Abstract

This article explores the political impact of street art and symbolic creativity in challenging official hegemony. It focuses on the Russian case of social conflict around the 2022 war, specifically analyzing their pro-war “Z” propaganda and anti-war resistance in various cities. Using post-structuralist and visual biopolitical perspectives, the article examines the meaning and effects of “Z-ification” and the underground resistance to it. It argues that visual biopolitics reveals hidden aspects of political agency in a conformist society, and that Glynos and Howarth’s explanatory logics approach highlights the nature of popular protests. The research is based on an analysis of visual material from both oppositional and pro-government Telegram channels.

BUT IS IT FASCISM?

Many political observers (Nelyubin Citation2022; Vagner Citation2022; Reiter Citation2022) have suggested that the Bucha massacre of civilians in March 2022 marked a moment when Russia could no longer be understood in the old terms. A long-awaited definition was announced aloud: Russia was declared to be fascist. The historian Timothy Snyder (Citation2022) bluntly stated that Russia’s war, its justification by the superiority of the cultural aspects of the Russian nation over the “artificial state” of Ukraine, and Putin’s personalist regime were in many ways reminiscent of Hitler’s Nazism and Mussolini’s fascism. This caused a heated discussion among scholars and experts on Russia (Kurilla et al. Citation2022; Laruelle Citation2022; Roshchin Citation2022; Secker Citation2022) about the legitimacy of the definition itself,Footnote1 as well as the nature of Russia’s government, society and institutional features.

In response to Snyder, the political scientist Grigory Golosov (Citation2022) proposed a distinction between fascism as an ideology and as a regime, pointing out that Snyder was rather appealing to the former and thereby introduced some confusion into the understanding of modern Russia. Politically, Golosov asserts, Russia is indeed a personalist state with nationalist rhetoric and an aggressive foreign policy, but these traits have been typical for many other autocracies that have gone through various paths of consolidation and destruction. Hence labeling them all as “fascist” does not bring us any closer to comprehending them.

Another substantial criticism comes from Marlène Laruelle (Citation2022, 161–62), who argues that the analytical category of fascism is inaccurate or irrelevant in the case of Russia because there is insufficient evidence of “full mobilization” and ideological consistency at a grassroots level. On the one hand such a labeling is an intellectually lazy way of judging the whole of Russia; on the other, it obscures the complexity of the situation. The polemical nature of the term “fascism” doesn’t capture the moral nuances of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, nor does it help to build a more detailed interpretation of the situation inside Russia. In her book, Laruelle (Citation2021), for instance, deconstructs four arguments of Snyder’s thesis by showing how they overlook other concepts used by social scientists to understand Russia’s political and cultural features. In doing so Laruelle (ibid., 138–56) challenges historical analogies, typologies of totalitarianism, the concept of imperialism, and the relationship between far-right groups and state authorities, while acknowledging only one feature of Russia’s regime as fascist. It is what Laruelle (ibid., 112) calls the “militia subculture” that “calls, above all, for service to the state and sacrifice to the nation.”

In the same vein the political analysts Margarita Zavadskaya and Aleksey Gilev (Citation2022) refute the thesis of a totalitarian Russia, although, as they show, the country has already made some progress in this direction. Drawing on Juan J. Linz’s (Citation2000) typology of differences between totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, Zavadskaya and Gilev emphasize the significance of political mobilization. While authoritarian regimes prefer to keep society in an apolitical state, totalitarian ones mostly rely on politically active masses who engage in and promote pro-government activities. As the authors conclude, Russian society is still largely passive, showing its support for the authorities only in response to administrative coercion. Hence Russia has not yet achieved a completely totalitarian state.

This paper is sympathetic to both criticisms. “Fascism” is indeed a static term to name a condition of sedimented and legalized hegemonic practices throughout society. It lacks the ability to analyze the heterogeneous processes within society. It neglects the dynamics of social formation and does not allow us to examine the degree of the ideological perception of society, that is, whether it is moving toward or away from a state of fascism. In this respect this paper agrees with Jeremy Morris’s (Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2022c) account of Russia’s state of being, and supports the claim that any kind of reductionism leads to simplistic conclusions, and so researchers should think beyond labeling Russia as a fascist state. Russia has not yet gone so far as to return to the totalitarian regime with a planned economy, clear ideological horizon, and institutional formation, even though some of its current institutional features do resemble Nazi or fascist regimes of the past (Roshchin Citation2022).

At the same time the Russian sociologist Greg Yudin (Ernesto and Doell Citation2022) points to certain attempts to eliminate dissenting views and homogenize Russian society through “Z symbolism,” which he sees as a symptom of “an ongoing shift” toward totalitarianism and fascism. By “Z symbolism” (or “Zvastika,” to emphasize the resemblance to the Nazis’ swastika), observers refer to the viral spread of the letters Z and VFootnote2 to signal support for the Russian “special operation” across Russia and some other European countries. Ilya Budraitskis (Citation2022) points out that use of the letters Z and V, which have recently “become almost an official grim symbol of the invasion of Ukraine, adorning the windows of public transport, schools and hospitals, the cozy space of private life has lost its right to exist.” Indeed, such rapidly developing processes can be seen as symptomatic of “the complete social atomization and the dissolution of the individual into the machine of production” (ibid.) and thus of Russian fascism. However, the emphasis on the ongoing transformation of Russian society is key here. The question remains: what is the degree of this transformation, and how can we approach and interpret it? In other words, an analytical approach should inquire into the contingency of the social formation in a particular political context, rather than speculating about the static definition of a political regime. This perspective sets the research agenda for this article. By drawing attention to peculiarities of the political phenomena in Russia, the article seeks to contribute to the current flow of debate and offer a theoretical approach by which these phenomena can be analyzed.

Building on the intersection of post-structural discourse theory and visual biopolitics, this article addresses the political conditions of the dynamics of social antagonisms over the “special operation” in Ukraine within Russia. From this interdisciplinary perspective, social antagonisms can be seen as the limits of the hegemonic political project. Various forms of social antagonism escalate when the authoritarian project is no longer able to explain the reality in a simplified way and gain the consent of the public. In this case the authoritarian regime begins its transformation into a totalitarian one: first, by the cultural means of mass mobilization, politically splitting society into a unitary “us” and an existential enemy—“them”; and then, by marginalizing and criminalizing those who refuse to perform the symbolic rituals that mark the boundaries of the conformist and homogeneous environment.

In this article, I claim that these processes have accelerated dramatically in Russia after their second military invasion of Ukraine in 2022. To support this argument, the paper seeks to examine both pro-state and subversive forces that struggle for public space and social media domination to either maintain or contest the meaning of the war and its value. The article focuses on visual case studies of the virally spreading “Zvastika” discourse within the conformist part of society and the emerging anti-war graffiti, street art, and installations across Russia. Key research questions address the identitarian functioning of these visual forms of embodiment and their political characteristics for analytical purposes. What do the anti-war graffiti and forms of pro-war propaganda have to say about the condition of Russian society? How can the methods of visual biopolitics help us discover and interpret the political logics of subversion and mass totalization? To answer these questions, the paper provides an analysis of emerging forms of public support for and popular sabotage of Russia’s war. The research data consists of several thousand images taken from public oppositional and pro-government Telegram channels, as well as various analytical sources and research literature that have collected visual material of public forms of self-expression from various cities in Russia.

Below I will consider possible ways of combining the theoretical frameworks of post-structuralism and biopolitics to propose a new approach to the analysis of political phenomena in a non-democratic environment. I will then discuss the methodological tools associated with the proposed approach when I describe the data collection and case study. The final part of the article is devoted to analysis and discussion of the findings and results. In conclusion I will reflect on how the analytical perspective of visual biopolitics could possibly be applied to other areas of political inquiry.

