ABSTRACT

People have kept companion animals for millennia, a tradition that implies mutual benefits due to its persistence; however, scientific investigations present mixed results. Some research suggests pet owners are less lonely than non-owners, but other findings suggest pet owners have higher psychological distress. Research comparing owners with non-owners is limited, and methodological inconsistencies need to be addressed. This study investigated social support and wellbeing (positive functioning) in cat and dog owners, informed by social support theory, attachment, and social exchange theories. It was hypothesized that (1) pet support would predict wellbeing in addition to human support and (2) at least one aspect of pet–owner relationship quality would influence the relationship between social support and wellbeing. An adult sample of 89 cat owners and 149 dog owners (n = 238; 205 females and 33 males) completed an online survey comprising a demographics questionnaire, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, the Cat/Dog–Owner Relationship Quality Scale, the Psychological Wellbeing Scale, and Satisfaction with Life Scale. Social support measures included some demographics on theoretical grounds to measure the construct multidimensionally. Hierarchical and multiple regressions were conducted, and results indicated that both hypotheses were supported: having more pets significantly predicted greater psychological wellbeing in addition to human social support. Unexpectedly, perceived pet support significantly, positively predicted life satisfaction when perceived emotional closeness with pet was low. These findings indicate that pets may improve psychological functioning and that emotional closeness is an important moderating factor. Practical implications include the social benefits of pets for those who could benefit from greater psychological functioning and improved life satisfaction.

It is widely believed pets fulfill social needs and improve owner wellbeing; this was recently emphasized in media reports of “pandemic pets” during the current, socially restrictive COVID-19 pandemic (Seselja, Citation2020). Cats and dogs are globally popular, constituting approximately two-thirds of pet ownership across cultures (Growth From Knowledge, Citation2016). This enduring arrangement suggests mutual benefits, and the diversion of human resources (i.e., time, living space, and finances) to these non-human dependents demonstrates their perceived value to owners (Davis & Valla, Citation1978). However, while pets receive shelter and care, the benefits to owners are less clear, with research on pet-owner wellbeing presenting mixed findings (Friedmann & Krause-Parello, Citation2018; Hughes et al., Citation2020).

Wellbeing, while lacking a universally accepted definition, can be conceptualized as feeling and functioning well (Alexandrova, Citation2015). Mental wellbeing can be conceptualized as psychological wellbeing (e.g., self-esteem, self-mastery, and autonomy; Ryff, Citation1989) and subjective wellbeing (e.g., life satisfaction and positive/negative affect balance; Diener et al., Citation1985). In older populations, pets’ benefits are often measured as reduced loneliness and psychological distress, with mixed results (Gee & Mueller, Citation2019), whereas research examining children focuses largely on positive functioning, with a robust finding of enhanced self-esteem (Purewal et al., Citation2017). Although measuring pets’ ability to reduce distress is important, we also need to understand how they impact positive functioning in adult populations (Bao & Schreer, Citation2016).

The relationship between human social support and wellbeing is well established (Cohen & McKay, Citation2020; Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2003). There is evidence that pets can enhance social support (McConnell et al., Citation2011; McConnell et al., Citation2019; Meehan et al., Citation2017) and reduce loneliness (Zasloff & Kidd, Citation1994). Conversely, other research suggests no difference in loneliness among owners and non-owners living alone, and greater loneliness and psychological distress in some owners (Antonacopoulos & Pychyl, Citation2010; Peacock et al., Citation2012), indicating the complexity of pet–owner relationships, social support, and wellbeing.

Pets’ benefits have largely been studied by comparing owners with non-owners (Friedmann et al., Citation1980; Islam & Towell, Citation2013), and findings suggest self-selection bias and inherent group differences impact outcomes (Saunders et al., Citation2017). However, randomized control trials of pet ownership are ethically fraught (e.g., some people do not want pets and animals require care; Serpell, Citation1991). Therefore, the investigation of existing pet–owner relationships requires nuanced, sound measurement, not merely comparison with non-owners. A systematic review of dogs’ and cats’ impact on wellbeing recommends defining pet numbers, species, and ownership length, as relationships over/under three years have differential impacts (Islam & Towell, Citation2013). Furthermore, evidence suggests not all pet–owner relationships are equal (Zasloff, Citation1996), and that understanding the impact of pets requires empirically sound examinations of these relationships.

