Abstract

Background

Temporary stoma formation is common in Crohn’s disease (CD), while stoma reversal is associated with postoperative morbidity. This study aimed to evaluate the postoperative outcomes of split stoma reversal, SSR (i.e., exteriorization of proximal and distal ends of the stoma through a small common opening) and end stoma closure, ESC (i.e., the proximal stump externalized, and distal end localized abdominally.

Methods

Patients with CD who underwent stoma reversal surgeries between January 2017 and December 2021 were included. Demographic, clinical, and postoperative data were collected and analyzed to evaluate outcomes of reversal surgery.

Results

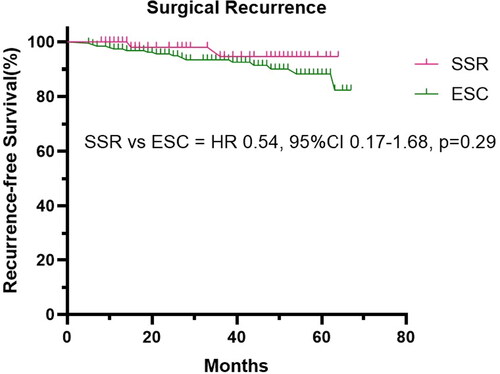

A total of 255 patients who underwent stoma reversal surgeries met the inclusion criteria. SSR was superior to ESC in terms of operative time (80.0 vs. 120.0, p = 0.0004), intraoperative blood loss volume (20.0 vs. 100.0, p = 0.0002), incision length (3.0 vs. 15.0, p < 0.0001), surgical wound classification (0 vs. 8.3%, p = 0.04), postoperative hospital stay (7.0 vs. 9.0, p = 0.0007), hospital expense (45.6 vs. 54.2, p = 0.0003), and postoperative complications (23.8% vs. 44.3%, p = 0.0040). Although patients in the ESC group experienced more surgical recurrence than those in the SSR group (8.3% vs. 3.2%) during the follow-up, the Kaplan-Meier curve analysis revealed no statistical difference (p = 0.29).

Conclusions

The split stoma can be recommended when stoma construction is indicated in patients with Crohn’s disease.

Introduction

Despite a decline in the rate of surgeries, 10–30% of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) still require surgery within 5 years after diagnosis [Citation1]. The two-staged surgery [Citation2] remains a pivotal aspect of the treatment algorithm for patients with CD. This approach typically entails the resection of the diseased intestine and the creation of a stoma during the initial stage, followed by stoma reversal in the subsequent phase. In certain cases, stomas are recommended to avoid the high risk of anastomotic leakage and consequent sepsis from a failed anastomosis [Citation3]. Such situations include elective (e.g., anemia, malnutrition, previous steroids use) or emergency (e.g., obstruction, perforation, abdominal abscess) settings [Citation4, Citation5].

A nationwide investigation [Citation6] revealed that ostomy procedures accounted for 19% of all procedures related to CD. Other clinical studies [Citation7, Citation8] reported similar data, with overall stoma rates ranging from 16% to 20%. A population-based surveillance in Canada [Citation9] demonstrated a reduction in overall surgical stoma formation rates in CD, with the rate declining by 5.2% annually. However, a cohort study in Sweden [Citation10] reported that despite the increasing use of anti-TNF, the cumulative incidence of stoma formation within 5 years of CD diagnosis had remained constant from 2003 to 2019.

Intestinal stomas occur in diverse configurations according to their location in the jejunum, ileum, or colon [Citation11, Citation12]. Stomas are classified into loop stoma and end (terminal) stoma based on the types of intestinal wall externalization [Citation13, Citation14]. In end (terminal) ostomy, the intestine is divided, and the proximal stump is externalized [Citation15], while the distal end is generally localized abdominally. Split stoma is a unique type of loop stoma [Citation16], where both the distal and proximal stoma intestines are brought out through a modest common incision. Ostomies can be temporary or permanent, depending on whether the intestinal continuity can be restored [Citation17]. Anastomosis is performed at an opportune moment in the future when the patient’s overall condition has improved. Other atypical stomas include the Mikulicz stoma [Citation15] and Kock continent ileostoma [Citation18].

