ABSTRACT

This article presents an ongoing research project, which researches theatre as a school subject at high school level in Sweden. The study is an example of practice-based research on teaching and learning and uses the model learning study for its research approach. It is argued that knowledge concerning the meaning of knowing the object of learning, in this case “to impose one´s will”, is generated using the model. The results are presented as three categories of description and in an outcome space. The categories describe different ways of knowing the object of learning, in this case how to impose one´s will (what the character wants) with the purpose of developing the capability to consciously communicate with an audience.

Introduction

In 2017 the Swedish government decided to allocate extra funding to practice-based research on teaching and learning. The argument was that too little of the research produced at universities reached and made a difference to the actual classroom and the teaching situation. The funding is intended to support research originating from the questions and challenges which teachers encounter on a daily basis, i.e. research emerging from teaching activities. There is an emphasis on intercommunion between the universities and the municipalities in order to make the projects long-lasting. The first funding was described as “experimentation”, but the ambition was to make it permanent and to spread the different interaction models that were tried out. This article describes one such interaction model.

Four universities were selected and received funding. At the four universities the process of allocating funds was handled in different ways. At the University of Gothenburg there was a process of allowing researchers to come in with a research idea. Out of 100 described projects 20 were then selected and we were asked to write an extended project description in the winter of 2018. Our project was one out of eight that was selected in a peer-review process. One core criterion was that there were schools and teachers involved in the projects and that the schools agreed to support the involved teachers to do the research. The project involves two different upper secondary schools within the area of Gothenburg, Sweden. One team of teachers in theatre and one in dance are involved in the project. The project started in autumn 2018 and will end in spring 2021. This article focuses on theatre as teaching practice, presents the methodological and theoretical basis for the project, and discusses the results.

Theater and dance as school subjects

In Sweden, theatre and dance are artistic subjects at upper secondary school level. Theater and dance are two of the specializations of the national arts program, which also includes image and design, esthetics and media as well as music. It is a preparatory program; preparing students to continue either artistic or academic studies. Theater has been a school subject in the upper secondary school’s national arts program in Sweden since 1992 and it has its own syllabus and grading criteria. Students generally start upper secondary school when they are 16, and the national program runs for three years. To meet the school’s requirements for planning teaching activities (sometimes also with colleagues), as well as assessing and giving feedback to students, theatre knowledge needs to be articulated. Theater knowledge, being part of a practical knowledge field, is not always easy to verbalize (c.f. Ahlstrand Citation2014; Carlgren Citation2015; Carlgren et al. Citation2015). Previous research has problematized teachers’ difficulties in verbalizing and articulating their grounds for assessment (c.f. Ahlstrand Citation2014, Citation2018, Citation2020; Andersson Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Andersson and Ferm Thorgersen Citation2015; Zandén Citation2010, Citation2016; Zandén and Ferm Thorgersen Citation2015).

Curriculum reforms and the concept of knowledge

The previous two curriculum reforms in Sweden have developed competency-based syllabi. Since 2011, subject-specific capabilities have been emphasized, where developing certain ways of knowing is underlined. Teaching is described as something that aims to develop subject-specific capabilities. In the Swedish curriculum, there is a clear emphasis on broadening the concept of knowledge to incorporate different forms: facts, understanding, skills and performing abilities. This opens up the possibility for teachers to recognize and value knowledge that is mainly expressed in a practical form, for example in theatre and dance. Knowledge can therefore be represented in different ways and students learn in different ways according to their previous experience (cf. Eisner Citation1996, Citation2007). This does not mean that all knowledge is easy to verbalize or even recognize, since there is also the question of tacit knowledge to be considered (Polanyi Citation[1958] 1998, Citation[1967] 2009; Schön Citation1983; Wittgenstein Citation[1953] 1992). It is only by engaging with the tacit dimension of knowledge that we can better develop our understanding of what such knowing actually consists of (c.f. Ahlstrand Citation2014; Carlgren Citation2020; Carlgren et al. Citation2015; Carlgren and Nyberg Citation2015). Considering the notion of tacit knowledge can be a way to understand the formation of theatre knowledge and how it can be researched in order to develop a subject-specific language.

Overall aim and research question

The overall aim of the project is to formulate qualitative aspects of knowledge expressed in a practical form in both dance and theatre. This can serve as teaching support in the planning of teaching and as a consequence of assessment. In this way, the project also aims to strengthen the scientific foundation in Swedish dance and theatre teacher education and to contribute to results in an area that, through previous research, has proved to be challenging. In this article we will present the results from the theatre part of the study with the research question:

How can qualitative aspects of delimited subject-specific theatre knowledge, namely to impose one´s will, be articulated?