Behavior problems, care needs, pet death/bereavement, and financial commitment are inherent in pet–owner relationships (Bryant, Citation1990; Dwyer et al., Citation2006; Staats et al., Citation1996). Furthermore, pet–owner relationship breakdowns and pet relinquishment are most commonly due to animal behavior and owner-related reasons such as health and finances or unexpected or perceived costs associated with pet needs, like exercise, training, and care (Coe et al., Citation2014; Jensen et al., Citation2020). Although most existing measures assess emotional pet–owner bonds, few consider costs (Staats et al., Citation1996), and most do not distinguish between interactions and emotional closeness. Moreover, there is a paucity of species-specific scales. Although some studies have combined multiple pet–owner relationship scales to gain greater understanding of these relationships (Meehan et al., Citation2017), this is impractical for most research, involving complex statistical analyses and further validation. Furthermore, pet–owner scales are commonly dog-biased, with items referring to walking pets, car trips with pets, and taking pets to visit friends (Dwyer et al., Citation2006; Johnson et al., Citation1992), inevitably resulting in cat owners scoring differently from dog owners. This study, therefore, aimed to explore the relationship between pet-derived social support and wellbeing in cat and dog owners and to understand the influence of pet–owner relationship quality on wellbeing.

Methods

Ethical approval for this study was received from the La Trobe University Low Risk Human Ethics Committee (HEC21113).

Participants

A total of 316 cat and/or dog owners began the online survey. Due to attrition, data were analyzed from 238 participants aged 19–83 years (M = 51.30, SD = 15.40), including 205 females (86%) and 33 males (14%). Over half (64%; n = 153) had completed a university degree, and 61% (n = 144) were married. Nearly all (n = 205; 86%) lived in Australia, with some participants living in the USA (n = 13; 6%) or the UK (n = 8; 4%). Nearly half (44%; n = 104) reported living with one other person, and a roughly equal number reported living alone (n = 68; 29%) or living with more than one other person (n = 66; 28%). Most participants (78%; n = 186) had no children living in the home, and 46 respondents (19%) reported living with one or two children.

Materials

Participants completed an online survey using the platform QuestionPro. In addition to standard demographics (e.g., age and gender), the questionnaire (see online supplemental file) addressed household numbers, ownership length, pet numbers and species, and pet-related questions (e.g., age). Recent evidence suggests that social restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic affected wellbeing (Zhang et al., Citation2020); therefore, pandemic-impact questions were included here (e.g., “How often have you stayed at home and only left for essential reasons?”) (1 = never, 5 = always).

To measure psychological wellbeing, conceptualized as positive psychological functioning in cat and dog owners, we used the Brief 18-item Psychological Wellbeing Scale (Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995). It includes six 3-item subscales: environmental mastery, autonomy, positive relations with others, personal growth, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. Items include, “I like most parts of my personality” and “I am good at managing the responsibilities of daily life,” with 6-point Likert-type scale response options (1 = “strongly disagree”, 6 = “strongly agree”). Scores are summed for each scale, and negatively worded items are reverse scored, resulting in a global score, with higher scores indicating greater psychological wellbeing. However, the factor structure has been disputed (Springer et al., Citation2006), leading to recommended use as a single factor/whole scale (Linley et al., Citation2009; Obst et al., Citation2019; Taylor et al., Citation2011). In community-dwelling adults and ethnically diverse college students, the single-factor structure demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 (Linley et al., Citation2009; Obst et al., Citation2019). Total scores range from 18 to 108.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) was used in this study to measure subjective wellbeing, conceptualized as a cognitive evaluation of one’s life (Diener et al., Citation1985), in adult cat and dog owners. The 5-item scale measures life satisfaction, and items include “the conditions of my life are excellent.” Responses are given on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”). Item scores are summed for a total score (range 5–35), with higher scores indicating higher life satisfaction.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Support (MSPSS), a 12-item scale with three 4-item subscales (Family, Friends, and Significant Other), measures perceived social support from distinct sources (Zimet et al., Citation1988). Items include, “my family really tries to help me” and “I can talk about my problems with my friends.” Responses are given on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = “very strongly disagree”, 7 = “very strongly agree”). Subscale scores comprise mean scores from each source, and a total score comprises a mean score of all items combined (range 1–7), with higher scores reflecting higher perceived social support.

Zimet et al. (Citation1988) recommended adapting the MSPSS to include additional sources of support for certain populations (i.e., pets for pet owners). To measure perceived pet support, Meehan et al. (Citation2017) created an adapted pet subscale, consisting of six adapted items (total 18 items), by replacing “friend/family/significant other” with “pet” (e.g., “my pet really tries to help me”). Previously, Antonacopoulos and Pychyl (Citation2008) had adapted a 4-item MSPSS dog support subscale, but Meehan et al. (Citation2017) found higher reliability with six items in their “pet” version, so the latter was used for our study. The 7-point response options and scoring remained the same as for the original MSPSS.

