Abstract

Seventy-one percent of US households purchase air care products. Air care products span a diverse range of forms, including scented aerosol sprays, pump sprays, diffusers, gels, candles, and plug-ins. These products are used to eliminate indoor malodors and to provide pleasant scent experiences. The use of air care products can lead to significant benefits as studies have shown that indoor malodor can cause adverse effects, negatively impacting quality of life, hygiene, and the monetary value of homes and cars, while disproportionately affecting lower income populations. Additionally, studies have also shown that scent can have positive benefits related to mood, stress reduction, and memory enhancement among others. Despite the positive benefits associated with air care products, negative consumer perceptions regarding the safety of air care products can be a barrier to their use. During the inaugural Air Care Summit, held on 18 May 2018 in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area, multidisciplinary experts including industry stakeholders, academics, and scientific and medical experts were invited to share and assess the existing data related to air care products, focusing on ingredient and product safety and the benefits of malodor removal and scent. At the Summit’s completion, a panel of independent experts representing the fields of pulmonary medicine, medical and clinical toxicology, pediatric toxicology, basic science toxicology, occupational dermatology and experimental psychology convened to review the data presented, identify potential knowledge gaps, and suggest future research directions to further assess the safety and benefits of air care products.

Introduction (Mary B. Johnson, MS, and Rick Kingston, PharmD)

Air care products span a diverse range of products forms, including aerosol sprays, pump sprays, diffusers, gels, candles and plug-ins. Seventy-one percent of US households purchase air care products; these products are used to remove bad odors as well as to provide an enjoyable scent experience (HHP, Citation2015; Benefit Data, Citation2016). Air care products can be formulated with a variety of odor eliminating technologies (Febreze, Citation2019). These technologies include buffering systems, whereby the pH of odor molecules is altered to a more neutral state, aldehydes, which can react with odor molecules, and encapsulation technologies, whereby odor molecules are contained within macromolecules. Significant research efforts have uncovered the chemical makeup of common malodors and which air care product ingredients can actively treat these malodors ().

Table 1. Malodor classification and mitigating technologies.

The combination of these technologies is meant to combat acute odors and lingering, background odors. The cycle of malodor describes how acute odors can accumulate in homes only to become resuspended in the air. When odor vapor events occur in the home, heat and convection can drive the semi-volatile odor molecules into the air where they are adsorbed onto household surfaces, especially porous surfaces like soft furnishings and dust. The odor molecules can then be slowly released back into the indoor air due to vapor deposition or direct contact.

Consumer perception around air care products can be negative and concerns over product safety can be a significant barrier to consumers using air care products. The main concerns of consumers are for the safety of their families, pets and the environment. These concerns are even more pronounced among millennial consumers (P&G, Citation2015). Manufacturers are proactively responding to these concerns with efforts that include increased transparency regarding product formulations (for example, see SC Johnson, Citation2018; P&G, Citation2017; SC Johnson, Citation2017).

The current negative sentiment around air care products can be attributed to several causes. One such cause for concern involved a report issued by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) in 2007 citing concerns over air care product ingredients (Cohen et al., Citation2007). After publishing this report, the NRDC and the Sierra Club filed a petition with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) requesting that the agencies take action to assess public risks of exposures to air fresheners. Ultimately, both the EPA and CPSC denied the petition, citing a number of factors including the fact that there are very low levels of chemicals cited in the petition as potentially posing a risk from exposure occurring during air care product use (Notice of Receipt, Citation2007; EPA). The EPA further cited poison control incident data involving exposure to air care products and reports of adverse effects. The data revealed that reports of exposure to air care products comprise a very small percentage of calls to poison control centers and the majority (98%) of air care product incidents involve accidental/unintended exposure, not reports of adverse effects when such products are used as intended. Moreover, EPA stated that only 32 (0.23%) of the 14,094 reported air freshener exposures involved an adverse reaction. The EPA concluded, that “Considering the widespread use of air fresheners, the number of reported exposure incidents for air fresheners is relatively small when compared to the reported exposure incidents for other product categories” (Notice of Receipt, Citation2007). These low incident rates are more striking when considering the fact that up to 70% of US households use air care products (Notice of Receipt, Citation2007).

Subsequent to the denial of the petition by EPA and the CPSC, air care companies engaged in a constructive dialog with the NRDC and the Sierra Club finding common ground on a number of key points including a framework for ingredient disclosure and sharing of ingredient data which also led to dismissal of pending litigation between the parties. Air care companies and their national trade association, the Household and Commercial Products Association (HCPA), have continued to work with the NRDC and the Sierra Club to increase transparency and address questions related to ingredient and product safety.

Subsequent review of trends in poison control incident data over the last decade reveals that reports of adverse effects following any type of air care product exposure have also remained low (Gummin et al., Citation2017; Lai et al., Citation2006). Additionally, absolute numbers of reports regarding these types of exposures have remained low over time despite a 10% increase in populations served by poison control centers over the last decade.

Another contributing factor to negative sentiment regarding air care products can be attributed to academic research that has been largely focused on perceived hazards associated with air care product ingredients. Many of these studies, however, involve surveys that target individuals with self-reported asthma or allergies. Questions are then posed that highlight perceived risks of air freshener ingredients while soliciting respondents to indicate if they experience adverse effects when using or are exposed to such products. Unfortunately, these types of studies are not a substitute for clinician assessment of individual patients reporting exposure and adverse effects following air care product exposure or studies that involve research into mechanistic explanations for reported adverse effects. As such, these data may represent an artificially high incidence of adverse events in the populations surveyed and may not necessarily be representative of the experience of the entire population. Despite their limitations, the findings of these studies are often extrapolated to the population as a whole and then covered in media with sensationalist headlines, further adding to consumer skepticism and mistrust of the air care category (Steinemann Citation2017a, Citation2018b).

Lastly, the Internet is a frequent source of misinformation on air care product safety. Typing “benefits of air fresheners” into a search engine prompts a series of articles proclaiming the acute toxicity of air care products. However, these sources are not reliable and it is incumbent upon manufacturers of air care products to share the safety data around their products and ingredients.

It is in this spirit that the inaugural Air Care Summit was convened during the HCPA Mid-Year meeting on 18 May 2018, in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area, where industry scientists as well as outside experts across a variety of fields were invited to discuss the safety data surrounding the category, as well as review the benefits associated with the use of these products. A roundtable panel of independent experts in the fields of pulmonary medicine, medical toxicology, clinical toxicology, pediatric toxicology, basic science toxicology, occupational dermatology, and experimental psychology were invited to provide comments, impressions, and recommendations related to the benefits of air care products, existing safety data, potential data gaps, and suggested future research directions for assessing the safety and science associated with the air care category.

Presentations

Is there a link between asthma and air fresheners? An analysis (Mark J. Utell, MD)

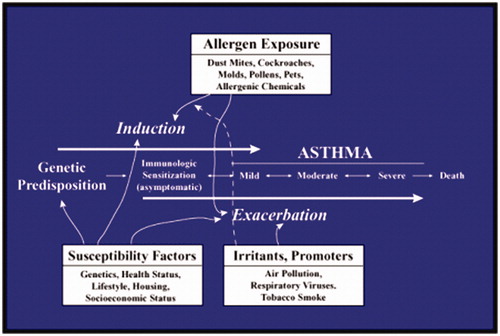

When reviewing adverse health events relating to air fresheners reported in scientific literature, asthma is frequently cited as an outcome. Asthma is a significant disease affecting over 25 million Americans and having a total economic cost of over $80 billion (CDC, Citation2016; Nurmagambetov et al., Citation2018). Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that can cause wheezing, breathlessness, and chest tightness. Asthma entails variable airflow obstruction and increased bronchial hyper-responsiveness that is at least partially reversible (A fresh perspective, Citation2012). The development of new asthma is generally an immune system mediated response to a sensitizer, mitigated by susceptibility factors, allergen exposure and irritants and promoters (EPA, Citation2016a; ).

