?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Integrating a therapy dog into physical activity sessions may help children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to increase physical activity and gain-related health benefits. This exploratory intervention assessed the feasibility of integrating a therapy dog into exercise sessions and its efficacy to improve physical activity outcomes in children with ASD. After two familiarization sessions, we randomly assigned 18 children with ASD (mean age = 10.1, SD = 2.5) into two groups (n = 9). We used a crossover design and randomized groups to attend a weekly physical activity session with or without a therapy dog for four weeks. Each group had two sessions with the presence of 1–2 therapy dogs and two sessions without a therapy dog. We assessed feasibility by measuring participant attendance to the crossover sessions and retention in the intervention. We measured efficacy by recording light physical activity, moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), number of bone-impacts, and sedentary time using activity monitors (accelerometers) in each session. We compared physical activity outcomes between the crossover sessions with and without a therapy dog using repeated measures MANOVA. Attendance at the sessions was 92% and the retention rate was 90%. Participants had 13% more minutes of light physical activity (mean difference = 3.5 min; 95% CI: 1.2, 5.8 min) and 22% less sedentary minutes (–2.4; –4.3, –0.1) in the sessions with a therapy dog. MVPA and the number of bone-impacts did not differ between the sessions (p > 0.05). Our results suggest that integrating therapy dogs into physical activity sessions is feasible and it increases light physical activity and decreases sedentary time in children with ASD.

Physical activity (PA) is an essential determinant of health in children, including physical, mental, cognitive, and social health (Janssen & LeBlanc, Citation2010; Poitras et al., Citation2016). Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) spend less time in PA and are less likely to meet PA guidelines when compared with typically developing children (Jones et al., Citation2017; Rostami Haji Abadi, Zheng et al., Citation2021). Inadequate PA may contribute to health concerns reported in children with ASD, such as an elevated rate of obesity and deficits in bone (Matheson & Douglas, Citation2017; Rostami Haji Abadi, Neumeyer et al., Citation2021).

Difficulties in social interactions and adverse social experiences (e.g., exclusion) may contribute to lower PA in children with ASD (Jachyra et al., Citation2021; Memari et al., Citation2017; Pan et al., Citation2011). The theory behind animal-assisted intervention (AAI) to benefit children with ASD comes from human–animal interaction studies; specifically, research has identified that a reciprocal relationship with animals can contribute physical and psychological benefits (O’Haire, Citation2013). AAI offers an attractive option for children with ASD, as the presence of therapy dogs improves their social interactions (Hardy & Weston, Citation2020; Hill et al., Citation2019; O’Haire, Citation2013, Citation2017). Social interaction has been associated with PA intensity in children with ASD (Jozkowski & Cermak, Citation2020; Memari et al., Citation2017; Pan et al., Citation2011). The presence of a therapy dog increases PA in children with obesity (Wohlfarth et al., Citation2013) and adolescents with orthopedic limitations (Vitztum et al., Citation2016). In addition, qualitative studies suggest that children with ASD may benefit from integrating a therapy dog into a PA program (Monika & Maria, Citation2015; Obrusnikova et al., Citation2012). To date, however, no quantitative study has assessed if an AAI with therapy dogs can increase PA in children with ASD.

This exploratory study aimed to assess the feasibility and efficacy of an AAI on PA outcomes during exercise sessions in children with ASD. Based on the existing literature, we hypothesized that the AAI would be feasible, and children with ASD would gain more PA and less sedentary time in AAI sessions compared with sessions without a therapy dog.

Methods

The University of Saskatchewan Biomedical and Animal Research Ethics Boards reviewed and approved this study. The parent or legal guardian of each participating child provided written consent. We asked for assent from the participating children. The therapy dog handlers provided written consent for the animals to participate.

Study Design

The study design was a randomized, crossover AAI, where study participants served as their own controls when comparing PA between sessions with and without a therapy dog. Given the exploratory nature of this study, we chose a crossover design as a comparison within participants helps reduce confounding factors and eliminates between-subject variability in measured outcomes, thus requiring a smaller sample size (Turner, Citation2020). A carryover effect was not expected in this study; therefore, a washout period of one week was considered adequate.

