Abstract

In Lai Xá Village, Vietnam, studio photography is the village handicraft. Counter to Walter Benjamin’s characterization of the click of a button, privileging eye over hand, but typical of many craft traditions, photographers there describe painstaking apprenticeships through which they learned to master the tools and materials of their craft. They learned to compensate for the shifting properties of light, climate, humidity, and irregular supplies of electricity, chemicals and printing paper, and adapted to changing regimes of technique and labor organization. As in many other craft traditions, apprentices often acquired their most valuable knowledge by stealth. We argue that studio photography belongs within contemporary discussions of craft as a handed, adaptive, engaged, small-scale social practice, and that craft awareness enables a richer ethnographic understanding of the work of studio photographers, both material and social.

A MODERN CRAFT

Lai Xá Village, on the northwest periphery of greater Hanoi, in Vietnam, is a Traditional Occupational Village (Làng nghề truyền thống), so recognized by the Hà Tây Provincial People’s Committee in 2003 and now the locale of a museum celebrating the history of its craft. Like other artisans in Vietnam’s Red River Delta, Lai Xá men learned their craft through genealogies of local apprenticeship in the workshops of kinsmen. As with other handicraft villages in this region, where limited agricultural land encouraged craft production as an income supplement, the skilled products of Lai Xá villagers served markets in Hanoi, the rest of Vietnam, and sometimes overseas. As with woven mats from Nga Sơn in Thanh Hoá Province, silk from Hà Đông, and ceramics from Bát Tràng, the latter two in what is now greater Hanoi, Lai Xá products were branded with good repute, the signifying ideograph lai, “come” (来), incorporated into the names of several renowned shops there. And the craft? It was photography.

PHOTOGRAPHY, A VILLAGE HANDICRAFT?

In Walter Benjamin’s much-cited essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” photography becomes his quintessential example of a modern, mechanized process yielding an infinitely reproducible product (Benjamin Citation1969). In the work of art, uniqueness is inextricable from authenticity, a part of what constitutes the “aura” of a handed work of production, even one made to replicate a prototype. For Benjamin aura disappeared in the face of mass accessibility, nowhere more explicitly than with the near-infinitely reproducible photograph, “The cathedral leaves its locale to be received in the studio of a lover of art” (ibid., 220–21). In other writing, and in contrast to the infinite replicability he saw in photography, Benjamin valorized the handed touch of the potter as the unique trace that marked each pot as distinctive, like the memory arts of the storyteller (Leslie Citation2010). The experiences of the Lai Xá photographers reveal that this characterization could in fact be extended to studio photography with respect to the skill and adaptability required for the several techniques used to generate an image (however many prints that image might generate).Footnote1

We are provoked by another of Benjamin’s assertions, possibly the most naïve words this complex thinker ever wrote: “For the first time in the process of pictorial reproduction, photography freed the hand of the most important artistic functions which henceforth devolved only upon the eye looking into a lens” (Benjamin Citation1969, 219). For Benjamin the camera was a machine that, in the manner of industrial equipment, reduced the work of the hand to a near-mechanical gesture activating more complex mechanical processes while it simultaneously privileged the work of the eye. Many of us perform this gesture on a near daily basis with the modern “camera” function on our smartphones, and the photographer’s “eye” is celebrated in books sold in museum shops (“art photography” being another ironic spin on Benjamin). The gifted eye is something the Lai Xá photographers also invoke and value. And yet anyone whose experience with a camera extends beyond “point and shoot” and bridges the analog to digital divide, much less anyone who has ever entered a darkroom, might question Benjamin’s reduction of photographic labor—as it was practised in and beyond his own time—to a simple click.

On the contrary, we will argue that the doing of studio photography, as practised from the 19th century through most of the 20th, was in critical respects not unlike the throwing and firing of a clay pot, the weaving of a textile or a basket, or the casting of a bronze piece in a mold. Our aim is to bring craft perspectives into ethnographic explorations of photography production and the ethnography of darkroom photography into the conversation about contemporary craft, a project that we consider mutually enriching to both enterprises. Our discussion here is based on the commentary of a dwindling number of Lai Xá men who learned their craft through traditional apprenticeships, as well as some younger photographers who have adapted to a changing practice. But first let us clarify what we mean by “craft.”

RETHINKING PHOTOGRAPHY AS CRAFT

Since the late 19th century handicraft has been celebrated and precariously sustained in multiple cultures as a rearguard resistance to industrial standardization, a valuing of the work of the human hand over industrial mass production even as craft practices have everywhere become subject to deskilling through the introduction of mechanized techniques and rationalized workshops. While not disputing “a great deal of historical truth” regarding the precarity of handicraft and the effort invested in its preservation, Glenn Adamson argues that “craft skill was (and is, since the process is ongoing) not simply eroded as a result of industrialization. Rather it has been continually transformed and displaced into new types of activity”; virtually anything involving a triangulation between maker, tool, and material could be considered craft (Adamson Citation2010, 2; also Becker Citation1978, 883; and Marchand Citation2016). Adamson offers a “simple but open-ended” definition of craft as “the application of skill and material-based knowledge to relatively small-scale production” enabling “us to draw connections across a much wider range of activities than the so-called ‘crafts’ themselves” (Citation2010, 2–3). This revivified and broadened view of craft has been applied productively to motor mechanics in Nigeria (Berry Citation2010), workers in a decaying Soviet-era ball-bearing factory (Alasheev Citation2010), bicycle mechanics (Martin Citation2016), a digital videography technician (Durgerian Citation2016), and some other aspects of digital technology that just might rekindle respect for “the subtleties of the hand” (McCullough 2010 [1996], 312).

The anthropologist Tim Ingold similarly emphasizes the active interplay of hand, tools and materials, but with an emphasis on the variability of material substances, each requiring a knowing and accommodating touch, and such environmental factors as the shifts in climate, wind and humidity that should be factored into the ebb and flow of production (Ingold Citation2013, 7, 17–24; also Portisch Citation2010 for weaving). A consideration of the photographer’s larger surround would also include Pinney’s “complex and changing ecology of photography” (Citation1997, 8) which for the Lai Xá photographers included challenges imposed by wartime conditions and limited sources of supplies and equipment, followed by significant changes in the processing and consumption of photography itself. All of this would require of the photographer the adaptive agility that Richard Sennett attributes to the skilled craftsman who needs must get the job done well (Citation2008).

We are not the first to have claimed a link between photography and craft. Early in the 20th century Alice Austin sought a place for photography within the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts and a recognition of darkroom technique as not only a technical but also an aesthetic practice (Riley Citation2015). Wrestling with typologies of “art” and “craft,” Howard Becker gave passing mention to photography as an innovative craft “that has gone through many revolutions in its short history” (Citation1978, 883). More often histories of photography privilege the moments, movements and enthusiasms intended to promote amateur photography as “art” in contradistinction to what the would-be artists regarded as the more standardized, less creative work of studio production (Greenough Citation1991, 265, 270; Newhall Citation1982, 147; Strassler Citation2008, 403). By contrast, in a sociological study of amateur photography in 1960s France, Pierre Bourdieu et al. note that where bourgeois amateur photographers privileged the artistic eye over technical practice, working-class photographers tended to valorize an “original relationship to technology.” They saw photography as a handed practice which they embraced as “a corrective to robotic automatism,” in effect a handicraft (Bourdieu et al. Citation1990 [1965], 126, also 108, 111, 121, 125). The Lai Xá photographers would offer a similar recognition.