Figure 1. Factors involved in the induction and exacerbation of asthma. *Reprinted from EPA website.

As an immune-mediated disease, asthma symptoms can be triggered by very low doses of the sensitizer once sensitization has occurred. New asthma that is caused by irritants is often known as Reactive Airways Disease Syndrome (RADS) and is less common than asthma. Irritants can include air pollution, respiratory viruses, chemicals, and tobacco smoke; these can also exacerbate existing asthma.

Recent studies have sought to either directly link or explore the link between asthma and air fresheners. One recent study claimed that 64.3% of asthmatics reported one or more types of adverse health effects from exposure to fragranced products (Steinemann, Citation2018). However, these health effects were self-reported in an online survey and therefore could not be verified or confirmed by medical experts. Additionally, the survey sampling reported that 27% of respondents were asthmatics, compared with the broadly accepted statistic of approximately 10% of the population being asthmatic.

Another study, consisting of 12 non-asthmatics, 12 mild, and eight moderate asthmatics, exposed participants to an aerosolized product with nine fragrances for 15 or 30 min. The results demonstrated no difference in lung function between exposed and control participants and a non-significant trend in airways inflammation in the moderate asthmatics. Moderate asthmatics showed more persistent nasal symptoms (Vethanayagam et al., Citation2013). While this study observes no significant clinical events after exposure, issues with the study design, including small sample size, the unblinded nature and no listed exposure concentration, leave remaining questions. In another study, researchers sought to determine the sensitization potential of common fragrance ingredients. Researchers determined these ingredients did not cause a type-2 immunological response or profile, key hallmarks for sensitization. This suggests that fragrance materials, including those known to cause skin sensitization, do not induce allergic sensitization in the respiratory tract (Basketter & Kimber, Citation2015). However, this study was conducted in a mouse model, and extrapolations to humans can be difficult.

Researchers have also sought to determine any link between air freshener ingredients and RADS. A recent review article has shown that indoor air concentrations of common fragrances occur below their thresholds for sensory irritation in the airways. Temporary higher concentrations of fragrances may occur during cleaning and spray activities, but these concentrations are likely below thresholds for sensory irritation and levels that cause lung function effects. Thus, these fragrances should not be considered to cause sensory irritation (Wolkoff & Nielsen, Citation2017).

Due to the shortcomings of these studies, it is proposed that well designed clinical studies addressing both exposure and symptom end-points are needed to fully elucidate the relationship, if any, between fragrance and asthma. Specific questions to be addressed include (1) is there any evidence that air fresheners or fragrance cause sensitization that leads to asthma and (2) is there any evidence that air fresheners or fragrance exacerbate asthma in mild asthmatics? In summary, a link between the development of asthma and exposure to air fresheners cannot be established based on current studies. Available data simply lack the necessary product specificity to establish causation or an association and bears further investigation.

Evaluating indoor air quality (J. R. Wells, PhD)

Indoor air quality is a significant concern, as gas-phase concentrations of potentially harmful agents can be significantly higher than outdoors. Exposure to these elevated concentrations can pose direct health toxicity concerns. Furthermore, humans, on average, spend 90% of their time indoors, highlighting the significant importance of assessing indoor air quality (Nazaroff & Goldstein, Citation2015).

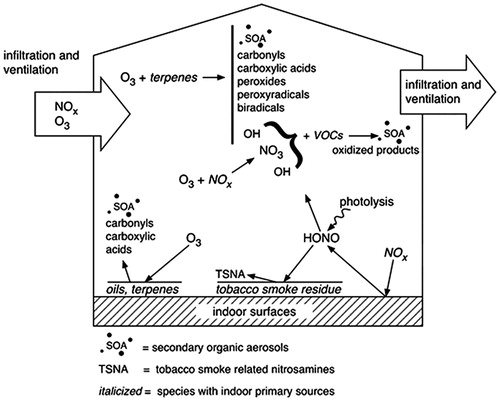

A multitude of gas-phase reactions have been found to occur in indoor environments and the kinetics and transformation mechanisms of these reactions are important for determining exposures and health effects. Ozone, which is present in concentrations of 10 parts per billion (ppb), can exceed 100 ppb in polluted urban areas. Due to its highly reactive nature, ozone will react with unsaturated organic molecules to form a variety of compounds, including formaldehyde as well as short-lived oxidized organic species and highly reactive free radicals. These can include hydroxyl radicals as well as nitrate radicals (Morrison, Citation2015; ).

Figure 2. Major reactants, products and pathways of indoor chemistry. *Reprinted with permission from Morrison (Citation2015).

Terpenes, naturally occurring alkenes, are common ingredients in cleaning agents and air fresheners and are the primary ingredient in many essential oils. Terpenes react readily with ozone and have been shown to form the hydroxyl radical, which can react rapidly with other organics, leading to the formation of other air pollutants with undetermined toxicities and health effects (Nazaroff & Weschler, Citation2004). Studies have demonstrated that terpene reactions with ozone are also capable of producing hydrogen peroxide in small quantities (Fan et al., Citation2005). Significant research efforts have elucidated the mechanisms and rate constants for these reactions (Wells, Citation2005). Surfaces present in households are also able to influence the chemical transformations of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). VOCs can adsorb onto a surface in the indoor environment and are chemically transformed via surface reactions. Recent studies showed that surfaces can enhance reaction rates and lead to different end products than gas-phase reactions (Ham & Raymond Wells, Citation2009).

The health effects of the oxidation products of volatile organic compounds are still being examined. Model studies suggest that the expression of inflammation biomarkers can increase upon exposure to these oxidation by-products (Anderson et al., Citation2010). Future research can hopefully elucidate subsequent health effects of the compounds resulting from reactions with ozone. It is worth noting that ozone is a significant respiratory irritant and there may exist a benefit to the reduction in air concentration of ozone as a result of these chemical reactions. These reaction products also need to be fully considered in terms of their risk, taking into account mitigating factors in building design, including ventilation and surface finishes, among others.

The breadth of this research demonstrates that indoor air chemistry of products such as air fresheners is complex and dynamic. These insights help companies continually update their ingredients during product formulations.

Inhalation safety assessment: process & priorities (Madhuri Singal, PhD, RRT, DABT)

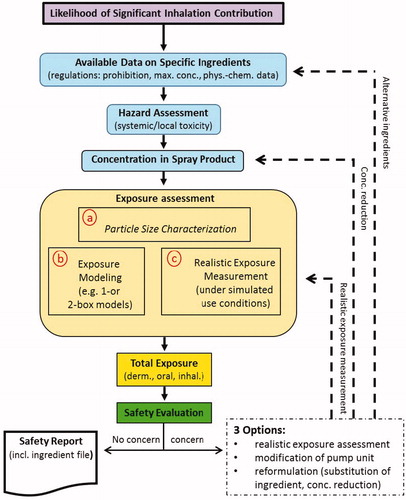

Inhalation exposure and safety assessment models are a core part of the safety assessment of fragrance materials and fragranced products, including a variety of air care products. As an industry, inhalation safety assessment protocols have included a number of assessment tools and methodologies to improve or aid the safety evaluation of air care products and/or fragranced products that are intended to scent the air. These safety paradigms, aligned with the schematic published by the EU Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety, are based on an understanding of both the inherent hazard of the materials in a product formulation as well as the level of exposure to the material based on usage scenarios (Bernauer et al. Citation2012; ).

