ABSTRACT

Time and time again, Indigenous people throughout the world are faced with the need to reassert their way of life, and to “buck” political and social systems that continually marginalize their treaty rights. In this article, I explore the role of Indigenous activism at different scales—personal, tribal, and collective—to intervene in key moments to uphold treaty rights and protect Indigenous ways of life. In defending treaty rights, Indigenous peoples have become leaders in the social and environmental justice movement, particularly in relation to climate justice and fishing rights. The article recounts three ethnographies that illustrate how access to rights is wrapped up in geopolitics and the political economy. Highlighting these acts of resilience and leadership in the face of crisis is the central work of this article. The article concludes with a call to fundamentally rethink governance mechanisms and structures, to protect ecological and human health.

Introduction

It is hard to imagine that a simple act of fishing or pulling a canoe could be seen as an act of resistance. Yet time and time again, Indigenous Peoples throughout the world are faced with the need to reassert their way of life, and to “buck” mainstream political and social systems that structurally marginalize their traditional way of life (La Duke Citation1999; Mirosa and Harris Citation2012; Holifield Citation2013; Norman Citation2014; Whyte Citation2016). Given structural injustice of settler-colonial systems, practicing everyday acts of survival—such as fishing—can now be wrapped up in acts of resistance, activism, and even heroism. A central factor in this disconnect is the tension between fixity and mobility (Biolisl Citation2005; Norman, Cook, and Bakker Citation2015). That is, fixed (and policed) jurisdictions established through North American settler-colonial reservation and nation-state systems are in direct opposition to the intricate and reflexive relationships that Indigenous communities have with the natural world (Cajete Citation2000). The very cosmology of Indigenous Peoples is built on the intricate knowledge of and connection to their ancestral land—and all its relations, including its animals, plants, and water (Cajete Citation2000; Grossman, Parker, and Frank Citation2012). Thus, the act of dislocating peoples from their traditional territories and limiting access to their ancestral land and waters has significant impacts on the social, political, economic, and spiritual systems of Indigenous People in North America and throughout the world (Ayana Citation2004; Whyte Citation2016). That said: Indigenous Peoples have a long history of resilience and strategies to overcome hardship, whether the hardships springs from colonialism or from environmental change. In fact, Indigenous People around the world are taking leading roles in important issues like global climate justice and water protection. Highlighting these acts of resilience and leadership in the face of crisis is the central work of this article and of other articles in this issue, such as those of Naiga and Förster et al.

While treaties were established during the settler–colonial times in North America to grant access to traditional hunting and fishing grounds through what is called “usual and accustomed” rights, the onus continues to be placed on Indigenous Peoples to reassert these rights, and to re-remind the United States government (and mainstream society) of treaty trust responsibilities and Indigenous sovereign rights status (Grossman, Parker, and Frank Citation2012; Whyte Citation2015). Perhaps most shocking is the frequency in which these rights are dismissed, challenged, and forgotten, and the ongoing need to reactivate, resist, and re-remind dominant society of these rights—which we are seeing yet again with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and the water protector movement in North Dakota.

The affronts are many and complex. As the cases in this article highlight, the circumstances change—whether wrapped up in geopolitics (post 9/11), political economy and capital accumulation, or the accumulating impacts of global climate change. As such, in this article I explore the role of Indigenous activism at different scales—personal, tribal, and collective—to intervene in key moments to uphold treaty rights and protect Indigenous ways of life, including connections to waterways. I show that as tribes and Indigenous actors take leading roles to uphold treaty rights, Indigenous Peoples have become leaders in the social and environmental justice movement, particularly in relation to climate justice and fishing rights. To illustrate this leadership, I recount three vignettes—or moments in time—when the connection to and protection of the natural world have been challenged through complex geopolitical and economic situations and the subsequent acts of resistance through Indigenous communities demonstrating their leadership capacity to respond to these crises.

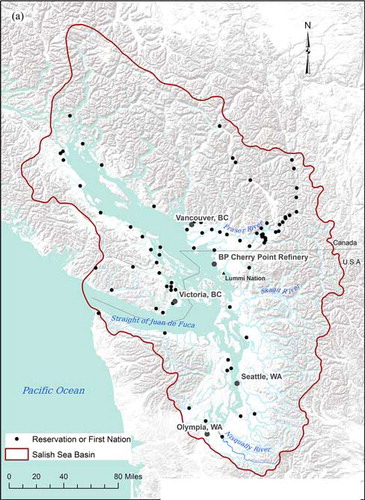

These acts of resistance and political and social activism are happening the world over. However, this work engages the geography with which I am most familiar, the Salish Sea Basin in the coastal Pacific of North American between Canada and the United States (see ).

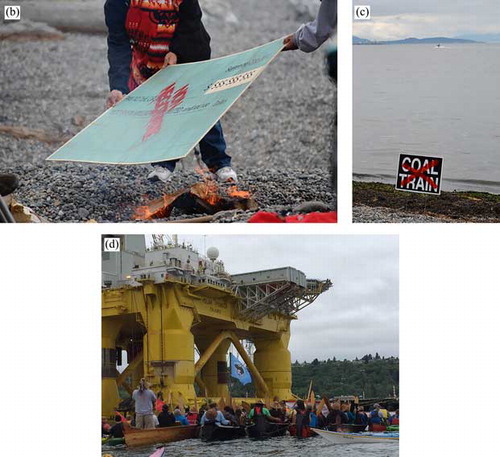

Figure 1. (a) Map of the Salish Sea Basin. (b) Photo of check burning: Lummi Nation Treaty Rights are Not for Sale! (c) Photo of No Coal sign on Cherry Point. (d) ShellNO kayaktivists protesting oil drilling in the Arctic, May 2015.