THEORETICAL APPROACH: COMBINING POST-STRUCTURALISM AND VISUAL BIOPOLITICS

Here I aim to substantiate the methodological value of visual biopolitics in expanding the gaze of post-structuralism and its application to political analysis in non-democratic regimes. I suggest that by combining these methodologies we can obtain a clearer picture of the actual sociopolitical dynamics at play, avoiding the limitations of labels such as “fascism” or “totalitarianism.” I will however first explain the benefits of the post-structuralist framework.

As developed in political, cultural and media studies (Howarth and Stavrakakis Citation2000; Glynos and Howarth Citation2007; Carpentier Citation2018), post-structuralist discourse theory (Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001) advocates the heterogeneity of social dynamics and political contingency by recognizing various logics within a given “social formation” and the involvement of power in its construction. Following this, any hegemony is never a total completion but only a political moment of a successful attempt to totalize society through a simplified worldview (Hall Citation1988; Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001; Laclau Citation2005). Like any meaningful system, hegemony is vulnerable to subversion, change and re-articulation.

To understand the dynamics of change, social formations can be analyzed using “social, political and fantasmatic” logics (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007, 8). These logics are not “causal laws” or “mechanisms” (ibid. 83–102) but analytical categories for various practices of articulation responsible for stabilizing and undermining hegemonic discourse. In this study, I use only social and political logics. Social logics describe the scope of “hegemonic practices” (ibid., 15), in which economic, gender, cultural or social relations are taken for granted as something natural and undeniable. Political logics reveal the conditions of possibility and vulnerability of these practices by challenging and contesting them. Social logics involve obedience to rules, while political logics denote autonomy and agency. Therefore, as Laclau (Citation2005, 117; his emphasis) points out, political logics refer to “the institution of the social […], which is not an arbitrary fiat but proceeds out of social demands and is, in that sense, inherent to any process of social change.”

In this vein, any form of resistance against the dominant regime of practices can be seen as “political to the extent that it publicly contests the norms of a particular practice or system of practice in the name of a principle or idea” (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007, 115). This pattern lends itself well to democratic regimes in which the political opposition are free to express their dissatisfaction and criticize the government, in other words, in which nonconformity or sabotage is easy to spot. But what can we say about subversion and the character of political logics in undemocratic regimes, in which critical voices are suppressed and marginalized by a repressive state or self-censorship? How can we approach the hidden resistance of subordinate groups in the absence of political pluralism? To overcome these limitations I propose to complement this analytical framework with some insights from visual biopolitics that help us to, first, unpack the concept of power and, secondly, grasp political logics in dissident subcultures, protest art, and creative vandalism.

The visual biopolitics approach derives from the concept of power as radicalized in Foucauldian studies. Michel Foucault (Citation1978) suggested that power should not only be seen as a restrictive force or “power over,” but also as a disciplining and enabling “power to.” Power does not appear only in episodic instances of “sovereign” acts of domination, which negatively characterize it as an instrument of coercion (Foucault Citation1995). However, various forms of powerFootnote3 can be identified as diffused in discourses, knowledge, and specific “regimes of truth,” which altogether make sense of how the population should live, and thus positively shape and regulate the processes of self-survival in an autonomous regime (Foucault Citation1978, 139). This nexus of power and knowledge is what Foucault (Citation2008) saw as a symptom of the “governmentalization” of the collective body, will and action through the administration of physical and mental health, sexuality, childbirth, and nutrition. Such a transfer of decision-making authority to experts implies not only a collective regulation of individual bodies but also a depoliticization of the guidelines to be followed. Biopolitics thus illuminates the involvement of disciplinary power in the construction of a collective social identity, that is, when human bodies move together and form a unity, which in fact represents a naturalized and technocratic mechanization of people’s everyday lives.

Contemporary biopolitical scholarship (Makarychev and Medvedev Citation2015; Makarychev and Yatsyk Citation2017; Kalinina Citation2017; Gurova Citation2021) encompasses all semiotic domains of human corporeality and human production (e.g., fashion) to analyze how power operates in a depoliticized and seemingly ideologically neutral way. Meanwhile, the visual aspects of biopolitics bring to the fore all the potential “forms of sign- and meaning-making” (Makarychev Citation2021, 53) that are involved in the governance and self-discipline of the population through the organization of its public space, the administration of new normality, and the symbolization of acceptable stereotypes. I argue that as a field of inquiry, visual biopolitics expands the analytical spectrum to detect social and political logics—in our case, the non-verbal forms of manifestation and subversion of the officially proclaimed narrative in the totalizing settings.

On the one hand, a visual biopolitical perspective allows us to see through the ritualized behavior and mannerisms in officially sanctioned space and detect manifestations of nonconformist culture and hence camouflaged political agency. While people’s compliance with the hegemonic order tells us about the depoliticized character of the social logics that they follow, any form of resistance to or disruption of the hegemonic order denotes a political stance and agency in relation to the structures of governance. On the other hand, the visual biopolitical analysis helps us to grasp such patterns of hegemonically normalized conduct as:

Predictability, periodization, and repetition, which are associated with the life cycles of rest and productivity (i.e., eating, sleeping, working, and leisure habits).

Standardization, stereotyping, and institutionalization, which are conditioned by the rigidity of the regime, the hierarchy of authority, and the subordination to norms.

Regularity in location and appearance, as well as in forms of expression and stylization, which exposes homogeneity and the minimal inconsistency, revealing a technical way of implementing orders.

On the contrary, any “deviant” sociocultural practice, as well as any discrepancy with universally accepted rules, involves a symbolic power to build a self-stance that denotes creativity and uniqueness of action. The highly symbolic qualities of non-verbal communication, which is not limited to images and graffiti but includes all possible ways of semiotically reshaping urban space, hold the potential for the emergence of a new discursive positivity that can challenge the existing hegemony. Moreover, the scale and intensity of the presence, the frequency of occurrence, the singularity and the creative potential of these semiotically coded forms of dissent can be seen as an indication of the nature and strength of people’s protest mood in a non-democratic environment.

In sum, by considering these non-verbal forms of counter-conduct and their characteristics, the visual biopolitics approach bridges political studies and semiotics, thus increasing the potential of an analytical examination of a homogenized society in which conformity and self-censorship become dominant mass attitudes under conditions of state repression. This methodological perspective addresses the question of social formation by observing both hegemonic and subversive forces and provides tools for examining social antagonisms in detail and clarifying the current state of political struggle.

METHODS OF DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

In this section I explain the way I combine ideas from post-structuralist discourse theory and visual biopolitics to analyze political phenomena in today’s authoritarian Russia. Post-structuralist theory does not include a specific method of data analysis. Instead, as David Howarth and Yannis Stavrakakis (Citation2000) correctly point out, researchers are free to choose tools and instruments that help to explain the political nature of the phenomena under consideration and provide a critical take on it. Basically I intend to use both accounts of social antagonisms and their non-verbal representations to analyze the hegemonic and subversive discourses around the Russian invasion of 2022.

My case study, then, concerns Russia, where the authoritarian regime creates a special environment for the formation and deployment of political logics. There the war against Ukraine is portrayed as “Russia’s special military operation in Donbas,” the Donbas region actually being part of Ukraine. The official position of Russia’s establishment and its bureaucratic apparatus is fully consistent with the president’s decision to “help Russian-speaking residents of Ukraine in the fight against Nazism” by conducting a “special military operation” in that neighboring country. In a nutshell, in today’s Russia it is unlawful to call the military activities in Ukraine a war and to demand its cessation (OVD-Info Citation2022). This controversy splits Russian society into two oppositional camps, unequal in terms of supporters and critics. The population is encouraged to express support for this “special operation.” Meanwhile critics of the military offensive in Ukraine are becoming pariahs, as they are marginalized by the public and criminalized under newly passed legislation on “fake news” about the Russian army (Clark Citation2022).

