Abstract

Fisheries’ supply of ecosystem services depends on recruiting, maintaining and—in cases of overfishing—preventing fishers’ participation. Participation is influenced by fishers’ levels of job satisfaction and a variety of motivations that cannot be reduced to income size. Previous research on fishers’ job satisfaction has applied Maslow’s hierarchy of basic, socio-psychological and self-actualization needs. Using these as three categories of co-existing rather than hierarchical needs, we investigate Swedish fishers’ motivations for considering fisheries exit. Our results suggest that more than half of fishers are considering exiting and that they identify conflicts with seals (31%), environmental policies (17%) and performance of government agencies (16%) as their main reasons. These motivations, we argue, impact simultaneously basic, socio-psychological and self-actualization needs. Accordingly, fishers’ motivations for participation-exit decisions are not solely, and may not be primarily, monetary. A better understanding of fishers’ motivations, particularly non-monetary ones, would improve fisheries management.

Introduction

Fisheries can deliver important ecosystem services to countries with fishing grounds in their territorial waters like Sweden. Food and food security, employment, economic diversification, place identity and ecological knowledge are among those services (FAO Citation2018; Garavito-Bermúdez Citation2018; Waldo and Lovén Citation2019). Yet, fishing is highly risky and dangerous, with hazards connected to working at sea and unpredictable economic returns (Anna et al. Citation2019; Holland, Abbott, and Norman Citation2020). Despite this, fishing attracts many participants worldwide who are driven by economic interests but also a variety of psychological and socio-cultural motivations that cannot be reduced to income provision (Anderson Citation1980; Pollnac and Poggie Citation1988; Cinner, Daw, and McClanahan Citation2009; Pita et al. Citation2010; Muallil et al. Citation2011; Sweke et al. Citation2016; Daw et al. Citation2012). Active commercial fishers’ reasons for continuing to participate in or exiting a fishery are likewise influenced by monetary (income) and non-monetary motivations linked to general job satisfaction (Cinner, Daw, and McClanahan Citation2009; Pita et al. Citation2010; Crosson Citation2015). Fisheries’ supply of ecosystem services depends on recruiting, maintaining and—in cases of overfishing—preventing fishers’ participation, yet research on motivations influencing individual fishers’ participation-exit decisions is still very limited (Tidd et al. Citation2011; Crosson Citation2015; Daw et al. Citation2012).

Most fisheries researchers and managers agree that “managing fisheries is about managing people” (Hilborn Citation2007; see also Boyd Citation2014), or perhaps even better “managing with people.” Understanding fishers’ motivations for engaging in their occupation is relevant for this management. As others have reported, too much emphasis on fishers’ economic motivations, and a narrow vision of the fisher as profit-maximizer, have led to ineffective management and fishing policies worldwide. Economic models, for instance, have been frequently used to predict fishers’ exit rates when managers seek to rebuild overexploited fish stocks (Squires Citation2010; Carothers and Chambers Citation2012). Buyback or decommissioning (scrapping) programs for fishing vessels, licenses and gears are common management tools based on such models (Blomquist and Waldo Citation2018). Yet, these programs have had limited success because they fail to consider factors other than economic ones (Holland, Gudmundsson, and Gates Citation1999; Teh, Hotte, and Sumaila Citation2017). For example, a three-year buyback program in the Atlantic Canadian inshore lobster fishery spent around US$5 million to purchase almost 1,500 licenses from fishers, but at least 40% of the fishers who sold their licenses continued fishing, choosing to migrate effort to another fishery (thus increasing pressure there) rather than quit (Holland, Gudmundsson, and Gates Citation1999). Fishers are hence more than “profit maximizers”: they are part of social units that influence their choices, and exhibit a diversity of behaviors driven by monetary and non-monetary concerns, which directly impacts the effectiveness of fishing policies (Boonstra and Hentati-Sundberg Citation2016; Seara, Pollnac, and Poggie Citation2017), especially those derived from utilitarian economic models.

Motivations for fishers’ participation-exit decisions can be linked to demographic factors and individual perceptions and preferences. Age, education, household size and lack of experience outside fishing affect participation-exit decisions, with older, less educated, lonely-living and specialized fishers showing higher levels of reluctance to exit (Pollnac and Poggie Citation1988; Pita et al. Citation2010; Muallil et al. Citation2011; Fernandes Citation2012; Sweke et al. Citation2016). Ethnicity and religion can also be relevant, as in the case of Buddhists in Thailand who in comparison to Muslims were less reluctant to exit fisheries (Panayotou and Panayotou Citation1986). Individual perceptions and preferences can be understood in terms of occupational attachment, identity and job satisfaction. Among scholars studying fishers’ job satisfaction, anthropologists Robert Pollnac and John Poggie were pioneers during the 1970s (Binkley Citation1995). They proposed 22 variables based on US west-coast fishers’ perceptions of what is “good and bad” about fishing (see Pollnac and Poggie Citation1988). These scholars drew on Maslow’s theory of the hierarchy of needs (Maslow Citation1954; Maslow Citation1968) to analyze these variables (Seara, Pollnac, and Poggie Citation2017). From this perspective, commercial fishing can be depicted as addressing “Basic Needs (Maslow’s physiological and safety needs), Social and Psychological Needs (Maslow’s love and belongingness needs), and Self-actualization” (Seara et al. Citation2017, 1628). The “basic” level of needs is food and income to, for example, pay rent or health insurance costs. Socio-psychological needs refer to fishing’s contribution to belongingness and esteem, being a respected person and/or part of a community or group of fellow workers. At the self-actualization level, fishing offers opportunities to be creative and use individual skills, and/or enables a desired “way of life” supporting one’s “peace of mind.” However, fishing can also weaken job satisfaction by its intrinsic unpredictability, demands on physical strength and long working hours away from home and family (see Pollnac and Poggie Citation1988; Gatewood and McCay Citation1990; Johnsen and Vik Citation2013; Crosson Citation2015).

Job attachment and satisfaction are important factors for individual wellbeing in any occupation, but seem to be particularly important in fishing. Possibilities for adventure, working in nature, unique unforgettable experiences and the “thrill of the hunt” are aspects of fishing that are rarely delivered by other occupations (Pollnac and Poggie Citation2006; Seara, Pollnac, and Poggie Citation2017). It is fishing’s ability to meet fishers’ socio-psychological and self-actualization needs that results in what Anderson (Citation1980) calls the “worker satisfaction bonus.” Regardless of their income levels, at least some fishers will exit a fishery only when fishing no longer delivers self-actualization (Pollnac and Poggie Citation2008). Other scholars have pointed to socio-psychological and self-actualization dimensions by describing fishing as a “way of life” or “lifestyle” rather than just an occupation (Jentoft et al. Citation2011; Carothers and Chambers Citation2012; Urquhart, Acott, and Zhao Citation2013). In other words, an individual’s decision to participate in or exit fishing depends on the values that the fisher attaches to the three categories of needs plus the extent to which they are met.