I use narrative to illustrate the tensions between the fixity of jurisdiction and power dynamics associated with bounding, and the impacts these have on water governance and traditional ways of life. The vignettes, or ethnographies, illustrate how access to rights is wrapped up in geopolitics and the political economy. First, I recount a story shared with me by a Lummi community member, Tyson Oreiro, about how a day of crabbing became wrapped up in geopolitics and jurisdictional tension post 9/11. I then illustrate how challenges to treaty rights continue with proposals to build a large-scale deep-water transport terminal in a traditional fishing area of the Lummi Nation. Lastly, I show how groups are mobilizing to protest fossil fuel extraction and the continued acceleration of global climate change, through defining moments such as the protests of the Polar Pioneer in the waters off of Seattle, WA. I historicize these events by showing how fighting for fishing rights has been ongoing since the signing of the Point Elliot Treaty of 1855. I engage in these complex issues by weaving together Indigenous research methodology, standpoint theory, critical geography, climate justice, and Indigenous activism.

Indigenous Activism and Social, Environmental, and Climate Injustice

A growing body of scholarship has helped to identify the role of Indigenous activism in combatting systemic social, environmental, and climate injustice. This scholarship contributes to a clearer understanding of how structural racism, which is often invisible in mainstream society and governments, severely impacts marginalized groups and Indigenous peoples. For example, the works of Darren Ranco, Kyle Powl Whyte, Roxanne Ornelas, Daniel Wildcat, Zoltan Grossman, Ryan Holifield, Noriko Ishiyama, and Beth Rose Middleton (among others) all provide important contributions to advocating for Indigenous rights in a wide range of disciplines, including geography, environmental justice, Indigenous studies, political ecology, and philosophy.

Middleton’s (Citation2011) scholarship, for example, engages in a wide range of topics related to Indigenous environmental justice, intergenerational trauma and healing, and Indigenous Peoples’ roles in climate change discourse. Most recently, her work in re-envisioning land conservancies through an Indigenous lens provides important insights on how strategic partnerships can help protect access to culturally significant lands and waterways—topics emerging in the Salish Sea.

Similarly, scholars such as Whyte, Wildcat, Grossman, and Parker provide important contributions related to climate justice and Indigenous peoples. Grossman, Parker, and Frank (Citation2012) show how Indigenous Nations are asserting their resilience through strategic alliance building, using powerful testimony, and intervening in key public moments. Whyte powerfully situates the impacts of global climate change at a personal level. As a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, he skillfully grounds the impacts of global climate change to specific harvesting and cultural practices that significantly impact his community. He refers to climate injustice as another iteration of the impacts of colonization—referring to the current environmental injustices as colonial déjà vu (Whyte Citation2015). Similarly, works by Ornelas help to push disciplinary boundaries by focusing on the geographies of Indigenous peoples with an emphasis on the protection of sacred lands and waters, role of Indigenous women in environmental activism, leadership, environmental justice, and human rights (Ornelas Citation2011; Citation2014).

Scholars of Native American Studies and Native Environmental Law, such as Ranco and Suagee (Citation2007), have helped draw the connections between tribal environmental sovereignty and due process in the context of environmental regulation. Linking self-regulation, self-determination, and tribal sovereignty is an important strategy to combat structural racism and environmental and social injustices that put tribes in a position to continually defend or hold the line on treaty rights. This work builds on the prolific scholarship of public land law, water law, and Federal Indian law by legal scholar and Native rights activist Wilkinson (Citation2006), and on Ishiyama’s (Citation2003) important contribution to Antipode, which explicitly link environmental justice and tribal sovereignty.

Geographers such as Holifield (Citation2013) build on the environmental law scholarship by locating the tension between Indigenous knowledge systems and mainstream science, and data, and how this influences regulatory agencies. Thus, at its foundation, mainstream regulatory agencies are excluding certain foundational belief systems that are central to Indigenous communities. Regulation is wrapped up in power dynamics and dominant narratives that are largely invisible to the mainstream agencies and public. This conflict, as Taylor and Sonnefield describe in the introduction to this special issue, relates to asymmetrical power exercised by social actors. Similarly, Naiga and Förster et al. (this issue) show how these power imbalances are materialized as social injustices in different geographies and across different waterscapes.

The scholarship around Indigenous activism differs from other scholarship related to activism, environmental justice, and race, largely because of the unifying theme of deep and sustained connection to place and the role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Native Science. Other genres, such as environmental history and critical geography, helped to provide counternarratives to mainstream discourse related to the colonial-settler experience and the impacts on Indigenous Peoples and the natural world. For example, Taylor (Citation1999) and Evenden (Citation2004) provide important contributions to the environmental history of First Peoples, water, and fisheries in the Salish Sea Basin.

Decolonizing Research Methods and the Politics of Positionality

My methodology is part of a standpoint-theory approach, which utilizes narrative form to participate in a decolonizing research methodology and pedagogy. I am inspired and informed by Indigenous knowledges and theories—particularly drawing on the work of Cajete (Citation2000), Wilson (Citation2009), Kovach (Citation2010), and Smith (Citation2012), who strive to include research practices as part of wider projects of decolonization. Each of these scholars shows how inserting Indigenous Ways of Knowing into research practices can help identify alternative and multiple ways of seeing problems and identifying solutions. For me, these insights translate into a deep appreciation for place and an understanding of the relationships between humans and their environment over a sustained period of time.

