ABSTRACT

Women and workers over 50 disproportionately provide care for aging family members worldwide, including the 101 million who are care-dependent. Paid leave for adult health needs, which temporarily replaces employment income for workers providing care, can critically support both caregivers’ economic outcomes and care recipients’ wellbeing. We created quantitatively comparable data on paid leave policies that can be used to meet adult family members’ health needs in all United Nations member states. Globally, 112 countries fail to provide any paid leave that can be used to meet the serious health needs of an aging parent, spouse, or adult child. These gaps have profound consequences for older workers providing care as well as care access by aging, ill, and disabled adults.

Introduction

The ability of workers to help meet their older family members’ care needs has critical implications both for the health and wellbeing of older adults (the care recipients) as well as the economic security of older workers (often the caregivers). While specific definitions of informal caregiving vary, an analysis of three surveys conducted across 15 European countries found that between 12.93% and 29.16% of adults ages 50 and over, depending on the country (Tur-Sinai et al., Citation2020), have caregiving responsibilities for ill, aging, or disabled family members. In the U.S., around 16.8% of adults–nearly 42 million–are caring for someone over age 50; the median age of these caregivers is 51 (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, Citation2020). Morever, these responsibilities often intensify for older workers, who are more likely than those in midlife to be providing care for a spouse and/or a parent with a serious illness. Around the world, 101 million adults ages 60 and older are considered “care-dependent” by the World Health Organization (Citation2017). Further, as many adults’ working lives lengthen – with average retirement ages rising in numerous countries around the world (OECD, Citation2021a) – caregiving responsibilities for ill, aging, and disabled adult family members can extend over many years of an individual’s work life.

One policy shown to make a difference is paid leave to meet adult family members’ health needs (often referred to as paid family sick or medical leave), which temporarily replaces employment income for workers providing care. Just as paid leave following the birth of a child can improve family economic outcomes while powerfully supporting infant health, paid leave to meet the health needs of aging family members can allow adults with caregiving responsibilities to continue working while improving care access and experiences for older adults. Moreover, when structured as social insurance, paid leave can reach workers in all types of occupations, including those in the informal economy, while ensuring that providing leave of adequate length to meet common adult health needs is feasible for employers.

Further, while providing leave to care for adult family members is particularly critical to each country’s aging population, its benefits are much broader: numerous workers have caregiving responsibilities for younger adults with serious illnesses or disabilities. The provision of leave is also critical to gender equality, as women comprise the majority of caregivers for ill, aging, and disabled adult family members across countries in all regions and income groups. Indeed, an extensive literature has documented the profound implications of countries’ care policies for women’s economic outcomes throughout the life course (Addati et al., Citation2018; Folbre, Citation2006; Heymann, Citation2006; Saraceno & Keck, Citation2011).

However, far more research to date on both paid leave policies and the availability of care supports globally has focused on children than aging adults. Moreover, past studies have offered limited insights into the extent to which leave for adult caregiving is available across a wide range of family relationships. In this study, we seek to fill this gap through a quantitative analysis of paid leave to meet the health needs of adult family members worldwide. Building an original policy database covering all 193 U.N. member countries, we evaluate the availability, duration, and affordability of paid leave to meet adult family members’ health needs globally, including the extent to which countries make paid leave available to workers to care for aging and other adult family members across a diversity of family relationships. We find that 117 of 193 countries fail to provide paid leave for adult health needs. Among the 73 countries that do provide paid leave for adult health needs, only 22 provide more than 2 weeks to care for a spouse and only 17 do so for a parent which limits caregiving for major illnesses.

This paper proceeds in four sections. First, we provide a review of the literature on which workers disproportionately provide care for ill, aging, and disabled adult family members across countries, how those caregiving responsibilities affect economic outcomes, and what the evidence shows about how paid leave can make a difference. Second, we summarize our methods for creating and analyzing the data on leave worldwide. Third, we present results, focusing on the different types of leave available across countries, its accessibility to different family members, and its duration and wage replacement rate(s). Finally, we assess the implications of these findings for the health of aging people worldwide, the economic security of their caregivers, and gender and socioeconomic equality, particularly as the global population ages.

Background

Which workers have adult caregiving responsibilities?

While workers of all ages and genders help to meet the care needs of older family members, studies from a wide range of countries have found that women and older workers often bear some of the greatest responsibility for adult care. When these workers have inadequate support to meet adult caregiving needs while remaining employed, their early departures from the workforce threaten their own economic security and wellbeing in retirement. Moreover, care responsibilities can compound the existing financial vulnerabilities often experienced by women and aging adults. Even in the absence of care obligations, old age can increase poverty risks due to personal risks of illness, age discrimination in the labor market that reduces earnings capacity, and diminishing pensions. Older women are often doubly disadvantaged, as reduced earnings from leaving the workforce early for caregiving can compound gender inequalities in the labor market experienced earlier in life (Bennett & Asghar Zaidi, Citation2016; Blackburn et al., Citation2016; Gornick et al., Citation2009).

Statistics from across countries illustrate older adults’ outsized role in adult caregiving. For example, in the U.S., over half of caregivers for older adults are over the age of 50, and a third are between the ages of 50 and 64; the average spousal caregiver is 62 years old (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, Citation2015). U.S. workers above the age of 50 are also more likely than younger workers with adult care responsibilities to be providing at least 21 hours of caregiving per week. Across Europe, over 1 in 4 adults ages 50–75 have at least one living parent or parent-in-law as well as at least one adult child; of those, 9.9% are considered “sandwich” caregivers, simultaneously providing social support to both their adult children (including by caring for grandchildren) and parent(s) or parent(s)-in-law who live in a separate household, while another 16.3% are supporting their parents or parents-in-law alone (Albertini et al., Citation2022). Studies of caregivers for adults with specific illnesses find similar trends. In Japan, a survey of 300 caregivers for people with Alzheimers found that the average care recipient was 83.7 years old, while the average caregiver was 53.9; 61% of caregivers were between the ages of 50 and 64, often a critical period for workers to build retirement savings and remain employed in order to qualify for higher pension distributions (Montgomery et al., Citation2018). In Spain, a survey of nearly 130 caregivers caring for family members with end-stage metastatic cancer or advanced primary dementia found that the median caregiver’s age was 57.4 years while the median care recipient’s age was 76.7 years; 52.8% of caregivers were the adult children of the patients, while 38.6% were spouses (Costa-Requena et al., Citation2015).