In this research, we use basic, socio-psychological, and self-actualization needs to investigate Swedish fishers’ decisions to exit or continue fishing, drawing on a survey sent to all holders of a commercial fishing license. We see basic, socio-psychological, and self-actualization needs not as a hierarchy but as three coexisting categories. Access to adequate food and shelter is, of course, a fundamental condition for human life. Once an economic level required to sustain human life is met, however, individuals and groups have very different notions concerning the level of economic resources they “need” to live. Economic needs are thus not necessarily more “basic” than other needs. An individual fisher may prioritize one category over another, depending on her or his circumstances. A fisher’s total job satisfaction will however depend on fishing’s ability to meet all three types of needs.

Fisheries policies, we contend, could usefully be informed by a deeper understanding of fishers’ participation-exit motivations. In a country like Sweden, where nearly 24,000 fishers have exited fisheries over the 20th century (Krogseng Citation2016), and high numbers of fishers continue exiting in the present century (Waldo and Blomquist Citation2020), research of this type is urgent. In this study we address three questions, namely, (1) What are the current motivations for participation-exit choices among Swedish fishers? (2) How are these motivations related to theoretical categories of needs and job satisfaction? and (3) How might Swedish fisheries management benefit from a better understanding and consideration of fishers’ participation-exit motivations? We turn first to the context and background for our research, providing a brief overview of fishing participation in Sweden and challenges for fisheries management.

Brief summary of Swedish fisheries participation and fisheries policies

Sweden today does not fall into the category of “fishing country,” as do other Nordic countries such as Iceland and Norway. Yet fishing was a major activity on Swedish coasts in the past. A herring fishery of unprecedented size in European history developed on the west coast of Sweden during the latter half of the 18th century (Poulsen et al. Citation2007). On the east coast (Baltic Sea and the Sound), fishing sustained many communities and was for centuries part of local ways of life and distinctive place identity (Arias-Schreiber et al. Citation2017; Vesterberg Citation2019; Björkvik et al. Citation2020). In the first half of the 20th century, the number of fishers in Sweden was estimated at around 25,000 (Krogseng Citation2016). This number has steadily declined (Neuman and Piriz Citation2000; Waldo and Blomquist Citation2020) and in 2017, the number of Swedish fishers was 1,449 and the fleet had 911 active fishing vessels (STECF Citation2019).

Declining numbers of Swedish fishers in the last decades can be partially explained by Sweden joining the European Union (EU) in 1995 and Sweden’s 2009 introduction of a system of Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs)Footnote1 for pelagic species (herring, sprat and mackerel). Through voluntary vessel decommissioning and scrapping programs, the EU has been reducing fishing capacity, especially after the 2003 Common Fishery Policy reform (Lindebo, Frost, and Løkkegaard Citation2002; Villasante Citation2010). In Sweden, scrapping programs and the ITQ system in the large-scale pelagic fishery were used to reduce fleet size and improve economic profitability, specifically in the pelagic fishery for which fish stocks were not considered overfished at the moment of the policy change (Blomquist and Waldo Citation2018). However, fishers who scrapped their vessels and the ones who sold their quotas in the ITQ system did not all quit the fishery sector. In what has been described as the “spill-over effects on non-targeted fisheries of scrapping and ITQ policies,” many of these fishers reinvested in new vessels and started fishing species that were not managed under closed quota systems in Swedish waters (Blomquist and Waldo Citation2018) or joined the EU distant-water fishing fleet.

Between 2008 and 2017, the Swedish fleet’s average yearly reduction rate has been slightly higher than EU rates. Over this period the EU fleet reduced by an average of 2% per year (EC Citation2017) and the Swedish fleet by 3% (Waldo and Blomquist Citation2020). This decline occurs at the same time that Swedish government agencies committed to fostering a “sustainable and viable fishing industry,” recommended that citizens consume fish at least twice a week, and identified the provision of a “nutritious and sustainable food alternative” as a goal of the fishing industry, where the term “alternative” refers to an alternative to meatFootnote2. Industrial meat production’s disturbing environmental impacts, its controversial human health consequences, and concerns about animal welfare, all contribute to this commitment. In addition, new consumption preferences for local products and a “quality turn” (Hultman et al. Citation2018) have affected attitudes toward the fishing industry. Nordic countries are undergoing major changes in food and drink markets “with large-scale, industrial, environmentally-irresponsible food systems being gradually supplanted by non-industrial, premium-priced, specialized products supplied by small-scale producers, distributors and network organizations” (Hultman et al. Citation2018, 25). Fisheries have the potential to meet this emergent demand for healthy, nutritious products, with locally-caught fish delivering the qualities characteristic of this contemporary trend.

Swedish authorities are well aware of recent changes in food preferences and the public demand for local and high-quality products. The current national strategy for the fishing industry articulates three strategic visions, one of which is: “Swedish commercial fishing supplies top quality raw materials to consumers and the fish processing industry” (Jordbruksverket and HaV Citation2016, 10). However, for this fishing industry to be sustainable and supply market demands for “food from somewhere” (Campbell Citation2009), challenging and radical policy changes will be required. In 2018, of the eleven most important species fished and farmed by Swedish operators, just about 17% reached Swedish consumers in the form of directly edible seafood (Sundblad et al. Citation2020) and 60–80% of landings were processed to fishmeal (Borthwick, Bergman, and Ziegler Citation2019). The same year, from 66 fish stocks landed, at least 41% (n = 27) were fished unsustainably (Bryhn et al. Citation2020). Thus, if Swedish fisheries are to become sustainable and viable, at least three issues must be addressed: (a) the proportion of fishers quitting their occupation, and specifically the coastal fishers who could supply demands for high-quality, local, non-industrial seafood, (b) the use of landings for fishmeal, and (c) the unsustainable exploitation of many stocks currently fished. Here we focus on the rate of fisheries exit, where insights concerning fishers’ participation-exit motivations could inform Swedish authorities’ efforts to achieve a sustainable fishing sector.

