Abstract

The breakdown of social order, social disarticulation, is a common impact of population resettlement. This article shows that social disarticulation results from the dissolution and reconstruction of authority through which people gain, maintain, and control access to essential resources in response to changes in the material conditions inherent in resettlement. Resource access—and the relations it implies—is required for long-term autonomy and security. When new patterns or hierarchies of resource control lead to some part of the group being disadvantaged via subordination to others or exclusion from resource enjoyment, resettled villages experience social disarticulation. We explore this access realignment and differentiation process in the case of the resettlement of two natural resource-dependent communities out of the Limpopo National Park in Mozambique.

Introduction

In 2008, managers of Mozambique’s Limpopo National Park resettled the village of Nanguene to an area 26 kilometers from their original site, just outside of the park’s borders. During resettlement planning, a rift emerged within the village. After resettlement, the village split along the rift. Such rupture is a common “social impoverishment risk” of resettlement (Cernea Citation1997). Cernea and McDowell (Citation2000) call this breakdown “social disarticulation.”

Previous scholars attribute social disarticulation to a loss of place-based identity (Hirschon Citation2000), overburdened social networks and informal support mechanisms (Rogers and Wang Citation2006), loss of authority structures (Downing Citation1996), the destabilization of routine culture (Downing and Garcia-Downing Citation2009), or view it as just a phase of the adjustment process (Scudder and Colson Citation1982). While all of these processes certainly occur, this article offers an explanation for why they repeatedly play out in this destructive way—why social networks tear, why authority structures fall apart, and why the practices and relations called “culture” break down.

The resettlement experiences in the two case studies presented in this paper, Nanguene and Macavene villages in Mozambique, suggests that social disarticulation—and later re-articulation or reorganization of village life—is not principally a matter of emotional or historical attachment to land, nor is it only the disruption of routine or social networks. Rather, it is driven by a change in the political economy, the material relations through which people gain, maintain and control natural resource access. We use Ribot and Peluso’s (Citation2009) “access” approach to shed light on how groups reorganize and on how authorities reconfigure around the ability to enjoy and allocate resource use in the process of resettlement (Lund Citation2016; Sikor and Lund Citation2009).

Ribot and Peluso (Citation2009) define access as “the ability to benefit from things.”1 They view this ability as being socially mediated by people able to control access. Using this approach, we explore how changes in people’s access to material resources shape their wellbeing after a displacement. We explain how the changes in the resources available and who is able to control and thus allocate access to resources reconfigures authority structures. And, we show how, in the process, some authorities lose the ability to allocate access while others take on this function. It is through changes in the ability to allocate resource access that authority structures fall or rise and systems or rule are ruptured or built (Lund Citation2016).

In both cases, prior to resettlement, villagers repeatedly referred to their movement as becoming “children of another land” or “orphans of the land” (Milgroom Citation2017). The residents and authorities knew, and were able to articulate, that by moving, they were going to be subject to the authority and decision-making power of others because of preexisting, ancestral claims to land in the post-resettlement location. Specifically, they knew they would lose their control over access to resources (see also Witter and Satterfield Citation2014). They did lose that control; and, in the process, their relations to each other reconfigured around changes in resource access. New social divisions and stratifications formed.

The villagers of Nanguene were resettled to a new neighborhood within the territory of the existing village of Chinhangane (). Chinhangane had agreed to be their “host.” Before resettlement, Nanguene was also officially a satellite neighborhood of another village where the leader of Nanguene was, on paper, subordinate to another leader. Nevertheless, before resettlement, the leader of Nanguene had uncontested de facto jurisdiction over extensive land, and he could freely grant land and resource access to his villagers and to newcomers. He had effective access control over the natural resources in and around his village, was autonomous and could provide resource security to the residents of his village. In Chinhangane, the resource control of Nanguene’s chief was much more restricted because he did not have jurisdiction over any land—and thus his authority was nullified.

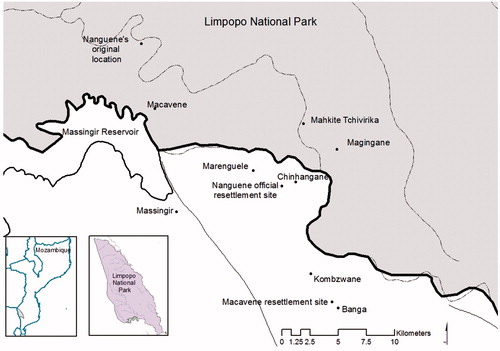

Figure 1. The original location of Nanguene inside the park, the official resettlement site and Nanguene’s re-resettlement location back inside the park near Madingane. The resettlement location of the village of Macavene, near Banga, is also indicated.

In compensation for resettlement, each nuclear family received one hectare of land for cropping, but as a village, Nanguene was not granted any exclusive communal land; they had to use commons belonging to the host village. Within the territory of Chinhangane, the resources were of sufficient quality and quantity (although less than in their original location) to satisfy the needs of the Nanguene residents for the first years after resettlement (Milgroom, Giller, and Leeuwis Citation2014); nevertheless, the host village and the neighboring villages contested claims over the territory, making the new residents feel insecure. Instead of looking to their chief to gain access to the resources they needed, the resettled villagers began to look to the chief of the host village, the chief of the neighboring village on the other side of the resettlement site, and other individuals, native residents of either of the two villages. Because he could no longer grant his villagers access to these resources, the chief of Nanguene lost authority over resource access and, consequently, the authority structures within the resettled village collapsed. Nanguene’s displaced chief abandoned the new village—indeed, he moved to South Africa.

Within the resettled village there were two main kinship groups. Before resettlement, belonging to one group or another made little difference in day-to-day life or in access to resources. But after resettlement, those families who belonged to one of the groups had closer familial ties in the host village and could mobilize these relations to access resources. Families with kinship ties in the host village began to affirm their ancestral ties to the new land and through this, their rights to the use of resources through daily practices and ceremonies. Those who did not share these ties found themselves unsure of where to go. The village divided. Two distinct groups emerged—only one was granted resource-access privileges of “belonging” in the host village.

In the next village that was resettled, Macavene (), a similar pattern emerged. The village was not resettled as a neighborhood of another village; the government officially granted it the political autonomy of an independent village in a territory nearby to an existing village, considered to be their “host” village. Besides the individual plots of land that families were given for their houses and their one-hectare fields, the village was given an official collective title to ninety hectares. This area was insufficient to cover the needs of the residents of the village since not only the quantity, but the quality of the communal land was inadequate for their needs. This change in resource quantity and quality undermined the authority of their leader because he could no longer provide adequate access to the resources his village needed.

