Abstract

Purpose

To compare the effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) with transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) in early rectal neuroendocrine tumor (RNET) patients. This article will provide reliable evidence for surgeons in regards to clinical decision-making.

Methods

Systematic literature retrieval was performed in Pubmed, Embase and Cochrane database from 2013/4/30 to 2023/4/30. Methodology validation was performed by using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Data-analysis was conducted by using the Review manager version 5.3 software.

Results

A total of three retrospective studies were included in our meta-analysis. All eligible studies were considered to be high quality. By comparing baseline characteristics between TEM and ESD, patients in the TEM group seemed to be characterized by a larger tumor size and lower tumor level, even though no statistical significance was found. Clear statistical significance favoring TEM was identified in terms of R0 resection rate, procedure time and hospital stay. No statistical significance was found in terms of recurrence rate, adverse events rate and additional treatment rate.

Conclusions

Compared with ESD, TEM was a more effective treatment modality for early RNET patients; it was associated with a relatively higher R0 resection rate and a similar degree of safety. However, the relatively higher cost and complicated manipulation restricted the promotion of TEM. Surgeons should opt for TEM as a primary treatment in patients with a larger tumor size and deeper degree of tumorous infiltration if the financial condition and hospital facility permit.

INTRODUCTION

Rectal neuroendocrine tumor (RNET) is a rare cancer but has a low malignant potential; it has an approximate population morbidity of 1 per 100,000.Citation1,Citation2 The majority (80%∼90%) of RNET patients present with no symptoms and were found incidentally after screening via a colonoscopy.Citation2 Most RNETs were found to be <1 cm and presented an appearance of small yellowish submucosal nodules with normal mucosal coverings on the surface.Citation3 RNET accounts for about 1% incidence of all rectal tumors.Citation4 However, even though it is currently a rare condition, its incidence is increasing rapidly owing to the widespread use of colonoscopies, the increased awareness that clinicians have of RNET, as well as the consequence of an aging population in recent years.Citation5,Citation6 The incidence of lymphatic metastasis and distant metastasis in RNET patients is rare (3%) when lesions are <1 cm.Citation7 Owing to distinctive biological properties, the AJCC TNM staging and therapeutic strategy for RNET are not exactly in accordance with rectal cancer.Citation8 The guideline from European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society recommended local excision when the lesions are <1 cm or between 1 and 2 cm, and are characterized as a G1 or G2 histopathologic grade, and are without muscular and lymphatic infiltration.Citation7,Citation9 Moreover, when the lesions are >2 cm or between 1 and 2 cm, and are associated with muscular and lymphatic infiltration, or positive margins after the first coarse treatment, or G3 histopathologic grade, radical surgery becomes the recommend choice of management.Citation7,Citation9 The G1, G2 and G3 histopathologic grades were defined as a mitotic count <2 per 2 mm2 and/or Ki-67 ≤ 2%, a mitotic count 2–20 per 2 mm2 and/or Ki-67 3–20%, and a mitotic count >20 per 2 mm2 and/or Ki-67 > 20%, respectively.Citation9

Various modalities of local excision have emerged, including endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), modified EMR, endoscopic polypectomy, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM), endoscopic full thickness resection (eFTR) and transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS).Citation9 Among these options of local excision, ESD and TEM are two most effective modalities.Citation10 TEM was first introduced by Buess G as an alternative to total mesorectal excision (TME).Citation11 Nowadays, TEM has developed as one of the most popular therapeutic options for various rectal lesions, such as rectal polyps,Citation12 early stage rectal cancers,Citation13 RNET14 and rectal stromal tumors.Citation14 Compared with ESD, TEM is a more curative procedure allowing for full-thickness resection of the rectal wall even perirectal fat.Citation15 By contrast, ESD is a procedure allowing for resection of the submucosa. There are also some inherent disadvantages of TEM including a steeper learning curve and more expensive instruments.Citation16 Various studies have compared the effectiveness and safety between ESD and TEM in early rectal cancer patients.Citation13,Citation17 Due to the low morbidity of RNET, comparative studies between ESD and TEM were rare and only used a small sample size. For this reason, the most suitable procedure of local excision between ESD and TEM is still debatable in early RNET patients. Our meta-analysis was designed to help clinicians make a more suitable choice between ESD and TEM in early RNET patients.

