ABSTRACT

Lack of feedback about reports made to Adult Protective Services (APS) is an important barrier to elder mistreatment reporting. To better understand barriers and facilitators to APS-reporter communication, we conducted an environmental scan of state policies and practices. We gathered publicly available information from 52 states and territories on APS administrative structure, reporting, intake, investigation, and feedback processes; performed a secondary analysis of focus groups with Emergency Medical Services providers and APS staff; and interviewed 44 APS leaders in 24 states/territories. Results revealed variation in information-sharing with reporters. Qualitative analyses revealed three overarching themes related to whether, when, and how information is shared. Results were used to develop a model illustrating factors influencing APS decisions on sharing information. This model incorporates the type of reporter (professional or nonprofessional), their relationship with the APS client (brief or ongoing), and the potential risks and benefits of sharing information with the reporter.

Introduction

Elder mistreatment in the United States

Abuse, neglect, and exploitation of older adults are prevalent and underreported problems in the United States. In 2010, the population of older adults in the United States was 40 million (Population Projections Program, Citation2015) and this number is estimated to increase to 74 million by the year 2030 (Ortman et al., Citation2014). Of these, an estimated one in 10 community-residing older adults will experience some form of mistreatment which can include psychological, physical, and sexual abuse; neglect; and financial exploitation (Acierno et al., Citation2010), yet only a fraction of cases of elder mistreatment are reported. According to the World Health Organization, only one in five cases of elder mistreatment are reported. In contrast, a study in New York State found that as few as one in twenty-four cases of elder abuse were reported to the appropriate social or legal services (M. Lachs & Berman, Citation2011; World Health Organization, Citation2008).

Epidemiological studies demonstrate the morbidity and mortality risks associated with elder abuse (X. Q. Dong, Citation2015; M. S. Lachs et al., Citation1998) – including fractures and other trauma, depression, dehydration, malnutrition, and premature death – are three times higher for victims of elder mistreatment compared to non-victims (X. Dong, Citation2005). In addition to increases in morbidity and mortality, research shows that there are substantial economic consequences for victims. These include direct financial losses estimated to total $2.9 billion per year for victims of elder financial abuse (Metlife Mature Market Institute, Citation2011). Older adults who have experienced mistreatment visit the emergency room more often and have increased rates of hospital and skilled nursing facility admissions illustrating the high cost of elder mistreatment to the health care system (X. Dong & Simon, Citation2013a, Citation2013b, Citation2013c, Citation2015). More difficult to quantify, but undoubtedly equally important, is the unrealized potential of older adults who experience abuse, neglect, and exploitation to be the vibrant contributors to their families and communities they otherwise might be.

Adult protective services and reporting elder mistreatment

While specific policies and pathways to reporting and resolving elder abuse cases vary by state, all states/territories are dependent on mandated and/or non-mandated reporters to bring attention to these cases. State-administered Adult Protective Services (APS) are largely responsible for managing the government’s response to cases of suspected elder abuse. They do this, in part, through mandated reporting. The National Voluntary Consensus Guidelines for State Adult Protective Services Systems, issued by the Administration for Community Living, recommends states/territories require mandated reporting by members “of certain professions and industries who, because of the nature of their roles, are more likely to be aware of maltreatment” (Administration for Community Living, Citation2016). The professionals included in this list are the people older adults rely upon for protection, medical care, long-term services, in-home support, and behavioral health assistance. Not only are mandated reporters most likely to be aware of abuse, neglect, and exploitation, many of these professionals are also likely to have repeated or ongoing relationships with the people for whom they suspect abuse. For example, a February 2020 consensus report on social isolation, issued by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, acknowledged that health care providers may be the only point of community contact for older adults who are socially isolated, a known risk factor for abuse and neglect (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, Citation2020).

