ABSTRACT

We conducted a systematic review of research into transgender and gender non-conforming people’s experiences of psychological therapy. Ten studies were subjected to a thematic meta-synthesis, resulting in two analytic themes and five subthemes. One theme was concerned with participants’ experiences of how gender was approached in therapy, including experiences of it being overemphasized, ignored, or pathologized. The second theme related to participants’ views on their therapists’ identities, and their approaches to therapeutic work and social action. We argue that therapists should be mindful of issues of power in the co-creation of therapeutic relationships and that therapists should discuss with clients about whether and how gender is discussed within therapy.

Introduction

In this systematic review of the qualitative literature, we explore transgender and gender nonconforming individuals’ experiences of psychological therapy. “Transgender and gender non-conforming” (TGNC) is an umbrella term which refers to individuals whose gender identity differs to their sex assigned at birth (American Psychological Association, Citation2015). Identities under this umbrella include transgender, gender queer, and nonbinary amongst many others (Scheim & Bauer, Citation2015). At the population level, TGNC individuals experience elevated distress compared to cisgendered people (Bouman et al., Citation2017; Judge et al., Citation2014; Lefevor et al., Citation2018). Reasons for accessing therapy that might relate to gender include experiences of discrimination (Claes et al., Citation2015), marginalization (Factor & Rothblum, Citation2007), and/or distress associated with a person’s gender identity not aligning with their gendered body (Barker, Citation2017). Individuals might also access therapy as part of a pathway to to transitioning interventions. Guidelines informing “treatment pathways” for people wishing to medically transition gender suggest that psychological input may support TGNC individuals in various ways, such as through: exploration of gender identity; addressing the negative consequences of gender dysphoria and stigma; alleviating internalized transphobia; improving body image and resilience; and to enhancing social and peer support (Coleman et al., Citation2012). TGNC individuals obviously also access psychological therapy for the same reasons as cis-gendered individuals (Shipherd et al., Citation2010). White and Fontenont (Citation2019) synthesized research exploring TGNC individuals’ experiences of mental health services. Whilst some people described accepting and containing experiences, others reported stigma, discrimination, and a lack of safety within the therapeutic relationship.

Whilst it has been consistently demonstrated that the therapeutic relationship is the strongest predictor of outcomes in psychological therapy, outside of changes in a person’s social and relational context (e.g., Flückiger et al., Citation2012; Martin et al., Citation2000; Wampold, Citation2015), the experiences of TGNC individuals within therapy have not been well-researched. Relatively more consideration has been given to the experiences of other oppressed or discriminated groups within therapy, findings of which warrant consideration.

Privilege, oppression, and therapeutic relationships

More has been written about the experiences of therapy of people who experience forms of oppression other than cisgenderism (Blumer et al., Citation2013). In research with other oppressed groups, differences in identity between therapists and clients has led to clients feeling misunderstood and perceiving therapists as less helpful (Chang & Yoon, Citation2011; Kelley, Citation2015). This has resulted in calls for matching clients and therapists, based on the assumption that support should be provided by people who have first had knowledge of particular forms of oppression (Chang & Yoon, Citation2011). However, such positions have been critiqued for risking essentializing ’difference’, and for failing to recognize intersectional oppressions that can be differentially experienced by therapists and clients (Warner, Citation2009). Related debates exist concerning whether therapists should attempt to become an expert in a given domain of diversity or adopt a position of curiosity (Cecchin, Citation1987) or “not knowing” (Anderson & Goolishian, Citation1992). Some have argued that therapists who do not experience the same form of discrimination as their clients should accumulate knowledge regarding the experiences of individuals who experience oppression, in order to avoid making normative assumptions (Chang & Yoon, Citation2011; Mair, Citation2003).

Conversely it has been argued that attempts by privileged therapists to acquire knowledge about experiences of particular “types” of people can risk: development of inaccurate assumptions; reinforce therapist-client power imbalances (when a therapist claims knowledge about a marginalized identity they do not share); and limit opportunities for reflecting with the client about the beliefs, meanings, and experiences that are pertinent for them (Dyche & Zayas, Citation2001; Pon, Citation2009). Yet, claiming a non-expert position can risk obscuring what therapists bring to the therapeutic relationship; how they attend to what the client is deemed to be an expert in (Warner, Citation2009). Research suggests when working with oppressed clients, therapists may experience a dilemma in not wanting to focus unduly on identity issues whilst also not wanting to dismiss or avoid the relevance of marginalized identities for the difficulties a client may be experiencing (British Psychological Society, Citation2019).

Guidelines developed specifically for therapists working with gender, sexual, and relationship diversity emphasize the need for therapists to examine dominant understandings of gender and to reflexively engage in one’s own position in relation to this (Barker, Citation2017; King et al., Citation2007). Research exploring therapist perspectives of working with LGBT clients has found that therapists have at times not focussed on what the client wanted to focus on or have pushed the client to explore topics they did not want to discuss (Israel et al., Citation2008). Although TGNC populations are often regarded as one homogenous group, TGNC individuals hold multifaceted identities, and in many cases more than one marginalized identity or “metaminority” status (Budge et al., Citation2016). Therefore, an intersectional approach which considers multifaceted identities as a complex set of interactions is needed. It is suggested that, in recognizing intersectionality, power differentials in the therapeutic relationship can be acknowledged, observed, and thought about cautiously (Riggs & das Nair, Citation2012).

oppressed therapist-client dyads in other areas, each domain of oppression will involve unique issues which therapists and clients will need to navigate due to differing discourses and social structures. The dominance of cisgendered assumptions underpinning much of family therapy is an obvious point and includes a tendency for people to make assumptions about gender-identity on the basis of appearance (Blumer et al., Citation2013), as well as the transmission of normative gender-sex binaries through common therapeutic practices such as the creation of genograms (Barsky, Citation2020). The unique challenges faced in renegotiating identity and social norms through transitioning gender may be neglected (Thurston & Allan, Citation2018), while intersecting discourses concerning the fluidity or stability of sexuality can result in assumptions that couples will or will not remain attracted to each other as one partner transitions (e.g., Smith et al., Citation2022).

Gender identity: a contested phenomenon

The way professionals and services support TGNC people will be influenced by debates and discourses about how gender identity should be understood. Some assert the view that gender identity is innate, that a person can have a gendered identity, or brain, different to the gender that was assigned to them at birth (e.g., Bettcher, Citation2014). Some have argued that gender should be viewed as socially constructed and something that can be internalized or performed in ways that support or trouble gender binaries and gender hegemony (e.g., Butler, Citation1988). Others have put forward views that emphasize considerations of identification (Stock, Citation2021) or the internalization of oppressive patriarchal discourses in the case of people wanting to transition away from assigned female genders (Heyes, Citation2003). Further, conflicting positions have been advanced concerning the relationships between sex and gender, and the politics of privileging one construct over the other (Pilgrim, Citation2018; Srinivasan, Citation2021; Stock, Citation2021; Summersell, Citation2018).