Similarly, while the percentages vary by setting, women consistently provide a higher share of adult care across geographies. In Europe, multi-country studies spanning Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland estimate that women are significantly more likely to be caregivers than men, comprising between 59.7% and 62% of informal caregivers for older adults (Schmid et al., Citation2012; Stanfors et al., Citation2019; Verbakel, Citation2014). In Latin America, about 70% of informal family caregivers to disabled, ill, or older people are women (Lopez-Ruiz et al., Citation2017; Prince et al., Citation2012) including around 80% of caregivers for people with dementia in Cuba, Venezuela, Uruguay, and the Dominican Republic (Batthyány et al., Citation2017; Prince et al., Citation2012). Similarly, condition-specific studies from Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia estimate that women make up 53% to 77.2% of caregivers to disabled adults (Laks et al., Citation2016; Mickens et al., Citation2018; Perrin et al., Citation2015; Sutter et al., Citation2016). Across Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa, recent studies focused on eldercare generally as well as care for older adults with specific conditions including dementia and kidney disease show women making up a disproportionate share of caregivers in South Korea (72.9%; Lee et al., Citation2019), Japan (65.3%; Miyawaki et al., Citation2017), China (56.9%; Tang et al., Citation2013), Pakistan (68.9%; Sabzwari et al., Citation2016), and Iran (67.2%; Jafari et al., Citation2018). In North America, studies estimate that 61% of caregivers for adults in the U.S. and 68.2% of those in Canada are women (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, Citation2020; Chappell et al., Citation2015; Stanfors et al., Citation2019).

In addition to making up a greater share of caregivers, women, like older workers, devote more hours to adult care. For example, Uruguayan women caregivers under age 65 spent 56 weekly hours in unpaid health care compared to men’s 44 hours; for more general daily caregiving like help with housework, women caregivers spent 22 weekly hours and men spent 17 (Batthyány et al., Citation2017). A study spanning 11 European countries found that women represented 59.7% of caregivers for aging parents overall, but 73% of caregivers for those with “intensive needs” requiring at least weekly care (Schmid et al., Citation2012). Gender gaps grow as caregiving needs intensify over time. For example, in South Korea, daughters, daughters-in-law, and other female family members (excluding spouses) provide 24% of care services to adults ages 65 and older with limitations in daily activities, compared to just 7.3% provided by male relatives; for adults aged 80 and above, non-spousal female relatives provide 49.9% of care, compared to 13.5% by male relatives (Yoon, Citation2014).

Impact of caregiving on work outcomes

Studies from a wide range of countries have found that adult caregiving duties are associated with reduced work hours, difficulty balancing employment and caregiving commitments, and employment changes to less-demanding jobs. In Ghana, caregivers to adults with mental disabilities reported reduced employment or becoming unemployed and lacking financial resources to meet their basic needs (Ayuurebobi Ae-Ngibise et al., Citation2015). Similar findings are reported in Nigeria, where caregivers report extreme difficulty balancing paid employment with both the time and material costs of caregiving (Jack-Ide et al., Citation2013).

Generally, as care responsibilities become more intense, work hours decrease. An American study found that middle-aged women (aged 57–67) who spent any time assisting their parents spent significantly fewer hours in paid work than women who did not assist their parents, with results suggesting that each hour of help provided to their parents reduced their time spent in paid employment by 0.73 hours per year (Johnson & Lo Sasso, Citation2006). American women are significantly more likely to reduce their employment when their care responsibilities are more demanding or stressful (Barnett et al., Citation2009); women with minor care responsibilities (caring less than 10 hours per week) may be able to balance their caregiving and work responsibilities, but women with major care responsibilities (caring more than 10 hours per week, or co-residing with their care recipient) are likely to significantly reduce their work hours by between 130 and 630 hours over an 18-week period, depending on the circumstance and model (Ettner, Citation1995).

This pattern appears similar for European and Australian women. For Dutch women, a significant negative relationship was found between caretaking hours and hours spent in paid employment (Dautzenberg et al., Citation2000). Austrian women who are caregivers are significantly more likely to consider reducing their work hours or switching to part-time work than non-caregiver women; this effect was stronger as the number of caregiving hours increased (Schneider et al., Citation2013). Australian women were equally likely to become caregivers regardless of employment status, but caregiving significantly accelerated women’s departure from the labor force (regardless of socioeconomic and health variables); this effect was stronger as weekly care hours increased (Berecki-Gisolf et al., Citation2008).

Across contexts, evidence shows that adult care responsibilities play a greater role in women’s employment decisions than in men’s, even when both are providing care. In China, for example, women caretakers were significantly more likely to consider early retirement than men caretakers (Pei et al., Citation2017). In Austria, the effect sizes of care-related factors (carer status, intensity, and access to work flextime) on women’s decisions to exit the labor force or change to less-demanding jobs were generally greater than on men’s decisions (Schneider et al., Citation2013). For Canadians, family caretaking duties were a substantial influence on the decision to retire regardless of gender, though Canadian women had significantly higher relative risk of retiring for caregiving reasons than men; 21% of women retired for caretaking compared to 8% of men (Humble et al., Citation2012). In Australia, caregiver status was a strong correlate with non-employment for both men and women, but the impact was greatest for women (Noone et al., Citation2018).

These economic impacts of caregiving in turn affect caregivers’ own wellbeing in old age. For example, a 2020 survey spanning 15 countries – Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Hungary, India, Japan, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Turkey, the UK, the US–found that 1 in 5 women who retired early did so for caregiving reasons, compared to just 1 in 20 men (Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement & Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies, Citation2019). Meanwhile, the gender gap in retirement income averages 26% across OECD countries, putting women at higher risk of economic hardship (OECD, Citation2021b).