Participants

We recruited children with ASD from the community (via Autism Services of Saskatoon) and the Physical Activity for Active Living (P.A.A.L.) program run through the University of Saskatchewan. The P.A.A.L. is a PA program for children and youth with physical and/or intellectual impairments. The inclusion criteria were 6–14-year-old children with an ASD diagnosis (autism, Asperger syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified) and no allergy to dogs. Twenty children, 17 boys, and 3 girls, met the entry criteria.

Animal-Assisted Intervention

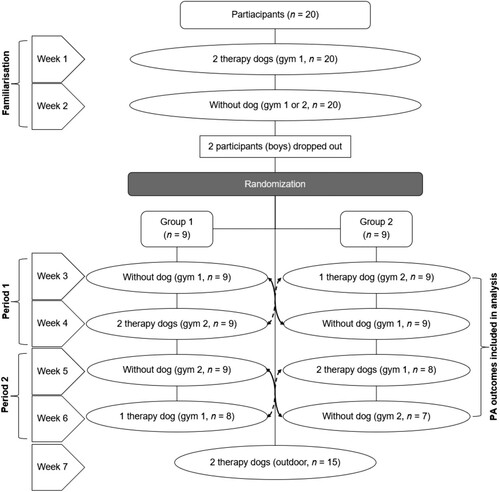

The AAI was a weekly PA session for seven weeks from April to June 2017 at the University of Saskatchewan (). We did not measure PA in the first two sessions to reduce the novelty effect and give participants the opportunity to become familiar with the two participating therapy dogs and their handlers, the volunteers guiding the PA sessions, wearing the accelerometers, and participating in the physical activities (e.g., circuit exercises). For the following four sessions, the participants were randomized into two groups (n = 9), and groups were randomized to sessions with or without a therapy dog and handler presence by one of the investigators (SK) using a computer-generated random sequence (). Participants or their parents/guardians were not informed about the presence or absence of the therapy dog and handler before the PA session. Participants concurrently attended PA sessions in the adjacent gyms, one with and the other without the therapy dog and handler. We held the last session outdoors as requested by the parents/guardians of our participants.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the dog-assisted physical activity intervention in children with autism spectrum disorder.

The PA sessions were approximately 60 min in duration and were led by two instructors experienced with adapted PA programming for children with ASD. Both instructors used the same PA protocol in all sessions ().

Table 1. Exercise session plan.

Each participant was partnered with a student volunteer for the entirety of the PA sessions. All volunteers participated in a mandatory study orientation and most were from the P.A.A.L. program or had previous experience working with children with differing abilities, including children with ASD. The volunteers assisted with the PA activities and encouraged participants to stay on task during the sessions. The therapy dog handlers guided the participants’ interactions with the therapy dogs. This ranged from inviting the participants to walk alongside a dog (while holding its leash) and handler to following a dog through an obstacle course or having the dog follow them in an activity. The therapy dog and handler took part in all the PA session exercises alongside the participants. The participants engaged with the therapy dogs to differing degrees throughout the PA sessions. The handlers were cognizant of “sharing” the therapy dog the best they could between willing participants, and they engaged in physical activities only alongside the therapy dog. We chose to work with two therapy dogs, given the exploratory nature of the study.

Both therapy dogs and two handlers were from St. John Ambulance, an international humanitarian organization. Dogs and handlers participating in the St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Program have passed a national suitability test, including dogs passing behavior and personality testing and humans passing a sector check to work with vulnerable persons. The broad aim of a therapy dog program is to provide comfort and support to the individuals during the dogs’ visit within a variety of settings, from university campuses through to senior living centers and hospital emergency departments (Marcus, Citation2011). Both participating therapy dogs were of the Boxer breed, known to be patient with children (Canadian Kennel Club, Citationn.d.). One of the handlers had professional dog-training experience from Extreme K-9 in the United States and completed an AAI certificate at Harcum College, also in the United States. The other handler was a registered Social Worker. Combined, the handlers had over 3000 practice hours in the therapy dog field with various populations, including children with physical and developmental disabilities.

