ABSTRACT

Since the Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987, regular oversight of United States nursing home activities has been a key strategy to ensure minimum levels of care quality for residents. Oversight activities have included “standard” survey visits – that is, annual unannounced visits by state survey agencies (SSAs) that directly observe resident care and interview nursing home residents and staff. This study provides an overview of these activities, focusing on oversight delays arising from policy changes brought on by the pandemic. Data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service’s (CMS) Quality, Certification and Oversight Reports, Survey Summary Files, and Provider Information Files were used to measure delays in survey completion across SSAs. Study findings reveal delays in inspection activities, which have resulted in a large backlog of uncompleted standard surveys far exceeding regulatory requirements. These delays exist across nursing homes with high and low levels of quality. As SSAs work through the backlog of surveys, they may prioritize the completion of surveys based on prior performance. This precedent may be expanded as CMS explores opportunities to produce processes that target the completion of surveys in the poorest performing nursing homes.

Introduction

For decades, regulation has played a key role in the United States’ nursing home sector (Wiener et al., Citation2007). Regulatory activities, primarily conducted at the state level by state survey agencies (SSAs), have included regular standard visits and timely responses to complaints (Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of Citation1987). During these visits, surveyors may find deficient practices, which can result in various enforcement options for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and states, including monetary penalties and exclusion from the Medicare and Medicaid programs (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], Citation2023b). There have long been challenges in these processes; however, the coronavirus-19 (COVID-19) pandemic posed substantial disruption (Stevenson & Cheng, Citation2021). CMS took steps to temporarily limit oversight activities due to uncertainty and concerns about controlling the spread of infection (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], Citation2020b). These steps are mirrored outside of the United States as well, as national regulatory bodies struggled to balance continued oversight while keeping residents and staff safe from infection (Comas-Herrera et al., Citation2022). As the pandemic progressed, nursing home oversight activities in the United States followed evolving guidance from CMS (Stevenson & Cheng, Citation2021).

In March 2020, CMS directed SSAs to limit survey activities to include only targeted infection control surveys, complaint surveys, and facility-reported incident (FRI) surveys triaged at the “immediate jeopardy” level (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], Citation2020b). This limited surveys to complaints and FRIs where the provider “has caused or is likely to cause serious injury, harm, impairment, or death to a resident” (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], Citation2020b). The directive suspended the standard surveys that nursing homes were required to receive every 9–15 months while CMS grappled with how to limit infections from entering nursing homes (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], Citation2020b). In August 2020, a new CMS directive expanded the degree of oversight to include a larger number of complaints and FRIs, in addition to the most pressing standard surveys. Further guidance directed states to conduct focused infection control surveys in all Medicare- and Medicaid-certified nursing homes before July 31, 2020 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], Citation2020a). CMS noted the potential risks of in-person surveys, directing SSAs to conduct on-site surveys after they had appropriate staffing and personal protective equipment (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], Citation2020a).

Researchers warned of the negative consequences that delayed surveys during COVID-19 would have in assuring minimal levels of quality (Stevenson & Bonner, Citation2020). Only a few months prior to the pandemic’s onset, the U.S. Senate held hearings detailing the need for increased oversight activities to prevent poor quality (United States Senate Committee on Finance, Citation2019). Additionally, for years, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has pointed to deficiencies in state regulatory processes, including a need to better monitor the nation’s poorest performing nursing homes (GAO, Citation2003, Citation2008, Citation2009a, Citation2019). Motivating these concerns, research has found that regulatory oversight generally leads to higher quality care (Mukamel et al., Citation2014, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Citation2022). For example, Li et al. (Citation2010) found that states with stronger regulatory enforcement standards saw more poorly performing nursing homes exit the market. Bowblis and Lucas (Citation2012) find positive relationships between regulation and some dimensions of care. Another paper finds that state regulatory standards increased nursing home staffing levels – a measure strongly related to nursing home care quality – more than increased Medicaid reimbursement (Harrington et al., Citation2007). Additionally, since the passage of the Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987, researchers have found that nursing home quality generally has increased (Fashaw et al., Citation2020; Hawes et al., Citation1997; Zhang & Grabowski, Citation2004).