As well as entering the public domain through debates about gendered bathrooms and participation in sports (Bartholomaeus & Riggs, Citation2017; Hargie et al., Citation2017), these differing positions have resulted in polarized disputes about the correct way to support a person accessing services for gender related distress or wishing to transition gender. Supporters of trans-affirmative approaches accept and celebrate all experiences of gender in a non-pathologizing manner (Austin & Craig, Citation2015) and encourage unconditional positive regard for TGNC identities throughout all interactions (Austin et al., Citation2017; Blumer et al., Citation2013). Others have argued that professionals might draw attention to the contested nature of gender, how people are socialized into oppressive gender hierarchies, and explore with a person their reasons for wishing to transition (Spiliadis, Citation2019). The importance of bringing discussion of gendered discourses and structures into therapy with cisgendered individuals has also been considered (Jones, Citation2012; Urry, Citation2012).

These polarized debates have resulted in people feeling silenced or unsafe to speak, whichever position one takes (e.g., Psychologists for Social Change, Citation2021; Srinivasan, Citation2021; Stock, Citation2021; Vandenbussche, Citation2021). Given that different discourses exist in relation to gender identity, it is acknowledged that therapists and clients may enter the therapeutic encounter holding different views toward TGNC identities (Brown et al., Citation2018) and on what may or may not be helpful regarding a discussion of gender in therapy (Brown et al., Citation2018).

Rationale, positionality, and aims

Previous reviews have highlighted how clients from oppressed groups can encounter discrimination or unhelpful experiences within therapy (e.g., Chang & Yoon, Citation2011; Mair, Citation2003). However, research into how this affects TGNC individuals’ experiences of therapy has not been systematically reviewed to our knowledge. Because other oppressed groups have experienced mistrust, invalidation, and pressure to discuss unwanted topics in therapy, it is important to understand how TGNC individuals experience therapeutic relationships.

Our positionality is important to present for readers to understand the lens of our interpretations (Madill et al., Citation2000) as well as our rationale for undertaking the review (Warner, Citation2001). We are both white, middle class, heterosexual clinical psychologists with training in systemic approaches. We recognize we are privileged with regards to gender identity. Although one of us [GM] experimented briefly with performance of gender during adolescence, neither of us have experienced significant distress in relation to our gender identity. We either identify as or would be identified as cisgendered female and male respectively. We both share concerns that debates cited above have become polarized in ways that might shut down discussion within therapeutic professions and in therapy. Neither of us have specifically worked in gender services, but we have experienced dilemmas during clinical work whereby families have expressed strong positions that resulted in us becoming wary of adopting a stance of curiosity (Cecchin, Citation1987) in relation to gender. We own a position of valuing exploration of gender and gender identity but recognize that such a position could risk replicating oppression or result in a person feeling invalidated; that some individuals will come to therapy with certainty about their gender identity and sense-making of this and, as a result, therapists should not impose exploration. Our interest in conducting this literature review was to learn from research on first-hand accounts of TGNC individuals’ experiences of therapy in order to support navigation of these tensions within clinical work.

Method

Search process

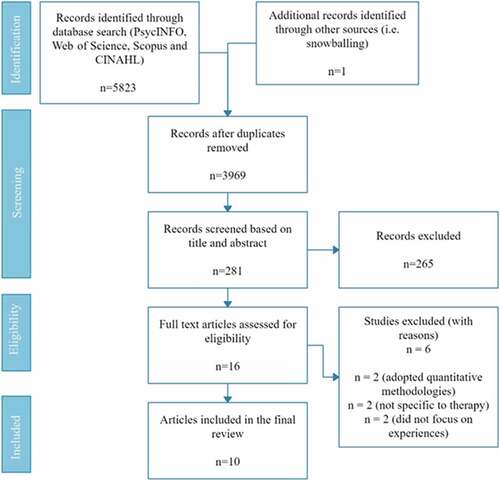

We developed search terms for a systematic search following initial scoping searches. On the 3rd of July 2020, an electronic search of four databases was undertaken: PsycINFO, Web of Science, Scopus, and CINAHL. The SPIDER tool (Cooke et al., Citation2012) defined inclusion and exclusion parameters. This tool provides a systematic way of searching for qualitative research studies to ensure rigor by defining key elements of qualitative research questions.

Initial searches yielded 5,823 results after being limited (where possible) to peer-reviewed qualitative studies written in the English language. We then exported the search results into Mendeley, and duplicates were removed. After title and abstract screening, 16 articles were read in full and screened against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Ten articles were deemed to meet the criteria and were included in this review. Reasons for exclusion included studies focussing on therapists’ experiences of therapy and studies focussing on experiences of gender services but not specifically therapy experiences. The detailed search process is depicted in .

Studies were included in the review if they adopted a qualitative methodology. Qualitative methodologies are appropriate when research aims to explore people’s experiences and the meanings they make of these experiences (Lapan et al., Citation2011) and can encourage reflections and insights (H. Mason, Citation2010). Given that the review focused on people’s experiences of therapy, it was determined that qualitative studies would be best placed to answer this review question.

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (Citation2018) CASP tool was used to appraise the quality of selected articles. Debates surround whether quality appraisal should be undertaken in qualitative reviews (e.g., Carroll & Booth, Citation2015), therefore the tool was used to assess the possible impact of study quality on the findings of the review. Efforts were made to ensure there was a balance across studies in relation to their contribution to theme development. Quotes from some studies were used more frequently than others because some studies used less quotations in their data, and others had a narrow and precise focus (Harden, Citation2008).

Thematic synthesis

We used a critical realist epistemology to qualitatively synthesize the findings of the included studies, adopting Thomas and Harden’s (Citation2008) thematic synthesis approach, combining meta-ethnographic and grounded theory principles (Barnett-Page & Thomas, Citation2009). This method was selected due to the interpretive orientation that encourages reviewers to go beyond the content of the original papers to develop new understandings that ideally can be utilized to inform practice.

The research question we set out to address was as follows: “What experiences of psychological therapy are described by individuals identifying under the transgender and gender non-confirming umbrella?.” The following steps outlined by Thomas and Harden were followed:

Step 1: coding text

The entirety of the results sections of each paper was coded line-by-line based on meaning and content (see Supplementary material for example, codes). Codes were translated from one article to another, which was an iterative process. Initial codes from all of the studies were explored in relation to one another to look for similarities.

