Abstract

Efforts to manage conservation conflicts are typically focused on reconciling disputes between opposing stakeholders over conservation objectives. However, this is an oversimplification of conflict dynamics, driven by the difficulties of understanding and addressing deeper-rooted issues. In this study, an ethnographic approach using a combination of informal discussions, participant observation, and in-depth interviews was used to examine local stakeholder narratives around a conservation conflict over grouse shooting and raptor conservation. Analysis highlighted three main narratives – cooperation, resistance, and despondence, that served as a basis for individuals to justify their responses to conflict: to work toward collaboration, act antagonistically, or avoid. Our analysis suggests that the current status quo in conflict management serves to reinforce antagonistic positions. We recommend a more nuanced approach to understanding stakeholder decision-making that goes beyond superficial disputes to recognize diversity within stakeholder groups, access hidden voices, and encompass the wider socio-political context.

Introduction

Wildlife management, land-use and the conservation of nature involve a diversity of people and interests, with different and often conflicting opinions of the natural world and how it should, or should not, be managed (Redpath, Gutiérrez, et al. Citation2015; Mason et al. Citation2018). As conflicts are often framed around distinct stakeholder groups with divergent goals, objectives or world views, it follows that the management of conflicts in practice is largely focused on bringing representatives of the opposed parties together to foster constructive dialogue, develop joint solutions, share knowledge and reconcile their differences (Butler et al. Citation2015; Ainsworth et al. Citation2020).

In recent years, however, the literature on conservation conflicts has increasingly recognized that seeing conflicts as clashing interests or values relating to nature is an oversimplification (Mason et al. Citation2018; von Essen and Allen Citation2020). Although conflicts do involve conservation-related disputes, they also stem from – and are exacerbated by – a highly complex and multi-dimensional suite of issues that go beyond these arguments. These include, but are not limited to, cultural or social norms (De Pourcq et al. Citation2019), political histories (Mathevet et al. Citation2015), fractured relationships and diminished trust (Young et al. Citation2016a), entrenched societal inequities (Kashwan Citation2017), and power asymmetries (Raik, Wilson, and Decker Citation2008). Therefore the decision of how to act in a conflict situation – how to interact, which “strategy” to adopt, and who to trust – is likely not based on group or individual interests alone, but also on attitudes and judgements based on past events, and the wider socio-political context (Madden and McQuinn Citation2014; Bergius, Benjaminsen, and Widgren Citation2018). Ignoring or overlooking these elements risks causing further polarization (von Essen and Allen Citation2020).

An in-depth, nuanced approach to stakeholder analyses allows for these more subtle arguments to become apparent, highlighting future avenues for management that could be more productive than the current trajectory of reinforcing antagonistic positions. Studies have used experimental games (Rakotonarivo et al. Citation2020), Q-methodology (Rust et al. Citation2017) and participatory social-network mapping (Jin et al. Citation2021) to better understand stakeholder motivations and decision-making relating to conservation conflicts. Here, we use the conceptual framing of Harrison and Loring (Citation2020), which defines conservation conflicts as stories with numerous, inter-related storylines told from multiple perspectives. This framing aligns with the view of conflicts as dynamic processes with complex histories and multiple facets (Cusack et al. Citation2021). If we are to understand conflicts as stories – built and sustained by the different ways in which actors see the world – then examining narratives provides useful insight into their underlying causes. Narratives are a mode of communication, where diverse events are drawn together and retold in a way that conveys a certain interpretation of reality (Benjaminsen and Svarstad Citation2010; Ingram, Ingram, and Lejano Citation2019). Analyzing the events an individual chooses to recall, and how they are linked, can reveal complicated relationships between social, political and environmental factors that may otherwise be overlooked (Bixler Citation2013). Through narrative analysis, we may gain insight into people’s responses to conflict, and the meaning and motivations behind them (Bruner Citation1993).

In this study, we analyzed narratives of stakeholders associated with a highly contentious conservation conflict in Scotland, UK, which concerns land management for the sport of driven grouse shooting and, predominantly, the conservation of birds of prey (or “raptors”). Despite protective legislation, many species of raptor are persecuted to prevent the predation of a valuable game-bird, red grouse (Thirgood and Redpath Citation2008). Driven grouse shooting has become an increasingly controversial practice over the last few decades; the ongoing illegal persecutionFootnote1 of raptors has sparked national debate, in conjunction with other concerns as to the environmental impact of grouse moor management (Hodgson et al. Citation2018). A shift in environmental governance – whereby responsibility for land management decisions has been devolved from private land ownership to more networked modes of governance – has broadened the involvement of stakeholders in decision-making processes to non-governmental organizations and government bodies (Dinnie, Fischer, and Huband Citation2015). Combined with a wider societal and political shift toward more “pro-conservation” discourses (Romsdahl et al. Citation2017), conflicts have emerged around Scottish land use, access and rights, as well as wildlife management and species impact (Fischer and Marshall Citation2010; Dinnie, Fischer, and Huband Citation2015). Several attempts at reconciliation have failed to achieve long-lasting solutions to the problem, pointing to the need to delve deeper into stakeholder perspectives and decision-making, acknowledging that the unresolved issues transcend focal disputes between pro-shooting and pro-conservation interests (Hodgson et al. Citation2018). Conflict escalation and persistence in Scotland, and the need for in-depth social and political analyses of this case study reflects that of other conservation conflicts globally, including wolves and hunting in Scandinavia (Von Essen et al. Citation2015), seal protection and human recreation in California (Konrad and Levine Citation2021) and people-park conflicts in Ghana (Soliku and Schraml Citation2020).

We contribute to the global ddebate on conservation conflict management and stakeholder interaction by applying an ethnographic approach, including participant observation, informal discussions, and in-depth interviews with land managers and raptor conservationists to identify core narratives and better understand the different events and experiences that have led to certain interpretations of the conflict, and stakeholder responses to management. Our findings carry important implications for changing the status quo regarding current global trends in conflict management, especially regarding multi-stakeholder forums, and we identify avenues toward more constructive processes.