The detailed procedures of ESD and TEM are as following: ESD is usually performed by intravenous anesthesia or local anesthesia. Patients are placed in a lateral position. First, the endoscopist marks the border with a Dual knife, after which, a solution is injected into the submucosa in order to lift the lesion. Then the lesion is incised along the pre-marked line. Lastly, electrocoagulation is used to stop the bleeding of the wound. In contrast, TEM is performed using general anesthesia or epidural anesthesia. Patients are firstly placed in a prone position. Then, the surgeon needs to insert the proctoscope and introduce CO2 gas into the rectum. At this point, the lesion is resected along the pre-marked line in a superficial to deep manner using an electrotome. The depth of resection includes the whole intestinal wall even the perirectal fat. At last, the wound should be sutured to stop any bleeding.Citation15

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search Strategy

Systematic literature retrieval was performed in Pubmed, Embase and Cochrane database from 2013/4/30 to 2023/4/30. The surgical instruments and surgeons procedural skills have developed rapidly. Studies 10 years ago might be outdated so were excluded from our search strategy. The key words used in our strategy were as follows: “endoscopic submucosal dissection”, “endoscopic dissection”, “transanal endoscopic microsurgery”, “local excision”, “transanal excision”, “transanal minimally invasive surgery” and “rectal neuroendocrine tumor”. Two authors performed literature retrieval by using the same search strategy independently. Irrelevant studies were firstly excluded by screening manuscript titles. Then, non-comparable studies, case reports, review studies, letters and videos were excluded. Subsequently, studies focusing on other procedures (EMR, eFTR and TAMIS) and studies that involved overlapping data were excluded by reviewing abstracts or full texts. If any disagreements occurred, the third author was responsible for making the final decision regarding its inclusion/exclusion. The references of included studies were manually checked for potential eligible studies. Our meta-analysis was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qingdao Municipal Hospital.

Inclusion Criteria

(1) Comparative studies between ESD and TEM; (2) Patients were adults; (3) Rectal lesions were proved to be neuroendocrine tumors according to the 2022 WHO Classification of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms;Citation18 (4) Distant metastasis was not found during preoperative routine assessments; (5) Tumor size was less than 2 cm.

Exclusion Criteria

(1) Non-comparative studies; (2) Rectal lesions were proved to be non-neuroendocrine tumors by histopathology; (3) Studies focusing on other procedures (EMR, eFTR and TAMIS); (4) Tumor size was larger than 2 cm; (5) Distant metastasis was identified prior to the surgery. (6) No concerning outcomes were provided; (7) Only the most recent study was included if several studies shared the same patient population.

Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed by two authors independently. The useful data extracted from the included studies was as follows: first author name, publication year, country, study style, sample size, age, patient sex, tumor level (the distance between tumorous lower margin and anal verge), tumor size, Grade of WHO, R0 resection, procedure time, adverse events, hospital stay, recurrence and additional treatment. If any disagreements occurred in data extraction, the third author was responsible to make the final decision.

Endpoints

The study endpoints were summarized as follows: effectiveness (R0 resection rate and recurrence rate), safety (rate and additional treatment rate) and cost-effectiveness (procedure time and hospital stay).

Methodology Validation

The included studies were evaluated by using Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Methodology validation was conducted according to three primary aspects: 1) representativeness of patients; 2) comparability of baseline data; and 3) objectiveness of results. Studies were evaluated as high quality if 5 or more stars were obtained, otherwise studies were evaluated as low quality.

Statistical Analysis

Data-analysis was conducted by using Review manager version 5.3 software (Revman; The Cochrane collaboration Oxford, United Kingdom). Cochrane Q statistic was used to assess the inter-studies heterogeneity. I2 was calculated to quantify the heterogeneity between studies. When I2 < 50, the heterogeneity between studies was deemed as low, and then the fixed effect mode was used. On the contrary, the random effect mode was used to pool the included studies. The effect sizes of continuous variables and dichotomous variables were indicated by standard mean difference (SMD) and an odds ratio (OR), respectively. The statistical significance was deemed as obvious when p value < 0.05. Publication bias and sensitivity analysis were not conducted in our meta-analysis because only three eligible studies were included. The detail equation of I2 statistic was as following: I2 =100% × (Q − df)/Q. Where df and Q were the degrees of freedom (number of included studies − 1) and Cochran’s heterogeneity statistic, respectively.