Less research has examined the effects of COVID-19 on the nursing home regulatory process. Stevenson and Cheng (Citation2021) noted large declines in enforcement activity following the beginning of the public health emergency. Interviews of the family caregivers of nursing home residents during the pandemic noted concerns about the lack of oversight leading to poor staffing and infections (Nash et al., Citation2021). The tension between halting inspections to protect residents from infection and harming residents through reduced oversight in poorly performing nursing homes is seen through the evolving regulatory guidance from CMS ().

Table 1. Timelines of nursing home oversight measures throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Guidance for state survey agencies to resume regular oversight activities

On November 12, 2021, CMS sent a memo to SSAs that provided guidance on the resumption of standard surveys, added flexibility for addressing complaints, and revised COVID-19-focused infection control survey procedures (CMS, Citation2021). The memo cited the temporary suspension of survey activities in 2020 and the prioritization of focused infection control surveys as the reasons for the backlog of standard and complaint surveys. Due to the backlog, CMS waived requirements for SSAs to make up for standard surveys not conducted due to the pandemic. Additionally, CMS directed SSAs to prioritize completing standard surveys based on a history of noncompliance in key areas such as abuse, infection control, violation of discharge requirements, and insufficient staffing (CMS, Citation2021). A detailed listing of CMS directives related to inspections during the public health emergency (PHE) can be found in .

This regulatory backdrop is in the context of a nursing home sector that shouldered a disproportionate share of U.S. COVID-19 mortality, accounting for 21% of U.S. coronavirus deaths through August 2021 (Cronin & Evans, Citation2022). As risk and surveyor capacity has evolved, CMS has taken steps to get oversight activities back on track, giving states discretion for addressing a backlog of inspections interrupted by COVID-19 (CMS, Citation2021). This paper reviews trends in regulatory oversight during and after the COVID-19 PHE by examining nursing home inspection activities and CMS’ guidance to SSAs. We focus on delays in conducting recertification surveys. Although complaint surveys are an essential oversight component, recertification surveys were the only inspection activity completely suspended during the COVID-19 PHE. Additionally, as SSAs worked through the backlog of recertification surveys, CMS waived SSA requirements to complete missed recertification surveys (CMS, Citation2021). Finally, recertification surveys are distinct among SSA inspection activities as they are conducted on an established timeline (every 9–15 months) to ensure consistent monitoring across all facilities (e.g., as opposed to ad hoc complaint investigations). Thus, delays in recertification surveys represent missed opportunities for identifying and correcting many quality challenges.

Methods

Data

CMS maintains the Quality, Certification and Oversight Reports (QCOR) website and provides data from its CASPER system. These data are updated weekly, providing month-to-month information on enforcement actions, survey counts, and other provider information for nursing homes. We used QCOR data extracted on January 5, 2024 (S&C Quality Certification and Oversight Reports, Citationn.d.).

We acquired data to describe intervals between nursing home standard surveys from CMS’ Nursing Home Survey Summary data files (CMS, Citationn.d.-a). These data provided a listing of recent nursing home inspections, including information on the location of each nursing home, dates of inspection, and numbers of deficiencies cited. Additional information on nursing home providers came from the CMS Nursing Home Provider Information files (CMS, Citationn.d.-b). These files identify whether a nursing home is a special focus facility (SFF), SFF Candidate, the nursing home’s star rating, as well as other measures of quality.

We also collected CMS directives to SSAs on nursing home regulation, highlighting the evolution of regulatory strategy throughout the pandemic.

Measures and analysis

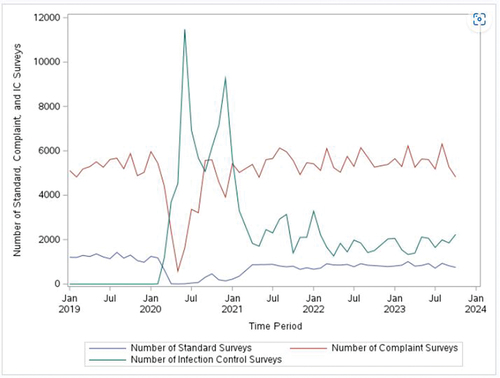

We used survey completion information from QCOR to describe survey activities in nursing homes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We have presented monthly standard, complaint, and infection control survey counts between January 2019 and October 2023 ().

Figure 1. Number of surveys throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

We used CMS’ survey summary data to estimate the average number of months that had elapsed between the two most recent standard surveys, comparing this time between surveys to CMS requirements. Current CMS requirements stipulate that nursing homes must receive a standard survey no later than 15 months after their previous standard survey (CMS, Citation2023b). CMS also requires that SSAs maintain an average interval of 12 months between standard surveys within their state (CMS, Citation2023b).