Despite mandated reporting, many professionals are hesitant to report concerns to APS. Existing research points to several barriers to reporting potential elder abuse among key professionals, including law enforcement personnel, staff at long-term care facilities, and health care providers (Cannell et al., Citation2016; Kaskie & Sandler, Citation2018; Kurkurina et al., Citation2018; Namboodri et al., Citation2018; Rosen, Elman, et al., Citation2017; Rosen, Lien, et al., Citation2017). For one, mandated reporters may not feel confident recognizing potential warning signs of abuse and/or they may not be aware of the appropriate process for reporting or for referrals to services. Additionally, misperceptions about how APS functions, cumbersome reporting procedures, and lack of feedback loops providing mandated reporters with follow-up information about the reports they have made contribute to reporter hesitancy. Studies found that providers’ attitudes toward their role in elder mistreatment detection and their subsequent reporting behaviors are impacted by the type of feedback they receive: receiving positive feedback about how their reporting changed a patient’s situation reinforces the importance of their role, and increases future reporting behaviors, while negative or lack of feedback can discourage providers and prevent them from reporting again (Namboodri et al., Citation2018; Rosen, Elman, et al., Citation2017). Importantly, however, concerns about the legality and ethics of sharing information about APS cases with reporters prevents effective and clear communication.

Study purpose

It is imperative that reporters can identify circumstances with increased likelihood of abuse and report in line with state mandates. The current approach in the United States relies upon the skilled eye and judgment of the reporter. However, reporters often do not receive information about what happens after they submit a report to APS, including whether their suspicions of abuse or neglect were substantiated, the types of interventions APS case workers recommend for short-term and long-term support, and whether their involvement with APS results in increased safety for those reported. Unfortunately, confusion about processes and structure and the absence of any indication of whether they are fulfilling their responsibility correctly leaves many reporters frustrated and discouraged. Reporters’ perspectives on barriers to reporting are well-documented in the literature but there is little research to date on the legal, ethical, and practical barriers and facilitators to improving communication between APS and reporters of elder mistreatment. The purpose of this study is to address this gap by assessing states’ and 3 territories’ current approaches and perspectives on APS-reporter communication at key points in the reporting and response pathway.

Methods

This study included an environmental scan with three components: 1) a systematic search of publicly available information, 2) semi-structured interviews with state APS leaders, and 3) secondary analysis of transcripts from focus groups previously conducted with Emergency Medical Services (EMS) providers and APS staff in Texas and Massachusetts.

Publicly available information

To review publicly available information, we developed a database of APS policy and practices for 50 states and two territories (the District of Columbia and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico). We collated data from several sources including individual APS program websites (N = 51; we were unable to locate a specific webpage for Puerto Rico), two APS Technical Assistance Resource Center reports, and state-specific laws for mandated reporting from the Elder Abuse Guide for Law Enforcement (Elder Abuse Guide for Law Enforcement, Citation2018). The database included 52 categories of information in four domains: 1) administrative structure (e.g., agency name, location, level of jurisdiction), 2) reporting and intake policy and practices (e.g., mandatory reporting type, reporting methods, eligibility for APS services), 3) investigation policy and practices (e.g., maximum response time, investigation completion time, services provided), and 4) feedback policy and practices (e.g., who receives feedback from APS, when feedback is provided, what information is provided). Findings related to the first three categories have been reported elsewhere (Urban et al., Citation2019); this paper focuses on the fourth category: feedback policy and practices.

Interviews with APS leaders

Following the review of publicly available information, we conducted interviews with APS agency leaders across the United States. We developed an interview protocol with guidance from an expert advisory board that included experts in elder mistreatment research, APS structure and function, and national elder justice policy (see Appendix A for interview protocol). Participants were purposively sampled and recruited by the project team and in collaboration with the National Adult Protective Services Association. The Human Protections Program determined this research to be exempt from expedited or full Institutional Review Board review. All participants provided written consent to participate in the study.

