ABSTRACT

The U.S. online program manager (OPM) market has grown substantially in the past decade, as many colleges and universities have sought third-party servicers to help expand and develop their online offerings. Yet, the approach of contracting with OPMs has raised concerns of policymakers, think tanks, higher education critics, and even some campus leaders – with discussions and advocacy of federal policy changes governing higher education’s use of third-party servicers. To understand why universities engage with these for-profit companies, despite the extensive criticisms they have received, we examined the drivers to outsource with OPMs as an organizational strategy. Findings suggest four primary drivers that comprise the College Curation Strategy Framework: react to competitive pressures with speed; access initial, upfront capital; address gaps in capacity and capabilities; and learn and scale-up in house. This framework may help guide decision making when HEIs consider outsourcing. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Introduction

For decades, outsourcing has been a common practice within higher education, as colleges and universities have turned to for-profit companies to provide services at a reduced cost or a higher quality than what they are capable of offering (K. Powers, Citation2019). As a higher education practice, the term outsourcing tends to be a catchall reference for various types of privatization, and there is little consensus over which types of relationships qualify as outsourcing. Early definitions emphasize the contractual nature of outsourcing in higher education, framing it as a “decision to contract with an external organization to provide a traditional campus function or service” (Phipps & Merisotis, Citation2005, p. 1) that is usually “at less cost and/or of superior quality than the university” is able to provide (Gupta et al., Citation2005, p. 397). While these arrangements vary in myriad ways, including services provided and length of the agreement, campuses have historically focused on outsourcing auxiliary services, such as bookstores, dining, student housing, financial and information technology services, and learning management systems (Phipps & Merisotis, Citation2005; K. Powers, Citation2019; Quigley & Pereira, Citation2011). Though less common, outsourcing also occurs with aspects closer to the core of an organization’s academic mission, such as outsourcing instruction with part-time faculty (Schibik & Harrington, Citation2004) or independent firms (Bailey et al., Citation2004), academic development offerings for faculty and staff (Dickson et al., Citation2017), student supports and supplementary academic services (e.g., tutoring, grading, course and program design, and online instruction; Russell, Citation2010), extramural learning experiences like study abroad (Barkin, Citation2018; Whalen, Citation2008), and career counseling (Blumenstyk, Citation2019).

Despite the varied nature and long-standing history of outsourcing, there are considerable concerns about the practice’s effects on organizations and students. Kezar et al. (Citation2019) argue that outsourcing and its associated labor practices have transformed higher education into a Gig Academy, which they describe as an extension of the Gig Economy and neoliberalism, as well as a threat to academic freedom, shared governance, community development, and student experiences and outcomes. Wekullo (Citation2017) summarizes similar common concerns, noting that they include “losing control and ability to manage the service; inconsistency in the quality of service; displacement of employees or low employee morale; loss of identity, community, culture and collegiality; and decrease in salaries and benefits for employees” (p. 454). While these concerns may apply to many different types of outsourcing, they are particularly applicable to areas that are considered fundamental to the core of the organization’s academic mission, such as teaching and learning. One such type of outsourcing, contracting with online program managers (OPMs) to grow online programming, has rapidly expanded in recent years and represents a stark change from the commonly found outsourced auxiliary services of bookstore or food service contracts. This approach, as an organizational strategy, has raised concerns of policymakers, think tanks, higher education critics, and even some campus leaders – with discussions and advocacy of federal policy changes governing higher education’s use of third-party servicers (see, e.g., Dudley et al., Citation2021; Weisman, Citation2023).

Online program managers

Despite the rapid expansion of online program managers, consensus on what exactly qualifies a company as an OPM remains elusive. We believe the most useful definition comes from Cheslock et al. (Citation2021) who define OPMs as companies entering into agreements with colleges and universities to provide “a suite of services that leads the external provider to participate in the management of an online program” (p. 7). OPM services might include varied combinations among marketing, recruitment, instructional design, faculty and student technical support, course development, and student retention, among other services. Thus, while some services provided by OPMs may be considered auxiliary, such as marketing and recruitment, others contain elements of the academic core and have historically been conducted exclusively in-house, such as instructional design and student retention supports. While it could be argued that adjunct professors are a type of academic core outsourcing (Kezar et al., Citation2019), policymakers and other oversight units have not regulated or scrutinized this form of outsourcing to the same degree as OPMs. This distinction might be due to the differences between an adjunct contract with a single individual and the far more extensive, and expensive, OPM contracts with for-profit companies. Moreover, an important distinction between OPMs and other forms of outsourcing is that payments to OPMs frequently vary based on the number of students they enroll. That is, OPM services are provided to colleges and universities through either short-term fee-for-service arrangements or, and historically more commonly, lengthy revenue-sharing contracts, the latter of which can last for 10 years or more and has expanded to be nearly as common as the bookstore outsourcing of the past (Sun & Turner, Citation2022).

Yet rather than being a panacea for the challenges of growing online education, OPMs have received considerable scrutiny. The federal government, think tanks, and media outlets have questioned the practices of these companies. Critics of OPMs point to the interrelationship of internal versus external control of online programs, the need for buy-in and inclusive decision-making, predatory recruitment practices targeted at marginalized students, minimal student data protections, perceived disconnects between the missions of nonprofit universities and for-profit OPMs, and resulting concerns with quality (Blumenstyk, Citation2019; Cheslock et al., Citation2021; Hall & Dudley, Citation2019; Hamilton et al., Citation2024; Kim & Maloney, Citation2020; Kowalewski & Hortman, Citation2019; Ortagus & Derreth, Citation2020; Ramani et al., Citation2022).