Conflicts as Stories: Narrative Analysis

Mishler (Citation1991) – one of the leading scholars of narrative psychology – describes narratives as “…individuals’ contextual understanding of their problems, in their own terms” (142). Narratives therefore do not accurately reflect reality, but rather how an individual experienced an event and made sense of it (Svarstad Citation2002). They can be used to convey a certain message, justify actions and behaviors or bring others round to a specific way of thinking (Bennett Citation2019). Researchers in the social and political sciences have highlighted the advantages of the narrative concept as an accessible way of understanding people’s realities and motivations, as well as exploring perspectives that may otherwise be lost in more standard assessments of stakeholder decision-making (Cieslik, Dewulf, and Buytaert Citation2020).

In social science, a central aspect of a narrative is chronology in that events are retold in a sequential order. Narratives therefore have a distinct structure – a beginning, middle and end, or a clear line of argumentation with a premise and conclusion (Roe Citation1994). Although we acknowledge the importance of chronology, we also agree with Cieslik, Dewulf, and Buytaert (Citation2020) in that causality sometimes takes precedence over chronology. Our methodology is therefore more in line with that of Elliot (Citation2005), who distinguishes between narrative analysis for social context, for form, and for content. Social context examines how and where stories are told, whereas form analysis is more concerned with structural elements such as order, plot and genre. Here, we are most interested in understanding the content of the narrative, in particular how stakeholders establish causal links between events, actors, and remembered facts to justify their own actions. This type of analysis also allows for comparison between individuals, and for commonalities to be drawn to establish patterns within groups of people (Czarniawska Citation2004). For the purpose of our research, we examine how individuals construct a premise based on their experiences and interactions within the conflict, and how they establish causality between these events to reach a conclusion on the “right” way to act within the conflict.

Methods

Based on an initial conflict mapping exercise (Hodgson et al. Citation2018) we identified “key” stakeholders, including gamekeepers (responsible for the upkeep of private sporting estates), landowners, and raptor monitors (responsible for the collection of data regarding raptor populations). We focused on “local” stakeholder groups as there is a paucity of data regarding the perspectives of these groups (Swan et al. Citation2020), chosen on the basis that they were not part of national-level dialogue initiatives and worked predominantly at ground level. To obtain a diverse range of perspectives, participants were selected from locations across Scotland where there were high concentrations of grouse shooting estates, and a diversity of shooting practices (e.g. driven shooting, walked-up shooting and deer stalking). In the interests of participant confidentiality, exact locations cannot be released. Purposive sampling was used initially, based on contacts established during previous work and through relevant organizations and interest groups e.g. Regional Moorland Groups and Scottish Raptor Study Groups. A “snowball” technique was then employed, whereby existing participants were asked to provide contacts of others with relevant perspectives (Bryman Citation2004). Fieldwork was carried out from February 2016 to August 2017.

For the purpose of this research, which involved a conflict where some behavior could be perceived as “wrong” or deemed socially unacceptable, such as wildlife crime and acts of resistance (Von Essen et al. Citation2014), we chose a two-stage interview process, consisting of: (1) ethnographic interviews and (2) recorded, semi-structured interviews. Ethnographic interviews are a form of participant observation that take place in an informal setting, and often consist of loosely structured discussions to allow participants the freedom to raise topics they believe to be of relevance and importance to the situation (Berg Citation2004). Ethnographic approaches are, for example, often used in peace research and the examination of other sensitive subjects, as they allow researchers to engage with individual and community experiences within a local context, and in a relatively relaxed and “safe” environment for the participant (Millar Citation2018). In the context of this study, sessions consisted of activities held in a variety of settings, such as hill walks, monitoring expeditions, and manual estate work. Some took place with individuals, whereas others were in a group setting. Interviews with 19 gamekeepers, 18 raptor monitors and 5 estate workers who did not identify as “gamekeepers” (e.g. deer stalker, ghillie, or estate owner) (total n = 42) were completed. Each participant was interviewed twice. These ethnographic interviews were not audio-recorded, but detailed notes were taken from each session which later provided social context to inform guidelines for the second stage of the study (semi-structured interviews). Further – and relevant to the highly sensitive nature of this conflict –trust was built in the study and the research team, which encouraged openness and transparency in participants regarding their experiences. Confidentiality was maintained through the generation of numbered “codes” for each participant.

Semi-structured interviews were designed to complement the ethnographic study, and interview guides were constructed to focus on key topics raised by participants of the ethnographic stage ( for example interview guide). These topics covered individual perceptions of the conflict, relationships with members of the community and other communities, perceptions of national actors (NGOs and governments), and participant engagement with conflict management methods. Of the 42 contacts included in the ethnographic stage, 20 individuals − 10 raptor monitors, and 10 gamekeepers – were selected at random to minimize bias. The smaller sample size was chosen to allow for a more in-depth exploration of the issues raised during the ethnographic discussions, under the time period of the present study. Interviews took place in a one-to-one setting, and were audio recorded.

Interview recordings (n = 20) were transcribed verbatim, and transcripts analyzed using the software NVivo (v.11). We applied a two-stage narrative analysis. Data were first subjected to a thematic narrative analysis, which identifies and explores the content of a narrative including the recurring elements which constitute the narrative (Allen, Citation2017). In this stage, we established the overall premise of the narrative, and its conclusion. Transcripts were analyzed line-by-line, common themes extracted and codes developed based on these themes (). A further dialogic narrative analysis was then conducted, to examine ideas about causality between the events and actors described under these themes, and to understand how the narrative related to larger discourses and the wider context of the conflict (Allen, Citation2017). Following the analysis, details of the themes and narratives were disseminated to all participants with an accompanying form for feedback, and findings were presented to various relevant organizations (e.g. regional raptor monitoring groups and local moorland management groups) to test the legitimacy and validity of the results. Themes and narratives were then adjusted accordingly.