Interviews included an average of two participants per call and were approximately 45 minutes in length. Participants were asked to share their perspectives on APS policies and practices around reporting, investigation, and the types of feedback they provide to reporters; barriers to providing feedback; and possible ways to enhance the feedback process between APS and reporters. We conducted 32 interviews with 44 APS leaders in 23 states and one territory with varied administration structure (state or county) and intake approach (centralized, local, or both). Interviews were conducted virtually between November 2021 and March 2022. Each interview was audio recorded, transcribed, and cleaned of any identifiable information. Coding was completed in Dedoose Qualitative Analysis Software. An initial coding scheme was developed based on the interview guide and research questions. Three project staff applied the coding scheme to the same transcript to assess consistency and modify the coding scheme (final coding scheme available in Appendix B). The final coding scheme was then applied to each remaining transcript by a single coder and checked by a separate coder. Coding disagreements were discussed, and final codes applied. In line with Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) approach to thematic analysis, codes were analyzed and grouped into broader themes and sub-themes.

Secondary analysis of focus group transcripts

A secondary analysis of transcripts from focus groups previously conducted with EMS and APS staff was performed to better understand specific types of information reporters expect or would like to receive from APS. The focus groups were originally conducted as part of formative research completed to inform design of an online course for EMS providers on elder mistreatment identification, reporting, and response. Focus groups were conducted separately for EMS and APS. EMS providers were asked to share perspectives on barriers and facilitators to managing elder mistreatment including working with APS. APS staff were asked to describe strategies for engaging with EMS. Each 90-minute focus group was held in-person and audio recorded. We reviewed data from six focus groups with 23 EMS providers and 14 APS staff members in Texas and Massachusetts to pull themes related to the specific types of information that EMS mandated reporters would like to receive from APS.

Results

Review of publicly available information and interviews with APS leaders

The review of publicly available information provides evidence of how APS agencies differ in their approaches to providing feedback to reporters. Like other aspects of APS structure and practice, we found that the information states/territories provide on their websites about feedback policy and processes vary. Most states and territories (N = 30 of 52) do not provide information on their websites about whether, when, or how APS communicates with individual reporters after they submit a report. Websites for 18 states/territories explicitly state that their APS system will provide some feedback to individual reporters, though the type of information and process varies. In addition, 15 states/territories provide easily accessible and publicly available aggregate data on APS reports. In interviews with APS leaders from 24 states/territories, we learned that 19 APS agencies provide feedback to reporters in practice. Notably, eight of these agencies do not note this information on their websites. presents an overview of key findings from the review of publicly available information and interviews with APS agencies. We recognize that since we were not able to interview APS leaders in all 52 states and territories, we cannot definitively determine the extent to which each APS agency in the United States communicates with reporters in practice.

Table 1. Summary of findings from environmental scan.

These findings show that public sources, particularly state websites, do not consistently display information on whether, when, or how reporters can expect to receive feedback from APS, nor on the types of feedback APS provides. In compiling the data we collected from public sources with the data from interviews with APS leaders, however, we gained significant knowledge about the content of and processes for providing feedback. Feedback that is provided to individual reporters can be grouped into two broad categories: procedural feedback and substantive feedback:

Procedural feedback refers to information provided to reporters about the reporting process. APS may deliver this type of information via letter, phone call, or e-mail, and its purpose is often to notify the reporter that their report was received, is under review, or has been accepted or not accepted for investigation. Twenty of the 26 states and territories identified as providing some feedback to reporters provide exclusively procedural feedback.

Substantive feedback includes more descriptive information about why a case was accepted or not accepted for investigation, the outcome of the investigation, and/or the types of services implemented. Only six of the 26 states/territories identified as providing some feedback to reporters described providing substantive feedback.

Secondary analyses of EMS focus groups

The secondary analysis of focus groups conducted with EMS providers and APS staff helped to identify: 1) issues of concern and types of feedback that EMS providers would like to receive from APS and 2) key priorities for APS staff that may interfere with their ability to provide feedback about reports. Related to the first theme, EMS mandated reporters described the reporting experience to be “frustrating” and “a black hole.” They advocated for more feedback from APS to help them understand the outcomes of their reporting actions, such as if the report made was appropriate, and if their report had helped to improve care for the client. Contrary to a common perception among APS of what reporters want to know, these mandated reporters do not want to know case details; rather, they are seeking positive reinforcement about their reporting actions and want to know that “someone followed up and the [client] is now safe.”

