ABSTRACT

Canine obesity is one of the top welfare problems of pet dogs. Owners are often unable to successfully recognize and manage their dog’s condition, even with assistance from veterinarians. The aim of this exploratory study was to appraise people’s perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors relating to canine obesity and weight management by analyzing comments made in online public fora and about online video clips. Data comprised 450 posts on 15 threads related to canine obesity from online discussion fora (www.petforums.co.uk, www.reddit.com, and www.mumsnet.com) and 637 comments posted about five videos published online (www.youtube.com). These fora sites either had a dedicated topic area or were entirely for discussions regarding pets. Threads and videos chosen represented a diversity of obesity-related topics, dog breeds, and a range of overweight severities. Data were anonymized and analyzed using thematic analysis. Four key themes emerged: (1) Balancing conflicting responsibilities – Individuals appeared to balance their responsibility in providing their dog with happiness, health, and love, and differences in emphasis placed on these impacted feeding habits and weight management; (2) Need vs. greed – Individuals felt compelled to alleviate perceived hunger in their dog, which made sticking to reduced food diets difficult for some; (3) Minimizing – Individuals varied in the extent to which they perceived excess body fat to be problematic, and language used to describe their dog’s body changed when excess body fat was seen as an issue; (4) Control – Individuals’ perceived control over their dog’s body condition and food intake varied hugely, with some owners believing they had little-to-no control. Whilst such publicly available data need to be interpreted with caution, due to self-selection bias, this study provides valuable insight into factors that impact feeding practices and could impact compliance with weight-reduction programs. These findings can be incorporated into future research and behavior-change initiatives to increase engagement and compliance.

It is estimated that over half of the UK’s pet dogs are overweight or have obesity (German et al., Citation2018), and a similar prevalence is also reported in studies from Europe, Australia, USA, Brazil, and China (Mao et al., Citation2013; Muñoz-Prieto et al., Citation2018; Association for Pet Obesity Prevention, Citation2019; Porsani et al., Citation2020; Rohlf et al., Citation2010). Not only does the prevalence of obesity appear to be increasing (Banfield., Citation2019; German et al., Citation2018), but more cases are developing severe obesity, whereby they exceed the maximum score on the widely used 9-point Body Condition Scoring system, which equates to ∼40% above ideal weight (German et al., Citation2021; Laflamme, Citation1997). Canine obesity is associated with a range of comorbidities, including: diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, hypertension, cardiac disease, respiratory diseases, neoplasia, osteoarthritis, and cruciate ligament disease (German, Citation2006). Canine obesity is also associated with decreased life expectancy (Salt et al., Citation2019) and quality of life (German et al., Citation2012). Successful weight loss is associated with improved quality of life (German et al., Citation2012), mobility (Marshall et al., Citation2009), and insulin sensitivity (German et al., Citation2009). Despite weight reduction having numerous benefits, amongst those that start a weight-loss program, almost half do not reach the target weight and, of those that do, many will relapse (Carciofi et al., Citation2005; German et al., Citation2007; German et al., Citation2012). Owners often underestimate the size of their own pet, even when shown how to use a Body Condition Scoring chart (Eastland-Jones et al., Citation2014). Despite the high prevalence of obesity, a report by the Pet Food Manufacturers Association found that only 8% of owners believed their pet needed to lose weight (Pet Food Manufacturers Association, Citation2019). This may contribute to the finding that when owners have been advised by a veterinarian that their dog is overweight, 50% disagree and maintain that their dog is the ideal weight (White et al., Citation2011).

Owners may find it hard to acknowledge obesity in their own pets owing to the portrayal of canine obesity in both veterinary articles and main-stream media which focusses on individual-level solutions, putting the onus on owners and suggesting that their dog’s obesity is their own personal failing rather than a systematic issue (Degeling et al., Citation2011; Degeling & Rock, Citation2012). One study found veterinarians rated owner responsibility as the largest contributing factor to canine obesity and they felt the owners were to blame (Pearl et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, it has been found that despite veterinarians being the primary sources of health advice for dog owners (Kuhl et al., Citation2021), they rarely discuss weight management with owners (German & Morgan, Citation2008; Rolph et al., Citation2014), a common concern being offending owners (Aldewereld et al., Citation2021; Cairns-Haylor & Fordyce, Citation2017). When veterinarians discuss weight with owners, they vary in the depth of nutritional history taken and the detail provided about prevention and treatment (Phillips et al., Citation2017).

From the existing quantitative research, risk factors for canine obesity include dog-specific factors such as increased age, being neutered, being female, and being from certain breeds (e.g., Labrador retriever, Pug, and Beagle) (Courcier et al., Citation2010; Edney & Smith, Citation1986; Pegram et al., Citation2021). Owner factors are also associated with canine obesity, including increased age, lower socio-economic status, greater BMI, and permissive ownership styles, where owners are highly responsive to their dog’s needs and expect relatively little from them (Courcier et al., Citation2010; Edney & Smith, Citation1986; Herwijnen et al., Citation2020). As valuable as these quantitative research insights are, they do not explain why obesity management and prevention is so challenging for owners and what the solutions might be.