In addition, similar to the case of Nanguene, shortly after resettlement, resettled residents began to look to the leader of the neighboring host village for alternative routes to access the resources they needed, despite the official transfer of rights to Macavene’s leader. Residents began to invest in relationships with residents of the host village to gain long-term autonomy and security. While the social disarticulation did not manifest as a clear division of the village into two groups, as in Nanguene, Macavene experienced a more complex fragmentation. Macavene was a larger village with more diverse kinship groups who were not necessarily related to those in the host village. In this case, access rested more on individual relations with the host chief and host villagers. Macavene’s chief lost authority and relevance just the same.

Scholars have shown that resettlement disintegrates community cohesion (Vanden Berg Citation1999). Social networks—that is, social inter-relations of mutuality, reciprocity, domination, and submission—that provide stability and safety nets are broken, and social capital is lost (Cernea and McDowell Citation2000). Resettlement can destabilize authority structures; groups temporarily lose their capacity to manage themselves and become less able to cope with uncertainty (Downing Citation1996). Some authors claim that social disarticulation in planned resettlement results from planners’ lack of awareness of or attention to social issues (Cernea Citation1997: p. 32 as cited in Mahapatra and Mahapatra Citation2000), or lack of sensitivity to the importance of cultural practices and religion (Abutte Citation2000; Vanden Berg Citation1999), or what Witter and Satterfield (Citation2014) call other “invisible” losses, such as relationships, ancestral ties, and non-codified rights and claims to land and resources—losses that are certainly not invisible to those who experience them.

These predominant presumptions point to social disarticulation as the result of the loss of social and cultural capitals. While these losses are important, changes in the material resource base from before to after resettlement, are often overlooked—made invisible to planners—when the causes of disarticulation are viewed as entirely social or cultural (e.g. as primordial attachments to the land or a territory). An access approach, however, frames cultural-social relations as emanating from, integral to, and mutually constituted with material changes. Cultural and social relations reconfigure around changes in material resources, while social and cultural meanings are mobilized to shape patterns of material distribution. Here cultural-social relations, reflected in discourses, laws, and practices, are embedded in doxa or habitus that rationalize and support patterns of material access (Bourdieu Citation1977).2 Our approach focuses on the material relations of access as they shape and are shaped by the sediment of long-negotiated relations, meanings, and rules (Downing and Garcia-Downing Citation2009; Ribot and Peluso Citation2009).

Downing and Garcia-Downing (Citation2009), in their theory of routine and dissonant cultures, observe that resettlement evokes basic questions of identity, such as who am I, and who are we (see also Douglas Citation1992). They describe how spatial and temporal organization of routines addresses these primary questions of identity on a regular basis through generating a sense of predictability that resettlement disrupts. After resettlement, routine culture begins to break down into dissonant culture, following which people work to establish a new routine culture to be able to re-anchor their basic questions of identity. One breakdown they describe concerns the cultural process of “redefining access to routinely allocated resources” (Downing and Garcia-Downing Citation2009, 233), which, they observe, often launches people into impoverishment. They argue that the act of defining the new routine culture is a reaction to dissonant culture—an attempt to regain a sense of normality and stability—and that redefining access to resources is one part of this process. They imply that redefining access is a culturally driven action, rather than a material phenomenon that requires social and cultural adjustment.3 Downing and Garcia-Downing (Citation2009, 227) also do not explain why social relations are redefined in one way rather than in another—a question we explore.

We agree with Downing and Garcia-Downing (Citation2009) that changes in access reshape people’s sense of security. Perhaps more importantly, as Mary Douglas (Citation1992) argued, a sense of insecurity or danger, due in our cases to changes in resource access, causes people to regroup—defining who is us and who is them and enabling a group to take on an identity in response to threats to material wellbeing. In southern Africa, competition among lineages for control over access to resources has been, and continues to be, a common cause of the division of social units as small groups break off to establish their own territory with their own control over access to resources (Harries Citation1994; Junod Citation1962). In this instance, it is the establishment of secure access to resources that pushes people to question and reshape their identities. Seeking social and cultural ways to secure access is not a result of identity disruption that needs reestablishment. Rather, the re-identification is part and parcel of establishing new secure access relations. This is facilitated by the presence of abundant material resources and systems of rights, justice, and governance through which to renegotiate patterns of interaction (as Downing and Garcia-Downing Citation2009, 243, 250 imply)—all of which require systematic attention to material resources and their relation to structures of governance and authority.

Colson (Citation1971, 62), rooted in a materialist approach, argued that the impact of resettlement on social relations is shaped by the organization of productive activities linked to a new geographical setting. She shows how more subtle and long-term effects, on kinship relations specifically, appeared to be due to the varied conditions and resources of the different resettlement areas, and the way that people adjusted to these changes (Colson Citation1971, 71, 91). This article builds on Colson (Citation1971) and borrows observations from Downing and Garcia-Downing (Citation2009) to deepen our understanding of how changes in access to resources due to resettlement reshape authority structures in ways that generate social change or damage. We argue that social changes are pronounced in response to changes in resources because authorities in natural-resource-dependent communities are largely constituted by their ability to control and allocate natural resource access (Ribot and Peluso Citation2009). A change in the quantity or quality of available resources, which is an inevitable outcome of resettlement, can reshape access relations (Milgroom, Giller, and Leeuwis Citation2014). Changes in the relations that authorities have to resources—that follow from changes in the available resources, as well as new competitions among authorities—disrupt or reinforce, at a minimum destabilize, existing arrangements (see Lund Citation2016; Sikor and Lund Citation2009).

To frame our analysis of authority relations and social disarticulation resulting from resettlement, the next section presents our access research approach. This is followed by contextual description of the cases of Nanguene and Macavene. After outlining our methods, we develop the full case of Nanguene and then draw select material from Macavene for comparative purposes. This is followed by a discussion and conclusion with reflections on the implications of our observations for resettlement practice.

Access Frame

After resettlement, people often lose access to common-pool resources such as the forest, bodies of water, or grazing lands, jeopardizing community livelihoods and creating social tensions (Cernea Citation1997). This loss of access to natural resources also occurs at an individual level; many people are forced to change their resource-based livelihoods (WCD Citation2000). In their new site, even when the resource base is similar; however, people are often no longer able to access the resources they enjoyed before resettlement (Mascia and Claus Citation2009; McLean and Stræde Citation2003; Schmidt-Soltau Citation2003). This is not only because of diminished resource quality or quantity but rather because of changes in social relations of access. While there are shifts in material and in social relations, two kinds of shifts in social relations occur. One is the realignment of people’s relations to authorities within the resettlement community around the allocation of access to the new resource base. The other, noted by Abutte (Citation2000), stems from “cultural” clashes and competition over resources with people who live in the area before the resettlement, i.e., the “host” villages. These two shifts occur simultaneously.