Overall, my methodology employs a triangulation approach, where I employ ethnography, storytelling, and participant observation, in conjunction with analyzing primary and secondary sources. Additionally, following Indigenous research methodology (Smith Citation2012), self-location is also used as a guiding framework.

In many scientific traditions, objectivity is fiercely defended. Like many other scholars (particularly those involved in the feminist tradition, Indigenous research, and critical geography), I view this objectivity as an illusion. Although one can—and should—strive to enter into work in an unbiased fashion, positioning oneself within one’s work provides transparency, which is particularly salient when one is working with issues surrounding power and justice.

Certainly, my positionality (i.e., as a researcher trained at the University of British Columbia, my role as a faculty member at Northwest Indian College, and my roles as mother, partner, sister, daughter, colleague, teacher, and friend) influences my dealings with people in the field. For example, my role in the Native Environmental Science Department introduced me to several Indigenous leaders who have generously provided comments and insight into this long-term project. In addition, the many hours of conversations with students, colleagues, and friends throughout Northwest Indian College and the Salish Sea Basin, in general, have helped me to see border politics through a more informed, nuanced, and critical lens.

A key consideration as I enter into my research is how (and whether) my work contributes to wider goals in the communities within which I work. In this case, disrupting a dominant narrative and locating power dynamics comprise an important contribution that, in the end, serves wider goals of Indigenous self-determination and, ultimately, healthier and more resilient cultures and ecosystems. The cases that follow help illustrate the ongoing work towards these goals.

Situating the Geopolitical Landscape of the Salish Sea—The Promised Rights of the Coast Salish Peoples—Exercising Treaty Rights at Risk

For Coast Salish communities of the Salish Sea, fishing is not just for economic gain or sustenance; it is a fundamental way of life integral to cultural identity. Access to First Foods such as salmon, crab, and shellfish, as well as waterfowl and edible plants, is central to maintaining this way of life. During precolonial times, the rich ecosystem provided all of the needs of the Coast Salish peoples. In fact, oral accounts speak of salmon runs so large that water was no longer visible—only the backs of the silvery salmon were visible as the salmon migrated upstream by the millions (Nugent Citation1982).

Post-contact, however, Coast Salish communities, like Indigenous communities around the world, have experienced tremendous affronts to their natural world and social–political–cultural structures. These compromises have come in various forms: land disposition, physical acts of violence, forced assimilation through boarding schools, outlawing of cultural events such as potlatch and other cultural practices, and degraded or decimated ecosystems (Whyte Citation2015).

The physical act of dispossessing land continues to have huge impacts on Indigenous communities, given the important role connections to and relationships with ancestral lands and waters have in maintaining a traditional way of life. Fragmenting communities through colonial bounding and displacing people from traditional territory onto small parcels of lands—reserves in Canada and reservations in the United States—had and continues to have severe impacts on Indigenous cultures (Miller Citation1997; Citation2006).

The signing of the Point Elliot Treaty on January 12, 1855, between U.S. Governor Isaac Stevens and Coast Salish tribal leaders marked a new relationship between the U.S. government and the coastal Pacific Tribes. The treaty acknowledges the Lummi Nation (and the other signatories) as an independent and self-governing people, whose traditional homelands extend throughout the Salish Sea, north into the Fraser River (in what is now British Columbia, Canada) and south into the neighborhoods of Seattle, WA.

The treaty established reservations and access rights to usual and accustomed areas for tribal communities throughout the U.S. side of the Coast Salish territory, and these were upheld through the Boldt decision (United States v. Washington Citation1974). The usual and accustomed territory is an important aspect of the Point Elliot Treaty, because it indicates the priority that the Coast Salish peoples have in maintaining a fishing tradition. It shows that fishing is not just about food or economy. Rather, fishing is a way of life and integral to cultural self-identity. These priorities are reflected in the treaty itself. Article 1 ceded the majority of the Coast Salish traditional territory to the settler community; Article 2 established “reserves” or reservations; and Article 5 established usual and accustomed fishing rights. Article 5 of the Point Elliot Treaty states:

The right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary houses for the purpose of curing, together with the privilege of hunting and gathering roots and berries on open and unclaimed lands. (Governor’s Office of Indian Affairs [GOIA] Citation2015)

The priority of the coastal tribes to maintain a fishing tradition is indicated both by the location of the reservations, which are often at the mouth of rivers or other significant hunting grounds, and by their decision to prioritize access to these waters over larger land mass. Undoubtedly, the tribes were burdened with a difficult decision in 1855, when faced with the signing of the Point Elliot Treaty. Certainly, the decision was made in a time of duress, as populations were weakened by disease and other techniques of cultural genocide (Harris Citation2002; Thrush Citation2008). In fact, some tribes—including Nisqually—even question whether the “x” marking the tribal representative was even valid; oral histories indicate that, in fact, it was Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens who signed the “x” for the tribal representative (Wilkinson Citation2006). Despite the untenable circumstances that clouded the Point Elliot Treaty, it is important to stress the incredible resilience of the Coast Salish tribes and the foresight of the leaders when negotiating the treaty terms. The significance of Article 5 of the treaty, in maintaining fishing rights in traditional territory, is not to be underestimated. Essentially, the tribes relinquished millions of acres of land for the right to maintain access to fishing and hunting grounds, demonstrating what was—and remains—a priority for tribes. Yet fragmented governance systems (federal, state, tribal, county, city, citizen, etc.) and dominant narratives continually place the burden of maintaining these rights on the tribes themselves.

