pillars of integration: economic; security; human and social development; and foreign policy coordination. The ocean is central to CARICOM’s economic, social and cultural identity with 82% of Member States’ collective jurisdiction being made up of marine areas which adjoin their comparatively tiny land masses (Haughton Citation2005). In her installation as the 8th Secretary General of CARICOM in August 2021, Dr Carla Barnett flagged improved blue economy engagement as important to the CommunityFootnote4.

Analytical framework and data collection methods

The dimensions and scope of integration that guided this paper on what is needed in CARICOM were adapted from dimensions previously outlined by Cicin-Sain et al. (Citation1998) in their systematic examination of integrated coastal and ocean management (ICOM) in various national contexts over several years. In this current work, which is situated in a regional context, the dimensions of integration were shaped and understood as follows:

Intersectoral integration. This dimension’s considerations are almost identical at the regional level as at the national level. It considered the need to take into account conflicts and synergies among different ocean uses; between the environment and individual ocean uses; and between the environment and all ocean uses. Marine spatial planning (MSP) has been recognized as a useful tool for achieving intersectoral integration in ocean management both within space and time (Douvere Citation2008).

Intergovernmental integration. As opposed to the national to provincial to local level linkages made in national ICOM practice, vertical integration within the regional context is more concerned with how and to what extent regional prescriptions are adopted nationally. The converse is also of interest i.e. enabling States within the regional bloc to exert influence on and guide development of regional ocean policies, both within individual sectors and also more holistically. Intergovernmental integration, complemented by genuine participation and consultation with a wider body of stakeholders, is an important pre-requisite for enabling a region to establish and work toward a common vision for ocean governance and use.

Spatial integration. Under national ICOM, spatial integration is largely focused on management across the land-sea interface. From the regional perspective though, this dimension was reinterpreted to capture considerations relating to managing ecosystems and their components across the jurisdictional zones established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) i.e. archipelagic waters, territorial sea, exclusive economic zone, continental shelf, the high seas and the Area. Under UNCLOS, coastal States are afforded particular rights and responsibilities in these respective zones. Spatial integration at a regional level necessitates collaboration and coordination to manage ecosystems, resources and activities that straddle or are connected across UNCLOS defined jurisdictional zones. Spatial integration encourages a dual approach to regional ocean management (Tanaka Citation2016) marrying the zonal management of UNCLOS with the ecosystem approach that takes on board dynamics and realities, ecological and otherwise, of the biophysical environment, resources and activities of concern.

Science-management integration. Similar thinking is applied here at the regional level when compared to the national level. Policies and decisions should be informed by and based on sound science which has sought to understand ecosystem form, function and component interaction, including impact of human activity on the natural environment and vice versa (McConney et al. Citation2016a).

International integration. This dimension of integration within national ICOM practice more often refers to enabling sovereign nation States to collaborate, co-ordinate and negotiate in dealing with issues that have transboundary contexts. This is already partially captured in the spatial dimension of integration outlined for the regional approach. In this proposed rubric for regional integration of ocean management, international integration takes the form of representing, advocating for and negotiating the common interests of the bloc on global platforms. It may also deal with how the regional arrangement, as a whole, interfaces with other regional arrangements. CARICOM acting as a bloc within the CLME + framework for management of the wider Caribbean marine environment (Debels et al. Citation2017; Fanning et al. 2021) would be an example of international integration in practice. Another is the Member States of CARICOM effectively negotiating as a group in the process to craft an internationally legally binding instrument under UNCLOS on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (the BBNJ agreement) (Hassanali Citation2018). The Council for Foreign and Community Relations (COFCOR) guides how and when CARICOM member States jointly engage on the global stage.

These dimensions of integration were used to examine the legal and policy documents and organizational arrangements that guide ocean governance in CARICOM. Semi-structured interviews and informal consultations complemented this analysis. They targeted key individuals within CARICOM regional organizations, academia and the non-governmental sector, allowing for a more complete understanding and consideration of the region’s important and emerging ocean sectors and their existing and potential governance architecture. The discussions also elicited viewpoints on whether and how the integration dimensions were being operationalized and any practical suggestions toward improving this. Participants were sourced from the author’s professional network and additional recommendations made by interviewees.

The Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas as a guide for operationalizing regional ocean governance within CARICOM

CARICOM came into being in 1973 with the signing of the Treaty of Chaguaramas. In 2001, this Treaty was significantly amended and the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas was signed establishing the Caribbean Community, including the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME). The Revised Treaty now steers the present-day activities of CARICOM. Among other things, it details the principles and objectives of the group, outlines the group’s governance structure and specifies the functions of the various organs, and gives broad guidance on sectoral policy development.

The Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas does not explicitly guide regional ocean governance and overarching blue economy policy development and execution. It is certainly not as categorical on these interconnected topics as the 2010 Revised Treaty of Basseterre which guides the functioning of the OECS – a subregional, sister organization to CARICOM made up primarily of a subset of CARICOM members. The latter Revised Treaty more specifically identifies how oceans are to be treated. Article 4.2(o) entreats OECS Member States to “co-ordinate, harmonize and undertake joint actions and pursue joint policies in matters relating to the sea and its resources”. Resultantly, the OECS has established an Oceans Governance Team (OGT), formulated and approved an Eastern Caribbean Regional Ocean Governance Policy (ECROP) and is implementing the ECROP through the execution of initiatives such as the Caribbean Regional Oceanscape Project (CROP) (OECS Citation2020). Consequently, ocean management in the Eastern Caribbean is trending toward being more holistic, cross-sectoral and integrated when compared to CARICOM as a whole.

Prescriptions in the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas have encouraged (or certainly not discouraged) a more fragmented approach to joint management of the oceans among CARICOM Member States when compared to the OECS. In CARICOM, the Council for Trade and Economic Development (COTED), is the organ appropriately placed to encourage regional ocean governance measures and facilitate blue economy policy formulation and implementation. COTED’s responsibilities are listed in Article 15 of the Revised Treaty. Among those that can be directly tied to ocean management are:

Establishing and promoting measures to accelerate structural diversification of industrial and agricultural production on a sustainable and regionally-integrated basis;

Promoting and developing policies and programmes to facilitate the transportation of people and goods;

Promoting measures for the development of energy and natural resources on a sustainable basis;

Establishing and promoting measures for the accelerated development of science and technology; and

Promoting and developing policies for the protection of and preservation of the environment for sustainable development.