In this regard I propose to consider the Russian case of social antagonism as an implicit conflict about a very sensitive issue. In this instance one side has the right to speak loudly, while the other is quelled by socio-psychological pressure and legal abuse. To explore both sides of this conflict—the hegemonic and subversive voices—I have taken an innovative approach to the collection of data. First, following Gramsci (Citation1971), I assert that political leadership is based not only on state coercion and the economic centrality of the ruling class but also on popular consensus, which is ensured through ideological unity in the cultural terrain. Consequently political logics unfold in culture and by cultural means. Both hegemonic and subversive voices strive to dominate public space, creativity and symbolic meanings; however, these forces are a priori unequal, due to the authoritarian rules of the game. Therefore we cannot compare their intensity, visibility and quality but must consider their characteristics separately.

Secondly, I understand subversion to be the hidden and semiotically coded oppositional voices expressed in the form of non-verbal anti-war statements, acts, graffiti and installations. The hegemonic side of the social antagonism can be represented by various forms of support for and ritualistic reproduction of the official discourse, including non-verbal forms of expression such as public events, designs, and choreographic performances. My study therefore focuses on the visual representation of the Russian internal social antagonism over the war, in several metropolitan areas: St Petersburg, Ekaterinburg, Perm and Moscow.

The data set—mages of visual forms of pro- and anti-war statements—was sourced from six public Telegram channelsFootnote4 and one official Instagram accountFootnote5 between Feb. 24 and Aug. 24, 2022. The Instagram account of the Russian Ministry of Defense includes a decryption of the key letters (Z and V) of the official propaganda. The selected Telegram channels combine images of pro- and anti-war agitation uploaded by channel users from across the country. In addition I did YandexFootnote6 searches and selected the top 200 images for “за победу 2022” (for victory 2022), as well as the top 100 search results for the hashtags #своихнебросаем (#wedon’tleaveoursbehind), #победа (#victory), #ZаПобеду (#ForVicotory). Overall the data set comprises 17,966 images, of which around half were selected for examination, coded, and analyzed by the author. In addition to the basic methodological framework the collected data and their analysis were saturated with the personal observations of my colleague from Ekaterinburg and my relatives from St Petersburg, as well as some insights from the latest research on the topic. I relied particularly on Alexandra Arkhipova’s folklore and anthropological research findings and Dmitry Pilikin’s arts studies (Arkhipova Citation2022a; Bumaga Citation2022).

CASE DESCRIPTION

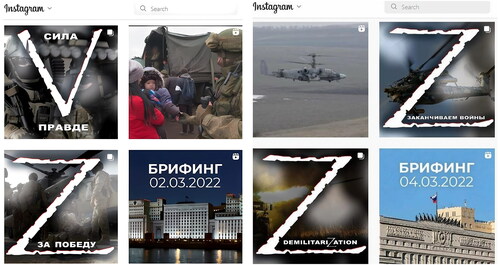

In March 2022 social media exploded with the rapid proliferation of mysterious “Z” and “V” symbols used by people in Russia and beyond as a way of showing support for Russian invasion of Ukraine (Coalson Citation2022b; Kerley and Greenall Citation2022). Eventually it turned out to be Russia’s propaganda campaign,Footnote7 but several factors contributed to its mythologization and viral spread. First, the mystification surrounding its emergence attracted the attention and curiosity of the public abroad (including some who might have remembered the popular film Z, directed by Costa-Gavras in Citation1969). Secondly, the unclear origin created the impression of civilian support for the Russian operation in Donbas. The third factor was the extensive dispute about the meaning of these symbols. Already in Feb. 2022 these letters were spotted on Russian military vehicles moving along the Ukrainian borders (Patteson Citation2022). But their meaning remained unclear. In early March the mystery was partially solved. The Instagram account of the Russian Ministry of Defense () simply linked the Latin letters Z and V to official slogans of the “special operation” without further explanation. The Ministry of Defense did not provide any etymology or justification. Moreover the decryption offered has not been officially confirmed by Russian authorities (News.Ru Citation2022). In fact those officials endowed the propagandistic symbols with political power, leaving an interpretation to state media professionals and so-called experts of the prehistoric Rus’ alphabet (Kovalev et al. Citation2022).

Figure 1 Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation. 2022. “The letters Z and V replace Russian Cyrillic counterparts, and their meanings are suggested by the phrases: Sila V pravde—“Strength is in truth”; Za pobedu—“For victory”; and Zakanchivaev voiny—“We are ending the wars” (from left to right and from top to bottom).” Instagram, March 2-3, 2022. https://www.instagram.com/p/CanFwqyM5m9/ and https://www.instagram.com/p/Car-4Ulgse1/.

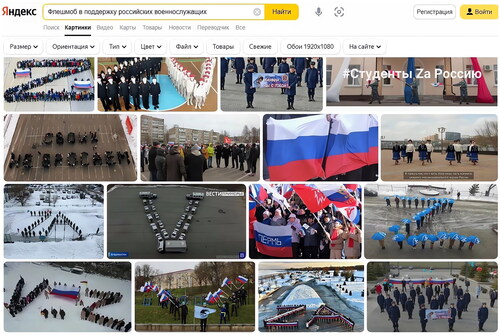

At least two implications follow. On the one hand, these symbols made up the core of the “Zvastika” discourse, performing a public demonstration of loyalty to the leadership as well as a cultural mobilization of mass support for the government’s decisions. The symbols instantly became widespread due to their state-sponsored visual dominance in space and time, creating worldwide an impression of total support for the Russian troops. Z symbols appeared everywhere: on outdoor surfaces—banners, windows, walls and doors—of public transport, administrative buildings, educational and cultural premises, even individual’s cars. Numerous news stories (Fedorenko Citation2022; Kozlova Citation2022; Hrudka Citation2022) have reported how elderly people, public sector workers, children, youth sports teams and art groups have repeatedly been involved in “Z flash mobs” and “V patriotic events” (). Universities faced administrative pressure both in student dormitories and at campus areas (DOXA Citation2022). On the one hand, instructors were ordered to sign letters of support and students to participate in the Z movement. On the other hand, the university administration recommended that scholars refrain from opposition activities and the dissemination of political comments in their social networks. In addition, musicians and artists were forced to arrange performances with a “Z background” (Tubridy Citation2022).

Figure 2 Yandex. n.d. “Yandex search results by a key phrase: ‘Flash mob in support of Russian servicemen’.” Russian search engine Yandex. Accessed April 12, 2022. https://yandex.ru/images/search?from=tabbar&text=%D0%A4%D0%BB%D0%B5%D1%88%D0%BC%D0%BE%D0%B1%20%D0%B2%20%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%B4%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B6%D0%BA%D1%83%20%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%81%D0%B8%D0%B9%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D1%85%20%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%BD%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BB%D1%83%D0%B6%D0%B0%D1%89%D0%B8%D1%85.

At the same time, this massive adherence to the hegemonic discourse at once collided with the resistance of civil counter-movements. As early as March 13, 2022, anti-war rallies were being violently suppressed across the country, and some 15,000 people were detained (OVD-Info Citation2022), pushing the protests from public assembly politics to the dimension of cultural and individual subversion.

At first the persistence and individual creativity of the opposition eclipsed the dull and ritualistically standardized forms of official propaganda, but soon became marginalized and expunged from the public gaze. People were detained and fined for individual protests holding a blank sheet of paper or with a package of sausages that contained the word mir (peace) in the name of the product. In today’s Russia any form of creative resistance to the “special operation” is therefore regarded as a dangerous symptom of extremism, falsification of the nation’s history, and “discreditation of the Russian army.” The total elimination of independent media and social media occurred simultaneously, with the enforcement of control over order in the streets, public events and individual actions too (Troianovski and Safronova Citation2022). In Putin’s regime the method of selective repression has always been preferred over the introduction of ideological censorship. Selective repression—such as the most absurd show trial of a teenager who plotted to blow up the FSOFootnote8 office in the Minecraft game (The Guardian, Feb. 10, Citation2022), or that of artists who established the “Party of the Dead” (Dasha et al. Citation2022), and thus offended against religious beliefs (Chernyshova Citation2022)—is less expensive yet quite effective in keeping people’s activism under cover, as individual cases of criminalization are presented on prime-time state television.