Results

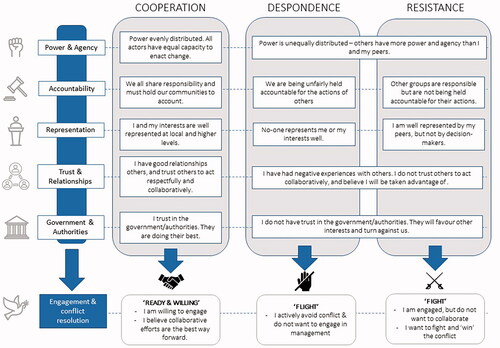

Three overarching narratives emerged from the interview data: resistance, despondence, and cooperation (), based on six themes (on the left-hand side of ), which recurred throughout each narrative and therefore formed their “building blocks” (). These narratives were not mutually exclusive; some interviewees showed evidence of more than one narrative in their interviews. However, interviewees tended to align themselves more strongly with one narrative over others. Additionally, narratives were heterogeneous within stakeholder groups; there was no significant evidence that suggested narratives were exclusive to either raptor monitors or gamekeepers as a group.

Figure 1. Summary of the three narratives (cooperation, despondence and resistance) and their construction. Larger boxes illustrate the main arguments under each theme (small boxes on left). Arrows represent the way in which these arguments collectively justified a particular action.

Quotes are used throughout the text to illustrate certain arguments. The numbers that follow each quote (1–20) refer to the interviewee’s unique reference number. “RM” or “GK” are used to denote raptor monitors and gamekeepers, respectively.

The Resistance Narrative (the “Fight” Response)

The resistance narrative conveyed a particularly antagonistic message, built from stories and experiences that implied there was no other choice but to act combatively, as a form of defence and protection against an implied enemy – in other words, to fight. As such, this narrative depicted the interviewee – and, often, their respective interest group – as being on the back foot, cornered, or pressured in some way. For example: “When you’re being constantly attacked, you have two options…either shrink into a hole and die, or come out fighting. I’ve chosen to come out fighting” (5GK). Others described a “harsh world” where you must “strike fire with fire…else you’ll get nowhere” (14RM).

This narrative deflected blame from the actor themselves onto others, and painted a story of injustice. Interviewees emphasized that their position was the “correct” one, and that others were in the wrong: “…they’re always demanding…demanding…we’re only demanding they stop persecuting birds of prey. But they’re still wanting all these other things” (4RM). Similarly, there was a sense of disregard for these “other” groups, who were deemed as having inferior knowledge and skills in comparison to the higher credibility and merit of the group the interviewee identified with. For example, one interviewee (2RM) described the entire shooting sector as “based on personal, individual experience or snippets of information, rather than robust, scientifically approved methods”. Others claimed that some interest groups were untrustworthy, or cheating the system in order to gain status: “…we outperform about 70% of their reserves…we put in all the time and effort…but do you hear that? No. Don’t take public money, say you’re going to protect it, and then not do the job.” (5GK). This led to the interpretation that “other” groups had unwarranted power and capacity, for example interviewee 20GK stated that “[Conservation bodies] have had undue influence for too long.” From this perspective, it made sense to defend your own territory: “They [Scottish government] want to allow a licence for them [landowners] to kill things like ravens…It’s up to people like myself to disprove these things.” (9RM).

In essence, the resistance narrative depicted a strong sense of pride in the interviewees’ own work, interests, and actions, as well as those of their interest group, which were deemed to be superior. Other groups were seen to be asserting their influence at the expense of other interests, wildlife and the environment – and even duping the wider public with falsehoods. Linked to this was the fear that these groups would not be held adequately accountable, and there was low levels of trust and respect for decision makers and those in positions of authority. Conflict management interventions, such as multi-stakeholder forums and participatory processes, were therefore seen as arenas to fight, compete, and eventually, win – with past experiences of failed management efforts used as justification for why this had to be the case: “the constant attempts by both sides to come together…only to be broken again…has completely undermined any goodwill that has begun to be built up” (8RM).

The Despondence Narrative (The “Flight” Response)

Where the resistance narrative was characterized by action, the despondence narrative represented inaction. Interviewees expressed wanting to disengage and deliberately avoid any situation where they may come into conflict with others – be that in a multi-stakeholder forum or on social media. Dominant motifs were of hopelessness, disempowerment, rejection, and unfairness, which served as an explanation as to why the individual had chosen to withdraw from the conflict and any effort to manage it. “What is the point?” (3GK) was a recurring statement, as was the idea that the outcome of any efforts – especially collaborative efforts – would be “inevitable. It’s just having [meetings] for having them’s [sic] sake” (10RM).

The sense of disempowerment and despondence interviewees described appeared to be closely linked with accountability, however the way in which they were linked differed between GKs and RMs. For RMs, the desire to disengage stemmed from a “loss of hope” (14RM) that the shooting industry would ever be held accountable for its actions: “I just can’t see them ever being brought to justice. And it’s hard to persevere, you know, when you’re fighting a losing battle” (10RM). GKs, on the other hand, felt they were wrongly blamed for the actions of their peers who had committed crimes, but were unable to prevent themselves from being labeled as perpetrators by association: “It’s terrible for the industry… [the public] think that [illegal killing] is the norm. But that’s what these high-profile individuals do, they tar everybody with that” (16GK). Such interviewees distanced themselves from other members of their community that they saw as “getting more and more intensive, moving further away from traditional methods” (3GK). Some mentioned “factoring agencies” (7GK) – agencies hired specifically to increase the productivity of a shooting estate – and “absentee landlords” (16GK) as major contributing factors to bad behavior, but did not want to speak of these issues within their community or on a more public stage: “I don’t like public speaking, and I don’t like standing up in front of audiences and being a mouthpiece…it’s not in our [gamekeepers’] nature to stand up and speak out” (16GK). RMs also described disapproving of peers with more “extreme” stances, but felt they were “drowned out by those who shout the loudest” (19RM) and so chose not to speak of this publicly.

