ABSTRACT

Our aims were to describe the specific features of animal welfare offenses against companion animals in Finland, to study whether evidence provided by veterinarians was associated with the outcome of these cases, and to explore the sanctions and other legal consequences following these crimes in Finnish courts. Our data comprised 948 judgments in animal welfare offenses in Finland between January 2011 and May 2021. We used chi-square and Mann-Whitney U tests and binary logistic regression analysis to examine them. Most offenses included neglect of animals, extending to complete abandonment. We identified two distinguishable offense types that differed by offender’s age, gender, and offense location: large-scale and violent offenses. Large-scale offenses, defined as recurrent or long-lasting and involving at least 15 animals, were often located in small municipalities and led frequently to the animals’ death. They were typically committed by middle-aged or elderly women and their family members who rarely confessed to the charges even partially, which may refer to animal hoarding. In contrast, violent offenses were often committed by young men also charged with other crimes and targeted against other people’s animals, which is in line with previous research on intentional animal cruelty. The official veterinarians’ contribution to the criminal procedure varied according to the offense type. The assessment of the severity of the animal welfare offenses, imposition of a ban on the keeping of animals, and the forfeiture of the animals appeared to pose a challenge to the prosecutors and judges. We argue that to prevent and expose crimes against companion animals, we need to recognize the diverse nature of animal welfare offenses, strengthen the education of and cooperation between authorities, and efficiently utilize the ban on the keeping of animals as a precautionary measure to prevent further offenses.

In Finland, two-thirds of all animal welfare inspections and administrative measures now relate to companion animals. This change has been rapid: in 2012, most inspections still concerned production animals. Since then, the number of inspections concerning companion animals has more than doubled (Finnish Food Safety Authority, Citation2022). However, we have little knowledge of the specific features of animal welfare offenses against companion animals.

In Finland, crimes against animals are investigated by the police. On average, 150 animal welfare offenders are convicted yearly (Official Statistics of Finland, Citation2022a). Animal welfare offenses are classified as follows: animal welfare infringement (Animal Welfare Act, AWA), petty animal welfare offense, animal welfare offense, and aggravated animal welfare offense (Criminal Code of Finland, CCF). To be judged as aggravated, an animal welfare offense must be exceptionally brutal or cruel, directed at a considerably large number of animals, or have been committed to obtain considerable financial benefit, and the offense must be aggravated when assessed as a whole. For an animal welfare infringement and petty animal welfare offense, the penalty is day-fines, namely, a fine determined by the income of the defendant (AWA, CCF). For an animal welfare offense, the penalty is a fine or imprisonment with a maximum sentence of two years. For an aggravated animal welfare offense, the penalty is imprisonment from four months to four years. A penalty of up to two years of imprisonment may be imposed as conditional imprisonment with probation (CCF).

In addition, a court can ban a defendant from keeping animals for a fixed period of at least one year or permanently. Instead of a sanction, the ban is a precautionary measure to prevent a person from committing a new animal welfare offense and to protect animals from further suffering (Governmental Proposal, Citation2010). The person banned from keeping animals may not own, keep, or care for animals or otherwise be responsible for their welfare. A ban can be imposed regardless of the penalty. It should always be imposed in cases of aggravated animal welfare offenses, and it is discretionary for other offenses. A ban may be imposed permanently if the person is convicted of an aggravated animal welfare offense, if an earlier ban on the keeping of animals had been imposed for a fixed period, or if the health of the person is poor due to, for example, a permanent, serious illness, dementia, or physical weakness caused by ageing, and they are permanently unfit or unable to own, keep, or care for animals. The animals referred to in the ban on the keeping of animals and that are owned or kept by the person subject to the ban at the time that it is imposed and animals that are the subject of a violation of the ban on the keeping of animals shall be ordered forfeit to the state by the court. Both the ban and the forfeiture of the animals can be ordered at the request of the prosecutor (CCF).

Small vertebrates, such as cats and dogs, are common victims of intentional violence (DeGue & DiLillo, Citation2009; Newberry, Citation2018; van Wijk et al., Citation2018), and the number of convictions most likely underrepresents the actual number of animal welfare offenses (Alleyne et al., Citation2015; DeGue & DiLillo, Citation2009; Maher et al., Citation2017). In many countries, animal abuse is known to be used as a mechanism of domestic violence (Cleary et al., Citation2021). Violence against animals is often committed by young males (Arluke & Luke, Citation1997; van Wijk et al., Citation2018), and it may also be committed by someone other than the owner or possessor of the animal (Grugan, Citation2018; van Wijk et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, animal welfare can be compromised by passive neglect. It may emerge in its most extensive form in animal hoarding, which refers to a tendency to collect an excessive number of animals in relation to the individual’s economic or physical resources to arrange for their care (Ferreira et al., Citation2017; Patronek, Citation1999). The phenomenon has been reported in various countries (e.g., Dozier et al., Citation2019; Elliott et al., Citation2019; Felthous & Calhoun, Citation2018; Ferreira et al., Citation2017; Grugan, Citation2018; Paloski et al., Citation2017). It often involves elderly women collecting small companion animals and may originate from attempts to breed or rescue animals (Dozier et al., Citation2019; Felthous & Calhoun, Citation2018; Grugan, Citation2018; Patronek, Citation1999). Unlike in the US (Burchfield, Citation2016), the rate of reported animal welfare offenses does not associate with the violent crime rate in Finland at the municipal level (Burchfield et al., Citation2022). However, the prevalence of violent animal welfare offenses against companion animals in Finland is not known. Moreover, we have little knowledge of who commits violent crimes against animals, which species are deliberately targeted, and whether these cases are connected to other crimes. It is not known whether cases indicating animal hoarding are detected and prosecuted in Finnish courts.

