Abstract

Although the insufficient labor standards in the Arabian Gulf countries are hypervisible, laws have not improved to the benefit of workers. In this article, I examine art practices from Gulf-based artists that address this invisibility by replicating the conditions of the laborer in their artworks, a process I term “total replication.” In contrast to the art historian Schaffer’s argument that art must subvert hierarchies, I show how artworks that replicate work conditions also have the potential to create appreciatory visibilities. I argue that these artworks contain subversive messages in such a way that they become consumable in the context of the Arabian Gulf’s art scene.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years the Arabian Gulf art scene has gained considerable media attraction, not least because of human rights activists’ criticisms of labor abuses at museum construction sites (Batty Citation2014). The mistreatment of workers during the construction of the Louvre and the Guggenheim museums on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island, in particular, made international headlines. Despite continuing reports of such exploitative working conditions, labor laws in these jurisdictions have not improved substantially. At the same time that labor issues have gained a certain visibility, workers themselves remain in their minoritized position, as invisible actors in daily life. In countries such as the UAE, the resident population consists largely of foreign workers from the Global South, the silent majority that bolsters the country’s economy. International media and human rights advocates have criticized the kafala, or sponsorship system, employed in Arabian Gulf countries as inviting abuse by allowing the employer to be directly responsible for the workers’ legal residence and work permit. Artist-activists have also joined in this criticism: the artist group GULF LABOR staged several protests over workers’ long hours and low wages (Moynihan Citation2014).

While such vocal opposition by artist groups has received wide media coverage, there has been little research on how individual artists and their artworks address the ambivalent nature of the workers’ visibility and invisibility in the Arabian Gulf. Deepak Unnikrishnan, author of the prize-winning novel Temporary People, has put the matter on worker in/visibilities succinctly:

Labor isn’t invisible in the Gulf, just like it isn’t invisible in Singapore or in American cabs, back kitchens, and farms. It’s everywhere, yet the working-class laborer (pick your occupation) barely participates in Gulf society, ignored by most people, irrespective of nationality. There is a system in place turning the visible invisible and everyone participates. (Unnikrishnan Citation2015, 45)

This paper traces the work of artists who refrain from protesting labor conditions in the Arabian Gulf and who employ this ambivalence of visibility and invisibility as a technique for commentary rather than highlighting the exploitation of the worker per se. The article thereby addresses the role artists take in discussions about labor practices in the Arabian Gulf.

Theoretical deliberations on visibility and invisibility have recently gained the attention of anthropologists studying the role of images in political protests (Westmoreland and Allan Citation2016). Here I aim to add to these deliberations by analyzing artworks that seek to generate appreciatory visibilities specifically for minorities; thereby seeking to remedy some of the recently criticized lack of anthropological scholarship concerning contemporary visual culture in the Middle East (ibid.), especially on the analysis of contemporary artistic output.

In doing so, I engage with the art historian Johanna Schaffer’s deliberations in the German-language treatise Ambivalenzen der Sichtbarkeit. Über die visuellen Strukturen der Anerkennung1 (Ambivalences of Visibility: On the Visual Structures of Recognition, 2008), in which she points out that visual representations of minorities, even if they are intended to enhance visibility, often reproduce their minoritization through the visual techniques themselves. She proposes a visual strategy that instead undermines dominant hegemonic forms of representation while still maintaining the ambivalent nature of minorities’ visibility: although minorities are present in society and although their recognition is sought by and on behalf of them, their social, political, and economic issues are made invisible.

In this paper I seek to criticize and build on Schaffer’s theory in three specific ways, all of which arise from artistic engagement with labor issues in and from the Arabian Gulf. I analyze whether these artworks, which do not change or undermine their hegemonic contexts, have the potential to create appreciatory visibilities. I argue they do, although they (1) do not intervene in the grammars of representation, (2) do not try to undermine authoritarian logics by which workers have to abide, and (3) do not attempt to subvert or up-end established social hierarchies. What these artworks do instead is to fully iterate the work of the laborer in an art space, a process I call “total replication.” In the artworks, the portrayed laborers continue with their routine work, whether this consists of cleaning homes, repairing brick roads or trimming park bushes.

What is the value of an artwork that seems to completely reproduce the work conditions of laborers? How can such artworks create appreciatory visibilities? Before turning to these questions, I provide an overview of how discourses around labor have entered the Arabian Gulf art scene in connection with discourses around national heritage. In the country’s heritage regime, traditional forms of labor performed by Emiratis became celebrated, while the work of laborers from the global South became silenced.

LABOR AS HERITAGE?

The Arabian Gulf has served as a strategic crossroads for global trade both historically and in the present. Long before the discovery of oil, the Trucial States traded dates and pearls, contributing to a human trafficking industry that was part of a wider network of slavery around the shores of the Indian Ocean. Captured Africans, Baluchis, and others were transported to the Gulf to dive for pearls or to collect dates so that the New Yorkers of the 1920s could receive their dates just in time for Thanksgiving (Hopper Citation2013, 228). The history of pearl diving and date farming has found its way into national museums and heritage festivals, but the trafficking networks that were established alongside these industries are usually omitted. Few museums to date have problematized this history, although the slavery museum in Qatar is a rare exception. In heritage festivals across the country, such as the Qasr Al Hosn festival in Abu Dhabi, the heritage of work is celebrated but not critically examined. In the festival’s sea section, for example, visitors can search oysters for pearls while learning of the hardships of seafaring and pearl diving. This festival neglects, however, the socioeconomic status of the pearl divers, who were not entirely free men (Campbell Citation2005; Hopper Citation2013). Bonded labor has a long history in the Arabian Gulf and is a practice that continues today, albeit in varying forms (Begum Citation2017).

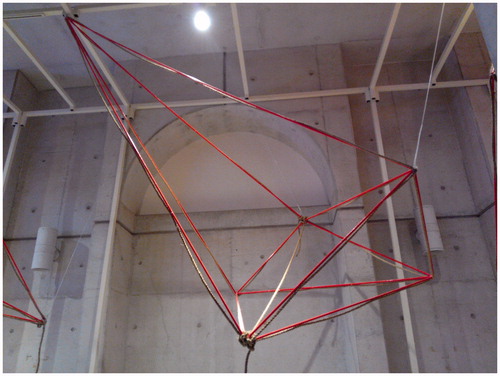

At heritage festivals, this celebration of work gets bound up with contemporary art exhibitions. At the Qasr Al Hosn Festival in 2015, a prominent place was given to Zeinab Al Hashemi, a young female Emirati artist, and her exhibited artwork, “Link between Worlds” (). The work, an installation of red poles hanging on ropes in the air, featured the sails of a dhow, a type of ship indigenous to the Arabian Gulf. The interpretive label described Zeinab’s work as “an adaptation of Emirati crafts and cultural traditions. She constantly collaborates with local artisans and redesigns their elements to form her artworks.” The label further explained that the work “incorporates traditional materials including ropes and red wire reinforcing elements of traditional heritage. The color is derived from the old Abu Dhabi flag, referencing the past within the present context.” Although the artist herself signaled the boat as a transmitter of cultural exchange in the title of the work, the description on the label molded the artwork’s meaning to the festival’s agenda. The placement of Zeinab’s artwork within the state-sponsored heritage festival illustrates the targeted efforts of cultural authorities in the UAE to combine narratives of heritage and nationalism with contemporary art. In the text, the dhow is effortlessly rebranded with national significance. The ship, a quintessential symbol of movement and of cultural and economic exchange, is made to solidify an exclusionist idea of national heritage.