An abundant literature documents the commissioning, production, and circulation of commercial photographs in colonial, post-colonial and related contexts as both products and agents of identity-assertion, composed in local studios and inflected with local desires.Footnote2 However, the rich techno-material world of the photography studio is rarely touched upon. As exceptions, Jean-François Werner (Citation1996) for West Africa and David Zeitlyn (Citation2019, 310, 325) for Cameroon offer detailed histories of the rise and decline of studio photography, with attention to the role of tools, materials, and new technologies in shaping, constraining and transforming local practice; and Werner offers a rare ethnographic reconstruction of the studio itself. Christopher Pinney describes a nearly mind-boggling array of production techniques deployed by Indian studio photographers, but his emphasis is on their photographs as products, the range of imagined possibilities embodied in their production, circulation and significance for various Indian consumers; he says far less about the work of producing them (Citation1997). Barthes, in his philosophical interrogation of the photograph, acknowledges the intersection of light, forced through an optical device, and chemical processes involving “the action of light on certain substances” (Citation1991, 10, 80), and he hails the photographer as an agentive “Operator,” but demurs from engaging this recognition insofar as “I am not a photographer, not even an amateur photographer” (ibid., 9). Strassler (Citation2010) regrets the limited knowledge of old studio practices among the second- and third-generation Chinese photographers she interviewed in Indonesia. Bourdieu and his colleagues include the voices of old professionals who lament the deskilling that accompanied new technology as it became widely accessible to amateurs, and consequently heralded the devaluation of their own work (Bourdieu et al. Citation1990 [1965]). These sentiments have been echoed in many places, including Lai Xá Village (Buckley Citation2006 for Gambia, McKeown Citation2010, 190–91 for western Cameroon). But it takes an appreciation of photographic process, and the skills required to effect it in challenging circumstances, to understand what the Lai Xá photographers and their counterparts elsewhere accomplished.

LAI XÁ PHOTOGRAPHY

As in many places, cameras arrived in what is now Vietnam in the hands of European colonials; a French photographer with a daguerreotype camera took the first known photograph there in 1845. Clément Gillet opened the first commercial studio in Saigon in 1863. As a local market grew, the French photographers were joined by overseas Chinese and local Vietnamese practitioners who mastered photographic techniques and established their own studios. Đặng Huy Trứ was the first known Vietnamese to do this in Saigon, six years after Gillet (Bennett Citation2020, 259–65). Cameramen and darkroom workers, collectively known as “worker (or artisan) photographers” (thợ ảnh), met the popular local demand for domestic and personal portraits and for the ID photographs required by colonial and then post-colonial authorities.Footnote3 The story of Lai Xá photography begins in 1909 when Mr. Nguyễn Đình Khánh, professionally known as Khánh Ký, opened Khánh Ký Photos in Hanoi’s Old Quarter and then in Nam Định, and trained the first of many generations of Lai Xá photographers.Footnote4 When his patriotic activities on behalf of the Tonkin Free School forced him into exile between 1911 and 1921, he opened studios in Toulouse and then Paris, where he taught studio photography techniques to Hồ Chí Minh. Returning home, he opened studios in Saigon and elsewhere (Hoàng Citation2004; Bennett Citation2020, 111, 128; Trang Citation2019, 6; LXPM Citation2017), while the French authorities were continuing to keep an eye on him (French Security file, from Vietnam National Archive Center no. 2, Ho Chi Minh City, copy in the LXPM). Many of Khánh Ký’s apprentices, primarily nephews and other junior kinsmen, became successful photographers, establishing studios throughout Vietnam and even beyond, training their own junior kinsmen as apprentices in expanding chains of professional lineages over multiple generations, with Lai Xá as their ancestral village (Hoàng Citation2004; LXPM Citation2017; Trang Citation2019). Today Lai Xá Village honors Khánh Ký as the founder of its photography tradition, the first teacher, and celebrates his death anniversary much as other Red River Delta villages commemorate other occupational founders as tutelary gods (thành hoàng). Khánh Ký’s photograph hangs on the walls of several village households and is paraded on a palanquin during some village celebrations (). The village photographers express gratitude to Khánh Ký for having introduced an occupation outside the back-breaking labor of agriculture and more remunerative than other Red River Delta handicrafts.Footnote5

Figure 1 A photograph of Khánh Ký, regarded as the first teacher of the Lai Xá photography craft, has a place of honor on the wall of Studio Sơn Hà. Left to right: Nguyễn Văn Huy, Laurel Kendall, studio proprietor Nguyễn Minh Nhật, and Lai Xá Photography Museum director Nguyễn Văn Thắng. (Photo by Bùi Thu Hoà)

In the new millennium Lai Xá has been recognized as a Traditional Occupational Village through a complex bureaucratic process and with the support of some key players. A photojournalist, Mr. Hoàng Kim Đáng, claims to have "discovered" Lai Xá when on assignment, and his 1979 account of the photography village was then picked up by several news services. He would subsequently publish a book-length account of Lai Xá (Hoàng Citation2004) and lend his support to efforts for official recognition of the village’s photography craft. Mr. Nguyễn Văn Thắng, with family ties to Lai Xá studio photography, became village chief there on retiring from a high-level military position in the district. He joined forces with Nguyễn Đức Căn, a member of the Hà Tây Province Department of Industry and Sub-Industry who had long been a supporter of the government’s Traditional Occupational Village program. Mr. Thắng was an active amateur art photographer, and Mr. Căn would become one; the sum of their experience and connections made a valuable alliance on behalf of this village.

There was nothing automatic about the process. An initial appeal to the Department of Industry of Ha Tay Province was unsuccessful, as the Village Photography Association had not made a convincing case against those who were arguing that a historically recent process involving modern equipment and chemistry was more like an industry than a traditional occupation.Footnote6 On a second appeal, though, with a more receptive head in the Department of Industry, advocates described the precision work involved in producing a photographic portrait and argued for darkroom photography’s greater similarity to craftwork than to a uniform industrial process. They also were able to show how, given the nature of studio photography, professional photographers needed to reside outside the village to practise the village handicraft, and that some village families had been doing this for three generations (Nguyễn Đức Căn, 6 Sept. 2022). In 2003 the Department of Industry granted the treasured recognition (Doc938 QD, July 9, 2003).

The commune then established a new oversight board to continue promoting Lai Xá photography (Doc44/2003/QD-UB 5 Dec. 2003) and recognized a sister organization for Lai Xá descendants in Ho Chi Minh City in 2008 (#21/QD-UB 3 Feb. 2008). In 2011 the board successfully appealed to the Association of Vietnamese Traditional Occupational Villages, a national NGO, for recognition of three exemplary Occupational Village Artisans (Nghệ nhân Làng nghề Việt Nam): Mr. Phạm Văn Thành, locally known as “The King of the Darkroom” (Vua buồng tối); Mr. Nguyễn Minh Nhật, for his work with natural light; and Phạm Đăng Hưng for his work with color tinting and retouching. Mr. Hưng is also locally recognized as a “Golden Hand Artisan” (Nghệ nhân bàn tay vàng). In 2011 the Association designated Lai Xá as an “Excellent Occupational Village of Vietnam” (Làng nghề tiêu biểu Việt Nam).

