Abstract

Understanding the interest of local communities and ensuring their support in conservation are pivotal to the sustainability of Protected Areas (PAs). In this study, we interviewed 230 households surrounding the Indawgyi Wildlife Sanctuary (IWS) and assessed community attitudes and conservation involvement against socio-economic background, benefits and costs from the Protected Area (PA), and knowledge. Additionally, we tested how communities’ attitudes toward the PA reflect their actual involvement in PA conservation. Results showed that majority of respondents have positive attitudes toward the IWS and good relationship with its staff. Benefits and costs from the PA were the main influencers of attitudes. Furthermore, findings indicated that 43.9% of respondents were engaged in PA conservation programs and their involvement was mainly determined by benefits gained from the PA. Despite overall positive attitudes, a low level of participation highlighted that attitudes were not strong enough to change into conservation-friendly behaviors. Therefore, a collaborative conservation and sharing more benefits with local communities are important when developing future PA management strategies.

Introduction

Background

Protected areas (PAs) are important for safeguarding biodiversity loss, and support global conservation initiatives which have focused on the expansion of PAs (IPBES Citation2019). Currently, 14.9% (20 million km2) of the earth’s land area and 7% (6 million km2) of marine area are conserved within a global PA network (UNEP-WCMC, IUCN, and NGS Citation2018). Despite this expansion, the declining of biodiversity in these areas is persistent because the established PAs are not effectively managed (Leverington et al. Citation2010). Worldwide anthropogenic disturbances are the primary causes of biodiversity loss (IPBES Citation2019) and putting intense pressure on one-third of global protected areas (Jones et al. Citation2018). Literature on conservation research indicates that the increased level of human-induced threats in PAs is shortcomings of the traditional conservation model, which prioritizes biological values over social values (West, Igoe, and Brockington Citation2006; Lele et al. Citation2010; Andrade and Rhodes Citation2012; Oldekop et al. Citation2016; Schulze et al. Citation2018).

Historically, the “fences and fines approach” has been the focus of the traditional conservation paradigm, in which human activities are considered incompatible with conservation (Andrade and Rhodes Citation2012; Oldekop et al. Citation2016). People living adjacent to PAs were displaced from the conservation areas and restricted in terms of resources access (Lele et al. Citation2010). Due to these restrictions and the lack of alternatives to the resources that are important for local livelihoods, people find different means to illegally enter inside PA in search for natural resources (West, Igoe, and Brockington Citation2006). For instance, the exclusionary approach in the Rajaji-Corbett forest corridor of India has led local communities to set fires and illegally extract resources (Badola Citation1998). Likewise, local people in Mount Cameroon National Park in Cameroon intensified poaching in response to protectionist conservation policies (Nana and Tchamadeu Citation2014). The failure to consider the needs of local communities under “the fences and fines system” may lead to the degradation of PAs’ biodiversity (Kideghesho Citation2010; Newmark and Hough Citation2000).

In Myanmar, 70% of the country’s population inhabits in rural areas and is heavily dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods (Forest Department Citation2015). “Biological resources use” has been the most significant conservation problem within and around PAs in Myanmar. Under this category, the exploitation of non-timber products is scored the highest and widespread over 85% of all PAs. Other threats include fuelwood collection, hunting, fishing, grazing and human settlements are found in more than 50% of them (Rao et al. Citation2002). The threats are mainly due to the subsistence needs of local communities, rather than large scale incompatibilities (Rao et al. Citation2002). Without local community support, the threats to Myanmar’s PA are unlikely to be reduced.

Even though stricter PAs may conserve higher biodiversity, they still need investments and government supports (Gray et al. Citation2016). Moreover, strict protection often implies costs to the local communities, increases antagonism and result in the lack of conservation involvement. In developing countries like Myanmar with limited financial capacity and high natural resource dependency, such a stewardship approach will not be a viable solution (Andrade and Rhodes Citation2012). Considering this, partnership with local communities could be a long-term option for the success of PAs in Myanmar. We, therefore, selected the Indawgyi Wildlife Sanctuary in northern Myanmar as our study area to explore factors affecting attitudes of local communities as well as their participation in the PA conservation. The results may contribute to future PA planning and interventions in order to increase community participation.

Literature Review

Although the definition of attitude differs across disciplines, conservation research has defined an attitude as a human evaluative response of an object (e.g. a PA or a species) with favor or disfavor. A person’s attitude is derived from his or her beliefs, knowledge, experiences and interactions with the attitude object (Allendorf et al. Citation2006; Nilsson, Fielding, and Dean Citation2020). Theories in human dimension studies suggest that attitude can be a strong predictor of a specific behavioral choice (Vaske and Manfredo Citation2012; Nilsson, Fielding, and Dean Citation2020). Previous research on park-people relationships and human-wildlife interactions have observed that people showing positive attitudes are more supportive in conservation initiatives whereas those with negative attitudes are likely to be less-supportive (Infield and Namara Citation2001; Kideghesho, Røskaft, and Kaltenborn Citation2007; Tessema et al. Citation2010; Karanth and Nepal Citation2012; Allendorf Citation2020). However, attitudes are context-dependent as factors influencing attitudes are diverse.