The Cat/Dog–Owner Relationship Scale (C/DORS), a 32-item scale with three subscales – Pet–Owner Interactions (POI), Perceived Emotional Closeness (EC), and Perceived Costs (PC) – measures cat– and dog–owner relationship quality by distinguishing between interactions with and attachment to pets, and perceived pet-ownership costs (Howell et al., Citation2017). Adapted from the Monash Dog–Owner Relationship Scale (Dwyer et al., Citation2006), the C/DORS was selected for this study owing to its relevance to cat and dog owners and because it goes beyond commonly used pet attachment scales by employing social exchange theory: integrating benefits and costs of relationships. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale, revised from the original 5-point scale to improve response variability (Riggio et al., Citation2021). The PC subscale was reverse scored, and mean scores were created for each subscale (range 1–7), with higher scores indicating better pet–owner relationship quality.

Procedure

Participants were recruited using the snowball method via personal networks, social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram), and a nationally distributed press release. Individuals aged over 18 years were eligible if they owned a cat/dog and could read and write in English, the language of the survey. Participants were informed that by proceeding to the survey they confirmed their understanding of the Participant Information Statement and consented for their responses to be used in this study.

The online survey platform QuestionPro was used. Participants could enter a draw to win an AUD$25 e-voucher and receive a results summary by providing their email address in a separate survey. Participants were informed that they could discontinue the survey at any time, and crisis support information was provided in case they felt distressed during or after participation.

Data Analysis

The software for data analysis was IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28). Scale and subscale scores were created according to authors’ instructions (Diener et al., Citation1985; Howell et al., Citation2017; Ryff, Citation1989; Zimet et al., Citation1988). Cases missing half or more outcome variable data were deleted (n = 78), and univariate outliers were winsorized to 3SD per Field (Citation2013). On the assessment of the individual variables, only PWBS, participants’ age, and C/DORS POI were normally distributed, but the remaining variables were not transformed as normality violations do not substantially affect the validity of parametric tests in samples over 200 (Field, Citation2013; Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013). Among participants with some missing data, Little’s (Citation1988) test confirmed that data were missing completely at random (i.e., Little’s test was not significant).

Some demographic variables were collapsed into composite variables (i.e., pet numbers comprised all pets, and household numbers all adults/children), and some were collapsed and recoded into dummy variables (i.e., relationship status became partner/no partner, ownership length became less than 3 years/3 years or more), based on previous findings (Islam & Towell, Citation2013). Additionally, only the COVID-19 item addressing social restrictions specifically (i.e., leaving home for essential reasons only) was included.

Inspection of P–P plots and residual scatter plots revealed linearity, normality, independence, and homoscedasticity assumptions were met for all analyses. Cooke’s distance (<1.0) indicated no influential outliers. Correlations (r < 0.7) and collinearity statistics satisfied independence and multicollinearity assumptions.

Reliability analyses determined the internal consistency of scales, and descriptive statistics were used to describe sample characteristics and variable distributions (means, standard deviations, percentages). Cat and dog scores were combined for each C/DORS subscale, then to analyze interaction effects, pet support, and C/DORS variables were standardized, and interaction terms of each perceived and structural (e.g., pet numbers) Pet Support × C/DORS pair were computed (Dawson, Citation2014). Only significant pet support variables from these linear regressions were included in later analyses. Standard multiple regression determined significant demographic predictors to be included in further analyses. Next, linear regressions were used to determine pet support predictors of wellbeing.

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to examine whether pet support predicts wellbeing in addition to human support. Step 1 included significant demographic variables from standard multiple regression above, and human support variables (i.e., perceived support and structural support, i.e., relationship status), followed by pet-derived social support in step 2, for each outcome variable (i.e., PWBS and SWLS). Age and number of pets were analyzed as continuous variables rather than being categorized into groups (e.g., age 18–25, owning three or more pets), owing to potential loss of power and risk of introducing bias in categorization (Royston et al., Citation2006).

Finally, to examine whether pet–owner relationship quality moderates the relationship between pet support and wellbeing, a series of multiple regressions were run on PWBS and SWLS to determine moderation effects. Each pet support predictor was paired with the moderator predictors (C/DORS EC, POI, PC) and their interaction terms. Significant interaction terms were probed using post-hoc simple slopes analyses.

Results

Pet-Ownership Demographics

Among the 235 participants in the study, 149 (63%) completed the C/DORS about a dog, and the remaining 89 (37%) completed it about a cat. About two-thirds of participants (67%; n = 158) had owned their pet for more than three years. Most cat owners did not own dogs (n = 106; 71%), most dog owners did not own cats (n = 64; 72%), and most participants did not own species other than dogs or cats (75%; n = 177).

Scale Reliability

contains reliability and descriptive statistics for all scales. Cronbach’s alphas demonstrated adequate to high internal consistency. This was higher than the original scales for SWLS, MSPSS, and C/DORS.

Table 1. Means (M), standard deviations (SD), ranges, and reliabilities (α) of the scales and subscales completed by cat (n = 89) and dog (n = 149) owners.

