Abstract

Touristic advertisements, development reports and government sources in Pakistan readily use the natural beauty of Gilgit-Baltistan, above all lavish shots of mountain peaks, to promote the country’s hospitality and global appeal. Since the public sphere is full of promotional material for this region, local people have also started posing in front of newly discovered sights for photos. While men often upload these on Facebook and WhatsApp, young women do also take part in outings and photo shoots, but behind a digital veil that does not allow them to advertize their photos so openly. Through visual examples from media both on- and offline, I will show how consumption and engagement with social media feed back into people’s (self-)perception of their natural and cultural environment. Popular representations of the region’s landscape even serve as a form of self-othering: looking at Gilgit-Baltistan’s assets through the eyes of outsiders allows many young people to appreciate things they previously ignored or took for granted, even seeing them as obstacles to development. Moreover, by actively contributing to public discourse, locals reclaim the represented and disseminated imagination of their homeland.

MOUNTAIN VIEWS ON- AND OFFLINE

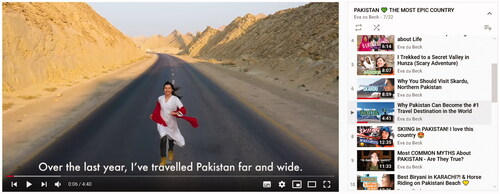

A young Western woman, clothed in a loose-fitting white dress, is running down a scenic desert highway in the middle of nowhere. Given the perspective of the shot, it must have been taken from a drone filming her from above (). “I believe that Pakistan can be the world’s number one tourism destination,” she declares, in a voice that is as serene as the images shown in the five-minute clip.Footnote1 The YouTube videos of the travel blogger Eva zu Beck have each attracted hundreds of thousand of views. Indeed, out of all the videos she has posted from destinations around the globe, those about Pakistan have received the most clicks. Comments suggest that her audience comes from both Western countries and Pakistan. Throughout 2018 and 2019 she shared her enthusiasm for Pakistan through numerous videos, at least half of which focus on the mountain ranges in the north of the country. That is also where she begins her line of arguments for the potential of tourism in Pakistan: “Starting with the mountains of Pakistan, one of the greatest assets that nature has bestowed on this country.”

Figure 1 Screenshot from Eva zu Beck’s 2019-YouTube video in which she recommends traveling to Pakistan. (Shot by the author, May 2021)

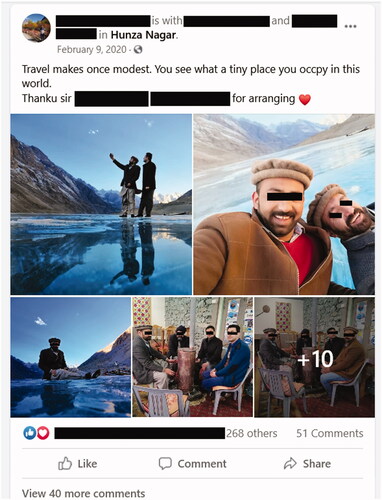

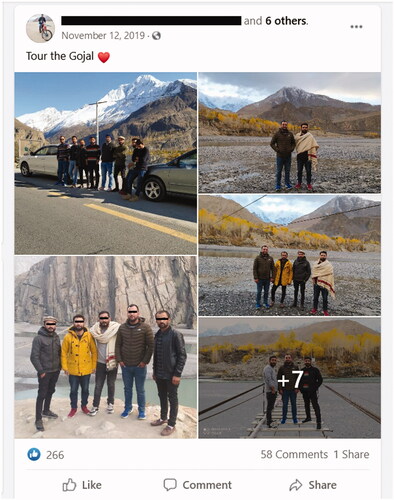

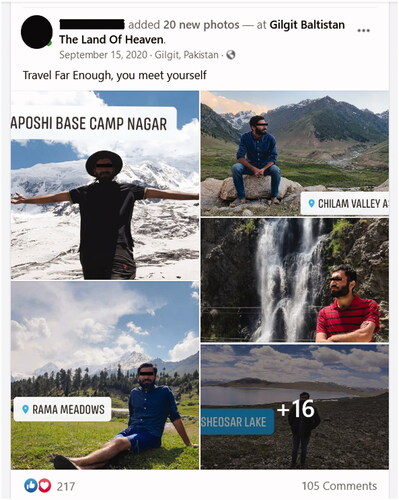

Video clips and Instagram shots of this smiling young woman traveling the country all on her own stand in stark contrast to photos taken by local inhabitants of the very same mountain scenes while on small tourist outings. In the majority of these, no women are to be seen. Rather, a group of men, dressed in jeans and shirt, some wearing the typical Gilgiti felt cap, stand on the side of the road, the majestic scenery of snow-covered peaks behind them, and stare into the camera with blank, serious faces (). While titles and comments indicate that these mountain dwellers themselves enjoy local trips, only recently have some of the men in the images begun to also present a slight smile. Until a few years ago travel in Pakistan primarily existed only for the purpose of visiting family members, commuting to work, school or a medical facility, engaging in trade, herding, or going on pilgrimage to visit shrines, but today's “outings” have a more recreational purpose, and on social media they are now readily presented and performed to display one’s status as a “modern,” global citizen.

