?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The application of scientifically rigorous public engagement approaches is lacking. In this context, we present a “social vulnerability protocol” which has now been applied in several broad-scale planning efforts. The protocol aims to understand the multitude of relationships that people have with public land through a prioritization of ecosystem services and a selection of relevant drivers of change. The protocol is analytically rigorous and readily interpretable, and is clearly tied to the planning objectives of knowledge co-production, tradeoff analysis, and understanding how various threats may impact social well-being. In the context of the Gila National Forest Plan revision, comparisons between the perspectives of the public and those of the local land management agency show a diversity of stakeholder values and human-nature relationships. We believe this approach contributes to more inclusive decision-making, strengthens public understanding of the complexities involved, and builds trust through transparent and explicit acknowledgement of diverse perspectives.

Introduction

It is generally viewed as necessary to include a broad range of stakeholders and publics in planning processes focused on addressing complex environmental problems (Reed Citation2008). Many complex environmental situations, including national forest planning in the United States, are considered “wicked” problems (Rittel and Webber Citation1973; Norton Citation2012), because they are, in part, characterized by diverse and sometimes conflicting stakeholder viewpoints, and no single “correct” solution. As such, the integration of diverse viewpoints through inclusive planning approaches is thought to build trust and mutual understanding, reduce conflict, and foster learning in a way that builds support for, and perhaps co-create, the decisions that need to be made (Borrie, McCool, and Stankey Citation1998; McCool and Guthrie Citation2001; Reed et al. Citation2018; Muro and Jeffrey Citation2008).

While the merits of public engagement are generally accepted, though occasionally contested (Cooke and Kothari Citation2001), implementing public engagement approaches in practice is challenging. Foremost, a planning practitioner interested in implementing a public engagement method informed by scientific literature may be overwhelmed by the number of available options. For example, Rowe and Frewer (Citation2005) highlight around 100 different “mechanisms” ranging from focus groups and citizen juries to participatory theater and game simulation. Similarly, Vacik et al. (Citation2014) described and analyzed 43 participatory planning methods. Such overviews illustrate a wide range of engagement approaches that vary by institutional and cultural context (Tippett, Handley, and Ravetz Citation2007; Linnenluecke et al. Citation2017; Reed et al. Citation2009; Beierle and Cayford Citation2002; Talley, Schneider, and Lindquist Citation2016; Lawrence and Deagen Citation2001).

In considering the various options available for implementing a public engagement approach, we make three interrelated observations. First, in the context of formal broad scale planning in the United States such as forest plan revision, there is limited application of public engagement approaches that are underpinned by rigorous social science. Public engagement is a policy mandated requirement, and in practice it is generally dominated by open houses, listening and learning sessions, and a range of consultative activities. To be clear, these facilitated approaches, particularly if a skilled facilitator can be afforded, are important for stimulating early involvement and continued engagement throughout the planning process and for information exchange (Dyer et al. Citation2014; Rowe and Frewer Citation2000). Additionally, facilitated time together for stakeholders can both support the development of human capital (e.g., relationships, civic loyalty) (Lawrence and Deagen Citation2001) and also represent democratic engagement principles of consultation (Reed et al. Citation2018). However, where such techniques may fall short, or even frustrate participants, is if the product of their participation is not evident. Rigorous collection, analysis, and effective dissemination of what was heard during facilitated activities is not necessarily the norm. As a result, the validity and replicability of the studies is challenging to establish, thus undermining the defensibility of the findings. The limited application of scientifically-robust approaches is likely due to method complexity and a limitation on available resources to implement the method. For instance, applying a Bayesian belief networks approach or a choice modeling approach may not be practical nor necessarily affordable for planners and managers.

Second, and likely another reason for limited scientifically-robust applications in practice, public engagement methods are often not tied to concepts in the conservation research literature. In other words, while the technical aspects of a public engagement approach may be clear (e.g., analysis), the framework for how to implement a particular approach within the context of conservation is not always clear. For instance, planners focused on a revision of a forest plan in the United States might be interested in citizen juries, but what those juries might discuss may not be readily apparent. This suggests a lack of conceptual relevance or applicability to environmental concerns.

Third, as noted by Talley, Schneider, and Lindquist (Citation2016, 1), there is a disconnect between scientific recommendations and “empirical case studies that represent on-the-ground stakeholder engagement practices.” In other words, critical components of public engagement approaches, such as an articulation of clear objectives, are not always present. That is, many practices documented in the scientific literature are not always included in application.

These three observations serve as critical criteria for consideration of public engagement processes and informed our development of a scientifically-robust public engagement process that could be provided to, and potentially implemented by, practitioners on the ground. Furthermore, in designing such a scientifically-informed process, we specifically focused on an approach that:

allowed all participants to provide their input, in an equitable manner which did not exclude certain personality types (e.g., some people may not want to speak up in a room full of people) or overemphasize well-represented or vocal interest groups (Reed et al. Citation2018; Ansell and Gash Citation2007; Rowe and Frewer Citation2000);

included scientific analysis of input to ensure an unbiased and transparent distillation of many voices into a tractable number of viewpoints, which both represented the diverse range of opinions heard and resisted a central tendency of opinion (Brown Citation1980; Watts and Stenner Citation2012);

emulated the challenging task facing managers and planners, where tradeoffs and prioritization of sometimes conflicting viewpoints is required;

seemed relevant and applicable for the planning context (Brummel et al. Citation2010; Reed et al. Citation2018) and;

engaged participants during the public engagement activity itself, as well as with the presentation of final results.

Given the limited application of scientifically-based public engagement approaches in national forest planning in the United States, we introduce an approach dubbed a “social vulnerability protocol” (henceforth, the “protocol”) (Armatas et al. Citation2019), which specifically addresses the conceptual and methodological issues raised above. Our goal is to highlight the existence of a social science approach (i.e., the protocol) that: (1) is both methodologically robust and tied to relevant concepts in the social science literature and; (2) has seen implementation in several public engagement processes for broad-scale national forest planning efforts in the United States. Further, we aim to discuss potential benefits of integrating such an approach into public engagement processes that are often dominated by consultative activities.