Paid leave and adult caregiving

Adult caregiving needs include both long-term care and short-term, acute, and transitional needs. The most common acute and transitional needs relate to health crises, including hospitalizations, deterioration of health, and the need to support aging family members transitioning to new settings, among others. For these acute and time-limited healthcare needs, paid family medical leave can make an enormous difference in the ability for working adults to provide care and be able to continue to have an income, have the time necessary to care for a hospitalized or acutely ill parent, have the time needed to provide support during major medical events, and still be able to return to the labor force.

Evidence from the U.S. shows that having access to employer-provided paid family caregiving leave facilitates working adults’ ability to continue to provide both regular and occasional informal care to elderly parents and relatives (Kim, Citation2021). Legislation enacted at the state level has also had demonstrated impacts on workers’ capacity to provide care themselves: in California, for example, the adoption of paid family leave (PFL), which includes “caring leave” for family members, reduced the proportion of the state’s older persons residing in nursing homes by over 11% (Arora & Wolf, Citation2018).

Meanwhile, paid leave for adult caregiving supports caregivers’ wages, labor force participation, and retention with the same employer. Recent studies found that California’s PFL law had positive effects on employment and labor force participation among adults caring for an adult family member with a disability or long-term illness, with stronger effects for women (Kang et al., Citation2019; Saad-Lessler, Citation2020; Saad-Lessler & Bahn, Citation2017). Likewise, studies of legislatively guaranteed paid elder and adult care leave in Japan and state-level paid leave policies in the U.S. found they were positively associated with other employment outcomes including job retention (Bedard & Rossin-Slater, Citation2016; Ikeda, Citation2017; Niimi, Citation2021) and hours worked (Anand et al., Citation2022). A number of studies from the U.S. have found that among those employed caregivers of adults with paid leave, a majority report that paid leave helps them to maintain their employment and income (Dembe & Partridge, Citation2011; Greenfield et al., Citation2018; La et al., Citation2021; Lum et al., Citation2010; Templeman et al., Citation2020). Studies of employer-provided paid leave and of family-friendly workplace arrangements (including paid caregiving leave), as well as a simulation model-based study, similarly have found increased job retention (Skira, Citation2015) and maintenance of employment and work hours (Hill et al., Citation2008; Pavalko & Henderson, Citation2006; Skira, Citation2015). In addition, a 2012 study using data from the U.S. Work, Family and Community Nexus (WFCN) Survey found that employed adult caregivers who had access to paid leave for family health needs were 30% less likely to experience wage or income loss than those without paid leave (Earle & Heymann, Citation2012).

At the same time, the adequacy of leave matters. Studies from the U.S. show that a large majority of employees taking leave without full pay report that it is difficult to cover basic needs while on leave, leading caregivers to shorten or even forgo taking leave when needed (Brown et al., Citation2020; Horowitz et al., Citation2017). When the only leave available for adult caregiving is unpaid, these barriers intensify: studies and surveys undertaken in Finland, Portugal, the United Kingdom and the U.S. consistently find that employees who are only able to access unpaid leave are more likely to reduce their work hours, change jobs, and leave the labor force in order to manage their care responsibilities (AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs, Citation2017; Larsen, Citation2010; Vohra-Gupta et al., Citation2021).

Likewise, the duration of leave affects whether it provides adequate coverage for common adult health needs and conditions. Chemotherapy for cancer can involve numerous treatments given at intervals across six months. In low- and middle-income countries, hospitalization following a stroke averages 5–20 days (Kaur et al., Citation2014). While a caregiver may be able to work intermittently while caring for an adult family member who has been hospitalized or is recovering, one or two weeks of leave may often be insufficient for providing adequate support.

In short, evidence from across countries shows that paid leave for adult caregiving – particularly when it replaces an adequate share of a worker’s regular income – can powerfully support family caregivers to meet the short-term and recurring health needs of ill and aging family members while markedly improving the economic outcomes of women, who remain the primary caregivers for older adults around the world. Nevertheless, there has been little data available on the prevalence of policies that support working adults caring for aging parents and other adult family members with acute health needs. This study examines the availability of paid leave across all 193 countries.

Methods

Data

To construct data on legislative approaches to paid leave for adult family members’ health needs, a team of researchers at our center, the WORLD Policy Analysis Center, conducted a systematic review of labor and social security legislation in place as of January 2022 across all 193 United Nations (U.N.) member states (United Nations, Citationn.d.). We focused on U.N. countries because: 1) the U.N. is the largest intergovernmental organization and its membership represents a standardized list of countries globally, and 2) by nature of their U.N. membership all U.N. countries have agreed to protect the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including the rights to “just and favorable conditions of work” and “a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including the right to security in the event of … sickness, disability, … [or] old age.” The primary source for the data was original, full-text legislation sourced through the International Labor Organization (ILO)’s NATLEX database supplemented with legislation sourced from country government websites, law libraries, and other sources. Information was also corroborated using data from Social Security Programs Throughout the World, the Mutual Information System on Social Protection, and the Mutual Information System on Social Protection of the Council of Europe.

For each country, two researchers analyzed legislation in full. Whenever possible, legislation was read in its original language by a team fluent in English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and other languages. Translation services were used as needed when legislation was unavailable in an official translation. Researchers then reconciled their answers and discussed any difficult cases as a team to ensure a comparable method was used across all 193 countries. Once coding was complete, additional quality checks were conducted, including outlier and randomized checks.