The veterinarian’s role has been highlighted in animal welfare control (Väärikkälä et al., Citation2019; Valtonen et al., Citation2021) and in criminal procedures (Koskela, Citation2013; Lockwood et al., Citation2019; Parry & Stoll, Citation2020; Väärikkälä et al., Citation2020). However, according to previous research in Finland, veterinarians submitted only a small proportion of the investigation requests on offenses against companion animals (Koskela, Citation2013) and were somewhat randomly heard as witnesses (Koskela, Citation2015a). In 2009, new veterinary offices for animal welfare control were established, but it is not known whether this has affected the situation. Moreover, as we have recently shown, although complaints about violence against animals are received by the official municipal veterinarians responsible for animal welfare control, they rarely detect it on their inspections (Valtonen et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, court judgments on violations of the welfare of production animals infrequently concern violent offenses (Väärikkälä et al., Citation2020). It is not known whether this also applies to offenses against companion animals. It also remains unclear whether official veterinarians contribute to the detection and investigation of violence against animals.

The aims of this study were (1) to describe the specific features of the animal welfare offenses against companion animals, (2) to study whether different types of animal welfare offenses were prosecuted, (3) to determine whether evidence provided by veterinarians was associated with the outcome of these cases, and (4) to explore the sanctions and other legal consequences following these crimes in Finland. This will help to better understand the nature of crimes against companion animals and how to prevent them.

Methods

Ethical Approval

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Board in the Humanities and Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of Helsinki. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with national legislation and institutional requirements.

Material

Our raw data comprised 948 judgments on 1,137 defendants concerning animal welfare offenses against companion animals in continental Finland between 1 January 2011 and 20 May 2021. This time period was selected as the digitalization of judgments in district courts started to become common in 2011, thus making them easily accessible. Judgments were requested from all 19 District Courts of continental Finland. Of all defendants, 31 were prosecuted in two and five in three criminal proceedings during the analysis period. As the features and targets of the offenses and the ensuing criminal sanctions differed from case to case, all judgments on each defendant were included in the analysis as separate cases. Thus, the final data consisted of 1,137 cases. The defendants were identified by their names and birth dates in the original documents, but the data were anonymized after collecting the necessary information on age, gender, and repeated offenses.

Data Collection

The following data were collected for the analyses: (1) background variables, namely (i) the age and gender of the offender, (ii) the location of the offense (municipality), and (iii) whether the offender was accused alone or together with other persons; (2) the features of the offense, namely (i) the animal species concerned, (ii) the number of targeted animals, (iii) the duration of the offense, (iv) whether any animals died or had to be euthanized by the authorities in consequence of the offense, (v) whether the offense included violence (e.g., hitting, kicking, shooting, strangling, or otherwise actively harming the animal or killing it in an illegal manner), passive maltreatment (e.g., leaving the animal without adequate nutrition, keeping it in dirty or otherwise inappropriate premises, or leaving a sick or injured animal without veterinary care) or both, (vi) who owned the animals (offender/their ex-spouse or family member/stranger), and (vii) whether an official veterinarian had executed an animal welfare inspection and administrative measures; (3) the witnesses (official veterinarian/clinical veterinarian/veterinary pathologist/police officer/animal welfare counsellor/eyewitness/plaintiff); (4) the type of evidence (animal welfare report/clinical report/autopsy report/photographs/video footage) presented in court; (5) the possible responses of the defendants (no response/denial/partial confession/full confession to the charges); (6) the criminal sanctions imposed by the district courts, namely (i) the quality and quantity of the penalties, (ii) a possible ban on the keeping of animals and its duration, and (iii) a possible forfeiture of the animals referred to in the ban on the keeping of animals; and (7) other crimes that the defendant was charged with in the same court proceedings.

Statistical Analyses

For the statistical analyses of all cases, we defined age quintiles of the Finnish population of 15 years or older in 2014 (Official Statistics of Finland, Citation2022b), which was the median year of the occurrence of the offenses. As animal welfare offenses were relatively infrequent in the two highest quintiles, we combined them and formed the following age groups: 15–27 years, 28–40 years, 41–53 years, and 54–86 years. We scored the location of the offenses as follows: (1) small municipalities with less than 30,000 inhabitants, (2) medium-sized municipalities with 30,000–120,000 inhabitants, and (3) large municipalities with more than 120,000 inhabitants. In addition, we divided the cases into groups according to the number of the targeted animals (one animal, 2–14 animals, 15 or more animals) and the duration of the offense (1–3 days, 4–59, 60 days or longer). To explore possible cases of animal hoarding, we created a category of large-scale offense: an offense that was committed against at least 15 animals and that either lasted at least 60 days or was a repeat offense. We only included cases with 15 or more animals as hoarding cases typically involve large numbers of animals, although the literature describes individual animal hoarding cases even with fewer than 10 animals (Elliott et al., Citation2019; Ferreira et al., Citation2017).

Associations between relevant background variables, features of the offenses, and the consequences and criminal sanctions were examined with Pearson’s chi-square and z-tests. As the variables were not normally distributed, we used the Mann-Whitney U test to make comparisons between the age of the defendants charged with different types of offense and the duration and number of affected animals in the different offense types. We computed Spearman’s rank correlation to assess the relationship between the duration of the offense and the number of victim animals. The cases that were left unexamined by the courts (n = 11) were excluded from the analyses of the responses of the defendants, sanctions, bans on the keeping of animals, and forfeitures. Those defendants who were charged two or three times during the analysis period were included only once in the analysis of defendants’ age, gender, and location, using their median age and latest location of offending. Three cases were classified as both large-scale and violent offense. These cases/offenders were included in all analyses as both violent and large-scale.

Based on the univariate analyses of the relevant explanatory variables, we formed two separate logistic regression models to examine which factors best predicted the large-scale offenses (Model 1) and the violent offenses (Model 2). The explanatory variables with Pearson’s chi-square test p < 0.2 were considered potential for the logistic models. We chose this moderate inclusion criterion to avoid missing any possible predictions. For both models, the following variables were considered: age of the offender; gender of the offender; the size of the municipality where the offense was located; and whether the offender was charged alone or with another person. In addition, the variable of whether the offender was charged with other crimes not related to the animal welfare offense was considered for Model 2. Relationships between relevant explanatory variables were examined by pair-wise associations using Pearson’s chi-square test. As the gender of the offender interacted with the variable of being charged alone or with another person, the latter was excluded from both models.

