ABSTRACT

Historically, domestic cats (Felis catus) were kept primarily to control rodent populations, retaining a relatively independent status as a companion animal (pet) who roams outside at their leisure. However, the Anthropocene presents concerns regarding the impact of predation by cats on wildlife, and the increasingly common “indoor-only cat” is also a response to the various risks encountered by roaming cats in modern societies. Contemporary cat–human relationships are explored here by analyzing discourses surrounding the indoor/outdoor cat debate from the perspectives of cat guardians (owners). A qualitative analysis was performed on 961 online user comments responding to media related to predation by cats or discussing the merits of keeping companion cats indoors. A thematic discourse analysis provides insight into how the practices and beliefs surrounding cat guardianship are influenced by media reporting, preconceived notions of cats, and personal experiences of living with cats. Whether cat guardians believe they are morally obligated to protect their feline companions or must respect their freedom to roam appears to depend upon how cats are perceived on a spectrum from child-like dependents to independent or wild-like animals who are not fully domesticated. Using a framework of “pet parenting styles,” this paper examines how roles and responsibilities of cat guardians are constructed differently in relation to the indoor/outdoor cat debate and how feline “pet parenting” norms might be changing in contemporary risk societies that increasingly promote practices that restrict the roaming of companion cats.

The relatively recent phenomenon of keeping domestic cats (Felis catus) indoors began gaining momentum following the commercialization of “kitty litter” for cat toilets in the 1950s (Grier, Citation2010). The increasing popularity of indoor-only cats is in part a response to the various dangers roaming cats face, such as busy roads and predators, and in part due to concerns over cats predating on wildlife (e.g., Foreman-Worsley et al., Citation2021; Hall et al., Citation2016; Rochlitz, Citation2004; Tan et al., Citation2020). Concerns regarding predation of wildlife have led to bylaws restricting cat roaming in parts of New Zealand (Sumner et al., Citation2022), Australia (Legge et al., Citation2020), and North America (Booth & Otter, Citation2022; Tan et al., Citation2020) and an ongoing debate in Europe (Trouwborst & Somsen, Citation2020). US cat guardians (owners) are more likely to confine their companion cats to the home, including enclosed gardens or patios, and supervise any outdoor time (e.g., leash walking) than those in the UK (Foreman-Worsley et al., Citation2021; Hall et al., Citation2016). Acceptance and normalization of the practice of keeping cats confined to the home (including outdoor enclosures) is influenced by both conservation and cat welfare groups (Hill, Citation2022; Marra & Santella, Citation2016).

There is some evidence that predation by domestic cats is not an ecological concern in Britain (Palmer, Citation2022), although many laypersons disagree and others express distain toward roaming cats (Hill, Citation2022, Citation2023). This has led to conflict between those adamant cats need to roam and by those concerned about predation or bothered by “nuisance” behaviors, namely unwelcomed garden visits and defecation (Bjerke & Østdahl, Citation2004; Crowley et al., Citation2022; Hill, Citation2022, Citation2023). This is the premise behind the indoor/outdoor cat debate, which is the focus of a larger study of discourse surrounding roaming cats (Hill, Citation2023). In the current study, I focus on (owned) companion cats and address two key questions: (1) What might discourses related to the indoor/outdoor cat debate say about how guardians relate to their cats? and (2), How might the decisions to restrict roaming affect the cat–human bond?

The discourses examined here demonstrate the multitude of ways cat guardians perceive cats and the different opinions regarding how cats should behave or should be treated. Informed by the key themes that emerged from the discourse analysis, I first look at different perceptions of cats as companion animals and opinions regarding the indoor/outdoor cat debate from a feline welfare/wellbeing perspective.

Companion animals are commonly described as being family members (Charles, Citation2014; Charles & Davies, Citation2008; Finka et al., Citation2019; Owens & Grauerholz, Citation2019), and several scholars have written about interspecies kinship bonds (e.g., Brandes, Citation2009; Charles, Citation2016; Hill, Citation2020; Irvine & Cilia, Citation2017). In a previous study, I found narratives associated with tattoos dedicated to a companion animal exhibited elements of child–parent, dependent–caregiver, friend, confidant, and soulmate-type relationships (Hill, Citation2020), which supported the idea that there is not one type of generic guardian–companion animal bond (Bouma et al., Citation2022; Cain, Citation2016; Fox & Gee, Citation2019; Stewart, Citation2018; Walsh, Citation2009). However, as Fox (Citation2006) pointed out, a companion animal in contemporary society inevitably occupies a “dual status as both a ‘person’ and possession” (p. 528). The legal status of companion animals is as “property,” even though this is often “inconsistent with their current cultural status as quasi-family members” (Pallotta, Citation2019, p. 2). The human is invariably the dominant partner, and especially for bonds established during adulthood, the guardian typically describes a role akin to a parent or guardian (Greenebaum, Citation2004; Hill, Citation2020; Stewart, Citation2018). Therefore, I explore the concept of pet parenting styles, previously adapted from the parenting literature for understanding dog–guardian relationships (van Herwijnen, Citation2020; van Herwijnen et al., Citation2018, Citation2020). This framework provides a potential method to gain further insight into how guardians relate to their cats and how this might be changing in contemporary risk societies. The concept of a “risk society” relates to how we experience risks to our bodies and the environment and how these are managed (Beck, Citation1992; Giddens, Citation1990). A risk society is defined by an increasing potential for anthropogenic disasters and dangers from technological hazards, a growing distrust of scientists, professionals, and policymakers, and a loss of faith in current social structures and institutions to protect individuals. Perceptions of risk affects all areas of life, including how we parent children (e.g., Harper, Citation2017; Hoffman, Citation2010; Jenkins, Citation2006; Lee et al., Citation2010; Smeyers, Citation2010) and relate to companion animals (Fox & Gee, Citation2019; Walby & Doyle, Citation2009).

Methods

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Exeter College of Social Science and International Studies (SSIS) Ethics Committee on August 1 2019. The data comprise comments retrieved from the comment sections of online news websites or similar platforms (). Unlike social media exchanges, comments responding to articles on a publisher’s website tend not to be coupled to a maintained online profile or social network (Hlavach & Freivogel, Citation2011; Nielsen, Citation2014). Thus, a caveat of this type of research is that a person might not be who they say they are and use an anonymous voice to express extreme opinions or provoke discord. Conversely, anonymity can give a voice to opinions and attitudes that do exist but are controversial or unpopular (Markham, Citation2004; Nielsen, Citation2014). Furthermore, the articles themselves are leading and attract opinionated reactions and responses. Therefore, discourses may be less nuanced and more polarizing than elsewhere. Nonetheless, they provide insight into various discourses that exist and how opinion and biases are formed.

Table 1. Overview of the comment data sources.