Policy indicators

Identifying leave

Our analysis of paid leave included both leave provided specifically for adult family members’ health needs and other types of leave that could be used to meet adult family members’ health needs. Leave specifically for adult family members’ health needs included legislatively mandated leave paid by employers as well as social security-provided benefits for workers to care for family members’ health needs (often referred to as family sick or medical leave). We did not include paid sick or medical leave generally provided for employees’ personal health needs unless it explicitly referenced caring for other people. Our analysis of other types of leave that could be used to meet adult family members’ health needs included emergency leave, family needs leave, discretionary leave, or casual leave. We captured the level of leave guaranteed nationally. When paid leave varied sub-nationally, the least generous policy was captured. That is, if one state did not guarantee paid leave for adult family members’ health needs, we did not capture a guarantee of paid leave for the country as a whole. Paid leave provided by collective bargaining was only included when it broadly applied to the private sector. Provisions that solely applied to the public sector were excluded because in many countries they do not cover the majority of workers.

Family members covered

In many countries, legislation distinguishes among family members for whom leave is available. To understand whether paid leave provisions cover a diverse range of relationships, we separately assessed whether paid leave policies covered leave to care for spouses, parents, adult children, grandparents, partners, siblings, or parents-in-law. Family members were coded as covered both when the legislation directly specified the family member and when the family member was included in a broader category. Countries that only provide leave to “dependent” adults were not included in family member specific analyses because of the inability to determine who is covered. We considered all family members to be covered when legislation did not explicitly limit leave availability based on type of relationship. We separately distinguished between provisions that required family members to live in the same household and those that did not. We considered “immediate family” and “relatives to the first degree” to include spouses, parents, adult children, and siblings. References to “cohabitant partner,” “unmarried spouse,” “defacto partner,” “person who resides with the employee in a relationship of domestic dependency” or “common-law partner” were captured as “partner.” Relatives to the second degree were assumed to cover the same family members as first degree, as well as grandparents. We considered “blood relatives” to be parents, grandparents, adult children, and siblings. “Ascendants” or “predecessors” included parents and grandparents. “Descendants” included adult children.

Duration of leave

We examined the duration of leave available to meet adult family members’ health needs, categorizing the duration of leave available as “1 week or less,” “1.1–2 weeks,” “2.1–6 weeks,” and “more than 6 weeks.” When multiple forms of leave were available, such as leave for serious illness and leave to provide end-of-life care, we captured the longest form of leave available. We considered leave to be available for more than 6 weeks when legislation specified it was available “until recovery” or “for the duration of hospitalization.”

Wage replacement rates

We categorized the wage replacement rate of paid leave based on the percentage of wages caregivers were guaranteed while on leave. Higher wage replacement rates make taking leave more affordable for low-income families, but are also more costly to administer. In some countries, wage replacement rates vary whether based on the type of leave being taken (end-of-life versus more general leave), a worker’s tenure or contributions to a social security system, or other factors. To account for this, we separately coded the minimum and maximum wage replacement rate. Finally, a small number of countries did not base payment on a worker’s wages, but instead guaranteed workers a flat rate payment or a percentage of unemployment benefits. We separately categorized these approaches.

Analysis

Variables were constructed and analyzed using Stata 14. Differences were assessed by country income group using the World Bank’s country and lending groups as of 2020.

Results

Types of leave available

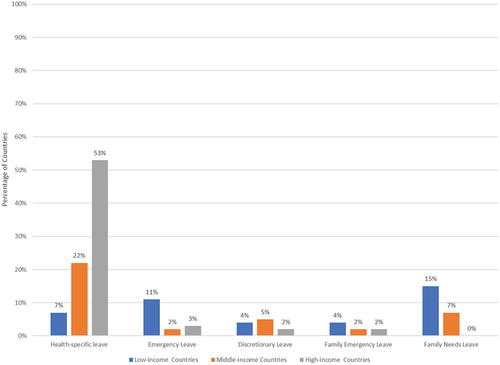

Countries guaranteed workers five different types of leave, sometimes individually and sometimes in combination, to meet the needs of adult family members including aging family members, adults with disabilities, and adults with serious health conditions or other pressing needs. These types of leave included: 1) leave that was specific to meeting health needs, 2) leave that was specific to meeting the needs of family members, but not limited to health, 3) leave reserved for emergencies, 4) leave that was only available for family emergencies, and 5) broader discretionary leave. The most common types of leave that countries provided were health-specific leave and leave to meet the needs of family members more broadly. High-income countries were more likely to provide paid health-specific leave than low-income countries (53% compared to 7%, p < .01). Low-income countries were more likely to provide paid family needs leave than high-income countries (15% compared to 0%, p < .01) (see ).

Leave availability for different family members

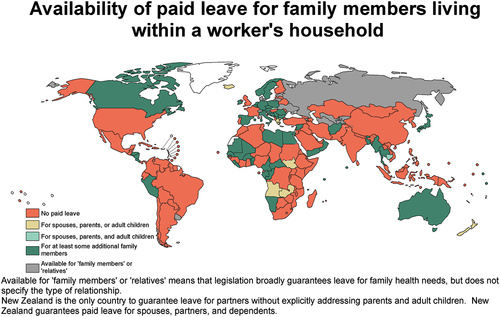

Globally, the majority of countries (112 of 193 countries) failed to guarantee any paid leave that could be used to meet the health needs of a spouse, parent, or adult child.Footnote1 When countries did provide paid leave, the most common approach globally and across the Americas, Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Pacific was to provide paid leave for spouses, parents, adult children, and at least one additional family member (see ). When examining paid leave policies for family members living in the same household, high-income countries were more likely to guarantee access to paid leave for spouses, the most frequently covered family member, than middle-income countries (p < .05), but differences were not statistically significant for low-income countries.

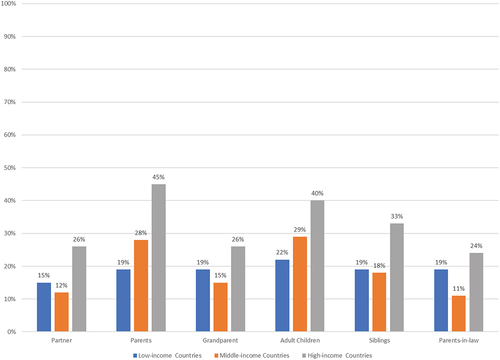

Across all family member relationship types, fewer countries guaranteed paid leave to care for family members living outside the worker’s household, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Whereas 45% of high-income countries guaranteed paid leave to care for parents living outside the household, only 28% of middle-income (p < .05) and 19% of low-income countries did so (p < .05) (see ). Paid leave availability to care for partners, parents-in-law, and grandparents were lowest across all income levels.

