ABSTRACT

In China, rapid aging of the population is driving up demand for healthcare and long-term care services for older adults. This special issue of the Journal of Aging & Social Policy features a collection of studies that provided timely analyses and fresh insights into a wide range of policy relevant topics concerning long-term care for older adults in China. In this introductory article, we orient readers to these studies organized under four themes: migration, caregiving, and elder care challenges; long-term care service users, frontline workers, and workforce challenges; unmet needs across the care span in healthcare, long-term care, and end of life care; and long-term care financing. We highlight major findings and contributions of each study and provide perspectives on key issues within China’s evolving healthcare and social policy contexts. Collectively, these studies contribute to building scientific evidence where it is lacking and supporting evidence-based long-term care policymaking and practice to meet the mounting challenges of population aging in China.

By the end of 2022, China registered a total population of just over 1.41 billion, a decrease of 0.85 million, or − 0.6%, from 2021 (State Council Information Office, Citation2023). This natural decrease in population, as a result of deaths outnumbering live births in a year, has been the first time over the past six decades – the last occurrence was in 1960, amid the great famine in China during 1959–1961 (Smil, Citation1999). This also marks the turning point of a demographic shift that sets China on path to negative population growth in the coming decades, according to projections (United Nations, Citation2022).

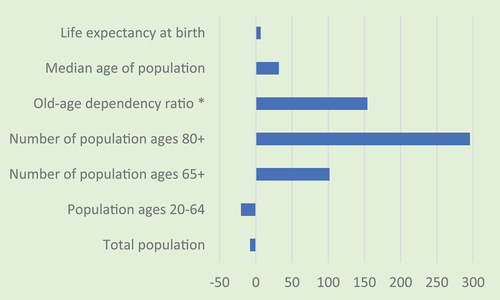

While its total population is shrinking, China is aging fast. As of 2022, nearly 196 million people were aged 65 years or older, accounting for 13.7% of the total population; the number of older adults in China is projected to more than double, to exceed 395 million, or 30.1% of the total population, by 2050 (United Nations, Citation2022). In less than 30 years from now, from 2022 to 2050, the life expectancy at birth for China’s population will continue to rise, by 6.6% (from 78.6 to 83.8 years), median age of population by 31.7% (from 38.5 to 50.7), the number of the oldest old (those ages 80 years and over) by 295.5% (from approximately 34 million to 135 million), and the old-age dependency ratio by 154.1% (from 22 to 55 people ages 65 years and over for every 100 working-age people ages 20–64) (United Nations, Citation2022), as shown in .

Figure 1. Selected demographic indicators in China, % change 2022–2050.

Not only is China’s population aging at an unprecedented pace, it is also becoming more mobile than ever and urbanizing rapidly. Indeed, over the past 40 years China has transformed from a predominantly agrarian, earthbound country to an urbanized society, driven by massive migration of the population from rural to urban areas. China’s latest (seventh) census counted 375.82 million internal migrants, representing roughly one in every four people in the country (National Bureau of Statistics of China, Citation2021). Internal migrants are defined as individuals whose current residence is different from where their official hukou—household registration status – is registered and who have left their official hukou residence for at least six months. The proportion of the population living in cities and towns jumped from barely 20% around 1980 and 36% in 2000 (National Bureau of Statistics of China, Citation2021) to over 65% in 2022 (State Council Information Office, Citation2023), and it is projected to reach 80% by 2050 (United Nations, Citation2018). The out-migration of younger adults is hollowing out rural villages across China and leaving millions of rural elders behind.

These demographic and socioeconomic trends are weakening China’s traditional family-based old-age support system. Yet rapid aging of the population, coupled with the rising burden of noncommunicable diseases as well as physical and cognitive impairments, is driving up demand for healthcare and formal long-term care services for older adults whose needs can no longer be met by unpaid family caregivers (Feng et al., Citation2020; Wu et al., Citation2021). Although over the past 20 years China has made significant strides in the provision of social security, healthcare, and long-term care services, the existing service infrastructure and delivery systems are far from adequate to meet the growing needs of an aging population.