The data collection and first-level coding methods described below come from a larger study and are also described elsewhere (Hill, Citation2022, Citation2023). The first set of comments retrieved were responses to a short video shared on Jackson Galaxy’s YouTube channel that directly addresses the issue of whether guardians should restrict the roaming of their companion cats (). The first 1,200 comments were included in the analysis because they represented all time zones within a 24-hr post-release timeframe. The second source was actively sought out to collect responses on the same topic (restricting the roaming of companion cats) from a different readership. The selected article was published in Science-Based Medicine (SBM), an online magazine exploring issues and controversies in the relationship between science and medicine. Additional comments were selected from online news sources that published articles related to free-living (unowned) or roaming companion cats between January 2019 and October 2020 (). The selection criteria for the news articles required they (1) were published online by a newspaper platform that allowed users comments, (2) were focused on roaming cats (owned or unowned), (3) had more than 50 comments, and (4) had comments primarily written in English by users identifiable as US, UK, Australian, or Canadian residents. Complete comments were uploaded to an Excel sheet, together with the origin source code, a chronologically assigned number, and any other information provided (see Hill, Citation2023 for a comprehensive description of how the Excel sheets were constructed).

Comments were first sorted into three broad groups corresponding to discourses focused on (1) cat welfare/wellbeing and cat–guardian relationships, (2) wildlife predation by cats, and (3) cats in the community. This “holistic coding” approach is a process whereby a single identifier is “applied to each large unit of data in the corpus to capture a sense of the overall contents and the possible categories that may develop” (Saldaña, Citation2013, p. 141). The comments within each group were subsequently coded independently. Group 2 and Group 3 comments are those related to wildlife and cats in the community, respectively, and are examined elsewhere (Hill, Citation2022, Citation2023). The current paper focuses on 961 comments with content related to the welfare and wellbeing of companion animal cats (Group 1). Source codes are used to reference comments in-text, together with a chronologically assigned number (e.g., GJ657, SBM26).

The chosen approach to qualitative analysis entailed labeling comments based on a specific feature (coding) such that they can be retrieved and inspected together with similarly coded data (Saldaña, Citation2013). Coded comments could be readily retrieved, re-coded, and re-examined within their original context. This approach enabled the decontextualization of data and re-contextualization into a given theme. Furthermore, newly identified themes could be used to inform and facilitate subsequent coding within an iterative process (Ayres, Citation2008; Saldaña, Citation2013). The purpose of thematic analysis is to elucidate themes that can be synthesized and from which generalizations can be derived (Saldaña, Citation2013). Coding for thematic analysis produces a list of themes that are descriptive, and interpretation of these themes comprise the current paper.

The entire comment was first coded based on whether it was deemed pro-confinement (confinement favored) or pro-roaming (roaming favored). Many comments expressed degrees of nuance and recognized that although they believed confinement or roaming to be preferable, it was not always possible or even desirable (see the “But it depends [on]” subcodes in ). For some a preference toward roaming or confinement could not be discerned (coded “It depends” in ). The comments coded “Confinement favored” were based on a reason why, namely health concerns (usually talking about a specific cat), cat safety concerns (traffic, getting lost, attacked, or stolen), or because they “learned the hard way” (injury or death of a beloved outdoor cat). Those comments mentioning methods for enrichment or supervised outdoor time were also tagged with searchable codes. Similarly, comments coded “Roaming favored” were assigned sub-codes related to underlying reasons. For example, this could be because they failed to keep the cat inside or that the cat seemed unhappy (The cat insisted), because a human prefers it that way (due to allergies or convenience), or simply because they are responding with rural barn cats in mind (Barn/working). There is also the belief that cats cannot be happy unless they are able to roam and even that restricting roaming is akin to imprisonment (“Imprisonment”).

Table 2. Counts of coding and sub-coding of Group 1 comment.

Comments discussing risk-reduction strategies (such as collars or training cats to come in at night) were likewise coded as “Risk reduction.” Comments were also coded for discourse related to a geographic or “Cultural perspective,” or reference to the heated nature of the debate surrounding indoor versus outdoor cats (Nature of the debate). Comments containing stories of cat predation written by a cat guardian (Prey/hunting stories) were coded and later sub-coded based on the guardian’s attitude. The subcategories represented a reluctant acceptance that cats hunt (Rather they didn’t), a conviction their cat did not hunt live prey (Denial), and a certain pride in their cat’s hunting prowess (Pride). Some of the comments had content that was coded to more than one of these, and final counts for the number of comments assigned to the various codes are provided in .

Results

Most comments from those expressing a concern for cat safety and wellbeing could be coded as favoring either cat confinement or providing the freedom to roam (). From a cat wellbeing perspective, 398 comments favored confinement of companion cats and 496 comments expressed an opinion that allowing cats to roam freely for at least part of the day or night was the ideal scenario (). However, many of the latter group acknowledged this was not always possible and that confining cats was permissible or necessary under some circumstances.

The Heated Nature of the Indoor/Outdoor Cat Debate

Debates surrounding roaming cats (owned and unowned) oftentimes polarize and attract those with strong opinions (Gow et al., Citation2022; Hill, Citation2022; Lynn & Santiago-Ávila, Citation2022; Marra & Santella, Citation2016; Wald & Peterson, Citation2020). This is something that surprised those new to such discussions, evidenced by comments such as “I've never heard of this debate before” (GJ657). Despite the surprise to the uninitiated, the controversial nature of the indoor/outdoor cat debate was all too familiar with those who have engaged in online discussions. In response to Jackson Galaxy’s video, one commenter wrote, “Thank you for saying this! People always get so militant about keeping cats inside and assume everyone should do the same” (GJ149). Another claimed, “I’ve heard people online calling indoor cat owners ‘evil’ and ‘cruel’, which made my blood boil” (GJ306). Commenters also indicated they had been subjected to strong opinions from in-person interactions too. One said, “After making a permanent enemy in pottery class by sharing on this topic, it is with trepidation that I admit that my cat does go outdoors” (SBM26). Another remarked, “I have friends that don't let their cats outside who judge me for letting mine out” (GJ34). From the other side, yet another person said, “My family always says I am mean for not letting my cat outside but i want him to live a long life” (GJ351).

Regarding cat welfare, the two extremes are “it is cruel to keep a cat inside” versus “it is irresponsible to endanger your cat by letting them outside.” A handful of strong opinions expressed the notion that those whose living arrangements were not compatible with safe roaming should not keep cats. For example, one comment stated, “If you do not live in an area that is capable of supporting that lifestyle you do not deserve a cat” (GJ1102). At the other extreme, those who let their cats roam were berated and branded as “irresponsible” or “uncaring” cat guardians. Some even went so far as to attack individuals in their responses, saying “I think your[sic] a crappy cat owner for letting your cat outside” (GJ96). Similar to how user comments engage with media content related to predation by cats (Hill, Citation2022), the majority of responses from the cat welfare/wellbeing perspective seem not to be influenced by the original source content. Especially amongst the comments responding to news articles about predation by cats (), many commenters appear not to have read beyond the headline. It was less obvious if the same was occurring in response to the YouTube video titled “Indoor Cat Vs. Outdoor Cat?” (Galaxy, Citation2019), but the responses indicate the content had little impact beyond reinforcing prior conviction in favor of keeping cats indoors or inducing others to vehemently disagree.