Figure 1 Zeinab Al Hashemi, Link Between Worlds at the Qasr Al Hosn Festival. (Photo © Melanie Sindelar)

This “heritagization” of labor facilitates two nationalist processes in the Arabian Gulf. First, it creates memories of a past characterized by simplicity and economic hardship. Secondly, the efforts of that labor are attributed almost exclusively to Emiratis, to legitimize current claims to political rule and exclusive political participation in the country. As the British Marxist historian Raphael Samuel has suggested (Citation1996, 263), heritage “puts a premium on the labor and services of the craftsman-retailer” yet ignores every other form of work. The heritage regime as it currently exists in the UAE has no interest in recognizing the work of foreigners, which would lend legitimacy to their claims of belonging and their calls for citizenship.

Although foreign laborers have contributed substantially to the country’s economy, they are conspicuously absent in official narratives detailing the formative years of the UAE and the state’s economic success. This success is often attributed to the visionary work of the ruling families and leaders. Moreover, heritage festivals celebrate only traditional forms of work predating the formation of the UAE in 1971, the discovery of oil, and the larger influx of foreign labor that has come as a result. Foreign workers are not only forbidden to form labor unions at present, but they are also excluded from being remembered and belonging in official heritage narratives of the state. In 2013, however, Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi (Citation2013), a political commentator and member of Sharjah’s royal family, published a piece in Gulf News advocating for citizenship for certain long-term residents in the country. While granting citizenship to foreign workers remains a utopian idea in this case, countries such as the UAE and Qatar, among others, have made efforts in the last few years to reform labor laws to the benefit of workers (Begum Citation2017).

GARDENS, HOUSEHOLDS, AND STREETS: SITES OF (UN)SEEN LABOR

I now turn to the work of two artists, Vikram Divecha, born in Mumbai and based in Dubai, and Monira Al Qadiri, a Kuwaiti artist born in Senegal and educated in Japan. Divecha’s performance piece “Degenerative Disarrangement” (2013) was exhibited in a courtyard located in Dubai’s heritage district Al Fahidi (formerly called Bastakiya; ). During my fieldwork as an intern at Art Dubai, one of the houses in the district housed the studios for Art Dubai’s Artist-in-Residence program. This siting in Al Fahidi and the source of some of the studios’ funding—the Dubai Culture and Arts Authority—demonstrate how closely art and heritage are intertwined in the UAE. In the piece, bricklayers quickly arranged bricks on the courtyard floor, as they would when repairing a patch of brickwork on roadside walkways. The workers were required to complete their work within a given amount of time; the artwork thereby imposed the same time constraints that the workers face in their daily labor. This artwork made a re-appearance at the 2017 Venice Biennial, where the work was featured as part of the UAE Pavilion exhibition on the theme of play.

Figure 2 Vikram Divecha, “Degenerative Disarrangement,” 2013, 406 cm × 558 cm, interlock pavement bricks, courtyard, House 33, Al Fahidi Historical Neighbourhood, SIKKA 2013. (Commissioned by Dubai Culture and Arts Authority, courtesy of the artist)

The other two artworks examined in this article were exhibited in Sharjah, the emirate bordering Dubai. Compared with Abu Dhabi’s large museum projects and Dubai’s trade-focused art scene (including art fairs, galleries and auctions), the Emirate of Sharjah has invested mainly in not-for-profit art infrastructure. This includes the Sharjah Biennial, one of the country’s oldest and most popular art events. Despite a few past censorship cases and its social conservatism, the emirate’s output of critical art events is on a par with Dubai and Abu Dhabi. In March 2015, the Maraya Art Centre hosted an exhibition called “Accented”. Curated by Murtaza Vali, the exhibition aimed to show and negotiate the “accents” of the Gulf, the sheer variety of which creates productive tensions between different groups; the exhibition articulated the global outlook of the country as much as its local character.

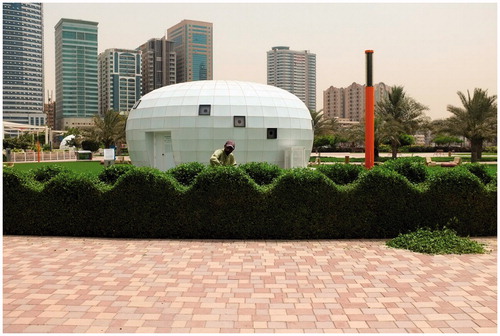

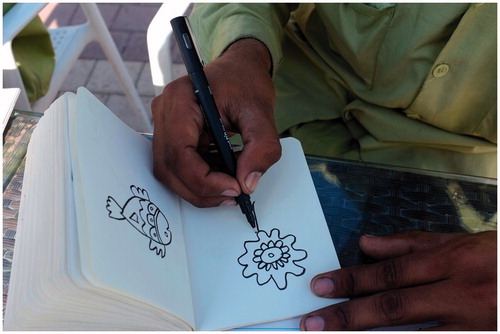

Included in the exhibition were works by Vikram Divecha and Monira Al Qadiri, along with a few other artists. Although coming from different backgrounds and producing substantially different work, both Divecha and Al Qadiri exhibited artworks that aimed to elevate the role of the laborer to distinct levels of visibility. Divecha’s “Shaping Resistance” (2015) invited Pakistani gardeners employed by the Sharjah Municipality to create bushes and hedges in the city’s Al Majaz Park in ways that they themselves deemed beautiful (Vali Citation2015, 26). Divecha allowed the gardeners to exercise an aesthetic discretion that would typically be denied to them: the shape and design of the public gardens are usually decided by the municipality. He also exhibited the sketches the gardeners used to draw. These sketches served the collective discussions on which shapes would be realized in the gardens ().