Concerns about OPM operations have grown to such a degree that the U.S. Department of Education (ED) recently issued a Dear Colleague Letter (DCL) calling for expanded regulation and oversight of all third-party servicers (TPS; Weisman, Citation2023). Under a preliminary guidance, which has since been rescinded for further negotiated regulatory comments, TPSs are defined as “any entity or individual that administers any aspect of an institution’s participation in the Title IV programs” (Weisman, Citation2023, Third Party Servicer Definition and Activities), and thus the range of TPSs affected by the guidance extends beyond OPMs to include other educational technology companies, such as learning management systems (e.g., Blackboard) and enterprise resource planning systems (e.g., Oracle). Among other issues, this DCL was largely criticized for the overly broad inclusion of all TPSs when many saw the guidance as primarily being driven by a desire to extend oversight of OPMs (Cumming, Citation2023). Although the regulations are not finalized, the DCL created an uproar in the education technology community, including among Educause (O’Brien, Citation2023) and the American Council on Education (Mitchell, Citation2023). The criticisms of the DCL were so extensive that ED rescinded the guidance and indicated they will likely issue new recommendations in 2024 (Kvaal, Citation2023). Nevertheless, the initial guidance portends to the degree of ED’s policy concerns around OPM accountability and transparency.

This policy shift toward greater regulation calls attention to the underexamined nature of outsourcing in higher education. It further highlights concerns about outsourcing elements of the academic core to third-party servicers, as the outsourcing of auxiliary services on campus (e.g., housing, dining services) has not been subject to the same level of scrutiny. At the same time, recent data suggest that many colleges and universities are engaging in this form of outsourcing. As of 2021, at least 550 colleges and universities were working with OPMs to support over 2,900 academic programs (Emrey-Arras, Citation2022). The prevalence that for-profit companies have in the organizational strategies of colleges and universities, paired with the considerable concerns related to their business practices, raises questions as to why universities would choose to engage in these types of outsourcing arrangements.

Study purpose

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the drivers of university outsourcing considerations as an organizational strategy. To accomplish this purpose, we asked: What were the driving reasons that universities, as reported from their Chief Online Learning Officers (COLOs), strongly considered outsourcing of their online programs through online program managers using a revenue share arrangement as an organizational strategy?

Literature review

There is a paucity of research about outsourcing in higher education, and empirical examinations of OPMs are even more scarce. To aid in our discussion of strategic outsourcing, we thus turn to the fields of management and organizational studies to consider potential theoretical inquiries to examine universities’ strategic drivers to use OPMs. Specifically, we explore the Planning School, the Positioning School, the Institutional Perspective, and Resource-Based View. The organizational strategy schools of thought discussed here are neither always fully distinct from each other nor in all cases explicitly stated in the literature. Instead, these schools represent an overview of commonly employed organizational strategy perspectives for examining outsourcing.

The planning school

The Planning School arose in the 1970s from a flood of articles, both popular and academic, “extolling the virtues of formal ‘strategic planning’” (Mintzberg et al., Citation2009, p. 47). This highly formalized approach views organizational strategy as emerging “full blown” from deliberate planning processes broken down into distinct steps, and overseen by professional planners and strategists, with the assumed benefit of increasing predictability in inputs, processes, and outcomes. Johnson and Graman (Citation2015), for example, examined the outsourcing of auxiliary services at seven public universities in the Midwestern United States. They assert that “from the start it is essential to assess and identify the factors involved in outsourcing before pursuing the effort” because “one of the overarching components of successful outsourcing is formulating a strategic operations plan” (p. 271). Accordingly, the Planning School offers researchers purposeful congruence between outputs, design, preparation considerations, and outsourcing strategy.

The positioning school

In the 1980s, influences from economics, and particularly the work of Harvard economist Michael Porter, introduced an emphasis on more macro, market-level considerations in strategy formation than had been standard in formal strategic planning up to that time (Mintzberg et al., Citation2009). According to Cooper et al. (Citation2005) the Positioning School “focuses primarily on … analysis of the nature and dynamics of competitive advantage” (p. 214) which organizations seek “in terms of industry position” (p. 333). An illustrative example comes from Gupta et al. (Citation2005) who quantitatively surveyed senior leaders at all private and public colleges of higher education in three U.S. states concerning the outsourcing of a variety of non-instructional services and found that “the vast majority of institutions in all three states surveyed hold on to the concept of outsourcing according to their position in the system” (pp. 409–410). By examining the market placement effects to outsourcing as a driver of organizational strategy, the Positioning School is useful when focusing on competitive efforts and industry standing.

The institutional perspective

Like the Positioning School, institutional theorists examine external influences to explain organizational strategy. However, whereas the Positioning School typically analyzes the economic factors that organizations consider to gain a competitive advantage, institutionalists interrogate how social influences shape organizations as they pursue legitimacy and prestige (Chu et al., Citation2018). The Institutional Perspective is “based on the premise that [organizational] choices,” such as outsourcing strategies, “are not merely rational economic decisions but are also strongly influenced by external norms, values, and traditions” (Chu et al., Citation2018, p. 393). Adopting this perspective, Gumport (Citation2000) scrutinized how higher education leaders respond to increased competition and public scrutiny through borrowing new managerial and consumerist legitimating logics from the for-profit sector resulting in a restructuring of the entire academic enterprise and cautioned that such managerial and efficiency-based strategies may ultimately delegitimize the core social and academic functions of higher education.