A key point is that with the signing of the treaties, the United States promised to uphold the treaty trust responsibilities. However, historically, the U.S. government has a spotty record in upholding the treaty trust responsibility. Only in recent years has federal leadership taken this responsibility more seriously. Time after time, the onus has been placed on tribes to reassert and actively defend these rights (which, it should be noted, are historically inherent rather than acquired rights).

In Washington state, the need to assert these rights grew significantly after World War II, when the economic gains made through commercial fishing and the industrializing of canneries led the state of Washington to, essentially, turn its back on the treaty and Indigenous fishing rights. The conflict came to a head during what is known as the “fishing wars” in the 1960s, when traditional fishing areas became racialized spaces and areas of violence. The fishing wars involved events when Indigenous People were harassed, beaten, and arrested for fishing in their own territory (Taylor Citation1999). During this infamous era, it was not uncommon for Indigenous People to face gunfire while they were trying to fish (Wilkinson Citation2006).

During this era, Indigenous fisherpeople had to fight for the right to fish in their traditional territories. The 6-mile bank of the Nisqually River known as Frank’s Landing became the center of this controversy, as state game wardens consistently targeted fishermen. It took acts of civil disobedience and “fish-ins” led by famed Indigenous rights activists Billy Frank, Jr., and Hank Adams and high-profile allies—including Hollywood actors such as Marlon Brando—to help raise public consciousness and ignite a public conversation regarding maintaining tribal sovereignty. The violence became so heated that Hank Adams himself was shot in the stomach while protesting on the banks of the Nisqually River (Wilkinson Citation2006). The high-profile protests and escalating violence ultimately led the courts to intervene.

The fishing rights to usual and accustomed areas were upheld in 1974, in the historic legal case, when U.S. District Judge George Boldt interpreted “in common with” to mean “sharing equally the opportunity to take fish” between treaty and nontreaty fisherpeople (United States v. Washington Citation1974). A central aspect of the Boldt decision in the context of the Lummi Nation is not only the fixed allocation, but also the right of the tribes to manage their share (Boxberger Citation1989), which led to the development of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission.

However, as Terry Williams, a Tulalip Tribal member and policy representative of the Tulalip Natural Resources, often says, “The Boldt decision means nothing, if we have no fish—fifty percent of nothing is nothing.” The affronts to the fish are many—habitat loss, upland deforestation, increased siltation in rivers, over-harvesting, invasive predators, and blocked passage through dam constructions. Salmon, crab, and shellfish numbers have declined drastically through multiple affronts: upstream degradation, deforestation, siltation, overharvesting, commercial fishing, and now—the latest affront—warmed waters through global climate change.

Global climate change is having severe consequences on fish reproduction. The increased warming of rivers and the subsequent ocean acidification process are impacting the survival rates of salmon eggs and juvenile salmon. The range of temperatures for salmon fry to survive is very small. In general, salmon eggs need river temperatures 56°F or lower to survive. The increased temperatures associated with global climate change include river temperatures reaching 60°F and higher in many Pacific Northwest river systems. This is impacting not only the salmon runs—it also has impacts on the entire marine ecosystem, including shellfish and sea star decline. Even the iconic (and culturally significant) orca whales, which rely on the salmon for survival, are compromised. The southern resident pods in the waters around San Juan Island, for example, are starving to death. Since 2010, they have been listed as endangered species, and the numbers have reached a dangerously low 70.

Although the Boldt decision reaffirmed the need for state governments to uphold treaty rights, Indigenous Peoples are still in the position of necessarily fighting for their treaty rights. Examples of the ongoing need to maintain/assert treaty rights include the Makah whale hunt off of the Olympic Peninsula (Cote Citation2010) and the right to fish in traditional (usual and accustomed) waters. It is the disruption, and subsequent assertion, of these rights that I describe in the next three sections—through the politics of fear produced through 9/11, the proposed shipping terminal, and the ongoing threats of environmental degradation and global climate change.

The Line in the Sea: Traditional Fishing Practices and Geopolitics Post 9/11

It was a perfect day to go crabbing. The skies were blue and the water was calm. Tyson, a young man from a long line of fisherpeople from the Coast Salish Lummi Tribe, prepared for a day on the water as generations before him had done. In the early morning calm, he made his way to one of his favorite crabbing spots in the traditional territory of his people. He prepared his gear and dropped his pots, waiting for the bounty of the sea to provide for him and his family. For many Indigenous tribes of the Coastal Pacific, it is widely known that people do not go after food (such as fish or crab); rather, food comes to them. The work that they do (and their ancestors before them have done) to protect the waters and the habitat is part of a form of reciprocity—where the sea provides for you, if you protect and care for the environment. This reciprocity (in addition to the intricate knowledge of the geography and marine environment) has worked for thousands of years, as bountiful salmon runs filled rivers in ways that are now hard to fathom.

The declining numbers, however, are not stopping the cultural traditions, nor did it stop Tyson from going crabbing that morning, 15 years ago. He went crabbing for no other reason than that, as a Lummi community member, harvesting from the sea is part of his way of life. The calm that morning provided time for reflection—time to reconnect with the waters and his ancestral home. It was time for the daily troubles to wash away and to be in the moment.

The moment was abruptly disrupted, however, when a screeching speedboat—U.S. Department of Homeland Security—approached the small fishing boat. The authorities had mounted a 50-calibre machine gun, manned and pointed directly at Tyson’s boat. Screaming over the loud motor, the officers ordered Tyson to leave the area immediately or be fired upon and considered a threat to national security.