The second theme focuses on APS staff perspectives. APS staff were clear that their first priority is always to protect the rights of older adults, which can hinder their ability to share information, even procedural feedback. APS staff appreciated reporters’ desire for more information but also noted that as mandated reporters, their willingness to report should not depend on the level of feedback they receive from APS. APS expressed interest in improving the way they work with mandated providers and noted the need for improved mutual understanding of APS’s role and the reporting process.

Triangulating the three sources of data obtained from a search of publicly available information, qualitative interviews with state APS leaders, and the secondary analysis revealed three overarching themes that affect whether, when, and how information is shared with reporters: 1) the risks and benefits APS perceives of providing information, 2) the reporter type and relationship to the client, and 3) progression along the report-response pathway.

Theme 1: perceived risks and benefits to APS of providing information

Findings from interviews show that APS leaders are aware that reporters want to receive feedback, and they recognize several benefits to providing this feedback. One benefit they described is the reduction in the number of calls and e-mails they receive from reporters requesting additional information. Furthermore, providing information back to reporters presents opportunities for APS to educate reporters on what to expect next, strengthen relationships with reporters, and help with improving the quality of future reports. One APS leader reflected on the reporter’s perspective:

Let’s say I’m new as a paraprofessional and I’m learning. This gives me a resource in my toolbox that says, “Okay, what is the vulnerability? And how could I help make a report stronger for the hotline?” If it gets screened out, and it tells me it’s due specifically to eligibility, I might be able to go back now and get some more information just on eligibility, and then call back in another report once I have that privileged information.

APS staff also described important risks to providing information back to reporters. Participants consistently voiced their obligation to prioritize the client’s privacy and to abide by confidentiality laws. In addition to privacy and confidentiality from a legal sense, participants noted an ethical obligation to the client, and expressed concern about breaking the client’s trust of APS. Participants stated a critical need to determine why a reporter wants more information; in some cases, a reporter may have malicious intent or complicated circumstances whereby providing information to the reporter will harm, rather than help, the client. As one participant said:

Our job is to help these vulnerable adults. And so if sharing that information out to the reporter is not beneficial to the vulnerable adult, I just don’t understand why we would do that. And I also think it’s very important that we consider the negative things that could happen over the positive, good feeling that it could give a reporter by making a report. Because, like I said, it can destroy families and relationships if information is shared out. And also, we have some very conniving people in the world…And they will call for the purpose of collecting information so that they can do something that’s not appropriate with it.

Finally, participants noted that limited resources can prevent them from being able to provide individual feedback to all reporters.

Theme 2: reporter type and relationship to the client

Another major theme from the interviews with APS leaders revealed that regardless of official policy, in practice, supervisors and caseworkers tend to practice discretion in whether, when, how, and with whom they communicate about individual cases. The analyses showed that the type of reporter (professional vs. nonprofessional) and quality of the relationship between the reporter and the client (brief involvement vs. ongoing involvement) are important factors in determining whether, when, and how information is shared. Reporters who are regularly involved in the care of the client, and for whom sharing information will aid the provision of services or benefit the client in formal or informal ways, are more likely to receive feedback on their report compared to reporters who are never or only occasionally involved in the care of the client or whose involvement in the case is unlikely to be of benefit to the client. Additionally, decisions about whether to provide feedback to a reporter with ongoing involvement with the client are likely to vary depending on whether the reporter is reporting in a professional or nonprofessional capacity. One participant described the complexity of the decision-making this way:

We get a fair number of referrals where it’s pretty clear that the referrer is using the system to try to harm the person they’re alleging the neglect for. So it’s tricky, and I’m very cautious about disclosing without really knowing who’s an ally. But I would probably defer to the judgment of the investigator. So once the case is open and the investigator gets to know the person, my feeling is if you think that – if having a conversation with the referrer would be helpful to the case, then I would be open to that.