Figure 2 Screenshot of Facebook posts by young Gilgit men touring their region. (Shot by the author, 2021)

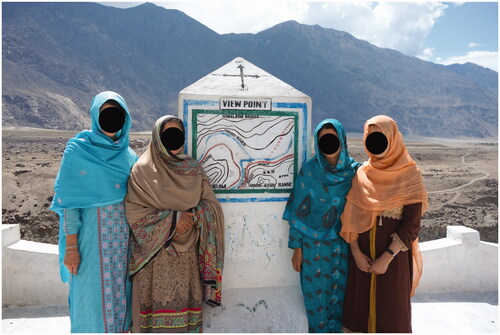

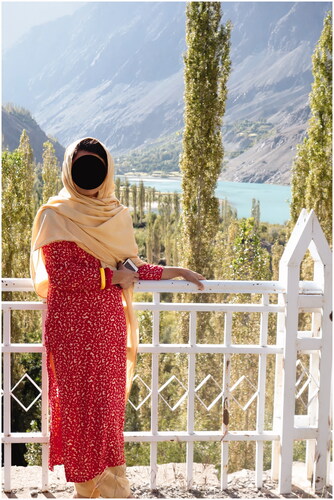

For nearly a decade I have been witnessing the increasing touristification of landscape use in Gilgit-Baltistan, the northernmost region of Pakistan. During that period I have seen these shifts both on Facebook, the medium most widely used to access and communicate across the Internet, as well as on the ground through 14 months of ethnographic research on gender relations and media engagement (primarily conducted in 2014 and 2015; Walter Citation2021). While the public sphere is full of promotional material for the region’s growing tourism industry as well as of selfies of local men posing in front of newly discovered sights, women’s appropriation of the landscape surrounding them is rather less visible. Even though there might be fewer opportunities for them to venture out, going on family picknicks, school trips, or motorcycle outings with a fiancé are very popular activities among women today. Often not uploaded on Facebook or other social media platforms, private photos of these events do exist (). Though such images of women feature similarly stiff postures as their male counterparts and privilege decorum over more relaxed or informal poses (e.g. laughing out loud or having their hair uncovered), they underlie social conventions of parda, the metaphorical as well as physical veil that traditionally keps women out of view to maintain gender segregation (Walter Citation2016).

By juxtaposing public media discourses of Gilgit-Baltistan’s landscapes with local inhabitants’ appropriation of such touristic aesthetics, this paper seeks to endorse and further develop a hybrid, mixed-method methodology that amalgamates participant observation and media analysis (Cocco and Bertran Citation2021; Przybylski Citation2021). Especially when considering media expression, “many ethnographic fieldsites […] exist across digital and physical spaces” (Przybylski Citation2021, xiii). It is therefore essential to overcome the initial separation of “real” and “virtual” world that was often fashioned by early digital anthropologies. As face-to-face encounters today increasingly exist in parallel to and are extended by remote communication on smartphones or other devices, Liz Przybylski emphasizes in her recent handbook for Hybrid Ethnography (Przybylski Citation2021) that the focus of such a methodology still lies in personal aspects of connections, but these relations continue “from the offline to the online and in-between” (Przybylski Citation2021, 4). Methodologically a hybrid ethnography follows the same guidelines as more customary anthropological inquiry and analysis based on observation and participation, but it additionally offers a wide range of readily available discourse online, thus bringing together different modes and spaces of interaction that a fully online or fully offline field would not provide.

As ethnographic fieldwork is always partial and is integrally a part of the researcher’s positionality, I am proposing a toolkit that lives up to the various dimensions of visual mediation: a “both–and” approach that benefits from bringing and thinking together that which a digital anthropologist might not see online or a conventional ethnographer might miss in person—and how these spheres intersect as well as interact. In the case of my fieldwork in Gilgit-Baltistan this means that social media offer a glance at all-male sightseeing trips that I, as a woman in a gender-segregated society, could not attend in person. On the other hand, offline long-term participant observation provides the background context for interpretation. The examples I invoke will show how consumption and engagement with social media feeds back on people’s (self-)perception of their natural and cultural environment. Popular representations of the region’s landscape even serve as form of self-othering: looking at Gilgit-Baltistan’s assets through the eyes of outsiders lets many young people appreciate things they previously took for granted or even saw as obstacles. Moreover, by actively contributing to public discourse on social media, locals reclaim the represented and disseminated imagination of their homeland.

TOURISTIFICATION VS. REPRESENTATION OF GILGIT-BALTISTAN

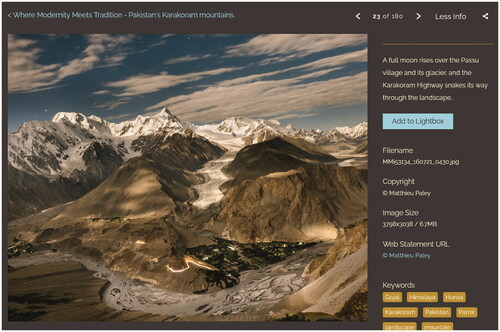

The term “landscape” and the public understanding of its aesthetics originated in the Renaissance art of painting. In such images, picturesque scenes of “nature” serve as a passive backdrop for human life. A wide-angle perspective that captures the expanse of lush valleys or majestic mountains still dominates contemporary landscape photography—a beautiful still-life objectified by the beholder. In the case of Gilgit-Baltistan, the spectacular takes of the internationally acclaimed photographer Matthieu Paley are well known for exploring the region’s geographical remoteness (). As is the case in much travel photography, many of Paley’s pictures implicitly convey a sense of exoticism and timelessnessFootnote2 (Smith Citation2020; Wells Citation2000). Despite a long process of “naturalization”—in which the audience has learned to see the scenery as neutrally extant—landscape is not a given “reflection of reality” but represents a certain manifestation of a physical territory in time that depends for its reproduction on technology, perspective or the viewer’s associations with the scenery being depicted (Hirsch Citation1995; Tilley and Cameron-Daum Citation2017). While ethnographies have always relied on the convention of describing regional territory, anthropology has long considered it rather more important to “bring into view” the “meaning imputed by local people to their cultural and physical surroundings” (Hirsch Citation1995, 1).