Socio-economic features (gender, ethnicity, education, occupation, land ownership, household income) have been the most common influential factors in attitudes studies (Coad et al. Citation2008; Bragagnolo et al. Citation2016). For instance, male-headed and educated households with diversified income sources are more supportive of conservation than female-headed, less-educated and poorer households (Allendorf et al. Citation2006, Tessema et al. Citation2010). In addition to variation among socio-demographic groups, some scholars found that local communities will not be motivated to be involved in conservation unless “the benefits from the PA outweigh their costs” (Kideghesho, Røskaft, and Kaltenborn Citation2007; Sarker and Røskaft Citation2011; Allendorf et al. Citation2017, Tumusiime et al. Citation2018). Unequal distribution of benefits and costs has been widely acknowledged as a limiting factor for the success of community-based conservation programs in developing countries (Coad et al. Citation2008, Karanth and Nepal Citation2012). Knowledge and social norms have proved to have substantial impacts on people participation in nature and wildlife conservation (Vaske, Donnelly, and Wilkerson Citation2007; Atuo et al. Citation2020). According to Glikman et al. (Citation2012) and Htun, Mizoue, and Yoshida (Citation2012), local residents’ compliance with the PA conservation policy is moderated by their level of knowledge about PA objectives, species, activities, rules and regulations. A clear understanding of these multiple factors associated with community conservation support is essential for the development of effective PA management strategies that can harmonize biodiversity conservation targets and socio-economic needs.

Although there have been some attitudinal studies conducted in Myanmar, most focus has been on the assessment of socio-demographic factors on different attitude statements toward PA management (Allendorf et al. Citation2006, Citation2017, Citation2018; Htun, Mizoue, and Yoshida Citation2012; Hantun Citation2018). A significant knowledge gap remains in a comprehensive understanding of responsible factors (socio-economic factors, benefits, costs and conservation awareness) that influence people’s attitudes and conservation participation. Furthermore, information about the consistency between conservation attitudes and actual conservation behavior is scanting. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by investigating; (1) what factors influence local communities’ attitudes toward the PA and relationships with PA staff, (2) what factors determine local communities’ involvement in the PA conservation, and (3) how well will conservation attitudes translate into actual conservation involvement of local communities.

The following hypotheses were tested;

H1: Local communities who have received benefits from PA will show positive conservation attitudes towards the PA and good relationship with PA staff; in contrast, those who have suffered costs will show negative conservation attitudes and unfarvourable relationship with the park authorities.

H2: Benefit sharing from PA to local communities will encourage communities to participate in conservation, and develop responsible conservation behaviour. Therefore, favourable conservation attitudes will influence local people’s involvement in PA conservation and compliance with PA regulations.

As demography, socio-economy, and conservation knowledge influence people’s attitudes and conservation participation, these variables were included when testing the two hypotheses.

Methodology

Study Area

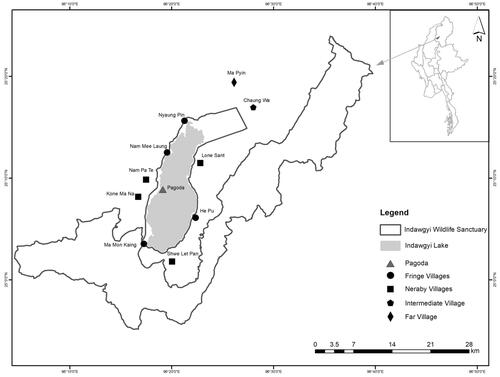

The Indawgyi Wildlife Sanctuary (IWS) is in Mohnyin Township of Kachin State, northern Myanmar with latitudes 24° 56′ N − 25° 24′ N and longitudes 96° E − 96° 39′ E (). It was established in 2004 to protect Indawgyi lake as well as its associated wetlands and forests (Isituto Oikos and BANCA Citation2011). The Indawgyi ecosystem consists of the lake in the center surrounded by wetlands, lakeside grasslands, and hillside watershed forests and covers a total area of 815 km2 (Forest Department Citation2018). As the study area is in the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot, it has high levels of plant and animal endemism and is also included in IUCN category IV to protect the species and habitats of conservation concern. The sanctuary preserves mammals (38 species), birds (448 species), reptiles (41 species), amphibians (34 species), fish (80 species), butterflies (50 species), trees and medicinal plants (165 species) (Isituto Oikos and BANCA Citation2011).

Figure 1. Map of the study area and the distribution of sampled villages. Inset at the right corner is the map of Myanmar with location of Indawgyi Wildlife Sanctuary.

More than 50,000 people live in 36 villages around the sanctuary boundary (Forest Department Citation2018). The local economy is primarily based on agriculture, fishing and secondary income sources include gold mining, gathering of non-timber products, logging, hunting and shifting cultivation (Than Citation2011). Shan is the dominant ethnicity and other ethnic minorities are Kachin and Bamar. Shan communities are mainly engaged in farming while Bamar people rely on fishing and Kachin people practice upland shifting cultivation (Forest Department Citation2018). Although ecotourism is not well developed, thousands of local tourists visit IWS during the pagoda festival season and some villages boarding the lake generate tourism income during that period (Ko, Haputta, and Gheewala Citation2020). Ongoing community-based conservation activities in Indawgyi include community forestry, community fishery, organic farming, tree planting campaigns, sanitation and waste management programs. Awareness-raising is mainly centered in the Indawgyi Wetland Education Center located near the lake. Education programs are also carried out in local schools and villages on important environmental conservation dates (Forest Department Citation2018).

Questionnaire Survey

A survey was conducted from June to August 2019, using a distance-based stratified random sampling. First, relative distances of all villages to the PA boundary were determined using ArcGIS Version 10.5. Next, all the villages were divided into four distance strata; fringe (<1 km), near (1–2 km), intermediate (2–3 km) and far (>5 km) (Sarker and Røskaft Citation2011). According to Yamane Formula, the minimum sample size required for this study using a 95% confidence interval and 5% precision level was 368 (Israel Citation1992). Therefore, we randomly selected 16 villages with four villages in each stratum. Then, 23 households were chosen for face to face interview in each sample village. However, security and logistical constraints during data collection period limited us to complete all villages in the last two strata. Therefore, our total sample size included 230 households from 10 villages (four villages each in the fringe and near categories and one village each in the intermediate and far categories). However, the number of households surveyed represented a minimum 5% of each village population (Supplementary Figure 1).