From early in the new millennium Mr. Thắng, the village head, worked with other supporters of Lai Xá photography to hold courses on photographic method and theory, inviting successful professional photographers to come and lecture. Here a younger generation of vender photographers, as well as some older photographers who had never heard formal theories of photography, learned techniques of lighting, composition and timing, and began to understand and describe their work as “art.” In these same years the village began its formal commemoration of Khánh Ký as an occupational founder and teacher, activities intended to make villagers aware and proud of their own history. Using funds that the village had received as compensation for land given over to development, local contributions, and contributions from Lai Xá descendants living elsewhere, the Lai Xá Photography Museum opened on 15 May 2017, celebrating photography as the village craft, and featuring the words of several photographers in the labels.Footnote7

Through this recent history of appeals, petitions and research for the museum, Lai Xá photographers were encouraged to articulate their understandings of studio photography as craft work, and they make a strong case. We began interviewing there in 2019 and continued, more extensively, in 2022 and 2023, supplemented and inspired by interviews done in 2017 by Nguyễn Văn Huy and Phạm Kim Ngân for the labels in the Lai Xá museum.Footnote8

APPRENTICESHIPS

Experiences of apprenticeship make an appropriate gateway into the photography profession, as they had done for the photographers themselves. Ethnographies of craft apprenticeship—from ceramics to artisanal chocolate—have illuminated processes of observing and doing, learning through repetition as an embodied practice, and socialization to a particular habitus of work (Coy Citation1989a, Citationb; Gowlland Citation2012, Citation2019; Kondo Citation1990; Marchand Citation2008, Citation2010, Citation2016; Singleton Citation1989; Terrio Citation2000; Wacquant Citation2005; and others). Bourdieu et al. noted the adaptability of traditional apprenticeships to the business of learning photography in French studios (Bourdieu et al. Citation1990 [1965], 154), as was also true in Lai Xá. The studio apprentices began with menial tasks such as sweeping floors, dusting, and tending the lamps. Several of the seasoned photographers described the repetitive task of polishing the glass plates used for drying prints, a process taking a full 20 minutes before the plate was so clean and smooth that the photograph would lie perfectly flat and come off evenly when dry.Footnote9 If the paper stuck the apprentice would have to repeat the tedious process of polishing. He was not punished, for it was a common happenstance, but the tedium of polishing again was penalty enough. Mr. Lương Phúc Thọ used a chemical powder to polish the glass (Lương Phúc Thọ, 1 Sept. 2022); while Mr. Vỵ holds that the bile of three pigs mixed with two-thirds of a liter of alcohol was a superior polish (despite the odor), yielding a silky-smooth photograph (Nguyễn Văn Vỵ, 2 Sept. 2022). To avoid the adverse effects of Vietnam’s humidity on the drying process, photos on glass plates would be placed vertically inside a wooden box, one meter high, lit by three or four 110-volt electric lamps.

Relieved by some newcomer from the drudgery of polishing, an apprentice would be tasked with exposing the image and processing the print through the developing solution and stop bath using chopsticks to thoroughly immerse and agitate the image. He would learn to count to precisely the right moment before removing the exposed print from the bath, adjusting his time count to compensate for overexposed negatives or for cold weather, which inhibited the development process. In the absence of an electric developing light he would monitor the emerging image by the tiny red glow of burning incense punks.

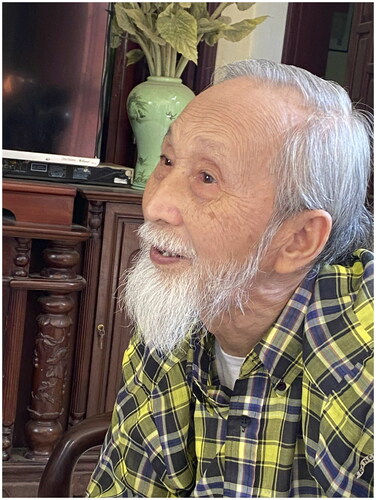

Herzfeld (Citation2004) notes that the absence of instruction is a common complaint of craft apprentices the world over, particularly where the master craftsman has little intention of revealing trade secrets to a potential rival (Deafenbaugh Citation1989; Dilley Citation1989; Goody Citation1989; Gowlland Citation2012; and Marchand Citation2010, among others). Cooper and Jiang’s (Citation1998, 50–51) description of woodworking apprentices in central China would parallel Lai Xá photography apprentices as well: generally fed, not paid, expected to perform all manner of menial tasks, while the master remained protective of “his own rice bowl,” forcing the apprentice to learn the craft almost by stealth. One Lai Xá photographer described how his own uncle would not teach him to count out the minutes needed to expose a developing photo, letting him figure it out for himself, something this photographer considers a valuable lesson: “practice and you will know” (Lương Xuân Trường, 5 Sept. 2022). But while an emergent literature on craft apprenticeships emphasizes embodied learning as an essential component of mastery, and while Lai Xá photographers themselves underscore the importance of learning by doing, the older photographers have far less celebratory reminiscences of their own experiences ().

Following common Vietnamese craft practice, most apprentices were kin, sometimes broadly defined, and with few exceptions, descendants of Lai Xá families.Footnote10 Families of non-kin would pay for an apprentice’s training while kin would not. Kinship however did not spare one from the drudgery of an apprentice’s lot or frustration over the relative absence of instruction. As Strassler (Citation2008, 416) found in her study of Chinese photographers in Indonesia, studio photography and its attendant darkroom practices were closely guarded trade secrets. Mr. Nguyễn Văn Vỵ recalled his frustration when trying to learn hand tinting from a senior apprentice. Like other apprentices he was told over and over, “Just watch what I do,” with no more specific explanation of the process; nor did he gain enlightenment sitting beside the man who did the tinting and watching him at work. He spent three years working for an old man on contract to the army. None of that man’s children had followed him into photography, yet he remained secretive about the photographic process. The exasperated apprentice threatened him, “If you don’t teach me, when you die, I will dig up your grave and take your hands.” The frightened master photographer swore that he would have his children guard his grave (Nguyễn Văn Vỵ, 2 Sept. 2022).

While the literature on craft apprenticeships suggests that close kin are often seen as lacking the necessary severity to be rigorous teachers (Coy Citation1989b; Goody Citation1989; Kondo Citation1990), many Lai Xá families mobilized long chains of relationship to place their sons, close ties that did not necessarily cushion an apprentice’s experience. Mr. Nguyễn Chí Đức, apprenticed to his father’s brother, was not spared kicks and beatings with an electrical cord while he “worked like a servant,” preparing meals, cleaning the house, locking up in the evening, and washing the developed photos. Through a close relationship with one of the senior workers he learned developing, retouching and tinting until he was able to prove his skill and become the primary studio assistant. Absolved then of menial tasks, he finally received instruction on how to take effective portraits. On receiving a substantial tip from a French client he refused to relinquish it to the studio owner and ran away. After spending the night hiding under a woodpile at the home of another Lai Xá family, he took the bus back to Lai Xá and began working as an independent vender photographer (Nguyễn Chí Đức, 4 Sept. 2022).

In the late 1950s all private studios in Hanoi were combined into government-mandated photography cooperatives or government–private joint-venture companies, while in some other places studios retained the option of remaining independent. In the cooperatives apprentices received instruction, including hands-on training, and textbooks based on professional photographers’ experiential knowledge. Even so, younger photographers described learning their craft from kinsmen since the cooperatives were organized by specialization, and anyone hoping to operate a small independent studio needed a well-rounded skill set. Mr. Nguyễn Minh Nhật described his own improvizational approach to training.