We collected information on CMS directives to SSAs in regulating nursing homes and used publicly available CMS data on inspections to provide an overview of how oversight activities evolved throughout the pandemic. As CMS has given minor discretion to states on how to perform oversight activities, we also explore whether this has resulted in SSAs prioritizing the completion of inspections in nursing homes with a history of poor performance (CMS, Citation2021). To assess how SSAs have prioritized resources, we calculated the average number of months between the two most recent standard surveys by nursing home provider rating and history of prior noncompliance. To compare SSA survey frequency by nursing home provider rating and history of noncompliance we categorized nursing homes as non-SFFs, SFFs, SFF Candidates, 1-star facilities, 5-star facilities, and nursing homes with a recent record of IJ deficiency (CMS, Citation2024a). These facilities represent some of the poorest (in the case of SFFs, SFF Candidates, and 1-star facilities) and highest (in the case of 5-star facilities) performing nursing homes. All analyses were conducted in SAS Enterprise Guide version 8.3 (SAS Institute, Inc).

Results

Overview of inspection activities throughout the pandemic

Oversight of nursing homes varied during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a sharp drop-off in complaint and standard surveys in March 2020 following CMS guidance suspending routine surveys (CMS, Citation2020b). Infection control surveys increased substantially when standard surveys ceased. Since the resumption of standard surveys, infection control surveys have dropped and remain at modest levels ().

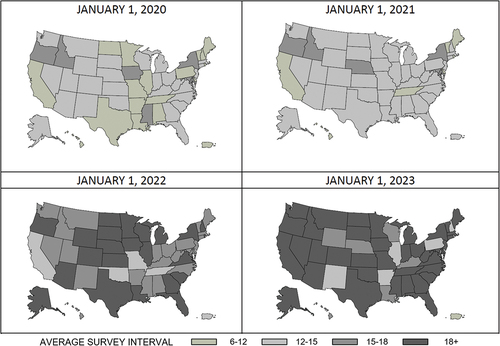

presents the average interval in months between the two most recent standard surveys across all 50 US states, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico at the beginning of each year, 2020–2023. Results show that as the pandemic progressed, the average interval between the two most recent standard surveys lengthened across the nation. In January 2020, before COVID-19 had spread throughout much of the United States, 17 states and Puerto Rico completed standard nursing home surveys an average of 6–12 months after the facilities’ previous standard survey. By January 2023, most states average standard survey interval exceeded 18 months or more.

Figure 2. Average standard survey interval (in months) throughout the COVID-19 pandemic across states.

Average survey interval as state survey agencies resume regular oversight activities

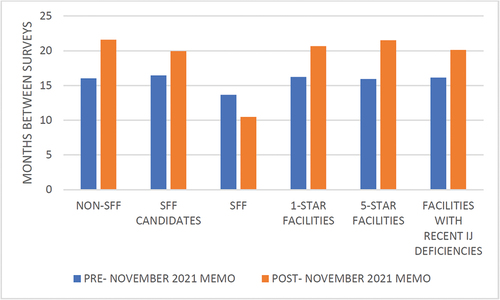

In November 2021, CMS directed SSAs to resume standard survey activities () (CMS, Citation2021). This directive waived the requirement for SSAs to make up standard surveys not conducted due to the pandemic. SSAs were directed to prioritize standard surveys based on a history of noncompliance. shows the average survey interval at the time of the CMS directive in November 2021 and two years later in November 2023. The average survey interval for SFFs declined from over 13.5 months to less than 10.5 months, still above the required interval of 6 months between standard surveys for SFFs. For non-SFF nursing homes, SFF candidates, 1-star facilities, 5-star facilities, and nursing homes with recent immediate jeopardy deficiencies, the average survey interval increased in the two years following the November 2021 directive. The number of months between the two most recent standard surveys increased from 16 months to over 20 months for facilities with recent immediate jeopardy deficiencies. One-star and 5-star facilities saw an interval increase from 16.2 to 20.7 months and 15.9 to 21.5 months, respectively.

Figure 3. Average interval between the two most recent standard surveys (in months) by provider type.