The Revised Treaty also establishes goals and objectives of some specific sectors which are ocean related and fall under COTED’s purview (). These include tourism, natural resource management, fisheries, environmental conservation and maritime transport. Therefore, the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas provides CARICOM Member States the impetus to coordinate their management of some (but not all) important ocean-based sectors and issues. Critical institutions currently operating in these regards are discussed in further detail in the ensuing sections. However, the Revised Treaty’s guidance remains predominantly sectorally prescribed, with limited consideration to interlinkages, and this especially inhibits intersectoral integration as discussed in Section 3. Science-management and international integration dimensions are better accounted for in the Revised Treaty and it is, in itself, a legal document to effect intergovernmental integration. Nonetheless, the resulting management approach within CARICOM with regard to oceans is insufficient when considering contemporary insights (Winther et al. Citation2020; Rochette et al. Citation2015; Soma et al. Citation2015). The regional group is lagging in pursuing a coordinated, cross-sectoral, ecosystem approach to ocean governance and management. Additionally, the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas does not have wording that explicitly encourages integration of ocean management at the national level and this too impedes attempts to achieve it on a regional scale. That being said, and as will be expanded upon in section 6, some CARICOM countries have pursued such national initiatives on their own accord.

Table 1. Sectoral policy provisions in the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas with relevance to regional ocean governance and blue economy development for CARICOM.

CARICOM organizations with roles in coordinated regional ocean governance efforts

To promote the Revised Treaty’s objectives and help implement the Community’s strategic decisions, CARICOM has established numerous entities. This section examines several of them and their contributions or potential contributions to achieving the integration dimensions discussed in Section 3 and blue economy development more generally.

Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism

As highlighted earlier, regional fisheries bodies are common regional initiatives. CARICOM’s inter-governmental fisheries arrangement is the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism (CRFM) (Haughton et al. Citation2004). Its mission is to “promote and facilitate the responsible utilization of the region’s fisheries and other aquatic resources for the economic and social benefits of the current and future population of the region.” (CRFM Citation2013).

The CRFM was instrumental in convening stakeholders to collaboratively develop CARICOM’s Caribbean Community Common Fisheries Policy (CCCFP), a binding treaty (McConney et al. Citation2016b). Unsurprisingly, given its already established mandate which includes conducting scientific work, providing management advice and facilitating networking and collaboration, CARICOM has tasked the CRFM supporting CCCFP parties in the treaty’s implementation. In sum, the CRFM has been important to all the integration dimensions reviewed in Section 3 as it relates to fisheries, although an independent performance review found the CRFM requires increased resources to be more effective (FAO Citation2013). Effectiveness may also be enhanced if a structure, similar to what is proposed in Section 6.4, is put in place.

Caribbean Community Climate Change Center

Within CARICOM, climate change should be central to blue economy development strategies and regional ocean governance thrusts because of its substantial, constantly evolving, and far reaching societal implications (IPCC Citation2019; Allison and Bassett Citation2015). The Caribbean Community Climate Change Center (5Cs) is therefore another important actor in this discussion on integrated regional ocean management.

The 5Cs can be especially critical in promoting international and science-management integration by mainstreaming climate change considerations into ocean sectors. The Center has undertaken several projects in these regards including encouraging climate neutral cruise and dive tourism, developing a regional action plan for building resilience of coral reefs, and boosting coastal protection ecosystem services through rehabilitation and better management of natural habitats. In addition, the 5Cs has conducted vulnerability and impact assessments for, among others, the tourism sector in Barbados and St Lucia and the fisheries sector in Jamaica. With growing interest in the ocean-climate nexus it is expected that the Center’s engagement in ocean spaces will increase (Hollowed et al. Citation2019).

Formally involving the 5Cs in a cooperative and coordinated regional ocean governance arrangement could not only help ensure that ocean policy and management actions across a range of sectors are climate smart and relevant, but it would also help the Center in achieving its mandate on a more macro level and with enduring influence beyond project-type modes of implementation. For example, oceans may be more adequately considered in any regional climate policy that is to be developed and adopted (Dundas et al. Citation2020). The 5Cs accreditation as a Regional Implementing Entity to the Green Climate Fund (GCF) could also prove valuable in helping regional partners access funding to undertake ocean management initiatives with climate change adaptation and mitigation implications.

Caribbean Center for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency

The Caribbean Center for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (CCREEE), established in 2018, promotes itself as the regional implementation hub for sustainable energy activities and projects. Operating across seven strategic programme areas: knowledge management and transfer; sustainable transport; finance and project support; climate resilience; and sustainable buildings, CCREEE aligns with and is guided by the CARICOM Energy Policy (CEP) and Caribbean Sustainable Energy Roadmap and Strategy (C-SERMS). One of the CEP’s objectives is to attain greater use of renewable energy for electricity generation as well as in the transportation, industrial and agricultural sectors consistent with the C-SERMS target of 47% renewable power capacity by 2027. Established, new and emerging marine energy sources including offshore wind, floating solar, wave, and ocean thermal energy conversion could have a great role in achieving CARICOM’s renewable energy targets (Haraksingh Citation2020).

As the regional institution tasked with promoting renewable energy and energy efficiency it is therefore imperative that CCREEE is included in cooperative arrangements to develop and manage CARICOM’s blue economy. Apart from seeking to have the diverse forms of offshore renewable energy developed in an environmentally sound manner and in ways that minimize conflict with other ocean users and uses, involvement of CCREEE could extend into other realms such as assisting in the decarbonization of the maritime transport sector in the region. Thus, its potential to encourage intersectoral integration must be recognized and capitalized upon. As a relatively new institution, it is an ideal time to identify CCREEE’s potential blue economy development roles and functions thereby allowing these to be considered, accommodated and effectuated in these embryonic stages before the organization fully matures.

Caribbean Public Health Agency - Environmental Health and Sustainable Development Department

Globally, blue economy initiatives often undervalue environmental conservation and protection (Voyer et al. Citation2018; Bennett et al. Citation2021). One way of minimizing the likelihood of this occurring within CARICOM is to actively involve the Environmental Health and Sustainable Development (EHS) Department of the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA) in developing and implementing blue economy policy and governance in the region. The Department seeks to help manage the environment in the region for optimal public health by, among other things, providing environmental monitoring services and aiding Member States in conducting and evaluating multidisciplinary environmental impact assessment (EIA).