This paper proceeds with a description of the conservation planning context, which includes a conceptual framing for the public engagement protocol (i.e., human-nature relationships and social vulnerability) and a brief discussion of why comparing manager perspectives to those of the public represents a generally unexplored opportunity. We then provide a methodological overview of the protocol and results from an application on the Gila National Forest in New Mexico (where, as a research team, we contributed to forest plan revision efforts by joining the Gila National Forest planning team during a week-long public engagement effort). Finally, we discuss both realized and potential benefits of the public engagement protocol for supporting planning efforts.

The Planning Context

The public engagement approach presented herein is designed to support broad scale public lands planning processes, such as national forest plan revisions and comprehensive river management planning in the United States. As such, given the requirement for both public engagement and that the managing agency (the US Forest Service) must still maintain decision-making authority, the relationship between the agency and the public is best positioned somewhere between “top-down one-way communication and/or consultation” and “top-down deliberation and/or coproduction” (Reed et al. Citation2018, 10). The intention of public engagement is to integrate local interests and knowledge into the planning process and, to the greatest extent practicable, co-develop solutions; however, ultimately, the decisions are made by the US Forest Service.

Conceptual Framing

Broad-scale planning efforts for the US Forest Service are currently prescribed by the 2012 Planning Rule, an administrative policy that meets the requirements of legal policy including the National Forest Management Act of 1976, the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960, and the Endangered Species Act of 1973. The 2012 Planning Rule explicitly mandates the consideration of social, ecological, and economic sustainability (USDA Forest Service Citation2012). Fundamentally, this three-tiered sustainability mandate requires a broad conceptualization for how people relate to nature and, as such, our notion of human-nature relationships (Armatas Citation2019), is also broad in a manner consistent with Flint et al. (Citation2013).

Human-nature relationships, within the context of the protocol, move beyond worldviews or attitudes related to the appropriate role, or positionality, of humans with regard to nature (e.g., humans as “master” or “steward”) (van den Born et al. Citation2001; Bauer, Wallner, and Hunziker Citation2009). That is, we agree with Dvorak, Borrie, and Watson (Citation2013, 1519) that the term human-nature relationship is “quite nebulous,” but that the lack of a narrow definition can facilitate inclusivity of different worldviews in a way that is akin to “nature’s contribution to people” (Díaz et al. Citation2018). We find the nebulous nature of human-nature relationships to be beneficial, as it is represents a holistic idea that can, at least implicitly, capture the complexity, depth, and nuance with which people connect, value, interact, and/or relate to nature. However, when empirically investigating human-nature relationships within the conservation planning context, we suggest that, inevitably, the holistic idea is reduced to being comprised of component parts, or elements (Armatas Citation2019). That is, when engaging the public within conservation planning, we suggest that there is a need to apply some framework to make the constituent parts of the human-nature relationship explicit.

While we suggest there is no perfect framework that can fully capture human-nature relationships, the concept of ecosystem services provides an option that aims to encompass the diverse ways that people relate to nature. For instance, de Groot, Wilson, and Boumans (Citation2002) defined ecosystem services as the benefits from which humans derive ecological, socio-cultural, and economic value. Within the context of forest plan revision in the United States, ecosystem services is an appropriate framing; indeed, the Forest Planning Rule states that forest planning “provide for ecosystem services and multiple uses, considering the full range of resources, uses, and benefits relevant to the unit” (USDA Forest Service Citation2012, 21167). While we view ecosystem services as an important metaphor for understanding how people relate to national forests, we also recognize the critiques of ecosystem services. Namely, that ecosystem services is a metaphor that potentially encourages a narrow economic framing and has trouble incorporating cultural, social, and spiritual values (Chan, Guerry, et al. Citation2012; Chan, Satterfield, et al. Citation2012). As a result, in practice (i.e., when interacting with the public), we do not stress the ecosystem services terminology. Instead, we reiterate our framing of the protocol as a structured process for the expression of one’s unique human-nature relationship and what is most important to it.

The second fundamental component of the protocol, as discussed in detail below, requires participants to consider the “drivers of change” perceived to be most influential to their human-nature relationship and what might be most at threat or vulnerable within that relationship. Therefore, particular drivers of change are understood within the context of the specific variables of concern such as ecosystem services (Armatas, Venn, et al. Citation2017; Luers Citation2005). In this way, the protocol is further conceptually framed within social vulnerability, which has both been central to sustainability science (Turner Citation2010) and also adopted by land management agencies in the United States (Fischer et al. Citation2013; Murphy et al. Citation2015). Specifically, within the context of the Forest Planning Rule, managers are required to consider “stressors and other important factors” (USDA Forest Service Citation2012, 21167). The naming of our approach as a “social vulnerability protocol” primarily serves to position it within the literature (mostly when communicating with researchers) and, when communicating with practitioners, it relates to the US Forest Service efforts on threats, stressors and vulnerability.

Comparing Agency Employees and the Public Viewpoints

Below we present a comparison of manager and public viewpoints. Generally, it is accepted that good public engagement practice includes input from a broad range of people (Dyer et al. Citation2014; Rowe and Frewer Citation2000; Reed et al. Citation2018). But it seems that, particularly in top-down engagement processes where there is a decision-making power imbalance, the interest is generally on gathering input from the public without a clear articulation of the opinions and viewpoints of decision-makers. However, we argue that transparency, trust building, and the development of human capital may benefit from agency employee participation in all public engagement processes. For these reasons, we see the comparison of public viewpoints to agency employee viewpoints as a generally unexplored opportunity.

To be clear, there is some empirical knowledge related to how the viewpoints of agency employees in the United States compare to the publics they are serving. For instance, within the context of designated Wilderness in the United States, studies identified differences between managers with regard to campsite impacts (Martin, McCool, and Lucas Citation1989) and pack-animal use (Watson et al. Citation1998). Beyond the United States, there are examples of comparing professionals to the public (e.g., Wagner et al. Citation1998), but we maintain that empirical comparisons in the literature between agency decision-makers and the general public are generally limited.