In each of the selected household, only one family member who (1) was above 18 years old and (2) agreed to participate in the survey was interviewed. A pilot survey was conducted with a few local villagers (not from the sample villages) to test whether the questions were understandable or not. After that, some modifications were made to improve clarity and data quality. All interviews were conducted in the Burmese language as residents were able to understand and speak Burmese very well. A study permit to carry out this research was granted by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, Myanmar prior to data collection.

Operationalization of Variables

A survey questionnaire was designed to be closed-ended and included information on (1) socio-economic variables, (2) perceptions of benefits and costs, (3) knowledge about the PA’s conservation activities, (4) attitudes toward the PA, (5) relationship with PA staff, and (6) conservation involvement of local communities and (7) compliance with PA rules (see supplementary material). Socio-economic variables, perceptions and knowledge were used as independent variables. Attitudes, relationship with park staff, conservation participation and compliance with conservation policies were the principal response variables. Attitudes toward the PA and relationship with the PA staff were measured on a five-point Likert scale through 1 (strongly negative) to 5 (strongly positive). But, they were later pooled into a three-point scale (negative = 1, neutral = 2 and positive = 3) because of very low responses in the two extreme categories. We adopted the research design conducted in Myanmar by Allendorf et al (Citation2006, Citation2012, Citation2018) to make measurements of attitudes, perceptions and knowledge. According to Agidew and Singh (Citation2018) and Paudyal et al. (Citation2018), conservation involvement and compliance with conservation policy were measured in dichotomous responses (no = 0 or yes = 1). Measurement and coding of variables are shown in details in .

Table 1. Summary description and coding of variables.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to understand the nature of collected data and to analyze the frequency distribution of different variables. We performed chi-square analyses to test significant differences between conservation attitudes and relationships with park staff including different categories of independent variables (H1) (). Then, multivariate analyses using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) were followed to find the contribution of independent variables. A GLMM is commonly used for non-normal and non-independent data (Bolker et al. Citation2009, Harrison et al. Citation2018). In this study, we assumed non-independence of data because of stratification i.e. the effects of an unequal number of villages in each stratum. Therefore, the effect of the village was included as a random factor in the model building.

Table 2. Chi-square analyses for (1) attitudes toward the PA and (2) relationship with PA staff against independent variables.

To identify the main determinants of conservation involvement and compliance with the rules and regulations of the PA (H2), we fitted GLMMs with an information-theoretic approach. Potential predictors to be included in the model were determined using chi-square tests. All possible models were then constructed from different sets of potential predictors and candidate models were ranked according to Akaike Information Criteria corrected for small samples (AICc values). The model with the smallest AICc and highest Akaike weight, wi was considered to be the best model (Burnham, Anderson, and Huyvaert Citation2011). As the response variables have binary outcomes, all models assumed binomial distribution error and logit link function. Correlations were examined to satisfy multicollinearity among the potential predictors (r < 0.7) (Harrison et al. Citation2018). The significant level of all statistical analyses was set at p ≤ 0.05. Model selection was carried out in R Studio Version 1.2.5001(R Core Team. Citation2013) and other statistical analyses were performed in SPSS Version 24 (IBM Citation2016).

Demographic Profile of Respondents

Among the 230 respondents, 58.3% were males and 41.7% were females while 77% of them belonged to the Shan ethnicity. 82.6% of the respondents were native residents whereas 17.4% were immigrants to the study area. The primary source of income was farming (70%) followed by fishing (20%) and other occupations (10%). While 60.4% of the respondents were landowners, 39.6% were landless. Of those who owned land, 60% cultivated rice, 12.2% cultivated peanuts and the other 27.8% did not grow any crop or rented their land out to other farmers. In addition to the main occupations, more than half of the respondents were dependent on the resources from the PA for household income supplements ().

Results

Communities’ Knowledge, Perceived Benefits and Costs from the PA

Most respondents, (91.3%) were aware of PA conservation activities and reported that the main objective was to conserve the lake and forest ecosystems. The recorded key species that they knew the PA aimed to conserve included fish (65.2%), birds (61.7%) and other wildlife species such as gibbons, hog deer, muntjacs and wild boars (27.8%). Although 85.2% of the respondents acknowledged the benefits of the PA for the provision of exploitable goods (timber, fuelwood, food and financial aid) and non-exploitable ecosystem services (climate regulation, flood control, cultural and esthetic values), 51.3% claimed that the costs of having this PA in their vicinity were restricted resource access, land conflicts and wildlife crop damage ().

Attitudes toward PA and Its Management

Attitudes toward PA

Overall, 89% of the respondents were positive toward the presence of the PA while 6.5% were neutral, and 4.5% were negative. Respondents’ attitudes toward the PA differed significantly with the distance they lived from the PA (χ2 = 111.88, df = 6, p < 0.001, ). People who live on the fringe and near the PA were more positive than were those living at an intermediate distance and far away (). People who received benefits from the PA showed more positive attitudes than those who received no benefits (χ2 = 21.60, df = 2, p < 0.001). However, people who suffered costs due to the PA displayed more negative attitudes than those who did not suffer any costs from the PA (χ2 = 9.10, df = 2, p = 0.011). Peanut cultivators were more negative than rice farmers (χ2 = 73.64, df = 4, p < 0.001), people who were economically dependent on the PA for forest and fishery products were more negative than those who were less dependent on the PA (χ2 = 13.16, df = 2, p = 0.001), and knowledge-poor individuals were more negative than knowledgeable individuals (χ2 = 8.61, df = 2, p = 0.013) (). In a multivariate analysis, however, only the cost from the PA was significant (coefficient estimate = −1.10, SE = 0.47, p = 0.021) while the other variables were not significant.