The resource-based view

The most prevalent perspective in the outsourcing literature, the Resource-Based View (RBV), while still concerned with maintaining a competitive advantage, represents a shift away from external influences and instead focuses on resources internal to the firm (Barney, Citation1991; Grant, Citation1991; Powers, Citation2003). Resources in this view are generally categorized in four ways: financial (capital investments), physical (equipment, technology), human (knowledge, expertise), and organizational (structures and systems; Powers, Citation2003). These resources can lead to a firm’s sustained competitive advantage if they are valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and non-substitutable (Barney, Citation1991). In other words, these resources have the strongest positive impact on an organization if they contribute to the firm’s efficiency and/or effectiveness, are not commonly or easily replicated between competitors, and cannot be easily substituted with other resources.

Among the perspectives used in the organizational strategy literature, the Resource-Based View seems most fitting for this study for several reasons. First, like the RBV lens, the extant literature about OPMs, though rather scant, characterized the role of OPMs in terms of the significant value associated with their services and resources as a central core issue (see e.g., Dalal, Citation2021; Springer, Citation2018). Second, the uniqueness of the service-based offerings from OPMs and the gap it presents to universities as organizations aligns with an RBV inquiry. Third, challenges in internally replicating these services reflects the human and technological resource concerns that fit within an RBV study. Given these reasons, we employed a Resource-Based View to interrogate the reasoning and drivers associated with the universities’ strategic outsourcing choices.

Drivers of outsourcing strategy

Important to any strategic decision are the drivers, or the “motivations, objectives, and goals,” that inform such a decision (Kroes & Ghosh, Citation2009, p. 125). Research about outsourcing in higher education, whether of core or auxiliary functions, yields a relatively consistent inventory of decision-making drivers. For example, studies frequently point to reductions in state and federal funding and associated financial needs as a primary driver for outsourcing arrangements. Yet the specifics of financial motivations are varied and many. In some cases, outsourcing is seen as a method for solving preexisting funding issues or financial pressures or reducing costs (Glickman et al., Citation2007; Gupta et al., Citation2005; Johnson & Graman, Citation2015; Moore, Citation2002; Palm, Citation2001; K. Powers, Citation2019; Quigley & Pereira, Citation2011; Wekullo, Citation2017; Wertz, Citation2000). Phipps and Merisotis (Citation2005) explain that this cost savings can also come in indirect ways or “soft savings” that offer reduced burdens on internal staff (p. 9). Still others identify increased and/or upfront revenue as a reason for outsourcing (Cheslock et al., Citation2021; Glickman et al., Citation2007; Palm, Citation2001; Phipps & Merisotis, Citation2005; Quigley & Pereira, Citation2011; Wertz, Citation2000).

Aside from financial motivations, institutions turn to outsourcing to improve internal organizational functioning. Increasing efficiency and fixing malfunctioning systems or processes are commonly cited reasons for engaging in outsourcing (Johnson & Graman, Citation2015; Moore, Citation2002; Phipps & Merisotis, Citation2005; Quigley & Pereira, Citation2011; Wekullo, Citation2017; Wertz, Citation2000). Institutions may also choose to outsource to expand capabilities, improve quality, or focus efforts on core services (Cheslock et al., Citation2021; Gupta et al., Citation2005; Moore, Citation2002; Palm, Citation2001; Phipps & Merisotis, Citation2005; Quigley & Pereira, Citation2011; Wertz, Citation2000). Studies have also found that institutional leadership may see outsourcing as a means to increase innovative practices and improve strategic planning so they may prepare for future challenges and opportunities (Johnson & Graman, Citation2015; Phipps & Merisotis, Citation2005; Wekullo, Citation2017; Wertz, Citation2000). While less common than other reasons, outsourcing may also be a way for colleges and universities to reduce their risk and liability through sharing this risk with external organizations (Cheslock et al., Citation2021; Gupta et al., Citation2005; K. Powers, Citation2019; Quigley & Pereira, Citation2011).

There are also reasons external to the institution that may cause leadership to consider outsourcing. Most prominently, outsourcing can be a means to gain external knowledge, expertise, or resources that are unavailable internally (Cheslock et al., Citation2021; Moore, Citation2002; Palm, Citation2001; Phipps & Merisotis, Citation2005; Quigley & Pereira, Citation2011; Wekullo, Citation2017; Wertz, Citation2000). Remaining competitive with peers and associated pressures are also reasons for exploring outsourcing possibilities (Gupta et al., Citation2005; Moore, Citation2002; K. Powers, Citation2019). Some institutions may be under pressure from state governing bodies to seek the resources and capabilities they lack through external sources (Gupta et al., Citation2005; K. Powers, Citation2019; Wertz, Citation2000).

Materials and methods

This study initially began as an exploratory mixed methods research study consisting of a survey and individual interviews, reflecting the understudied nature of OPMs structured with a Resource-Based View. Early on as the project developed, we realized that the COLOs’ reflections and responses in the interviews generously offered a robust recount of the outsourcing considerations and arrangements. Accordingly, we pivoted the qualitative components of the study approach and adopted an organizational narrative inquiry through the COLOs’ storytelling (Boje, Citation2008; Feldman et al., Citation2004). As researchers, we recognized this need for adaption as the participants drew our attention to the underlying context, events, outcomes, and evaluation aspects through roles, timing, and structures from a resource lens through a storytelling manner. Organizational storytelling is a method of analysis which “allows researchers to make more available the unstated, implicit understandings that underlie the stories people tell” (Feldman et al., Citation2004, p. 147). In this study, this methodology allowed us to better understand the full scope of the respective university’s strategy and the OPM relationship through the stories the COLOs told.