Methods

Empirical data was collected from a self-administered voluntary questionnaire sent by post to all holders of a Swedish commercial fishing license connected to a vessel (fiskelicensinnehavare)Footnote3. A total of 835 questionnairesFootnote4 were mailed in June 2019 together with a postage-paid return envelope. The questionnaire, which is part of a larger research project, was broad in nature. It began by asking the fishers about their plans to remain in or leave commercial fishing as an occupation and, for those who replied they had quit or were considering quitting, their reasons for fisheries exit. A list of potential reasons was provided by the survey administrators, which included the authors, another fisheries researcher, and two civil servants working with municipal and regional fisheries. This list, which did not include income or profitability as a choice, as well as the questionnaire in its entirety, had been vetted by a group of coastal fishermen before it was finalized. Respondents were asked to choose one or more reasons for fisheries exit among the following alternatives: state of fish stocks, fish availability, a market that prioritizes quantity over quality and a better price, regulations (in relation to marketing catches, fishing licenses for diversification or the simultaneous use of different fishing gears), requisites for purchase of fishing rights, current environmental movements/environmental politics and seals. The final choice was “other” with a comment encouraging respondents to explain what they meant.

For data analysis, we calculated frequencies (numbers of occurrences) of nominal (categorical) data and applied the chi-square test of independence to assess their statistical significance. Frequencies were then represented as a percentage of the pool data. Text provided in the open choice was coded and sorted using emic categories until thematic saturation was reached, a method often referred to as “grounded theory” (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967). The results from this content analysis were similarly used to calculate frequencies and percentages. We use direct textual quotations in our discussion to present examples where they reflect the sentiments of a cluster of respondents and when counterexamples were absent.

Forty-two percent (n = 351) of the license holders responded and sent back the questionnaire. We separated fishers’ responses into three classes according to the fishing fleet segment to which they belonged: fishers from the large-scale fishery (LSF), fishers from the coastal or small-scale fishery (SSF) and coastal trawlers (CT). As per the EU definition, an LSF was defined as working on a vessel larger than 12 m in length, a coastal SSF as working on a vessel less than 12 m long and operating passive fishing gears, and a CT as working on a vessel less than 12 m long and fishing with a non-passive fishing gear (usually a trawl)Footnote5. Relevant to this classification is scholarship reporting that the small-scale fisheries fleet is working under unprofitable conditions while the large-scale fleet is profitable (Waldo and Blomquist Citation2020), and that coastal fishers (SSF plus CT), who commonly land daily, could potentially supply top-quality fish to local markets (Knutson Citation2017; Björkvik et al. Citation2020). Fishers’ responses were additionally divided, according to their geographical location of operation, between fishers from the west coast and fishers from the Baltic Sea (including the Sound), due to differences in their behavior, fishing styles, average age and economic interests (see Boonstra and Hentati-Sundberg Citation2016; Björkvik et al. Citation2020; Waldo and Blomquist Citation2020). After categorizing fishers’ responses, we excluded 52 surveys from fishers who did not provide information on vessel size or gear (7 surveys), who reported operating both passive nets and active trawlers in vessels less than 12 m long (32 surveys) and/or who operated more than one vessel belonging to different fleets (13 surveys).Footnote6

Given a population size of 835 fishers, a sample size of 299 (351 minus 52) carries a 95% likelihood that our results accurately reflect the motivations of the Swedish fishing license holders with a 5% margin of error (see Cochran Citation1963). The number of fisher’s responses according to fishing fleet and location of operation is presented in . Among the 299 respondents, 79% operated a vessel less than 12 m in length (SSF plus CT), a figure slightly higher than the proportion of fishers with this vessel size (72% of vessels or 660 of 911) in 2017 (see STECF Citation2019). Sixty percent of the respondents fished in the Baltic Sea, which in 2017 hosted approximately 54% of the active Swedish fleet (see Waldo and Blomquist Citation2020, 5). SSF from the Baltic Sea had a significantly higher rate of response in comparison to fishers from other fishing fleets and locations (p < .05).

Table 1. Analysis of responses of 299 surveys from a total of 831 fishing license holders in Sweden according to fishing fleet and fishing location of operation.

Results

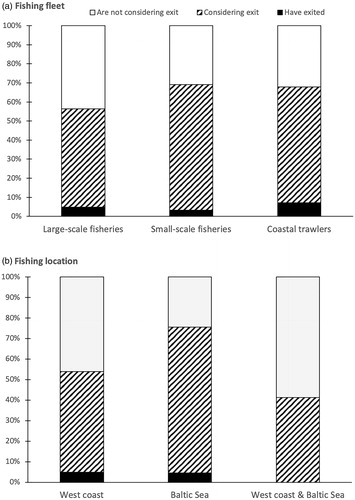

From 299 respondents, 4% (n = 13) had exited fisheries, 62% (n = 185) were considering exit, and 34% (n = 101) had no plans to stop fishing. Six of the 13 fishers who had exited fishing were SSF, one from the west coast and five from the Baltic Sea. Among respondents considering exit, the majority belong to the small-scale fisheries fleet from the Baltic Sea, while the majority who had no plans to exit the fishery were LSF operating in both the west coast and the Baltic Sea (). With regard to differences between fishers that had exited, have exit intentions, and have no exit intentions, no significant differences were found between fishing fleets, while the percentages of fishers with exit intentions was significantly higher among those operating in the Baltic Sea (p < .05).

Figure 1. Survey respondents that have exited, are considering exit or are remaining in fisheries according to fishing fleet (a) and fishing location (b) in Sweden.

Fishing license holders who had exited fishing

Among fishers who had exited, conflicts with seals was the most commonly given reason, followed by government regulations and environmental movements and policies (). A higher percentage of fishers from the Baltic Sea selected conflicts with seals than west-coast fishers, while west-coast fishers gave more importance to environmental policies and the need to buy fishing rights (). Six fishers provided their own additional reasons for having quit; these were corruption of the authorities, sickness, EU policies, the ban on driftnets and profitability (see Appendix 1).

Table 2. Reasons selected from a list of given alternatives for having exited or considering fisheries exit among Swedish holders of a commercial fishing license by fishing fleet (LSF: large-scale fisheries; SSF: small-scale fisheries; CT: coastal trawlers).

Table 3. Reasons selected from a list of given alternatives for having exited or considering fisheries exit among Swedish holders of a commercial fishing license by fishing location.

Fishing license holders considering fisheries exit

Pooled together (n = 185), fishers selected conflicts with seals, environmental movements and policies, and government regulations as the most common reasons for considering fisheries exit (). With regard to these three reasons, no significant differences were found between the fishers who had exited and those considering exit in relation to fishing fleet or fishing location (p < .05). Fishers in the Baltic Sea or those fishing in both the Baltic Sea and the west coast selected seals in higher percentages. Environmental movements and policies were selected as the most important reason for considering fisheries exit among fishers from the west coast ().

Ninety-one fishers (49%) who were considering fisheries exit supplied additional reasons to the list of alternatives given in the questionnaire. These fishers added advanced age as an important reason, followed by the attitude and performance of the Swedish agency in charge of fisheries management, too many controls and bureaucratic demands—including paper work, reporting, payments/fees and even use of computers—and conflicts with cormorants (). Age was mentioned by the majority of CT, LSF and by fishers from the west coast; fishers belonging to the large-scale fleet gave the same weight to age and to bureuaucratic demands. Voluntary supplied reasons for considering exit were more diverse among Baltic Sea fishers.