When the Homeland Security boat approached, Tyson was in the same place that he—and his ancestors before him—had always crabbed. But in a post 9/11 era, this sacred space became wrapped up in wider geopolitics of fear. It became a place of heightened interest for those in charge of securing the nations peripheries and “at risk targets,” such as the oil refinery that was built at Cherry Point (on Lummi traditional territory). This heightened security meant that the traditional waters that his community had occupied for thousands of years now became—unexpectedly—“illegal” to access. This very peaceful moment quickly turned to one of violent affront as Tyson was told to leave in no uncertain terms or face violent action. Tyson explained to the officers that he was a member of the Lummi Nation, and that he had both inherent and acquired treaty rights to fish in his ancestral land. However, in the months and years following the 9/11 tragedy, the heightened sense of “security” and “defense” made the defensible lines even more pronounced and the areas that characterized “security risks” became intertwined with national interests.

In this case, the “invisible” line that was drawn in the waters was based on how close the Office of Homeland Security (located on the opposite side of the country of the waters in question) deemed as being too close to areas that are in “high risk” of security breach. This tradition of fishing in sacred, ancestral waters was thereby launched into a geopolitics nexus that is interwoven with narratives of terrorism and fear. In this case, the extended lines of proximity to oil refineries—which were deemed as a high risk for terrorist activity—had direct and immediate impacts on very local, ancestral waters for Indigenous Peoples who have been fishing since time immemorial. Although Tyson, under pressure, retreated that day, Lummi Nation’s work to advocate for inherent and acquired treaty rights continues. This work is part of an ongoing responsibility to protect the waters for the next generations and to protect the right to engage in cultural practices and ways of life that are guaranteed through treaty trust responsibilities.

Treaty Rights are Not for Sale! Protecting Xwe’chieXen, Upholding Treaty, and Maintaining a Way of Life

Fifteen years after the Homeland Security incident and the tightened security associated with 9/11, fishing rights in the Salish Sea were threatened once again. This time, it came through a proposal to build what would have been the largest deep-water marine terminal in the United States, on Lummi’s ancestral territory, Xwe’chieXen (Cherry Point). The threat, once again, put Coast Salish tribes in the position to defend their way of life and their treaty rights.

The Gateway Pacific Terminal was designed to export up to 54 million dry metric tons per year of bulk commodities, mostly coal. The construction of the terminal raised significant concern for the Lummi Nation. The construction would not only harm the immediate fishing and spawning grounds at the pier, but it would also result in increased shipping traffic and risks of tanker spills; this would also contribute to the global fossil fuel economy and subsequent global climate change. In addition, the construction of the marina is on sacred ancestral territory of the Lummi People, which falls north of the reservation. Given the negative impacts on fishing rights, constructing the terminal would have been a violation of the usual and accustomed fishing rights outlined in Article 5 of the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliot and reaffirmed through the Boldt decision. More poignantly, it would impact a traditional way of life.

Lummi Nation’s position against the terminal was launched onto the national stage, on September 21, 2012, when dozens of Coast Salish community members gathered on the shores of Xwe’chieXen to protest the development of the proposed terminal. The Lummi leaders and their Coast Salish relatives gathered in solidarity against what was yet another affront on their traditional territory and sacred fishing grounds. In the backdrop were the crystal blue waters of the Salish Sea, glistening with the autumn sun, spotted with “No coal” signs on the beach. The speakers, wrapped in Pendleton blankets and wearing cedar hats, spoke powerfully about the ongoing need to protect sacred lands and the home of their ancestors, and to protect their home for future generations.

After the elders shared their words, a pivotal moment occurred when Lummi Nation Councilman Jay Julius held up a poster-sized proxy check—made out to Lummi Nation for a million dollars—with the words “NON-NEGOTIABLE” stamped across it. Jay took the check, held it high for the public to see, and then in a powerful gesture, placed it on an open fire, letting it burn to ashes in front of the crowd. This moment came to symbolize Lummi’s position, which had the ongoing message: “Our Treaty rights are not for sale!”

By design, the protest occurred before the board meeting of one of the biggest financial bankers of the SSA Marine project. When news of the protest hit the pages of New York Times on October 11, 2012, coupled with a powerful testimony by Councilman Julius at the annual board meeting, the New York financier quietly backed out of the deal, starting a slow decline in the terminal project. This event marked one of many strategic moves that Lummi Nation conceived to block the development of the terminal (see and ).

The Gateway Pacific Terminal was originally presented to the Lummi Nation and local citizens as an economic development plan to build jobs and grow tax bases. SSA Marine Executive Director Bob Watters maintained that the “Gateway Pacific Terminal and tribal interest can be harmonized if good faith discussions can take place.” However, the Lummi Nation disagreed with this perspective and took a firm stand against the terminal. The chairman of the Lummi Indian Business Council, Timothy Ballew II, and his predecessor, Cliff Cultee, maintained that the shipping terminal would violate the terms of the Point Elliot Treaty, and would impact the Lummi People’s ability to maintain their sovereign right to participate in the act of fishing—which is at the center of Lummi cultural identity. This was directly linked to maintaining and fostering a healthy ecosystem, which would provide for the return of the sacred salmon.

The proposed construction of the shipping terminal was also opposed by environmental, citizen, and faith-based groups in the neighboring town of Bellingham, WA. The groups largely rallied against the project because of the wider implications for the contribution to global climate change. Launching a “power past coal” campaign, the groups became an educational platform for wider environmental issues. Although the local groups had a unified and strong voice, they did not have the political clout to stop the project. It was Lummi Nation’s sovereign status and the treaty trust responsibilities for which the federal government had to account that ultimately made the difference.