Figure 4 Screenshot of a photo and its description in Matthieu Paley’s web album of scenes from northern Gilgit-Baltistan, published in 2016. (Shot taken by the author, 2021)

As much of contemporary anthropology is dominated by a materialist approach, place is essentially conceived through and influenced by phenomenological experience which permeates people’s minds and imaginations (Escobar Citation2001; Ingold Citation2000; Massey Citation2005). Moreover, Tim Ingold (Citation2008) emphasizes landscape’s processual character: places come to life by our moving in and through them; as humans physically engage with their environment, they shape it but are also shaped by it. An increasing mediatization of landscape, especially when disseminated and co-constructed on social media, poses new questions for such a performative and affective geography (Navaro-Yashin Citation2012). As my focus here lies in the visual representation of landscape, I am particularly concerned with the changing nature of engaging with the physical environment of the mountains and its aesthetic influence through travel blogs and tourism campaigns. In this regard the presence of images of the mountains uploaded on social media by local residents ties in with wider questions of representation and identity, thus transporting a certain narrative that serves as a repository for meaning and belonging (Filippucci Citation2010).

Whether for touristic advertisements or development reports, visual material used to represent Pakistan typically features lavish shots of Gilgit-Baltistan’s high peaks, among them K2 (8611 m elevation) and Nanga Parbat (8126 m). Government officials readily use the region’s natural beauty to promote the country’s hospitality, tolerance and global appeal. For example, three of the five photos displayed on the landing page of the Pakistani Ministry of Tourism’s website hail from the mountain ranges in the country’s North: snow-covered peaks, colorful Kalash women, and the oasis of a mountain valley.Footnote3 This mobilization of the region stands in stark contrast to its otherwise precarious constitutional status.

As part of the former Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir, the region has been deadlocked in the Kashmir conflict between Pakistan and India since the time of Partition in 1947. While Gilgit-Baltistan sided with Pakistan and has since not been a site of actual combat as has happened along the Line of Control (LoC) further south, it has never acquired full provincial status, and various military as well as government institutions of Pakistan have engaged in camouflage tactics of the disputed territory. In Delusional States, Nosheen Ali (Citation2019) describes the ambiguity of misrepresentations, even the outright omission of the region across various forms of Pakistani state media, such as schoolbooks, maps and government sources. In a number of such examples, the region is vaguely referred to as alternative territories, with various names (i.e. formerly simply known as Northern Areas), no mention of any ethnic identity, and only recognized for its natural beauty—a “landscape-only, no-people no-region depiction” (Ali Citation2019, 42). Alluding to different revisionist scenarios of the region’s political status as a part of Kashmir, India, Pakistan, or some diffuse northern frontier, successfully obscures Gilgit-Baltistan’s existence and compromises its own strong identity, rendering it vague and visible only through its physical environment. Regardless of whether these moves were the result of ignorance or were intentionally engineered to exert control, such practices of illegibility typically only show one side of the coin—the discourse about Gilgit-Baltistan—and do no justice to local people’s political struggles for recognition or their desire to be represented with a distinct regional identity. On the contrary, their mountains are only appreciated for their natural beauty and even divorced from their regional context, serving as “eco-body of the nation” (Ali Citation2019, 31).

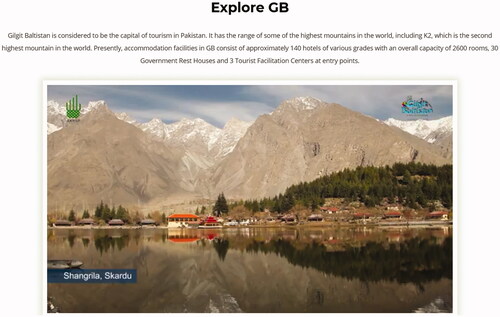

Although the region’s mountainous terrain is a formidable obstacle to any kind of infrastructure—for example, roads are regularly blocked and damaged by loose rocks—mobile phone signals nowadays reach almost every village, and with them arrives mobile internet that is widely accessed most often via Facebook. In this way, younger generations in particular become aware of circulating YouTube videos and other social media posts that aim to promote tourism and diversify Pakistan’s image as an Islamist state. The international NGO of the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP), for example, working with the Tourism Department of Gilgit-Baltistan to increase economic activity in the region, has produced various videos on the region’s touristic potentials (). One of these, Jewel of Pakistan,Footnote4 has been widely circulated by my Gilgiti interlocutors on Facebook and the phrasing was picked up by various local sites “designed to convey information about Gilgit-Baltistan” (Facebook/GilgitBaltistanTheJewelofPakistan).

