Abstract

By using participant-led photography, we examine the complexity in which Black and mixed-race masculinities are imagined and negotiated vis-à-vis interactions and intimate relations with foreign women, in the context of global tourism and transnational intimacies in the South Caribbean littoral of Costa Rica. Photographs were used to reposition local young men, who are often racialized in the tourist imagery, as “takers” of images of their daily lives. We argue that their photographs serve to situate and critically to challenge some of the most common local tourist narratives that portray local men as mujeriegos or “hustlers” who “sponge” off tourist women.

ASSUMPTIONS AND STEREOTYPES

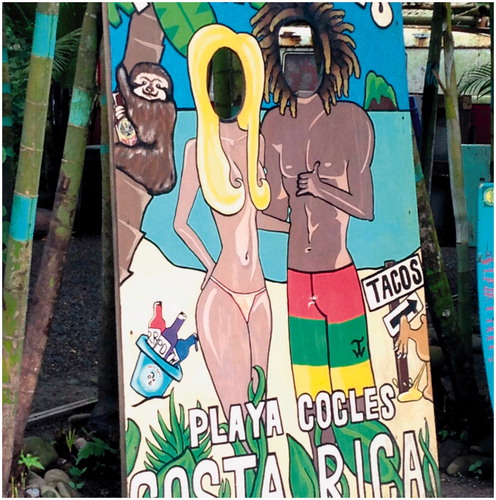

Puerto Viejo de Talamanca, which is also known locally as Puerto and Wolaba, is a small Afro-Caribbean tourism town located in the South Caribbean littoral of Costa Rica, renowned for its stunning beaches, surfing waves, party tourism, and transnational romance and sex.1 On the last evening of my fieldwork in this locale I pushed myself to go out to a popular bar where a “photograph spot” is clearly marked by a life-size cut-out of a blonde white woman and a Black rasta man hugging on the beach ().

Figure 1 “Photograph spot” outside a popular bar in Puerto Viejo. (Photo collection of Susan Frohlick)

While waiting for a beer at the crowded bar I noticed Sahim (a pseudonym), a 30 year-old Afro-Caribbean man dancing and flirting with a blonde woman who was a tourist, not his girlfriend. Two days before, Sahim had participated in my research project and had emphatically declared his love for his German girlfriend. When he had claimed his fidelity and commitment for her at the time of the interview I was convinced. However, at the bar that night as he flirted with another tourist woman, I was not all that surprised really, despite Sahim’s avowal of unswerving loyalty to his girlfriend. After all, my own value judgments as a Costa Rican woman who grew up in San José, the country’s capital and the center of the dominant Costa Rican society that distinguishes itself as white (Christian Citation2013), were influenced by the nationally and globally circulating stereotypes about local Afro-Caribbean men as mujeriegos (womanizers) and/or “hustlers.”

This fieldwork story shows how my assumptions about local Black Afro-Caribbean masculinities held sway over me despite what I had learnt from fieldwork I had done in previous months with seven local men in Puerto Viejo. Most importantly, Sahim’s performances which I witnessed that night revealed some of the widely-known representations of Black Afro-Caribbean and mixed race men in the Caribbean littoral of Costa Rica. Black Caribbean masculinities have been constructed historically around racialized and hetero-sexualized notions of hyper-sexuality and infidelity (Kempadoo Citation2004). More specifically, local Black Afro-Caribbean men are marked by a naturalized proclivity for transactional negotiations of sex for material goods or other benefit, especially related to their positioning in the asymmetrical erotic economy of tourism as “men who sponge off” tourist women (Brennan Citation2004; Cabezas Citation2011; Pruitt and LaFont Citation1995; Frohlick Citation2007, Citation2013a, Citation2013b).

This article examines in more detail the complexity in which Black Afro-Caribbean masculinities were negotiated through interactions and intimate relations with foreign women in a particular tourism setting. Within the transnational party spaces, as well as ecotourism sites and practices like nature hikes, gendered interracial heterosexual relations were played out that were economic in nature, but not straightforwardly so (Frohlick Citation2013b). Men economically maneuvered women through strategies of flirting and sexual advances, rather than by selling sex for cash. The role of visual anthropology was central to the insights gleaned about these complex interactions—through the methodology we used, where men photographed meaningful aspects of their everyday lives from which nuances about them emerged in the research process.2

This article is informed most broadly by fieldwork carried out in Costa Rica by both authors jointly over several years on topics related to tourism and transnational intimacies (Frohlick and Meneses Citation2019). More specifically, the analysis is informed by research that Meneses did in 2016-2017 for a large project on the impacts of tourism on youth growing up in a tourist destination. (The “I” in this article signifies Meneses and her sojourn in the field as a researcher–graduate student, while the “we” is used in order to reflect the collaborative research and shared authorship.)

VISUAL PRACTICES AND TOURIST IMAGES IN WOLABA

As stated by Pink, the use of visual participatory methods demands that the ethnographer be informed of “both local photographic conventions and the personal meanings and both economic and exchange values that photographs might have in any given research context” (Citation2007, 41). In Wolaba, photographs play different roles in the daily lives of local residents and their interactions with tourists. The natural beauty of the landscape makes the South Caribbean littoral the “perfect spot” for the “perfect picture,” according to the prevailing aesthetic standards of the tourism industry, including the “global beach” (Löfgren Citation1999). Surfing photos, too, have become part of the town’s visual culture. Local surfers are aware that a good photograph holds the potential to be translated into sponsorships, presence in national and international surfing magazines, and popularity in the national and international surfing scene.