Step 2: developing descriptive themes

Similarities and differences between codes were identified, which led to grouping codes together. New codes were then developed, which captured the meaning of groups of initial codes.

Step 3: generating analytical themes

To “go beyond” the content of the original articles, the content of descriptive themes was used to infer answers to the review question, which led to the emergence of more analytical themes. This process was repeated until we concluded that the analytical themes adequately captured the initial themes and addressed the review question.

Methodological rigor

In addition to the quality appraisal of reviewed studies, a number of steps were taken to enhance methodological rigor throughout the synthesis process. Approaches such as inter-rater reliability and triangulation are not regarded appropriate quality checks for interpretative orientations to qualitative research, where researcher subjectivity is seen as not only inevitable but also necessary to develop data into coherent themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021; Madill et al., Citation2000; Willig, Citation2013). Reflexivity (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021; Madill et al., Citation2000; Willig, Citation2013) was thus privileged throughout the analysis. EC undertook the analysis but brought extracts of coding and themes at each stage for discussion with GM. Codes and themes were checked against original data for face validity and fit (as opposed to for purposes relating to inter-rater reliability). We engaged in reflective discussions to support identification of how our own identities and theoretical leanings could have influenced our interpretations, using these conversations to raise awareness of our biases and consider if alternative interpretations would offer useful insights. EC maintained a reflective journal throughout analysis as a tool to enhance reflexivity.

Results

All included studies explored TGNC individuals’ experiences of therapy or counseling and were conducted in the Global North. Two studies focussed exclusively on negative experiences (Mizock & Lundquist, Citation2016; Morris et al., Citation2020), whilst Anzani et al.’s 2019 study was concerned with positive experiences. One study was concerned with participants’ experiences of therapy focussing specifically on gender (Bess & Stabb, Citation2009) and one focussed on therapy experiences outside of gender clinics (Hunt, Citation2014). The majority of the studies did not specify whether participants were attending therapy in relation to their gender identity or for other purposes.

The thematic synthesis resulted in the generation of two overarching themes and five subthemes ().

Theme 1: approaches to gender

All studies described participants’ experiences of how their therapist approached gender within sessions. Some participants spoke about problematic ways therapists approached their gender (Gender blind and gender blinded). Others spoke of their experiences of therapists being rigid and fixed in their views, though some participants reported more positive experiences (Gender as a problem to be fixed).

Gender blind and gender blinde

The name of this theme stems from data suggesting that participants experienced therapists as either neglecting the importance of gender identities in therapeutic work (“gender blind”) or focussing on gender in such a way that individuals did not feel heard (“gender blinded”). With regards the former, participants reported experiences of therapists seeming to neglect or avoid discussion of gender. This was experienced as dismissive and caused problems for therapeutic relationships, with therapists being experienced as uncomfortable or uninterested in discussing gender.

The counselor never touched on it [gender identity]. And I had 35 sessions with him and it was hardly ever brought up. It was all to do with anxiety, solving the problems with anxiety, and I was still just as anxious when I finished as when I started (Hunt, Citation2014, p. 294)

I think the therapist being so confident that there was no reason to explore trans identity really colored the course of my mental health treatment (Mizock & Lundquist, Citation2016, p. 151)

Conversely, other participants experienced therapists as overemphasizing the centrality of gender identity and oppression within people’s lives, which sometimes left people feeling that their identity was objectified and problematized.

If I’m going to see somebody for anxiety, all they want to talk about is how it must be because I’m trans and how that must be the cause of all my problems and that’s very frustrating (Mizock & Lundquist, Citation2016, p. 151)

Therapist was a celebrated award-winning ‘trans ally’. Completely ignored my PTSD symptoms (later diagnosed with other therapists) and tried to focus on taking apart my sexual orientation (Morris et al., Citation2020, p. 897)

Some participants experienced therapists as actively dismissing, invalidating, or discriminatory. For example, participants reported experiences of therapists misgendering, ignoring preferred pronouns, and suggesting that gender variance was reflective of mental health problems. Others felt under pressure to “prove” their gender identity.

I was misgendered and belittled by my previous therapist for my gender identity … He also told me that to him I was a girl and there was nothing that could change that (Goldberg et al., Citation2019, p. 77)

I always made sure that I wore a skirt, … had a full face of makeup and … looked as nice and in brackets “female” as possible. There is always that thing in the transgender community that when you go to see your psychiatrist, your psychologist, your therapist, that you need to look as female and glam as possible so that they know you’re really serious about it (Applegarth & Nuttall, Citation2016, p. 70)

When participants experienced these approaches toward their gender, there was an overwhelming sense of feeling unheard and devalued. Many noted that they subsequently ended their therapy, feeling that their needs were not being understood.

Gender as a “Problem to be fixed”

When gender was considered within therapy, several participants described experiences of their therapist appearing to hold rigid and fixed views. Oftentimes participants reported being “put into boxes” that they felt reflected therapists’ own notions of gender, which were regarded as cisnormative (a discourse privileging cisgender as the norm). Some participants described experiences of their therapists pathologizing gender, conceptualizing it as “something to be fixed.”

It seemed to be, like they were trying to, having used their theories as a jumping off point. They were trying to fix my gender problem. They were trying to fix me back into what they thought it should be (Applegarth & Nuttall, Citation2016, p. 71)

[She] hinted that maybe I wasn’t trans, but a gay man in denial, [and that] trans women should also take a liking in men. I questioned saying that I felt no attraction to men, and she strongly insisted that I should try or at least try to imagine myself in a situation where a man would seduce me and see how I felt (Morris et al., Citation2020, p. 897)

Participants described feeling as though their therapists had ideas about “right” and “wrong” ways to express gender, and this seemed particularly noticeable for clients with non-binary identities who described experiences of therapists making assumptions that to be TGNC involved physical alterations to one’s body.

One therapist said she thought most trans people aren’t actually trans and that to be trans you have to feel like you were ‘born in the wrong body’ and want surgery … She said my wanting to identify as a demigirl and queer was wrong because I was really just bisexual and didn’t like being oppressed as a woman (Goldberg et al., Citation2019, p. 78)

Other participants described more positive experiences when therapists were perceived as being open-minded and not making assumptions about clients’ gender identity. Participants identified times when their therapist acknowledged that gender is not fixed, and they did not attempt to fit participants into boxes based on their ideas about how someone “should” identify.