Discussion

Prioritizing nursing homes with a history of noncompliance

The average survey interval for the 88 nursing homes in the SFF program fell to approximately 10 months following the November 2021 directive to prioritize facilities with a history of noncompliance (). Despite these improvements, SSAs have still been unable to complete inspections of SFFs every six months as required by the program. Additionally, the lag in inspections has increased among other facilities with records of noncompliance. For example, shows an increase in the average survey interval for facilities at risk of being placed into the SFF program (i.e., SFF Candidates) following the November 2021 directive. These survey lags are similar across 1-star, 5-star, non-SFF, and nursing homes with a history of immediate jeopardy deficiencies, despite the ability for SSA’s to prioritize poorly performing nursing homes.

Delays in survey completion were a long-standing problem before the pandemic (GAO, Citation2019; Government Accountability Office [GAO], Citation2009b) but have increased to even higher levels despite CMS granting states more flexibility (Office of Inspector General [OIG], Citation2022). These delays severely impede SFF program goals to increase scrutiny of the poorest performing nursing homes (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Citation2022). Additionally, it should be noted that CMS directives throughout the pandemic did not distinguish between SFF, non-SFF, or other nursing homes when scaling back oversight ().

Widening recertification gaps

Between 2020 and 2023, the average survey interval has increased dramatically across states. We find at the beginning of 2023 that in most states, the average gap between nursing home surveys exceeded one and a half years. As these gaps widened, the proportion of oversight activities focused on complaint and infection control surveys grew (). Delays in recertification surveys could pose challenges to ensuring care quality, especially for vulnerable resident populations. Infection control surveys are limited in scope, and complaint surveys depend on residents and families actively filing grievances about their care. Due to reporting and other barriers, addressing care quality issues for cognitively impaired individuals through the complaints process may be especially challenging. For instance, research has shown that facilities with higher proportions of residents with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias have lower levels of substantiated complaints (Bhattacharyya, Peterson, Molinari, Fauth, et al., Citation2024). In addition, complaint investigations have faced similar limitations and delays as standard surveys. For example, among complaint surveys prior to the pandemic, delays have been found to impact the investigation process (Bhattacharyya, Peterson, Molinari, & Bowblis, Citation2024). Recertification surveys also focus more comprehensively on care provided in a facility, looking beyond what is reported as a complaint to the SSA. On a recertification survey, inspectors have broader purview to interview patients and workers across the facility, regardless of residents’ propensity or ability to lodge complaints with the SSA.

Surveyor staffing challenges

Despite CMS directives to resume regular standard survey activities, a large backlog in inspection completion remains. We find that this backlog varies across states, with five states and Puerto Rico completing surveys in an average interval of fewer than 15 months (). All other states exceed 15 months, with a majority exceeding an average interval of 18 months between their two most recent recertification surveys per nursing home. These delays are influenced by the regulatory changes noted in , but other factors may also contribute. For example, a recent Senate report noted staffing shortages, high turnover, and an inexperienced workforce as barriers to conducting inspections on time (United States Senate Special Committee on Aging, Citation2023). The Senate report found that SSAs frequently cite an inability to provide competitive salaries as a barrier to adequate surveyor staffing. Additionally, the Senate report claimed that newer surveyors increase the time to complete survey activities (United States Senate Special Committee on Aging, Citation2023).

State discretion in prioritizing resumption of survey activities

Historically, a key challenge in nursing home survey efforts has been their variability across states. Even in the context of uniform federal standards, prior research has found wide variation across SSAs in the level and severity of deficiencies cited (Kelly et al., Citation2008; Peterson et al., Citation2021). This variation has spurred calls for greater standardization in inspection processes (OIG, Citation2003) and sparked CMS efforts to achieve greater uniformity in state performance (CMS, Citation2022). In contrast, CMS regulatory directives from March 2020 and November 2021 () gave states greater discretion as they resumed regular inspection activities. After initially curtailing SSAs’ ability to conduct standard surveys, the November 2021 CMS memo gave states discretion to prioritize standard surveys based on history of noncompliance, presenting an opportunity for SSAs to target the worst performing facilities.

Distinct from the challenge of variable state performance on oversight responsibilities, regulatory theorists have championed the practice of responsive regulation, an approach that adapts regulations to the behavior of organizations (Walshe, Citation2001). Such an approach gives regulators the ability to target their oversight efforts to providers in greatest need of scrutiny and where residents are at greatest risk of harm. The SFF program and the recent PHE-related change notwithstanding, states have typically had little discretion in targeting oversight toward the poorest performing nursing homes.