Qualitative research methods are designed to explore the intricacies of everyday behavior and the reasons why people act in the way they do (Fitzpatrick & Boulton, Citation1996). These methods can be useful for understanding social phenomena in natural settings; notably, how people interpret health messages in relation to their own lives (Pope & Mays, Citation1995). Insights from qualitative forum and focus-group analysis include that parents understand the importance of prevention and interventions on childhood obesity but find it difficult to implement these messages in everyday life (Watkins & Jones, Citation2015). Such research has highlighted the importance of health professionals focusing on providing innovative, tailored support to parents to help them implement prevention and intervention strategies, rather than repeating messaging about the concerns of obesity (Appleton et al., Citation2017; Watkins & Jones, Citation2015). There have been limited qualitative studies investigating canine obesity and weight management. Studies have been limited to surveys (Cairns-Haylor & Fordyce, Citation2017; Wainwright et al., Citation2022; White et al., Citation2011) and focus groups (Downes et al., Citation2017) or have focused on veterinarians’ experiences of diagnosing obesity (Aldewereld et al., Citation2021) or advising owners to increase dog walking (Burns et al., Citation2018).

In previous qualitative research studies, investigators successfully analyzed publicly available online data about various health topics, including fertility (Hanna & Gough, Citation2016), strokes (Jamison et al., Citation2018), and obesity in humans (Willmer & Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2018). These studies have led to an increased understanding of individual attitudes toward and perceptions of diagnosis and treatment options, highlighting areas where more information or support is needed from stakeholders. A recent exploration of equine obesity recognition and management used various qualitative methods, including analyzing discussion fora, in-depth-interviews, and focus groups, providing insights into why owners struggled to recognize their horse’s excess weight and found it difficult to implement changes to manage their horses’ weight (Furtado et al., Citation2021). Such insights, which are only possible by using qualitative methods, led to the development of a decision-making guide to empower owners in creating tailored weight-management strategies. In another study, that analyzed data relating to obesity from various online platforms (including Twitter, Facebook, and fora), personal opinions were more commonly expressed in fora, as struggled with weight reduction and seeking direct advice from others (Chou et al., Citation2014). Comments posted in response to videos published online (www.youtube.com) also provided an opportunity to analyze the attitudes and perceptions of individuals regarding dog bites and attribution of blame (Owczarczak-Garstecka et al., Citation2018). Therefore, the aim of the current exploratory study was to explore perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors regarding canine obesity and weight management using comments on online fora and about videos of dogs posted online.

Methods

Discussion threads were collected from three online discussion fora websites, each with at least 200,000 registered users and millions of non-registered visitors each year (www.petforums.co.uk, www.reddit.com, and www.mumsnet.com). These fora sites were either entirely dedicated to discussions regarding pets or had a specific topic area dedicated to pets and were frequently used by pet-dog owners, typically with several new posts per day related to pet dogs. Fora were found by searching “dog discussion forum” using an internet search engine. Criteria for their use were that they must be searchable and open access. Relevant discussion threads within these fora and videos published online (www.youtube.com) were identified using the following search terms: “Dog overweight,” “Dog obese,” “Dog weight,” “Dog fat,” “Dog chubby,” “Dog diet,” “Dog hungry,” and “Dog begging,” There were 127 fora threads that matched these searches and 131 videos. Fifteen discussion threads and comments on five videos were purposively selected for analysis. As qualitative research focuses on understanding individuals lived experiences, the sampling design is not random, but seeks to include the most appropriate data sources for answering the research question (Etikan et al., Citation2016; Johnson et al., Citation2020). A best practice sampling method for qualitative research is purposive sampling; this involves researchers selecting information-rich cases for analysis to make efficient use of resources (Etikan et al., Citation2016; Johnson et al., Citation2020). In the current study, purposive sampling was used to select forum threads and videos that reflected a diversity of topics including dog breeds, overweight severities, and rescued or owned dogs. Other criteria for their selection were that the posts must be from within the previous 6 years (2015–2020) and the discussion must be relevant to canine obesity (see for details about the selected threads and videos). All comments and posts in each forum thread were included in the analysis, totaling 450 fora comments. This was also the case for two videos where there were <150 comments. Given that there were several hundred comments about the remaining three videos, the 150 most recent comments were analyzed, totaling 637 comments across the five videos.

Table 1. Summary of the forum threads and video comments analyzed.

Comments were analyzed to gain insight into participants’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors relating to canine obesity, weight management, feeding practices, and healthy lifestyles for dogs. Analyzing forum data and online comments was chosen as this was explorative research; we did not want to narrow the data based on existing assumptions, so we sought a collection method that minimized the researcher’s influence and the data were analyzed inductively to avoid constricting analysis by imposing existing ideas or frameworks onto the analysis (Braun et al., Citation2017; Clarke & Braun, Citation2014; Jowett, Citation2015). Thematic analysis was deemed to be the most suitable method of data analysis because, through the process of systematic data coding, common themes around individual’s perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors regarding canine obesity could be developed and summarized. This form of analysis is also useful for identifying the salient issues and typical responses of individuals in a particular group, and it helps with developing interventions that are attuned to this context (Degeling & Rock, Citation2020; Green & Thorogood, Citation2018). To increase rigor and further minimize the risk of the researcher’s positionality impacting the analysis, the themes developed were discussed with the wider research team during regular meetings. This allowed for triangulation of the data, to increase understanding and aid with “tussling with the data” to develop an analysis that best answered the research question (Braun & Clarke, Citation2016).