[My therapist] asked permission to use my chosen name once I disclosed it (Anzani et al., Citation2019, p. 265)

[My therapist was] very good about checking in once [in] a while [to ask] if my gender identity has shifted at all or if my pronouns or preferred name have changed (Goldberg et al., Citation2019, p. 80)

Theme 2: therapist identity and approach

Participants sought out LGBT therapists who they believed might be more sensitive to experiences of oppression (2.1 Therapist Identity and Community Visibility). Whilst this was described as helpful by some, others reported encountering therapists with unhelpfully rigid views. Other participants spoke of the importance of the therapeutic relationship (2.2 Approaches to Therapeutic Work) and their therapist being open to challenging cisnormative assumptions being more important than the identity of their therapist (2.3 Advocating for Gender Minorities).

Therapist identity and community visibility

Some participants described helpful experiences when working with therapists who identified as LGBT. They reported that individuals who identified under the sexual minority umbrella were better able to understand their own experiences of societal oppression and struggles to be validated and accepted within various relationships.

She’s got this point of view where she’s been looked down on by parts of society too (Bess & Stabb, Citation2009, p. 269)

[The therapist] knows about coming-out issues and he knows about counterculture issues (Elder, Citation2016, p. 182)

Other participants reported feeling hurt and rejected after specifically seeking out lesbian, gay, or bisexual therapists in the hope that they would be more understanding of TGNC issues, only to experience this not to be the case.

I thought it would be better to have an LGBT counsellor, but getting deeper into my transition, a lot of gays and lesbians don’t understand what it means to be trans in the community (McCullough et al., Citation2017, p. 428)

Similarly, other participants described unhelpful experiences with TGNC therapists. Participants reported feeling that the therapist had very rigid views on what their transitioning process should look like and deviating from this was perceived by the therapist as “wrong.”

And because she herself is transsexual – I’m theorizing – she had some very definite thoughts about how things should go in a transition (Elder, Citation2016, p. 183)

Some participants reported helpful experiences when therapists, not believed to be LGBT identifying, were visible in TGNC communities. Such visibility was felt to convey understanding and support of the issues TGNC individuals face (Bess & Stabb, Citation2009; McCullough et al., Citation2017).

[Counsellor’s name] is invested in other activities that went into the community, like not just having her be a counsellor in an office but also having her be a community member as someone I can see around, within the queer community (McCullough et al., Citation2017, p. 429)

I had met her before. She had spoken at meetings. I think I met her at a [support group] meeting (Benson, Citation2013, p. 31)

For some of the few nonwhite participants, who all resided in majority-white countries, the intersectionality of “race” was also important when considering therapist identity. Some people described feeling unable to use therapy to comfortably discuss their experiences as a TGNC person who also experiences racism. For some, this led to a sense that they had to separate different parts of their identity to maintain the therapeutic relationship.

When you are transitioning, [race] is a big factor … and I feel like even if I were to go to an African American counsellor, I feel like, unless they were transgender, they would not totally understand it … that’s why I feel like sometimes you just have to split up counsellors (McCullough et al., Citation2017, p. 430)

Approaches to therapeutic work

In many of the studies, participants gave positive accounts of therapists who focussed on developing a strong therapeutic alliance. In particular, the benefits of therapists being supportive and empathic were highlighted. Feeling able to trust the therapist and feeling empowered by them were also emphasized as being conducive to positive experiences of therapy.

I would love to go back and have the same counselor now, 3 years later and do some more. It was so positive, it was really really good … he was reflecting what I was saying so that I could sort it out in my head (Applegarth & Nuttall, Citation2016, p. 71)

Whilst some participants felt understood by their therapists, this sometimes felt unsafe and resulted in feelings of vulnerability.

Part of me hated it, part of me actually quite liked it … I used to end up feeling quite violated that they knew what was going on in my head. (Applegarth & Nuttall, Citation2016, p. 71)

When participants were asked about more positive experiences in therapy, many described a lack of negative experiences as helpful. Namely, participants described helpful therapeutic experiences as a lack of microaggressions (that is, subtle or indirect discrimination toward marginalized individuals), whereby their therapist was not experienced as “disgusted” or “threatened” by them (Anzani et al., Citation2019; Hunt, Citation2014). Not being judged by the therapist, and the therapist not actively discouraging transition were also seen as conducive to useful therapeutic experiences.

I have a great deal to be grateful for and she was not threatened by me so I felt comfortable (Hunt, Citation2014, p. 293)

I will say that maybe I’m being ungrateful, because there are some therapists who are outright rejecting (Anzani et al., Citation2019, p. 264)

Advocating for gender minorities

Participants described affirmative experiences when their therapist advocated on their behalf beyond the therapy room. Individuals described occasions when the therapist used their power and position to reduce systemic barriers they had encountered. This supported people to feel empowered and enabled them to approach future barriers with increased confidence.

My counselor would write them a letter to explain the situation … what I would have to go through and how they can help me catch up. So my teachers would finally understand and work with me (McCullough et al., Citation2017, p. 428)

[The counselor] has been the only person guiding me through the nightmare of all this bureaucracy and giving me ideas for activities and meetings that actually made me feel more empowered. She put me in contact with people and other nonbinary groups I had no idea of (Anzani et al., Citation2019, p. 267)

Some participants described experiences of their therapist acknowledging and actively disrupting cisnormative practices, which they described as being very affirming. Such acknowledgments included a recognition that society imposes strict ideas regarding how men and women “should” act or look, as well as institutional practices such as legal names not reflecting someone’s identity.

She started using my preferred name right after I told her it. She was apologetic about having to use my legal name in office paperwork (Anzani et al., Citation2019, p. 265)

He’s like ‘that is so wonderful that you can be who you are’ … all this validation and affirming was so powerful. That’s what is needed … and it wasn’t like too much because there can be too much (Benson, Citation2013, p. 32)

In almost all of the studies, participants emphasized the importance of their therapists demonstrating awareness of TGNC identities and the difficulties TGNC individuals may experience. When this was evident, participants described a sense of relief that they did not have to explain their identity, and they noted that they felt more affirmed by their therapists.

When I asked one of my counselors to help me correct the position of my [chest] binder, she helped me with little hesitation and asked if I was thinking about going further in my transition (Anzani et al., Citation2019, p. 266)

He actually understood what I was actually talking about, so that was a relief to talk to someone that understood (Hunt, Citation2014, p. 293)

Conversely, when therapists appeared to lack awareness of TGNC issues this was experienced as unhelpful and left participants feeling that they were misunderstood. Several participants described a sense of having to educate their therapist about what it means to be TGNC, which they described as invalidating. Participants expressed a need for therapists to receive more training around TGNC identities.

