Abstract

In this paper I provide baseline estimates for the scale of black-and-white photography as a locally run, commercial undertaking in Cameroon both before and after independence. In categorizing, starting with short 19th and 20th centuries, I end by suggesting a better division is between an era of Colonial Photography (roughly 1865-1955) and a shorter period of larger-scale Administrative Photography (1955-1985), the so-called “Golden Age of the Studios.” I estimate that the number of commercial photographers there had grown to approximately 1,400 by 1985, with a cumulative total of more than 3,500 photographers. These figures provide a context for the detailed discussion of any one photographer, where it is important to know, for example, whether he/she was one in ten or one in a thousand.

WHAT IS THE QUESTION?

As the pop song tells us, there are more questions than answers (Nash Citation1972). Some questions look simple but turn out not be so; others seem hard from the start. The history of photography has many seemingly straightforward questions which defy the provision of straightforward answers: “How many photographs were taken in the 19th Century?” looks like a simple question, yet a little reflection shows how difficult (indeed impossible) it is to answer. Even “How many photographs survive from the 19th Century?” is well nigh impossible to answer. In my case, as a specialist in the study of the West-Central African country of Cameroon, the question(s) that exasperate with their seeming simplicity concern the number of photographers operating at various moments in national history. Such questions arise when undertaking detailed study on an individual photographer (or even an image or set of photographs). In these cases it helps to know whether the photographer was, for example, one in ten rather than one in a thousand. Any question of how exceptional an individual is implicitly invokes a discussion of sampling and representativeness (in the statistical sense rather than the sense in which it is usually discussed in this journal). It may be that we end up with guesswork, but educated guesswork is better than guessing at random, and the hope of this paper is that we can produce some reasoned estimates that can at the very least demarcate the likely ranges within which the figures should fall.

Consider the following questions: (1) How many photographers worked in Cameroon in the 19th Century? (2) How many in the 20th Century?1

Immediately we need to start being more precise, and eliminating some categories, because there are several apples-and-pears issues here between amateurs and commercial practitioners, between Europeans and Africans. The choice of categories which I have sought to explore reflects my own interests rather than being a priori definitive. I leave to others to explore the photographs taken in this area by missionaries, colonial officers and other expatriates. My questions can be refined as:

(3) How many African commercial photographers worked in Cameroon in the 19th century? (4) How many in the 20th century?

Note that for Cameroonian history the sensible date to end the “19th Century” is 1916 when German colonial rule ended—almost 90 years after the invention of photography. Moreover, for this exercise the 20th century ends around 1985 with the arrival of cheap color analog processing and auto-focus cameras which signaled the end of widespread quasi-professional photography.2 This also predates the arrival of digital photography in Cameroon. So this historical exercise is resolutely analog (and almost entirely black-and-white). In sum, we have two periods of about 80 years to consider. In most of what follows I concentrate on the 20th century.

Some other prefatory remarks are in order. There are, of course, uncertainties about who counts as an “African” photographer.3 There is certainly a risk of over-essentialized, racialized tropes of who counts as African, who as European. That there were photographers active in Cameroon early in the period concerned who came from Lebanon underlines the fragility of the classification.4 Some 19th-century examples have been uncovered in which African photographers had originally been assumed to be European on the basis of their names alone; Jonathan A. Green (Anderson and Aronson Citation2017), John Parkes Decker (Schneider Citation2013) and Neils Walwin Holm with his son Justus A.C. Holm (Gore Citation2013; Gbadegesin Citation2014) being cases in point.

The Lutterodts provide another interesting case (Haney Citation2013), being a Ghanaian-German/Danish family who established early photo studios in several places along the littoral of the Bight of Benin and who certainly worked in what is now Cameroon (they probably had a studio in Batanga near Kribi, according to Geary Citation2010, 91). This leads to the second remark: sometimes we must distinguish African photographers who worked within the borders of present-day Cameroon from those who were born within those borders. This means we often need to ask two or possibly even three different questions:

(5) Who were the photographers that worked in place x?

(6) Who were the photographers from place x?

(7) Who were the photographers from place x who worked in place x? (i.e. who were the local photographers?)

For example, along the western border between Nigeria and Cameroon many people report that the first photographers in the area were Nigerians (readers should note that Southern Cameroons (now South West and North West Regions) was administered by Nigeria from 1922 to 1961 under the aegis of, first, a League of Nations mandate, and secondly, a United Nations trusteeship). Nigeria later became a major source for photographic materials: film, printing paper and chemicals.

A final note on definitions concerns the professional vs. commercial distinction. I am using the word commercial advisedly, to exclude amateur photographers such as any early military personnel, missionaries or administrators who took photographs. I am not using the word professional since although many were fully professional, for some it was but a small ancillary occupation aside from their main livelihoods. The aspect of importance is that the people I am concerned with provided photographic services to those beyond their immediate family and friendship circles, and did this as a commercial service, as often manifested by the marking of the prints they produced with stamps or signatures on the reverse. I am also excluding the staff of professional photographers who were employed by the Cameroonian government and other parastatal agencies (e.g. Cameroon Development Corporation, CDC, whose photographic archives seem not have survived) both before and after independence.5 The work of the government photographers is held in the photo archives of the Ministry of Information and in related services and the Buea Press Photo Archives (BPPA). This exclusion is because there is no uncertainty about the existence of the material (even though there may be concerns about its long-term archival preservation; cf. Nsah Citation2017 and Schneider Citation2018b on the BPPA) and the basis of its creation.

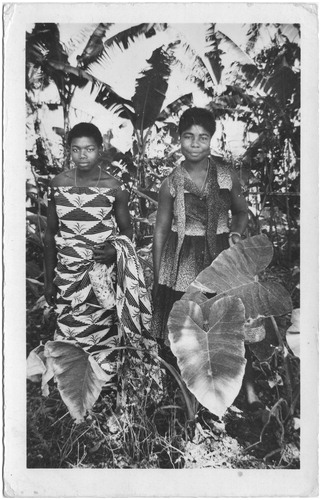

I am concerned with the African photographers who plied their trade along the West African coast towards the end of the 19th century, as documented by Haney, Geary, Schneider and others. I am also concerned with photographers such as the person in the entourage of Njoya, the Sultan of Foumban, who became his personal photographer in the early years of the 20th century (see below) and the many photographers who worked either as itinerants or from studios, especially in the second half of the 20th century.

As we have seen, the questions concern how many commercial African photographers have worked in Cameroon (ca 18656–1985, but mainly 1880–1985), that is, from the arrival of photography until the arrival of automated color processing laboratories in Cameroon brought an end to black-and-white analog photography processed and printed by the photographers. These questions are easy to ask, but hard (almost impossible) to answer. However, it seems that no one has ever actually attempted to provide a principled answer, so this paper stands as a first attempt at establishing a method which might be generalizable, at least for the 20th century. To anticipate my conclusions, the hope is that making explicit the assumptions needed for these quantified procedures will provoke further research to provide some secure datum points.

THE 19th CENTURY

Granted the scale and state of documentation, the methodological challenges are very different in the 19th century, where we must rely on standard historiography. As we shall see, some alternatives are possible for more recent times. The sources for African photographers in Cameroon during the 19th century are, as might be expected, fairly meager. We appear not to have had as extensive a legacy as is found in some neighboring countries, such as Senegal (Evans Citation2015) and Liberia, although W.S. Johnston from Freetown visited Douala as an itinerant photographer working his way up and down the coast from the 1860s to 1893 when he established his studio in Freetown (Geary Citation2010, 89). As Geary puts it (2013a, 215), “African photographers were highly mobile, establishing businesses along the African coast all the way from Senegal to Angola” (Schneider Citation2010, Citation2018a; Haney Citation2010). Another summary is that

From the late 1860s, West Africa saw the establishment of permanent studios run by Europeans, Africans and photographers of mixed origins. Washington de Monrovée opened the first studio in St-Louis (Senegal) in 18607 and was followed by Decampe the next year. Gerhardt L. Lutterodt, operating between Freetown (Sierra Leone) and Douala8 (Cameroon) in the 1870s, trained his nephew Freddy (b. 1871) and son Erick (1884-1959) who opened studios in Accra in 1889 and 1904, respectively. (Eze Citation2008, 15).