As a result, we formed two models. First, to explore the large-scale offender profile (Model 1, comparing the large-scale offense to all other offenses), the main effects included in the model were the age and gender of the offender and the size of the municipality where the offense was located. Second, to form the violent offender profile (Model 2, comparing the violent offenses to all other offenses), the main effects included in the model were the age and gender of the offender, the size of the municipality where the offense was located, and whether the offender was charged with other crimes not related to the animal welfare offense. Both models were evaluated with Hosmer and Lemeshow tests of goodness of fit and ROC curve.

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was accepted at a confidence level of 95% (p < 0.05).

Results

Defendants

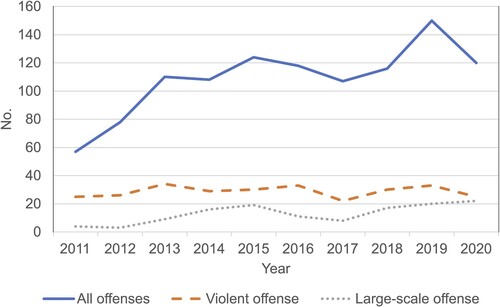

The median age of the defendants at the beginning of the suspected crime was 40 years (range = 15–86 years, SD = 15.4), and 54.6% of the defendants were male. For the distribution of the defendants in the age groups and different-sized municipalities, see . In 4.7% (54/1,137) of the cases, the defendant was charged with a repeat offense. The number of defendants rose from 57 in 2011 to 150 in 2019, dropping to 120 in 2020. The violent and large-scale offenses remained at the same level during this period ().

Table 1. The results of the univariable analysis (Pearson’s chi-square test and z-test) in cases of animal welfare offenses. Summary of explanatory variables, their distribution within all offenses (n = 1,137), and association with violent offense type (n = 299) and large-scale offense type (n = 140). Both offense types were compared with all other offenses.

The Victims and Consequences of the Offenses

The median number of affected animals was two (1–490, SD = 33.7). The most commonly targeted animals were dogs (in two-thirds of the cases), followed by cats, horses, and other species. Animals of multiple species were affected in one-fifth of the cases. The animal victim was usually owned by the offender (). For all offenses, the median duration was 36 days (range = 1–3,338, SD = 352.8).

An official veterinarian had performed at least one animal welfare inspection in 69.0% and performed administrative measures in 68.3% of the cases (). Urgent measures to provide care for an animal or to euthanize it were implemented in 50.0% (568/1,137) of the cases. One or more animals died or had to be euthanized due to the offense in 48.2% of the cases. At least one animal had died in 90.7% (39/43) of the cases that were adjudged aggravated. However, offenses that had led to an animal’s death were adjudged as an infringement or a petty offense in 12 cases.

Witnesses and Written Evidence

Veterinary evidence was presented in 83.0% of all court proceedings. A veterinarian testified orally in the court hearing in 50.0% (563/1,126) of the cases. In 33.0% (372/1,126) of the cases, only a written inspection report, patient report, autopsy report, or other statement by a veterinarian was presented as evidence. In 71.8% (808/1,126) of the cases, oral or written evidence was provided by an official municipal or state veterinarian. The defendant was found guilty of an animal welfare offense more often in the cases where an official veterinarian’s oral and/or written statement was presented as evidence (94.4%, 763/809) than in the cases with other evidence provided (85.2%, 271/317, χ2(1) = 25.8, p < 0.001). However, an oral or written statement of a clinical veterinarian alone, which was presented in 8.1% (91/1,126) of the cases, did not associate with the conviction rate (p > 0.05).

An autopsy report was presented as evidence in 33.4% (183/548) of the cases where an animal had died or been euthanized due to the offense. When an animal had died or been euthanized due to the offense, a ban on the keeping of animals was more often requested (83.1%, 152/183 of the cases) and imposed (66.7%, 122/183) with an autopsy report presented as evidence than without it (70.7%, 258/365, χ2(1) = 9.9, p < 0.001 and 52.9%, 193/365, χ2(1) = 9.5, p < 0.001). An eyewitness testified in 26.2% (295/1,126), a plaintiff in 7.5% (85/1,126), an animal welfare counsellor in 3.3% (37/1,126), and a police officer in 5.1% (57/1,126) of all cases. None of them were significantly associated with the convictions or sanctions.

Photographs and/or video footage of the animals and their premises, feed, or other relevant content were presented as evidence in 61.8% of all cases. The photographs and video footage were provided by veterinarians, police officers, plaintiffs, eyewitnesses, and defendants. The defendants were found guilty more often (93.8%, 653/696) with photographs or video recordings presented as evidence than without them (88.6%, 381/430, χ2(1) = 9.6, p = 0.002).

Responses from the Defendants and Other Charges

Of the defendants, 98.1% (1,105/1,126) responded to the charges in the preliminary investigation and/or in the court hearing, with 56.2% (633/1,126) denying their guilt, 13.7% (154/1,126) confessing partially, and 28.2% (317/1,126) confessing to all charges. One respondent could not say whether they were guilty of a crime or not.

The defendants were charged with other crimes in 14.8% of the cases (see ). Of these, 49.4% (83/168) were charged with property crimes, 18.5% (31/168) with violent offenses, 17.3% (29/168) with an invasion of domestic premises, menace, or weapons offenses, 15.5% (26/168) with narcotics offenses, 14.3% (24/168) with traffic offenses, and 29.2% (49/168) with other offenses. Of the other charges, 23.2% (39/168) concerned related crimes, such as a property crime, when the defendant had killed another person’s animal.