The despondence narrative was also characterized by stories that portrayed little support from, or confidence in, the bodies that claimed to represent them on a more national stage. For example, 1RM recalled a negative experience with a conservation group who had promised protection during an altercation with the local estate: “…they washed their hands of me. I got – they put me in the firing line, and when the flak came over, they just ran for the hills”. Some interviewees described shame, or even embarrassment at bodies chosen to represent shooting interests: “…we don’t have anyone that I see as a figure fighting our side. Some of the guys I see…who are real mouthpieces, and they think they’re talking for the whole game shooting industry but…I’ve heard comments that just make me cringe” (16GK)., Interviewees therefore perceived themselves as being alone (“you batter, and batter, and batter your head against a brick wall, until you either have a mental breakdown, or you give up…” 19RM) and unable to voice their concerns (“I think they [gamekeepers] are frightened that if they went and spoke to somebody, they’d be accused of talking out of turn” 3GK). Furthermore, there was a distinct lack of trust in the government to act: “there’s signals, and there’s signs, but they’re not strong enough in any way” (14RM). Or, that decisions made by government would have repercussions for the interviewee or their livelihood “I passionately know that what [Scottish government] are about to do is crazy, because it will be used against us.” (13GK).

Collectively, these elements were used to construct a narrative which represented conflict management as a fruitless endeavor, and the interviewee as helpless and/or lacking in the agency and capacity to enact change. This narrative allowed the individual to justify avoiding, and in some cases running away from, the situation at hand as a form of protection.

The Cooperation Narrative (The “Ready and Willing” Response)

The cooperation narrative demonstrated a more tolerant – and in some cases, positive – reaction to the conflict, where interviewees expressed a readiness and willingness to engage constructively in conflict management and make progress. The view was that conflicts over wildlife and land management were inevitable, but not necessarily a wholly negative process – rather “healthy… natural… normal” (12RM). In contrast to the other two narratives, the cooperation narrative detailed good, healthy relationships and positive interactions, not just between them and their peers, but also with other stakeholders at both a local and national level. High levels of trust and respect were apparent. For example, 15GK described having a “good relationship with everybody, they respect what we do”, whereas 11RM talked of knowing “a sort of level we can work at, because we can’t do what we need to do without their [gamekeeper’s] cooperation”.

While resistance and despondence narratives portrayed feeling let down by their representative bodies, the cooperation narrative contradicted this sentiment: they felt well represented by the same organizations. They drew on remembered experiences and specific events that evidenced this: “I really liked how [a national conservation organisation] put things across at the last consultation I went to. I think they’re actually pretty balanced, on the whole, and I trust them to do right” (12RM); “I know if I need advice on certain aspects…I know they’re [a shooting organisation] are there. They’re good at it.” (15GK). This also extended to government bodies and decision makers. 3GK spoke of a constructive meeting with a member of Scottish parliament (MSP), describing that they, and their colleagues, then felt understood and supported: “she came to us, she saw the issue, she understood the issue”. Associated with positive views of the government and decision-makers was also a level of empathy and respect for those needing to “keep everybody happy” (2RM).

The cooperation narrative identified power as evenly distributed and depicted stakeholders as having almost equal capacity for change: “…we can’t all dictate the terms, there’s got to be compromise. There’s room for everybody to make change” (11RM). Responsibility for the conflict, and its associated issues, was also seen to be shared (“everybody is to blame in some way. We need to look at our own stances” (2RM)) and therefore everyone should be held accountable for their own actions: “We have to respond to this pressure, and be seen to respond to it…I don’t think we’re going to be able to carry on like this. And nor should we – it’s not good for people” (15GK).

Stories emphasized collaboration and cooperation between stakeholders as being of utmost importance (“…move towards the middle ground” (11RM)) and suggested the interviewees’ willingness to be part of that process: “I’d be all for that, I’d love to be involved in [a process] that tries to get some good dialogue between the extreme organisations” (7GK). However, this came with a pre-requisite: that the “right people, in the right places” (1RM) would need to come together, which, according to interviewees, was still to happen. In essence, the cooperation narrative constructed the conflict as everybody’s problem, but one that was a positive opportunity for change – given the right ingredients.

Discussion

Our findings carry important implications for the management of conservation conflicts on a global scale, where current trends lean heavily toward multi-stakeholder processes (Zimmermann, Albers, and Kenter Citation2021). At present, the status quo is still to view and manage conservation conflicts as the inevitable outcome of competing interests (Redpath, Bhatia, et al. Citation2015). Under this framing, it makes sense to group stakeholders based on their respective interests or professions; representatives of these interest groups are then brought together to enter dialogue and foster shared solutions and decisions that, ideally, appease both sides (Kusters et al. Citation2018). However, the results of this study – mirrored by those from the wider literature – suggest several considerations that need to be taken into account before entering into multi-stakeholder processes as a form of management.

Who Speaks for Me? Representation and Exclusion as Drivers of Conflict Responses

The first regards adequate representation and inclusion. Grouping stakeholders by interest alone assumes homogeneity within the perspectives, values, motivations and decision-making of individuals with the same interest and/or profession, which risks representation bias (De Vente et al. Citation2016; López-Bao, Chapron, and Treves Citation2017). Our results found that group affiliation was not a reliable proxy for individual perspectives and actions in a conflict situation; rather, there was substantial variation within both interest groups. The three narratives identified represented very different social realities: resistance painted a picture of politics and strategy; despondence a fractured situation beyond repair. These constructed realities provided justification for certain actions, or responses, to the conflict: to “fight or flight”, respectively. However, our analysis also uncovered a third, more positive outlook – the cooperation narrative (“ready and willing”). Here, the conflict was seen as a potential for social change, more akin to a conflict transformation perspective (Skrimizea et al. Citation2020). These findings are mirrored by other scholars who have examined similar conflicts pertaining to conservation or natural resource management and suggest substantial heterogeneity not just between, but within stakeholder “groups” and “communities” (Levine Citation2016; Voyer et al. Citation2017).

If this nuance and complexity in perspectives does not translate to various levels of governance, then important voices can be marginalized or even completely lost from the debate – including those that are more willing to engage constructively (Voyer et al. Citation2017; Cieslik, Dewulf, and Buytaert Citation2020) or with a key role in how decisions are implemented on the ground (De Pourcq et al. Citation2019). Such skewed bias can then result in culturally or socially inappropriate management decisions, that do not adequately reflect the positions of the whole community (Levine Citation2016; Oduma-Aboh, Tella, and Ochoga Citation2019). This can evoke resistance in the form of counter or even radical views, as individuals fight to be acknowledged, and perpetuate existing tensions (Von Essen and Hansen Citation2015; Bergius, Benjaminsen, and Widgren Citation2018).