Figure 3. Availability of paid leave for family members living outside the household by country income level.

Duration of leave available

There was a marked variation in the length of leave available. While all leaves tended to be time-limited, the most likely leaves to be available for lengthy periods of time were the health-specific leaves. Emergency, family emergency, discretionary, and family needs leaves were typically two weeks or less.

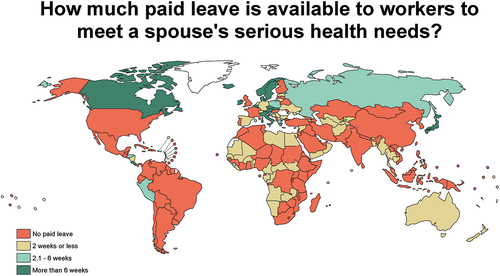

In the case of health-specific leave, 16 or more countries guaranteed more than two weeks of leave to care for the health needs of a spouse, parent, or adult child, respectively. Somewhat fewer countries provided more than two weeks of leave to care for a partner, sibling, parent-in-law, or grandparent. In some countries, leave was only available to care for family members living within the same household (see ).

Table 1. Duration of Health-Specific Paid Leave by Family Member

Combining all kinds of leave available in each country, including the emergency and family needs leave as well as health-specific leaves, produced little change in the number of countries providing more than two weeks of leave, with 22 countries providing more than two weeks of leave to care for a spouse, 18 doing so for a parent, and 20 for adult children (see ). A larger change was seen in the number of countries providing up to 2 weeks of paid leave. Whereas only 9 countries provided 2 weeks or less of health-specific paid leave to care for a partner and 17 did so for a sibling, 29 countries made up to 2 weeks of paid leave available that could be used to care for a partner and 37 countries took an approach that could be used to care for a sibling.

Table 2. Duration of Any Paid Leave Available to Meet Health Needs by Family Memberc

Due in part to differences in the types of leave provided across country income level, differences in the duration of paid leave were marked (see ). Whereas nearly a fifth of high-income countries guaranteed more than 6 weeks of paid leave that could be used to care for an ill spouse, no low-income country (p = .01) and only one middle-income countries did so (p <.0.01). Only one low-income country that made paid leave available to care for a spouse guaranteed more than two weeks.

Wage replacement rate during leave

While the health-specific leaves tended to be longer in duration, they were somewhat less likely to provide full wages. The shorter emergency, discretionary, and family needs leaves were at full wages. Often the health leave provided a range of wage replacement rates depending on a number of factors. Nevertheless, in the majority of cases wage replacement was 80–100% (see ).

Table 3. Wage Replacement Rate of Health-Specific Leave by Family Member for Countries with Paid Leave

Table 4. Wage Replacement Rate of Any Paid Leave Available to Meet Family Health Needs by Family Member

Discussion

Globally, 112 countries fail to provide any paid leave that can be used to meet the serious health needs of an aging parent, spouse, or adult child. Even more fail to provide paid leave to care for a sibling, parent-in-law, or partner. Moreover, when paid leave is available, it tends to be relatively short: 171 countries fail to provide more than two weeks of paid leave to support an aging parent’s health needs.

While high-income countries were the most likely to provide paid leave specifically to meet family members’ health needs, it was still the case that only 53% of high-income countries did so. Overall, nearly a third of countries provided this leave and amongst middle-income countries less than one in four provided workers leave specifically for family members’ health needs.

When leave for adult care needs is unavailable, the consequences disproportionately affect aging adults – both the workers whose caregiving needs often intensify as they age and the older adults in need of family support to meet care needs. But the consequences also affect people across the life course. For example, in addition to those caring for aging parents and spouses, millions of workers require leave to care for adult children with serious illnesses or disabilities. Further, the impacts on gender equality are profound, as was starkly visible amidst the pandemic. In the absence of adequate paid leave, family members who provided care for aging and ill family members, disproportionately women, lost jobs by the millions. A 2021 analysis from the ILO found that globally, women were 40% more likely than men to lose their jobs in 2020, and that women would hold 13 million fewer jobs in 2021 compared to 2020 (ILO Citation2021).

Even when it is provided, a number of factors affect leave’s feasibility, and thus its impacts for both care recipients and care providers. The adequacy of the wage replacement rate, for instance, can markedly shape both the ability of caregivers to take leave and whether leave is shared equitably across gender, with broader consequences for women’s economic outcomes. When leave policies replace only a small share of income, the lower earner in a household – disproportionately women due to persisting gender wage gaps – will be more likely to take it. Moreover, low wage replacement rates exacerbate socioeconomic inequalities since workers with lower incomes and fewer assets will be less able to afford a reduction in pay. While most countries offered a wage replacement rate of at least 80% for adult health needs leave, in some, the maximum wage replacement was far lower.

These consequences for health and equality are borne not just by individual households but by entire economies. At the same time, the opportunity to improve both health and economic outcomes through stronger investments in support for aging adults’ care needs is immense. For example, one study from the Economist and the AARP estimated that by fully supporting caregivers ages 50 and older to remain in the work force, the U.S. could increase its GDP by $1.7 trillion (5.5%) by 2030 (AARP & EIU, Citation2021). The implications are significant across economies. As populations are aging in low- and middle-income countries, leave for adult caregiving will become an increasingly important policy for both meeting care needs and for sustaining caregivers’ ability to work.