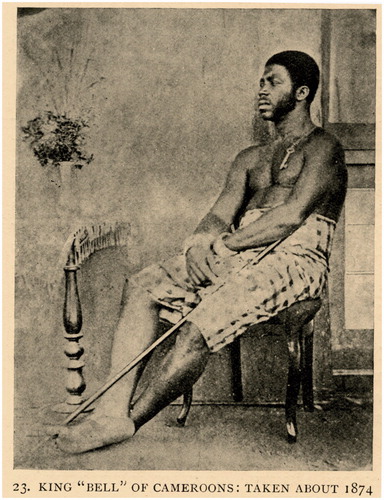

The first record of an African photographer active in Cameroon is from an illustration in Johnston (Citation1908): page 56 includes a photograph of King Bell from Douala taken “about 1874.” We don’t know who took the photograph, however this image clearly has a backdrop which is evidence that it was taken by a commercial and not an amateur photographer. And at this point in time this probably means it was an African, not a European, photographer. Given the date it might have been taken by Gerhard Lutterodt or perhaps by William Mudisa Bell ().

Figure 1 King Bell from Douala, taken “about 1874”. (Johnston Citation1908, 56)

In the Basel Mission photo archive there are two images dated 1890 and 1910 from Bonaku (Douala), with a photographer’s stamp “William Mudisa Bell” (). He was almost certainly a member of the Douala Bell family and therefore a very early Cameroonian photographer, although it has been impossible to find much more about him. Anonymous (Citation1899, 27) describes “William Bell” as a photographer who was Manga Bell’s brother, living near him in Douala. An early missionary, Helga Bender Henry, describes “William Bell” as “Manga’s nephew” (Citation1999, 111-112), and as helping the allied ships to dock in Douala early in the Cameroons Campaign of 1914 — evidence of the Bells’ anti-German feeling.

The online genealogy for the Bell family9 includes someone with a similar name (Moudissa Dikoume Bell) but with different dates, possibly a descendant of the photographer. In effect all we have to go on is the rubber stamp on the back of the photos (see above) and the dates given in the Basel Mission catalog indicating he was active over at least a twenty-year span. The only other information comes from some letters in German archives. The Frobenius Institute has correspondence between Bell and the missionary Bohner showing that in 1897 Bell had headed notepaper as well as the rubber stamp. In a letter written in English dated September 30, 1897 (and using British £-s-d currency) Bell gives the following prices: “The price of negatives only 15/- each on large photo. And if you want it on finished or cards ½ doz almost 8½ x 6½ photo 36/- one doz about 8½ x 6½ 60/- all finished.” A few years later (in 1903 and 1912) Bell wrote to the trader Eduard Woermann asking that his son be sent to Germany for education. (There is no evidence that this happened.)10

Other photographers were also operating at this time. Eve Rosenhaft notes “two members of the Joss family, another leading Duala clan, and a Paul Mukeke from Malimbe were all apprenticed to photographers in Germany between 1896 and 1910, and another Cameroonian, Anjo Dick from Duala, described himself as a photographer when he arrived in Germany in 1913” (pers. comm., my emphasis). No examples of the work of any of these photographers have yet been documented.

According to Christraud Geary (Citation2010, 91), Gerhard Lutterodt had a studio in Batanga (near Kribi) from the 1870s until 1890, when he moved to Fernando Po. To confuse matters his brother Frederick R.C. Lutterodt also worked in Victoria (Limbe), although the dates for this are not clear and it may have been as an itinerant from Fernando Po. Geary also has evidence that even before this the Liberian photographer W.S. Johnston (not to be confused with the missionary author Harry Johnston mentioned above) was working along the coast as an itinerant photographer on steamers, and was making regular visits to Cameroon (ibid., 89).

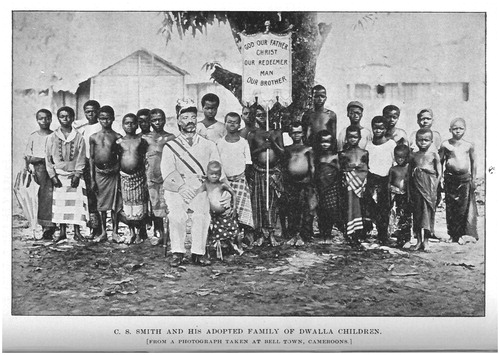

The missionary Charles Smith stopped in Bell Town (one of several independent entities that became Douala) on his way to the Congo, as recorded in his book Glimpses of West Africa:

2 October 1894 I proceed to Bell Town in a canoe which was furnished for me by Prince Manga, this being my third visit to that place. I take with me my Knight Templar accoutrements and a banner representing the A.M.E. Church and its Sunday School Union. On landing I stop a few moments at “Royal factory” where I make arrangements with a native photographer to photograph a group which I will arrange after my visit to King Bell. (1895, 174).

A few pages later we find a description of another visit to King Bell: “At the close of the interview I repair to the shade of a mangrove tree, and surround myself with a number of native children, and have a photograph taken. I try in vain to have King Bell sit for a photo” (ibid., 178-179). A print based on this photo is printed on his page 179 without attribution. Other images in the book include attributions to the photographers (including G.I. Lutterodt in what is now Ghana). In the absence of further information this may have been William Mudisa Bell who as we have seen was active then (Gerhard Lutterodt had by then moved to Fernando Po) ().

Figure 3 C.S. Smith and his adopted family of Dwalla children. (Smith Citation1895, 179)

As has already been mentioned, King Njoya from Foumban was reported in 1916 as occasionally taking photographs himself and having his main scribe (the Nji derema)11 take pictures during important events (Geary Citation2013a, 224-225; also Geary Citation2004, 149-151; 2013b: 85, 84-88). Geary quotes a military source from early 1916, when the British occupied Bamum for a brief period, as follows:

“By this time we had about enough of the show, and the inevitable photographer appeared. The king keeps his own private operator for photographing himself and his 600 wives and 149 children. We then formed the usual semi-circular group and were “taken.” The king expressed a wish to […] have a photograph of our men, saying that he liked the Indian soldier. So we formed them up in readiness; nothing would then satisfy the king but to be taken with them, so his attendants brought his throne out and placed it in front of the line. The king seated himself gravely on it, and the first photograph of a native king surrounded by Indian troops was taken. […] The whole effect was weird but not unpleasing, and the local majesty makes a very imposing figure when filling the throne, which he does very successfully.” (Geary Citation2013a, 224)

Njoya was influenced by missionary photographers in Foumban such as Anna Rein-Wuhrmann, but also acted in conscious reaction to them – Njoya was nothing if not an actor, even inventing his own religion (Tardits Citation1996) and a new writing system, and then converting to Islam as part of a struggle to demonstrate his independence from the Germans (and subsequently the French). In many works over the last thirty years Chris Geary has discussed the nexus of photography in Foumban where missionaries and Njoya coexisted for more than a decade before the First World War (Geary and Njoya Citation1985, Geary Citation1988, Citation1996, Citation2010, Citation2013a). This continued after the war, until Njoya’s fall from grace. According to Galitzine-Loumpet (Citation2006, 46) Njoya acquired a camera around 1920, though it was banned in 1924 as he fell from French favor.

If the list of names in seems implausibly few, then we should take it as a clear signal that more research is needed. At least it can serve as some basis for a continued search for evidence of more early photographers perhaps in Buea (which became the German administrative capital before it moved to Yaoundé) and Victoria/Limbe (which was an important center of missionary activity even before German colonization).

Table 1 The Short 19th Century (1865-1916), a Summary

THE 20th CENTURY

Readers should recall from the introduction that, taking a leaf from Eric Hobsbawm,14 I am concentrating on a short 20th century, 1917-1985, starting after the German colony fell to the allies in 1916. At about the same time as the immediate repercussions of the First World War were resolved and the German colony of Kamerun was split between French and British administrations under League of Nations Mandates, the technology of photography had changed so that it became much easier to shoot, develop and print images, the prices fell, and more and more people took up the practice. Such is the global generalization, but what were the impacts in Cameroun?

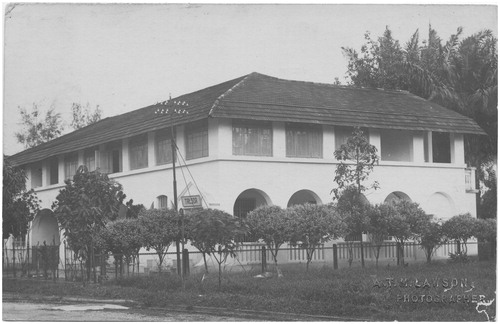

The photographer George E. Goethe (born 16 August 1897 in Sierra Leone,15 died 1976 in Douala) was one of the first Africans to establish a studio in post-WWI French-administered Cameroun (in 1933). As Nja Kwa (Citation2004) makes clear, George Goethe arrived in Cameroon in 1922 working for John Holt Ltd. He opened his first studio informally in 1923,16 and then went professional as Photo Georges in Douala in 1933 (Derrick [Citation1978, 215] gives the start date as 1930, Geary [Citation2013b, 84] as 1931). ().