Research and policy efforts to grapple with the ramifications and multifaceted challenges of population aging and ongoing socioeconomic transformations in China have gathered momentum in recent years. In this special issue of the Journal of Aging & Social Policy, we put together nine studies that provided timely analyses and fresh insights into a wide range of policy relevant issues concerning long-term care in China. The topics encompass internal migration and its impact on caregiving arrangements, utilization of and experience with institutional and community-based long-term care services, workforce challenges in home-based long-term care, unmet needs among community-living older adults with disabilities, end of life care, effect of welfare receipt on healthcare use and related expenditures among older households, and China’s public social insurance pilot programs to bolster long-term care financing. In what follows, we briefly introduce these studies, highlight their key findings and contributions, and where appropriate, extend our perspectives on important themes emerging from these studies within China’s evolving healthcare and social policy contexts.

Migration, caregiving, and elder care challenges

In an in-depth qualitative study, He et al. (Citation2021) explore the experiences of 24 rural migrant workers who had to return to their hometown to provide care for seriously ill older parents diagnosed with cancer. The authors used a culturally integrated Foucauldian discourse analysis approach to understanding how participants narrated their caregiving experiences and how they reconciled the cultural mandate of filial piety and practical challenges in fulfilling it. The study found that although all participants showed a strong commitment toward filial piety out of naturalness, they also acknowledged many tough challenges unique to migrant workers juggling their filial responsibilities and precarious urban employment often far away from home. Echoing the sentiments and views of study participants, the authors argue that merely encouraging family members to maintain and improve filial care for rural elders will not be sufficient or effective. Instead, they urge policymakers in China to recognize rural migrant worker caregivers’ extraordinary caregiving efforts and support their needs through legislating accommodative workplace benefits and regulations, improving pensions, and increasing health care subsidies. The authors further urge for a pragmatic turn in policymaking to recognize the important role of family caregivers and to provide practical support for their caregiving efforts.

To help advance research on the far-reaching yet understudied impact of rural-to-urban migration on caregiving arrangements for Chinese older adults – not only those left-behind in rural areas but also those living in the cities—Xu et al. (Citation2021) compiled an inventory of longitudinal aging survey datasets from mainland China. After carefully reviewing all existing large-scale and publicly available datasets that contained measures related to migration and caregiving, the authors extracted and assessed key characteristics of each dataset, including study design, sample size, and measures. Ultimately, they identified seven high-quality datasets that can be used to address research gaps in this area, five of which feature nationally representative samples. They note that measures of migration and caregiving vary across data sources. Some datasets contain information on the migration history of older adults, whereas others focus on migration of adult children. They further assessed measures of the type, source, and amount of caregiving activities across the datasets. This inventory provides a timely guide for researchers interested in using these datasets to tackle important questions at the intersection of migration, elder care, and evidence-based development of long-term care services and policies. This study would facilitate research efforts to harmonize the datasets to address these research questions.

Long-term care service users, frontline workers, and workforce challenges

Use of institutional long-term care among older adults in China is still limited, and much less is known about the risk factors for such use. In the study by J. Wang et al. (Citation2020), the authors used four waves of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) to examine how different care arrangements affected the age of institutionalization (entrance to a long-term care facility) among Chinese community-living older adults. Their results indicate that compared to older adults who were primarily cared for by spouses, those whose primary caregivers were sons and daughters-in-law tended to be institutionalized at a later age, and in contrast, those whose primary caregivers were other relatives and friends or domestic helpers, and those who had no caregivers at all tended to be institutionalized at an earlier age. Reflecting on the implications of their findings, the authors remind readers of a discordant reality in which the number of older adults living in empty-nest families is rapidly increasing, and family support for older adults shrinking due to fewer children, outmigration of adult children from rural to urban areas, and rising employment of women. They also highlight the urgent need for policy efforts to address the acute shortage of skilled long-term care workers, including well-trained domestic helpers who could play an important role in assisting disabled older adults to live safely at home and delay institutionalization, or avoid it altogether.