Figure 5 Screenshot from the promotional film Jewel of Pakistan on the website of the Gilgit-Baltistan’s Tourism Department. (Shot taken by the author, 2021)

All such promotional material invokes images of remoteness and exoticism () which build on a long legacy of (post)colonial orientalism of the region (Hussain Citation2015). The best known of such stereotyped, essentialized depictions might be James Hilton’s famed Citation1933 novel Lost Horizon, in which he describes the utopian earthly paradise of the Shangri-La hidden in a remote valley in the Himalayas which is populated by immortal, harmonious people. Although Hilton was actually referring to Tibetan Buddhism, Gilgit-Baltistan’s tourism industry has long claimed that he was really inspired by a visit to the Hunza valley in the early 1930sFootnote5 and widely draws on the labels of the Lost Horizon (Capra Citation1937) or the Shangri-La that lend their name to a number of tourist resorts and sightseeing spots throughout this region, and South and East Asia more broadly (Liechty Citation2017; Yeh and Coggins Citation2014).

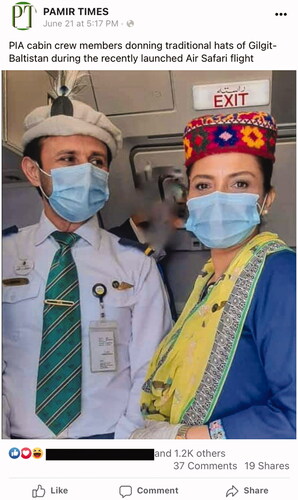

Figure 6 Pakistan International Airlines staff with typical hats from Gilgit-Baltistan to promote the launch of a tourist route, called Air Safari (!), to Skardu in June 2021. (Photo uploaded to Facebook by Pamir Times, 2021)

Similar tales are told in movie plots: much like the conspicuous setting of Bollywood movie scenes in India’s Ladakh region, the mountains of Gilgit-Baltistan also increasingly serve as backdrop for film scenes in Pakistani film productions, such as in Dukhtar (Nathaniel Citation2014), Chalay Thay Saath (Adil Citation2017), or the biographical Motorcycle Girl (Sarwar Citation2018). Consequently, numbers of youth traveling north from Karachi or the Punjab into the mountains have increased dramatically in recent years. In pre-pandemic 2019, local authorities registered more than 10,000 international and even one million domestic tourists (Gilgit-Baltistan Directorate for Tourism, Sports and Culture, June 2021). Many visitors stage selfies in front of scenic landscapes and upload them onto social media, where they then go viral and find their way back to audiences in Gilgit-Baltistan. For examples, one can browse through multiple Facebook groups about Gilgit-Baltistan or find many results for a search on “Karakoram Highway” on YouTube (). As the local population becomes increasingly aware of their natural environment’s assets, young people in particular discover for themselves practices of touristic consumption: they travel the mountain roads without any “business” (kaam) purpose, solely to visit viewpoints as recreational outings (or “picnics,” as they call them) and take turns posing for pictures.

Figure 7 Search results for “Karakoram Highway” on YouTube, featuring scenic pictures and catchy titles of informal documentary or travel videos. (Shot taken by the author, 2021)

Tourism studies offer a wide repository of approaches to dissect various aspects of the junctures between travelers, local society, environment and cultural heritage. Zooming in on global/local dynamics, the concept of touristification perfectly captures the phenomenon of “promoting new ways of using space and modifying cultural landscapes as well as the territoriality of the tourism destination” (Ojeda and Kieffer Citation2020, 143, referring to Jansen-Verbeke Citation2009; also Saarinen et al. Citation2017). While I appreciate the strong linking of landscape and its appropriation with temporality, hence people’s changing attitude toward it over time, this paper at the same time shows that an analysis of touristic content on social media adds an important layer to a research approach grounded in in situ research. To argue that ethnographic fieldwork can fruitfully be complemented by processes of mediatization, I will now pay closer attention to how media discourses around tourism, landscape and heritage are received and adopted by young women and men of Gilgit-Baltistan.

CHANGING MODES OF LANDSCAPE CONSUMPTION THROUGH A GENDERED LENS

During my fieldwork in the city of Gilgit, its suburbs and surrounding valleys, I was astonished that most people did not seem to notice the spectacular landscape around them. It was only me who frequently gazed up at the snow-covered mountaintops, many of which have no name. Women in particular seemed to be too preoccupied with their daily chores to notice anything beyond their social radius of the household compound and immediate neighborhood. While they were eager to run errands to local markets or to visit nearby relatives, most of the adult women I met expressed no interest in hiking up a hillside for fun. Walking to distant orchards or a water channel far above the village was a necessary task, and the mountain slopes were seen as obstacles, not a scenic pleasure. In her study of local residents’ changing perception of landscape and environment, Julie Flowerday summarizes for Hunza valley in the early 20th century:

From rulers to commoners, all depended on agriculture, tree cultivation and herding. People ate what they produced, which concurrently internalized activities of faith, practices of marriage and daily routine. […] Life was reproduction. The environment was an active image of the recreation of land, people, animals and spirits that assured the future of it all. (Flowerday Citation2007, 90)

Today, while subsistence agriculture still exists in Pakistan, it is complemented by a market economy that has distanced the public somewhat from their natural environment. Many families have given up time-consuming husbandry in the high pastures, which as a result have become a site of nostalgia and are open for reinterpretation as recreational locales. The further people outgrow the agricultural production mode, young men—and following their example increasingly also women—express the wish to go up to the high pastures. Over and over young women excitedly told me of past adventures and nourished their memory of a trip to some different mountain valley, whether organized by their school, as a family outing in a rented minivan, or on the back of their fiancé’s motorcycle. As a treat for my interlocutors, I sometimes arranged a small road-trip to a nearby place of touristic interest. On such occasions I was able to appreciate younger as well as older women’s joyous moods, experience for myself the frisson that came with a break from everyday household life, and play the role of photographer for the multiplicity of pictures that both women and men enjoyed posing for at every stop ( and ).

