ABSTRACT

Many traditional horse keeping and training practices can result in poor horse welfare. To assist reform and identify novel opportunities to facilitate improvements in horse welfare, this study sought to gauge the motivations underlying equestrians’ horse-keeping and training practices. Nineteen amateur equestrians were interviewed using semi-structured interviews. Systems thinking and self-determination theory, which proposes humans are intrinsically motivated by three psychological needs (competence, autonomy, and relatedness), provided the theoretical framework for the study. Using reflexive thematic analysis, four themes were identified: (1) achieving equestrian goals is the primary motivator; (2) equestrians work hard to develop their equestrian knowledge and skills; (3) equestrians are highly motivated to compete and/or participate in club activities; and (4) achieving a financial return on investment is important to many equestrians. Findings suggest that equestrians do not prioritize the three psychological needs proposed by self-determination theory equally. Competence (goal achievement) was the highest priority for equestrians, followed by the need for autonomy (control), and then relatedness (horse–human partnership). The spectrum of equestrians’ motivational priorities suggests that there is an imbalance between horse needs and human needs when selecting horse-keeping and training practices. These insights can be leveraged to develop initiatives that engage all stakeholders, so that meeting human needs and horse needs is more equitably balanced. We also found that equestrians’ practices were highly influenced by their desire to participate in competitive equestrian sport, emphasizing the important role equestrian organizations can play in improving horse welfare through the rules of their sports. These findings contribute to the multifaceted reform needed to solve the complex challenge of improving horse welfare, the outcome of which will determine the long-term future of equestrian sport.

Many traditional horse-keeping and training practices can result in poor horse welfare. For example, the welfare insults from stabling are well documented (Lesimple et al., Citation2016; Sykes et al., Citation2019), yet stabling remains the mainstay of elite performance-horse housing (Ruet et al., Citation2019; Werhahn et al., Citation2012). Equally, the negative welfare outcomes associated with aversive training practices, such as whipping in racing (Evans & McGreevy, Citation2011; McGreevy et al., Citation2013), are also well documented, yet many in the industry resist calls to ban whipping (Wood, Citation2023). The gap between industry practices and those supported by scientific evidence exists at a time when the social license to operate, a concept describing tacit community approval for an industry, for equestrian sport is under threat (Heleski, Citation2023). A key element of social license to operate is credibility, which is the extent to which an industry is believable (Jijelava & Vanclay, Citation2017). At present, the divergence between what the horse industry maintains, that is, “that horse welfare is our highest priority,” and what it does contributes to declining community acceptance of equestrian sport (Jijelava & Vanclay, Citation2017; Prno & Slocombe, Citation2012). Adopting evidence-based practices that improve horse welfare would improve the industry’s credibility (Douglas et al., Citation2022), and hence its social license to operate.

Replacing traditional practices within the horse industry requires human behavior change. Typically, scientists follow a knowledge-deficit approach to facilitating change (Trench, Citation2008). This approach is built on the belief that new information shapes a person’s perception, beliefs, and attitudes, which in turn lead to behavior change (Abunyewah et al., Citation2020; Simis et al., Citation2016). However, despite wide availability online and in books, the uptake of evidence-based horse-keeping and training practices in the last half-century has been slow (McLean, Citation2013; van Weeren, Citation2008), indicating change of this scale requires more than the provision of information. Understanding the motivations underlying equestrians’ horse-keeping and training practices could augment existing knowledge-based initiatives and potentially accelerate change (Bandura, Citation2004).

While better understanding equestrians’ motivations could inform initiatives to improve horse welfare, more research in this area is needed (Lemon et al., Citation2020). Elite equestrians, usually defined as riders who have represented their country internationally (Hogg & Hodgins, Citation2021; Lamperd et al., Citation2016), are primarily motivated by success and goal achievement and to a lesser extent, having fun and their relationship with horses (Lamperd et al., Citation2016; Webb, Citation2021). Similar results have been reported for amateur equestrians (Mitchell, Citation2013); however, motivations of leisure riders (riders not participating in sport) appear slightly different, with Wu et al. (Citation2015) finding older riders are motivated by escape from everyday routine and crowded areas and younger riders are motivated by learning, relaxation, and social opportunities. Few studies have examined how riders’ motivations, such as desiring a strong horse–human bond or competition success, might influence their practice. However, Webb (Citation2021) found goal achievement shaped elite amateur endurance riders’ practices, but this was constrained to some extent by another motivator, that of not harming their horse. This meant despite these riders being motivated to win, in competition they chose to ride slowly to avoid harming their horses (Webb, Citation2021). Beyond these studies, insights into equestrians’ motivations can also be gained from the wider literature. For example, the well-established self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation2012) of motivation provides the theoretical grounding for successful behavioral change interventions in areas such as exercise and smoking cessation (see Ntoumanis et al., Citation2021 for a meta-analysis of self-determination theory-based health interventions). As such, this theory will provide the theoretical basis for this study. The remainder of this review is framed around the three psychological needs proposed by the theory: competence, autonomy, and relatedness.

In the twenty-first century, elite equestrian sport is primarily a commercial enterprise (Dashper, Citation2014). Riders at the elite level (Hogg & Hodgins, Citation2021) and ambitious young riders (Broms et al., Citation2020) are under pressure to achieve rapid success with their horses to maintain and/or develop their equestrian career. Over two decades ago, Ödberg and Bouissou (Citation1999) suggested modern equestrian competition, and its need for quick results had led to increasing use of coercive horse-training practices. Examples include riding horses with side reins or draw reins while simultaneously using strong driving aids using the leg and spur, with such practices becoming the norm (Ödberg & Bouissou, Citation1999). This is exemplified by the tendency for advanced riders to use harsher equipment (Merkies et al., Citation2022) and the increasing probability that in elite competition a medal-winning dressage horse was ridden with their nose behind the vertical (Lashley et al., Citation2014). The hyperflexed posture is often achieved through simultaneous use of strong rein and leg aids (Condon et al., Citation2021), contrary to evidence-based training principles (McLean & McGreevy, Citation2010b). Coercive practices diminish the human–animal bond (Haverbeke et al., Citation2008), and their increasing use highlights equestrians’ prioritization of goal achievement and control over the other psychological need proposed by self-determination theory: partnership.

In addition to goal achievement, equestrians are motivated by their need to obtain control of the horse (autonomy). Control is often cited as justification for equestrians’ use of certain training methods (van Weeren, Citation2013) and equipment (Condon et al., Citation2021). For example, hyperflexion (riding a horse with their neck flexed so that the horse’s nose almost touches their chest) is postulated to offer the rider “more control … than in any other head and neck position” (Zebisch et al., Citation2014, p. 901). However, the hyperflexed posture compromises the horse’s ability to see (McGreevy et al., Citation2010) and breathe (Mellor & Beausoleil, Citation2017). Furthermore, hyperflexion is usually achieved through strong rein pressure (pain) (Borstel et al., Citation2009). It is suggested hyperflexion “is the cause of much suffering of horses” (van Weeren, Citation2013, p. 291), yet because of equestrians’ need for control, it is routinely practiced (Taylor, Citation2023, p. 76). Also noteworthy, horse “submission” is a core element of dressage (Fédération Equestre Internationale, Citation2022a, p. 9), so it is likely dressage riders are also motivated by competence (goal achievement) to use techniques such as hyperflexion as they strive to produce a competitive (submissive) horse.

