Abstract

Studies of cross-cultural luxury values perceptions (LVPs) emphasize the consideration of different cultures. This study argues that certain LVPs in the West and China deviate from Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. This study investigates the perception of four values: high social status, high quality, uniqueness and modernity. Drawing on explicit and implicit epithets of Martin and White’s Appraisal framework, the textual characteristics of the four values in parallel corpora: English 17,268 words and Chinese 19,103 words are examined against Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Results caution against the generality of Hofstede’s finding and offer new insights into Chinese luxury marketing.

1. Introduction

The luxury industry has been one of the few industries that have been constantly growing in the past decades. According to Bain and Company (Citation2017), luxury goods have a great appeal in almost all countries of the world, with sales figures amounting to €1.2 trillion globally in 2017. In 2018, the total global luxury is worth €254 billion (McKinsey and Company Citation2018).

The China market has been a key contributor to the global luxury market for decades. The rapid economic development of China awakened people’s need for material possessions, which leads to the flourish of luxury goods consumption (Liao and Wang Citation2009). China has been the world’s second-largest luxury goods market since 2016 (Chi Citation2017) and is projected to be the world’s largest by 2025 (Bain and Company, and Tmall Luxury Division Citation2020). Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, a decrease in global travel has prompted a surge in domestic sales of luxury goods. In 2020, China recorded about 48% growth in domestic luxury sales totaling almost RMB 346 billion (Bain and Company, and Tmall Luxury Division Citation2020).

Since China is a key contributor to the global luxury market, it is important to study this ever-growing and ever-changing luxury market. Unsurprisingly, studies of perceptions of luxury values (LVPs) of the China market (e.g., Roy, Jain, and Matta Citation2018; Zhan and He Citation2012; Monkhouse, Barnes, and Stephan Citation2012; C. Lee Citation1991; Bond Citation1991; Wong and Ahuvia Citation1998; Li, Li, and Kambele Citation2012) or comparing between the China and Western marketsFootnote1 (e.g., Hung et al. Citation2011; Bian and Forsythe Citation2012; Kapferer Citation2014b; Yang et al. Citation2018) have been popular, as it can foster a better understanding of the China luxury market, and how it is different from (or similar to) Western luxury markets.

This study is unlike the current Chinese LPV studies. These studies often argue that Chinese consumers may favor one value while those of the West another. For example, when a range of values are discussed, Wong and Ahuvia (Citation1998) contend that Western consumers tend to associate luxury with the value of high-quality while Chinese consumers prefer the value of high social status. This kind of one-or-the-other evaluation, common in the current Chinese LPV studies, does not consider how the same set of values are perceived between Chinese and Western consumers, whether and how perceptions of the same values align or differ. More importantly, studies of cross-cultural LVPs that relate to the existing findings of Hofstede’s (Citation2001) cultural dimensions are limited.

In view of this current gap, the research questions of this study are as follows: first and foremost, what are some common luxury values shared among Chinese and Western consumers? Secondly, how are these same set of common luxury values perceived (the LVPs) by Chinese and Western consumers? Thirdly, do the LVPs of Chinese and Western consumers deviate from Hofstede’s (Citation2001) cultural dimensions, and if so, how? To answer these research questions, the study has the following four objectives: (1) identify the luxury values that are common in both Chinese and Western cultures; (2) identify the textual presentations of these luxury values in the chosen English and Chinese parallel data; (3) categorize these luxury values using the concepts of inscribed (explicit) and invoked (implicit) attitude in the Appraisal framework of Systemic Functional Linguistics (Martin and White, Citation2005); and (4) compare the categorized textual characteristics of the luxury values with characteristics of Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions: uncertainty avoidance (UAI), power distance (PDI), masculinity (MAS), long-term orientation (LTO) and Individualism (IDV).

This study is significant also because it examines actual marketing communication data. Traditional marketing research adopts the method of questionnaires and/or interviews on a selected sample of participants. While the findings inform the opinions of potential consumers, whether these findings are applied to actual marketing communication is doubtful. Although there are many studies on Chinese LVPs (as can be seen in the literature review in section 2), there are as many failed cases of adopting marketing contents to fit the China luxury market (Langer Citation2019; Prideaux Citation2019; Togoh Citation2019). This study takes a linguistic approach to examine actual marketing communication data (see section 4 for detail) to reveal how LVPs are communicated in the real world in China and Western countries. Marketing studies in a linguistic approach, though not new, are still scant. As pointed out by Kılıç and Yolbulan Okan (Citation2020), knowledge from disciplines other than marketing such as linguistics is required when reaching the target audience.

In brief, this study contributes both theoretically – investigating LVPs of the same set of values rather than “one-or-the-other” – and practically – revealing LVPs in actual marketing communication data. More importantly, this study argues that LVPs are not necessarily governed by characteristics of national culture, i.e., individualistic or collectivistic culture and its influence on LVPs.

The next section offers a review of literature in Chinese LVPs to identify the luxury values that are worthy of analysis in this study. It also includes an explanation of textual characteristics of the identified luxury values. The concepts of inscribed (explicit) and invoked (implicit) attitude in the Appraisal framework will be covered in section 3. Section 4 will detail how the explicit and implicit attitude of each luxury values are related to Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions. Hypotheses of Chinese and Western cultural characteristics of the four luxury values are established at the end of each subsection (4.1-4.5). Section 5 will present the corpora and the annotation procedure. Results and discussion follow in section 6. Significance and implications to marketing practitioners will be given in section 7 as a conclusion.