While the photos were later circulated on mobile phones or gifted to my friends by me as printouts, women’s presence on these trips was not registered on social media. And young men only uploaded pictures on Facebook that showed them alone in the same spots where we had also taken group photos—as if no women had been present at all. Women’s invisibility on social media corresponds with their relative physical absence from the public sphere (Schoemaker Citation2015; Walter and Grieser Citation2020), but this does not mean they are not users of online platforms. When they scroll through their male relatives’ Facebook walls, they engage with social media threads more passively as consumers, rather than active producers of content. In this way they get a glimpse into the leisure trips of their brothers, husbands or cousins ( and ) —in the same way that I did from my university desk back in Germany once I had returned from the field. As the male domain of business and politics lies beyond the house it is not only physically separate but also not a matter of much discussion at home. This was also true for my insights into the time which men spent with other men at work or in all-male gatherings. They might mention a spontaneous picnic with colleagues at the joint family dinner or share a humorous anecdote with their cousins, but details of their activities would remain rather opaque. Facebook posts or WhatsApp status updates of photos with their friends and acquaintances increasingly perforate the gender divide and allow women insights into what their male relatives have been doing throughout the day, where they went, who they were with, and how they behaved in same-sex company.

Figure 10 Screenshot of Facebook posts by young men from Gilgit-Baltistan on sightseeing trips throughout the region. (Shot taken by the author, 2021)

Figure 11 Screenshot of Facebook posts by young men from Gilgit-Baltistan on sightseeing trips throughout the region. (Shot taken by the author, 2021)

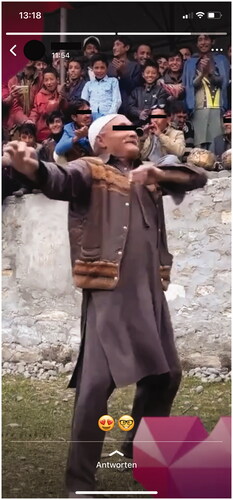

Having ended my primary period of fieldwork (2014–15) over six years ago, I am an even more engaged follower of social media posts by my former interlocutors from afar. Their activity of sharing content, posting photos, liking, and commenting on others’ status updates has increased massively over the years since I returned home. As have men’s uploads of their own photos, not only in front of attractive landscapes but also at university- or work-related events or pondering local heritage. Still, the emphasis is on the special occasions of sightseeing trips. What began a decade ago as initial attempts at approaching the local environment with the lens of an outside observer has now grown into a full-fledged trend of touristic consumption. Through media campaigns that proliferate ideas of leisure and natural beauty, local inhabitants have become aware of their environment’s assets and have begun to “consume” their mountain landscape themselves. Moreover, by going on family outings to serene picnic spots, celebrating media ads and movie clips online, and uploading photos of men dancing in front of the iconic Rakaposhi mountain, men from Gilgit-Baltistan contribute eagerly to, and even accelerate, the very same media discourses. Interestingly, most locals’ Facebook posts are accompanied by captions in English. Of course, English, rather than Urdu (the official state language) or Shina (the local vernacular, spoken by roughly half a million people), is commonly understood to be the lingua franca for such an international platform. Moreover, the use of English in these posts suggests the target of a wider audience, a desire to express publicly one’s awareness of and appreciation for the natural and cultural heritage of the region.

ON HERITAGE AND HYBRIDITY

Touristic imaginations often operate with ideas of otherness about an area’s untouched remoteness and its timeless traditions (Enzensberger (Citation1958) 1996; Salazar and Graburn Citation2014). The proliferation of Gilgit-Baltistan’s local heritage therefore seems a logical consequence of the process of touristification. Although Pakistani visual media campaigns of government institutions and the tourism industry do focus in large part on the spectacular mountain landscape, I have seen a growing trend among local interlocutors to speak out and advertize indigenous skills and customs on social media. Encouraged by NGOs like the Aga Khan Foundation, who work to preserve the region’s historic monuments and support community-based approaches for tourism development (Khan Citation2012; Kreutzmann Citation2013), Gilgit-Baltistan’s small tourism industry has increasingly integrated organized offers of local food, folkloric dances, shamanistic séances, trips to wood-carving workshops or polo matches into their repertoire. Since this trend feeds into a regional identity, it is unlikely to be encouraged by national institutions but hits a nerve with the solvent visitors who visit from urban centers and seem to take the offer up eagerly: photo uploads on Instagram, Facebook and other online platforms promote this trend for the search of the “authentic” and “original” as counter-caricature to their own busy, “modern” lives.

For the host population the motivation is more complex than simply enacting a revival of the past. In her work on territorial cohesion as an outcome of touristic attention, Myriam Jansen-Verbeke has noted that the mutual relationship of tourism and identity formation “does not represent exactly a return to the regional geography of the past, but an attempt to revive the territorial coherence between a place and its people, their history, habitat, and heritage in a globalized world and cosmopolitan community” (2009, 26). It means to reconcile cultural heritage with contemporary life and being proud of vernacular history.