Table 4. Additional reasons (respondent provided) for considering fisheries exit among Swedish holders of a commercial fishing license by fishing fleet (LSF: large-scale fisheries; SSF: small-scale fisheries; CT: coastal trawlers) and fishing location.

Discussion

While fishers generally exhibit an optimistic and positive attitude toward their future (Gatewood and McCay Citation1990; Sweke et al. Citation2016; Anna et al. Citation2019), our data suggests that a large proportion of commercial fishing license holders in Sweden—the majority of them small-scale fishers in the Baltic Sea—are considering fisheries exit. These findings are consistent with a recent study showing that Swedish fishers from the Baltic Sea had higher rates of fishing exit than fishers in Finland, Germany, Estonia, and Poland (Svels et al. Citation2019). While our study does not allow us to address direct links between intentions (considering quitting fishing) and actions (real-life exit), our 62% figure of fishers considering exit indicates low levels of job satisfaction and poor prospects for fishers’ future wellbeing (Pollnac and Poggie Citation1988; Fernandes Citation2012; Crosson Citation2015). This intimates a need to review current fisheries management, especially in the Baltic Sea.

Conflicts with seals and cormorants appear to be a key factor affecting participation-exit choices for fishers in Sweden. This finding is new to the literature on fishers’ job satisfaction. Looking at this result in relation to the tripartite classification of needs, we find that the seals-cormorant issue engages all three categories of needs (basic, socio-psychological, and self-actualization). The consumption of fish by seals and cormorants decreases fish stocks and subsequently fishers’ potential income, e.g., “basic” needs.Footnote7 However, seals and cormorants also impinge on socio-psychological needs, as is clear from comments such as “a single seal is more important than a fisher.” Complaints that the authorities “don’t take the seal-cormorant problem seriously” suggest that the fishers feel the authorities do not adequately respect or value fishers or the work they do. Further, seals and cormorants expose fishers to conflicting feelings of love for nature (the “joy” of working at sea) and detestation for nature (e.g., seals and cormorants). Finally, fishers’ frustration about the seals-cormorant problem negatively influences their experience of themselves as among the few who have the skills and knowledge for handling the challenges associated with working at sea. As Gatewood and McCay (Citation1990) reported, “pitting skill against nature” is a component of self-actualization, and several authors have suggested that self-actualization could be more significant than other needs categories for fishers (Gatewood and McCay Citation1990; Pollnac and Poggie Citation2006, Citation2008; Pollnac, Seara, and Colburn Citation2015). If, as we suggest, problems with seals and cormorants engage all three categories of needs, this sheds light on why fishers in Sweden consider economic compensation for the seals-cormorant problem to be an inadequate, temporary solution, and advocate for reducing the numbers of these animals by hunting as a much-preferred measure (Svels et al. Citation2019; Waldo et al. Citation2020). SSF and CT from the Baltic Sea seem more concerned with seals and cormorants than SSF or LSF in the west coast. Seals and cormorants compete for more of the species that fishers target in the Baltic Sea such as cod, whereas some west-coast SSF targeting shrimp, langoustine and lobster, are not affected by these predators.

Fishers identified also government regulations regarding the use of gears and the overall performance, bureaucracy, and even “corruption” of the Swedish fisheries management authority, as factors influencing their participation-exit decisions. Swedish fishers’ views of government authorities appear to be affecting their job satisfaction, and these fishers link increasing amounts of regulation to official performance. Comments concerning “the authorities’ lack of flexibility and understanding,” “bureaucratic hassles,” and “authorities who only prevent us from fishing” make these connections clear. Furthermore, technical regulations for fishing in the Baltic Sea have steadily increased over the last decades (Hentati-Sundberg and Hjelm Citation2014) and fishers mentioned the ban of driftnets and the short season for the eel fishery as examples of these troublesome regulations. Strict quotas and discard bans affect landing volumes, and so basic needs. However, several fishers stated also that fisheries authorities did not listen enough to fishers. One wrote, “The authorities’ inability and unwillingness to listen to ordinary people [is the biggest problem in commercial fishing]!” Another stated, “I feel like I am treated as a criminal every time I am approached by an official.” These comments articulate socio-psychological needs related to respect, recognition, and appropriate treatment. An additional psychological stress may arise because Sweden is recognized as a country whose citizens trust in their government agencies and ranks fourth among the countries with lower corruption perception indices.Footnote8 Official performance may thus generate conflicting feelings concerning trustworthy, “good” officials and disrespectful, corrupt “bad” officials. Levels of regulation also impinge on these fishers’ self-actualization needs by reducing fishers’ opportunities to pit their skills against nature (cf. Pollnac, Seara, and Colburn Citation2015). Many fishers complain that they cannot decide when to switch fishing gears or fishing grounds because of regulations about which species to catch, which gears to use, and when, where and how much to catch. Such restrictions decrease fishers’ control over the “challenge of the job,” a crucial component of self-actualization. In short, as in the case of seals and cormorants, fishing restrictions and official performance impinge simultaneously on basic, socio-psychological and self-actualization needs.

We draw a similar conclusion concerning the threats associated with environmental movements and policies. Certainly, restrictions on fishing effort, which are linked to environmental goals, have economic consequences for fishers. However, a number of Swedish fishers also claim that their knowledge and experience are not respected by environmentally-oriented politicians, officials or activists. This is clear from comments such as: “I get crazy over all those self-appointed “experts” in the environmental movement” or “I am glad I don’t have that much longer to work as a commercial fisher when politicians, bureaucrats, and environmental muppets [miljömuppar] have completely ruined the joy of working. In the past we had a freedom in fishing, now we are monitored 24 hours per day, a surveillance level that North Korea would be proud of!” and so on. Such conflicts likely generate additional psychological stress as fishers, who regard themselves as stewards of natureFootnote9 find themselves in opposition to pro-nature activists. These fishers also find it difficult to understand and accept why the government supports the environmental movement’s interests and the supremacy of scientific knowledge which is, in their view, often biased. Fishers’ local knowledge—which is far richer, context-specific and more useful—is not valued, and regulations prevent them from using it to optimize their landings’ quantity and quality (see Säwe and Hultman Citation2012).

While many fishers identified environmental movements and politics as a reason to considering quitting, LSF and west coast fishers did it in larger numbers. This may be related to sector-specific worries. As one official from the Swedish fisheries agency related, in 2009 a large national marine park was established on the west coast, which may be triggering fears among the predominantly west-coast LSF, that more protected areas could be set up in the future.