As well as the scenery of beaches, flora and fauna, and surfing waves, people feature in touristic photography. The vibrant roots-and-relaxed local culture, associated with a racialized difference—that is, the minority Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous minorities—compared with the rest of Costa Rica, has also become a desirable souvenir image—and a form of destination branding which ethnic groups actively promote too (Comaroff and Comaroff Citation2009). This Othering or “tourist gaze,” whereby tourists create difference through the very act of looking (Urry and Larsen Citation2011), caused discomfort and anger for some of Puerto’s townspeople, who refuse to be objectified as a souvenir commodity. In Puerto Viejo, photographs can be an annoying reminder of the politics of ethno-racial representation in the tourism industry, when outsiders have exploited the local community by taking images for profit-making.

The research participants of this project, racialized young men, were acutely aware of the political economy of local images. Because of that awareness they were enthusiastic to participate actively in the production of images about their lives that were generated by them, not by “others.” As we show in this article, the men knew that the photographs taken by local men in this project would have an audience beyond the community; part of their interest in the project was to create and have a say in the visions of their tourism-affected lives that would be put into wider circulation.

Their photographs, suggesting how they felt about their lives and identities as men, portrayed the complex, contradictory ways in which mixed and Black Afro-Caribbean masculinities were understood and negotiated by them, and how manhood and masculinities mattered in their interactions and intimate relations with foreign women. Certainly some of the visuals they produced did re-create aspects of the celebratory tourist imagery reflecting iconographic notions about the local place and people as an intimate, laid-back, ocean-side playscape and cultural tourism destination, images such as a beautiful sunny day at the beach, a man holding a surf board, a group of friends having a good time at the bar, voluminous Afro hair, and a man smoking a joint. These photos are examples of how local men use the more positive symbols and aesthetics related to Black Afro-Caribbean culture, quite possibly to appeal to tourist women’s idealizations of “Caribbean” masculinity and therefore to capitalize on stereotypical features (Anderson Citation2004; Pruitt and La Font Citation1995). A darker, less exalted view of the southern Caribbean region also circulates widely, which frames it as an unsafe “negatively racialized space” that tourists ought to avoid (Christian Citation2013: 1610). Christian argues, “Inhabitants of the southern Atlantic Coast are very aware of the stigma, and in some regards, a sense of ‘danger’ and ‘otherness’ is then reproduced by local actors who use the image as one of the only avenues to lure certain tourists by embodying a distorted version of ‘Rastafarianism’” (idem). As local actors aware of both the draw and the stigma of their region, our interlocutors wrestled with the different stereotypes that plagued them and mediations of them as racialized inhabitants of the marginalized Afro-Costa Rican tourism zone lying beyond the whiteness of the Central Valley (Rivers-Moore Citation2007).

Other photographs, however, such as those presented here, depict different visions, images that are neither the glossy stereotypes of trendy surfers and sanitized rastas, for instance, as shown in tourism media, nor yet the drug and crime-associated imagery used to advertise the dark side of the Caribbean littoral region (Christian Citation2013). Rather than performing the spectacularity of tourism, these are images of quotidian life. Rather than only hyper-masculinity, they convey the blurry edges of domesticity and femininity that touched the men as they carried out their daily routines.

As complex, contradictory imagery, their self-taken photographs held particular meanings for participants; meanings that are central to insights into the complexity of the gender performances and economic negotiations which happened in the town within a context of global tourism and transnational intimacies—insights that challenge not only the widely circulating postcards and travel blogs but also stereotypes that the Costa Rican anthropologist grew up with.

TRANSNATIONAL INTIMACIES

Puerto Viejo is located in one of the country’s poorest provinces, Limón, which exhibits deep racial, social and economic inequalities compared to the rest of Costa Rica, and this is related to its history of settlement by Jamaican labor migrants who worked on the railway and later on banana plantations (Senior Citation2007). Originally inhabited by Indigenous groups and turtle fishers (Palmer Citation1994), Wolaba became a “frontier” town that was greatly influenced by Limón’s labor conditions and, in particular, by the racial conflicts experienced by Black immigrants during the late 19th century. Those conflicts were related to the way in which the Black population did not fit within the liberal imaginary of Costa Rica as a “white nation” (Senior Citation2007). Over the years this exclusion has led to high levels of poverty, crime and violence as well as low levels of literacy among residents of Puerto Viejo and the rest of the province.

In contrast to large-scale tourism on the Pacific, the Caribbean coast has favored smaller-scale, independently operated tourism entities. Over the years this type of touristic development has become the region’s greatest strength, attracting tourists who are interested in experiencing close, intimate connections with nature and with local cultures (Frohlick Citation2007, Citation2013b), but it has also been a detriment due to its construction as both rustic and dangerous. Free of massive resorts, the South Caribbean littoral region in particular generates a type of anti-materialist tourist interested in a “roots-local” vibe, associated with the historical presence of the BriBri and Cabécar Indigenous cultures and the Jamaican Afro-Caribbean culture in the area, including its music, food and architecture (Frohlick Citation2013b). In recent decades the region has also experienced an increase in its resident foreigner population, including Costa Ricans from other provinces, Panamanians, Nicaraguans, as well as “expats” mostly from North America and Europe. In short, Puerto Viejo’s sociocultural landscape has transformed from one “hybrid mix” to another (Frohlick Citation2007, 147), where different ethnicities, realities and scenarios have converged.