In contrast to the utilitarian demands of equestrian sport, such as rapid success, is equestrians’ ideal of building a “deep relationship” with their horse (Birke, Citation2008, p. 115). The language used to describe the horse–human relationship usually reflects this ideal, often referring to the relationship as a “partnership” (Equestrian New South Wales, Citation2023; Fédération Equestre Internationale, Citation2016). In eventing (the three-phase sport including dressage, show jumping, and cross country), riders often use terms such as partnership and refer to human constructs such as respect and trust and deem them crucial to success (Wipper, Citation2000). However, as noted by Wipper, partnerships can be authoritarian, where the horse must be obedient and submit to the rider’s will, or egalitarian, where the rider sees the horse more as an equal and strives to give them more agency during their interactions. This approach to training is seen commonly in zoos during husbandry and veterinary procedures, where the animal is trained so they control the actions of the handler (Wess et al., Citation2022). Typically, narratives infer horse–human partnerships are (to some extent at least) egalitarian (Fédération Equestre Internationale, Citation2016), although in practice, many equestrians demand horses instantly and willingly obey every single rider request (Wipper, Citation2000). While some amateur equestrians strive toward egalitarian partnerships (Dashper, Citation2017), among elite equestrians, some view partnership as antithetical to success (Hogg & Hodgins, Citation2021). With caution, insight into the nature of equestrians’ horse–human partnerships can be drawn from how they interact with their horses. Electing to use a harsh bit (that can apply painful deceleration cues) plus spurs (that can apply painful acceleration cues) (McLean & McGreevy, Citation2010b) might signal the rider has a more authoritarian view of partnership because such equipment gives the horse little choice but to comply with the rider’s aids. Whereas riding bit-free and without spurs may signal a more egalitarian view. Riders seeking an egalitarian partnership may allow horses greater scope to exercise agency. As such, these riders may be unwilling to use pain to achieve coercive control, which is reflected in their choice of equipment. Riders with this mindset achieve safe and enjoyable riding through clear signaling that produces reliable responses from the horse. However, riders using less equipment or less harsh equipment may have initially used harsh training practices or equipment to achieve initial control of the horse, so caution is needed in interpreting practices in this way.

Studies investigating the motivations underlying equestrians’ horse-keeping and training practices are lacking. To gain insight into this issue, we sought to answer the following research questions: (1) Can the psychological needs of competence, autonomy, and relatedness of self-determination theory explain horse care and training practices that affect horse welfare? and (2) What do equestrians prioritize when selecting horse-keeping and training practices?

Theoretical Framework

We draw on systems thinking and self-determination theory to form the conceptual framework for examining motivation among amateur equestrians. A brief outline of both theoretical approaches follows.

Systems Thinking

Presently, most research is based on the scientific method, which relies on a mechanistic view of the world; however, this study was underpinned by a holistic approach known as systems thinking (Capra & Luisi, Citation2014). Arising in the first half of the twentieth century from biology, systems thinking assumes that systems are dynamic and irreducible, thinking is non-linear, and processes rather than objects are the subject of study (Capra & Luisi, Citation2014). System mapping is a cardinal principle of systems thinking, a process permitting multiple perspectives to be appreciated. Where multiple perspectives are studied, multiple conceptual frameworks, and/or epistemologies are generally needed (Bawden, Citation1991; Houghton, Citation2009). Underpinned by interdisciplinarity, the systems thinking approach recognizes that while epistemologies may be unrelated or even contradictory, they are united by their relationship to the problem being studied. Using multiple epistemologies in this way is known as “systemic epistemology” (Bateson, Citation1987; Bawden, Citation1991; Houghton, Citation2009). Appreciating multiple perspectives and using various epistemologies are most likely how systems thinking can deliver rich understanding and novel solutions to complex problems, such as the challenge of improving horse welfare in equestrian sport.

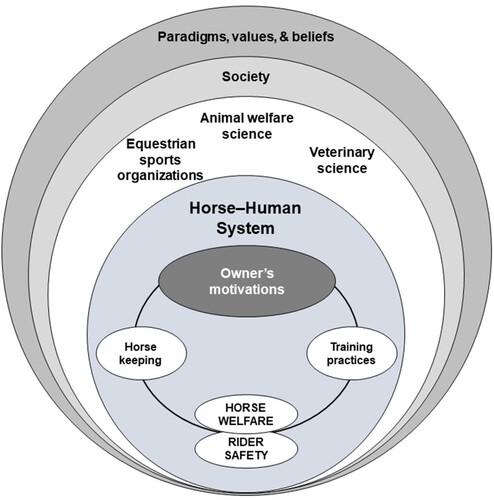

The problems of horse welfare and rider safety have been examined from various perspectives, including riders’ understanding of horse training (Brown & Connor, Citation2017; Luke, McAdie et al., Citation2023; Warren-Smith & McGreevy, Citation2008), horse-keeping practices (Hanis et al., Citation2020; Hockenhull & Creighton, Citation2013; Visser & Van Wijk-Jansen, Citation2012), riding equipment (Condon et al., Citation2021; Cook & Kibler, Citation2019; McGreevy et al., Citation2012), and training practices (Borstel et al., Citation2009; Fenner et al., Citation2019). Most of this research examines these issues from the perspective of the individual. However, illustrates how individual horse–human systems act within larger systems, such as equestrian organizations and society, which in turn are influenced by often unarticulated assumptions and beliefs (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979; Wright & Meadows, Citation2009). There is growing recognition that strategies focusing on individuals tend to deliver, at best, limited, short-term change, which ultimately serves to maintain the status quo (Delon, Citation2018; Shove, Citation2010). While this study investigated the level of individual horse owners and their horses, the adoption of an overarching wide-angle view provided by systems thinking is well placed to take advantage of the findings at the individual level to leverage the system to improve horse welfare.

Figure 1. Adapted from Luke, Rawluk et al. (Citation2023). Equestrians’ motivations are situated within the individual horse–human system, and within larger systems, including equestrian sports organizations such as the Fédération Equestre Internationale and society. Systems mapping can facilitate new perspectives and offer insights into potential system leverage points that may promote change.