Although stoma reversal surgery may result in less injury compared to the index operation, some studies [Citation19–22] have reported significant postoperative complication rates ranging from 11% to 33.3% after stoma reversal surgery. A systematic review [Citation21] demonstrated that the most common complications associated with ileostomy closure were surgical site infection and ileus. However, prior studies [Citation16, Citation23] indicated that patients with a split stoma had lower rates of early complications and anastomosis-related adverse events, as they did not require extensive secondary surgery.

This study aimed to compare the surgical information, short-term and long-term postoperative outcomes in patients with CD undergoing different types of stoma reversal surgeries after the index surgical resection.

Materials and methods

Patients selection

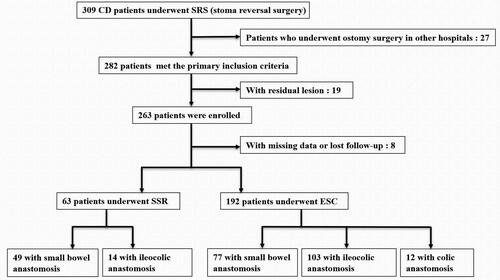

Patients with CD undergoing stoma reversal surgery from January 2017 to December 2021 were screened. The inclusion process of eligible patients is shown in . Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) CD diagnosed through clinical criteria and radiographic, endoscopic, and histopathological findings [Citation24], (2) stoma creation within our center due to obstructive or penetrating lesions associated with CD and (3) stoma reversal performed by the follow-up cutoff time. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) stoma creation for surgical complications; (2) residual lesions of CD, and (3) incomplete clinical data and lost follow-up. Patients were divided into two groups: split stoma reversal (SSR) with peristomal incision and end stoma closure (ESC) with middle incision. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Jinling Hospital.

Data collection

Demographic, perioperative, and follow-up data were extracted from a prospectively maintained inflammatory bowel disease(IBD) database. The data included gender, age, smoking history, Montreal classification of CD, preoperative medication history, appendectomy history, short bowel syndrome, body mass index, operative time, intraoperative blood loss volume, intraoperative blood transfusion, incision length, surgical wound classification [Citation25, Citation26], postoperative complications, postoperative hospital stay, hospital expense, perioperative blood test parameters including C-reactive protein(CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate(ESR), fecal calprotectin(FC), and serum levels of albumin(Alb). The follow-up duration after stoma reversal surgery was from the day of bowel continuity restoration to the date of surgical recurrence of CD or the follow-up on April 30, 2023. Data collection was recorded and verified by two independent reviewers.

Perioperative care

Before performing stoma reversal surgery on patients, a contrast radiograph via stoma or endoscopic intervention was executed to assess the integrity of the distal bowel. Routine endoscopic examination was also performed to evaluate the colon. Reversal surgeries were performed under general anesthesia, followed by general postoperative care.

Stoma closer

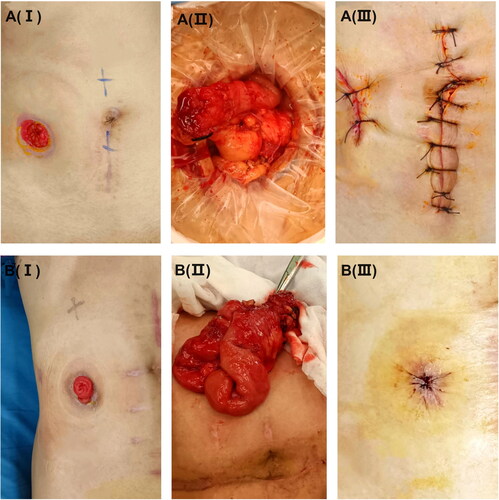

End stoma closure (): Midline incision was used. A peristomal oval skin incision was performed around the stoma to release the proximal end. The distal end of the bowel was visualized after dissection. A stapled functional end-to-end anastomosis was thus conducted. Closure of the abdominal fascial wall was performed with absorbable sutures, and the skin was closed with interrupted sutures.