Figure 3. Basic principles for the safety assessment of inhalable cosmetic products and their ingredients. *Reprinted with permission of SCCS.

A wide range of exposure models are used in the safety risk assessment process. For example, the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM) developed the 2-Box Air Dispersion Model which mimics product usage in consumer representative setting (a room within a larger facility or residence) to calculate peak air concentration from multiple product categories, including air fresheners, candles/incense and plug-in air fresheners/reed diffusers (Research Institute for Fragranced Materials, Citation2019). This model provides a calculated value of potential consumer and/or occupational exposure and may be used in comparison to inhalation Toxicological Threshold of Concern (TTC) should experimental safety data not be available.

Other models that may be employed include the ConsExpo model, IKW, BAMA, BAuA and Multi-Chamber Chemical Exposure Model (BAMA, date unknown; National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Citation2018; EPA, Citation2016b; BAuA, Citation2016; https://www.ikw.org/ikw-english/). These models, including the 2-Box Model, help evaluate all possible exposures under defined conservative use scenarios and assume a homogenous distribution of the emitted concentration over a defined period of time with the potential for 100% inhalation of the airborne concentration.

In reality, the total calculated air concentration represents the worst-case scenario. Another model, the Multiple Path Particle Deposition Model, allows refinement of the exposure assessment by evaluation of regional deposition in the respiratory tract. This model is designed to determine how far, or deep, particulates will travel into the respiratory tract following usage of an air care and/or fragranced product. Therefore, products can be engineered to distribute particle sizes that do not travel deep into the respiratory tract. When materials lack empirical safety data, all of these models can be combined with a toxicological threshold of concern as part of the overall safety risk assessment (Hennes, Citation2012).

Recent publications have sought to definitively link small concentrations of certain volatile organic compounds (VOCs) to respiratory ailments. Limonene, one of the most common fragrance materials, has been shown to react with ozone to form small quantities of formaldehyde. Publications have seized upon this fact to claim that exposure to limonene, and therefore ozone-limonene reaction products that may be formed, from fragranced products could be responsible for negative health effect (Potera, Citation2011). Publications of this variety present anecdotal observations as fact. Survey respondents report self-reported outcomes such as fainting and seizures as a result of exposure (Steinemann, Citation2016).

To help contextualize the exposure to fragranced materials from air care products, one study demonstrated that peeling an orange released approximately 75 times the amount of limonene than spraying a lemon-scented cleaning product (Langer et al., Citation2008). Factors such as airborne concentration, air exchange rate, respiratory rate and tidal volume, duration of exposure, and particle/droplet size can all impact the safety of a sprayed consumer product (Steiling et al., Citation2014).

The air care industry actively follows the SCCS inhalation exposure and safety assessment paradigm, which is globally accepted and approved by regulatory authorities in various countries. Many factors, in addition to those noted above, are considered when evaluating individual ingredients, including biochemical reactivity, chemical structure, solubility, and possible surface charges that may impact the capability for inhalation into the respiratory tract. Understanding the difference between what compounds are in the air versus what compounds are actually inhaled is a critical part of the exposure assessment process and extreme multiple product use scenarios are identified to calculate maximum exposures. Finally, non-animal, high-throughput methods for assessing irritation, inflammation and allergies are actively being developed to enable better definition of the mechanism of action for specific materials (Sayes & Singal, Citation2018).

The age-old debate: natural versus synthetic chemicals (William R. Troy, PhD)

Chemophobia, the irrational fear of chemicals, is on the rise. The beginnings of chemophobia can be traced back to certain chemicals and events in recent history, starting with the use of dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), an insecticide used to combat mosquito-borne illnesses in World War II. DDT saw expanded usage in the 1950s and 1960s, culminating in the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962, where the author called into question the health effects of DDT. These events precipitated the modern environmental movement, with the Environmental Defense Fund being formed in 1967 and the US EPA in 1970. Following public outcry, DDT was banned in 1972.

Further adding to the public’s mistrust of chemicals, a number of related industrial incidents further stoked fears of chemicals, including the Love Canal and Bhopal disasters, whereby toxic chemical exposure resulted in significant injuries and casualties (Brown, Citation1979; Svendsen et al., Citation2012). Further compounding the fear of chemicals, historical examples of cosmetics containing harmful chemicals necessitated the passage of the 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (Eschner, Citation2017).

As labeling of ingredients in household and personal care products became commonplace, consumers became exposed to long and frightening names of the chemicals used in their everyday products. These concerns prompted consumers to seek more natural products, with the belief that these products are inherently safer. However, natural products suffer from several key challenges. The purity of natural products can vary – they are usually multicomponent and can be difficult to characterize and purify. Because of their complexity, the safety profile of natural products can be difficult to determine. Natural products may contain trace materials that can have significant adverse health events.

Synthetic materials, on the other hand, can be extensively purified and characterized to more accurately assess the hazards associated with these materials. Fragrance ingredients are closely scrutinized by the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM), which performs extensive safety and risk assessments for all fragrance materials. These then become part of safety standards set by the International Fragrance Association (IFRA).

In general, consumers lack understanding of the safety assessments that are now part of everyday products. Consumer concerns over synthetic chemicals not only relate to concerns over human and environmental safety and sustainability but are also impacted by their preference for products that offer a more “natural” aroma of feel. Companies and NGOs are quick to capitalize on these fears and consumer preferences with misleading advertising on both flavors and fragrances (Price, Citation2016; Organics, Citation2017). To better educate consumers, it will be necessary for fragrance manufacturers and consumer goods companies to refine their communications to debunk myths that natural materials are always preferable to synthetic materials.

The negative impact of malodor and the benefits of malodor elimination (Steve Horenziak, MSc and Pamela Dalton, PhD, MPH)

People experience a wide variety of malodors in their everyday lives which can have a significant negative impact on their quality of life. Typical malodors that people encounter in the indoor environment come from sources such as pets, cooking, tobacco smoke, and garbage. As population density increases, there has been a proportionate rise in “second-hand smells” in densely populated cities, whereby smells emanating from neighbors’ activities, commercial activities or the outdoor environment can make their way into a person’s indoor environment (Rogers, Citation2006). These malodors can be categorized as an annoyance or as a stressor, or both. Annoyances caused by malodors can be due to the perceived unpleasantness of the odor or simply its intrusion into one’s home. Stress can be caused by malodor particularly when there is concern about the danger associated with exposure to the malodor and when there is a real or perceived lack of control over the source.

The World Health Organization defines health as such: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or affliction” (Card, Citation2017). Given this definition, it is clear that malodors can be an impediment to a healthy life, and the scientific literature has been shown to support the claim that malodors can cause psychological harm, indirect physical harm, cognitive harm, social harm, and economic harms.

One of the most frequently reported harms associated with malodors is psychological harm. Exposure to malodors has a demonstrated effect on mood; some studies have shown a significant increase in feelings of depression, fatigue and confusion when exposed to malodor (Otto et al., Citation1992). Outside of the laboratory setting, the frequent occurrence of malodors has also been shown to elicit psychological harms. Persons living nearby livestock operations that generate community malodor have reported significantly more tension, more depression, more anger, less vigor, and more confusion than unexposed individuals (Schiffman et al., Citation1995). Other studies indicate that these types of malodor may negatively impact activities of daily life (Wing et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, the inability to control malodor can result in feelings of helplessness and not having control of one’s surroundings (Shusterman, Citation1992).