This has led to a surge of anti-war initiatives on Telegram channels in the summer of 2022, allowing people to act anonymously while communicating with a wide audience. Telegram is the last island of media freedom that RoskomnadzorFootnote9 has so far failed to shut down. The publication of such information in Russian is unlawful, however (Meduza Citation2022a). As a result, these online forms of resistance and their offline manifestations in Russia are not featured prominently in national or international media coverage. As noted at the start of the paper, this might contribute to an impression of a fascist Russia. Therefore the following section attempts to fill this gap and reveal some aspects of the Russian social antagonism over the “special operation” by exploring a few anti-war Telegram channels and their significance in the political struggle. I will first discuss displays of pro-war propaganda, and then turn to an analysis of anti-war resistance.

FINDINGS

Biopolitical Optics of Hegemonic Practices

The pro-war demonstrations considered in this paper produce a straightforward, ubiquitous but static and repetitive discourse resembling a sermon or exhortation. Since the early spring of 2022, all facades in many regions of Russia have been emblazoned with official Z banners with the laconic Russian slogan #WeDoNotLeaveOursBehind. My colleague from Ekaterinburg used a local neologism to ziguet to describe the ubiquitous presence of the Z and V symbols across the city. Such an intimidating omnipresence of Z would surely shock foreigners. Working in Moscow in April 2022, the long-time BBC editor there, Steve Rosenberg (Citation2022), accurately dubbed “Russia a parallel universe, an Orwellian” one. Indeed, all of Russia’s public spaces, especially in Moscow, have been rebranded with the symbol “Z,” which gives the impression of some other country with a different order and alien way of life. Undoubtedly at the beginning of the patriotic mobilization, this “Z-brandification” had the same effect on Russians too but, I would say, not for long. Together, time, the reduced engagement activities in the summer, and the propaganda saturation led to public oblivion and indifference, for which there is some evidence, such as a dramatic fall in pro-war public performances across the country.

According to observations of my informants from Ekaterinburg and St Petersburg, Z flash mobs faded over the summer of 2022, and patriotic banners gave way to military recruitment advertisements. The Z signs adorning official buildings and public transport are the only reminder of the recent “Z-ification,” the meaning of which often confuses older people. Obviously administrative enforcement does not work when schoolchildren and public sector employees are on vacation, and there is no one to line up in a Z formation. Random cases of individual expressions of the Z symbol have been reported in the media (e.g., NTV Citation2022) as they often lead to unhappy accidents, such as broken car windows within Russia or broken noses for wearing Z-branded T-shirts outside Russia. Thus most people prefer to stay out of the mainstream of patriotic mobilization, engaging in mimic rituals when necessary, and go about their usual business of survival in a harsh economic environment.

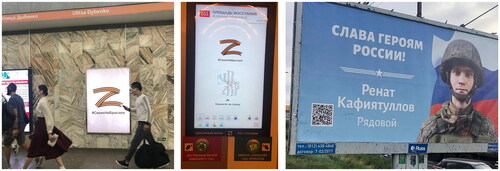

Post-structuralist discourse theory provides us with analytical tools for considering a certain social formation at a particular historical moment. Social logics are taken for granted and can be visually detected by their biopolitical characteristics. These hegemonic practices help us to grasp how a particular social formation operates within accepted conventions and legalized rules. For example, the emblematic Z signs and other “patriotic” materials are styled in the bicolor St George’s ribbon and the tricolor Russian flag respectively (). This standard, repetitive, and rather dull form of expression, which appears regularly in certain public sites,Footnote10 represents the officially sanctioned ways and places of supporting and “glorifying the heroes of Russia” (, image on the right). To put it differently, it is completely normalized and sometimes even fashionable to wear and proudly display these colors, signs and canonical stylistic details. At the same time, any display of disobedience marginalizes the individual as an abnormal and disruptive element in the mechanics of official truths.

Figure 3 Photos of two-color Z posters at metro stations in St Petersburg (from left to right: Ulitsa Dybenko, and Ploshad’ Vosstania), and a typical three-color outdoor banner in St Petersburg (right) (Photos by Svetlana Lakostik, Aug. 2022).

Furthermore the massive numbers of people lined up to form V or Z shapes in open spaces in daylight (), indicate the involvement of the authorities in the management of these forms of expression. Such a regularity in location and appearance can be explained by a strategic consideration on the part of the authorities to stage these group performances in conditions suitable for proper drone photography, and to use this illustrative evidence of “public engagement” for official reporting or media coverage. Finally, the rapid rise of massive pro-war rallies in the spring of 2022 followed by their absence in the summer can be linked to Russian productivity cycles: half of the working population, as well as pensioners and students, spend their summers in the countryside, far from the control and disciplinary measures of the state administration. Apparently, the Russian masses are not so keen on sacrificing their bodies for the sake of the “special operation” in the temporary absence of economic control.

Visual Optics of Counter-Hegemonic Practices

Unlike social logics, political logics account for antagonisms in which hegemonic signifiers, rules and social norms are contested. Here I intend to demonstrate the ambiguous character of the Russian social formation by showing what lines of public confrontation and their contested signifiers have emerged following the invasion in Feb. 2022.

Images sourced from five opposition Telegram channels formed the bulk of my analysis. Two channels, namely “Feminist Anti-War Resistance” and “The ‘Spring’ movement,” can be characterized as serving organizational functions. They disseminate methods and practical information on how to (1) display political agency creatively online and offline, (2) participate in the anti-war movement or democratic legislative petitions, (3) identify signs of subversion, and (4) resist political persecution. These movements co-operate with the human rights organization Agora, anti-war communities (e.g., the All-Russia Students Anti-War Initiative, http://clck.ru/dWGuj), oppositional projects (e.g., Media Partisans #NoWar, https://t.me/mpartisans), New Russia (https://www.instagram.com/ russiaforfreedom/), Soft Power (https://t.me/myagkaya_sila_ru), analytical projects (e.g., OVD-Info), and media channels (e.g., DOXA). Both movements have an extensive regional network of Telegram channels through which they maintain and shape the form and appearance of the ongoing public sabotage. The Visual Protest Guide 3.0 (Vesna Citation2022), for instance, describes various ways of expressing an oppositional position in a semiotically attractive but safe, anonymous and nonviolent manner. The most inventive forms of resistance include (1) toy vigils, (2) anti-war messages on banknotes and price tags, and in copies of the dystopian books by George Orwell and Evgeny Zamyatin,Footnote11 and (3) informative messages about the war losses attached to abandoned children’s toys, personal items, and miniature graves. Nevertheless the various anti-war guides (Meduza Citation2022b) suggest the form but not the content of protests. The meaning always comes from the grassroots, from the participants.

As this study aims to understand the contested signifiers of the social antagonism, it takes into consideration a wider scope of data obtained from other Telegram channels whose key function is sharing. These four channels—“Protest Petersburg,” “Not painted over yet,” “Visual Protest,” and “Super”—represent a selection of images of pro- and anti-war statements received from followers. The last two channels, for instance, were launched in March 2022 and collected around 10,000 and 2,000 photos respectively from more than 130 locationsFootnote12 inside Russia. The images depict “screaming walls,” “green ribbon signs,” “spontaneously laid flowers,” and “improvised toy memorials,” which reveal glimpses of political logics in their non-verbal way as they signify cultural forms of sabotage against the dominant silence and conformity. These initiatives represent individual protests and collective resistance in their hidden, anonymized and implicit forms. Displaying an anti-war stance, these images simultaneously function as a means of communication, “group formation and mobilization” (Makarychev Citation2021, 52). By circulating them, the Telegram channels convey common solidarity, the recognition of similar political positions, group belonging and anti-establishment criticism among participants.

The data analysis reveals two key lines of confrontation, which concern the “special operation” and “political repression” and Russian society politically split into two camps. One camp is the positive “us”: the true patriots loyal to the government and regime. The other camp is the negative “them”: “national traitors,”Footnote13 vandals and extremists. The key contested signifiers around which the visual battle of meanings unfolds are as follows.