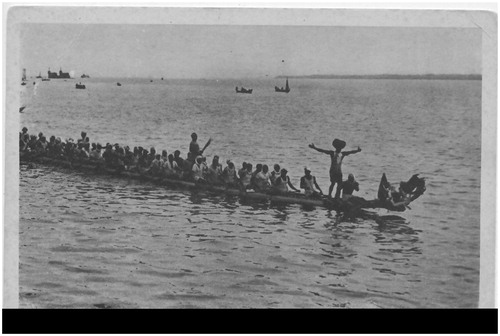

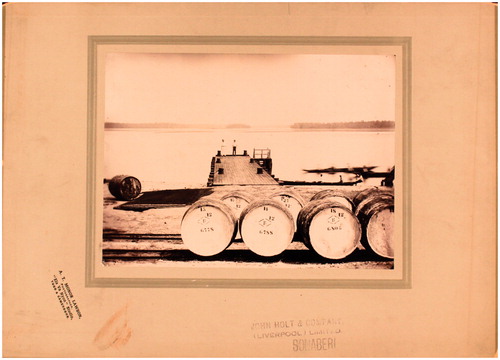

For the early period 1917–1933 when Photo Georges was established, there is little information about other African photographers operating at the beginning of our short 20th century.17 One such was A.T. Monor Lawson, who worked in both Togo and Cameroon (both pre-WWI German colonies). He took photographs for John Holt in Douala in 1916 and later made several postcards of scenes in Cameroon ().

However, a file in the Cameroon National Archives, Yaoundé, from 1927 provides a useful baseline.18 The file, Carnet d’identité des indigènes (APA 11326/B), discusses identity cards and how they can be verified as belonging to particular individuals. The Commissaire pour le Cameroun Français, Théodore Paul Marchand, considered photography and, as an alternative, the relative length of the index finger as unique identifiers (detailed instructions about how to measure finger length were circulated).

Marchand recognized that photography would only be viable if photographers were available for the local (indigène, i.e. African) population to use. As a consequence the file records a circular enquiry about the availability of photographers. It was sent on 3 Aug. 1927 to the heads of Circonscriptions in Dschang, Ebolowa, Yaoundé, Kribi, M’banga, Yabassi, Doumé, and Lomie (and clearly, in the light of the answers, was sent to others as well). Over the next two months some responses were received:

1(?) Aug. 1927 1 photographer in Mbanga

12 Aug. 1927 no photographers in Ebolowa

18 Aug. 1927 no photographers in Yabassi or Ndiki

23 Aug. 1927 1 photographer in Nkongsamba, none in Dschang or Bafoussam

17 Sept. 1927 none in Doumé

22 Sept. 1927 1 photographer in Yaoundé, none in Bafia, Akonolinga or Yoko

In short, across south Cameroon only 3 photographers were reported as operating in 1928 (although this excludes Douala). Insufficient to enable ID photographs to be produced, the idea was dropped; although as Schler notes, Marchand “remained convinced that a photograph would be the best method of identification, he provided a budget for each circonscription to buy a camera and train one of its African interpreters in its use” (2008, 85). No enthusiasm was displayed for measuring fingers, so this also appears not to have been implemented. However, for the purposes of this paper, the correspondence establishes a plausible calibration point for our counting exercise.

By the time the studio Photo Georges was active in the 1930s there were general stores in Douala run by Europeans (usually French) which also served as photographers. Examples include Établissements R. Guerpillon. We do not know who actually took and processed the photos, but it is likely that these were locals, possibly trained by the proprietors who happened to be amateur photographers, who then saw a way of introducing photography into their business. Some, for example, Robert Guerpillon and also Raphaël Pauleau, also produced postcards of local scenes, as did various missionary organizations () and African photographers including George Goethe, A.T. Monor Lawson, Neils Walwin Holm and his son (Geary Citation2013b and Citation2018 provides a good summary history and further illustrations).

Figure 7 A.T. Monor Lawson postcard: The treasury in Douala (note the blind stamp impressed lower right; Zeitlyn personal collection)

Figure 8 Établissements R. Guerpillon postcard: 38–Pirogues sur le Wuri (http://www.cparama.com/forum/cameroun-t7354.html; accessed 23 Aug 2018)

ESTIMATING THE NUMBERS OF PHOTOGRAPHERS

I now consider three different means of estimating the numbers of photographers active in Cameroon over time, before comparing the results from these different procedures.

1. By Population

Some authors working in other parts of West Africa have presented data that correlate the number of photographers with the size of the local population they serve. This suggests a means to estimate the numbers of photographers active in Cameroon. However, we must ask if it is legitimate to use figures from Côte d’Ivoire to produce estimates for Cameroon? Despite the distance and the differences between the different countries the accounts from Werner (e.g. 1996) and Nimis (2013), as well as those from Ghana (Wendl Citation1999, Citation2001, and Haney 2010) and Liam Buckley for The Gambia (Citation2000/1 and Citation2005), suggest very similar working conditions and social environments for photographers across West Africa; and so it seems not entirely implausible to apply the figures derived from research in Côte d’Ivoire to the situation of photographers in Cameroon. (It may be that future research will be able to demonstrate where significant differences lie and these may prompt a revision of the estimates that follow.)

Érika Nimis (Citation2013, 116) provides some figures from Côte d’Ivoire (and Niger): in Abidjan in 1963 there were 217 photographers serving 350 thousand people so about 1 studio per 1.6 thousand people. By 1976 this had risen to 239 studios serving 500 thousand people (roughly 1 studio per 2,000 people). However, she also cites (ibid., 118-119) Werner’s work in the town of Bouaké (also Côte d’Ivoire). Werner (Citation1996, 87) quotes a survey from around 1970 that recorded 64 studios (i.e. 1 studio for every 2,700 people). Taken together these figures suggest 1 studio per 2 thousand people might be a reasonable estimate (although it clearly has a wide variance reflecting our great uncertainty; see below). In the figures generated below, I used a cautious figure of only 1 studio per 2.5 thousand people, which produces lower estimates.

Nimis used official records such as tax payments and membership of professional photographers’ associations. Inspired by her example I tried to do the same in Cameroon. Initial attempts made little progress: when I approached tax officials in Bafoussam they said that almost all photographers evaded registration (and also claimed that archives have not been preserved). I was told a very similar story in Mbouda, where the photographer Jacques Toussele said that he paid the patente (commercial trading license) because “he was so prominent he couldn’t not pay” (my gloss), but the others did not need to. I return to this issue below and show how later work in the Cameroon National Archives has produced results that allow us to test a straightforward estimate of numbers based on Nimis’s ratios between photographers and population.

There is one important caution to state before we proceed. When using the following tables we must be conscious that the historic population figures are unreliable. We have to remember that there are differences in area considered sometimes from one year to the next (certainly between decades),19 differences as to whether the figures give the total residents or if they separate indigenes from allogenes (who may or may not include Europeans). Even some of the most authoritative surveys give different figures on different pages (e.g. Mainet Citation1985, 20 gives a population for Douala in 1939 as 35,000, but on page 61 gives the population for the same year as 41,812 + 20,790 (“strangers”), which is almost double, so these are not necessarily small or insignificant differences). Such concerns are then magnified by further issues about reporting. Kuczynski (Citation1939, 127) is rightly alarmed by the errors in some of the French annual reports to the League of Nations: mistakes in the layout put figures for births and deaths in 1931 and 1932 in the wrong columns one year, which were then uncritically repeated in subsequent years. Quite apart from printing errors Kuczynski also provides a damning review and critique of the demographic figures themselves (1939, 88-94). Happily for the purposes of this paper we can use the best population figures we can obtain, while recognizing that there is a high level of uncertainty about them. Orders of magnitude are sufficient for the purpose of the estimates being produced here, any figures better than that are bonuses, albeit unreliable ones.