Data analysis was conducted using NVivo10 software (QSR International) after removing any identifying details (usernames, locations, pet names). First, descriptive codes were applied to individual sentences, phrases, or words that summarized the meaning. As more data were added to these codes, they were refined and grouped together in analytical themes (Clarke & Braun, Citation2014). As the themes were refined, the links between themes were established to produce a better understanding of owners’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors regarding canine obesity and weight management.

All the data used were in the public domain and used in accordance with the platforms’ regulations. The University of Liverpool’s committee on research ethics confirmed that their approval was not required for this study because the data were publicly available. To protect participants’ anonymity, direct quotes have not been presented in the results section; instead, quotes have been slightly modified from the original whilst keeping the sentiment, and identifying details such as locations or names have been changed. For example, “my parents-in-law are terrible, they are always giving Poppy pieces of cheese” could be re-written as “my partners’ parents often give Luna bits of cheese, they’re awful.” Further, instead of providing links to the forum threads and videos, the contents of these are summarized in . For example, in one forum thread (F1), an owner posted a photo of their young dog and asked other forum users whether the dog looked overweight and how much the dog should weigh. The responses included how to identify whether a dog is overweight from its appearance, whether young dogs should have a different body condition to adult dogs, and advice on weight reduction.

Results and Discussion

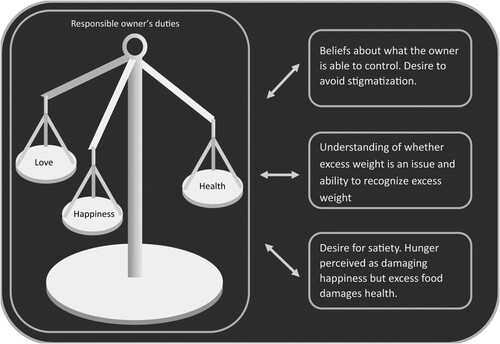

Four key themes emerged that showed individuals’ behaviors around weight management were impacted by a number of perceptions and attitudes (), including (1) Balancing conflicting responsibilities – individuals appeared to balance their responsibility in providing their dog with happiness, health, and love, and differences in emphasis placed on these impacted feeding habits and weight management; (2) Need vs. greed – individuals felt compelled to alleviate perceived hunger in their dog, which made sticking to reduced food diets difficult for some; (3) Minimizing – individuals varied in the extent to which they perceived excess body fat to be problematic, and language used to describe their dog’s body changed when excess body fat was seen as an issue; (4) Control – individuals’ perceived control over their dog’s body condition and food intake varied hugely, with some owners believing they had little to no control.

Balancing Conflicting Responsibilities

Whilst responsible ownership is generally understood to mean doing the “best for the dog,” how this is achieved varies depending on individual owners’ attitudes (Westgarth et al., Citation2019). We identified three key aspects of responsible ownership centered on the needs of the dog: ensuring health, happiness, and providing love. However, there were conflicting responsibilities around health, happiness, and love when it came to how owners fed their dogs. Some appeared to believe health and happiness were synonymous and, therefore, keeping a dog at a healthy weight was a way to ensure its happiness as well as their role as a responsible owner:

Keeping your pet healthy and happy is surely responsible ownership and means your pet will live longer. F6

Bandit was noticeably less happy after I moved away for Uni, my parents gave him lots of treats and scraps to cheer him up. F15

1: They love him too much and express it by giving him extra food.

2: They don’t love him too much, they don’t even love him enough to do what’s best for him and look after his health, he’ll be in an early grave if they keep it up. My dog is my best friend, I adore him and want to ensure he’s with me for as long as possible. F15

My father’s dog is massively overweight. Its only source of enjoyment is curling up on the sofa with my father and a treat. I don’t see an issue, the dog is loved, cared for and generally happy. F6

My pug got fat recently, he loves eating but we had to cut down his food lots, it was heart-breaking F2

Need vs. Greed

Owners discussed observing several behaviors that they perceived as indications that the dog was seeking food, including begging, stealing food, and looking for food. Some owners interpreted these behaviors as their dog being hungry, whilst others believed that their dog was being greedy ().

Table 2. Quotes showing the same behaviors could be interpreted as a dog being hungry or greedy.