Access to resources is locally specific and dynamic in practice (Gengenbach Citation1998; Shipton and Goheen Citation1992). A change in the norms and rules of access to resources or a change in the rights-based, structural or relational mechanisms of access influence how people benefit and who benefits from resources (Agrawal and Gibson Citation1999; Berry Citation1989; Peluso Citation1996). With changes in quantity (how much of a resource is available) competition for use of the resource is reconfigured—intensified or reduced. The quality of a resource, defined by Milgroom, Giller and Leeuwis (Citation2014) as the value of a resource for a specific desired use, may also shift if resources are overexploited (deforestation or soil erosion due to more use), if resources change due to broader ecological changes (introduction or arrival of invasive species, changes in weather or climate, or due to a storm), if market demands shift the values, or if new knowledge about a use of a resource is brought by the newcomers. But, to understand how these changes unfold and are translated into new distributions of access, we need to also understand how hierarchies form and are re-formed around resources (Lund Citation2016; Sikor and Lund Citation2009).

Webs of access are the thickly spun social relations related to place and the resources in place; so, when a community moves from one place to another, new strands, or pathways, of access are added and others dissolve as obsolete. The social hierarchies for gaining, maintaining and controlling access realign with the new web of relations that form around what appear to be the most-secure means for obtaining the necessities of life. In short, changes in the resource base (in these cases from place to place) lead to reorganization of access channels which, in dialectical tension, reconstitute and are reconstituted by authority structures. As in the cases presented in this article, authority and social order are linked to each leaders’ ability to allocate access to material resources (Lund Citation2018; Sikor and Lund Citation2009). Authorities are constituted by their ability to mediate access relations. The locating of a community within a new landscape—overlaid by an existing complementary or competing authorityscape—shifts social relations as groups and individuals scramble to reposition themselves to meet material needs (Colson Citation1971).

Resettlement from the LNP

Methods

The research presented in this paper is based on ethnographic fieldwork by the first author from 2006 to 2010 and follow-up in 2014 and 2016. Participant observation was the main method employed while living in Nanguene over a period of two years during the preparation for resettlement (December 2006–November 2008), and for 18 months in the post-resettlement location, the village of Chinhangane (November 2008–June 2010). All of Nanguene’s 12 households, a selection of households from Chinhangane and Macavene (25 and 18, respectively) were closely followed by means of observation, interviews, and informal discussions with individuals and groups. Open and semi-structured interviews were carried out with 215 residents in eight villages, district, provincial, and national government officials (including park staff), donor representatives, private consultants, and NGO staff. In addition, ten park and two internal village meetings were attended. Meetings and interviews were transcribed and translated, as were unpublished park documents, consultancy reports and meeting minutes. She also used film (a method also described in Ribot Citation2014) and participatory photography (Wang and Burris Citation1997) as data collection methods. Qualitative data were sorted and coded in an iterative process during data collection and again after fieldwork was completed (Patton Citation1990).

Study Site: The Cases of Nanguene and Macavene

The Limpopo National Park in Southern Mozambique was established in 2001 as part of the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area, straddling boundaries of Zimbabwe and South Africa. In 2003, park managers including members of the Peace Parks Foundation (PPF), a South African NGO instrumental in the establishment and management of the park, decided that approximately 7000 people residing in eight villages along the Shingwedzi River that runs through the center of the park had to be resettled. To develop a resettlement protocol for the remaining villages (), PPF initiated a two-village pilot project with Nanguene and Macavene. The German development bank, Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), the major donor to the LNP project and sole donor supporting the resettlement, required the adoption of the World Bank Involuntary Resettlement Policy (WB OP 4.12) to guide the resettlement.

The WB OP 4.12 requires compensation to be provided for resettling people that would at least replace losses incurred because of the relocation. Compensation included one brick house to replace each household’s main house, cash compensation to replace infrastructure, one field of one hectare, cash compensation to replace land foregone, a seed package, tree saplings, and basic building materials, and payment for the transport of livestock for livestock owners and a small amount paid to everyone to assist with the transition. No specific measures were taken to compensate for the loss of access to common-pool resources.

The villages of Nanguene and Macavene had already been forced to move on a number of occasions, most recently because of the civil war that ended in 1992, villagization policies implemented by Mozambique’s ruling party that regrouped small settlements into larger villages for the purpose of providing services to the rural area, and the creation of a dam in the early 1970s. In 2008, the village of Nanguene was resettled outside the park’s boundaries, next to the village of Chinhangane, and in 2013, Macavene was resettled next to the village of Banga (). The existing villages agreed to host the resettling villages, and the resettling and host village representatives worked together with the LNP staff to plan resettlement. However, while care was taken to stress that the resettling village leaders would remain the leaders of their villages, how the two leaders would function side by side was not explicitly defined.

Land, Leadership, and History

All land in Mozambique is officially public; there is no private ownership of land, but customary land tenure is recognized in the national land law established in 1997. Traditional leaders are the hereditary descendants of the “owners of the land”, also considered the founders of the village and associated with the dominant kinship group in the village, indicated by last name. Sometimes the traditional leaders are also the politically recognized leaders of the village. In villages where this is not the case, however, issues of land allocation, as well as spiritual rituals and ceremonies fall under the jurisdiction of the traditional leader. Although the traditional leader or the village leader has the ultimate word about land allocation, male descendants of the “owner of the land” can also make land-use decisions (Witter Citation2010). Land can be used by people from other villages by requesting permission to use the land from the leader, or another male descendent of the appropriate kinship group, but a non-kinship group member is not considered an “owner” of the field he or she uses (Witter and Satterfield Citation2014). This has important implications for resettlement because unless a resettled family is a lineage member of the kinship groups considered to be the “owners of the land” in the new location, to attain “ownership” of land is difficult. Those without kinship ties have no rights in the land of others.

The region inside the LNP is sparsely populated (two to four people/km2 inside the park and approximately 14 people/km2 in the resettlement area). Land in the park is not a major constraint; the amount of land that a household uses is determined principally by their capacity to work the land (Gengenbach Citation1998; Milgroom and Giller Citation2013; Witter Citation2010). In the new location land availability is limited by higher population density; however, there was sufficient land for the cropping and grazing needs of the resettling and host residents, at least for the first year (Milgroom, Giller and Leeuwis Citation2014). Despite adequate land resources, the case studies show that access after the re-location was contentious.