Reasons Behind the Indoor Preference: It’s Not Safe Out There!

From a feline welfare perspective, reasons provided for not allowing a companion cat to roam included various dangers, and these were sometimes coupled with a story of how a guardian had “learned the hard way.” Dangers discussed varied by region and included wildlife attacks on cats, traffic, malicious humans, and attacks from other domesticated animals (primarily dogs). The hazards posed by traffic and busy roads was something brought up time-and-time again in the comments. First-hand experiences of losing a cat to a motor-vehicle collision often underpinned a conversion to indoor-only arrangements for future cats. Frequently these traffic-related deaths involved childhood family cats, leading to adulthood resolutions not to allow future feline family members to suffer the same fate. Not specific to any country or region, the traffic risk is a local one that depends on the proximity of a particular cat’s home-range to busy roads. This is something commenters frequently acknowledged; for example, explaining how “Living in the suburbs near a busy road having our cats go outdoors is not an option” (GJ1166).

Roaming companion cats are subjected to well-intended, but sometimes misguided, actions, such as inappropriate feeding or “rehoming.” One commenter recanted how they found their cat had been taken by their neighbor: “My cat used to be indoor/outdoor, but then she was kidnapped by a neighbor for three days until I discovered her in their window” (GJ326). Especially when a cat is not microchipped or ID-tattooed and/or is not wearing a collar and nametag, intentional “kidnap” is hard to prove. However, microchipping is no guarantee a cat will not be intentionally taken. One commenter warned of dog fighting rings: “Outdoor cats can also have the risk of being caught by dogfighters (there was a ring near me the police broke-up not that long ago)” (GJ775). Neighborhood dog guardians were sometimes accused of allowing their dogs to run wild and attack cats, with comments that claimed, “there are cat-killer dogs around here” (SBM12).

The decision to keep a cat indoors is oftentimes influenced by a personal loss, with tragic stories being rife amongst commenters (coded as “learned the hard way,” see ). The comments related to potential dangers encountered by roaming cats revealed how the psychological trauma of losing a beloved cat or the fear of what might happen were prominent drivers to keeping a cat safely indoors. While some seemed able to accept the potential risks to their cats’ safety if they believed the cat was happier roaming, others could not. For example, “But it's also the case of my anxiety – I would die of fear if she wasn't in, safe and comfy” (GJ172), or “My stepdaughter would be devastated if anything happened to her fur baby” (GJ766). In many of these examples, human discomfort was being prioritized over any notion that the cat might prefer to be free to roam.

Reasons Behind the Outdoors Preference: A Life in Prison Is No Life!

Despite the warnings and known dangers, some remained adamant that cats need to be outside to live happy lives. These guardians care very much for their roaming cat but have decided that their own anxiety and potential grief is a price they must pay for their cat’s happiness. This reflects the hedonistic welfare perspective, used by Abbate (Citation2020) to argue that guardians have a moral duty to permit their cats to roam if it confers more pleasure (or happiness) than pain (or suffering).

Husbandry-related preferences (namely insisting a cat stayed outside most of the day and/or night) were occasionally cited from the perspective of allergies amongst human family members or aversions to litter boxes (coded as “Because of a human,” ). For example, statements such as “I would have all my cats inside if everyone wasn't allergic to them” (GJ292), and “Outdoor Always – at least your house won't be the sole place a kitty can defecate” (GJ752). A few commented about their cats being “barn cats” who have a job to do catching rodents. However, the primary reason for favoring roaming was the cat’s happiness/mental wellbeing. Stories about cats who refused to stay inside were also common, reinforcing the commenter’s belief that the cat’s preference is to roam.

Even those who said they kept their cats indoors sometimes indicated the ideal scenario would be the cat being able to roam safely. Indeed, the premise behind keeping a cat confined was often framed as a compromise, because roaming was deemed too risky. Of those favoring keeping cats inside for their own safety, many indicated they wished their cats could roam:

If I lived in a farm or had plenty of green space, I could think of an indoor/outdoor balance, but since I live in a big city, I stick with keeping cats indoor only. Safety matters. (GJ375)

Take an indoor cat and give it a taste of the outdoors and then see how fond it is of indoor-only life. Actually, they just like the freedom to come and go as they please. (SBM16)

The Predation Problem

Feline hunting habits can be a conundrum for those who believe roaming to be fundamental to their cats’ quality of life but have concerns about them predating on wildlife (Crowley et al., Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2022). I coded 80 comments that shared stories or attitudes from cat guardians related to their cats’ hunting prowess (). These could be subdivided into three categories: (1) “Rather they didn’t,” which was a begrudging acceptance of hunting behaviors, similar to Crowley et al.’s (Citation2020) definition of “Tolerant Guardians,” (2) a denial of their cats’ hunting, and (3) a certain pride in their cats’ hunting prowess. Although wildlife predation was cited by many within the larger dataset as a reason to keep cats confined (Hill, Citation2022), for many this was viewed an unsavory part of having a roaming companion cat. Amongst advocates for roaming cats, the killing of wildlife was more often accepted, or ignored as an unfortunate state-of-affairs. These ambiguous feelings toward the feline species, where they are simultaneously loved for their “cat-like” activities (hunting) but disfavored for the outcome of that activity (the death of small animals), were not uncommon. However, for many cat guardians this was clearly secondary to their cat’s wellbeing and their belief that cats have a right to enjoy their freedom.

Guardian Compromises and Accommodations

There were comments that recognized that “what is best” also depends on the cat themselves and how the cat was raised. Throughout the comments there was the recognition that effective compromises existed that can reduce predation, increase outdoor safety (Risk reduction), or enrich the lives of indoor-only cats (Enrichment, ). The latter includes sufficient indoor enrichment and playtime/interactions, enclosed gardens, catios, supervised outdoor time, and leash walking. For example:

My cats are indoor with supervised outdoor time. They can only go out with [me] or my husband and when we want. They all have been trained to come with a general kitty, kitty call or by their name. (GJ156)

We rescued a cat that was already declawed [sad face] he loves to be outside but we worry and want him healthy so we walk him or let him outside and sit outside to watch him and make sure he is ok. (GJ24)

Table 3. Comments on enrichment for indoor cats.

