ABSTRACT

While pets may be protective for some people at risk of suicide, they may also become a risk factor or even become co-victims when humans end their own lives. It is important to protect against simplistic approaches to human–animal relationships, especially where simplification may endanger human and/or animal lives. Using publicly accessible online media articles between 2010 and 2020, this research sought to progress our understanding of suicidal acts involving pet animals. Sixty-one articles from six countries were identified; a mixed-methods qualitative descriptive (QD) approach to analysis was undertaken composed of descriptive statistical mapping followed by thematic content analysis. Almost 90% of the articles reported the deaths of multiple humans and 23% reported the deaths of multiple animals. A total of 116 animals were identified: mainly dogs, but also 8 cats, 2 rabbits, and 2 non-specified pets. Most animals died, with only nine surviving. Five key categories of scenarios were identified: extended suicides, mercy killings, suicide pacts, family annihilators, and unique. A further level of analysis was undertaken focused on the family annihilator reports (44/61 articles) using a published homicide-suicide typology. Key points to emerge from this analysis include the possibly higher vulnerability of dogs compared with other species. The terms “extended suicide” and “peticide” are discussed with the recommendation that the killing of pet animals be linguistically aligned with that of other killings. A focus on human–animal relationships reveals commonly unexplored intersections across criminology, mental health, and domestic violence and suggests the potential for collaboration across these fields driven by multi-species awareness. This research adds to arguments for data on animal presence in scenarios of human violence to be collected so that responses to protect vulnerable animals, and humans, can be developed.

Suicide is defined as “Death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior” (Crosby et al., Citation2011). It is estimated that more than 700,000 people die by suicide each year (WHO, Citation2019), and for every individual who dies by suicide, an estimated 20 non-fatal suicide attempts occur (Harrison & Henley, Citation2014). Suicide has a ripple effect: for every person who dies by suicide, an estimated 135 people are impacted (Cerel et al., Citation2019). Identifying protective and preventative sources and approaches to this human tragedy are needed, and one emerging aspect in this regard is the close relationships that many humans have with companion animals. Companion animals, hereafter referred to as “pets,” such as dogs, cats, birds, and rabbits, are frequently regarded as “family members” (Arahori et al., Citation2017; Cohen, Citation2002; Howell et al., Citation2015). They are a global phenomenon; in 2018 there were an estimated 470 million pet dogs and 370 million pet cats (Statista, Citation2019).

There is an emerging body of research focusing on the complex intersections between human suicidality and pets. Three recent papers report the role of human–pet relationships in reducing suicidal behavior for some individuals (Hawkins et al., Citation2021; Love, Citation2021; Young et al., Citation2020). However, Love (Citation2021) found that while pets may be protective against suicide at some points, for some people they may also become a risk factor. Indeed, there is a small body of research that explores the topic of pets as co-victims in human suicide (Herzog et al., Citation2021; Oxley et al., Citation2016), including scenarios of suicide involving more than one person. Cooke (Citation2013) refers to the death of animals in tandem with humans as “extended suicide,” while Palazzo et al. (Citation2021) call this phenomenon “peticide.” There is a pressing need to explore both the protective and risk sides of this multi-species intersection as simplistic approaches to human–animal relationships may endanger human and/or animal lives: for example, in clinical health settings, one of the authors has been asked more than once, “should we see if a dog/pet helps?”

Researching suicide and the killing of pets is emotive and complex. Hence, seeking means of extending our understanding in distanced, non-invasive ways are inherent to the aim of not re-traumatizing persons impacted by such deaths. This led to the research described here in which online news media articles reporting the presence (including deaths) of pet animals in incidents of suicide were sourced, collated, and analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively using a qualitative descriptive lens (Kim et al., Citation2017; Sullivan-Bolyai et al., Citation2005) to provide insights into this little-known phenomenon. This approach continues research investigating the inclusion (or not) of pets in Australian coronial investigations of suicide (Mattock et al., Citation2022). The findings of this research were that pets are treated as insignificant and are mostly invisible in these humancentric coronial analyses of suicide. Even when cross-species relationships had been noted as highly significant in deceased persons’ lives, human–animal relationships were not presented as legitimate foci in identifying future preventative approaches.

Three points need to be flagged with readers prior to presenting the data and analysis. First, the data were obtained through publicly reported stories of suicide. There is a generally accepted embargo on reporting of suicides based on concerns of copy-cat actions by vulnerable others (Jordan & McNiel, Citation2021; Niederkrotenthaler et al., Citation2020; Stack, Citation2002). Hence, the media reports we obtained are exceptions to this rule. Second, the reports were written by journalists. Other research exploring news media reporting has demonstrated that the selection of what is newsworthy can be highly biased, with skews to dominant social discourses (Young et al., Citation2017) and the overlooking of true data patterns (Liem & Koenraadt, Citation2007). Third, both these preceding factors may be why most articles described murder-suicides, even though this is a very rare phenomenon (Jordan & McNiel, Citation2021). However, while recognizing that this research is highly selective, the lack of prior research positioned the technique of media surveying as one of the very few sources available for developing understandings of an under-researched and unrecognized human, and animal, tragedy.