Having given such an emphatic health warning about these data it is worth reiterating the point made above, about the goal of this paper being to provide reasoned figures that may help constrain our guesswork; in other words, so that we can provide educated guesses. I have tried in what follows to not be dependent on any precise values of population but to follow the broad patterns of growth which may be discerned for all the huge uncertainties that obtain. Some may feel that such is the lack of reliability of the figures as to render their use otiose. These readers would prefer to answer my initial questions with a version of “don’t know, can’t know.” Nonetheless I think some rough and ready approximate answers can be provided, as we will see.

The following uses more recent city population data, which are somewhat more reliable than those considered above (downloaded from the United Nations, http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=POP&f=tableCode%3A240, based on the Cameroon national census).

Table 2 Population and Number of Photographers for Major Cameroonian Cities

The last three columns give the estimated number of photographers on the basis of different ratios, as suggested by Nimis and Werner. So the column headed ‘Phr./1.5K’ gives an estimate for the number of photographers if there were one photographer for every 1,500 people, and so on.

In order to undertake a longer-term comparison between this method and the other methods considered below I have also collated population figures for Douala from 1925. I discuss these in the comparison section below.

2. Tracking Early Licensed Photographers in Cameroon

As suggested by Nimis’s work, another way of estimating the number of photographers is through the records of commercial licensing in French-administered Cameroon. My specific starting-point for data on this was Jonathan Derrick’s doctoral thesis, in which he mentions that the Annual Reports for Douala during the Colonial period give the numbers of commercial licenses issued to photographers20 (Derrick Citation1978, 361 and 381 for 1930 and 1929 respectively; the information is also given in Derrick Citation1989, 110).21 With that prompt and the help of some staff from ANY I have collated the figures for Douala and Yaoundé, using the surviving Annual Reports in the National Archives. This however does not include towns in west Cameroon, such as Buea, Limbe/Victoria or Bamenda, since these were under a different administrative regime (administratively part of Nigeria first as a League of Nations mandate territory then, after World War II, as a United Nations trust territory) which meant that commercial activity in these places did not have the same system of licensing until some time after independence.

Since the Annual Reports from the major cities list categories of activity including photography as a heading we can use these as proxies for the development of photography as a commercial practice. Another major health warning must be issued: it is absolutely certain that these numbers are under-estimates. The people who took out the commercial licenses (patentes in French) were the success stories, those with permanent studios who could not avoid the attention of the authorities. All would have started more or less informally and probably without fixed studio premises, so then could avoid the expense of registration, of paying the tax associated with the issuance of a commercial license, until they become too big or successful to avoid it. The annual reports therefore list the successful entrepreneurs who we know to be the tip of the iceberg: the working assumption has to be that most of the photographers active at any one time were unregistered and remained invisible. Accepting this point, what the figures do show is the growth of photography as a commercial activity, from the tiny numbers active before 1930 to the somewhat larger numbers working (and even registering) by the end of the 1950s.

Note that according to the 1938 Annual Report to the League of Nations (Anonymous Citation1938, 147), photographers needed a 7th-class license which then cost 400 Francs in Wouri (i.e Douala), 350 Francs in zone 2 (broadly southern Cameroun) and 300 Francs in the rest of Cameroun (ibid., 146). These licenses had to be renewed annually and so were a recurrent tax on commercial activity.22

For the years where the Annual Report was traceable in ANY in early 2018, we have collated the number of licenses issued to produce .

Table 3 Commercial Licenses for Photographers in Douala and Yaoundé

Table 4 Growth of Administrative Centers (from the data appendix for Zeitlyn Citation2018)

Some points arise immediately from this. First, although we have no data from 1927 when the ID photo circular was being considered, we do have figures from both 1926 and 1928 which seem to suggest that the pessimism of the official figures was misplaced. Possible explanations for this include that some of the licenses were issued to European photographers catering for European clientele, workers who the administrators responding to the circular judged not to be interested in undertaking mass ID photography for Cameroonian clients. Against this however we must recognise that the categorization is specific: these were patentes issued for those described as photographers. Many expatriates who took photographs commercially, such as Guerpillon, were primarily general traders and would have been licensed commercantes, including their photographic activities under this license. Another more prosaic explanation is that the administrators did not know very much about the area they were based in and were not concerned to investigate even their own files before sending their replies.

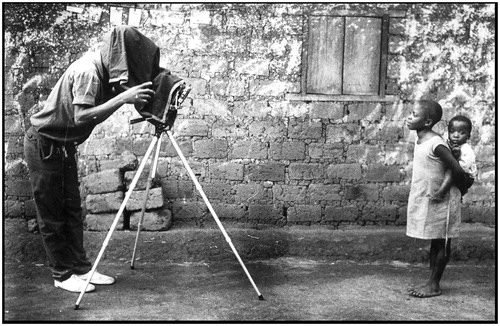

Secondly, we should revisit the suggestion that the numbers of official licenses dramatically underestimates the actual numbers in the earlier years. While it is certain that they are underestimates, they may not be too inaccurate in the early periods. The assumption that many photographers were able to avoid notice and escape paying the license may be an unwarranted one. The assumption about how easy it was for a photographer to be mobile and stay out of the attention of the authorities risks technological anachronism. As far as I have been able to establish from interviewing old photographers about what their teachers used and how they worked, until the 1960s photography in Cameroon was not a very mobile profession. The use of glass plates and tripod cameras was the norm until they were replaced by medium-format cameras using celluloid roll film during the 1960s, all but vanishing by the end of the 1970s (but see ). So a photographer would only be somewhat mobile, and was encumbered by bulky equipment, which meant that it would not have been easy to evade the police if working, for example, at a small local market. This implies that these figures may be less inaccurate than suggested by an image of itinerant photographers with small 35 mm or even medium-format cameras in mind. John Fox’s photograph () from Atta shows that tripod plate cameras remained in use in some parts of Cameroon until the early 1980s. One can speculate about how many unregistered photographers there were for every one who paid his license. As this paper argues, the numbers from archives and other sources can at least help anchor and constrain such speculations.

3. Administrative Development and Photography

The final method we shall consider takes as its starting-point the list of administrative centers as it developed over the years. We can use this as the basis to estimate the numbers of photographers active at any one time. This enables us to consider the effects of the assumptions being made in producing these estimates in a systematic and principled fashion.

For administrative purposes Cameroon is divided into Régions (formerly Provinces), Préfectures (Divisions), and Sous-Préfectures (Sub-Divisions; see ). These units have centers that are towns and cities of varying size.

The estimate procedure starts from making some assumptions about the numbers of photographers that each administrative level could support, since so many documents (certainly after independence) require that ID-style photos be attached. As well as the direct connection between administrative procedures and the need for photography, there is a more general point that an administrative center will be also an economic center for the surrounding area and so will attract potential customers for a photographer.

The calculation assumes that in the early years a Regional Capital could support 10 photographers, a Préfecture 3, and a Sous-Préfecture 1. We change these assumptions in 1953 when ID cards with photographs became compulsory, increasing to a Regional Capital supporting 20 photographers, a Préfecture 10, and a Sous-Préfecture 3. The figures used are my estimates, based on discussions with old photographers mainly active during 1960–1990 as well as on an ongoing survey of photographers by using their identifications on the backs of prints in private albums and collections.

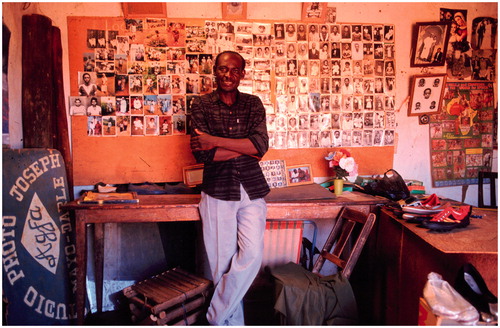

There are variations and exceptions, of course: there were plantations on the coast (run by CDC and others) and inland (e.g. at Nkongsamba) which supported additional photographers so that workers had a chance to send photos back home.23 Another exception was the village of Mayo Darlé, which because of its tin mine supported a community of migrant laborers which in turn supported a photographer from 1970 to about 1985 (Chila Joseph, a former apprentice of Jacques Toussele; ); this was long before it became a Sous-préfecture in 2010. However by the time this photo was taken the economic boom in Mayo Darlé had ended, as the mine had closed in the early 1980s. By the late 1990s Chila had closed his studio too and moved to Bankim where he ran a small shop (taking photographs as a sideline). His departure from Mayo Darlé and the absence of a successor are clear indicators that the Golden Age of studio photography had passed.