Hunger was perceived as the dog legitimately needing more food and as an unpleasant feeling for the dog, which often led to giving treats, extra meals, or bigger meals:

I am of the opinion that it’s better to overfeed than underfeed! I would rather a bit of extra chub than a hungry dog! F5

He’s so greedy, always acting as if he’s starving. He would keep eating and eating if he could and it’s not because he’s actually hungry. F2

I’ve worked out how many grams he needs and I’m sticking to that, he is not getting treats or snacks. The only problem is that he’s hungry now. Is there anything else I can do to make him full? F4

Cut down his main meal and add some veg. I use cooked green beans, they’re great for increasing bulk and stop the dog feeling hungry. F7

What’s worked for my dog is making her work for her food, her meals last longer and she always seems more satisfied than when she gobbles it in seconds. F4

I know exactly what you mean about those pleading eyes when you’ve reduced their portions. I feel like I’m being really mean and I think the dog hates me for it. F14

I am guilty of giving treats. It’s the way they look at you with those pleading eyes, it’s hard not to give in. F8

Whether owners perceived their dog as feeling hungry, or being greedy, led to some differences in how they responded and felt. Owners who thought their dog was greedy expressed less emotional turmoil over ignoring its apparent desire for more food. Several owners who perceived their dog to be greedy adjusted the environmental management to ensure the dog could not access extra food or did not have opportunities to beg:

Our dog is always happy to eat more, she gets shut out of the room if she begs at the table V5

The “present bias,” whereby people tend to avoid immediate small costs even when the consequence is a greater future cost (Dolan & Kavetsos, Citation2013), might explain observations in the current study of tension in owners when dealing with the short-term cost of perceived hunger in order to achieve the longer-term benefit of successful weight reduction. In such circumstances, many owners appeared to opt for easing their dog’s perceived hunger in the short term by increasing food intake, despite this potentially detracting from the dog’s health in the longer-term. Again, reducing perceived hunger would address this issue.

Minimizing

Owners’ understanding of their dog’s body condition was complex, consistent with previous research in childhood obesity (Lachal et al., Citation2013) and equine obesity (Furtado et al., Citation2021). Many owners recognized that obesity was a risk factor for other health and wellbeing concerns. The most mentioned negative impacts were joint issues, reduced life expectancy, and reduced quality of life. These concerns provided motivation for some owners to both prevent dogs from becoming overweight and continue weight reduction for dogs that were overweight:

I am really worried about his health, I know that being overweight can have a detrimental effect and if he stays this weight he might not live much longer. F2

Poor thing, he’s not happy not being able to run and play. He tries to jump up when I come home but he’s so fat he can’t anymore. F6

I was surprised when my vet said he was overweight, I hated the idea of him being overweight and tried to argue that he was muscular, not fat. But then I cut down his food and he got slimmer. F5

Meg has always been more chunky than slight, not overweight exactly. F10

Veterinarians sometimes use humor and euphemism to discuss pet obesity, providing a means of facilitating conversations with owners about a potentially sensitive subject (Phillips et al., Citation2017). Such an approach might be counter-productive if owners interpret use of such terms to indicate that their dog is not problematically overweight. In the current study, there was divergence in the terminology owners used once they were at the point of actively attempting weight management: more clinical words such as “fat,” “overweight,” and “obese” appeared and rarely colloquial phrases that downplayed the severity of excess body fat. This, perhaps, suggests that owners shifted to using clinical terminology once they perceived excess body fat to require action. In human obesity research, the terms clinicians use when discussing obesity impact the patient’s perceived self-efficacy to change, with a diagnosis of “obesity” leading to greatest self-efficacy (Hopkins & Bennett, Citation2018). Self-efficacy, in turn, is associated with successful weight reduction and maintenance in humans (Fontaine & Cheskin, Citation1997; Mitchell & Stuart, Citation1984). However, such terms can potentially be stigmatizing and problematic for patients, who negatively perceive terms such as “fatness,” “obesity,” and “excess fat” and prefer the use of “weight problem,” “excess weight,” or discussions about body mass index (Albury et al., Citation2020; Volger et al., Citation2012). Although similar research on how language impacts animal owner’s self-efficacy is lacking, some authors have advised veterinarians to be careful about how they discuss obesity (German et al., Citation2019).

Control

Self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in their own ability to exert control over their motivation, behavior, and environment in order to achieve desired outcomes (Bandura, Citation1977; Bandura, Citation1997), and this is an aspect of many behavior-change models (Kwasnicka et al., Citation2016). Greater self-efficacy is associated with successful weight reduction and maintenance in humans (Fontaine & Cheskin, Citation1997; Mitchell & Stuart, Citation1984). In the current study, there was considerable discussion around owner’s perceived control over their dog’s body condition and food intake. The extent to which individuals believed that a dog’s food intake and body condition was within the owner’s control varied:

1: No matter how much we cut his food he won’t lose weight. We’ve tried but nothing works.