However, comparing employee perceptions with those of the public, according to Watson et al. (Citation1998, 3), can facilitate an understanding whereby “working toward common ground in management should become easier.” Understanding how the public perceptions differ from those of decision-makers can highlight consensus and disagreement between the two groups related to what issues are most important and, relatedly, it could stimulate clear communication about mandates (e.g., policy) influencing decision-makers. For instance, related to pack-animal use in Wilderness, the views related to llama use were found to be distinctly different between managers and the public (Watson et al. Citation1998). Incongruences between manager and public perceptions for this paper may be particularly important within the context of drivers of change, as it can highlight a difference in priorities related to the threats to human-nature relationships.

Methods

The public engagement protocol aims to build an understanding of perceived tradeoffs of human-nature relationship elements (e.g., ecosystem services) through a prioritization exercise and, subsequently, a selection of drivers of change perceived as most relevant. Such knowledge supports decision-making and, perhaps more importantly, improves public relations (i.e., with an understanding of different publics and clear communication about the relevant and diverse stakeholder perspectives). Additionally, this protocol is designed to provide flexibility and opportunities for creativity (as demonstrated below, with analysis of different samples of people: the interested public and natural resource planners and managers). It is readily accessible—via a published step-by-step guide (Armatas et al. Citation2019) and a 20-min “science you can use” webinar (Armatas Citation2020).

The protocol is largely underpinned by Q-methodology (Watts and Stenner Citation2012; Brown Citation1980) and has been applied in a number of locations and planning contexts (). It includes three main steps which, in total, take participants around 30 min: (1) a Q-sort of ecosystem service descriptors; (2) a drivers of change component and; (3) a short demographic assessment of who participated.

Table 1. Overview of applications of the social vulnerability protocol.

Q-methodology is a social science methodology that originated in psychology (Stephenson Citation1936, Citation1954) and has become increasingly popular in natural resource management (e.g., Steelman and Maguire Citation1999; Hermelingmeier and Nicholas Citation2017; Buchel and Frantzeskaki Citation2015) with specific mention as an option for public engagement (e.g., Vacik et al. Citation2014; Reed et al. Citation2009). Q-methodology, fundamentally, asks respondents to sort items about some topic; with items sorted relative to one another along a quasi-normal distribution. The method has characteristics that are both quantitative (e.g., factor analysis) and qualitative (e.g., purposeful sampling yielding different perspectives without concern for how perspectives are distributed among a population) (Stenner and Stainton-Rogers Citation2004).

The “Q-sort” in this study has respondents order a diverse list of benefits derived from the natural resource of interest. In the Gila National Forest application (Armatas, Borrie, et al. Citation2017), the list of ecosystem services were identified from documentation of previous public scoping, discussions with natural resource experts, and analysis of study area specific literature (). Primarily, and more specifically, we distilled the Gila National Forest’s “Final Assessment Report of Ecological/Social/Economic Sustainability Conditions and Trends” (USDA Forest Service Citation2017) into an initial brainstorming list of ecosystem services and drivers of change. At this stage, we were not concerned with the challenging task of lumping and splitting (e.g., listing specific recreation activities vs. listing recreation generally). In Q-methodology parlance, this step is referred to as “concourse” development, and the general goal is to compile a list of potentially innumerable statements around the topic of interest (Brown Citation1980); the concourse for the Gila National Forest application included a list of 152 ecosystem services. Using an iterative approach, which included several conversations and reviews by the planning team, as well as pilot testing by both agency employees and partner university students and professors, we honed the “concourse” into the final list of 30 ecosystem services to be sorted by the public ().

Table 2. List of ecosystem services identified for the Gila National Forest, New Mexico.

Participants prioritize each of the 30 ecosystem services (printed on separate white cards) from “more important” to “less important” to their relationship with the Gila National Forest. The prioritization, or Q-sort, is completed along a quasi-normal distribution, whereby columns denote different values, but the rows do not. That is, each participant chooses two ecosystem services for the “+4” column, three ecosystem services for the “+3” column, and so on (the distribution is illustrated below, in the results section). This engagement exercise is different than a survey format wherein respondents can assign the same level of importance to each, and potentially every, ecosystem service. In contrast, we believe forced prioritization is important because: (1) it emulates the prioritization facing managers and, while we recognize all ecosystem services are important, the nature of managing for broad ranging sustainability does entail, in some situations, a confrontation of tradeoffs and; (2) it forces an interaction with every ecosystem service in a way that prompts and facilitates learning about the various ways people relate to the natural resource of interest.

For the second step, participants choose the three drivers of change that they feel influences or could influence their human-nature relationship (as is represented in their just-completed Q-sort). For the Gila National Forest, a preselected list of 12 drivers of change was developed based on previous forest plan revision scoping (). The development of this list was completed alongside the development of the ecosystem services list (i.e., a “concourse” of 63 drivers of change was developed by distilling the Final Assessment Report, and then iteratively pared down to 12 through discussions with agency employees and pilot tests with both agency and non-agency people). It is worth noting that climate change, as a broad driver of change, was represented in more specific impacts (e.g., extended drought), based on the desire to understand, with a bit more specificity, how climate change was influential to human-nature relationships. In addition to cards for each of the 12 drivers of change, blank cards were provided for the option of writing in a specific driver of change not included in the preselected list.

Table 3. List of potential drivers of change on the Gila National Forest, New Mexico.

The final part of the exercise is to gather basic demographics, only for the purpose of understanding the broad range of who participated in the exercise.

For data analysis, factor analysis is performed on the Q-sorts to distill the relatively large number of individual perspectives into a limited number of archetypal perspectives. Regression analysis is then performed to identify those drivers of change that explain the most variance in the factor scores of the archetypal perspectives. Full discussion of this analysis can be found in Armatas et al. (Citation2019).