The battle to protect Cherry Point ended on May 9, 2016. In the crowded chambers room of the Lummi Indian Business Council, Chairman Ballew played a recorded message of the conversation he had with Colonel Buck of the Army Corps of Engineers earlier that morning. In the message, Colonel Buck announced that after a careful review, the Army Corps decided to issue a permit denial by the applicant—SSA Marine. With the announcement, the room exploded with cheers, tears, and sighs of relief.

Witnesses in the room, turned to social media, posting the news, and within minutes “#TreatyWin” reached thousands of friends and allies across the world. This announcement marked a decisive win in the battle to protect Lummi Nation’s inherent and acquired fishing rights. Although it was a joyous moment, Chairman Ballew and the Council members cautioned people not to let their guard down. As Chairman Ballew commented after the historic win: “The need to protect the sacred waters and land of our ancestors is on-going. Although we won this battle today, we know that we need to stay strong and be ready for the next battle.” It is this continuous need for Indigenous Communities to “hold the line”/“defend the line” of treaty trust responsibilities that this article calls into question.

ShellNo Protests—Indigenous Activists and Greenpeace Uniting Against Arctic Drilling

I close the narratives with one last vignette—the ShellNo Protests in Seattle, WA, in which my family and I participated on May 16, 2015. This protest was a “David and Goliath” scene, wherein hundreds of activists in kayaks and traditional Northwest tribal canoes came out to demonstrate against arctic drilling in Alaska by floating alongside a massive, multistory drill rig.

When news came that a massive oil rig, the Polar Pioneer, was aimed to dock in Seattle, WA, before heading up to the Chukchi Sea in the Arctic to commence drilling, people throughout the region mobilized. This time, it was traditional Indigenous Coast Salish canoes and contemporary kayaks that tried to stop the massive oil-drilling rig from contributing to even more release of fossil fuels.

The Polar Pioneer made its way to the Port of Seattle on May 15, 2015, despite massive outcries from the community and a last-minute order from the mayor and the Port Authority to delay its arrival. The rig—owned and operated by Royal Shell—proceeded into the Port of Seattle, with its people stating that they “would be in and out of the port before any legal action could stop them.” The fee—upward of $150 a day—had no impact on this multi-billion-dollar company.

The Polar Pioneer has come to symbolize the disconnect between a scientific understanding of global climate change, and the economic and political frameworks that continue to contribute to environmental degradation. The concerns from the communities, particularly the Indigenous Coast Salish communities of the Salish Sea, are that the impacts of oil extraction and associated global climate change have disproportionate impacts on coastal communities and communities that are reliant on subsistence diets such as fisheries. Thousands of activists—both on land and on water—protested the Polar Pioneer and called for greater attention to this issue of social and environmental justice. The protestors included “kayactivists” organized though Greenpeace, Coast Salish Canoe Families in traditional dugout canoes, and a group of Indigenous activists through the Idle No More movement. The range of protestors “pulling together” for ecosystem protection and against environmental and social injustice was central to the strength of the grass-roots movement. The canoes and kayaks paddled together in the industrial Duwamish Bay in the Port of Seattle to show solidarity and to let Shell and the wider world know that they have reached a tipping point. Expanding oil drilling into the Arctic flies against all scientific recommendations for reduction of fossil fuels—and it does so in an incredibly ecologically fragile environment.

The rally to band together in protest was to show the public and Shell that “business as usual” is no longer viable in a world where the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates sea-level rise upward of 3 feet by 2100. Because of the slow response time for parts of the climate system, the IPCC estimates are already committed to a sea-level rise of approximately 2.3 m (7.5 ft) for each degree Celsius of temperature for the next 2,000 years (IPCC Citation2014). Sea-level rise will impact a large portion of the world’s population, but Indigenous Peoples are acutely affected by the impacts, as their ability to go “somewhere else” is limited.

Sea-level rise, of course, is only one issue associated with climate change—the massive decline of fisheries (due to warmed water) and shellfish (due to ocean acidification) contributes to a loss of ecological integrity, the integrity that provides the base for a traditional way of life for coastal Indigenous people. The loss of fish represents a loss of way of life and tradition. More than that, it represents systemic, institutional, and governance failures at protecting and sustaining life. The lack of connection between “rights” and “responsibilities” in dominant governance systems becomes a moral imperative. As mentioned in the first case, in traditional Coast Salish culture—like many Indigenous cultures—rights to “taking” something like fish or timber go hand-in-hand with the responsibilities of providing for its long-term protection. Through jurisdictional fragmentation and political economic pressures, the responsibilities are not built into governance systems and mechanisms (see ).

The high profile of this politically charged event was telling. Overnight, the news of the “unwelcome” massive oil exploration rig circulated throughout international news, all over social media, and continued to widen the conversations related to environmental and social justice. In fact, since the Seattle event in 2015, hundreds of spin-off protests against the Royal Shell oil company have occurred throughout North America and in Europe and have been highlighted on mainstream news programs and shows such as the Rachel Maddow Show. The media attention followed the rig as it left Seattle and slowly made its way up through the Chukchi Sea, with warnings that the public eye was “watching” the company.

When the Polar Pioneer—dubbed the “Death Star” by activists—left the Seattle docks on June 15, protestors again took to their canoes and kayaks to show resistance. The early-morning departure of the rig marked the start of a 3-week journey to explore for oil in the Chukchi Sea. A leader of the resistance movement was a Coast Salish Canoe Skipper, the late Justin Finkbonner, who led the Lummi Youth Canoe Families through the protests. As Finkbonner noted in one of dozens of interviews after the protests: “I stood in my canoe with a drum and sang an honor song to the Salish Sea and asking forgiveness … I sang a warrior song to encourage the activists to work together and be brave” (Hopper Citation2015).