RESULTS

Literature Search and Characteristics of Eligible Studies

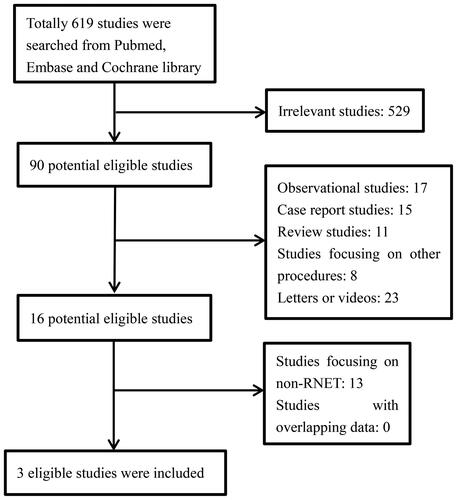

Our study was conducted following the rule of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist.Citation19 In total, three retrospective studies were included in our meta-analysis with 1 studyCitation15 from China and 2 studiesCitation10,Citation20 from Korea. The flow-chart pertaining to literature retrieval is shown in , No additional studies were found by checking the references of included studies, which indicated a comprehensive feature of our search strategy. A total of 436 RNET patients were involved in our study, 304 of whom received ESD and 132 patients received TEM. The mean age of RNET patients was approximately 50 years old and the proportion of males was 59%. All included studies were evaluated as high quality according to the NOS scale. The methodology validation for eligible studies is shown in .

TABLE 1. Methodology validation for eligible studies

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics between ESD and TEM

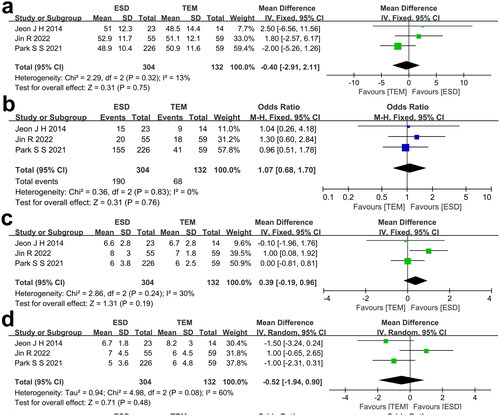

The baseline characteristics of RNET patients are shown in . The comparisons of baseline characteristics were performed, respectively, in our meta-analysis. All three studies reported the age of each treatment group. I2 = 13%, so the fixed effect model was used to calculate the effect size. The forest plot () showed no apparent statistical significance between ESD and TEM in relation to the age of the patients (p = 0.75). All three studies reported the percentage of males of each treatment group. I2 = 0%, so the fixed effect model was used to pool the effect size. The forest plot () revealed no statistical significance between ESD and TEM regarding the percentage of males (p = 0.76). All three studies reported the tumor level of each of the treatment groups. I2 = 30%, so the fixed effect model was used to calculate the effect size. The forest plot () showed that the tumor level of patients receiving TEM seemed to be lower than patients receiving ESD even though no statistical significance was found (p = 0.24). All three studies reported the tumor size of each treatment group. I2 = 60%, so the random effect model was used to calculate the effect size. The forest plot () showed that the tumor size of patients receiving TEM seemed to be larger than patients receiving ESD even though no statistical significance was found (p = 0.48).

FIGURE 2. a) Comparison of age between ESD group and TEM group. b) Comparison of male rate between ESD group and TEM group. c) Comparison of tumor level between ESD group and TEM group. d) Comparison of tumor size between ESD group and TEM group.