Representation – or indeed, a lack of it – was an integral component in individual decisions on whether, and how, to engage in conflict management. This suggests that there needs to be less focus on the outcome of conservation conflict mitigation in the first instance and more on the process itself, with emphasis on who is invited to the decision-making table and how. Ottolini, De Vries, and Pellis (Citation2021, 1) observe that in conflicts associated with wolf conflicts in Spain were exacerbated by the act of managing conflicts “at a distance” – where decisions regarding conflict management are made by actors operating at scales outside of the local context. The main caveat of this is a lack of meaningful and appropriate representation. Especially with problems of regional or country-wide scale, designing and implementing multiple local-level processes is resource and time intensive, and governments are often put under pressure to resolve such issues quickly and efficiently (Young et al. Citation2016a). Consequently, the institutions and actors involved in decision-making are often selected by governments or a higher-level authority, even when the governance mechanism is claimed to be “decentralised” (Taylor and Van Grieken Citation2015). This can result in a similar effect to what was observed in our case study: individuals feel misrepresented and/or lack trust in the bodies chosen to represent them at a national level. Non-governmental organizations and statutory bodies are increasingly fulfilling these roles and becoming powerful voices in environmental debates (Betshill and Corell Citation2008). Representatives can be found at national level, seated in forums and around the decision-making table, informing future management decisions (Nuesiri Citation2018). Furthermore, NGOs – particularly conservation NGOs – have an active role in the design, implementation, and leadership of community-level processes (Pooley et al. Citation2017; Aldashev and Vallino Citation2018). The role of such actors can be valuable and at times necessary to address large-scale issues, however there can be an issue of mis-match between these actors and local level, as we have seen from this study and others (e.g. Bonsu et al. Citation2019; Cox et al. Citation2020). NGOs may represent certain interests, but also have their own agendas to fulfill which influences their actions and discourses – for some, perpetuating the conflict is of interest in order to satisfy a political agenda (Hodgson et al. Citation2018). Thereby certain perspectives can become dominant and institutionalized, even if they do not adequately reflect the full variety of values and opinions present in a community (Turnhout et al. Citation2012; Matulis and Moyer Citation2017).

In practice accurately representing every viewpoint is unachievable, although diversity and representation can be improved through involving local communities and stakeholder groups in the design of conflict management strategies (De Vente et al. Citation2016). A collaborative conflict management process in the Amazon basin developed a “roadmap to increased collaboration” by designing the project in partnership with stakeholders over several months and building social learning into the process, advocating for constant dialogue and reflection to identify and address points of contention regarding the process and the people involved (Fisher et al. Citation2020). This process included collaborative stakeholder and conflict analysis, to identify with involved parties who should be involved, and what should be addressed. Further, studies investigating the failures and success of co-management processes of Indigenous people’s cultural heritage in Sweden and Finland advocate the agreement of local committees (or “champions”) through community-led consensus processes, as a way of validating and legitimizing key representatives (Grey and Kuokkanen Citation2020).

Going Beyond Disputes to Address Underlying Social and Political Inequities

Second, our findings emphasize the importance of understanding in-depth the underlying factors behind different social constructions of a conflict, and how this can influence stakeholder decision-making in a conflict scenario (Maldonado et al. Citation2019; Swan et al. Citation2020). It is often assumed that stakeholder willingness to engage with or accept a management intervention (or “solution”) is based on the distribution of tangible, material costs and benefits (Hodgson et al. Citation2020). Although these are important factors to consider (e.g. Hanley et al. Citation2010) our research supports others in demonstrating that social realities are much more complex, based on immaterial factors and the wider social-political context in which the conflict is embedded (Thondhlana, Cundill, and Kepe Citation2016; Nandigama Citation2020). The interviewees in our study based their decisions regarding whether and how to engage on past experiences, levels of trust, the distribution of power and agency, who would be held accountable, and whether they perceived themselves to be adequately represented by decision-makers. Our findings are supported by the work of many others, who have also found trust (Young et al. Citation2016b; Baynham‐Herd et al. Citation2020), power (Nantongo, Vatn, and Vedeld Citation2019) and historical relations and political dynamics (Mathevet et al. Citation2015) to be important in influencing how, and why, individuals engage and interact during conflicts.

These issues are more systemic; speaking to the governance and process of conflict management, and the socio-political environment in which it is situated, rather than its outcome. Conflict management can fail if attention is overly focused on resolution and important relationships, political dynamics and social and cultural barriers are overlooked (Bluwstein, Moyo, and Kicheleri Citation2016; Juerges et al. Citation2018). One method employed in the resolution of humanitarian conflicts, and suggested but not broadly tested in conservation, is that of conflict transformation, which aims to simultaneously resolve disputes over tangible aspects while addressing imbalances in power and social inequities (Rodríguez and Inturias Citation2018; Skrimizea et al. Citation2020). Although the exact process of transformation is difficult to ascertain due to its immense complexity, in general it looks to use conflict as a positive driver of social change (Madden and McQuinn Citation2014). The idea is not to suppress the conflict, but rather work constructively with it (Hallgren, Bergeå, and Westberg Citation2018) to cultivate an optimal social and political environment where such disputes can be dealt with more effectively (Hallgren, Bergeå, and Westberg Citation2018; Skrimizea et al. Citation2020).

Another potential way to address these issues is to integrate a diagnostic framework into conflict management, such as the conflict management tool suggested by Young et al. (Citation2016a) and the diagnostic framework presented by Harrison and Loring (Citation2020). Such frameworks provide a useful, iterative mode of enquiry that can be carried out with stakeholders to better understand the full story, and address core issues prior to any multi-stakeholder process so that they may be more targeted, efficient, and constructive.

Conclusions

Two main conclusions can be drawn from this study. First, common interest or profession is not a reliable proxy for stakeholder responses and experiences of conflict. Our analysis demonstrates significant nuance and variability within pre-defined stakeholder groups. Therefore categorizing stakeholders on these criteria alone does not ensure adequate representation of local actors and capture essential nuances within the debate and stakeholder perspectives. Second, core issues influencing the construction of narratives and social realities centered around governance and relationships, which reflects the wider literature on failures in conservation and natural resource management. Therefore our work contributes not just to the conservation conflict knowledge base, but also to conversations regarding a dilemma that characterizes most environmental problems: how do we successfully navigate a multi-stakeholder environment?