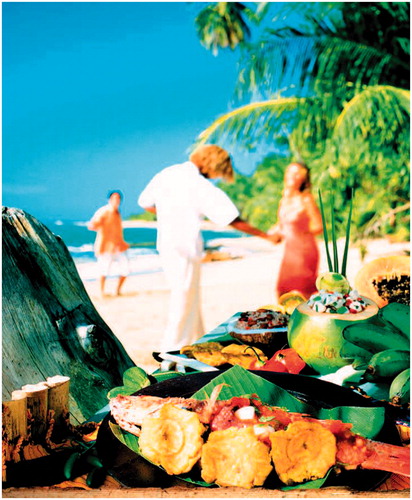

Despite this plurality, Blackness plays a central role in the town’s social organization. “Black” is used both to justify racism against “non-white” populations and as a marketing strategy in the national and global tourism market (Christian Citation2013). “Blackness” is a central category to understand Puerto Viejo’s touristic development, a category strongly influenced by the imaginaries created transnationally about “the Caribbean” and its populations (Anderson Citation2004). In this sense “the Caribbean” is pictured and marketed by several social actors as “one place” (ibid.), with a “simple and relaxed atmosphere” (Frohlick Citation2013b), inhabited by “vibrant, exotic, and laidback” local populations. These imaginaries shape the perception that foreigners have about what to expect of their vacations in “the Caribbean.” Therefore, the imaginaries also dictate the experiences that local inhabitants are supposed to provide, as a kind of expected hospitality in these transnational encounters. For example, illustrates how the Costa Rican Tourism Board (ICT) promoted one such imaginary of the Southern Caribbean littoral in a multi-million dollar international media campaign launched several years ago, called “No Artificial Ingredients.” In this poster the “promised scenario” is offered to tourists, promising them experiences specific to this region: blue waters, palm trees, Caribbean food and, mirroring the image of the cut-out in front of the bar in Puerto, a dark-skinned dreadlocked man and a blonde woman dancing on the beach, with the shape of a male tourist hovering behind the woman tourist, suggesting perhaps a watchful husband.

Figure 2 Photograph used by the Costa Rican Tourism Board as part of a publicity campaign called “No Artificial Ingredients” to promote the South Caribbean region of Costa Rica. (Photo collection of Susan Frohlick)

The rasta image no longer sells so well but Blackness continues to be a powerful marker of exotic masculinity in this region. As Maksymowicz (Citation2010) has argued, local masculinities are multiple and heterogeneous. However, “Blackness” came to be a central constituent of local men’s performances and gendered subjectivities, and it links Caribbean heterosexual masculinities in the region with economic predation within the contact zones of encounters. Representations about the “predatory nature” of Costa Rican–Caribbean men are closely related to colonial imaginaries about “Black-non-white people.” As argued by Lewis (Citation2003), in Western societies Black bodies have been associated with passion and the inability to control emotions. Specifically, male Black bodies are also associated with highly valued ideals of hegemonic masculinity, such as hypersexuality, strength and power (Kempadoo Citation2004; Pruitt and La Font Citation1995; Sheller Citation2003). As shown in , many social actors involved in the tourism industry capitalize on those imaginaries, not only bar owners and tourism boards but also, as we demonstrate, local men who often hold less economic and social capital than the tourist women they transact with. Young men’s positions in the hierarchy of heterogeneous masculinity in town do not depend entirely on ideals of hegemonic masculinity such as “men as economic providers” (Maksymowicz Citation2010). Social capital is gained through gendered performances of local Black masculinity that seem to deftly incorporate tourists' idealizations of the cultural difference coded onto the landscape, which includes desires for intimacy with locals (Frohlick Citation2007).

Local men are situated not only in regional visual imaginaries but also in wider constructions of the Caribbean and its populations that have triggered the market for sexual work and other sexual-economic exchanges between locals and tourists (Sheller Citation2003; Pruitt and La Font Citation1995), which include transnational intimacies (Cabezas Citation2011; Frohlick Citation2007, Citation2013a). These intimacies, which are transnational because of the patterns of mobility and flows of capital and people involved, can be seen as “social relationships that are—or give the impression of being—physically and/or emotionally close, personal, sexually intimate, private, caring or loving” (Constable Citation2009, 50). The burgeoning scholarship of transnational intimacies demonstrates how the relationships forged between locals and tourists often involve complex forms of “commodified intimacies” or “intimate labor,” in which intimacy intertwines with money and material goods (Constable Citation2009; Cabezas Citation2011; Borris and Parreñas Citation2010; Frohlick Citation2007, Citation2013b).

The anthropology of tourism has long been interested in encounters. The power dynamics and histories of colonialism that shape flows of Western tourists to “Third World” developing countries, and their quests for hospitality and “the exotic, the erotic, the happy savage” in the ever-shifting touristic border-zones have been affected by globalization and late modernity (Bruner Citation2005, 191). The anthropological lens has focused on the transactional underpinnings of romantic and sexual encounters in the Caribbean “hot spots” (Pruitt and La Font 1992; Brennan Citation2004; Frohlick Citation2007, Citation2013a). While this body of scholarship has brought nuance to the issue of exploitation and agency within erotic border-zones, narrative methodologies have predominated. Visual methodologies have potential to elucidate complexities in people’s lives, as Rose (Citation2016, 316) posits, “participant-generated visual materials are particularly helpful in exploring everyday, taken-for-granted things in their research participants' lives.”

We turned to photography as a research tool, especially because of its potential to meaningfully and creatively engage youth in research and because photos held salience for Wolaba’s local men.3 The photos they took not only facilitated the telling of stories about their everyday lives, but also served to situate and challenge some of the most common narratives regarding the scandalous intimate encounters and “fluid exchanges” in this locale between local young men and foreign women (Frohlick Citation2007). This methodology brought forward ethnographic details that question the well-trafficked stereotypes and assumptions about the alleged “predatory nature” of Caribbean–Costa Rican men, who “hustle” tourists. The term “negotiated intimacies” captures the dynamic, intertwined role of economics and intimacy in the men’s relationships and interactions with these women from Europe, North America and Australasia.

The photographs complicate the Janus-faced representations about Caribbean–Costa Rican men in two main ways (dangerous, on the one hand, but desirable, on the other). First, they allow us to “see” how local youth negotiate their gendered subjectivities through material–erotic interactions and exchanges. Masculinity in this sense is not a ready-made image but one that is produced by the men as social actors. Secondly, because the photographs were taken by local men and not by other visual producers of them, this allowed participants the chance to reflect on and make visible aspects of their lives that mattered to them. Rose comments on the role of participant-generated images to empower research participants as “experts” when they explain the images to the researcher (idem.). Including the participants in the research process this way was an aim in our method, and allowed the men to reflect on both the politics and the pleasure of self-representation.