Sanctions and Ban on the Keeping of Animals

The courts found 90.9% of the defendants guilty of one or more animal welfare crimes. In 5.3% (55/1,034) of these cases, the defendant was found guilty of two, and in one case three, animal welfare crimes in the same court proceedings. Of those convicted, 85.1% (880/1,034) were found guilty of a basic animal welfare offense, 7.0% (72/1,034) of a petty animal welfare offense, 4.2% (43/1,034) of an aggravated animal welfare offense, and 3.8% (39/1,034) of an animal welfare infringement as their most serious crime against animals. For the imposed penalties, see .

Table 2. Sanctions on animal welfare infringement and animal welfare offenses against companion animals from 2011 to 2021.

The prosecutor called for a ban on the keeping of animals for 67.1% (751/1,137) of the defendants charged with an animal welfare offense and for 86.7% (65/75) of the defendants charged with an aggravated animal welfare offense. The prosecutor called for the forfeiture of the animals in possession of the defendant in 30.7% (349/1,137) of all cases. For the imposed bans and forfeitures, see . The forfeiture was usually imposed at the request of the prosecutor, but in five cases, it was ordered without this request.

Table 3. Other legal consequences of animal welfare infringements and animal welfare offenses against companion animals from 2011 to 2021.

A ban on the keeping of animals was imposed more often in cases of repeat offense (70.4%, 38/54) than first-time offense (47.3%, 512/1,083, χ2(1) = 11.0, p < 0.001). Although the first-time offenses of the repeat offenders lasted longer and affected more animals than the other crimes, a ban on the keeping of animals was not imposed in these cases more often than in the other first-time cases (χ2(1) = 0.002, p = 1.0).

Passive Maltreatment

In 77.8% (885/1,137) of the cases, the offense concerned passive neglect of the needs of an animal. According to the accusations, the animal premises were inappropriate (too small, dirty, or otherwise unsuitable for the species or the individual) in 65.6% (581/885) and feeding of the animal was inadequate (not giving enough or adequate food or drink to the animal) in 58.9% (521/885) of these cases.

A sick or injured animal was left without veterinary care or euthanasia in 50.7% (449/885) and the basic care of the animal (e.g., clipping overgrown claws or fur, or monitoring the welfare of the animal) had been neglected in 38.5% (341/885) of the cases. The animal had suffered from lack of exercise (dogs and horses) and/or access to urinate and defecate outdoors (dogs) in 25.0% (221/885) and one or more animals had been totally abandoned by their owner or possessor in 14.1% (125/885) of the cases.

Large-Scale Offenses

Of all cases, 12.0% (140/1,137) were categorized as large-scale offenses that were committed against at least 15 animals and either lasted at least 60 days or were repeat offenses. All large-scale offenses involved passive neglect of the animals. In 2.1% (3/140) of the cases, the offense also involved violence against animals. Of the large-scale offenses, 13.6% (19/140) were repeat offenses.

In the cases of large-scale offenses, the median age of the defendants was older (50 years, range = 16–83, SD = 14.8, n = 133) than for the other offenses (39 years, range = 15–86, SD = 15.0, n = 963, U = 86,580, p < 0.001). For large-scale offenses, most of the offenders were female (). Overall, 59.4% (79/133) of the defendants who were prosecuted for large-scale offenses were females 41 years or older, and their family members or friends, whereas 22.5% (217/963) of the other defendants belonged to this group (χ2(1) = 80.6, p < 0.001). Moreover, the large-scale offenses against companion animals were most often located in the small municipalities ().

Model 1, comparing the large-scale offenses to the other offenses, was significant (n = 1,137, χ2(1) = 96.0, p < 0.001). The area under the ROC curve was 74% (CI = 69–78%, p < 0.001), and the p-value for the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit test was 0.5 (χ2 = 7.3). Belonging to the two highest age groups, female gender, and location in a small municipality predicted the large-scale offenses ().

Table 4. Binary logistic regression analysis of the factors predicting the charges of large-scale offenses (n = 133) as compared with all other offenders (n = 963).

Animals died or had to be euthanized more often as a consequence of large-scale offenses than because of other offenses (). The majority of the large-scale offenses involved several animal species. Although dogs were involved in most cases, all other species groups were represented more often in these cases than in the other offenses (). Other species included hens, pigeons, ducks, geese, quails, parrots, rats, mice, hamsters, degus, guinea pigs, rabbits, chipmunks, snakes, geckos, frogs, toads, snails, turtles, fish, pigs, goats, sheep, cattle, donkeys, hedgehogs, wolves, and foxes.

An animal welfare inspection had been performed in every case of a large-scale offense, and a veterinarian’s oral and/or written statement was presented as evidence in all court proceedings. In 89.3% (125/140) of these cases, a veterinarian testified orally in the proceedings (for other offenses, 44.1%, 440/997, χ2(1) = 100.1, p < 0.001). Photographs and/or video footage were also presented more often in large-scale cases than in the other cases ().

When the offense was of a large-scale type, most defendants (77.0%, 107/139) denied having committed a crime (of other defendants, 55.5%, 548/987, χ2(1) = 23.1, p < 0.001). However, unlike in the other cases, denying the charges had no significant association with whether the defendant was convicted (χ2(1) = 0.2, p = 1.0). Further, when the defendant was convicted, a ban on the keeping of animals and forfeiture of the animals were imposed more often in cases of large-scale offenses than the other offenses. Large-scale offenses were also prosecuted and judged as aggravated more often than other offenses ().

For the large-scale offenses, the defendants were charged with other types of crime in 17.1% (24/140) of the cases, not differing significantly from the other offenses. However, the other crimes were related to the animal welfare offense more often (45.8%, 11/24) than in other cases (19.4%, 28/144, χ2(1) = 8.0, p = 0.008). Typically, another person’s property was damaged by animal feces or carcasses.

Violent Offenses

In 26.3% (299/1,137) of the cases, the offense included violence against an animal. These cases involved hitting or kicking the animal in 30.4% (91/299), injuring or killing the animal with a knife, an axe, or other tool in 29.8% (89/299), and strangling or crushing the animal or its body parts in 23.1% (69/299) of the cases. In 20.4% (61/299) of the cases, the animal was slammed to the ground or dropped from a high place, and in 8.0% (24/299) of the cases, it was shot. In 15.1% (45/299) of the cases, the animals were killed or injured in other ways: for example, by drowning, poisoning, or burning. In 16.7% (50/299) of the violent offense cases, the defendant was accused of both passive neglect and violent abuse of an animal.