Indeed, domestic helpers (known as bǎomǔ or jiāzhèng fúwùyuán in Chinese) have become a major frontline workforce in home-based long-term care in urban China, a subject of the study by J. Wang et al. (Citation2022). The authors note that most domestic helpers are women ages 30–50 years with limited education who are rural migrants or laid-off urban workers. Based on an in-depth analysis of qualitative data from interviews, the authors explored challenges and opportunities in the provision of long-term care domestic services from wide-ranging perspectives and experiences of key stakeholders, including domestic helpers, their employers (older adults or their family members), domestic service company managers, and industry association staff. They identified multiple challenges concerning the domestic helper – older adult relationship, day-to-day care, training, the domestic service company’s role, and perhaps most importantly – workforce shortages and instability, owing to low wages, low social recognition, and pervasive social stigma associated with the work of domestic helpers. To overcome these challenges, the authors suggested potential opportunities to strengthen the domestic helper workforce through providing on-the-job training and pathways for career advancement, increasing access to social welfare and medical assistance, enhancing person-centered care for older adults as a core competency, and facilitating social networking and online peer support among domestic helpers.

In China, community-based long-term care services for older adults remain limited in urban areas and largely nonexistent in rural areas, despite increased policy attention on developing these services in recent years. Very little is known about these services where they do exist. Contributing to filling this gap, the study by Chen et al. (Citation2019) examined older clients’ service satisfaction and service recommendation for a community-based meal service program in Jing’an district in Shanghai, informed by Donabedian’s quality-of-care framework. They found that quality of food and caregivers’ attitudes were key to respondents’ service recommendation, whereas tidiness of tableware and interactions with caregivers were positively related to their service satisfaction. The authors note that community-based meal services are among the most popular and rapidly increasing services for older residents in Shanghai. Using concrete evidence obtained from this study, the authors recommend that policymakers consider older people’s opinions and experiences as well as their service preferences and unmet needs in making strategic allocation of resources to maximize the capacity of community-based elder care services.

Unmet needs across the care span: Healthcare, long-term care, and end of life care

Extending previous research, Cao et al. (Citation2022) used the CLHLS data from 2005–2014 to estimate the prevalence and risk factors of unmet needs among community-living older adults with disability (measured by activities of daily living (ADL) limitations) in China. The authors used a novel conceptual framework to guide the empirical measurement of under-met needs and completely unmet needs, to gain a more nuanced understanding of the otherwise broad categorization of unmet needs. Their estimates suggest that in 2014 more than 50% of community-living Chinese elders with disability experienced under-met needs, and nearly 5% of them reported completely unmet needs. The proportion with completely unmet needs doubled over the 10-year study period. The authors identified multiple risk factors of under-met needs such as lower household income, more ADL limitations, living alone, and fewer living children, and risk factors of completely unmet needs including fewer ADL limitations and living alone. They called particular attention to the finding that among the young old (those aged 65–74) with disability the proportion reporting completely unmet needs nearly quadrupled over the study period, cautioning that this situation may get worse as the parents of China’s one-child generation are approaching old age. These findings can inform policy efforts to address gaps in long-term care services for disabled older adults, particularly services provided in home and community-based settings.

Turning to a hardly ever treated topic in Chinese gerontological literature, Gong et al. (Citation2022) explored the end of life experience among older adults in China – specifically, quality of death in relation to medical expenses and timely medical treatment in the last year of life. The authors used the CLHLS data for this investigation. Their results suggest evidence that both higher medical expenses in the last year of life and lack of timely medical treatment before dying were associated with lower quality of death (based on proxy assessment by each decedent’s next of kin). In our view, this study helps to raise awareness of two important issues related to end of life care in China. The first pertains to the widespread cultural expectation and commitment of family caregivers to prolong the life of their terminally ill loved ones under all circumstances and at all costs, often contributing to futile care, exorbitant medical expenses, and poor quality of life before death. The second issue concerns Chinese evasive cultural attitudes toward discussion of death, which remains a taboo and major impediment to spreading the concept and practice of advance care planning. As pointed out by the authors, there is an urgent need for strengthening education on death and dying, developing hospice and palliative care services, as well as improving pain management and quality of end-of-life care for terminally ill patients.

In China, as elsewhere, older adults with low incomes and meager resources are among the most vulnerable members of society. Using survey data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, Zhang and Gao (Citation2021) examined whether welfare receipt was associated with changes in consumption patterns among families headed by older adults (either main respondent or spouse being 60 years or older). Welfare in this context referred to dī bǎo, or minimum livelihood guarantee, a means-tested cash transfer safety-net program in China (similar to Medicaid in the United States). The authors found that welfare receipt was associated with increased total health expenditures, including informal healthcare and self-treatment expenses, among rural (but not urban) older families. However, regardless of residence, welfare receipt did not boost expenditures on clinic and hospital visits among older families, nor did it have any significant effect on these families’ spending on basic necessities for daily survival (such as food and clothing) as might be expected. These findings suggest that although dī bǎo receipt is helpful, it is far from adequate, raising the issue of unmet needs for subsistence and health-related consumption among low-income older families in both urban and rural China.