2: Sorry 1 but that’s obviously drivel. Of course he’ll lose weight if he ate less, you must still be overfeeding. F6

We have tried taking him for runs and put him on a diet. He’s not fat because I’m abusing him, he’s just a fat lab and it won’t shift. F12

Other owners acknowledged that their dog ate excessively but felt they had no control over this, often talking about the dog “sourcing their own food.” For one owner, talking about this with their veterinarian increased their perceived control and empowered them to engage actively in weight reduction:

I started her on a diet, my light-bulb moment was at the vets when I said “she eats too much” and he replied “you feed her too much.” F6

My mum acts like I’m starving him and she’s always giving him treats and junk food when she thinks I’m not looking. V4

I’m fed up with this, the dog is an imbecile, he ate too much and now he’s obese, it was his choice. V2

My dog is really overweight, I don’t know what I’m doing wrong. She doesn’t eat much and I try to get her excited about exercise but she’s not interested. I’m at my wits end. V5

There were strong attitudes and considerable stigmatization around body condition, with the target of stigma depending on whether individuals believed that the dog or the owner was in control. Stigma toward owners manifested as discussions about responsible ownership, often related to factors discussed above about ensuring health, happiness, and love for the dog. If owners were not perceived to be being responsible in these ways, they were often stigmatized and their suitability to care for a dog brought into question:

RSPCA needed! Its abuse to overfeed a dog until it can hardly walk. This isn’t love, she’s obviously suffering. What a cruel and selfish owner. V2

Future Directions, Strengths, and Limitations

This explorative study has revealed key areas where further qualitative research would be beneficial. Firstly, it is important to better understand how owners construct their role in caring for their dog and why they place emphasis on different aspects of their dog’s care. Such research might facilitate the development of targeted intervention tools for owners with different perceptions. For instance, if owners believe that giving their dog treats is important for ensuring both their dog’s happiness and their own status as a responsible owner, asking them to cut out all treats may be unachievable; instead, greater compliance might be achieved by promoting healthier treat options. Further research is also needed to explore how the perceptions of hunger and greed may be effectively addressed within a weight-management intervention. Understanding why owners attribute the emotion of hunger to their dog’s behavior may enable the development of interventions that aim to address excessive feeding in response to perceived hunger. Furthermore, interventions should take the present bias into consideration and may need to focus on decreasing the perceived immediate costs of reducing food intake and increase salience of the benefits associated with weight reduction.

As approximately 50% of owners disagree with a veterinary diagnosis of overweight or obesity for their dog (White et al., Citation2011), further research is needed into how veterinarians communicate about obesity so as to engage owners better. Beyond recognizing whether their dog was overweight, there were also variable opinions as to whether excessive body fat was an issue. Further qualitative research is required to investigate how owners mentally construct issues around the consequences of obesity and to explore the motivations of owners that engage in weight management. From this knowledge, it might be feasible to develop interventions to improve owners’ understanding of the consequences of excess body fat and motivate them to engage with weight reduction. Greater understanding of owners’ perceptions about control and self-efficacy in managing their dog’s weight will also be valuable for the development of an intervention tool that helps to increase owner empowerment and perceived control.

Analyzing online publicly available data has benefits, including ample availability of data online; minimal costs for data collection; the ability to observe the dynamic between participants in discussions; and, unlike other qualitative approaches, the presence of a researcher does not impact on the participants’ responses. However, this lack of interaction between participant and researcher means there is no opportunity to ask for clarification; therefore, researchers may have to make greater assumptions about the meaning of comments made, and these interpretations might reflect beliefs of the researcher rather than the participant. To avoid this, the analysis was carried out by a team rather than a single researcher, and multiple data sources were used to ensure that themes were not limited to opinions from a single forum. The use of multiple data sources also somewhat addressed potential concerns with self-selection bias as the demographics of users vary across the different fora.

Conclusions

This study identified complexities in owners’ management of their dogs’ weight. Recognition of excess body fat is not straightforward, and several owners appeared to believe their dog was carrying excess body fat but did not perceive this to be a health concern. Individual recognition and understanding of excess weight as a problem impacted behaviors around weight reduction and management. The restriction of food, whilst easy for some, caused conflict for owners who believed that providing food was a means of expressing love for their dog and increasing its happiness. This was exacerbated by negative perceptions about dogs experiencing hunger, resulting in owners increasing food intake to satiate their dog or looking for alternatives such as enrichment feeding. Finally, owners varied in their perceptions of control over their dog’s food intake and body condition, with responsibility not only put on others who feed it but also the dog. Further qualitative research is needed to understand how these findings may be used within weight-reduction, management, and prevention strategies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dogs Trust Canine Welfare Grants for the grant, held by Carri Westgarth, which funded Imogen Lloyd.

Disclosure Statement

Alex German is an employee of the University of Liverpool, but his position is funded by Royal Canin, part of Mars Petcare. He has received financial remuneration and gifts for providing educational material, speaking at conferences, and consultancy work. Neither Royal Canin nor Mars Petcare were involved in any aspect of the study, including funding, design, execution, data analysis, interpretation, and drafting the manuscript. Robert Christley is an employee of Dogs Trust. Imogen Lloyd's PhD stipend is funded through Dogs Trust Canine Welfare Grants. Dogs Trust was otherwise not involved in the design, execution, data analysis, or interpretation of the data. Carri Westgarth is a consultant for Forthglade Pet Food and has received financial renumeration from both them and Royal Canin for provision of educational material.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albury, C., Strain, W. D., Le Brocq, S., Logue, J., Lloyd, C., Tahrani, A. & Language Matters working group (2020). The importance of language in engagement between health-care professionals and people living with obesity: A joint consensus statement. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 8(5), 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30102-9

- Aldewereld, C. M., Monninkhof, E. M., Kroese, F. M., de Ridder, D. T., Nielen, M., & Corbee, R. J. (2021). Discussing overweight in dogs during a regular consultation in general practice in the Netherlands. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 105(S1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpn.13558

- Appleton, J., Fowler, C., & Brown, N. (2017). Parents’ views on childhood obesity: Qualitative analysis of discussion board postings. Contemporary Nurse, 53(4), 410–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2017.1358650

- Association for Pet Obesity Prevention. (2019, March 12). 2018 Press release and summary of the veterinary clinic: Pet Obesity Prevalence Survey & Pet Owner: Weight Management, Nutrition, and Pet Food Survey. Pet Obesity Prevention. https://petobesityprevention.org/2018

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H.Freeman & Co.