Preliminary Analyses

Control Variables

Standard multiple regression was conducted to identify statistically significant demographic predictors of SWLS and PWBS. Age, education, relationship status, and COVID-19 restrictions significantly predicted life satisfaction (R2 = 0.193, F(9,229) = 5.768, p < 0.001), and age and relationship status significantly predicted psychological wellbeing (R2 = 0.153, F(9,229) = 4.353, p < 0.001); 19.3% and 15.3% of variance in SWLS and PWBS scores, respectively, was explained by these predictors. As summarized in , positive associations of age, university education, and having a partner resulted in higher life satisfaction, and similarly, excluding education, greater psychological wellbeing. Conversely, leaving home only for essential reasons due to COVID-19 restrictions and ownership over 3 years predicted lower life satisfaction but did not predict psychological wellbeing. Pet type did not significantly predict SWLS or PWBS, indicating cats and dogs had similar effects.

Table 2. Multiple regression predicting psychological wellbeing (PWBS) and life satisfaction (SWLS) with relevant sample characteristics.

Pet Support and Wellbeing

To determine significant pet support predictors, linear regressions were conducted where SWLS and PWBS were analyzed with perceived pet support, pet numbers (M = 3, SD = 2.8, range 1–13), and ownership length, respectively (see ).

Table 3. Linear regressions predicting life satisfaction (SWLS) and psychological wellbeing (PWBS).

Perceived pet support positively and significantly predicted life satisfaction (F(1,237) = 4.285, p < 0.05), and pet numbers positively and significantly predicted psychological wellbeing (F(1,237) = 4.338, p < 0.05). All other results were not significant.

Pet Support as a Predictor of Wellbeing

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to determine if pet support predicted life satisfaction in addition to human support. Age, education, and COVID-19 restrictions were entered in Step 1, perceived and structural human support in Step 2, and perceived and structural pet support in Step 3 (see for results).

Table 4. Hierarchical regression predicting life satisfaction from control variables, human support, and pet support.

Neither structural (pet numbers) nor perceived pet support predicted life satisfaction in addition to human support and demographics, but the whole model explained 32.4% of total SWLS variance (F(7,231) = 51.058, p < 0.001). Age, relationship status, and perceived human support were the only significant predictors of SWLS, with relationship status recording the smallest beta weight and human support the largest.

Hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to test whether pet support predicted psychological wellbeing in addition to human support. Age was entered in Step 1, and, using perceived and structural variables again, human support in Step 2, and pet support in Step 3 (see for results).

Table 5. Hierarchical regression predicting psychological wellbeing from control variables.

Age, human support, and pet support positively predicted psychological wellbeing, with the whole model explaining 29% of the total PWBS variance (F(5, 222) = 18.073, p < 0.001). Pet numbers, but not perceived pet support, predicted PWBS in addition to age and human support, explaining a further 2.5% in PWBS variance (F change (2,222) = 3.834, p < 0.05).

Does Pet–Owner Relationship Quality Moderate the Relationship Between Wellbeing and Pet Support?

Multiple regression analyses examined the hypothesis that pet–owner relationship quality moderates the relationship between pet support on life satisfaction and/or psychological wellbeing. Significant pet support variables from the analyses reported above were included in these tests. Perceived pet support predicted life satisfaction, and pet numbers predicted psychological wellbeing. Pet–owner interactions (POI), emotional closeness (EC), and perceived costs (PC) were included as potential moderators. Products of perceived pet support/pet numbers and POI, perceived pet support/pet numbers and EC, and perceived pet support/pet numbers and PC were calculated. Owing to the exploratory nature of this analysis, control variables were not included.

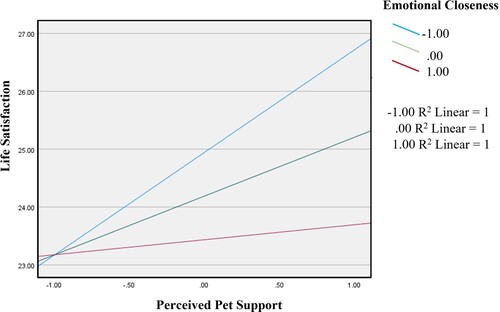

As displayed in , simple/conditional effects were not significant (Hayes et al., Citation2012), demonstrating a positive relationship between perceived pet support and SWLS at the mean level of EC and a negative relationship between EC and SWLS at the mean level of perceived pet support. A significant negative two-way interaction effect indicated the positive relationship between perceived pet support and SWLS was weakened by EC (t(3, 235) = −2.178, p < 0.05) at mean level EC (M = 5.23, SD = 1.01). Thus the prediction of life satisfaction by perceived pet support depends on the level of emotional closeness with the pet. The model explained 4.2% of the total variance in SWLS (R2 = 0.042, F(3,235) = 3.401, p < 0.001). All other interaction effects were not significant, indicating pet–owner relationship quality did not moderate the relationship between structural pet support and psychological wellbeing, and pet–owner interactions and perceived costs did not moderate perceived pet support and life satisfaction.