Methodology, methods and material

In this research project, the learning study (Pang and Marton Citation2003) is used as a research approach. In a learning study, a group of teachers and researchers collaborate. In this case are three teachers and two researchers involved. The team develops research lessons in a cyclical process of planning. That means the lessons are tried out, filmed, analyzed and then revised. The research lessons are evaluated and revised from two to four times, in this case we worked on three research lessons, implemented during October (2019) to January (2020). In between the research lessons the filmed material was analyzed and the lesson revised.

The teachers and researchers choose together an object of learning, which is a defined area of the subject. The object of learning consists of the content, and the capability this specific content is supposed to develop. A learning study starts by defining a problem that the teacher team has encountered in their teaching practice. It is formulated as something that either the teacher team finds difficult to teach or as something that the students have difficulties understanding, or in this case acting out. A pretest is designed in order to ascertain the level of knowledge of the students in this particular area. In this case the pretest was a short improvisational exercise (1–2 minutes) where the students worked two and two. Each couple had one book and the assignment was introduced by the teacher: “You want the book. Both of you want the book. What do you do to get it?”Footnote1 The pretest was filmed on the 17th of September 2019. 24 students from high school level (17–18 years of age) were involved in the project.

The findings from the pretest are then used as a starting point to design the research lesson with the help of variation theory (Lo and Marton Citation2012). The research lessons are then applied, tried out, and revised. “This research is for, not on, teachers, i.e., research into problems and challenges faced by teachers in their professional practice” (Carlgren Citation2019, 18).

The problem that the teacher team formulated as the starting point in the theatre part of the project is relates to how the students often “play (act out) the feelings” instead of “being in the situation”. The object of learning is formulated in Swedish as “att kunna driva sin vilja” which concerns the acting method in line with Stanislavski’s “system”; action and objectives.

One of the most important creative principles is that an actor’s tasks must always be able to coax his feelings, will and intelligence, so that they become part of him, since only they have creative power (Stanislavski and Popper Citation1983, 138).

The object of learning concerns how to affect the fellow actor and how to showFootnote2 what the characters in the scene want (in the specific situation), and is formulated as how to impose one´s will (what the character wants). There is a problem, embedded in the ‘given circumstances’of a theatre scene, that the character needs to solve. It can often be framed as a question: ‘What do I need to make the other person do?’ or ‘What do I want?’ In the quotation above from Stanislavski we have marked will in bold. It is common to use the Swedish expression ‘att kunna driva sin vilja’ in a theatre classroom. We speculate that ‘impose one´s will’ is not much used as an expression in English-speaking countries. It deals with what in the Stanislavski system is described as ‘inner action’ and ‘inner motives to justify action’.

In the process of studying the object of learning, knowledge concerning the capability consciously communicate with an audience within the subject of theatre is developed. The capability consciously communicate with an audience is central in the Swedish theatre syllabus (Skolverket Citation2011).

The learning study model aims at generating knowledge concerning the meaning of knowing the object of learning, that is, knowing what there is to be known (c.f. Carlgren Citation2019; Carlgren et al. Citation2015). According to Kullberg, Mårtensson, and Runesson (Citation2016) “learning objectives are general in character, whereas an object of learning is specific to a certain group of learners” (Kullberg, Mårtensson, and Runesson Citation2016, 310). The same authors stress the point that the object of learning cannot be entirely known in advance. What is to be learned depends on the learners as well as on the content taught. In the syllabi of 2011, skills and subject matter are described, but what it means to develop a specific skill or to know a special content area remains silent and implicit and is not clearly stated (Carlgren et al. Citation2015). The object of learning can be studied in order to gain knowledge about the nature of specific capabilities.

We use the data (audio- and filmed material) from the learning study to describe and analyze the object of learning per se. The purpose of the analysis is to categorize and describe the different ways of knowing the object of learning, and to identify qualitative aspects of a subject-specific knowledge.Footnote3 During the learning study process, parts of the video material were analyzed collaboratively by the researchers and the teachers. Three theatre teachers were engaged in the project while one teacher had more time and implemented the three commonly planned research lessons. In the original learning study model, the group of teachers and researchers design a joint lesson and then names one of the participants to teach the jointly planned lesson. A new teacher is then selected to teach the revised lesson two and three. Both the filmed and audio material from the teachers’ planning of the research lesson and the three conducted research lessons were transcribed and analyzed. The transcriptions consists of both verbal articulations and physical actions. The students’ different ways of knowing are expressed as physical expressions and also in the verbal reflections during the research lessons. By ‘physical expressions’ we refer to speech, movement, gaze etc.