Measurements

To objectively record minutes of PA and sedentary time, each participant was fitted with an accelerometer (model wGT3X-BT, ActiGraph, Pensacola, Fla., USA) for the entirety of each session. The accelerometer was attached with an adjustable elastic belt and positioned on the participant's right hip (Kehrig et al., Citation2019). We recorded minutes of light, moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), sedentary time, and estimated bone-impacts in all PA sessions using validated protocols we have described in detail previously (Kehrig et al., Citation2019). We defined the bone-impacts based on resultant accelerometer peaks ≥ 3.9 g based on the positive relationships between bone strength and the number of accelerometer impact peaks (counts) reported in children (Kehrig et al., Citation2019). We measured participants’ height and weight using our standard protocols (Duff et al., Citation2017) and asked parents/guardians to complete a questionnaire on their child’s health (e.g., ASD diagnosis and symptoms).

Statistical Analysis

We based our sample size on a previously reported sample (n = 12; effect sizes η2 > 0.8) that used a similar AAI to assess the effect on PA in children with obesity (Wohlfarth et al., Citation2013). We extended our recruitment goal to increase our study’s power and account for possible challenges with the intervention and measurement compliance in our cohort. We randomized participants into two groups to facilitate a group size of approximately 20 participants (including children, volunteers, instructors, therapy dogs, and handlers). We estimated feasibility by assessing attendance at the PA sessions and retention in the 7-week AAI (). We calculated the percentage attendance as the mean of sessions each participant attended over the total sessions after randomization into the crossover PA sessions. We calculated the percentage retention rate as the percentage of participants who completed the 7th week intervention divided by the total number of participants who consented to the study.

Before comparing PA outcomes between sessions with and without a therapy dog, we tested and confirmed that PA outcomes did not differ between the sessions in the adjacent gyms (without a therapy dog) (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.839, F(5, 12) = 0.461, p = 0.798). We also confirmed that the PA outcomes did not differ between the sessions with one or two therapy dogs (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.940, F(5, 10) = 0.127, p = 0.983). We imputed the individual PA outcomes from period 1 to 2 for three participants who missed either session with or without a therapy dog in period 2 ().

We compared PA outcomes (minutes spent in light, MVPA, the number of bone-impacts, and sedentary time) between two sequences (i.e., with or without a therapy dog) of PA sessions over two periods of crossover sessions () using repeated measures MANOVA. With a significant omnibus effect of the sequence (sessions with or without a therapy dog), we performed a pairwise comparison of PA outcomes between the sessions. We used IBM SPSS 25 to perform data analyses and considered p < 0.05 significant.

Results

We describe participants’ background characteristics and the ASD diagnosis/symptoms in . Attendance in the crossover sessions was 92%. The retention rate was 90% over the 7-week AAI. The PA outcomes, including sedentary time, differed between the sessions with and without a therapy dog (Pillai’s Trace = 0.661, F(4, 14) = 6.820, p < 0.003, ηp2 = 0.661). Participants had 13% more minutes of light PA (mean difference = 3.5 min; 95% CI: 1.2, 5.8 min) and 22% less sedentary minutes (–2.4; –4.3, –0.1) in sessions with a therapy dog. MVPA and the number of bone-impacts did not differ between sessions (p > 0.05) ().

Table 2. Characteristics of the participants (n = 18Table Footnotea).