2. Literature review

2.1. Studies of Chinese LVPs – identification of luxury values

In the literature of Chinese LVPs, the value of social status in luxury products is one of the most discussed. The value of social status is often associated with the concept of face when Chinese LVPs are discussed. Face is a social identity (Goffman Citation1972) that one gains, though not exclusively, through outward appearance of rank and wealth (Bond Citation1991). The Chinese culture is seen as a culture with a strong inclination to build, maintain and improve face (Tai and Tam Citation1996; Prendergast and Wong Citation2003). To build, maintain and improve face, Chinese consumers are prone to spend money on luxury goods, especially those with ostentatious features for public display (Wallack and Montgomery Citation1992; Abe, Bagozzi, and Sadarangani Citation1996). Although many recent studies support this view of luxury consumption being conspicuous in China (e.g., Aliyev and Wagner Citation2018; Bian and Forsythe Citation2012; Monkhouse, Barnes, and Stephan Citation2012; Siu, Kwan, and Zeng Citation2016; Shukla Citation2012; Shukla Citation2010), other studies also show that as the China luxury market is getting more mature, the ‘nouveau riche’ attitude of new and inexperienced consumers will be progressively replaced by a more sophisticated and discrete style (Heine and Gutsatz Citation2017, 67 cited in Han, Nunes, and Drèze Citation2010), and Chinese consumers, especially young ones, yearn for more individualistic (Zhan and He Citation2012) and hedonic (Chen and Kim Citation2013) features of luxury goods.

Individualistic and hedonic features suggest two values that are common in luxury goods: the values of uniqueness and quality. Since China is often seen as a representative of collectivistic culture, in terms of LVPs, the value of uniqueness is usually shunned as societies of collectivistic culture value group identity highly and striying for individualism can mean a disruption of group harmony (Wang, Sun, and Song Citation2011; G. H. Hofstede Citation2001). Uniqueness is more valued in individualistic cultures and can offend people in collectivistic cultures (Jawaid and Siddiqui Citation2020). However, as mentioned earlier, Chinese consumers begin to value uniqueness, as shown in Zhan and He (Citation2012) study, the ubiquitous presence of best-known luxury brands and their monotonous styles start to tire or even repulse Chinese consumers. In a comparison of LVPs between Chinese and U.S. consumers, Bian and Forsythe (Citation2012) also find that Chinese consumers value uniqueness more than their U.S. counterparts.

Hedonism suggests indulgence. Quality is a hedonic value because having a product of good quality implies enjoyment. According to Wong and Ahuvia (Citation1998) and Monkhouse, Barnes, and Stephan (Citation2012), Chinese consumers value symbolic values, e.g., social status, over hedonic values, e.g., quality. On the other hand, people living in a collectivistic culture like the one in China value long-term benefits and are usually thrifty in their purchases (Hofstede Citation2001), especially when luxury goods are high-priced items, Chinese consumers would expect the quality to be exceptional.

Since the data of this study is luxury fashion texts, and as aforementioned, people of collectivistic cultures prefer long-term benefits while those of individualistic cultures, like people in the West, prefer short-term benefits, it is necessary to include the value of modernity. This can offer an understanding as to what dimensions of modernity do Chinese and Western consumers prefer and if there is a difference. Modernity can be considered in the dimension of a period, e.g., classic (from present to now and future) or a point in time, e.g., the latest, this season (Ho Citation2019).

In light of the above discussion, four luxury values should be considered in this study: Social-status, uniqueness, quality and modernity. The perceptions of these values in China and how they are compared to those in the West are, currently, not entirely clear. Some scholars contend that the collectivism in China affects greatly Chinese consumers’ LVPs: that they value highly how luxury goods can maintain and improve their social status, more so than the quality of the products, that uniqueness is usually seen in a negative light in China as it can challenge group harmony. Other scholars argue otherwise: that Chinese LVPs are more aligned with the Western ones as the China luxury market is maturing and changing. As for the value of modernity, its perceptions among Chinese and Western luxury consumers, and how much national culture plays into influencing these perceptions is unknown as it has not been studied before. Due to the lack of consensus in the current literature, or if the Chinese LVPs are changing, how and in which values specifically are lesser-known, this study takes these four luxury values as the point of departure to investigate how they are currently perceived and compared between Chinese and English.

2.2. Textual characteristics of the four luxury values

Now that the luxury values chosen for this study have been identified and since this study takes a linguistic approach using the method of textual analysis, it is necessary to explicate the textual characteristics of the four luxury values. In other words, what words or phrases in the text data should be considered as a case of one of the four luxury values. The textual characteristics of these four values are explicated in the following subsections to facilitate the annotation procedure (detailed in section 5).

2.2.1. High-social-status (HSS)

Status is defined as a position compared to others on certain dimensions that are considered important by society, such as wealth, physical attractiveness or other personal achievements like being successful in a career (Hyman Citation1942). Luxury consumption can make the consumer feel that their social status is enhanced (Dubois and Czellar Citation2002; Nelissen and Meijers Citation2011). To channel this value in products, luxury companies often employ the means of celebrity endorsement or making references to royals and aristocrats such as kings, queens, dukes and lords to create the feeling that consumers who own luxury products are of high social status (Fionda and Moore Citation2009; Atwal and Williams Citation2009; Kapferer and Bastien Citation2012; Kapferer Citation2014a). Textual presentations of the value of high social status can be identified as names of celebrities and epithets with references to celebrities and royals and their successful attributes, e.g., famous, noble.

2.2.2. High-quality (HQ)

Emphasizing the quality of products is crucial in building the image of luxury products (Bernard Dubois, Laurent, and Czellar Citation2001; Vigneron and Johnson Citation2004; Tynan, McKechnie, and Chhuon Citation2010; Turunen and Laaksonen Citation2011; Li, Li, and Kambele Citation2012). The value of high quality can also be communicated by highlighting the quality of the craftsmanship (Kapferer Citation1998; Vigneron and Johnson Citation2004). Because of this, textual presentations of the value of high quality can be identified in two ways: epithets with references to (1) the quality of products and (2) the quality of the craftsmanship.

2.2.3. Uniqueness (U)

Being unique or special is one of the prominent characteristics of luxury products because this quality differentiates luxury products from non-luxury products (Bernard Dubois, Laurent, and Czellar Citation2001; Vigneron and Johnson Citation2004; Calefato Citation2014; Kapferer Citation2017). Textual presentations of the value of uniqueness can be identified by epithets with references to uniqueness, e.g., unique, special, unlike any other.