In the cases of violent offense, the median age of the defendants was younger (37 years, range = 15–86, SD = 15.4, n = 299) than in the passive cases (41 years, range = 16–85, SD = 15.1, n = 797, U = 103,998, p < 0.001). The majority of the violent offenders were male. Violent offenses occurred more often in large municipalities than in small or medium-sized municipalities. Moreover, the violent offenders were prosecuted alone more often than other offenders (). The violent offenses did not include any repeat offenses.

Model 2, comparing the violent offenses to the other offenses, was statistically significant (n = 1,137, χ2(1) = 172.5, p < 0.001). The area under the ROC curve was 75% (CI = 71–78%, p < 0.001), and the p-value for the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit test was 0.6 (χ2 = 6.8). Belonging to the two lowest age groups, male gender, location in a large municipality, and charges with other crimes predicted the violent offenses ().

Table 5. Binary logistic regression analysis of the factors predicting the charges of violent offenses (n = 299), as compared with all other offenders (n = 797).

Nearly half of the violent offenses were targeted against another person’s animals, whereas this was rare in the other cases (). Of the owners of violently abused animals, 26.1% (78/299) were spouses, ex-spouses, or other family members of the perpetrator, and 21.1% (63/299) were unknown to the perpetrator (e.g., passers-by).

In most cases, the affected animal was a dog. Horses, cats, and other species were involved less frequently when compared with the other cases (). Other species included rabbits, guinea pigs, parrots, hens, and llamas. An official veterinarian performed at least one animal welfare inspection in only one-quarter of all cases of violent offense (). This was even rarer in cases where no passive maltreatment was involved, with an inspection rate of 14.1% (35/249) vs. 80.0%, (40/50) in cases involving only passive maltreatment (χ2(1) = 96.4, p < 0.001). Moreover, the official veterinarians had performed administrative measures less often in the cases of violent offense than in other cases ().

A veterinarian testified less frequently in the cases of violent than non-violent offense (). More specifically, an official municipal or state veterinarian testified in 30.4% (90/296) of the cases of violent offense, which was significantly rarer than in the other cases (86.5% (718/830), χ2(1) = 338.8, p < 0.001). Veterinary evidence was not associated with the court finding the defendant guilty.

Of the cases examined by court, an eyewitness testified more often in the cases of violent offense (43.6%, 129/296) than in the cases of passive offense (10.0%, 166/830, χ2(1) = 62.8, p < 0.001). Similarly, a plaintiff testified in 20.6% (61/296) of the cases of violent offense and in 2.9% (24/830) of the cases of passive offense (χ2(1) = 98.1, p < 0.001). Photographic and/or video evidence were presented less often in cases of violent offense (). None of these, nor the death of the victim animal, or a police officer’s or an animal welfare counsellor’s testimony, had a significant association with the defendant being convicted or banned from keeping animals. Overall, the charges were more often dismissed and a ban on the keeping or forfeiture of the animals less often imposed in the cases of violent offense ().

The court mitigated the crime or the penalty or rejected the prosecutor’s call for a ban on the keeping of animals in 14.2% (42/296) of the cases of violent offense, assessing the suffering as not long-lasting or otherwise exceptionally cruel, or emphasizing that the crime had occurred only once. In these cases, even inflicting intense mutilating or deadly violence against an animal and causing it to suffer from minutes to hours was defined as brief or one-time, whereas, in other cases, causing essentially similar prolonged suffering was typically evaluated as exceptionally cruel and/or resulted in a ban on the keeping of animals.

The defendants in the cases of violent offense against an animal were more often charged with other crimes than the other defendants (). Moreover, they were more often charged with violent offenses, invasion of domestic premises, menace, or weapons offenses (43.4%, 33/76) than the other defendants (20.7%, 19/92, χ2(1) = 10.1, p < 0.001). Of the additional charges, 22.4% (17/76) concerned property crimes or invasion of domestic premises that were related to the animal welfare offense.

Discussion

Our aims were to describe specific features of animal welfare offenses against companion animals and to study whether different types of animal welfare offenses were prosecuted in Finland. Further, we examined whether evidence provided by veterinarians was associated with the outcome of these cases and explored the sanctions and other legal consequences following these crimes.

The offenses against companion animals could be roughly classified by the features of the offense. We identified two distinguishable albeit partially overlapping types: large-scale and violent offenses. The typical offenders varied according to the offense type. The official veterinarians’ contribution to the criminal procedure concerning the passive neglect of animals and especially large-scale offenses was significant throughout the process, from inspecting the animals and their premises to providing documentation and testifying in the court proceedings. In contrast, in the cases of violent offenses, the veterinary inspections and evidence were an irregular element of the criminal procedure. Possibly due to this, the assessment of the severity of the animal welfare offenses, requesting and ordering a ban on the keeping of animals, and forfeiting animals subjected to a crime appeared to pose a challenge to the prosecutors and judges. The prosecuted offenses against companion animals can be considered serious as nearly half of them resulted in the death of victim animals and some of these were even adjudged infringements or petty offenses. This is in line with the results of Väärikkälä et al. (Citation2020) concerning crimes against cattle and pigs, and our previous finding of official veterinarians reporting violations of animal welfare legislation to the police only rarely (Koskela, Citation2013).