PARTICIPANT-LED PHOTOGRAPHY

We now explore the possibilities of participant-led photography for illuminating how young men involved in negotiated intimacies positioned themselves and saw themselves being positioned in their ordinary daily lives. Our approach was similar to that of Robertson et al. (Citation2016: 35), who worked with refugee youths in Australia using photos taken by youths in places of post-settlement in Melbourne, as a way to shift the predominant focus on stereotypes of “refugee” to reposition “the refugee subject as the taker of the image.” Robertson et al. (Citation2016) used a method that fostered the means by which the youths made their worlds visible and therefore provided alternative ways to examine how such youths understand settlement from their own view, literally. The act of going out to take photographs, Robertson et al. (ibid.: 35) suggest, “involved a reorientation whereby the refugee youth position themselves in relation to the social and material world of settlement in Australia.” We used participant-led photography with a similar approach, to reposition Black Afro-Caribbean and mixed race men as “takers” of images about their lives. The set of images taken by participants served to tell particular visual narratives, supplemented by oral narratives, about their social and material everyday worlds as they saw and chose to frame them.

Here we highlight four photographs that are part of a larger research project focusing on how local men performed and negotiated their self-understandings about masculinity and fatherhood in the context of global tourism and consequent transnational intimacies (Meneses Citation2017). The larger project used a youth-centered methodology. It included seven men from 18 to 35 years old who had diverse mixed-race identities, including men who identified as Black, Mulato (mixed Black and “white”), Mestizo (mixed “white” and Indigenous) or Culí (mixed Black and Indigenous).4 The men had various occupations, such as tourist guides, professional surfers, business owners, and kitchen workers, but all were directly or indirectly related to the town’s tourist activity. With the exception of Sahim, the rest of the participants—Kerlin, Félix, Carlos, Pablo, Edwin and William—chose to disclose their actual names in reports and write-ups of the research as a claim to showing, in Kerlin’s words, “pride and self-respect.” (Following a principle of youth-centered methodology that is guided by the agency of the participants, we respect their decision and use their actual names in this article, recognizing that the risks of doing so cannot be fully known in advance.5)

We knew that the technical devices would be appealing and familiar for the youths. Nowadays, the everyday ordinariness of mobile phones helps anthropologists interested in “capturing” or accessing everyday lives (Delgado Citation2015). We used the ordinariness of mobile-phone photography to get at the ordinariness of the encounters. Our participants were asked to take seven pictures, using their own cellphones, which visualized their lives as young men who live in Puerto Viejo. While the initial idea was to have them take photographs on their own, once in the field the first participant, Kerlin, suggested that the researcher (Meneses) be present during the photo-taking sessions. For him the appeal of the research process lay in its sociality. His insights ultimately enhanced the research process. By being present Meneses was able to gain access to spaces that were integral to getting a better understanding of the social and relational context of their photographs in their lives. Being with the researcher while making decisions about the content of the photos also offered participants the opportunity to reflect aloud about the meanings they were giving to the subject matter.

After the photos were taken, open-ended interviews were conducted with the men individually, to learn more about the meanings and significance of their images. Sometimes the participants referred directly as to why they chose a particular image over other ones, or explained the meanings they tried to represent in their photos. On other occasions they used the pictures as a reference to tell an anecdote or a story about their childhood, their experiences with tourism, foreign women, or some other of their daily life experiences.

In this article we focus on a particular theme recurrent in many of the photographs taken—the economically transactional-inflected gender negotiations occurring in the context of cross-border erotics and global tourism. Based on a combination of the participants’ own preference or ranking of favorite photographs, ethical considerations (i.e. some of the photographs taken present privacy issues vis-à-vis third parties such as girlfriends), and our own interest in ethnographically highlighting a cross-section of images from the larger collection of 49 photos in total, we have selected four of them taken by four participants to present and analyze here. In the following four sections a particular photograph and participant are featured to convey a partial account of the stories these photos tell of the men’s everyday lives and some important elements of their negotiated intimacies with foreign tourist women.

MONEY

Kerlin is a 34-year old Indigenous-Black local tourist guide. Though born in Limón city, since he was a child he used to visit his dad in Puerto, where he has been living intermittently since his youth. Kerlin moved to the capital in his early twenties, but after some years decided to return to Puerto looking, in his words, “for freedom.” “Puerto’s freedom” allowed him to finally grow his Afro hair, which according to him “has been a success with women because it goes very well with my skin tone. Not too dark, not too ‘white,’ just chocolate.” He took a photo showing a wallet, sunglasses, and refreshments on a beachfront bar with surfboards looming large in the background. It also () features an icy-cold tropical-watermelon drink in a tall glass with a bottle of a beer awaiting Kerlin to indulge himself on a sunny afternoon by the seaside. For him the sunglasses signal recreation, and the woman’s wallet placed off to the side of the café table represents the complex economic dynamics in his interactions with tourist women, and his economically disadvantageous position in such encounters.

Figure 3 Photo taken by Kerlin at Noa, a seaside bar located in Wolaba. (Reproduced by permission of the participant; photo collection of Carolina Meneses)

As a local man situated both as Indigenous and Black (which he describes as having a “chocolate skin tone”), Kerlin navigated the economic asymmetries in transnational encounters and the hegemonic notion of men as economic providers in particular ways. In explaining why he took this picture he referred to a time when he used to work as a bartender and was allowed to invite tourist women for a drink. For Kerlin, “having control over the alcohol gave me some advantages over the other guys to meet women,” but he used this advantage discriminatingly: “This doesn’t mean that I was always inviting them, just when I felt like,” he said.