Self-Determination Theory

While systems thinking provided the high-level theoretical framework for this study, self-determination theory was used to interrogate and explain the data in detail. Self-determination theory was selected based on several factors. Human behavior change as a strategy to improve animal welfare is relatively undeveloped compared with areas such as human health (Glanville et al., Citation2020). Embedding self-determination theory within a systems thinking framework offers the scope to overcome the limitations of traditional individualistic psychological approaches, which tend to maintain the status quo, while also navigating the data using a conceptually familiar and well-established theory in the human behavior change field (Ntoumanis et al., Citation2021; Teixeira et al., Citation2020). Moreover, gaining greater insight into the motivations underlying individual equestrian’s practices will be valuable to inform future efforts focused on human behavior, whether at the individual, community, or societal level.

Self-determination theory is a well-established approach to understanding intrinsic human motivation, social development, and wellbeing (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000, Citation2019), and is widely used in sport research (Vasconcellos et al., Citation2020; Wilson et al., Citation2008). Central to self-determination theory is the assumption that humans are “inherently active, intrinsically motivated, and oriented toward developing naturally through integrative processes” (Deci & Ryan, Citation2012, p. 417). The theory highlights that environmental factors, including inter-personal relationships, can foster or hinder motivation and wellbeing. Moreover, the theory states that for a person to experience positive wellbeing, humans’ biological and psychological needs must be met. The three fundamental psychological needs proposed include competence (the need to experience being effective in producing behavioral outcomes), autonomy (the need to feel in control of, and take responsibility for, one’s actions), and relatedness (the need to experience connection to and a sense of reciprocal concern for others) (Deci & Ryan, Citation2012). For example, in the clinical physical-health setting, these psychological needs have been translated such as competence relates to patients’ need to understand how they can attain health-related goals and to feel that they can be effective in carrying out the necessary actions; autonomy relates to patients’ need to feel a sense of choice and volition in achieving their health-related goals; and relatedness relates to patients’ need to be respected and cared for by healthcare practitioners and important others (Sheldon et al., Citation2008).

Self-determination theory was recently applied to ridden horse–human interactions. In the study, Luke et al. (Citation2023b) extended self-determination theory beyond its traditional use of informing human–human interactions to inform horse–human interactions. The self-determination theory concept of competency was understood as the equestrian’s need to feel knowledgeable and skillful in how they cared for and trained their horse, a measure of which was goal achievement. Autonomy was seen as the equestrian’s need to feel in control of their horse; for example, choosing what and how they accomplished their riding activities. Relatedness was understood as the equestrian’s need to feel a connection, or sense of partnership, with their horse. This model accounted for 63% of the variance in rider satisfaction scores in a sample (n = 427) of non-elite equestrians (Luke et al., Citation2023b). Importantly, of the three psychological needs, it was relatedness (horse–rider partnership) that was the greatest contributor to rider satisfaction, suggesting that although riders may be primarily motivated by competence (goal achievement), it is relatedness (horse–rider partnership) that is most satisfying.

The extended understanding of the self-determination theory concepts of competency, autonomy, and relatedness were used in this study.

Methods

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval for this project was received from Central Queensland University human ethics committee, approval number 0000023272.

Data Collection and Analysis

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author (KL) throughout 2022. Interviews took place at the participant’s home or horse agistment (boarding) facility and were audio-recorded. Interview audio was uploaded into NVivo software, version 1.6.1 (QSR International, Citation2022), which was used to transcribe and analyze the qualitative data.

Interviews comprised three sections. Participants were first invited to discuss everything about their journey with their horse, or for owners of multiple horses, the horse they selected as the subject for the interview. The interviewer did not guide participants about the timeframe or what information was required; however, most participants started from when they purchased their horse and continued to the present. If participants needed prompting, they were asked to share how they cared for and trained their horse. Second, they were asked about their choice of riding equipment, the challenges of owning and riding horses, and their opinion on ridden-horse welfare. Third, participants were asked to respond to four hypothetical vignettes depicting scenarios such as the appropriate age to begin foundation training, how to manage a tense or unresponsive horse while riding, and how to respond to a horse that is difficult to catch (see online supplemental information).

Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-phase process of thematic analysis was followed to analyze the data. Thematic analysis can take several forms (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). This study adopted a recursive, reflexive approach informed by social constructionism (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013), and data were examined from a critical realist perspective (Moon & Blackman, Citation2014). To become familiar with the data, the transcribed interviews were read twice. Each transcript was then inductively (i.e., no theoretical framework is used to code the data) and reflexively (where the researcher is critically self-aware of their role in the process) coded in relation to the research questions (see Braun & Clarke, Citation2019 for detailed discussion of this approach). The data and codes were then examined once more, this time using the psychological needs proposed by self-determination theory (competence, autonomy, and relatedness) as a guide. This process was iterative and non-linear (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). Codes were reviewed and where appropriate, grouped to form major codes. From the identification of major codes, themes were developed and refined. In response to the research questions, four themes were identified.

Participant Recruitment and Response

Amateur sport-horse riders in Victoria, Australia were targeted via social media (Facebook) using non-paid advertisements (posts) in various interest groups. Interest groups included those focused on dressage, eventing, showing, show jumping, and reining, and organizations such as the Horse Riding Clubs Association of Victoria (HRCAV) were contacted (Gasteiger et al., Citation2021; Pickering & Hockenhull, Citation2019). Participants completed a screening survey to ensure they met inclusion criteria, which were: resided in Victoria, Australia; owned or cared for at least one horse; and rode their horse at least once a week. Participants fulfilling the inclusion criteria were contacted to arrange an interview time. All participants volunteered and provided informed consent electronically at the time of the screening survey and verbally at the beginning of the interview. Interview data were anonymized; participants were assigned an identifier (P1 to P19). All place names are fictional, and horses’ names were changed.

Participant Demographics

The sample covered a broad range of ages, from 19 to 70 years, and included horse owners from metropolitan, semi-rural, and rural Victoria. Amateur equestrian sport is female-dominated (Dashper, Citation2012); this was reflected in the sample, with 17 female participants and 2 male participants. Many participants engaged in dressage (n = 10); however, some participants’ focus was eventing (n = 4), show jumping (n = 2), showing (n = 1), or trail riding (n = 2).

Results and Discussion

Achieving Equestrian Goals is the Primary Motivator

Many participants shared stories of their journey with horses, highlighting their passion and determination to own a horse.

At age ten I'd save up for four weeks and … go to Countryside Riding school and ride for an hour … when I was 14 … [my parents] got the cheapest horse I could find … from Sunnybrook market. This horse had been abused … he was terrified of everything … dangerously terrified, but that's what they could afford, so that's what I got. (P1, female, advanced-level dressage rider)

Enmeshed in this passion was frequently an acknowledgement that when they purchased their first horse, participants had a limited understanding of horses’ needs and limited knowledge and skill in horse training.