The EHS department can be an important actor in thrusts toward intersectoral, spatial and science-management integration. It currently has a public health focus and to advise on and effectuate mainstreaming environmental best practices into the policy and management of the wide range of sectors operating in the coastal and ocean realm it is foreseeable that the department may need to expand its operational lens, capacity and mandate. Given its EIA expertise, it may also be opportune to explore the possibility of the Department facilitating and guiding the conduct of regional environmental assessments (REA) in the marine space (Gunn and Noble Citation2009). REA are a proactive environmental assessment approach in which project-based EIA can be situated and which can help in identifying environmentally sensitive and vulnerable areas which may need to be afforded special attention.

Caribbean Tourism Organization

Tourism is one of CARICOM’s most important economic sectors overall and is considered a major component of the CARICOM blue economy (Clegg et al. Citation2020b; Cannonier and Burke Citation2019). While not being a strictly CARICOM institution (it has 24 Dutch, English, Spanish and French speaking country members) the Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO) is headquartered in Barbados and all CARICOM Member States are represented on CTO’s Council of Ministers and Commissioners of Tourism. The CTO does not have a specific programmatic area related to oceans and coasts. However, it has a number of objectives which align well with developing the blue economy in a harmonized way.

As a functional cooperation organization, the CTO has existing intersectoral and intergovernmental integration efforts which can be built upon. These include being a collaborative mechanism and a liaison for tourism matters between Member countries; providing advice, technical assistance and opportunities for capacity development; increasing the tourism sector’s sustainability by researching and recommending means to minimize environmental impact; and strengthening linkages between tourism and other economic sectors. In addition, the CTO also includes in its membership a number of non-governmental, albeit mainly private sectors actors, who can serve as partners in tourism planning and innovation in the region (Séraphin et al. Citation2018).

Missing pieces to the organizational landscape?

The above discussion suggests several gaps in the CARICOM institutional framework. The following are some proposed organizations and mechanisms to coordinate and achieve more comprehensive regional ocean governance within individual sectors, and across sectors and transboundary spatial scales. Also examined is how they may further integration across the dimensions discussed in Section 3.

Caribbean Organization for Offshore Extraction (COOE)

Offshore extractive industries, in particular oil and gas extraction and deep seabed mineral mining, are major, albeit controversial, constituents of blue economy development in several parts of the world (Bond Citation2019; Carver Citation2019; Hunter and Taylor Citation2014). The ‘resource curse’ often associated with extractive industries (Ross Citation2015), continued promotion of carbon intensive energy pathways in light of climate change (in the case of offshore oil and gas development), and the as yet uncertain, likely long-term and perhaps irreversible impacts of deep seabed mining on sensitive marine environments (Levin et al. Citation2020), leave open the question of whether these activities are truly in-keeping with ideas of blue economy development given the concept’s social and environmental dimensions.

At least one CARICOM country, Trinidad and Tobago, has a long history of offshore oil and gas production (Boopsingh and McGuire Citation2014). Barbados has also undertaken some offshore hydrocarbon development, but to a far lesser extent. More recently Suriname, and more so, Guyana, have been positioning themselves as major emerging players on the global stage in offshore oil and gas development (Panelli Citation2019). Jamaica is also touted as having great offshore oil potentialFootnote5. However, offshore hydrocarbon development is not a universal pursuit among CARICOM member States. For instance, Belize has legislated a moratorium on all petroleum activity in its maritime zones with a view to safeguarding its marine environment including the Belize Barrier Reef system (Tudela Citation2020). Other CARICOM countries may not have the necessary geological conditions existing within their territories that lend to the presence of viable hydrocarbon reservoirs.

With regard to deep seabed mining, there is no active deep seabed mineral mining (be it exploration or exploitation) taking place within the waters of CARICOM nations at present. This though does not preclude these activities taking place in the future if countries decide that this form of resource extraction should be pursued. Indeed, Jamaica, which hosts the International Seabed Authority (ISA) – the organization that regulates deep seabed mining in areas beyond national jurisdiction (Lodge Citation2017) – is already venturing into developing deep seabed mining opportunities. The country is sponsoring a company, Blue Minerals Jamaica Limited, which has received approval to explore for polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) located in the Pacific OceanFootnote6. Although the company is, for now, aiming to operate in ocean space far removed from the Caribbean and in an area administered by the ISA, Jamaica has demonstrated that there is interest by States within CARICOM to get involved in deep seabed mining. The situation also shows that there is potential for CARICOM members, individually or collectively, to strategically pursue opportunities in this emerging sector.

In light of the preceding points, and to facilitate integration as envisioned in Section 3, an organization which would encourage cooperation by CARICOM members in exploration of offshore non-living resources might be useful. Proposed here is the formation of the Caribbean Organization of Offshore Extraction (COOE). This body could provide the framework to encourage joint ventures by countries within the group, be it within the Caribbean itself or further afield. It could also enable knowledge transfer and sharing of expertise between the States where capacity already exists and those CARICOM members seeking to develop it (Mohan et al. Citation2021). Additionally, the organization may facilitate the implementation of cross-regional environmental standards and institutional best practice. Lastly, the COOE may be a vehicle through which the private sector and civil society can adequately engage in matters surrounding offshore extractive industries at a regional level and through which CARICOM could participate in the activities of the Regional Association of Oil and Natural Gas Companies in Latin America and the Caribbean (ARPEL).

Caribbean Ports and Maritime Organization (CPMO)

CARICOM occupies a privileged geographical location, lying at the gateway to the Panama Canal and at an intermediate point between major East-West and North-South global trade routes. Nations within the group, in particular Jamaica, Bahamas and Trinidad and Tobago, have been able to capitalize on this strategic positioning by creating maritime freight and transhipment operations (McCalla et al. Citation2005). In addition, several CARICOM countries are flag States operating open registries for commercial vessels. The Bahamas is noteworthy, ranking among the top 10 flag States globally by gross tonnage in 2020Footnote7. In operating open registries, nations have a responsibility to enforce international regulations on ships flying their flags including as it relates to safety, labor and the environment (Zwinge Citation2011).

For other CARICOM countries who may not be as involved in international shipping activities, effective and efficient maritime transport and port management is still recognized as integral facets to their development. They are important in tourism, both with regard to cruise shipping operations and in the import of commodities needed to make mass tourism functional and viable. Maritime activities are also key to islands’ food and energy security, the latter evidenced by the fact that almost all CARICOM countries are dependent on petroleum imports to meet their energy needs (Bryan Citation2009). Additionally, maritime transport is recognized as having the potential to play an increasing role in meeting the need for better intra-regional mobility and inter-island connection within the group (Roberts et al. Citation2016).