Table 3. Average PA and mean differences , with 95% confidence intervals, between the sessions without or with therapy dog(s).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the feasibility and efficacy of an AAI on PA outcomes and sedentary time in children with ASD. The therapy dog PA intervention was determined to be feasible based on the high attendance and retention rates. It is possible that incorporating an AAI into the PA sessions served as an internal motivator for the participants to adhere to the intervention. Previous research on AAI shows that the presence of a therapy dog in PA sessions creates a sense of joy and attention in children with reduced mobility (Monika & Maria, Citation2015). We also observed that our participants enjoyed interacting with the therapy dog and were interested in engaging in physical activities alongside them. This may be explained by the social interaction the therapy dogs can facilitate both internally and within participants, as well as the positive inclination of children with ASD toward animals (O’Haire, Citation2013, Citation2017). Wohlfarth et al. (Citation2013) suggest that a therapy dog could unconsciously “trigger implicit motives which enhance motivation for activity” in children. An increase in motivation for PA was also reported in an AAI for children with reduced mobility (Monika & Maria, Citation2015). In addition, dogs offer non-judgemental companionship, making social engagement, and interactions more comfortable for children with ASD (O’Haire, Citation2013).

Difficulties in social interactions are a known risk factor for lower PA in children with ASD (Memari et al., Citation2017; Pan et al., Citation2011). The theory behind AAI to benefit children with ASD comes from human–animal interaction studies; specifically, research has identified that a reciprocal relationship with animals can contribute physical and psychological benefits (O’Haire, Citation2013). According to two systematic reviews, the presence of a therapy dog increases social interaction in children with ASD (O’Haire, Citation2013, Citation2017), and social interaction is associated with PA intensity in children with ASD (Jozkowski & Cermak, Citation2020; Memari et al., Citation2017; Pan et al., Citation2011).

The children in our study had 13% more minutes of light PA in the presence of a therapy dog. This may be explained by the children’s eagerness to walk with the therapy dogs. Wohlfarth et al. (Citation2013) reported that children with obesity walked a longer average period of time in the presence of a therapy dog. A similar finding was reported in children and adolescents with orthopedic limitations (Vitztum et al., Citation2016). This is an important finding because increasing light PA may help prevent obesity in children (Kwon et al., Citation2011) and reduce high obesity rates in children with ASD (Healy et al., Citation2019; Kamal Nor et al., Citation2019). Emerging evidence also suggests cardiometabolic health benefits from light PA in children (Carson et al., Citation2013; Cliff et al., Citation2013).

The presence of the therapy dogs in the PA sessions decreased sedentary time (22%) in children with ASD. This finding may have clinical relevance as children with ASD have higher sedentary time when compared with their typically developing peers (Jones et al., Citation2017). Sedentary time generally has been associated with increased physical and psychological health problems in children (Carson et al., Citation2016; Rodriguez-Ayllon et al., Citation2019; Saunders et al., Citation2016; Tremblay et al., Citation2011). The bone deficit in children with ASD might be associated with the reported higher sedentary time (Koedijk et al., Citation2017). In addition, sedentary time has been negatively associated with sleep quality in children with ASD (Wachob & Lorenzi, Citation2015).

It is important to note that the children with ASD accumulated an average 20 min of MVPA and 60 bone-impacts in each PA session, regardless of the presence of a therapy dog. These results were encouraging as we had designed the PA sessions to include running and jumping activities, with a goal to engage children with ASD in both intensive aerobic and impact-type of PA. Engaging in at least 60 min of daily MVPA and activities loading bone (at least 3 days/week) is recommended for all children because of the related health benefits (Kontulainen & Johnston, Citation2021; Poitras et al., Citation2016; Tremblay et al., Citation2016). Children with ASD are less likely to meet the MVPA guidelines; they spend about 30 min less in MVPA per day compared with typically developing children (Rostami Haji Abadi, Zheng et al., Citation2021). Physical activities providing loading stimulus for the skeleton are important because children with ASD have deficits in bone mass and strength (Rostami Haji Abadi, Neumeyer et al., Citation2021). Recorded MVPA and bone-impacts during the PA sessions were promising when compared with the estimations of related benefits in bone strength (Kehrig et al., Citation2019). We estimate that adding 20 min of MVPA or 60 bone-impacts (e.g., jumps) per day could increase tibia bone strength by up to 7% in typically developing children (Kehrig et al., Citation2019). Future randomized control trials are needed to examine the efficacy of similar games and circuit activities to optimize bone strength development in children with ASD.