Methods

From Google and Yahoo news, between January 2010 and May 2020, online articles were collected using the terms “pets,” “animal,” “dog,” “cat,” and “suicide.” To ensure duplicates were removed, unique identifiers such as date of report and location of incidents and victims’ names were tracked. Three cases were from a previous research report (Cooke, Citation2013).

Initially, articles were collected from the USA, the UK, and Australia (the locations of the authors). However, owing to the low number of articles in the UK and Australia, the search was extended to include other countries. Articles were collected by three individuals and crosschecked for duplicates. While the focus was on suicide, many reports were of murder-suicides. Hence, data on human victims were also collated. For each article, the following information was gathered: number and species of pets (including deaths, survivals, pets noted as being present), the sex and age of the person who died by suicide, number of victims/sex/age (suicides and murders), number of child and adult victims, and cause of death for both humans and animals. The focus of this report is on the pet animals.

A mixed-methods, qualitative descriptive (QD) approach to analysis was undertaken composed of the generation of descriptive statistics followed by a thematic content analysis of the articles. QD is commonly used in exploring health issues as it aims to generate clear descriptive summaries of phenomena to provide practical suggestions to improve care responses (Kim et al., Citation2017; Sullivan-Bolyai et al., Citation2005). The overarching aim was to better understand suicidal acts including pets. Descriptive data were calculated by the second, third, and fourth authors. The thematic process and analyses were undertaken by the first and second authors, with themes and coding being independently identified and then finalized collaboratively. This study did not require ethical approval as the data were available through the public domain.

Results

We located 66 news articles. Five articles were removed owing to them being outside the time frame (pre-2010), not being relevant to pets (e.g., man kills wife and then himself as a result of a prior animal abuse trial), or involving pets but outside the scope of the study (e.g., a dog following his owners who had jumped into a river). This left us with a total of 61 articles for analysis. The majority of these were from the USA (78.7%; 48/61), with the remaining being from the UK (9.8%; 6/61), Australia (4.9%; 3/61), India (3.3%; 2/61), Canada (1.6%; 1/61), and Thailand (1.6%; 1/61).

Animal Victims

Of the 61 reports, the majority (77.0%; 47/61) involved a single animal, with the remaining involving multiple animals (23.0%; 14/61). A total of 116 animals were identified; of these, the majority were dogs (89.7%; 104/116), although cats (6.9%; 8/116), rabbits (1.7%; 2/116), and non-specified “pet(s)” (1.7%; 2/116) were also identified. Of the scenarios involving multiple animals (n = 14), only one did not involve a dog (cat and rabbit). It is important to note that a single scenario involved the death of 31 dogs; however, removing this report from the data still means that dogs were the most common victims (85.9%; 73/85).

A total of 106 animal deaths were reported. In addition, seven dogs survived and two were unharmed (one in a suicide pact and one survived unharmed in a household murder where another dog was killed). Of the surviving dogs, one was suspected to have been attacked incidentally (perhaps seeking to protect their owner who was the target of the attack), while the others seem to have been deliberately targeted and only accidentally survived.

The dominant weapon used was a gun (43 animal deaths; 3 survivals), and this was the weapon most commonly used to take human lives (either victims, their own lives, or both) as well. Gassing via carbon monoxide (usually automobile exhausts) was the second most common form of weapon. It is worth noting that if the one instance where 31 dogs were killed is removed, this makes gassing via carbon monoxide (7 animals) equitable to reports of poisoning (6 animals) and impacts (e.g., jumping from a height) (5 animals). In reports of 11 animal deaths, no means of killing was identified (9 reports in comparison to 3 unknown means reports of humans). summarizes the modes of killing used on animals and those used in the deaths of humans.

Table 1. Animal deaths: method of killing, survivals, and comparison with human death methods.

In 62.3% (38/61) of the articles, the death of a pet was in the title. The names (e.g., Gizmo, Frodo) of 10 pets were reported (9 dogs, 1 cat), the breed of 12 dogs was identified, and 8 articles included a photo of the pet, both with and without their owner. One-third (32.8%; 20/61) of articles used the term “pet” at least once in the text, often combining this with the species (e.g., “pet rabbit”). The term “family dog” or “family pet” was used in nine articles (7 articles referred to the “family dog,” with 4 of these references also being in the articles’ title; and 2 articles referred to the “family pet”). We note that while “companion animal” is preferred in the human–animal studies field, rather than “pet” (Howell et al., Citation2022), none of the news media articles used this term, but one-third (20/61) did include the term “pet” at least once. These articles were from all the countries found except one: Canada, where only one article was sourced anyway. Arguably, “pet” is the everyday term recognized and in use.

Human Victims

The majority of the incidents involved murder-suicides, where one (or more) individual(s) killed others(s) and themselves (82.0%; 50/61). This category includes suspected suicide pacts, where one individual killed the other individual. The remainder of cases were suicides where one or more individuals killed themselves (18.0%; 11/61). In the reports of suicide, 54.5% (6/11) involved an individual female, 18.2% (2/11) involved an individual male, and 27.3% (3/11) involved multiple individuals. The victim survived in two reports.