As highlighted earlier, the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas has already recognized the need for COTED to encourage coordination and collaboration among CARICOM States in the development of maritime transport services. However, no formal subsidiary mechanism has been created to facilitate this. Establishment of the Caribbean Ports and Maritime Organization (CPMO) may be a first step in meeting this need. This organization could be tasked with the responsibility of enabling all that is outlined in the Revised Treaty and encouraging regional implementation of agreed safety, security and environmental precepts in governance of the maritime industry. The CPMO can also serve as a regional focal point for when engaging in cross-sectoral discussions on port and maritime matters that affect other important regional sectors such as cruise shipping in tourism and port control measures as it relates to fishing and the combat of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) activity.

Caribbean Center for Marine Science (CCMS)

The conduct and subsequent availability of sound science and evidence-based approaches as being critical for guiding decisions on the conservation and sustainable use of the marine and coastal environment is an undisputed fact (Pendleton et al. Citation2020; Visbeck Citation2018; Boesch Citation1999). Indeed, this is reaffirmed in the SDGs where target 14a seeks the increase of scientific knowledge, research capacity and marine technology transfer in order to improve ocean health and wise use. SIDS are to be particularly focused on striving to achieve this target because of their disproportionate needs.

Within CARICOM various aspects of marine scientific research are currently conducted in a largely uncoordinated manner through an assortment of actors (Mahon and Fanning Citation2021). These include universities and academic institutions in the region, foremost of which is the University of the West Indies at its three main campuses in Barbados, Jamaica and Trinidad and a fourth to be established in Antigua; existing regional organizations such as CRFM and the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology (CIMH); private and not-for-profit organizations; branches of government ministries and departments; and, in one case, a dedicated marine scientific research institution established by the State, the Institute of Marine Affairs (IMA) in Trinidad and Tobago. However, marine scientific research capacity and communities of practice are neither uniformly nor adequately distributed throughout CARICOM. Additionally, even in countries where comparatively more capabilities exist, there is still a need for increased competences in a range of areas and expertise (Harden-Davies et al. Citation2020).

Outlined in Article 276 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the benefit and necessity of creating regional centers for marine research has been recognized. In this regard, CARICOM could seek to add such an institution to its regional ocean governance architecture through establishing the Caribbean Center for Marine Science (CCMS). The functions of such an organization may be many. It could formulate a regional research agenda based on blue economy aspirations, and pursue strategic partnerships to fund research and encourage capacity development and the transfer of marine technology. The CCMS may also co-ordinate marine scientific research within CARICOM by, inter alia, acting as a data repository, creating a network of scientific expertise that could be drawn upon when required, and establishing working groups on key areas of interest. Lastly, CCMS may also be a facility through which pure and applied ocean science is conducted, acting as a center of excellence for the Caribbean in and of itself.

The Pacific Community (SPC) in the Pacific region and Europe’s International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) provide structures and modes of operation which CARICOM can explore and adapt in modeling the CCMS (Salpin et al. Citation2018; Walther and Mölmann Citation2014; Hempel 2002). CARICOM can seek to capitalize on the momentum and interest in marine science being generated by the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development 2021–2030 and position the CCMS to be a possible tangible outcome for the Decade (Claudet et al. Citation2020; Ryabinin et al. Citation2019).

Caribbean Blue Economy Forum

Attempting to harmonize strategic ocean direction and subsequently maximize blue economy potential within CARICOM is a complicated endeavor given the number of countries participating and the range of ocean activities and sectors, all sharing and competing for limited space and resources in the Caribbean’s coastal and marine environment. As suggested earlier, coordinating activities of Member States just within individual sectors is not enough. Interactions between the different sectors and across all countries, would also have to be coordinated in order to encourage sustainability, minimize negative pressures and optimize the benefits that can accrue to the CARICOM group. The Caribbean Blue Economy Forum is an arrangement which, it is anticipated, can help facilitate this. The Forum would be a venue to especially promote intersectoral and intergovernmental integration, allowing a full range of complex stakeholder interactions to take place, including regional actors interfacing with national actors, the realization of cross-sectoral engagement and national actors interacting with each other.

Within the Caribbean Blue Economy Forum, it is envisioned that countries would be represented by designated nominees from their national bodies tasked with ocean and coastal activity coordination and/or management. Some CARICOM countries already have such bodies existing as institutional arrangements stemming from national ocean governance efforts and associated attempts to integrate management (Muñoz Citation2020; McConney et al. Citation2016c). For instance, Belize has a Coastal Zone Management Advisory Council and Trinidad and Tobago currently has an Integrated Coastal Zone Management inter-ministerial committee. Where such national bodies do not presently exist they will have to be established and properly operationalized especially in the recognition that these arrangements are best practice globally (Cicin-Sain et al. Citation1998). Such operationalization initiatives have been undertaken within the OECS for example, through the ECROP and CROP. The CLME Initiative has also encouraged and led to the creation of national integration committees (NICs) (Compton et al. Citation2020; Fanning et al. Citation2021). National representatives in the Forum will be joined by officials from the regional bodies with roles in aspects of ocean governance and management including those previously outlined or suggested. Lastly, the Forum will also reserve spaces for participation and engagement by civil society organizations with a region wide mandate and advocates for traditionally under-represented groups such as youth, women and indigenous people.

The Caribbean Blue Economy Forum can perhaps convene once a year for in-person meetings. Here the setting may be provided to consolidate visions, discuss ideas and developments and explore synergies and conflicts between all actors operating in the ocean space. The forum can also be a venue where asymmetrical power relations can be managed through consensus building. Of course, coordination of stakeholders would have to occur on a continuous basis and outside of the Forum this could be facilitated by the CARICOM Secretariat, who, to be wholly effective, may need to create and resource a programmatic department dedicated to blue economy and oceans. Operating in tandem, the Blue Economy Forum and the CARICOM Secretariat can engender collaboration among vested interests, building understanding, connections, trust and the social capital needed for collective action toward sustainable ocean management in the region (Brondizio et al. Citation2009).

Discussion and conclusion

Institutional and policy integration is needed for effective blue economy development and will require the restructuring of organizational mandates and relationships (Singh et al. Citation2021). Depending on scope, resources, capacity and contextualization to suit the given circumstances in which they are embedded, institutions could succeed in giving voice to stakeholders, charting strategic directions, implementing approaches, evaluating successes and failures, reassessing priorities, adapting to changing circumstances and deepening integration (Cairney Citation2019). This analysis reveals that the levels of integration needed for sustainable development within CARICOM’s marine areas remains underwhelming, with organizational structures and interactions that are not entirely fit to optimize blue economy development. The key informants and practitioners consulted recognize this and acknowledge the need to improve.