President Putin. The personality of the “guarantor of the Constitution”Footnote14 symbolizes the necessity of Russia’s “rescue mission” in Ukraine. The anti-war acts and statements refute Putin’s authority, to which the official propaganda very often appeals. Putin’s role as the savior and defender of the “Russian World” is visually and verbally subverted by such statements as “Putin – Zlo” (Putin is evil), “Putin vrag” (Putin is an enemy), “Net Puijne” (a neologism that implies “No to Putin’s f*cking war”), “Putler Kaput” (a neologism suggesting “Putin-Hitler Die”), and “Hvatit vrat” (Stop lying) ().

Figure 4 A collage of images of anti-war statements concerning the topic of “Putin” from several Telegram channels (from left to right: “Putin = Terror”; “Peace”; “Putin-Hitler is not an illuZion”).

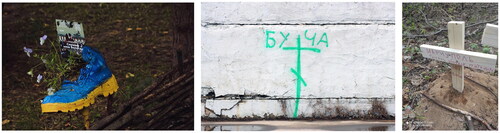

Invasion of Ukraine. The meaning of the “special operation” as a rescue mission to save children and oppressed people from Nazis is challenged by informative and performative illustrations of the actual outcomes of the Russian war crimes such as the civilian casualties in Bucha, Mariupol, and other destroyed cities, as well as by inconvenient questions about the human and financial losses of the Russian army ().

Figure 5 A collage of images of anti-war acts showing the “war horrors in Ukraine” from several Telegram channels (from left to right: a memorial cross for Mariupol with “5,000 innocent deaths”; a notice pleading to stop the killings, saying “While you are reading, children are dying in Ukraine. 240 children have died in Ukraine since the war started”; graffiti stating “War is”).

Public attitude to the “special operation.” The counter-hegemonic discourse questions the social poll result that 65 percent of Russians support the war (FOM Citation2022) in two ways (). The first is to express support for Ukraine by such statements as Svobodu Rossii, Mir Ukraine (“Freedom to Russia, peace to Ukraine”), Cvety luchshe pul (“Flowers are better than bullets”), My trebuem Mira (“We demand peace”), and Saratov ne ziguet (“The City of Saratov doesn’t go along with Z”).

Figure 6 A collage of images of anti-war acts expressing the attitude toward the “special operation” from several Telegram channels (from left to right: a green ribbon with the message “you are not alone”; a sticker saying “Russians don’t want war”; graffiti picturing the Ukrainian flag against a bleeding Z slogan stating “For ours”).

The second is to appeal to people’s conscience and reason through statements such as Rossia nesvobodna (“Russia is not free”), Ochnis’! (“Wake up!”), Nas mnogo, ne molchi (“We are many, don’t be silent”), Sovest’—cena prikaza (“Conscience is the price of order”), Rossia ne Putin, Rossia eto vy (“Russia is not Putin, Russia is you”), My silnee Zla (“We are stronger than the Z evil”), and Golovu sebe denacifirui (“De-nazify your head”).

Results of the special operation (). The officially proclaimed goal of defeating the Nazis in Ukraine becomes less effective when confronted with the important question Zachem? (“What for?”) and other more down-to-earth graffiti screaming from walls in streets, including messages such as Za smert’ (“For death”), Voina Zlo (“War is evil”), A ty otmoesh’sia? (“Will you wash this clean?”), and Pochem budushcee? (“How much does the future cost?”). The imitation of the propaganda Z letter in subversive contexts changes its positive connotations of “national pride” and “support for the Russian soldiers” into negative ones of “evil,” “death,” “fraud,” and “lies.”

Figure 7 A collage of images of anti-war acts revealing the outcomes of the “special operation” from several Telegram channels (from left to right: a shoe in Ukrainian colors; a graffiti cross in memory of the Bucha massacre; a memorial cross for the Mariupol shelling).

In sum, such representations of anti-war resistance constitute a latent and semiotically encrypted but vibrant, dynamic, and creative discourse. First, despite state repression and public censorship (BBC Citation2022), the anti-war resistance continues with unquenchable intensity and inspiration. The number of uploaded photos shows that dozens of new individual statements appear in public space every day. The average lifespan of anti-war graffiti is very short: as visual artists from St Petersburg note, sometimes it may be a day or a couple of hours (Meduza Citation2022c). Secondly, counter-hegemonic demands are produced and disseminated in all possible forms and places. This creates “hope” (Bumaga Citation2022) that one is recognized, understood, and possibly united with those close to one but not visible.

This hope, which keeps many Russians active and sane despite oppressive isolation and public marginalization, points to an opportunity for the fragmented society to come together on common grounds. What is common here is the awareness of the horror and the responsibility that concerns everyone in the country. In this instance the sense of unity is political in nature. People do not come together because it is the easiest strategy of adaptation—to be part of something bigger, to be like everyone else, to go with the flow, and not waste time asking where we are going—in other words, to reproduce the hegemonic social logics. On the contrary, people join the opposition movement because they want to bring about change, find others with similar views, and want to be active, critical and subversive of the authoritative power relations. People wish to voice their political agency and exercise their political will. This is the first step in collective mobilization, which can lead to the emergence of a political dimension of social relations.

In many respects the current opposition movement is completely different from what it was before in Putin’s Russia. It is hidden yet visible everywhere. It is underground yet recognizable. It is massive but does not have a hierarchical organization. It is anonymous yet very personal. This is a new set of political logics in the arsenal of Russian activism. The anti-war campaign, for instance, launched by Russian feministsFootnote15 who stay anonymous for security reasons, is very strong in its patterns of mobilization, consolidation, horizontal networking, and omnipresence both online and offline. Its “Feminist Anti-War Resistance” Telegram channel never goes off the air as it is moderated by various activists who take turns to keep it running around the clock. Like the rest of the examined Telegram channels, Feminist Anti-War Resistance provides feedback within ten minutes, thus acting as a civil platform for mutual communication and cooperation. Of course, the effectiveness of these anti-hegemonic discursive practices against Putin’s repressive apparatus is highly questionable. Though, who knows—even the Wrocław dwarfsFootnote16 were harbingers of the fall of the communist hegemony in Poland (Stein Citation2017).

CONCLUSIONS ABOUT THE EVOLVING Z-IFICATION OF RUSSIA

This article has investigated the state of Russian society amid the ongoing assault on Ukraine that began in February 2022. The study has focused on the case of the social antagonism between the hegemonic (pro-war) and subversive (anti-war) forces over a Russian “special operation.” The official discourse tends to dominate both the offline and online space and create a conformist environment to influence the “silent majority” (Pastukhov Citation2022), which has historically been apolitical in this country and submissive to its government despite rising resentment and discontent among the masses. By keeping this silent majority away from mainstream politics, the Kremlin has for many years succeeded in maintaining its power and reducing the costs of the mobilization of the masses. Since March 2022, the state-sponsored Z movement has become a biopolitical strategy of patriotic mobilization. It aims to unite the national mind and body within the limits of the official narrative of a rescue mission to “demilitarize” and “de-Nazify” Ukraine, which is used to justify the brutal invasion of the neighboring country. This research has illustrated that despite their obvious lack of meaning—or “alternative universalism,” as Alexandr Morozov (Kurilla et al. Citation2022) puts it—the Z signs effectively mark the discourse of power/truth behind the narrative of Russia’s crusading mission. The visual dominance of the Z reality is a powerful message that creates an atmosphere of fear and disciplines the masses to follow the hegemonic rule. While the strategy does not aim to activate political participation among Russians, it succeeds in creating an impression of wide-scale bottom-up support for the “special operation,” while at the same time maintaining collective indifference. As Jeremy Morris (Citation2022b) puts it, “yes, there is mass indifference, but there is little enthusiasm” about the war in Ukraine.