Figure 2. Preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative pictures (I, II, and III) of stoma reversal surgery. (A) The end stoma closer (ESC). (B) The split stoma reversal (SSR).

Split stoma reversal (): (1) a circular or elliptical incision was made around the stoma; (2) a careful dissection was performed into the peritoneal cavity and the bowel segment was mobilized; (3) a stapled functional end-to-end anastomosis was created; (4) the intestine was returned to the peritoneal cavity; (5) fascial closure was carried out in an interrupted fashion; and (6) wound closure using a linear or a purse-string closure.

Outcomes and definition

The postoperative short-term outcomes included postoperative hospital stay, hospital expense, and postoperative complications. Postoperative complications were categorized as infectious or noninfectious and were classified according to the “Clavien-Dindo” classification [Citation27]. Surgical recurrence was defined as any surgery required due to recurrent CD which was confirmed by symptoms and endoscopic/imaging findings [Citation28, Citation29].

Statistical analysis

The normality of continuous variables was tested using Shapiro–Wilk Test. Continuous variables with approximately normally distribution were expressed as mean (standard deviation), and difference between the two groups was tested using the Student’s independent t-test. Continuous variables with skewed distribution were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR), and tested using Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were presented as percentages and tested using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test groups. All analyses were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS software version 22.0 (Armonk, NY).

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 255 patients with CD who underwent stoma reversal surgeries were divided into two groups: 192 in the SSR group and 63 in the ESC group. showed that the demographic characteristics of the two groups were similar in most terms (p > 0.05). The median duration of follow-up for patients in the SSR and ESC groups, respectively, was 36 (24.0–59.0) and 40 (23.0–55.0) months. Patients in the ESC group had a longer duration of disease (3 vs. 5, p = 0.02) and longer intervals between stoma formation and closure (6.2 vs. 7.9, p = 0.001) compared to those in the SSR group.

Table 1. Demographic and disease characteristics of 255 patients with CD who underwent stoma reversal surgery.

Surgical information

The surgical information of the 255 patients with CD who underwent stoma reversal surgery is presented in . Patients in the SSR group had shorter operative time (80.0 vs. 120.0, p = 0.0004), reduced intraoperative blood loss (20.0 vs. 100.0, p = 0.0002), shorter incision length (3.0 vs. 15.0, p < 0.0001), and a lower incidence of more severe surgical wound classification (0 vs. 8.3%, p = 0.04) compared to those in the ESC group. In the ESC group, three patients (1.6%) required intraoperative blood transfusion, while none in the SSR group required it (p > 0.05).

Table 2. Surgical information of 255 patients with CD who underwent stoma reversal surgery.

Postoperative outcomes

The primary outcomes of stoma reversal surgery in 255 patients with CD are presented in . The SSR was superior to ESC in terms of postoperative hospital stay (7.0 vs. 9.0, p = 0.0007), hospital expense (45.6 vs. 54.2, p = 0.0003), and postoperative complications (23.8% vs. 44.3%, p = 0.0040). Although patients in the ESC group experienced a higher rate of surgical recurrence compared to those in the SSR group (8.3% vs. 3.2%) during the follow-up, the Kaplan–Meier curve analysis indicated no statistical significance (p = 0.29) ().

Table 3. Postoperative outcomes of 255 patients with CD who underwent stoma reversal surgery.

Subgroup analysis

These patients were further divided into subgroups according to different anastomosis sites ().