Passive neglect of the basic needs of animals, extending to complete abandonment, was committed in 78% of all cases. It included failures to provide appropriate premises, food, exercise, other basic care, or necessary veterinary care for animals. We defined the offenses that either recurred at least once or lasted for two or more months, and involved at least 15 animals, as large-scale offenses. They can be described as a subtype of passive offenses, as they nearly exclusively included passive neglect of the animals. Large-scale offenses were mainly located in small municipalities and resulted more often in the animals’ death than other offenses. Further, nearly 60% of them were committed by middle-aged or elderly women and their family members, who rarely confessed to the charges even partly. Nevertheless, official veterinarians testified regularly in the court proceedings, photo and/or video footage and autopsy reports were frequently presented as evidence, and the defendants were almost invariably found guilty. These features may refer to animal hoarding, as it is typical of elderly female hoarders that they fail to regard themselves as harming the animals even despite the dead or dying animals in their household (Dozier et al., Citation2019; Patronek, Citation1999). However, as Henry (Citation2018) points out, an act of passive neglect may also be intentional. The passive offense type thus varies as to the level of intentions as well as consequences, and phenomena such as “puppy farms” and the smuggling of companion animals may also be connected to large-scale offenses.

In contrast to cases of passive neglect, violent crimes against companion animals were more typically committed by young men, located in an urban environment and often targeted against other people’s animals. The violent offense type included deliberate violence against an animal, and the offenders were charged with other crimes, especially violent offenses, invasion of domestic premises, menace, or weapons offenses more often than those charged with the passive offense type. This is in line with various studies on self-reported animal cruelty and questionnaires on attitudes toward animals that describe the young male offenders and indicate animal abuse to co-occur with other criminal behavior (Connor et al., Citation2021; Grugan, Citation2018; Plant et al., Citation2019; Schwartz et al., Citation2012; Walters, Citation2019). It also suggests the link between domestic violence and animal abuse well demonstrated in research (Cleary et al., Citation2021; Lucia & Killias, Citation2011), which, however, does not appear when explored at the community level in Finland (Burchfield et al., Citation2022).

We argue that to prevent and expose crimes against companion animals more efficiently, we need to recognize the diverse nature of animal welfare offenses. We agree with Elliott et al. (Citation2019) that veterinarians’ readiness to identify and report hoarders is essential to initiate the control process and help the animals. However, the typical unwillingness of hoarders to provide veterinary care for their animals (e.g., Lockwood, Citation2018) may make them rare clients in veterinary practice. Further, as Patronek and Nathanson (Citation2009) underline, the problem of animal hoarding needs to be addressed as recurrent behavior that requires long-term interventions from health-care services. Removing one set of animals from the hoarder solves the problem only temporarily (Lockwood, Citation2018; Patronek & Nathanson, Citation2009). Our current study shows that when the offenses escalated to the large-scale type, the proportion of cases resulting in dead animals increased by 22%. We thus highlight the importance of the training and cooperation of official and clinical veterinarians, the police, and social work authorities to be able to recognize and intervene in serious, potentially protracted situations early and effectively. A proactive collaborative model has been piloted in the United States (Strong et al., Citation2019) and its introduction into wider use should be considered. Further, we agree with Koskela (Citation2015b) that efficient control of the ban on the keeping of animals is essential to protect further animals against crimes.

We discovered that the official veterinarians testified in less than one-third of court proceedings when the offense involved violence against animals. Further, unlike offenses entailing only passive neglect, neither oral nor written veterinary evidence increased the probability of conviction in these cases. Even the death of the animal victim due to a violent offense did not increase the conviction rate or the probability of requesting or imposing bans on the keeping of animals. Overall, the charges were dismissed more often than in the cases of passive offenses. Plaintiffs and eyewitnesses were frequently heard in court proceedings, but this was not associated with the conviction rate. Official veterinarians’ role in intervening in the passive neglect of animals, initiating investigation processes, documenting the maltreatment, and testifying in court proceedings has been emphasized in previous research (Koskela, Citation2013; Väärikkälä et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Valtonen et al., Citation2021). In addition, the prosecutors considered veterinary documentation with photographic material as the most important type of evidence in court proceedings (Lockwood et al., Citation2019). However, according to our recent study, the veterinarians’ contribution to detecting violent offenses against animals by means of official animal welfare control seems rather limited (Valtonen et al., Citation2021). Based on our current results, we argue that the lack of expertise may pose a challenge also at the level of police investigations and courts. We suggest that when a violent crime against an animal is suspected, the preliminary investigation procedure should always include a thorough clinical examination and, in the event of the animal’s death, an autopsy report. In addition to veterinarians, other experts on animal behavior, for example, could be considered as witnesses.

Nearly half of the violent offenses prosecuted in court were committed against another person’s animal. This is not likely to reflect the usual relationship between the animal victim and the violent perpetrator but rather highlights that to obtain justice, the animal must have a voice in the criminal procedure. This voice is either that of its owner, an occasional eyewitness, or an animal welfare authority. Furthermore, this finding highlights the well-known link between domestic violence and violence against animals. Based on our results, we suggest that the awareness of this link should be ensured in the training of the police and prosecutors. In this context, it is also vital to recognize the distress of a plaintiff or eyewitness who may themselves be a victim of domestic violence either directly or through the perpetrator harming the animal.

In cases of violent animal welfare offenses, the judges regularly rationalized dismissing the charges, mitigating the sentence, or not imposing a ban on the keeping of animals by defining the suffering caused to the animal as relatively short or mild, even when it resulted in prolonged pain and agony before death or in serious injuries. This led to incoherent interpretations among judges: for example, essentially identical cases of strangling or suffocating animals resulted in very different sentences, from a petty offense to a basic offense with a high fine and a ban on the keeping of animals. We underline that a large body of research shows the ability of various animal species to experience pain and suffering (e.g., Sneddon et al., Citation2014; Weary et al., Citation2006) and suggest that education should be provided for prosecutors and judges to clarify the basic facts of animal cognition and the legal concept of unnecessary pain and suffering. Further, as what constitutes an exceptionally brutal or cruel offense is not exhaustively defined in the legislation, the interpretation might benefit from specific expertise in animal welfare. We agree with Koskela (Citation2019), who has suggested utilizing an external animal welfare expert in the court proceedings or allocating animal welfare offenses to a limited number of judges to provide and accumulate the necessary knowledge of the crime type.