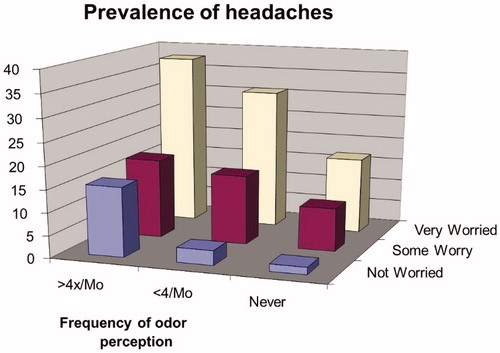

Malodors are responsible for perceived or indirect physical harm. People who live with frequent exposure to malodors often experience “odor worry”, a phenomenon whereby concern about the nature of a malodor source can lead to increased reporting of stress-induced symptoms such as headache (Shusterman et al., Citation1991; ).

Figure 4. Prevalence of headache and malodor exposure (adapted from Shusterman, Citation1991).

Odor perception has been shown to impact physical responses to odors, including but not limited to reporting of increased irritation and exacerbation of asthmatic symptoms (Cornell Karnekull et al., Citation2011; Dalton, Citation1996; Jaén & Dalton, Citation2014). Globally, air pollution and malodors are present disproportionately in less economically developed regions, impacting both indoor and outdoor air (PHE, WHO, Citation2018; WHO, Citation2018). In India, malodors can be related to significant health-related harms. Latrine malodors reduce the incidence of use of indoor latrines, resulting in poor sanitation and hygiene, leading to adverse health effects (Gates, Citation2016).

In addition to psychological and physical harms, malodors may also be a source of cognitive harm. Malodor has been shown to impair performance on complex tasks such as proofreading documents (Rotton, Citation1983). Interestingly, people exposed to malodors reported that the presence of a malodor can be responsible for decreased testing performance (Knasko, Citation1992). Conversely, removal of malodor has been shown to increase performance and subjective responses in workers, highlighting the role that malodors can play in reduced workplace productivity (Fisk et al. Citation2011; Wargocki et al., Citation2004).

Malodors can also influence behavior, which can lead to social harm. Malodors have been shown to impact interpersonal relationships, with researchers demonstrating that malodor can reduce interpersonal attraction (Rotton et al., Citation1978). Body odors have been shown to negatively influence personality assessments, highlighting the role of olfactory cues during social interactions (Sorokowska Citation2013; Sorokowska et al., Citation2012). Body odors have also been shown to evoke feelings of pitifulness in others (Camps et al., Citation2014). Body odor also plays a significant role in self-confidence (Craig Roberts et al., Citation2009). People experiencing malodors in their households also experience a variety of social harms. When malodor is experienced as an annoyance, people are known to demonstrate a variety of coping mechanisms (Cavalini et al., Citation1991). Behavioral modifications can be incredibly diverse but are known to impact several social situations. People living in close proximity to industrial malodor sources can experience a variety of social effects, including not letting children play outdoors, not having neighborhood social events and an overall reduced social interaction (Hayes et al., Citation2017).

Lastly, malodors are known to cause significant economic harm. Property values can be noticeably affected by proximity to commercial activities that produce frequent malodors (Anstine, Citation2003; Bazen & Fleming, Citation2004). Economic models have been built to quantify this economic impact (Cameron, Citation2006). In addition to affecting housing, used car prices have been shown to be affected by the presence of malodors as well (Matt et al., Citation2008). Malodors can also influence consumer satisfaction in the hospitality industry, particularly as it pertains to hotels and lodging (Lockyer, Citation2003; Ren et al., Citation2015). As well, the perceived quality of both nursing homes and hospital facilities are increased when malodors are controlled (Rantz et al., Citation1998).

Air care technologies, with their ability to remove malodors, have significant potential to address the numerous harms that can occur as a result of exposure to malodor. In the global sense, air care products may also have the ability to address public health needs. Researchers have investigated the ability of air care technologies to reduce malodors in community and public toilets in India, which are a reported impediment to usage (PHE, WHO, Citation2018). Public health risks can be mitigated when people reduce the practice of open defecation, pointing to the role air care can play in improving sanitation and hygiene in developing regions. Finally, there can be a disproportionate impact of malodors on individuals in lower socio-economic groups, as they may be less able to modify their indoor environment or to move from the source of malodors. Air care products can introduce a measure of control over malodors in these situations and can help improve quality of life.

Regulatory environment of fragrances (Farah K. Ahmed)

As we consider the benefits of fragrance, it is important to note that consumers should have confidence in their safety. Fragrances are among the most highly tested ingredients in the consumer product marketplace.

Fragrances are subject to multiple levels of regulations and governmental oversight. In the United States, the fragrance industry is regulated by many government agencies including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the EPA, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the Department of Transportation (DOT)

Fragrances are subject to over a dozen Federal laws, including the Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act (FDCA), the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), the Clean Water Act (CWA), and the Consumer Product Safety Act (CPSA). In addition, fragrances are subject to multiple state and local laws and regulations.

To better understand the breadth of fragrance regulation, including nongovernmental regulation, the fragrance supply chain should be considered. Raw material suppliers sell fragrance ingredients to fragrance companies. These fragrance companies sell to consumer product companies who distribute their products through retailers. Consumers purchase consumer products at the retail level.

Each step in this supply chain is heavily regulated. Fragrance ingredients require chemical registration with EPA. The fragrance industry voluntarily self-regulates through the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM)’s safety program, whose safety assessments are reviewed by an independent expert panel, and the International Fragrance Association (IFRA)’s Code of Practice. Fragrances are also restricted by the demands made by certain customers, brands, products, retailers, and consumers. The fragrance industry actively works to build confidence in its products and works collaboratively as an industry, with regulators, and with the supply chain to substantiate that products are safe for their intended uses.

The benefits of fragrance (Rachel S. Herz, PhD)

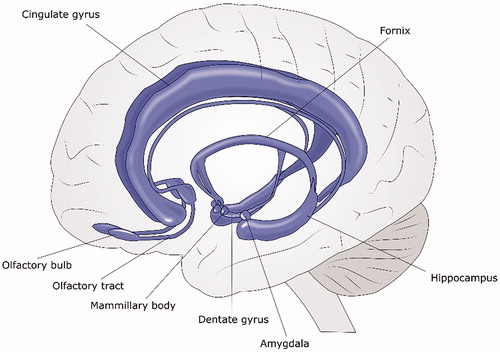

Fragrance, be it synthetic or natural, plays a critical role in people’s daily lives. The psychology of scent is a robust field of research, especially with regard to the role that scent plays in memory. Unlike other senses, the sense of smell uniquely links to memories via the unique anatomical access of the olfactory pathway of the memory and emotion centers in the brain, the amygdala and the hippocampus (). This is known as the Proustian memory effect, whereby fragrances elicit more emotional and evocative memories than other memory cues (Herz, Citation1998).

Researchers have determined that odors are able to evoke positive autobiographical memories, a recollection of a meaningful past personal experience (Chu, Citation2000). Pleasant autobiographical memories have been demonstrated to induce positive mood; invoking these memories has previously been used as a therapeutic technique to treat emotional distress in various clinical conditions (Panagioti et al., Citation2012). Scent has been demonstrated to increase positive emotions, decrease negative mood states and disrupt cravings (Herz, Citation2016). Additionally, scent has been shown to reduce indices of stress, including a decrease in systemic markers of inflammation such as peripheral proinflammatory cytokines (Matsunaga et al., Citation2013).