My teachers were all specialized workers, they lacked pedagogical ability, they did not know how to train. [I had to observe them myself.] Mr. Hưng is good at retouching. His father is my father’s brother so there was no secrecy, but still he was unable to describe what he did. In 1971, when I really began to practice this occupation, I already knew all the basics, but I would close the studio on Sunday and go around to the old photographers to learn more about photography. By that time they all worked in cooperatives and did sideline work at home, so I went around to their homes to learn. I studied with my uncles and aunts, blood kin, so I did not have to pay a fee. At that time [during the American war], the elderly photographers had been evacuated to the village where they received orders for retouching photographs. […] I went to visit them, observe what they did, and ask them what I didn’t know. Mr. Hưng specialized in retouching photos but was not so good at tinting and coloring. I studied tinting with Mr. Phạm Văn Chương, who worked in a cooperative in Haiphong. I went to Mr. Uyển to study how to take good photos. If you worked in a cooperative, the cooperative would assign each person one step in the process, so they would only specialize in doing one thing. I worked alone in my own studio and had to do it all. I thought that since each person was good at something, I could learn from all of them and then synthesize it. Now I’m good at everything. (Nguyễn Minh Nhật, 5 Sept. 2022)

THE DARKROOM

Mr. Hùng considers developing film the most difficult stage in photography. “This is done entirely in the dark and must be done according to precise techniques. We did it entirely by hand until travelers to Russia brought back Soviet-made film-developing tanks which provided consistent agitation, and these became available on the market" (Phạm Văn Hùng 12 Sept. 2022). Mr. Trường underscores that there was little certainty in the developing process: “There were times when, after taking a set of photos, I could not sit down to eat with my family until I had developed the films and knew they were good. Until then, my heart would pound, and I couldn’t rest” (Lương Văn Trường, LXPM Citation2017).

One of the greatest challenges for an apprentice aspiring to one day set up his own studio was mastery of the closely guarded formulas used in the developing baths. When Mr. Vỵ asked Mr. Phạm Văn Thành, the “King of the Darkroom,” how he mixed his fabled developing formula, he responded vaguely, “it’s just a pinch of this, a pinch of that” (Nguyễn Văn Vỵ, 2 Sept. 2022).Footnote11 According to Mr. Phạm Văn Hùng:

Many chemical powders were sold in grams, and it was absolutely necessary to have a formula for the correct dosage for each type and the sequence, which chemical should be added first in the process and what mixed later. One had to mix everything well, but too much mixing was also bad. The secret of studio photography was in mixing the developing chemicals just so. Not many people could do it. There were people who would buy a camera and could do all the steps [of taking a photo], but if they didn’t know how to mix chemicals, they couldn’t open their own photo studio. It usually took five to seven years of training to learn from the uncles (kinsmen) how to mix the chemicals. (Phạm Văn Hùng, 12 Sept. 2022).

Far from uniform, different studio processes, like variations in the workshop practices of other crafts, yielded distinctive products. According to Mr. Vỵ, the process at Lai Thành Studio resulted in a highly durable photograph, while Xuân Lai Studio produced a silky-smooth image.

Every evening, the couple who owned the Xuân Lai Studio shuttered their shop and prepared the chemical solutions for developing film and printing photographs. They did this in secret because they were afraid that others would steal their knowledge and they would lose their customers and livelihood. (Nguyễn Văn Vỵ, 2 Sept. 2022).

Mr. Phạm Văn Hùng learned the formula for mixing developing solutions from his father, who used a small scale to measure out the correct amounts. He wrote out the formulas for the developing fluid, stop bath, and fixing fluid and had his son practise making the mixtures until he had internalized the process. Then his father told him to burn the written formula so that it would never fall into the hands of rival studios. Neither a daughter nor a daughter-in-law could know the formula, the former because she might be tempted to help her husband, the latter because she might spill the secret to her own kin (Phạm Văn Hùng, 12 Sept. 2022).Footnote12

Photographers described some tricks of their now-vanished darkroom practice. According to Mr. Phạm Văn Nên:

Whether the photograph would last without fading depended on how well the worker washed off all the chemical traces of the developing process. In cold weather, the worker added sodium carbonate to the water so the slime on the photographs would wash off. Keep the water warm, soak the photos until they are clean, and they will last for a long time without yellowing. (Phạm Văn Nên)

Figure 3 Mr. Lương Khánh Học exhibits a well-preserved roll of negatives that he carefully washed after receiving them from the developer. (Photo by Laurel Kendall)

Mr. Nguyễn Minh Nhật, who had sought training from several different experts, described retouching as the most difficult skill in photography, requiring a good eye, patience and flexibility. “It can mean the difference between a good or bad photograph. There are hundreds of photographers in Lai Xá village but only a few of them could ever do a good retouch” (Nguyễn Minh Nhật, 5 Sept. 2022). Retouching addressed the unflattering effects of a shadow on the face, sagging skin under aging eyes, cleft lips, or blind eyes. A light pencil touch could remove a mole by effacing the white spot on a negative or make a thin face look desirably round (Lương Phúc Thọ, 1 Sept. 2022). In the case of a single blind eye, Mr. Nguyễn Chí Đức described the meticulous work of applying tracing paper to a normal eye, then flipping the tracing over the bad eye as a pattern for recreating a second normal eye (Nguyễn Chí Đức, 4 Sept. 2022). All of this required a knowledge of facial anatomy too. Mr. Phạm Đăng Hưng described varnishing the print with a mixture of avgas and resin, then working at a vertical drafting table using a 2B pencil sharpened with sandpaper to a fine needle point (Trang Citation2019, 50–52). He claims to have perfected his tinting craft by studying the coloration in American films, color illustrations in magazines, and watching the sunrise and sunset in West Lake so that he could directly experience the changing colors in nature (Phạm Đăng Hưng, LXPM). Mr. Lương Phúc Thọ perfected his craft by practising on discarded film (Lương Phúc Thọ, 1 Sept. 2022). Mr. Nên, realizing that he would need to learn from a master, won the good will of a senior retoucher by carefully filling his pipe for him (Phạm Văn Nên, 3 Sept. 2022). Some retouchers and tinters were innovative, experimenting with different resin mixes. Mr. Phạm Đăng Hưng synthesized the colors on his palate to produce a satisfactory black (Trang Citation2019, 50–52). Mr. Nguyễn Hữu Quý, a Lai Xá photographer active in Saigon, was unique in tinting his photographs with oil paint.

VARIABLE MATTER: LIGHT, LIGHTING, AND THE HUMAN FACE

The link between perspective portraiture, as developed in Renaissance Europe, and portrait photography is well known (Schwartz Citation1995, 44–45). Where Benjamin regarded the act of taking a photograph as the pressing of a button, the Lai Xá photographers, like their professional counterparts elsewhere in the world, describe an active engagement with light, shadow, form and composition to produce a beautiful photograph (Newhall Citation1982, 66–71). They speak, as other photographers do, of working with the angle of light as it varies with the time of day and with the arrangement of artificial sources, determining how to work with available light for the most beautiful results. In the 1930s most studio photographers worked with natural light in studios with dark floors to prevent reflection. Although electric lamps gave the photographer greater control over the composition of a portrait, electricity was unreliable then and the lamp wattage extremely low. Two major studios, Phúc Lai in Haiphong and Hanoi Photo at 22 Tràng Thi Street in Hanoi, developed “glass houses” (nhà kính), second floor studio spaces with curtained walls of expensive plate glass and skylights (Hoàng Citation2004, 55). Mr. Nguyễn Minh Nhật, who continues to work with natural light, described a beautiful photograph as a combination of three factors: choosing the best angle, understanding the customer’s expectations, and the lighting: “the skilled photographer works with the light to give form and depth to a customer’s nose or hair” (LXPM). He described the optimum times for capturing horizontal sunshine as 9:30 in the morning and 3:30 in the afternoon (interview, 5 Sept. 2022) (). Mr. Đinh Tiến Hải recalled the delicate process of waiting under the cloth covering of a wooden box-camera, anticipating the perfect quality of light and only then inserting the plate and manipulating the shutter (interview, 22 Nov. 2019).