In many states/territories, but not all, professional/nonprofessional status maps neatly to mandated/non-mandated reporter status. Reporters with a professional relationship to the client are more likely to be aware of and bound by privacy and confidentiality requirements similar to APS, and less likely to request information out of malicious intent compared to a nonprofessional reporter, such as a maligned neighbor or family member.

Theme 3: progression along the report-response pathway

The final theme that emerged from both the publicly available data and interview data relates to when in the report-to-response pathway information is provided from APS to reporters. Analyses indicated that the types of information shared from APS to reporters relate to three key points in the pathway: 1) intake, 2) investigation, and 3) case closure.

Intake begins when a report is submitted and ends when the report is either screened in or screened out for investigation. This is the point in the reporting process when feedback to reporters is most likely to occur. Several states/territories (N = 17 of 24 interviewed) reported communicating with reporters at intake. The information shared with reporters at intake is largely procedural and typically includes acknowledgment that the report was received, a report identification number, and/or contact information for the assigned caseworker. In two states/territories interviewed, APS provides reporters with more substantive information, often when the case is screened out. For example, APS may send a letter informing the reporter of the reason the case has been screened out, and where the case has been referred, if applicable. One participant described how providing feedback at the start of the process was largely advantageous:

I think it’s beneficial [to provide feedback] in the beginning because at least they know that we received it … So if they have questions, I think it’s like something like, oh, I have a confirmation number, you know, like they receive this … And I do think in the cases where it’s appropriate to speak to the reporting party— say it’s the daughter and the client is very confused—and so we are working with the reporting party in that instance because the client needs that type of assistance to [lessen] their confusion.

After a case is screened in, it moves to investigation. APS caseworkers assigned to the case may or may not be required to contact the reporter at this stage. However, many states/territories indicate that they do contact the reporter to validate the report, and receive additional information to assist the investigation. Communication with reporters at this point focuses on whether there is any updated information the reporter can provide. In some instances, reporters may be considered a collateral contact in the investigation. In these situations, they may have access to more information than reporters who are not considered collateral contacts. One agency has this process in place:

So during the investigation, if the box is checked “yes” or they say “yes, we would like to be contacted,” we will contact them. And typically, that’s one of the first things we do before the investigator even sees the vulnerable adult. Because what they’re doing is confirming those report allegations. Once they confirm the report allegations – because sometimes the hotline gets it a little backwards … so it’s kind of a caveat.

Few states/territories (N = 7) provide feedback to reporters at case closure. Those that do typically send a letter by mail to notify the reporter of the results of the investigation or case outcome (e.g., case was substantiated, unsubstantiated, or inconclusive). In some instances, the case closure letter may describe the services offered to the client, or recommendations for services that would be beneficial. This notification may or may not be required by statute. One participant noted:

I think it would be nice to be able to tell people the outcome … Without providing any details, it brings them closure on our end rather than not having the ability to know or know when it was closed or if it’s still ongoing, or that whole piece where we can’t disclose anything. It would be nice to at least let them know this is … we’re done with this piece…and bring closure to it.

At each point in the process (intake, investigation, case closure), there is variation within and among agencies in the methods used to communicate information (e.g., automated e-mail, letters by mail, or phone call), the type of information shared (e.g., procedural or substantive feedback), the person or staff member responsible for sharing the information (e.g., intake staff or local office staff, screener or investigator), the consistency of sharing the information with reporters (e.g., standardized or case-by-case basis), and whether or not they are required by their statute to share information with reporters.