Our study suggests the need to recognize the social and political environment in which conservation is embedded as inherently complex, dynamic, and messy. Creating flexible processes that allow for nuanced discussion and expression of disagreement, rather than the polarized debate of strategy and contention that typically characterizes conservation conflicts, will allow for more diverse, constructive outcomes. In the context of the grouse shooting debate in Scotland, this means the development of more regional forums, designed and implemented in participation with local communities, to address the inherent issues derived from a lack of representation, agency, trust, and the unequal distribution of power between national and local voices. More generally, this requires acknowledging and addressing the systemic challenge of tackling global or national scale problems with sufficient local context. This underscores the need for long-term, adaptive management that supports constant dialogue and reflection on the process, rather than the outcome, of conflict management.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the participants of this study, who lent their voices and stories to this research, the organisations who were instrumental in the early stages of this research, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 “Raptor persecution” is a term used commonly in the UK to describe situations where raptors are killed or injured through trapping, poisoning, shooting or nest destruction.

References

- Ainsworth, G. B., S. M. Redpath, M. Wilson, C. Wernham, and J. C. Young. 2020. Integrating scientific and local knowledge to address conservation conflicts: Towards a practical framework based on lessons learned from a Scottish case study. Environmental Science & Policy 107:46–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.02.017.

- Aldashev, G., and E. Vallino. 2018. NGOs and participatory conservation in developing countries: Why are there inefficiencies? Department of Economics and Statistics Working Paper, No. 18/2013, University of Torino, Italy.

- Allen, M. 2017. The SAGE Encylcopedia of communication research methods. Sage: London, UK.

- Baynham‐Herd, Z., N. Bunnefeld, T. Molony, S. Redpath, and A. Keane. 2020. Intervener trustworthiness predicts cooperation with conservation interventions in an elephant conflict public goods game. People and Nature 2 (4):1075–84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10134.

- Benjaminsen, T. A., and H. Svarstad. 2010. The death of an elephant: Conservation discourses versus practices in Africa. Forum for Development Studies 37 (3):385–408. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2010.516406.

- Bennett, N. J. 2019. In political seas: Engaging with political ecology in the ocean and coastal environment. Coastal Management 47 (1):67–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2019.1540905.

- Berg, B. L. 2004. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 5th ed. Boston, U.S.: Pearson Education Inc.

- Bergius, M., T. A. Benjaminsen, and M. Widgren. 2018. Green economy, Scandinavian investments and agricultural modernization in Tanzania. The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (4):825–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1260554.

- Betshill, M. M., and E. Corell. 2008. NGO diplomacy: The influence of non-governmental organizations in international environmental negotiations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bixler, R. P. 2013. The political ecology of local environmental narratives: Power, knowledge, and mountain caribou conservation. Journal of Political Ecology 20 (1):273–85. doi: https://doi.org/10.2458/v20i1.21749.

- Bluwstein, J., F. Moyo, and R. P. Kicheleri. 2016. Austere conservation: Understanding conflicts over resource governance in Tanzanian wildlife management areas. Conservation and Society 14 (3):218–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.191156.

- Bonsu, N. O., B. J. McMahon, S. Meijer, J. C. Young, A. Keane, and A. N. Dhubhain. 2019. Conservation conflict: Managing forestry versus hen harrier species under Europe's Birds Directive. Journal of Environmental Management 252:109676. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109676.

- Bruner, J. 1993. Visual art as narrative discourse: The Ekphrastic dimension of Carmen Laforet's nada. Anales de la Literatura Española Contemporánea 18 (2):247–60.

- Bryman, A. 2004. Qualitative research on leadership: A critical but appreciative review. The Leadership Quarterly 15 (6):729–69. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.007.

- Butler, J., J. Young, I. McMyn, B. Leyshon, I. Graham, I. Walker, J. Baxter, J. Dodd, and C. Warburton. 2015. Evaluating adaptive co-management as conservation conflict resolution: Learning from seals and salmon. Journal of Environmental Management 160:212–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.06.019.

- Cieslik, K., A. Dewulf, and W. Buytaert. 2020. Project narratives: Investigating participatory conservation in the Peruvian Andes. Development and Change 51 (4):1067–97. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12592.

- Cox, T. R., J. R. Butler, A. D. Webber, and J. C. Young. 2020. The ebb and flow of adaptive co-management: A longitudinal evaluation of a conservation conflict. Environmental Science & Policy 114:453–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.09.017.

- Cusack, J. J., T. Bradfer‐Lawrence, Z. Baynham‐Herd, S. Castelló y Tickell, I. Duporge, H. Hegre, L. Moreno Zárate, V. Naude, S. Nijhawan, J. Wilson, et al. 2021. Measuring the intensity of conflicts in conservation. Conservation Letters 14 (3):1–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12783.

- Czarniawska, B. 2004. Narratives in social science research. London, UK: Sage.

- De Pourcq, K., E. Thomas, M. Elias, and P. Van Damme. 2019. Exploring park–people conflicts in Colombia through a social lens. Environmental Conservation 46 (2):103–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892918000413.

- De Vente, J., M. S. Reed, L. C. Stringer, S. Valente, and J. Newig. 2016. How does the context and design of participatory decision making processes affect their outcomes? Evidence from sustainable land management in global drylands. Ecology and Society 21 (2):1-25. doi: https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08053-210224.

- Dinnie, E., A. Fischer, and S. Huband. 2015. Discursive claims to knowledge: The challenge of delivering public policy objectives through new environmental governance arrangements. Journal of Rural Studies 37:1–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.11.008.

- Elliot, J. 2005. Interpreting people's stories: Narrative approaches to the analysis of qualitative data. In Using narrative in social research, ed. J. Elliot, 36–59. London, England: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Fischer, A., and K. Marshall. 2010. Framing the landscape: Discourses of woodland restoration and moorland management in Scotland. Journal of Rural Studies 26 (2):185–93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2009.09.004.