Data collection

Data for this study were collected as part of a larger examination of the decision-making processes of COLOs as they navigated whether their institutions would engage with online program managers. Our sample came from COLO members of the University Professional Continuing Education Association (UPCEA). Beyond UPCEA membership and COLO role, inclusion criteria necessitated that COLOs’ institutions had online programming for at least the last five years and had considered working with an OPM through a revenue share agreement. These criteria ensured sufficient data to reflect on the strategy and organizational relationships. If the COLOs and institutions met the study criteria, COLOs were contacted through UPCEA’s e-mail networks and invited to complete a survey and subsequently participate in one-on-one interviews. In addition to information on OPM relationship status and institutional characteristics, the survey asked COLOs who had currently or formerly worked with an OPM to rate their level of need for common OPM services (e.g., marketing, upfront capital) and whether these services met their expectations. We ultimately received 92 responses to the survey and interviewed 32 COLOs from universities across the United States. Interviews were conducted virtually, and each interview lasted between 20 and 90 minutes.

Sample

Our purposive sample from UPCEA’s COLO members varied in terms of institutional sector and classification and OPM experience. presents the institutional characteristics of the COLOs who participated in the study, and presents COLOs’ relationships with OPMs. For those COLOs who currently worked with an OPM, further presents whether they worked with multiple companies and the length of these relationships. As shown, we gathered data from individuals who had a range of perspectives and experiences with OPMs.

Table 1. Institutional characteristics.

Table 2. OPM characteristics.

Data analysis

For the survey, data were analyzed using descriptive statistics to generate frequencies among study variables. We further conducted a gap analysis between which services COLOs identified were needed and whether they felt the services met their expectations. This analysis identified OPM services where need exceeds expectations. For the interviews, we analyzed data through template analysis, which is a form of thematic analysis that uses hierarchical coding and provides the flexibility necessary for exploratory research. As part of this approach, we developed a deductive coding template based on the work of several articles that cover outsourcing and OPMs (i.e., Assaf et al., Citation2011; Ball, Citation2003, ; Cheslock et al., Citation2021), and this template allowed us to form a series of a priori codes and groups. After developing the coding template, we used a hypothetico-deductive approach, which involves sorting and grouping data to test assumptions and observation statements, to reveal families and relationships among the data.

Positionality and trustworthiness

In this work, our own positionality entails an organizational orientation through inquiries focused on innovation and fringe topics within higher education, as although OPMs are common across universities and colleges, they remain separate from the organizational core (i.e., on the fringes). We approach the topic from a post-empiricist perspective, acknowledging the free market effects, scientific observations with a realist stance, explanatory value through imperfection (even potentially biases), infusion of an iteratively set of evidence to test claims/assertions, and a high level of awareness to separate epistemological stances of “the knower” and “what is known.” Further, for this study, we recognized the COLOs roles at emphasizing the importance of mission responsiveness, yet with an interest at seeking a competitive advantage within the online learning space. Throughout our analysis, we adopted several strategies to bring trustworthiness to our data. Specifically, these strategies included: (1) having a high number of participants; (2) completing member checking; (3) examining discordant data in a multiple round iterative examination; (4) involving multiple researchers to prod and consider alternative explanations; (5) practicing reflexivity through researcher checks; and (6) auditing data with UPCEA’s Board. Notably, the analytic techniques of template analysis and a hypothetico-deductive approach aided in the trustworthiness checks.

Results

Our primary findings were derived through the interviews with COLOs. Before delving into those findings, we first present findings from the survey portion to provide some brief contextualization of the COLOs experiences with OPMs.

Survey

On the survey, COLOs who currently or formerly worked with OPMs (n = 36) were asked to rate their level of need for common OPM services, as well as whether these services met their expectations. We asked COLOs to rate these items on a 5-point scale, with 0 being “not needed at all” or “substantially below expectations,” and 5 being “absolutely needed/essential” or “significantly exceed expectations,” respectively. We then conducted a gap analysis between the two ratings to identify which services had high levels of need yet were identified as not meeting expectations. presents the level of need for OPM services according to the percentage of COLOs who indicated whether they were not needed (0 or 1 ratings), moderately needed (2 or 3) or highly needed (4 or 5)

presents those services where the level of need exceeded whether expectations were being met for the service. That is, for marketing, COLOs identified that their need for the service was 1.51 points higher than the met expectations for marketing on a 5-point scale.

Taken together, the survey data suggests that COLOs have needs for many of the services provided by OPMs, but also that OPMs may fail to deliver on expected quality levels when providing these services, particularly for the top needed services of marketing and recruiting. We expand on these findings through moving beyond services needed and examining the drivers that led COLOs to consider outsourcing with OPMs.

Interviews

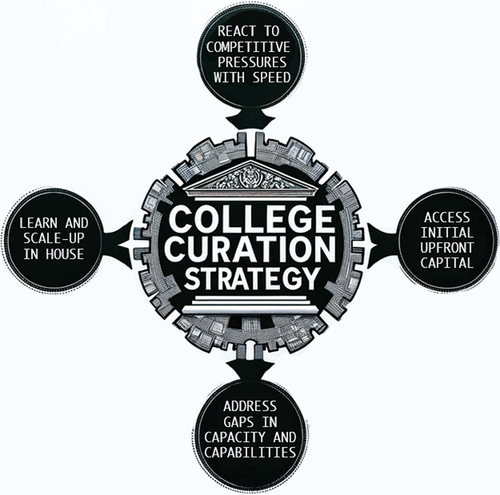

Through the interviews, we identified the most common drivers, or motivations, that led COLOs to consider engaging in an outsourcing engagement with an OPM as an organizational strategy. Collectively, we call these four drivers the College Curation Strategy (CCS) Framework, which as we explain later in this article, reflect the effect among the four drivers as an organizational strategy. The CCS’ components are presented according to the frequency with which COLOs identified each driver, beginning with the most frequent.