I didn't have horses growing up because we lived in the suburbs, didn't have any money. So, I spent a lot of time looking at them on the internet, trying to read about training. I got on to … the site [of a professional horse trainer] … I bought a horse and started using their techniques. (P18, female, intermediate-level dressage rider)

Participants often acknowledged their past or present limitations in knowledge and skill: “Sometimes I just don’t know what I’m doing [when it comes to training]” (P16) and “I don’t feel I have the experience to … make decisions about that stuff [selecting appropriate equipment and training methods], so I tend to outsource it” (P9). Yet, despite this shortfall in knowledge and skill, achieving competitive success was a high priority for most participants, with several striving to ride at an elite level:

It's my ambition … to ride at FEI level [international level competition]. Mainly because I've got three girlfriends … and they've all won at Prix St George. (P1, female, advanced dressage rider)

Prioritizing competitive success by participants supports the findings of Broms et al. (Citation2020) and demonstrates amateur equestrians’ priorities are not dissimilar to those of elite equestrians (Dashper, Citation2014; Hogg & Hodgins, Citation2021). Similarly, a study involving the Canadian Pony Club showed traditional values of horsemanship knowledge and friendship were increasingly replaced with discipline-specific competitive success (Gilbert, Citation2017). Neoliberal economic logic was suggested as one explanation for this shift (Gilbert, Citation2017), where neoliberalism is characterized by individualism and proposes all human activities commodified (Harvey, Citation2007). Given the ubiquity of neoliberalism (Harvey, Citation2007; Sims, Citation2020), it is likely Australian equestrian sport mirrors Canadian equestrian sport in this respect. Identifying how an individual’s psychological needs, such as competence, can be shaped by the values embodied in higher-order systems in which an equestrian is immersed, such as neoliberalism, offers insights into the scope and type of challenges that must be overcome when developing successful strategies to improve horse welfare in equestrian sport.

Equestrians Work Hard to Develop Their Equestrian Knowledge and Skills

Many participants shared examples of ridden-horse behavior they felt unable to manage, and the high rate of injuries, including life-threatening injuries and fatalities, among Australian equestrians (Kreisfeld & Harrison, Citation2020; National Coronial Information System, Citation2020; O'Connor et al., Citation2018) suggests that many equestrians are indeed ill-equipped to safely manage some horse behavior. Participants often acknowledged their lack of knowledge and skill, but they also indicated they were highly motivated to learn. One participant explained it this way:

I don't think I'd ever get to the point where I've learned everything about horses … I think to the day I take my last breath, there'll be … stuff I don't know … that I'd like to know. (P2, female, intermediate dressage rider)

Participants’ high rate of employing coaches emphasizes that they recognize their knowledge and skills insufficiencies and their motivation to improve. One participant revealed equestrians often had unquestioned reliance on their coach’s advice:

… you have to trust that person because they're pushing you outside your comfort zone … in a dangerous situation, so you have to trust them completely. And so, when they say do this, you do it. You don't question it. (P9, male, beginner eventing rider)

In participants’ quest to become more competent, their prioritization of goal achievement was further reflected in their coach selection strategies. When quizzed about selecting a coach, most participants’ immediate response was reciting their coach’s level of competitive achievement: “We work with a 4* eventer coach … and she's great” (P13, female, intermediate event/show-jumping rider). Another participant responded: “She's trained and competed to Grand Prix dressage” (P18, female, intermediate dressage rider). A third participant described how he saw his coach regularly competing and growing her business and took these as signs of a high-quality coach.

She's [the coach] always up at Cookson [elite competition venue] competing … seeing these results and seeing her train horses from … foals right through to Grand Prix level, knowing … she has that experience in working with horses from a young age and working with different horses … it's a fairly sizable operation and it keeps getting bigger. (P9, male, beginner event rider)

Although coaching credentials were not a consideration in coach selection, training efficiency and efficacy were viewed favorably and seen as another indicator of high-quality coaching. One participant had admiration for techniques that “just work”: “I … started using their techniques … and it worked … as long as you followed the instructions, it worked” (P18, female, intermediate dressage rider). The notion of efficiency was captured when a participant explained why she liked her coach: “What she taught, you could see the results … very quickly and easily” (P17, female, intermediate dressage rider). These quotes illustrate that not only are equestrians highly motivated to become more competent and skillful, but they also want to learn horse-training techniques that deliver results quickly. This was confirmed when participants were asked about their greatest challenge as horse owners. The response to this question was, almost universally, time. For example: “I think the biggest challenge … is finding the time” (P2, female, intermediate dressage rider). Lack of time and desire for competitive success result in amateur equestrians needing efficient and effective training techniques. These pressures are the same, or similar to, those of elite equestrians and ambitious young equestrians (Broms et al., Citation2020; Dashper, Citation2014; Hogg & Hodgins, Citation2021). Moreover, it is likely that coaches and aspiring coaches understand establishing and growing a successful coaching business is dependent upon attracting (demonstrated competitive success) and retaining customers (efficient and effective training methods). With goal-focused, time-poor equestrians and commercially aware coaches, it is possible to see how a system is created where training that prioritizes competitive success, efficiency (quick results), and efficacy (desired results) rewards both coaches and riders. Therefore, while prioritizing horse welfare may be coaches’ and riders’ ideal, it is likely in practice, the factors identified in this and previous studies, such as quick results, take precedence and shape equestrians’ choice of horse care and training practices.

Equestrians are Highly Motivated to Compete and/or Participate in Club Activities

Most participants in this study competed regularly and/or were members of an equestrian organization. Many equestrian organizations, such as the HRCAV (Horse Riding Clubs of Victoria, Citation2021) and equestrian sports, such as dressage and eventing (Fédération Equestre Internationale, Citation2022b), require horses to be ridden in a bit. However, there is growing evidence that horses find bits intrinsically aversive (Cook & Kibler, Citation2019; Quick & Warren-Smith, Citation2009), and the way many riders use bits contributes to painful lesions in the horse’s mouth (Tuomola et al., Citation2021; Uldahl & Clayton, Citation2019). Also, a recent study found horses ridden with a bit had lower relative welfare scores (indicating poorer welfare) than horses ridden bit-free (Luke et al., Citation2023a). While the association between riding with bits and impaired horse welfare is still emerging, interest in bit-free riding is growing. With articles appearing in industry press (Crandon, Citation2018; Nafziger-LeVeck, Citation2019) and the emergence of organizations such as the World Bitless Association (https://worldbitlessassociation.org), it is likely most participants would have some knowledge of this potential link. Riders who are aware of and accept this new information and seek to live the ideal of prioritizing horse welfare, are then faced with a dilemma: to uphold their ideal and ride bit-free or comply with the rules of their sport and ride with a bit.