Figure 3 Vikram Divecha, “Shaping Resistance,” 2015. Municipality gardeners at a drawing workshop, Al Majaz Park, Sharjah. (Courtesy of the artist)

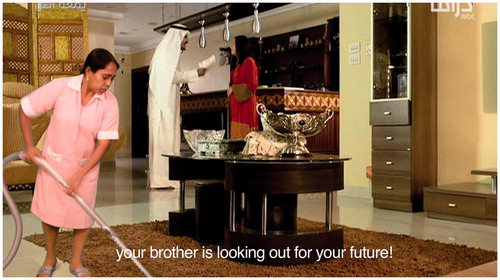

Monira Al Qadiri’s video artwork “SOAP” (Citation2014) scrutinized much-loved Gulf soap operas, which are televised throughout the region, especially during Ramadan. Most of these shows, in which domestic dramas unfold in lavish Gulf homes, do not show the domestic laborers, cooks, cleaners and maids who are part of the everyday reality for Gulf Arabs and who maintain these stunning, immaculate homes. Instead Gulf Arabs seem to magically accomplish all household chores by themselves in these soap operas. In her work, Al Qadiri reinserts the laborer into these Arab homes, where they clean, tidy, launder clothes, wash dishes, vacuum, cook, and much more. In the video, the maids then clean up after family dramas unfold at a birthday party or during family gatherings, and laborers are seen as servants in the office environment of male Gulf Arabs ().

ENTRENCHING MARGINALIZATION?

Divecha’s “Degenerative Disarrangement” and “Shaping Resistance” as well as Al Qadiri’s “SOAP” reinsert the laborer into the public sphere in their own ways. Divecha’s large interventions—others have included warehouses, roads, the waste management in Sharjah—have continued to draw attention to how labor is undervalued in the UAE. Yet visible in the gallery is only the documentation of the work; Divecha’s works are thus always ephemeral to an extent. In contrast to his focus on laborers in public spaces, Al Qadiri’s work looks at domestic labor, which often remains completely invisible. Human rights advocates have directed their efforts towards abuse specifically in such areas where labor practices, unlike in construction work, cannot be publicly observed.

These artworks have in common not only their subject matter but also an approach to their subject: they do not address labor abuse directly, as the activist group GULF LABOR did in their protests. In fact, Divecha’s and Al Qadiri’s art practice consists of replicating the laborer’s toil in the gallery space, thus aiming to produce a certain degree of visibility there. Artists in Campus Art Dubai, an art school that I attended, questioned whether that was enough as artistic critique. If it is, they asked, how can the artworks simultaneously “employ” the laborers without reaffirming their present marginality? Schaffer has similarly asked how minoritized (or marginalized) subject positions can be represented visually without perpetuating their marginalization in the form of the representation itself (Schaffer Citation2008, 161). She problematizes the relationship between visibility and power and argues that mere exposure cannot generate the change political oppositions so often desire. At its worst, these oppositions further entrench the marginalization of the groups for whom they advocate. Conditions must not only be made more visible, they must also be “seen,” according to Schaffer.

As a discourse, she points out, the idea that visibility creates power especially pervaded calls for justice for the LGBTQ community as well as for ethnic minorities. In the industrialized countries of the north, she contends, this assumption is based on an older epistemological connection between visibility, cognizance, and reality (ibid., 13). Her work builds on Jean-Louis Comolli’s notion of the “hegemony of the eye” which criticizes the idea that the function of the eye, its gaze, has come to stand for an instrument of realization and a guarantor of reality (Comolli Citation1969). Grimshaw (Citation2001) has noted that these kinds of epistemological assumptions and forms of “ocularcentrism” have also pervaded anthropological theory-building. Schaffer argues that visibility alone does not create power; if that were the case, she argues, citing Phelan, then “almost-naked young white women should be running Western Culture” (Phelan Citation1993, 10). Schaffer argues that political demands must go hand in hand with what she calls representation-critical and aesthetic considerations because they also determine the boundaries of recognition (2008, 15). She therefore proposes a visual practice that recognizes minorities without reproducing their minoritization within the artwork itself. Such visual messages require the use of the same grammar that seeks to minoritize and produce what she calls “dominant fictions”—but use that grammar in a way that misappropriates its original intentions. Schaffer takes the term “dominant fictions” from the film theoretician Kaja Silverman, who defines the term as an ideology based on the creation of a societal consensus in which a “specific representational system is taken for granted as representing reality, thereby serving as a frame of reference for collective identity and ways of belonging” (ibid., 114). These collective identities are facilitated through specific grammars of representation operating within these dominant fictions. Misappropriating the tools of that fiction then changes whether minorities are seen or not seen in a broader field of visibility.

Schaffer sees these considerations at work in Catherine Opie’s photographic portraits of LGBTQ-identifying people. These portraits aim to produce what Schaffer calls an “appreciatory visibility,” visibilities that create appreciation rather than pity by using the form of the bourgeois portrait to depict LGBTQ-identifying individuals. Opie thereby forces the honorific bourgeois form of the portrait to absorb queerness and compels the onlooker to see the portrait’s subjects in a manner that, as the queer theorist Halberstam writes, is “admiring and appreciative rather than simply objectifying and voyeuristic” (Citation1997, 183). Opie’s photographs use the dominant visual grammar of representation, a system governing the imaging of social groups, for purposes entirely unintended by the dominant fictions. Divecha’s and Al Qadiri’s works adopt a technique that differs from Opie’s misappropriation. Their artworks may have the same activist aim of creating an honorific portrayal and an appreciative way of seeing their subjects; however, they achieve this not by misappropriating elements of the dominant grammar but instead by replicating the domination, subjugation and exploitation of the worker, the marginalized subject of their artworks.

In societies that are heavily reliant on foreign workers, as in the Arabian Gulf, one might presuppose that “the worker” would find manifold entry into the popular culture, such as in dramas or soap operas. In Latin American telenovelas, for example, domestic workers are often the main characters. In Arabian Gulf soap operas, however, they are absent, as Al Qadiri makes clear. The erasure of domestic workers seems to be specific in this case and exists, I would argue, because of an ambivalence over visibility in which workers in the Gulf context are highly visible in both public and domestic spheres yet are barely “seen.” Because of this, their supposed visibility has not extended to the political sphere, where their rights are given little regard. I argue that artworks such as Divecha’s and Al Qadiri’s have the potential to move the worker from the periphery to the center of the field of vision both within the artwork itself and in society more broadly. They do so by shifting the workers as well as the grammars, logics and hierarchies in which they are embedded into the gallery space. There, dominant fictions become stripped from the “environmental” noise and are revealed for what they are: superficially created ideologies.

In the following section, I turn to how these artworks achieve appreciatory visibility through the replication of work conditions. I focus on three replications taking place within these artworks. The replication of grammars replicates the visual grammar through which the minoritized speak or are spoken for. Through the replication of authoritarian logics the artworks simulate the worker’s submission to the authority that regulates their lives. And lastly, the artworks duplicate the hierarchies and classifications that workers must navigate in their daily work.