Table 6. Multiple regression of perceived pet support (PPS), emotional closeness (EC), and their product predicting life satisfaction. Variables were standardized.

Simple Slopes Analysis: In accordance with Dawson (Citation2014), the interaction effect of emotional closeness on the relationship between perceived pet support and life satisfaction was probed using multiple regression for simple slope analyses. High and low values of the moderator (EC) were computed at ±1 SD for ease of interpretation as per Dawson (Citation2014). summarizes the results.

Table 7. Simple slopes analyses of perceived pet support predicting life satisfaction at low and high levels of emotional closeness.

The simple relationship between perceived pet support and life satisfaction was positive and not significant at high emotional closeness, but positive and significant at low emotional closeness (see for visualization of this effect).

Figure 1. Simple slopes of moderation effects of pet–owner relationship on perceived pet support and emotional closeness.

As can be seen in , the three regression lines represent the relationships between PPS and life satisfaction when EC was set at −1 SD, the mean (i.e., zero after being centralized as part of the moderation analysis), and +1 SD, respectively. When EC was set at −1 SD, the regression line had the steepest slope, followed by the two regression lines when EC was at the mean and +1 SD. The latter two were not significant (see ). This further confirms that the negative interaction effect (see ) means that, as emotional closeness increases, the positive predictive relationship between perceived pet support and life satisfaction weakens.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore pet-derived social support and wellbeing and any moderating effect of cat– and dog–owner relationship quality. Results partially confirmed that pet support predicts wellbeing, in addition to human support, and that relationship quality moderates the relationship between pet support and wellbeing.

Pet Support and Wellbeing

Past research suggests multidimensional measurement, including measures of structural support (i.e., household numbers and relationship status), predicts wellbeing better than one aspect of social support (Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2010). Therefore, pet support measures included ownership length and number of pets, while human support included household numbers and relationship status. Perceived emotional and instrumental support from family, friends, significant others, and pets were measured, and participants tended to rate their pets as more supportive than human sources. This is unlike the research by Meehan et al. (Citation2017), which used the same measure and found pets scored lowest.

Pet numbers significantly predicted psychological wellbeing and perceived pet support significantly predicted life satisfaction, when examined without demographics and human support. This contradicts previous research using a similar support measure, where dog support did not reduce stress (Antonacopoulos & Pychyl, Citation2008). It is possible that, in our study, the number of pets reflected a higher socioeconomic status, which may explain the results. Indeed, education level, which also reflects socioeconomic status, did significantly predict satisfaction with life but not psychological wellbeing. However, comparison with previous findings is difficult, as wellbeing is commonly measured as an absence of distress. Our findings align better with recent pet-owner research, which suggests positive functioning and wellbeing in those who are mentally ill (Brooks et al., Citation2018) and adolescents (Purewal et al., Citation2017).

When demographics (i.e., age, education, and COVID-19 restrictions) and human support (i.e., relationship status and perceived support) were accounted for, perceived pet support no longer predicted life satisfaction, but pet numbers still predicted psychological wellbeing. Therefore, with each additional pet owned, psychological wellbeing improved incrementally, but the effect size was small, explaining only a further 2.5% of variance in psychological wellbeing. This also illustrates the importance of measuring demographic effects on pet–owner wellbeing (Mueller et al., Citation2021). Whether pets were owned for more or less than 3 years did not affect wellbeing, unlike previous findings demonstrating a positive relationship between ownership length and wellbeing (Islam & Towell, Citation2013).

One explanation for pet numbers, as opposed to perceived pet support, predicting psychological wellbeing, after controlling for demographics and human support, could be that structural support is more important than perceived support. Previous research suggests household numbers and number of contacts increase social support and wellbeing (Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2010), and pet ownership facilitates meeting new people and forming socially supportive human relationships, regardless of pet type owned (Wood et al., Citation2005). Recent findings during the COVID-19 pandemic indicate socially isolated pet owners had, compared with non-owners, better coping, positive emotions, and psychological wellbeing, but similar stress, anxiety, depression, and resilience (Grajfoner et al., Citation2021). This suggests that the mere presence of pets improves positive functioning, which underscores the need to measure this aspect of wellbeing. It also suggests that pet presence offers more than perceived support.

Research indicates that support given and received, and measured simultaneously, can account for nearly 40% of variance in psychological wellbeing (Obst et al., Citation2019). Pets provide opportunities to nurture, which in turn enhance self-worth and sense of purpose (Enders-Slegers & Hediger, Citation2019) and possibly account for the effect of pet numbers. Measurement of wellbeing, including positive functioning and dysfunction, could also represent pets’ effects differently, as most research suggests these are related but empirically distinct factors (Veit & Ware, Citation1983). Psychological wellbeing in the current study indicates environmental mastery, autonomy, positive social relations, personal growth, purposeful life, and self-acceptance. This perhaps indicates the benefits of simply caring for pets.