Table 3. Distribution of (1) benefits from the PA, (2) costs from the PA, (3) attitudes toward the PA, (4) relationship with PA staff, and (5) conservation involvement among local villages, all in relation to their distances from the PA.

Relationship with PA Staff

Regarding people’s relationship with PA staff, 53.5% had a good relationship, while 24.8% were neutral, and 21.7% had a bad relationship. People’s relationships with the park staff were more desirable in the villages closer to the PA than those who were in the intermediate and farther away villages (χ2 = 105.42, df = 6, p < 0.001) ( and ). Respondents who benefited from the PA indicated better relationships with PA staff than those who got no benefits from the PA (χ2 = 13.61, df = 2, p = 0.001). In contrast, people who suffered costs due to the PA depicted worse relationships with park staff than those who did not suffer any costs from the PA (χ2 = 24.95, df = 2, p < 0.001). Furthermore, people who were conservation-conscious were more positive toward PA staff than those who were not conservation-conscious (χ2 = 9.05, df = 2, p = 0.011). detailed the significant relationships between socio-economic variables and people relationship with staff. In a multivariate analysis, only the effect of the cost from the PA was significant (coefficient estimate = −1.23, SE = 0.49, p = 0.015).

Local Communities’ Involvement in the Conservation of the PA

Involvement in Conservation Activities of the PA

A total of 43.9% of respondents were involved in the conservation activities of the PA which were tree planting, community fishery, waste management and community forestry. Local communities living in the fringe and near villages were more engaged in conservation than were those living in the intermediate and far away villages (χ2 = 26.51, df = 3, p < 0.001) (). Local support for conservation differed significantly depending on whether they were receiving benefits from the PA or not (χ2 = 27.19, df = 1, p < 0.001), whether they had developed conservation awareness or not (χ2 = 13.47, df = 1, p < 0.001), whether they were having positive attitudes toward the PA or not (χ2 = 12.03, df = 2, p = 0.002) and whether they had a good relationship with the PA staff or not (χ2 = 11.26, df = 2, p = 0.004).

Using a GLMM with conservation participation as the dependent variable, we tested conservation involvement with different independent variables; distance from the PA, benefits from the PA, conservation awareness, attitudes toward the PA, and relationships with the PA staff (). Coefficient estimates of the best model showed that benefits from the PA were the strongest contributor (3.38, SE = 1.07, p = 0.002) to conservation participation ().

Table 4. Set of seven most parsimonious generalized linear mixed models including the global model for the prediction of conservation involvement.a

Table 5. Estimates of the best model for the prediction of conservation involvement.

Compliance with the Rules and Regulations of the PA

When the respondents were asked “Are you allowed to collect the resources that your household mainly depends on inside the PA?,” 65.2% answered “yes” while 34.8% answered that they were not officially allowed. The villagers who were economically dependent on the PA (χ2 = 51.69, df = 1, p < 0.001), landless people (χ2 = 7.0, df = 1, p = 0.008), fishermen (χ2 = 47.43, df = 2, p < 0.001) and peanut cultivators (χ2 = 20.4, df = 2, p < 0.001) were more likely to say that they were not allowed to collect resources inside the PA. Furthermore, positive attitudes toward the PA (χ2 = 8.51, df = 2, p = 0.014), good relationships with PA staff (χ2 = 11.26, df = 2, p = 0.004), getting benefits from the PA (χ2 = 5.16, df = 1, p = 0.023), not suffering costs from the PA (χ2 = 4.78, df = 1, p = 0.029) and living farther from the PA (χ2 = 17.35, df = 3, p = 0.001) were also related to people’s compliance with PA rules and regulations.

Using a GLMM, we tested the most important factor explaining people’s compliance with PA rules and regulations from different sets of nine independent variables; income dependency, land ownership, occupation, crop, attitudes toward the PA, relationship with PA staff, perceived benefits and costs from the PA and distance from the PA (). Coefficient estimates of the best model illustrated that economic dependency on the PA was the strongest predictor (−1.84, SE = 0.46, p < 0.001) of the people compliance with rules and regulations of the PA ().

Table 6. Set of seven most parsimonious generalized linear mixed models including the global model for the prediction of people’s compliance with PA rules and regulation.a

Table 7. Estimates of the best model for the prediction of people’s compliance with PA rules and regulations.

Discussion

Attitudes toward PA and Its Management

The majority of respondents had positive attitudes toward the PA while more than half of the respondents had a good relationship with PA staff. Most of these people were from the fringe and near villages. Benefits from the PA and conservation awareness were two common factors influencing people’s positive views toward the PA and its staff. The positive attitudes in the closer villages may be related to their convenient resource access (buffer zone) that was not so easy in villages farther away. Furthermore, conservation support programs, like community fishery and sustainable agriculture, were mainly concentrated in the villages closer to the PA and benefits from such programs in terms of financial or technical assistance could also be credible reasons for their more positive attitudes (Forest Department Citation2018). As stated by Allendorf, Aung, and Songer (Citation2012) and Bragagnolo et al. (Citation2016), such benefits not only improved people’s attitudes but frequent exposure to conservation programs also improved park-people relationship and strengthened their conservation knowledge.

Other attitudinal studies around the world (Sah and Heinen Citation2001; Sarker and Røskaft Citation2011; Karanth and Nepal Citation2012; Bragagnolo et al. Citation2016; Tumusiime et al. Citation2018) also observed a positive connection between benefits from the PA and favorable conservation attitudes. However, the lack of such benefits and the severity of PA-induced costs in the intermediate village resulted in negative attitudes. Many studies have reported that unfavorable conservation attitudes are primarily rooted in the misbalance between benefits and costs that people experienced from the PA (Badola Citation1998; Htun, Mizoue, and Yoshida Citation2012; Karanth and Nepal Citation2012; Tumusiime et al. Citation2018). People from the intermediate village (Chaung Wa) displayed the most negative attitudes because of their loss of land to the PA. Since before the PA was established, inhabitants in Chaung Wa have been using the high-yielding alluvial area in the northern edge of the PA for peanut cultivation during the winter season when the flooded area shrank. People in Chaung Wa switched their occupations between peanut cultivation in the dry season and fishing in other seasons alternately (Htay and Røskaft Citation2020).