Here, we present the case of Nanguene, followed by comparative illustrations from Macavene.

Ancestral Control Over Land in Nanguene

While the 18 resettlement houses were being built in Chinhangane, the guards that kept watch over them started hearing things in the houses at night. They reported that they heard stones being dropped on the roofs and ghosts. They said the ancestors were angry because they had not been informed about Nanguene people coming to live on their land. A ceremony had been performed for the ancestors of Chinhangane to inform them of the arrival of Nanguene to their land. But, the apparition of ghosts in the resettlement houses called attention to the fact that the houses had not in fact been built on land that belonged to Chinhangane, the host village; rather, they were on the land traditionally belonging to the neighboring village, Marenguele. Nanguene’s houses had been built on a site of perennial conflicts caused by historically overlapping jurisdiction over land. These conflicts complicated the incoming residents’ access to resources, specifically to cropping land, and left them without social room to maneuver between one village and the other.

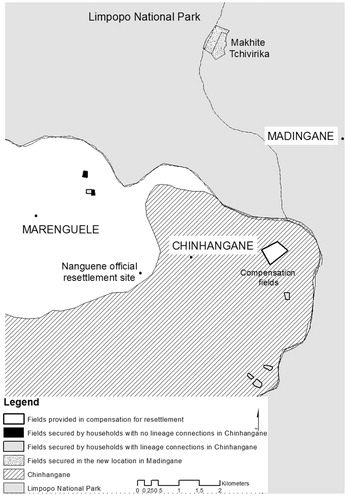

Traditional leaders are locally recognized as having power over their traditional territories, but they are not recognized by the formal political system of government, and these territories differ significantly from modern, political village delineations. Chinhangane, the official host village for Nanguene, is a relatively new village created by villagization that joined lands that were under the authority of two important traditional leaders. Marenguele, a village that lies north of the present day Chinhangane, was one of the important traditional chiefdoms (). The land around the new village of Chinhangane is still ruled in practice by the leader of Marenguele via ancestrally derived authority despite the fact that this leadership is not politically recognized.

Figure 2. Map of the boundary between the Marenguele and Chinhangane with respect to the location of the resettlement houses and the location of the fields provided in compensation for resettlement. Fields permanently secured by residents of Nanguene from the Mahlaole lineage and from other lineages are indicated as well as the location and area of land secured in the newly established village Makhite Tchivirika.

The LNP resettlement team built the resettlement houses within Marenguele’s territory, on Marenguele’s land. The compensation fields were located on neighboring Chinhangane’s land (). The leaders of the host villages chose locations for the houses and fields to be given to resettling people on land that was of least value to the host villages and the LNP resettlement staff accepted their choices (Milgroom, Giller and Leeuwis Citation2014). This complicated an already complex situation regarding access to resources in a territory historically claimed by others. It is likely, as we see later, that the leaders of Marenguele and Chinhangane were well aware of this when the decisions were made even though it only came to public awareness after the resettlement was complete.

Becoming Children of Another Land

As resettled newcomers, Nanguene villagers felt they would become “children” in the new land. This metaphor referred to the way that the residents of the resettled village, including the leader of the village, would lose their authority to make independent decisions as adults and would be obliged to obey the rules of others.

The rules of the game, as one Nanguene resident described, would always be defined by the original residents of the land: “If they [children from both villages] are playing ball they [a child from Nanguene] can say hey, you kicked me! And the other child can say no, this is not Nanguene…; even if we are living together it does not mean that we are equals.” It became clear that regardless of official government policy, the articulation of authority, and in this case, the subordination to authorities of the existing village territory, in post-resettlement would have major implications for the future of the residents of Nanguene.

Without intervention of higher-level government authorities, a newcomer in another’s territory cannot own land or control access to resources—it is only possible to use the resources with the host village’s permission. The host villages were forced by the LNP to accept the resettled villages and to grant them the minimum required land. In return, they were offered compensation and their leaders were consulted about what land to give to resettled villagers. However, when it came to ceding any more land than the minimum in the initial agreement, the negotiations became tough. This was especially so when land with higher value and limited quantity was requested, such as land for irrigation near the river. Irrigated plots were included in the initial compensation package but LNP staff only later attempted to secure a location for these plots for the people from Nanguene, at the insistence of the resettled residents, supported by the WB and KfW. The leader of Chinhangane identified available land but later reneged on the offer. Five times over two years different people allocating or offering land later reneged on their offer. The central-government appointed district administrator was finally called in to mediate in the negotiations and eventually a piece of land was ceded to the village of Nanguene for irrigation.

The imposition of the higher authority, however, created animosity. The concerns that the residents already had about losing authority and becoming “children of another land” were deepened when they found themselves stuck between two competing authorities, Marenguele, and Chinhangane, as well as between formal and informal legal environments.

Access to Dryland Fields

The villagers of Nanguene were moving to live on the land of Margengule, but the fields they would need to cultivate were in the territory of Chinhanguane. This posed problems. The leader of Nanguene asked: “The sons of Nanguene, when they grow up and get married and want fields, how will they have fields?” The leader of Chinhangane responded: “I can’t receive people [give them land to cultivate] when they live on someone else’s land. The problem is where they are living…. I can’t take my ancestor’s land and give it to Nanguene because of [rivalry with] the leader of Marenguele. Chinhangane’s maize will be taken from Chinhangane to the leader of Marenguele to do ceremonies there. When the children grow up they will see what they will do. If they talk nicely they can find fields, but if they are talking like they are now [i.e. asking for autonomy] they won’t have fields.” This answer reconfirmed Nanguene’s sense of insecurity.

The leader of Chinhangane said that he would not give Nanguene more fields because the Nanguene villagers would be living on Marenguele’s land and would pay allegiance to the leader of Marenguele. However, it appears as though the leader of Chinhangane strategically chose to allocate contested land in order to exploit ambiguities and not have to provide more fields to the resettled village. He pretended not to know anything until the incident with the ghosts occurred. Furthermore, the leader of Chinhangane threatened the resettling residents when he said that they would have to “talk nicely” to get any fields—they would have to maintain their access by showing deference. Because the LNP resettlement staff gave land use titles for the compensation fields directly to the resettled families, Nanguene’s leader became marginal, having no territory to control or allocate.

Residents of Nanguene would have to access fields through family ties and personal connections rather than through the standard mechanism of attaining permission from the village leader. Resettled families with connections were able to attain permanent fields through deals they made before resettling or very soon after resettlement. Some of these fields were provided by the village leader of Marenguele to gain legitimacy and loyalty. Not a single family secured a new permanent field in the six years between 2010 (18 months after resettlement) and 2016.