Discussion

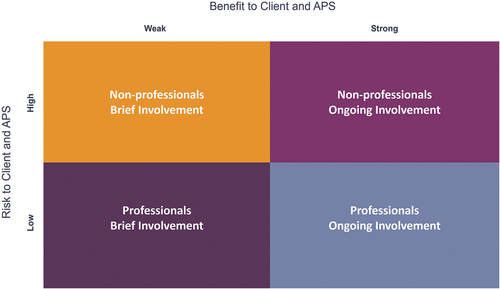

As described above, several factors influence whether, when and with whom APS share information. These factors include, of course, state laws and policy, but also a case-by-case evaluation by APS of whether it is safe, appropriate, and beneficial to provide information to the reporter. While there are nuances for each case, we found that these decisions tend to depend on the intersection of Themes 1 and 2. To illustrate how the themes intersect, we developed a decision-making model that maps the potential risks and burdens to clients and APS of APS sharing information with reporters against the potential benefits or rewards to the client and to APS of APS sharing information with reporters (see ). More individualized and substantive information tends to be shared when the perceived risks to the client and APS are low (e.g., risk of violating confidentiality laws and/or ethical obligations to the client) and perceived benefits are high (e.g., sharing information with the reporter could lead to improved outcomes for the client).

Non-professionals with brief involvement are the least likely to receive any feedback from APS (substantive or procedural). This group can include neighbors, friends, and the general public. They may be mandated or non-mandated reporters, depending on the state’s statute, but importantly, they are only briefly involved. The risks associated with providing feedback to this group of reporters are higher and the benefits are weaker compared to other groups of reporters.

The general population … may or may not have interaction with us again in the future.

–APS staff member

Professionals with brief involvement may receive procedural feedback but are unlikely to receive substantive feedback from APS. This group can include physicians, first responders, and other service providers, and are often mandated reporters. Though professionals, they are only briefly involved. Although the risks of sharing information with this group of reporters are lower compared to nonprofessionals with brief involvement, the direct benefits to the client are minimal. Importantly, however, this group of reporters plays a crucial role in elder mistreatment surveillance, and there are benefits to providing some level of feedback to reinforce this role.

… when it’s someone who doesn’t have that ongoing contact with the client … then they may not be contacted back. And that’s where a lot of the confusion and the assumptions that APS isn’t doing anything can occur.

–APS staff member

Nonprofessionals with ongoing involvement are likely to receive feedback from APS, particularly during the investigation phase. These reporters are often family and friends who are continuously involved in the care of the client. Because of their long-term involvement, there are likely some benefits to sharing information with them during the investigation. The benefits of providing feedback to this group of reporters are stronger compared to professionals and nonprofessionals who are only briefly involved. However, the associated risks are higher compared to involved professionals because nonprofessionals generally do not have to comply with confidentiality laws or regulations.

… if it’s a reporter who is really a family member that is involved in that care, we’re going to probably have ongoing communication with them… They’re going to know what’s going on.

–APS staff member

Professionals with ongoing involvement are the most likely to receive feedback from APS. This group can include primary care providers, social workers, and other service providers, and are often mandated reporters. Because of their profession and their ongoing relationship with client, the benefits of providing feedback to this group of reporters are stronger and the risks are lower compared to other groups of reporters.

… If the individual is a professional there is a specific code of ethics they have to follow … they understand the ins and outs of confidentiality and are bound by certain rules… In those circumstances, I really feel like it would be beneficial.

–APS staff member

The simple two-by-two table offers a decision-making model that can help APS agencies determine when they should or should not provide feedback to reporters. The model illustrates how the type of reporter and the quality of their relationship with the client align with risks and benefits to sharing information with reporters. Overall, APS is more likely to share substantive feedback with reporters when the perceived risk to client and APS is low and the perceived benefits are strong.

This model helps to illustrate the findings and will help states and territories interested in improving communication with reporters to locate the area in most need of improvement and focus efforts accordingly. Notably, while there are ostensibly fewer immediate benefits or rewards to the client and APS when the reporter’s relationship with the client is brief, these reporters play a critical role in elder mistreatment surveillance and should not be ignored as they have high potential to assist in early identification and prevention efforts. Procedural feedback may suffice for these reporters to encourage reporting and enhance their relationship with APS.