To effect improvements, it must be emphasized that the regional ocean governance structure cannot stand alone. The structure’s activities and pursuits should be grounded in a clearly articulated overarching policy, collaboratively arrived at by all members and stakeholders of the regional arrangement. This policy should outline long term vision, guiding principles and objectives with regard to the region’s sustainable ocean related development (Elliott et al. Citation2020). Creating such a policy will not only promote regional stability but also allow for consistency as CARICOM engages in extra-regional and international fora, thus aiding in making international integration more effective. The policy could also explicitly speak to the dimensions of integration that have been highlighted and strategies to further enhance them.

Developing a CARICOM blue economy policy framework should therefore be paramount. The CARICOM Secretariat could drive this policy formulation using a mechanism with similar ideological underpinnings to the Caribbean Blue Economy Forum if, at that point in time, the Forum has not already been formally operationalized. The Forum and all that it entails, will be a lynchpin in deepening integration in all the dimensions laid out. Contributions by all relevant stakeholders and State governments would promote better understanding of the social-ecological system including insights into its status, the opportunities it provides and the pressures it faces. Through genuine engagement, roles and responsibilities in achieving set objectives can also be detailed, agreed upon and committed to, thus building the sense of ownership of the policy by the relevant actors. Subsequent periodic reevaluation and revision of the policy through the Forum, when coupled with responsive institutions, would help CARICOM nimbly and adaptively manage its marine space and resources into the future (Bork Citation2021).

To further advance intersectoral and spatial integration some have suggested, despite CARICOM being geographically fragmented, making transboundary implementation of MSP a region-wide practice. The Eastern Caribbean sub-region is more progressive in this respect compared to the rest of CARICOM (OECS Citation2020). Of course, a helpful proviso for effective MSP and indeed, intersectoral integration, is for individual sectors to have clarity in and of themselves, of their policies, plans and strategic direction. Regional sectoral organizations, such as those proposed in Section 6, are thus valuable in this respect as well as the conduct of strategic environmental assessments for their respective programmes (Fundingsland Tetlow and Hanusch Citation2012).

Regarding intergovernmental integration, uptake and implementation of regional prescriptions by nation States, has at times been slow (Lewis Citation2020). Interviewees have suggested increased capacity development efforts and also, where appropriate, making more use of the dispute resolution provisions of the Revised Treaty including the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) in seeking judicial reliefFootnote8. In addition to interpretation of legal and policy documents of the Community, the Court may become more active in pronouncing on and codifying Community practice and norms (Caserta and Madsen Citation2016).

On improving the science-policy interface, in addition to the CCMS that was proposed above, practices and other ideas applicable to the wider Caribbean region are discussed in more detail in Mahon and Fanning (Citation2021).

It will be resource intensive for the region to facilitate inclusive policy development, build capacity of existing organizations and create and resource new organizations in efforts to strengthen and invigorate regional ocean governance within CARICOM. In the past, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) – International Waters programme has been keen to fund regional integration initiatives and CARICOM could look toward them as a possible funding partner to aid in the transformation of the ocean governance landscape (Söderbaum and Granit Citation2014). The Commonwealth is another potentially worthwhile collaborator and benefactor. With fourteen of the fifteen CARICOM Member States also being members of the Commonwealth, and with blue economy being one of the core focus areas of the Commonwealth Blue CharterFootnote9, the Climate Finance Access Hub of the CommonwealthFootnote10 could be tapped by CARICOM to facilitate human, institutional and technical capacity development in ocean management. Alongside these conceivable partners, the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) may also be a willing and able ally especially as it relates to encouraging private sector investment in the blue economy through innovative financing mechanisms (Ram Citation2018; Tirumala and Tiwari Citation2020).

It is worth noting that CARICOM has been reluctant to establish and support new organizations under its ambit primarily because of costs. However, this paper has proposed them because the analysis demonstrates their need. To address resource constraints, it may be necessary to prioritize these proposals. It is important to strategize on where the group’s main interests and extra-regional standing would most benefit from a strong CARICOM organization while, at the same time, consider how other less important objectives outlined might be achieved via the existing and emerging coordination mechanisms like the CLME/PROCARIBE + Initiative.

Ocean management integration challenges are apparent worldwide (Mahon and Fanning Citation2019b), but efforts and initiatives geared toward improvements are ongoing, including in other SIDS regions (Vince et al. Citation2017). This paper has highlighted where CARICOM can enhance its approach, but also emphasizes some of the region’s progressive arrangements that could be adapted and applied elsewhere across the globe. Cross-regional learning must be enhanced. The COVID-19 pandemic has had considerable impacts on the Caribbean, weakening already fragile economies (Byron et al. Citation2021). As the region emerges from the global pandemic however, making investments in sustainability, enhanced coordination and cooperation and deeper integration in ocean management can see CARICOM “build back better” and more resilient (United Nations Citation2020). Perpetuating comprehensive and cohesive blue economy development should be at the forefront.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of a PhD research project under the “Land-to-Ocean Leadership Programme” at the World Maritime University (WMU) – Sasakawa Global Ocean Institute, Malmö, Sweden. The author would like to acknowledge the generous funding of the Institute by The Nippon Foundation, as well as the financial support of the Programme provided by the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (SwAM) and the German Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure. Hamish Asmath must be thanked for his map work. Sincere gratitude is also extended to Ronan Long, Meinhard Doelle, Robin Mahon, Rahanna Juman, Eric Laschever and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and insights that improved the manuscript.

Notes

1 https://www.unenvironment.org/cep/ (accessed 13th January, 2021).

2 https://clmeplus.org/ (accessed 13th January, 2021).

3 https://www.caribbeanchallengeinitiative.org/ (accessed 13th January, 2021).

4 Address by Dr Carla Barnett on the occasion of her installation as Secretary General of CARICOM: https://caricom.org/i-am-here-to-serve-caricom-secretary-general-dr-carla-barnett/ (accessed: 13th September 2021).

5 For more information: https://www.stabroeknews.com/2021/01/22/business/jamaica-set-to-get-caricom-more-global-oil-and-gas-attention/ (accessed: 2nd February 2021).

6 For more information: https://www.isa.org.jm/news/isa-council-approves-blue-minerals-jamaica-limiteds-plan-work-exploration-polymetallic-nodules (accessed: 2nd February 2021).