Our study had key strengths that warrant discussion. The crossover design facilitated PA comparison between sessions with and without a therapy dog within the same group of participants. Comparison within participants can reduce confounding factors, eliminate between-subject variability in measured outcomes, and requires a smaller sample size (Turner, Citation2020). Second, the distribution of sex (15 boys, 3 girls) was a representative sample as boys are four times more likely to be diagnosed with ASD (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Third, we used accelerometers with a validated methodology to objectively quantify PA outcomes and sedentary time (Evenson et al., Citation2008; Trost et al., Citation2011). This is a unique contribution to both the ASD and AAI literature. Fourth, we matched the same volunteers with each participant throughout the PA sessions to keep the level of encouragement and assistance consistent.

There are also some key limitations in our study. The first limitation pertains to a possible selection bias in our sample as we recruited the majority of participants from an adapted PA program. In addition, we are unaware of the reasons for two participants to discontinue the intervention after the introductory sessions. Thus, the study findings may only apply to children with ASD familiar with adapted PA, free of dog allergies, and comfortable with the presence of therapy dogs (e.g., no fear of dogs). Second, we only assessed the AAI's feasibility in the PA sessions by calculating attendance and retention rate; we did not assess other feasibility aspects (e.g., acceptability) (Bowen et al., Citation2009). Third, we did not assess interactions between the participants and therapy dogs or handlers. Since the therapy dog and handler formed a unit, we cannot separate the effect of the therapy dog from the effect of the handler on PA. Future studies may have handlers engaged in all PA sessions and randomize only the therapy dog presence to tease out the role of the therapy dog on children's PA.

The findings of this exploratory study, coupled with its strengths and limitations, can help guide the design of future, more robust AAI-PA interventions for children with ASD (Hardy & Weston, Citation2020; Hill et al., Citation2019; O’Haire, Citation2017). For example, investigators may consider including a broader assessment of activity behaviors, including sleep quality. Future studies could also benefit from systematically monitoring children’s interaction with the therapy dogs in relation to their physical activity measurements.

In summary, the AAI-PA intervention in children with ASD was feasible. Children with ASD had 13% more minutes of light PA and 22% less sedentary minutes in the therapy dog sessions. MVPA and the number of bone-impacts did not differ between sessions with and without a therapy dog.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and their parents/guardians for their altruism in volunteering for this study. We also thank our Dog P.A.A.L. study team, particularly Dr Darlene Charmers, for volunteering as one of the therapy dog handlers, and Jodi Liburdi, Kim Jones, and Michelle Weimer from the College of Kinesiology P.A.A.L. Program and Lynn Latta from the Autism Services of Saskatoon. We also thank graduate students Anthony Kehrig, Kelsey Bjorkman, and Aaron Awdhan for their assistance with the measurements, all undergraduate students for volunteering during the intervention, and St. John Ambulance therapy dogs Kisbey and Subie for their enthusiastic participation.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Bowen, D. J., Kreuter, M., Spring, B., Cofta-Woerpel, L., Linnan, L., Weiner, D., Bakken, S., Kaplan, C. P., Squiers, L., Fabrizio, C., & Fernandez, M. (2009). How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 452–457. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002

- Canadian Kennel Club. (n.d.). Boxer. CKC. Retrieved December 2, 2020, from https://www.ckc.ca/en/Choosing-a-Dog/Choosing-a-Breed/Working-Dogs/Boxer

- Carson, V., Hunter, S., Kuzik, N., Gray, C. E., Poitras, V. J., Chaput, J.-P., Saunders, T. J., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Okely, A. D., Connor Gorber, S., Kho, M. E., Sampson, M., Lee, H., & Tremblay, M. S. (2016). Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: An update. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(6, Suppl. 3), S240–S265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0630

- Carson, V., Ridgers, N. D., Howard, B. J., Winkler, E. A. H., Healy, G. N., Owen, N., Dunstan, D. W., & Salmon, J. (2013). Light-intensity physical activity and cardiometabolic biomarkers in US adolescents. PLoS ONE, 8(8), Article e71417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071417