Odor-evoked memories can also influence product perception. In one study, participants were instructed to use a variety of scented lotions over a one week time period, with fragrance being the only variable aspect of product formulation. Participants who rated a given fragrance as very pleasant and who experienced a potent Proustian memory, perceived the lotion as more positive on a wide range of functional performance and emotional attributes. Participants who experienced a weak Proustian memory reported lower functional and emotional performance of the lotion, regardless of how much they liked the fragrance (Sugiyama et al., Citation2015).

Odor can also play a significant role in managing food cravings by augmenting taste sensations. For example, one study found that vanilla aroma made milk taste sweeter, while another demonstrated that odors can impact food selection (Gaillet-Torrent et al., Citation2014; Lavin & Lawless, Citation1998).

Significant research efforts have sought to elucidate the exact mechanism by which scents and fragrances can impact emotional and physical health effects. There are two hypotheses for the mechanism of action of olfactory effects in humans (Herz, Citation2009). The pharmacological hypothesis postulates that odors have a direct and intrinsic ability to interact with and affect the autonomic nervous system/central nervous system and/or endocrine system. The psychological hypothesis postulates that odors exert their effects through emotional learning, conscious perception, and belief/expectation. The central claim of the psychological hypothesis is that responses to odors are learned through association with emotional experiences and that odors consequently take on the properties of the associated emotions and exert the concordant emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and physiological effects themselves. Evidence points toward the psychological hypothesis, as the chemical nature of the odorant itself plays a secondary role in the emotional and subjective changes that occur in the presence of an odor, and that it is the personal meaning of the scent that induces the consequent psychological and/or physiological responses.

Further highlighting the positive role scent plays in daily life, there have been numerous studies linking negative outcomes with anosmia, an impairment of loss of the sense of smell. Anosmia can impact the enjoyment of food, home safety issues, personal life, and hygiene (Toller, Citation1999). Anosmia causes profound psychosocial effects, resulting in feelings of physical and social vulnerability and isolation (Tennen et al., Citation1991). Ultimately, these impacts can lead to a loss of sense of self, highlighting the critical role that scents play in quality of life.

Discussion (Pamela Dalton, PhD, MPH, Rick Kingston, PharmD, Tom Osimitz, PhD, Steven Prawer, MD, Mark J. Utell, MD, Shan Yin, MD, MPH)

At the inaugural Household & Commercial Products Association (HCPA) Air Care Summit, held on 18 May 2018 in Washington, DC, multidisciplinary experts including industry stakeholders, academics, and scientific and medical experts came together to share and assess the science behind air care products with the goal of examining the multiple facets of product benefit, safety, and opportunities for further research. As part of the Summit, a roundtable panel of experts representing the fields of pulmonary medicine, medical and clinical toxicology, pediatric toxicology, basic science toxicology, occupational dermatology, and experimental psychology were asked to evaluate the presented data and provide comments, impressions, and recommendations related to the benefits of air care products, existing safety data, potential data gaps, and suggested future research directions for ongoing assessment of the safety and science associated with the air care category.

The expert panel elected to comment on a number of key findings from the presented data including the benefits of fragrance and odor elimination, the safety of air care products including effects on those with allergy and asthma, the presence of various ingredients of concern, industry efforts to increase transparency, and the opportunities for future research in the area.

Regarding the benefit of fragrance, the panel found the science to include compelling and positive data regarding the role that fragrances can play in the everyday lives of people. Fragrance is positively associated with emotional benefits such as nostalgia, memory and self-image. Unlike any other sense, the sense of smell uniquely links to memories via the connections between the olfactory pathway with the memory and emotion centers in the brain (the amygdala and hippocampus). Because of this, odors can evoke more pleasant autobiographical memories, feelings of nostalgia, and, therefore, improvements in psychological health.

A large body of research demonstrates that the presence of malodor in indoor areas including bathrooms and other areas known to harbor and/or promote the generation of offensive odors has tangible adverse effects on residents. Exposure to malodor can result in emotional, cognitive, social, and economic harm. Furthermore, the effects of living with malodor fall disproportionately on those with fewer resources and who have less ability to have control over their living situations. People use air care products and other malodor eliminating technologies to improve their standard of living and maintain a better quality of life.

Two specific chemicals identified as posing potential risks to health have been associated with air fresheners either as contaminants or intentionally added ingredients include phthalates and formaldehyde. It bears mentioning both compounds in the context of product safety and disclosure transparency.

Regarding phthalates: some phthalate compounds have been shown to be carcinogenic to laboratory rodents and these findings have cast a shadow of concern over the entire class of phthalate compounds. One phthalate in current use by some companies within the fragrance industry is diethyl phthalate (DEP) which has not been found to be carcinogenic (Carlson & Patton, Citation2010). DEP has been assessed by authoritative bodies as having a positive safety profile and has been determined to be safe for use in cosmetics and personal care products at currently used levels (European Commission, Citation2002; Chambers et al. Citation2007; Brandt, Citation2012). Although many air care companies have eliminated or are moving away from any phthalate use in their manufacturing processes, some phthalates continue to be found in air care products as low-level contaminants. A risk assessment regarding the presence of phthalate contaminants found in air care products performed by EPA and CPSC concluded that the presence of phthalates at contaminant levels does not pose a risk to consumer safety. Efforts by industry to eliminate the presence of phthalates in air care products, even at contaminant levels are encouraged.

Formaldehyde is another chemical with a hazard profile that has raised concerns over its presence in air care products. Concern over the presence of formaldehyde stems, in part, from the belief that the substance is an allergen and sensitizer, a finding reported in the EPA’s 2010 assessment of formaldehyde. Yet, when the EPA’s findings regarding formaldehyde were further scrutinized by the National Academy of Science (NAS), the NAS concluded that EPA’s findings were not well supported by the science (National Research Council, Citation2011).

As for the presence of formaldehyde in some Air Care products, Air Care product manufacturers do not formulate with formaldehyde but some air care product preservative systems are designed to generate low levels of formaldehyde for preservative effect or, formaldehyde may be produced when ingredients in an air care product come in contact with treated surfaces. Of note, large manufacturers have moved away from formaldehyde-producing preservative systems. Continued study into the potential health consequences associated with low level formaldehyde exposure associated with some air care products warrants further research. Industry is encouraged to collaborate with entities such as the National Institutes for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) which is currently studying the impacts of formaldehyde and other VOCs on indoor air quality.

Adverse health effects including respiratory complaints and exacerbation of asthma by some individuals when exposed to air care products has been reported along with less serious respiratory irritation. The development of new asthma is generally an immune system mediated response to a sensitizer, mitigated by susceptibility factors, allergen exposure, and irritants and promoters. Evidence of an immunological response to fragrance is weak. Although there are poorly controlled surveys claiming links between fragrances and asthma symptoms, there have not been rigorously performed studies examining the relationship between fragrance exposure with either exacerbations or new onset asthma. The panel recommends exploring investigative approaches to examine whether a relationship exists between fragrance or finished air care product exposure and respiratory symptoms and/or lung function changes. If the findings support the potential for a relationship, then it would be necessary to examine possible mechanisms.

The available safety data regarding air care products provides encouraging evidence that despite their widespread use and concern over potential adverse health effects, reports of injury subsequent to product exposure made to entities such as poison control centers are very low. These findings are supported by previous analysis of poison center incident data conducted by the EPA and CPSC (EPA, Citation2007). These Agencies noted that the low incidence of reported exposures with adverse effects were more striking when considering the fact that up to 70% of US households use air care products and over 647 million containers of propellant versions of air care products were sold in 2017 (Household and Commercial Products Association, Citation2017). Poison center incident data provides a good model to study the acute respiratory effects of airborne products as consumers routinely call poison centers for assistance when such effects are experienced and suspected to be caused by a specific product.