Establishment of PA and conservation of bird habitats restricted land use in the alluvial area which caused land-use conflicts between the park and Chaung Wa people. As agriculture is the main occupation in the study area, the loss of customary land adversely affects the livelihoods of local communities (Ambastha, Hussain, and Badola Citation2007; Htun, Mizoue, and Yoshida Citation2012; Aung et al. Citation2015). Although some extent of land was excluded and some were compensated outside the PA (Forest Department Citation2018), villagers claimed that they did not get the same size of land they lost due to the park designation. Furthermore, crop yields were reduced because replacement land was fallow vacant land with low fertility. Some respondents mentioned that villagers who continued using their land were imprisoned due to encroaching the PA. This suggests that the exclusionary approach ignoring the needs of the local communities (fences and fines) would result in negative attitudes and undesirable consequences for PA management (Fiallo and Jacobson Citation1995; Wells and McShane Citation2004; Ward, Holmes, and Stringer Citation2018; Park et al. Citation2020).

The unequal distribution of PA-driven benefits and costs among local villages was found to be the primary cause of negative conservation attitudes as Sarker and Røskaft (Citation2011) found in four PAs in Bangladesh. We found that most people in far villages expressed either neutral or positive attitudes due to the low level of PA-driven socio-economic losses. Findings of Ansong and Røskaft (Citation2011) in Ghana also suggested that people’s attitudes would remain positive or neutral when the costs from the PA became negligible. Our findings on attitude differences among study villages in the IWS point out the challenge for balancing benefits and costs of conservation, and future management strategies should focus on narrowing down the costs to ameliorate the negative attitudes of people in its vicinity.

Securing land tenure rights outside the PA is very important to reduce land-use conflicts and its associated costs (Sah and Heinen Citation2001). Furthermore, we also found some socio-economic moderating factors on people’s relationship with park authorities. Unlike indigenous Shan communities who were primarily engaged in agriculture, migrant Bamar people were usually landless and engaged in fishing as their main occupations (Than 2010). Most of these fishermen expressed negative attitudes toward the PA staff’s patrolling efforts in the lake because such activities caused them difficulties for fishing, especially in the fish spawning season when fishing is not allowed. Nonetheless, fishermen illegally encroach into the lake inside the PA due to their lack of alternative livelihood options. Again, stricter legal actions against illegal fishing from the PA accelerated antagonism and worsened their attitudes when they were arrested and punished (Hantun Citation2018). As retaliation for their losses, fishermen destroyed the boundary pillars or illegally harvested PA resources at night time. This finding suggests that strong conservation incentives or alternative income streams that could fulfill livelihood needs are required to change their negative opinions (Badola Citation1998; Sah and Heinen Citation2001).

Local Communities’ Involvement in the Conservation of the PA

Respondents from the fringe and near villages participated more in the conservation activities than did those from the intermediate and far villages. More conservation involvement in the vicinity of the PA can be attributed to a higher perception of benefits, frequent interaction with conservation programs, positive attitudes toward the PA and better relationship with park staff. These underlying factors are in line with those reported by previous community-based conservation studies in Ethiopia (Tessema et al. Citation2010), Myanmar (Allendorf, Aung, and Songer Citation2012), Lao PDR (Sirivongs and Tsuchiya Citation2012) and Nepal (Lamsal et al. Citation2015; Paudyal et al. Citation2018). However, overall conservation involvement was relatively low in comparison with the overwhelmingly positive conservation attitudes. As shown in the model analysis, attitudes toward the PA and relationship with the PA staff did not significantly contribute to the best prediction of conservation involvement. This means that people’s positive attitudes toward the PA and park staff were not strong enough to translate into actual conservation participation.

When people are limited in their livelihood options, a positive attitude cannot truly change into environmentally responsible behavior (Badola Citation1998; Infield and Namara Citation2001; Bragagnolo et al. Citation2016). Nepal and Spiteri (Citation2011) reported that people who are struggling for survival need hardly prioritize conservation in the first place. Additionally, benefits from the PA as the strongest predictors of conservation involvement explained that people’s conservation participation depends on whether their basic livelihood needs are fulfilled or not. Results from our first model suggest that local support for conservation will not be guaranteed unless the conservation ensures benefits to them. On the other hand, 34.8% of the respondents still collect resources from the PA in restricted places and periods, although they are not officially allowed. Most were fishermen and people who were economically dependent on the PA for their survival needs. People who are economically dependent on the PA for their family needs were less likely to comply with regulations of the PA. During the interview, fishermen admitted illegal fishing due to their lack of substitutes for their livelihood needs. People will not follow the rules and regulations of the PA when their survival chance becomes limited (Nepal and Spiteri Citation2011; Bragagnolo et al. Citation2016). Illegal fishermen are active during the night so that they can avoid the risk of being arrested by the patrol team. Although key informant groups were formed for reporting illegal activities, villagers said that they sympathize with each other over their family needs, and some responded that they are afraid of being harmed by the people who undertake illegal practices. Hantun (Citation2018) found a similar phenomenon in Moeyungyi Wetland Sanctuary in lower Myanmar.