7 For more information: https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1134965/Top-10-flag-states-2020 (accessed: 3rd February 2021).

8 The CCJ is the judicial organ of CARICOM with compulsory and exclusive authority in interpreting and applying the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas and decisions taken by its organs (Bravo, Citation2005).

9 The Commonwealth Blue Charter is an agreement by all Commonwealth countries to actively cooperate to solve ocean-related problems and meet commitments for sustainable ocean development. For more information: https://bluecharter.thecommonwealth.org/ (accessed: 1st March 2021).

10 For more information on the Commonwealth Climate Finance Access Hub: https://thecommonwealth.org/climate-finance-access-hub (accessed: 1st March 2021).

References

- Allison, E. H., and H. R. Bassett. 2015. Climate change in the oceans: Human impacts and responses. Science (New York, N.Y.) 350 (6262):778–82.

- Bennett, N. J., J. Blythe, C. S. White, and C. Campero. 2021. Blue growth and blue justice: Ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy. Marine Policy 125:104387. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104387.

- Bennett, N. J., A. M. Cisneros-Montemayor, J. Blythe, J. J. Silver, G. Singh, N. Andrews, … U. R. Sumaila. 2019. Towards a sustainable and equitable blue economy. Nature Sustainability 2 (11):991–93.

- Blake, B. 1998. A strategy for cooperation in sustainable oceans management and development, Commonwealth Caribbean. Marine Policy 22 (6):505–13. doi: 10.1016/S0308-597X(98)00025-6.

- Boesch, D. F. 1999. The role of science in ocean governance. Ecological Economics 31 (2):189–98. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00078-6.

- Bond, P. 2019. Blue economy threats, contradictions and resistances seen from South Africa. Journal of Political Ecology 26 (1):341–62. doi: 10.2458/v26i1.23504.

- Boopsingh, T. M., & McGuire, G. (Eds.). 2014. From oil to gas and beyond: A review of the Trinidad and Tobago model and analysis of future challenges. University Press of America: Lanham, MD.

- Bork, K. 2021. Governing nature: Bambi law in a Wall-E world. Boston College Law Review 62 (1):155.

- Bravo, K. E. 2005. CARICOM, the myth of sovereignty, and aspirational economic integration. North Carolina Journal of International Law 31:145.

- Brondizio, E. S., E. Ostrom, and O. R. Young. 2009. Connectivity and the governance of multilevel social-ecological systems: The role of social capital. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 34 (1):253–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.environ.020708.100707.

- Bryan, A. T. 2009. Petrocaribe and CARICOM: Venezuela’s Resource Diplomacy and its Impact on Small State Regional Cooperation. In: The Diplomacies of Small States (143–59). Palgrave Macmillan: London.

- Byron, J., J. L. Martinez, A. Montoute, and K. Niles. 2021. Impacts of COVID-19 in the Commonwealth Caribbean: Key lessons. The Round Table 110 (1):99–119. doi: 10.1080/00358533.2021.1875694.

- Cairney, P. 2019. Understanding public policy—Theories and issues. Red Globe Press: London.

- Cannonier, C., and M. G. Burke. 2019. The economic growth impact of tourism in Small Island Developing States—Evidence from the Caribbean. Tourism Economics 25 (1):85–108. doi: 10.1177/1354816618792792.

- Carver, R. 2019. Resource sovereignty and accumulation in the blue economy: The case of seabed mining in Namibia. Journal of Political Ecology 26 (1):381–402. doi: 10.2458/v26i1.23025.

- Caserta, S., and M. R. Madsen. 2016. Between community law and common law: The rise of the Caribbean Court of Justice at the intersection of regional integration and post-colonial legacies. Law and Contemporary Problems 79:89.

- Cicin-Sain, B. R. W. Knecht, R. Knecht, D. Jang, and G. W. Fisk. 1998. Integrated coastal and ocean management: Concepts and practices. Island press: Washington, DC.

- Cicin-Sain, B., D. Vanderzwaag, and M. C. Balgos. (Eds.). 2015. Routledge Handbook of National and Regional Ocean Policies. Routledge: Abingdon.

- Claudet, J., L. Bopp, W. W. Cheung, R. Devillers, E. Escobar-Briones, P. Haugan, J. J. Heymans, V. Masson-Delmotte, N. Matz-Lück, P. Miloslavich, et al. 2020. A roadmap for using the UN decade of ocean science for sustainable development in support of science, policy, and action. One Earth 2 (1):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2019.10.012.

- Clegg, P. J. Cumberbatch, and K. Degia. 2020a. Tourism in the Caribbean and the blue economy: Can the two be aligned? In: The Caribbean blue economy. Clegg, P., Mahon, R., McConney, P., & Oxenford, H. A. (Eds.). Routledge: Abingdon.

- Clegg, P. R. Mahon, P. McConney, and H. A. Oxenford. 2020b. Blue economy opportunities and challenges for the wider Caribbean. In: The Caribbean blue economy. Clegg, P., Mahon, R., McConney, P., & Oxenford, H. A. (Eds.). Routledge: Abingdon.

- Compton, S. P. McConney, I. Monnereau, B. Simmons, and R. Mahon. 2020. Good practice guidelines for successful National Intersectoral Coordination Mechanisms (NICs): Second Edition. Report for the UNDP/GEF CLME + Project (2015-2020). CERMES Technical Report. No. 88 2nd. Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies, The University of the West Indies: Cave Hill Campus, Barbados, 21. pp.

- Connell, J. 2013. Islands at risk?: Environments, economies and contemporary change. Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham.

- CRFM 2013. CRFM Second Strategic Plan (2013-2021). CRFM Administrative Report, 35. pp. Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism Secretariat: Belize City. http://www.crfm.int/images/CRFM_Strategic_Plan_updated_30_Jan_2015_FINAL_Online_version-signed_2.pdf. (accessed: 1st March 2021).

- Debels, P., L. Fanning, R. Mahon, P. McConney, L. Walker, T. Bahri, M. Haughton, K. McDonald, M. Perez, S. Singh-Renton, et al. 2017. The CLME + Strategic Action Programme: An ecosystems approach for assessing and managing the Caribbean Sea and North Brazil Shelf large marine ecosystems. Environmental Development 22:191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2016.10.004.

- Douvere, F. 2008. The importance of marine spatial planning in advancing ecosystem-based sea use management. Marine Policy 32 (5):762–71. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2008.03.021.