Designing leave to ensure it can be taken for a wide range of family members has two important benefits. First, family members are better positioned to share responsibilities for providing care. When leave policy covers both parents and parents-in-law, spouses can share taking that leave. When leave policies cover siblings as well as spouses or partners, siblings have the opportunity to share what can be particularly meaningful time with their immediate family members as well as provide respite to spouses and partners. Providing this flexibility does not mean that more total leave will be taken but rather that it can be broadly shared. Second, it ensures that every person can receive care in the context of different family structures and relationships. Those with and without adult children, in legally recognized marriages or partnerships, in informal partnerships, and without a partner, can all receive care.

In the case of life-threatening and terminal illnesses, lengthier leave may be needed. Likewise, for caregivers of adults with multiple chronic conditions, or for those caring for any of the 101 million older adults who are care-dependent, one or two weeks of leave per year is likely insufficient to meet annual health needs in the absence of other extensive care supports. Across countries, the most common way to provide for lengthier leaves is through social insurance. The provision of social insurance reduces the economic burden on individual employers and in particular ensures that leaves are affordable to small employers, which can be more affected by an individual lengthy leave when it is not averaged out over a large number of employees. Short-term leave is commonly provided by employers themselves. This reduces administrative costs and is more readily affordable to all firms.

Limitations

This study has limitations. In particular, a detailed look at the availability of leave for adult caregiving for workers in the informal economy is needed. It is also worth examining in detail the mechanisms by which a worker’s eligibility for leave is determined, as restrictions based on minimum tenure, contributions, and work hours, among other common eligibility criteria, can significantly affect leave coverage.

Conclusion

Economic productivity markedly benefits when people of all genders can continue to fully participate in the economy across the life course, including when older workers can keep their jobs when they need to care for adult family members and aging parents with serious illnesses. Guaranteeing that people can continue to work and can return to work after leaves not only increases income to families but reduces costly turnover, recruitment, training, and loss of experienced employees. Ensuring all members of society can provide care to family members improves health outcomes, lowers overall health cost by shortening duration of illness, and reduces gender inequality. In short, the potential benefits to older workers, to health, and to society, of paid leave to care for adult family members are enormous and the need to address it is great.

Key points

Women and workers over 50 provide the majority of informal care for older adults.

Paid leave to provide care supports caregivers’ employment and aging adults’ health.

Yet, 112 countries fail to provide leave for parents, spouses, or adult children.

While high-income countries were the most likely, only 53% provided needed leave.

These gaps threaten the wellbeing of aging adults both providing and receiving care.

Data Availability

All data will be available and freely downloadable at www.worldpolicycenter.org at the time of publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Uruguay covers “dependent” family members who also have a “disability or terminal illness” and is excluded from relationship-specific counts.

References

- AARP & EIU. (2021). The economic impact of supporting working family caregivers. AARP Thought Leadership and the Economist Intelligence Unit. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/econ/2021/longevity-economy-working-caregivers.doi.10.26419-2Fint.00042.006.pdf

- AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015: Vol. Research report. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/2015_CaregivingintheUS_Final-Report-June-4_WEB.pdf

- AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving. (2020). Caregiving in the U.S. 2020: Vol. Research report. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/full-report-caregiving-in-the-united-states-01-21.pdf

- Addati, L., Cattaneo, U., Esquivel, V., & Valarino, I. (2018). Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work. International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_633135/lang–en/index.htm

- Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement & Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies. (2019). The new social contract: Achieving retirement equality for women. https://transamericacenter.org/docs/default-source/global-survey-2019/tcrs2020_sr_new-social-contract-women-retirement-equality.pdf

- Albertini, M., Tur-Sinai, A., Lewin-Epstein, N., & Silverstein, M. (2022). The older sandwich generation across European welfare regimes: Demographic and social considerations. European Journal of Population, 38(2), 273–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-022-09606-7

- Anand, P., Dague, L., & Wagner, K. (2022). The role of paid family leave in labor supply responses to a spouse’s disability or health shock. Journal of Health Economics. 83, 102621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2022.102621

- AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs. (2017). Long-term caregiving: The types of care older Americans provide and the impact on work and family. http://longtermcare.gov/the-basics/

- Arora, K., & Wolf, D. A. (2018). Does paid family leave reduce nursing home use? The California experience. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 37(1), 38–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22038

- Ayuurebobi Ae-Ngibise, K., Christian, V., Doku, K., Asante, K. P., & Owusu-Agyei, S. (2015). The experience of caregivers of people living with serious mental disorders: A study from rural Ghana. Global Health Action, 8 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.26957

- Barnett, R. C., Gareis, K. C., Gordon, J. R., & Brennan, R. T. (2009). Usable flexibility, employees’ concerns about elders, gender, and job withdrawal. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 12(1), 50–71. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/10887150802665356

- Batthyány, K., Genta, N., & Perrotta, V. (2017). El aporte de las familias y las mujeres a los cuidados no remunerados en salud en Uruguay [The contribution of families and women to unpaid health care in Uruguay]. Revista Estudos Feministas, 25(1), 187–213. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9584.2017v25n1p187

- Bedard, K., & Rossin-Slater, M. (2016). The economic and social impacts of paid family leave in California: Report for the California employment development department. California Employment Development Department. https://www.edd.ca.gov/disability/pdf/PFL_Economic_and_Social_Impact_Study.pdf

- Bennett, R., & Asghar Zaidi, A. (2016). Ageing and development: Putting gender back on the agenda. International Journal on Ageing in Developing Countries, 1(1), 5–19. https://www.inia.org.mt/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Complete-Issue.pdf

- Berecki-Gisolf, J., Lucke, J., Hockey, R., & Dobson, A. (2008). Transitions into informal caregiving and out of paid employment of women in their 50s. Social Science & Medicine, 67(1), 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.031

- Blackburn, R. M., Jarman, J., & Racko, G. (2016). Understanding gender inequality in employment and retirement. Contemporary Social Science, 11(2–3), 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2014.981756

- Brown, S., Herr, J., Roy, R., & Klerman, J. A. (2020). Employee and worksite perspectives of the family and medical leave act: Results from the 2018 surveys. United States Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/WHD_FMLA2018SurveyResults_FinalReport_Aug2020.pdf