Particularly in the US, harness training cats is becoming increasingly popular (Galaxy, Citation2021). Respondents to the Jackson Galaxy video shared stories about how their cats enjoyed going out for walks. However, not all cats take to the harness and several commenters shared stories of their failures, such as, “I tried to harness train my cat. She acted like I was trying to kill her” (GJ207). While some insisted it is “easy” to harness train cats, others recognized that it really depends on the cat, especially when they have had different results with different cats:

Harness training was easy for our 1 cat. He loved it instantly. The other pancakes [a form of resistance]. (GJ1045)

I'm surprised he didn't mention possibilities of a pet stroller too. I have one and man my cat loves going out in it for a walk with me and especially at night, sometimes, after 9 he jumps in it and meows at me, letting me know hey he wants to go outside. (GJ261)

Discussion

Risk Perception and Cat Guardianship

The extent of the actual versus perceived risks roaming cats face cannot be determined from anecdotal accounts described in the comments, especially when location or other variables are not provided. Nonetheless, many of the risks discussed in the comments exist to varying degrees (Tan et al., Citation2020). A few individuals claimed to have first-hand experience of witnessing animal abuse in their neighborhood. The most common accusation was intentional poisoning of cats, but this is not so easy to verify as accidental poisoning by careless individuals is not uncommon (Loyd et al., Citation2013; Tan et al., Citation2020). Likewise, the relatively prevalent belief amongst commenters that some people intentionally run over cats is hard to prove. However, trauma from traffic-related incidents is a common cause of death for companion cats, especially amongst younger cats (Conroy et al., Citation2019; O’Neill et al., Citation2015; Wilson et al., Citation2017). Even though many comments deemed the UK countryside to be relatively safe for cats, research demonstrates that the highest odds of a cat being involved in a traffic-related accident in the UK is on countryside roads (Wilson et al., Citation2017). However, experiences of losing a cat (coded as “learned the hard way,” ) often led to a change of heart. Independent of a growing awareness of the negative impact cats can have on local wildlife, the discourses demonstrate a fear for their cat’s safety is a prominent driver for many guardians to keep their cats inside.

Risk can be understood as a culturally constructed phenomenon, sometimes adapted as a political narrative, but the underlying social factors leading to various risk perceptions are often poorly understood and independent of the objective risk (Burgess, Citation2006). That is not to say that risks are not real but that risk management requires an understanding of both the objective risk and the underlying social factors of how risk is experienced. Burgess (Citation2006) warns that “a consequence of over objectification is that attention remains focused upon the ‘risk object’ rather than the reactions associated with it” (p. 340). This is especially relevant when the perceived risk is disproportionate to actual risk. An understanding of how cat guardians perceive risk to their cats is fundamental to a range of educational endeavors related to cat welfare, as well as effective enforcement of cat curfews in areas where predation by cats is a problem. Although not the focus of the current paper, cats are an ecological threat to wildlife populations in many regions (Dickman, Citation2009; Doherty et al., Citation2016; Loss & Marra, Citation2017; Medina et al., Citation2011; Pavisse et al., Citation2019), and studies have examined how this threat is perceived by cat guardians (Crowley et al., Citation2019; Hall et al., Citation2016; Hill, Citation2022; van Eeden et al., Citation2021; Wald et al., Citation2013). Risk discourses examined here provide insight into how guardians perceive and manage the potential hazards of roaming from a predominantly cat wellbeing perspective.

However, the question of whether the benefits outweigh any risk to the cat is subjective to our beliefs surrounding the roles and responsibilities toward other animals (including cats and wildlife). Palmer and Sandøe (Citation2014) challenged the ethics of confining cats “for their own good” and refuted general claims that routine confinement is in the cats’ best interests. They argue that to confine companion cats is to impose a paternalistic restriction on cats’ freedom, without their consent or agreement (Palmer & Sandøe, Citation2014). That is not to say that some cats in some circumstances are not better off being kept indoors (something Palmer & Sandøe, Citation2014 acknowledge). However, it may be in the guardian’s best interest to know their cat is safe, which seemed to be a driving force behind some of the discourses examined here. Risk awareness and avoidance measures change relationships between companion cats and their guardians. This reflects that of parenting and childhood in risk societies, whereby increased global communications have raised awareness of potential dangers and introduced new expectations for safety measures (Beck, Citation1992; Giddens, Citation1990; Harper, Citation2017; Jenkins, Citation2006). However, it has been argued that some efforts to “protect” children can harm them by inhibiting the development of key skills, inducing anxiety, or other contributing health risks associated with physical inactivity (Tremblay et al., Citation2015). Particularly relevant here are the similarities between risk discourses associated with children playing outdoors, especially unsupervised, or traveling unaccompanied. Similar to the cat guardian discourses examined here, there is an internal conflict amongst parents who wrestle with a need to know their children are safe and a recognition that some risk is necessary for child development and a happy childhood (Jenkins, Citation2006; Smeyers, Citation2010).

How risk is perceived and expectations regarding risk management are influenced by society via child protection laws, parental education, social norms, and media portrayal of potential dangers. National and cultural differences underlie parenting expectations, practices, and social norms (Lansford et al., Citation2018; Smetana, Citation2017; Smeyers, Citation2010), and national differences regarding roaming companion cats have been reported (Foreman-Worsley et al., Citation2021). Consistent with the findings of Foreman-Worsley et al. (Citation2021), comments identifiable as being from US cat guardians appear to accept confinement more readily as a feasible and ethical solution to reduce predation and to keep their cats safe. This correlates with the predominant message promoted in the US being that confinement is “what’s best for cats” (Palmer & Sandøe, Citation2014, p. 135). Veterinarians in the US are encouraged to “educate clients and the public about the dangers associated with allowing cats free roam access to the outdoors” (AVMA, Citationn.d.). The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP, Citation2007) took the same position and listed “Vehicles, Attacks from other animals, Human cruelty, Poisons, Traps, and Diseases” as reasons to encourage guardians to keep their cats confined.

The lay discourses surrounding roaming cats is influenced by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) in the UK and the National Audubon Society in the USA (Hill, Citation2022). Contrary to the RSPB’s more lenient stance on roaming cats, the National Audubon Society is a proponent of cat confinement to protect wildlife (Hill, Citation2022; Marra & Santella, Citation2016; Wald & Peterson, Citation2020). This likely influences a tendency amongst UK cat guardians to retain a conviction that cats who roam have a better quality of life. It may also reflect the historical development of risk societies in the US versus Europe, where the interaction between the global, regional, national, and local manifest as distinct “glocalized” (emergent) discourses (Burgess, Citation2006; Chernilo, Citation2021; Roudometof, Citation2005). The concept of glocalization has been used as a framework to understand how online news is consumed and explains how concerns and discourses related to predation by roaming cats are filtered through a local lens (Hill, Citation2022; Lee, Citation2005). A similar phenomenon is apparent amongst the discourses examined here, whereby the comment function was being used to express or assert an opinion rather than engagement with new information.