These situations nevertheless had been “advantageous” to Kerlin because he was able to “provide” drinks for people, to make new friendships without having to spend his own money. However, sometimes foreign women did expect him to pay for their bar and/or restaurant bills, especially when they shift from being a tourist to a temporary resident, which he conveyed in this story:

One time I met a super good-looking Swedish girl. We just started to chat for a bit on the street, and she asked me out a couple of times, so I finally agreed… She wanted us to go for some Italian food, and she picked [out] the most expensive restaurant… when the bill arrived she wanted me to pay, and I was like no way, I don’t have to… she got so offended and mad at me… can you believe it? After that night, I tried to explain to her that I couldn’t afford it, and even tried to see her again, but she doesn’t say hi to me anymore. Her loss, this is who am I.

Kerlin’s anecdote challenges prevalent notions about the regularity in which foreign women “always” pay. In this story a white European woman demonstrating a middle-class taste for fine food, who had sufficient resources to relocate temporarily to Costa Rica and live in Puerto, had positioned Kerlin as a “local guy” who would, unquestionably in her eyes, be the one to pay the tab, presumably assuming the dinner constituted a “first date.” Despite the woman's expectations, he refused to pay, exerting self-knowledge about “who he is.”

WORKPLACE

Félix is a 24 year-old man who was born in Limón city and identifies himself as “a non-Black Caribbean man.” He has grown up as part of the local Afro-Caribbean culture, but has his roots in the Nicaraguan culture where all his family came from. His mother and uncles emigrated from that neighboring country many years ago and bought the land on which he is slowly building his house with the money he earns at work. Félix asked me to take this photograph of him () inside a popular restaurant. The image shows him from the back looking at his workspace, the bar. There are many such restaurants in Puerto, and this one has the typical outdoor feel to it and the simplicity of one long counter decorated with mosaic tiles along with a good number of wooden stools that would fill with customers as the evening unfolded. Félix, too, is dressed in typical attire for local men and tourist men alike, wearing a baseball cap backwards, a dark tee-shirt, surfing shorts that fall below his knees, and rubber flip-flop sandals.

Figure 4 Photo taken by Félix at the bar where he worked at the time. (Reproduced by permission of the participant; photo collection of Carolina Meneses)

Figure 5 Photo taken by William of the house he rented with his foreign girlfriend. (Reproduced by permission of the participant; photo collection of Carolina Meneses)

The photograph underscores the centrality of this particular space in his understandings about masculinity, a place he describes as his “center of operations.” For him, being a bartender was a central constituent of his identity as a local man. His employment was a source of a stable income, but was also a space where he made connections with tourists for his fishing tours, practised English, had fun and a chance to party, and has the possibility to meet tourist women—which at that moment of his life was “important” for him. As he told me, more than the potential access to economic capital (“I don’t need the women’s money, I have mine that I earn by working hard,” he said) it is the “fun” that these sexual-romantic encounters represented what caused him to quit his old job as a waiter and become a bartender. According to him, he likes “to be where the party is, and be part of the party.”

Félix had recently broken up with a European woman with whom he had had a lengthy relationship and a child. His preference at that moment for brief intimate encounters with tourists suited his current desire for freedom. In his telling of his story in relation to the photo, he had repressed his desire for freedom while in a long-term relationship. Ultimately the repression of freedom he felt had caused his relationship to end. In his words, “even though I tried hard, long-term relationships are not for us [making reference to local Caribbean men]; they are not suitable to Puerto’s lifestyle.”

While explaining the reasons why he chose this picture Félix commented on what he considered “the biggest difference” between local women and tourist women. In his opinion, local women expected local men to commit to a monogamous relationship. As he explained it, even if local women know “who you are and the things you do… they still want a long-term committed relationship.” On the other hand, foreign women from Western countries “just come here to visit: they know they are here to party and then they leave, and you never see them again.” He did not seem to recognize the irony in this binary opposition he had painted between local and tourist women, given that he had been in a long-term monogamous relationship with a European, not a local, woman. We interpret this irony in part to reflect the sadness he felt over the break-up and also, in part, to reflect a common stereotype in Puerto about racialized femininities which tend to be homogeneous despite a vast diversity of cultural, racial, sexual, economic, national and other differences across women.

In Félix’s opinion, in addition to parties and potential casual or recreational sex with tourist women, “Puerto’s lifestyle” provided local men with another type of capital. It was the capital inherent to recreation and leisure, a value shared by tourists. In his words, “Puerto gives us a more relaxed and fulfilling life than the one that most foreigners have in their home countries, because you can enjoy riding your bike and going to the ocean every day.” He capitalized on these stereotypical representations of “the Caribbean” and its inhabitants, and pictured himself as a “facilitator of cultural (and also sexual) experiences” who could guide tourist women in their own exciting journeys in Puerto. At the same time it is interesting that this photo does not include components of the “global beach” or typical Caribbean aesthetics seen in postcards and tourism media. Instead vernacular elements, such as the mosaic, are important clues to the zonal Caribbean vibe of Puerto that, in his authority as a bona fide local, he wanted to capture. Neither does the photo position Félix as a worker at the bar where he was employed. Instead the image effectively places him as a consumer of touristic pleasure on the customers’ side of the counter while at the same time exuding an intimacy reflecting his insider status in that space. Félix established a complex subjectivity through this image, intended to depict his love of freedom from monogamy and his interest in meeting tourist women in order to sell them an array of services which involved his pleasure-seeking as much as theirs.