Q-methodology focuses on showcasing the diversity of opinions surrounding a topic of interest and not how such opinions are distributed across a population. As such, sampling is typically purposeful: of either targeted stakeholders through dimensional and snowball sampling; convenience sampling of members of the interested public who attended public meetings; or a combination of the two. For the Gila National Forest application, 122 members of the public participated at one of five public meetings (workshops) organized as part of the forest plan revision process. Additionally, a second sample of 50 employees was collected from the forest and district level of the Gila National Forest. To gain employee input, we visited five district offices and the supervisor’s office on the Gila National Forest and asked employees to participate. Generally, these district offices are small, and in some cases, we gained full participation. Overall, a diverse range of employees participated, from district rangers to seasonal employees. Of note, we did not gather input from the core planning team.

Given the relatively small sample sizes and purposeful sampling, comparing the two samples with formal statistics such as analysis of variance, is less appropriate. Instead, the following basic procedures were applied: (1) comparison of descriptive statistics of each sample (e.g., mean rankings and standard deviation of ecosystem service importance); (2) separate factor analysis of each sample’s Q-sorts and; (3) a correlation analysis of the factors and the drivers of change that result from each of the samples.

Results

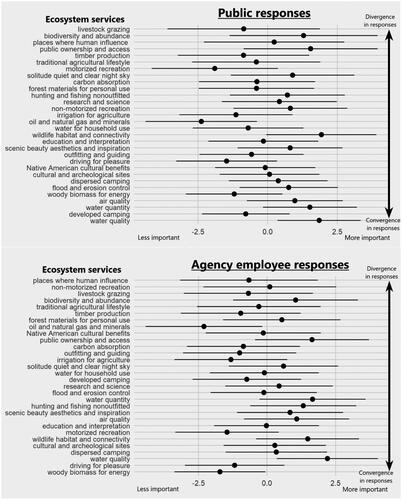

shows the ecosystem services ordered by standard deviation (from lowest at the bottom to highest at the top) and illustrates the similarities and differences between the public’s sorting and the agency employee’s sorting. Ecosystem services that received relatively low variation in importance within a sample have more agreement (i.e., convergence) and are shown toward the bottom of each group. For example, ecosystem services such as “woody biomass for energy” and “dispersed camping” show less variation in both the public and the employee samples. In contrast, “livestock grazing” and “biodiversity and abundance of plants and animals” show more variation in both groups (and are shown toward the top of each group, with larger standard deviations). Those ecosystem services ranked with greater divergence may require increased attention within planning discussions, as one might expect decisions around such ecosystem services to be more contentious.

Figure 1. Divergence and convergence of mean importance scores for ecosystem services across public respondents (n = 122) and agency employee respondents (n = 50) on the Gila National Forest, New Mexico. Notes: Dots represent mean importance for each ecosystem service. Bars represent standard deviations for each ecosystem service.

In addition to understanding variation, provides an overview of those ecosystem services that, on average, were sorted as more or less important. An understanding within and between the samples can be gleaned. For example, “oil and natural gas and minerals” was generally sorted as less important, with a mean ranking approaching −2.5 by both samples. Interestingly, on average, both samples were generally in agreement about the level of importance across the majority of ecosystem services. Only three ecosystem services (i.e., “forest materials for personal use,” “places where human influence is substantially unnoticeable,” “flood and erosion control”) had mean negative importance for one sample and positive importance for another. The ecosystem service with the biggest difference between samples is “forest materials for personal use,” with a mean value approaching +0.5 for the agency employees and −0.5 for the public.

While inspection and comparison of descriptive statistics (as in ) provides a basic understanding of the responses, a subsequent factor analysis of both samples extends the understanding and exploration of the different perspectives. Each individual’s Q-sort is a unique ordering of what they see as important on the Gila National Forest, and the factor analysis looks for common patterns in the way individuals have tackled that ordering. The resultant factors or archetypal perspectives are a condensation of the individual Q-sorts and can be thought of as typified (representative types) within the sample. That is, individual Q-sorts that are strongly correlated with one another (showing similar importance scores on the same individual ecosystem service) are grouped together into a shared perspective or “archetype.”

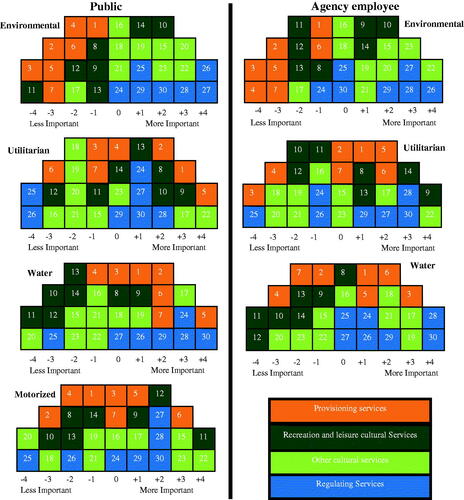

Analysis of the Q-sorts completed by the public yielded a four-factor solution, whereas analysis of the agency employee Q-sorts yielded a three-factor solution. In , the numbers in each box correspond with the numbered ecosystem services in , and the color scheme follows different categories of ecosystem services (e.g., provisioning services represented by the orange boxes). Inspection of can: (1) provide a nuanced picture of any individual archetype; (2) highlight the different archetypal perspectives within either the public or the employee samples (by making a vertical inspection of, say, the environmental and utilitarian perspectives on either side of the figure) and; (3) provide comparisons between the two samples (horizontal inspection across the figure), as each discussed below. illustrates the contribution of the public engagement protocol has toward clear communication, increased transparency and stronger presentation of the different ways people relate to the natural resource of interest.

Figure 2. A comparison of interested public and agency employee perspectives. Note: Numbers in each perspective correspond to ecosystem services for the Gila National Forest, New Mexico (see ).

As an example of a nuanced understanding of an individual archetype, the motorized archetype is named for the importance assigned to “motorized recreation” (11) and “driving for pleasure” (12), both of which are prioritized higher by this archetype than all other public archetypes. Generally, those who align with this perspective place relatively high importance on ecosystem services contributing to motorized recreation experiences, both through environmental conditions (27, 28, 30) and experiential conditions (15, 23). Freedom to roam is a part of experience that is important to the motorized archetype, which may be reflected by the importance assigned to “public ownership and access to public land” (22) (Armatas, Borrie, et al. Citation2017).