The notion that hunting behavior is a prerequisite for a full and happy life is prevalent amongst the comments, even amongst indoor-only advocates who recognize play that mimicks the stalking and chasing of prey is important. Arguably, at least for cats fed by humans, it is not the kill that is important to feline wellbeing but the associated stalking and hunting behaviors. Adequate environmental enrichment can facilitate the expression of the species-specific behaviors necessary for happy, healthy cats (Herron & Buffington, Citation2010; Kasbaoui, Citation2016; Rochlitz, Citation2005). However, ensuring adequate environmental enrichment means caring for indoor cats entails more work. The notion of cats as “low maintenance pets” appeared more prevalent within discourses identifiable as originating from UK guardians. This is an attitude that needs to change when cats are kept indoors. The concern that cats might become bored or overweight can be countered by adequate enrichment and interactions (Herron & Buffington, Citation2010).

A study of cat guardians demonstrated that those who played with their cats more often, and/or provided stimulative environments, reported fewer behavioral problems (Strickler & Shull, Citation2014). However, a study of Portuguese households with indoor cats found a general lack of knowledge regarding the benefits of feline environmental enrichment and that the time-consuming implementation of some measures deterred some guardians from implementing them (Alho et al., Citation2016). Similarly, a study of Australian households found the needs of many indoor cats were not being adequately met, leading the authors to conclude that better education was needed to avoid health and behavioral issues (Lawson et al., Citation2020). In the US there has been a conscious effort by veterinary and animal welfare organizations to educate guardians on how to best provide for their indoor cats (AAFP, Citation2011), and this seemed to be reflected in the comments identifiable as being from the US tending to be more knowledgeable regarding the need for environmental enrichment and interactive play.

Fur Babies and Feline Agency: Different Pet Parenting Styles

Building upon a hedonistic account of animal wellbeing based on feline ethological traits, Abbate (Citation2020) made a philosophical argument that cat guardians have a moral duty to provide their feline companions the opportunity to roam outside. Fischer (Citation2020) contested this argument by comparing feline companions to a small child who loves to wander unaccompanied, pointing out that as a parent you would be accountable for both the child’s safety and any damage they might cause to others. However, this argument relies upon the assumption that companion cats, like small children, are dependents who we have a moral duty to protect and police. Not everyone agrees, and many comments in the dataset asserted that cats are not helpless dependents and that their agency should be respected. Whether one follows the arguments of Abbate (Citation2020) or Fischer (Citation2020) is dependent upon how the cat–guardian relationship is defined.

While national differences of acceptance and normalization of cat care practice exist, clear differences emerged in how individuals related to their cats. There were examples of cats who somehow acquired a human “friend,” and the resulting relationship was more of mutually agreed friendship. However, it was less common that cats were considered free agents who come and go as they please. More often the discourses about “responsible” cat guardianship reflected child–parent/guardian relationships. These ranged from cats being likened to small children who needed constant protection, to teenagers who required more freedom, however much worry that might incur. One commenter retorted to the statement “cats are happier outside” with “Hey why don’t you just put your toddler outside too, they’re happier and who cares how safe they are!” (GJ825).

The idea that cats should be likened to older children or teenagers and granted some freedom were reflected in comments such as “If I let my children live inside to keep them safe from ‘evil people,’ ‘disease,’ and ‘cars,’ people would call me cruel” (GJ230). Arguably, when applied to human minors, the age of the children would dictate the severity of any “cruelty” accusations. Furthermore, there are vastly differing opinions and accepted norms regarding how much freedom parents should grant their human children and at what age, which is partly influenced by socioeconomic status and ideas about gender (Jenkins, Citation2006; Soori & Bhopal, Citation2002). On the one hand, overprotective parenting styles can stifle child development or quality of life and cause anxiety (Tremblay et al., Citation2015). On the other hand, too much freedom might expose them to unacceptable risks. However, a large multinational study found the risks perceived by parents regarding various dangers young children might encounter were often grossly under- or over-estimated (Vincenten et al., Citation2005).

An important distinction between children and cats is that the former represents a range of juvenile development stages from toddler to teenager, and parenting practices adapt as children progress toward adulthood and independence. Conversely, companion animals invariably remain dependent on their guardian (or other humans) their entire adult life. As a domesticated species, it has been argued that cats (and dogs) implicitly entered a “domesticated animal contract” that rendered them subject to human governance and guardianship (Budiansky, Citation1992; Palmer, Citation1997). However, animal studies scholars challenge the dominance model of human relations with other animals, including the ethics of “pet keeping” (Fox, Citation2006; Redmalm, Citation2020; Wadiwel, Citation2015; Yeates & Savulescu, Citation2017). Nonetheless, the popularity of cats as companion animals is unlikely to wane anytime soon.

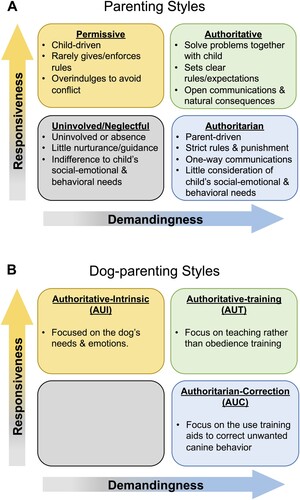

Whether for their own good or to protect wildlife, it is likely that the trend toward practices of confining companion cats to the home will continue to gain momentum. The guardian’s persistence or abandonment of attempts to confine a cat also says something about how authoritative or responsive a guardian is to their cat’s needs. Parenting styles within the context of human–child relations have been defined as variations within two dimensions: Demandingness and Responsiveness ((a)). The former is authoritative and driven by parental and societal expectations; the latter is more supportive and led by the child’s needs (Baumrind et al., Citation2010). Similar “parenting” styles may also underpin how much a guardian will respond to a cat who is showing signs of distress – either doubling down on indoor enrichment and behavioral intervention or reluctantly agreeing their cat can go outside.

Figure 1. Parenting styles within the two dimensions of Responsiveness and Demandingness. Parenting styles are shown within the two dimensions of Responsiveness and Demandingness for parent–child (a) and dog guardian–dog (b), according to van Herwijnen et al. (Citation2018).

van Herwijnen et al. (Citation2018) analyzed dog–guardian parenting styles and found similarities with two out of the four human–child parenting styles (permissive, authoritative, authoritarian, and uninvolved/neglectful) ((b)): the authoritative style and two variations of the authoritarian parenting style. The authoritarian-correction (AUC) style is characterized by the use of training aids to correct unwanted canine behavior, the authoritative-intrinsic (AUI) style focuses on the dogs’ needs and emotions, and the authoritative-training (AUT) style emphasizes teaching rather than obedience training (van Herwijnen et al., Citation2018). These canine parenting styles emerged in part from how the dogs were viewed as either humanized family members or subordinates who needed strict guidance (van Herwijnen et al., Citation2020). Similarly, cat-directed parenting styles might also be determined in part by how the cats are perceived – as vulnerable dependents or free agents.