In the murder-suicides, 88% (44/50) of these involved a single perpetuator and 4% (2/50) involved a pair of perpetuators. In 8% (4/50) of cases, the number of perpetuators was unknown. In 66% (33/50) of these cases, the perpetuator was male, while in 12% (6/50) the perpetuator was female. For 4% (2/50) of cases, a male–female couple was reported to have been responsible for the murder-suicide. In the remainder of the reports, the sex of the perpetuators was unknown. The perpetuator attempted to kill themselves in all these incidents and was reported to have done so in the majority of cases (92%; 46/50).

The number of human victims killed by the perpetuator (not including their suicide) varied, with 56% (28/50) involving single victims and 36% (18/50) involving multiple victims. In 8% (4/50) of reports, the number of victims was unknown. Forty percent (20/50) of victims were individual females, 6% (3/50) were individual males, and 42% (21/50) involved multiple victims. In the remainder of the reports, the number of victims was unknown. Few victims survived these attacks, with only one individual male victim survivor (2%; 1/50) being reported.

As identified in , the most common weapon used in these incidents was a gun. One of the most obvious features of the news reports was that the majority (86.9%; 53/61) identified more than one human being as having died, either through suicides involving multiple individuals (4.9%; 3/61) or via murder-suicide (82.0%; 50/61). Investigating this phenomenon underpins the qualitative thematic process outlined next.

Human and Animal Locations of Deaths

In 58 of the 61 reports (omitting a case where a dog was left at home with the deceased wife and two cases where the location of death was unreported), only 7 human and animal deaths were not in the human and animal's residence. The non-residence-based suicides were usually single-person suicides (6 of 7; 1 suicide pact), where the suicidal human had chosen a death location (cliff, lake, train line, remote location, work – veterinary clinic, hotel room).

Thematic Analysis

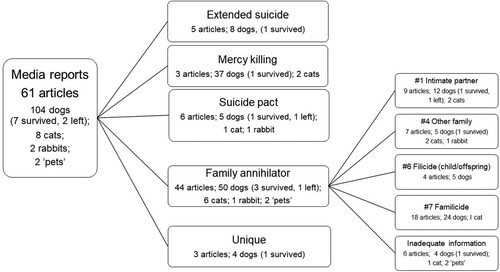

Thematic content analysis was undertaken, driven by our interest in understanding the animal experience within the human violence reported and seeking to “organize” the bulk of reports that involved more than one deceased human. As most articles focused on the human victims, the first round of theming involved grouping the human scenarios. In the second approach, we sought to identify patterns of animal involvement. This included incorporating numerical data on species and survival or fatality of animals within themed human scenarios, especially family annihilation. summarizes these results.

Figure 1. Thematic summary: themes, subthemes, numbers of articles, and animal deaths/survivals by species.

Initial theming identified five core scenarios:

Extended Suicides (n = 5/61): Where there was a general indication that the deceased human had a sense of extended self that had included the pet animal, as per Cooke (Citation2013).

Mercy Killings (n = 3/61): Where there was an overt statement that the deceased had been concerned that their pet(s) would not receive adequate/appropriate care once their human caregiver was gone.

Suicide Pacts (n = 6/61): Where it was reported that there was evidence that a couple (usually), or multiple family members, had agreed to end their lives together.

Family Annihilators (n = 44/61): In a large majority of cases, a single perpetrator had taken the life of at least one human family member and attempted or succeeded in killing a pet(s) and then had ended (or attempted to end) their own life.

Unique (n = 3/61): Three reports stood alone. In the first article, another human and a dog were killed by accident in the process of a person taking their own life. In the second article, a woman tried to help a friend to end her own life along with her two dogs. The dogs died but the friend survived. The third article focused on a dog who was shot in the eye in a domestic murder-suicide; the human victims involved were not identified.

To understand the mass of family annihilator scenarios (72.1%), we used the homicide-suicide typology developed by Jordan and McNiel (Citation2021). Their typology was chosen as it is very recent, builds on previous similar work in this field (McPhedran et al., Citation2018; Wood Harper & Voigt, Citation2007), and has already been cited (Sun et al., Citation2021). In addition, while there are critiques of using generic frameworks to understand homicide-suicide that do not account for regional and cultural contexts (McPhedran et al., Citation2018), given that only four of the articles coded “family annihilator” were not from the USA, it was deemed appropriate to use a USA-based analysis. The proportion of gun deaths in the media articles and the location of many of these in the USA is in keeping with this country's pattern: high gun ownership accompanied by high rates of gun deaths (Eargle & Esmail, Citation2016). Jordan and McNiel’s (Citation2021) typology used machine learning to analyze 2447 deaths across the USA via a national reporting system, so is arguably the most objective approach possible in an emotive field.