Photographers described learning to compensate for a head that was too large or too small and how to minimize the wrinkles and sags in an aged face, of setting the subject at ease, and finding the optimum moment to click the shutter. “Two different persons photographed from the same angle will yield two very different results,” says the veteran photographer Nguyễn Văn Thực. In a similar vein Mr. Nguyễn Minh Nhật offered: “When you look at the face you know what to do. Beautiful eyes? Then emphasize the eyes. A beautiful nose? Then make the nose stand out. This is craft” (interview, 5 Sept. 2022). Mr. Phạm Văn Nên described emphasizing a woman’s dimples and smile and angling the camera to compensate for high cheek bones and a strong chin. Mr. Đinh Tiến Lư perfected the art of arching the developing paper during exposure to produce a more rounded face (Đinh Tiến Hải interview, 22 Nov. 2019).

The experienced photographer anticipates the desires of different customers, old people who want to be posed formally in a chair and with the full face in view, younger customers who favor close-ups of the face alone, city people who want the face slightly tilted and with the eyes looking upwards as in celebrity photographs (Đinh Tiến Mậu, LXPM, Citation2017). Phí Thị Trà Giang, who worked for many years as a vender photographer, was sensitized by her rural clients to avoid an otherwise unflattering reflection of light on hair, results they read as aged gray (interview, 9 Sept. 2022). Mr. Phạm Văn Nên described how, when the photographer recognizes that the client’s favored pose will not yield a pleasing image, he should take multiple shots to give the customer satisfactory options (LXPM, Citation2017). For Mr. Nguyễn Văn Thực, composing a portrait shot as a work of art while the manipulation of the aperture and shutter speed, requiring a sensitivity to the properties of both film and camera in relation to the available light, he said “is craft, a work of the hand but also of the head.” He had welcomed the arrival of light-meters, equipment not available early in his career (interview, 2 Sept. 2022).

ADAPTING TO THE CHANGING ECOLOGY OF PHOTOGRAPHY

With the Japanese occupation of Indochina (1940–45), photographers lost access to glass plates produced by the French Lumière Company and began using plastic (cellulose acetate) plates produced by Kodak and available from Hong Kong, lighter than the glass and consequently easier to agitate in the developing bath without any risk of scratching and more receptive to retouching.Footnote13 Old photographers describe the early 1950s as a boom time for studios producing identification photos and ancestral portraits, and with a new customer base of colonial soldiers from North Africa desirous of sending portraits home.Footnote14 But during the thirty years of conflict against France and then the United States many photographers were evacuated from urban areas to places where, of necessity, they practised their craft without electricity—which, even in good times, had been spasmodic and unreliable. Doing darkroom work without or with often unreliable electricity challenged the skills of the Lai Xá photographers. In the absence of an automated enlarger the photographer would build a small room of mud and straw with a hole in the roof to emit direct sunlight and manually suspend the negative, in a specially designed box, over the developing paper to make an exposure timed to the position of the sun (Phạm Ngọc Phúc, 9 Sept. 2022; Phạm Văn Hùng, 12 Sept. 2022). Another method was to admit light through the hole in a cardboard box, adjusting the size of the hole for different levels of exposure (Mr. Đinh Văn Bốn, LXPM). Apprentices learned to hoist the enlarger to just the right height to produce a photo of the requisite size. Large photographs required a special box that admitted a flow of horizontal light from a window or an oil lamp, a process that could only be deployed in the commodious darkroom of a major studio (Phạm Văn Hùng, 12 Sept. 2022).

Wartime conditions followed by scarcity under the controlled economy (bao cấp) until the opening-up of the market (đổi mới) in the late 1980s challenged photographers to push the limits of their skill and ingenuity in dealing with the material requirements of their craft. When film was unavailable one photographer made his exposures directly onto the developing paper and then created a device for enlarging the image (Mr. Đinh Tiến Hội, 25 Nov. 2019). Some relied on the National Film Studio as an “informal” source of surplus supply. Others spoke of cultivating relationships with students or diplomats who could travel abroad. A few admitted the obvious, that photographers were largely dependent on black market supplies of uneven quality and variable products.Footnote15 Under the controlled economy, Hungary, Russia and (then East) Germany were their primary sources, but the flow was still unstable. Darkroom technicians pushed the limits of the use-by dates on imported chemicals, and some became adept at resuscitating expired, dried-out chemicals, claiming that with proper attention they could still get satisfactory results (Mr. Phạm Thành, LXPM Citation2017). German chemicals were expensive and difficult to use, while those from Russia are remembered as cheap and easy to mix. Photographers learned the properties of developing materials from these different sources, and how different chemicals would respond to the various developing papers that might be sporadically available. Hungarian developing paper worked well in Vietnam’s humid climate; the German paper was responsive to light exposure, requiring only a count of five in the darkroom, but it yellowed quickly (Lương Phúc Thọ a.k.a. Thọ Lông, 1 Sept. 2022; Nguyễn Văn Thực a.k.a. Thực Cứ and Nguyễn Văn Thắng, 2 Sept. 2022). Good quality film was essential, but deficiencies could be compensated for by using good quality paper, when available. After 1975 some Lai Xá men who had fought in the South returned home with Japanese cameras.

From the late 1980s, color photography processed by large commercial plants gradually supplanted studio darkrooms, a global phenomenon.Footnote16 Rolls of color film rendered the old box-cameras obsolete and the cooperatives, with their vintage darkroom equipment, disappeared in the early 1990s. Photographers now maintained small private studios or worked as mobile vender photographers, either attempting to learn the new developing techniques or, more often, ferrying color film by bicycle to a development plant.

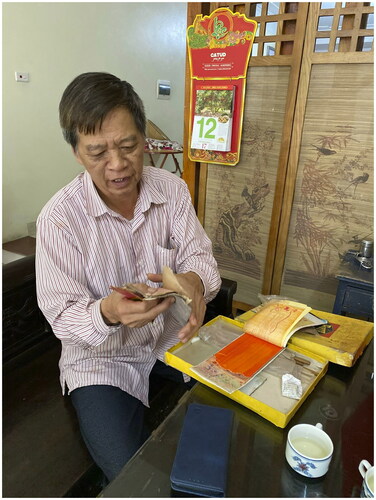

Color photography meant using precious roll film with the National Film Studio as, again, an informal source of supply. One photographer described loading empty cannisters with this re-purposed film in the dead of night. To save exposures he and other photographers stitched old, exposed film to the end of a new roll as leader, eliminating the necessity of wasting good film that would otherwise be exposed in the loading process; with the leader a photographer could get 40 good shots from a roll normally intended to provide 36 (Nguyễn Chí Đức interview, 11 Sept. 2022). When she was learning her craft in the 1990s Mrs. Phí Thị Trà Giang was tasked with adding the leaders of exposed film (interview, 5 Sept. 2022). As elsewhere, some learned to load a camera nimbly by inserting two hands into a developing bag and working by experienced touch (Lương Xuân Trường, 5 Sept. 2022) (). Phí Văn Hồng recalled how the Czechoslovakia-made “Olympus” camera he acquired in the late 1980s allowed him to take 72 shots per role rather than the usual 36, a doubling of possibility (interview, 4 Sept. 2022).Footnote17