Analyses – phenomenography

Phenomenography emerged from empirical studies of learning in the early 1970s, and is mainly based on interviews. In phenomenography, qualitatively different ways of experiencing a phenomenon are analyzed and the results of this analysis form categories of description (Marton Citation1981, Citation1994, Citation2014; Marton and Pong Citation2005). By comparing the differences between expressions concerning a certain phenomenon, qualitatively different ways of experiencing the phenomenon can be distinguished. The units of analysis are ways of experiencing which cover linguistic as well as non-linguistic aspects. We analyze and categorize filmed material through different physical expressions in relation to the object of learning. By analyzing differences between ways of experiencing, the categories of descriptions can be constructed, described and related to each other in a so-called outcome space. Ways of experiencing are considered as correlating with ways of knowing (Carlgren et al. Citation2015).

Phenomenography looks for the meaning of something (in this case experiencing and knowing the object of learning) rather than trying to explain what something is. In the classroom there are a limited number of ways of experiencing a phenomenon, which in turn means that it is possible to separate one way of experiencing from another. It is the description of how a phenomenon is experienced by people in a variety of different ways, which, through the analysis, forms categories of description. In the research that we discuss in this text we found this approach to phenomenography very useful as it also involves the bodily, tacit dimensions of the object of learning. Since the analysis process engages and addresses filmed material it is possible to shift focus from describing what someone says about a phenomenon to describing how the phenomenon is expressed in and through the body. Here, practical and physical knowledge can be recognized. Therefore, one can, through phenomenographic analysis, describe different ways of knowing. More complex ways of knowing are characterized by the simultaneous discernment of increasingly differentiated aspects of a phenomenon (Lo Citation2012; Marton and Lo Citation2007) and it is in this way that one can approach the meaning of knowing the object of learning.

Results

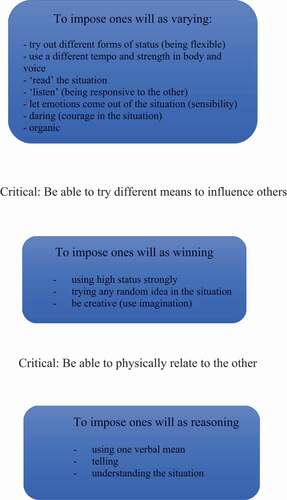

The results are presented as three categories of description and in an outcome space. The categories describe different ways of knowing the object of learning, in this case how to impose one´s will (what the character wants) with the purpose of developing the capability to consciously communicate with an audience. As mentioned earlier, ways of experiencing are considered as correlating with ways of knowing (Carlgren et al. Citation2015). By analyzing differences between ways of knowing, the categories of descriptions can be constructed, described and related to each other in a so-called outcome space. These ways of knowing form the hierarchy in the outcome space where more complex ways of knowing are characterized by the simultaneous discernment of increasingly differentiated aspects of an object of learning. The most complex way of knowing is presented in the highest category (corresponding to the third category). These aspects of this particular object of learning form the answer to this project´s research question. Due to limited space, we use descriptions of “wanting a book” in all three categories, which comes from the empirical material of the pretest. This is used as a typical example which exemplifies similar expressions in the material from all three research lessons.

The first category, which describes how to impose one´s will, is named:

To impose one´s will as reasoning

This first category includes physical expressions where focus is directed toward talking about what one wants. There is a focus on arguing for what one wants, thereby “reasoning”. Verbal expressions are predominant physical actions. In the category, three different qualitative aspects of the object of learning are formulated, namely: using one verbal mean; telling; understanding the situation. Using one verbal mean is a quality in the sense that one mean is used to impose one´s will. But it becomes one-sided when only one mean is used for example during a whole improvisation. This can be exemplified by wanting a book that the other character has and using the same argument continuously (one mean) why one should get the book. The aspect telling is connected to reasoning since gestures are used that indicate something that one wants, for example reaching out a hand in order to try to indicate that one wants the book.Footnote4 Finally, understanding the situation is formulated as the third qualitative aspect in the category. It describes the importance, in an improvisation, of understanding that a library is the setting and that is the reason why my partner is whispering. The aspects form categories of description, in this case the category To impose one´s will as reasoning. Students’ different ways of knowing the object of learning produce knowledge of the meaning of knowing the object of learning.