A common practice began to occur with residents who managed to borrow fields for temporary use. Residents of the host village would “lend” plots of forest (those being saved for future generations) to resettling residents for temporary use under existing informal rules and norms of access to fields. However, they began to abuse this practice by taking the field back after resettled residents had cleared the forest and plowed—thus getting free field-clearing labor. This abuse of the resettlers’ labor and security caused humiliation, frustration, and animosity that led resettled residents to stop borrowing fields.

Rearticulating Authority through Traditional Ceremonies

One of the most important ways that leaders legitimize and re-articulate their authority is through traditional ceremonies in which ancestors speak in support of the leaders. Thus, in the context of overlapping authorities and claims, the issue of how ceremonies would be organized became a contested topic in discussions prior to the move. Host villagers were concerned about the extent to which the resettling villagers would attempt to remain autonomous units and carry out their own ceremonies. The LNP staff person promised the residents of the resettling villages that they would remain autonomous and not be subject to the authority of the host villages. This assurance was given despite the fact that all parties involved knew that Nanguene would officially become a neighborhood of Chinhangane and that they would have no ancestral authority in the new land. Indeed, customary norms imply that the resettled villages will have to give in to the traditional leadership in the resettlement location (Ekblom, Notelid and Witter Citation2017; Witter Citation2010). This promise, therefore, reflected either an overly optimistic, persuasive attitude by the resettlement implementation team—or an unwillingness to grapple with this difficult issue.

Ceremonies are the space in which authority is asserted and legitimized, reshaped and performed (Ekblom, Notelid and Witter Citation2017; Witter Citation2010). They are where authority, identity, and control over resources are performed and renewed. The leader’s autonomy to decide when and where to hold their ceremonies is a symbolic representation of their autonomy as leaders. Further, if leaders do not have land resources to allocate through the ceremonies, the ceremonies also lose their meaning. They cannot assert their authority if they are “children of another land” who have to ask permission to hold ceremonies or distribute land rights. This autonomy, however, was contested between resettling and host village residents. A resident of another resettling village said: “… We don’t want to be slaves. It seems that where we are going we will feel like slaves… No one should tell us to dance or blame us for no rain if we don’t dance….”

In response to this comment, a resident from another host village stated: “We know they will do the ceremonies they have to do. If they go to church they will go to church in their own way. What the committee decided was that if they wanted to do ceremonies, the resettled village should ask permission and invite the host village to participate.” Whereas no such agreement was made by the committee, the statement is an expression of how these matters have traditionally been dealt with—official arrangements ignored traditional practices. Despite the fact that this statement made it clear that the host villages were not comfortable with the resettling villages having total autonomy over their ceremonies. The host villages expected that the resettling villages would invite them to their ceremonies and that the resettling residents would participate in the host village ceremonies—despite that the resettling villages were told otherwise and did not want this. These divergent expectations influenced the disposition that the host residents had towards providing access to resources, specifically dryland fields, for the resettling residents. Many of these claims and counter claims for ceremonial authority foreshadowed the conflicts that played out after resettlement.

Re-resettling Back in the Park

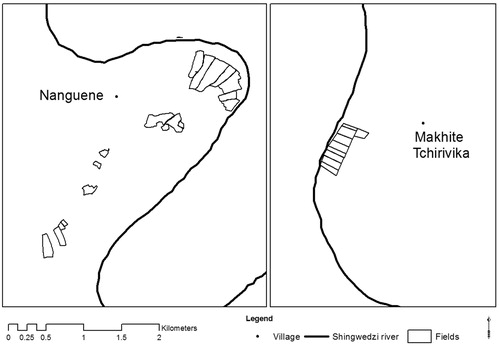

Frustrated by not being able to gain access to the fields that they needed, half of the newly resettled households went back into the park in search of a place to establish a new village. The leader of Nanguene and his family was one of these households. They called the new village “Makhite Tchivirika.” Makhite is the name of the area and Tchivirika means “those concerned with working.” This name was chosen by the leader of Nanguene in response to what he felt was a lack of desire to work on the part of the households who had stayed behind in the resettlement location. The new village was established on the traditional land of Madingane (), not coincidently, because the grandfather of the leader of Nanguene had been born in Madingane. Permission to establish a new village and to open up the land for their fields was easy to secure. Each household paid the leader of Madingane 100 Mozambican meticales (four USD or two days income) for a household plot and the same amount for each field they wanted to open. They organized their fields along the river in a similar spatial organization to their original fields in Nanguene (). An adjacent area was identified for the expansion or rotation of the fields to be used when needed.

Figure 3. Back in the park, in the new village of Makhite Tchivirika, ex-residents of Nanguene copied the same spatial organization of their fields as they had in their original location in Nanguene.

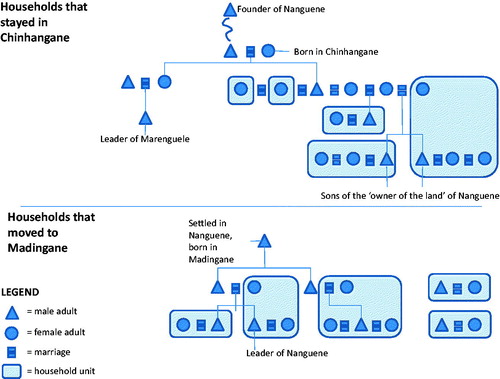

Further analysis of who stayed and who left the official resettlement site and who had managed to access which resources in Chinhangane, however, revealed that there was much more to the decision to return to the park than just inability to access sufficient fields. The original village of Nanguene was made up of households with three last names: Mahlaole, Maimele, and Zhita (). Nanguene had been founded by ancestors of Mahlaole and therefore the Mahlaole lineage were the “owners of the land” in the original location. However, the leader of Nanguene at the time of resettlement was not a member of the lineage that had traditional jurisdiction over the village. The leader had been chosen as the leader of Nanguene because of his leadership qualities during a time in which the sons of Mahlaole, the successors of the previous leader, were not interested in taking on the responsibility.

Figure 4. Kinship charts illustrating the division within the village based on those who had one common ancestor.

Despite disinterest, they, especially the eldest, remained influential in making important decisions for the village, such as the choice to be resettled to Chinhangane. A grandmother of the Mahlaole family had been born in Chinhangane, and many members of her lineage who remained in Chinhagane had become important members of that village. Therefore, the Mahlaoles from Nanguene knew that they were moving to a place where they had family members who would facilitate access to resources for them. Not surprisingly, the households that went searching again for a site to found a new village back inside the park were all those who did not belong to the Mahlaole lineage. This included one household which carried the Mahlaole name but who was not a member of the same group of Mahlaoles that lived in Chinhangane (). shows how the families who stayed in Chinhangane had a common ancestor born in Chinhangane, and those who went to the territory of Madingane shared a common ancestor born in Madingane. The latter group had no ancestor born in Chinhangane.