The homicide-suicide typology developed by Jordan and McNiel (Citation2021) has eight categories:

Intimate Partner – Relational,

Extrafamilial,

Intimate Partner-Distress,

Other Family,

Intimate Partner – Physical Health,

Filicide (child),

Familicide (multiple victims always including a child), and

Indiscriminate/Rage (multiple victims).

Using this framework to screen the family annihilator scenarios, four of these typologies were seen to be reported (1, 4, 6, 7 – italicized). The theming process was undertaken independently by the first two authors. Only 7 of the 61 articles were not initially independently agreed on. In four of the cases, there was insufficient information in the article. These articles were less than 200 words long. However, owing to the term “homicide-suicide” being used in the article, these four, plus two highly indeterminate scenarios, were categorized as a sub-category of the family annihilator theme.

Given that the first-level theming code identified was “family annihilator,” all second-level scenarios were familial. Hence, typology 2 (Jordan & McNiel, Citation2021) was excluded as only 2 non-familial deaths were reported in the 61 articles. Given the dearth of information, neither typology 3 nor 8 were used. In addition, our first-level theme of “suicide pact” seemed to equate to Jordan and McNiel’s (Citation2021) fifth typology. Once these human categories were used to categorize the articles, a summative analysis on the pets’ death was undertaken (see ).

Our analysis of the family annihilator subthemes did not reveal any exclusionary patterns. However, what this indicates is that pets may be victims of all the forms of murder-suicide identified. No patterns of exception that could have indicated that animals may be less vulnerable in some forms of murder-suicide emerged. The human focus of homicidal intent (e.g., partner, child, both) does not exclude animals as potential victims. Within this, the dominance of dogs as victims continued to stand out, although no clear patterns regarding other species emerged. However, as noted, only just over 10% (12/116) of reports involved non-canine species.

Discussion

This study aimed to better understand suicidal acts including pets. The majority of the incidents reported involved homicide-suicides, with the remainder being suicides. Most animals died in these incidents, with only nine surviving. The majority of pets that were killed were dogs, though the deaths of cats and rabbits were also reported. A gun was the weapon predominantly used in these incidents. Five core scenarios for human suicides including animals were identified: extended suicides, mercy killings, suicide pacts, family annihilators, and unique. Further analysis of the family annihilator reports highlighted the higher vulnerability of dogs compared with other pets. Given the lack of previously published research on this topic (pets and suicide) and the even more limited number of articles focusing on human suicides that include animal deaths, these stories establish that animal deaths in scenarios of human suicide do occur and, as indicated by the emotive responses to animal deaths and injuries in some of the articles, can have traumatic impacts by themselves.

This discussion will focus on the species identified in the reports, suggestions as to the motives of human caregivers for taking animal lives when suicidal, terminology, and the societal animal turn. Over all of this discussion sit questions regarding notions of pets as family: specifically, are these killings of animals grim, dark manifestations of the identification of pets as family members?

Species

This collation of articles points to the huge vulnerability of the animals enmeshed in everyday human lives that we call pets and increasingly identify as family (Arahori et al., Citation2017; Dotson & Hyatt, Citation2008). Even noting the inherent skewing of scenarios owing to this being an analysis of news media reporting, dogs present as dramatically at risk in cases of human violence. Yet, as shown by the small number of cat deaths and (perhaps surprisingly) rabbits as well, no species of pet is necessarily exempt from the risks humans pose to their lives. A second factor that stands out starkly is the deliberateness in many of the animal killings. This is stark: the forms of killing used seem deliberately chosen to be lethal to the animals in question, with pets commonly shot or gassed. Where any details are provided, animals seem to have been killed either prior to the (final) suicide of the human (in the cases of homicide-suicide) or with the human(s) (e.g., gassings). Only two articles indicate that the animal death was not deliberate, and two may have been unintentional.

One of the questions considered at length by the authors was “Why so few cats?” Globally, it is estimated there are 370 million cats kept as pets, a not distant comparison to the 470 million pet dogs that are kept (Statista, Citation2019). It may simply be that cats are less likely to be reported as killed (which raises the question of why their deaths would be overlooked compared with dogs). However, it may be a reality that reflects species capabilities. Cats are perhaps far better at escaping and hiding. Compared with dogs, cats can climb up high, they are less likely to make a noise once hidden, and they may be able to escape the site of violence more readily, perhaps through a window or cat-flap. It is also possible that they are less incorporated into killers’ “family” conceptions and may not be considered as family members in the same way that dogs are.

The two rabbit killings raise similar queries regarding species death reporting and inclusion in concepts of family. There is some evidence that rabbits are an increasingly popular pet species (DeMello, Citation2016), and a survey by Howell et al. (Citation2015) found that 76% of rabbit owners thought of their rabbits as family. However, a unique dynamic is that rabbits are commonly housed both indoors and outdoors (Rooney et al., Citation2014), which may be a factor in their lack of inclusion in such incidents. The reporting of these rabbit deaths may indicate a general increase in awareness of them as sentient others more in line with dogs and cats, moving into the limelight as also being “family.” Paradoxically, this inclusion may also increase their likelihood of becoming victims in human suicides and homicides.