Figure 11 Joseph Chila in his Mayo Darlé studio in 1993. Note the shoes for sale on the right: Chila was diversifying. (Photo: John Fox)

On this basis we can take the list of current administrative centers24 and chart when they achieved each status, which will allow us to produce our final set of estimates.

We can use this Table to produce the following estimates for the numbers of photographers working in Cameroon (). The calculation has been made on the following basis. Since photographs only became compulsory on ID cards by the mid-1950s25 different sets of assumption were made about the numbers of photographers that each category of location could support at different periods; increasing after 1955 and decreasing after our period ends by 2000 as digital ID cards began to be introduced.

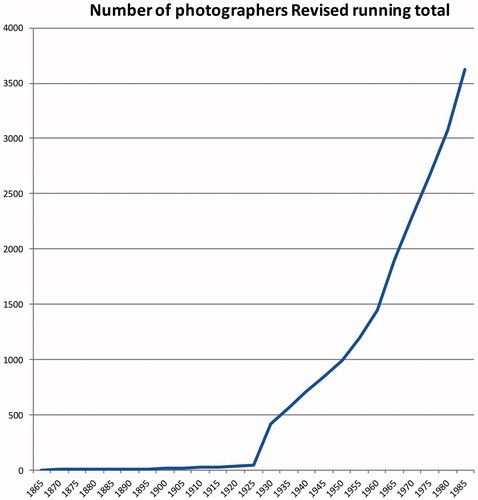

Table 5 Photographers and Administrative Growth

Shown as a graph this Table produces . The key features of the graph are driven by the scaling factors and the changes I have made to them. To repeat, the point of the exercise is to prompt us to reflect more critically on the assumptions being made so that they can be adjusted as appropriate on the basis of reasoned argument. For example, it seems appropriate to change the scaling factors in 1955 when photographs on ID cards had become compulsory. Were we to continue the estimates into the current century it might be appropriate to make another change, to reflect the way digitized ID cards removed some of the market for commercial photography (a market already made less profitable by color processing labs). The discussion is now made specific rather than remaining vague.

COMPARISONS AND CONCLUSIONS

We have considered three ways of estimating the numbers of photographers active in Cameroon: by population, on the basis of commercial licenses, and from the growth of administrative centers. We can now see how they compare and might be combined. The main test is to compare the figures for Douala, since we have fairly good data for that city.26

Douala features in the administration-based estimate figures as having the following number of photographers (). We should note that although after independence it is a Regional, Divisional and Subdivisional center, before 1960 it was only a Divisional27 and Subdivisional center.

Table 6 Douala Administration-Based Estimate

We could easily argue for some sort of exceptionalism, on the basis of Douala’s long established position as an economic and trading capital, which might well have increased the number of active photographers, a point to which we will return. covers the years ca. 1925–1955 for which we have Patente data.

Table 7 Different Estimates for Douala before Independence

The figures in suggest that the administration-based estimates have not kept up with the size or economic scale of Douala’s expansion in this period, but later on they may not be so bad (). As we have already noted, the Patente figures are likely to be underestimates because of evasion (though the scale of this can be exaggerated). Using the most conservative calculation of number of photographers on the basis of population (1 per 2,500 people) produces figures somewhat higher than those produced from Patente counts or the administrative structure estimates, but are of the same order of magnitude, which is encouraging. One thing to note is how the population of Douala dropped during World War II when its activity as an international port was drastically reduced. When we start to consider ways in which this can be generalized, one thing that we have to recall is that until recently the population of Cameroon has been predominantly rural, and that although itinerant photographers would go round village markets their bases have predominantly been urban. This is where the charting of the development of administrative structures may become helpful. If we were to assume that a Subdivisional center that is not also a Division had a population of 15,000 and a Divisional center 30,000, then this gives us a new way to estimate numbers for the whole country. For now I am leaving out the Regional centers. Unlike the previous calculation about administrative growth, there is now a double counting issue to take into account. A Divisional center will be a Subdivisional center as well. In the previous calculation I took the view that since there was an administrative division of labor between administrative units (so that different documents, many with photographs, were dealt with at different levels), one town within a Divisional center and a Subdivision could support the number of photographers that any Subdivision could maintain plus additional photographers for that Division. When we move to population-based calculations we have to distinguish places that only have a Subdivision from Divisional centers (which always include a Subdivision, and in more recent years possibly several). I am using the conservative ratio of 1 photographer per 2,500 people.

CUMULATIVE TOTALS

The figures in show the number of photographers working at any one time.

Table 8 Population-Based Estimates Following Administrative Growth

Since some photographers worked for many years (Photo Georges in Douala is a prominent example) we cannot simply add up the figures in the right-hand column. Instead we have to make further assumptions about how many photographers (how many studios) fail, and how long they take to go out of business. The work I and others have undertaken in Mbouda gives some indicators. Jacques Toussele started in the 1960s and retired around 2000. Of the other photographers who had been active at that time in Mbouda only one, one of Toussele’s pupils, became an established photographer. Mckeown (Citation2010) gives a snapshot and Tatsitsa (2015) some biographies of former photographers from an outlying village.

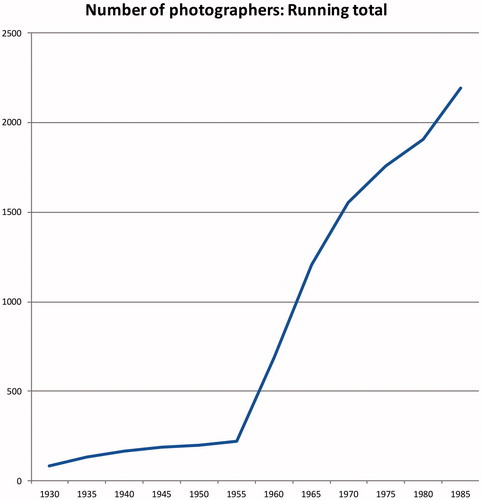

In order to arrive at some figures I have assumed that the number of studios working will halve in ten years. In other words, of 100 studios working in Year X, 50 would still be working after 10 years and 25 after twenty years have elapsed. This is a classic “half-life” calculation. Thus after 40 years only about 5 might still be operating. This seems to fit fairly well the exceptionalism of long-enduring studios such as Photo Georges in Douala and, to a lesser extent, Photo Jacques in Mbouda. Another way of thinking about it is that if we look at the figures from for two dates ten years apart, then half the studios in the later date are assumed to have been in operation at the earlier date but half are newcomers. The cumulative total has to count both the long-lasting studios and those that come and go. On this assumption the cumulative number of photographers is as shown in . shows this as a graph.

Figure 13 Number of Photographers against time. Constant most conservative basis for calculation, 10:3:1.

Table 9 Cumulative Number of Photographers in Cameroon

I will discuss these tables below. Before considering them, we should look at some tests of the approaches we have been considering.

TESTING THESE APPROACHES

We can test these approaches by looking at data from other places and by comparing research on photography in certain places. One test comes from Nkongsamba where we have patente data for 1949 (with 2 photographers licensed) and 1950 (4 photographers licensed).28 Since at this point it was both a Divisional and a Subdivisional center using the same basis for the number of photographers in different administrative structures, as used above in , it would be estimated to have 4 photographers, which fits the records nicely.

Using some figures from Awambeng (Citation1991, 106-107) for places in the North West Province (now North West Region), we can compare his figures for 1985 with the estimates as follows, in .

Table 10 Comparing Estimates for Places in the North West Region

There may be a scaling effect: as a city gets larger it becomes harder to undertake comprehensive surveys.29 René Egloff addressed this in his doctorate on photography in the city of Bamenda by undertaking fieldwork in the city as well as undertaking surveys. His thesis contains a long footnote (Citation2013, 121) in which he estimates the number of itinerant photographers in Bamenda in 2005 as falling in the range 88–129. I note that these are itinerant photographers, not studio photographers, and that this is some twenty years after the end of my periodization, by which time digital photography was beginning to have an impact. Egloff’s 2005-2006 survey (ibid., 66-67) recorded 81 photo studios and 7 photo labs, along with records of 44 historic studios (those no longer functioning, although no indication is given as to when they went out of business).

We should note that for 2005 the administrative structures-based estimate is only 13 for Bamenda (the Subdivisions Bamenda 1, 2 and 3 were only introduced in 2007). So perhaps these estimates hold for non-regional centers, or for earlier periods but not ones as recent as 2005, when the Golden Age of studio photography was over? This is not implausible, since the idea and definition of a commercial photographer begins to break down once anyone with an autofocus camera can take reasonable shots that may be processed and printed at a laboratory, perhaps with some then sold to acquaintances. Egloff discusses this in terms of the rise of semi-amateur itinerant photographers. Werner (Citation1997) also discusses the rise of such itinerant photographers relying on photo labs for processing and printing.