2.2.4. Modernity (MD)

Fashion is modernity, it is about constant and successive change where the newest change always prevails, i.e., the most fashionable (Sullivan Citation2015; Polhemus Citation2011; Craik Citation2009; Nystrom Citation1928; Wilson Citation2003; Sapir Citation1931; Benjamin Citation2003; Hurlock Citation1929). Modernity can be understood in two ways: (1) a long duration, an object that is fashionable in the past, now and future, e.g., classic, timeless; and (2) the present, an object that is fashionable now and its fashionableness diminishes as time passes, e.g., on-trend, latest, this season. Textual presentations of the value of modernity can be identified and categorized in these two ways.

2.3. Explicit and implicit epithets in the Appraisal framework

After identifying the four common luxury values in Chinese and Western cultures, and also their textual characteristics, this section details how these textual characteristics can be categorized as implicit and explicit epithets in the Appraisal framework.

The Appraisal framework is a tool to identify attitude in language (Martin and White Citation2005). Attitude in language is identified in texts as evaluative epithets, which can be either explicit or implicit (inscribed or invoked as termed by Martin and White).

An explicit epithet is a clearly attitudinal word that marks the evaluation in an utterance. Its positive or negative sense is unambiguous in any context. Words like ‘good’ or ‘bad’, for example, are explicit epithets. By contrast, an implicit epithet can be any linguistic resources in texts that are considered attitudinal through the support of other factors that are intra-textual (e.g., metaphors, intra-textual references) or extra-textual (e.g., the reader’s knowledge, references outside the current text). Its positive or negative sense is ambiguous when taken out of context. For example, the word ‘ageing’ in texts about wine appreciation implies a positive meaning. When the target of evaluation is wine, ‘ageing’ refers to the wine’s potential vintage quality, something that indicates a higher economic value. However, in the cosmetics industry, when the target of evaluation is skin, ‘ageing’ suggests a negative connotation.

With the above definitions of explicit and implicit epithets, the explicit and implicit epithets of the aforementioned four luxury values can be summarized in the non-exhaustive .

3. Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions and hypotheses

This section will present Hofstede’s (Citation2001) five cultural dimensions, and explain how they are related to the explicit and implicit epithets of the four luxury values. Since this study focuses on the LVPs in Chinese and English marketing communication data, the Western markets in this study only refer to six English-speaking countries, namely United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Ireland (as mentioned in footnote 1). Therefore, only the weighted averaged indexes of the five cultural dimensions of these countries (i.e., national culture indexes) in Hofstede’s (Citation2020) research are included and compared with the national culture indexes of ChinaFootnote2. Hypotheses of Chinese and Western cultural characteristics of each luxury value will be established at the end of each subsection.

3.1. Uncertainty avoidance (UAI)

Uncertainty avoidance, simply, is about the attitude toward uncertainties (Hofstede Citation2001). The uncertainty avoidance index measures "the extent to which the members of a culture feeling threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations" (Hofstede and Hofstede Citation2005, 167). The index for China is 30, as compared to 45, the weighted average index of English-speaking countries. This means that the Chinese have a relatively higher acceptance of uncertainties. Hofstede even goes further that ‘the Chinese are comfortable with ambiguity; the Chinese language is full of ambiguous meanings that can be difficult for Western people to follow’ (Hofstede Citation2020). This can be understood that in expressing and understanding attitude in texts, Chinese can accept more implicit epithets. Because of this, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H1a: The Chinese corpus will have more implicit epithets.

H1b: The English corpus will have slightly more explicit epithets.

3.2. Power distance (PDI)

The index of power distance indicates "the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally" (Hofstede and Hofstede Citation2005, 46). China scores 80, one of the highest in the world. It translates that the Chinese in general accept inequality in the structure of society and respect the hierarchies. By contrast, the weighted average of the Western markets is 39, significantly lower than in China. This cultural dimension is related to the value of high-social-status, where the following hypotheses can be set:

H2a: The Chinese corpus will have more references to celebrities and royals (implicit epithets of HSS).

H2b: The English corpus will have fewer or no references to celebrities and royals.

3.3. Masculinity (MAS)

People in masculine cultures are competitive. They make purchases based on the symbols of success or achievement products can bring (Hofstede Citation2001). Indexes of both China and the weighted average for the Western markets are in the range of 60: the index of China is 66 and that of the Western markets is 62, which are moderately high scores as compared to other countries. Masculinity is related to the explicit epithets of the value of high social status. The relation can be understood as the hypothesis below:

H3: Both corpora will have a relatively high number of references to positive attributes of celebrities and royals (explicit epithets of HSS).

3.4. Long-term orientation (LTO)

Long-term orientation is the attitude of valuing future rewards. People in long-term-oriented cultures have the quality of being thrifty. People in short-term-oriented cultures, conversely, focus on the present and value instant gain and pleasure (Hofstede Citation2001). A large discrepancy is observed: 87 for China and 31 for the Western markets. This means that the Chinese are very pragmatic when it comes to spending and focus on long-term benefits, while English-speaking consumers in the Western markets enjoy what is on offer at the moment. This cultural dimension is related to two luxury values: modernity and high quality. Hypotheses related to modernity are formulated as below:

H4a: The Chinese corpus will have more epithets (explicit or implicit) with references to long-term styles.

H4b: The English corpus will have more epithets (explicit or implicit) with references to short-term styles.

As mentioned in 2.2, there are two ways to realize the value of high-quality: the quality of craftsmanship and products. The quality of craftsmanship is a long-term quality while the quality of products is more short-lived: a skill can be passed on while however good quality a product is, the lifespan is shorter than a skill. Hypotheses related to high quality can thus be formulated as below:

H4c: The Chinese corpus will have more epithets (explicit or implicit) with references to craftsmanship.

H4d: The English corpus will have more epithets (explicit or implicit) with references to products.

3.5. Individualism (IDV)

Individualism concerns the role of an individual as compared to the role of a group. Individual interests prevail group interests for members of cultures with high individualism. Individual characteristics, or uniqueness, are celebrated in these cultures. In comparison, members of cultures with low individualism, or with high collectivism, value harmony in groups. Standing out is not their priority (Hofstede Citation2001). China has an index of 20, one of the lowest in the world, while the Western markets have an average of 89. It is a sharp contrast: Chinese are highly collectivist and have a strong sense of group loyalty. Emphasizing individuality can be seen as a betrayal of group loyalty and harmony. On the other hand, consumers in the Western markets value highly individuality. This cultural dimension is related to the value of uniqueness. Hypotheses can be established as follow:

H5a: The Chinese corpus will have more implicit or no epithets of uniqueness.