Permissive parenting is the opposite of authoritarian, with permissive parents wanting to be their child’s best friend; uninvolved/neglectful parenting takes the “hands off” approach (Sanvictores & Mendez, Citation2022). These two styles arguably define the prominent approaches to cat guardianship evidenced by many of the comments. However, the increased interest in cat training (Bradshaw & Ellis, Citation2017) may lead to more “dog-orientated” styles of parenting. Certainly, further study of cat parenting styles is warranted to unpack and determine how different styles might impact the wellbeing of adult cats and the social development of kittens.

Conclusions

One key theme throughout the comments is actual and perceived dangers faced by roaming cats. These included traffic, wild predators, dogs, or malicious humans. Unintentional hazards to cats, created by humans, include rodent poison; slug pellets; anti-freeze; farm, garden, or building machinery; getting trapped in vehicles and outbuildings; and threats from domestic animals such as dogs and other cats. While perceived risk need not necessarily correlate with actual risk, there was no short supply of tragic stories that led people to keep future cats inside. However, some believe the risks outweigh the benefits and that cats need to roam for a full and happy life. The question of whether cat guardians are morally obligated to protect their feline companions or to respect their agency to roam depends upon where cats are perceived on a spectrum from child-like dependents to fully adult persons.

My study revealed that guardian perceptions of companion animal cats can be broadly grouped as comparable to (1) a child-like dependent, (2) a teenager who needs some guidance, or (3) a free agent who should be permitted to come and go as they please. Less prevalent were references to cats as individuals with different wants and needs, which may be due to the polarizing nature of the indoor/outdoor cat debate and how this type of study is biased toward the more opinionated voices. However, cat personality can be subjectively measured (Litchfield et al., Citation2017; Mikkola et al., Citation2021), and different cats may prefer different lifestyles (or parenting styles). Human personality may also link into the different attitudes and opinions regarding feline guardianship. Neuroticism is associated with a decreased likelihood of guardians permitting their cats to roam unaccompanied, while higher Extraversion scores are associated with the opposite trend (Finka et al., Citation2019). However, what is best for one cat might not be ideal for another, and any welfare decision needs to consider the individual circumstances and disposition of the cat. All these factors ideally need to be taken into consideration when adopting or rehoming a companion cat or when planning to raise a kitten.

Discourses surrounding the indoor-outdoor debate from the cat welfare perspective center on how much risk is acceptable in relation to perceived benefits. However, we cannot ignore the impact roaming cats may have on local wildlife in many regions and how the trend toward confining cats is changing relationships. If cats are to be confined to the home, it is imperative that their physical and mental needs are met. This means that the laissez-faire parenting style (Uninvolved, ) may no longer be acceptable and the perception of cats as “low maintenance” will need to change to avoid health and behavioral issues.

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful to my supervisor Prof. Samantha Hurn for her support and guidance though my doctoral studies, and in the preparation of this manuscript. I also thank fellow postgraduate researchers from the University of Exeter’s department of Sociology, Philosophy, and Anthropology (SPA) for their insightful feedback during the drafting of this manuscript. Gratitude is further owed to the anonymous reviewers who provided insightful comments that ultimately contributed to a stronger manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- AAFP. (2007). Confinement of owned indoor cats. American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP). http://www.catvets.com/guidelines/position-statements/confinement-indoor-cats

- AAFP. (2011). Environment enhancement of indoor cats position statement. American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP). http://www.catvets.com/guidelines/position-statements/confinement-indoor-cats

- Abbate, C. E. (2020). A defense of free-roaming cats from a hedonist account of feline well-being. Acta Analytica, 35(3), 439–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-019-00408-x

- Alho, A. M., Pontes, J., & Pomba, C. (2016). Guardians’ knowledge and husbandry practices of feline environmental enrichment. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 19(2), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2015.1117976

- AVMA. (n.d.). Free-roaming, owned cats. American Veterinary Medicine Association (AVMA). https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/avma-policies/free-roaming-owned-cats

- Ayres, L. (2008). Thematic coding and analysis. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 868–869). SAGE.

- Baumrind, D., Larzelere, R. E., & Owens, E. B. (2010). Effects of preschool parents’ power assertive patterns and practices on adolescent development. Parenting, 10(3), 157–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295190903290790

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity (M. Ritter, Trans.). SAGE. (Original work published 1986)

- Bjerke, T., & Østdahl, T. (2004). Animal-related attitudes and activities in an urban population. Anthrozoos, 17(2), 109–129. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279304786991783

- Booth, A. L., & Otter, K. (2022). The law and the pussycat: Public perceptions of the use of municipal bylaws to control free-roaming domestic cats in Canada. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2022.2142059

- Bouma, E. M. C., Reijgwart, M. L., & Dijkstra, A. (2022). Family member, best friend, child or “just” a pet, owners’ relationship perceptions and consequences for their cats. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010193

- Bradshaw, J., & Ellis, S. (2017). The trainable cat: A practical guide to making life happier for you and your cat. Basic Books.

- Brandes, S. (2009). The meaning of American pet cemetery gravestones. Ethnology, 48(2), 99–118.

- Budiansky, S. (1992). The covenant of the wild: Why animals chose domestication. Yale University Press.

- Burgess, A. (2006). The making of the risk-centred society and the limits of social risk research. Health, Risk and Society, 8(4), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570601008321

- Cain, A. O. (2016). Pets as family members. In M. B. Sussman (Ed.), Pets and the family (pp. 5–10). Routledge.

- Charles, N. (2014). “Animals just love you as you are”: Experiencing kinship across the species barrier. Sociology, 48(4), 715–730. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038513515353

- Charles, N. (2016). Post-human families? Dog–human relations in the domestic sphere. Sociological Research Online, 21(3), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3975

- Charles, N., & Davies, C. A. (2008). My family and other animals: Pets as kin. Sociological Research Online, 13(5), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1798

- Chernilo, D. (2021). One globalisation or many? Risk society in the age of the Anthropocene. Journal of Sociology, 57(1), 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783321997563

- Conroy, M., O’Neill, D., Boag, A., Church, D., & Brodbelt, D. (2019). Epidemiology of road traffic accidents in cats attending emergency-care practices in the UK. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 60(3), 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.12941

- Crowley, S. L., Cecchetti, M., & McDonald, R. A. (2019). Hunting behaviour in domestic cats: An exploratory study of risk and responsibility among cat owners. People and Nature, 1(1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.6

- Crowley, S. L., Cecchetti, M., & McDonald, R. A. (2020). Diverse perspectives of cat owners indicate barriers to and opportunities for managing cat predation of wildlife. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 18(10), 544–549. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2254

- Crowley, S. L., DeGrange, L., Matheson, D., & McDonald, R. A. (2022). Comparing conservation and animal welfare professionals’ perspectives on domestic cat management. Biological Conservation, 272, 109659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109659

- Dickman, C. R. (2009). House cats as predators in the Australian environment: Impacts and management. Human–Wildlife Conflicts, 3(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.26077/55nn-p702