The expert panel concluded that industry is taking major steps to further identify and address areas of public concern. As an example, most major air care product manufacturers have voluntarily posted a list of ingredients on their websites and the entire industry is moving towards disclosure of product ingredients so that consumers and health-care professionals can make informed decisions about the use and recommendation of concerning individual products. The air care industry has worked with regulators and other interested stakeholders in the development of consistent, science-based requirements for proposed mandatory disclosure of product ingredients.

In summary, the Panel recognized the benefits associated with air care products and the removal of malodor. Furthermore, the Panel urged the air care industry to continue to address, with rigorous evidence-based approaches to the areas of public concern, including ingredient and inhalation safety.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disclosure statement

Mary B. Johnson is an employee of The Procter & Gamble Company. Dr Kingston is a product safety consultant to industry, NGOs and governmental entities and has provided safety consultation to companies in the air care industry including the Procter & Gamble company. He is also a Partner at SafetyCall International, a healthcare firm that provides safety consultation including post market safety surveillance and adverse event reporting support for companies that manufacture air care and other consumer products. Dr Utell has served as a member of the respiratory advisory board to the Research Institute of Fragrance Materials (RIFM), as a consultant to Firmenich, and as a consultant to SC Johnson. He has been the recipient of a research grant from RIFM. He received an honorarium from the HCPA to attend the Air Care Summit as a speaker and expert panel member. J. R. Wells’ travel expenses were partially sponsored by HCPA for the Air Care Summit. Madhuri Singal was an employee of Reckitt Benckiser Group while participating in the Air Care Summit. Dr Troy is currently working as a consultant for the International Federation of Essential Oils and Aroma Trades on the subject of Natural Complex Substances. He was employed for 25 years in the cosmetics industry (Revlon and Avon Products) and 17 years in the fragrance manufacturing industry (Firmenich Inc.). Dr Troy received an honorarium from HCPA for his participation in the Air Care Summit. Steve Horenziak is an employee of The Procter & Gamble Company. Pamela Dalton is a consultant/grantee or speaker for the following companies: American Chemistry Council, Ajinomoto Co., Inc., Altria Group, Campbell Soup Company, Church & Dwight, The Coca-Cola Company, Diageo, plc, Diana Ingredients, Estée Lauder Inc., Firmenich Incorporated, Fragrance Creators Association, Givaudan SA, GlaxoSmithKline, Intelligent Sensor Technology, Inc., Japan Tobacco Inc., Johnson & Johnson Consumer Products, Kao Corporation, Kellogg, Kerry, Mars, McCormick & Company, Inc., Mead Johnson Nutritionals, Mondelēz International, PepsiCo, Inc., Pfizer, Inc., Procter & Gamble, Reckitt Benckiser Group, Roquette, Royal DSM, Sensonics International, Suntory Holdings Ltd., Symrise, Takasago International Corporation, Tate & Lyle, Unilever Research & Development, Wm. Wrigley Jr Company, Young Living Essential Oils and Zensho Holdings Co. Ltd. Dr. Dalton received an honorarium from HCPA for her participation in the Air Care Summit. Farah K. Ahmed is President & CEO of the Fragrance Creators Association (FCA), a non-profit organization whose members may be indirectly affected by the information reported in the enclosed paper. Dr Herz has worked as an expert witness involving ambient product odor for the following companies: Grain Processing Corporation, Cedar Grove Composting and Mars Foods. She has received a grant from The Fragrance Foundation. She also has acted as a consultant and speaker for the following fragrance/flavor companies: Givaudan, Unilever, International Flavors & Fragrances, Proctor & Gamble, SC Johnson, KAO Corporation, Firmenich, Haarman & Reimer, McCormick, Southern Wine & Spirits, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Coty, Inc., Dial/Henkel, Elizabeth Arden, AromaSys, Advent, HPCA, World Candle Congress and Droga5. Dr Herz received an honorarium from HCPA for his participation in the Air Care Summit. Dr Osimitz primarily consults with companies and organizations in the chemical and pesticide area. He also works as a consultant for Takasago (a fragrance supplier). Dr Osimitz received an honorarium from the HCPA to participate in the Air Care Summit. Dr Prawer received an honorarium from HCPA to attend May 2018 Air Care Summit. Dr Yin consults for Procter & Gamble and McNeil. He has also received an honorarium from HCPA to attend May 2018 Air Care Summit.

References

- A Fresh Perspective. (2012). A fresh perspective on asthma. Nature Medicine, 18, 631.

- Anderson SE, Jackson LG, Franko J, Wells JR. (2010). Evaluation of dicarbonyls generated in a simulated indoor air environment using an in vitro exposure system. Toxicol Sci. 115:453–61.

- Anstine J. (2003). Property values in a low populated area when dual noxious facilities are present. Growth Change 34:345–58.

- Aussant EJ, Bassereau MB, Fraser SB, Warr FJ, inventors; Takasago International Corp, assignee. (2006 Aug 4). Use of fragrance compositions for the prevention of the development of indole base malodours from fecal and urine based soils. United States patent application 20080032912.

- BAMA. (date unknown). BAMA indoor air model. British Aerosol Manufacturers Association. https://www.bama.co.uk/product.php?product_id=12.

- Basketter D, Kimber I. (2015). Fragrance sensitisers: is inhalation an allergy risk? Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 73:897–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.09.031

- BAuA. (2016). SprayExpo: modelling exposure during spray applications. Federal Institute for Occupational safety and Health. https://www.baua.de/EN/Topics/Work-design/Hazardous-substances/Assessment-unit-biocides/Sprayexpo.html.

- Bazen EF, Fleming RA. (2004). An economic evaluation of livestock odor regulation distances. J Environ Qual 33:1997. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2004.1997

- Behan JM, Goodall JA, Perring KD, et al., inventors; Quest International BV, assignee. (1993 Nov 30). Anti-smoke perfumes and compositions. United States Patent US 5,676,163.

- Benefit Data. (2016). Benefit Data: Survey (IPSOS) Data from April 2016. Asked among those who have used and air freshener in past 6 months.

- Betz A, Boden R, Colt K, et al., inventors; International Flavors and Fragrances Inc, assignee. (2003 Nov 13). Synergistically-effective composition of zinc ricinoleate and one or more substituted monocyclic organic compounds and use thereof for preventing and/or suppressing malodors. United States patent application 20050106192.

- Brandt K. (2012). Phthalates. CIR Expert Panel Meeting, December 10–11, 2012. https://www.cir-safety.org/sites/default/files/phth_online.pdf

- Brown MH. (1979 Dec). Love Canal and the Poisoning of America. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1979/12/love-canal-and-the-poisoning-of-america/376297/

- Cameron TA. (2006). Directional heterogeneity in distance profiles in hedonic property value models. J Environ Econ Manag 51:26–45.

- Camps J, Stouten J, Tuteleers C, van Son K. (2014). Smells like cooperation? Unpleasant body odor and people’s perceptions and helping behaviors: smells like cooperation? J Appl Soc Psychol 44:87–93.

- Cappel JP, Geis PA, McCarty ML, et al., inventors; Procter and Gamble Co, assignee. (1994 Aug 12). Fabric treating composition containing beta-cyclodextrin and essentially free of perfume. United States patent US 5,534,165.

- Card AJ. (2017). Moving beyond the WHO Definition of Health: a new perspective for an aging world and the emerging era of value-based care: redefining health. World Med Health Policy 9:127–37.

- Carlson KR, Patton LE. (2010). Toxicity Review of Diethyl phthalate (DEP). United States Consumer Product Safety Commission. https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/ToxicityReviewOfDEP.pdf

- Cavalini PM, Koeter-Kemmerling LG, Pulles MPJ. (1991). Coping with odour annoyance and odour concentrations: three field studies. J Environ Psychol 11:123–42.