One (of the many) question to emerge from this research is why animals may be treated differently? While the species differences were noted earlier, at times even the treatment of dogs in the same home differed. For example, in one case of familicide, one dog was killed in the house along with the human family members, but another dog was found “in the garage.” Why the different treatment? Was the dog someone else's? Was it not deemed a family member by the perpetrator? Was it just that this dog was “overlooked”? Or, was there an element of “mercy” involved in the thinking of the perpetrator?

Animal Deaths as “Mercy Killing”

“Mercy killing” is the only theme able to directly address the position of the pet animal in the family. This theme picked up on evidence that someone had taken a pet's life as part of their suicide because of concern for the animal's wellbeing once they were gone. It is possible that other scenarios included this concern as a driver for animal death(s), but this was not noted in the article or was not known or perhaps was not revealed by police at the time of reporting.

A recent study of coroners’ reports of suicides in Australia (Mattock et al., Citation2022) found several cases where the person who had died had been very concerned about ensuring that their pet(s) were cared for after their death. This included asking people to care for their pets. Similarities can also be drawn to older people who have attempted to kill their pet before themselves because they were concerned there would be no one to take care of it after their death (Lynch et al., Citation2010). These stories stand in contrast to the research undertaken by Love (Citation2021) and Young et al. (Citation2020), both of whom identified that care for an animal's wellbeing after an owner's demise could be protective against suicide. What this seemingly contradictory information indicates is that the human–animal connection regarding human suicide is extremely complex, requiring far more investigation and data collection to understand and develop a web of informed, and coherent, protective responses for humans and animals.

This research has focused on suicide involving domestic pets. However, there are examples of suicide that involve other animals, such as livestock. Akcan et al. (Citation2011) describe a case in which a child seemingly died by suicide because of the death of a chicken. Joiner (Citation2014, p. 138) highlights a case of a 59-year-old male farmer killing 51 dairy cows out of the 100 cows he owned and then shooting himself. However, he only killed the cows that required multiple milkings per day. This story indicates that concerns for animal welfare after an owner's suicide are not unique to pet animals. Joiner (Citation2014) also coined the term “mercy killing” for this human–animal phenomenon, one that he applies, perhaps even more controversially, to examples of filicide (parents killing a child).

Our research indicates that sometimes the motivations to kill animals within the context of suicidality may have “caring” roots: roots that can be both protective, and deadly, for both humans and animals. Again, this is a complexity that needs to be explored far more in the interests of all the species involved.

Terminology – Extended Suicide: Peticide

Two terms have been used to distinguish the killing of pet animals within the context of human suicide. Cooke (Citation2013) uses the term “extended suicide with pets” and Palazzo et al. (Citation2021) uses “peticide.”

Both Cooke (Citation2013) and Oxley et al. (Citation2016) have used and discussed the usage of the term “extended suicide” as being suicide where human ego/identity is extended to a pet animal. Along with Oxley et al. (Citation2016), this current research challenges the use of this term and the notion of extension of self as applying to all suicides that include pets. Extending the term “suicide” to encompass the animals who have died is inaccurate as their deaths have been without their (the animal's) choice. There is no concrete evidence to date that animals purposely suicide, although this is a concept which continues to be debated (Peña-Guzmán, Citation2017; Preti, Citation2007). While numerous news articles have reported “animal suicides,” generally such cases are explained by other information: for example, multiple dogs (scent hounds) jumping from a bridge was explained by the presence of a mink nest underneath the bridge (Bering, Citation2018, p. 42). While there is evidence of nonhuman “martyrdom,” such as termites who will fight to the death to protect the mound within which the colony queen exists (Joiner et al., Citation2016), evidence that animals choose to end their lives in the way that humans are demonstrably able to do is lacking. Hence, we suggest that usage of the term “extended suicide” is erroneous.

Peticide is the other term that has been used (Palazzo et al., Citation2021). While “extended suicide” misrepresents the deliberateness of taking another being's life, “peticide” linguistically positions the deliberate killing of an animal alongside all the other forms of killing identified in this research: su-icide (self), hom-icide (other), famil-icide (partner and child), fil-icide (child), pet-icide (animal). Hence, the terminology of including a pet in suicide, as explored here, would become suicide-peticide, which more clearly delineates the perpetration of the deaths.

Currently, documentation and definitions focus on human perpetrators and victims (Mattock et al., Citation2022), with the killing of animals by humans not being seen as in any way equitable to the killing of humans by humans. It is worth noting that similar omissions of animals as victims occur in other human mental health conditions such as Munchausen by Proxy (Oxley & Feldman, Citation2016), although in recent times animal hoarding has been included in the DSM-5 as a subtype of hoarding (Ferreira et al., Citation2017). However, even within this, the focus is on the human involved – with no descriptive term used to describe the specific victimhood of the animals hoarded.