H5b: The English corpus will have more explicit epithets of uniqueness.

4. Corpora design and annotation procedure

4.1. Corpora design

Two corpora of marketing texts were compiled from 240 parallel articles in English and Chinese, from the websites of three best-selling luxury brands: Chanel, Dior, and Louis Vuitton (Ma Citation2020, see Appendix for access of data). The English corpus has 17,268 words and the Chinese corpus has 19,103 words. Individual Chinese characters are segmented for a comparison based on the same units, i.e., words in the English language.

4.2. Annotation procedure

Manual annotation is adopted because there is no standard group of search words to identify epithets of luxury values. The following annotation procedure is adopted:

Determine whether a lexical item or phrase is a textual realization of one of the four luxury values.

Determine whether this textual realization is an explicit or implicit epithet.

Instances of explicit and implicit epithets of each luxury values are tallied.

Steps 1 and 2 are repeated between English and Chinese entries alternately – i.e., the English and the Chinese text data is coded simultaneously.

The reason for employing Step 4 is to enhance the reliability of the accumulated results. This step can reduce the likelihood of overlooking the relation between the categorization of the four luxury values and whether they are implicit and explicit epithets in one language or the other. This can eventually affect whether the results in one language confirm or reject the hypotheses. Without this step, errors such as highlighting epithets in one language as having a higher acceptance of power distance, uncertainties, etc. may happen more easily.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Uncertainty avoidance (UAI)

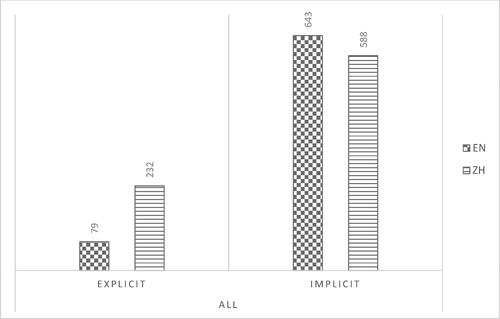

below illustrates the distribution between the overall number of explicit and implicit epithets in the English (EN) corpus and the Chinese (ZH) corpus. Both H1a and H1b (see 3.1) are rejected. The result shows that almost three times more explicit epithets are used to express the four luxury values in the Chinese corpus, and the English corpus has slightly more implicit epithets.

The most notable difference is the number of explicit epithets of the value of high-quality, where the Chinese corpus has 325% more explicit epithets (69 in Chinese versus 20 in English). The epithets become explicit in Chinese while the corresponding ones in English are implicit. For example, the word ‘savoir-faire’ is found in the English corpus, which is a French word meaning know-how. This word is commonly used in the discourse of luxury fashion. Know-how is the knowledge of the making of the product. This word is rather neutral when it is taken out of context. When it is in the context of luxury fashion, a positive attitudinal meaning is afforded, and consumers can associate it to the special knowledge required to make the products. Compare to savoir-faire (know-how), the corresponding words in Chinese are ‘精湛 工艺’ (skilled craftsmanship). 精湛 (skilled) is an unambiguously positive word, i.e., an explicit epithet. There are 19 instances of this shift from ‘savoir-faire’ to ‘精湛 工艺’ (skilled craftsmanship). This is a representative example of increasing explicit epithets by substitution.

Other than substitutions, the Chinese corpus also has many more explicit epithets by additions in the values of high social status, modernity and uniqueness. Respectively, the differences in the number of explicit epithets between the two corpora are 175% in the value of high-social-status (33 in Chinese versus 12 in English); 182% in the value of modernity (31 in Chinese versus 11 in English); and 131% in the value of uniqueness (83 in Chinese versus 36 in English).

In the value of high-social-status, a stronger focus on the positive attributes of celebrities and royals is found in the Chinese corpus: 知名/著名/大名鼎鼎 (famous), 大师 (master), 超模 (supermodel), 出色 表现 (outstanding performance), 高贵/尊贵 (prestigious), etc. These explicit epithets are added as compared to the English corpus. For example, the actress ‘Natalie Portman’ in English becomes 知名 女星 (famous actress) Natalie Portman; photographer Saskia Lawaks becomes 摄影大师 (photography master) Saskia Lawaks; and Kris Gottschalk becomes 超模 (supermodel) Kris Gottschalk. This stronger focus on the positive attributes of celebrities and royals will be further discussed in 5.3 – Masculinity.

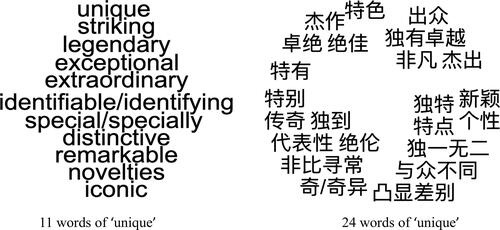

Similar to the value of high social status, for the values of modernity and uniqueness, a substantial number of additions of positive explicit epithets is found in the Chinese corpus. For example, the use of 时尚 (fashionable), 现代/摩登 (modern), 新潮 (trendy), 独有 (unique/only have), 独到 (unique/original), 独特 (unique/special), 独一无二 (unique/the only one).

The above results oppose Hofstede’s argument that the Chinese are comfortable with ambiguity (see 3.1). In luxury marketing communications, Chinese consumers have a lower tolerance in what it means by high social status, high quality, unique and modern. These values have to be made explicit for Chinese consumers to associate with the concept of luxury and be persuaded to make a purchase.

5.2. Power distance (PDI)

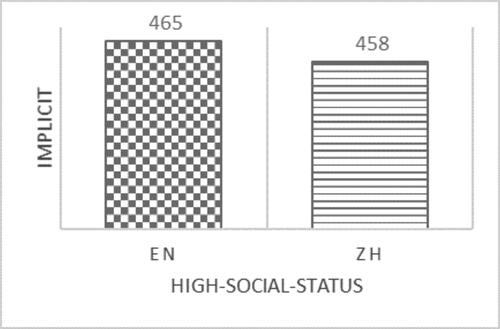

H2a and H2b (see 3.2) are rejected. In , the English corpus has more implicit epithets of HSS: slightly more references to celebrities and royals. The difference is minimal: only 2% more in the English corpus.