Given the tension between prioritizing horse welfare and the rules of equestrian sport in relation to bits, we asked participants about their decision to ride their horse with or without a bit. Many were incredulous at being asked the question. One participant, when encouraged to explore the issue a little more, burst out good-naturedly: “It’s a hard question! I don't think I've ever been asked that question” (P14, female, advanced-level dressage rider). After thinking out loud, clearly a little shaken at having such a fundamental practice questioned and realizing she had not really given it much thought, she settled on: “I have no idea why I choose to ride with a bit.” Other participants were similarly non-plussed at the question but dismissed it as foolish because there was no decision to be made: competing mandated the use of a bit, so no further consideration was necessary. An advanced-level show rider put it this way: “Because I've just always done it, I suppose” (P7, female). Similarly, a regular dressage and show-jumping competitor responded: “You have to have a bit for proper dressage, so I would never have seriously considered it [riding bit-free]” (P5, female, intermediate-level dressage rider). These quotes highlight tradition and rules render bit use a largely automatic practice that is unquestioned by many equestrians.

In addition to being required to compete, several participants indicated a bit was necessary to engage in club activities, explaining they would not be covered by insurance if they rode without a bit.

I usually use a bit because it's required for riding club … but it’s a very soft snaffle because my hands aren't the greatest, and I'll be the first to admit that … She [the horse] would probably … much prefer … a hackamore or a bosal but unfortunately, the type of riding I do, the association requires a bit for insurance. So, if I'm riding without a bit, I'm not insured. (P2, female, intermediate dressage rider)

While the previous examples highlight that complying with the rules of their sport or club was behind their decision to ride with a bit, controlling the horse was another reason raised by several participants. Generally, when participants raised the issue of control, it was usually a secondary consideration, after they had discussed the requirement of a bit to compete.

I've always ridden with a bit … and I guess it's insurance. While I'm quite confident in Felix now, if he was out on the road and something frightened him, I don't know what he’d do. So, it's a control mechanism, basically. (P1, female, advanced dressage rider)

I broke my bridle once in the middle of a trail ride because she stood on the split rein and the bridle went snap. So, I just rode for the next two hours in the halter. (P2, female, intermediate dressage rider)

Recognizing equestrians are highly motivated to participate and compete in organized activities and sport highlights the challenges and opportunities for creating change to improve horse welfare. For example, changing the rules of equestrian sport to protect horse welfare could disrupt the status quo leading to the development of new norms within the industry. Updated rules alone may be insufficient to produce widespread change; however, as part of an integrated strategy, it is likely significant change could be achieved. If well executed, equestrians’ strong motivation to participate and compete would facilitate compliance with the new rules and in time change their practice. There is some support for this contention in the literature. A study examining noseband tightening practices in dressage, show jumping and performance hunters in the UK and Ireland found 44% of riders had their noseband fastened so that no fingers could be placed between the noseband and the horse’s nasal planum (Doherty et al., Citation2017). A Dutch study, with a similar population, but where the noseband rule had been changed to stipulate they must be fastened such that two fingers can be inserted between the noseband and the nasal planum, found only 4% of competitors had their noseband fastened such that no fingers could be inserted (Visser et al., Citation2019). While comparing studies in this way is not the gold standard of scientific evidence, the change in equestrians’ noseband tightening practice between the two studies is striking. A longitudinal study examining equestrians’ practices before and after a rule change such as this would be valuable.

Achieving a Financial Return on a Horse is Important to Many Equestrians

In the same way, all equestrians must choose to ride their horse with or without a bit, they must also decide at what age to begin riding their horse. Initial training is traditionally referred to as “breaking” the horse but is increasingly referred to as foundation training or starting (Quick & Warren-Smith, Citation2009); hereafter, foundation training is used. While foundation training is usually undertaken by a specialist trainer, equestrians must nevertheless decide at what age to commence training. When presented with a scenario describing the owner of a two-year-old horse deciding if she should send her horse to the trainer or wait for a year, most participants firmly stated a two-year-old horse was too young to be ridden. Participants described how the horse was too immature physically, psychologically, or both: “I don't like breaking them in until they're at least four or five, because nothing is set, their bones aren't set, their knees haven't come together” (P6, female, advanced dressage rider and judge). However, immediately following their insight into the negative welfare implications of riding an immature horse, many participants stated most equestrians would send their horse for foundation training as a two-year-old.

If he's just going to break it to saddle and turn it out for 12 months and … it's … gentle, and it's just learning … turning and stopping and … familiarization of having someone on their back, but it's not hard work. Yeah, probably okay. But they're not ready, they're not. Nothing's set. (P6, female, advanced dressage rider and judge)

And more dressage-y ones, they want them to be a certain level so they can sell them for 40 grand [$40,000] when they're three and a half years old … so maybe they start them at two and a half years old. (P3, female, intermediate dressage rider and riding club official)

I'm still working through whether he's actually the horse for me … just because I like him … these days I'm sort of beyond just [keeping him] because I love him. (P16, female, intermediate trail rider)

So far, the themes discussed have focused heavily on self-determination theory’s psychological need of competence (equestrian goal achievement) and to a lesser extent autonomy (control of the horse). This is largely because participants generally focused on goal achievement, occasionally discussed control, and almost never discussed partnership. Participants were invited to share anything they felt was relevant to their journey with their horse. Despite this open invitation, partnership with their horse rarely arose. Participants spoke freely about frustrations with their lack of progress and their aspirations to achieve, at times quite ambitious, equestrian goals. However, rarely did they discuss their affection for their horse or acknowledge the generosity of their horse in performing for them so they could achieve their goals. At no time did a participant explain that they chose a particular practice as a way of enhancing their partnership with their horse, or the reverse, that they were concerned about practice because it might adversely affect their partnership with their horse. This omission may be an artifact of the interview process, or, and we believe this more likely, it may accurately reflect equestrians’ priorities in their horse–human interactions.

The findings of this study offer important insights into the motivations underlying equestrians’ horse-keeping and training practices; however, it has limitations. Follow-up research with samples from other geographical regions, as well as studies investigating specific disciplines, may reveal nuances among equestrians we could not identify. Self-determination theory has informed several sport-motivation studies (Vasconcellos et al., Citation2020; Webb, Citation2021; Wilson et al., Citation2008) and successful human behavior change strategies (Gauthier et al., Citation2022; Ntoumanis et al., Citation2021); hence, its use in this study. However, other theories may be more useful. Psychologists are beginning to recognize that change strategies at the individual level may unwittingly distract necessary efforts to drive change at the systemic level (Chater & Loewenstein, Citation2022), a sentiment with which we agree. Chater and Loewenstein (Citation2022) argue corporations spend billions of dollars on individual-based solutions to issues such as climate change because they recognize they will produce modest change at best and therefore pose little threat to their business. Strategically maintaining focus on individual-based solutions limits the scope for systemic change, which might indeed disrupt business operations. One example of a systemic approach to change in horse training is Cousquer (Citation2023), who engaged in an experiential awareness-based Action Research approach to transforming the human–equine relationship in mountain tourism. This research was based on, among other things, Eisler and Fry’s biocultural partnership–domination lens (Citation2019), which offers a potentially more sustainable alternative to Western society’s favored domination-based approach. This approach allowed muleteers to shift from seeing the mule as an object to seeing the mule as an extension of themselves. The change in mindset transformed the way mules were trained and cared for, and their welfare was improved (Cousquer, Citation2023). Similar analyses of data from this study might be further illuminating.