In the small bowel anastomosis subgroups, 77 patients underwent ESC and 49 patients underwent SSR. In the ileocolic anastomosis subgroups, 103 patients underwent ESC, while only 14 patients underwent SSR. Additionally, 12 patients underwent ESC with colonic anastomosis, while no patients received SSR with colonic anastomosis. Supplemental Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of these subgroups, while the surgical information and postoperative outcomes appear in Supplemental Table 2. In the small intestinal anastomosis subgroups, the SSR was superior to ESC in terms of operative time (78.0 vs. 120.0, p = 0.0005), intraoperative blood loss volume (20.0 vs. 100.0, p = 0.0003), incision length (3.0 vs. 15.0, p = 0.0001), postoperative hospital stay (7.0 vs. 10.0, p = 0.0002), hospital expense (45.1 vs. 57.1, p = 0.0001), and postoperative complications (22.4% vs. 46.7%, p = 0.0060). In the ileocolic anastomosis subgroups, the SSR was superior to ESC in terms of intraoperative blood loss volume (40.0 vs. 100.0, p = 0.0001) and incision length (3.0 vs. 18.0, p = 0.0003). However, in both the small bowel and ileocolic anastomosis subgroups, the Kaplan–Meier curve analysis revealed no statistical difference in surgical recurrence between the ESC and SSR (Supplemental Figure 1).

Discussion

The increased risk of postoperative complications in patients with CD is a well-documented concern, as highlighted by previous studies [Citation30, Citation31]. The two-staged surgery has been shown to significantly reduce the incidence of postoperative complications [Citation32]. Several studies [Citation12, Citation33, Citation34] have indicated that over 75% of patients with CD can receive stoma reversal after ostomy. Our results indicated that SSR was associated with better postoperative outcomes compared to ESC.

The unique procedure of SSR likely contributes to the favorable outcomes. The SSR involves establishing a split stoma in the initial stage, which is performed in most regions of the small and large bowel [Citation14, Citation35]. Compared to the ESC, the SSR can be conducted outside the peritoneum, which eliminates the requirement for extensive secondary operation (). This approach results in smaller incisions, less intraoperative blood loss volume, and shorter operation time. In general, the extraperitoneal closure of the split stoma further enhances its safety profile. Main problem of split ileocolic stoma is the large volume of the colon, especially in emergencies, which may result in an increased number of stoma complications. In our study, patients in the SSR group had a higher incidence of ostomy complications than those in the ESC group (7.9% vs. 3.6%), as shown in Supplemental Table 3, but there was no statistical difference (p = 0.29).

Our results were consistent with previous reports [Citation36, Citation37] indicating higher rates of complications after open surgery in patients with CD. In Zhang’s report [Citation23], the incidence of early postoperative complications was 20.4% among patients with CD, which was comparable to our findings. In this study, we further analyzed postoperative outcomes of the two different types of stoma reversal surgery. The SSR was associated with a lower incidence of postoperative complications. This could be attributed to the fact that the ESC involved a more invasive operation via laparotomy, which increased the incidence of postoperative complications and resulted in longer hospital stay. Almost all patients with CD who underwent surgery would experience a recurrence, and ultimately 15% to 20% of cases required a second intervention [Citation38]. In our study, patients who underwent stoma reversal surgery were followed up, and there were no cases of postoperative mortality. There was a higher rate of surgical recurrence in the ESC group, but the Kaplan-Meier curve analysis revealed no statistical difference between the two groups.

Subgroup analyses also supported the benefits of SSR, particularly in small bowel anastomosis cases. Although the results of the ileocolic anastomosis subgroups were not as advantageous as those in small intestinal anastomosis subgroups, the SSR was still a better choice due to its cosmetic advantage and reduced intraoperative blood loss. Therefore, it is recommended to plan for a planned 2-ends (ileal-ileal and ileal-colic) split stoma after the initial surgical resection, if stoma formation is necessary for patients with CD.

However, our study has its limitations, including its retrospective nature, potential selection bias, and modest sample size. Large-scale, multicenter, prospective studies are needed to validate our conclusions.

Additionally, surgical recurrence can not completely represent disease recurrence in this study. To further explore the disease recurrence, colonoscopy monitoring results would be required. Given the above, the robustness and general applicability of the results may be limited.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings highlight the notable advantages associated with SSR in patients with CD, particularly in that involving small bowel anastomosis. Therefore, for patients at high risk of postoperative anastomotic leakage, it should be recommended to perform a planned split stoma during the primary surgical resection.