The population-based estimate for Bamenda in 2005 is

These figures are close to those of Egloff’s estimate for itinerants (the middle of his range is 109) and for the number of studios (81). If we add studio numbers with the middle of his range for itinerants we get 109 + 81 = 190. This would suggest a population-based estimate closer to 1 photographer per 1,500 people; but if we concentrate on the studio photographers and omit the itinerants then 1 photographer per 2,500 or possibly even 3,000 would be closer. As I have said, in the calculations I have used 1 photographer per 2,500 people, erring on the side of caution since this ratio produces the lowest estimates.

As a final test of the figures for Bamenda we can compare Egloff’s figures with the number of studios recorded via the rubber stamps on the backs of prints. In a collection of photographers’ stamps from Cameroon covering all periods I have 117 from Bamenda. This includes stamps collected by Egloff and others and several repeated entries for individual studios, since some studios had several different stamps over the years. Disregarding these duplicates leaves records of some 81 studios in Bamenda. This is a misleading coincidence with Egloff’s 2005 figure: the real comparison should be made with this plus the 44 defunct studies: it means we should compare 81 studios documented via rubber stamps, with 125 studios documented by Egloff’s survey and field research, suggesting that my sample has reached approximately 2/3 coverage. The orders of magnitude are the same, which may be the significant test. To hope for a closer coincidence may be stretching the methods being used, although further refinement of the basis of these estimates is possible.

EXCEPTIONALISM

I have already hinted that Douala may be a special case. Other places may also have supported more photographers than the general approach that has been taken so far would suggest. I do not think this invalidates those approaches nor would it make significant changes in figures (in the period 1955–1995). For the record, candidates for exceptional status aside from Douala, the international port city, are Garoua, the major administrative center in the north; Nkongsamba, a major center of plantations; Victoria/Limbe, another port and a very early center of Missionary activity; Buea, the former German capital, capital of British-administered Cameroon and then of West Cameroon in the Federal Republic 1961-1972, a place which also supports nearby plantations; and of course Yaoundé, the national capital. Military bases are another possible exception, since like plantations or mines they gather people from all over the country earning wages that can indirectly support photographers, so that images of their distant sons can be sent back to family members. This might, for example, explain the numbers of photographers in Foumbot, otherwise a small town close to Foumban.

CONCLUSIONS

I now want to discuss above, where I made gross assumptions about the populations of administrative centers and, on that basis, used population-based calculations to estimate the numbers of photographers operating. The totals seem too high before 1955 but from the period 1955–1995 they are close to those we have seen when either calculating directly from census figures or from other sources. The figures can be improved, since more accurate population figures are available for at least the Divisional centers using national censuses undertaken towards the end of the time-span being considered.

I started this paper with a periodization of short 19th and 20th centuries in Cameroon. I will end by revising this and suggesting what I think is a better division for thinking about the history of photography in this country. This falls between a 90-year period of relatively small-scale Colonial Photography (roughly from 186530 to 1955) and a short thirty-year period of larger-scale Administrative Photography (1955-1985).31 Within the latter lies the so-called Golden Age of the Studios. Along with this periodization goes a choice of methods. In the era of Colonial Photography even up to and immediately after World War II the available data are patchy (at best) and archival records often misleading (recall the health warnings about population figures above). This is best studied by the methods of fairly conventional historiography—using archival sources coupled with field research to track down surviving photographs and the families of early photographers is methodologically appropriate. Although early photography in the few urban centers in the north, such as Garoua, has not yet been studied, most of the activity was a result of international trade through the coast where interactions with Europeans were frequent. However, once we commence the era of Administrative Photography the scale changes and more sociological approaches may be needed. The estimates suggest that during this period the number of photographers active was quite large, and by the 1970s they were distributed across the country, so any concentration of research in the south cannot be justified. The numerical estimates produced for this period can provide some context for any detailed qualitative research, for example on a single studio (e.g. Zeitlyn Citation2015) or the photographers working in a specific area (e.g. Tatsitsa Citation2015).

Finally, I can give some provisional estimates as answers to the questions posed at the start of this paper. How many African commercial photographers worked in Cameroon at various points in time? How many have ever worked? A starting-point for the answers is given in the following tables for each of the newly identified periods ().

Table 11 Number and Cumulative Number of Photographers in the Era of Colonial Photography

Table 12 Number and Cumulative Number of Photographers Active in the Era of Administrative Photography

I said above that the era of Administrative Photography lasted until around 1985, but have extended the estimates for an additional decade. On the basis of the material presented in this paper I think we can estimate that the total number of commercial photographers who had worked in Cameroon up to 1985 is somewhat less than 4,000.

I have included calculations for the following ten years to point to the way that population growth and the continuing expansion of administrative centers drive these estimates, even without taking account of the explosion in itinerant photographers that occurred at this time. Once the administrative driver for photography has gone, the basis of the estimates must be changed, so estimates for photography from 1990 onwards will have to use modified calculations or other methods.

As was said in the introduction to this paper, the figures offered provide a background context for the study of individual photographers, where they give a fairly reliable indication, for example, that a photographer working in 1930 was one of a relatively small number (perhaps 30), but by 1970 the career of an individual photographer would be one in a thousand. The final point of this paper is to reiterate that there is great uncertainty when trying to estimate the numbers of photographers working at any one time, which can make the figures produced a form of guesswork. However, the numbers presented here can at least help anchor and constrain any such speculations. More than that, I hope they will provoke the collection of data about the numbers of photographers working in specific places at known dates, which in turn can provide some anchored datum points with which to continue the discussion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have been greatly helped by the comments and criticism on drafts of this paper from Chris Geary, Jürg Schneider and Tristan Oestermann, Verkijika Fanso, Valentine Nyamdon and Solomon Nsah, as well as by discussion with the late Jacques Toussele and many other photographers in Cameroon. An anonymous reviewer for Visual Anthropology made a stern critique of an earlier draft that has helped sharpen the argument as well as correct some mistakes. I have also had helpful assistance from staff at the Cameroon National Archives, Yaoundé.

NOTES

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David Zeitlyn

David Zeitlyn is Professor of Social Anthropology at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Oxford. He has been working in Cameroon since 1985, and has helped archive the work of the Cameroonian photographer Toussele Jacques with the assistance of the British Library Endangered Archives Programme.

Notes

1 Strictly this should be taken as meaning within the borders of contemporary Cameroon. The only place where it might make a difference is Yola, which was in the German colony of Kamerun but, along with the northern part of Cameroon, under the British mandate, joined Nigeria in 1961. Yola was big enough to have supported a photographer by then.

2 As Werner notes (1996, 88), it actually produced an explosion in itinerant photography (relying on laboratories to develop and print) and the dying-off of the studios. This occurred after the period I am considering and immediately before the advent of digital photography. The itinerant photographers are now entirely digital, taking their memory cards instead of films to the labs for prints.

3 Christraud Geary (Citation2017, 386 fn.2) warns about the essentializing notion of “African photographers” but nonetheless grants the utility of using the idea.

4 One case in point is that of the Moukarim Brothers who came from what is now Lebanon (and were described as Syrien in some early reports); they arrived in Cameroon around 1905. I discuss them and the postcards they produced from their own photographs around 1914 in another paper, and they are not included in the counts in this paper. As far as I can tell the brothers did not act as commercial photographers by taking photographs for third parties. See Malki (Citation2011) for a summary of the history of the Lebanese diaspora and its ambiguous status in many West African countries. Another later parallel case from Mali is that of Abdourahmane Sakaly (1926-1988), born in Saint-Louis, Senegal, to Moroccan parents who ran Studio Sakaly in Bamako from 1956. According to Imperato he is a neglected contemporary of Seidou Keita (Citation2018, 216).

5 That said, some of these photographers apparently may have also worked as commercial photographers from home, outside their formal employment. Such activity does fall within my purview.

6 The start date is determined by when the first commercial photographers were operating, rather than the formal start of colonization.

7 Jürg Schneider notes that this is probably Augustus Washington, who worked as a daguerrotypist in the USA before moving to Liberia in 1853 (Smith Citation2017; Scruggs Citation2010).