This story cannot be reduced to a simple explanation of lineage as the main facilitator of access to fields. Lack of access to fields as the main reason for re-resettlement is also misleading. Of the five families who managed to secure permanent fields, three were Mahlaoles and two were of another lineage. Some non-Mahlaole households managed to access fields and yet still decided to leave in search of a new village while some Mahlaole households, who did not manage to access fields, nonetheless decided to stay in Chinhangane. Something more than access to resources is clearly at play here: access to autonomy and thus security over the longer term—something they acquire by staying with a leader they trust and through exercising land-tenure rights in their lineage-based political environment. In short, resources important because they are mean to attain the valued outcomes of sustenance, income, dignity, and most of all, autonomy and security. In Chinhangane, the residents who had no direct claim to the dominant lineage may have been able to access the resources they needed for their livelihoods, but a breach of autonomy, identity, security, and dignity led them to search for a place where they did not have to request permission from others to open fields and carry out ceremonies.

Subordination and Manipulation in Macavene

After two rainy seasons, 18 months after resettlement, only five of ten resettled households in Nanguene had managed to secure permanent fields. The second village resettled, Macavene, was larger than Nanguene and was given some land of their own, rather than being moved into a neighborhood of another village. Yet, this did not translate to greater autonomy because of the poor quality of the land ceded to them. It was rocky, dry forest land that was not good for agricultural fields. It left them still dependent on the neighboring “host” villages. So, similar issues emerged. In 2014, one year after resettlement, one resident lamented, “I am an orphan of the land. I have to be humble and not cause any problems so that when I go to ask for a field they [authority figures from the host village] think of me as a good person, otherwise I will never get fields.” This man had the feeling that subordination was the only viable pathway to access land when he had to compete with all of his neighbors for fields.

The leader of Banga, the host village for Macavene, used demands from his previous negotiations with the LNP staff as leverage in negotiations. He said, “We asked for a fence so that our cattle and that of Macavene don’t mess with our fields. That has not been done. We have decided that if this doesn’t happen we won’t give land to the people of Macavene for fields” (Milgroom Citation2017). In short, the host villages authorities still hold considerable power over the resettled villages despite the autonomy that was “officially” granted to the resettled villages. The host village leader was using this power to manipulate LNP authorities into giving them the compensation that was promised to them, and in the meantime leaving the resettled residents without fields and without a way to provide for themselves, putting them at risk of hunger.

Discussion and Conclusion: Authority and Access

The legitimacy of village leaders was contested when their villages were resettled to land with inferior natural resources and preexisting local authorities. Displaced villages experience a loss of security and autonomy as they settle in their new natural and social surroundings. Downing and Garcia-Downing (Citation2009) call this disruption “cultural dissonance.” We call it access struggle. They argue that as resettled people seek new answers to the basic questions that orient them in their daily lives, they muddle through and struggle to find new ways to belong within shifting or new relations and hierarchies, and, in the process, experience loss of identity, confusion, and cultural disintegration. In our case studies, however, as with Colson (Citation1971), it is the struggles over material resources that generate social division, conflict, and dissolution. Reestablishing secure routine material relations is the main preoccupation during transition and adjustment associated with post-resettlement (see also Colson Citation1971; Scudder and Colson Citation1982). The frame we use to explain insecurities matters in how we might go about preventing, managing, or repairing displacement distress.

In their framing, Downing and Garcia-Downing (Citation2009, 233) cast changes in access patterns as cultural changes with material effects that follow. They list patterns of cultural dissonance (ephemeral dissonance norms, dissonance overload, redefinition of access to routinely allocated natural resources, and increases in the frequency of rituals) as elements that drive social disarticulation. With culture at the center, their analytic frame includes shifts in patterns of access to resources as a factor that is caused by and, via poverty, generates social disarticulation. Access to resources, however, is our analytic entry point. Changing access is central to social and political-economic changes, including the changes they describe as cultural. We integrate cultural factors when people mobilize them as elements in the causal chain of particular instances in which access is or is not achieved.

In our case studies, social relations and hierarchies, which some label as cultural factors, play important roles in access. We observed direct and indirect access based on (a) belonging to the lineage of the traditional owners of the land, (b) social hierarchy, personal skills and character—ability to establish bond friendships with members of the lineage of the traditional owners of the land, (c) performing deference to other authority figures (e.g. via the ability to “talk nicely”), including support from politicians or traditional leaders, (d) taking advantage of opportunities to exploit ambiguities in claims to resources within overlapping jurisdictions, (e) inventing statements about the content of, or conveniently interpreting agreements to support claims, and (f) cash purchase of access to plots—where cash is accessed from savings, resettlement compensation, or labor in new markets.

In the cases presented here, with or without legal rights to land of their own, leaders of the resettled villages lost their capacity to allocate land and to control access to natural resources—and “traditional” authority relations changed because of this. As authorities or residents of the host village became the viable channels of access to resources for the resettled villagers, the resettled village leaders lost authority because they were unable to allocate needed resources to villagers—they lost their role and their legitimacy. Social hierarchies fell apart and relations realigned toward leaders who could effectively serve people’s access needs. This is how resettlement leads to social disarticulation. The legitimacy of leaders is undermined by (a) their inability to meet needs due to changes in the quantity and quality—amounts, locations, physical distributions, characteristics endowing economic or productive values, changes in familiarity with the resource base, etc.—of resources under the control of that leader and (b) their inability to allocate access due to competition with preexisting authorities over control of resource allocation.

This study illustrates how hierarchies—between authorities and their communities— can form like class relations between those who need and those who control access. Loss of access control is tantamount to loss of authority; access control constitutes authority (also see Lund Citation2016). Society stratifies around relations of access gaining, maintenance, and control. Access control and maintenance, as Ribot and Peluso (Citation2009, 159) have argued, parallel Marx’s capital-labor relations. Those who own capital and those who labor for pay relate similarly to people who control access and those who must maintain their access via those who control. In both cases, “it is in the relation between these two sets of actors that the division of benefits is negotiated” (Ribot and Peluso Citation2009, 159). Subordinate actors must sacrifice some benefit to those who control it, expending resources to cultivate relations to maintain their access. Relations follow material needs and the structural contours of maintenance and control. Without control, authority dissolves and social relations shift.