(2) To impose one´s will as winning

This second category includes physical expressions where focus is directed toward winning in the sense of mastering the situation. In the category three different qualitative aspects of the object of learning are formulated, namely: using high status strongly; trying any random idea in the situation; be creative (use imagination). The first aspect using high status strongly is an effective way to impose one´s will but also becomes one-sided if one character dominates the situation. Using the book example once more, high status can be used to grab the book and then one can use one´s height to keep the book up in the air and in that sense “win” the situation. It is effective to impose one´s will but when put together with the development of the capability to consciously communicate with an audience it does not create an interesting dramatic situation since the scene is quickly over. The second aspect, trying any random idea in the situation, is again an effective way to impose one´s will but the capability to consciously communicate with an audience is not developed. Typical expressions are for example when one person randomly grabs the book while the other one looks in another direction. It is more a spontaneous impulse than a conscious communication. Another example of expressions placed in the category is how a student acts in an extroverted and clichéd manner which is not appropriate to the ongoing situation. Again, it is an effective way to impose one´s will but the capability to consciously communicate with an audience is not improved. The partner in the scene is startled and therefore “loses” but the strategy is not contributing to conscious communication, since the partner has no way to understand what the clichéd character is talking about or acting out. Finally, the third aspect, be creative (use imagination), is an aspect that is a prerequisite for the other qualitative aspects described in this same category. They are descriptions of creative solutions “to win” the situation in the sense of being successful in imposing one´s will, but as has been pointed out the capability to consciously communicate with an audience is not progressed using either of the aspects. One example is when a student putting the book under the sweater saying “It is not a book, I am pregnant”. It is a creative way (using imagination) but at the same time the solution did not fit in with the rest of the improvisation and therefore did not strengthen to consciously communicate with an audience. Once more, the aspects form together different categories of description, in this case the category To impose one´s will as winning. Students’ different ways of knowing the object of learning produce knowledge of the meaning of knowing the object of learning.

(3) To impose one´s will as varying

This third category includes physical expressions where focus is directed toward the other person and the common communication in the situation. In the category, eight different qualitative aspects of the object of learning are formulated namely:

- try out different forms of status (being flexible) - use a different tempo and strength in body and voice - ‘read’ the situation - ‘listen’ (being responsive to the other) - let emotions come out of the situation (sensibility) - daring (courage in the situation) - being organic - create common contactThe first aspect, try out different forms of status, is described as a way to be flexible regarding retrying one´s character´s status in relation to another one. Using the example with the book again, instead of keeping the book in the air the character takes it down and, in that sense, lowers his/her status so the other one can try to grab it. The second aspect use a different tempo and strength in body and voice is a way to vary one’s expressions, for example move faster or slower when lifting the book or, whispering/screaming when trying to get the book from the other character. The third quality, read the situation, is different from the aspect in the first category understand the situation. The expressions that exemplify understand the situation are one-dimensional in that sense that one acts one situation. The aspect read the situation differs in the sense that the character follows the co-character if the situation changes. Sticking to the book example this can be exemplified with another book being introduced by the co-character (an imaginary book) and this book is immediately accepted, and in that way the situation is “read”. As for the fourth aspect listen (being responsive to the other) this is a difference since the focus is toward the other co-actor, not the situation. What is the fellow actor introducing and how can the first character respond to this? For example, one character introduces that the book is a cherished item since it belonged to a dead grandmother. By “listen”, this idea is followed and developed, which contributes to the overall aim: to consciously communicate with an audience. If the idea had been neglected the story would just have stopped without explanation. In this third category, expressions of what is described as the fifth aspect are gathered: let emotions come out of the situation (sensibility) which is a consequence of being able to be in and be sensitive in the situation. Looking at the filmed material of the pretest, one teacher expresses it in the following way:

They give physical expression to their will. They are also fast, energetic, present in the situation. They are not on safe ground where they know what is going to happen but they have thrown themselves into it, ’oh now I do not know how this will go but I know what I want’. Yes, it is strong emotions but I would say … … so I still interpret it as the will is the primary there … then there is a strong outburst, there are strong emotions, this is a lot of energy and it goes a little hand in hand but my interpretation is still that the will comes first.