TABLE 2. Baseline characteristics of included RNET patients

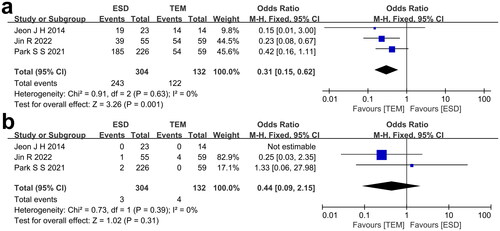

Comparison of Effectiveness between ESD and TEM

The extracted data of included studies regarding R0 resection rate and recurrence rate is shown in . All three studies reported the R0 resection rate of each of the treatment groups. I2 = 0%, so the fixed effect model was used to calculate the effect size. The forest plot () showed a higher R0 resection rate of patients receiving TEM compared with patients receiving ESD (p = 0.001). All three studies reported the recurrence rate of each treatment group. I2 = 0%, so the fixed effect model was used to pool the effect size. The forest plot () showed that patients receiving TEM seemed to suffer a higher recurrence rate than patients receiving ESD even though no statistical significance was found (p = 0.31).

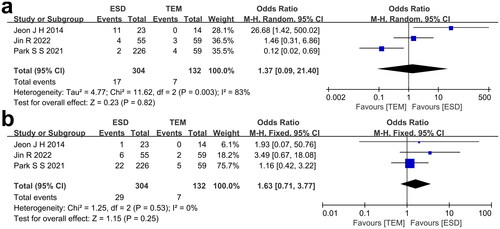

FIGURE 3. a) Comparison of R0 resection rate between ESD group and TEM group. b) Comparison of recurrence rate between ESD group and TEM group.

TABLE 3. Effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of included studies

Comparison of Safety between ESD and TEM

The extracted data of included studies regarding adverse events rate and additional treatment rate is shown in . All three studies reported the adverse events rate of each treatment group. I2 = 83%, so the random effect model was used to calculate the effect size. The forest plot () revealed no clear statistical significance between ESD and TEM regarding the adverse events rate (p = 0.82). All three studies reported the additional treatment rate of each treatment group. I2 = 0%, so the fixed effect model was used to calculate the effect size. The forest plot () showed that patients who received ESD seemed to suffer with a higher additional treatment rate in contrast to patients receiving TEM even though no statistical significance was found (p = 0.25).

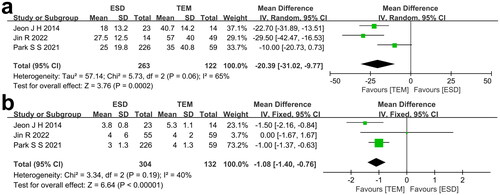

Comparison of Cost-Effectiveness between ESD and TEM

The extracted data of included studies regarding procedure time and hospital stay is shown in . All three studies reported the procedure time of each treatment group. I2 = 65%, so the random effect model was used to calculate the effect size. The forest plot () showed an obvious longer procedure time of patients receiving TEM than patients receiving ESD (p = 0.0002). All three studies reported the hospital stay of each treatment group. I2 = 40%, so the fixed effect model was used to calculate the effect size. The forest plot () portrays a longer hospital stay of patients who received TEM, in contrast to patients who received ESD (p < 0.00001).

Publication Bias and Sensitivity Analysis

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis were not conducted because only three eligible studies were included in our meta-analysis.

DISCUSSION

Significance of our Meta-Analysis

RNET is a rare rectal disease accounting for approximately 1% of various rectal tumors.Citation4 The scarcity of cases limits clinical trials related to RNET. For this reason, only few studies have compared the effectiveness of TEM and ESD in relation to RNET patients.Citation10,Citation15,Citation20 Previous studies have demonstrated similar long term outcomes when comparing local excision and radical surgery of RNET < 2 cm.Citation21,Citation22 For RNET patients with tumor sizes < 1 cm and tumor sizes 1–2 cm, without muscular or lymphatic infiltration, the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society recommends local excision.Citation7,Citation9 However, it is still controversial as to which local excision modality is the most appropriate. In view of this point, we conducted a meta-analysis and systematic review with a purpose of helping clinicians come to a more informed choice between ESD and TEM.