Access analysis, in this sense, is a way of discerning the nuanced structure of hierarchy and stratification. It expands Marx’s idea of class. In an access hierarchy, there are actors who must maintain access through someone who controls access, but those who control access may also have to maintain the access that they control thorough relations with higher actors and authorities or constellations of parallel actors and authorities. Authority itself is built by the offer of access to people who need it (Lund Citation2018, Citation2016; Sikor and Lund Citation2009), but authority is also recognized, and thus granted, by the institutions, authorities, and other relations above, around, and below (as in elections or intervention of higher-level authorities) (see the concept of the “politics of choice and recognition” Ribot Citation2007; Ribot, Chhatre, and Lankina Citation2008). Access relations form fluid multi-layered social hierarchies—webs of access—in which those who control the access of some must maintain through others. In this sense, interventions must attend to supporting and strengthening, that is choosing and recognizing (Ribot Citation2007), the resettled village authorities via popular mobilization or from above. The formation of multi-layered hierarchy is a promising area for future access research—access control can be allocated as part of authority building processes.

Our cases speak of two other important and interlinked resources that people aspired to have: security and autonomy. Watts and Bohle (Citation1993) argue that empowerment is the ability to influence the political economy that shapes one’s security, or one’s entitlements. We see in the case studies that autonomy, the ability to shape one’s destiny, was an important resource for the displaced populations. This autonomy was closely linked to security—in so far as it removed the element of arbitrary treatment (or exposure) as “children of another land” and left room for a more secure sense of future access relations.

We propose using the access approach for investigating the underlying root causes of displacement-related social disarticulation on a case by case basis. Access analytics can show why villages must be resettled with sufficient land of adequate quality to avoid breakdown of authority structures and social disarticulation. It means that the real cost of resettlement is in shifting people to a better—not just an equal—situation so that there is some room for adjustment in new patterns of interaction around access. Control of sufficient quantity and quality of land—meaning land adequate to the requirements of adjustment—must be the minimum standard set from the beginning of the process. We argue that if resettlement is not going to provide for alternative livelihoods, it must provide sufficient land of adequate quality for natural-resource based livelihoods. In that process, attention must also be paid to placing the allocation of those resources within the jurisdiction of resettled authorities—if they are to remain relevant and legitimate. Of course, if appropriate conditions cannot be provided, it is better not to resettle people (de Wet Citation2009).

Access analysis also brings attention to the problems generated by the subordination of villages to the authority of existing communities—even when the host villages agree to “give” (remaining in the position of provider) the resettled village full autonomy. People living in and moving to a new location can predict many conflicts, but they do not know the meaning of hosting or living in the territory of a host until resource struggles emerge. Thus, agreements made in advance must include enforcement and adjudication mechanisms that guarantee fair integration or autonomy of displaced villages. Another means to ease displacement stress is to build mechanisms of representation into resettlement. Downing and Garcia-Downing (Citation2009, 243) point toward systems of rights, justice, and governance as a means to renegotiate meanings and the regular patterns of familiar interaction. Chakrabarti and Dhar (Citation2009) call for a people-centric policy whereby resettling groups themselves exercise self-governance and self-determination in deciding about the design of their own rehabilitation. The case presented here shows that resettling residents were very aware of the dynamics they would face in post-resettlement, they knew what they needed for their livelihoods, they expressed themselves clearly and they have come from a history of self-organization.

In terms of representation, however, the challenges to and changes in access relations before and after displacement poses complex ethical questions. In resettlement projects, should the status quo or “traditional” authorities—of moved or host village—be supported? Is the status quo just and ethical? Do existing leaders represent people’s needs and aspirations? Was there some preexisting form of integrative democratic representation within these communities conducive to establishing relations of access that serve the largest cross-section of community? In the case presented here, there were some elements of status quo governance supporting people’s needs, but it was not without its injustices. On the one hand, traditional practices of access to resources were based on a system of solidarity that ensured every family land to plant on. This system broke down after resettlement due to the high number of people demanding access to a finite amount of resources. This already existing system could have been supported and encouraged after resettlement, but it, unfortunately, fell victim to poor implementation of resettlement. On the other hand, existing leaders and leadership practices discriminated against women, particularly divorced women. Decisions were made primarily by men, excluding women from important conversations that significantly affect their lives. Furthermore, elite capture is evident in local politics and decision-making processes—this, and discrimination against women, held true in resettlement planning and implementation. The question is how can those who have been resettled determine their own futures and have influence over those who govern them—regardless of the preexisting structures of authority?

Our questions about the presence of equity and justice in the villages that are being resettled are speculative. The preservation or dissolution of hierarchies is not the normative goal of our analysis. Our goal is to show how material relations of access shape the process and outcomes of resettlement and how authorities—traditional or new—might help resettled people cope with social disarticulation and to re-organize into a more-just and sustaining set of local social, legal, and political arrangements.

Acknowledgments

We thank the residents of Nanguene and Chinhangane for their support of this work. This article was based on research conducted for a chapter in a Ph.D. thesis written by Jessica Milgroom (Milgroom, J. 2012. Elephants of democracy: an unfolding process of resettlement in the Limpopo National Park, Wageningen University).

Notes

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In our view, “the ability to benefit from things” also includes human-environment relationships in which “using” land, seeds, water, and other natural resources implies entering into a reciprocal relationship of responsibility, rather than one of unilateral benefit (Corntassel Citation2008).

2 We prefer Bourdieu’s (Citation1977) approach to capitals. The widespread use of Coleman’s (Citation1988) style of social and cultural capital, e.g. social bonds and bridges or rules of the game, diverts attention from having to recognize and invest in the appropriate material capital, supports far beyond the standard issue brick house or even roads.

3 They imply, but do not state clearly that this renegotiation is “cultural” and thus the changes in access result from cultural change. Clearly the process is dialectical.

References

- Abutte, W. S. 2000. Social rearticulation after resettlement: Observing the Beles valley scheme in Ethiopia. In Risks and reconstruction: Experiences of resettlers and refugees, eds. M. M. Cernea and C. McDowell. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Agrawal, A., and C. C. Gibson. 1999. Enchantment and disenchantment: the role of community in natural resource conservation. World Development 27(4):629–49. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00161-2.

- Berry, S. 1989. Social institutions and access to resources. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 59(1):41–55. doi:10.2307/1160762.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cernea, M. M. 1997. The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. World Development 25(10):1569–87. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00054-5.

- Cernea, M. M., and C. McDowell, eds. 2000. Risks and reconstruction: Experiences of resettlers and refugees. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Chakrabarti, A., and A. Dhar. 2009. Dislocation and resettlement in development: From third world to the world of the third. London and New York: Routledge.