When the prosecutors requested a ban on the keeping of animals, they called for forfeiture of the animals in the possession of the defendant in less than half of the cases. This was rare considering that the Criminal Code of Finland requires that the animals in the possession of the defendant at the time of imposing the ban are forfeited to the state. However, to be imposed by the judge, the forfeiture must be requested by the prosecutor. We could not find an explanation for the missing requests. We suggest that this threshold for ordering the forfeiture should be removed to enable judges to effectively prevent further offenses. Also, we highlight the nature of the ban on the keeping of animals as a precautionary measure to prevent further suffering of the animals. The forfeiture of the animals already subjected to a crime, or in danger of getting harmed, is an essential part of this.

The number of defendants rose during the analysis period until a decrease in 2020. The overall rise can be explained by the establishment of specific veterinary offices for animal welfare control since 2009 (Veterinary Care Act, Citation2009); more resources have been directed to the official animal welfare inspections, with a simultaneous growth in the relative share of inspections targeted at companion animals. With a reduction in the overall number of convictions for all crime types (Official Statistics of Finland, Citation2022a), the drop in 2020 was most probably caused by the court congestion due to the COVID-19 pandemic (National Court Administration Finland, Citation2020). Interestingly, the numbers of violent offenses and large-scale offenses remained essentially unchanged despite the overall increase in the number of defendants. We suggest that, considering the findings that veterinarians are more active both in detecting (Valtonen et al., Citation2021) and witnessing passive maltreatment of animals, the steady number of violent offenses supports the assumption that the increase in the overall number of cases is due to the stronger resources of animal welfare control. Further, it can be assumed that large-scale cases are prioritized when resources are low and that additional resources might enable the control system to follow a criminal procedure in less extensive cases as well. However, we could not identify any corresponding patterns regarding, for example, the proportion of aggravated offenses or imposed bans on the keeping of animals. More thorough content analysis of the judgments and classification of the seriousness of the criminal acts against animals would be needed to further assess the increase in cases of animal welfare offenses in courts.

There are certain limitations to our study. We could only record those additional crimes that transpired from the same convictions with the animal welfare offenses. To further explore the connection between animal welfare crimes and other crimes, linking the individual offenders to other register data would be necessary. Moreover, the views and justifications of the offenders and their influence on the judgments were not examined in this study, and further research would be needed to shed light on the motives and rationalizations behind the animal welfare offenses.

Conclusions

Animal welfare offenses in Finland include passive neglect, large-scale offenses, and violent offenses that differ from each other regarding the defendant’s age, gender, location, and the ensuing legal consequences. The assessment of the severity of animal welfare offenses clearly poses a challenge to prosecutors and judges. Protecting animals from further suffering by requesting and imposing a ban on the keeping of animals and forfeiture of animals appears arbitrary. We argue that to prevent and expose crimes against companion animals, we need to recognize the diverse nature of animal welfare offenses, strengthen the education of and cooperation between authorities, and efficiently utilize the ban on the keeping of animals as a precautionary measure to inhibit further offenses.

Disclosure Statement

The first author has given a statement as an official veterinarian in court in 38 of the 1,137 cases included in the study material. For the other authors, there is no potential competing interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alleyne, E., Tilston, L., Parfitt, C., & Butcher, R. (2015). Adult-perpetrated animal abuse: Development of a proclivity scale. Psychology, Crime & Law, 21(6), 570–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2014.999064

- Animal Welfare Act. (247/1996). https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1996/en19960247_20061430.pdf.

- Arluke, A., & Luke, C. (1997). Physical cruelty toward animals in Massachusetts, 1975–1996. Society & Animals, 5(3), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853097X00123

- Burchfield, K. B. (2016). The sociology of animal crime: An examination of incidents and arrests in Chicago. Animals, 37, 368–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2015.1026769

- Burchfield, K. B., Markowitz, F. E., & Koskela, T. (2022). An examination of community-level correlates of animal welfare offenses and violent crime in Finland. International Criminology, 2(2), 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43576-021-00039-6

- Cleary, M., Thapa, D. K., West, S., Westman, M., & Kornhaber, R. (2021). Animal abuse in the context of adult intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 61, 101676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2021.101676

- Connor, M., Currie, C., & Lawrence, A. B. (2021). Factors influencing the prevalence of animal cruelty during adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(7–8), 3017–3040. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518771684

- Criminal Code of Finland. (39/1889). https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/1889/en18890039_20150766.pdf.

- DeGue, S., & DiLillo, D. (2009). Is animal cruelty a “red flag” for family violence? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(6), 1036–1056. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508319362

- Dozier, M. E., Bratiotis, C., Broadnax, D., Le, J., & Ayers, C. R. (2019). A description of 17 animal hoarding case files from animal control and a humane society. Psychiatry Research, 272, 365–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.127

- Eläinlääkintähuoltolaki. (765/2009). [Veterinary Care Act 765/2009]. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2009/20090765?search%5Btype%5D = pika&search%5Bpika%5D = el%C3%A4inl%C3%A4%C3%A4kint%C3%A4huoltolaki.

- Elliott, R., Snowdon, J., Halliday, G., Hunt, G., & Coleman, S. (2019). Characteristics of animal hoarding cases referred to the RSPCA in New South Wales, Australia. Australian Veterinary Journal, 97(5), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/avj.12806

- Felthous, A. R., & Calhoun, A. J. (2018). Females who maltreat animals. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 36(6), 752–765. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2390

- Ferreira, E. A., Paloski, L. H., Costa, D. B., Fiametti, V. S., De Oliveira, C. R., de Lima Argimon, I. I., Gonzatti, V., & Irigaray, T. Q. (2017). Animal hoarding disorder: A new psychopathology? Psychiatry Research, 258, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.030

- Finnish Food Safety Authority. (2022). Eläinten Hyvinvoinnin Valvonta 2021 [Animal Welfare Control 2021]. https://www.ruokavirasto.fi/globalassets/viljelijat/elaintenpito/elainten-hyvinvointi/2021-tarkastukset/elainten-hyvinvoinnin-valvonta-2021.pdf.