HOME

William is a 25 year-old Black Afro-Caribbean man, who like Kerlin and Félix was born in Limón city, where he lived until he was 18 years old and decided to move to Puerto. While growing up he used to travel to Puerto to visit relatives who had relocated in the South Caribbean littoral region looking for better job opportunities, and he decided to also “give it a try.” However, as our conversation unfolded William told me about his job situation at that point: he remained unemployed. Although he used to work as a kitchen helper in a restaurant in the area he had recently lost that job. According to him the new owners of the place, a foreign couple, did not respect Costa Rica’s labor regulations, and he got tired of them. His foreign girlfriend supported his decision to quit the job.

William decided to take this photograph of the entrance to the house he shares with his girlfriend (), as a means to “make visible” the recent paint job he had given the place. It is hardly a typical Caribbean touristic scene. Rather, the broom at the bottom of the wooden stairs leading to the apartment and the bright red wooden privacy wall with a tall plant growing near the yellow cement landing present a vision of domesticity and, we might add, a sense of achievement in maintaining a proper home. Indubitably, William aimed to feature the newly painted exterior in this photo. The lack of cash flow due to his unemployment meant that masculinity was bound up in other means of material contribution within the relationship he had with his girlfriend. With this photo he was able to express this material contribution because, for him, “being a man” was related to the capacity to pay the household bills. In his words, “As a man you have a responsibility to pay some of the month’s bills… Just because I lost my job I am not going to stay in the house sleeping… waiting for my woman to come and give me money… I need to keep moving.”

Due to his unemployment he felt he had to find informal ways to make money and also be productive in the household, for example by making sure that the house is clean and the food is ready for his girlfriend when she comes back from work. In this sense, in the absence of a regular income to pay the household expenses, William found different ways to enact or negotiate his masculinity, such as by painting the whole house and rebuilding the garden, by which he had made a major (and manly) contribution to their division of labor. Such enactments of “men’s work” seemed to compensate for not having a cash flow that would have put him, in his eyes, on a more equal footing with his girlfriend. William felt he had less economic power than she, which garnered her power to make all kinds of decisions related to his everyday life. In his words, “she is the boss of the house when it comes to making decisions because she is the one who works.” This association of power with economic income meant, for example, that when he was unemployed he felt he needed to ask for her “approval” to go out and party with his friends. Sometimes it meant that he didn’t go out. As he explained, “If she is feeling sick, or you know, I know her, if I tell her, babe, I’m going out, and I see she is not happy about it, then I just prefer to stay here, just to avoid fights.”

However, although William indicated in the interview that the compromise was palatable for him, the power imbalance was not ideal and it led to feelings of discomfort. He felt ashamed and “less manly” than he aspired. Not having a job was tortuous to him because of the inequity created and the damage to his self-esteem. He explained, “Lots of men here love women to pay for their things, but I don’t… I prefer when things are more equal, because if she is the only one paying, I feel smaller than her.”

William had tried to portray in this photograph how having less economic power than his girlfriend was tied to his masculine subjectivity. He felt “less manly.” The newly painted walls on their shared house served as a gendered strategy of negotiation, where the participant’s understandings about masculinity and his position in relation to the foreign girlfriend were reconfigured in the domestic labor he had willingly performed. When he took the photograph, that choice of producing an image was also a deliberate strategy to make his unpaid work in the domestic sphere visible to the outside world. William tried to recuperate some of the power and pride he had lost since quitting his restaurant job, an act of recuperation that was exhibited not only in the housework itself but also in the representational and identity work of photography. He did not want to appear to anyone as a man who sponges off women, as he had so clearly and deliberately stated in his opposition to the men around him who let women pay for things, including their food and housing. Not William.

NIGHTCLUB-BAR

We return now to Sahim, who had moved from Panamá (where he used to live with his father) when he was 14 years-old to live with his mother. He described a night in this bar () as the beginning of what he called a “life-changing experience.” During our conversation about the reasons for taking this picture Sahim explained that it was at this location where he met his German girlfriend. The photograph, taken from a distance, was of a popular nightclub-bar at night when the lights inside imbued the place with a soft inviting light. The name of the bar, The Lazy Mon, is clearly visible on a large sign above the entrance. A couple of bikes are parked outside and two men are sitting and standing inside, apparently customers buying beer at the start of a night that promises to be hopping with business.

Figure 6 Photo taken by Sahim of a regular hang-out spot in town where he met his German girlfriend. (Reproduced by permission of the participant; photo collection of Carolina Meneseses

During our time together Sahim insisted on how special the couple's relationship was, assuring me that at the beginning this connection was not mediated by sex but by a “deep understanding of each other, even though we were from different cultures.” Apart from these cultural differences, it did not take Sahim too long to realize that he and his girlfriend also had different financial situations. In his words, while he “struggled almost every month to find a job in construction or as a kitchen assistant” his girlfriend, who was also “struggling financially in her country because she is not rich either,” was able to come and visit him every six months. She was even capable of paying Sahim’s expenses to visit her. Details about his experiences as a Black Afro-Caribbean man away from Puerto unfolded during our conversation about how the photograph renders visible what the participant considered a “life-changing experience”: his recent travel to Germany.

One day we were just talking and I told her: mi amor, one of these days I will go and visit you in Germany, you’ll see. She looked at me and she asked, do you really want to go? I said yes… six months later she called from Germany and told me: mi amor, I already have your ticket. Then she sent me my ticket and everything else I needed. And just like that I left Puerto.

According to him, his worldview changed radically as a result of the two months he spent in Europe. He learnt about other cultures and had the chance to open his mind to new ways of living; he was also able to experience “what it really means to have money.” With a lower financial status than his girlfriend, her family and her friends, Sahim repeatedly felt demeaned during his travel. In his words, “I got intimidated by their living standards. When they told me, go, drive this Mercedes Benz … or by the stupid amounts of money they spend in hotels and meals. Like paying four hundred euros for a six-person dinner. That’s something that obviously I couldn’t afford.”