Limitations

This research is not without limitations. One limitation of this study is that we were only able to recruit leaders from 24 of 52 states/territories to participate in interviews as part of the environmental scan. This was due, in part, to competing demands during and in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, with its focus on qualitative data collection, the study may be susceptible to selection bias (e.g., those who were already interested in improving feedback between APS and reporters may have been more likely to agree to participate in the study) and social desirability biases. Additional research is needed to continue to advance communication between APS and reporters. For instance, this research did not address how types of feedback may vary related to the specific type or types of mistreatment allegations (e.g., physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, financial exploitation, and self-neglect). For next steps, it would be valuable for researchers to investigate how providing feedback might affect outcomes related to APS services, reporting counts, and client outcomes.

Conclusions

To provide robust contemporaneous support to older adults experiencing abuse, neglect, and/or exploitation, the professionals and citizens listed in state reporting statutes need to be deployed to recognize and report signs of abuse and neglect. While many mandated reporter laws include penalties for licensed professionals who fail to report, it is quite different to punish lack of reporting than to facilitate increased reporting. The quality of assistance to people who are abused improves when the professionals who are best positioned to identify mistreatment are sincerely invested in improving the person’s life and health. Feedback to mandated reporters may foster significant advancement in supporting those affected by mistreatment. Importantly, for professionals who provide care to adults at risk for abuse, filing a report should not be their sole responsibility. Many reporters have an ongoing relationship with the client and can help APS during and following an investigation to support the client’s ongoing safety. The elder justice movement, for lack of a more precise description, must move upstream. In the process of learning how reporters can provide direct assistance, people required to report can more easily understand risk factors as they emerge. Mandated reporters need to be considered essential abuse prevention and intervention partners. Establishing improved feedback and communication practices between APS and reporters is a critical next step in improving elder mistreatment response.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, KLH, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acierno, R., Hernandez, M. A., Amstadter, A. B., Resnick, H. S., Steve, K., Muzzy, W., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The national elder mistreatment study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 292–297. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cannell, M. B., Jetelina, K. K., Zavadsky, M., & Gonzalez, J. M. (2016). Towards the development of a screening tool to enhance the detection of elder abuse and neglect by emergency medical technicians (EMTs): A qualitative study. BMC Emergency Medicine, 16(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-016-0084-3

- Dong, X. (2005). Medical implications of elder abuse and neglect. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 21(2), 293–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2004.10.006

- Dong, X. Q. (2015). Elder abuse: Systematic review and implications for practice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(6), 1214–1238. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13454

- Dong, X., & Simon, M. A. (2013a). Association between elder abuse and use of ED: Findings from the Chicago health and aging project. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 31(4), 693–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2012.12.028

- Dong, X., & Simon, M. A. (2013b). Association between reported elder abuse and rates of admission to skilled nursing facilities: Findings from a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Gerontology, 59(5), 464–472. https://doi.org/10.1159/000351338

- Dong, X., & Simon, M. A. (2013c). Elder abuse as a risk factor for hospitalization in older persons. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(10), 911–917. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.238

- Dong, X., & Simon, M. A. (2015). Elder self-neglect is associated with an increased rate of 30-day hospital readmission. Findings from the Chicago Health and Aging Project Gerontology, 61(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1159/000360698

- Elder Abuse Guide for Law Enforcement. (2018). Department of justice elder justice initiative, national center on elder abuse, USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology. UC Irvine Health. Retrieved July 23, 2018, from http://eagle.trea.usc.edu

- Kaskie, B., & Sandler, L. A. (2018). The elder abuse pathway in East Central Iowa. University of Iowa. https://www.public-health.uiowa.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Elder-Abuse-Pathway-in-Iowa.pdf

- Kurkurina, E., Lange, B. C. L., Lama, S. D., Burk-Leaver, E., Yaffe, M. J., Monin, J. K., & Humphries, D. (2018). Detection of elder abuse: Exploring the potential use of the elder abuse Suspicion Index© by law enforcement in the field. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 30(2), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2017.1382413

- Lachs, M., & Berman, J. (2011). Under the radar: New York state elder abuse prevalence study. self-reported prevalence and documented case surveys final report.