The problem that the teacher team initially identified with the object of learning, that students played emotions, is “solved” in the third category. As a consequence of being sensitive to the situation, the emotions become an “answer”, not a starting point.

When analyzing the material, the teachers could also identify that the sixth aspect, daring was a qualitative aspect. This has to do with courage in the situation, to “be open” and not least having the courage to wait and “see” what happens. A novice can be eager both to deliver and perform. There are sequences in the empirical material when a pause gives space for the possibility “to vary”, that is, the qualitative aspects presented in the category is given room. The teachers named one qualitative aspect organic and identified it while watching the filmed material. The teachers mention “verb” in the excerpt below. This was part of the teaching in the research lessons, to work with different verbs in order to examine the object of learning. According to the teachers´ analysis when “exhausting” the used verb and changing to another one, the aspect described as organic developed. This is a translated verbatim quote from the transcript of the audio-material:

- But organic …with that word you mean that when it is credible as well? - When is it time to find a new way? - Yes when? - When do I need to find a new verb to influence you? I have to exhaust my first verb I would think. I have to try OK? - Fully… like that - Yes now - To find… - Yes, now I’m trying a new oneThe teachers meant that the acting is “credible” when one is sensitive to when one verb is “acted out” and it is time to change. In an acting situation this can just take seconds.

The eighth qualitative aspect is called create common contact and this is argued to be an extrovert awareness which is vital to develop to consciously communicate with an audience. There is a difference in expressions when a character is only aware of his/her own contact with the audience as if there is also a watchfulness toward the other characters and what we create together. The quote below is from the third research lesson. The teacher has just stopped a scene and speaks to the students working in the scene and the students watching (as the audience), about the importance of being “in contact” with each other as co-actors in a scene. The researcher (R) takes the opportunity to address the students (S 1,2,3):

What do you think (teacher’s name) means by contact? (the researcher addresses the students who are sitting in the audience)

The contact to the audience, I believe

… or the contact to …

… the contact with one´s character and co-actor

(nods) Yes

And how did you see it exist if you thought it existed?

It feels like the focus or something like that … what (student name) says is directed at (student name) even though she may not always look at her

You wanted to say something too?

I thought more that they talked to each other … because sometimes you get so stuck in remembering everything in the script, it’s easy that you … the thoughts flow away and then the focus also flows away from the co-actor and it did not here

Mm, thanks

The quote is an example of how the qualitative aspects of the object of learning, to impose one´s will, are being articulated. The students can express that “being in contact” has to do with keeping the focus on the co-actor, directing someone even if not looking at someone. This is an aspect that one can pay attention to and which can be rehearsed in a systematic way, namely how does one actually work with keeping the focus in order to keep the contact.

Finally, the aspects form different categories of description, in this case the category To impose one´s will as varying. Again, students’ different ways of knowing the object of learning produce knowledge of the meaning of knowing the object of learning.

The outcome space

As mentioned earlier, through phenomenographic analysis one can describe different ways of knowing. More complex ways of knowing are characterized by the simultaneous discernment of increasingly differentiated aspects of a phenomenon (Lo Citation2012; Marton and Lo Citation2007) and it is in this way that one can approach the meaning of knowing the object of learning. The differences between the categories of description in the outcome space () also reveal what is critical for learning:

Figure 1. Outcome space of the object of learning: To impose one´s will (developing the capability to consciously communicate with an audience.)

[…] teachers should identify the critical features of an object of learning and structure appropriate patterns of variation in order to allow students to discern the critical features to be acquired (Ko Citation2014, 275).

The two critical features involved with the object of learning in this study were identified as:

Be able to try different means to influence others

Be able to physically relate to the other

These features were the starting point for planning the research lesson (which will be described in other articles due to space limitations here). As for the one critical feature: “Be able to physically relate to the other” the first research lesson was planned to give the students the opportunity to relate more physically with each other since the analyses indicated that the expressions had more the disposition of telling than showing according to Frost and Yarrow’s definition:

One of the hardest things to grasp is often the difference between ‘showing’ and ‘telling’. ‘Telling’ avoids the full physical involvement of the body. It substitutes codified signs (words, pantomimic gestures) for full body response. An actor can ‘tell’ the audience he is ‘walking through a doorway’ by miming reaching out and turning a door handle and stepping forward (or by saying ’Oh look, here´s a door. I wonder what´s through here). The audience understands what is happening but they won´t believe it. The actor ‘shows’ us the doorway by first imagining the door (creating its reality in his mind) and then changing his whole posture as he steps from one visualised space into another. (Frost and Yarrow Citation2007, 141)

The research lesson gave the students the possibility to become more aware of their own bodies especially in relation to the other character. Working in a systematic way, the research lesson was successful in letting the students move away from expressions that can be described as “telling” and working toward the aspects described in the second (“To impose one´s will by winning”) and the third (“To impose one´s will as varying”) category of description. As previously noted, there are eight qualitative aspects in the highest category (the third category) and three each in the first and second categories.