Inspection of vertically can provide a comparison between the different archetypes within a sample. For instance, three of the four public archetypes appear to agree that “public ownership and access to public land” is highly important (Environmental archetype (+3), Utilitarian archetype (+4), Motorized archetype (+4)). Another insight gained from inspecting the public archetypes vertically is different potential perceptions related to designated Wilderness lands. Although the ecosystem services prioritized by participants did not specifically mention Wilderness areas, “solitude, quiet, and clear night sky” (15), and “places where human influence is substantially unnoticable” (20) are conditions often associated with Wilderness (Armatas, Borrie, et al. Citation2017). In addition, motorized recreation and several provisioning ecosystem services are not heavily derived from Wilderness. Those who identify with the environmental relationship potentially hold the most positive Wilderness view, with “solitude, quiet, and clear night sky” (15), and “places where human influence is substantially unnoticeable” (20) ranked as highly important; whereas, motorized recreation (11) and all provisioning services (e.g., 2, 3, 5, 7) fall to the left side of the factor array. For the other three archetypes, the underlying perspective regarding Wilderness is more ambiguous.

Finally, a horizontal comparison of highlights the differences between the sample of the public and the sample of the agency employees. For example, it can be observed that the motorized archetype evident in the public sample was not evident in the Forest Service sample. Secondly, the archetypes dubbed “environmental,” “utilitarian,” and “water,” while quite similar across the Forest Service and public samples, are also different in some notable ways. For instance, the (horizontal) comparison of the “water” perspective show similarities in this perspective with both samples having a higher prioritization of water quality (28) and quantity (30), and a view that recreation ecosystem services (10, 11, 12) are less important. However, the “water” perspective held by the public was identified in part due to the high level of importance placed on agricultural ecosystem services (5, 17); whereas the employee version of this perspective prioritizes “oil and natural gas and minerals” (3), as well as several “other cultural services” such as research and science (19), education and interpretation (18), and cultural and archeological sites (21). The employee “water” perspective highlights a multiple use stance such that extraction of oil and natural gas and minerals as viable and important as long as water resources can be protected. Additionally, the employee “water” perspective also seems to stress the importance of a strong scientific understanding and educational component within the context of this particular extractive use of public land.

While the similarities between the top three archetypal perspectives in each side of can be examined visually (e.g., both “environmental” perspectives are clearly similar), a statistical comparison can also be carried out with a basic correlation of the seven perspectives as shown in . The correlation coefficient between two Q-sorts is calculated:

where d is equal to the difference between scores for each statement (ecosystem services in this case), N is the number of statements being ranked, and s2 is equal to the variance of the forced distribution.

Table 4. Correlations between the different interested public and agency employee perspectives.

A correlation of 1.0 would mean the two archetypal perspectives have the exact same prioritization of ecosystem services, whereas a correlation of −1.0 would mean the two Q-sorts have exactly opposite prioritization as each other (such as the highest importance in one perspective would have an equally negative importance in the other). In the current example, with a correlation of 0.92, both environmental perspectives are highly similar. Correlations close to zero indicate little similarity between the two perspectives between the two samples. For example, with a correlation of −0.02, the public motorized perspective has little in common with the public environmental perspective.

Finally, the protocol can show which drivers of change are most relevant to each of the samples and to each of the different archetypal perspectives. For the Gila National Forest, includes: (1) percentages of each sample that selected a particular driver of change, and (2) the regression coefficients between drivers of change and each perspective. For example, comparisons of the two samples show that, perhaps unsurprisingly, that employees considered “declining Forest Service budgets” to be highly relevant (with 68% selecting this as one of their most influential drivers of change). Also, it can be seen that the employee sample, relative to the public, had a greater proportion select impacts stemming from climate change (i.e., with a greater proportion selecting “extended drought” (44% vs. 11%), “extreme weather” (18% vs. 10%), and “uncharacteristic fire” (34% vs. 20%)).

Table 5. Percent of each sample selecting driver of change and the strength of associations with each of the public perspectives on Gila National Forest.

Considering the regression analysis of the association between each driver of change and each archetypal perspective, the employee sample of 50 people yielded only one statistically significant result. Therefore, only the associations between drivers of change and the public perspectives are presented. Under the “regression coefficients” portion of , the associations can be interpreted as the change in the factor loading that each person has in relation to each perspective if a particular driver of change is selected. In other words, in Q-methodology, each person who completed a Q-sort (e.g., 122 members of the public) has a factor loading that indicates how much variation of their individual Q-sort is explained by each factor (perspectives). The regression coefficients show the associations between drivers of change selected and changes in these factor loadings. For example, selecting “streamflow alterations and diversions” is associated with an average increase in the factor loading on the environmental perspective of 0.23, all else constant. This indicates a positive relationship between “streamflow alterations and diversions” and the environmental perspective (indicated by statistical signficance of the correlation at a level of p < .01). That is, if a person selected “streamflow alterations and diversions” as one of their three most influential drivers of change, then it is expected that they would be more associated with the environmental archetype than those who did not select this driver of change (holding all other drivers of change constant) (Armatas et al. Citation2019).

Associations between archetypal perspectives and particular drivers of change can reinforce the insights of the factor analysis. For instance, regarding the public’s utilitarian perspective, the drivers of change that are most concerning appear to be “land use restrictions” (0. 21) and “woody encroachment of grasslands” (0.20). This is not particularly surprising, as land use restrictions may be a percieved impediment to realizing some of the utilitarian benefits flowing from the Gila National Forest, and woody encroachment of grasslands is considered more threatening to agricultural benefits. Additionally, understanding these associations between drivers of change and perspectives highlights those issues that may be more pressing to people holding a particular set of values. If discussing planning issues on the Gila National Forest with someone who is interested in motorized use, then providing both the broad context gained from and focusing more specifically on roads and trials (0.10) may be worthwhile.