THE REPLICATION OF GRAMMARS

Grammars of representation regulate the visual and oral language through which workers in the Arabian Gulf are recognized. The title of the exhibition in which Al Qadiri and Divecha participated is particularly interesting in this regard. The exhibition draws on the Gulf’s variety of accents, which produce a “distinct cosmopolitan ethos,” as the curator Murtaza Vali writes (Vali Citation2015, 26). He argues that accents are a linguistic tool that resists immediate translatability. In Divecha’s artwork, the shapes the gardeners chose for the hedges stem “from their visual vernacular they thought were khubsoorat, or beautiful in Urdu,” Vali elaborates. By “shifting agency from the municipality to the gardeners,” Vali explains, “Divecha’s project replaces routine order with vernacular flourish, enabling a modest moment of self-expression for a group of workers whose daily labor is otherwise largely invisible, though they toil in plain sight” (idem). Vali draws attention to this invisibility also in Al Qadiri’s work. He proposes that the reinsertion of the domestic helper into the soap operas “visually enrich[es] the texts, their bodies adding subtle vernacular accents to the generic Arabic dialogue” (ibid. 29).

But what kind of an accent can the body of a worker be and to what sort of a language? In his text, Vali uses language literally, denoting language in the Gulf as the amalgam of different foreign languages. He also uses language symbolically, however, when he juxtaposes the accent produced by workers exposed vis-à-vis regulatory systems. In Vali’s text, the symbolic language stands for either the routine order of workers, dictated by Gulf authorities or, as in Al Qadiri’s example, as a soap opera that reproduces “dominant fictions” of a luxurious lifestyle based on the labor of others.

Vali’s curatorial interpretation of Divecha’s and Al Qadiri’s works as providing new accents in the Gulf context is consistent with a particular trend in the art world. Art dealing with oppression must necessarily express relief or resistance in the same breath; otherwise the artwork’s societal contribution threatens to remain insignificant. I argue however that none of these artworks adds an accent with the capacity for agency that the curator envisioned. Instead these works must be seen for what they actually do: replicating the toiling of the laborer as faithfully as possible. The few additions and changes that exist do not articulate resistance; they rather operate within the authority’s logic and employ the grammars with which the dominant fictions speak. Such grammars, operating within dominant fictions and circulating in a field of visibility, regulate how a majority sees and perceives a minoritized group in everyday life. Grammars of dominant fictions thereby ensure that minorities can be seen only through certain lenses: as a guest worker, a cleaner, a maid. Seen through these grammars, the worker cannot be recognized outside this logic or their original contexts, whether the high-rise building construction site or the home.

The artworks by Divecha and Al Qadiri replicate the dominant grammar in the gallery space in two ways: first, the workers do not leave the place of work, and second, they continue to perform their usual tasks. They remain bound in their place of daily work, entrenched in the very activities that render them invisible. The gardener remains in the garden, trimming hedges and bushes. The domestic worker is confined to the home, completing the usual household chores. The artists do not provide them with a different kind of task; there is no revolutionary attempt to “free” the workers from their work, even when they are given license to shape it, as in Divecha’s “Shaping Resistance.” The gardeners may be permitted to trim the bushes as they choose, but this does not change the fundamental nature of their work: the gardeners still trim hedges, the domestic worker still cleans the house, the road worker still repairs the road. The workers remain embedded within the dominant fictions in which they are represented.

This form of replication—the replication of grammars—has the potential to create appreciatory visibilities, precisely because it does not disrupt the established field of visibility. These artworks do not formulate alternative realities of freedom that remain only hypothetical anyway. Such counter-fictions in fact would present scenarios that are so surreal (at least in the context of the Gulf) that they would serve only to produce pity rather than appreciation in the viewer. By contrast, Divecha’s and Al Qadiri’s artworks extract the labor from its normal workplace and surroundings and insert it into the unexpected space of the gallery.

This process, I argue, makes it possible for the viewer to focus on the actual work in ways that would not be possible in the home or on the street, where the dominant fictions disguise the workers’ presence as an ordinary part of that environment. Provocatively put, labor is so taken for granted in the Arabian Gulf that the absence of the domestic worker, for example, remains unnoticed until Al Qadiri reinserts her into the soap opera scene. By replicating labor in an exhibition, artworks enhance that labor in the context of the art space and thereby create the potential for viewers, maybe even for the first time, to really “see” the laborer’s toil.

THE REPLICATION OF LOGICS

How can a practice of “seeing,” however, rather than just “being exposed to,” be possible if it remains conditioned by the authorities’ logic? To operate according to their logic entails obeying a given set of rules. For example, workers (in the Gulf and elsewhere) risk losing their jobs and their income if they fail to comply with working hours or hectic deadlines. The presented artworks however not only reproduce, as stated above, just one part of a given system: they also reproduce exactly the logic that regulates that daily work and the compliance of the laborers. In this section, I present two ways in which the artworks replicate compliance to the authorities’ logics. First, I examine how the compliance of the worker is replicated in the artworks. Secondly, I reveal how the artists themselves, in their art practice, also comply with these authorities.

In Al Qadiri’s work, compliance with authoritarian logic can be traced in the scenes the artist chose for the domestic worker’s reinsertion. Several scenes show how Gulf protagonists walk through the maids as if they were not there. Their presence is required yet is hardly above notice, similar to the country’s treatment of workers in general, as Deepak Unnikrishnan’s statement at the opening of this article made clear. In the video these workers continue to clean, regardless of the drama that unfolds around them: they toil nonstop, as they would in reality. Domestic workers in the Arabian Gulf have one day off and are otherwise required to remain in the house, available to work. Taxi drivers serve 12-hour shifts, as several Pakistani drivers told me during fieldwork and as was reported in the UAE’s national newspaper, The National (Webster Citation2015).

The replication of logic can also be found in Divecha’s work “Degenerative Disarrangement.” Workers reassemble bricks in the same manner as when employed at their actual work—including being under the same time pressure. The “disarrangement” in the artwork stems from the effect of real-time pressure associated with taking bricks from the area surrounding the BurJuman Metro and rearranging them in a courtyard within the so-called heritage district in Al Fahidi.

The courtyard house once hosted a works-in-progress exhibition of Art Dubai’s artists-in-residence, including Divecha. Many visitors failed to notice Divecha’s artwork and walked over it, illustrating not only the invisibility of the artwork but of the labor itself. Outside a designated art space the work failed to garner the same visibility it generated at the Venice Biennial and other art contexts. In this and other works, Divecha alters hardly anything in what he terms “found processes.” In a recent interview, he told Harper’s Bazaar Art Arabia: “In many ways, I feel like I am doing what someone suggested was ‘putting feathers on the water,’ you know? Something that creates a little ripple, but does not disturb everything, and cascade out” (Lichty Citation2017, 37).