Discussion

The result answers the research question: “How can qualitative aspects of delimited subject-specific theatre knowledge, namely to impose one´s will, be articulated?” The answer is presented as categories of description and as critical features in the outcome space. We argue that learning study as research approach and phenomenography as analytical model is a feasible way to articulate what is described as “tacit knowledge”.

When a teacher has worked for many years it is not rare or peculiar that the object of learning is taken for granted. This can be understood and explained in terms of tacit dimensions of knowledge. According to Polanyi Citation[1967] 2009) the knowledge has become tacit in embodied meaning. This means that for the teacher the knowledge is incorporated and that the students’ knowings are expressed in ways of seeing, doing and being (c.f. Carlgren et al. Citation2015). The object of learning is in that way taken for granted. The teacher can for example see when something “is working” which is not always easy to verbalize. The knowledge involved in the object of learning is learned by experience and developed in practice. This can be recognized using Wittgenstein’s concept of the language game, according to which the knowledge is developed when one is in a specific practice, in this case a theatre classroom. Language is understood as both verbal and physical. The practice turn of social theory (Schatzki, Knorr Cetina, and von Savigny Citation2001) implies a shift from a representational view of knowledge as an object to a performative view of knowing as constituted in practice.

The question of what, meaning the content, is often neglected or taken for granted. How the content is dealt with and how the teaching practice can be developed are crucial. The phenomenographic analyses make specific what different ways of knowing are involved in the object of learning, and the qualitative aspects and critical features that should be in focus when planning teaching activities. Unpacking the object of learning (c. f. Björkholm Citation2015) can be a way for a teacher team to develop common understandings of qualities in relation to different objects of learning. Usually, a teacher team will have varied knowledge base due to differences in their earlier experiences and education. The model helps the team to discuss and develop a mutually subject-specific language use. One common objection that we hear is that the model takes up a lot of the teacher’s team precious time. We can only refer to what one teacher team pointed out after conducting a learning study. “It takes time to gain time” (Ahlstrand Citation2015). Their common experience was that they gained the time they invested in the project since they had developed tools to both elaborate their teaching and the feedback practice for the future. Additionally, they had also expanded their common understanding in the subject.

Seen from the students´ perspective it is crucial to both the “knowledgeable” and the novice to understand what is successful in acting and/or improvisation and what can be developed. This is fundamental not least in relation to the question of transferring the knowing to new and/or similar situations (Hetland (Citation2007)). Findings of this type may help teachers when planning similar lessons but also when giving assessment and feedback to students. In assessment practice the knowing connected to the object of learning is not so easily articulated (e.g. Carlgren et al. Citation2015). The filmed material can, if used in an ethically sensitive way, be used along with the phenomenographic analyses in an assessment practice where the teacher wants to explain to the student what is supposed to be developed if one wants to reach a higher level of knowing the object of learning. In phenomenography, qualitatively different ways of experiencing a phenomenon are analyzed (Marton Citation1981, Citation1994). Describing the intended knowing in terms of qualities can be a way for teachers to communicate among themselves and students (c.f. Andersson Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Zandén Citation2016; Zandén and Ferm Thorgersen Citation2015).

Studies where school subjects such as mathematics and language are researched are more common in the learning study field. There is a body of research to lean on. Studies where esthetic subjects are researched still need to be developed. This project is one contribution to a growing field where esthetic subjects are studied using learning study (c.f. Ahlstrand Citation2014; Frohagen Citation2016; Wallerstedt Citation2010). More knowledge, for example in relation to other capabilities, is needed. In addition, studies where both younger and older students are involved are needed.

Practice-based and teaching development research

An important point to make which both Carlgren (Citation2019) and Kullberg, Vikström, and Runesson (Citation2019) stress, is that the results from a learning study also produce knowledge, as well as developing the teaching practice. The results from a local learning study can be made practical public knowledge and can be tried out in new classrooms (ibid.). There has been debate about (c.f. Enthoven and de Bruijn Citation2010) whether practitioner research can be recognized as a valid knowledge source that produces knowledge significant beyond a specific context.