React to competitive pressures with speed

The most significant driver emergent from the data is COLOs considering OPMs as a reaction to competitive pressures within the online learning space in a fast pace. The COLOs described how competitive pressures manifested from observing their competitors (or institutional peers) and hearing constant news about mega-universities, and this pressure caused them to enact different online strategies. COLOs described feeling pressured to emulate the successes of these institutions, many of which had an elevated presence in online learning, offered several program options, and provided direct and responsive student supports in a short timeframe. In many cases, the COLOs started to test the tactics they observed and mimicked the competition. For instance, a COLO expressed how “our sister and aspirational institutions” were having successes with OPMs and that COLO believed that his institution also “need[ed] to experiment with playing in what … [its] peers are doing.” Consistently, the COLOs reported that they did not want to be left behind in the competitive arena of online learning, especially as some competitors were growing so rapidly. One COLO asserted that his university was “lagging, in that [their programs] were pretty significantly behind competitors in that space.” For many, they also spoke about moving themselves away from a regional focus to a national, and even international, focus using online learning as an opportunity to extend their institution’s reach. As one COLO described, “it basically was ‘how do we build our national brand?’”

COLOs also revealed reacting to competition by intentionally preparing for future challenges and demographic shifts, such as the predicted 2025 enrollment cliff of high school students available to attend college. To those ends, one COLO stated: “that’s been part of the wake-up call, … if you want to scale your program, and increase and attract more students to the program, [OPMs offer you that possibility].” Many COLOs referenced the need to change practices and expand efforts so they did not miss the opportunity to be present in online learning and fall behind to a point where it would be too late too catch-up. As one COLO expressed, she viewed OPMs as a chance to “really invest in some of our programs.”

Access initial, upfront capital

Another significant driver emergent from the data is COLOs envisioning the use of OPMs as a mechanism to secure and protect the university’s finances. In part, financial motivations were driven through the ability of OPMs to provide access to the initial upfront capital required to launch online programs, which could be millions of dollars a year. As one COLO described, the “cost to get someone enrolled, it’s very much front loaded,” and therefore an OPM arrangement can help defray these early costs. Stated another way, a COLO explained that “partnering with a company that’s willing to front load their work, and then be paid off over time for that work, is very appealing.” Another COLO posed it as: “So … the work to do it happen[ed] before … we were getting any revenue from that experience.” Given challenges with higher education resource allocation and academic prioritization, this approach offers a funding mechanism for developing capacity focused on online growth without having to allocate current, and often scarce, resources to accomplish that goal.

Connected to the upfront capital rationale, the COLOs made reference to “risks,” but largely these remarks related to resources, particularly financial resources. A COLO aptly noted that through the engagement with an OPM, “this is a way that we could bring on a partner who essentially takes a lot of the financial risk – and, financial investment, and helps to drive this enrollment.” The risk shifting to the OPM and away from the university represented an attractive feature for the institutions. At the same time, the COLOs reported that they generally had controls in place to drive the engagement expectations and take ownership of the relationship.

Address gaps in capacity and capabilities

Similar to preparing for future demographic shifts, COLOs reported that they considered using OPMs to help them invest in the future of online learning through addressing gaps in internal capacity and capabilities. One of the most frequently discussed gaps related to marketing and lead generation of applicants, particularly in terms of attracting untapped student populations. Across the interviews, COLOs expressed the value of OPMs as the source for prospective student leads and venues to market their programs. Several COLOs observed that the OPMs had greater expertise and a centralized model where they could pool the universities’ funds for marketing and lead generation. One COLO, who framed the OPM value in a way that echoed throughout the data, put it “So that … part is absolutely essential, helping us actually execute on the marketing, the branding, the awareness, all of that.” The data also showed that COLOs viewed OPMs as generally able to generate leads in program areas or attract audiences in which the university had little to no prior experience attracting. One of the COLOs explained: “asking [our university marketing team] to turn on a dime and go after a completely different persona or personas, for example, in terms of marketing and recruitment, … would be a lot to ask … . We would need to add additional staff and so on and so forth.” The belief or, in many cases, even the actual output, led to the OPMs being able to attract those prospective students to the university as potential applicants.

In some instances, the gaps in online learning capacity and infrastructure capabilities were directly identified or championed by campus or unit leaders. Although the interview data suggest that the COLOs were frequently the catalysts for OPM exploration or relationships, in more than a third of the interviews, the COLOs referenced C-suite or academic administrators who drove the consideration of an OPM to grow online offerings. These positions included the president, provost, and academic deans. For instance, one COLO described the influence of their provost: “we had for the first time someone in a very strong academic position, you know [the] provost is essentially your chief academic officer, who was advocating for online.” Interestingly (though not surprisingly), among these campus leaders at the academic dean level, all were within professions-based units such as business, information technology, engineering, and social work. One COLO characterized the academic deans as holding significant weight in this process: “So it came down very much to the deans – their individual preference and belief in online education … and the value and potential of online education. If the dean didn’t believe in it or … couldn’t be persuaded by others, then it wasn’t going to happen” with having an OPM engage with that unit.