Conclusion

Self-determination theory proposes humans are intrinsically motivated by three psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness. In this study, we found equestrians do not prioritize these three needs equally when selecting their horse-keeping and training practices. We found competence, defined as goal achievement, drove most practice decisions. Moreover, when the needs of autonomy (control) and relatedness (partnership) were engaged, they were generally to enable goal achievement. In a finding consistent with previous research, we identified a tension between satisfying human needs and horse needs (Dashper, Citation2014; Hogg & Hodgins, Citation2021; McLean & McGreevy, Citation2010a). Moreover, this tension was generally resolved in favor of human needs rather than horse needs – a bias that exists for most human–animal interactions in Western society (Carter & Charles, Citation2013). Studies such as this emphasize the motivations and challenges equestrians face in selecting their practices and how they currently resolve those challenges. This new information can help to develop strategies so human and horse needs can be more equitably balanced. Furthermore, this research emphasizes the strong motivation of equestrians to participate in equestrian sport and their capacity to adopt practices to enable their participation. This emphasizes the important role equestrian sports organizations such as the Fédération Equestre Internationale can play in improving horse welfare through the rules of their sport. Reforming equestrian sport so that horse welfare is protected may help assure the industry’s long-term future, but it requires the involvement of all stakeholders. Greater insight into the motivational priorities of equestrians’ horse-keeping and training practices identified in this study can help inform the multifaceted reform agenda needed to solve the complex challenge of improving sport-horse welfare.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (55.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their insights and suggestions that have improved this paper. We also thank the equestrians who volunteered their time and made this research possible.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abunyewah, M., Gajendran, T., Maund, K., & Okyere, S. A. (2020). Strengthening the information deficit model for disaster preparedness: Mediating and moderating effects of community participation. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 46, 101492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101492

- Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660

- Bateson, G. (1987). Steps to an ecology of mind. Jason Aronson.

- Bawden, R. J. (1991). Systems thinking and practice in agriculture. Journal of Dairy Science, 74(7), 2362–2373. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78410-5

- Birke, L. (2008). Talking about horses: Control and freedom in the world of “natural horsemanship”. Society & Animals, 16(2), 107–126. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853008X291417

- Borstel, U., Duncan, I. J. H., Shoveller, A., Merkies, K., Keeling, L. J., & Millman, S. (2009). Impact of riding in a coercively obtained Rollkur posture on welfare and fear of performance horses. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 116(2–4), 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2008.10.001

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Broms, L., Hedenborg, S., & Radmann, A. (2020). Super equestrians – The construction of identity/ies and impression management among young equestrians in upper secondary school settings on social media. Sport, Education and Society, 27(4), 462–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1859472

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

- Brown, S. M., & Connor, M. (2017). Understanding and application of learning theory in UK-based equestrians. Anthrozoös, 30(4), 565–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2017.1370216

- Capra, F., & Luisi, P. L. (2014). The systems view of life: A unifying vision. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511895555

- Carroll, H. K., Bott-Knutson, R. C., & Mastellar, S. L. (2018). Equine caregiver information-seeking preferences: Surveys in the Midwest. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 64, 65–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2018.02.006

- Carter, B., & Charles, N. (2013). Animals, agency and resistance. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 43(3), 322–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12019

- Chater, N., & Loewenstein, G. (2022). The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 47, e147. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X22002023

- Condon, V. M., McGreevy, P. D., McLean, A. N., Williams, J. M., & Randle, H. (2021). Associations between commonly used apparatus and conflict behaviours reported in the ridden horse in Australia. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 49, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2021.10.014

- Cook, W. R. (1999) Pathophysiology of bit control in the horse. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 19(3), 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0737-0806(99)80067-7

- Cook, W. R., & Kibler, M. (2019). Behavioural assessment of pain in 66 horses, with and without a bit. Equine Veterinary Education, 31(10), 551–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.12916

- Cousquer, G. (2023). From domination to dialogue and the ethics of the between: Transforming human–working equine relationships in mountain tourism. Austral Journal of Veterinary Sciences, 55(1), 35–60. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0719-81322023000100035

- Crandon, J. (2018). Bitless bridles: What, why and how. Horse & Hound. https://www.horseandhound.co.uk/features/bitless-bridle-673466

- Dashper, K. (2012). Together, yet still not equal? Sex integration in equestrian sport. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 3(3), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2012.721727

- Dashper, K. (2014). Tools of the trade or part of the family? Horses in competitive equestrian sport. Society & Animals, 22(4), 352–371. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-12341343

- Dashper, K. (2017). Listening to horses. Society & Animals, 25(3), 207–224. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-12341426

- Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2012). Self-determination theory. In P. A. M. V. Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 416–437). SAGE.

- Delon, N. (2018). Social norms and farm animal protection. Palgrave Communications, 4(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0194-5

- Doherty, O., Casey, V., McGreevy, P., & Arkins, S. (2017). Noseband use in equestrian sports – An international study. PLoS ONE, 12(1), e0169060. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169060

- Douglas, J., Owers, R., & Campbell, M. (2022). Social licence to operate: What can equestrian sports learn from other industries? Animals, 12(15), 1987. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12151987

- Eisler, R., & Fry, D. (2019). Nurturing our humanity. Oxford University Press.

- Equestrian New South Wales. (2023). What is jumping. https://www.nsw.equestrian.org.au/jumping

- Evans, D., & McGreevy, P. (2011). An investigation of racing performance and whip use by jockeys in thoroughbred races. PLoS ONE, 6(1), 15622. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0015622

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. (2016). Olympic equestrian #TwoHearts campaign captures hearts around the world. Fédération Equestre Internationale. https://inside.fei.org/media-updates/olympic-equestrian-twohearts-campaign-captures-hearts-around-world

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. (2022a). Dressage rules. Fédération Equestre Internationale. https://inside.fei.org/fei/disc/dressage/rules

- Fédération Equestre Internationale. (2022b). Eventing rules. Fédération Equestre Internationale. https://inside.fei.org/content/fei-eventing-rules-2022

- Fenner, K., McLean, A. N., & McGreevy, P. D. (2019). Cutting to the chase: How round-pen, lunging, and high-speed liberty work may compromise horse welfare. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 29, 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2018.05.003

- Fletcher, T., & Dashper, K. (2013). “Bring on the dancing horses!”: Ambivalence and class obsession within British media reports of the dressage at London 2012. Sociological Research Online, 18(2), 118–125. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3040