None of the fishers who have exited and few of those considering exit selected the state of fishing stocks as a reason for fisheries exit. Here we see possible explanations related to the three categories of needs. Fishers might be reluctant to talk about decreasing fish stocks, fearing that this information will be used against them by authorities, for example to close marine areas or enact other types of restrictions impacting their landings and income (Johnson Citation2011). Fishers may also understand fluctuations in fishing stocks as a natural process and as one of the challenges that they face in their “battles” at sea. Their knowledge and capacity to adapt to fish stock changes through switching gears and fishing grounds are part of what it means to be a commercial fisher. In other words, reduced fish stocks negatively affect “basic” needs, but they do not threaten fishers’ self-actualization, and may, indeed, enhance it by increasing the challenge of fishing and satisfaction with a successful catch. CT were more concerned than fishers from the other two fleets regarding fish stocks. This could be a result of declining cod stocks, which is their main target species, particularly in the southern Baltic.

While in general we see a low percentage of fishers who regarded access to fish stocks as a reason for considering exit, somewhat more SSF identified access to fish stocks as problematic, whereas LSF showed a positive bias regarding the need to buy fishing rights. SSF target a larger variety of species than their large-scale counterparts who target herring and sprat and can travel farther distances to fill up their holds. SSF are thus more affected by limited access to fish stocks and showed also a larger diversity of concerns and motivations in comparison with the other two fleets. Fishers from the SSF fleet also do not fish on species with ITQs, as opposed to large-scale fishers, who in the pelagic fishery must buy fishing rights.

Swedish fishers seem to be also less troubled by market issues when it comes to fisheries exit. Relative satisfaction with the market can be explained at least in part by a continuous incremental increase in the price of seafood over the last decades in Sweden, with the exception of the price of cod, which has remained at the same level since 2004 (see Davelid, Rosell, and Burman Citation2014, 27,28). Cod is a main target species in the Baltic Sea, yet only 7% of Baltic Sea fishers chose market-related reasons for fisheries exit, in comparison to 11% of fishers from the west coast. Moreover, from the 97 fishers who added their own motivations for quitting to our question (in which profitability was not listed as an alternative), only one large-scale fisher from the west coast mentioned profitability, along with three other factors, as the reason s/he considered exit (see Appendix 1).

Income’s role as a factor triggering fisheries exit becomes clearer when we examine data concerning fisheries’ profitability in relation to fleet segment. Baltic Sea fishers are mostly small-scale, whereas west-coast fishers are mostly large-scale. Levels of profitability for Sweden’s small-scale fishery have been declining over the last fifteen years (see Waldo and Blomquist Citation2020, 8, 9; Davelid, Rosell, and Burman Citation2014, 30, 31). By contrast, the large-scale fishery from the west coast is known to be profitable. After one and a half decades of minimal or negative profitability, SSF and CT in the Baltic Sea who considered profitability essential to job satisfaction have probably already exited. SSF who, in interviews with journalists, describe fishing as “a lifestyle that one does not easily give up” (Samuelsson Citation2015; see also Hinderson Citation2014; Danhall Citation2020), lend plausibility to this hypothesis, as does recent scholarship that views the Baltic Sea small-scale fishery as a provider of “other values rather than profits” (Waldo and Blomquist Citation2020, 15). SSF may have lower monetary expectations than west-coast fishers, and since decreasing income does not impact socio-psychological or self-actualization needs (Pollnac and Poggie Citation2006; Pollnac, Seara, and Colburn Citation2015), they may not see income size as a reason to exit fishing, as long as they have a supply of financially-adequate alternatives, for example through the salary of a spouse. In cases where fishers live under poverty conditions, however, basic needs could be more important for participation-exit decisions (see Fernandes Citation2012).

Advanced age was a reason that fishers, especially CT and LSF from the west coast, supplied for considering fisheries exit. These results are consistent with observations by Waldo and Blomquist about the reluctance of Baltic Sea SSF to retire and stop fishing (Citation2020, 15). Fishers from the west coast retire at higher rates, which points to a lower average age among fishers there in comparison to the Baltic Sea (Waldo and Blomquist Citation2020, 15). Why age-related concerns might play a bigger role in west coast and LSF cannot be fully addressed by our data. Exactly how age relates to the capacity of fishing to fill the three categories of needs, or to the higher levels of profitability deserves further research.

Conclusions

This study is the first scholarly investigation of Swedish fishers’ motivations for fisheries participation and exit. Our methodology and research tool cannot produce conclusive answers about these fishers’ job satisfaction; more research is needed to fully understand Swedish fishers’ participation-exit behavior. Nevertheless, our data suggest that a large proportion of fishing license holders are considering fisheries exit, particularly SSF from the Baltic Sea. Conflicts with seals and cormorants, the performance of and regulations from government authorities, and the environmental movement and environmental policies are the most significant factors identified by this group as negatively impacting their levels of job satisfaction. These issues, as we have shown, simultaneously impinge on fishers’ basic, socio-psychological, and self-actualization needs.

How might our findings about the motivations of Swedish fishers be useful for fisheries management? Taking the example of seals and cormorants, fishers in Sweden have good reasons to be frustrated: authorities have taken minimal mitigation measures since this problem first became evident back in the early 1990s (cf. Lunneryd and Königson Citation2017). While compensation for the damage caused by these predators might address fishers’ basic needs, such a policy ignores socio-psychological and self-actualization needs, and so might not be adequate. Another example is the Swedish fisheries authorities’ efforts to promote tourism in connection with coastal fisheries. Policies to divert fishers to occupations in tourism—an idea touted in Sweden’s national strategy for commercial fishing—may bring economic rewards to fishers, but ignore self-actualization needs and run counter to fishers’ socio-psychological needs for respect and esteem as fishers. This suggests they are unlikely to succeed.

A lack of attention to fishers’ socio-psychological and self-actualization needs by the authorities may contribute to fishers’ feelings of discomfort and mistrust in the governance system. Plans to develop less centralized and more participatory modes of fisheries management (as promoted by the EU with the establishment of Regional Advisory Councils in 2006)—such as co-management can be derailed by fishers who exhibit a lack of trust and willingness to cooperate. In addition, if it is fishing’s capacity to meet self-actualization needs that most fundamentally drives fishers’ participation (Pollnac, Seara, and Colburn Citation2015), then management forms which require fishers to engage in long, time-consuming discussions are unlikely to succeed, as they would decrease even further fishing’s ability to deliver job satisfaction. Under the present circumstances, using previous, localized successful fisheries co-management experiences in Sweden as models for change—as is often done—may lead to adverse results. From this perspective, our study lends urgency to the efforts of the Swedish authorities to improve the dialogue between managers and fishers before implementing co-management. Steps that showed the Swedish authorities’ awareness of fishers’ socio-psychological and self-actualization needs, such as addressing the conflict with seals and cormorants, respecting fishers’ knowledge, offering opportunities for closer collaboration between scientists and fishers, and allowing more flexibility for the SSF in the Baltic Sea would likely facilitate such discussions.