Learn and scale up in-house

While all the COLOs reported lessons that they gained from the OPM engagement or review process, nearly half the universities began this exploration or relationship intending to learn from the OPMs with the expressed interest of figuring out what the university needed to do so it could scale up or operate independently from an OPM. One COLO articulated the purpose of exploring an OPM relation as “wanting to look at how … we [could] better serve those students to so it’s not just about enrollment, but it’s about those wraparound student services that these adult learners [receive from OPMs].” The discussion with several COLOs revolved around how OPMs had certain capabilities and competencies that their universities did not, as is reflected in our third finding, and how the COLOs were uncertain as to what policies, practices, and expectations would need to change so they could develop those capabilities and competencies internally.

Similarly, in some manner or another, all the COLOs spoke about OPMs as a complementary engagement that would help expand and develop current efforts. Nearly a third of the COLOs identified ways in which they could use existing relationships or initiatives, particularly in the area of non-credit learning, with the OPM to advance their market position in a substantial manner. For instance, one COLO mentioned that university team’s conversations about converting learners of nondegree, Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) to online degree students. “You had those students [who] were just taking it for free … and then to get into the degree program, you were probably seeing about 100 applications a year … and they already have advanced credit” so these learners would likely finish. Another university recounted their connecting MOOCs to credits. “We started to get inquiries from students who said, ‘I see a course in the MOOC platform that has the same name, the same faculty member, the same syllabus as what you offer in your course catalog. Can I count it for credit?’” While the conventional answer was “no,” the COLO described her university’s approach: “Our faculty took it upon themselves to say, ‘why not?’ and our faculty [in one program] went a step further, and said, ‘Well, could we actually create a degree in this fashion?’” In several instances among the COLOs we interviewed, the MOOC relationship led to an OPM engagement.

Competition, capital, capacity building, and organizational learning consistently echoed the recordings of our COLOs. These factors played an important part of why COLOs entertained engaging with OPMs. There was general agreement that OPM partnerships can help expedite online growth and attract untapped student populations. They are able to do so both through providing the funding necessary to develop and scale online programs, but also through helping institutions attract untapped student populations and learn how to meet the needs of these students through tailored services and supports. Taken together, these findings comprise the College Curation Strategy (CCS) framework, which is presented in .

Discussion

This paper expands the study of outsourcing in higher education by examining university motivations, or drivers, to outsource via OPMs as an organizational strategy (Cheslock et al., Citation2021). In doing so, we have bridged the higher education literature with strategic planning perspectives from organizational and management studies, illuminating a variant to the Resource-Based View, the College Curation Strategy. Unlike prior empirical investigations of organizational strategy centered around resources, CCS uncovers knowledge development and transfer as a foundational principle driving decision making when HEIs consider outsourcing.

The four components of the CCS echo previous literature about organizational motivations for outsourcing, as we found many commonalities between the drivers identified by COLOs when considering engaging with OPMs and those found in studies related to other forms of outsourcing. Reacting to competitive pressures with speed is directly related to responding to competition from peers (Gupta et al., Citation2005; Moore, Citation2002; K. Powers, Citation2019) and using strategic planning to prepare for future challenges and opportunities (Johnson & Graman, Citation2015; Wekullo, Citation2017). Similarly, accessing initial upfront capital reflects commonly found financial motivations, such as solving preexisting funding issues, increasing revenue, and shifting financial risk (Glickman et al., Citation2007; K. Powers, Citation2019; Quigley & Pereira, Citation2011), while addressing gaps in capacity and capabilities relates to reducing burdens on internal staff (Phipps & Merisotis, Citation2005) and expanding capability and improving quality (Gupta, Citation2005; Phipps & Merisotis, Citation2005).

The final component of the CCS framework, learning and scaling up in-house, was the least commonly identified in previous studies. Although it shares similarities with increasing efficiency and fixing malfunctioning systems or processes (Johnson & Graman, Citation2015; Wekullo, Citation2017), the COLOs described learning from OPMs in a way that surpasses improvements. Rather, they were using the knowledge and expertise of the OPMs to build their internal knowledge of online education in new and innovative ways, thus representing a type of organizational learning. The hidden nature of OPM engagements benefiting COLOs through the CCS framework aligns strongly with RBV’s assertion that resources are more advantageous when the “link between the resources possessed by a firm and a firm’s sustained competitive advantage is casually ambiguous” (Barney, Citation1991, p. 107). In the case of CCS, we see how organizational learning becomes a type of resource that aids in this competitive advantage.

The CCS significantly considers both the organization’s internal resources and capabilities, in line with the Resource-Based View of organizational strategy (Barney, Citation1991), but is also infused with organizational learning motivations, akin to the concept of “knowledge spillover” from economic inquiry, as specifically indicated by driver # 4 “learn and scale up in-house.” Knowledge spillover “occurs when recipient firms,” such as universities, “combine the knowledge of an originating firm,” like OPMs, with their own knowledge and capabilities (Yang & Steensma, Citation2014, p. 1496). While some authors highlight the risks of knowledge spillover when organizations outsource (Hu et al., Citation2020; Mukherji & Ramachandran, Citation2007), COLOs in our study instead saw opportunities to learn and, as one participant put it, eventually “scale up or operate independently” of OPMs. Thus, our inquiry adds broadly to the outsourcing literatures from both higher education and organizational management studies while specifically highlighting the connection to organizational learning in strategic decision making.