We found the inconsistency between people’s attitudes and conservation support which explains that positive attitudes alone will not be enough to upgrade conservation efforts in the IWS. However, overall positive attitudes will be a good foundation in promoting local conservation support if appropriate benefits streams are to be provided (Allendorf Citation2020). Although our results indicated that benefits could function as strong incentives for conservation involvement, such benefits should be sufficient enough to be seen as a motivational factor in the perspective of local communities. Moreover, community support programs should be conservation-oriented with no undesirable environmental leakages (Wells and McShane Citation2004; Kideghesho, Røskaft, and Kaltenborn Citation2007). Ecotourism is a promising livelihood strategy in the IWS, yet it is not very well developed. Many studies elsewhere suggested the great potential of ecotourism in promoting local development and community involvement in conservation (Sodhi et al. Citation2010; Nepal and Spiteri Citation2011; Sirivongs and Tsuchiya Citation2012; Lamsal et al. Citation2015; Paudyal et al. Citation2018).

In the study area, few villages bordering the pagoda area received some ecotourism benefits by selling local products, handicrafts, provision of temporary accommodation and logistics to the visitors (Forest Department Citation2018). Respondents from other villages also discussed the likelihood of ecotourism as a sustainable option for local development and wanted to be involved in as part of the ecotourism development. However, a lack of basic infrastructure in those villages limits them from becoming involved in ecotourism. Furthermore, current PA conservation activities are confined to the nearby villages and excluded those located relatively far. This may also be one reason for the low level of conservation participation. Despite this, we have found a high level of conservation awareness and its significant contribution to local participation. In this regard, the provision of appropriate PA conservation programs can be a catalyst for future PA conservation achievements. It is therefore suggested that expansion of ecotourism and distribution of its benefits to all possible villages could improve community participation in the conservation of the IWS (Ko, Haputta, and Gheewala Citation2020).

Limitations of the Study

This study, like most other studies, has some limitations. Community attitudes and conservation participation can be influenced by many factors including spatial, demographic, economic, knowledge, socio-cultural and psychological variables. As we tested the effects of only a limited number of spatial and socio-demographic factors, perception of benefits and costs and general conservation knowledge, our results must be evaluated in the light of these limitations. Furthermore, we measured only people’s general attitudes toward PA and predicted conservation involvement based on their general attitudes. Prediction on local conservation involvement will be a stronger element if attitude assessments were targeted toward specific conservation programs (Vaske and Manfredo Citation2012; Nilsson, Fielding, and Dean Citation2020). It would therefore probably be better if we had measured the attitudes and participation more rigorously and incorporated our tests based on the theory of planned behavior. Therefore, if similar studies are to be conducted in the future, they should incorporate these narratives to validate this finding and in addition, the assessment of PA management effectiveness. We also admit the limitation of data precision due to small sample size, unequal sample weight and the specific geographical context. Therefore, caution should be taken in formulating conclusions and generalizations. Further studies with more representative sample sizes are suggested to validate our findings.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Attitudes toward the PA are mainly influenced by the net effect of benefits and costs people experienced from the PA while socio-economic factors and awareness of PA conservation activities function as covariates. People living in the fringe and near villages got more benefits and fewer costs, thus exhibit more positive attitudes. In contrast, the intermediate village that gained the fewest benefits and the greatest costs portrays more negative attitudes. Among all study villages, both benefits and costs were lowest in the far village which result in either neutral or positive attitudes. Although there is a positive relationship between attitudes and conservation involvement, positive attitudes cannot fully translate into positive conservation behaviors. People with limited livelihood options cannot follow the rules and regulations of the PA.

This study showed that the benefit from PA is the main determinant of conservation participation. We, therefore, conclude that local support for conservation will be enhanced through the provision of benefits from systematic resource utilization in the respective zones of the PA or community support programs. Furthermore, we recommend that PA conservation programs should not be concentrated to only nearby villages but should be spread out to include more villages. Although the benefits are found to be the main determinant of community conservation involvement, the effectiveness of these benefits in promoting conservation involvement has yet to be covered. Therefore, future research on the effectiveness of different community conservation initiatives is strongly suggested. Based on this study, we conclude that future PA management decisions will need collaborative conservation approaches that could satisfy competing interests of different stakeholders to achieve desired socio-biological outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Myanmar Forest Department and Indawgyi Wildlife Sanctuary for their support during data collection. We would also like to thank the interviewees for participating in the household survey. Last but not least, we acknowledge advice and suggestions given by editors and reviewers in shaping this work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agidew, A. M. A., and K. N. Singh. 2018. Factors affecting farmers’ participation in watershed management programs in the Northeastern highlands of Ethiopia: A case study in the Teleyayen sub-watershed. Ecological Processes 7 (1):1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-018-0128-6.

- Allendorf, T. E. R. I., K. K. Swe, T. Oo, Y. E. Htut, M. Aung, M. Aung, K. Allendorf, L.-A. Hayek, P. Leimgruber, and C. Wemmer. 2006. Community attitudes toward three protected areas in Upper Myanmar (Burma). Environmental Conservation 33 (4):344–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892906003389.

- Allendorf, T. D. 2020. A global summary of local residents’ attitudes toward protected areas. Human Ecology 48 (1):111–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-020-00135-7.

- Allendorf, T. D., M. Aung, and M. Songer. 2012. Using residents’ perceptions to improve park-people relationships in Chatthin Wildlife Sanctuary, Myanmar. Journal of Environmental Management 99:36–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.01.004.

- Allendorf, T. D., M. Aung, K. K. Swe, and M. Songer. 2017. Pathways to improve park-people relationships: Gendered attitude changes in Chatthin Wildlife Sanctuary, Myanmar. Biological Conservation 216:78–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.10.005.

- Allendorf, T. D., K. K. Swe, M. Aung, and A. Thorsen. 2018. Community use and perceptions of a biodiversity corridor in Myanmar’s threatened southern forests. Global Ecology and Conservation 15:e00409. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00409.