- Cliff, D. P., Okely, A. D., Burrows, T. L., Jones, R. A., Morgan, P. J., Collins, C. E., & Baur, L. A. (2013). Objectively measured sedentary behavior, physical activity, and plasma lipids in overweight and obese children. Obesity, 21(2), 382–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20005

- Duff, W. R. D., Björkman, K. M., Kawalilak, C. E., Kehrig, A. M., Wiebe, S., & Kontulainen, S. (2017). Precision of pQCT-measured total, trabecular and cortical bone area, content, density and estimated bone strength in children. Journal of Musculoskeletal & Neuronal Interactions, 17(2), 59–68. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28574412

- Evenson, K. R., Catellier, D. J., Gill, K., Ondrak, K. S., & McMurray, R. G. (2008). Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. Journal of Sports Sciences, 26(14), 1557–1565. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410802334196

- Hardy, K. K., & Weston, R. N. (2020). Canine-assisted therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7(2), 197–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00188-5

- Healy, S., Aigner, C. J., & Haegele, J. A. (2019). Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 23(4), 1046–1050. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318791817

- Hill, J., Ziviani, J., Driscoll, C., & Cawdell-Smith, J. (2019). Can canine-assisted interventions affect the social behaviours of children on the autism spectrum? A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 6(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-018-0151-7

- Jachyra, P., Renwick, R., Gladstone, B., Anagnostou, E., & Gibson, B. E. (2021). Physical activity participation among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 25(3), 613–626. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320949344

- Janssen, I., & LeBlanc, A. G. (2010). Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 7(1), Article 40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-7-40

- Jones, R. A., Downing, K., Rinehart, N. J., Barnett, L. M., May, T., McGillivray, J. A., Papadopoulos, N. V., Skouteris, H., Timperio, A., & Hinkley, T. (2017). Physical activity, sedentary behavior and their correlates in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 12(2), Article e0172482. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172482

- Jozkowski, A. C., & Cermak, S. A. (2020). Moderating effect of social interaction on enjoyment and perception of physical activity in young adults with autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 66(3), 222–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2019.1567091

- Kamal Nor, N., Ghozali, A. H., & Ismail, J. (2019). Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and associated risk factors. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00038

- Kehrig, A. M., Björkman, K. M., Muhajarine, N., Johnston, J. D., & Kontulainen, S. A. (2019). Moderate to vigorous physical activity and impact loading independently predict variance in bone strength at the tibia but not at the radius in children. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 44(3), 326–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2018-0406

- Koedijk, J. B., van Rijswijk, J., Oranje, W. A., van den Bergh, J. P., Bours, S. P., Savelberg, H. H., & Schaper, N. C. (2017). Sedentary behaviour and bone health in children, adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Osteoporosis International, 28(9), 2507–2519. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4076-2

- Kontulainen, S. A., & Johnston, J. D. (2021). Physical activity, exercise, and skeletal health. In D. W. Dempster, J. A. Cauley, M. L. Bouxsein, & F. Cosman (Eds.), Marcus and Feldman’s osteoporosis (5th ed., pp. 531–543). Elsevier. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813073-5.00022-8.

- Kwon, S., Janz, K. F., Burns, T. L., & Levy, S. M. (2011). Association between light-intensity physical activity and adiposity in childhood. Pediatric Exercise Science, 23(2), 218–229. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.23.2.218

- Marcus, D. (2011). The power of wagging tails: A doctor’s guide to dog therapy and healing (1st ed.). Demos Medical Publishing.

- Matheson, B. E., & Douglas, J. M. (2017). Overweight and obesity in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A critical review investigating the etiology, development, and maintenance of this relationship. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 4(2), 142–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-017-0103-7

- Memari, A. H., Mirfazeli, F. S., Kordi, R., Shayestehfar, M., Moshayedi, P., & Mansournia, M. A. (2017). Cognitive and social functioning are connected to physical activity behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 33(7), 21–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2016.10.001

- Monika, N., & Maria, M. (2015). Impact of canine assisted therapy on emotions and motivation level in children with reduced mobility in physical activity classes. Pedagogics, Psychology, Medical-Biological Problems of Physical Training and Sports, 19(5), 62–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15561/18189172.2015.0511