In April 2024, CMS announced a pilot initiative that will explore a more responsive approach to regulation (CMS, Citation2024b). Although many implementation details are to be determined, the initiative aims to develop a risk-based survey approach. In contrast to the current one-size-fits all approach, the risk-based survey allows consistently higher-quality facilities to receive a more focused survey “that takes less time and resources than the traditional standard recertification survey, while ensuring compliance with health and safety standards” (CMS, Citation2024b). CMS has begun to notify states of their participation and will make more implementation details available as they do.

The new CMS initiative is consistent with the broad recommendation of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) Committee on Nursing Home Quality of Care to design a more effective and responsive system of quality assurance (NASEM, Citation2022). In fact, among its oversight recommendations, the Committee recommended that CMS develop and evaluate reforms such as targeted oversight activities for high performing facilities, provided adequate safeguards were in place (e.g., having surveyors onsite at least annually, states meet minimum standards for complaint investigations, and facilities meet real-time quality metrics such as staffing hours). The Moving Forward Coalition – a committee aimed at improving nursing home care through the implementation of recommendations in the NASEM report – focused further on this recommendation, developing an action plan for SSAs to implement a two-day targeted standard survey (Moving Forward Coalition: Nursing Home Quality Coalition, Citation2023). Although it is unclear whether CMS will take a similar approach in their work, the Moving Forward materials outline criteria for selecting high performing facilities and identify core parts of the survey on which inspectors could focus on in an abbreviated survey. Some advocacy groups have expressed concern about a targeted approach to recertification surveys, especially around differentiating “higher quality” and “lower quality” facilities (Center for Medicare Advocacy, Citation2024). Given concerns about nursing home quality of care (e.g., facility quality of care can decline quickly) and about state oversight efforts (e.g., SSAs often have not been responsive to residents’ concerns), some skepticism of a targeted survey approach is warranted. However, with adequate safeguards and sufficient monitoring in place, it is important to explore strategies to improve the effectiveness of oversight in light of the major deficiencies that have been identified previously.

Strategies to improve inspection timeliness

In the recent U.S. Senate report on nursing home surveyor staffing shortages, the Aging Committee’s majority staff recommended increasing inspection funding streams to states to improve the surveyor workforce (United States Senate Special Committee on Aging, Citation2023). The U.S President’s budget for Fiscal Year 2025 also includes proposals to shore up funding for these activities (Office of Management and Budget, Citation2024). Alongside these funding recommendations, CMS continues to pursue a risk-based survey strategy, which would allow inspectors to conduct more focused and less timely surveys of higher performing facilities. CMS describes their testing of this strategy as targeting higher quality facilities by potential measures such as “a history of fewer citations for noncompliance, higher staffing, fewer hospitalizations, and other characteristics (e.g., no citations related to resident harm or abuse, no pending investigations for residents at immediate jeopardy for serious harm, compliance with staffing and data submission requirements)” (CMS, Citation2024b). CMS suggests that potentially no more than 10% of nursing homes would receive a risk-based survey (CMS, Citation2024b). While this proposal would free up limited SSA resources to spend more time on poorly performing facilities, the identification of nursing homes to receive the risk-based survey remains to be seen. Nonetheless, in the absence of sustained increased funding for inspection activities, risk-based survey approaches may be necessary.

Limitations

Survey activities do not account for the entirety of the work that SSAs engage in with nursing homes. For example, SSAs may consult with nursing homes on care practices or deliver personal protective equipment to nursing homes. This work would not be included in the oversight activities captured in our study. Additionally, we do not include information on the amount of time that inspectors spent in nursing homes throughout the pandemic.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic presented an unprecedented challenge to regulators. The tension between ensuring resident safety through limiting in-person contact with outside parties coupled with the need for in-person inspections is seen in the evolving guidance. Regular oversight activities were supplanted by special focused infection control surveys, which remain a fixture of state survey activities. We give an overview of these inspection activities throughout the pandemic and shed light on the large delays in standard survey completion across the country. As states resume usual survey activities, policymakers must ensure that regular standard surveys are completed in a timely manner.

Key Points

The coronavirus disease 2019 dramatically shifted how regulators approached nursing home oversight in the United States.

Due to the pandemic’s effect on the regulatory environment, a large backlog of uncompleted surveys has accumulated.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has given states minor flexibility in responding to the backlog.