- Fisher, J., H. Stutzman, M. Vedoveto, D. Delgado, R. Rivero, W. Quertehuari Dariquebe, L. Seclén Contreras, T. Souto, A. Harden, and S. Rhee. 2020. Collaborative governance and conflict management: Lessons learned and good practices from a case study in the Amazon Basin. Society & Natural Resources 33 (4):538–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2019.1620389.

- Grey, S., and R. Kuokkanen. 2020. Indigenous governance of cultural heritage: Searching for alternatives to co-management. International Journal of Heritage Studies 26 (10):919–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2019.1703202.

- Hallgren, L., H. Bergeå, and L. Westberg. 2018. Communication problems when participants disagree (or avoid disagreeing) in dialogues in Swedish Natural Resource Management—challenges to agonism in practice. Frontiers in Communication 3:56. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2018.00056.

- Hanley, N., M. Czajkowski, R. Hanley-Nickolls, and S. Redpath. 2010. Economic values of species management options in human-wildlife conflicts Hen Harriers in Scotland. Ecological Economics 70 (1):107–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.08.009.

- Harrison, H. L., and P. A. Loring. 2020. Seeing beneath disputes: A transdisciplinary framework for diagnosing complex conservation conflicts. Biological Conservation 248:108670. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108670.

- Hodgson, I. D., S. M. Redpath, A. Fischer, and J. C. Young. 2018. Fighting talk: Organisational discourses of the conflict over raptors and grouse moor management in Scotland. Land Use Policy 77:332–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.05.042.

- Hodgson, I. D., S. Redpath, C. Sandstrom, and D. Biggs. 2020. The state of knowledge and practice on human-wildlife conflicts. Gland, Switzerland: The Luc Hoffman Institute.

- Hodgson, I. D. 2018. A conflict with wings: Understanding the narratives. relationships and hierarchies of conflicts over raptor conservation and grouse shooting in Scotland. PhD Thesis., University of Aberdeen.

- Ingram, M., H. Ingram, and R. Lejano. 2019. Environmental action in the anthropocene: The power of narrative-networks. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (5):492–503. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1113513.

- Jin, H. S., K. Hemminger, J. J. Fong, C. Sattler, S. Lee, C. Bieling, and H. J. König. 2021. Revealing stakeholders' motivation and influence in crane conservation in the Republic of Korea: Net‐map as a tool. Conservation Science and Practice 3 (3):e384. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.384.

- Juerges, N., A. Viedma, J. Leahy, and J. Newig. 2018. The role of trust in natural resource management conflicts: A forestry case study from Germany. Forest Science 64 (3):330–9.

- Kashwan, P. 2017. Inequality, democracy, and the environment: A cross-national analysis. Ecological Economics 131:139–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.08.018.

- Konrad, L., and A. Levine. 2021. Controversy over beach access restrictions at an urban coastal seal rookery: Exploring the drivers of conflict escalation and endurance at Children’s pool beach in La Jolla, CA. Marine Policy 132:104659. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104659.

- Kusters, K., L. Buck, M. de Graaf, P. Minang, C. van Oosten, and R. Zagt. 2018. Participatory planning, monitoring and evaluation of multi-stakeholder platforms in integrated landscape initiatives. Environmental Management 62 (1):170–81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0847-y.

- Levine, A. 2016. The development and unraveling of marine resource co-management in the Pemba Channel, Zanzibar: Institutions, governance, and the politics of scale. Regional Environmental Change 16 (5):1279–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0856-4.

- López-Bao, J. V., G. Chapron, and A. Treves. 2017. The Achilles heel of participatory conservation. Biological Conservation 212:139–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.06.007.

- Madden, F., and B. McQuinn. 2014. Conservation’s blind spot: The case for conflict transformation in wildlife conservation. Biological Conservation 178:97–106. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.07.015.

- Maldonado, J. H., R. Moreno-Sanchez, J. P. Henao-Henao, and A. Bruner. 2019. Does exclusion matter in conservation agreements? A case of mangrove users in the Ecuadorian coast using participatory choice experiments. World Development 123:104619. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104619.

- Mason, T. H., C. R. Pollard, D. Chimalakonda, A. M. Guerrero, C. Kerr‐Smith, S. A. Milheiras, M. Roberts, R. Ngafack, and N. Bunnefeld. 2018. Wicked conflict: Using wicked problem thinking for holistic management of conservation conflict. Conservation Letters 11 (6):e12460. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12460.

- Mathevet, R., N. L. Peluso, A. Couespel, and P. Robbins. 2015. Using historical political ecology to understand the present: Water, reeds, and biodiversity in the Camargue Biosphere Reserve, southern France. Ecology and Society 20 (4):1–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07787-200417.

- Matulis, B. S., and J. R. Moyer. 2017. Beyond inclusive conservation: The value of pluralism, the need for agonism, and the case for social instrumentalism. Conservation Letters 10 (3):279–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12281.

- Millar, G. 2018. Ethnographic peace research: The underappreciated benefits of long-term fieldwork. International Peacekeeping 25 (5):653–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2017.1421860.

- Mishler, E. G. 1991. Research interviewing: Context and narrative. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Nandigama, S. 2020. Performance of success and failure in grassroots conservation and development interventions: Gender dynamics in participatory forest management in India. Land Use Policy 97:103445. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.05.061.

- Nantongo, M., A. Vatn, and P. Vedeld. 2019. All that glitters is not gold; Power and participation in processes and structures of implementing REDD + in Kondoa, Tanzania. Forest Policy and Economics 100:44–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2018.10.011.

- Nuesiri, E. O. 2018. Strengths and limitations of conservation NGOs in meeting local needs. In The anthropology of conservation NGOs, eds., B. L. Larsen and D. Brockington, 203–25. Switzerland: Springer.

- Oduma-Aboh, S. O., J. D. B. Tella, and O. E. Ochoga. 2019. Rethinking Agila traditional methods of conflict resolution and the need to institutionalise indigenous methods of conflict resolution in Nigeria. Igwebuike 4 (3):104–117.

- Ottolini, I., J. De Vries, and A. Pellis. 2021. Living with conflicts over wolves. The case of Redes Natural Park. Society & Natural Resources 34 (1):82–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2020.1750746.