The question of why fishers are exiting or considering exiting fishing is important for achieving sustainable development goals related to responsible production and consumption in developed nations. Local fish consumption is perceived as a healthy alternative by an increasing number of consumers who are looking for an environmental-friendly protein supply (Campbell et al. Citation2014). Without an adequate number of SSF, local fish consumption has limited chances to develop, since the large-scale fishery is associated with industrial, corporate-owned, irresponsible production and fish for fishmeal reduction. Mantaining enough coastal fishers to supply local seafood markets requires addressing the basic, socio-psychological, and self-actualization needs that affect fishers’ participation-exit decisions.

Fisheries management that promotes a long-term environmentally, socially and economically sustainable fishing industry is urgently needed worldwide. As long as fisheries management is dominated by models of the fisher as an economically-driven profit-maximizing individual (Carothers and Chambers Citation2012), management goals are unlikely to be met. Sustainable fishing needs not only healthy fish stocks but also healthy fishers and fishing communities (Jentoft Citation2000) and as our results suggest—consistent with the literature on fishers’ job satisfaction—larger profits do not always translate to wellbeing. Knowledge about fishers’ motivations and job satisfaction can contribute to fisheries managers’ understandings of the benefits that fishers and communities derive from fisheries, and the potential usefulness of economic incentives or bioeconomic models to influence the numbers of people fishing. Fisheries management that integrates social goals with economic and ecological concerns to achieve sustainable development requires knowledge about how management decisions impact human wellbeing and how to maximize the societal benefits of fisheries.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge gratefully Madeleine Lundin and Vesa Tschernij from the Marint Centrum at Simrishamn Municipality for their always friendly support and engagement with our research. We also thank three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and suggestions to improve our manuscript.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For a description of the Individual Transferable Quotas system in fisheries please see Grafton (Citation1996) and Carothers and Chambers (Citation2012).

2 See Jordbruksverket and HaV (Citation2016) and the Swedish Agency for Food “Advice on fish and seafood,” https://www.livsmedelsverket.se/matvanor-halsa–miljo/kostrad-och-matvanor/rad-om-bra-mat-hitta-ditt-satt/fisk?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport.

3 According to the Swedish fisheries authority, Sweden offers two types of fishing license, one connected to a fishing vessel, called a fishing license (fiskelicens) and the other a personal fishing license (personlig fiskelicens). We sent the survey to the former group, using a list provided by the Swedish fisheries authority. Members of the latter group fish in inland waters under significantly different conditions from coastal and ocean fishers. In addition, “it is possible to be employed on a vessel without having a licence” (Blomquist and Waldo Citation2018, 42). For information on Swedish fishing licenses (in Swedish), see https://www.havochvatten.se/hav/fiske–fritid/yrkesfiske/licenser-och-tillstand/fiskelicens-for-yrkesfiskare.html. For information on Swedish personal fishing licenses, see https://www.havochvatten.se/hav/fiske–fritid/yrkesfiske/licenser-och-tillstand/personlig-fiskelicens.html.

4 A copy of the questionnaire (in Swedish) can be found online at http://hdl.handle.net/2077/64062, Appendix A.

5 The EU definition is the only official definition for small-scale fisheries in Sweden (Björkvik et al. Citation2020, 565).

6 The bulk of respondents who fished with both active and passive gears operated in the Bay of Bothnia. According to Björkvik et al. (Citation2020, 565–566), this is common in the area’s vendace fishery (Kalix siklöja). The survey did not ask respondents to provide information about species, but we were able to match nine fishers who employed both active and passive gears with species data: eight fished salmon, while cod, vendace, and eel had one fisher each.

7 Seals also cause economic losses by eating caught fish from fishing gears, damaging the gears (ripping the nets), eating fish which escape from ripped nets, and lowering the catch by frightening fish away (Lunneryd and Königson Citation2017).

8 See Corruption Perception Index 2019 at https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2019/results

9 See Björkvik (Citation2020) and O’Donnell, Hesselgrave, and Macdonald (Citation2015) for in-depth discussion, in Sweden and Canada respectively.

References

- Anderson, L. G. 1980. Necessary components of economic surplus in fisheries economics. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 37 (5):858–70. doi:10.1139/f80-114.

- Anna, Z., A. A. Yusuf, A. S. Alisjahbana, and A. A. Ghina. 2019. Are fishermen happier? Evidence from a large-scale subjective well-being survey in a lower-middle-income country. Marine Policy 106:103559. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103559.

- Arias-Schreiber, M., F. Säwe, J. Hultman, and S. Linke. 2017. Addressing social sustainability for small-scale fisheries in Sweden: Institutional barriers for implementing the small-scale fisheries guidelines. In The small-scale fisheries guidelines: Global implementation, ed. S. Jentoft, R. Chuenpagdee, M. J. Barragán-Paladines, and N. Franz. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Binkley, M. 1995. Risks, dangers, and rewards in the Nova Scotia offshore fishery. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Björkvik, E. 2020. Stewardship in Swedish Baltic small-scale fisheries: A study on the social-ecological dynamics of local resource use. Doctoral thesis, Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, Stockholm.

- Björkvik, E., W. J. Boonstra, J. Hentati-Sundberg, and H. Österblom. 2020. Swedish small-scale fisheries in the Baltic Sea: Decline, diversity and development. In Small-scale fisheries in Europe: Status, resilience and governance, ed. J. Pascual-Fernández, C. Pita, and M. Bavinck. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Blomquist, J., and S. Waldo. 2018. Scrapping programmes and ITQs: Labour market outcomes and spill-over effects on non-targeted fisheries in Sweden. Marine Policy 88:41–7. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2017.11.004.

- Boonstra, W. J., and J. Hentati-Sundberg. 2016. Classifying fishers' behaviour. An invitation to fishing styles. Fish and Fisheries 17 (1):78–100. doi:10.1111/faf.12092.

- Borthwick, L., K. Bergman, and F. Ziegler. 2019. Svensk konsumtion av sjömat. [Swedish seafood consumption]. RISE Rapport 2019:27.

- Boyd, C. 2014. Minimizing seabird by-catch in industrial fisheries. Animal Conservation 17 (6):530–1. doi:10.1111/acv.12179.