There is therefore a need for theorizing the teaching of specific objects of learning – not in terms of applying “grand” theories such as socio-cultural theories of learning or situated cognition but of “small” intermediate theory about how to understand a specific situation. (Carlgren Citation2019, 27)

Carlgren (Citation2019) argues that the learning study model combines a practice-based development of theory with a theory-based development of practice. When designing the research lessons several different teaching methods can be used within the model learning study. It is the teacher team and the researcher who together make decisions on what teaching methods can be used. There can be physical, written or oral exercises. There can be planned teaching activities with improvisation or written text. It all depends on the chosen object of learning. This study´s main purpose is to gain knowledge concerning the object of learning, and in that sense understand the ways of knowing and aspects of a specific capability (c.f. Carlgren Citation2012, Citation2020; Carlgren et al. Citation2015). The research concerns the meaning of knowing a specific capability, in this case the capability to consciously communicate with an audience.

This article has presented the theoretical and methodological underpinnings of a practice-based research project where the aim is to develop knowledge concerning specific objects of learning and subject-specific capabilities. We argue that to be able to develop a teaching practice it is essential to involve the teachers. Another strong argument for working with the learning study model and phenomenographic analyses is based on the perspective on knowledge presented in this paper. Knowledge is seen as a complex matter and it is important to research the significance of the content and how it is treated. In a learning study model both the teacher’s knowledge about the object of learning and the student’s different ways of knowing are considered. Finally, it is argued that phenomenographic analysis is a way to build and develop a knowledge base for theatre knowledge; a knowledge base where the subject-specific treatment of the content is the starting point.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the teachers and students involved in the project.

The authors wishes to thank ‘Anchor English’ for proofreading service.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Filmed material from pretest 09-17-19.

2 C.f. Frost and Yarrow (Citation2007), also under “The outcome space” in this article.

3 The research lessons will be described in other articles, due to space reasons.

4 Again: See Frost and Yarrow´s (Citation2007) definition under “The outcome space”.

References

- Ahlstrand, P. 2014. Att kunna lyssna med kroppen: En studie av gestaltande förmåga inom gymnasieskolans estetiska program, inriktning teater. Stockholm: Institutionen för etnologi, religionshistoria och genusvetenskap, Stockholms universitet.

- Ahlstrand, P. 2015. Learning study i dans. Venue. Linköping: Linköpings universitet, 4 (1): Article 5. doi:https://doi.org/10.3384/venue.2001-788X.1545.

- Ahlstrand, P. 2018. Analysing the object of learning, using phenomenography. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies 7 (3):184–200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLLS-12-2016-0053.

- Ahlstrand, P. 2020. A method called action(re)call. How and why we use it. Ride-The Journal Of Applied Theatre And Performance 25 (4):505–525.

- Andersson, N. 2016a. Teacher’s conceptions of quality in dance education expressed through grade conferences. Journal of Pedagogy 7 (2):11–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/jped-2016-0014.

- Andersson, N. 2016b. Communication and shared understanding of assessment: A phenomenological study of assessment in Swedish upper secondary dance education [Diss.Luleå]. Luleå: Luleå tekniska univ.

- Andersson, N., and C. Ferm Thorgersen. 2015. Bedömning av danskunnande - uttryck, respons och värdering inom ett estetiskt ämne. In Kunskapande i dans: Om estetiskt lärande och kommunikation, red. B.-M. Styrke, 171–187. Stockholm: Liber utbildning.

- Björkholm, E. 2015. Unpacking the object of learning. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies 4 (3):194–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLLS-06-2014-0014.

- Carlgren, I. 2012. The learning study as an approach for ‘clinical’ subject matter didactic research. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies 1 (2):126–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/20468251211224172.

- Carlgren, I. 2015. Kunskapskulturer och undervisningspraktiker. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Carlgren, I. 2019. The knowledge machinery and claims in learning study as paedeutical research. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies 9 (1):18–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLLS-02-2019-0010.

- Carlgren, I. 2020. Powerful knowns and powerful knowings. Journal of Curriculum Studies 52 (3):323–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2020.1717634.

- Carlgren, I., and G. Nyberg. 2015. Från ord till rörelser och dans [Elektronisk resurs] en analys av rörelsekunnandet i en dansuppgift. In Forskning om undervisning och lärande, 24–40. Hämtad från. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:du-17218

- Carlgren, I., P. Ahlstrand, E. Björkholm, and G. Nyberg. 2015. The meaning of knowing what is to be known. Education et Didactique 9 (1):143–160.