Contributing to this argument, my study has produced evidence from a visual biopolitics perspective. The data analysis has shown that the pro-war propaganda is intense and intimidating but lacks creativity, randomness or political will. The standard slogans and copy-paste graffiti do not attract attention and inspire nothing but performances of rituals and ceremonial behavior in today’s Russia. In this respect the tacit acceptance of the war and public submission to the state propaganda can be seen as the hegemonic social logics. From this at least two conclusions can be drawn. First, on the surface, in the state-sanctioned public sphere, these forms of behavior are most visible inside and outside Russia, contributing to the vision of a fully totalized Russian society. Secondly, the ritualized and subaltern character of these patterns of social behavior says little about the actual attitudes, demands and preferences of individuals, since their voices are muted by their conformity to the Z Unitarianism. However, it says a lot about such structural factors as domestic repression and forms of exclusion that shape an extremely dangerous environment for the expression of dissident views about the war. In sum, the current social logics in Russian cities characterize completely apolitical and hegemonized behavior—do as others do and you’ll be safe.

To present the other side of the social antagonism I have examined a set of empirical data obtained from several public Telegram channels that produce, accumulate and communicate the underground discursive practices of Russian resistance. The data show that the key propaganda strategy of justifying military action in the neighboring country through presidential power is highly questioned by citizens. In this respect the anti-war acts contribute to this social controversy by causing discomfort and anxiety in passersby. The target audience of the oppositional voices is not the establishment but the general audience, the “silent majority.” The current ideological struggle is being fought over the common sense of the indecisive, frightened and voiceless population of Russia.

In this sense the anti-war graffiti and non-verbal forms of protest exemplify the political logics of Russian resistance, which has increased dramatically in the summer of 2022 against the backdrop of rapidly intensifying state repression after February 2022. In contrast to the “defensive mobilization,” which shows as ignorance, denial, passivity and other forms of “involuntary consolidation” (Morris Citation2022c). In response to the state propaganda, the new forms of protest mobilization are characterized by individual activism that strives to find its way to collective recognition and build a coalition of diverse voices.

Despite the visible totalization of the Russian society there are forces struggling with the regime and opportunities for the creation of a new frontier based on counter-hegemonic popular demands. The anti-war protests create a vibrant and dynamic discourse, taking various forms and occupying various spaces. People are joining the opposition movement to bring about change and exercise their political will, which creates potential for collective mobilization. The current opposition movement is massive but lacks hierarchical organization and is anonymous though very personal. One example is the feminist anti-war resistance campaign, which is strong in mobilization, consolidation and horizontal networking. The actual development of collective mobilization, however, and the possible institution of a new social formation are questions for further research. The anti-war resistance in Russia continues despite state repression and public censorship.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Kone Foundation (Koneen Säätiö), application 202109235. I am also grateful to all the owners and managers of the selected Telegram channels who kindly gave their permission to use the visual content for this study.

I want to extend my sincere thanks to Dr Ekaterina Grishaeva, Visiting Scholar and Alexander von Humboldt Research Fellow at the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen, and my mother Svetlana Lakostik, for sharing their observations on the intensity and scale of pro- and anti-war protests in Ekaterinburg and St Petersburg during the summer of 2022.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tatiana Romashko

TATIANA ROMESHKO is a PhD candidate at the University of Jyväskylä, in Finland. Since 2010 she has taught at various universities in St. Petersburg, and at Tampere University, Helsinki University and the University of Jyväskylä. Her research interests are Russian politics, cultural policy, cross-border cooperation, governmentality, and post-structural discourse theory. At present, she is finishing doctoral research on the emergence of state cultural policy in Putin’s Russia. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

1 For more on this academic debate, see Coalson (Citation2022a).

2 For more about the meaning of Z, V and O letters of Russia’s propaganda, see Barry (Citation2022).

3 Foucault defines two of them. The first is “an anatomo-politics of the human body,” which characterizes disciplinary procedures of power within “systems of efficient and economic controls.” The second is “a biopolitics of the population,” which depicts a series of “interventions and regulatory controls” of biological processes such as birth, healthcare, and longevity (Citation1978, 139; his emphasis).

4 The names are given in their original form in the Russian language: Протестныи˘ Петербург https://t.me/nedimonspbinf; Пока не закрасили https://t.me/streetart_locations; Движение «Весна» https://t.me/vesna_democrat; Феминистское Антивоенное Сопротивление https://t.me/femagainstwar; Видимыи˘ протест https://t.me/nowarmetro; Супер https://t.me/romasuperromasuper; Минобороны России https://t.me/mod_russia.

5 The official Instagram account of the Russian Ministry of Defense (Минобороны России; https://www.instagram.com/mil_ru/).

6 (https://yandex.com) is the largest search engine in Russia and a state-sanctioned alternative to Google.

7 As Alexandra Arkhipova (Citation2022b) explains, the same tactic of a “seemingly grassroot movement” was used by Putin’s government during the mobilization of mass support for the Crimea annexation in 2014. The Kremlin-sponsored national-patriotic, orange-and-black St George’s ribbon was massively circulated among public servants, schools, and state-run institutions to commemorate the Soviet contributions to the victory in World War II and link these historical sentiments with “returning freedom to Crimea by bringing it back home.” For more on the topic, see (Patriotic Mobilization in Russia 2018).

8 The Federal Guard Service of the Russian Federation (FSO); http://government.ru/en/department/115/

9 The Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media of the Russian Federation; https://eng.rkn.gov.ru/about/

10 Bus stops, official road signs, maps for various means of public transport, street banners, and indoor information boards in public buildings.

11 The authors of two well-known dystopian social science fiction novels Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and We (1921).

12 According to one of the owners of the Telegram channel. See KIT. https://mailchi.mp/getkit.news/nasmnogo?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=sharing&utm_campaign=nasmnogo

13 This wording is from a recent comment by the Russian president (Dyachyshyn Citation2022).

14 President of Russia, Kremlin; http://en.kremlin.ru/structure/president

15 Feminist Anti-War Resistance. 2022. “Russia’s Feminists Are in the Streets Protesting Putin’s War.” Trans. by Anastasia Kalk and Jan Surman. Jacobin, Feb. 22; https://jacobin.com/2022/ 02/russian-feminist-antiwar-resistance-ukraine-putin

16 The Wrocław dwarfs have both historical and symbolic value. Historically they recall the Orange Alternative, a political protest movement in the 1980s that used humor and wit as a form of resistance against the communist government in Poland. Today the dwarfs are seen as a symbol of the movement and the city’s history of political activism. Symbolically the dwarfs represent the spirit of the city and its inhabitants. They are playful, imaginative and often mischievous, reflective of the character of the people of Wrocław.

REFERENCES

- Arkhipova, Alexandra. 2022a. “Telegram Channel “(Ne)zanimatel’naja antropologija.” ((Non)entertaining anthropology); https://t.me/anthro_fun

- Arkhipova, Alexandra. 2022b. “Vmesto Travy [Instead of Grassroots].” (Non)entertaining anthropology, March 18; https://t.me/s/anthro_fun?q=ВМЕСТО+ТРАВЫ+

- Barry, Orla. 2022. “No Z allowed!” The World, April 25; https://theworld.org/stories/ 2022-04-25/no-z-allowed-some-european-countries-move-ban-symbol-used-promote-russia-s-war

- BBC. 2022. “‘Net vojne’: kak v Rossii nakazyvajut za pacifistskie nadpisi” [“No to war”: How pacifist inscriptions are punished in Russia], March 30; https://www.bbc.com/russian/news-60926083

- Budraitskis, Ilya. 2022. “From Managed Democracy to Fascism: Putin’s Imposition of Obedience and Order on Russian Society.” Tempest, April 23; https://www.tempestmag.org/2022/04/from-managed-democracy-to-fascism/

- Bumaga. 2022. “‘Nadpisi nesut nadezhdu, chto ne vse ljudi v gorode konchenye’. Kak strit-art stal glavnym instrumentom antivoennyh protestov” [“The Inscriptions Carry the Hope That Not All People in the City Are Finished.” How Street Art Became the Main Tool of Anti-War Protests], June 21; https://paperpaper.ru/nadpisi-nesut-nadezhdu-chto-ne-vse-lyudi/

- Carpentier, Nico. 2018. “Diversifying the Other: Antagonism, Agonism and the Multiplicity of Articulations of Self and Other.” In Current Perspectives on Communication and Media Research, edited by Laura Peja, 145–162. Bremen, Germany: Lumière.