State flexibility presents an opportunity for more targeted enforcement activities.

Targeted enforcement may allow better monitoring of the poorest performing nursing homes.

Supplementary Materials.docx

Download MS Word (14.3 KB)Disclosure statement

David G. Stevenson’s time was supported in part by the Veterans Affairs Tennessee Valley Healthcare System. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Data availability statement

Data are publicly available at data.cms.gov and qcor.cms.gov. This study was not preregistered.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2024.2384335

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bhattacharyya, K. K., Peterson, L., Molinari, V., & Bowblis, J. R. (2024). Consumer complaints in nursing homes: Analyzing substantiated single-allegation complaints to deficiency citations. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 36(1), 174–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2023.2297599

- Bhattacharyya, K. K., Peterson, L., Molinari, V., Fauth, E. B., & Andel, R. (2024). The importance of zero-deficiency complaints in nursing homes: A mere consequence or serious concern? Journal of Applied Gerontology, 43(7), 945–955. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648241229548

- Bowblis, J. R., & Lucas, J. A. (2012). The impact of state regulations on nursing home care practices. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 42(1), 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-012-9183-6

- Center for Medicare Advocacy. (2024). CMS must preserve standard surveys for all nursing facilities. https://medicareadvocacy.org/cms-must-preserve-standard-surveys-for-all-nursing-facilities/

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2021). Changes to COVID-19 survey activities and increased oversight in nursing homes Author. QSO-22-02-ALL. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/qso-22-02-all.pdf

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2022). Revised long-term care Surveyor guidance: Revisions to Surveyor guidance for phases 2 & 3, arbitration agreement requirements, investigating complaints & facility reported incidents, and the psychosocial outcome severity Guide. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/qso-22-19-nh-revised-long-term-care-surveyor-guidance.pdf

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2023a). [ dataset]. Special focus facility (SFF) program. Retrieved December 28, 2023, from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/downloads/SFFList.pdf

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2023b). State operations manual: Chapter 7 – survey and enforcement process for skilled nursing facilities and nursing facilities. https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/guidance/manuals/downloads/som107c07pdf.pdf

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2024a). Five-Star quality rating system. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/health-safety-standards/certification-compliance/five-star-quality-rating-system

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2024b). Nursing homes: Medicare and medicaid Programs; reform of requirements for long-term care facilities. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/guidanceforlawsandregulations/nursing-homes

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (n.D.-a). Survey Summary. Retrieved December 28, 2023a from https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/dataset/tbry-pc2d

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (n.D.-b). Provider information. Retrieved December 28, 2023b from https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/dataset/4pq5-n9py

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (n.D.-c). Health deficiencies. Retrieved December 28, 2023c, from https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/dataset/r5ix-sfxw

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2020a). Enforcement cases held during the prioritization period and revised survey prioritization. (QSO-20–35–ALL). https://www.cms.gov/files/document/qso-20-35-all.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2020b). Prioritization of survey activities 2020. QSO-20–20–All. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/qso-20-20-allpdf.pdf-0

- Comas-Herrera, A., Marczak, J., Byrd, W., & Lorenz-Dant, K. (2022). LTCcovid international living report on COVID-19 and long-Term Care. LTCCovid and care policy and evaluation centre. London School of Economics.

- Cronin, C. J., & Evans, W. N. (2022). Nursing home quality, COVID-19 deaths, and excess mortality. Journal of Health Economics, 82(102592), 102592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2022.102592

- Fashaw, S. A., Thomas, K. S., McCreedy, E., & Mor, V. (2020). Thirty-year trends in nursing home composition and quality since the passage of the omnibus reconciliation act. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(2), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.07.004

- Government Accountability Office. (2003). Nursing home quality: Prevalence of serious problems, while declining, reinforces importance of enhanced oversight. (GAO-03–561). https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-03-561

- Government Accountability Office. (2008). Federal monitoring surveys demonstrate continued understatement of serious care problems and CMS oversight weakness (pp. GAO-08–517). https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-08-517

- Government Accountability Office. (2009a). Cms’s special focus facility methodology should better target the most poorly performing homes, which tended to be Chain affiliated and for-profit. (GAO-09–689). https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-09-689

- Government Accountability Office. (2009b). Nursing homes: Addressing the factors underlying understatement of serious care problems requires sustained CMS and state commitment. (GAO-10–70). https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-10-70