- Bryhn, A., A. Sundelöf, A. Lingman, A.-B. Florin, E. Petersson, F. Vitale, G. Sundblad, H. Strömberg, et al. 2020. Fisk- och skaldjursbestånd i hav och sötvatten 2019: resursöversikt [Fish and shellfish stocks in marine and aquatic environments 2019: resources overview]. Havs-och vattenmyndigheten. Online at https://pub.epsilon.slu.se/15997/1/sandstrom_a_et_al_190603.pdf

- Campbell, H. 2009. Breaking new ground in food regime theory: Corporate environmentalism, ecological feedbacks and the ‘food from somewhere’ regime? Agriculture and Human Values 26 (4):309–19. doi:10.1007/s10460-009-9215-8.

- Campbell, L. M., N. Boucquey, J. Stoll, H. Coppola, and M. D. Smith. 2014. From vegetable box to seafood cooler: Applying the community-supported agriculture model to fisheries. Society & Natural Resources 27 (1):88–106. doi:10.1080/08941920.2013.842276.

- Carothers, C., and C. P. Chambers. 2012. Fisheries privatization and the remaking of fishery systems. Environment and Society 3 (1):39–59. doi:10.3167/ares.2012.030104.

- Cinner, J. E., T. Daw, and T. R. McClanahan. 2009. Socioeconomic factors that affect artisanal fishers' readiness to exit a declining fishery. Conservation Biology 23 (1):124–30. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01041.x.

- Cochran, W. G. 1963. Sampling techniques. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Crosson, S. 2015. Anticipating exit from North Carolina's commercial fisheries. Society & Natural Resources 28 (7):797–806. doi:10.1080/08941920.2014.970737.

- Danhall, L. 2020. Andreas lives his dream – to be a fisherman [in Swedish]. Norrbottens-Kuriren, July 25, 2020.

- Davelid, A., A. Rosell, and C. Burman. 2014. Marknadsöversikt: Fiskeri och vattenbruksprodukter [A market overview: Products form fisheries and aquaculture]. Jorbruksverket Rapport 2014:23.

- Daw, T. M., J. E. Cinner, T. R. McClanahan, K. Brown, S. M. Stead, N. A. J. Graham, and J. Maina. 2012. To fish or not to fish: Factors at multiple scales affecting artisanal fishers' readiness to exit a declining fishery. PLoS One 7 (2):e31460. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031460.

- EC. 2017. The EU fishing fleet: Trends and economic results. DG MARE Econ Pap no. 03/2017. Brussels: Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (DG MARE) and Joint Research Centre (JRC). doi:10.2771/667047.

- FAO. 2018. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA) – Meeting the sustainable development goals. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization: License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Fernandes, R. M. 2012. Job satisfaction in the marine and estuarine fisheries of Guinea-Bissau. Social Indicators Research 109 (1):11–23. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0052-6.

- Garavito-Bermúdez, D. 2018. Learning ecosystem complexity: A study on small-scale fishers’ ecological knowledge generation. Environmental Education Research 24 (4):625–6. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1269877.

- Gatewood, J., and B. McCay. 1990. Comparison of job satisfaction in six New Jersey fisheries: Implications for management. Human Organization 49 (1):14–25. doi:10.17730/humo.49.1.957t468k40831313.

- Glaser, B., and A. Strauss. 1967. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

- Grafton, R. Q. 1996. Individual transferable quotas: Theory and practice. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 6 (1):5–20. doi:10.1007/BF00058517.

- Hentati-Sundberg, J., and J. Hjelm. 2014. Can fisheries management be quantified? Marine Policy 48:18–20. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2014.02.021.

- Hilborn, R. 2007. Managing fisheries is managing people: What has been learned? Fish and Fisheries 8 (4):285–96. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2979.2007.00263_2.x.

- Hinderson, J. 2014. Bengt Larsson Ställer Krav På Fisket [Bengt Larsson sets the demands on fisheries]. Sydöstran, April 16, 2014.

- Holland, D., E. Gudmundsson, and J. Gates. 1999. Do fishing vessel buyback programs work: A survey of the evidence. Marine Policy 23 (1):47–69. doi:10.1016/S0308-597X(98)00016-5.

- Holland, D. S., J. K. Abbott, and K. E. Norman. 2020. Fishing to live or living to fish: Job satisfaction and identity of west coast fishermen. Ambio 49 (2):628–39. doi:10.1007/s13280-019-01206-w.

- Hultman, J., F. Säwe, P. Salmi, J. Manniche, E. Baek Holland, and J. Høst. 2018. Nordic fisheries at a crossroad. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers. doi:10.6027/TN2018-546.

- Jentoft, S. 2000. The community: A missing link of fisheries management. Marine Policy 24 (1):53–60. doi:10.1016/S0308-597X(99)00009-3.

- Jentoft, S., A. Eide, M. Bavinck, R. Chuenpagdee, and J. Raakjaer. 2011. A better future: Prospects for small-scale fishing people. In Poverty mosaics: Realities and prospects in small-scale fisheries, ed. S. Jentoft and A. Eide. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Johnsen, J. P., and J. Vik. 2013. Pushed or pulled? Understanding fishery exit in a welfare society context. Maritime Studies 12 (1):4. doi:10.1186/2212-9790-12-4.

- Johnson, T. R. 2011. Fishermen, scientists, and boundary spanners: Cooperative research in the US illex squid fishery. Society & Natural Resources 24 (3):242–55. doi:10.1080/08941920802545800.

- Jordbruksverket and HaV. 2016. Svenskt yrkesfiske 2020: Hållbart fiske och nyttig mat [Swedish Commercial Fisheries 2020: sustainable fisheries and good food] Jordbruksverket and Havs och vatten myndigheten (HaV). Online at https://www.havochvatten.se/download/18.55c45bd31543fcf853650d44/1462194215508/svenskt-yrkesfiske-2020.pdf.

- Knutson, P. 2017. Escaping the corporate net: Pragmatics of small boat direct marketing in the U.S. Salmon fishing industry of the Northeastern pacific. Marine Policy 80:123–9. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2016.03.015.

- Krogseng, K. 2016. The decline of small-scale fisheries: A case study in Blekinge. NM009 Rural Development and Natural Resource Management–Master’s Programme 120.

- Lindebo, E., H. Frost, and J. Løkkegaard. 2002. Common fisheries policy reform a new fleet capacity policy. Fødevareøkonomisk Institut. Rapport nr. 141.

- Lunneryd, S.-G., and S. Königson. 2017. Hur löser vi konflikten mellan säl och kustfiske. Program Sälar och Fiskes verksamhet från 1994 till 2017 [How do we solve the conflicts between seals and coastal fisheries. Programme Seals and Fisheries collaboration between 1994 and 2017]. Aqua reports 2017:9. Drottningholm Lysekil Öregrund: Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet, Institutionen för akvatiska resurser.

- Maslow, A. H. 1954. Motivation and personality. Oxford, England: Harpers.

- Maslow, A. H. 1968. Toward a psychology of being. New York: D. Van Nostrand Company.