- Ambastha, K., S. A. Hussain, and R. Badola. 2007. Resource dependence and attitudes of local people toward conservation of Kabartal wetland: A case study from the Indo-Gangetic plains. Wetlands Ecology and Management 15 (4):287–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-006-9029-z.

- Andrade, G. S. M., and J. R. Rhodes. 2012. Protected areas and local communities: An inevitable partnership toward successful conservation strategies? Ecology and Society 17 (4):14. doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05216-170414.

- Ansong, M., and E. Røskaft. 2011. Determinants of attitudes of primary stakeholders towards forest conservation management: A case study of Subri Forest Reserve, Ghana. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management 7 (2):98–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2011.613411.

- Aung, P. S., Y. O. Adam, J. Pretzsch, and R. Peters. 2015. Distribution of forest income among rural households: A case study from Natma Taung national park, Myanmar. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods 24 (3):190–201. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2014.976597.

- Atuo, F. A., J. Fu, T. J. O’Connell, J. A. Agida, and J. A. Agaldo. 2020. Coupling law enforcement and community-based regulations in support of compliance with biodiversity conservation regulations. Environmental Conservation 47 (2):104–12. 92920000107 doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S03768.

- Badola, R. 1998. Attitudes of local people towards conservation and alternatives to forest resources: A case study from the lower Himalayas. Biodiversity and Conservation 7 (10):1245–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008845510498.

- Bolker, B. M., M. E. Brooks, C. J. Clark, S. W. Geange, J. R. Poulsen, M. H. H. Stevens, and J. S. S. White. 2009. Generalized linear mixed models: A practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 24 (3):127–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008.

- Bragagnolo, C., A. C. M. Malhado, P. Jepson, and R. J. Ladle. 2016. Modelling local attitudes to protected areas in developing countries. Conservation and Society 14 (3):163–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.191161.

- Burnham, K. P., D. R. Anderson, and K. P. Huyvaert. 2011. AIC model selection and multimodel inference in behavioral ecology: Some background, observations, and comparisons. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 65 (1):23–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-010-1029-6.

- Coad, L., A. Campbell, L. Miles, and K. Humphries. 2008. The costs and benefits of forest protected areas for local livelihoods: A review of the current literature. Cambridge, UK: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre. https://www.unep-wcmc.org.

- Fiallo, E. A., and S. K. Jacobson. 1995. Local communities and protected areas: Attitudes of rural residents towards conservation and Machalilla National Park, Ecuador. Environmental Conservation 22 (3):241–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S037689290001064X.

- Forest Department. 2015. National biodiversity strategy and action plan 2015-2020. Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar. https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/mm.

- Forest Department. 2018. The management plan of Indawgyi Wildlife Sanctuary. Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar: Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation.

- Glikman, J. A., J. J. Vaske, A. J. Bath, P. Ciucci, and L. Boitani. 2012. Residents’ support for wolf and bear conservation: The moderating influence of knowledge. European Journal of Wildlife Research 58 (1):295–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-011-0579-x.

- Gray, C. L., S. L. L. Hill, T. Newbold, L. N. Hudson, L. Börger, S. Contu, A. J. Hoskins, S. Ferrier, A. Purvis, and J. P. W. Scharlemann. 2016. Local biodiversity is higher inside than outside terrestrial protected areas worldwide. Nature Communications 7 (1):12306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12306.

- Hantun, Z. 2018. Attitudes of local communities towards the conservation of a wetland protected area: A case study from the Moeyungyi Wetland Wildlife Sanctuary in Myanmar. Master thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway. https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/handle/11250/2503669.

- Harrison, X. A., L. Donaldson, M. E. Correa-Cano, J. Evans, D. N. Fisher, C. E. D. Goodwin, B. S. Robinson, D. J. Hodgson, and R. Inger. 2018. A brief introduction to mixed-effects modelling and multi-model inference in ecology. Peerj. 6 (5):e4794–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4794.

- Htay, T., and E. Røskaft. 2020. Community dependency and perceptions of a protected area in a threatened ecoregion of Myanmar. International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation 12 (4):240–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.5897/IJBC.2020.1429.

- Htun, N. Z., N. Mizoue, and S. Yoshida. 2012. Determinants of local people’s perceptions and attitudes toward a protected area and its management: A case study from Popa Mountain Park, Central Myanmar. Society & Natural Resources 25 (8):743–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2011.620597.

- IBM. 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Infield, M., and A. Namara. 2001. Community attitudes, and behaviour towards conservation: An assessment of a community conservation programme around Lake Mburo, National Park, Uganda. Oryx 35 (1):48–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3008.2001.00151.x.

- Isituto Oikos and BANCA. 2011. Myanmar protected areas; context, current status and challenges. Instituto Oikos, Milano Ancora Libri, Italy.

- IPBES. 2019. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. https://ipbes.net/global-assessment.

- Israel, G. D. 1992. Determining sample size. Gainesville, FL: Florida Cooperative Extension Services, University of Florida.

- Jones, K. R., O. Venter, R. A. Fuller, J. R. Allan, S. L. Maxwell, P. J. Negret, and J. E. M. Watson. 2018. One-third of global protected land is under intense human pressure. Science 360 (6390):788–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9565.

- Karanth, K. K., and S. K. Nepal. 2012. Local residents perception of benefits and losses from protected areas in India and Nepal. Environmental Management 49 (2):372–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-011-9778-1.

- Kideghesho, J. R. 2010. ‘Serengeti shall not die’: Transforming an ambition into a reality. Tropical Conservation Science 3 (3):228–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291000300301.

- Kideghesho, J. R., E. Røskaft, and B. P. Kaltenborn. 2007. Factors influencing conservation attitudes of local people in Western Serengeti, Tanzania. Biodiversity and Conservation 16 (7):2213–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-006-9132-8.