The use of the term peticide aligns the deliberate killing of the nonhuman family member with the deliberate killing of humans. To illustrate the current overlooking of this issue, one article used the phrase “quadruple murder-suicide” to refer to the murder of three children and their mother and the suicide of the father. But this phrase did not encompass the deliberate killing of their pet dog alongside the human family members. Including the use of the term peticide would give language that recognizes the presence of this other species family member, enabling the phrase “murder-suicide-peticide” to describe the scenario more fully.

An equitable term for animal deaths also provides a linguistic link to the increasing conception of pets as family members (Arahori et al., Citation2017; Cohen, Citation2002) (and presumably seen as family members by family annihilators – otherwise, why include them in the killing?). A number of the articles used the term “family dog” or “family pet” to refer to the deceased animals, and at times the shared vulnerability of the animal victims, alongside that of others such as children, was noted. For example, in reporting a filicide where a man gassed himself, his daughter, and their dog outside his ex-partner's apartment, an informant is noted as aligning both victims saying: “If that was what he wanted to do then he should’ve done it, but the little girl and the dog didn't need to go with him” (italics added).

The term “Peticide” enables the killing of an animal family member to be readily incorporated into the concept of human killings. Yet it recognizes the dependent, highly vulnerable position of these other species who live with humans in their domestic family lives. This is a terminological approach that links to the work of political scientists and critical animal theorists Donaldson and Kymlicka (Citation2011). They argue for pets to have a form of citizenship that recognizes their vulnerability and lack of choice in co-existing within human societies, gives them rights akin to those given to vulnerable human beings, and includes them in the political landscape as rightful co-citizens.

Crossing Disciplinary Boundaries

This research highlights how complex human–animal relations and lives challenge academic and practice siloes. The preponderance of homicide-suicide stories found while using an animal-aware lens immediately implicates three areas of relatively separate academic inquiry. Homicide is generally explored by criminologists and those in the justice and policing fields, while suicide tends to be considered a mental health focus (McPhedran et al., Citation2018). A third, often quite independent, field of inquiry that our research is linked to is that of domestic and intimate relationship violence. Auchter (Citation2010) identifies familial murder-suicide as an extreme form of interpersonal domestic violence. Bridging to the human–animal studies arena in recent times has also seen mounting evidence of the role of pets in the domestic violence field (Taylor et al., Citation2019; Taylor & Fraser, Citation2019), including recognition that animal abuse routinely indicates human abuse, and caring for loved animals is vital in rescuing and protecting victims of intimate violence.

There are links across the human-focused fields identified here. Our research shows not only the connections across human foci but also the intersections with fields that have a focus on animals. Those with a concern for animal protection have an interest in the fields of suicide, homicide-suicide, and domestic violence regarding their concerns for the care for animals. Concerns for animals enmeshed in human violence by police and the public were discernible. News reports that focused on animal victims of human violence commonly reported large amounts of funds being raised very quickly to support the care needs of rescued animals. For example, police officers rescued Sophie, a dog who had survived a gunshot, and took her to an animal rescue service. All are indicators of the way that human resources can readily be mobilized by stories of pet animals in need. This aligns with the work of Montrose et al. (Citation2020) on dog bites, who identified that large amounts of money were raised (e.g., via crowdfunding) along with provision and offers of in-kind support (e.g., free veterinary services) for dogs who were bitten by other dogs and required veterinary treatment. While some humans may seek to take the lives of pets, many others are mobilized personally and financially when they hear of animals impacted by human violence. This is an intersection that bears exploration by both human- and animal-focused fields to see how this concern and interest can be better mobilized and engaged with in the interests of animals, with ways that have implications for human survival and flourishing as well.

Limitations

It is important to highlight that this research is based on new reports written by journalists who are more likely to be experts in what is newsworthy, rather than being suicide or homicide experts. News reports of suicide and homicide-suicide were frequently quite superficial and rarely gave much insight into why the individuals killed themselves, their family, or their pets. Their information (as noted in the articles) was generally from initial police reports, although several reports were of coroners’ investigations. This, combined with the general journalistic embargo on suicide reporting (Jordan & McNiel, Citation2021; Niederkrotenthaler et al., Citation2020; Stack, Citation2002), indicates that the reports present a highly select collection of scenarios, where the presence of multiple human deaths and/or multiple animal deaths seem to over-ride this embargo. However, while they may predominately focus on some of the grimmest, but relatively uncommon, stories of human suicide with animals, they can offer insights of relevance to more common scenarios.

Future Directions

Several key future directions emerge from this research. First, we recommend that the term “peticide” be used to distinguish the deliberate killing of a pet animal. Second, cross-communication between researchers across fields who are interested in homicide, suicide, domestic violence, and human–animal relations offers the potential for new insights, innovative new practices, and findings of benefit to humans and animals. Third, there need to be processes of routinely collecting data as to species and numbers of pet animals involved in cases of human violence. While there are robust sources of data regarding homicide and suicide, there is no consistent collection of data regarding animals in these.