Implications

This research begins to build understanding around the OPM decision-making process and suggests several implications for research and practice.

Researchers

Researchers concerned with organizational strategy should consider revisions to these frameworks that account for the CCS framework so that a greater understanding of how current outsourcing arrangements affect organizational strategy may be achieved. Additionally, this study reveals the utility of applying narrative inquiry and organizational storytelling to decision-making within higher education, and future research should explore the use of this methodology. Given the scarcity of research related to OPMs and outsourcing, future research should also delve further into this topic to examine the practices and effects of outsourcing within varied higher education contexts.

Practitioners

Practitioners considering working with OPMs would benefit through including evaluations of “back-housing,” or the plans for internal reintegration of online programs following the end of OPM relationships. Such evaluations might guide colleges and universities as they prepare to operate independently of for-profit contractors, as discussed by the COLOs in our study. Given that this inquiry focused on revenue-share arrangements with OPMs, we further believe practitioners should focus increased attention on other payment structures, cost shifting alternatives, and investment structures. Finally, although our focus here is on OPMs, practitioners should also review other outsourcing arrangements in light of the CCS Framework and evolving federal regulations.

Limitations

This study was limited through our sample population, which came exclusively from UPCEA’s COLO members. There are likely many institutions who engage with OPMs but who do not have a designated COLO role and/or are not members of UPCEA. These institutions were inherently excluded from our sample, yet they likely have valuable insight to contribute to a holistic understanding of the OPM engagement decision process, and future research would benefit from a more varied sample.

Conclusion

As debates over outsourcing with OPMs become more ubiquitous in higher education, the College Curation Strategy (CCS) Framework outlined here represents an initial attempt to bridge this discourse with scholarship on organization strategy. The CCS’ four drivers, or motivations, to engage in a revenue-sharing relationship with OPMs highlight important linkages between economic inquiry and the Resource-Based View (RBV) of strategic planning. While economic models address the acquisition of new knowledge and competencies through knowledge spillover, organizational learning motivations have often been overlooked as a major complement to the RBV perspective on strategy generally and outsourcing specifically. Thus, this work adds to both the literature on outsourcing in higher education and outsourcing as an organizational strategy across sectors. Through its emphasis on organizational learning, the CCS offers deeper insights for organizations seeking to own the outsourcing relationship, build off existing efforts, and potentially reintegrate their online program management initiatives internally. Future research should evaluate the utility of the CCS for offering insights on the drivers to separate from OPM partnerships and back-house online learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Assaf, S., Hassanain, M. A., Al‐Hammad, A. M., & Al‐Nehmi, A. (2011). Factors affecting outsourcing decisions of maintenance services in Saudi Arabian universities. Property Management, 29(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1108/02637471111122471

- Bailey, T. R., Jacobs, J., & Jenkins, P. D. (2004). Outsourcing of instruction at community colleges. Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8DJ5CPP

- Ball, D. (2003). A weighted decision matrix for outsourcing library services. The Bottom Line, 16(1), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/08880450310464036

- Barkin, G. (2018). Either here or there: Short‐term study abroad and the discourse of going. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 49(3), 296–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/aeq.12248

- Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Blumenstyk, G. (2019). College leaders are getting serious about outsourcing. They still have plenty of concerns, too. The chronicle of higher education. https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/the-edge/2019-03-26

- Boje, D. M. (2008). Storytelling organizations. Sage.

- Cheslock, J. J., Kinser, K., Zipf, S. T., & Ra, E. (2021). Examining the OPM: Form, function, and policy implications (pp. 1–52). Pennsylvania State University.

- Chu, Z., Xu, J., Lai, F., & Collins, B. J. (2018). Institutional theory and environmental pressures: The moderating effect of market uncertainty on innovation and firm performance. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 65(3), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1109/tem.2018.2794453

- Cooper, C. L., Argyris, C., & Starbuck, W. H. (Eds.). (2005). The Blackwell encyclopedia of management (2nd ed). Blackwell.

- Cumming, J. (2023). EDUCAUSE and third-party service guidance. Educause. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2023/3/educause-and-third-party-servicer-guidance

- Dalal, A. (2021). Scaling Online Graduate Programs: An Exploratory Study of Insourcing versus Outsourcing [ Doctoral dissertation] University of Southern California. ProQuest Dissertation Publishing.

- Dickson, K., Hughes, K., & Stephens, B. (2017). Outsourcing academic development in higher education: Staff perceptions of an international program. International Journal for Academic Development, 22(2), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2016.1218884

- Dudley, T., Hall, S., Acosta, A., & Laitinen, A. (2021). Outsourcing online higher ed: A guide for accreditors. The Century Foundation. https://tcf.org/content/report/outsourcing-online-higher-ed-guide-accreditors/

- Emrey-Arras, M. (2022). Higher education: Education needs to strengthen its approach to monitoring colleges’ arrangements with online program managers. Report to congressional requesters. GAO-22–104463. US Government Accountability Office.

- Feldman, M. S., Skoldberg, K., Brown, R. N., & Horner, D. (2004). Making sense of stories: A rhetorical approach to narrative analysis. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 14(2), 147–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muh010

- Glickman, T. S., Holm, J., Keating, D., Pannait, C., & White, S. C. (2007). Outsourcing on American campuses. International Journal of Educational Management, 21(5), 440–452. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540710760219

- Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114–135. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166664

- Gumport, P. J. (2000). Academic restructuring: Organizational change and institutional imperatives. Higher Education, 39(1), 67–91. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003859026301

- Gupta, A., Herath, S. K., & Mikouiza, N. C. (2005). Outsourcing in higher education: An empirical examination. International Journal of Educational Management, 19(5), 396–412. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540510607734

- Gupta, A., Kanthi Herath, S., & Mikouiza, N. C. (2005). Outsourcing in higher education: An empirical examination. International Journal of Educational Management, 19(5), 396–412.