- Ko, C. O., P. Haputta, and S. H. Gheewala. 2020. Estimation of the value of direct use ecosystem services of Indawgyi Lake Wildlife Sanctuary in Myanmar. Journal of Sustainable Energy & Environment 11:11–20.

- Lamsal, P., K. P. Pant, L. Kumar, and K. Atreya. 2015. Sustainable livelihoods through conservation of wetland resources: A case of economic benefits from Ghodaghodi Lake, western Nepal. Ecology and Society 20 (1):10. doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07172-200110.

- Lele, S., P. Wilshusen, D. Brockington, R. Seidler, and K. Bawa. 2010. Beyond exclusion: Alternative approaches to biodiversity conservation in the developing tropics. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2 (1-2):94–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2010.03.006.

- Leverington, F., K. L. Costa, H. Pavese, A. Lisle, and M. Hockings. 2010. A global analysis of protected area management effectiveness. Environmental Management 46 (5):685–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-010-9564-5.

- Nana, E. D., and N. N. Tchamadeu. 2014. Socio-economic impacts of protected areas on people living close to the Mount Cameroon national park. Parks 20 (2):129–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2014.PARKS-20-2.EDN.en.

- Nepal, S., and A. Spiteri. 2011. Linking livelihoods and conservation: An examination of local residents’ perceived linkages between conservation and livelihood benefits around Nepal’s Chitwan National Park. Environmental Management 47 (5):727–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-011-9631-6.

- Newmark, W. D., and J. L. Hough. 2000. Conserving Wildlife in Africa: Integrated Conservation and Development Projects and Beyond. BioScience 50 (7):585–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0585:CWIAIC]2.0.CO;2.

- Nilsson, D., K. Fielding, and A. J. Dean. 2020. Achieving conservation impact by shifting focus from human attitudes to behaviors. Conservation Biology 34 (1):93–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13363.

- Oldekop, J. A., G. Holmes, W. E. Harris, and K. L. Evans. 2016. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conservation Biology 30 (1):133–41.

- Park, S., S. Zielinski, Y. Jeong, and S. Kim. 2020. Factors affecting residents’ support for protected area designation. Sustainability 12 (7):2800–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072800.

- Paudyal, R., B. Thapa, S. S. Neupane, and K. C. Birendra. 2018. Factors associated with conservation participation by local communities in Gaurishankar Conservation Area Project, Nepal. Sustainability 10 (10)17–19.3488. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su1010:.

- R Core Team. 2013. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/.

- Rao, M., A. Rabinowitz, and S. T. Khaing. 2002. Status review of the protected-area system in Myanmar, with recommendations for conservation planning. Conservation Biology 16 (2):360–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00219.x.

- Sah, J. P., and J. T. Heinen. 2001. Wetland resource use and conservation attitudes among indigenous and migrant peoples in Ghodaghodi Lake area, Nepal. Environmental Conservation 28 (4):345–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892901000376.

- Sarker, A. H. M. R., and E. Røskaft. 2011. Human attitudes towards the conservation of protected areas: A case study from four protected areas in Bangladesh. Oryx 45 (3):391–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605310001067.

- Schulze, K., K. Knights, L. Coad, J. Geldmann, F. Leverington, A. Eassom, M. Marr, S. H. M. Butchart, M. Hockings, and N. D. Burgess. 2018. An assessment of threats to terrestrial protected areas. Conservation Letters 11 (3):e12345. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12435.

- Sirivongs, K., and T. Tsuchiya. 2012. Relationship between local residents’ perceptions, attitudes and participation towards national protected areas: A case study of Phou Khao Khouay National Protected Area, central Lao PDR. Forest Policy and Economics 21:92–100. 2012.04.003. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.

- Sodhi, N. S., T. M. Lee, C. H. Sekercioglu, E. L. Webb, D. M. Prawiradilaga, D. J. Lohman, N. E. Pierce, A. C. Diesmos, M. Rao, and P. R. Ehrlich. 2010. Local people value environmental services provided by forested parks. Biodiversity and Conservation 19 (4):1175–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9745-9.

- Tessema, M. E., R. J. Lilieholm, Z. T. Ashenafi, and N. Leader-Williams. 2010. Community attitudes toward wildlife and protected areas in Ethiopia. Society & Natural Resources 23 (6):489–506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920903177867.

- Than, Z. M. 2011. Socio-economic analysis of the Indawgyi Lake Area, Moehnyin Township. Master Thesis. University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany.

- Tumusiime, D. M., P. Byakagaba, M. Tweheyo, and N. Turyahabwe. 2018. Predicting attitudes towards protected area management in a developing country context. Journal of Sustainable Development 11 (6):99. doi:https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v11n6p99.

- UNEP-WCMC, IUCN, and NGS. 2018. Protected planet report: Tracking towards global targets for protected areas. Cambridge, UK; Gland, Switzerland; and Washington, DC: UNEP-WCMC, IUCN and NGS. https://livereport.protectedplanet.net.

- Vaske, J. J., M. P. Donnelly, and C. Wilkerson. 2007. Public knowledge and perceptions of the desert tortoise. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University.

- Vaske, J. J., and M. J. Manfredo. 2012. Social psychological considerations in wildlife management. In Human dimensions of wildlife management, ed. D. J. Decker, S. J. Riley, and W. F. Siemer, 2nd ed., 43–5. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Ward, C., G. Holmes, and L. Stringer. 2018. Perceived barriers to and drivers of community participation in protected-area governance. Conservation Biology 32 (2):437–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13000.

- Wells, M. P., and T. O. McShane. 2004. Integrating protected area management with local needs and aspirations. Ambio 33 (8):513–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-33.8.513.

- West, P., J. Igoe, and D. Brockington. 2006. Parks and peoples: The social impact of protected areas. Annual Review of Anthropology 35 (1):251–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9745-9.