I think that trying to find a competent, friendly therapist is a struggle and a lot of trans people don’t have a therapist that is completely aware and comfortable (Mizock & Lundquist, Citation2016, p. 151)

[The therapist] questioned whether I could be trans because the toys I played with as a child were gender neutral (Morris et al., Citation2020, p. 899)

However, some participants shared that it was not essential for their therapist to have expertise in working with TGNC clients, especially if the therapist demonstrated willingness to educate themselves. In such circumstances, participants described a sense of being unburdened by their therapist.

… She said that she was willing to like go and research it herself. And just talk about your experiences and what’s going on in your life, and if you’re talking about something that’s related to transgender that you think I should just know, or you wish that somebody would just know, just let me know, and I’ll go research it (Benson, Citation2013, p. 32)

Discussion

In undertaking this review, we aimed to explore the experiences of psychological therapy within the TGNC population. Two analytical themes and five subthemes were identified to capture TGNC people’s experiences of therapy. The first analytical theme depicted participants’ experiences of how gender was approached in therapy: sometimes it was ignored, focussed on too much, or pathologized. The second analytical theme described participants’ experiences of their therapists’ identities and approaches to therapeutic work, including the degree to which they advocated for gender minorities. We now consider theme content in relation to extant theory and literature, suggest clinical implications, and acknowledge review limitations. We argue that, as with therapeutic work with other marginalized groups, therapists need to be mindful of issues of power in the co-production of the therapeutic relationship and should discuss and reflect upon whether and how issues relating to gender are discussed within therapy.

The findings of this review highlighted that unsurprisingly, TGNC individuals find a lot of the same things helpful in therapy as cisgendered people. Therefore, it is important that an individuals’ TGNC identity is not essentialised or “othered” (Robson-Day & Nicholls, Citation2021). In particular, the value of the therapeutic relationship and a sense of being validated and understood are important for cisgender (Israel et al., Citation2008; McPherson et al., Citation2020; Timulak, Citation2007) and TGNC individuals alike. Findings also echo existing research exploring the impact of difference in the therapeutic relationship. For some participants, it was helpful for their therapist to hold an LGBT identity (it was not possible from the data to make conclusions about the relative importance of a TGNC therapist identity). However, others did not experience the understanding and validation they had expected from their LGBT therapists. In parallel with research into cultural and sexual identity differences, for some individuals a shared identity facilitated trust in the therapeutic relationship (Chang & Yoon, Citation2011; Terrell & Terrell, Citation1984), whereas for others, it was more important for therapists to convey support and understanding (Kelley, Citation2015).

Our review confirms that microaggressions commonly experienced by TGNC individuals in everyday life, including being addressed by the wrong pronouns and being pathologized (Nadal et al., Citation2012), also occur within therapeutic relationships. Experiences of gender being problematized, objectified, and overemphasized were commonly reported. This is consistent with literature relating to wider healthcare experiences, where research suggests that TGNC individuals experience their gender being overemphasized by healthcare professionals in general practice (Lindroth, Citation2016; Westerbotn et al., Citation2017) or, conversely, gender non-conformity being ignored, dismissed, or seen as a problem to be “fixed” (e.g., Blumer et al., Citation2013). Therapists may feel anxious or inexperienced in working with TGNC persons and this may mean that they lack confidence to discuss gender in therapy, or erroneously assume someone is seeking therapy for gender-related issues. This is in keeping with existing literature which has demonstrated that many clinicians are unfamiliar with TGNC issues and lack relevant training (Whitman & Han, Citation2017). These findings are consistent with the experiences of other marginalized groups. In the case of race for example, a Black client may encounter white therapists who take a “color-blind,” culturally insensitive approach, neglecting the impact of racism and cultural issues for the client (Constantine, Citation2007). Similarly, therapists working from essentialist conceptualizations of “cultural competency” risk claiming expertise in a client’s cultural background in ways that impose assumptions and leave clients feeling unheard (Dyche & Zayas, Citation2001). Yet it is also worth considering the arguments of feminists who have called for therapists to inquire about the impact of gendered discourses when working with cisgendered clients who may not have regarded such scripts as pertinent to their experiences and identity (Jones, Citation2012; Urry, Citation2012).

Clinical implications

Client experiences of microaggressions and discrimination within therapy should not be dismissed or minimized, and this review is consistent with other literature that suggests such experiences are common (Lindroth, Citation2016; Westerbotn et al., Citation2017). At the same time, it is important to recognize that some problems relating to how and if gender is talked about could relate to differences between client and therapist conceptualizations of gender identity, and the service and wider societal contexts in which a therapeutic encounter is taking place. Therapists should reflect on the assumptions and positions they align with and consider the real impact various public debates on issues such as bathroom usage and participation in sports have on those identifying as TGNC. Many therapy services operate in a context in which exploration of gender identity can be seen as running counter to the affirmative position (Ashley, Citation2018; Tomson, Citation2018; Wren, Citation2019). This could result in therapists either avoiding exploration for fear of appearing transphobic, or clients experiencing their therapist through such a lens if the client holds a view that gender identity is innate and something therapists should uncritically affirm.

However, therapists need to be mindful of power in the co-production of the therapeutic relationship and ensure clients are able to lead on whether and how gender is discussed in therapy (Warner, Citation2001). This does not necessarily mean that therapists should go along with talking/not talking about gender in ways that align with a client’s preferences. Rather, as with discussion of other difficult topics, therapists can engage clients in a discussion about how and if gender is discussed (Fredman, Citation1997; Warner, Citation2001, Citation2009), whilst also using the strength of a therapeutic relationship (c.f. Burnham’s (Citation2005) “relational risk taking”) to tentatively explore with the person whether there could be value in exploring implications of talking about gender identity in different ways. Such an approach would fit with B. Mason’s (Citation1993) position of “authoritative doubt,” which invites therapists to step away from a position of knowing how things should be, and toward a position of being open to different possibilities, working in a respectful, collaborative way.

Within the therapeutic relationship, expertise could be conceptualized as being co-created through the resources and knowledge of both the client and the therapist (Burnham, Citation2005). As Baker and Beagan (Citation2014) suggest, therapists could adopt an approach of acknowledging and creating space for clients’ identities, learning with them to facilitate shared understanding. More generally, training could focus on helping therapists to increase their understanding of competing discourses surrounding gender, gender identity, and sex (Smith et al., Citation2012), and the impact different understandings may have on the therapeutic relationship. In addition, it could be helpful to support therapists to explore their own position and biases in regard to social norms (das Nair & Thomas, Citation2012), as perceived “competency” (i.e., unquestioned knowledge about the experiences of TGNC individuals) can serve as a barrier to self-reflexivity (Pon, Citation2009).