- Coleman, J. S. 1988. Social Capital in the creation of human Capital. American Journal of Sociology 94:S95–S120. doi:10.1086/228943.

- Colson, E. 1971. The social consequences of resettlement. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Corntassel, J. 2008. Toward sustainable self-determination: Rethinking the contemporary indigenous-rights discourse. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 33(1):105–32. doi:10.1177/030437540803300106.

- de Wet, C. 2009. Does development displace ethics? The challenge of forced resettlement. In Development and dispossession, ed. A. Oliver-Smith. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Douglas, M. 1992. Risk and blame: Essays in cultural theory. London: Routledge.

- Downing, T. E. 1996. Mitigating social impoverishment when people are involuntarily displaced. In Understanding impoverishment: The consequences of development-induced displacement, ed. C. McDowell. Providence, RI: Berghahn Books.

- Downing, T. E., and C. Garcia-Downing. 2009. Routine and dissonant cultures: A theory about the psycho-socio-cultural disruptions of involuntary displacement and ways to mitigate them without inflicting even more damage. In Development & dispossession: The crisis of forced displacement and resettlement. ed. A. Oliver-Smith. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Ekblom, A., M. Notelid, and R. Witter. 2017. Negotiating identity and heritage through authorised vernacular history, Limpopo national park. Journal of Social Archaeology 17(1):49–68. doi:10.1177/1469605316688153.

- Gengenbach, H. 1998. I'll bury you in the border!': Women's land struggles in post-war facazisse (magude district), Mozambique. Journal of Southern African Studies 24(1):7–36. doi:10.1080/03057079808708565.

- Harries, P. 1994. Work, culture and identity: Migrant labourers in Mozambique and South Africa c. 1860–1910. London: James Currey. doi: 10.1086/ahr/100.5.1641.

- Hirschon, R. 2000. The creation of community: Well-being without wealth in an urban Greek refugee locality. In Risks and reconstruction: Experiences of resettlers and refugees, eds. M. M. Cernea and C. McDowell. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Junod, H. 1962. Life of a South African tribe. Social life, part 1. New Hyde Park, NY: University Books.

- Lund, C. 2016. Rule and rupture: State formation through the production of property and citizenship. Development and Change 47(6):1199–228. doi:10.1111/dech.12274.

- Lund, C. 2018. Predatory peace. Dispossession at Aceh’s oil palm frontier. The Journal of Peasant Studies 45(2):431–52. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2017.1351434.

- Mahapatra, L. K., and S. Mahapatra. 2000. Social re-articulation and community regeneration among resettled displacees. In Risks and reconstruction: Experiences of resettlers and refugees, eds. M. M. Cernea and C. McDowell. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Mascia, M. B., and C. A. Claus. 2009. A property rights approach to understanding human displacement from protected areas: The case of marine protected areas. Conservation Biology 23(1):16–23. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01050.x.

- McLean, J., and S. Straede. 2003. Conservation, relocation, and the paradigms of park and people management – A case study of Padampur villages and the royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Society and Natural Resources 16(6):509–26. doi:10.1080/08941920309146.

- Milgroom, J. 2017. Orphans of the land. http://www.orphansoftheland.org/.

- Milgroom, J., and K. E. Giller. 2013. Courting the rain: Rethinking seasonality and adaptation to recurrent drought in semi-arid Southern Africa. Agricultural Systems 118:91–104. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2013.03.002.

- Milgroom, J., K. E. Giller, and C. Leeuwis. 2014. Three interwoven dimensions of natural resource use: quantity, quality and access in the great Limpopo transfrontier conservation area. Human Ecology 42(2):199–215. doi:10.1007/s10745-013-9635-3.

- Patton, M. Q. 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury City, CA: Sage Publications.

- Peluso, N. L. 1996. Fruit trees and family trees in an anthropogenic Forest: Ethics of access, property zones, and environmental change in Indonesia. Comparative Studies in Society and History 38(03):510–48. doi:10.1017/S0010417500020041.

- Ribot, J. 2007. Representation, citizenship and the public domain in democratic decentralization. Development 50(1):43–9. doi:10.1057/palgrave.development.1100335.

- Ribot, J., A. Chhatre, and T. V. Lankina. 2008. Special issue introduction: ‘the politics of choice and recognition in democratic decentralization’. Conservation and Society 6(1):1–11. http://www.conservationandsociety.org/text.asp?2008/6/1/1/49197

- Ribot, J. 2014. Farce of the commons: Humor, irony, and subordination through a camera’s lens. Research Report No 2. Exakta, Malmö: Swedish International Centre for Local Democracy. https://icld.se/static/files/forskningspublikationer/farce-of-the-commons-ribot-report-2-low.pdf

- Ribot, J., and N. L. Peluso. 2009. A theory of access. Rural Sociology 68(2):153–81. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x.

- Rogers, S., and M. Wang. 2006. Environmental resettlement and social dis/re-articulation in Inner Mongolia, China. Population and Environment 28(1):41–68. doi:10.1007/s11111-007-0033-x.

- Schmidt-Soltau, K. 2003. Conservation–related resettlement in Central Africa: Environmental and social risks. Development and Change 34(3):525–51. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00317.

- Scudder, T., and E. Colson. 1982. From welfare to development: A conceptual framework for the analysis of dislocated people. In Involuntary migration and resettlement, eds. A. Hansen and A. Oliver-Smith. Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Shipton, P., and M. Goheen. 1992. Understanding African land-holding: Power, wealth, and meaning. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 62(3):307–25. doi:10.2307/1159746.

- Sikor, T., and C. Lund. 2009. Access and property: A question of power and authority. Development and Change 40(1):1–22. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01503.x.

- Vanden Berg, T. M. 1999. We are not compensating rocks': Resettlement and traditional religious systems. World Development 27(2):271–83. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00138-7.

- Wang, C., and M. A. Burris. 1997. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior 24(3):369–87. doi:10.1177/109019819702400309.

- Watts, M. J., and H. Bohle. 1993. The space of vulnerability: The causal structure of hunger and famine. Progress in Human Geography 17(1):43–68. doi:10.1177/030913259301700103.

- WCD. 2000. Dams and development: A new framework for decision making. London: Earthscan Publications Ltd.

- Witter, R. 2010. Taking their territory with them when they go: mobility and access in Mozambique's Limpopo National Park. PhD dissertation, Anthropology, University of Georgia, Athens.

- Witter, R., and T. Satterfield. 2014. Invisible losses and the logics of resettlement compensation. Conservation Biology 28(5):1394–402. doi:10.1111/cobi.12283.