- Lachs, M. S., Williams, C. S., O’Brien, S., Pillemer, K. A., & Charlson, M. E. (1998). The mortality of elder mistreatment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280(5), 428–432. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.5.428

- Living, A. F. C. (2016). Final national voluntary consensus guidelines for state adult protective services systems. https://www.acl.gov/sites/default/files/programs/2017-03/APS-Guidelines-Document-2017.pdf

- MetLife Mature Market Institute. (2011). The MetLife study of elder financial abuse. metlife.com/mmi/

- Namboodri, B. L., Rosen, T., Dayaa, J. A., Bischof, J. J., Ramadan, N., Patel, M. D., & Platts-Mills, T. F. (2018). Elder abuse identification in the prehospital setting: An examination of state emergency medical services protocols. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(5), 962–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15329

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25663

- Ortman, J. M., Velkoff, V. A., & Hogan, H. (2014). An aging nation: The older population in the United States (Report No. P25–1140). U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2014/demo/p25-1140.html

- Population Projections Program. (2015, March). Population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, Hispanic origin, and nativity: 1999 to 2100. http://ftp.census.gov/population/projections/nation/detail/np-d5-cd.txt

- Rosen, T., Elman, A., Mulcare, M., & Stern, M. (2017). Recognizing and managing elder abuse in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine, 49(5), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.12788/emed.2017.0028

- Rosen, T., Lien, C., Stern, M. E., Bloemen, E. M., Mysliwiec, R., McCarthy, T. J., & Flomenbaum, N. E. (2017). Emergency medical services perspectives on identifying and reporting victims of elder abuse, neglect, and self-neglect. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 53(4), 573–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.04.021

- Urban, K., Shusterman, G., Aurelien, G., Capehart, A., Gassoumis, Z., & Yuan, Y. (2019). APS policies, practices, and outcomes: A framework and analysis. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Submitted to the Administration for Community Living.

- World Health Organization. (2008). A global response to elder abuse and neglect: Building primary health care capacity to deal with the problem worldwide. Main report. http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/ELDER_DocAugust08.pdf

APPENDIX A.

INTERVIEW PROTOCOL

Interview Protocol for APS State Agency Leaders

Introduction & Consent (3 mins)

Thank you very much for taking the time to speak with us today. I am a [title] at EDC, an international non-profit research and development organization. The work I do focuses on aging and more specifically, elder mistreatment. Here at EDC, we have done work with APS and reporters in a number of states, and we have consistently been hearing about the need to improve communication between these two groups. For example, we hear from reporters that they would like to know more about what they can expect after they make a report to APS, whether they have reported appropriately, and whether the report they made is going to make a difference for the older adult. On the other hand, we hear from APS that it can be really hard to reach reporters to gather more information about suspected cases of mistreatment, which makes it more difficult for them to do their jobs. Essentially, there seems to be room to improve relationships and communication between APS and reporters.

In this study funded by the National Institute of Justice, we are conducting research to better understand states’ current policies and practices for communicating information back to reporters, perspectives on what works well and what does not work well, and recommendations for improving communication with reporters.

Before we begin, I need to remind you about your rights as a research participant. As you will have seen in the consent form you signed, this interview will take approximately 45 minutes. Your participation is voluntary; and your responses will be kept confidential. If you do not wish to participate, you may stop at any time. With your permission, we will be recording the interview. Recordings will be stored on password-protected computers and destroyed once the study is completed. If you have any questions regarding the line of questioning or regarding your rights as a research subject following the interview, you can contact us at the numbers and emails listed on the consent forms that you signed.

To begin, do I have your permission to record?

[IF YES: BEGIN RECORDING]