- CDC. (2016). National current asthma prevalence. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm.

- Chu S. (2000). Odour-evoked autobiographical memories: psychological investigations of Proustian phenomena. Chem Senses 25:111–6.

- Chung AH, Cobb DS, Reece S, et al., inventors. (1997 Jun 9). Uncomplexed cyclodextrin compositions for odor control. United States patent US 5,942,217.

- Cohen A, Janssen S, Solomon G. (2007 18 Sep). Clearing the air: hidden hazards of air fresheners. National Resources Defense Council. Citizen petition to EPA and CPSC regarding air fresheners. https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/airfresheners.pdf

- Cornell Karnekull S, Jonsson FU, Larsson M, Olofsson JK. (2011). Affected by smells? Environmental chemical responsivity predicts odor perception. Chem Senses 36:641–8.

- Craig Roberts S, Little AC, Lyndon A, et al. (2009). Manipulation of body odour alters men’s self-confidence and judgements of their visual attractiveness by women. Int J Cosmet Sci 31:47–54.

- Dalton P. (1996). Odor perception and beliefs about risk. Chem Senses 21:447–58.

- Department of Public Health, Environmental and Social Determinants of Health (PHE), WHO. (2018). Ambient air pollution – a major threat to health and climate. Geneva: PHE, WHO. http://www.who.int/airpollution/ambient/en/.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2007a). Air fresheners. TSCA Section 21 Petition. US Federal Register.

- EPA. (2007). Air Fresheners; TSCA Section 21 Petition; Notice. See Federal Register 72: 72886–96 and CPSC. Letter from Lowell F. Martin, Acting General Counsel, Office of the General Counsel, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, to Mr. Ed Hopkins, Director, Environmental Quality Program, Sierra Club; Ms. Rebecca Morley, National Center for Health Housing; Mr. Robert Zdenek, Alliance for Healthy Homes, and Mae C. Wu, Natural Resources Defense Council (2007 Nov 23).

- EPA. (2016a). Health effects of ozone in patients with asthma and other chronic respiratory disease. https://www.epa.gov/ozone-pollution-and-your-patients-health/health-effects-ozone-patients-asthma-and-other-chronic.

- EPA. (2016b). Multi-Chamber Concentration and Exposure Model (MCCEM) version 1.2. https://www.epa.gov/tsca-screening-tools/multi-chamber-concentration-and-exposure-model-mccem-version-12.

- Eschner K. (2017 June). Three Horrifying Pre-FDA Cosmetics. The Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/three-horrifying-pre-fda-cosmetics-180963775/

- European Commission. (2002). Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Cosmetic Products and Non-Food Products Intended for Consumers Concerning Deithyl Phthalate. Adopted by the SCCNFP during the 20th Plenary meeting of 4 June 2002. https://ec.europa.eu/health/archive/ph_risk/committees/sccp/documents/out246_en.pdf

- Chambers C, Degen G, Jazwiec-Kanyion B, et al. (2007). Opinion on Phthalates in Cosmetic Products. Adopted by the SCCP during the 11th plenary meeting of 21 March 2007.

- Bernauer U, Bodin L, Chaudhry Q et al. (2012). The SCCS Notes of Guidance for the Testing of Cosmetic Ingredients and Their Safety Evaluation, 8th revision; adopted at the SCCS 17th plenary meeting of 11 December 2012.

- Fan Z, Weschler CJ, Han IK, Zhang JJ. (2005). Co-formation of hydroperoxides and ultra-fine particles during the reactions of ozone with a complex VOC mixture under simulated indoor conditions. Atmos Environ 39:5171–82.

- Febreze. (2019). How & why Febreze cleans away the stink – a deep dive into OdorClear technology. https://www.febreze.com/en-us/learn/how-febreze-works.

- Fisk WJ, Black D, Brunner G. (2011). Benefits and costs of improved IEQ in U.S. Offices. Indoor Air 21:357–67.

- Gaillet-Torrent M, Sulmont-Rossé C, Issanchou S, et al. (2014). Impact of a non-attentively perceived odour on subsequent food choices. Appetite 76:17–22.

- Gates B. (2016 Nov 16). “A perfume that smells like poop?”. https://www.gatesnotes.com/Development/Smells-of-Success.

- Gautschi M, Flachsmann F, McGee T, Sgaramella RP, inventors; Givaudan SA, assignee. (2007 Sep 7). Dimethylcyclohexyl derivatives as malodor neutralizers. United States patent application 20100209378.

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. (2017). 2016 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 34th annual report. Clin Toxicol 55:1072–254.

- Ham JE, Raymond Wells J. (2009). Surface chemistry of dihydromyrcenol (2,6-dimethyl-7-octen-2-ol) with ozone on silanized glass, glass, and vinyl flooring tiles. Atmos Environ 43:4023–32.

- Hayes JE, Stevenson RJ, Stuetz RM. (2017). Survey of the effect of odour impact on communities. J Environ Manag 204:349–54.

- Hennes EC. (2012). An overview of values for the threshold of toxicological concern. Toxicol Lett 211:296–303.

- Herz R. (2016). The role of odor-evoked memory in psychological and physiological health. Brain Sci 6:22.

- Herz RS. (1998). Are odors the best cues to memory? A cross-modal comparison of associative memory stimuli. Ann N Y Acad Sci 855:670–4.

- Herz RS. (2009). Aromatherapy facts and fictions: a scientific analysis of olfactory effects on mood, physiology and behavior. Int J Neurosci 119:263–90.

- HHP. (2015). HHP. Source: US Nielsen % Household Penetration 30 Nov 2014–28 Nov 2015.

- Household and Commercial Products Association. (2017). Aerosol pressurized products survey. https://member.thehcpa.org/products/product/Aerosol-Pressurized-Products-Survey

- Jackson JR, Liu Z, Malanyaon MVN, et al., inventors; Procter and Gamble Co, assignee. (2009 Dec 17). Malodor control composition having a mixture of volatile aldehydes and methods thereof. United States patent application 20110150814.

- Jaén C, Dalton P. (2014). Asthma and odors: the role of risk perception in asthma exacerbation. J Psychosom Res 77:302–8.

- Joulain D, Maire F, Racine P, inventors; Robertet P, Cie SA, assignee. (1986 May 29). Agent neutralizing bad smells from excretions and excrements of animals. United States patent US 4,840,792.

- Joulain D, Racine P, inventors; Robertet P, Cie SA, assignee. (1989 May 29). Deodorant compositions containing at least two aldehydes and the deodorant products containing them. United States patent US 5,795,566.

- Knasko SC. (1992). Ambient odors effect on creativity, mood, and perceived health. Chem Senses 17:27–35.

- Lai MW, Klein-Schwartz W, Rodgers GC, et al. (2006). 2005 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' national poisoning and exposure database. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 44:803–932.

- Langer S, Moldanová J, Arrhenius K, et al. (2008). Ultrafine particles produced by ozone/limonene reactions in indoor air under low/closed ventilation conditions. Atmos Environ 42:4149–59.

- Lavin JG, Lawless HT. (1998). Effects of color and odor on judgments of sweetness among children and adults. Food Qual Prefer 9:283–9.

- Levorse AT, Monteleone MG, Tabert MH, inventors; International Flavors and Fragrances Inc, assignee. (2011 Dec 12). Novel malodor counteractant. United States patent application 20130149269

- Lockyer T. (2003). Hotel cleanliness—how do guests view it? Let us get specific. A New Zealand study. Int J Hosp Manag 22:297–305.