- Doherty, T. S., Glen, A. S., Nimmo, D. G., Ritchie, E. G., & Dickman, C. R. (2016). Invasive predators and global biodiversity loss. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(40), 11261–11265. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602480113

- Finka, L. R., Ward, J., Farnworth, M. J., & Mills, D. S. (2019). Owner personality and the wellbeing of their cats share parallels with the parent–child relationship. PLoS ONE, 14(2), e0211862. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211862

- Fischer, B. (2020). Keep your cats indoors: A reply to Abbate. Acta Analytica, 35(3), 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-020-00431-3

- Foreman-Worsley, R., Finka, L. R., Ward, S. J., & Farnworth, M. J. (2021). Indoors or outdoors? An international exploration of owner demographics and decision making associated with lifestyle of pet cats. Animals, 11(2), 253–277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020253

- Fox, R. (2006). Animal behaviours, post-human lives: Everyday negotiations of the animal–human divide in pet-keeping. Social & Cultural Geography, 7(4), 525–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360600825679

- Fox, R., & Gee, N. R. (2019). Great expectations: Changing social, spatial and emotional understandings of the companion animal–human relationship. Social and Cultural Geography, 20(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2017.1347954

- Galaxy, J. (2019). Indoor cat vs. outdoor cat? Jackon Galaxy’s YouTube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ZJ_qkklZyM

- Galaxy, J. (2021). Should you leash walk your cat? Jackson Galaxy Blog. https://www.jacksongalaxy.com/blogs/news/should-you-leash-walk-your-cat-ask-the-cat-daddy

- Giddens, A. (1990). Consequences of modernity. Stanford University Press.

- Gow, E. A., Burant, J. B., Sutton, A. O., Freeman, N. E., Grahame, E. R. M., Fuirst, M., Sorensen, M. C., Knight, S. M., Clyde, H. E., Quarrell, N. J., Wilcox, A. A. E., Chicalo, R., Van Drunen, S. G., & Shiffman, D. S. (2022). Popular press portrayal of issues surrounding free-roaming domestic cats Felis catus. People and Nature, 4(1), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10269

- Greenebaum, J. (2004). It’s a dog’s life: Elevating status from pet to “fur baby” at yappy hour. Society & Animals, 12(2), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568530041446544

- Grier, K. C. (2010). Pets in America: A history. UNC Press Books.

- Hall, C. M., Adams, N. A., Bradley, J. S., Bryant, K. A., Davis, A. A., Dickman, C. R., Fujita, T., Kobayashi, S., Lepczyk, C. A., McBride, E. A., Pollock, K. H., Styles, I. M., van Heezik, Y., Wang, F., & Calver, M. C. (2016). Community attitudes and practices of urban residents regarding predation by pet cats on wildlife: An international comparison. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0151962. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151962

- Harper, N. J. (2017). Outdoor risky play and healthy child development in the shadow of the “risk society”: A forest and nature school perspective. Child and Youth Services, 38(4), 318–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2017.1412825

- Herron, M. E., & Buffington, C. A. T. (2010). Environmental enrichment for indoor cats. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practising Veterinarian, 32(12), E4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21882164

- Hill, K. (2020). Tattoo narratives: Insights into multispecies kinship and griefwork. Anthrozoös, 33(6), 709–726. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2020.1824652

- Hill, K. (2022). Feral and out of control: A moral panic over domestic cats? In I. Frasin, G. Bodi, S. Bulei, & C. D. Vasiliu (Eds.), Anthrozoology studies: Animal life and human culture (pp. 123–157). Presa Universitară Clujeană.

- Hill, K. (2023). A right to roam? A trans-species approach to understanding cat–human relations and social discourses associated with free-roaming urban cats (Felis catus) [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Exeter. ORE Open Research Exeter. http://hdl.handle.net/10871/133691

- Hlavach, L., & Freivogel, W. H. (2011). Ethical implications of anonymous comments posted to online news stories. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 26(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/08900523.2011.525190

- Hoffman, D. M. (2010). Risky investments: Parenting and the production of the “resilient child”. Health, Risk and Society, 12(4), 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698571003789716

- Irvine, L., & Cilia, L. (2017). More-than-human families: Pets, people, and practices in multispecies households. Sociology Compass, 11(2), e12455. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12455

- Jenkins, N. E. (2006). “You can’t wrap them up in cotton wool!” Constructing risk in young people’s access to outdoor play. Health, Risk and Society, 8(4), 379–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570601008289

- Kasbaoui, N. (2016). Risks and benefits to cats of free roaming versus containment [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Lincoln. CORE Lincoln Repository. https://eprints.lincoln.ac.uk/id/eprint/23694/

- Lansford, J. E., Godwin, J., Al-hassan, S. M., Bacchini, D., Bornstein, M. H., Chang, L., Deater-deckard, K., Giunta, L. D., Dodge, K. A., Malone, P. S., Oburu, P., Skinner, A. T., Sorbring, E., Steinberg, L., Tapanya, S., & Alampay, L. P. (2018). Longitudinal associations between parenting and youth adjustment in twelve cultural groups: Cultural normativeness of parenting as a moderator. Developmental Psychology, 54(2), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000416

- Lawson, G. T., Langford, F. M., & Harvey, A. M. (2020). The environmental needs of many Australian pet cats are not being met. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 22(10), 898–906. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098612X19890189

- Lee, A. Y. L. (2005). Between global and local: The glocalization of online news coverage on the trans-regional crisis of sars. Asian Journal of Communication, 15(3), 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292980500260714

- Lee, E., Macvarish, J., & Bristow, J. (2010). Risk, health and parenting culture. Health, Risk and Society, 12(4), 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698571003789732

- Legge, S., Woinarski, J. C. Z., Dickman, C. R., Murphy, B. P., Woolley, L.-A., & Calver, M. C. (2020). We need to worry about Bella and Charlie: The impacts of pet cats on Australian wildlife. Wildlife Research, 47(8), 523–539. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR19174

- Litchfield, C. A., Quinton, G., Tindle, H., Chiera, B., Kikillus, K. H., & Roetman, P. (2017). The “Feline Five”: An exploration of personality in pet cats (Felis catus). PLoS ONE, 12(8), e0183455. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183455

- Loss, S. R., & Marra, P. P. (2017). Population impacts of free-ranging domestic cats on mainland vertebrates. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 15(9), 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1633

- Loyd, K. A. T., Hernandez, S. M., Abernathy, K. J., Shock, B. C., & Marshall, G. J. (2013). Risk behaviours exhibited by free-roaming cats in a suburban US town. Veterinary Record, 173(12), 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.101222

- Lynn, W. S., & Santiago-Ávila, F. J. (2022). Outdoor cats: Science, ethics, and politics. Society & Animals, 30(7), 798–815. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-bja10115

- Markham, A. N. (2004). Internet communication as a tool for qualitative research. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative research: Theory, method and practice (pp. 95–124). SAGE.