- Government Accountability Office. (2019). Nursing homes: Improved oversight needed to better protect residents from abuse. GAO-19–433. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-19-433

- Harrington, C., Swan, J. H., & Carrillo, H. (2007). Nurse staffing levels and Medicaid reimbursement rates in nursing facilities. Health Services Research, 42(3p1), 1105–1129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00641.x

- Hawes, C., Mor, V., Phillips, C. D., Fries, B. E., Morris, J. N., Steele‐Friedlob, E., Greene, A. M., & Nennstiel, M. (1997). The OBRA‐87 nursing home regulations and implementation of the resident assessment instrument: Effects on process quality. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 45(8), 977–985. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02970.x

- H.R.3545 - 100th congress (1987-1988): Omnibus budget reconciliation act of 1987. (1987, December 22). https://www.congress.gov/bill/100th-congress/house-bill/3545

- Kelly, C. M., Liebig, P. S., & Edwards, L. J. (2008). Nursing home deficiencies: An exploratory study of interstate variations in regulatory activity. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 20(4), 398–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420802131817

- Li, Y., Harrington, C., Spector, W. D., & Mukamel, D. B. (2010). State regulatory enforcement and nursing home termination from the medicare and medicaid programs. Health Services Research, 45(6p1), 1796–1814. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01164.x

- Moving Forward Coalition: Nursing Home Quality Coalition. (2023). Designing a targeted nursing Home recertification survey. Moving Forward Coalition. https://movingforwardcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Designing-a-Targeted-Nursing-Home-Recertification-Survey.pdf

- Mukamel, D. B., Haeder, S. F., & Weimer, D. L. (2014). Top-down and bottom-up approaches to health care quality: The impacts of regulation and report cards. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 477–497. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-082313-115826

- Nash, W. A., Harris, L. M., Heller, K. E., & Mitchell, B. D. (2021). “We are saving their bodies and destroying their souls.”: Family caregivers’ experiences of formal care setting visitation restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 33(4–5), 398–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2021.1962164

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2022). The national imperative to improve nursing home quality. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26526

- Office of Inspector General. (2003). Nursing home deficiency trends and survey and certification process consistency. OEI-02-01-00600. https://oig.hhs.gov/documents/evaluation/2243/OEI-02-01-00600-Complete%20Report.pdf

- Office of Inspector General. (2022). CMS should take further action to address states with poor performance in conducting nursing home surveys. OEI-06-19-00460. https://oig.hhs.gov/documents/evaluation/3002/OEI-06-19-00460-Complete%20Report.pdf

- Office of Management and Budget. (2024). Budget of the U.S. Fiscal Year. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/budget_fy2025.pdf

- Peterson, L. J., Bowblis, J. R., Jester, D. J., & Hyer, K. (2021). U.S. State variation in frequency and prevalence of nursing home complaints. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(6), 582–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820946673

- S&C Quality Certification and Oversight Reports. (n.d.). Centers for medicare and medicaid services (CMS). Retrieved January 5, 2024, from https://qcor.cms.gov/main.jsp

- Stevenson, D. G., & Bonner, A. (2020). The importance of nursing home transparency and oversight, even in the midst of a pandemic. Health Affairs Blog. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20200511.431267

- Stevenson, D. G., & Cheng, A. K. (2021). Nursing home oversight during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(4), 850–860. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17047

- U.S. Senate Committee on Finance. (2019). Promoting elder justice: A call for reform. https://www.finance.senate. gov/hearings/promoting-elder-justice-a-call-for-reform

- U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging. (2023). Uninspected and neglected: Nursing home inspection agencies are severely understaffed, putting residents at risk. https://www.aging.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/UNINSPECTED%20&%20NEGLECTED%20-%20FINAL%20REPORT.pdf

- Walshe, K. (2001). Regulating U.S. nursing homes: Are we learning from experience? Health Affairs (Project Hope), 20(6), 128–144. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.128

- Wiener, J. M., Freiman, M. P., & Brown, D. (2007, December 1). Nursing home care quality: Twenty years after the omnibus Budget reconciliation Act of 1987. KFF. Retrieved January 5, 2024, from https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/7717.pdf

- Zhang, X., & Grabowski, D. C. (2004). Nursing home staffing and quality under the nursing home reform act. The Gerontologist, 44(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/44.1.13