Discussion: Benefits of Injecting Robust Social Science into the Public Engagement Process

A general goal of this paper is to raise awareness of, and illustrate some of the useful insights generated by, the social vulnerability protocol. Specifically, we suggest that the protocol is readily available for adoption, because of available “how-to” resources, a conceptual framing, and the ability for flexible and creative implementation. Additionally, we suggest that there are both decision-making and public relations benefits.

Prior to discussing these suggested contributions (i.e., adoption, decision-making support, and public relations), it is worth highlighting that early discussions of outcomes provided by public engagement approaches (e.g., learning, trust building) generally lacked empirical evidence (i.e., outcomes were mostly aspirational) (Bull, Petts, and Evans Citation2008). However, formal evaluations of public engagement approaches have proliferated in recent years. A limitation of this current research is that there is no formal evaluation of the impact of this approach on those participating, though it is important future research.

Further, as this paper is largely targeting practitioners interested in a social science approach for public engagement, we are interested in demonstrating the flexibility of the approach with the hope of stimulating creativity in the application of the protocol. The manager viewpoints were of interest internally within the agency and so there was value in having agency employees complete the public engagement exercise. But, at the time that this research took place, presenting the comparison of agency employee viewpoints alongside public viewpoints in a formal way was not part of the discussions between the research team and the planning team; as such, the presentation of results of the protocol on the Gila National Forest did not include the manager viewpoints.

Decision-Making Benefits for the Forest Plan

We believe the protocol helps planners and managers to understand the perceived tradeoffs regarding important ecosystem services (more broadly, human-nature relationship elements) and how increasing the flow of some ecosystem services may influence the flow of others. For instance, increasing livestock grazing on the Gila National Forest is likely to support the water and utilitarian archetypes, while the environmental archetype may be negatively impacted. Somewhat differently, the protocol can help managers understand when the same tradeoff is being perceived by archetypes in different ways (Armatas et al. Citation2019). For instance, the public water archetype and the public environmental archetype appear to perceive a tradeoff between “livestock grazing” (5) and “places where human influence is substantially unnoticeable” (20). But, it is likely that the environmental archetype considers grazing to be a threat to the desired lack of human influence, whereas the water archetype considers the mandate to limit evidence of human influence as a potential threat to the grazing use of the Gila National Forest.

Combining knowledge related to both the archetypal perspectives and the associated drivers of change may help planners identify those issues or threats that are most concerning to people with particular human-nature relationships. For instance, the motorized perspective is concerned with access, as seen by the high importance assigned to “public ownership and access to public land” (Armatas, Borrie, et al. Citation2017). A driver of change that is integral to realization of this benefit is the conditions of roads and trails (as seen by high correlations with that driver of change).

Supporting evidence that these decision-making benefits have been realized are reflected in the revised, late-draft Gila National Forest plan, where the results of this public engagement approach (i.e., Armatas, Borrie, et al. Citation2017) are cited extensively. Specifically, in discussion of the “forest-wide plan direction,” there are sections related to different resources (e.g., water quality, upland ecological units), each of which has an “ecosystem services” subsection (United States Department of Agriculture Citation2018). Within the majority of these ecosystem services subsections, the results of the social vulnerability protocol are cited both specifically through a discussion of which ecosystem services are generally important to the public, and more generally with regard to assessing tradeoffs and consulting with stakeholders. For instance, in one section, “water quality” (28) and “biodiversity and abundance of plant and animal species” (26) are cited as important ecosystem services; further, the Plan states that the “ecosystem services approach…balances the complex interrelationships and trade-offs between these services” by, in part, proactively engaging “stakeholders with diverse perspectives” (United States Department of Agriculture Citation2018, 34).

Public Relations, Communication, and Opportunities for Trust

The protocol provides a cognitively manageable way to consider and visualize peoples’ different interests without weighting the interests of some over the interests of others (particularly since proportionate distribution of each perspective across the population is not provided). In other words, we have found distilling myriad individual views down to a limited number of archetypical perspectives supports continued learning and discussion about how different people relate differently to a natural resource. Anecdotally, participants often provide positive feedback on the way results are presented with colorful figures. With regards to the decision-maker perspective on the protocol, two members of the Planning Team commented that benefits of the protocol included: (1) connecting “people to the wide range of ecosystem services that public lands provide” and; (2) the ability of stakeholders and land management agencies to “gain shared understanding of diverse values, inherent tradeoffs, and drivers of change in resource management planning.”

The protocol can capture those who may not speak up in a room full of people with an individual, hands-on activity. Additionally, this systematic and structured activity with a clear method of analysis creates confidence and a sense of scientific legitimacy in the process; it provides a referenceable source, which can be circulated to those who may not attend meetings. While we think the statistical analysis can provide legitimacy to the process, we also acknowledge that presenting extensive information about such analyses may be counterproductive. Therefore, it is important to present those elements of the results that are accessible and beneficial to an improved understanding of human-nature relationships () and drivers of change (), without burdening the public with unnecessary analytical details. But, it is important to have references, in a simplified form, to analytical details, should they be requested; to this end, we have developed simple descriptions of the statistical analyses in Armatas et al. (Citation2019).

An aspirational and likely benefit of this protocol is trust building between the public and agency employees. We believe that the protocol generally has the potential to build trust (through scientific legitimacy and a referenceable source of what was heard from the public). Regarding the potential comparison of the interested public and decision-makers, there may also be trust building opportunities. While such a comparison could lead to conflict, as the interested public (particularly those with a motorized perspective in this case) may discredit decisions based upon a perceived inherent bias in the agency’s employees, the transparency represents a good faith effort and would likely build trust (if care is taken to fully understand and consider the missing perspective).

Adoption by Practitioners: Less Researcher Support

Finally, we have some evidence that the approach presented herein could be adopted by practitioners without significant research support. This application of the social vulnerability protocol, as well as those in , was completed by researchers. However, this protocol has been adopted in two other contexts where researcher support is less prevalent. Recently, an employee for the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality implemented the protocol within the context of sustainable materials management, with the help of three consultation phone calls. Currently, another application of the protocol is ongoing within the context of a forest restoration project on the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest. Research support has been limited to the development of a web-based application for implementation and general consultation.