However, as Sahim’s participant-led photography and interviews led us to see, these sorts of disadvantage which he became hyper-aware of while in Germany did not overdetermine his perception of transnational travel. Instead they represented “lifetime opportunities.” He interpreted his girlfriend’s gift of the fully paid trip as a generous surprise. While some of his friends might consider such a gift from a woman a threat to their masculinity, Sahim did not, interpreting her paying for everything as “support.” In his words, it was “the normal thing you do when you love someone and have the economic means to do it.” Sahim’s understandings about what “support” entails capture the dynamic, intertwined role of economics and intimacy in his relationship with a European woman whose socio-economic class background was markedly different from his.

The photograph of the nightclub-bar both challenges and upholds stereotypes of Black Caribbean–Costa Rican men and masculinity, and also tells a much more complex story than an overly simplistic one of opportunism or hustling. It is a fascinating statement of the centrality of spaces of encounter within the uneven mobilities of wealthy and poor tourists. Without the nightclub-bar Sahim would not have met the European girlfriend who changed his life and transformed him into a tourist, and yet the palpable sting of geopolitical economic disparities and racism was also “afforded” because of this encounter. He was not exactly sponging from a woman he had met in this place, but at the same time he was not aware of European prices for food and travel. Lazy Mon was a site where many of these contradictions came to light and, like many young world travelers, he had to grapple with his identity in new and challenging ways. Furthermore, as the story in the introduction indicates, the nightclub-bar was a locus of possibility, of meeting “the next” foreign tourist woman and the unknown opportunities she might bring into his small-town littoral life.

CONCLUSION

A year after fieldwork I went back to Wolaba and happened to find Sahim at the same bar where last we had met. He had broken up with his German girlfriend a few months before, and was still heart-broken; but, he asserted, “life must go on.” I made reference to the episode with another foreign woman I had seen on my fieldwork’s last night.

He smiled, asking, “Come on, did you see me kissing her?” “No,” I answered. Sahim replied sarcastically, “So, I’m innocent. Probably I was just goofing around ’cause there’s something nice about knowing that all these beautiful women want you [Sahim pointed to a blonde woman who was dancing], even though I’m ugly and broke.”

Dominant narratives and colonial imaginaries situate Puerto Viejo’s Black and mixed-race Costa Rican–Caribbean men as always trying to hustle or take advantage of foreign women tourists. However, with the exception of a few local men who clearly identify themselves as “gigolos” (none of our research participants did), this categorization, we argue, limits the anthropological understanding of the historic, social and cultural dynamics that converge and shape the diverse intimate encounters happening in Wolaba and ultimately in local men’s lives.

The participants’ experiences and attempts to commit to long-term relationships with European women not only call into question stereotypes about the transience of such intimate encounters, but also allow a detailed examination of the complex and sometimes contradictory ways whereby Puerto’s local men imagined and negotiated their masculinities through interactions and intimate relations with foreign women in the context of global tourism.

Using participant-led photography, participants took photos of various places and settings in the town that included bars and dwelling spaces, with cellphones that were technologies familiar to them, and also with an acute awareness of the politics of photographic imagery in which local men in the Caribbean region of Costa Rica were regularly positioned as exotic and erotic. The visual material generated by the participants, in dialogue with the anthropologists, depicts what it meant for them to “be a local man.” It also allows us to “see” the town in the men’s eyes and their understandings of the local social dynamics, especially their understandings of how economic and non-economic negotiations were happening in the intimate encounters between them and foreign women.

On one hand, Kerlin, Félix, William and Sahim see themselves as “doing their part” and contributing with economic and non-monetary capital in these relationships. In some cases the kind of support that local men provide is monetary or within the economic domain: they paid for restaurant bills, provided accommodation or long-term housing, and took their foreign girlfriends on fishing tours—all activities for which tourists would normally have to pay.

On the other hand though, the participants also relied on stereotypical representations of Black Afro–Caribbean masculinity and sexuality to assert their masculinity and also to reverse their disadvantageous positions; for example, “by facilitating unforgettable cultural and sexual experiences” or “cooking Caribbean food for the girlfriend’s acquaintances in Germany.” On other occasions the men’s contributions entailed the negotiation of their understandings about hegemonic masculinity, by performing domestic labor, for example, which they considered “feminine” or approximating passivity.

Our first two images ()—the cut-out of the tourist woman and local man and the Tourism Board poster for the South Caribbean littoral featuring a dreadlocked local man with a tourist woman—are examples of the kind of visual material produced within local and global tourism economies, material that is highly visible throughout the locality. They represent the kind of imagery about local Black Afro-Caribbean men as hustlers and players that was readily consumed by tourists and used by local businesses as well as by our interlocutors to capitalize on the desirable or at least normalized racialized and stereotypical representations about Puerto and its inhabitants. Counter to this, the four participants’ photos were taken by local men, and provide a sampling of the ways that local men viewed the town through their eyes rather than through touristic images of them, and ultimately how the men repositioned themselves beyond “the hustler” image, both in terms of mirroring and of challenging some of those representations.

NOTES

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Carolina Meneses

Carolina Meneses is a Costa Rican researcher who holds a MA in Anthropology from the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg. She currently works as a research assistant with Susan Frohlick at the University of British Columbia in a research project called “Afro-Costa Rican Young People and Global Tourism: Transforming Youth and Imagining Life Projects through Intimate Exchange Relations with Tourists.”

Susan Frohlick

Susan Frohlick is a Professor of Anthropology and Gender and Women’s Studies, and the Department Head of Community, Culture, and Global Studies at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan.

Notes

1 We use the names Puerto Viejo, Puerto, and Wolaba interchangeably, as these are the ways in which people refer to the town. Puerto Viejo means Old Harbor, and often in daily usage is shortened to Puerto. The official name of Puerto Viejo de Talamanca is rarely used. Local people also use Wolaba, the equivalent of Old Harbour in creole (or patua). Creole is an English-mixed slang commonly used by Afro-Costa Ricans. It was developed and adapted by Black populations during slavery times and the colonial period (Senior Citation2007).