Divecha’s work with laborers raises important questions as to how he involves his “collaborators,” as he calls them. Aima, an art writer based in Dubai and New York, has rightly pointed out that Divecha’s art practice poses “a danger of treating workers as the city’s overseers do—as raw material to be ferried about and used before being discarded.” His work, she argues, “always risks instrumentalizing his collaborators” (Aima Citation2017). Indeed, it is noteworthy that for both “Degenerative Disarrangement” and “Shaping Resistance,” Divecha was required to obtain the permission of the authorities to employ and collaborate with the workers. Forced to comply with government regulations, he became subject to the authorities’ logic. Whereas Vali describes Divecha’s art practice in his curatorial interpretation as “shifting agency to the gardeners” (2015, 26), I propose that agency remained where it “belonged” according to the authoritarian logic: with the government authorities. Without their permission the artwork would not have been possible; the artist was thus made dependent on their goodwill.

During my fieldwork stay in Dubai I noticed how artists engaged critically with Divecha’s work in several ways. Divecha not only exhibited his work in Sharjah but presented the work in progress at the Campus Art Dubai art school, which he was attending at the time. It was located in the A1 art space in the old part of Alserkal Avenue, a conglomeration of galleries situated in Dubai’s industrial district, Al Quoz (which has recently seen further expansion). Campus Art Dubai is an initiative of the art fair Art Dubai and is led by a team of experienced art curators and artists. The internship and the 2015 cohort offered crucial points of contact for my research. The school hosted many artists who possessed UAE residency permits but no possibility to obtain citizenship, artists I will here call “resident artists.” These people were most critical of Divecha, himself a resident artist.

In his presentation at the Campus Art Dubai, Divecha mentioned his desire to “give back agency” to the gardeners in “Shaping Resistance.” Several of the artists in the school questioned Divecha’s capacity to do so, especially given the way he situated his art practice in “found processes.” One of the participants questioned whether the artwork could generate resistance to the authorities' logic, a critique I have described above. She remarked that the only resistance artists in Dubai are willing to commit to is “flirting with institutional critique”: they do not follow through. “There is no real resistance here!” she exclaimed. Another artist drew attention to the dilemma of formal dependence upon the very institutions that artists seek to criticize. It was a vicious cycle: “You critique the institution, but the institution funds your critique! Aaah!” He threw his arms up in despair. Although the artists criticized Divecha’s work and process, they did not have a solution for this dilemma, one that also affects their own art practices.

Divecha’s process, which required the workers to comply with the authorities’ logic, also facilitated, however, the authorities’ cooperation: specifically, Shurooq (the Sharjah Investment and Development Authority, who supported the exhibition) and the Sharjah Municipality. The choice to collaborate with city authorities that regulate workers’ lives poses a dilemma for the artist. Schaffer (Citation2008) rightly points out that resistance always comes with formal dependence on the hegemonic structures it seeks to criticise. By replicating the toil of the laborer in the space of a public gallery they raise questions about the labor on exhibit, even if these questions are not accompanied by explicit advocacy for labor rights. When Divecha invites laborers to reassemble bricks under the same time constraints they face in their usual work, or when he allows gardeners a marginally greater say in their usual routine, he exposes not only their work but also the conditions under which they are forced to labor ().

THE REPLICATION OF CLASSIFICATIONS AND HIERARCHIES

Another central aspect of Schaffer’s theory on the ambivalences of visibility concerns the analysis of artworks that invert or subvert hierarchies. Here I investigate how the replication of hierarchies and classifications can nevertheless generate the reflexive space necessary for what Schaffer calls a “productive look.”

Schaffer argues that the confusion of classifications and hierarchies is a necessary condition for resistance against essentialism and exclusion (ibid., 157). She explains that this confusion is based on a process called disidentification, a term borrowed from the performance theoretician José Esteban-Muñoz. This is a practice “which neither rejects nor fully identifies with materially and psychologically anchored places in dominant cultures” (Esteban-Muñoz Citation2007, 35). This process could be “dangerously prone to interpretations of nonidentification, nonidealisation, nonrecognition, and nonvisibility—yet thereby dissolving form—not a rearrangement, but a nonarrangement, that works to declassify, and as it does so, confuses classifications and hierarchies” (Schaffer Citation2008, 163). Disidentification, Schaffer argues, is also the precondition for the creation of a reflexive space that would ultimately enable a “productive look,” a concept initially developed by Silverman (Citation1996), that requires viewers to see through dominant fictions and open up their visions to Otherness.

Schaffer’s desired confusion of classification and hierarchies is palpably absent in both Divecha’s and Al Qadiri’s work. Neither the maid nor the gardener swaps roles with the employer. On the contrary, hierarchies and classifications are omnipresent in the works of both artists. This creates a confusion with respect to their works, one that comes from the absence of a political statement, rather than from vocal criticism of labor abuses. Their work engages the onlooker in thinking further, deeper: why bring the daily work of a laborer into a gallery? This is the kind of ambivalence through which their work operates, an ambivalence of visibility and invisibility. I argue this ambivalence opens up space for these works to be hosted by a government-sponsored public art gallery in the UAE.

In Al Qadiri’s “SOAP” one scene predominates: it shows a girl celebrating her 15th birthday with female members of her household (). The party, which takes place in a lavish living room, is exuberant. The girl blows out candles on a cake, and the women dance around a table covered in flowers and presents. The celebration comes to an abrupt stop when the family father returns home and sees what the women were doing in his absence. The music turns dramatic. The father stares at the women in shock and disbelief and rests against the table. “Singing and dancing. Singing and dancing in my house? Singing and dancing in my house?” He hurls the flowers and cake onto the floor and screams, “How dare you!” The women shriek in horror, huddling together to protect themselves from the father’s wrath. Meanwhile, two maids have started to clean up the mess. “You should be ashamed! Shame on you!” Another set of flower bouquets and glasses land on the floor. The birthday girl is terrified and starts to cry. The father throws the remaining plates on the floor, sideways in the direction of the maids. The girl flees the scene while the father whispers again, “Shame on you. You should be ashamed of yourselves.” He starts to scream, pounding his fists on the table, “Shame on you!” The remaining women and the grandma are the last to rush out. Now alone, the father leans on the table and whispers to himself, “Despicable. Despicable, despicable …” He is close to tears. “How dare they!” he bursts out, throwing more and more on the floor. The maids continue to clean up after him, unresponsive to the scene. The floor is now littered with the remnants of the party. The father sinks down to the floor, supporting himself on the table, one hand on his lap. The other hand too slips to his lap lifelessly. The video ends here, and the work’s title, “SOAP,” projected in white on a black background, starts to appear.