- Chappell, N. L., Dujela, C., & Smith, A. (2015). Caregiver well-being: Intersections of relationship and gender. Research on Aging, 37(6), 623–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027514549258

- Costa-Requena, G., Val, M. E., & Cristòfol, R. (2015). Caregiver burden in end-of-life care: Advanced cancer and final stage of dementia. Palliative & Supportive Care, 13(3), 583–589. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951513001259

- Dautzenberg, M. G. H., Diederiks, J. P. M., Philipsen, H., Stevens, F. C. J., Tan, F. E. S., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. J. F. J. (2000). The competing demands of paid work and parent care: Middle-aged daughters providing assistance to elderly parents. Research on Aging, 22(2), 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027500222004

- Dembe, A. E., & Partridge, J. S. (2011). The benefits of employer-sponsored elder care programs: Case studies and policy recommendations. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 26(3), 252–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2011.589755

- Earle, A., & Heymann, J. (2012). The cost of caregiving: Wage loss among caregivers of elderly and disabled adults and children with special needs. Community, Work & Family, 15(3), 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2012.674408

- Ettner, S. L. (1995). The impact of “parent care” on female labor supply decisions. Demography, 32(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061897

- Folbre, N. (2006). Measuring care: Gender, empowerment, and the care economy. Journal of Human Development, 7(2), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880600768512

- Gornick, J. C., Munzi, T., Sierminska, E., & Smeeding, T. M. (2009). Income, assets, and poverty: Older women in comparative perspective. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 30(2–3), 272–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/15544770902901791

- Greenfield, J. C., Hasche, L., Bell, L. M., & Johnson, H. (2018). Exploring how workplace and social policies relate to caregivers’ financial strain. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 61(8), 849–866. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2018.1487895

- Heymann, J. (2006). Forgotten families: Ending the growing crisis confronting children and working parents in the global economy. Oxford University Press.

- Hill, T., Thomson, C., Bittman, M., & Griffiths, M. (2008). What kinds of jobs help carers combine care and employment? Family Matters, 80, 27–32. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/ielapa.482084586386439

- Horowitz, J., Parker, K., Graf, N., & Livingston, G. (2017, March 23). Americans widely support paid family and medical leave, but differ over specific policies. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2017/03/23/americans-widely-support-paid-family-and-medical-leave-but-differ-over-specific-policies/

- Humble, Á. M., Keefe, J. M., & Auton, G. M. (2012). Caregivers’ retirement congruency: A case for caregiver support. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 74(2), 113–142. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.74.2.b

- Ikeda, S. (2017). Family care leave and job quitting due to caregiving: Focus on the need for long-term leave. Japan Labor Review, 14(1), 25–44. https://www.jil.go.jp/english/JLR/documents/2017/JLR53_ikeda.pdf

- ILO. (2021). Building forward fairer: Women’s rights to work and at work at the core of the COVID-19 recovery. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---gender/documents/publication/wcms_814499.pdf

- Jack-Ide, I. O., Uys, L. R., & Middleton, L. E. (2013). Caregiving experiences of families of persons with serious mental health problems in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. International Journal of Mental Health, 22(2), 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00853.x

- Jafari, H., Ebrahimi, A., Aghaei, A., & Khatony, A. (2018). The relationship between care burden and quality of life in caregivers of hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrology, 19(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12882-018-1120-1/TABLES/3

- Johnson, R. W., & Lo Sasso, A. T. (2006). The impact of elder care on women’s labor supply. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 43(3), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.5034/inquiryjrnl_43.3.195

- Kang, J. Y., Park, S., Kim, B., Kwon, E., Cho, J., & Pruchno, R. (2019). The effect of California’s paid family leave program on employment among middle-aged female caregivers. The Gerontologist, 59(6), 1092. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny105

- Kaur, P., Kwatra, G., Kaur, R., & Pandian, J. D. (2014). Cost of stroke in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. International Journal of Stroke, 9(6), 678–682. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12322

- Kim, S. (2021). Access to employer-provided paid leave and eldercare provision for older workers. Community, Work & Family, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2021.1885346

- La, H. T., Hua, C. L., & Brown, J. S. (2021). The relationship among caregiving duration, paid leave, and caregiver burden. In P. N. Claster & S. L. Blair (Eds.), Aging and the family: Understanding changes in structural and relationship dynamics (Vol. 17, pp. 83–96). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1530-353520210000017005

- Laks, J., Goren, A., Dueñas, H., Novick, D., & Kahle-Wrobleski, K. (2016). Caregiving for patients with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia and its association with psychiatric and clinical comorbidities and other health outcomes in Brazil. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(2), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4309

- Larsen, T. P. (2010). Flexicurity from the individual’s work-life balance perspective: Coping with the flaws in European child- and eldercare provision. Journal of Industrial Relations, 52(5), 575–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185610381562

- Lee, S. M., Lee, Y., Choi, S. H., Lim, T. S., & Moon, S. Y. (2019). Clinical and demographic predictors of adverse outcomes in caregivers of patients with dementia. Dementia and Neurocognitive Disorders, 18(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.12779/DND.2019.18.1.10

- Lopez-Ruiz, M., Benavides, F. G., Vives, A., & Artazcoz, L. (2017). Informal employment, unpaid care work, and health status in Spanish-speaking Central American countries: A gender-based approach. International Journal of Public Health, 62(2), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00038-016-0871-3

- Lum, W., Sato, S., & Arnsberger, P. (2010). Native Hawaiian male caregivers: Patterns of service use and their effects on public policies. Journal of Indigenous Voices in Social Work, 1(2), 1–18. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/18772

- Mickens, M. N., Perrin, P. B., Aguayo, A., Rabago, B., Macías-Islas, M. A., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2018). Mediational model of multiple sclerosis impairments, family needs, and caregiver mental health in Guadalajara, Mexico. Behavioral Neurology 2018, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8929735