Long-term care financing

To accelerate the development of long-term care services and address the lack of comprehensive financing for these services, China launched its long-term care insurance (LTCI) pilot programs in 15 cities in 2016, and subsequently expanded the pilots to 49 cities across the country in 2020. In a commentary by Feng et al. (Citation2023), the authors provide a timely overview of the initial 15 pilot programs in terms of similarities and differences in their target populations, sources of financing, beneficiary eligibility criteria, and benefit design. Drawing on limited information currently available from government sources and the literature, the authors offer insights on the strengths and limitations, implementation challenges, and future prospects of these ongoing pilots. They underscore the need for addressing several key policy issues and challenges before these programs may be scaled up for national implementation. Specifically, the authors called for solidifying the LTCI financing pool for independence and self-sustainability (rather than over-reliance on existing health insurance funds), balancing national priorities and local needs in LTCI design, reducing coverage gaps and disparities, ensuring quality of care through pay-for-performance and regulatory oversight, and using rigorous science and empirical evidence from independent evaluations to guide LTCI policy decisions during the pilot stage and beyond.

The common thread

This special issue was nearly four years in the making. We started planning for it in November 2019. Then, the COVID-19 outbreak and ensuing global public health emergency turned the entire world upside down. The pandemic has surely slowed down the manuscript process. As Guest Editors, we are glad to see this special issue in print now.

At the beginning of this endeavor, we had thought about organizing a collection of articles around the broad theme of long-term care in China. Eventually, we settled on a more specific theme—Advancing Long-term Care Policy and Research in China—as exhibited in the title of this special issue. This choice has been motivated by several considerations, as described below, which we believe make the theme quite fitting – not only content wise for the featured articles but also in China’s unique policymaking context.

Although the articles included in this special issue cover a wide range of topics, a common feature is that all of them used carefully collected and best available empirical data as well as rigorous and cutting-edge research methods to address an important policy relevant topic related to long-term care for older adults in China. On display is sophisticated quantitative analysis of secondary data from nationally representative surveys (Cao et al., Citation2022; Gong et al., Citation2022; J. Wang et al., Citation2020; Zhang & Gao, Citation2021) and localized ones (Chen et al., Citation2019), and qualitative in-depth analysis of primary data from interviews with study participants (He et al., Citation2021; J. Wang et al., Citation2022). Other authors took stock of existing data sources to facilitate research (Xu et al., Citation2021), and critically assessed major long-term care policy developments (Feng et al., Citation2023). The authors leveraged expertise in their respective subject matter areas to elucidate their study findings and implications, highlight unmet needs among their study populations, and call for policy actions or make policy recommendations and practical insights supported by evidence emerging from the studies. Collectively, these studies contribute to building and strengthening the evidence base much needed for sound policymaking in China.

At this juncture, we also feel the urge to draw on two notable examples of public policymaking in China – one contemporary and another historical but from the not-so-distant past – to illustrate the perils of ill-conceived policy actions that are just antithetical to the theme of this special issue. The first example has to do with China’s recent abrupt reversal (in December 2022) of its draconian zero-Covid policy that had been in effect for three years, causing rapid spread of the virus in the population, an unknown toll of excess deaths, and myriad other disastrous health and socioeconomic consequences (Buckley et al., Citation2022). Clearly, this policy flip-flop was politically driven and not informed by evidence and public health best practice. The second example concerns China’s one-child policy, which was rushed into effect in 1980, when in fact the total fertility rate had been on steady decline over the prior three decades even absent strict birth control policies (Wang et al., Citation2012). The rollout of the one-child policy was mostly a political decision, not informed by science and evidence (Wang et al., Citation2012), which has since distorted the population age structure and accelerated population aging in China. The one-child policy was rescinded in 2016, a course correction that experts believe should have already been made at least a decade earlier (Wang et al., Citation2016).