- Gasteiger, N., Vedhara, K., Massey, A., Jia, R., Ayling, K., Chalder, T., Coupland, C., & Broadbent, E. (2021). Depression, anxiety and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a New Zealand cohort study on mental well-being. BMJ Open, 11(5), e045325. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045325

- Gauthier, A. J., Guertin, C., & Pelletier, L. G. (2022). Motivated to eat green or your greens? Comparing the role of motivation towards the environment and for eating regulation on ecological eating behaviours – A self-determination theory perspective. Food Quality and Preference, 99, 104570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2022.104570

- Gilbert, M. (2017). Sociocultural changes in Canadian equestrian sport. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55886-8_10

- Glanville, C., Abraham, C., & Coleman, G. (2020). Human behaviour change interventions in animal care and interactive settings: A review and framework for design and evaluation. Animals, 10(12), 2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10122333

- Hanis, F., Chung, E. L. T., Kamalludin, M. H., & Idrus, Z. (2020). The influence of stable management and feeding practices on the abnormal behaviors among stabled horses in Malaysia. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 94, 103230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2020.103230

- Harvey, D. (2007). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

- Haverbeke, A., Laporte, B., Depiereux, E., Giffroy, J. M., & Diederich, C. (2008). Training methods of military dog handlers and their effects on the team's performances. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 113(1), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2007.11.010

- Heleski, C. (2023). Social license to operate – Why public perception matters for horse sport – Some personal reflections. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 124, 104266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2023.104266

- Hockenhull, J., & Creighton, E. (2013). The use of equipment and training practices and the prevalence of owner-reported ridden behaviour problems in UK leisure horses. Equine Veterinary Journal, 45(1), 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2012.00567.x

- Hogg, R. C., & Hodgins, G. A. (2021). Symbiosis or sporting tool? Competition and the horse–rider relationship in elite equestrian sports. Animals, 11(5), 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11051352

- Horse Riding Clubs of Victoria. (2021). Dressage rules. https://hrcav.com.au/rules-guidelines/hrcav-manual/.

- Houghton, L. (2009). Generalization and systemic epistemology: Why should it make sense? Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 26(1), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.929

- Jijelava, D., & Vanclay, F. (2017). Legitimacy, credibility and trust as the key components of a social licence to operate: An analysis of BP's projects in Georgia. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, 1077–1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.10.070

- Kreisfeld, R., & Harrison, J. E. (2020). Hospitalised sports injury in Australia, 2016–17. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, INJCAT, 131, 1–20.

- Lamperd, W., Clarke, D., Wolframm, I., & Williams, J. (2016). What makes an elite equestrian rider? Comparative Exercise Physiology, 12(3), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.3920/CEP160011

- Lashley, M. J. J. O., Nauwelaerts, S., Vernooij, J. C. M., Back, W., & Clayton, H. M. (2014). Comparison of the head and neck position of elite dressage horses during top-level competitions in 1992 versus 2008. The Veterinary Journal, 202(3), 462–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.08.028

- Lemon, C., Lewis, V., Dumbell, L., & Brown, H. (2020). An investigation into equestrian spur use in the United Kingdom. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 36, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2019.10.009

- Lesimple, C., Poissonnet, A., & Hausberger, M. (2016). How to keep your horse safe? An epidemiological study about management practices. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 181(C), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2016.04.015

- Lofgren, E. A., Voigt, M. A., & Brady, C. M. (2016). Information-seeking behavior of the horse competition industry: A demographic study. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 37, 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2015.10.005

- Luke, K., McAdie, T., Warren-Smith, A., Rawluk, A., & Smith, B. P. (2023). Does a working knowledge of learning theory relate to improved horse welfare and rider safety? Anthrozoös, 36(4), 703–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2023.2166713

- Luke, K., McAdie, T., Warren-Smith, A., & Smith, B. P. (2023a). Bit use and its relevance for rider safety, rider satisfaction and horse welfare in equestrian sport. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 259, 105855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2023.105855

- Luke, K., McAdie, T., Warren-Smith, A., & Smith, B. P. (2023b). Untangling the complex relationships between horse welfare, rider safety, and rider satisfaction. Anthrozoös, 36(4), 721–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2023.2176589

- Luke, K., Rawluk, A., McAdie, T., Smith, B. P., & Warren-Smith, A. (2023). How equestrians conceptualise horse welfare and its role in facilitating or hindering change. Animal Welfare, 32, e59. https://doi.org/10.1017/awf.2023.79

- McGreevy, P., Harman, A., McLean, A., & Hawson, L. (2010). Over-flexing the horse's neck: A modern equestrian obsession? Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 5(4), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2010.03.004

- McGreevy, P., Hawson, L. A., Salvin, H., & McLean, A. (2013). A note on the force of whip impacts delivered by jockeys using forehand and backhand strikes. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 8(5), 395–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2013.03.003

- McGreevy, P., Warren-Smith, A., & Guisard, Y. (2012). The effect of double bridles and jaw-clamping crank nosebands on temperature of eyes and facial skin of horses. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 7(3), 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2011.08.001

- McLean, A. N. (2013). Training the ridden animal: An ancient hall of mirrors. The Veterinary Journal, 196(2), 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.10.031

- McLean, A. N., & McGreevy, P. D. (2010a). Ethical equitation: Capping the price horses pay for human glory. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 5(4), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2010.04.003

- McLean, A. N., & McGreevy, P. D. (2010b). Horse-training techniques that may defy the principles of learning theory and compromise welfare. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 5(4), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2010.04.002

- Mellor, D. J. (2020). Mouth pain in horses: Physiological foundations, behavioural indices, welfare implications, and a suggested solution. Animals, 10(4), 572. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10040572

- Mellor, D. J., & Beausoleil, N. J. (2017). Equine welfare during exercise: An evaluation of breathing, breathlessness and bridles. Animals, 7(6), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7060041

- Merkies, K., Copelin, C., McPhedran, C., & McGreevy, P. (2022). The presence of various tack and equipment in sale horse advertisements in Australia and North America. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 55–56, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2022.07.010

- Mitchell, S. E. (2013). Self-determination theory and Oklahoma equestrians: A motivation study [Doctoral dissertation]. Oklahoma State University.