- Banfield. (2019). Banfield Pet Hospital. State of pet health 2019 report. https://www.banfield.com/state-of-pet-health/obesity

- Bradford, W. D., & Dolan, P. (2010). Getting used to it: The adaptive global utility model. Journal of Health Economics, 29(6), 811–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.07.007

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2016). (Mis) conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with Fugard and Potts’ (2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 19(6), 739–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1195588

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Gray, D. (2017). Innovations in qualitative methods. In B. Gough (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of critical social psychology (pp. 243–266). Springer.

- Bremhorst, A., Mills, D. S., Stolzlechner, L., Würbel, H., & Riemer, S. (2021). “Puppy dog eyes” are associated with eye movements, not communication. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.568935

- Burns, K. E., Dwyer, J. J. M., Coe, J. B., Tam, G. C. Y., & Wong, S. N. R. (2018). Qualitative pilot study of veterinarians’ perceptions of and experiences with counseling about dog walking in companion-animal practice in southern Ontario. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 45(4), 502–513. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0117-011r1

- Cairns-Haylor, T., & Fordyce, P. (2017). Mapping discussion of canine obesity between veterinary surgeons and dog owners: A provisional study. Veterinary Record, 180(6), 149–149. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.103878

- Carciofi, A. C., Gonçalves, K. N. V., Vasconcellos, R. S., Bazolli, R. S., Brunetto, M. A., & Prada, F. (2005). A weight loss protocol and owners participation in the treatment of canine obesity. Ciência Rural, 35(6), 1331–1338. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782005000600016

- Chapman, M., Woods, G., Ladha, C., Westgarth, C., & German, A. (2019). An open-label randomised clinical trial to compare the efficacy of dietary caloric restriction and physical activity for weight loss in overweight pet dogs. The Veterinary Journal, 243, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2018.11.013

- Chou, W.-y. S., Prestin, A., & Kunath, S. (2014). Obesity in social media: A mixed methods analysis. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 4(3), 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-014-0256-1

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2014). Thematic analysis. In T. Teo (Ed.), Encyclopedia of critical psychology (pp. 1947–1952). Springer.

- Courcier, E. A., Thomson, R. M., Mellor, D. J., & Yam, P. S. (2010). An epidemiological study of environmental factors associated with canine obesity. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 51(7), 362–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00933.x

- Davidson, K., & Vidgen, H. (2017). Why do parents enrol in a childhood obesity management program? A qualitative study with parents of overweight and obese children. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4085-2

- Davis, M. M., Gance-Cleveland, B., Hassink, S., Johnson, R., Paradis, G., & Resnicow, K. (2007). Recommendations for prevention of childhood obesity. Pediatrics, 120(Supplement_4), 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2329E

- Degeling, C., & Rock, M. (2012). Owning the problem: Media portrayals of overweight dogs and the shared determinants of the health of human and companion animal populations. Anthrozoös, 25(1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303712(13240472427230

- Degeling, C., & Rock, M. (2020). Qualitative research for one health: From methodological principles to impactful applications. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00070

- Degeling, C., Rock, M., & Teows, L. (2011). Portrayals of canine obesity in English-language newspapers and in leading veterinary journals, 2000–2009: Implications for animal welfare organizations and veterinarians as public educators. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 14(4), 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2011.600160

- Dolan, P., & Kavetsos, G. (2013). Educational interventions are unlikely to work because obese people aren’t unhappy enough to lose weight. BMJ, 346(7889), 24. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8487

- Downes, M. J., Devitt, C., Downes, M. T., & More, S. J. (2017, Sep). Understanding the context for pet cat and dog feeding and exercising behaviour among pet owners in Ireland: A qualitative study. Irish Veterinary Journal, 70(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13620-017-0107-8

- Eastland-Jones, R. C., German, A. J., Holden, S. L., Biourge, V., & Pickavance, L. C. (2014). Owner misperception of canine body condition persists despite use of a body condition score chart. Journal of Nutritional Science, 3, e45. https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2014.25

- Edney, A., & Smith, P. (1986). Study of obesity in dogs visiting veterinary practices in the United Kingdom. The Veterinary Record, 118(14), 391–396. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.118.14.391

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Fitzpatrick, R., & Boulton, M. (1996). Qualitative research in health care: I. The scope and validity of methods. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.1996.tb00036.x

- Fontaine, K. R., & Cheskin, L. J. (1997). Self-efficacy, attendance, and weight loss in obesity treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 22(4), 567–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(96)00068-8