Conclusion

All that is said above serves as a reminder that for long China has had a thin tradition of “empiricism” in research, much less in policymaking. This situation has improved considerably over the past few decades resulting from increased exchanges between Chinese scholars and academic institutions and their counterparts in the global research community. As demonstrated in the studies featured in this special issue, the authors have made their share of contributions toward building research evidence where it is lacking and supporting evidence-based long-term care policymaking and practice to meet the mounting challenges of population aging in China.

Key points

China’s population is aging rapidly, and becoming more mobile than ever, driven by massive rural-to-urban migration.

Demographic and socioeconomic changes are weakening family-based elder care while escalating the needs for formal long-term care services for older adults in China.

China needs to build and use scientific evidence from rigorous research to inform long-term care policymaking and practice.

All studies included in this special issue use empirical data and robust research methods to address important policy relevant issues concerning long-term care in China.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Buckley, C., Stevenson, A., & Bradsher, K. (2022, December 19). From Zero Covid to No Plan: Behind China’s Pandemic U-Turn. NY Times (Print). Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/19/world/asia/china-zero-covid-xi-jinping.html

- Cao, Y., Feng, Z., Mor, V., & Du, P. (2022). Unmet needs and associated factors among community-living older people with disability in China: 2005–2014. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 648–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2022.2110806

- Chen, L., Ye, M., & Kahana, E. (2019). Process and structure: Service satisfaction and recommendation in a community-based elderly meal service in Shanghai. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 631–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2019.1704132

- Feng, Z., Glinskaya, E., Chen, H., Gong, S., Qiu, Y., Xu, J., & Yip, W. (2020). Long-term care system for older adults in China: Policy landscape, challenges, and future prospects. The Lancet, 396(10259), 1362–1372. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32136-X

- Feng, Z., Lin, Y., Wu, B., Zhuang, X., & Glinskaya, E. (2023). China’s ambitious policy experiment with social long-term care insurance: Promises, challenges, and prospects. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 705–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2023.2182574

- Gong, X., Pei, Y., Zhang, M., & Wu, B. (2022). Quality of death among older adults in China: The role of medical expenditure and timely medical treatment. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 667–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2022.2079907

- He, L., van Heugten, K., Perez, Y. P. M., & Zheng, Y. (2021). Issues of elder care among migrant workers in contemporary rural China: Filial piety redefined from a foucauldian perspective. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 554–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2021.1926203

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2021). Bulletin of the seventh national census (No. 7). Beijing: National Bureau of Statistics.

- Smil, V. (1999). China’s great famine: 40 years later. BMJ, 319(7225), 1619–1621. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1619

- State Council Information Office. (2023, January 17). Press conference on the operation of the national economy in 2022. Beijing: The State Council Information Office. Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2023-01/17/content_5737627.htm

- United Nations. (2018). World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision. The Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. Retrieved from https://population.un.org/wup/

- United Nations. (2022). World population prospects 2022, online edition. The Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. Retrieved from https://population.un.org/wpp/

- Wang, F., Cai, Y., & Gu, B. (2012). Population, policy, and politics: How will history judge China’s one-child policy? Population & Development Review, 38, 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00555.x

- Wang, F., Gu, B., & Cai, Y. (2016). The end of China’s one-child policy. Studies in Family Planning, 47(1), 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2016.00052.x

- Wang, J., Huang, Y., Zhang, Y., Wu, F., & Wu, B. (2022). Domestic helpers as frontline workers in home-based long-term care in China: opportunities and challenges. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 611–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2022.2120323

- Wang, J., Yang, Q., & Wu, B. (2020). Effects of care arrangement on the age of institutionalization among community-dwelling Chinese older adults. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 595–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2020.1726720

- Wu, B., Cohen, M. A., Cong, Z., Kim, K., & Peng, C. (2021). Improving care for older adults in China: Development of long-term care policy and system. Research on Aging, 43(3–4), 123–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027521990829

- Xu, H., Pei, Y., Dupre, M. E., & Wu, B. (2021). Existing datasets to study the impact of internal migration on caregiving arrangements among older adults in China. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2021.1926866

- Zhang, Y., & Gao, Q. (2021). Does welfare receipt change consumption on health among older families? The case of China. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 683–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2021.1926207