- Chernyshova, Varvara. 2022. “‘Hvatit voevat’, mirnye zhiteli ne voskresnut’. Kak zapugivajut ‘Partiju mjortvyh’” [“Stop Fighting, Civilians Will Not Be Resurrected.” How to Intimidate the “Party of the Dead”]. Sever.Real, Sept. 12; https://www.severreal.org/a/kak-zapugivayut-partiyu-myortvyh-/32028694.html

- Clark, Torrey. 2022. “Russia Criminalizes Sanctions Calls, ‘Fake News’ on Military.” Bloomberg News, March 4; https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-04/russia-to-punish-sanctions-appeals-and-fake-news-on-military?leadSource=uverify%20wall

- Coalson, Robert. 2022a. “Nasty, Repressive, Aggressive—Yes. But Is Russia Fascist? Experts Say ‘No.’” Radio Freedom, April 9; https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-repressive-aggressive-not-fascist/31794918.html

- Coalson, Robert. 2022b. “Special Operation Z: Moscow’s Pro-War Symbol Conquers Russia – And Sets Alarm Bells Ringing.” RadioFreeEurope, March 17; https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-ukraine-letter-z-fascist-symbol/31758267.html

- Dasha, Filippova, Pavel Mitenko, Anastasiia Spirenkova, Antonina Stebur, and Vera Zamyslova. 2022. “Party of the Dead: Necroaesthetics and Transformation of Political Performativity in Russia.” ArtMargines, Feb. 3; https://artmargins.com/ party-of-the-dead-necroaesthetics-and-transformation-of-political-performanity-in-russia-during-the-pandemic/

- DOXA. 2022. “Vuzy okazyvajut davlenie na studentov iz-za vojny s Ukrainoj: hronika” [Universities Put Pressure on Students because of the War with Ukraine: Chronicle], Feb. 25; https://news.doxajournal.ru/novosti/-okazyvayut-davlenie-na-studentov-iz-za-vojny-s-ukrainoj-hronika/

- Dyachyshyn, Yuriy. 2022. “Putin Lashes Out at ‘National Traitors’ with Pro-Western Views: Who Does Putin Consider Traitors?” Moscow Times, March 18; https://www.themoscowtimes. com/2022/03/18/putin-comments-on-the-fifth-column-a76987

- Ernesto, David, and García Doell. 2022. “A Fascist Regime Looms in Russia. Moscow Sociologist Greg Yudin on Putin’s Unleashed Power Apparatus and the political motives behind the attack on Ukraine. Interview.” Analyse & Kritik: International, April 1; https://www.akweb.de/politik/putin-war-in-ukraine-a-fascist-regime-looms-in-russia/

- Fedorenko, Valeria. 2022. “KreZtovyj pohod detej Zet-patriotizm v Primor’e probralsja v detskij sad, k udjegejcam i dazhe na l’dinu” [Crossroads of Children Z Patriotism in Primorye Made Its Way to the Kindergarten, to the Udege, and Even to the Ice Floe]. Novaya Gazeta, March 14; https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/ 2022/03/14/kreztovyi-pokhod-detei

- FOM. 2022. “Dominanty. Pole mnenij. Vypusk 8 Rezul’taty ezhenedel’nyh vserossijskih oprosov” [Dominants. The Field of Opinion. Issue 8 Results of Weekly All-Russian Surveys], March 4; https://fom.ru/Dominanty/14695

- Foucault, Michel. 1978. The History of Sexuality. Volume I. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, Michel. 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of a Prison, Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Foucault, Michel. 2008. The Birth of Biopolitics. Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979, edited by Michel Senellart and trans. by Graham Burchell. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Glynos, Jason, and David Howarth. 2007. Logics of Critical Explanation in Social and Political Theory. London, UK: Routledge.

- Golosov, Grigory. 2022. “Fascist Russia? Grigory Golosov’s Response to Timothy Snyder’s Article.” Riddle, May 30; https://ridl.io/fascist-russia/

- Gramsci, Antonio. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. London, UK: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Guardian. 2022. “Russian Teenager Jailed over ‘Minecraft Plot to Blow up Virtual Spy HQ.’” The Guardian. Feb. 10; https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/10/russian-teenager-nikita-uvarov-jailed-over-minecraft-plot-to-blow-up-virtual-spy-hq

- Gurova, Olga. 2021. “Many Faces of Patriotism: Patriotic Dispositif and Creative (Counter-)Conduct of Russian Fashion Designers.” Consumption Markets & Culture 24 (2): 169–193; doi: 10.1080/10253866.2019.1674652.

- Hall, Stuart. 1988. The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left. London, UK: Verso.

- Howarth, David, and Yannis Stavrakakis. 2000. “Introducing Discourse Theory and Political Analysis.” In Discourse Theory and Political Analysis, edited by David R. Howarth, Aletta J. Norval, and Yannis Stavrakakis, 1–23. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Hrudka, Orysia. 2022. “Why Have Z and V Become Russia’s Symbols of War against Ukraine?” Euromaidanpress, March 24; https://euromaidanpress.com/2022/03/24/ why-do-z-and-v-become-russians-pro-war-symbols/

- Kalinina, Ekaterina. 2017. “Becoming Patriots in Russia: Biopolitics, Fashion, and Nostalgia.” Nationalities Papers 45 (1): 8–24; doi: 10.1080/00905992.2016.1267133.

- Kerley, Paul, and Robert Greenall; 2022. “Ukraine War: Why Has ‘Z’ Become a Russian Pro-War Symbol?” BBC News, 7 March; https://www.bbc.com/news/ world-europe-60644832

- Kovalev, Alexey, Andrey Percev, Andrey Seraphimov, and Il’a Shevelev. 2022. “Bukva Z – oficial’nyj (i zloveshhij) simvol rossijskogo vtorzhenija v Ukrainu. My popytalis’ vyjasnit’, kto jeto pridumal, – i vot chto iz jetogo poluchilos [The Letter Z Is the Official (and Ominous) Symbol of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine. We Tried to Find out Who Came up with It – and Here’s What Came of It].” Meduza, March 15; https://meduza.io/feature/2022/03/15/bukva-z-ofitsialnyy-i-zloveschiy-simvol-rossiyskogo-vtorzheniya-v-ukrainu-my-popytalis-vyyasnit-kto-eto-pridumal-i-vot-chto-iz-etogo-poluchilos

- Kozlova, Darya. 2022. “(Ne)svobodnye ljudi Sibiri: Kak zhiteli Novosibirska i ego Akademgorodka vstretili ‘specoperaciju’ v Ukraine [(Un)free People of Siberia: How the Inhabitants of Novosibirsk and Its Academgorodok Met the ‘Special Operation’ in Ukraine].” Novaya Gazeta, March 2; https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/ 2022/03/26/ne-svobodnye-liudi-sibiri

- Kurilla, Ivan, Grigory Yudin, Arcady Ostrovsky, Marlene Laruelle, and Alexandr Mozorov. 2022. “Nacifikacija denacifikacii. Opravdanno li sravnenie rossijskogo rezhima s fashizmom? [Nazification Denazification. Is It Justified to Compare the Russian Regime to Fascism?].” Re:Russia, June 22; https://re-russia.org/c40568ce36e2437b986fa9e46c024abf?v=affdbe0ae65348368e32a95067e0e184&p=2b300c67747945379215bc038a309e91&pm=c

- Laclau, Ernesto. 2005. On Populist Reason. London, UK: Verso.