- Dundas, S. J., A. S. Levine, R. L. Lewison, A. N. Doerr, C. White, A. W. E. Galloway, C. Garza, E. L. Hazen, J. Padilla-Gamiño, J. F. Samhouri, et al. 2020. Integrating oceans into climate policy: Any green new deal needs a splash of blue. Conservation Letters 13 (5):e12716. doi: 10.1111/conl.12716.

- Elliott, M., Á. Borja, and R. Cormier. 2020. Managing marine resources sustainably: A proposed integrated systems analysis approach. Ocean & Coastal Management 197:105315. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105315.

- FAO 2013. Report of the FAO/CRFM/WECAFC Caribbean Regional Consultation on the Development of International Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries. Kingston, Jamaica, 6–8 December 2012. Fisheries and Aquaculture Report, No. 1033, 41. pp. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy.

- Fanning, L, and R. Mahon. 2020. Regional ocean governance: An imperative for addressing blue economy challenges and opportunities in the Wider Caribbean. In: The Caribbean Blue Economy. Clegg, P., Mahon, R., McConney, P., & Oxenford, H. A. (Eds.). Routledge: Abingdon.

- Fanning, L., R. Mahon, S. Compton, C. Corbin, P. Debels, M. Haughton, S. Heileman, N. Leotaud, P. McConney, M. P. Moreno, et al. 2021. Challenges to implementing regional ocean governance in the wider Caribbean region. Frontiers in Marine Science 8:286. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.667273.

- Fundingsland Tetlow, M., and M. Hanusch. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 30 (1):15–24. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2012.666400.

- Gunn, J. H., and B. F. Noble. 2009. A conceptual basis and methodological framework for regional strategic environmental assessment (R-SEA). Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 27 (4):258–70. doi: 10.3152/146155109X479440.

- Haraksingh, I. 2020. Renewable energy: An emerging blue economy sector. In: The Caribbean blue economy. Clegg, P., Mahon, R., McConney, P., & Oxenford, H. A. (Eds.). Routledge: Abingdon.

- Harden-Davies, H. M. Vierros, J. Gobin, M. Jaspars, S. von der Porten, A. Pouponneau, and K. Soapi. 2020. Science in Small Island Developing States: Capacity Challenges and Options relating to Marine Genetic Resources of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. Report for the Alliance of Small Island States. University of Wollongong: Wollongong.

- Hassanali, K. 2018. Approaching the implementing agreement to UNCLOS on biodiversity in ABNJ: Exploring favorable outcomes for CARICOM. Marine Policy 98:92–6. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.09.030.

- Hassanali, K. 2020. CARICOM and the blue economy—Multiple understandings and their implications for global engagement. Marine Policy 120:104137. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104137.

- Haughton, M. 2005. Some thoughts on hammering out a CARICOM Common Fisheries Policy. The Biannual Newsletter of the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism, Issue No. 4. CRFM, Belize.

- Haughton, M. O., R. Mahon, P. McConney, G. A. Kong, and A. Mills. 2004. Establishment of the Caribbean regional fisheries mechanism. Marine Policy 28 (4):351–9. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2003.08.002.

- Hollowed, A. B., M. Barange, V. Garçon, S-I. Ito, J. S. Link, S. Aricò, H. Batchelder, R. Brown, R. Griffis, and W. Wawrzynski. 2019. Recent advances in understanding the effects of climate change on the world’s oceans. ICES Journal of Marine Science 76 (6):1215–220. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsz162.

- Hunter, T, and M. Taylor. 2014. Deep seabed mining in the South Pacific. A background paper. Centre for International Minerals and Energy Law: Brisbane.

- IPCC. 2019. IPCC special report on the ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate, H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (Eds.)]. In press.

- Jean-Marie, D. 2020. The role of shipping and marine transport in developing blue economies. In: The Caribbean blue economy. Clegg, P., Mahon, R., McConney, P., & Oxenford, H. A. (Eds.). Routledge: Abingdon.

- Keen, M. R., A. M. Schwarz, and L. Wini-Simeon. 2018. Towards defining the blue economy: Practical lessons from Pacific ocean governance. Marine Policy 88:333–41. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.002.

- Kimbal, L. A. 1993. UNCED and the oceans agenda: The process forward. Marine Policy 17 (6):491–500. doi: 10.1016/0308-597X(93)90012-R.

- Levin, L. A., D. J. Amon, and H. Lily. 2020. Challenges to the sustainability of deep-seabed mining. Nature Sustainability 3 (10):784–94. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-0558-x.

- Lewis, P. 2020. The challenging path to Caribbean integration. Current History 119 (814):54–9. doi: 10.1525/curh.2020.119.814.54.

- Lodge, M. 2017. The International Seabed Authority and deep seabed mining. UN Chronicle 54 (2):44–6. doi: 10.18356/ea0e574d-en.

- Mahon, R., and L. Fanning. 2019a. Regional ocean governance: Polycentric arrangements and their role in global ocean governance. Marine Policy 107:103590. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103590.

- Mahon, R., and L. Fanning. 2019b. Regional ocean governance: Integrating and coordinating mechanisms for polycentric systems. Marine Policy 107:103589. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103589.

- Mahon, R., and L. Fanning. 2021. Scoping science-policy arenas for regional ocean governance in the wider Caribbean region. Frontiers in Marine Science 8:753. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.685122.

- Mohan, P., E. Strobl, and P. Watson. 2021. Innovation, market failures and policy implications of KIBS firms: The case of Trinidad and Tobago’s oil and gas sector. Energy Policy 153:112250. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112250.

- McCalla, R., B. Slack, and C. Comtois. 2005. The Caribbean basin: Adjusting to global trends in containerization. Maritime Policy & Management 32 (3):245–61. doi: 10.1080/03088830500139729.

- McConney, P., L. Fanning, R. Mahon, and B. Simmons. 2016a. A first look at the science-policy interface for ocean governance in the wider Caribbean region. Frontiers in Marine Science 2:119. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2015.00119.

- McConney, P., T. Phillips, M. Lay, and N. Nembhard. 2016b. Organizing for good fisheries governance in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM). Social & Economic Studies 65 (1):57–85.

- McConney, P. I. Monnereau, B. Simmons, and R. Mahon. 2016c. Report on the Survey of National Intersectoral Coordination Mechanisms. CERMES Technical Report No. 84. Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies, The University of the West Indies: Cave Hill Campus, Barbados. 75. pp.

- Muñoz, J. M. B. 2020. Progress of coastal management in Latin America and the Caribbean. Ocean & Coastal Management 184:105009.