The relatively high number of references to celebrities and royals in the Chinese corpus conforms to the high PDI in China (see 3.2). The even higher number of references to celebrities and royals in the English corpus, however, challenges the notion that consumers in Western countries do not see the social status as important as consumers in China. One possible explanation of this result is that the target audience of luxury marketing texts is already the more powerful members of society. Consumers who can afford luxury fashion are privileged in wealth and possibly social status (middle-class or above). They can resonate with references to the higher levels of the hierarchy and thus have a higher acceptance of power distance. This suggests that Hofstede’s set of cultural dimensions is not a "one-for-all" solution in explaining local cultural characteristics. PDI, and UAI as shown above, or any other cultural dimensions for that matter, are field-specific: the degree of power distance, avoidance to uncertainties, etc. are subject to change depending on the products and the target audience being marketed.

The number of implicit epithets of HSS is the highest of the four values in both corpora. 72% of implicit epithets in the English corpus and 77% in the Chinese corpus are related to the value of HSS. These substantially high percentages in both corpora suggest the global prevalent use of celebrity endorsement as a marketing tool, which concurs with other findings in marketing studies (e.g., Agrawal and Kamakura Citation1995; Sridevi Citation2014; Lee and Um Citation2014; Fionda and Moore Citation2009; Atwal and Williams Citation2009; Kapferer and Bastien Citation2012; Kapferer Citation2014b). More importantly, as celebrity endorsement is identified as an implicit way of marketing communication (implicit epithets of HSS) in this study, the result shows that inconspicuous consumption is not only encouraged and accepted in the Western markets but also in China.

5.3. Masculinity (MAS)

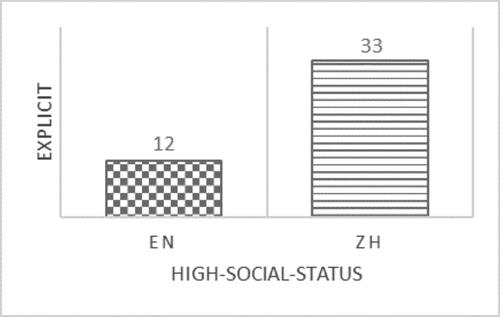

Masculinity is realized by explicit epithets of HSS: positive attributes of celebrities and royals, e.g., 知名 女星 (famous actress) Natalie Portman rather than just ‘Natalie Portman’, which is an implicit epithet of HSS. shows that the Chinese corpus has almost three times more explicit epithets of HSS. This confirms hypothesis H3 and also Hofstede’s (2005) findings that people in a masculine culture like the Chinese tend to focus on achievement and success. However, the English corpus has a relatively lower number of occurrences which does not correspond to the MAS index of 62 (see 3.3), which is a moderately high score in the world ranking (Hofstede Citation2020).

This finding can be interpreted in two ways: firstly, obvious and positive attributes may be added in the Chinese texts merely because Chinese consumers may not be as familiar to Western celebrities as English-speaking consumers. This kind of additions acts as a bridge for Chinese consumers to recognize a foreign name as someone successful. Chinese consumers can then acknowledge a superior social status that is associated with the products, projected by the foreign individual. Secondly, it is also possible that consumers in the Western markets prefer a higher level of inconspicuous consumption, that they focus on the style of the celebrities, the way they wear the garments and accessories of a certain brand, rather than relating to the success or achievement of the celebrities.

5.4. Long-term orientation (LTO)

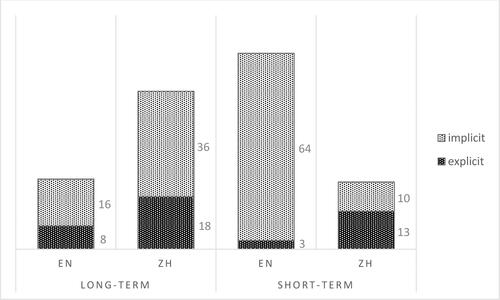

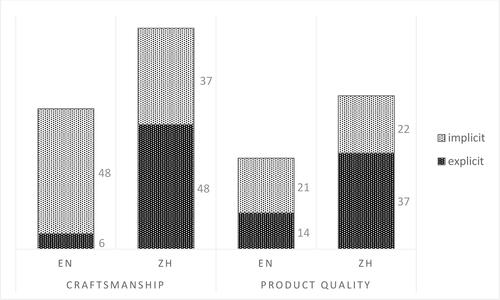

Long-term orientation is related to two values: modernity and high-quality. It is quantified by epithets of long-term (e.g., classic, forever) and short-term (e.g., fashionable, this season) styles; and epithets with references to the craftmanship (e.g., delicate, hand-made) or the product itself (e.g., premium, lasts indefinitely). confirms hypotheses H4a and H4b: the Chinese corpus has significantly more epithets with references to long-term styles and the English corpus has significantly more epithets, mostly implicit, with references to short-term styles. This finding coincides with Kwok and Uncles (Citation2005) that Chinese focus on long-term benefits when choosing luxury products. Chinese consumers are thrifty and prefer styles that last long.

As below shows, the Chinese corpus has more epithets with references to craftsmanship and products. While this confirms hypothesis H4c, it rejects H4d (see 3.4). However, since the number of epithets related to craftsmanship is still higher than those related to products in the Chinese corpus, given also the patterns of modernity epithets above, the results in the Chinese corpus coincide with Hofstede and Hofstede’s (Citation2005) point about the high-level of long-term orientation among Chinese. Interestingly, the English corpus also has more epithets related to craftsmanship than products. This is possibly because the craftsmanship is often highlighted to justify how luxury products are in marketing texts. By comparison, the orientation revealed by the results in the English corpus is shorter than that in the Chinese corpus.