8 Note that this is uncertain: there is potential confusion with the Lutterodt’s Duala Studio in Ghana.

9 https://perma.cc/BY6E-J9QM or http://h3-online.heredis.com/fr/ekelekete/genealogie_sawa/individus#15775 (Accessed 4 Aug. 2018). Austen and Djachechi (Citation2014) discuss another branch, the Mandessi Bell family.

10 Museum für Völkerkunde, Hamburg, letters from “Wilhelm M. Bell,” ref. A69. The Frobenius Institute letters have reference LF1706-01_Bell_1897. Another mention is in Alfred Abenhausen’s memoirs from 1907, archived in Berlin (Berlin-Brandenburgisches Wirtschaftsarchiv (BBWA) N 6/22/9 Abenhausen papers). On p. 66 he is described as being a professional photographer living next door to King Bell. I am very grateful to Tristan Oestermann for providing all these references.

11 This indeed is an example that does not fit my definition of commercial photographers, but is such an intriguing and exceptional case that I am including it nonetheless. It would be misleading to exclude it from a discussion of early Cameroonian photography.

12 Various locations have been suggested. It remains possible that various members of the Lutterodt family took photographs in Cameroon as itinerants from the ships linking Fernando Po and Ghana, where they had studios.

13 I am grateful to Jürg Schneider for the name of this photographer. It is uncertain when he started working, but I have erred on the side of inclusiveness and put him in the earlier period.

14 His Citation1994 book The Age of Extremes: A History of the World is on what he calls “the Short Twentieth Century (1914–1991).”

15 Note that the contemporary art photographer Samuel Fosso has worked most of his life in the Central African Republic yet is commonly described as a Cameroonian photographer. If this is the model then Photo Georges should be regarded as Sierra Leonean! It seems most consistent to regard Fosso as Cameroonian/Central African and Goethe as Sierra Leonean/Cameroonian.

16 Note that if this date is correct it is likely he had learnt photography in Sierra Leone (or wherever he had been working prior to arriving in Cameroon).

17 Only more historical work about this period from the key locations such as Douala, Victoria/Limbe, Buea and Yaoundé has any prospect of clarifying how much competition there was during this period.

18 Many thanks to Lynn Schler for her notes on this.

19 Often populations are given only for the administrative subdivisions, not the cities within them. In the case of Douala there was a close coincidence between Wouri subdivision and the city, but this is far less the case with Yaoundé subdivision—clearly shown in some Annual Reports where the population given is for Yaoundé and Saa, e.g. 1931, 1934, 1936 and 1937; reported in Kuczynski (Citation1939, 95, ); so the figures given for 1936 may be 436,194 (ibid., 129), but on page 95 he gives 194,146 for Yaoundé in 1938. I have not used these figures.

20 The licenses (as reported in the Annual Reports) do not distinguish between Cameroonian/African and European photographers. Very few Europeans however were exclusively photographers (exceptions may include Prunet, Pauleau and Fournier). Most were like Guerpillon, traders who would have taken photographs under the auspices of their general commercial licenses and so would not have been reported in the annual statistics as photographers.

21 For an account of the general situation in Douala see Schler (Citation2008), as well as Austen and Derrick Citation1999.

22 Geary reports (pers. comm.) that by 1967 a photographer in Foumban was paying 24,120 CFA for the annual license, which was considered a huge amount, especially when we recall that this was long before the devaluation of the CFA. In today’s money this would be 48,240 CFA (approx. €75).

23 Some of the migrants purchased cameras when they were working on the coast and then became pioneering photographers in the Grassfields.

24 Zeitlyn (Citation2018) discusses the changing numbers of administrative centers of various status in Cameroon. (9-10) gives summary figures for them from 1950. The data from which this table was compiled have been made freely available and can been downloaded from ORA-data via the URL https://doi.org/10.5287/bodleian:j2EBRYqv6. Using these data the table has been extended back in time, to start at 1930.

25 Strictly, photographs were made obligatory on ID cards in French administered Cameroun by Arrêté 599 of 3 Sept. 1953, but this took time to be implemented, so I take 1955 as the key date. From 1961 when British Cameroon became part of the Federal Republic of Cameroon, ID cards with photos became compulsory there too.

26 I had hoped to test the approaches on figures for both Douala and Yaoundé. However, somewhat to my surprise, early population figures are not available for Yaoundé, only for the Department (Division) of which it is the capital; which risks making the population-based estimates misleading (see the discussion above about the unreliability of early population figures).

27 Confusingly, after WWII the term Région was used for Divisional groupings; Zeitlyn (Citation2018, 2-3) discusses shifts in terminology.

28 Cameroon National Archives, Yaoundé (ANY) 11551 b.1 1949 p. 39 and 11551 b.3 1950 p. 61.

29 Also the administrative structure-based estimates may become less reliable in the largest cities, the regional capitals.

30 The start date is determined by when the first commercial photographers were operating, rather than the formal beginning of colonization.

31 The choice of an end date is delicate: 1985 is when commercial photography started to go into decline with the arrival of the mini-labs. It might be more appropriate to extend this as far as 2005, allowing for the explosion in less-skilled itinerant photographers relying on automatic cameras and laboratory printing. This could be explored in another paper.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, Martha G., and Lisa Aronson, eds. 2017. African Photographer J. A. Green: Reimagining the Indigenous and the Colonial. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Anonymous. 1899. Unser Kamerun, Deutschlands älteste Kolonie. Dem deutsche Volke in Wort und Bild gewidmet. Magdeburg, Germany: G. Poetzsch.

- Anonymous. 1938. UK report to League of Nations on the Mandated Territory of Cameroon. London, UK: H.M.S.O.

- Austen, Ralph A., and Jonathan Derrick. 1999. Middlemen of the Cameroons Rivers: The Duala and Their Hinterland, c.1600–c.1960. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Austen, Ralph A., and Yvette Laure Djachechi. 2014. “Rising from, Remembering, and Forgetting Slavery: The Mandessi Bell Family of Douala.” In Douala: histoire et patrimoine, edited by Albert François Dikoumé and Emmanuel Tchumtchoua, 163–82. Yaoundé, Cameroon: Éditions CLÉ.

- Awambeng, Christopher M. 1991. Evolution and Growth of Urban Centres in the North-West Province (Cameroon): Case Studies (Bamenda, Kumbo, Mbengwi, Nkambe, Wum). Berne, Switzerland: Peter Lang.

- Buckley, Liam. 2000/2001. “Self and Accessory in Gambian Studio Photography.” Visual Anthropology Review 16 (2):71–91. doi:10.1525/var.2000.16.2.71.

- Buckley, Liam. 2005. “Objects of Love and Decay: Colonial Photographs in a Postcolonial Archive.” Cultural Anthropology 20 (2):249–70. doi:10.1525/can.2005.20.2.249.

- Derrick, Jonathan. 1978. “Douala under the French Mandate 1916 to 1936.” London, UK: PhD diss., SOAS, University of London.

- Derrick, Jonathan. 1989. “Colonial Élitism in Cameroon: The Case of the Duala in the 1930s.” In Introduction to the History of Cameroon in the 19th and early 20th Century, edited by M.Z. Njeuma, 106–136. London, UK: Macmillan.

- Egloff, René. 2013. “Fotografie in Bamenda: eine ethnographische Untersuchung in einer kamerunischen Stadt.” Basel, Switzerland: PhD diss., Faculty of Humanities, University of Basel.

- Evans, Chloe. 2015. “Portrait Photography in Senegal: Using Local Case Studies from Saint Louis and Podor, 1839–1970.” African Arts 48 (3):28–37. doi:10.1162/AFAR_a_00236.

- Eze, Anne-Marie. 2008. Africa (sub-Saharan). In Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Volume 1 A–I, edited by John Hannavy, 15–18. London, UK: Routledge.

- Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra. 2006. Njoya et le royaume bamoun: les archives de la Société des missions évangéliques de Paris 1917-1937. Paris, France: Karthala Éditions.

- Gbadegesin, Olubukola A. 2014. “‘Photographer Unknown’: Neils Walwin Holm and the (Ir)retrievable Lives of African Photographers.” History of Photography 38 (1):21–39. doi:10.1080/03087298.2013.840073.

- Geary, Christraud M. 1988. Images from Bamum. German Colonial Photography at the Court of King Njoya, Cameroon, West Africa, 1902–1915. Washington, DC: National Museum of African Art.