Authors’ contributions

Yi Li and Weiming Zhu conceived and designed the study, acquisition, and interpretation of data. Shixian Wang and Kangling Du were involved in the interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript; Ming Duan and Yihan Xu were involved in the analysis, acquisition, and interpretation of data; Zhen Guo and Jianfeng Gong were involved in the interpretation of data for the work, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

| Abbreviations | ||

| = | CD | |

| Crohn’s disease | = | SSR |

| split stoma reversal | = | ESC |

| end stoma closure | = | IBD |

| inflammatory bowel disease; IQR | = | interquartile range |

| B1 | = | nonstricturing nonpenetrating |

| B2 | = | stricturing |

| B3 | = | penetrating |

| BMI | = | body mass index |

| Anti-TNF | = | anti-tumor necrosis factor |

| Alb | = | albumin |

| CRP | = | C-reactive protein |

| ESR | = | erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| FC | = | fecal calprotectin. |

Supplemental Material

Download ()Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The database is available if properly requested and can be directly addressed to the corresponding author’s email address.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zhao M, Gönczi L, Lakatos PL, et al. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe in 2020. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(9):1–8. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab029.

- Bemelman WA, Warusavitarne J, Sampietro GM, et al. ECCO-ESCP consensus on surgery for Crohn’s disease . J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(1):1–16. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx061.

- Strong S, Steele SR, Boutrous M, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the surgical management of Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(11):1021–1036. doi:10.1097/DCR.0000000000000450.

- Adamina M, Bonovas S, Raine T, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: surgical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(2):155–168. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz187.

- Estrada DML, Benghi LM, Kotze PG. Practical insights into stomas in inflammatory bowel disease: what every healthcare provider needs to know. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021;37(4):320–327. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000737.

- Geltzeiler CB, Hart KD, Lu KC, et al. Trends in the surgical management of Crohn’s disease . J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(10):1862–1868. doi:10.1007/s11605-015-2911-3.

- Fumery M, Seksik P, Auzolle C, et al. Postoperative complications after ileocecal resection in Crohn’s disease: a prospective study from the REMIND group. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(2):337–345. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.541.

- Ma C, Almutairdi A, Tanyingoh D, et al. Reduction in surgical stoma rates in Crohn’s disease: a population-based time trend analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2019;21(11):1279–1287. doi:10.1111/codi.14731.

- Hossne RS, Sassaki LY, Baima JP, et al. Analysis of risk factors and postoperative complications in patients with Crohn’s disease . Arq Gastroenterol. 2018;55(3):252–257. doi:10.1590/S0004-2803.201800000-63.

- Everhov ÅH, Kalman TD, Söderling J, et al. Probability of stoma in incident patients with Crohn’s disease in Sweden 2003-2019: a population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(8):1160–1168. doi:10.1093/ibd/izab245.

- Pine J, Stevenson L. Ileostomy and colostomy. Surgery (Oxford). 2014;32(4):212–217. doi:10.1016/j.mpsur.2014.01.007.

- Post S, Herfarth CH, Schumacher H, et al. Experience with ileostomy and colostomy in Crohn’s disease. Brit J Surg. 1995;82(12):1629–1633. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800821213.

- Cataldo PA. Intestinal stomas: 200 years of digging. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(2):137–142. doi:10.1007/BF02237118.

- Lange R, Friedrich J, Erhard J, et al. The anastomotic stoma: a useful procedure in emergency bowel surgery. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1996;381(6):333–336. doi:10.1007/BF00191313.

- Ambe PC, Kurz NR, Nitschke C, et al. Intestinal ostomy: classification, indications, ostomy care and complication management. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(11):182.

- Myrelid P, Söderholm JD, Olaison G, et al. Split stoma in resectional surgery of high-risk patients with ileocolonic Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(2):188–193. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02578.x.

- Koriche D, Gower-Rousseau C, Chater C, et al. Post-operative recurrence of Crohn’s disease after definitive stoma: an underestimated risk. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(4):453–458. doi:10.1007/s00384-016-2707-2.