- Furtado, T., Perkins, E., Pinchbeck, G., McGowan, C., Watkins, F., & Christley, R. (2021). Exploring horse owners’ understanding of obese body condition and weight management in UK leisure horses. Equine Veterinary Journal, 53(4), 752–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/evj.13360

- German, A. J. (2006). The growing problem of obesity in dogs and cats. Journal of Nutrition, 136(7), 1940–1946. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.7.1940S

- German, A. J. (2016). Weight management in obese pets: The tailoring concept and how it can improve results. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 58(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-016-0238-z

- German, A., Hervera, M., Hunter, L., Holden, S., Morris, P., Biourge, V., & Trayhurn, P. (2009). Improvement in insulin resistance and reduction in plasma inflammatory adipokines after weight loss in obese dogs. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 37(4), 214–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.domaniend.2009.07.001

- German, A. J., Holden, S. L., Bissot, T., Hackett, R. M., & Biourge, V. (2007). Dietary energy restriction and successful weight loss in obese client-owned dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 21(6), 1174–1180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2007.tb01934.x

- German, A., Holden, S., Morris, P., & Biourge, V. (2012a). Long-term follow-up after weight management in obese dogs: The role of diet in preventing regain. The Veterinary Journal, 192(1), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.04.001

- German, A., Holden, S., Wiseman-Orr, M., Reid, J., Nolan, A., Biourge, V., Morris, P., & Scott, E. (2012b). Quality of life is reduced in obese dogs but improves after successful weight loss. The Veterinary Journal, 192(3), 428–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.09.015

- German, A., & Morgan, L. (2008). How often do veterinarians assess the bodyweight and body condition of dogs? Veterinary Record, 163(17), 503–505. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.163.17.503

- German, A., Ramsey, I., & Lhermette, P. (2019). We should classify pet obesity as a disease. The Veterinary Record, 185(23), 735–735. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.l6951

- German, A. J., Woods, G. R., Holden, S. L., Brennan, L., & Burke, C. (2018). Dangerous trends in pet obesity. Veterinary Record, 182(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.k2

- German, A. J., Woods-Lee, G. R. T., Flanagan, J., & Biourge, V. (2021). Beyond the scale: A retrospective observational study of cats and dogs presenting to a referral centre with severe obesity. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 35(6), 3106–3107. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.16289

- Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2018). Qualitative methods for health research. Sage.

- Hanna, E., & Gough, B. (2016). Emoting infertility online: A qualitative analysis of men’s forum posts. Health, 20(4), 363–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459316649765

- Herwijnen, I. R. v., Corbee, R. J., Endenburg, N., Beerda, B., & Borg, J. A. v. d. (2020). Permissive parenting of the dog associates with dog overweight in a survey among 2,303 Dutch dog owners. PLoS ONE, 15(8), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237429

- Hopkins, C. M., & Bennett, G. G. (2018). Weight-related terms differentially affect self-efficacy and perception of obesity. Obesity, 26(9), 1405–1411. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22255

- Jamison, J., Sutton, S., Mant, J., & De Simoni, A. (2018). Online stroke forum as source of data for qualitative research: Insights from a comparison with patients’ interviews. BMJ Open, 8(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020133

- Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(1), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7120

- Jowett, A. (2015). A case for using online discussion forums in critical psychological research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(3), 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2015.1008906

- Kaminski, J., Waller, B. M., Diogo, R., Hartstone-Rose, A., & Burrows, A. M. (2019). Evolution of facial muscle anatomy in dogs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(29), 14677–14681. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820653116

- Kuhl, C. A., Dean, R., Quarmby, C., & Lea, R. G. (2021). Information sourcing by dog owners in the UK: Resource selection and perceptions of knowledge. Veterinary Record, 190(10), e1081. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.1081

- Kwasnicka, D., Dombrowski, S. U., White, M., & Sniehotta, F. (2016). Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: A systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychology Review, 10(3), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2016.1151372

- Lachal, J., Orri, M., Speranza, M., Falissard, B., Lefevre, H., Qualigramh, Moro, M. R., & Revah-Levy, A. (2013). Qualitative studies among obese children and adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. Obesity Reviews, 14(5), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12010

- Laflamme, D. (1997). Development and validation of a body condition score system for dogs. Canine Practice, 22(4), 10–15.

- MacInnis, C. C., Alberga, A. S., Nutter, S., Ellard, J. H., & Russell-Mayhew, S. (2020). Regarding obesity as a disease is associated with lower weight bias among physicians: A cross-sectional survey study. Stigma and Health, 5(1), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000180

- Major, B., Hunger, J. M., Bunyan, D. P., & Miller, C. T. (2014). The ironic effects of weight stigma. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 51, 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.11.009

- Mao, J., Xia, Z., Chen, J., & Yu, J. (2013). Prevalence and risk factors for canine obesity surveyed in veterinary practices in Beijing, China. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 112(3–4), 438–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.08.012

- Marshall, W., Bockstahler, B., Hulse, D., & Carmichael, S. (2009). A review of osteoarthritis and obesity: Current understanding of the relationship and benefit of obesity treatment and prevention in the dog. Veterinary and Comparative Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 22(05), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.3415/VCOT-08-08-0069