Limitations and future directions

To our knowledge, this was the first systematic review of the qualitative literature to explore TGNC individuals’ experiences of psychological therapy. Bias in the analysis in terms of our experiences and assumptions is acknowledged but regarded as a necessary tool for interpretation (Gough & Madill, Citation2012). We attended to reflexivity by reflecting on how our experiences, understandings of gender-identity, and positioning as cisgendered therapists could have influenced interpretations of findings (Noble & Smith, Citation2015). It must be acknowledged that by focussing specifically on TGNC individuals’ experiences of psychological therapy, we may have risked over-interpreting the content of reviewed studies in terms of gender identity in ways that may parallel some of the problems participants spoke about in the subtheme, Gender Blind, Gender Blinded. More specifically, there is a danger that some experiences that are important for all therapeutic relationships might have been interpreted in ways that unhelpfully essentialize and objectify TGNC identities.

Whilst the results of this review indicate that the majority of participants want their therapists to take an affirmative stance toward preferred gender identity, with clients feeling invalidated and misunderstood when this did not occur, it is important to note that the perspectives of people who have detransitioned were not represented in the reviewed studies. There have been at least some cases of people who have detransitioned stating a wish that there had been more exploration of gender and gender identity (Bell, Citation2021), whilst others have spoken of feeling unsupported by affirmative services when wanting to detransition (Vandenbussche, Citation2021). Future research could usefully explore the ways this population would have liked gender to have been explored if they had been accessing therapy around the time of transitioning.

Experiences of non-binary clients were not well represented in the reviewed papers, and all studies were conducted in the Global North. These biases highlight clear gaps for future research given discourses concerning gender identity, sex, TGNC identities and therapy itself will all be culturally constituted (Connell, Citation2021). Further, the findings from the review do not adequately address issues of intersectionality given, for example, that the experiences of the few nonwhite participants echoed limited research into health outcomes and healthcare experiences for TGNC people who experience racism (Howard et al., Citation2019; Tan et al., Citation2017). Given the importance of considering intersecting identities (Cook et al., Citation2017; das Nair & Thomas, Citation2012; Moore et al., Citation2022), it is important to recognize the lack of intersectional perspectives such as sexuality, class, and dis/ability in the current review. Further, the possibility of different experiences for individuals transitioning to a female, male or non-binary identity were also not distinguished in the original studies, and it can be anticipated that there will be differences in experiences given the dominance of gendered scripts that shape experience (Jenkins, Citation2009; Walters, Citation2012).

Additionally, most of the reviewed studies did not state participants’ reasons for seeking therapy. It can be presumed that people would expect more of a focus on gender in therapy if their reasons for accessing services were to do with gender related distress compared with other problems. Future studies could address this limitation by focussing interviews on experiences of therapy relating to either gender or non-gender related distress. Finally, it is important to acknowledge the absence of TGNC individuals in the analysis and write-up of this review. Although both authors have attended training sessions on gender delivered by TGNC individuals and engaged with “expert by experience” literature, the absence of funding for this review presented a barrier to us being able to meaningfully explore the “fit” of our interpretations with a range of TGNC individuals. This is a significant limitation given the aim of exploring the experience of therapy from the perspective of TGNC individuals.

Conclusion

Whilst feminists have recognized the value of considering gendered discourses in therapy with all people, the ways in which gender is talked about (or not talked about) in therapy will be of particular importance for many TGNC people. Therapists should be mindful of power-differentials and open up discussion about how, when, if and why gender might be discussed, using the therapeutic relationship to reflect on ways in which different understandings might be co-explored between the therapist-client dyad. Therapists should reflect upon assumptions and different positions they and their clients might privilege concerning gender, sex, and gender-identity and think about the implications of these different understandings, both within and beyond the consulting room.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (215.2 KB)Acknowledgement

The auhtors wish to acknolwedge Selina Lock, University of Leicester, for her support in developing the search strategy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2022.2068843

References

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist, 70(9), 832–864. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039906

- Anderson, H., & Goolishian, H. (1992). The client is the expert: A not-knowing approach to therapy. In S. McNamee & J. Gergen (Eds.), Therapy as social construction, (pp. 25–39) . Sage

- *Anzani, A., Morris, E. R., & Galupo, M. P. (2019). From absence of microaggressions to seeing authentic gender: Transgender clients’ experiences with microaffirmations in therapy. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 13(4), 258–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2019.1662359

- *Applegarth, G., & Nuttall, J. 2016. The lived experience of transgender people of talking therapies. International Journal of Transgenderism, 17(2), 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1149540.

- Ashley, F. (2019). Thinking an ethics of gender exploration: Against delaying transition for transgender and gender creative youth. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104519836462

- Austin, A., & Craig, S. L. (2015). Transgender affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy: Clinical considerations and applications. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 46(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038642

- Austin, A., Craig, S. L., & Alessi, E. J. (2017). Affirmative cognitive behaviour therapy with transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Psychiatric Clinics, 40(1), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.003

- Baker, K., & Beagan, B. (2014). Making assumptions, making space: An anthropological critique of cultural competency and its relevance to queer patients. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 28(4), 578–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12129

- Barker, M. J. (2017). Gender, sexual and relationship diversity (GSRD): Good practice across the counselling professions 001. British Association for Counseling and Psychotherapy.

- Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59

- Barsky, A. E. (2020). Sexuality and gender inclusive genograms: Avoiding heteronormativity and cisnormativity. Journal of Social Work Education, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2020.1852637

- Bartholomaeus, C., & Riggs, D. W. (2017). Whole-of-school approaches to supporting transgender students, staff, and parents. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(4), 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1355648

- Bell, K. (2021, April 7th). Keira Bell: My story. Persuasion, Retrieved 12th May 2021 from https://www.persuasion.community/p/keira-bell-my-story

- *Benson, K. E. (2013). Seeking support: Transgender client experiences with mental health services. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy: An International Forum, 25(1), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2013.755081

- *Bess, J., & Stabb, S. (2009). The experiences of transgendered persons in psychotherapy: Voices and recommendations. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 31(3), 264–282. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.31.3.f62415468l133w50

- Bettcher, T. M. (2014). Trapped in the wrong theory: Rethinking trans oppression and resistance. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 39(2), 383–406. https://doi.org/10.1086/673088

- Blumer, M. L. C., Gavriel Ansara, Y., & Watson, C. M. (2013). Cisgenderism in family therapy: How everyday clinical practices can delegitimize people’s gender self-designations. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 24(4), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/08975353.2013.849551

- Bouman, W. P., Claes, L., Brewin, N., Crawford, J. R., Millet, N., Fernandez-Aranda, F., & Arcelus, J. (2017). Transgender and anxiety: A comparative study between transgender people and the general population. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1258352

- Braun, V., & Clarke, C. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- British Psychological Society. (2019) . Guidelines for psychologists working with gender, sexuality and relationship diversity.