It is not possible to know if the reports found for this research are exceptions or the tip of a hidden iceberg of scenarios. Evidence from the field of domestic violence indicates they are not merely the tip and that actively recognizing and responding to human–animal relationships are life-saving for many humans and animals (Taylor et al., Citation2019; Taylor & Fraser, Citation2019). There is potential to interrogate some of the data collected on human violence more deeply for animal connections; this needs to be explored, although without routine collection of this information at the point of initial investigation by police, this is challenging as there are no data to investigate. But the noted care and concern for animals shown by police in several of the articles indicate that it may not be such a hard task to convince some, perhaps many, officers to do this.

Conclusion

Joiner (Citation2014) notes that “any powerful framework for the understanding of a given phenomenon should ideally not only illuminate that core phenomenon (i.e., murder-suicide per se) but should burn brightly enough that it also sheds light on neighboring phenomena (e.g., incidents involving killing animals and then death by suicide)” (p. 170). The study of pet animals in scenarios of human suicide (and murder-suicide) has the potential to throw light onto not only our understandings of animals but also of the humans involved. These understandings, while at this time more speculative than concrete, are essential given the increasing discussion about and perception of pets as being part of the family.

Acknowledgements

We thank our anonymous reviewers, whose feedback, suggestions, and input have strengthened this paper immeasurably.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Akcan, R., Arslan, M. M., Çekin, N., & Karanfil, R. (2011). Unexpected suicide and irrational thinking in adolescence: A case report. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 18(6), 288–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2011.05.002

- Arahori, M., Kuroshima, H., Hori, Y., Takagi, S., Chijiiwa, H., & Fujita, K. (2017). Owners’ view of their pets’ emotions, intellect, and mutual relationship: Cats and dogs compared. Behavioural Processes, 141(3), 316–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2017.02.007

- Auchter, B. (2010). Men who murder their families: What the research tells us. NIJ Journal, 266(June), 10–12. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/230412.pdf

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW): Harrison, J. E., & Henley, G. (2014). Suicide and hospitalised self-harm in Australia: Trends and analysis. Injury Research and Statistics Series No. 93. Cat. No. INJCAT 169. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. https://apo.org.au/node/42549

- Bering, J. (2018). Suicidal: Why we kill ourselves. University of Chicago Press.

- Cerel, J., Brown, M. M., Maple, M., Singleton, M., Van de Venne, J., Moore, M., & Flaherty, C. (2019). How many people are exposed to suicide? Not six. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(2), 529–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12450

- Cohen, S. P. (2002). Can pets function as family members? Western Journal of Nursing Research, 24(6), 621–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/019394502320555386

- Cooke, B. K. (2013). Extended suicide with a pet. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 41(3), 437–443. http://jaapl.org/content/41/3/437.long

- Crosby, A. E., Ortega, L., & Melanson, C. (2011). Self-directed violence surveillance; Uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Version 1.0. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11997

- DeMello, M. (2016). Rabbits multiplying like rabbits: The rise in the worldwide popularity of rabbits as pets. In M. Pręgowski (Ed.), Companion animals in everyday life (pp. 91–107). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Donaldson, S., & Kymlicka, W. (2011). Zoopolis: A political theory of animal rights. Oxford University Press.

- Dotson, M. J., & Hyatt, E. M. (2008). Understanding dog–human companionship. Journal of Business Research, 61(5), 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.07.019

- Eargle, L. A., & Esmail, A. (2016). Gun violence in American society: Crime, justice and public policy. University Press of America.

- Ferreira, E. A., Paloski, L. H., Costa, D. B., Fiametti, V. S., De Oliveira, C. R., de Lima Argimon, I. I., Gonzatti, V., & Irigaray, T. Q. (2017). Animal hoarding disorder: A new psychopathology? Psychiatry Research, 258, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.030

- Hawkins, R. D., Hawkins, E. L., & Tip, L. (2021). “I can’t give up when I have them to care for”: People’s experiences of pets and their mental health. Anthrozoös, 34(4), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2021.1914434

- Herzog, H., Montrose, V. T., Young, J., & Oxley, J. A. (2021, June 22–24). Extended suicide involving pets: An analysis of news reports [Paper presentation]. International Society for Anthrozoology virtual conference.

- Howell, T. J., Mornement, K., & Bennett, P. C. (2015). Companion rabbit and companion bird management practices among a representative sample of guardians in Victoria, Australia. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 18(3), 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2015.1017095

- Howell, T. J., Nieforth L., Thomas-Pino C., Samet L., Agbonika S., Cuevas-Pavincich F., Fry N. E., Hill K., Jegatheesan, B., Kakinuma, M., MacNamara, M., Mattila-Rautiainen, S., Perry, A., Tardif-Williams, C. Y., Walsh, E. A., Winkle, M., Yamamoto, M., Yerbury, R., Rawat, V., … Bennett, P. (2022). Defining terms used for animals working in support roles for vulnerable people. Animals, 12(15), 1975. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12151975

- Joiner, T. E. (2014). The perversion of virtue: Understanding murder-suicide. Oxford University Press.