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 2001. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London, UK: Verso.

- Laruelle, Marlène. 2021. Is Russia Fascist? Unraveling Propaganda East and West. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Laruelle, Marlène. 2022. “So, is Russia Fascist Now? Labels and Policy Implications.” The Washington Quarterly 45 (2): 149–168; doi: 10.1080/0163660X.2022.2090760.

- Linz, Juan J. 2000. Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regime. London, UK: Lynne Rienner.

- Makarychev, Andrey. 2021. “Visual Biopolitics: Outlining a Research (Sub)Field.” Journal of Illiberalism Studies 1 (1): 51–57; doi: 10.53483/VCHW2527.

- Makarychev, Andrey, and Sergei Medvedev. 2015. “Biopolitics and Power in Putin’s Russia.” Problems of Post-Communism 62 (1): 45–54; doi: 10.1080/10758216.2015.1002340.

- Makarychev, Andrey, and Alexandr Yatsyk. 2017. “Biopolitics and National Identities: Between Liberalism and Totalization.” Nationalities Papers 45 (1): 1–7; doi: 10.1080/00905992.2016.1225705.

- Meduza. 2022a. “Protesty protiv vojny zapreshheny v Rossii. No ljudi nashli sposob vyskazat’ nesoglasie s Putinym Na ulicah po vsej strane – graffiti, listovki i naklejki, osuzhdajushhie vtorzhenie [Protests against the War Are Banned in Russia. But People Have Found a Way to Voice Their Disagreement with Putin – Graffiti, Flyers, and Stickers Denouncing the Invasion Are on the Streets across the Country].” March 2; https://meduza.io/feature/2022/03/02/protesty-protiv-voyny-zaprescheny-v-rossii-no-rossiyane-nashli-sposob-vyskazat-nesoglasie-s-putinym

- Meduza. 2022b. “Vy v Rossii, nenavidite vojnu i ne znaete, chto delat’? Gid po samym vazhnym antivoennym proektam (v kotoryh mozhet pouchastvovat’ ljuboj chelovek) [Are You in Russia, Hate War, and Don’t Know What to Do? Guide to the Most Important Anti-War Projects, in Which Anyone Can Participate].” June 23; https://meduza.io/slides/vy-v-rossii-nenavidite-voynu-i-ne-znaete-chto-delat?utm_source=telegram&utm_medium=live&utm_campaign=live

- Meduza. 2022c. “‘Ujmis’, molis’, poklonis’, nizhe sognis’’. V Permi pojavilsja strit-art o tom, kak teper’ zhit’ v Rossii” [“Calm down, Pray, Bow down, Bend down.” Street Art Appeared in Perm about How to Live in Russia Now], Aug. 4; https://meduza.io/short/2022/08/04/uymis-molis-poklonis-nizhe-sognis-v-permi-sozdali-strit-art-o-tom-kak-zhit-v-rossii

- Morris, Jeremy. 2022a. “Is Russia Fascist?” Postsocialism, May 24; https://postsocialism. org/2022/05/24/is-russia-fascist/? fbclid=IwAR0QgTZulkWTfNxXZRboOVGxtDhIztNr2jikCDurxZlAQw0WYOx0L95UurA

- Morris, Jeremy. 2022b. “On Russian War Enthusiasm, Indifference, Militaristic Sentiment, and More.” Postsocialism, Aug. 17; https://postsocialism.org/2022/08/17/on-russian-war-enthusiasm-indifference-militaristic-sentiment-and-more/

- Morris, Jeremy. 2022c. “Defensive Consolidation in Russia – Not ‘Rally around the Flag’.” Postsocialism, March 4; https://postsocialism.org/2022/03/04/defensive-consolidation-in-russia-not-rally-around-the-flag/

- Nelyubin, Nikolay. 2022. “‘No Older Russia Anymore.’ Political Scientist Vladimir Pastukhov on Sequences of the Military Operation in Ukraine.” Novaya Gazeta, June 6; https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2022/03/23/vladimir-pastukhov-operatsiia-russkaia-khromosoma

- News.Ru. 2022. “‘Ne javljajutsja oficial’nymi’: Minoborony o znakah Z i V” [“They Are Not Official”: The Ministry of Defense about the Signs Z and V”], May 19; https://news.ru/vlast/ne-yavlyayutsya-oficialnymi-minoborony-o-znakah-z-i-v/

- NTV. 2022. “Futbolka s bukvoj Z stala prichinoj skandala v moskovskoj shkole [T-shirt with the Letter Z Caused a Scandal in a Moscow School].” May 25; https://www.ntv.ru/novosti/2706994/

- OVD-Info. 2022. “No to War: How Russian Authorities Are Suppressing Anti-War Protests.” Report, March 14; https://reports.ovdinfo.org/no-to-war-en

- Pastukhov, Vladimir. 2022. “Operacija ‘Russkaja hromosoma’ [Operation ‘Russian Chromosome’].” Novaya Gazeta, March 3; https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2022/03/23/vladimir-pastukhov-operatsiia-russkaia-khromosoma

- Patteson, Callie. 2022. “World War ‘Z’? Russian Tanks with Mysterious Marking Enter Ukraine.” New York Post, Feb. 23; https://nypost.com/2022/02/23/russian-tanks-with-mysterious-z-marking-enter-ukraine/

- Reiter, Svetlana. 2022. “Sociologist Greg Yudin: ‘We Are Living in a New Era’.” Raamop Rusland, March 4; https://www.raamoprusland.nl/dossiers/stemmen-uit-de-oorlog/2044-sociologist-greg-yudin-we-are-living-in-a-new-era

- Rosenberg, Steve. 2022. “Ukraine War: The Russia I Knew No Longer.” BBC, April 22; https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-61188783

- Roshchin, Evgeny. 2022. “What is Russia, Actually? And Why Does It Matter?” Russia.Post, June 16; https://russiapost.info/politics/what_is_russia_actually

- Secker, Glyn. 2022. “Neo-Fascism, NATO and Russian Imperialism: An Overview of Left Perspectives on Ukraine – Part 1.” Counterfire, June 29; https://www.counterfire.org/articles/opinion/23294-neo-fascism-nato-and-russian-imperialism-an-overview-of-left-perspectives-on-ukraine-part-1

- Snyder, Timothy. 2022. “We Should Say It. Russia Is Fascist.” New York Times, May 19; https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/19/opinion/russia-fascism-ukraine-putin.html

- Stein, Eliot. 2017. “The Cheeky Gnomes Taking over Wrocław.” BBC Travel, Oct. 18; https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20171017-the-truth-behind-wrocaws-cheeky-gnomes

- Troianovski, Anton, and Valeriya Safronova. 2022. “Russia Takes Censorship to New Extremes, Stifling War Coverage.” New Your Times, March 4; https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/04/world/europe/russia-censorship-media-crackdown.html

- Tubridy, Mack. 2022. “Russian Musicians Speaking out against the War Face Concert Cancellations.” Russia.Post, Aug. 17; https://russiapost.info/regions/concert_cancellations

- Vagner, Volodya. 2022. “Is Russia Now Fascist? The Bucha Massacre Has Led Some to Say Yes.” NovaraMedia, April 12; https://novaramedia.com/2022/04/12/is-russia-now-fascist/

- Vesna. 2022. “Vidimyj protest”: gid 3.0 [“Visible Protest”: Guide 3.0], June 13; https://vesna.democrat/2022/06/13/kak-sdelat-protest-zametnee-polnyj-g/

- Zavadskaya, Margarita, and Aleksey Gilev. 2022. “Kakoj rezhim v Rossii na samom dele?” [What Is the Real Regime in Russia?”] KIT Medusa, June; https://mailchi.mp/getkit.news/total

FILMOGRAPHY

- Costa-Gavras, dir. 1969. “Z.” Starring Yves Montand, Irene Papas and Jean-Louis Trintignant. Paris: Reggane Films & Valoria Films; color, 127 mins.