Influence of Pet–Owner Relationship Quality

Pet–owner interactions, perceived emotional closeness, and perceived ownership costs (Howell et al., Citation2017) were examined as moderators of the relationships between pet support and both wellbeing measures. As a largely exploratory exercise, demographics and human support were excluded. Relationship quality did not moderate the relationship between pet numbers and psychological wellbeing, indicating the effect of number of pets was not dependent on the perceived costs, pet–owner interaction, or emotional closeness of the pet–owner relationship. Perceived costs of ownership and pet–owner interactions were not significant moderators of life satisfaction, but emotional closeness was.

The emotional closeness subscale is theoretically similar to other pet-attachment measures (e.g., Johnson et al., Citation1992), but it is specifically designed for cat and dog owners, with items differentially corresponding to cat– and dog–owner relationships. The average level of emotional closeness was still high, which is typical of pet–owner scales (Howell et al., Citation2017), and it is reflective of owners’ perceived benefits of pets (Peacock et al., Citation2012). However, average emotional closeness weakened the positive relationship between perceived pet support and life satisfaction, making it non-significant. Post-hoc analyses revealed that when owners had low levels of emotional closeness, greater pet support significantly predicted greater life satisfaction, which is an unintuitive finding. Higher pet attachment has been related to more positive mood (Turner et al., Citation2003), but it has also been associated with greater psychological distress (Antonacopoulos & Pychyl, Citation2010; Peacock et al., Citation2012), which could explain why the positive impact of pet support on life satisfaction decreased with higher emotional closeness to pet. Perhaps people with a stronger degree of emotional closeness to their pets rely more heavily on them as a source of social support, to the exclusion of other humans. It is also possible that people who perceive a strong emotional connection with their pets also place unrealistic expectations on them regarding the extent to which they will positively impact their life.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has inherent limitations about the correlational nature of this cross-sectional online design and an increased chance of achieving false positive results owing to multiple analyses of a small sample. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution. For instance, there could be confounding variables that have not been identified and accounted for in the current study. We recommend future research that can afford a longitudinal design with panel data analysis to control for potential confounds (Hsiao, Citation2007). As the authors endeavored to utilize the available variables in the dataset, running multiple analyses risks inflation of Type I error (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013). Similarly, while we chose to leave demographic variables such as owner age and number of pets as continuous variables, this may have reduced the variability observed in the regression analyses. Categorizing the continuous variables may have better shown any patterns of association. However, we opted to use continuous variables to increase power and reduce the possibility of bias in the categorization process, as advised by Royston et al. (Citation2006).

Researching social impacts of pets during a global pandemic, while conceptually pertinent due to unprecedented societal restrictions in effect in much of the world during the data collection period, is a limitation of the present study. Nearly half the participants indicated they (often/always) left home only for essential reasons, which is in line with the social distancing requirements in force by governments in Australia at the time. Previous research indicates negative effects on life satisfaction of restrictive social measures during COVID-19 outbreaks (Zhang et al., Citation2020). However, in our study, COVID-19 restrictions only reduced life satisfaction in the context of demographic variables and not when perceived human and pet supports were added to the equation. Further investigation of the effects of pets outside this context is required for generalizability.

Ceiling effects owing to generally high perceived support, pet–owner relationship quality, and life satisfaction could have led to false effects (Austin & Brunner, Citation2003); further investigation is required to determine the replicability of these findings. The revised 7-point C/DORS response scale (up from 5 points) is still currently being validated in English, although it has been validated for dogs in Italian (Riggio et al., Citation2021). Further use measuring cat– and dog–owner relationships simultaneously is required. Participants were largely female, Australian, and university educated, and the vast majority did not have children; this limits the generalizability of our findings.

Age was a positive predictor of wellbeing, and past research suggests pet–owner relationships differ with age (Gee & Mueller, Citation2019; Purewal et al., Citation2017). Research into the effects of pets on unique populations (e.g., elders, children) suggest costs of pet–owner relationships are greater for older people, with higher incidence of injury/falls and greater impact of bereavement/pet death (Gee & Mueller, Citation2019). The C/DORS could therefore be used to further examine the social role of pet–owner relationship quality in older populations. Further, as the positive relationship between age and wellbeing suggests, younger adults tend to experience lower life satisfaction and psychological wellbeing. More research is required to ascertain the relationship between pets and wellbeing in these populations. Furthermore, the current sample was mostly women living in Australia. Therefore, the findings of this study would be most concerned with this demographic. Future replications of this study may increase the reliability and generalizability of the current findings.