- Joiner, T. E., Hom, M. A., Hagan, C. R., & Silva, C. (2016). Suicide as a derangement of the self-sacrificial aspect of eusociality. Psychological Review, 123(3), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000020

- Jordan J. T., & McNiel D. E. (2021). Homicide-suicide in the United States: Moving toward an empirically derived typology. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 82(2), 20m13528. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.20m13528

- Kim, H., Sefcik, J. S., & Bradway, C. (2017). Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Research in Nursing & Health, 40(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21768

- Liem, M. C. A., & Koenraadt, F. (2007). Homicide-suicide in the Netherlands: A study of newspaper reports, 1992–2005. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 18(4), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940701491370

- Love, H. A. (2021). Best friends come in all breeds: The role of pets in suicidality. Anthrozoös, 34(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2021.1885144

- Lynch, C. A., Loane, R., Hally, O., & Wrigley, M. (2010). Older people and their pets: A final farewell. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(10), 1087–1088. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2469

- Mattock, K., Young, J., & Bould, E. (2022). Discourses and silences: Pets in publicly accessible coroners’ reports of Australian suicides. Anthrozoös. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2022.2042084

- McPhedran, S., Eriksson, L., Mazerolle, P., De Leo, D., Johnson, H., & Wortley, R. (2018). Characteristics of homicide-suicide in Australia: A comparison with homicide-only and suicide-only cases. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(11), 1805–1829. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515619172

- Montrose, V. T., Squibb, K., Hazel, S., Kogan, L. R., & Oxley, J. A. (2020). Dog bites dog: The use of news media articles to investigate dog-on-dog aggression. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 40, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2020.08.002

- Niederkrotenthaler, T., Braun, M., Pirkis, J., Till, B., Stack, S., Sinyor, M., Tran, U. S., Voracek, M., Cheng, Q., Arendt, F., Scherr, S., Yip, P. S. F., & Spittal, M. J. (2020). Association between suicide reporting in the media and suicide: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 368, m575. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m575

- Oxley, J. A., & Feldman, M. D. (2016). Complexities of maltreatment: Munchausen by proxy and animals. Companion Animal, 21(10), 586–589. https://doi.org/10.12968/coan.2016.21.10.586

- Oxley, J. A., Montrose, V. T., & Feldman, M. (2016). Pets and human suicide. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 249(7), 740–741. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.249.7.740

- Palazzo, C., Pascali, J. P., Pelletti, G., Mazzotti, M. C., Fersini, F., Pelotti, S., & Fais, P. (2021). Integrated multidisciplinary approach in a case of occupation related planned complex suicide-peticide. Legal Medicine, 48, 101791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2020.101791

- Peña-Guzmán, D. M. (2017). Can nonhuman animals commit suicide? Animal Sentience, 2(20), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.51291/2377-7478.1201

- Preti, A. (2007). Suicide among animals: A review of evidence. Psychological Reports, 101(3), 831–848. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.101.3.831-848

- Rooney, N. J., Blackwell, E. J., Mullan, S. M., Saunders, R., Baker, P. E., Hill, J. M., Sealey, C. E., Turner, M. J., & Held, S. D. (2014). The current state of welfare, housing and husbandry of the English pet rabbit population. BMC Research Notes, 7(1), 942. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-942

- Stack, S. (2002). Media coverage as a risk factor in suicide. Injury Prevention, 8(90004), iv30–iv32. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.8.suppl_4.iv30

- Statista. (2019). Number of dogs and cats kept as pets worldwide in 2018. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1044386/dog-and-cat-pet-population-worldwide/

- Sullivan-Bolyai, S., Bova, C., & Harper, D. (2005). Developing and refining interventions in persons with health disparities: The use of qualitative description. Nursing Outlook, 53(3), 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.005

- Sun, Q., Zhou, J., Guo, H., Gou, N., Lin, R., Huang, Y., Guo, W., & Wang, X. (2021). Incomplete homicide-suicide in Hunan China from 2010 to 2019: Characteristics of surviving perpetrators. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 577. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03574-8

- Taylor, N., & Fraser, H. (2019). Companion animals and domestic violence: Rescuing me, rescuing you. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Taylor, N., Riggs, D. W., Donovan, C., Signal, T., & Fraser, H. (2019). People of diverse genders and/or sexualities caring for and protecting animal companions in the context of domestic violence. Violence Against Women, 25(9), 1096–1115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218809942

- WHO (World Health Organization). (2019). Suicide prevention. https://www.who.int/health-topics/suicide#tab=tab_1

- Wood Harper, D., & Voigt, L. (2007). Homicide followed by suicide: An integrated theoretical perspective. Homicide Studies, 11(4), 295–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767907306993

- Young, J., Bowen-Salter, H., O’Dwyer, L., Stevens, K., Nottle, C., & Baker, A. (2020). A qualitative analysis of pets as suicide protection for older people. Anthrozoös, 33(2), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2020.1719759

- Young, R., Subramanian, R., Miles, S., Hinnant, A., & Andsager, J. L. (2017). Social representation of cyberbullying and adolescent suicide: A mixed-method analysis of news stories. Health Communication, 32(9), 1082–1092. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1214214