- Kock NG, Myrvold HE, Nilsson LO. Progress report on the continent ileostomy. World J Surg. 1980;4(2):143–148. doi:10.1007/BF02393560.

- Phang PT, Hain JM, Perez-Ramirez JJ, et al. Techniques and complications of ileostomy takedown. Am J Surg. 1999;177(6):463–466. doi:10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00091-4.

- Mansfield SD, Jensen C, Phair AS, et al. Complications of loop ileostomy closure: a retrospective cohort analysis of 123 patients. World J Surg. 2008;32(9):2101–2106. doi:10.1007/s00268-008-9669-7.

- Chow A, Tilney HS, Paraskeva P, et al. The morbidity surrounding reversal of defunctioning ileostomies: a systematic review of 48 studies including 6,107 cases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24(6):711–723. doi:10.1007/s00384-009-0660-z.

- Chu DI, Schlieve CR, Colibaseanu DT, et al. Surgical site infections (SSIs) after stoma reversal (SR): risk factors, implications, and protective strategies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(2):327–334. doi:10.1007/s11605-014-2649-3.

- Zhang Z, He X, Hu J, et al. Split stoma with delayed anastomosis may be preferred for 2-stage surgical resection in high-risk patients with Crohn’s disease. Surgery. 2022;171(6):1486–1493. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2021.10.044.

- Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management . J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(1):3–25. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw168.

- Garner JS. CDC guideline for prevention of surgical wound infections, 1985. Infect Control. 1986;7(3):193–200. doi:10.1017/S0195941700064080.

- Goodwin J, Womack P, Moore B, et al. Incision Classification Accuracy: Do Residents Know How to Classify Them?. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2017;18(8):874–878. doi:10.1089/sur.2017.088.

- Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience . Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):187–196. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2.

- Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Risk factors for surgery and recurrence in 907 patients with primary ileocaecal Crohn’s disease. J British Surg. 2000;87(12):1697–1701. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01589.x.

- Russo E, Cinci L, Di Gloria L, et al. Crohn’s disease recurrence updates: first surgery vs. surgical relapse patients display different profiles of ileal microbiota and systemic microbial-associated inflammatory factors. Front Immunol. 2022 Jul 29;13:886468. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.886468.

- Appau KA, Fazio VW, Shen B, et al. Use of infliximab within 3 months of ileocolonic resection is associated with adverse postoperative outcomes in Crohn’s patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(10):1738–1744. doi:10.1007/s11605-008-0646-0.

- Syed A, Cross R, Flasar M. Preoperative use of anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease patients is associated with increased infectious and surgical complications. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(5):S-37–S-38.): doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(11)60148-0.

- Zhou J, Li Y, Gong J, et al. No association between staging operation and the 5-year risk of reoperation in patients with Crohn’s disease. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):275. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-34867-w.

- Crowell KT, Messaris E. Risk factors and implications of anastomotic complications after surgery for Crohn’s disease. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7(10):237–242. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v7.i10.237.

- Morar PS, Hodgkinson JD, Thalayasingam S, et al. Determining predictors for intra-abdominal septic complications following ileocolonic resection for Crohn’s disease—considerations in pre-operative and peri-operative optimisation techniques to improve outcome. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9(6):483–491. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv051.

- Lange R, Fernandez ED. 25 years experience with the anastomotic stoma. Zentralbl Chir. 2006;131(4):304–308. doi:10.1055/s-2006-947278.

- Mege D, Michelassi F. Laparoscopy in Crohn disease: learning curve and current practice. Ann Surg. 2020;271(2):317–324. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002995.

- Dasari BV, McKay D, Gardiner K, Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for small bowel Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;1(1):CD006956. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006956.pub2.

- Valibouze C, Desreumaux P, Zerbib P. Post-surgical recurrence of Crohn’s disease: situational analysis and future prospects. J Visc Surg. 2021;158(5):401–410. doi:10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2021.03.012.