5.5. Individualism (IDV)

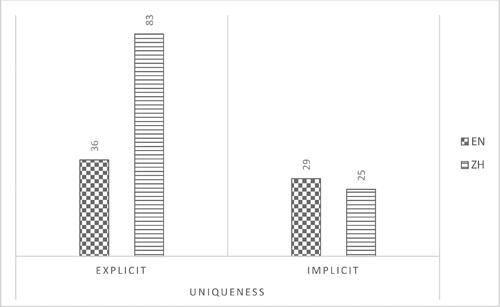

Individualism is related to the value of uniqueness. In below, the number of implicit epithets of uniqueness is similar in both corpora. However, the number of explicit epithets of uniqueness in the Chinese corpus is more than doubled. This completely overthrows hypotheses H5a and H5b (see 3.5). In the field of luxury fashion, or at least the data of this study shows, that individualism is foregrounded in the Chinese texts, and much more so than in the English texts.

Not only the expression of uniqueness is more explicit in the Chinese corpus, but it is also more diverse. The 83 Chinese occurrences include 24 different words that have the meaning of unique. In the English corpus, there are only 11 different words in the 36 occurrences (see below).

This pattern of uniqueness epithets in the Chinese corpus, being both more explicit and diverse, is the most surprising finding. It is a stark contrast when compared to the gap between the two IDV indexes in 3.5: 20 for China and 89 for the Western markets. This cultural and linguistic marketing study supports those of a user perspective: Zhou and Hui (Citation2003) find the increasing importance of self-directed symbolism among Chinese consumers, and Sun, D’Alessandro, and Johnson (Citation2016) argue the importance of the personal orientation toward luxury consumption in China.

below summarizes the above findings:

Table 2. Summary of findings.

6. Significance and implications to marketing practitioners

This study contributes to the field of marketing in several ways. First, the argument set in the title is justified: national culture characteristics do not always affect LVPs. This study proves that the role of national culture characteristics plays in LVPs is limited, thus challenges the applicability of Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions to the understanding LVPs. Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions can only act as general guidance but cannot be applied fully to understand how luxury values are perceived. The ways values are represented in cross-cultural marketing communications should be considered case-by-case. In this case, as Kapferer and Bastien (Citation2009) note, luxury marketing should be considered differently than the traditional kind of marketing.

This study also highlights the often-overlooked fact: even the same set of values are found in marketing texts, how these values are perceived and expressed vary greatly depending on the market. For example, as 5.4 shows, in the value of modernity, Chinese consumers perceive long-term styles more favorably while Western consumers prefer otherwise. This is an important finding, as mentioned in the literature review, research on the perception of modernity between Chinese and Western countries has not been conducted so far.

Chinese consumers are changing, and attention is required not only in what products can sell in China but also in how they are sold, i.e., their representation in marketing texts. Since the data under study is actual marketing communication data, the patterns summarized in can inform marketing communication practice. For example, this study confirms that in terms of LTO, textual characteristics still indicate that Chinese consumers prefer long-term benefits e.g., classic, timeless. However, the implications of this study are far more than merely confirming the findings of previous studies.

While the finding on the value of high social status aligns with many scholars (e.g., Aliyev and Wagner Citation2018; Bian and Forsythe Citation2012; Monkhouse, Barnes, and Stephan Citation2012; Siu, Kwan, and Zeng Citation2016; Shukla Citation2010; Shukla Citation2012) arguing that Chinese consumers purchase luxury good for the betterment of their social image, this study also finds that the emphasis on social status in the English texts is as or even slightly more prominent. On the other hand, this emphasis, regardless in English or Chinese, is implicit, which suggests that in luxury consumption, inconspicuousness in highlighting social status is preferred.

The finding on the value of uniqueness confirms scholars like Zhan and He (Citation2012) that Chinese consumers prefer uniqueness in their luxury products. Chinese consumers yearn for individualism in luxury consumption. More interestingly, the textual analysis of this study shows that this desire for uniqueness in China is way more pronounced and diverse than its Western counterpart. This kind of finding is made visible by the method of textual analysis and cannot be achieved by the method of questionnaire or interview.

Every study has its limitations. The reliability of the result can be improved if the data can be inter-coded. Since a second coder is not available, the data is coded alternately between the English corpus and the Chinese corpus to minimize discrepancies (see 4.2). To extend the argument about the applicability of Hofstede’s national cultural dimensions further, data of other sub-fields of luxury marketing: food and drink (e.g., wine), real estates, automobile, etc., can be included. Studies can also be conducted in languages other than English and Chinese, for example, marketing texts of European countries to broaden the definition of “the Western markets” in this study.

As set forth in the introduction, this study is significant because it contributes to the studies of Chinese LVPs theoretically – a different approach and findings different than traditional market research – and the Chinese marketing practice – how the four luxury values are perceived in China and how they differ to that of the Western markets. All findings in this study alert marketing practitioners to take local cultural characteristics with caution when considering luxury marketing.

Table 1. Explicit and implicit epithets of the four luxury values.

Disclosure statement

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and my ethical obligation as a researcher, I am reporting that I do not have any financial and/or business interests in or receive funding from any company that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 In studies of LVPs that compare the China and Western markets, if it is only one market, it is usually the U.S. (e.g., Bian and Forsythe Citation2012; Yang et al. Citation2018), otherwise “Western market or countries” are not specified (e.g., Hung et al. Citation2011; Kapferer Citation2014b). In this study, “Western markets or countries” refer to the six countries that have the highest population of English speakers: United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Ireland.

2 The indexes are taken from Hofstede (Citation2020). The weighted average indexes of the six countries in this study are calculated by multiplying each country’s index by its weight of population, then adding all the numbers and dividing it by the sum of all weights.

References

- Abe, S., R. P. Bagozzi, and P. Sadarangani. 1996. An investigation of construct validity and generalizability of the self-concepts: Self-consciousness in Japan and the United States. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 8 (3–4):97–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/J046v08n03_06.

- Agrawal, J., and W. Kamakura. 1995. The economic worth of celebrity endorsers: An event study analysis. Journal of Marketing 59 (3):56–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299505900305.

- Aliyev, F., and R. Wagner. 2018. Cultural influence on luxury value perceptions: Collectivist vs. individualist luxury perceptions. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 30 (3):158–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2017.1381872.

- Atwal, G., and A. Williams. 2009. Luxury brand marketing – The experience is everything!. Journal of Brand Management 16 (5–6):338–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2008.48.