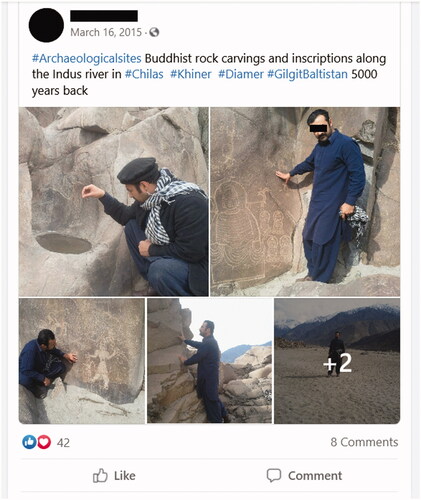

Just as Gilgit-Baltistan’s existence, let alone its regional identity, has been ignored and overlooked by the Pakistani state, so has its cultural heritage been repressed. Although many of the mountain’s landmarks and historic sites—like the Hunza fort or Buddhist rock carvings—do appear in schoolbooks and publications for popular consumption, their exact locations are obscured and appear to be fully within Pakistan rather than in a specific, marginalized region (Ali Citation2019). Consequently, on my frequent visits to the Punjab I was repeatedly asked about the “Pathans” where I did my research. The Pakthuns, however, mainly live in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkwa toward Afghanistan; but readily associating them with mountainous terrain to the North exemplifies how unaware mainland Pakistanis are of the ethnic and linguistic diversity of Gilgit-Baltistan. Such an example “effectively serv[es] to depoliticize it [Gilgit-Baltistan] by invisibilizing its specificities and social identities” (Ali Citation2019, 43). Despite regionalist political campaigns over the last decades and the efforts of local poets to voice collective sentiments of alienation (Ali Citation2019), trends of self-representation have only recently gained momentum through mass-dissemination on social media.

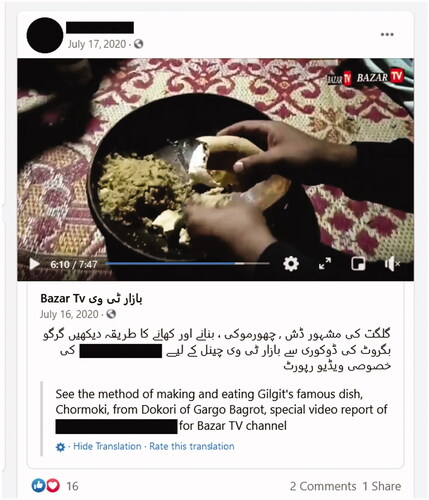

Salman Paras, Gilgit’s most popular contemporary singer, a man who produces new pop songs in the Shina language with tunes characteristic of the mountain region, has recently professionalized his music videos. They are not only filled with expansive shots of landscape but also feature folkloric scenes, for example showing him and other musicians in traditional dress, dancing in the typical slow style of Gilgit-Baltistan with snapping fingers held up beside the head, or presenting scenes of a local polo match.Footnote6 Over the last decade citizen journalism has also been a growing phenomenon (Stadler Citation2014). Using platforms such as PamirTimes.net, aspiring reporters not only produce news content in written form but increasingly also add small video features, a practice picked up by other young men. As private individuals they promote their role in society as educators or lamabadar (village heads), or engage in “culture promotion” Footnote7 by filming and explaining local crafts and agriculture ( and ). Many of these clips are shared to one of Gilgit-Baltistan’s Facebook pages and then circulate online (cf. Facebook/heavengilgitbaltistan). While amplified attention to local culture runs the risk of bringing with it a certain touch of exoticization or othering,Footnote8 the option of producing one’s own media content does give young people the opportunity to contest the oft-disseminated image of them living in a backward place, and to compensate the void of political representation with their own agentive expressions of belonging and identity.

Figure 12 Screenshot of a Facebook post shared by a man from the Gilgit region to promote the value of rural traditions. (Shot taken by the author, 2021)

Figure 13 Screenshot of a young woman’s WhatsApp status update that features a shaman dancing to local tunes. (Shot taken by the author, 2021)

Since informal indigenous presentations of heritage follow the same sensationalist aesthetics as media campaigns about the natural environment, they can perpetuate the process of touristification, though in this sense less of the appropriation of landscape than a touristification of self-representation. It is love at second sight: through the high visibility of Gilgit-Baltistan on social media, locals acquire an external view of their own environment and learn to cherish what used to be taken for granted or even seen as an obstacle to development. The imagery of umpteen (often nameless) high peaks that serve as backgrounds for images taken by both domestic and international tourists, prompt the growth of regional consciousness and lead to efforts at cultural conservation. Moreover, that local people are agentively co-opting external visualizations of their own land and people, states that they too have a say in how their lives are to be represented, consumed and reproduced.

Such discourses on heritage however are largely absent from women’s domains. Women too debate ideas about a “good, modern” life but mostly consider areas of their influence in the private sphere, through pursuing further education, taking up a job in education, or becoming more “empowered” within the family, pursuing equality in conjugal relationships, and negotiating various manifestations of piety (Walter Citation2021). Active engagement in the public sphere of tourism or culture promotion is thus not a primary objective for them.

CONCLUSION

In this paper I have visualized how life and media worlds are segregated along gender lines in Pakistan. Neither detailed ethnographic fieldwork nor the analysis of media discourses on their own lives up to these partial realities. A hybrid approach can however give fruitful insights into both sides, not in ways that necessarily fall together into a whole but rather as a means of diversifying and contextualizing different and at times distinct perspectives that do not exist separate from public discourses. Paying attention only to the visible can indeed be misleading: While I might have overlooked a rising awareness for local traditions during fieldwork, outside observers might similarly be biased when only looking at Facebook profiles that lack women’s participation or representation. What is readily visible in one sphere may be inconspicuously invisible in the other and vice versa—though there exist porous boundaries between them. Even if there is no visual evidence on social media this does not mean that women never take part in picnic outings. Social media also offer women the opportunity to catch glimpse of men’s activities “outside” the house and witness ongoing discourses of regional representations that they otherwise are not part of.