Preoperative Baseline Data

In our meta-analysis, the preoperative baseline data was pooled in order to present the comparability between ESD and TEM. Beside which, our meta-analysis also indicated the potential factors influencing surgeon preference of patient choice. Our results showed similar age and percentage of males between ESD and TEM, which reflects that age and sex are not the factors influencing patient choice. The mean age was approximate 50 years old and the overall percentage of males was 59% in our meta-analysis, which is consistent with the epidemiological investigation pertaining to previous studies.Citation23,Citation24 Patients receiving TEM showed trends of lower tumor level and larger tumor size even though the p value was >0.05. Tumor size is an important risk factor of local lymphatic metastasis and distant metastasis for RNET.Citation15 Compared with ESD, TEM could achieve a more radical resection by providing a full-thickness resection of tumors located 5–18 cm from the anal verge.Citation15,Citation25 Lower tumor levels can provide more satisfactory visualization for TEM.Citation11 For these reasons, surgeons should choose TEM as a primary treatment when patients were identified to have larger tumor sizes and lower tumor levels.

Effectiveness and Safety

Traditionally, effectiveness and safety are the most relevant parameters for a new technique. Compared with ESD, our results showed better effectiveness and a similar safety of TEM. The effectiveness included the outcomes of R0 resection rate and recurrence rate. When the tumor was resected with negative lateral and deep margins, we called it R0 resection. The non-R0 resection of RNET puts patients at risk of metastasis.Citation26 The overall R0 resection rates for ESD and TEM were 80% and 92%, respectively, which was consistent with several previous studies.Citation27–29 We also noticed that several studies focusing on early rectal adenocarcinoma demonstrated a similar R0 resection rate between TEM and ESD.Citation17,Citation30 The above distinct results might be explained by the different origination between adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumor. As we know, rectal adenocarcinoma originates from mucosa, whereas, RNET originates from submucosa. The higher R0 resection rate was attributed to the full-thickness resection of TEM. Our results showed a slight trend of higher recurrence rate for patients receiving TEM even though the p value was >0.05. The overall recurrence rates for ESD and TEM were 1% and 3%, respectively. Patients receiving TEM were usually effected by a more advanced stage of tumor, which might lead to a higher recurrence rate of TEM. In cases of local recurrence after TEM, the existence of fibrosis in the submucosal layer may represent a limitation for further local resection techniques. In view of this point, the initial choice of procedures is vital. The small sample size and short follow-up duration of eligible studies might influence the result of the recurrence rate. In view of this point, the larger sample size and longer follow-up time studies were necessary. As for safety, adverse events rate and additional treatment rate were pooled in our meta-analysis. Compared with ESD, our results indicated a similar adverse events rate and a slightly lower additional treatment rate for TEM. The adverse events mainly included perforation, bleeding, wound disruption and voiding difficulty. The overall adverse events rate was 5.5% in patients receiving TEM or ESD. Even if patients underwent full-thickness resection of TEM, the risk of perforation and bleeding could be minimized by meticulous suturing.Citation10,Citation20 Because no detailed data regarding the therapy on these adverse events was provided, as a result, we could not identify a distinction between minor and major adverse events in these three studies. An additional treatment was necessary when residual tumor cells were found on the resection margins. The additional treatment in ESD patients included low anterior resection (LAR) and TEM, while the additional treatment in TEM patients was all LAR in these included studies. The weak advantage of TEM in terms of additional treatment rate reflected the higher R0 resection rate of TEM from another perspective. To avoid additional treatment, the initial choice of procedures is vital.Citation26 According to the retrospective study by Lee SP et al., 95.9% of RNET patients could be suspected by macroscopic appearance under endoscopy.Citation31 If suspicious RNET was diagnosed, all invasive strategies should be suspended and endoscopic ultrasonography becomes necessary. If the muscularis layer becomes invaded, TEM should be chosen as the initial treatment.

Procedure Time and Hospital Stay

Longer procedure times and hospital stays were demonstrated in the TEM group by our meta-analysis. A longer procedure time was attributed to a steeper learning curve and a relative higher expertise of TEM.Citation32,Citation33 TEM usually needs to be performed in the operating room by using expensive specialized instruments, under the general or spinal anesthesia, as a contrast, ESD is performed in the endoscopy room under conscious sedation with analgesia. Nam MJ performed a comparison of costs between TEM and ESD, and their results demonstrated obvious higher median total hospital costs of TEM (1,686 USD vs. 1,214 USD).Citation34 Yu JX et al. performed a similar comparison and concluded that ESD was less expensive than TEM.Citation16 On this point, clinicians should consider the financial factor when choosing TEM as a primary treatment.