- Obrusnikova, I., Bibik, J. M., Cavalier, A. R., & Manley, K. (2012). Integrating therapy dog teams in a physical activity program for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 83(6), 37–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2012.10598794

- O’Haire, M. E. (2013). Animal-assisted intervention for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(7), 1606–1622. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1707-5

- O’Haire, M. E. (2017). Research on animal-assisted intervention and autism spectrum disorder, 2012–2015. Applied Developmental Science, 21(3), 200–216. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2016.1243988

- Pan, C. Y., Tsai, C. L., & Hsieh, K. W. (2011). Physical activity correlates for children with autism spectrum disorders in middle school physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 82(3), 491–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2011.10599782

- Poitras, V. J., Gray, C. E., Borghese, M. M., Carson, V., Chaput, J.-P., Janssen, I., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Pate, R. R., Connor Gorber, S., Kho, M. E., Sampson, M., & Tremblay, M. S. (2016). Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(6, Suppl. 3), S197–S239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0663

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M., Cadenas-Sánchez, C., Estévez-López, F., Muñoz, N. E., Mora-Gonzalez, J., Migueles, J. H., Molina-García, P., Henriksson, H., Mena-Molina, A., Martínez-Vizcaíno, V., Catena, A., Löf, M., Erickson, K. I., Lubans, D. R., Ortega, F. B., & Esteban-Cornejo, I. (2019). Role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in the mental health of preschoolers, children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 49(9), 1383–1410. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01099-5

- Rostami Haji Abadi, M., Neumeyer, A., Misra, M., & Kontulainen, S. (2021). Bone health in children and youth with ASD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporosis International, 32(9), 1679–1691. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-021-05931-5

- Rostami Haji Abadi, M., Zheng, Y., Wharton, T., Dell, C., Vatanparast. H., Johnston, J., Kontulainen, S. (2021). Children with autism spectrum disorder spent 30 min less daily time in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity than typically developing peers: A meta-analysis of cross-sectional data. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00262-x

- Saunders, T. J., Gray, C. E., Poitras, V. J., Chaput, J.-P., Janssen, I., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Olds, T., Connor Gorber, S., Kho, M. E., Sampson, M., Tremblay, M. S., & Carson, V. (2016). Combinations of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep: Relationships with health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(6, Suppl. 3), S283–S293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0626

- Tremblay, M. S., Carson, V., Chaput, J. P., Connor Gorber, S., Dinh, T., Duggan, M., Faulkner, G., Gray, C. E., Grube, R., Janson, K., Janssen, I., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Kho, M. E., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., LeBlanc, C., Okely, A. D., Olds, T., Pate, R. R., Phillips, A., … Zehr, L. (2016). Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: An integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism, 41(6), S311–S327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2016-0151

- Tremblay, M. S., LeBlanc, A. G., Kho, M. E., Saunders, T. J., Larouche, R., Colley, R. C., Goldfield, G., & Gorber, S. (2011). Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 8(1), 98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-98

- Trost, S. G., Loprinzi, P. D., Moore, R., & Pfeiffer, K. A. (2011). Comparison of accelerometer cut points for predicting activity intensity in youth. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 43(7), 1360–1368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318206476e

- Turner, J. R. (2020). Crossover design. In M. D. Gellman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (pp. 576–576). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39903-0_1009.

- Vitztum, C., Kelly, P. J., & Cheng, A.-L. (2016). Hospital-based therapy dog walking for adolescents with orthopedic limitations: A pilot study. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing, 39(4), 256–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/24694193.2016.1196266

- Wachob, D., & Lorenzi, D. G. (2015). Brief report: Influence of physical activity on sleep quality in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2641–2646. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2424-7

- Wohlfarth, R., Mutschler, B., Beetz, A., Kreuser, F., & Korsten-Reck, U. (2013). Dogs motivate obese children for physical activity: Key elements of a motivational theory of animal-assisted interventions. Frontiers in Psychology, 4(October), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00796