Just as Elizabeth Mazzolini (Citation2015) describes for the case of Mount Everest, in Gilgit-Baltistan local subjectivities are formed through the visual representation of “their” landscape, which renders an inaccessible terrain as being more within reach to passive consumers. Movies, photos, online posts and actual trips to view points help people to get familiar with the mountains and pan giant massifs in a clear frame—a process similar to the role of panorama paintings in the early days of Alpine tourism. Through the example of the touristification of landscape consumption by the local population, this paper has sought to focus on the intersection of online and offline environments. In this way, an ethnographic study of social media can be a valuable addition to (or extension of) field immersion—particularly if, as John Postill and Sarah Pink observed a decade ago, we are to “understand the internet as a messy fieldwork environment that crosses online and offline worlds” (Postill and Pink Citation2012, 126). As human sociality becomes increasingly hybrid across multiple spheres, so do we need to adapt our research methodologies:

The crucial point here is triangulation, that is, the ethnographic imperative to gather primary and secondary materials on a given question through as rich a variety of sources as possible, including the ever-expanding ways of being there. Relying solely on physical co-presence, non-digital fieldwork or telematics is still theoretically possible, but in most research settings it would no longer make epistemological sense to do so. (Pink et al. Citation2016, 135)

While many anthropologists have argued that digital ethnography does not vary much from conventional research approaches but rather expands the fieldsites, I argue that following a hybrid both–and approach for data collection as well as analysis pushes the limits of anthropological work in various dimensions. It requires different toolkits, i.e. participant observation as well as media discourse, to interpret intersecting contexts heuristically; it enables researchers to comply with and reconcile private and professional demands of more flexible, short-term field stays and remote ethnography (Günel, Varma and Watanabe Citation2020); and, most importantly, it unfolds and shifts power asymmetries. The acknowledgement that interlocutors are producers of content in their own right might be nothing new yet rarely reveals itself as obviously as through social media use (Przybylski Citation2021; also Hughes and Walter Citation2021). Blurring the distinction between co-producers of knowledge not only positively lives up to postcolonial and feminist demands to decenter the anthropologist but also opens up new avenues for insight. The availability and diffusion of mobile internet throughout Gilgit-Baltistan over the past decade has created an active online culture of consumption and reproduction of touristic representations of the region. Social life no longer takes place only face-to-face but also on social media, where posts serve to express certain views, strengthen relationships, promote one’s regional identity, and enable locals to become part of a global community through self-representation, as more or less visible participants—in recent years even with less stern faces and more often with a smile ().

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks the interdisciplinary team of CONTOURS researchers for their stimulating intellectual exchange.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna-Maria Walter

ANNA-MARIA WALTER has worked on the anthropology of emotions, gender relations and mobile phones in the high mountains of Gilgit, northern Pakistan. Her book Intimate Connections has just been published by Rutgers. After completing a Ph.D. at LMU Munich, where she also held a lectureship, Anna-Maria is now a postdoctoral researcher at Oulu University, Finland, working in an interdisciplinary EU–Russian collaboration on sustainable tourism and remoteness. In her current research, she focuses on perceptions of mountainous landscapes in the Himalayas and the Alps, the socio-ecological dimensions of Alpine ski touring, and digital anthropology. A recent paper, in American Ethnologist, deals with conceptions of the self through social media use. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

2 https://paleyphoto.photoshelter.com/gallery/Where-Modernity-Meets-Tradition-Pakistans-Karakoram-mountains/G0000iS_fAXha5ZQ/0/, selection also published in National Geographic, 2016: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/gojali-pakistan-islam

4 Available at https://visitgilgitbaltistan.gov.pk/DiscoverGB

5 A blog entry on the tourist website has recently been “corrected” to state that the exact location of Hilton’s Shangri-La is open to speculation: https://visitgilgitbaltistan.gov.pk/blog/105

8 See the example of a report about Gilgit-Baltistan’s shamans on Pakistani TV that has gathered almost 25,000 hits since 2012 but might turn out to become dangerous for the portrayed persons when branded as kafir (infidel) through the clip’s wide circulation on the internet. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDT3OpNSJ5A

REFERENCES

- Ali, Nosheen. 2019. Delusional States. Feeling Rule and Development in Pakistan's Northern Frontier. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Cocco, Chiara, and Aleida Bertran. 2021. “Rethinking Religious Festivals in the Era of Digital Ethnography.” Social Analysis 65 (1): 113–22.

- Enzensberger, Hans Magnus. [1958] 1996. “A Theory of Tourism.” New German Critique 68 (68): 117–35. doi: 10.2307/3108667.

- Escobar, Arturo. 2001. “Culture Sits in Places. Reflections on Globalism and Subaltern Strategies of Localization.” Political Geography 20 (2): 139–74. doi: 10.1016/S0962-6298(00)00064-0.

- Filippucci, Paola. 2010. “Landscape.” In The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by F. Stein, S. Lazar, M. Candea, H. Diemberger, J. Robbins, A. Sanchez, and R. Stasch. Cambridge, UK: Division of Social Anthropology, University of Cambridge. doi: 10.29164/16landscape.