- Grugan, S. T. (2018). The companions we keep: A situational analysis and proposed typology of companion animal cruelty offenses. Deviant Behavior, 39(6), 790–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2017.1335513

- Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle laeiksi rikoslain 17 luvun muuttamisesta ja eläintenpitokieltorekisteristä sekä eräiden niihin liittyvien lakien muuttamisesta HE 97/2010 [Governmental proposal to parliament concerning chapter 17 of the criminal code of Finland and the register for bans on the keeping of animals]. (2010). https://www.finlex.fi/fi/esitykset/he/2010/20100097.

- Henry, B. (2018). A social-cognitive model of animal cruelty. Psychology, Crime & Law, 24(5), 458–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2017.1371306

- Koskela, T. (2013). Eläinsuojelutarkastus ja eläinsuojelurikosepäilystä ilmoittaminen - kansalaisaktiivisuutta vai viranomaisvalvontaa? [Animal welfare inspection and reporting of suspected animal welfare crime – active citizenship or regulatory oversight? ]. Edilex, 2013/22, 1–32.

- Koskela, T. (2015a). Asiantuntijat eläinsuojelurikosasioissa – onko niitä? [Experts in animal welfare crimes – Do they exist?]. Edilex, 2015/23, 1–30.

- Koskela, T. (2015b). Eläintenpitokieltorekisteri valvonnan välineenä—Toteutuuko eläintenpitokieltorekisterilain tarkoitus ja tavoitteet? [The register of persons banned from keeping animals as a tool of control—Are the purpose and aims of the related legislation fulfilled?]. Edilex, 2015/40, 1–38.

- Koskela, T. (2019). Törkeä eläinsuojelurikos – vai onko? [An aggravated animal welfare offense – or is it?]. Edilex, 2019/19, 1–25.

- Lockwood, R. (2018). Animal hoarding: The challenge for mental health, law enforcement, and animal welfare professionals. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 36(6), 698–716. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2373

- Lockwood, R., Touroo, R., Olin, J., & Dolan, E. (2019). The influence of evidence on animal cruelty prosecution and case outcomes: Results of a survey. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 64(6), 1687–1692. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.14085

- Lucia, S., & Killias, M. (2011). Is animal cruelty a marker of interpersonal violence and delinquency? Results of a Swiss national self-report study. Psychology of Violence, 1(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022986

- Maher, J., Pierpoint, H., & Beirne, P. (2017). The Palgrave international handbook of animal abuse studies (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- National Court Administration Finland. (2020). Time and significant resources needed to clear backlog of court cases. https://tuomioistuinvirasto.fi/en/index/ajankohtaista/currentissues/2020/timeandsignificantresourcesneededtoclearbacklogofcourtcases.html.

- Newberry, M. (2018). Associations between different motivations for animal cruelty, methods of animal cruelty and facets of impulsivity. Psychology, Crime & Law, 24(5), 500–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2017.1371305

- Official Statistics of Finland. (2022a). Sentences by citizenship, place of residence and offense. https://pxweb2.stat.fi/PxWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__syyttr/statfin_syyttr_pxt_126p.px/.

- Official Statistics of Finland. (2022b). Key figures on population by region, 1990–2021. https://pxdata.stat.fi/PxWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__vaerak/statfin_vaerak_pxt_11ra.px/.

- Paloski, L. H., Ferreira, E. A., Costa, D. B., Huerto, M. L. d., Oliveira, C. R. d., Argimon, I. I. D. L., & Irigaray, T. Q. (2017). Animal hoarding disorder: A systematic review. Psico: Revista Semestral Do Instituto de Psicologia Da PUC Rio Grande Do Sul, Brasil, 48(3), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-8623.2017.3.25325

- Parry, N. M. A., & Stoll, A. (2020). The rise of veterinary forensics. Forensic Science International, 306, 110069–110069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.110069

- Patronek, G. J. (1999). Hoarding of animals: An under-recognized public health problem in a difficult-to-study population. Public Health Reports, 114(1), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/phr/114.1.81

- Patronek, G. J., & Nathanson, J. N. (2009). A theoretical perspective to inform assessment and treatment strategies for animal hoarders. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.006

- Plant, M., van Schaik, P., Gullone, E., & Flynn, C. (2019). “It’s a dog’s life”: culture, empathy, gender, and domestic violence predict animal abuse in adolescents—Implications for societal health. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(10), 2110–2137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516659655

- Schwartz, R. L., Fremouw, W., Schenk, A., & Ragatz, L. L. (2012). Psychological profile of male and female animal abusers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(5), 846–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260511423254

- Sneddon, L. U., Elwood, R. W., Adamo, S. A., & Leach, M. C. (2014). Defining and assessing animal pain. Animal Behaviour, 97, 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.09.007

- Strong, S., Federico, J., Banks, R., & Williams, C. (2019). A collaborative model for managing animal hoarding cases. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 22(3), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2018.1490183

- Väärikkälä, S., Hänninen, L., & Nevas, M. (2019). Assessment of welfare problems in Finnish cattle and pig farms based on official inspection reports. Animals, 9(5), 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9050263.

- Väärikkälä, S., Koskela, T., Hänninen, L., & Nevas, M. (2020). Evaluation of criminal sanctions concerning violations of cattle and pig welfare. Animals, 10(4), 715. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10040715

- Valtonen, E., Koskela, T., Valros, A., & Hänninen, L. (2021). Animal welfare control—Inspection findings and the threshold for requesting a police investigation. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 736084–736084. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.736084

- van Wijk, A., Hardeman, M., & Endenburg, N. (2018). Animal abuse: Offender and offense characteristics. A descriptive study. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 15(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1499

- Walters, G. D. (2019). Animal cruelty and bullying: Behavioral markers of delinquency risk or causal antecedents of delinquent behavior? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 62, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.11.008

- Weary, D. M., Niel, L., Flower, F. C., & Fraser, D. (2006). Identifying and preventing pain in animals. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 100(1–2), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2006.04.013