The confrontations of the canoe and kayak activists and the police were strikingly similar to earlier accounts, including the “fish-ins” in the 1960s with the famed Billy Frank, Jr., and reminiscent of the accounts already given in this article. Witnesses recall that as the Polar Pioneer left its moorings and approached the blockade, police boats nearly collided with the canoes, telling the crew they were too close and would be arrested for violating the protest agreement. Finkbonner countered, informing them that they were the ones at fault for protecting an illegal action by Shell that violated the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott by invading waters where Indigenous Peoples had been granted the right to fish and gather natural resources.

“It seemed to work,” the captain noted. Holding a banner reading “Save the Arctic,” the Lummi Youth Canoe Family paddled ahead of the kayaktivists, keeping in front of the rig, where they spun ahead of the rig with a warrior spirit. As reported in Indian Times Today, “We must have paddled for three hours on the water, maneuvering in front of the drilling platform and tugboats to keep them from getting away” (Hopper Citation2015).

The Coast Guard and police boats removed slow-moving kayakers one by one, pulling out the occupants and relocating them to the Coast Guard base at Pier 36, where they were issued violation notices and fines. Seattle City Council member Mike O’Brian was one of the protesters fined. “There was nothing we could do to save them but to keep paddling,” Finkbonner said. In total, 24 activists were taken into custody. “After about three miles, law enforcement boats succeeded in blocking the Lummi canoe, allowing the oil rig to speed up and outpace them. Eventually, the canoe fell silent as the rig and the tugboats retreated into the distance. Finkbonner stood and told his canoe family they had done well and should keep an open mind and a strong heart” (Hopper Citation2015).

These acts of resistance are both exhausting and exhilarating. Time after time, citizen groups and Indigenous activists are taking stands against dominant society, bucking political, social, and economic systems that systematically marginalize Indigenous communities. In the end, Royal Shell did not pursue the drilling in the Chukchi Sea—announcing that there was not enough oil to make the endeavor financially worthwhile. It is only speculative as to whether the protests and digital watchdogs following the process had a role in the Royal Shell decision. The take-home, however, is that the protestors are calling for system-wide change, and until ecological and cultural loss is considered more thoroughly in the daily decisions of political, economic, and social choices, the political and economic engines will continue to be motivated by profits at the expense of environmental and human health. The fact that Shell received permits to explore the possibility from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency shows a system failure in protecting our basic needs.

What this means for long-term transitions away from fuel-based economies and toward sustainable energies is unclear. However, increasing the discourse that links environmental degradation to social and environmental justice is an important step.

Conclusion: The Role of Indigenous Leadership in Reframing Water Governance

In this article, I explored the role of Indigenous activism at different scales—personal, tribal, and collective—to intervene in key moments to uphold treaty rights and protect Indigenous ways of life. I showed that as tribes and Indigenous actors take leading roles to uphold treaty rights, Indigenous Peoples have become leaders in the social and environmental justice movement, particularly in relation to climate justice and fishing rights.

This article illustrates how time after time Indigenous Peoples have positioned themselves to respond to affronts to their rights to fish (as in the Boldt Decision), and in protecting habitat to ensure that the habitat supports viable fish runs (as with the ShellNo Protests and rejection of the SSA terminal). Building on work by noted critical scholars such as Middleton, Ornelas, Whyte, Grossman, and Parker, this article contributes to the growing literature on environmental and social justice, climate change, and Indigenous activism. Specifically, the role of alliance building is central to the ongoing work to maintain a way of life that relies on intact ecosystems for survival. The role of tribes to assure that the federal government upholds the treaty trust responsibilities is critical in the work for environmental and social justice movements.

The success of Indigenous activist movements described in this article—in addition to other movements such as Idle No More and Standing Rock—is monumental. The recent wins could be the mark of a new era, when Indigenous nations are more visible in the public eye and influential in national and international politics. My hope with this new visibility is that tribes will no longer need to “hold the line” for what was promised to them, and that the onus to continuously remind governing officials of their trust responsibilities will be lifted from Indigenous people. Although the tribes have won recent battles, the proverbial war is not over. Developers will continue to seek to develop ancestral lands, climate change will continue to degrade ecosystems, and individuals will continue to confront structural racism. However, it is my hope that allies and governments alike will step up to reduce these affronts—to stop these developments earlier, to curb the impacts of climate change sooner, to eliminate structural racism altogether. Standing with Indigenous people to maintain their way of life could possibly be the magic bullet that will address chronic environmental and social justice issues.