- Muallil, R. N., R. C. Geronimo, D. Cleland, R. B. Cabral, M. V. Doctor, A. Cruz-Trinidad, and P. M. Alino. 2011. Willingness to exit the artisanal fishery as a response to scenarios of declining catch or increasing monetary incentives. Fisheries Research 111 (1-2):74–81. doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2011.06.013.

- Neuman, E., and L. Piriz. 2000. The Swedish small-scale coastal fisheries-problems and prospects. Fiskeriverket Rapport 2:3–40.

- O’Donnell, K. P., T. Hesselgrave, and E. Macdonald. 2015. Understanding values in Canada's North Pacific: capturing values from commercial fisheries. Canadian Electronic Library. Canadian public policy collection. Vancouver, British Columbia: Ecotrust Canada. Online at https://ecotrust.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/1-Fisheries-2013-UnderstandingValuesCanadasNorthPacific-Report.pdf (accessed January 2021).

- Panayotou, T., and D. Panayotou. 1986. Occupational and geographical mobility in and out of Thai fisheries. ed. Panayotou, Fisheries technical paper (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations); no.271. Rome: FAO.

- Pita, C., H. Dickey, G. J. Pierce, E. Mente, and I. Theodossiou. 2010. Willingness for mobility amongst European fishermen. Journal of Rural Studies 26 (3):308–19. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2010.02.004.

- Pollnac, R. B., and J. J. Poggie. 1988. The structure of job satisfaction among New England fishermen and its application to fisheries management policy. American Anthropologist 90 (4):888–901. doi:10.1525/aa.1988.90.4.02a00070.

- Pollnac, R. B., and J. J. Poggie. 2006. Job satisfaction in the fishery in two Southeast Alaskan towns. Human Organization 65 (3):329–39. doi:10.17730/humo.65.3.3j2w39a21tq3j4l1.

- Pollnac, R. B., and J. J. Poggie. 2008. Happiness, well-being, and psychocultural adaptation to the stresses associated with marine fishing. Human Ecology Review 15 (2):194–200.

- Pollnac, R. B., T. Seara, and L. L. Colburn. 2015. Aspects of fishery management, job satisfaction, and well-being among commercial fishermen in the Northeast Region of the United States. Society & Natural Resources 28 (1):75–92. doi:10.1080/08941920.2014.933924.

- Poulsen, R. T., A. B. Cooper, P. Holm, and B. R. MacKenzie. 2007. An abundance estimate of ling (Molva molva) and cod (Gadus morhua) in the Skagerrak and the northeastern North Sea, 1872. Fisheries Research 87 (2-3):196–207. doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2007.07.002.

- Samuelsson, J. 2015. Fiskare försöker få filea på nytt [Fishers are trying to get fillets again]. Sydsvenskan, April 28, 2015.

- Säwe, F., and J. Hultman. 2012. Ask us!! We know!! Commercial fishers from Skåne about coastl fisheries [in Swedish, Fråga oss!! Vi vet!! Skånska yrkesfiskare om det kustnära fisket]. Lund University.

- Seara, T., R. B. Pollnac, and J. J. Poggie. 2017. Changes in job satisfaction through time in two major New England fishing ports. Journal of Happiness Studies 18 (6):1625–40. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9790-5.

- Seara, T., R. B. Pollnac, J. J. Poggie, C. Garcia-Quijano, I. Monnereau, and V. Ruiz. 2017. Fishing as therapy: Impacts on job satisfaction and implications for fishery management. Ocean & Coastal Management 141:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.02.016.

- Squires, D. 2010. Fisheries buybacks: A review and guidelines. Fish and Fisheries 11 (4):366–87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00365.x.

- STECF. 2019. Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF) – The 2019 Annual Economic Report on the EU Fishing Fleet (STECF-19-06). Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- Sundblad, E.-L., S. Hornborg, L. Uusitalo, and H. Svedång. 2020. Svensk konsumtion av sjömat och dess påverkan på haven kring Sverige [The Swedish consumption of seafood and its impacts on the sea arouund Sweden]. Rapport nr 2020:1, Havsmiljöinstitutet. Online at https://havsmiljoinstitutet.se/digitalAssets/1763/1763896_rapport-konsumtion-slutgiltig-27-jan.pdf

- Svels, K., P. Salmi, J. Mellanoura, and J. Niukko. 2019. The impacts of seals and cormorants experienced by Baltic Sea commercial fishers. In Natural resources and bioeconomy studies 77/2019. Helsinki: Natural Resources Institute Finland.

- Sweke, E. A., Y. Kobayashi, M. Makino, and Y. Sakurai. 2016. Comparative job satisfaction of fishers in northeast Hokkaido, Japan for coastal fisheries management and aquaculture development. Ocean & Coastal Management 120:170–9. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.12.001.

- Teh, L. S. L., N. Hotte, and U. R. Sumaila. 2017. Having it all: can fisheries buybacks achieve capacity, economic, ecological, and social objectives? Maritime Studies 16:1. doi:10.1186/s40152-016-0055-z.

- Tidd, A. N., T. Hutton, L. T. Kell, and G. Padda. 2011. Exit and entry of fishing vessels: An evaluation of factors affecting investment decisions in the North Sea English beam trawl fleet. ICES Journal of Marine Science 68 (5):961–71. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsr015.

- Urquhart, J., T. Acott, and M. Zhao. 2013. Introduction: Social and cultural impacts of marine fisheries. Marine Policy 37:1–2. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2012.04.007.

- Vesterberg, V. 2019. Havet hör bygden till: Kustnära fiske och gastronomi på Österlen [The sea belongs to the village: coastal fisheries and gastronomy in Österlen]. MA uppsats, Agronomprogrammet, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet. https://stud.epsilon.slu.se/14287/.

- Villasante, S. 2010. Global assessment of the European Union fishing fleet: An update. Marine Policy 34 (3):663–70. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2009.12.007.

- Waldo, Å., M. Johansson, J. Blomquist, T. Jansson, S. Königson, S.-G. Lunneryd, A. Persson, and S. Waldo. 2020. Local attitudes towards management measures for the co-existence of seals and coastal fishery – A Swedish case study. Marine Policy 118:104018. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104018.

- Waldo, S., and J. Blomquist. 2020. Var är det lönt att fiska? en analys av fisket i svenska regioner [Where is it worth fishing? An anlysis of fisheries in Swedish regions] Agrifood Economics Center. Fokus 2020 (2):1–20.

- Waldo, S., and I. Lovén. 2019. Värden i svenskt yrkesfiske [Values in Swedish fisheries]. AgriFood Economics Centre. Rapport 2019 (1):1–74.

Appendix 1.

Voluntarily-supplied reasons for fisheries exit among holders of a commercial fishing license in sweden.