- Pooley, S., M. Barua, W. Beinart, A. Dickman, G. Holmes, J. Lorimer, A. J. Loveridge, D. W. Macdonald, G. Marvin, S. Redpath, et al. 2017. An interdisciplinary review of current and future approaches to improving human-predator relations. Conservation Biology 31 (3):513–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12859.

- Raik, D. B., A. L. Wilson, and D. J. Decker. 2008. Power in natural resources management: An application of theory. Society & Natural Resources 21 (8):729–39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920801905195.

- Rakotonarivo, O. S., I. L. Jones, A. Bell, A. B. Duthie, J. Cusack, J. Minderman, J. Hogan, I. Hodgson, and N. Bunnefeld. 2020. Experiemental evidence for conservation conflict interventions: the importance of financial payments, community trust and equity atttidues. People and Nature 3 (1):1–14.

- Redpath, S. M., S. Bhatia, and J. Young. 2015. Tilting at wildlife: Reconsidering human-wildlife conflict. Oryx 49 (2):222–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605314000799.

- Redpath, S. M., R. J. Gutiérrez, K. A. Wood, and J. C. Young. 2015. Conflicts in conservation: navigating towards solutions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Rodríguez, I., and M. L. Inturias. 2018. Conflict transformation in indigenous peoples’ territories: Doing environmental justice with a ‘decolonial turn. Development Studies Research 5 (1):90–105. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2018.1486220.

- Roe, E. 1994. Narrative policy analysis: Theory and practice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Romsdahl, R. J., A. Kirilenko, R. S. Wood, and A. Hultquist. 2017. Assessing national discourse and local governance framing of climate change for adaptation in the United Kingdom. Environmental Communication 11 (4):515–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2016.1275732.

- Rust, N. A., A. Abrams, D. W. S. Challender, G. Chapron, A. Ghoddousi, J. A. Glikman, C. H. Gowan, C. Hughes, A. Rastogi, A. Said, et al. 2017. Quantity does not always mean quality: The importance of qualitative social science in conservation research. Society & Natural Resources 30 (10):1304–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2017.1333661.

- Skrimizea, E., L. Lecuyer, N. Bunnefeld, J. R. Butler, T. Fickel, I. Hodgson, C. Holtkamp, M. Marzano, C. Parra, and L. Pereira. 2020. Sustainable agriculture: Recognizing the potential of conflict as a positive driver for transformative change. Advances in Ecological Research 63 :255–311.

- Soliku, O., and U. Schraml. 2020. From conflict to collaboration: The contribution of co-management in mitigating conflicts in Mole National Park, Ghana. Oryx 54 (4):483–93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285.

- Svarstad, H. 2002. Analysing conservation—development discourses: The story of a biopiracy narrative. Forum for Development Studies 29 (1):63–92. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2002.9666187.

- Swan, G. J., S. M. Redpath, S. L. Crowley, and R. A. McDonald. 2020. Understanding diverse approaches to predator management among gamekeepers in England. People and Nature 2 (2):495–508. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10091.

- Taylor, B., and M. Van Grieken. 2015. Local institutions and farmer participation in agri-environmental schemes. Journal of Rural Studies 37:10–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.11.011.

- Thirgood, S., and S. Redpath. 2008. Hen harriers and red grouse: Science, politics and human–wildlife conflict. Journal of Applied Ecology 45 (5):1550–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01519.x.

- Thondhlana, G., G. Cundill, and T. Kepe. 2016. Co-management, land rights, and conflicts around South Africa’s Silaka Nature Reserve. Society & Natural Resources 29 (4):403–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2015.1089609.

- Turnhout, E., B. Bloomfield, M. Hulme, J. Vogel, and B. Wynne. 2012. Conservation policy: Listen to the voices of experience. Nature 488 (7412):454–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/488454a.

- Von Essen, E., and H. P. Hansen. 2015. How stakeholder co-management reproduces conservation conflicts: Revealing rationality problems in Swedish wolf conservation. Conservation and Society 13 (4):332–44. doi: https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.179881.

- Von Essen, E.,. H. P. Hansen, H. N. Källström, M. N. Peterson, and T. R. Peterson. 2015. The radicalisation of rural resistance: How hunting counterpublics in the Nordic countries contribute to illegal hunting. Journal of Rural Studies 39:199–209. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.11.001.

- Von Essen, E.,. H. P. Hansen, H. Nordström Källström, M. N. Peterson, and T. R. Peterson. 2014. Deconstructing the poaching phenomenon: A review of typologies for understanding illegal hunting. British Journal of Criminology 54 (4):632–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu022.

- von Essen, E., and M. Allen. 2020. ‘Not the wolf itself’: Distinguishing hunters’ criticisms of wolves from procedures for making wolf management decisions. Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics 23 (1):97–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21550085.2020.1746009.

- Voyer, M., K. Barclay, A. McIlgorm, and N. Mazur. 2017. Connections or conflict? A social and economic analysis of the interconnections between the professional fishing industry, recreational fishing and marine tourism in coastal communities in NSW, Australia. Marine Policy 76:114–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.11.029.

- Young, J. C., K. Searle, A. Butler, P. Simmons, A. D. Watt, and A. Jordan. 2016b. The role of trust in the resolution of conservation conflicts. Biological Conservation 195:196–202. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.12.030.

- Young, J. C., D. B. Thompson, P. Moore, A. MacGugan, A. Watt, and S. M. Redpath. 2016a. A conflict management tool for conservation agencies. Journal of Applied Ecology 53 (3):705–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12612.

- Zimmermann, A., N. Albers, and J. O. Kenter. 2021. Deliberating our frames: How members of multi-stakeholder initiatives use shared frames to tackle within-frame conflicts over sustainability issues. Journal of Business Ethics 1:1-26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04789-1.

Appendix

Table A1. Six key themes, identified and defined by a thematic narrative analysis of 20 semi-structured interviews conducted with key stakeholders involved in raptor monitoring (RM) and grouse moor management (GK) in Scotland.

Table A2. Example guidelines for semi-structured interviews conducted with gamekeepers and raptor monitors from across Scotland.