- Miyawaki, A., Tomio, J., Kobayashi, Y., Takahashi, H., Noguchi, H., & Tamiya, N. (2017). Impact of long-hours family caregiving on non-fatal coronary heart disease risk in middle-aged people: Results from a longitudinal nationwide survey in Japan. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 17(11), 2109–2115. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13061

- Montgomery, W., Goren, A., Kahle-Wrobleski, K., Nakamura, T., & Ueda, K. (2018). Alzheimer’s disease severity and its association with patient and caregiver quality of life in Japan: Results of a community-based survey. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0831-2

- Nimi, Y. (2021). Juggling paid work and elderly care provision in Japan: Does a flexible work environment help family caregivers cope?. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 62, 101171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2021.101171

- Noone, J., Knox, A., Mackey, M., Mackey, M., & Mackey, M. (2018). An analysis of factors associated with older workers’ employment participation and preferences in Australia. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(6), 2524. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02524

- OECD. (2021a). Pensions at a Glance 2021: OECD and G20 indicators. https://doi.org/10.1787/ca401ebd-en

- OECD. (2021b). Governments need to address the gender gap in retirement savings arrangements. https://www.oecd.org/finance/private-pensions/governments-need-to-address-the-gender-gap-in-retirement-savings-arrangements.htm

- Pavalko, E. K., & Henderson, K. A. (2006). Combining care work and paid work: Do workplace policies make a difference? Research on Aging, 28(3), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027505285848

- Pei, X., Luo, H., Lin, Z., Keating, N., & Fast, J. (2017). The impact of eldercare on adult children’s health and employment in transitional China. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 32(3), 357–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-017-9330-8

- Perrin, P. B., Panyavin, I., Paredes, A. M., Aguayo, A., Macias, M. A., Rabago, B., Fulton Picot, S. J., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2015). A disproportionate burden of care: Gender differences in mental health, health-related quality of life, and social support in Mexican multiple sclerosis caregivers. Behavioral Neurology, 2015, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/283958

- Prince, M., Brodaty, H., Uwakwe, R., Acosta, D., Ferri, C. P., Guerra, M., Huang, Y., Jacob, K., Llibre Rodriguez, J. J., Salas, A., Sosa, A. L., Williams, J. D., Jotheeswaran, A. T., & Liu, Z. (2012). Strain and its correlates among carers of people with dementia in low-income and middle-income countries. A 10/66 dementia research group population-based survey. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(7), 670–682. https://doi.org/10.1002/GPS.2727

- Saad-Lessler, J. (2020). How does paid family leave affect unpaid care providers? The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 17, 100265. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JEOA.2020.100265

- Saad-Lessler, J., & Bahn, K. (2017). The importance of paid leave for caregivers labor force participation effects of California’s comprehensive paid family and medical leave. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/importance-paid-leave-caregivers/

- Sabzwari, S., Munir Badini, A., Fatmi, Z., Jamali, T., & Shah, S. (2016). Burden and associated factors for caregivers of the elderly in a developing country. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal = La Revue de Sante de la Mediterranee Orientale = al-Majallah al-sihhiyah li-sharq al-mutawassit, 22(6), 394–403. https://doi.org/10.26719/2016.22.6.394

- Saraceno, C., & Keck, W. (2011). Towards an integrated approach for the analysis of gender equity in policies supporting paid work and care responsibilities. Demographic Research, 25, 371–406. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2011.25.11

- Schmid, T., Brandt, M., & Haberkern, K. (2012). Gendered support to older parents: Do welfare states matter? European Journal of Ageing, 9(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10433-011-0197-1/TABLES/2

- Schneider, U., Trukeschitz, B., Mühlmann, R., & Ponocny, I. (2013). “Do I stay or do I go?” Job change and labor market exits intentions of employees providing informal care to older adults. Health Economics, 22(10), 1230–1249. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2880

- Skira, M. M. (2015). Dynamic wage and employment effects of elder parent care. International Economic Review, 56(1), 63–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/iere.12095

- Stanfors, M., Jacobs, J. C., & Neilson, J. (2019). Caregiving time costs and trade-offs: Gender differences in Sweden, the UK, and Canada. SSM - Population Health, 9, 100501. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSMPH.2019.100501

- Sutter, M., Perrin, P. B., Peralta, S. V., Stolfi, M. E., Morelli, E., Obeso, L. A. P., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2016). Beyond strain: Personal strengths and mental health of Mexican and Argentinean dementia caregivers. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(4), 376–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615573081

- Tang, B., Harary, E., Kurzman, R., Mould-Quevedo, J. F., Pan, S., Yang, J., & Qiao, J. (2013). Clinical characterization and the caregiver burden of dementia in China. Value in Health Regional Issues, 2(1), 118–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.VHRI.2013.02.010

- Templeman, M. E., Badana, A. N., & Haley, W. E. (2020). The relationship of caregiving to work conflict and supervisor disclosure with emotional, physical, and financial strain in employed family caregivers. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(7–8), 698–707. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264319848579

- Tur-Sinai, A., Teti, A., Rommel, A., Hlebec, V., & Lamura, G. (2020). How many older informal caregivers are there in Europe? Comparison of estimates of their prevalence from three European surveys. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249531

- United Nations. (n.d.). Member states. Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://www.un.org/en/about-us/member-states

- Verbakel, E. (2014). Informal caregiving and well-being in Europe: What can ease the negative consequences for caregivers? Journal of European Social Policy, 24(5), 424–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928714543902

- Vohra-Gupta, S., Kim, Y., & Cubbin, C. (2021). Systemic racism and the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA): Using critical race theory to build equitable family leave policies. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 8(6), 1482–1491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00911-7/Published

- World Health Organization. (2017). Evidence profile: caregiver support-Integrated care for older people. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MCA-17.06.01

- Yoon, J. (2014). Counting care work in social policy: Valuing unpaid child- and eldercare in Korea. Feminist Economics, 20(2), 65–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2013.862342