This scene in “SOAP” draws attention to domestic violence, targeted not only against family members in Arabian Gulf homes. Al Qadiri’s reinsertion of the domestic worker shows that domestic workers are exposed to and bound to endure the same domestic violence. The vulnerability of domestic workers is corroborated by recent reports from Human Rights Watch (Citation2014): legal protections for domestic workers remain the weakest of all protective measurements for workers in the Arabian Gulf. Noticeable in the video is that Al Qadiri does not attempt to subvert the hierarchies in the scenes taken directly from Gulf soap operas. Besides the insertion of the maids cleaning, there are no changes to the plot or the scenes.

Neither Al Qadiri’s nor Divecha’s work attempts to subvert hierarchies or classifications in the way Schaffer intends. The maid does not switch roles with the Gulf protagonists; she remains in her position. The maid also is not depicted as a white woman, which would pose another interesting subversion of hierarchy, given the Arabian Gulf’s large so-called “expat” population employing domestic workers as well. Similarly, Divecha’s art practice does not attempt to lift the gardeners out of their position. The artist himself does not swap roles with the gardeners; he lets them work. Could this be the marginalization that Schaffer has warned us against? How can such artworks create appreciatory looks, even if they do not have a desired level of criticality both demanded by the artists in the field and the theoretical construct of Schaffer? I turn to this question now.

POLITICS OF ART

In the three preceding sections I mentioned that the artworks of Divecha and Al Qadiri do not conform to pre-set expectations of how art must be “critical” to be impactful. “Critical” denotes that the artwork either creates a potential to imagine alternative realities (i.e., by subverting hierarchies, reclaiming agency for the worker, etc.) or that the work is accompanied by calls for justice. Divecha’s and Al Qadiri’s artworks do not employ either of these artistic strategies. This apparent reluctance to provide criticality within their art practice has garnered criticism from both art critics and fellow artists attending the art school mentioned earlier. The art writer Aima (Citation2017) problematized Divecha’s general line of work as “questionable” because of “his depoliticized engagement with labor—there’s no call to improve manifestly unjust structural conditions.” She believes however that “Shaping Resistance” differs from Divecha’s other works, since here “there’s a quiet and admirably non-flashy resistance in the way the artist tries to reconnect workers with the creative side of their own labor” (ibid.).

Two questions can be raised regarding Aima’s critique. First, why are artworks that are not accompanied by a vocal call for the rights of the laborers regarded as depoliticized? One could argue the artwork contains a political message already. Divecha’s and Al Qadiri’s art seems to allow for forms of institutional criticism that are permissible and consumable without having to resort to blunt political statements or futile objections in the face of authoritarian governments and a history of unsuccessful protests. Secondly, the artwork as a channel for critique can more effectively engage the viewer in the critical discourse than traditional political protest. The two are not always mutually exclusive, though members of the GULF LABOR group found this regrettably to be the case when it concerned the Guggenheim museum negotiations in Abu Dhabi:

Defiance is welcomed when it is sanctioned and staged as art. Drill a crater in the floor, flood a gallery, embalm an animal, smash an object, stage a pitiful death—critics hail these gestures as having the power to “shape worlds.” But when artists sit down at a conference table with museum administrators and read from a list of demands for labor rights, this work—involving conversation, negotiation, research, protest—suddenly becomes illegible to the same museum. The artists whose projects were previously praised as stretching boundaries are now tagged as maverick spoilers. (Mohaiemen and Haacke Citation2016)

To refrain from placative criticism that could expose unjust treatment by these authorities and embarrass them also maintains what Schaffer has called the majority’s “sovereignty feeling.” Recognition is given to minorities only if the majority’s feeling of sovereignty is not threatened; that is, it is given only conditionally. This “recognition in the condition” (2008, 11), however, regrettably also serves entirely different subject positions. Most notably it serves what Markell has called the “desire for sovereign agency” (Citation2003, 5). Through the replication of the current social order and the violence that inheres in that reaffirmation, artworks have the potential to enable audiences to “see” the art rather than just being exposed to it.

In Silverman’s understanding, this “seeing” needs to be possible “in ways that are to varying degrees independent of the given-to-be-seen” (1996, 181), a practice she calls “productive looking.” For productive looking to become possible, one needs to engage in an act of “heteropathic recollection,” a process of identifying the self with the not-self. This process then influences “mnemic operations,” not only in recalling what “resides outside the given-to-be-seen,” but what the very “moi excludes,” “what,” as Silverman explains, “must be denied in order for myself to exist as such” (ibid. 185). Gulf soap operas, to return to one of the case studies, do not only erase the domestic worker. The erasure of their work is necessary for an ambiguous lifestyle entirely reliant on the worker’s presence, on the one hand, but denying the worker’s constant presence because of its threat to the “moi,” on the other hand.

Al Qadiri’s “SOAP,” by reinserting that worker, challenges the mnemonic reservoirs of those who enjoy domestic help but at the same time try to gloss over their presence. What a “heterotopic recollection,” mediated through an artwork, would do, Silverman says, is to “introduce the ‘not me’ into my memory reserve” (idem). Artists bring the presence of domestic workers into the forefront of an art exhibition, thereby confronting viewers with the issue of labor and labor conditions in the Arabian Gulf. Artworks such as Al Qadiri’s thus provide a way “through discursively ‘implanted’ memories” as Silverman says, “to participate in the desires, struggles, and sufferings of the other, and to do so in a way which redounds to his or her, rather than to our own ‘credit’” (idem).

Divecha’s and Al Qadiri’s artworks replicate the dominant practice of representation, but in a context that enables them to create appreciatory visibilities. The toiling of the laborer, when replicated in an art space, is stripped from its embeddedness in everyday life, thereby creating a form of attention that laborers would not receive in their usual surroundings. In an art context, most viewers anticipate provocation, criticality, or shock. The artworks do not deliver that. These artworks do not provide the satisfaction that viewers typically receive when they visit a gallery or museum to view art that makes a political or social critique. Simply by attending the exhibition the viewer can have a role in the critique: “I visit the exhibition, thereby I support the exhibited resistance art, thereby I take part in the resistance.” With works such as those by Divecha and Al Qadiri, the viewer cannot take part in the act of resistance, since there is none. The artworks do not grant the viewer that kind of satisfaction. One could even argue that these artworks’ power only fully unfolds with the viewer – the viewers’ hypocrisy becomes exposed through their own gaze.