Figure 4 Mr. Lương Xuân Trường demonstrates how he used a closed bag to load his camera without exposing the film. (Photo by Nguyễn Văn Huy)

With better economic conditions the 1990s were relatively good years for Vietnamese photographers. Some became successful mobile vender photographers, appearing at tourist sites, weddings, festivals, holidays and school class commemorations, as these activities blossomed in better times, each event yielding a potential network of new contacts. They learned to work in both the open sunlight of an afternoon wedding and the interior of a dark house, operating outside the controlled and relatively predictable conditions of a studio environment and with commercial processing for color film, independent of a studio darkroom.Footnote18 Ms. Phí Thị Trà Giang described how the kinsman who taught her the craft made her aware of the overall surround when she was at risk of posing a wedding party against a black wall. He taught her to anticipate all the details of the resulting image including the condition of the subject’s collar (interview, 9 Sept. 2022). As a woman vender photographer at country weddings, Phạm Thị Xuân would let the crowd of assembled cameramen get their shots, then move in and arrange the wedding party in studio style. She gained satisfaction when others appreciated the professional look of her compositions (interview, 11 Sept. 2022).

More recently digital photography, and its widespread deployment by amateurs, has limited the demand for professional work. When asked about the future of Lai Xá photography, photographers of all ages expressed ambivalence. Yes, the tradition was dead or dying owing to the accessibility of digital technology, the cost of renting studio space, and the opportunities now available to village children outside photography. But some are embracing the new technologies as part of the ongoing process of craft adaptability that we have been describing here. Mr. Nhật, who perfected his craft by learning different skills from his extended kin, believes that digital photography enables the skilled photographer to take maximum advantage of light and design to attain a new level of beauty; and he is not alone. Mr. Lương Xuân Trường studied art portraiture to improve his game when he began working with photoshop. Given the demand for ancestral portraits, he and others have found steady work doing digital restoration of fading photographs or altering the photographs taken of young soldiers to imply the rank and uniform they would have acquired at the time of their deaths. Some photographers have added an arsenal of new services, including videography, costume rental, make-up, and flowers for weddings. One enterprising Lai Xá couple runs an elegant studio for wedding shoots with stylish attire and ornate backdrops copied from the internet, ever attentive to the changing tastes of the younger generation.

CONCLUSION

In studio photography the resulting portrait is infinitely replicable, as Benjamin would have it, but in Barthes’ term, and like the hand-thrown pot or the hand-loomed shawl, the “This” of any one originating image—the instant of the photographic encounter –“can never be repeated existentially” (Barthes Citation1991, 4). Where Barthes’ photographic “what has been” (ibid., 85), like Benjamin’s pressing of a button, is the product of the moment of encounter, the Lai Xá photographers remind us that the finished studio portrait emerged from subsequent and complex processes. Some photographers showed us pieces of equipment—enlargers, old cameras, paint-brushes, and colors used for tinting and retouching–tools they or their fathers had used in the past and for which they felt a deep sense of personal attachment, as they recalled an active engagement of hands, tools and materials (). Studio work, like other craft operations, required embodied knowledge, the internalization of chemical formulas that must be mixed “just so,” the timing of an exposure in a chemical bath with the count measured against seasonal climatic fluctuations, taking light exposures with unreliable and mutable light, and finding ingenious dodges against a humid environment. They learned to accommodate unreliable light sources, revivify desiccated chemicals and work with papers of variable quality. These are the kinds of skill, both embodied and adaptive, that we have come to regard as the very substance of craft. Likewise the knowing eye that posed the initial shot and the hand that clicked the shutter did so with a cognizance of shifting light and shadow and a canny reading of the subject. The Lai Xá photographers practised amid Pinney’s “complex and changing ecology,” navigating hierarchies of studio practice, cooperative labor organizations and family workshops, cultivating “informal” sources for necessary materials, and later, an emerging niche for vendor photographers. Mechanical developing tanks, more sophisticated enlargers, new camera technologies, color film, and eventually digital photography and photoshop would all require adaptations in their practice, eventually spelling the end of the old studio dark-room but not of the photographer’s adaptive engagement with—in Sennett’s characterization of the craftsman—getting the job done well.

Figure 5 Mr. Phạm Văn Hùng has preserved the colored papers and brushes he used when tinting photographs. (Photo by Nguyễn Văn Huy)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the photographers who generously shared their time and memories with us. The Jane Belo Tanenbaum Fund of the American Museum of Natural History enabled Laurel Kendall’s participation in this project.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare. The proposal was submitted to the Grants and Fellowships office of the American Museum of Natural History for IRB approval which was waived because research would not involve access to private information or biological material. Subjects participated voluntarily, having been informed that the authors were researching an article, and several had already participated in the projects mentioned in Note 1. They were familiar and comfortable with—one could even say enjoyed—the interview process, and gave us signed consent to use their real names.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Laurel Kendall

Laurel Kendall, Curator of Asian Ethnographic Collections at the American Museum of Natural History, is an anthropologist of South Korea who has also worked in Vietnam and Bali. Her most recent book is Mediums and Magical Things: Statues, Paintings, and Masks in Asian Places (2021). E-mail: [email protected]

Nguyễn Văn Huy

NguyỄn VĂn Huy, Founding Director of the Vietnam Museum of Ethnology (1995–2006), Director of the Nguyen Van Huyen Museum, and has been actively working on ethnology, museum studies and cultural heritage for the last 56 years. His most recent paper is "Soviet-Style Apartment Complexes in Hanoi: Architecture and Intellectual Exchange” in An Anthropology of Intellectual Exchange: Interactions, Transactions and Ethics in Asia and Beyond, Jacob Copeman et al, eds. (2023). E-mail: [email protected]

Bùi Thu Hoà

BÙi Thu HoÀ was International Relations Officer of the Vietnam Museum of Ethnology (2002–17) and has worked as the interpreter or translator for many cultural projects and exhibitions. She has been interested in darkroom photography since childhood, and was responsible for the English labels in the Lai Xá Photography Museum (Citation2017) and the English audio guide for the Nguyen Van Huyen Museum (2019), both in Lai Xá village. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

1 Benjamin did describe the lingering auratic power of the portrait photograph: "The cult of remembrance of loved ones, absent or dead, offers a last refuge for the cult value of the picture. For the last time the aura emanates from the early photographs in the fleeting expression of a human face.” But he saw this connection as something that would soon and inevitably wither away, subsumed by the exhibition value of mass-produced images (Benjamin Citation1969, 226). Ethnography offers a wealth of counter-examples of tenaciously, sometimes creatively auratic photographs as sites of ancestor veneration (Pinney Citation1997, Sprague Citation2003), stand-in presences for ghost brides (Kim Citation2021), gurus (Pinney Citation1997), and the exiled Dalai Lama (Harris Citation2004), or as photogenic verification of spirit possession (Morris Citation2000) among many more and fascinating examples. In Vietnam too one finds auratic photography on ancestral altars, in the sometimes-ritualized respect accorded portraits of Uncle Ho and other national heroes, and as evidential material flourished by spirit mediums, but our concern here is less with the content of photographs than with the work of making them, both social and technical.