- Geary, Christraud M. 1996. “Art, Politics and the Transformation of Meaning. Bamum Art in the Twentieth Century.” In African Material Culture, edited by Mary Jo Arnoldi, Christraud M. Geary and Kris L. Hardin, 283–307. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press

- Geary, Christraud M. 2004. “Portraiture, Authorship, and the Inscription of History: Photographic Practice in the Bamum Kingdom, Cameroon (1902–1980).” In Getting Pictures Right. Context and Interpretation, edited by Michael Albrecht, Veit Arlt, Barbara Müller and Jürg Schneider, 141–165. Köln, Germany: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- Geary, Christraud M. 2010. “Through the Lenses of African Photographers: Depicting Foreigners and New Ways of Life, 1870–1950.” In Through African Eyes: The European in African Art, 1500 to Present, edited by Nii O. Quarcoopome, 86–99. Detroit, MI: Detroit Institute of Arts.

- Geary, Christraud M. 2013a. “The Past in the Present: Photographic Portraiture and the Evocation of Multiple Histories in the Bamum Kingdom of Cameroon.” In Portraiture and Photography in Africa (African Expressive Cultures), edited by John Peffer and Elisabeth L. Cameron, 213–252. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Geary, Christraud M. 2013b. “Roots and Routes of African Photographic Practices: From Modern to Vernacular Photography in West and Central Africa (1850–1980).” In A Companion to Modern African Art, edited by Gitti Salami and Monica Blackmun, 74–95. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Geary, Christraud M. 2017. “The Image of the Black in Early African Photography.” In The Image of the Black in African and Asian Art, edited by David Bindman, Suzanne Preston Blier and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., 141–166, 386–91. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Geary, Christraud M. 2018. “An lnnovative Ruler, Missionaries, and the Camera: Visualizing the Bamum Kingdom (Cameroon) in the Evangelischer Heidenbote (1906–1916).” In Menschen – Bilder – eine Welt: Ordnungen von Vielfalt in der Religiosen Publizistik um 1900 (Veroffentlichungen des Instituts für europäische Geschichte, edited by Judith Becker and Katharina Stornig, 34–64. Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck u. Ruprecht.

- Geary, Christraud M., and Adamou N. Njoya 1985. Mandou Yenou: Photographies du pays bamoun, Royaume Ouest Africaine 1902–1915. Munich: Trickster Verlag.

- Gore, Charles. 2013. “Neils Walwin Holm: Radicalising the Image in Lagos Colony, West Africa.” History of Photography 37 (3):283–300. doi:10.1080/03087298.2012.758414.

- Haney, Erin. 2010. Photography and Africa. London, UK: Reaktion Books.

- Haney, Erin. 2013. “Lutterodt Family Studios and the Changing Face of Early Portrait Photographs from the Gold Coast.” In Portraiture and Photography in Africa (African Expressive Cultures), edited by Elizabeth Cameron and John Peffer, 67–101. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Henry, Helga Bender. 1999. Cameroon on a Clear Day. A Pioneer Missionary in Colonial Africa. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library.

- Hobsbawm, Eric J. 1994. Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century 1914–1991. London, UK: Michael Joseph.

- Imperato, Pascal James. 2018. “Celebrating African Photographic Artists: Review of Staples, Edouwaye, Kaplan, and Freyer, (eds). ’Fragile Legacies. The Photographs of Solomon Osagie Alonge’ and Cohen and Paoletti, (eds). ’The Expanded Subject. New Perspectives in Photographic Portraiture from Africa’ “. African Studies Review 61 (3):214–18. doi:10.1017/asr.2018.67.

- Johnston, Harry. 1908. George Grenfell and the Congo: A History and Description of the Congo Independent State and Adjoining Districts of Congoland, Together with Some Account of the Native Peoples and their Languages, the Fauna and Flora, edited by Lawson Forfeitt, Emil Torday et al. London, UK: Hutchinson & Co.

- Kuczynski, Robert R. 1939. The Cameroons and Togoland: A Demographic Study. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

- LeVine, Victor T. 1964. The Cameroons, from Mandate to Independence. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Mainet, Guy. 1985. Douala: croissance et servitudes. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Malki, I.P.X. 2011. “Between Middlemen and Interlopers: History, Diaspora, and Writing on the Lebanese of West Africa.” Diaspora 20 (1):87–116. doi:10.3138/diaspora.20.1.004.

- McKeown, Katie. 2010. “Studio Photo Jacques: A Professional Legacy in Western Cameroon.”’ History of Photography 34 (2):181–192. doi:10.1080/03087290903361506.

- Nash, Johnny. 1972. “There are More Questions than Answers.” From the album, I Can See Clearly Now. London, UK: CBS Music.

- Nimis, Érika. 2013. “Yoruba Studio Photographers in Francophone West Africa.’’ In Portraiture and Photography in Africa (African Expressive Cultures), edited by Elizabeth Cameron and John Peffer. 102–140. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Nja Kwa, Samy. 2004. “La Photographie victime de son image.” Africultures 60:141–145. doi:10.3917/afcul.060.0141.

- Nsah, Solomon Kekeisen. 2017. “The Cameroon Press Photo Archive (CPPA) Buea in Crisis 1955-2016.” Vestiges: Traces of Record 3 (1):65–81. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.6248948.

- Schler, Lynn. 2008. The Strangers of New Bell: Immigration, Public Space and Community in Colonial Douala, Cameroon, 1914–1960. Pretoria, SA: Unisa Press.

- Schneider, Jürg. 2010. “The Topography of the Early History of African Photography.” History of Photography 34 (2):134–146. doi:10.1080/03087290903361498.

- Schneider, Jürg. 2013. ’Portrait Photography: A Visual Currency in the Atlantic Visualscape.” In Portraiture and Photography in Africa (African Expressive Cultures), edited by Elizabeth Cameron and John Peffer, 35–65. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Schneider, Jürg. 2018a. “African Photography in the Atlantic Visualscape Moving Photographers – Circulating Images.” In Global Photographies: Memory – History – Archives, edited by Sissy Helff and Stefanie Michels, 19–38. Bielefeld, Germany: transcript Verlag.

- Schneider, Jürg. 2018b. “Views of Continuity and Change: the Press Photo Archives in Buea, Cameroon.” Visual Studies 33 (1):28–40. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2018.1426224.

- Scruggs, Dalila. 2010. “’The love of liberty has brought us here’: The American Colonization Society and the Imaging of African-American Settlers in Liberia.” Cambridge, MA: PhD diss., History of Art, Harvard University (ProQuest Dissertations Publishing,. 3415287).

- Smith, Charles Spencer. 1895. Glimpses of Africa, West and Southwest Coast: Containing the Author’s Impressions and Observations during a Voyage of Six Thousand Miles from Sierra Leone to St. Paul de Loanda and Return, Including the Rio Del Ray and Cameroons Rivers, and the Congo River, from its Mouth to Matadi. Nashville, TN: A.M.E. Sunday School Union.

- Smith, Shawn Michelle. 2017. “Augustus Washington: Looks to Liberia.” Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art 2017 (41):6–13. doi:10.1215/10757163-4271608.

- Tardits, Claude. 1996. “’Pursue to Attain’: a Royal Religion.” In African Crossroads: Intersections of History and Anthropology in Cameroon, edited by Ian Fowler and David Zeitlyn, 141–64. Oxford, UK: Berghahn.

- Tatsitsa, Jacob. 2015. “Black-and-White Photography in Batcham: From a Golden Age to Decline (1970–1990).” History and Anthropology 26 (4):458–79. doi:10.1080/02757206.2015.1074899.

- Wendl, Tobias. 1999. “Portraits and Scenery in Ghana.” In Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography, edited by Pascal Martin Saint Léon and N’Goné Fall, 142–55. Paris: Revue Noire.

- Wendl, Tobias. 2001. “Entangled Traditions: Photography and the History of Media in Southern Ghana.” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 39:78–101. doi:10.2307/20167524.

- Werner, Jean-François. 1996. Produire des images en Afrique: l’exemple des photographes de studio. Cahiers d’Études Africaines 141–42 (XXXVI 1-2):81-112. doi:10.3406/cea.1996.2002.

- Werner, Jean-François. 1997. “Les tribulations d’un photographe de rue africain.” Autrepart 1 (1):129–150.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2015. “Archiving a Cameroonian Photographic Studio.” In From Dust to Digital: Ten Years of the Endangered Archives, edited by Maja Kominko, 529–44. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2018. “A Summary of Cameroonian Administrative History.” Vestiges: Traces of Record 4:1–13.