- Brown, S., Kucharska, J., & Marczak, M. (2018). Mental health practitioners’ attitudes towards transgender people: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(1), 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1374227

- Budge, S. L., Thai, J. L., Tebbe, E. A., & Howard, K. A. S. (2016). The intersection of race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, trans identity, and mental health outcomes. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(7), 1025–1049. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000015609046

- Burnham, J. (2005). Relational reflexivity: A tool for socially constructing therapeutic relationships. In C. Flaskas, B. Mason, & A. Perlesz (Eds.), The space between: Experience, context, and process in the therapeutic relationship (pp. 1–18). Karnac.

- Butler, J. (1988). Performative acts and gender constitution: An essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), 519–531. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893

- Carroll, C., & Booth, A. (2015). Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: Is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Research Synthesis Methods, 6(2), 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1128

- Cecchin, G. (1987). Hypothesising, circularity, and neutrality revisited: An invitation to curiosity. Family Process, 26(4), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1987.00405.x

- Chang, D. F., & Yoon, P. (2011). Ethnic minority clients’ perceptions of the significance of race in cross-racial therapy relationships. Psychotherapy Research, 21(5), 567–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2011.592549

- Claes, L., Bouman, W. P., Witcomb, G., Thurston, M., Fernandez‐Aranda, F., & Arcelus, J. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury in trans people: Associations with psychological symptoms, victimization, interpersonal functioning and perceived social support. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(1), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12711

- Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., Monstrey, S., Adler, R. K., Brown, G. R., Devor, A. H., Ehrbar, R., Ettner, R., Eyler, E., Garofalo, R., Karasic, D. H., … Zucker, K. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2011.700873

- Connell, R. (2021). Transgender health: On a world scale. Health Sociology Review, 30(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2020.1868899

- Constantine, M. G. (2007). Racial microaggressions against African American clients in cross-racial counseling relationships. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.1.1

- Cook, S. C., Gunter, K. E., & Lopez, F. Y. (2017). Establishing effective health care partnerships with sexual and gender minority patients: Recommendations for obstetrician gynaecologists. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 35(5), 397–407. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1604464

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018). CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. Available via: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (17th December 2020)

- Das Nair, R., & Thomas, S. (2012). Race and ethnicity. In R. Das Nair & C. Butler (Eds.), Intersectionality, sexuality, and psychological therapies: Working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual diversity (pp. 59–87). Wiley.

- Dyche, L., & Zayas, L. H. (2001). Cross-cultural empathy and training the contemporary psychotherapist. Clinical Social Work Journal, 29(3), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010407728614

- *Elder, A. B. (2016). Experiences of older transgender and gender nonconforming adults in psychotherapy: A qualitative study. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(2), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000154

- Factor, R. J., & Rothblum, E. D. (2007). A study of transgender adults and their non-transgender siblings on demographic characteristics, social support, and experiences of violence. Journal of LGBT Health Research, 3(3), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15574090802092879

- Flückiger, C., Del Re, A., Wampold, B. E., Symonds, D., & Horvath, A. O. (2012). How central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 59(1), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025749

- Fredman, G. (1997). Death talk. Conversations with children and families. Karnac.

- *Goldberg, A. E., Kuvalanka, K. A., Budge, S. L., Benz, M. B., & Smith, J. Z. (2019). Health care experiences of transgender binary and nonbinary university students. Counseling Psychologist, 47(1), 59–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000019827568

- Gough, B., & Madill, A. (2012). Subjectivity in psychological science: From problem to prospect. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 374–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029313

- Harden, A. (2008, June 30). June. Critical appraisal and qualitative research: Exploring sensitivity analysis. ESRC Research Methods Festival. https://repository.uel.ac.uk/item/86511

- Hargie, O. D., Mitchell, D. H., & Somerville, I. J. (2017). ‘People have a knack of making you feel excluded if they catch on to your difference’: Transgender experiences of exclusion in sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(2), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690215583283

- Heyes, C. J. (2003). Feminist solidarity after queer theory: The case of transgender. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(4), 1093–1120.howard. https://doi.org/10.1086/343132

- Howard, S. D., Lee, K. L., Nathan, A. G., Wenger, H. C., Chin, M. H., & Cook, S. C. (2019). Healthcare experiences of transgender people of color. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(1), 2068–2074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05179-0

- *Hunt, J. (2014). An initial study of transgender people’s experiences of seeking and receiving counselling or psychotherapy in the UK. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 14(4), 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2013.838597

- Israel, T., Gorcheva, R., Burnes, T. R., & Walther, W. A. (2008). Helpful and unhelpful therapy experiences of LGBT clients. Psychotherapy Research, 18(3), 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300701506920

- Jenkins, A. (2009). Becoming ethical. A parallel political journey with men who abuse. Russell House Publishing.

- Jones, E. (2012). Feminism and family therapy: Can mixed marriages work? In A. C. Miller & R. J. Perelberg (Eds.), Gender and Power in Families, (pp. 63–81). Taylor & Francis Group .

- Judge, C., O’Donovan, C., Callagham, G., Gaoatswe, G., O'Shea, D. (2014). Gender dysphoria – Prevalence and comorbidities in an Irish adult population. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 5(87), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2014.00087

- Kelley, F. A. (2015). The therapy relationship with lesbian and gay clients. Psychotherapy, 52(1), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037958

- King, M., Semlyen, J., Killaspy, H., Nazareth, I., & Osborn, D. (2007). A systematic review of research on counselling and psychotherapy for lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender people. British Association for Counseling and Psychotherapy. https://www.bacp.co.uk/media/1965/bacp-research-relating-to-counselling-lgbt-systematic-review.pdf

- Lapan, S. D., Quartaroli, M. T., & Riemer, F. J. (2011). Qualitative research: An introduction to methods and designs. Jossey-Bass.

- Lefevor, G. T., Sprague, B. M., Boyd-Rogers, C. C., & Smack, A. C. P. (2018). How well do various types of support buffer psychological distress among transgender and gender nonconforming students? International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1452172

- Lindroth, M. (2016). “Competent persons who can treat you with competence, as simple as that” – An interview study with transgender people on their experiences of meeting health care professionals. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(23–24), 3511–3521. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13384

- Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712600161646

- Mair, D. (2003). Gay men’s experiences of therapy. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 3(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140312331384608

- Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P., & Davis, M. K. (2000). Relationship of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta‐analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 430–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.438

- Mason, B. (1993). Towards positions of safe uncertainty. Human Systems, 4(3–4), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/26344041211063125

- Mason, H. (2010). Qualitative methods from psychology. In I. Bourgeault, R. Dingwall, & R. De Vries (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative methods (pp. 193–211). SAGE Publications.