Conclusion

There is an increasingly recognized need to engage the interested public in a way that acknowledges varying interests, values and priorities to address complex environmental issues. As such, the process by which the public is engaged is paramount. We argue that the social vulnerability protocol, in part because of its practicality and flexibility, is a worthwhile social science approach for supporting natural resource planning. Methodological flexibility, as demonstrated through our comparison of a sample of the interested public with a sample of agency employees, allows for implementation in a variety of planning contexts and in an experimental manner. Realized and potential benefits include decision-making, public relations and communication, trust-building, and increased potential for practitioner adoption.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the participants and the Forest Planning Team on the Gila National Forest. Also, thank you to the anonymous reviewers for their detailed, encouraging, and helpful insights.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2007. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4):543–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Armatas, C. A. 2013. The importance of water-based ecosystem services derived from the shoshone national forest. Masters thesis, Department of Forest Management. Missoula, MT: The University of Montana. http://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1025/.

- Armatas, C. A. 2019. Pragmatist ecological economics: Focusing on human-nature relationships and social-ecological systems. Dissertation. Department of Society and Conservation. Missoula, MT: The University of Montana. http://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1025/.

- Armatas, C. A. 2020. A public engagement protocol: Social science in support of planning efforts. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. A webinar available at https://www.fs.usda.gov/rmrs/events/upcoming-public-engagement-protocol-social-science-support-planning-efforts.

- Armatas, C. A., A. E. Watson, and W. T. Borrie. 2020. The flathead wild and scenic river system: Results from public engagement asking about human-nature relationships, threats and contributors to such relationships, and opinions about planning and management. Prepared for the Flathead River Wild and Scenic Comprehensive River Management Planning Team. Missoula, MT: Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute.

- Armatas, C. A., T. J. Venn, and A. E. Watson. 2017. Understanding social–ecological vulnerability with Q-methodology: A case study of water-based ecosystem services in Wyoming, USA. Sustainability Science 12 (1):105–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0369-1.

- Armatas, C. A., W. T. Borrie, and A. E. Watson. 2017. Gila National Forest public planning meetings: Results of the ecosystem services station. Missoula, MT: The University of Montana. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fseprd565609.pdf.

- Armatas, C. A., W. T. Borrie, and A. E. Watson. 2019. Protocol for social vulnerability assessment to support national forest planning and management: A technical manual for engaging the public to understand ecosystem service tradeoffs and drivers of change. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-396. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. Available at URL: https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/59038.

- Bauer, N., A. Wallner, and M. Hunziker. 2009. The change of European landscapes: Human-nature relationships, public attitudes towards rewilding, and the implications for landscape management in Switzerland. Journal of Environmental Management 90 (9):2910–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.01.021.

- Beierle, T. C., and J. Cayford. 2002. Democracy in practice: Public participation in environmental decisions. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

- Borrie, W. T., S. F. McCool, and G. H. Stankey. 1998. Protected area planning principles and strategies. In Ecotourims: A guide for planners and managers, ed. K. Lindberg, M. E. Wood, and D. Engeldrum, 2:133–54. North Bennignton, VT: The Ecotourism Society.

- Brown, S. R. 1980. Political subjectivity: Applications of Q methodology in political science. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Brummel, R. F., K. C. Nelson, S. G. Souter, P. J. Jakes, and D. R. Williams. 2010. Social learning in a policy-mandated collaboration: Community wildfire protection planning in the eastern United States. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 53 (6):681–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2010.488090.

- Buchel, S., and N. Frantzeskaki. 2015. Citizens’ voice: A case study about perceived ecosystem services by urban park users in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Ecosystem Services 12 (Supplement C):169–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.11.014.

- Bull, R., J. Petts, and J. Evans. 2008. Social learning from public engagement: Dreaming the impossible? Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 51 (5):701–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09640560802208140.

- Chan, K. M. A., A. D. Guerry, P. Balvanera, S. Klain, T. Satterfield, X. Basurto, A. Bostrom, R. Chuenpagdee, R. Gould, B. S. Halpern, et al. 2012. Where are cultural and social in ecosystem services? A framework for constructive engagement. BioScience 62 (8):744–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2012.62.8.7.

- Chan, K. M. A., T. Satterfield, and J. Goldstein. 2012. Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecological Economics 74:8–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.11.011.

- Cooke, B., and U. Kothari. 2001. Participation: The new tyranny? London, United Kingdom: Zed Books Ltd.

- de Groot, R. S., M. A. Wilson, and R. M. J. Boumans. 2002. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecological Economics 41 (3):393–408. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00089-7.

- Díaz, S., U. Pascual, M. Stenseke, B. Martín-López, R. T. Watson, Z. Molnár, R. Hill, K. M. A. Chan, I. A. Baste, K. A. Brauman, et al. 2018. Assessing nature's contributions to people. Science 359 (6373):270–2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap8826.

- Dvorak, R. G., W. T. Borrie, and A. E. Watson. 2013. Personal wilderness relationships: Building on a transactional approach. Environmental Management 52 (6):1518–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-013-0185-7.

- Dyer, J., L. C. Stringer, A. J. Dougill, J. Leventon, M. Nshimbi, F. Chama, A. Kafwifwi, J. I. Muledi, J.-M K. Kaumbu, M. Falcao, et al. 2014. Assessing participatory practices in community-based natural resource management: Experiences in community engagement from Southern Africa. Journal of Environmental Management 137:137–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.11.057.

- Fischer, A. P., T. Paveglio, M. Carroll, D. Murphy, and H. Brenkert-Smith. 2013. Assessing social vulnerability to climate change in human communities near public forests and grasslands: A framework for resource managers and planners. Journal of Forestry 111 (5):357–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.5849/jof.12-091.

- Flint, C. G., I. Kunze, A. Muhar, Y. Yoshida, and M. Penker. 2013. Exploring empirical typologies of human–nature relationships and linkages to the ecosystem services concept. Landscape and Urban Planning 120:208–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.09.002.