2 For example, Behrend (Citation2003); Buckley (Citation2000–01, Citation2006), MacDougall (Citation1992), Porto (Citation2004), Morris (Citation2009), Pinney (Citation1997, Citation2003), Strassler (Citation2008, Citation2010), Wendl (Citation1999), Werner (Citation2001), Zeitlyn (Citation2010) and others.

3 See Werner (Citation2001) for a discussion of the salience of the identity card image in Côte d’Ivoire and Zeitlyn (Citation2010, 459) for Cameroon. The identity photograph likewise remains an important component of official personhood in Vietnam today (Leshkowich Citation2014).

4 In his history of early Vietnamese photography, Bennett (Citation2020) gives the earlier date of 1892 for the opening of Khánh Ký’s first studio.

5 Village handicrafts typically garnered necessary but meager incomes (Gourou Citation1936, Citation1955, 195–6 cited in DiGregorio Citation1994, 112, 117).

6 In December 2000, the Kim Chung Commune People’s Committee had granted official recognition to the standing board of the Lai Xá Village Photography Association, charging them to work with the communal authorities to collect, study, and compile documents in support of recognition. The appeal was made on the basis of this work (Kim Chung Commune People’s Committee #38/2000/QD-UB).

7 On May 23, the Hanoi People’s Committee officially licensed the Museum (#2924/QD-UBND 23 May 2017).

8 The labels, translated by Bùi Thu Hoà and edited by Susan Baily, are credited to the Lai Xá Photography Museum (LXPM). We cite accounts of Lai Xá Village by Hoàng Kim Đáng (Citation2004) and Hà Trang (Citation2019) for additional background information.

9 From our interviews, but also mentioned in Hoàng (Citation2004).

10 Kinsmen were a common source of apprentices among the Chinese studio photographers active throughout Southeast Asia (Strassler Citation2008, Citation2010) and in Chinese handicraft more generally (James Watson, quoted in Herzfeld Citation2004, 63, 235 n.8). Similarly, Vietnamese craft practices have been jealously guarded by villages and within village families (Gourou Citation1955, 575–76, cited in DiGregorio Citation1994, 116).

11 Working with the National Photography Association, Mr. Thành had access to many different imported chemicals and was able to develop his own formulas, in contrast with darkroom workers in the cooperatives.

12 The work of the Xuân Lai couple, described above, runs counter to this widely accepted generalization, an instance where conjugality meshed with the interests of a small family business in ways counter to patrilineal expectation. Notably, the collaborating female partner is in the role of “wife” rather than “daughter” or “daughter-in-law.”

13 David Zeitlyn (Citation2019, 463) describes how a Cameroonian photographer similarly welcomed the plastic plates.

14 The afterlives of some of these photographs, recontextualized by a contemporary Vietnamese American artist, appeared in the New Museum’s 2023 exhibition, “Tuan Andrew Nguyen: Radiant Remembrance.”

15 Werner (Citation1996, 99, 100) notes West African photographers’ reliance on contraband film from Nigeria and the uneven quality of chemicals and paper from this source, issues that may have been more common to global histories of photography than heretofore realized.

16 Vietnam’s relatively closed economy likely delayed the transition. Buckley (Citation2006) McKeown (Citation2010), Werner (Citation1996), and Zeitlyn (Citation2019) trace the hegemony of color processing to the early or mid-1980s in their African field sites.

17 At that time, cameras manufactured in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Block were not subject to international copyright and sometimes freely borrowed brand names.

18 Werner (Citation1996), writing of West Africa, and Zeitlyn (Citation2019), writing of Cameroon, notes a similar correlation between the arrival of commercially-processed color film, the flowering of vender photography, and the decline of the old studios.

REFERENCES

- Adamson, Glenn. 2010. “Introduction.” In The Craft Reader, edited by Glenn Adamson, 1–5. Oxford, UK, and New York, NY: Berg.

- Alasheev, Sergei. 2010. “On a Particular Kind of Love and the Specificity of Soviet Production.” In The Craft Reader, edited by Glenn Adamson, 287–296. Oxford, UK, and New York, NY: Berg.

- Barthes, Roland. 1991. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Trans. by Richard Howard. New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

- Becker, Howard. 1978. “Arts and Crafts.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (4): 862–889; https://doi.org/10.1086/226635.

- Behrend, Heike. 2003. “Photo Magic: Practices of Healing and Harming in East Africa.” Journal of Religion in Africa 33 (2): 129–145; https://doi.org/10.1163/15700660360703114.

- Benjamin, Walter. 1969 [1955, 1936]. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, edited by Hannah Arendt; trans. by Harry Zohn, 217–252. New York, NY: Schocken Books.

- Bennett, Terry. 2020. Early Photography in Vietnam. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

- Berry, Sara. 2010. “From Peasant to Artisan: Motor Mechanics in a Nigerian Town.” In The Craft Reader, edited by Glenn Adamson, 263–286. Oxford, UK, and New York, NY: Berg.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, Luc Boltanski, Robert Castel, Jean-Cleade Chamboredon, and Dominique Schnapper. 1990 [1965]. Photography: A Middle-Brow Art. Trans. by Shaun Whiteside. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Buckley, Liam. 2000–01. “Self and Accessory in Gambian Studio Photography.” Visual Anthropology Review 16 (2): 71–91; https://doi.org/10.1525/var.2000.16.2.71.

- Buckley, Liam. 2006. “Studio Photography and the Aesthetics of Citizenship in The Gambia, West Africa.” Chap. 2 in Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture, edited by Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden and Ruth B. Phillips, 61–86. New York, NY: Berg.

- Cooper, Eugene, and Yinhuo Jiang. 1998. The Artisans and Entrepreneurs of Dongyang County: Economic Reform and Flexible Production in China. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Coy, Michael W. 1989a. “Being What We Pretend to Be: The Usefulness of Apprenticeship as a Field Method.” In Apprenticeship: From Theory to Method and Back Again, edited by Michael W. Coy, 115–135. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Coy, Michael W. 1989b. “From Theory.” In Apprenticeship: From Theory to Method and Back Again, edited by Michael W. Coy, 1–11. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Deafenbaugh, Linda. 1989. “Hausa Weaving: Surviving amid the Paradoxes.” In Apprenticeship: From Theory to Method and Back Again, edited by Michael W. Coy, 163–179. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- DiGregorio, Micheal R. 1994. Urban Harvest: Recycling as a Peasant Industry in Northern Vietnam. Honolulu: East-West Center Occasional Papers, Environment Series.

- Dilley, R. M. 1989. “Secrets and Skills: Apprenticeship among Tukolor Weavers.” In Apprenticeship: From Theory to Method and Back Again, edited by Michael W. Coy, 181–198. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Durgerian, Peter. 2016. “Crafting Solutions on the Cutting Edge of Digital Videography.” In Craftwork as Problem Solving: Ethnographic Studies of Design and Making, edited by Trevor H. J. Marchand, 87–94. Guildford, UK, and Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Goody, Esther N. 1989. “Learning, Apprenticeship and the Division of Labor.” In Apprenticeship: From Theory to Method and Back Again, edited by Michael W. Coy, 233–256. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Gourou, P. 1936. Les Paysans du Delta Tonkinois: Étude de Géographie Humaine. Paris: Éditions d’Art et d’Histoire.