- Moon, K., & Blackman, D. (2014). A guide to understanding social science research for natural scientists. Conservation Biology, 28(5), 1167–1177. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12326

- Nafziger-LeVeck, L. (2019). The benefits of riding bitless. Equine Wellness Magazine. https://equinewellnessmagazine.com/benefits-riding-bitless/

- National Coronial Information System. (2020). Animal-related deaths in Australia. NCIS Fact Sheet. https://www.ncis.org.au/publications/ncis-fact-sheets/animal-related-deaths-2/

- Ntoumanis, N., Ng, J. Y. Y., Prestwich, A., Quested, E., Hancox, J. E., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Lonsdale, C., & Williams, G. C. (2021). A meta-analysis of self-determination theory-informed intervention studies in the health domain: Effects on motivation, health behavior, physical, and psychological health. Health Psychology Review, 15(2), 214–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2020.1718529

- O'Connor, S., Hitchens, P. L., & Fortington, L. V. (2018). Hospital-treated injuries from horse riding in Victoria, Australia: Time to refocus on injury prevention? BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 4(1), e000321. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2017-000321

- Ödberg, F. O., & Bouissou, M. F. (1999). The development of equestrianism from the baroque period to the present day and its consequences for the welfare of horses. Equine Veterinary Journal, 28(S28), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1999.tb05152.x

- Pickering, P., & Hockenhull, J. (2019). Optimising the efficacy of equine welfare communications: Do equine stakeholders differ in their information-seeking behaviour and communication preferences? Animals, 10(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10010021

- Prno, J., & Slocombe, D. (2012). Exploring the origins of “social license to operate” in the mining sector: Perspectives from governance and sustainability theories. Resources Policy, 37(3), 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.04.002

- QSR International. (2022). NVivo. QSR International.

- Quick, J. S., & Warren-Smith, A. K. (2009). Preliminary investigations of horses’ (Equus caballus) responses to different bridles during foundation training. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 4(4), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2008.12.001

- Ruet, A., Lemarchand, J., Parias, C., Mach, N., Moisan, M.-P., Foury, A., Briant, C., & Lansade, L. (2019). Housing horses in individual boxes is a challenge with regard to welfare. Animals, 9(9), 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9090621

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2019). Brick by brick: The origins, development, and future of self-determination theory. In A. J. Elliott (Ed.), Advances in motivation science (Vol. 6, pp. 111–156). Elsevier.

- Sheldon, K. M., Williams, G., & Joiner, T. (2008). Self-determination theory in the clinic: Motivating physical and mental health. Yale University Press.

- Shove, E. (2010). Beyond the ABC: Climate change policy and theories of social change. Environment and Planning A, 42(6), 1273–1285. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42282

- Simis, M. J., Madden, H., Cacciatore, M. A., & Yeo, S. K. (2016). The lure of rationality: Why does the deficit model persist in science communication? Public Understanding of Science, 25(4), 400–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662516629749

- Sims, M. (2020). Bullshit towers: Neoliberalism and managerialism in universities in Australia. Peter Lang.

- Sykes, B. W., Bowen, M., Habershon-Butcher, J. L., Green, M., & Hallowell, G. D. (2019). Management factors and clinical implications of glandular and squamous gastric disease in horses. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 33(1), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.15350

- Taylor, J. (2023). Hyperflexion: What is it, why it's done and how it's being stopped? Concordia, 7, 29–32. https://concordiaequestrians.org/the-state-of-modern-dressage/

- Teixeira, P. J., Marques, M. M., Silva, M. N., Brunet, J., Duda, J. L., Haerens, L., La Guardia, J., Lindwall, M., Lonsdale, C., Markland, D., Michie, S., Moller, A. C., Ntoumanis, N., Patrick, H., Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., Sebire, S. J., Standage, M., Vansteenkiste, M., … Hagger, M. S. (2020). A classification of motivation and behavior change techniques used in self-determination theory-based interventions in health contexts. Motivation Science, 6(4), 438–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000172

- Trench, B. (2008). Towards an analytical framework of science communication models. In D. Cheng, M. Claessens, T. Gascoigne, J. Metcalfe, B. Schiele, & S. Shi (Eds.), Communicating science in social contexts: New models, new practices (pp. 119–135). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8598-7_7

- Tuomola, K., Mäki-Kihniä, N., Valros, A., Mykkänen, A., & Kujala-Wirth, M. (2021). Bit-related lesions in event horses after a cross-country test. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 290. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.651160

- Uldahl, M., & Clayton, H. M. (2019). Lesions associated with the use of bits, nosebands, spurs and whips in Danish competition horses. Equine Veterinary Journal, 51(2), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/evj.12827

- van Weeren, P. R. (2008). How long will equestrian traditionalism resist science? The Veterinary Journal, 175(3), 289–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.06.017

- van Weeren, P. R. (2013). About Rollkur, or low, deep and round: Why Winston Churchill and Albert Einstein were right. The Veterinary Journal, 196(3), 290–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.04.016

- Vasconcellos, D., Parker, P. D., Hilland, T., Cinelli, R., Owen, K. B., Kapsal, N., Lee, J., Antczak, D., Ntoumanis, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2020). Self-determination theory applied to physical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(7), 1444–1469. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000420

- Visser, E. K., Kuypers, M. M. F., Stam, J. S. M., & Riedstra, B. (2019). Practice of noseband use and intentions towards behavioural change in Dutch equestrians. Animals, 9(12), 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9121131

- Visser, E. K., & Van Wijk-Jansen, E. E. C. (2012). Diversity in horse enthusiasts with respect to horse welfare: An explorative study. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 7(5), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2011.10.007

- Warren-Smith, A., & McGreevy, P. (2008). Equestrian coaches’ understanding and application of learning theory in horse training. Anthrozoös, 21(2), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303708X305800

- Webb, H. J. (2021). The influence of social and psychological factors on practices and performance of Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) endurance rider-owner-trainers in Aotearoa/New Zealand [Doctoral dissertation, Massey University]. http://hdl.handle.net/10179/17632

- Werhahn, H., Hessel, E. F., & Van den Weghe, H. F. A. (2012). Competition horses housed in single stalls (II): Effects of free exercise on the behavior in the stable, the behavior during training, and the degree of stress. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 32(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2011.06.009

- Wess, L., Böhm, A., Schützinger, M., Riemer, S., Yee, J., Affenzeller, N., & Arhant, C. (2022). Effect of cooperative care training on physiological parameters and compliance in dogs undergoing a veterinary examination – A pilot study. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 250, 105615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2022.105615

- Wilson, P. M., Mack, D. E., & Grattan, K. P. (2008). Understanding motivation for exercise: A self-determination theory perspective. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012762

- Wipper, A. (2000). The partnership: The horse–rider relationship in eventing. Symbolic Interaction, 23(1), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2000.23.1.47

- Wood, G. (2023). Talking horses: Jockeys’ union exodus should worry everyone in racing. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/blog/2023/may/09/talking-horses-professional-jockeys-association-exodus-should-worry-everyone-in-horse-racing

- Wright, D., & Meadows, D. H. (2009). Thinking in systems: A primer. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849773386

- Wu, J., Saxena, G., & Jayawardhena, C. (2015). Does age and horse ownership affect riders’ motivation? In C. Vial & R. Evans (Eds.), The new equine economy in the 21st century (pp. 113–122). Wageningen Academic Publishers. https://doi.org/10.3920/978-90-8686-824-7

- Zebisch, A., May, A., Reese, S., & Gehlen, H. (2014). Effect of different head–neck positions on physical and psychological stress parameters in the ridden horse. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 98(5), 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpn.12155