- O’Brien, D. 2011. CARICOM: Regional integration in a post-colonial World. European Law Journal 17 (5):630–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0386.2011.00570.x.

- OECS. 2020. We are large ocean states: Blue economy and ocean governance in the Eastern Caribbean. OECS Commission: Castries, St. Lucia.

- Oxenford, H. A, and P. McConney. 2020. Fisheries as a key component of blue economies in the Wider Caribbean. In: The Caribbean blue economy. Clegg, P., Mahon, R., McConney, P., & Oxenford, H. A. (Eds.). Routledge: Abingdon.

- Panelli, L. F. 2019. Is Guyana a new oil El Dorado? The Journal of World Energy Law & Business 12 (5):365–8. doi: 10.1093/jwelb/jwz022.

- Patil, P. G. J. Virdin, S. M. Diez, J. Roberts, and A. Singh. 2016. Toward a blue economy: A promise for sustainable growth in the Caribbean. The World Bank: Washington, DC.

- Pendleton, L., K. Evans, and M. Visbeck. 2020. Opinion: We need a global movement to transform ocean science for a better world. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (18):9652–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005485117.

- Ram, J. 2018. Financing the blue economy: A Caribbean development opportunity. The Caribbean Development Bank: Barbados.

- Roberts, S., J. N. Telesford, and J. V. Barrow. 2016. Navigating the Caribbean archipelago: An examination of regional transportation issues. In G. Baldacchino (Ed.)Archipelago Tourism: Policies and Practices, pp. 147–62.

- Rochette, J., R. Billé, E. J. Molenaar, P. Drankier, and L. Chabason. 2015. Regional oceans governance mechanisms: A review. Marine Policy 60:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.05.012.

- Ross, M. L. 2015. What have we learned about the resource curse? Annual Review of Political Science 18 (1):239–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-052213-040359.

- Roy, A. 2019. Blue economy in the Indian Ocean: Governance perspectives for sustainable development in the region. Observer Research Foundation Occasional Paper No. 181. https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/ORF_Occasional_Paper_181_Blue_Economy.pdf.

- Ryabinin, V., J. Barbière, P. Haugan, G. Kullenberg, N. Smith, C. McLean, A. Troisi, A. Fischer, S. Aricò, T. Aarup, et al. 2019. The UN decade of ocean science for sustainable development. Frontiers in Marine Science 6:470. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00470.

- Salpin, C., V. Onwuasoanya, M. Bourrel, and A. Swaddling. 2018. Marine scientific research in pacific small island developing states. Marine Policy 95:363–71. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.07.019.

- Séraphin, H., V. Gowreesunkar, P. Roselé-Chim, Y. J. J. Duplan, and M. Korstanje. 2018. Tourism planning and innovation: The Caribbean under the spotlight. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 9:384–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.03.004.

- Silver, J. J., N. J. Gray, L. M. Campbell, L. W. Fairbanks, and R. L. Gruby. 2015. Blue economy and competing discourses in international oceans governance. The Journal of Environment & Development 24 (2):135–60. doi: 10.1177/1070496515580797.

- Singh, G. G., M. Oduber, A. M. Cisneros-Montemayor, and J. Ridderstaat. 2021. Aiding ocean development planning with SDG relationships in Small Island Developing States. Nature Sustainability 4 (7):573–82.

- Smith-Godfrey, S. 2016. Defining the blue economy. Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India 12 (1):58–64. doi: 10.1080/09733159.2016.1175131.

- Söderbaum, F, and J. Granit. 2014. The political economy of regionalism: The relevance for transboundary waters and the Global Environment Facility. In: Ulf Johansson Dahre (Ed.) Resources, peace and conflict in the Horn of Africa: A report on the 12th Horn of Africa Conference, Lund, Sweden, August 23–25, 2013, 109. Lund University: Lund, Sweden.

- Soma, K., J. van Tatenhove, and J. van Leeuwen. 2015. Marine Governance in a European context: Regionalization, integration and cooperation for ecosystem-based management. Ocean & Coastal Management 117:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.03.010.

- Tanaka, Y. 2016. A dual approach to ocean governance: The cases of zonal and integrated management in international law of the sea. Routledge: Abingdon.

- Tirumala, R. D., and P. Tiwari. 2020. Innovative financing mechanism for blue economy projects. Marine Policy 139:104194.

- Tudela, F. 2020. Obstacles and opportunities for moratoria on oil and gas exploration or extraction in Latin America and the Caribbean. Climate Policy 20 (8):922–30. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2020.1760772.

- United Nations. 2020. Policy brief: The impact of Covid-19 on Latin America and the Caribbean. p. 25. https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/EN_SG-Policy-Brief-COVID-LAC.pdf.

- Visbeck, M. 2018. Ocean science research is key for a sustainable future. Nature Communications 9 (1):1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03158-3.

- Voyer, M., G. Quirk, A. McIlgorm, and K. Azmi. 2018. Shades of blue: What do competing interpretations of the blue economy mean for oceans governance? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 20 (5):595–616. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2018.1473153.

- Vierros, M, and C. De Fontaubert. 2017. The potential of the blue economy: Increasing long-term benefits of the sustainable use of marine resources for small island developing states and coastal least developed countries (No. 115545), 1–50. The World Bank: Washington DC.

- Vince, J., E. Brierley, S. Stevenson, and P. Dunstan. 2017. Ocean governance in the South Pacific region: Progress and plans for action. Marine Policy 79:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.02.007.

- Walther, Y. M., and C. Mölmann. 2014. Bringing integrated ecosystem assessments to real life: A scientific framework for ICES. ICES Journal of Marine Science 71 (5):1183–6. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fst161.

- Winther, J.-G., M. Dai, T. Rist, A. H. Hoel, Y. Li, A. Trice, K. Morrissey, M. A. Juinio-Meñez, L. Fernandes, S. Unger, et al. 2020. Integrated ocean management for a sustainable ocean economy. Nature Ecology & Evolution 4 (11):1451–8.

- Wright, G. S. Schmidt, J. Rochette, J. Shackeroff, S. Unger, Y. Waweru, … A. Müller. 2017. Partnering for a sustainable ocean: The role of regional ocean governance in implementing SDG14. PROG: IDDRI, IASS, TMG & UN Environment. https://www.iddri.org/sites/default/files/import/publications/online_iass_report_report_170524.pdf.

- Zwinge, T. 2011. Duties of flag states to implement and enforce international standards and regulations-and measures to counter their failure to do so. Journal of International Business and Law 10:297.