- Hermelingmeier, V., and K. A. Nicholas. 2017. Identifying five different perspectives on the ecosystem services concept using Q methodology. Ecological Economics 136:255–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.01.006.

- Irey, B. T. 2014. Stakeholder perspectives regarding the ecosystem services produced by the frank church - river of No return wilderness in Central Idaho. Master thesis, College of Forestry and Conservation. Missoula, Montana: University of Montana.

- Lawrence, R. L., and D. A. Deagen. 2001. Choosing public participation methods for natural resources: A context-specific guide. Society & Natural Resources 14 (10):857–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/089419201753242779.

- Linnenluecke, M. K., M.-L. Verreynne, M. J. de Villiers Scheepers, and C. Venter. 2017. A review of collaborative planning approaches for transformative change towards a sustainable future. Journal of Cleaner Production 142:3212–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.10.148.

- Luers, A. L. 2005. The surface of vulnerability: An analytical framework for examining environmental change. Global Environmental Change 15 (3):214–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.04.003.

- Martin, S. R., S. F. McCool, and R. C. Lucas. 1989. Wilderness campsite impacts: Do managers and visitors see them the same? Environmental Management 13 (5):623–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01874968.

- McCool, S. F., and K. Guthrie. 2001. Mapping the dimensions of successful public participation in messy natural resources management situations. Society & Natural Resources 14 (4):309–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/713847694.

- Muro, M., and P. Jeffrey. 2008. A critical review of the theory and application of social learning in participatory natural resource management processes. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 51 (3):325–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09640560801977190.

- Murphy, D. J., C. Wyborn, L. Yung, and D. R. Williams. 2015. Key concepts and methods in social vulnerability and adaptive capacity. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-328. Fort Collins, CO: United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

- Norton, B. G. 2012. The ways of wickedness: Analyzing messiness with messy tools. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 25 (4):447–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-011-9333-3.

- Reed, M. S. 2008. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation 141 (10):2417–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014.

- Reed, M. S., A. Graves, N. Dandy, H. Posthumus, K. Hubacek, J. Morris, C. Prell, C. H. Quinn, and L. C. Stringer. 2009. Who's in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. Journal of Environmental Management 90 (5):1933–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.01.001.

- Reed, M. S., S. Vella, E. Challies, J. de Vente, L. Frewer, D. Hohenwallner-Ries, T. Huber, R. K. Neumann, E. A. Oughton, J. Sidoli del Ceno, et al. 2018. A theory of participation: What makes stakeholder and public engagement in environmental management work? Restoration Ecology 26 (S1):S7–S17. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: S7–S17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.12541.

- Rittel, H. W. J., and M. M. Webber. 1973. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences 4 (2):155–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730.

- Rowe, G., and L. Frewer. 2000. Public participation methods: A framework for evaluation. Science, Technology, & Human Values 25 (1):3–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/016224390002500101.

- Rowe, G., and L. J. Frewer. 2005. A typology of public engagement mechanisms. Science, Technology, & Human Values 30 (2):251–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243904271724.

- Steelman, T. A., and L. A. Maguire. 1999. Understanding participant perspectives: Q-methodology in national forest management. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 18 (3):361–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6688(199922)18:3<361::AID-PAM3>3.0.CO;2-K.

- Stenner, P., and R. Stainton-Rogers. 2004. Q methodology and qualiquantology: The example of discriminating between emotions. In Mixing methods in psychology: The integration of qualitative and quantitative methods in theory and practice, ed. Z. Todd, B. Nerlich, S. McKeown, and D. D. Clarke, 101–20. New York: Psychology Press.

- Stephenson, W. 1936. The foundations of psychometry: Four factor systems. Psychometrika 1 (3):195–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02288366.

- Stephenson, W. 1954. The study of behavior: Q-technique and its methodology. Vol. 29. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2281274.

- Talley, J. L., J. Schneider, and E. Lindquist. 2016. A simplified approach to stakeholder engagement in natural resource management. Ecology and Society 21 (4):38. doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08830-210438.

- Tippett, J., J. F. Handley, and J. Ravetz. 2007. Meeting the challenges of sustainable development—A conceptual appraisal of a new methodology for participatory ecological planning. Progress in Planning 67 (1):9–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2006.12.004.

- Turner, B. L. II, 2010. Vulnerability and resilience: Coalescing or paralleling approaches for sustainability science? Global Environmental Change 20 (4):570–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.003.

- United States Department of Agriculture. 2018. Draft land management for the Gila National Forest: Catron, Grant, Hidalgo, and Sierra Counties, New Mexico. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fseprd573667.pdf.

- USDA Forest Service. 2012. National forest system land management. Federal Register 77(68):21162-21276. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- USDA Forest Service. 2017. Final assessment report of ecological/social/economic sustainability conditions and trends: Gila National Forest, New Mexico. Silver City, NM: Gila National Forest.

- Vacik, H., M. Kurttila, T. Hujala, C. Khadka, A. Haara, J. Pykäläinen, P. Honkakoski, B. Wolfslehner, and J. Tikkanen. 2014. Evaluating collaborative planning methods supporting programme-based planning in natural resource management. Journal of Environmental Management 144:304–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.05.029.

- van den Born, R. J., R. Lenders, W. T. De Groot, and E. Huijsman. 2001. The new biophilia: An exploration of visions of nature in western countries. Environmental Conservation 28 (1):65–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892901000066.

- Wagner, R. G., J. Flynn, C. K. Mertz, P. Slovic, and R. Gregory. 1998. Acceptable practices in Ontario’s forests: Differences between the public and forestry professionals. New Forests 16 (2):139–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006577019706.

- Watson, A. E., N. A. Christensen, D. J. Blahna, and K. S. Archibald. 1998. Comparing manager and visitor perceptions of llama use in wilderness. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. https://winapps.umt.edu/winapps/media2/leopold/pubs/341.pdf.

- Watts, S., and P. Stenner. 2012. Doing Q methodological research: Theory, method and interpretation. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.