- Flowerday, Julie. 2007. “Hunza in Transition. Now and Then… and Then Again.” In Karakoram. Hidden Treasures in the Northern Areas of Pakistan, edited by Stefano Bianca, 87–97. Turin, Italy: Umberto Allemandi & Co.

- Günel, Gökçe, Saiba Varma, and Chika Watanabe. 2020. “A Manifesto for Patchwork Ethnography.” Cultural Anthropology. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/a-manifesto-for-patchwork-ethnography.

- Hilton, James. 1933. Lost Horizon. London, UK: Macmillan.

- Hirsch, Eric D. 1995. “Introduction. Landscape. Between Place and Space.” In The Anthropology of Landscape. Perspectives on Place and Space, edited by Eric D. Hirsch and Michael O'Hanlon, 1–30. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Hughes, Geoffrey, and Anna-Maria Walter. 2021. “Staying Tuned. Connections beyond 'the Field.’ ” Social Analysis 65 (1):89–102. doi: 10.3167/sa.2021.650105.

- Hussain, Shafqat. 2015. Remoteness and Modernity. Transformation and Continuity in Northern Pakistan. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment. Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2008. “Entanglements of Life in an Open World.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40 (8): 1796–810. doi: 10.1068/a40156.

- Jansen-Verbeke, Myriam. 2009. “The Territoriality Paradigm in Cultural Tourism.” Turyzm/Tourism 19 (1–2): 25–31. doi: 10.2478/V10106-009-0003-z.

- Khan, Khalida. 2012. “Tourism Downfall. Sectarianism An Apparent Major Cause in Gilgit-Baltistan (GB), Pakistan.” Journal of Political Studies 19 (2): 155–68.

- Kreutzmann, Hermann. 2013. “Preservation of Built Environment and Its Impact on Community Development in Gilgit-Baltistan.” Berlin Geographical Papers 42:1–40.

- Liechty, Mark. 2017. Far Out. Countercultural Seekers and the Tourist Encounter in Nepal. Chicago, IL, and London, UK: University of Chicago Press.

- Massey, Doreen B. 2005. For Space. London, UK, and Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mazzolini, Elizabeth. 2015. “The Everest Effect. Nature.” Culture, Ideology. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

- Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2012. The Make-Believe Space. Affective Geography in a Postwar Polity. Durham, NC, and London, UK: Duke University Press.

- Ojeda, Antonio B., and Maxime Kieffer. 2020. “Touristification. Empty Concept or Rlement of Analysis in Tourism Geography?” Geoforum; Journal of physical, human, and regional geosciences 115:143–45. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.06.021.

- Pink, Sarah, Heather A. Horst, John Postill, Larissa Hjorth, Tania Lewis, and Jo Tacchi. 2016. Digital Ethnography. Principles and Practice. London, UK, Thousand Oaks, CA, New Delhi, and Singapore: Sage.

- Postill, John, and Sarah Pink. 2012. “Social Media Ethnography. The Digital Researcher in a Messy Web.” Media International Australia 145 (1): 123–34. doi: 10.1177/1329878X1214500114.

- Przybylski, Liz. 2021. Hybrid Ethnography. Online, Offline, and in Between. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Saarinen, Jarkko, Christian M. Rogerson, and C. Michael Hall. 2017. “Geographies of Tourism Development and Planning.” Tourism Geographies 19 (3): 307–17. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2017.1307442.

- Salazar, Noel B., and Nelson H. H. Graburn (eds.). 2014. Tourism Imaginaries. Anthropological Approaches. New York, NY, and London, UK: Berghahn.

- Schoemaker, Emrys. 2015. “Facebook Domestication.” Tanqeed. http://www.tanqeed.org/2015/07/facebook-domestication/

- Smith, Sara. 2020. Intimate Geopolitics. Love, Territory, and the Future on India's Northern Threshold. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Stadler, Claudia. 2014. “Öffentlichkeit und Teilhabe. Citizen Journalism in Gilgit-Baltistan.” Ethnoscripts 16 (1): 51–66.

- Tilley, Christopher, and Kate Cameron-Daum. 2017. An Anthropology of Landscape. The Extraordinary in the Ordinary. London, UK: University College London Press.

- Walter, Anna-Maria. 2016. “Between “Pardah” and Sexuality. Double Embodiment of “Sharm” in Gilgit-Baltistan.” Rural Society 25 (2): 170–83. doi: 10.1080/10371656.2016.1194328.

- Walter, Anna-Maria. 2021. Intimate Connections. Tracing Love amid Pakistan's High Mountains. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Walter, Anna-Maria, and Anna Grieser. 2020. “Feminine Intrastructures in a Men-made City.” Roadsides 004:52–60. doi: 10.26034/roadsides-202000407.

- Wells, Liz (ed.). 2000. Photography. A Critical Introduction. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Yeh, Emily T., and Chris Coggins (eds.). 2014. Mapping Shangrila. Contested Landscapes in the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

FILMOGRAPHY

- Adil, Umer, dir. 2017. Chalay Thay Saath. Produced by Hot Water Bottle Films; color, 120 mins.

- Capra, Frank, dir. 1937. Lost Horizon. Starring Ronald Colman and Jane Wyman; produced by Columbia Pictures; b & w, 132 mins.

- Nathaniel, Afia, dir. 2014. Dukhtar. Five production companies; color, 93 mins.

- Sarwar, Adnan, dir. 2018. Motorcycle Girl. Produced by Azad Film and Logos Film; color, 121 mins.