The artworks also do not represent, nor indicate the potential for, the upending of the hegemony. They replicate the hegemonic system in the art space. In this replication lies the artworks’ potential: they trigger in the viewer an uneasiness that does not usually arise from seeing workers trimming hedges in an actual garden or a household help cleaning up in one’s own kitchen. Workers usually are so embedded in hegemonic contexts that they become glanced over by the majority, as do their demands for better labor rights. In the art context, however, onlookers are forced to see; they cannot glance over the workers, they cannot relegate them to the periphery of the field of vision. Privileged viewers are placed in a position that makes them aware of dominant grammars, authoritarian logics, and hierarchies and classifications. The replication of their work and working conditions in an art gallery’s white-cube environment—like Opie’s portraits—forces the viewer to “see,” and in a way, this grants appreciatory recognition to the work these laborers perform.

ART-HISTORICAL CONCEPTS AND THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CONTEMPORARY ART

In this article, I have taken Schaffer’s theoretical concept of the ambivalences of visibility and invisibility and argued for the potential of artworks to create appreciatory visibilities for marginalized subjects without subverting hierarchies, changing the grammars of representation, or triggering shock. While I assert—in the context of the several artworks presented here—a view that is contrary to what Schaffer suggests, I seek not to negate her findings but rather to expand them to other sociopolitical contexts.

Schaffer’s theoretical considerations are based on artworks that create the conditions for productive looks mostly in democratic and Western settings. While she does not assert that the potential of disidentification, if based on the confusion of hierarchies and classifications, is potent regardless of place, the absence of a clearly stated delineation of a zone of cultural or geographic applicability leaves her theories vulnerable to popular anthropological critiques of Eurocentrism. Nevertheless her choice of artworks and their contextualization in specifically democratic settings should make evident that potential accusations of imposing Western art history’s universalizing assumptions would be misplaced in this specific case. In fact, Schaffer herself takes apart the universal idea that visibility creates power and shows that it does not seem to hold even in the “highly industrialized societies of the North” (2008, 13).

Art-historical and anthropological critiques of these universalizing principles do however remain relevant. Nevertheless, art-anthropological critiques must move beyond ethnocentrism, especially considering new emerging monolithic ideas of what constitutes global art. New anthropological engagement with evolving art market structures has become crucial since they reveal that attention to global art means, first and foremost, “considering the global art worlds-network as constituted of multiple interconnected centres” which “shifts the attention to regional exchanges” (Fillitz Citation2015, 311). In this vein, the article has highlighted art produced in one of these emerging art centers in the Middle East.

Marcus and Myers (Citation1995) once noted that art history and anthropology are related disciplines and that their boundaries have never been clear. Anthropologists such as Winegar (Citation2006), Steiner (Citation1994), Fillitz (Citation2018) and Myers (Citation2007), to name but a few, have shown that art concepts previously accepted as universal are not applicable to different cultural contexts, and have exposed universalist tendencies in art-historical and anthropological scholarship. At the same time however an engagement between the two disciplines can be worthwhile. By moving beyond an a priori dismissal of art-historical concepts anthropologists engaging with these concepts can discern whether there are concepts that can be rethought and criticized productively. In light of this, the present article has attempted to engage in such a rethinking of Schaffer’s concept of the ambivalences of visibility.

CONCLUSION

I have here argued that artworks that do not carry criticality as an apparently inherent feature can still create appreciatory visibilities. I have thereby relied on Schaffer’s theorization of the ambivalence of in/visibilities. Unlike Schaffer, who proposes the necessity of disrupting dominant narratives, which govern how marginalized individuals are represented in order for them to be seen, I have argued that an exact replication of these conditions in a gallery space can also create the potential for a productive look. Creating this look, as she argues, does not necessarily require the invisible to replace the visible. Instead, the ambivalence of visibility and invisibility itself can be productive and generate a productive look. The ambivalence of visibility and invisibility namely also points to the ambivalence with which workers in the Arabian Gulf are treated. “Visible” demonstrations of appreciation, like public Ramadan meals or honorary ceremonies for workers who helped build the countries are common, but happen side by side with the continuing exploitation of labor.

Using examples from two artists based in the Arabian Gulf I have analyzed how their art practices reproduce the toiling of the laborer in an art space and hence draw attention to labor issues faced generally by workers in the Gulf. I argued that these artworks reproduce not merely one aspect of a laborer’s work conditions but aim to reproduce them true to scale, or what I call “total replication.” I then analyzed the three elements of this replication—dominant grammars that serve to build dominant fictions, the authoritarian logic under which workers labor, and classifications and hierarchies prevalent in Gulf society—and discussed what my arguments imply for the creation of a productive look and appreciatory visibility. In the last section, I positioned this article within wider debates on the relationship between anthropology and art, proposing that more nuanced engagement with art-historical constructs may be a worthwhile endeavor.

Al Qadiri’s and Divecha’s approach, which refrains from explicit calls for labor rights, has garnered criticism from other artists in Dubai for the inability to effect actual agency for workers and for the inadequacy of its critique. For artists in the Arabian Gulf whose work comments on labor practices, the decision to reproduce the work environment rather than make blunt critical statements about laborers, however, allows their artworks to be exhibited and celebrated, rather than censored and condemned. The controversy that surrounded one of the exhibited works at the Sharjah Biennial 2011 revealed quite clearly where the boundaries lie. An Algerian artist’s work, “Maportaliche/Écritures sauvages” (It Has no Importance/Wild Writings), was censored after it encountered strong public protest. The work, as the curators said, “borrows the voice of rape victims at the hands of religious extremists in Algeria” (Kennedy Citation2011), and as the artist Mustapha Benfodil said later in a statement, “refers to a phallocratic, barbarian, and fundamentally liberticidal god” (Masters Citation2011). It seems the artwork’s message was too explicit, too blunt for what can be exhibited in Sharjah’s public eye.

The Sharjah censorship case generated intense international attention, and no censorship cases of such notoriety have occurred since. For artists living and working in the UAE, calling the cities of Dubai, Sharjah, or Abu Dhabi home, creating similarly provocative artwork could mean the revocation of their residency permits and the end of their careers in the country—and therefore the end of their interventions, however subtle these might be. In the UAE, artists currently remain damage-mitigators at best, not reformers. Their work constitutes the nuanced political opposition the state otherwise lacks; it has therefore become indispensable. It remains to be seen whether focusing directly on the labor exploitation would effect any change. Creating ambivalent artworks that move between modes of visibility and invisibility, reinserting the laborer yet simultaneously abstaining from direct protest, as is done in both artworks, also refrains from what Schaffer calls “misery voyeurism” or Elendsvoyeurismus (2008, 21). Artworks depicting abuse too directly might be accused of their probable non-effect on politics, non-dignitary accounts of personal lives and stories, and the profit-seeking behavior of placing them into semi-commercial or commercial contexts.