Limitations

There were several limitations in our meta-analysis. First, our meta-analysis only included three eligible retrospective studies. For this reason, the small sample size and inherent selection bias may influence our results. A large sample size and randomized controlled trial focusing on RNET patients is needed to compare the effectiveness and safety between TEM and ESD. Second, the baseline data between TEM and ESD were not absolutely comparable. Patients in the TEM group seemed to suffer from more advanced tumorous stage. However, this imbalance did not affect our results. Our results showed higher R0 resection rates in patients receiving TEM, even though more advanced tumorous stage was found in the TEM group. Third, only three studies were included in our studies, as a result, publication bias and sensitivity analysis were not performed. Fourth, the patients of our eligible studies were restricted to East Asia, which may influence the applicability of our results. Lastly, the short follow-up time of eligible studies might influence our results, such as the R0 resection rate and the recurrence rate.

CONCLUSION

Compared with ESD, TEM was a more effective treatment modality for early RNET patients, with an associated relative higher R0 resection rate and a similar degree of safety. However, the relatively higher cost and complicated manipulation restricted the promotion of TEM. Surgeons should choose TEM as a primary treatment in patients with a larger tumor size and deeper degree of tumorous infiltration if financial condition and hospital facility permit.

ETHICS STATEMENTS

Our study was approved by the Ethics of Hospital.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Hong Qi. Data curation: Fu-Gang Wang, Ying Jiang. Formal analysis: Fu-Gang Wang, Chao Liu. Writing-original draft: Fu-Gang Wang. Writing-review and editing: Hong Qi.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data available upon request.

REFERENCES

- Starzyńska T, Londzin-Olesik M, Bałdys-Waligórska A, et al. Colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms - management guidelines (recommended by the Polish Network of Neuroendocrine Tumours). Endokrynol Pol. 2017;68(2):1–8. doi:10.5603/ep.2017.0019.

- Basuroy R, Haji A, Ramage JK, Quaglia A, Srirajaskanthan R. Review article: the investigation and management of rectal neuroendocrine tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(4):332–345. doi:10.1111/apt.13697.

- Brand M, Reimer S, Reibetanz J, Flemming S, Kornmann M, Meining A. Endoscopic full thickness resection vs. transanal endoscopic microsurgery for local treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors-a retrospective analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(5):971–976. doi:10.1007/s00384-020-03800-x.

- Ramage JK, De Herder WW, Delle Fave G, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103(2):139–143. doi:10.1159/000443166.

- Zhao F, Huang L, Wang Z, Wei F, Xiao T, Liu Q. Epidemiological trends and novel prognostic evaluation approaches of patients with stage II-IV colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms: a population-based study with external validation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1061187. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1061187.

- Modica R, Liccardi A, Minotta R, et al. Therapeutic strategies for patients with neuroendocrine neoplasms: current perspectives. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2022;17(5):389–403. doi:10.1080/17446651.2022.2099840.

- Caplin M, Sundin A, Nillson O, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95(2):88–97. doi:10.1159/000335594.

- Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed New York, NY: Springer; 2016.

- Maione F, Chini A, Milone M, et al. Diagnosis and management of rectal Neuroendocrine Tumors (NETs). Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(5):771. doi:10.3390/diagnostics11050771.

- Park SS, Kim BC, Lee DE, et al. Comparison of endoscopic submucosal dissection and transanal endoscopic microsurgery for T1 rectal neuroendocrine tumors: a propensity score-matched study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(2):408–415 e402. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2021.02.012.

- Buess G, Mentges B, Manncke K, Starlinger M, Becker HD. Technique and results of transanal endoscopic microsurgery in early rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 1992;163(1):63–70. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(92)90254-o.

- Ortenzi M, Arezzo A, Ghiselli R, Allaix ME, Guerrieri M, Morino M. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery after the attempt of endoscopic removal of rectal polyps. Surg Endosc. 2022;36(10):7738–7746. doi:10.1007/s00464-022-09162-5.

- Kim M, Bareket R, Eleftheriadis NP, et al. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD) offers a sand more cost-effective alternative to Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery (TEM): an international collaborative study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(5):486–489. doi:10.1097/mcg.0000000000001708.

- Punnen S, Karimuddin AA, Raval MJ, Phang PT, Brown CJ. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) for rectal GI stromal tumor. Am J Surg. 2021;221(1):183–186. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.07.013.