2 The “we” in this article is Carolina, a graduate student and research assistant, and Susan, a university professor and researcher who supervised the project. When “I” is used, this refers to Carolina while she was in the field, as she carried out the fieldwork with these men.

3 We use the category “youth” very loosely to indicate young adults, rather than as a demographic term that delineates specific ages.

4 Even though Culí or Coolie is a term used to define the racial identity of immigrants from India, China and other Asian countries who worked in European colonies and in America, in this article we used one of the term’s local understandings: a mix of Indigenous and Black ancestry.

5 In order to prevent the disclosure of sensitive information that might represent any potential conflict for the participants or affect the privacy of third parties, some topics such as infidelities are not directly associated through this article with any real names.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, Moji. 2004. “Arguing Over the ‘Caribbean’: Tourism on Costa Rica’s Coast.” Caribbean Quarterly 51 (2):1–18. doi: 10.1080/00086495.2004.11672239.

- Boris, Eileen, and Rachel Parreñas, eds. 2010. Intimate Labors. Cultures, Technologies and the Politics of Care. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Brennan, Denise. 2004. What’s Love Got to Do with It? Transnational Desires and Sex Tourism in the Dominican Republic. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bruner, Edward. 2005. Culture on Tour. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Cabezas, Amalia. 2011. “Intimate Encounters: Affective Economies in Cuba and the Dominican Republic.” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 91:3–14.

- Christian, Michelle. 2013. “Latin America without the Downside: Racial Exceptionalism and Global Tourism in Costa Rica.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (10):1599–1618. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2013.788199.

- Comaroff, John, and Jean Comaroff. 2009. Ethnicity, Inc. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Constable, Nicole. 2009. “The Commodification of Intimacy: Marriage, Sex, and Reproductive Labor.” Annual Review of Anthropology 38:49–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.37.081407.085133.

- Delgado, Melvin. 2015. Urban Youth and Photovoice: Visual Ethnography in Action. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Frohlick, Susan. 2007. “Fluid Exchanges: The Negotiation of Intimacy between Tourist Women and Local Men in a Transnational Town in Caribbean Costa Rica.” City and Society 19 (1):139–68. doi: 10.1525/city.2007.19.1.139.

- Frohlick, Susan. 2013a. Women, Sexuality, Tourism: Cross Border Desires through Contemporary Travel. London, UK: Routledge.

- Frohlick, Susan. 2013b. “Intimate Tourism Markets: Money, Gender, and the Complexity of Erotic Exchange in a Costa Rican Caribbean Town.” Anthropological Quarterly 86 (1): 133–62. doi: 10.1353/anq.2013.0000.

- Frohlick, Susan, and Carolina Meneses. 2019. “Emergent Collaborations: Field Assistants, Voice, and Multilingualism.” In Learning and Using Languages in Ethnographic Fieldwork, edited by Robert Gibb, Annabel Tremlett, and Julien Danero Iglesias, 31–43. Bristol, UK: Channel View Publications.

- Kempadoo, Kamala. 2004. Sexing the Caribbean: Gender, Race, and Sexual Labor. New York: Routledge.

- Lewis, Linden. 2003. “Introduction.” In The Culture of Gender and Sexuality in the Caribbean, edited by Lewis Linden, 1–25. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

- Löfgren, Orvar. 1999. On Holiday: A History of Vacationing. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Maksymowicz, Kristofer. 2010. “Masculinities and Intimacies: Performance and Negotiation in a Transnational Tourist Town in Caribbean Costa Rica.” Winnipeg, Canada: MA dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Manitoba.

- Meneses, Carolina. 2017. “Local Masculinities beyond Images: Youth, Fatherhood, and Tourism in the South Caribbean of Costa Rica.” Winnipeg, Canada: MA dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Manitoba.

- Palmer, Paula. 1994. Wappin Man. La Historia de la Costa Talamanqueña de Costa Rica, según sus Protagonistas [What Happen. A Folk-History of Costa Rica’s Talamanca Coast]. San Jose, Costa Rica: Ed. de la Universidad de Costa Rica.

- Pink, Sarah. 2007. Doing Visual Ethnography. London, UK: Sage.

- Pruitt, Deborah, and Suzanne La Font. 1995. “For Love and Money: Romance Tourism in Jamaica.” Annals of Tourism Research 22 (2):422–40. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(94)00084-0.

- Rivers-Moore, Megan. 2007. “No Artificial Ingredients?: Gender, Race, and Nation in Costa Rica’s International Tourism Campaign.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 16 (3):341–57. doi: 10.1080/13569320701682542.

- Robertson, Zoe, Sandra Gifford, Celia McMichael and Ignacio Correa-Velez. 2016. “Through Their Eyes: Seeing Experiences of Settlement in Photographs Taken by Refugee-Background Youth in Melbourne, Australia.” Visual Studies 31 (1):34–40. doi: 10.1080/1472586X.2015.1128845.

- Rose, Gillian. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. 4th edition. Los Angeles, CA, and London, UK: SAGE.

- Senior, Diana. 2007. “La Incorporación Social en Costa Rica de la Población Afro-Costarricense Durante el SXX: 1927-1963 [The Social Inclusion in Costa Rica of the Afro-Costa Rican Population During the 20th Century: 1927-1963]. “San Jose, Costa Rica: MA thesis, Department of History, University of Costa Rica.

- Sheller, Mimi. 2003. Consuming the Caribbean: From Arawaks to Zombies. London, UK, and New York: Routledge.

- Urry, John, and Jonas Larsen. 2011. The Tourist Gaze 3.0. Los Angeles, CA, and London, UK: SAGE.