- Hall, S., & Dudley, T. (2019). Dear colleges: Take control of your online education. The century foundation. https://tcf.org/content/report/dear-colleges-take-control-online-courses/

- Hamilton, L. T., Daniels, H., Smith, C. M., & Eaton, C. (2024). The for-profit side of public U: University contracts with online program managers. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 10, 10. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231231214952

- Hu, B., Mai, Y., & Pekeč, S. (2020). Managing innovation spillover in outsourcing. Production and Operations Management, 29(10), 2252–2267. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13222

- Johnson, D. M., & Graman, G. A. (2015). Outsourcing practices of midwest US public universities. International Journal of Business Excellence, 8(3), 268–297. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijbex.2015.069146

- Kezar, A., DePaola, T., & Scott, D. T. (2019). The gig academy: Mapping labor in the neoliberal university. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kim, J., & Maloney, E. (2020). Learning innovation and the future of higher education. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kowalewski, S., & Hortman, K. (2019). The impact of online program management (OPM) on the growth of online learning: A case study. Proceedings of the 2019 ICDE World Conference on Online Learning, Dublin, Ireland (pp. 521–529).

- Kroes, J. R., & Ghosh, S. (2009). Outsourcing congruence with competitive priorities: Impact on supply chain and firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 28(2), 124–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.09.004

- Kvaal, J. (2023). Update on the department of education’s third-party servicer guidance. U.S. Department of Education. https://blog.ed.gov/2023/04/update-on-the-department-of-educations-third-party-servicer-guidance/

- Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B. W., & Lampel, J. (2009). Strategy safari: The complete guide through the wilds of strategic management (2nd ed.). FT Publishing International.

- Mitchell, T. (2023, February. 23). Letter to U.S. secretary of education Miguel Cardona. American Council on Education. https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Letter-ED-TPS-Comments-Extension.pdf

- Moore, J. E. (2002). Do corporate outsourcing partnerships add value to student life? New Directions for Student Services, 2002(100), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.69

- Mukherji, S., & Ramachandran, J. (2007). Outsourcing: Practice in search of a theory. IIMB Management Review, 19(2), 103–110.

- O’Brien, J. (2023, March. 7). Letter to U.S. secretary of education Miguel Cardona. Educause Library. https://library.educause.edu/-/media/files/library/2023/3/educause_ed-gen2303-comments_march-7-2023_f.pdf

- Ortagus, J. C., & Derreth, R. T. (2020). “Like having a tiger by the tail”: A qualitative analysis of the provision of online education in higher education. Teachers College Record, 122(2), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146812012200207

- Palm, R. L. (2001). Partnering through outsourcing. New Directions for Student Services, 2001(96), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.27

- Phipps, R., & Merisotis, J. (2005). Is outsourcing part of the solution to the higher education cost dilemma? A preliminary examination. Institute of Higher Education Policy.

- Powers, J. B. (2003). Commercializing academic research: Resource effects on performance of university technology transfer. The Journal of Higher Education, 74(1), 26–50. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2003.0005

- Powers, K. (2019). Examining current institutional outsourcing practices and the IPEDS human resources survey component (pp. 1–31). National Postsecondary Education Cooperative.

- Quigley, B. Z., & Pereira, L. R. (2011). Outsourcing in higher education: A survey of institutions in the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 76(2), 38–46.

- Ramani, S., Bradford, G., Dias, S., & Olfman, L. (2022). Identifying a gap in the project management approach of the online program management and University partnership business model. Online Learning, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v26i1.2584

- Russell, A. (2010). Outsourcing instruction: Issues for public colleges and universities. Policy matters: A higher education policy brief. American Association of State Colleges and Universities.

- Schibik, T. J., & Harrington, C. F. (2004). The outsourcing of classroom instruction in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 26(3), 393–400.

- Springer, S. (2018). One university’s experience partnering with an online program management (OPM) provider: A case study. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 21(1), 1–14. https://ojdla.com/archive/spring211/springer211.pdf

- Sun, J. C., & Turner, H. A. (2022). In-house or outsource? Chief online learning officers’ decision-making factors when considering online program managers. UPCEA.

- Weisman, A. (2023). Requirements and responsibilities for third-party servicers and institutions (GEN 23-03). Department of Education. https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/dear-colleague-letters/2023-02-15/requirements-and-responsibilities-third-party-servicers-and-institutions-updated-feb-28-2023

- Wekullo, C. S. (2017). Outsourcing in higher education: The known and unknown about thepractice. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39(4), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080x.2017.1330805

- Wertz, R. D. (2000). Issues and concerns in the privatization and outsourcing of campus services in higher education. Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ncspe.tc.columbia.edu/working-papers/files/OP10.pdf

- Whalen, B. (2008). The management and funding of US study abroad. International Higher Education, 50, 15–16. https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/ihe/article/download/8005/7156

- Yang, H., & Steensma, H. K. (2014). When do firms rely on their knowledge spillover recipients for guidance in exploring unfamiliar knowledge? Research Policy, 43(9), 1496–1507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.04.016