- Eisner, E. W. 1996. Cognition and curriculum reconsidered. 2nd ed. London: Paul Chapman.

- Eisner, E. W. 2007. Assessment and evaluation in education and the arts. In International handbook of research in arts education, ed. L. Bresler, 423–26. Amsterdam: Springer.

- Enthoven, M., and E. de Bruijn. 2010. Beyond locality: The creation of public practice based knowledge through practitioner research in professional learning communities and communities of practice. A review of three books on practitioner research and professional communities. Educational Action Research 18 (2):289–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09650791003741822.

- Frohagen, J. 2016. Såga rakt och tillverka uttryck: En studie av hantverkskunnandet i slöjdämnet. Stockholms universitet Humanistiska fakulteten (utgivare). Stockholm: Stockholms universitet.

- Frost, A., and R. Yarrow. 2007. Improvisation in drama. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education.

- Hetland, L., red. 2007. Studio thinking: The real benefits of arts education. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Ko, P. Y. 2014. Learning study – The dual pocess of developing theory and practice. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies 3 (3):272–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLLS-07-2014-0019.

- Kullberg, A., A. Vikström, and U. Runesson. 2019. Mechanisms enabling knowledge production in learning study. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies 9 (1):78–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLLS-11-2018-0084.

- Kullberg, A., P. Mårtensson, and U. Runesson. 2016. What is to be learned? Teachers’ collective inquiry into the object of learning. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 60 (3):309–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2015.1119725.

- Lo, M. L. 2012. Variation theory and the improvement of teaching and learning. Göteborg: Acta universitatis Gothoburgensis.

- Lo, M. L., and F. Marton. 2012. Towards a science of the art of teaching: Using variation theory as a guiding principle of pedagogical design. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies 1 (1):7–22.

- Marton, F. 1981. Phenomenography – Describing the world around us. Instructional Science 10:177–200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00132516.

- Marton, F. 1994. Phenomenography. In The international encyclopedia of education, red. T. Husén, and T. N. Postlethwaite, Vol. 8, 2nd ed., S. 4424–S. 4429. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Marton, F. 2014. Necessary conditions of learning. London: Routledge.

- Marton, F., and M. L. Lo. 2007. Learning from the “learning study”. Journal of Research in Teacher Education 14 (1):31–46.

- Marton, F., and W. Y. Pong. 2005. On the unit of description in phenomenography. Higher Education Research & Development 24 (4):335–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360500284706.

- Pang, M. F., and F. Marton. 2003. Beyond“lesson study”: Comparing two ways of facilitating the grasp of some economic concepts. Instructional Science 31 (3):175–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023280619632.

- Polanyi, M. [1958] 1998. Personal knowledge. Towards a post- critical philosophy. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Polanyi, M. [1967] 2009. The tacit dimension. University of Chicago Press ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Schatzki, T. R., K. Knorr Cetina, and E. von Savigny, eds. 2001. The practice turn in contemporary theory. London: Routledge.

- Schön, D. A. 1983. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Aldershot: Avebury.

- Skolverket. 2011. Läroplaner, ämnen och kurser. Ämne – Teater. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Stanislavski, K. S., and H. I. Popper. 1983. Creating a role. London: Methuen.

- Wallerstedt, C. 2010. Att peka ut det osynliga i rörelse: En didaktisk studie av taktart i musik. Göteborg: Högskolan för scen och musik vid Göteborgs universitet.Serie: ArtMonitor.

- Wittgenstein, L. [1953] 1992. Filosofiska undersökningar. Stockholm: Thales.

- Zandén, O. 2010. Samtal om samspel. Kvalitetsuppfattningar i musiklärares dialoger om ensemblespel på gymnasiet. Göteborg: Högskolan för scen och musik, Konstnärliga fakulteten, Göteborgs universitet.

- Zandén, O. 2016. The birth of a Denkstil: Transformations of music teachers’ conceptions of quality in the face of new grading criteria. Nordisk Musikkpedagogisk Forskning 17:197–225.

- Zandén, O., and C. Ferm Thorgersen. 2015. Teaching for learning or teaching for documentation?: Music teachers’ perspectives on a Swedish curriculum reform. British Journal Of Music Education 32 (1):37–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051714000266.