- Gourour, P. 1955. The Peasants of the Tonkin Delta: A Study of Human Geography. Vol 2. New Haven: Yale University. (Original edition Gourou 1936)

- Gowlland, Geoffrey. 2012. “Learning Craft Skills in China: Apprenticeship and Social Capital in an Artisan Community of Practice.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 43 (4): 358–371; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1492.2012.01190.x.

- Gowlland, Geoffrey. 2019. “The Sociality of Enskilment.” Ethnos 84 (3): 508–524; https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2018.1455726.

- Greenough, Sarah. 1991. “‘Of Charming Glens, Graceful Glades, and Frowning Cliffs’: The Economic Incentives, Social Inducements, and Aesthetic Issues of American Pictorial Photography, 1880-1902.” In Photography in Nineteenth-Century America, edited by Martha A. Sandweiss, 259–281. Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum; New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams.

- Harris, Clare. 2004. “The Photograph Reincarnate: The Dynamics of Tibetan Relationships with Photography.” In Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images, edited by Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, 132–147. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Herzfeld, Michael. 2004. The Body Impolitic: Artisans and Artifice in the Global Hierarchy of Value. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Hoàng, Kim Đáng. 2004. Lai Xá – Làng nhiếp ảnh [Lai Xá – a Photography Village]. Hanoi, Vietnam: National Publishing House.

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kim, Jeehey. 2021. “Photography, Love, and the Afterlife in East Asia.” In Photography and East Asian Art, edited by Hung Wu and Chelsea Foxwell, 143–170. Chicago, IL: Art Media Resources; and Center for the Art of East Asia, University of Chicago.

- Kondo, Dorinne K. 1990. Crafting Selves: Power, Gender, and Discourses of Identity in a Japanese Workplace. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lai Xa Photography Museum (LXPM). 2017. Museum Labels.

- Leshkowich, Ann Marie. 2014. “Standardized Forms of Vietnamese Selfhood: An Ethnographic Genealogy of Documentation.” American Ethnologist 41 (1): 143–162; https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12065.

- Leslie, Esther. 2010 [1998]. “Walter Benjamin: Traces of Craft.” In The Craft Reader, edited by Glenn Adamson, 387–394. New York, NY: Berg.

- MacDougall, David. 1992. “Photo Hierarchicus: Signs and Mirrors in Indian Photography.” Visual Anthropology 5 (2): 103–129; https://doi.org/10.1080/08949468.1992.9966581.

- Marchand, Trevor. 2008. “Muscles, Morals, and Mind: Craft Apprenticeship and the Formation of Person.” British Journal of Educational Studies 56 (3): 245–271; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2008.00407.x.

- Marchand, Trevor. 2010. “Making Knowledge.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 16 (S1): Siii–S202; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2010.01607.x.

- Marchand, Trevor. 2016. “Introduction: Craftwork as Problem Solving.” In Craftwork as Problem Solving: Ethnographic Studies of Design and Making, edited by Trevor H.J. Marchand, 1–32. Guildford, UK, and Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Martin, Tom. 2016. “Making ‘Sense’ in the Bike Mechanic’s Workshop.” In Craftwork as Problem Solving: Ethnographic Studies of Design and Making, edited by Trevor H. J. Marchand, 71–86. Guildford, UK, and Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- McCullough, Michael. 2010 [1996]. “Abstracting Craft: The Practiced Digital Hand.” In The Craft Reader, edited by Glenn Adamson, 310–315. New York, NY: Berg.

- McKeown, Katie. 2010. “Studio Photo Jacques: A Professional Legacy in Western Cameroon.” History of Photography 34 (2): 181–192; https://doi.org/10.1080/03087290903361506.

- Morris, Rosalind C. 2000. In the Place of Origins: Modernity and Its Mediums in Northern Thailand. Durham, NC, and London, UK: Duke University Press.

- Morris, Rosalind C. 2009. “Photography and the Power of Images in the History of Power: Notes from Thailand.” In Photographies East: The Camera and Its Histories in East and Southeast Asia, edited by Rosalind C. Morris, 1–28. Durham, NC, and London, UK: Duke University Press.

- Newhall, Beaumont. 1982. The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art.

- Pinney, Christopher. 1997. Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pinney, Christopher. 2003. “Introduction.” In Photography’s Other Histories, edited by Christopher Pinney and Nicolas Peterson, 1–14. Durham, NC, and London, UK: Duke University Press.

- Portisch, Anna Odland. 2010. “The Craft of Skillful Learning: Kazakh Women’s Everyday Craft Practices in Western Mongolia.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 16 (s1): S62–S79; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2010.01610.x.

- Porto, Nuno. 2004. “Under the Gaze of the Ancestors.” In Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images, edited by Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, 113–131. London, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Riley, Caroline M. 2015. “Selling Pictorialist Photography as Craft: Alice Austen’s Artistic Production and Role in the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts between 1900 and 1933.” The Journal of Modern Craft 8 (3): 333–358; https://doi.org/10.1080/17496772.2015.1099249.

- Schwartz, Joan M. 1995. “We Make Our Tools and Our Tools Make Us’: Lessons from Photographs for the Practice, Politics, and Poetics of Diplomatics.” Archiviera 40: 40–74.

- Sennett, Richard. 2008. The Craftsman. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Singleton, John. 1989. “Japanese Folkcraft Pottery Apprenticeship: Cultural Patterns of an Educational Institution.” In Apprenticeship: From Theory to Method and Back Again, edited by Michael Coy, 13–30. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Sprague, Stephen F. 2003. “Yoruba Photography: How the Yoruba See Themselves.” In Photography’s Other Histories, edited by Christopher Pinney and Nicolas Peterson, 240–260. Durham, NC, and London, UK: Duke University Press.

- Strassler, Karen. 2008. “Cosmopolitan Visions: Ethnic Chinese and the Photographic Imagining of Indonesia in the Late Colonial and Early Postcolonial Periods.” Journal of Asian Studies 67 (2): 395–432.

- Strassler, Karen. 2010. “Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java.” In Objects/Histories: Critical Perspectives on Art, Material Culture, and Representation, edited by Nicholas Thomas. Durham, NC, and London, UK: Duke University Press.

- Terrio, Susan J. 2000. Crafting the Culture and History of French Chocolate. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London, UK: University of California Press.

- Trang, Ha. 2019. “A Photography Village in Vietnam/Có Một làng nhiếp ảnh Việt Nam.” Makét 1: 3–101.

- Wacquant, Loïc. 2005. “Carnal Connections: On Embodiment, Apprenticeship, and Membership.” Qualitative Sociology 28 (4): 445–474; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-005-8367-0.

- Wendl, Tobias. 1999. “Portraits and Scenery in Ghana.” In Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography, 143–155. Paris; Revue Noire.

- Werner, Jean-François. 1996. “Produire des images en Afrique: l’example des photographes de studio.” Cahiers d'études Africaines 36 (141): 81–112; https://doi.org/10.3406/cea.1996.2002.

- Werner, Jean-François. 2001. “Photography and Individualization in Contemporary Africa; an Ivoirian Case Study.” Visual Anthropology 14 (3): 251–268; https://doi.org/10.1080/08949468.2001.9966834.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2010. “Photographic Props/the Photographer as Prop: The Many Faces of Jacques Tousselle.” History and Anthropology 21 (4): 453–477; https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2010.520886.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2019. “Photo History by Numbers: Charting the Rise and Fall of Commercial Photography in Cameroon.” Visual Anthropology 32 (3–4): 309–342; https://doi.org/10.1080/08949468.2019.1637683.