- Marra, P. P., & Santella, C. (2016). Cat wars: The devastating consequences of a cuddly killer. Princeton University Press.

- Medina, F. M., Bonnaud, E., Vidal, E., Tershy, B., Zavaleta, E., Donlan, C., Keitt, B., Corre, M., Horwath, S., & Nogales, M. (2011). A global review of the impacts of invasive cats on island endangered vertebrates. Global Change Biology, 17(11), 3503–3510. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02464.x

- Mikkola, S., Salonen, M., Hakanen, E., Sulkama, S., & Lohi, H. (2021). Reliability and validity of seven feline behavior and personality traits. Animals, 11(7), 1991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11071991

- Nielsen, C. E. (2014). Coproduction or cohabitation: Are anonymous online comments on newspaper websites shaping news content? New Media and Society, 16(3), 470–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813487958

- O’Neill, D. G., Church, D. B., McGreevy, P. D., Thomson, P. C., & Brodbelt, D. C. (2015). Longevity and mortality of cats attending primary care veterinary practices in England. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 17(2), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098612X14536176

- Owens, N., & Grauerholz, L. (2019). Interspecies parenting: How pet parents construct their roles. Humanity & Society, 43(2), 96–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597617748166

- Pallotta, N. R. (2019). Chattel or child: The liminal status of companion animals in society and law. Social Sciences, 8(5), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8050158

- Palmer, A. (2022). The small British cat debate: Conservation non-issues and the (im)mobility of wildlife controversies. Conservation and Society, 20(3), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.4103/cs.cs_92_21

- Palmer, C. (1997). The idea of the domesticated animal contract. Environmental Values, 6(4), 411–425. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327197776679004

- Palmer, C., & Sandøe, P. (2014). For their own good: Captive cats and routine confinement. In L. Gruen (Ed.), Ethics of captiviy (pp. 135–155). Oxford University Press.

- Pavisse, R., Vangeluwe, D., & Clergeau, P. (2019). Domestic cat predation on garden birds: An analysis from European ringing programmes. Ardea, 107(1), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.5253/arde.v107i1.a6

- Redmalm, D. (2020). Discipline and puppies: The powers of pet keeping. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 41(3/4), 440–454. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-08-2019-0162

- Rochlitz, I. (2004). The effects of road traffic accidents on domestic cats and their owners. Animal Welfare, 13(1), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/S096272860002666X

- Rochlitz, I. (2005). A review of the housing requirements of domestic cats (Felis silvestris catus) kept in the home. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 93(1–2), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2005.01.002

- Roudometof, V. (2005). Transnationalism, cosmopolitanism and glocalization. Current Sociology, 53(1), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392105048291

- Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Sanvictores, T., & Mendez, M. D. (2022). Types of parenting styles and effects on children. StatPearls Publishing.

- Smetana, J. G. (2017). Current research on parenting styles, dimensions, and beliefs. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.012

- Smeyers, P. (2010). Child rearing in the “risk” society: On the discourse of rights and the “best interests of a child”. Educational Theory, 60(3), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2010.00358.x

- Soori, H., & Bhopal, R. S. (2002). Parental permission for children’s independent outdoor activities: Implications for injury prevention. European Journal of Public Health, 12(2), 104–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/12.2.104

- Stewart, H. (2018). Parents of “pets?” A defense of interspecies parenting and family building. Analize, 2352(1), 239–263. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=734301

- Strickler, B. L., & Shull, E. A. (2014). An owner survey of toys, activities and behavior problems in indoor cats. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 9(5), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2014.06.005

- Sumner, C. L., Walker, J. K., & Dale, A. R. (2022). The implications of policies on the welfare of free-roaming cats in New Zealand. Animals, 12(3), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12030237

- Tan, S. M. L., Stellato, A. C., & Niel, L. (2020). Uncontrolled outdoor access for cats: An assessment of risks and benefits. Animals, 10(2), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020258

- Tremblay, M. S., Gray, C., Babcock, S., Barnes, J., Bradstreet, C. C., Carr, D., Chabot, G., Choquette, L., Chorney, D., Collyer, C., Herrington, S., Janson, K., Janssen, I., Larouche, R., Pickett, W., Power, M., Sandseter, E. B. H., Simon, B., & Brussoni, M. (2015). Position statement on active outdoor play. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(6), 6475–6505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120606475

- Trouwborst, A., & Somsen, H. (2020). Domestic cats (Felis catus) and European nature conservation law: Applying the EU Birds and Habitats Directives to a significant but neglected threat to wildlife. Journal of Environmental Law, 32(3), 391–415. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqz035

- van Eeden, L. M., Hames, F., Faulkner, R., Geschke, A., Squires, Z. E., & McLeod, E. M. (2021). Putting the cat before the wildlife: Exploring cat owners’ beliefs about cat containment as predictors of owner behavior. Conservation Science and Practice, 3(10), e502. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.502

- van Herwijnen, I. R. (2020). Dog-directed parenting styles [Doctoral dissertation]. Wageningen University. WUR eDepot. https://edepot.wur.nl/521648

- van Herwijnen, I. R., van Der Borg, J. A. M., Naguib, M., & Beerda, B. (2018). The existence of parenting styles in the owner–dog relationship. PLoS ONE, 13(2), e0193471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193471

- van Herwijnen, I. R., van der Borg, J. A. M., Naguib, M., & Beerda, B. (2020). Dog-directed parenting styles mirror dog owners’ orientations toward animals. Anthrozoös, 33(6), 759–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2020.1824657

- Vincenten, J. A., Sector, M. J., Rogmans, W., & Bouter, L. (2005). Parents’ perceptions, attitudes and behaviours towards child safety: A study in 14 European countries. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 12(3), 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457300500136557

- Wadiwel, D. J. (2015). The war against animals. Brill.

- Walby, K., & Doyle, A. (2009). “Their risks are my risks”: On shared risk epistemologies, including altruistic fear for companion animals. Sociological Research Online, 14(4), 8–18. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1975

- Wald, D. M., Jacobson, S. K., & Levy, J. K. (2013). Outdoor cats: Identifying differences between stakeholder beliefs, perceived impacts, risk and management. Biological Conservation, 167, 414–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.07.034

- Wald, D. M., & Peterson, A. L. (2020). Cats and conservationists: The debate over who owns the outdoors. Purdue University Press.

- Walsh, F. (2009). Human–animal bonds II: The role of pets in family systems and family therapy. Family Process, 48(4), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01297.x

- Wilson, J. L., Gruffydd-Jones, T. J., & Murray, J. K. (2017). Risk factors for road traffic accidents in cats up to age 12 months that were registered between 2010 and 2013 with the UK pet cat cohort (“Bristol Cats”). Veterinary Record, 180(8), 195. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.103859

- Yeates, J., & Savulescu, J. (2017). Companion animal ethics: A special area of moral theory and practice? Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 20(2), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-016-9778-6