- Manderfield CE, Nguyen PN, Tasz MK, inventors; S C Johnson and Son Inc, assignee. (2005 Dec 20). Odor elimination composition for use on soft surfaces. United States patent application 20120027713.

- Matsunaga M, Bai Y, Yamakawa K, et al. (2013). Brain–immune interaction accompanying odor-evoked autobiographic memory. PLoS One 8:e72523.

- Matt GE, Romero R, Ma DS, et al. (2008). Tobacco use and asking prices of used cars: prevalence, costs, and new opportunities for changing smoking behavior. Tob Induc Dis 4:2.

- Morrison G. (2015). Recent advances in indoor chemistry. Curr Sust/Renew Energ Rep 2:33–40.

- National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. (2018). ConsExpo. https://www.rivm.nl/en/Topics/C/ConsExpo.

- National Research Council. (2011). Review of the environmental protection agency's draft IRIS assessment of formaldehyde. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Nazaroff WW, Goldstein AH. (2015). Indoor chemistry: research opportunities and challenges. Indoor Air 25:357–61.

- Nazaroff WW, Weschler CJ. (2004). Cleaning products and air fresheners: exposure to primary and secondary air pollutants. Atmos Environ 38:2841–65.

- Nguyen PN, Bhaveshkumar S, inventors; S C Johnson and Son Inc, assignee. (2010 June 18). Aerosol odor eliminating compositions containing alkylene glycol(s). United States patent application 20130001260.

- Notice of Receipt. (2007). Notice of Receipt of TSCA Section 21 Petition. Federal Register 72: 60016–18. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2007-12-21/pdf/07-6176.pdf

- Nurmagambetov T, Kuwahara R, Garbe P. (2018). The economic burden of asthma in the United States, 2008–2013. Ann Am Thorac Soc 15:348–56.

- Organics. (2017). Natural vs artificial flavors. https://www.organics.org/natural-vs-artificial-flavors/.

- Otto DA, Hudnell HK, House DE, et al. (1992). Exposure of humans to a volatile organic mixture. I. Behavioral assessment. Arch Environ Health: Int J 47:23–30.

- P&G. (2015). P&G data on file. An internet survey of 42 people in the US conducted in 2015, segmented by age.

- P&G. (2017). P&G expands transparency commitment to include fragrance ingredients across product portfolio. http://news.pg.com/press-release/pg-corporate-announcements/pg-expands-transparency-commitment-include-fragrance-ingred.

- Panagioti M, Gooding PA, Tarrier N. (2012). An empirical investigation of the effectiveness of the broad-minded affective coping procedure (BMAC) to boost mood among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Behav Res Ther 50:589–95.

- Potera C. (2011). Indoor air quality. Scented products emit a bouquet of VOCs. Environ Health Perspect 119:A16.

- Price A. (2016). Dangers of synthetic scents include cancer, asthma, kidney damage and more. https://draxe.com/dangers-synthetic-scents/.

- Rantz MJ, Mehr DR, Popejoy L, et al. (1998). Nursing home care quality: a multidimensional theoretical model (interdisciplinary performance improvement). J Nurs Care Qual 12:30–46.

- Ren L, Zhang HQ, Ye BH. (2015). Understanding customer satisfaction with budget hotels through online comments: evidence from home inns in China. J Qual Assurance Hosp Tourism 16:45–62.

- Research Institute for Fragranced Materials. (2019). Assessment tools. Research Institute for Fragranced Materials. http://www.rifm.org/rifm-science-assessment-tools.php.

- Rogers TK. (2006 Aug 6). What’s That Smell? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/06/realestate/06cov.html

- Rotton J. (1983). Affective and cognitive consequences of malodorous pollution. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 4:171–91.

- Rotton J, Barry T, Frey J, Soler E. (1978). Air pollution and interpersonal attraction. J Appl Soc Psychol 8:57–71.

- Sayes CM, Singal M. (2018). Optimizing a test bed system to assess human respiratory safety after exposure to chemical and particle aerosolization. Appl In Vitro Toxicol 4(2).

- SC Johnson. (2017). SC Johnson welcomes P&G, Unilever, RB to fragrance transparency movement. http://www.scjohnson.com/en/press-room/press-releases/08-30-2017/SC-Johnson-Welcomes-PG-Unilever-RB-to-Fragrance-Transparency-Movement.aspx.

- SC Johnson. (2018). Expanded Fragrance Disclosure. http://www.scjohnson.com/en/products/monty/fragrancedisclosure.aspx.

- Schiffman SS, Sattely Miller EA, Suggs MS, Graham BG. (1995). The effect of environmental odors emanating from commercial swine operations on the mood of nearby residents. Brain Res Bull 37:369–75.

- Shusterman D. (1992). Critical review: the health significance of environmental odor pollution. Arch Environ Health 47:76–87.

- Shusterman D, Lipscomb J, Neutra R, Satin K. (1991). Symptom prevalence and odor-worry interaction near hazardous waste sites. Environ Health Perspect 94:25.

- Sorokowska A. (2013). Seeing or smelling? Assessing personality on the basis of different stimuli. Pers Individ Differ 55:175–9.

- Sorokowska A, Sorokowski P, Szmajke A. (2012). Does personality smell? Accuracy of personality assessments based on body odour: does personality smell? Eur J Pers 26:496–503.

- Steiling W, Bascompta M, Carthew P, et al. (2014). Principle considerations for the risk assessment of sprayed consumer products. Toxicol Lett 227:41–9.

- Steinemann A. (2016). Fragranced consumer products: exposures and effects from emissions. Air Qual Atmos Health 9:861–6.

- Steinemann A. (2017). Ten questions concerning air fresheners and indoor built environments. Build Environ 111:279–84.

- Steinemann A. (2018). Fragranced consumer products: effects on asthmatics. Air Qual Atmos Health 11:3–9.

- Sugiyama H, Oshida A, Thueneman P, et al. (2015). Proustian products are preferred: the relationship between odor-evoked memory and product evaluation. Chemosens Percept 8:1–10.

- Svendsen ER, Runkle JR, Dhara VR, et al. (2012). Epidemiologic methods lessons learned from environmental public health disasters: Chernobyl, the World Trade Center, Bhopal, and Graniteville, South Carolina. Int J Environ Res Public Health 9:2894–909.

- Tennen H, Affleck G, Mendola R. (1991). Coping with smell and taste disorders. In: Getchell TV, Doty RL, Bartoshuk LM, Snow JB. (eds.) Smell and taste in health and disease. New York: Raven Press.

- Toller SV. (1999). Assessing the impact of anosmia: review of a questionnaire’s findings. Chem Senses 24:705–12.

- Vethanayagam D, Vliagoftis H, Mah D, et al. (2013). Fragrance materials in asthma: a pilot study using a surrogate aerosol product. J Asthma 50:975–82.

- Wargocki P, Wyon DP, Fanger PO. (2004). The performance and subjective responses of call-center operators with new and used supply air filters at two outdoor air supply rates. Indoor Air 14:7–16.

- Wells JR. (2005). Gas-phase chemistry of α-terpineol with ozone and OH radical: rate constants and products. Environ Sci Technol 39:6937–43.

- WHO. (2018). Household air pollution - world’s leading environmental health risk. http://www.who.int/airpollution/household/en/.

- Wing S, Horton RA, Marshall SW, et al. (2008). Air pollution and odor in communities near industrial swine operations. Environ Health Perspect 116:1362–8.

- Wolkoff P, Nielsen GD. (2017). Effects by inhalation of abundant fragrances in indoor air – an overview. Environ Int 101:96–107.