- Mitchell, C., & Stuart, R. B. (1984). Effect of self-efficacy on dropout from obesity treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52(6), 1100–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.52.6.1100

- Muñoz-Prieto, A., Nielsen, L. R., Dąbrowski, R., Bjørnvad, C. R., Söder, J., Lamy, E., Monkeviciene, I., Ljubić, B. B., Vasiu, I., & Savic, S. (2018). European dog owner perceptions of obesity and factors associated with human and canine obesity. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31532-0

- Nutter, S., Alberga, A. S., MacInnis, C., Ellard, J. H., & Russell-Mayhew, S. (2018). Framing obesity a disease: Indirect effects of affect and controllability beliefs on weight bias. International Journal of Obesity, 42(10), 1804–1811. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0110-5

- Owczarczak-Garstecka, S. C., Watkins, F., Christley, R., Yang, H., & Westgarth, C. (2018). Exploration of perceptions of dog bites among YouTube™ viewers and attributions of blame. Anthrozoös, 31(5), 537–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2018.1505260

- Pearl, R. L., Wadden, T. A., Bach, C., Leonard, S. M., & Michel, K. E. (2020). Who’s a good boy? Effects of dog and owner body weight on veterinarian perceptions and treatment recommendations. International Journal of Obesity, 44(12), 2455–2464. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-0622-7

- Pegram, C., Raffan, E., White, E., Ashworth, A., Brodbelt, D., Church, D., & O’Neill, D. (2021). Frequency, breed predisposition and demographic risk factors for overweight status in dogs in the UK. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 62(7), 521–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.13325

- Pet Food Manufacturers Association. (2019). Pet obesity ten years on. https://www.pfma.org.uk/_assets/docs/White%20Papers/PFMA-Obesity-Report-2019.pdf

- Phillips, A. M., Coe, J. B., Rock, M. J., & Adams, C. L. (2017). Feline obesity in veterinary medicine: Insights from a thematic analysis of communication in practice. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 4, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2017.00117

- Pope, C., & Mays, N. (1995). Qualitative research: Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: An introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ, 311(6996), 42–45. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.6996.42

- Porsani, M. Y. H., de Oliveira, V. V., de Oliveira, A. G., Teixeira, F. A., Pedrinelli, V., Martins, C. M., German, A. J., & Brunetto, M. A. (2020). What do Brazilian owners know about canine obesity and what risks does this knowledge generate? PLoS ONE, 15(9), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238771

- Puhl, R. M., & Heuer, C. A. (2010). Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 100(6), 1019–1028. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.159491

- Rohlf, V. I., Toukhsati, S., Coleman, G. J., & Bennett, P. C. (2010). Dog obesity: Can dog caregivers’ (owners’) feeding and exercise intentions and behaviors be predicted from attitudes? Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 13(3), 213–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2010.483871

- Rolph, N. C., Noble, P. J. M., & German, A. J. (2014). How often do primary care veterinarians record the overweight status of dogs? Journal of Nutritional Science, 3(e58), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2014.42

- Salt, C., Morris, P. J., Wilson, D., Lund, E. M., & German, A. J. (2019). Association between life span and body condition in neutered client-owned dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 33(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.15367

- Stellar, J. E., Cohen, A., Oveis, C., & Keltner, D. (2015). Affective and physiological responses to the suffering of others: Compassion and vagal activity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(4), 572–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000010

- Vedrine, B., Fernandes, D., Gérard, F., & Fribourg-Blanc, L. A. (2021). Use of an intragastric balloon for management of obesity in a dog. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 62(9), 816–821. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.13247

- Volger, S., Vetter, M. L., Dougherty, M., Panigrahi, E., Egner, R., Webb, V., Thomas, J. G., Sarwer, D. B., & Wadden, T. A. (2012). Patients’ preferred terms for describing their excess weight: Discussing obesity in clinical practice. Obesity, 20(1), 147–150. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.217

- Wainwright, J., Millar, K., & White, G. A. (2022). Owners’ views of canine nutrition, weight and wellbeing and their implications for the veterinary consultation. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 63(5), 381–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.13469

- Watkins, F., & Jones, S. (2015). Reducing adult obesity in childhood: Parental influence on the food choices of children. Health Education Journal, 74(4), 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896914544987

- Westgarth, C., Christley, R. M., Marvin, G., & Perkins, E. (2019). The responsible dog owner: The construction of responsibility. Anthrozoös, 32(5), 631–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2019.1645506

- White, G., Hobson-West, P., Cobb, K., Craigon, J., Hammond, R., & Millar, K. (2011). Canine obesity: Is there a difference between veterinarian and owner perception? Journal of Small Animal Practice, 52(12), 622–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5827.2011.01138.x

- Willmer, M., & Salzmann-Erikson, M. (2018). “The only chance of a normal weight life”: A qualitative analysis of online forum discussions about bariatric surgery. PLoS ONE, 13(10), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206066

- Wott, C. B., & Carels, R. A. (2010). Overt weight stigma, psychological distress and weight loss treatment outcomes. Journal of Health Psychology, 15(4), 608–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105309355339