This change will require a paradigm shift from reactive to proactive. It will require planning for seven generations rather than the next election cycle. It will also require thinking beyond fragmented jurisdictions delineated through colonial acts. This new paradigm will directly address social and environmental justice, embrace collectivism rather than individualism, and foster diverse worldviews. This shift will also require an educational system that deals honestly with its own history, one that looks closely at its own past, institutes appropriate changes to create and foster citizens that celebrate diversity, and respects and honors all life forms. In short, although there is a long road ahead, the pathways are there for structural change that will not only protect Indigenous rights, but will protect our waterways for generations to come.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I thank those who shared their harrowing and inspiring stories that are the inspiration for this article: Thank you to Timothy Ballew II, Tyson Oreiro, and the late Justin Finkbonner, all of Lummi Nation. Thanks also to Northwest Indian College for providing an institutional home and support to undertake this work. Specifically, I appreciate Northwest Indian College’s Institutional Review Board’s review of this article and the helpful and encouraging comments provided by Dr. William Freeman and Dave Oreiro. In addition, sincere thanks to Lynda Jenson for editorial assistance, Sylvie Arques for creating the map of the Salish Sea Basin (), Julia Orloff-Duffy for the generous use of her photographs ( and ), and Chad Norman for capturing what has become an iconic image of the ShellNo protest (). Thank you to Parker Norman and Luke Norman for reviewing the narratives and providing insightful comments on the flow of the vignettes. Lastly, a sincere thanks to the anonymous reviewers and the editors-in-chief, Dr. Peter Leigh Taylor and David A. Sonnenfeld, whose insightful comments strengthened this article.

References

- Ayana, J. 2004. Indigenous peoples in international law. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Biolisl, T. 2005. Imagined geographies; Sovereignty, indigenous space, and American Indian struggle. American Ethnologist 32 (2):239–59. doi:10.1525/ae.2005.32.2.239

- Boxberger, D. 1989. To fish in common: The ethnohistory of Lummi Indian salmon fishing. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Cajete, G. 2000. Native Science: Natural laws of interdependence. Sante Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers.

- Cote, C. 2010. Revitalizing Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth traditions spirits of our whaling ancestors. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Evenden, M. D. 2004. Fish versus power: an environmental history of the Fraser River. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Governor’s Office of Indian Affairs. 2015. Treaty of Point Elliot, 1855. Governor’s Office of Indian Affairs. http://www.goia.wa.gov/treaties/treaties/pointelliot.htm (accessed July 23, 2015).

- Grossman, Z., Parker, A., and B. Frank. 2012. Asserting native resilience: Pacific Rim indigenous nations face the climate crisis. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press.

- Harris, C. 2002. Making native space: Colonialism, resistance, and reserves in British Columbia. Vancouver, BC, Canada: UBC Press.

- Holifield, R. 2013. Environmental justice as recognition and participation in risk assessment: Negotiating and translating health risk at a superfund site in Indian country. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102:591–613. doi:10.1080/00045608.2011.641892

- Hopper, F. 2015. Planning for the arctic: Lummi canoe leads kayaktivists against ‘Death Star’ oil rig. Indian Times Today. http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/06/29/battling-arctic-lummi-canoe-leads-kayaktivists-against-death-star-oil-rig-160887

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2014. Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change [Core Writing Team, R. K. Pachauri and L. A. Meyer, eds.], 151. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.

- Ishiyama, N. 2003. Environmental justice and American Indian tribal sovereignty: Case study of a land-use conflict in Skull Alley, Utah. Antipode 35:119–39. doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00305

- Kovach, M. 2010. Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts. Toronto, ON, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

- La Duke W. 1999. All our relations: Native struggles for land and life. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

- Middleton, B. R. 2011. Trust in the land: New directions in tribal conservation. First Peoples: New Directions in Indigenous Studies. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Miller, B. 1997. The “really real” border and the divided Salish community. BC Studies: The British Columbian Quarterly 112:63–79.

- Miller, B. 2006. Conceptual and practical boundaries: West Coast Indians/First nations on the border of contagion in the post-9/11 era. In The borderlands of the American and Canadian Wests: Essays on the regional history of the 49th parallel, ed. S. Evans 299–308. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Mirosa, O. and L. Harris. 2012. Human right to water: Contemporary challenges and contours of a global debate. Antipode 44:932–49. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00929.x

- Norman, E. S. 2014. Governing transboundary waters: Canada, the United States and indigenous communities. London, UK: Routledge.

- Norman, E. S., C. Cook, and K. Bakker eds. 2015. Negotiating water governance: Why the politics of scale matters. London, UK: Ashgate.

- Nugent, A. 1982. Lummi elders speak. Bellingham, WA: Lummi Education Center.

- Ornelas, R. T. 2011. Managing the sacred lands of Native America. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 2:1–16. http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/iipj/vol2/iss4/6 doi:10.18584/iipj.2011.2.4.6

- Ornelas, R. T. 2014. Implementing the policy of the U.N. declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. International Indigenous Policy Journal 5 (1):1–13. http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/iipj/vol5/iss1/4 doi:10.18584/iipj.2014.5.1.4

- Ranco, D., and D. Suagee 2007. Tribal sovereignty and the problem of difference in environmental regulation: Observations on ‘Measured Separatism’ in Indian Country.” Antipode 39:691–707. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2007.00547.x

- Smith, L. T. 2012 Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Zed Books.

- Taylor, J. 1999 Making salmon: An environmental history of the northwest fisheries crisis. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Thrush, C. 2008. Native Seattle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- United States v. Washington. 1974. 384 F. Supp. 312 (W.D. Wash. 1974).

- Whyte, K. 2015. Indigenous food systems, environmental justice and settler-industrial states. In Global food, global justice: Essays on eating under globalization, ed. M. Rawlinson and C. Ward, 143–56. Cambridge, UK: Scholars Publishing.

- Whyte, K. 2016. Is it colonial déjà vu? Indigenous peoples and climate injustice. In Humanities for the environment: Integrating knowledges, forging new constellations of practice, ed. J. Adamson M. Davis and H. Huang, 1–22. London, UK: Earthscan.

- Wilkinson, C. 2006. Message from Frank’s landing: A life of Billy Frank, Jr. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Wilson, S. 2009. Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Winnipeg, AB, Canada: Fernwood Publishing.