- Bain and Company. 2017. Luxury goods worldwide market study, Fall–Winter 2017. Bain Report, December 22. http://www.bain.com/publications/articles/luxury-goods-worldwide-market-study-fall-winter-2017.aspx. (accessed July 7, 2021)

- Bain and Company, and Tmall Luxury Division. 2020. China’s unstoppable 2020 luxury market. https://www.bain.com/globalassets/noindex/2020/bain_report_chinas_unstoppable_2020_luxury-market.pdf. (accessed July 7, 2021)

- Benjamin, W. 2003. Central park. In Walter Benjamin selected writings Volume 4 1938-1940, ed. W. Benjamin, H. Eiland, and W. Jennings, 161–99. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Bian, Q., and S. Forsythe. 2012. Purchase intention for luxury brands: A cross cultural comparison. Journal of Business Research 65 (10):1443–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.010.

- Bond, M. H. 1991. Beyond the Chinese face: Insights from psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Calefato, P. 2014. Luxury: Fashion, Lifestyle and excess. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Chen, J., and S. Kim. 2013. A comparison of Chinese consumers’ intentions to purchase luxury fashion brands for self-use and for gifts. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 25 (1):29–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2013.751796.

- Chi, D. 2017. China becomes world’s second largest luxury market. FindChinaInfo, December 12. https://findchina.info/china-becomes-worlds-second-largest-luxury-market. (accessed July 19, 2021)

- Craik, J. 2009. Fashion: The key concepts. Oxford: Berg.

- Dubois, B., and S. Czellar. 2002. Prestige brands or luxury brands? An exploratory inquiry on consumer perceptions. Geneva: University of Geneva. http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:5816. (accessed July 7, 2021)

- Dubois, B., G. Laurent, and S. Czellar. 2001. Consumer rapport to luxury : Analyzing complex and ambivalent attitudes. Vol. 736. Jouy-en-Josas: HEC Paris. http://ideas.repec.org/p/ebg/heccah/0736.html. (accessed July 7, 2021)

- Fionda, A. M., and C. M. Moore. 2009. The anatomy of the luxury fashion brand. Journal of Brand Management 16 (5–6):347–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2008.45.

- Goffman, E. 1972. Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face behavior. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Han, Y. J., J. Nunes, and X. Drèze. 2010. Signaling status with luxury goods: The role of brand prominence. Journal of Marketing 74 (4):15–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.4.015.

- Heine, K., and M. Gutsatz. 2017. Luxury brand building in China: Eight case studies and eight lessons learned. In Advances in Chinese brand management, ed. J. M. T. Balmer and W. Chen, 109–32. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ho, N.-K. M. 2019. Evaluation in English and Chinese marketing communications: An adaptation of the appraisal framework for the genre of luxury fashion promotional texts. PhD thesis, Heriot-Watt University.

- Hofstede, G., and G. J. Hofstede. 2005. Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hofstede, G. H. 2001. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Hofstede, G. H. 2020. Country comparion tool. Hofstede Insights. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/. (accessed July 7, 2021)

- Hung, K., A. Huiling Chen, N. Peng, C. Hackley, R. Amy Tiwsakul, & C. Chou. 2011. Antecedents of luxury brand purchase intention. Journal of Product & Brand Management 20 (6):457–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/10610421111166603.

- Hurlock, E. B. 1929. The psychology of dress. New York: Ronald Press.

- Hyman, H. H. 1942. The psychology of status. New York: Columbia University.

- Jawaid, H., and D. A. Siddiqui. 2020. Does perception of luxury differ in Eastern (Collectivism) verse Western (Individualism) cultural orientation: Evidence from Pakistan. SSRN, 1–41. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3757493. (accessed July 7, 2021)

- Kapferer, J.-N. 1998. Why are we seduced by luxury brands?Journal of Brand Management 6 (1):44–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.1998.43.

- Kapferer, J.-N. 2014a. The artification of luxury: From artisans to artists. Business Horizons 57 (3):371–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2013.12.007.

- Kapferer, J.-N. 2014b. The future of luxury: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Brand Management 21 (9):716–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2014.32.

- Kapferer, J.-N. 2017. Managing luxury brands. In Advances in luxury brand management, ed. J. N. Kapferer, J. Kernstock, T. Brexendorf, and S. Powell, 235–49. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kapferer, J.-N., and V. Bastien. 2009. Luxury marketing plays by a different set of rules. Financial Times, June 15. https://www.ft.com/content/450d99e4-56e9-11de-9a1c-00144feabdc0. (accessed July 7, 2021)

- Kapferer, J.-N., and V. Bastien. 2012. Facets of luxury today. In The luxury strategy: Break the rules of marketing to build luxury brands, 2nd ed., 85–110. London: Kogan Page.

- Kılıç, F., and E. Yolbulan Okan. 2020. Storytelling and narrative tools in award-winning advertisements in Turkey: An interdisciplinary approach. Journal of Marketing Communications 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2020.1780466.

- Kwok, S., and M. Uncles. 2005. Sales promotion effectiveness: The impact of consumer differences at an ethnic-group level. Journal of Product & Brand Management 14 (3):170–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420510601049.

- Langer, D. 2019. Why most luxury brands fail with Chinese millennials. Jing Daily. https://jingdaily.com/luxury-brands-fail-millennials/. (accessed July 7, 2021)

- Lee, C. 1991. Modifying an American consumer behavior model for consumers in confucian culture: The case of Fishbein Behavioral Intention Model. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 3 (1):27–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/J046v03n01_03.

- Lee, W.-N., and N.-H. Um 2014. Celebrity endorsement and international advertising. In The handbook of international advertising research, ed. H. Cheng, 353–74. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons.

- Li, G., G. Li, and Z. Kambele. 2012. Luxury fashion brand consumers in China: Perceived value, fashion lifestyle, and willingness to pay. Journal of Business Research 65 (10):1516–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.019.

- Liao, J., and L. Wang. 2009. Face as a mediator of the relationship between material value and brand consciousness. Psychology & Marketing 26 (11):987–1001. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20309.