- Jin R, Bai X, Xu T, Wu X, Wang Q, Li J. Comparison of the efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection and transanal endoscopic microsurgery in the treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors ≤ 2 cm. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1028275. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.1028275.

- Yu JX, Russell WA, Ching JH, et al. Cost effectiveness of endoscopic resection vs transanal resection of complex benign rectal polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(13):2740–2748.e2746. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.02.041.

- McCarty TR, Bazarbashi AN, Hathorn KE, Thompson CC, Aihara H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) versus transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) for treatment of rectal tumors: a comparative systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(4):1688–1695. doi:10.1007/s00464-019-06945-1.

- Rindi G, Mete O, Uccella S, et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2022;33(1):115–154. doi:10.1007/s12022-022-09708-2.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Jeon JH, Cheung DY, Lee SJ, et al. Endoscopic resection yields reliable outcomes for small rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Dig Endosc. 2014;26(4):556–563. doi:10.1111/den.12232.

- Zhao B, Hollandsworth HM, Lopez NE, et al. Local excision versus radical resection in patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumours: a propensity score match analysis. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90(12):E154–e162. doi:10.1111/ans.16221.

- Chen Q, Chen J, Huang Z, Zhao H, Cai J. Comparable survival benefit of local excision versus radical resection for 10- to 20-mm rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022;48(4):864–872. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2021.10.029.

- Cha JH, Jung DH, Kim JH, et al. Long-term outcomes according to additional treatments after endoscopic resection for rectal small neuroendocrine tumors. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):4911. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-40668-6.

- Zheng X, Wu M, Shi H, et al. Comparison between endoscopic mucosal resection with a cap and endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal neuroendocrine tumors. BMC Surg. 2022;22(1):248. doi:10.1186/s12893-022-01693-x.

- Guerrieri M, Baldarelli M, de Sanctis A, Campagnacci R, Rimini M, Lezoche E. Treatment of rectal adenomas by transanal endoscopic microsurgery: 15 years’ experience. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(2):445–449. doi:10.1007/s00464-009-0585-1.

- Dąbkowski K, Szczepkowski M, Kos-Kudła B, Starzynska T. Endoscopic management of rectal neuroendocrine tumours. How to avoid a mistake and what to do when one is made? Endokrynol Pol. 2020;71(4):343–349. doi:10.5603/EP.a2020.0045.

- Shi WK, Hou R, Li YH, et al. Long-term outcomes of transanal endoscopic microsurgery for the treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. BMC Surg. 2022;22(1):43. doi:10.1186/s12893-022-01494-2.

- Sun P, Zheng T, Hu C, Gao T, Ding X. Comparison of endoscopic therapies for rectal neuroendocrine tumors: endoscopic submucosal dissection with myectomy versus endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(11):6374–6378. doi:10.1007/s00464-021-08622-8.

- Sun D, Ren Z, Xu E, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection in rectal neuroendocrine tumors based on resection margin status: a real-world study. Surg Endosc. 2023;37(4):2644–2652. doi:10.1007/s00464-022-09710-z.

- Wang S, Gao S, Yang W, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus local excision for early rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(1):1–9. doi:10.1007/s10151-015-1383-5.

- Lee SP, Sung IK, Kim JH, Lee SY, Park HS, Shim CS. The effect of preceding biopsy on complete endoscopic resection in rectal carcinoid tumor. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29(4):512–518. doi:10.3346/jkms.2014.29.4.512.

- Helewa RM, Rajaee AN, Raiche I, et al. The implementation of a transanal endoscopic microsurgery programme: initial experience with surgical performance. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(11):1057–1062. doi:10.1111/codi.13333.

- Maya A, Vorenberg A, Oviedo M, da Silva G, Wexner SD, Sands D. Learning curve for transanal endoscopic microsurgery: a single-center experience. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(5):1407–1412. doi:10.1007/s00464-013-3341-5.

- Nam MJ, Sohn DK, Hong CW, et al. Cost comparison between endoscopic submucosal dissection and transanal endoscopic microsurgery for the treatment of rectal tumors. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015;89(4):202–207. doi:10.4174/astr.2015.89.4.202.