The fact that the work of Divecha and Al Qadiri has been shown in one of the state’s most conservative emirates speaks volumes about changing practices of “seeing” and “recognizing” as well as an increased openness to artistic critique in the country. Maraya’s current director is a German art historian, and its in-house curator is American, but the Art Center is funded by Shurooq, Sharjah’s Investment and Development Authority and is thus government-funded. If the authorities in the UAE open up and foster further respect for artistic critique, then art will be given the opportunity to become an important voice in shaping state–citizen and state–noncitizen relationships.

NOTE

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Melanie J. Sindelar

Melanie J. Sindelar is an IFK Junior Fellow Abroad (International Research Center for Cultural Studies Vienna, University of Art and Design, Linz) at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle/Saale, and also a PhD Candidate in the Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Vienna.

Notes

1 All translations from Schaffer’s book, originally in German, are my own.

REFERENCES

- Aima, Rahel. 2017. “Atlas Dubai: Consumed Culture.” Art in America, January. http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/magazine/atlas-dubai-consumed-culture/

- Al Qassemi, Sultan S. 2013. “Give Expats an Opportunity to Earn UAE Citizenship.” Gulf News, September 22. http://gulfnews.com/opinion/thinkers/give-expats-an-opportunity-to-earn-uae-citizenship-1.1234167.

- Batty, David. 2014. “Call for UN to Investigate Plight of Migrant Workers in the UAE.” The Guardian, July 13. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/sep/13/migrant-workers-uae-gulf-states-un-ituc.

- Begum, Rothna. 2017. “Gulf States’ Slow March toward Domestic Workers’ Rights.” https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/06/16/gulf-states-slow-march-toward-domestic-workers-rights.

- Campbell, Gwyn. 2005. “Introduction: Abolition and its Aftermath in the Indian Ocean World.” In Abolition and its Aftermath in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia, edited by Gwyn Campbell, 1–28. (Studies in Slave and Post-Slave Societies and Cultures.) London, UK: Routledge.

- Comolli, Jean-Louis. 1969. “Technique and Ideology: Camera, Perspective, Depth of Field.” In Vol. 2 of Movies and Methods. An Anthology, edited by Bill Nichols, 40–57. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Esteban-Muñoz, José. 2007. “Queerness’s Labor oder die Arbeit der Disidentifikation.” In Normal Love: Precarious Sex, Precarious Work, edited by Renate Lorenz, 34–39. Berlin: B books.

- Fillitz, Thomas. 2015. “Anthropology and Discourses on Global Art.” Social Anthropology 23 (3):299–313. doi: 10.1111/1469-8676.12215.

- Fillitz, Thomas. 2018. “Concepts of ‘Art World’ and the Particularity of the Biennale of Dakar.” In An Anthropology of Contemporary Art: Practices, Markets, and Collectors, edited by Thomas Fillitz and Paul van der Grijp, 87–101. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Grimshaw, Anna. 2001. The Ethnographer’s Eye: Ways of Seeing in Anthropology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Halberstam, Judith. 1997. “The Art of Gender: Bathroom, Butches, and the Aesthetics of Female Masculinity.” In Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography, edited by Jennifer Blessing, 176–88. New York: Guggenheim Museum.

- Hopper, Matthew S. 2013. “Slaves of One Master: Globalization and the African Diaspora in Arabia in the Age of Empire.” In Indian Ocean Slavery in the Age of Abolition, edited by Robert W. Harms, Bernard K. Freamon and David W. Blight, 223–40. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Human Rights Watch. 2014. “United Arab Emirates: Trapped, Exploited, Abused; Migrant Domestic Workers Get Scant Protection.” https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/10/22/united-arab-emirates-trapped-exploited-abused.

- Kennedy, Randy. 2011. “Sharjah Biennial Director Fired over Artwork Deemed Offensive.” New York Times, April 7. https://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/07/sharjah-biennial-director-fired-over-offensive-artwork/.

- Lichty, Patrick M. 2017. “Feathers on the Water.” Harper’s Bazaar Art Arabia (Summer) 2017, 34–37.

- Marcus, George E., and Fred R. Myers. 1995. “The Traffic in Art and Culture: An Introduction.” In The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Anthropology, edited by George E. Marcus and Fred R. Myers, 1–54. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Markell, Patchen. 2003. Bound by Recognition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Masters, H. G. 2011. “Director’s Ouster Jeopardizes Sharjah Art Foundation’s Future.” ArtAsiaPacific, April 18. http://artasiapacific.com/News/DirectorsOusterJeopardizesSharjahArtFoundationsFuture.

- Mohaiemen, Naeem, and Hans Haacke. 2016. “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Campaign on Gulf Labor and Western Museums in the Middle East.” Walker Art Center Magazine, (December 7). http://www.walkerart.org/magazine/2016/gulf-labor-hans-haacke-naeem-mohaiemen.

- Moynihan, Colin. 2014. “Protesters Urge Guggenheim to Aid Abu Dhabi Workers.” New York Times, May 24. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/25/nyregion/protesters-urge-guggenheim-to-aid-abu-dhabi-workers.html.

- Myers, Fred R. 2007. Painting Culture: The Making of an Aboriginal High Art. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Phelan, Peggy. 1993. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. London, UK: Routledge.

- Samuel, Raphael. 1996. Theatres of Memory. London, UK: Verso.

- Schaffer, Johanna. 2008. Ambivalenzen der Sichtbarkeit: Über die visuellen Strukturen der Anerkennung. (Studien zur visuellen Kultur 7.) Bielefeld: transcript-Verlag.

- Silverman, Kaja. 1996. The Threshold of the Visible World. New York: Routledge.

- Steiner, Christopher B. 1994. African Art in Transit. (Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology 94.) Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Unnikrishnan, Deepak. 2015. “Gulf Sounds.” In Syntax Freezone, edited by Rahel Aima and Ahmad Makia. Dubai, UAE: The State.

- Vali, Murtaza. 2015. Accented: Curated by Murtaza Vali. Sharjah, UAE: Maraya Art Centre.

- Webster, Nick. 2015. “RTA to Review Dubai Taxi Drivers’ Long Working Hours.” The National, March 30. https://www.thenational.ae/uae/transport/rta-to-review-dubai-taxi-drivers-long-working-hours-1.82260.

- Westmoreland, Mark R., and Diana K. Allan. 2016. “Visual Revolutions in the Middle East.” Visual Anthropology 29 (3):205–10. doi: 10.1080/08949468.2016.1154414.

- Winegar, Jessica. 2006. Creative Reckonings: The Politics of Art and Culture in Contemporary Egypt. (Stanford Studies in Middle Eastern and Islamic Societies and Cultures). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

FILMOGRAPHY

- Al Qadiri, Monira. 2014. “SOAP.” Monira Al Qadiri, producer; color, 8.08 mins. video.