Conclusion

This study built upon past research into pets and wellbeing by measuring pet–owner relationship quality with a species-specific instrument, in the context of social support and positive functioning. In addition to demographic variables and human support, psychological wellbeing increased with the number of pets owned, and life satisfaction improved with greater perceived pet support. Paradoxically, pet–owner emotional closeness weakened the positive relationship between perceived pet support and life satisfaction. Further examination of pets as social support, pet–owner relationship quality, and the impact these factors have on wellbeing is required to better understand these complex relationships.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We appreciate the study participants who took the time to share their feelings about their pet cat or dog with us. We also thank two anonymous reviewers whose suggestions helped us improve the quality of the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alexandrova, A. (2015). The science of well-being. In G. Fletcher (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of philosophy of well-being (pp. 405–417). Routledge.

- Antonacopoulos, N. M. D., & Pychyl, T. A. (2008). An examination of the relations between social support, anthropomorphism and stress among dog owners. Anthrozoös, 21(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303708X305783

- Antonacopoulos, N. M. D., & Pychyl, T. A. (2010). An examination of the potential role of pet ownership, human social support and pet attachment in the psychological health of individuals living alone. Anthrozoös, 23(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303710X12627079939143

- Austin, P. C., & Brunner, L. J. (2003). Type I error inflation in the presence of a ceiling effect. The American Statistician, 57(2), 97–104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30037242 https://doi.org/10.1198/0003130031450

- Bao, K. J., & Schreer, G. (2016). Pets and happiness: Examining the association between pet ownership and wellbeing. Anthrozoos, 29(2), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2016.1152721

- Brooks, H. L., Rushton, K., Lovell, K., Bee, P., Walker, L., Grant, L., & Rogers, A. (2018). The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1613-2

- Bryant, B. K. (1990). The richness of the child–pet relationship: A consideration of both benefits and costs of pets to children. Anthrozoös, 3(4), 253–261. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279390787057469

- Coe, J. B., Young, I., Lambert, K., Dysart, L., Nogueira Borden, L., & Rajić, A. (2014). A scoping review of published research on the relinquishment of companion animals. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 17(3), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2014.899910

- Cohen, S., & McKay, G. (2020). Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In Shelley E. Taylor, Jerome E. Singer, & Andrew Baum (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health (Vol. IV, pp. 253–267). Routledge.

- Davis, S. J., & Valla, F. R. (1978). Evidence for domestication of the dog 12,000 years ago in the natufian of Israel. Nature, 276(5688), 608–610. https://doi.org/10.1038/276608a0

- Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Dwyer, F., Bennett, P. C., & Coleman, G. J. (2006). Development of the Monash Dog Owner Relationship Scale (MDORS). Anthrozoös, 19(3), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279306785415592

- Enders-Slegers, M.-J., & Hediger, K. (2019). Pet ownership and human–animal interaction in an aging population: Rewards and challenges. Anthrozoös, 32(2), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2019.1569907

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage.

- Friedmann, E., Katcher, A. H., Lynch, J. J., & Thomas, S. A. (1980). Animal companions and one-year survival of patients after discharge from a coronary care unit. Public Health Reports, 95(4), 307. PMID: 6999524 PMCID: PMC1422527

- Friedmann, E., & Krause-Parello, C. (2018). Companion animals and human health: Benefits, challenges, and the road ahead for human–animal interaction. Revue Scientifique et Technique (International Office of Epizootics, 37(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.37.1.2741

- Gee, N. R., & Mueller, M. K. (2019). A systematic review of research on pet ownership and animal interactions among older adults. Anthrozoös, 32(2), 183–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2019.1569903

- Grajfoner, D., Ke, G. N., & Wong, R. M. M. (2021). The effect of pets on human mental health and wellbeing during COVID-19 lockdown in Malaysia. Animals, 11(9), 2689. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092689

- Growth From Knowledge. (2016). Man’s best friend: Global pet ownership and feeding trends. https://www.gfk.com/insights/mans-best-friend-global-pet–ownership-and-feeding-trends

- Hayes, A. F., Glynn, C. J., & Huge, M. E. (2012). Cautions regarding the interpretation of regression coefficients and hypothesis tests in linear models with interactions. Communication Methods and Measures, 6(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2012.651415

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

- Howell, T. J., Bowen, J., Fatjó, J., Calvo, P., Holloway, A., & Bennett, P. C. (2017). Development of the Cat–Owner Relationship Scale (CORS). Behavioural Processes, 141, 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2017.02.024

- Hsiao, C. (2007). Panel data analysis—Advantages and challenges. TEST, 16(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11749-007-0046-x

- Hughes, M. J., Verreynne, M.-L., Harpur, P., & Pachana, N. A. (2020). Companion animals and health in older populations: A systematic review. Clinical Gerontologist, 43(4), 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2019.1650863

- Islam, A., & Towell, T. (2013). Cat and dog companionship and well-being: A systematic review. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 3(6), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.ijap.20130306.01

- Jensen, J. B., Sandøe, P., & Nielsen, S. S. (2020). Owner-related reasons matter more than behavioural problems—A study of why owners relinquished dogs and cats to a Danish animal shelter from 1996 to 2017. Animals, 10(6), 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10061064