- *McCullough, R., Dispenza, F., Parker, L., Viehl, C. J., Chang, C. Y., & Murphy, T. M. (2017). The counselling experiences of transgender and gender nonconforming clients. Journal of Counseling and Development, 95(4), 423–434. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12157

- McPherson, S., Wicks, C., & Tercelli, I. (2020). Patient experiences of psychological therapy for depression: A qualitative metasynthesis. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02682-1

- *Mizock, L., & Lundquist, C. (2016). Missteps in psychotherapy with transgender clients: Promoting gender sensitivity in counseling and psychological practice. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(2), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000177

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(1), 264–269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003–4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- Moore, I., Morgan, G., Welham, A., & Welham, A. (2022). The intersection of autism and gender in the negotiation of identity: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Feminism & Psychology, 095935352210748. https://doi.org/10.1177/09593535221074806

- *Morris, E. R., Lindley, L., & Galupo, M. P. (2020). “Better issues to focus on”: Transgender microaggressions as ethical violations in therapy. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(6), 883–915. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000020924391

- Nadal, K. L., Skolnik, A., & Wong, Y. (2012). Interpersonal and systemic microaggressions toward transgender people: Implications for counseling. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 6(1), 55–82.

- Noble, H., & Smith, J. (2015). Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evidence Based Nursing, 18(2), 34–35. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102054

- Pilgrim, D. (2018). Reclaiming reality and redefining realism: The challenging case of transgenderism. Journal of Critical Realism, 17(3), 308–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2018.1493842

- Pon, G. (2009). Cultural competency as new racism: An ontology of forgetting. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 20(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428230902871173

- Psychologists for Social Change (2021, June). When the professional is political and personal: Queer psychologists reflect on debating gender identity within the profession. www.psychchange.org/blog/when-the-professional-is-political-and-personal-queer-psychologists-reflect-on-debating-gender-identity-within-the-profession

- Riggs, D. W., & das Nair, R. (2012) In R. das Nair, & C. Butler (Eds.), Intersectionality, sexuality and psychological therapies: Working with lesbian, gay and bisexual identity (pp. 9–30). BPS Blackwell .

- Robson-Day, C., & Nicholls, K. (2021). “They don’t think like us”: Exploring attitudes of non-transgender students toward transgender people using discourse analysis. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(14), 1721–1753. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1667161

- Scheim, A. I., & Bauer, G. R. (2015). Sex and gender diversity among transgender persons in Ontario, Canada: Results from a respondent-driven sampling survey. The Journal of Sex Research, 52(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.893553

- Shipherd, J. C., Green, K. E., & Anramovitz, B. A. (2010). Transgender clients: Identifying and minimizing barriers to mental health treatment. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 14(2), 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359701003622875

- Smith, A., Morgan, G., & Robertson, N. (2022). Experiences of female partners of people transitioning gender: A feminist interpretive metasynthesis. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2022.2050863

- Smith, L. C., Shun, R. Q., & Officer, L. M. (2012). Moving counseling forward on LGB and transgender issues: Speaking queerly on discourses and microaggressions. The Counselling Psychologist, 40(3), 385–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000011403165

- Spiliadis, A. (2019). Towards a gender exploratory model: Slowing things down, opening things up and exploring identity development. Metalogos Systemic Therapy Journal, 35(1), 1–9.

- Srinivasan, A. (2021, September 6). Who lost the sex wars? Fissures in the feminist movement should not be buried as signs of failure but worked through as opportunities for insight. Annals of Activism. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/09/13/who-lost-the-sex-wars

- Stock, K. (2021). Material girls. Why reality matters for feminism. Fleet.

- Summersell, J. (2018). Trans women are real women: A critical realist intersectional response to Pilgrim. Journal of Critical Realism, 17(3), 329–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2018.1493884

- Tan, J. Y., Baig, A. A., & Chin, M. H. (2017). High stakes for the health of sexual and gender minority patients of color. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(12), 1390–1395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4138-3

- Terrell, F., & Terrell, S. (1984). Race of counsellor, client sex, cultural mistrust level, and premature termination from counseling among Black clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31(3), 371–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.31.3.371

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Thurston, M. D., & Allan, S. (2018). Sexuality and sexual experiences during gender transition: A thematic synthesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.008

- Timulak, L. (2007). Identifying core categories of client-identified impact of helpful events in psychotherapy: A qualitative meta-analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 17(3), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300600608116

- Tomson, A. (2018). Gender-Affirming care in the context of medical ethics–gatekeeping v. informed consent. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law, 11(1), 24–28.

- Urry, A. (2012). The struggle towards a femminist practice in family therapy: Premises. In A. C. Miller & R. J. Perelberg (Eds.), Gender and Power in Families, (pp. 104–117). Taylor & Francis Group .

- Vandenbussche, E. (2021). Detransition-related needs and support: Across-sectional online survey. Journal of Homosexuality. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2021.1919479

- Walters, M. (2012). A femminist perspective in family therapy. In A. C. Miller & R. J. Perelberg (Eds.), Gender and Power in Families, (pp. 13–33) Taylor & Francis Group .

- Wampold, B. (2015). How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20238

- Warner, S. (2001). Disrupting identity through visible therapy: A feminist post-structuralist approach to working with women who have experienced child sexual abuse. Feminist Review, 68(1), 115–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/01417780110042437

- Warner, S. (2009). Understanding the effects of child sexual abuse: Feminist revolutions in theory, research and practice. Routledge.

- Westerbotn, M., Blomberg, T., Renström, E., Saffo, N., Schmidt, L., Jansson, B., & Aanesen, A. (2017). Transgender people in Swedish healthcare: The experience of being met with ignorance. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research, 37(4), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057158517695712

- White, B. P., & Fontenont, H. B. (2019). Transgender and non-conforming persons’ mental healthcare experiences: An integrative review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(2), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2019.01.005

- Whitman, C. N., & Han, H. (2017). Clinician competencies: Strengths and limitations for work with transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) clients. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(2), 154–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1249818

- Willig, C. (2013). Introducing qualitative research in psychology (3rd ed.). Open University Press.

- Wren, B. (2019). Ethical issues arising in the provision of medical interventions for gender diverse children and adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 203–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518822694

- Wren, B., Launer, J., Reiss, M., Swanepoel, A., & Music, G. (2019). Can evolutionary thinking shed light on gender diversity? BJPsych Advances, 25(6), 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2019.35