- Ma, Y. 2020. Leading luxury brands in China as of 2020, based on the Digital IQ Index. Statista. https ://www. statista .com/st atistics / 979302 /china -leading - luxury -brands -based -on -the- digital - iq- index/. (accessed July 7, 2021)

- Martin, J. R., and P. R. R. White. 2005. The language of evaluation: Appraisal in English. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McKinsey and Company. 2018. The age of digital Darwinism. https ://www.mcki nsey.com/∼/media/McKi nsey/Indus tries/Retail/Our%2520Insights/Luxury%2520in%2520the%2520age%2520of %2520digital%2520Darwi nism/The-age-of-digital-Darwinism.ashx. (accessed July 7, 2021)

- Monkhouse, L., B. R. Barnes, and U. Stephan. 2012. The influence of face and group orientation on the perception of luxury goods. International Marketing Review 29 (6):647–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331211277982.

- Nelissen, R., and M. Meijers. 2011. Social benefits of luxury brands as costly signals of wealth and status. Evolution and Human Behavior 32 (5):343–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.12.002.

- Nystrom, P. 1928. Economics of fashion. New York: Ronald Press.

- Polhemus, T. 2011. Fashion & anti-fashion: exploring adornment and dress from an anthropological perspective . E-book: Lulu.com. (accessed July 19, 2021).

- Prendergast, G., and C. Wong. 2003. Parental influence on the purchase of luxury brands of infant apparel: An exploratory study in Hong Kong. Journal of Consumer Marketing 20 (2):157–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760310464613.

- Prideaux, S. 2019. From Dolce & Gabbana to Versace: Why so many luxury brands fail in China. The National News. https://www.thenationalnews.com/lifestyle/fashion/from-dolce-gabbana-to-versace-why-so-many-luxury-brands-fail-in-china-1.901422. (accessed July 7, 2021)

- Roy, S., V. Jain, and N. Matta. 2018. An integrated model of luxury fashion consumption: Perspective from a developing nation. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 22 (1):49–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-04-2017-0037.

- Sapir, E. 1931. Encyclopedia of the social sciences. New York: Macmillan.

- Shukla, P. 2010. Status consumption in cross-national context: Socio-psychological, brand and situational antecedents. International Marketing Review 27 (1):108–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331011020429.

- Shukla, P. 2012. The influence of value perceptions on luxury purchase intentions in developed and emerging markets. International Marketing Review 29 (6):574–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331211277955.

- Siu, N. Y. M., H. Y. Kwan, and C. Y. Zeng. 2016. The role of brand equity and face saving in Chinese luxury consumption. Journal of Consumer Marketing 33 (4):245–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-08-2014-1116.

- Sridevi, J. 2014. Effectiveness of celebrity advertisement on select FMCG – An empirical study. Procedia Economics and Finance 11:276–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00196-8.

- Sullivan, A. 2015. Fashion. In The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of consumption and consumer studies, ed. D. Cook and J. Ryan, 286–9. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

- Sun, G., S. D’Alessandro, and L. W. Johnson. 2016. Exploring luxury value perceptions in China: Direct and indirect effects. International Journal of Market Research 58 (5):711–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.2501/IJMR-2016-021.

- Tai, H. C., and L. M. Tam. 1996. A comparative study of Chinese consumers in Asia markets: A lifestyle analysis. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 9 (1):25–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/J046v09n01_03.

- Togoh, I. 2019. Luxury brands want to attract Chinese consumers. But why do they keep getting it so wrong? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/isabeltogoh/2019/08/24/luxury-brands-want-to-attract-chineseconsumers-but-why-do-they-keep-getting-it-so-wrong/?sh=53c471076a6e. (accessed December 26, 2020).

- Turunen, L. L. M., and P. Laaksonen. 2011. Diffusing the boundaries between luxury and counterfeits. Journal of Product & Brand Management 20 (6):468–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/10610421111166612.

- Tynan, C., S. McKechnie, and C. Chhuon. 2010. Co-creating value for luxury brands. Journal of Business Research 63 (11):1156–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.10.012.

- Vigneron, F., and L. W. Johnson. 2004. Measuring perceptions of brand luxury. Journal of Brand Management 11 (6):484–506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540194.

- Wallack, L., and K. Montgomery. 1992. Advertising for all by the year 2000: Public health implications for less developed countries. Journal of Public Health Policy 13 (2):204–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3342814.

- Wang, Y., S. Sun, and Y. Song. 2011. Chinese luxury consumers: Motivation, attitude and behavior. Journal of Promotion Management 17 (3):345–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2011.596122.

- Wilson, E. 2003. Adorned in dreams: Fashion and modernity. London: I.B. Tauris & Co.

- Wong, N. Y., and A. C. Ahuvia. 1998. Personal taste and family face: Luxury consumption in Confucian and Western societies. Psychology and Marketing 15 (5):423–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199808)15:5 < 423::AID-MAR2 > 3.0.CO;2-9.

- Yang, J., J. Ma, M. Arnold, and K. Nuttavuthisit. 2018. Global identity, perceptions of luxury value and consumer purchase intention: A cross-cultural examination. Journal of Consumer Marketing 35 (5):533–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-02-2017-2081.

- Zhan, L., and Y. He. 2012. Understanding luxury consumption in China: Consumer perceptions of best-known brands. Journal of Business Research 65 (10):1452–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.011.

- Zhou, L., and M. K. Hui. 2003. Symbolic value of foreign products in the People’s Republic of China. Journal of International Marketing 11 (2):36–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.11.2.36.20163.

Appendix

1 Primary data

Articles chosen as the text data of this study can be accessed on the following websites. To access the articles specifically between 6th January and 8th March 2017, the pages need to be scrolled to the right date as the most recent articles are always shown on top.

English:https://eu.louisvuitton.com/eng-e1/lv-now (Louis Vuitton)https://www.chanel.com/en_WW/fashion/news.html (Chanel)https://www.dior.com/diormag/en_int (Dior)

Chinese:https://www.louisvuitton.cn/zhs-cn/lv-now (Louis Vuitton)https://www.chanel.com/zh_CN/fashion/news.html (Chanel)https://www.dior.cn/diormag/zh_cn (Dior)

(All links were last accessed on 8th March 2019)