- Johnson, T. P., Garrity, T. F., & Stallones, L. (1992). Psychometric evaluation of the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS). Anthrozoös, 5(3), 160–175. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279392787011395

- Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Wood, A. M., Osborne, G., & Hurling, R. (2009). Measuring happiness: The higher order factor structure of subjective and psychological well-being measures. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 878–884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.010

- Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

- McConnell, A. R., Brown, C. M., Shoda, T. M., Stayton, L. E., & Martin, C. E. (2011). Friends with benefits: On the positive consequences of pet ownership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1239. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024506

- McConnell, A. R., Paige Lloyd, E., & Humphrey, B. T. (2019). We are family: Viewing pets as family members improves wellbeing. Anthrozoös, 32(4), 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2019.1621516

- Meehan, M., Massavelli, B., & Pachana, N. (2017). Using attachment theory and social support theory to examine and measure pets as sources of social support and attachment figures. Anthrozoös, 30(2), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2017.1311050

- Mueller, M. K., King, E. K., Callina, K., Dowling-Guyer, S., & McCobb, E. (2021). Demographic and contextual factors as moderators of the relationship between pet ownership and health. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 9(1), 701–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2021.1963254

- Obst, P., Shakespeare-Finch, J., Krosch, D. J., & Rogers, E. J. (2019). Reliability and validity of the Brief 2-Way Social Support Scale: An investigation of social support in promoting older adult well-being. SAGE Open Medicine, 7, 2050312119836020. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312119836020

- Peacock, J., Chur-Hansen, A., & Winefield, H. (2012). Mental health implications of human attachment to companion animals. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20866

- Purewal, R., Christley, R., Kordas, K., Joinson, C., Meints, K., Gee, N., & Westgarth, C. (2017). Companion animals and child/adolescent development: A systematic review of the evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030234

- Riggio, G., Piotti, P., Diverio, S., Borrelli, C., Di Iacovo, F., Gazzano, A., Howell, T. J., Pirrone, F., & Mariti, C. (2021). The dog–owner relationship: Refinement and validation of the Italian C/DORS for dog owners and correlation with the LAPS. Animals, 11(8), 2166. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/11/8/2166 https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082166

- Royston, P., Altman, D. G., & Sauerbrei, W. (2006). Dichotomizing continuous predictors in multiple regression: A bad idea. Statistics in Medicine, 25(1), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2331

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

- Saunders, J., Parast, L., Babey, S. H., & Miles, J. V. (2017). Exploring the differences between pet and non-pet owners: Implications for human–animal interaction research and policy. PLoS ONE, 12(6), e0179494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179494

- Serpell, J. (1991). Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behaviour. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 84(12), 717–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107689108401208

- Seselja, E. (2020). Puppy prices peak as scams increase fourfold on last year. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-11-24/puppy-prices-peak-dog-sale-scams-soar-amid-pandemic/12914416?utm_campaign=abc_news_web&utm_content=link&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_news_web

- Springer, K. W., Hauser, R. M., & Freese, J. (2006). Bad news indeed for Ryff’s six-factor model of well-being. Social Science Research, 35(4), 1120–1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.01.003

- Staats, S., Miller, D., Carnot, M. J., Rada, K., & Turnes, J. (1996). The Miller-Rada Commitment to Pets Scale. Anthrozoös, 9(2–3), 88–94. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279396787001509

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics. Pearson.

- Taylor, M., Bates, G., & Webster, J. D. (2011). Comparing the psychometric properties of two measures of wisdom: Predicting forgiveness and psychological well-being with the Self-Assessed Wisdom Scale (SAWS) and the Three-Dimensional Wisdom Scale (3D-WS). Experimental Aging Research, 37(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361073X.2011.554508

- Turner, D. C., Rieger, G., & Gygax, L. (2003). Spouses and cats and their effects on human mood. Anthrozoös, 16(3), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279303786992143

- Veit, C. T., & Ware, J. E. (1983). The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(5), 730. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.5.730

- Wang, H. H., Wu, S. Z., & Liu, Y. Y. (2003). Association between social support and health outcomes: A meta-analysis. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 19(7), 345–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70436-X

- Wood, L., Giles-Corti, B., & Bulsara, M. (2005). The pet connection: Pets as a conduit for social capital? Social Science & Medicine, 61(6), 1159–1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.017

- Zasloff, R. L. (1996). Measuring attachment to companion animals: A dog is not a cat is not a bird. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 47(1–2), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(95)01009-2

- Zasloff, R. L., & Kidd, A. H. (1994). Loneliness and pet ownership among single women. Psychological Reports, 75(2), 747–752. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1994.75.2.747

- Zhang, S. X., Wang, Y., Rauch, A., & Wei, F. (2020). Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2